- Department of Sociology, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

Introduction: In the riverine areas of Bayelsa State, Nigeria, the intersection of climate change and flooding poses an escalating threat to the livelihoods and well-being of women traders. This qualitative study investigates the experiences and adaptive strategies employed by women traders in response to climate change-induced flooding.

Methods: Employing an exploratory research design with purposive sampling, 46 women traders participated in the study, involving 23 in-depth interviews and three focus group discussions. Thematic analysis was applied to scrutinize the collected data.

Results: The study unravels the impacts of climate change-induced flooding on economic, social, and gender dynamics, revealing economic disparities, gender inequality, livelihood disruptions, inadequate infrastructure, and limited access to information among women traders. Vulnerabilities emanated from disruptions in supply chains, damage to goods, and constrained market access, with agricultural traders being notably affected. Flood events exacerbated gender inequalities, amplifying caregiving responsibilities and limiting decision-making power for women traders. Resilience surfaced through diversified income sources, community solidarity, collective narratives, and local adaptive strategies, including indigenous knowledge and innovations.

Discussion: Policymakers and stakeholders should prioritize resilient infrastructure investments, such as flood-resistant marketplaces and storage facilities, to safeguard women traders’ businesses during flooding events and enhance the overall economic resilience of the community.

1 Introduction

Between November 30 and December 13, 2023, global leaders convened in Dubai for the United Nations Climate Change Conference, COP28, to address the pressing issue of reducing global warming and mitigating its consequences, including the growing threat of flooding (United Nations, 2023). This pivotal gathering underscored the urgent need for action, as the widespread impacts of climate change-induced environmental shifts have become increasingly apparent, reshaping ecosystems and impacting communities worldwide (Rabbani et al., 2022; Filho et al., 2023; Jansson and Wu, 2023). The warming atmosphere, now containing higher levels of moisture, accelerates evaporation from oceans and water bodies, consequently increasing atmospheric water vapor content (Ariyaningsih Sukhwani and Shaw, 2023; Otto et al., 2023). It also exacerbates precipitation events, leading to intensified rainfall that overwhelms drainage systems and natural watercourses, thereby increasing the risk of widespread flooding (Vinke et al., 2022; Damte et al., 2023; Ntali et al., 2023).

As of 2020, the global average temperature had risen by 1.1°C compared to the beginning of the last century, signaling a shift toward record-breaking floods becoming the norm (UN Environment Programme, 2024). The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) highlights the escalating coastal flooding over the past two decades due to rising sea levels, placing an additional 14 million people worldwide in coastal areas with a 1-in-20 annual probability of flooding. Furthermore, it reports that the impact of climate change on coastal flooding is projected to increase five-fold over the current century (United Nations Development Programme, 2024).

Statistics reveal that a substantial 23% of the global population, equivalent to 1.81 billion people, faces direct exposure to floods, posing significant risks to lives and livelihoods (Rentschler et al., 2022). Floods are identified as the deadliest form of natural disasters, contributing to 43.5% of all fatalities resulting from such events (Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters, 2020). Notably, 89% of those affected by floods reside in low-and middle-income countries, with 170 million individuals facing flood exposure living in extreme poverty (earning less than $1.90 a day). In sub-Saharan Africa, where 74.7 million people both face flood exposure and live in extreme poverty out of 176 million flood-exposed individuals, this intersection is most pronounced (Rentschler et al., 2022). In the region, floods have disrupted trading and transportation routes, damaged infrastructure and destroyed crops, leading to supply chain disruptions and reduced productivity, with gender dynamics playing a crucial role in increasing vulnerability (Awazi et al., 2023; Michael, 2024). Women are more vulnerable to the flooding due to social and economic factors, including limited access to resources, restricted mobility, and unequal decision-making power (Ibrahim and Mensah, 2022; Perelli et al., 2024). Studies such as those in Burkina Faso (Vinke et al., 2022), Cameroon (Ntali et al., 2023) and Zimbabwe (Chidakwa et al., 2020) have highlighted how gender inequalities intersect with flood impacts, leading to heightened vulnerability among women. To cope with climate change-induced flooding in sub-Saharan Africa, adaptive measures that have been implemented include early warning systems, resilient infrastructure development, and ecosystem-based approaches (Suhr and Steinert, 2022; Xiao et al., 2022; Fonjong and Zama, 2023).

Nigeria emerges as one of the most flood-prone nations in West Africa, with severe consequences observed in 2022, leading to over 600 fatalities and impacting approximately 3.2 million individuals across 34 out of 36 states. The destruction of over 569,251 hectares of farmland in Nigeria (Ongoma and Dike, 2023), underscores the profound consequences of flooding. The Nigerian Meteorological Agency (NiMet) identifies Bayelsa as a high-risk state for floods, with instances documented (Ejike, 2022). The aftermath of these floods in Bayelsa has been impactful, submerging homes and farmlands and displacing hundreds of thousands of residents (Petracca et al., 2022; Michael, 2024).

Amidst those grappling with these challenges of flooding are vulnerable populations, with women, as agents of change and economic contributors, finding themselves on the front lines (Andersen et al., 2023; Ngcamu, 2023). The riverine areas of Bayelsa State, Nigeria, offer a poignant illustration of a region contending with the adverse effects of climate change, particularly recurrent flooding. Bayelsa State, characterized by an extensive network of rivers and estuaries, has witnessed a notable increase in the frequency and intensity of flooding events, attributed to the overarching impacts of climate change (Tonye-Scent and Uzobo, 2020; Ejike, 2022). Against this backdrop, women traders, integral actors in the economic fabric of these communities, face unique challenges extending beyond the immediate impacts of flooding (Tan et al., 2022; Anugwa et al., 2023). This study aims to provide a nuanced understanding of the multifaceted consequences experienced by women traders and the adaptive strategies they employ to mitigate the adverse effects on their livelihoods.

The significance of this research lies in its potential to bridge existing knowledge gaps and contribute contextually relevant insights to the broader discourse on climate change adaptation and gender dynamics, as this is the first study conducted in Nigeria with attention given to this intersectionality among women traders (Michael and Ekpenyong, 2018; Anik et al., 2023; Fonjong and Zama, 2023). By amplifying the voices of women traders, this study seeks to unravel the interplay between environmental shifts, economic resilience, and sociocultural frameworks. The exploration does not only deepen our understanding of the challenges faced by women in the riverine areas of Bayelsa State but also informs targeted interventions and policies addressing the specific needs of this vulnerable demographic (Michael and Odeyemi, 2017; Akinbami, 2021).

Recognizing the necessity of an inclusive and participatory approach, this study acknowledges the agency and resilience of women traders who, despite environmental adversity, navigate the complex web of challenges with determination and resourcefulness (Awazi et al., 2023; Khan et al., 2023). Through their narratives, this research aims to contribute meaningful insights empowering communities, policymakers, and stakeholders to develop adaptive strategies rooted in the lived experiences of those directly impacted by climate change-induced flooding (Ibrahim and Mensah, 2022; Praag et al., 2022). Consequently, this study sheds light on the challenging experiences and adaptive tactics employed by women traders in the riverine areas of Nigeria, while also presenting actionable implications for policy formulation and implementation.

2 Background literature review

2.1 Experiences

Experiences refer to the personal encounters, events, and situations that individuals go through and the impact these have on their lives (Helkkula et al., 2012). In the context of the study, experiences specifically relate to the challenges, disruptions, and observations that women traders face as a result of climate change-induced flooding. Experiences are fundamental to capturing the multifaceted nature of the challenges and impacts faced by these women (Ntali et al., 2023; Ogunleye et al., 2023). Experiences suggest a holistic approach to understanding the lived realities of women traders. It encompasses a wide spectrum of encounters, including the immediate impacts of flooding events, the ongoing challenges in the aftermath, and the nuanced ways in which climate change shapes their trading activities (Pautz, 2011). By focusing on experiences, the study has the potential to uncover diverse perspectives and narratives. This allows for a nuanced exploration of how different women traders, each with their unique circumstances, navigate and interpret the challenges posed by climate change-induced flooding (Petracca et al., 2022; Ongoma and Dike, 2023).

Experiences inherently imply a temporal dimension, acknowledging that the effects of climate change and flooding unfold over time. This provides an opportunity to explore both immediate reactions and longer-term adaptations, contributing to a comprehensive understanding of the dynamic nature of the challenges (Praag et al., 2022). While the term captures the subjective nature of the challenges faced by women traders, it’s essential for the study to recognize the diversity within this group. Different women may interpret and respond to the impacts of flooding differently based on their individual circumstances, roles, and socio-economic factors (Rabbani et al., 2022; Tan et al., 2022). The concept of experiences aligns well with the study’s focus on intersectionality. It allows for an exploration of how gender, economic status, geographic location, and other factors intersect to shape the nuanced experiences of women traders in the face of climate change-induced flooding (Rentschler et al., 2022). Experiences indicate a sensitivity to the cultural and contextual nuances of the study area. It recognizes that the impact of climate change and flooding is not uniform and allows for an exploration of how local context shapes the experiences of women traders (Prince et al., 2023).

2.2 Adaptive strategies

Adaptive strategies, also known as coping strategies, are the mechanisms and actions individuals employ to deal with and navigate through challenging or stressful situations (Abel, 2002; Ngcamu, 2023). In the study, adaptive strategies pertain to the various approaches and responses that women traders adopt to mitigate the adverse effects of climate change-induced flooding on their trading activities and livelihoods (Anugwa et al., 2023). The term adaptive strategies inherently suggest a focus on coping measures and resilience. This aligns well with the study’s objective of understanding how women traders respond to the challenges posed by climate change-induced flooding, providing insights into their capacity to navigate adversity (Chidakwa et al., 2020). By emphasizing adaptive strategies, the study explores the behavioral responses of women traders. This includes changes in trading practices, diversification of livelihoods, and the adoption of new approaches to minimize the impact of flooding on their economic activities (Ejike, 2022). The adaptive strategies underscore the agency of women traders in actively responding to challenges (Ray et al., 1982). This approach acknowledges that women are not passive victims but are engaged in decision-making and taking deliberate actions to protect their livelihoods. While the term is powerful, there’s a need to delve into the specific coping strategies employed and understand their effectiveness within the local context. This requires exploring whether these strategies are sustainable, culturally appropriate, and contribute to long-term resilience (Lelenguyah et al., 2022; Filho et al., 2023).

2.3 Women traders

Women traders are individuals who engage in the buying and selling of goods and services as a means of economic livelihood, and who identify as female (Muzvidziwa, 2001). The term women traders explicitly delineate the demographic group under study, acknowledging the unique challenges, roles, and experiences of women engaged in trading activities. This specificity enhances the study’s ability to provide targeted insights into the impact of climate change-induced flooding on this particular group (Chidakwa et al., 2020). By focusing on women traders, the study adopts a gender lens, recognizing the intersectionality of gender with climate change impacts. This approach allows for an exploration of how societal gender norms, roles, and expectations influence women’s experiences and coping strategies. The term emphasizes the economic aspect of women’s roles as traders, highlighting their contributions to household incomes and economic activities (Hilton, 1984; Damte et al., 2023). This economic dimension is crucial for understanding the broader implications of climate change-induced challenges on financial stability and livelihoods (Ibrahim and Mensah, 2022). Women traders implicitly recognizes the intersectionality of identity factors. The study can explore how factors such as age, socioeconomic status, and cultural context intersect with gender, influencing the experiences and coping strategies of women traders. The term allows for an exploration of both vulnerability and resilience (Fonjong and Zama, 2023). It acknowledges that while women traders may face heightened vulnerabilities due to gendered impacts, they also demonstrate resilience through their economic activities and adaptive responses. Women traders are often embedded in their communities, contributing to the local economy and social fabric (Akinbami, 2021). The study explores how the experiences of women traders are intertwined with community dynamics, relationships, and support networks.

2.4 Climate change-induced flooding

Climate change-induced flooding refers to the occurrence of flooding events that are influenced or exacerbated by changes in climate patterns, including increases in temperature, shifts in precipitation, rising sea levels, and extreme weather events (Cheng et al., 2017). The term climate change-induced flooding places the study within an environmental context, highlighting the link between flooding events and broader climate change patterns (Berezi et al., 2019). This connection is crucial for understanding the root causes and long-term implications of the flooding experienced by women traders (Ariyaningsih Sukhwani and Shaw, 2023). By specifying that the flooding is induced by climate change, the study establishes a causal link, acknowledging the role of anthropogenic activities in shaping the frequency and intensity of flooding events. This attribution is significant for policy discussions and mitigation efforts (Ejike, 2022). The term inherently suggests a temporal dimension, indicating that the flooding events are not isolated occurrences but are part of a larger pattern influenced by long-term climate trends. This temporal perspective allows for a more comprehensive analysis of the evolving challenges (Otto et al., 2023). Climate change-induced flooding implies that the flooding events are not only driven by immediate weather patterns but are part of a broader ecological shift (Shu et al., 2023). This recognition allows for the exploration of multifaceted impacts, including changes in precipitation, sea level rise, and extreme weather events (UN Environment Programme, 2024). The term highlights the vulnerability of riverine areas to climate change-induced flooding. Riverine environments are particularly sensitive to changes in precipitation and sea level rise, and understanding this vulnerability is crucial for developing context-specific adaptation strategies (Ongoma and Dike, 2023). The concept recognizes the intersectionality between climate change impacts and gender. It implies that climate change-induced flooding may not affect all demographic groups equally, and the study can explore how women traders navigate and respond to these specific environmental challenges (Petracca et al., 2022; Suhr and Steinert, 2022).

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Study setting

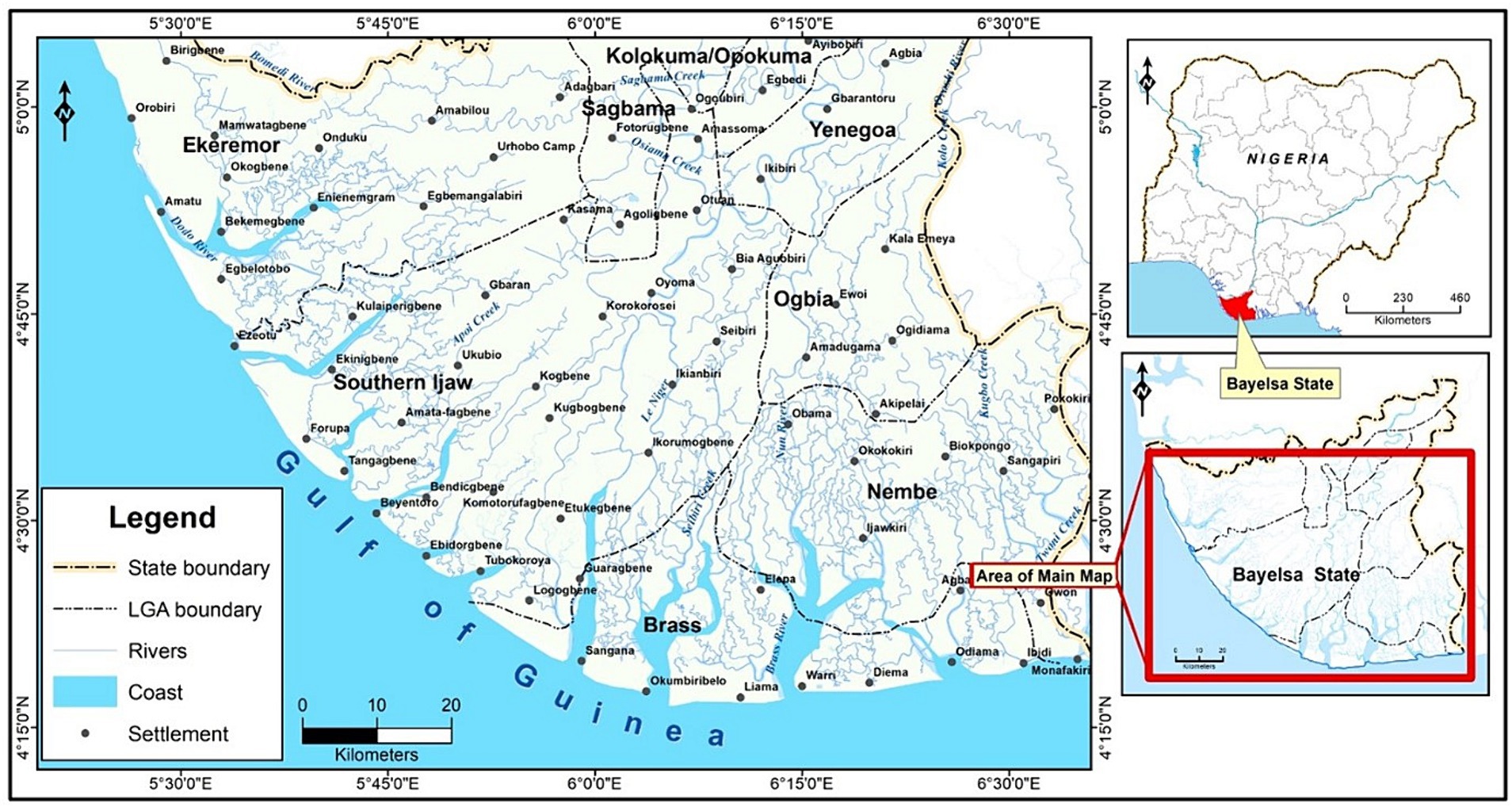

The research was conducted in the riverine regions of Bayelsa State, Nigeria, situated in the Niger Delta area characterized by a network of rivers, creeks, and estuaries. The region faces substantial environmental challenges, particularly recurrent flooding attributed to the impacts of climate change. The State is home to an approximate population of 2,394,725 million people (National Bureau of Statistics, 2020). It spans a total land area of around 21,110 km2/10,773 km2 (Elum and Snijder, 2023). The women in Bayelsa State predominantly engage in trading, fishing, and agriculture as their primary economic activities. Additionally, communities in the state are known for facing fluctuations in weather patterns, contributing to an increased risk of flooding. This study specifically focused on Southern Ijaw and Yenagoa, the two major local government areas with several riverine communities well-known for their vulnerability to flooding. The effects of flooding in these locations extend to diverse groups of people, including both migrant and non-migrant dwellers, as well as residents in urban and rural areas. Figure 1 displays the map of Bayelsa showing the riverine areas in the local government areas selected for the study.

Figure 1. Map of Bayelsa state highlighting the riverine areas within the study region (Michael, 2024).

3.2 Study design

This study utilized a qualitative research design to delve deeply into the experiences and adaptive strategies of women traders grappling with climate change-induced flooding in the riverine areas of Bayelsa State, Nigeria. Qualitative method was chosen for its aptness in capturing the nuanced and context-specific aspects of the challenges encountered by this vulnerable demographic. The reporting of this manuscript adheres to the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) (O’Brien et al., 2014).

3.3 Sampling and sample size

Purposive sampling was employed to carefully select 46 women traders from various riverine communities in Bayelsa State whose business were directly affected by the 2022 flooding that submerged the region. The study was conducted 6 months after the flooding. Selection criteria encompassed diversity in age, trading activities, and exposure to flooding. The determination of the sample size took into account data saturation, ensuring the inclusion of a satisfactory number of participants to capture a broad spectrum of experiences and perspectives. Saturation for in-depth interviews (IDI) was reached after conducting interviews with 23 participants, while saturation for focus group discussions (FGD) was achieved after completing three group sessions.

3.4 Data collection

Semi-structured, in-depth interviews, and focus group discussions were undertaken to collect comprehensive qualitative data. The interviews delved into personal narratives, challenges encountered, and adaptive mechanisms, while the group discussions explored collective experiences, group norms, and community members’ perceptions. The interview guide included questions such as: “Can you describe any specific incidents or events related to flooding that have impacted your trading activities? What changes have you observed in weather patterns or flooding events over the years? What kinds of challenges do you face during and after flooding events in relation to your trading business? What strategies have you adopted to cope with the challenges posed by flooding?”

With participants’ consent, the interviews were audio-recorded, and detailed field notes were taken during and after each session to capture non-verbal cues and contextual details. Individual interviews ranged from 45 to 60 min, while the duration of focus group discussion sessions varied from 60 to 76 min. Both interviews and discussions were conducted in English and Pidgin English. The choice of language was significant, as Pidgin English serves as the primary means of communication among traders in the study area, especially among those with lower education levels, the elderly, and individuals with a low socioeconomic status. The interview guides were also designed in both English and Pidgin English to ensure effective communication. Interviews were conducted in locations convenient and comfortable for participants, such as community centers, marketplaces, and participants’ homes. These venues were chosen to facilitate open and honest conversations. Given the climate-sensitive nature of the research, data collection was timed to coincide with relevant seasons, considering weather patterns, flooding events, and the trading calendar to enhance the accuracy of participants’ recollections and experiences.

3.5 Analysis

The interviews and discussions conducted in Pidgin English were transcribed and subsequently translated into English. The transcripts underwent multiple readings before being imported into ATLAS.ti version 23 to facilitate the analysis process. Thematic analysis was employed for the transcripts from both interviews and discussions. Emerging themes pertaining to experiences, challenges, and adaptive strategies were identified, coded, and systematically organized into themes. The analysis encompassed coding, categorization, and the identification of patterns within the data, enabling the extraction of meaningful insights from the collected field data (Castleberry and Nolen, 2018).

3.6 Ethical considerations

Before participating, all individuals were provided with comprehensive information about the study’s objectives, procedures, and their rights. Informed consent was obtained from each participant, ensuring their voluntary engagement. Confidentiality and anonymity were strictly upheld throughout the study, with any identifying information meticulously removed from transcripts and research outputs. The research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, adhered to ethical guidelines and obtained approval from the Ethics and Research Review Board of Federal University Oye-Ekiti, Nigeria (FUOYE/SOC/ETHICS/005).

3.7 Reflexivity

Effectively managing researcher reflexivity is imperative for upholding the integrity of any research endeavor, particularly when delving into sensitive topics such as the experiences and adaptive strategies of women traders confronting climate change-induced flooding (Wilson et al., 2022). This consideration became paramount as the primary researcher, TOM, possesses expertise in social science, climate change, and gender, and also completed university studies in the study area, affording familiarity with the cultural practices of the people. The researcher worked alongside two trained research assistants. However, given the researcher’s knowledge of the Niger Delta region, there was a recognition that this expertise could potentially influence the interpretation of findings. To counteract this influence, conscious efforts were undertaken to set aside any pre-existing knowledge of riverine climate change and women trading. This approach allowed the researcher to present the participants’ views authentically without imposing personal biases, aligning with the principles of qualitative research that seek to observe the genuine attitudes, motivations, and beliefs of the participants (England, 1994).

Throughout the study process, the researcher’s role was solely in relation to academic research. This deliberate framing created a comfortable environment for participants to openly discuss their experiences. The identification of women participants affected by flooding was facilitated by women traders’ associations; however, these associations were not permitted to be present during the interviews. This measure was implemented to ensure that participants could freely express themselves without external influence. Furthermore, the research benefitted from the guidance and support of ES and SE, established researchers at the Niger Delta University in Bayelsa State. Their involvement extended across the study’s various phases, including design, data collection, and analysis. This collaborative approach enhances the credibility of the study, and contributes to a bias-free analysis and findings. By maintaining reflexivity, a commitment to open-mindedness was upheld, allowing the data to guide the findings. The continuous reflection on how preconceptions might influence data interpretation underscored the researcher’s dedication to an unbiased and participant-centered analysis. Reflexivity also served as a reminder to approach each interaction with humility, acknowledging that academic background does not replace the lived experiences of the participants (Yip, 2023).

3.8 Data trustworthiness

To enhance the credibility and trustworthiness of the findings, various data sources were incorporated, encompassing interviews and discussions with women traders, including both association women leaders and members. Preliminary findings were shared with the participants for member checking, affording them the opportunity to validate or contribute additional insights to the interpretation of their experiences (Rolfe, 2006).

4 Findings

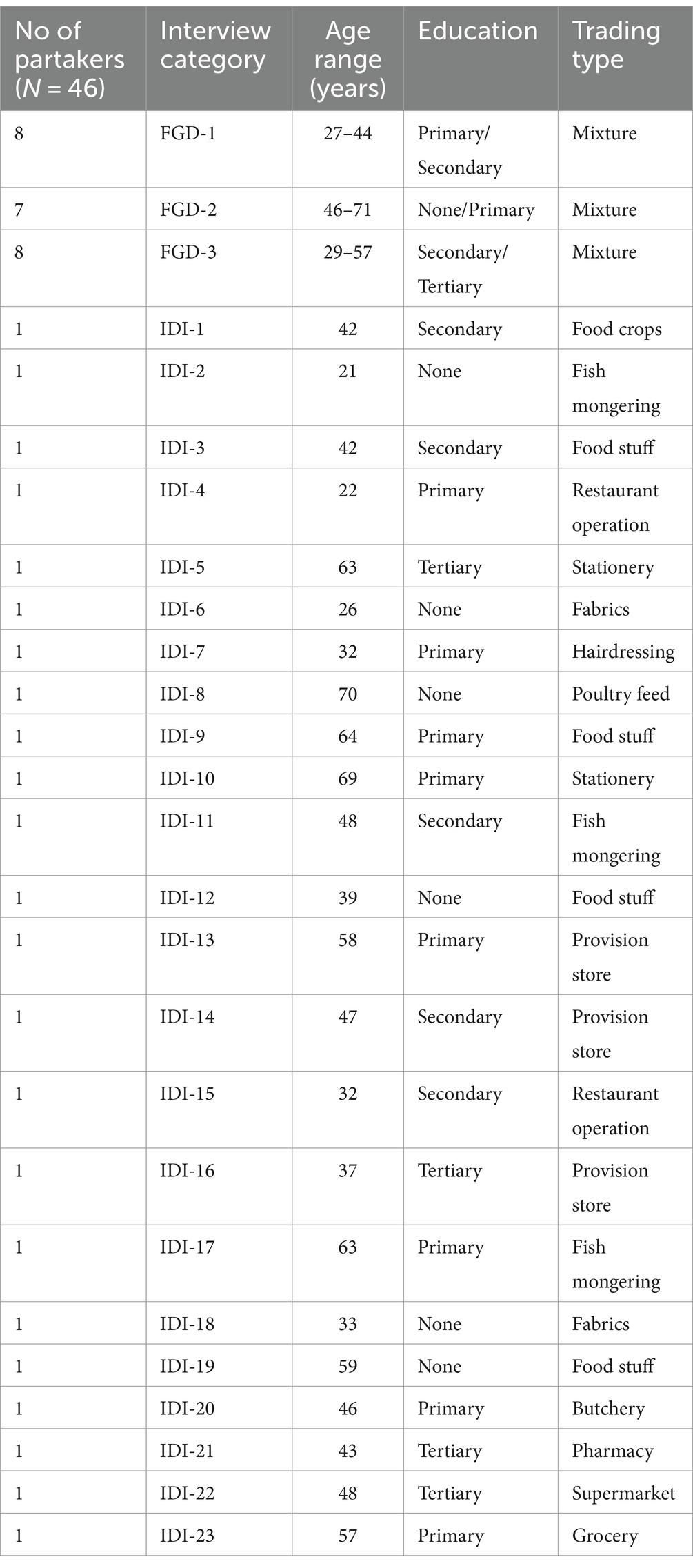

4.1 Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents

Table 1 delineates the socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants, comprising 46 individuals categorized into Focus Group Discussions (FGD) and In-Depth Interviews (IDI). The FGDs (FGD-1, FGD-2, FGD-3) involve a total of 23 participants engaging in varied trading activities, with education levels ranging from primary to tertiary, and spanning an age range of 27 to 71 years. The IDIs (IDI-1 to IDI-23) further enrich the diversity, featuring participants aged 21 to 70 with a spectrum of educational backgrounds. The participants are involved in specific trading activities, such as food crops, fish mongering, foodstuff, restaurant operation, stationery and fabric sales, hairdressing, poultry feed, provision store management, butchery, pharmacy, and supermarket operations. This extensive range of trading activities underscores the economic diversity within the sample. The varying age groups and educational backgrounds mirror the broader demographic landscape of the community under study, providing a nuanced understanding of the socio-economic dynamics among the respondents.

4.2 Challenging experiences of the women traders

4.2.1 Economic disparities

Women traders reported significant economic losses due to climate change-induced flooding, with disruptions in supply chains, damage to goods, and reduced market accessibility. The impacts were more pronounced for women engaged in agriculture-related trading activities. The interview responses highlighted the disproportionate impact of flooding on women engaged in agriculture, particularly those involved in selling fish, food products, and farm-produced items. The flood-induced challenges were particularly profound for these women, as the inundation hindered their ability to purchase new goods, affecting their livelihoods. The economic repercussions were not uniform, as articulated by the participants, with those who had recently acquired a significant quantity of goods being the most adversely affected. Conversely, individuals who had not recently restocked experienced comparatively less damage. The financial strain resulting from damaged goods led some business-people to resort to borrowing money or taking out loans to restock post-flood. This economic fallout underscored a growing disparity among business women, contributing to a less equal economic landscape in the aftermath of the flood.

“Flooding had a bigger effect on those of us women who work in agriculture than on others … I'm talking about people who sell fish, food products, and farm produced food … Because of the flood, we couldn't buy new goods.” [FGD-2]

“The floods made our economies less equal. Women who just got back from the market with a lot of goods were the ones who suffer the most … Less damage was done to those of us who didn't stock our shops with new items … People who kept goods that were damaged by the flood had to borrow money or get loans to buy new goods after the flood… There were big gaps between richer and poorer business women after the flood.” [IDI-9]

The participants responses delve into the broader regional impact of the flood in Bayelsa State, emphasizing its profound consequences on the economy and food supply. The interviewees noted the widespread hunger during the flood, highlighting the critical need for essential items, especially food. The logistical challenges posed by the flood, disrupting transportation routes like the Mbiama and Ahoada roads connecting Rivers State to Bayelsa, hindered the inflow of supplies. The impact extended beyond Bayelsa State, affecting neighboring states, and the destruction of crucial infrastructure like bridges connecting Delta state to Bayelsa added another layer of complexity to the regional crisis. These responses shed light on the multifaceted challenges faced by communities, intertwining economic and logistical struggles during and after the flood in the Bayelsa region.

“In Bayelsa State, nearly everyone was hungry during the flood, so people needed things, especially food … But there was no way to get food into the state. The flood affected all the states that are close to Bayelsa … There was flooding on the roads Mbiama and Ahoada, which connect Rivers State to Baylesa … Erosion, water and wind broke the bridge that connects Delta state to Bayelsa.” [IDI-22]

4.2.2 Social, cultural, and gender inequality

Flood events exacerbated existing gender inequalities, with women traders facing challenges related to increased caregiving responsibilities, limited decision-making power, and restricted mobility. Traditional gender roles were reinforced during recovery and reconstruction phases. The interview responses revealed the profound impact of flooding on the dynamics of gender relationships within the community. Women sellers expressed the added difficulty of navigating unfair treatment and increased dependence on their partners as a consequence of the flood. The financial strength that once empowered these women was compromised when their sources of income were lost to the flood, leaving them vulnerable to exploitation by their husbands and partners. This underscores how economic disruptions exacerbate existing gender inequalities, as women grappled with both the loss of financial autonomy and the exploitation of their vulnerability by those in positions of power.

“The flooding made it harder for us women sellers to deal with unfair treatment of women and being more dependent on our partners… You know being strong financially is a good thing … When we lose our source of income. We turn to our husbands and partners, who now take advantage of how weak we are.” [IDI-1]

“The flooding made us more responsible for taking care of the house … Women are usually the ones who take care of children… When the flood took away our income, it became hard to take care of our children.” [FGD-1]

As reported by the participants, the flood heightened the responsibilities placed on women in the aftermath. With men commonly perceived as less proactive in assuming household and childcare duties in this region, the loss of income due to the flood intensified the challenges faced by women in caring for their children. The interviews shed light on the cultural context, where polygamous marriages are prevalent as a strategy for men to evade financial responsibilities. The flood accentuated these existing patriarchal structures, with husbands taking advantage of their wives’ increased dependence during the crisis. The lack of savings to recover from the flood’s effects further magnified the vulnerabilities of families, emphasizing the critical role women play as economic pillars in this community.

“The flood made us more open to the patriarchy that was already present in our communities … In this area, men marry more than one woman because they don't want to take care of their wives and children … Men got married many times because having more than one wife lets them eat from any of them, even if they haven't given their wives any money for food… Husbands now take advantage of their wives because the wives need their attention …” [IDI-16]

“We suffered a lot during and after the flood because we had no savings to recover from its effects. This is because most families in this area depend on women to make money.” [IDI-2]

4.2.3 Livelihood disruptions

According to the participants, women traders experienced immediate setbacks during flooding events, including loss of inventory, temporary closures of trading spaces, and challenges in securing alternative income sources. The cumulative effect of recurrent flooding led to long-term economic instability, hindering the capacity of women traders to reinvest in their businesses and limiting opportunities for business expansion. The interview responses provided a poignant insight into the severe economic setbacks faced by business owners due to the floods. The loss of inventory emerged as a critical issue for traders, as it not only disrupted their ability to recover money from customers who made purchases on credit but also undermined their credibility with buyers who disputed amounts owed in the absence of proper records. This loss of financial control and the inability to recoup funds significantly impacted the profitability of the business, resulting in substantial monetary losses for the interviewees.

“I lost my inventory during the floods. For traders, that means a lot of things… Without inventory, we can't get all the money back from people who bought things and promise to pay us later … Some buyers wouldn't tell me how much they owed me because I couldn't show them a record … This really injured my business and income … I lose a lot of money.” [FGD-2]

The participants’ responses underscored the prolonged and multifaceted impact of the flood on businesses. The forced closure of businesses for four months, coupled with structural damage to the shops, including dampness affecting paint, walls, and furniture, illustrated the extended hiatus in income generation. The inability to fully reopen due to the lingering effects of the flood compounded the financial strain, highlighting the enduring consequences on the livelihood of the business owners.

“Because of the flood, I had to close my business for four months. I couldn't fully reopen after the flood because the shop was still damp … The paint, the walls of the building, and the furniture were all damaged … My source of income was cut off.” [IDI-12]

The interviewees highlighted the broader economic challenges imposed by the flood, emphasizing the scarcity of viable alternatives for income generation during the crisis. With nearly every type of business shut down by the flood, the participants faced a significant barrier in diversifying or initiating a new source of income.

“During the floods, it was hard for me to find other ways to make money … The flood shut down almost every type of business I could think of, so I couldn't start a new one.” [IDI-20]

4.2.4 Inadequate infrastructure

Participants highlighted the inadequacy of existing infrastructure, particularly the lack of flood-resistant marketplaces and storage facilities, hindering their ability to protect goods during flooding events. The interview responses highlighted the vulnerability of businesses and goods to flooding due to inadequate infrastructure and planning. The participants highlighted the lack of proper storage facilities for food, leaving goods susceptible to destruction during floods. The inadequacies of the market infrastructure, including a lack of effective measures to prevent floodwater from entering shops, compounded the challenges faced by businesses. This pointed to a systemic issue where the existing market setup was ill-equipped to withstand or mitigate the impact of floods, leaving goods and livelihoods exposed to avoidable risks.

“Because we didn't have places to store food, the floods destroyed most of our goods … Our markets weren't set up well enough to keep floods from coming into our shops.” [FGD-1]

The responses implicated government infrastructure in the vulnerability to flooding. Poor planning and neglect of flood considerations during the construction of roads led to blocked gutters and water pathways, resulting in recurrent flooding in the area. The failure to account for potential flood risks in urban planning contributed to the heightened vulnerability of businesses and homes, perpetuating a cycle of damage caused by flooding and impeding the overall resilience of the community.

“Because the government didn't think about flooding when they built our roads, the gutters and water pathways are often blocked … Businesses and homes in our area are often flooded by mere rain water.” [IDI-23]

The participants shed light on the structural shortcomings of shop buildings, emphasizing the lack of effective flood prevention measures. Beyond floods, the inherent design flaws, such as cold walls and floors, further exacerbated the susceptibility to damage caused by flooding, emphasizing the need for improved infrastructure and construction practices that consider the region’s environmental challenges.

“Our shop buildings are not built in a way that keeps floodwater out. Outside of floods, the walls and floor of our building are cold … Any waterfall causes flood and damages our goods and food.” [FGD-3]

4.2.5 Limited access to information

Women traders expressed challenges in accessing timely and accurate weather information, inhibiting their ability to make informed decisions about when and where to trade. The interview responses pointed at the unpredictability and challenges associated with obtaining timely information about impending floods. The participants highlighted the element of surprise, noting that the flood often arrived unexpectedly, leaving the community unprepared due to the lack of advance notice. This lack of timely information contributed to the vulnerability of women traders and businesses, limiting their ability to take preventive measures or evacuate in a timely manner.

“The flood came as a surprise to us, and we're not prepared because we didn't find out about it until it's too late.” [IDI-5]

The responses probed into the difficulty of navigating uncertainty. While the participants acknowledged occasional warnings about potential floods, the unpredictable nature of these events created a dilemma. Balancing the need to be prepared with the uncertainty of when the flood might occur posed a significant challenge for business owners. The unpredictability, with floods sometimes emerging rapidly, exacerbated the difficulty of planning and safeguarding businesses against the impacts of flooding.

“I didn’t know in time this year that there would be a flood, but what will I do? People sometimes tell us that floods will start in two or three months this year, but there have been none yet … Sometimes, the flood will come on quickly … We won't be able to run our businesses if we continue to worry about floods.” [IDI-18]

The participants shed light on the information disparity exacerbated by limited access to technology. The lack of a television, a common source of broadcasted warnings, means that individuals without this technology rely on information shared by their peers. This reliance on word-of-mouth increased the risk of delayed or inaccurate information dissemination, further complicating efforts to prepare for and respond to impending floods. These responses collectively emphasized the critical need for improved communication channels and timely dissemination of information to enhance community preparedness in the face of unpredictable flood events.

“I was told that the last flood had been broadcast on TV before it happened, but I don't have a TV, so how can I hear unless my fellow sellers tell me?” [FGD-1]

4.3 Adaptive strategies of the women traders

4.3.1 Diversification of income sources

Women traders exhibited resilience by diversifying their income sources, engaging in multiple types of trading activities, and exploring alternative livelihood options beyond the traditional sectors affected by flooding. The interview responses revealed various strategies adopted by study participants to mitigate the financial impact of flooding. A participant demonstrated resilience by diversifying income streams. Engaging in buying and selling unripe plantains, selling food, roasted plantains, and plastic household items provided multiple avenues for income generation. This diversified approach allows for flexibility during floods, ensuring the ability to continue trading even if one aspect of the business was affected. It showcased a proactive effort to adapt to the challenges posed by flooding by diversifying products and services.

“What I do now is make sure I have another way to make money in case of a flood… While I buy and sell unripe plantains. On top of that, I sell food, roasted plantains, and plastic home goods … If there is a flood and I can't buy or sell food, I sell plastic household items.” [IDI-9]

The participants adopted a financial planning approach to safeguard against flooding-related disruptions. Utilizing a contributory plan to invest money, particularly during flood seasons, served as a risk management strategy for the women traders. While acknowledging the potentially lower returns compared to direct investment in the trade business, this approach provided a measure of financial security during periods of flooding for the women. The strategy demonstrated a forward-thinking approach to financial management, considering the unpredictable nature of flood events.

“Some of my money is now in a contributory plan, which is how I made money during the floods… So when it starts to flood, I don't leave my money at home; instead, I put it into the contributory plan to make interest … I might not make as much as if I put the money straight into my trade business, though.” [IDI-21]

Conversely, the participants shared a cautionary tale about the challenges associated with financial investments. Despite the intent to safeguard against flooding impacts by placing money in a cooperative, a participant faced a significant loss of N850,000 with a deceptive cooperative. This unfortunate experience underscores the potential risks associated with financial investments and highlights the need for careful consideration and due diligence when choosing financial establishments.

“I put my money in financial establishments because of the flood. But I felt bad about the last investment I made with xxx Cooperative [name withhold for ethical reasons] … I lost N850,000 (approximately $1,012) on this scheme, and this group still hasn't given me my money back.” [IDI-6]

Some participants adapted their business strategy during floods based on the challenges of accessing farm products. The emphasis on selling more fish, which is more accessible during flooding, showcases a pragmatic approach to meet market demands and sustain income during adverse conditions. This adaptive strategy underscores the importance of aligning business activities with the realities of the local environment, including seasonal challenges like flooding.

“My passion is farming, and I sell both farm goods and fish. During flooding, I sell more fish because farm products are usually hard to access.” [FGD-2]

4.3.2 Community solidarity and collective narratives

Collaborative efforts within women’s groups and communities were evident, with mutual support networks forming to share resources, provide emotional assistance, and collectively respond to the challenges posed by flooding. Sharing experiences and narratives within the community also emerged as an adaptive mechanism, fostering a sense of solidarity and providing a platform for emotional support. The interview responses highlighted the significant role of communal support and shared narratives in coping with the aftermath of flooding. The participants recognized the therapeutic value of coming together with fellow flood survivors to share experiences and stories. This communal dialog served as a crucial support system, allowing individuals to express their emotions, provide comfort, and gain insights from others who have faced similar challenges. The act of sharing flood experiences became a collective effort to navigate the emotional toll and rebuild lives after the crisis.

“Getting together with other people who have been through flooding to talk about and share our stories helped us get back on our feet after it happened … We talk about our flood experiences to comfort and support each other.” [IDI-10]

The participants shed light on the intangible yet invaluable benefits of discussing floods within the community. While acknowledging that these conversations did not directly generate income, they provided essential mental support and foster a sense of belonging. In the face of adversity, the shared experiences created a supportive environment where individuals feel understood and connected, mitigating the isolation that often accompanies such challenges. This communal aspect become a form of emotional sustenance that contributed to the participants’ resilience.

“Talking about the floods doesn't earn us money, but it does give us mental support and a sense of belonging… It makes us feel like we're not the only ones stuck in the water.” [IDI-2]

The participants emphasized the broader impact of collective storytelling in instilling hope and preventing extreme measures. By learning about the experiences of others who had faced similar or more severe consequences of the flood, women traders found solace and a renewed sense of purpose. The shared stories acted as a lifeline, preventing desperate actions by fostering a sense of solidarity and shared endurance. This underscores the profound impact of community support and the transformative power of collective narratives in dealing with the psychological and emotional toll of flooding difficulties.

“We found out that some people were being hit harder by the flood than we were when we talk about it. This gives us hope… Collective story has helped us deal with flooding difficulties… Some of us would have killed ourselves, but we haven't because of how we discuss our bad situations as a group.” [IDI-14]

4.3.3 Local adaptive strategies and innovations

Local communities demonstrated adaptive strategies, such as elevated market stalls and the use of indigenous knowledge and technology, contributing to community resilience in the face of climate change-induced flooding. The interview responses reveal innovative and adaptive strategies employed by study participants to navigate the challenges posed by flooding. The participants described a creative solution to river crossing during floods, utilizing a long rope and skilled swimmers to secure it to a large tree on the opposite side. This makeshift ferry system enabled the community to access essential resources, particularly food, in the face of flooded terrain, showcasing the resilience and resourcefulness of the group.

“When we had the last flood, we came up with a new way to cross the river by using a very long robe … Some people in the group were good swimmers, they had to cross the river to the other side to tie the rope on a big tree while the rest of us walk through the water, holding the robe to cross, to get food for our people”. [FGD-2]

The participants narrated the utilization of a big truck as a makeshift living and selling space during severe flooding. With water levels reaching up to neck height in homes, shops, and on roads, the community repurposes a truck to provide a safe and elevated platform for living and conducting businesses. This adaptive strategy did not only address the challenges of transportation but also served as a makeshift marketplace, emphasizing the community’s ability to improvise in the face of extreme flood conditions.

“We used a big truck to get people, goods, and sellers across the flooded roads during the last flood… Because there was so much water, we lived and sold things on trucks. The water was up to our necks in homes, shops, and on the roads … Cars were swept away by the flood.” [IDI-12]

Some participants described a unique approach to safeguarding goods during floods by elevating them in tall trees covered with nets. This unconventional storage method, along with some individuals resorting to sleeping on trees during the floods, demonstrated a practical adaptation to protect valuable possessions and ensure access to essential resources.

“We took our food out of our stores and put-up nets across the tops of tall trees to store it and other things we wanted to sell … During the floods, some of us slept on the trees.” [FGD-1]

Some participants share a story of seeking refuge in an unfinished three-story building during the 2022 flood. While not free, the building served as a temporary shelter and sales point for stored goods, particularly food. This adaptive use of the building underscores the community’s ability to find alternative spaces and leverage resources, even in the midst of a crisis.

“During the flood of 2022, I moved from my home and shop to a three-story building that wasn't finished yet… The unfinished story building wasn't free. It cost us N3000 (approximately $3.6) a night … We stored our goods, mostly food, and sold them on top of the building.” [IDI-3]

Collectively, these responses demonstrated the resilience and ingenuity of the community in developing creative solutions to overcome the challenges imposed by flooding, reflecting a resourceful approach to adapt to and endure adverse environmental conditions.

5 Discussion

This study provides valuable insights into the challenges faced by women traders in the riverine areas of Bayelsa State, Nigeria, amid climate change-induced flooding. The findings highlight the multifaceted impacts on various dimensions of the participants’ lives, encompassing economic, social, cultural, and gender inequalities, livelihood disruptions, inadequate infrastructure, and limited access to information. These challenges collectively highlighted the vulnerability of women traders to environmental changes, emphasizing the interconnectedness of environmental, economic, and social factors in determining the outcomes of such events. Aligning with the current study, in a global context, flooding has been identified as one of the most prevalent natural hazards, particularly impactful in low-income countries (Rentschler et al., 2022). A comparable study conducted across 188 countries highlighted the disastrous consequences of flooding, aligning with the challenges observed in Bayelsa State. Additionally, the said study conducted in sub-Saharan Africa emphasized the implications of women’s vulnerability to climate change on social and economic wellbeing (Suhr and Steinert, 2022).

The economic impacts of flooding on women traders were profound, resulting in disruptions in supply chains, damage to goods, and reduced market accessibility. Agriculture-related trading activities, notably the sale of fish, food products, and farm-produced items, faced particular vulnerability, exacerbating economic disparities among women traders. Those who recently acquired substantial quantities of agricultural products experienced the most significant setbacks, particularly as their perishable goods incurred damaged, magnifying existing economic inequalities. This aligns with observations in Zimbabwe, where women’s vulnerability to climate change was noted to have implications on agro-based livelihoods (Chidakwa et al., 2020).

The study provides insights into the broader regional impact of flooding, emphasizing its profound consequences on the economy and food supply. Logistical challenges arising from disrupted transportation routes and the destruction of crucial infrastructure, such as bridges connecting states, add complexity to the regional crisis. This underscores the interconnectedness of environmental challenges and the necessity for regional approaches to climate change adaptation and mitigation. A parallel study conducted in Nigeria highlighted the impacts of climate change on food security, including unpredictable weather, decreased fishery productivity, and limited access to resources and technology (Prince et al., 2023).

Flood events exacerbate existing gender inequalities in the study, affecting women traders’ caregiving responsibilities, decision-making power, and mobility. The loss of financial autonomy for women, coupled with increased dependence on partners, reinforces traditional gender roles. This nuanced understanding of how economic disruptions intensify gender inequalities aligns with findings, emphasizing gender inequality as a main driver of food insecurity (Anugwa et al., 2023). Similarly, a study in Cameroon noted that climate change compromises women’s productivity and increases the burden on their triple roles as farmers, caregivers, and home managers (Fonjong and Zama, 2023).

The study found that the immediate setbacks during flooding events include the loss of inventory, temporary closures of trading spaces, and challenges in securing alternative income sources. Prolonged economic instability resulting from recurrent flooding hinders women traders’ capacity to reinvest in their businesses and limits opportunities for expansion. The loss of inventory emerges as a critical issue, disrupting financial control and impacting the profitability of businesses. These findings emphasize the enduring consequences on livelihoods and the imperative for adaptive strategies to navigate economic challenges. A study across the Global South observed severe destruction of livelihoods due to climate change impacts, exacerbated by socio-economic and political inequalities (Ngcamu, 2023).

Inadequacies in infrastructure, such as the lack of flood-resistant marketplaces and storage facilities, leave businesses and goods vulnerable to destruction during floods. The systemic issue of ill-equipped market setups and poor urban planning perpetuates the cycle of damage caused by floods. The inadequacy of shop buildings to prevent floodwater entry demonstrates the need for improved infrastructure and construction practices that consider environmental challenges. Previous studies in Nigeria have identified flooding and building collapse as common disasters, with vulnerability concentrated among females, children, and low-income earners (Ogunleye et al., 2023). Similarly, in Cameroon, assets affecting farmers’ livelihood resilience to climate change included ownership of farm equipment and use of local irrigation systems, emphasizing the role of indigenous knowledge (Awazi et al., 2023).

Challenges in accessing timely and accurate weather information inhibit women traders’ ability to make informed decisions about trading activities. The unpredictability of flood events and limited access to technology contribute to information disparities, with reliance on word-of-mouth increasing the risk of delayed or inaccurate information dissemination. The study emphasizes the critical need for improved communication channels and timely dissemination of information to enhance community preparedness. These findings diverge slightly from a previous study in Kenya, where respondents exhibited greater knowledge about climate change (Andersen et al., 2023). In Cameroon, communication for integrated rainfall and water management was a focal point (Nya et al., 2023).

Despite the challenges, women traders demonstrate resilience through various adaptive strategies. Diversification of income sources, financial planning, and engagement in multiple types of trading activities provide flexibility and risk management during floods. Community solidarity and collective narratives emerge as crucial coping mechanisms, offering emotional support and a sense of belonging. Local adaptive strategies and technologies, such as elevated market stalls and the use of indigenous knowledge, contribute to community resilience, showcasing the resourcefulness and creativity of the community in the face of environmental challenges. Similar studies in coastal Bangladesh and South Africa underscore the importance of socio-cultural adaptation responses and the influence of individual and household socioeconomic factors in navigating climate change (Rabbani et al., 2022; Xiao et al., 2022).

In exploring intersectionality, the study revealed that age intertwines with gender to influence vulnerability and coping strategies. Older women traders, typically belonging to the age range of 46–71 years and with lower levels of education, were more vulnerable to the impacts of flooding due to several factors. They had fewer resources and less mobility to adapt quickly to changing circumstances, as highlighted by their reliance on primary education and their involvement in various trading types, including fish mongering and provision stores. Moreover, older women faced greater economic disparities, as seen in their accounts of losing inventory during floods and struggling to recover financially without adequate coping mechanisms. Economic losses were particularly detrimental to those who lacked formal education, as they had limited access to alternative income sources or financial support systems, as exemplified by the challenges faced by traders with primary/none education levels in restarting their businesses after floods. Conversely, younger women traders, typically between the ages of 27–44 years and with higher levels of education, demonstrated a higher propensity for employing coping strategies to mitigate the impacts of flooding. They engaged in diversification of income sources, such as selling different types of goods or investing in financial establishments, to safeguard against the loss of inventory during floods. Additionally, younger women traders exhibited adaptability and innovation by leveraging community solidarity and local adaptive strategies. They participated in collective narratives to share experiences and provide mutual support, as well as innovate solutions such as using long ropes to cross flooded rivers or storing goods in tall trees during floods. This age disparity underscores how younger women, with relatively higher levels of education and greater access to information, are better equipped to navigate the challenges posed by climate change-induced flooding and develop adaptive strategies to sustain their livelihoods. Similar findings have been echoed in previous research conducted in Bangladesh (Anik et al., 2023), Ghana (Damte et al., 2023), and Kenya (Lelenguyah et al., 2022) illuminating the interplay between age, education, income, and environmental adversities, as well as the coping mechanisms adopted by individuals facing climate change-related issues.

6 Limitations

The study was limited to a specific geographical context (Bayelsa State) and may not be fully generalizable to other regions. The research also relied on self-reported experiences, which may be subject to individual interpretation and recall bias. The study was also cross-sectional lacking the benefits of a longitudinal study. Future research conducting longitudinal studies can provide insights into the evolving nature of challenges faced by women traders and the effectiveness of adaptive strategies over time. This will enhance the understanding of the dynamic relationship between climate change impacts and livelihood resilience.

7 Implications for policy

Policymakers should prioritize investments in resilient infrastructure, including flood-resistant marketplaces and storage facilities. This can safeguard women traders’ businesses during flooding events and contribute to the overall economic resilience of the community. Policies should focus on improving women traders’ access to timely and accurate climate information. This can empower them to make informed decisions about trading activities, ensuring better preparedness for impending weather events. Policy frameworks need to adopt a gender-responsive approach, recognizing the specific challenges faced by women traders and tailoring interventions accordingly. This includes addressing gender inequalities, promoting women’s participation in decision-making processes, and providing targeted support. Support should be directed toward the establishment of community-based early warning systems. These systems can enhance the community’s ability to anticipate and respond to climate change-induced flooding, fostering a proactive rather than reactive approach. Initiatives aimed at capacity building and training programs should be designed to equip women traders with the skills and knowledge necessary for climate-resilient practices. This includes training in adaptive agricultural techniques, diversified trading strategies, and financial literacy. Policymakers should facilitate the creation of collaborative platforms where women traders can exchange information, share best practices, and collectively address challenges. This can enhance community resilience through knowledge sharing and mutual support. Implementing these research policy implications can contribute to the development of sustainable, gender-sensitive strategies that empower women traders in the riverine areas of Bayelsa State to adapt and thrive in the face of climate change-induced flooding.

8 Conclusion

The study highlights the complex interplay of environmental, economic, and social factors in shaping the experiences of women traders in the face of climate change-induced flooding. While it reveals the vulnerabilities faced by these women, it also illuminates their remarkable resilience and resourcefulness in navigating adversity. By delving deeper into the lived experiences of the women traders, the study unearths nuanced insights that can inform tailored interventions, including how material conditions intersect with cultural specificity to shape livelihoods and adaptive strategies. It underscores the pivotal role of community solidarity, collective narratives, and adaptive innovations in mitigating the impacts of environmental challenges. It recognizes the significance of community support networks in providing emotional sustenance and fostering a sense of belonging. These insights emphasize the importance of grassroots initiatives and local knowledge in climate change adaptation efforts. Consequently, this study advocates for holistic and context-specific strategies for climate change adaptation, particularly tailored to the unique challenges faced by women in riverine communities. By leveraging community collective actions, adaptive strategies, and support networks, policymakers and stakeholders can develop interventions that address the multifaceted dimensions of climate change impact on vulnerable populations. Through collaborative efforts and informed policy decisions, Nigeria can strive toward building more resilient and sustainable communities that prioritize the well-being of all individuals, especially women most vulnerable to environmental change. Future research should investigate how neoliberal policies and globalization influence women’s aspirations within natural resource-based livelihoods, to offer a deeper understanding of the socio-economic dynamics at play. Exploring this dimension will further highlight how external influences intersect with local realities to shape the aspirations, values, and decision-making processes of women traders facing environmental challenges.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics and Research Review Board of Federal University Oye-Ekiti, Nigeria. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

TM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

Sincere appreciation goes to all participants for their time and cooperation in providing the responses that served as the foundation for the data in this study. Their valuable contributions have been instrumental in shaping the insights and findings presented in this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abel, M. H. (2002). Humor, stress, and coping strategies. Humor 15, 365–381. doi: 10.1515/humr.15.4.365

Akinbami, C. A. O. (2021). Migration and climate change impacts on rural entrepreneurs in Nigeria: a gender perspective. Sustainability (Switzerland) 13:8882. doi: 10.3390/su13168882

Andersen, J. G., Kallestrup, P., Karekezi, C., Yonga, G., and Kraef, C. (2023). Climate change and health risks in Mukuru informal settlement in Nairobi, Kenya – knowledge, attitudes and practices among residents. BMC Public Health 23:393. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-15281-y

Anik, A. H., Sultan, M. B., Alam, M., Parvin, F., Ali, M. M., and Tareq, S. M. (2023). The impact of climate change on water resources and associated health risks in Bangladesh: a review. Water Secur. 18:100133. doi: 10.1016/j.wasec.2023.100133

Anugwa, I. Q., Obossou, E. A. R., Onyeneke, R. U., and Chah, J. M. (2023). Gender perspectives in vulnerability of Nigeria’s agriculture to climate change impacts: a systematic review. Geo J. 88, 1139–1155. doi: 10.1007/s10708-022-10638-z

Ariyaningsih Sukhwani, V. S., and Shaw, R. (2023). Vulnerability assessment of Balikpapan (Indonesia) for climate change-induced urban flooding. Int. J. Disaster Resil. Built. Environ. 14, 387–401. doi: 10.1108/IJDRBE-08-2021-0111

Awazi, N. P., Quandt, A., and Kimengsi, J. N. (2023). Endogenous livelihood assets and climate change resilience in the Mezam highlands of Cameroon. Geo J. 88, 2491–2508. doi: 10.1007/s10708-022-10755-9

Berezi, O. K., Obafemi, A., and Nwankwoala, H. O. (2019). Flood vulnerability assessment of communities in the flood prone areas of Bayelsa state, Nigeria. International Journal of Geology and Earth Sciences 5. Available at: www.ijges.com (Accessed January 5, 2024).

Castleberry, A., and Nolen, A. (2018). Thematic analysis of qualitative research data: is it as easy as it sounds? Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 10, 807–815. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2018.03.019

Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters. (2020). Natural disasters 2019: Now is the time to not give up. UNDRR PreventionWeb. Available at: https://www.preventionweb.net/publication/natural-disasters-2019-now-time-not-give (Accessed January 2, 2024)

Cheng, C., Yang, Y. C. E., Ryan, R., Yu, Q., and Brabec, E. (2017). Assessing climate change-induced flooding mitigation for adaptation in Boston’s Charles River watershed, USA. Landsc. Urban Plan. 167, 25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2017.05.019

Chidakwa, P., Mabhena, C., Mucherera, B., Chikuni, J., and Mudavanhu, C. (2020). Women’s vulnerability to climate change: gender-skewed implications on agro-based livelihoods in rural Zvishavane, Zimbabwe. Indian J. Gend. Stud. 27, 259–281. doi: 10.1177/0971521520910969

Damte, E., Manteaw, B. O., and Wrigley-Asante, C. (2023). Urbanization, climate change and health vulnerabilities in slum communities in Ghana. J. Clim. Change Health 10:100189. doi: 10.1016/j.joclim.2022.100189

Ejike, E. (2022). NiMet predicts heavy flooding in Bayelsa, Borno, Delta, Kaduna. Leadership. Available at: https://leadership.ng/nimet-predicts-heavy-flooding-in-bayelsa-borno-delta-kaduna/ (Accessed January 2, 2024)

Elum, Z. A., and Snijder, M. (2023). Climate change perception and adaptation among farmers in coastal communities of Bayelsa state, Nigeria: a photovoice study. Int. J. Clim. Chang. Strateg. Manag. 15, 745–767. doi: 10.1108/IJCCSM-07-2022-0100

England, K. V. L. (1994). Getting personal: reflexivity, positionality, and feminist research∗. Prof. Geogr. 46, 80–89. doi: 10.1111/j.0033-0124.1994.00080.x

Filho, W. L., Nagy, G. J., Setti, A. F. F., Sharifi, A., Donkor, F. K., Batista, K., et al. (2023). Handling the impacts of climate change on soil biodiversity. Sci. Total Environ. 869:161671. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.161671

Fonjong, L., and Zama, R. N. (2023). Climate change, water availability, and the burden of rural women’s triple role in Muyuka, Cameroon. Global Environ. Change 82:102709. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2023.102709

Helkkula, A., Kelleher, C., and Pihlström, M. (2012). Practices and experiences: challenges and opportunities for value research. J. Serv. Manag. 23, 554–570. doi: 10.1108/09564231211260413

Hilton, R. H. (1984). Women traders in medieval England. Womens Stud. 11, 139–155. doi: 10.1080/00497878.1984.9978607

Ibrahim, B., and Mensah, H. (2022). Rethinking climate migration in sub-Saharan Africa from the perspective of tripartite drivers of climate change. SN Social Sci. 2:383. doi: 10.1007/s43545-022-00383-y

Jansson, J. K., and Wu, R. (2023). Soil viral diversity, ecology and climate change. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 21, 296–311. doi: 10.1038/s41579-022-00811-z

Khan, A. R., Ratele, K., Dery, I., and Khandaker, S. (2023). Men and climate change: some thoughts on South Africa and Bangladesh. NORMA 18, 137–153. doi: 10.1080/18902138.2022.2077082

Lelenguyah, G. L., Nyangito, M. M., Wasonga, O. V., and Bett, R. C. (2022). Herders’ perspectives on climate variability and livestock diseases trends in the semiarid rangelands of northern Kenya. Int. J. Clim. Change 15, 69–88. doi: 10.18848/1835-7156/CGP/v15i02/69-88

Michael, T. O. (2024). A qualitative exploration of the influence of climate change on migration of women in the riverine area of Bayelsa state, Nigeria. Soc. Sci. 13:89. doi: 10.3390/socsci13020089

Michael, T. O., and Ekpenyong, A. S. (2018). The polygyny-fertility hypothesis: new evidences from Nigeria. Nigerian J. Sociol. Anthropol. 16:101. doi: 10.36108/NJSA/8102/61(0101)

Michael, T. O., and Odeyemi, M. A. (2017). Nigeria’s population policies: issues, challenges and prospects. Ibadan J. Soc. Sci. 15:101. doi: 10.36108/ijss/7102.51.0101

Muzvidziwa, V. (2001). Zimbabwe’s cross-border women traders: multiple identities and responses to new challenges. J. Contemp. Afr. Stud. 19, 67–80. doi: 10.1080/02589000124044

National Bureau of Statistics (2020). Demographic statistics bulletin. Abuja. Available at: file:///C:/Users/Admi/Downloads/DEMOGRAPHIC%20BULLETIN%202020%20(1).pdf (Accessed January 2, 2024)

Ngcamu, B. S. (2023). Climate change effects on vulnerable populations in the global south: a systematic review. Nat. Hazards 118, 977–991. doi: 10.1007/s11069-023-06070-2

Ntali, Y. M., Lyimo, J. G., and Dakyaga, F. (2023). Trends, impacts, and local responses to drought stress in Diamare division, northern Cameroon. World Dev. Sustain. 2:100040. doi: 10.1016/j.wds.2022.100040

Nya, E. L., Mwamila, T. B., Komguem-Poneabo, L., Njomou-Ngounou, E. L., Fangang-Fanseu, J., Tchoumbe, R. R., et al. (2023). Integrated water Management in Mountain Communities: the case of Feutap in the municipality of Bangangté, Cameroon. Water (Switzerland) 15:1467. doi: 10.3390/w15081467

O’Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., and Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 89, 1245–1251. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388

Ogunleye, O., Arohunsoro, S., and Ibitoye, O. (2023). Disaster vulnerability and poverty level among residents of Lagos state, Nigeria. Int. J. Disaster Dev. Interface 3, 17–34. doi: 10.53824/ijddi.v3i2.51

Ongoma, V., and Dike, V. (2023). Flooding in Nigeria is on the rise – good forecasts, drains and risk maps are urgently needed. Conversation Media Group PreventionWeb. Available at: https://www.preventionweb.net/news/flooding-nigeria-rise-good-forecasts-drains-and-risk-maps-are-urgently-needed (Accessed January 2, 2024)

Otto, F. E. L., Zachariah, M., Saeed, F., Siddiqi, A., Kamil, S., Mushtaq, H., et al. (2023). Climate change increased extreme monsoon rainfall, flooding highly vulnerable communities in Pakistan. Environ. Res. 2:025001. doi: 10.1088/2752-5295/acbfd5

Pautz, A. (2011). “What are the contents of experiences?” in The admissible contents of experience. eds. K. Hawley and F. Macpherson (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley), 114–138.

Perelli, C., Cacchiarelli, L., Peveri, V., and Branca, G. (2024). Gender equality and sustainable development: a cross-country study on women’s contribution to the adoption of the climate-smart agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa. Ecol. Econ. 219:108145. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2024.108145

Petracca, M., Ciabatta, L., Fairbairn, D., Wagner, W., Roth, F., Vreugdenhil, M., et al. (2022). In October, flooding in Nigeria’s south submerged homes and farmland, and displaced hundreds of thousands of people. EUMETSAT. Available at: https://www.eumetsat.int/severe-flooding-nigeria (Accessed January 2, 2024)

Praag, L. V., Lietaer, S., and Michellier, C. (2022). A qualitative study on how perceptions of environmental changes are linked to migration in Morocco, Senegal, and DR Congo. Hum. Ecol. 50, 347–361. doi: 10.1007/s10745-021-00278-1

Prince, A. I., Obiorah, J., and Ogar, E. E. (2023). Analyzing the critical impact of climate change on agriculture and food security in Nigeria. Int. J. Agric. Earth Sci. 9:42023. doi: 10.56201/ijaes.v9.no4.2023.pg1.27

Rabbani, M. M. G., Cotton, M., and Friend, R. (2022). Climate change and non-migration — exploring the role of place relations in rural and coastal Bangladesh. Popul. Environ. 44, 99–122. doi: 10.1007/s11111-022-00402-3

Ray, C., Lindop, J., and Gibson, S. (1982). The concept of coping. Psychol. Med. 12, 385–395. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700046729

Rentschler, J., Salhab, M., and Jafino, B. A. (2022). Flood exposure and poverty in 188 countries. Nat. Commun. 13:3527. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-30727-4

Rolfe, G. (2006). Validity, trustworthiness and rigour: quality and the idea of qualitative research. J. Adv. Nurs. 53, 304–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03727.x

Shu, E. G., Porter, J. R., Hauer, M. E., Sandoval Olascoaga, S., Gourevitch, J., Wilson, B., et al. (2023). Integrating climate change induced flood risk into future population projections. Nat. Commun. 14:7870. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-43493-8

Suhr, F., and Steinert, J. I. (2022). Epidemiology of floods in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review of health outcomes. BMC Public Health 22:12584. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-12584-4

Tan, J., Zhou, K., Peng, L., and Lin, L. (2022). The role of social networks in relocation induced by climate-related hazards: an empirical investigation in China. Clim. Dev. 14, 1–12. doi: 10.1080/17565529.2021.1877102

Tonye-Scent, G. A., and Uzobo, E. (2020). Health insecurity among internally displaced persons in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria. Nigerian J. Sociol. Anthropol. 18, 48–61. doi: 10.36108/NJSA/0202/81(0230)

UN Environment Programme (2024). How climate change is making record-breaking floods the new normal. UN Environment Programme. Available at: https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/how-climate-change-making-record-breaking-floods-new-normal (Accessed January 2, 2024)

United Nations (2023). COP28 UAE: Everything you need to know about this year’s biggest climate conference. United Nations. Available at: https://www.cop28.com/en/news-and-media/cop28-uae-everything-you-need-to-know-about-this-years-biggest-climate-conference (Accessed December 28, 2023)

United Nations Development Programme (2024). Climate change’s impact on coastal flooding to increase five times over this century. UNDP human development report. Available at: https://hdr.undp.org/content/climate-changes-impact-coastal-flooding-increase-five-times-over-century (Accessed January 2, 2024)

Vinke, K., Rottmann, S., Gornott, C., Zabre, P., Nayna Schwerdtle, P., and Sauerborn, R. (2022). Is migration an effective adaptation to climate-related agricultural distress in sub-Saharan Africa? Popul. Environ. 43, 319–345. doi: 10.1007/s11111-021-00393-7

Wilson, C., Janes, G., and Williams, J. (2022). Identity, positionality and reflexivity: relevance and application to research paramedics. Br. Paramed. J. 7, 43–49. doi: 10.29045/14784726.2022.09.7.2.43

Xiao, T., Oppenheimer, M., He, X., and Mastrorillo, M. (2022). Complex climate and network effects on internal migration in South Africa revealed by a network model. Popul. Environ. 43, 289–318. doi: 10.1007/s11111-021-00392-8

Keywords: climate change, flooding, experiences, adaptations, women traders