- Higher Colleges of Technology, Ras Al Khaimah, United Arab Emirates

Introduction: Greenwashing in sustainable finance involves misleading portrayals of investment products as environmentally friendly. This study explores the prevalence of greenwashing, its forms, impacts, and potential remedies. It underscores the need to align investor values with genuine environmental sustainability, emphasizing the pitfalls of greenwashing in sustainable finance.

Methods: The study employs a scoping review methodology guided by the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) framework. It involves systematically searching, selecting, and synthesizing evidence from various databases and sources to map critical concepts, types of evidence, and research gaps in greenwashing within sustainable finance.

Results: The study reveals diverse greenwashing strategies across industries, including ambiguous language, irrelevant claims, and opacity. It highlights greenwashing’s severe consequences on corporate reputation, financial performance, and stakeholder trust. The effectiveness of regulatory bodies, Non-Governmental Organizations, and certifications in curbing greenwashing is discussed, though their effectiveness is debatable. The research also examines greenwashing’s impact on investor behavior and decision-making.

Discussion: This research contributes to understanding greenwashing in sustainable finance, emphasizing vigilance, transparency, and accountability. It calls for more stringent regulations, international cooperation, and public awareness to combat greenwashing effectively. The study also suggests that businesses should adopt genuine and transparent environmental practices to avoid the risks of greenwashing, including legal repercussions. For future research, the study proposes a deeper exploration of the mechanisms enabling greenwashing and the effectiveness of different regulatory strategies and measures to combat it.

1 Introduction

Greenwashing, a term coined in the 1980s, is a deceptive practice where a company or an organization spends more time and resources on marketing themselves as environmentally friendly and minimizing their environmental impact (Delmas and Burbano, 2011). It involves disseminating misleading information to create an overly optimistic image of the company’s environmental practices or products. In sustainable finance, greenwashing refers to misrepresenting investment products as environmentally friendly when they are not, leading to a false perception of a company’s commitment to environmental sustainability (Schneider-Maunoury, 2023).

Greenwashing can take various forms, such as vague language, irrelevant claims, false labels, and lack of transparency. For instance, a company might label its products as all-natural, green, or eco-friendly without providing any concrete evidence or certification to support these claims (Bowen and Aragon-Correa, 2014). Green bonds are a common area where greenwashing can occur in sustainable finance. These are bonds where the proceeds are used to fund environmentally friendly projects. However, companies can mislead investors about using funds without proper regulation and transparency, leading to greenwashing (Karpf and Mandel, 2017).

Real-life examples of greenwashing in sustainable finance are common. For instance, Volkswagen, a prominent automobile company, admitted to cheating emissions tests by fitting various vehicles with a “defect” device. This device could detect when the car was undergoing an emissions test and alter the performance to reduce emissions. This scheme happened while the company publicly touted its vehicles’ low-emissions and eco-friendly features in marketing campaigns (Robinson, 2023).

For several reasons, the study of greenwashing in sustainable finance is paramount in the current context. First, with the increasing awareness and concern about environmental issues, more investors seek to align their investment decisions with their ecological values (Richardson and Cragg, 2010). This alignment has led to a surge in demand for sustainable investment products. However, the lack of standardization and regulation in what constitutes a green or sustainable investment has created an environment ripe for greenwashing (Bauer and Hann, 2010).

Second, greenwashing can undermine the credibility of the sustainable finance market and hinder the transition to a low-carbon economy. If investors cannot trust the environmental claims made by companies, they may become reluctant to invest in sustainable products, slowing the flow of capital to genuinely sustainable projects (Gillenwater, 2008).

Third, greenwashing can lead to an inefficient allocation of resources. Investors need to be more informed about directing their funds toward sustainable projects. In contrast, projects that could make a real difference in environmental impact need to be noticed (Kozlowski et al., 2015).

An illustrative example that underscores this study’s significance is the case of the multinational investment bank JP Morgan Chase. In 2020, the Rainforest Action Network (RAN) reported that JP Morgan Chase was the world’s leading financier of fossil fuels despite its claims of being a leader in sustainable finance. The bank has provided over $268 billion in financing to fossil fuel companies since the Paris Agreement was signed in 2016, contradicting its public commitment to sustainability and climate change mitigation (RAN, 2020). This case highlights the urgent need for increased transparency and regulation in sustainable finance to prevent greenwashing and ensure investors’ funds genuinely contribute to environmental sustainability.

This research aims to answer the following questions:

• What are the prevalent forms of greenwashing in sustainable finance, and how do they manifest in different sectors?

• How does greenwashing affect the credibility and functioning of the sustainable finance market?

• What are the potential measures to combat greenwashing in sustainable finance, and how effective are they?

• How does greenwashing in sustainable finance affect investor behavior and decision-making?

These questions are designed to provide a comprehensive understanding of greenwashing in sustainable finance, its implications, and potential solutions. For instance, a study by Cosgrove et al. (2023) emphasizes robust, science-based metrics and cost-effective data collection and monitoring systems to safeguard sustainable finance against greenwashing. This research topic aligns with our research question on potential measures to combat greenwashing.

The significance of this article within the broader framework of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provides a vital perspective on its significance and impact. The article explores greenwashing in sustainable finance directly aligning with several SDGs, particularly Goal 12: Responsible Consumption and Production and Goal 13: Climate Action. By scrutinizing the prevalence and consequences of greenwashing, this research contributes to a deeper understanding of how deceptive environmental claims can undermine efforts toward sustainable consumption and production patterns, as highlighted in SDG 12. It underscores the critical need for transparency, accountability, and genuinely sustainable practices in financial investments to ensure that they contribute effectively to environmental sustainability.

Moreover, the study’s focus on sustainable finance as a vehicle for combating greenwashing resonates with the urgent objectives of SDG 13, which calls for immediate action to combat climate change and its impacts. By revealing the intricate dynamics of greenwashing within the sustainable finance sector, this study illuminates the challenges and opportunities in directing financial flows toward truly sustainable projects that can mitigate climate change. This alignment with the SDGs emphasizes the article’s relevance to global sustainability efforts, highlighting the importance of rigorous, science-based approaches for achieving a sustainable and resilient future. Through this lens, the article not only contributes to academic discourse but also to the practical and policy-oriented efforts aimed at realizing the United Nations’ vision for a sustainable world.

Our study’s investigation into the intricate dynamics of greenwashing within sustainable finance is significant and relevant to a global audience. It transcends geographical, cultural, and economic boundaries as the world grapples with the escalating challenges of climate change, resource depletion, and social inequality. The role of finance in fostering sustainable development has never been more critical. This article sheds light on how deceptive greenwashing practices can undermine the integrity of sustainable finance, mislead stakeholders, and divert resources away from genuine sustainability projects. By offering a comprehensive analysis of greenwashing practices, their impact on investor trust, and the effectiveness of regulatory frameworks in various contexts, this research provides valuable insights for policymakers, investors, academics, and practitioners worldwide. It invites a global dialog on enhancing transparency and accountability in sustainable finance, making it an indispensable resource for anyone committed to advancing environmental sustainability and social responsibility across the globe. Our findings and discussions are both timely and crucial for informing global efforts to align financial mechanisms with the broader goals of sustainable development, making our study an essential contribution to the worldwide discourse on sustainable finance.

The structure of this paper is designed to systematically explore and dissect the multifaceted issue of greenwashing within sustainable finance. Following this introduction, the Methods section delineates the scoping review methodology adopted, employing the PRISMA framework to ensure a thorough and systematic analysis of relevant literature, mapping out the key concepts, types of evidence, and research gaps related to greenwashing in sustainable finance. The Results section presents a synthesis of the findings from the scoping review, revealing the diversity of greenwashing strategies, their consequences, and the debatable effectiveness of various actors like regulatory bodies and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) in mitigating these practices. This section also delves into how greenwashing influences investor behavior and decision-making processes.

In the Discussion segment, we critically examine the implications of our findings, emphasizing the necessity for increased vigilance, transparency, and accountability to combat greenwashing effectively. This part argues for enhanced regulations, international cooperation, and heightened public awareness as indispensable measures to counteract greenwashing. We also discuss businesses’ responsibility to adopt transparent and genuine environmental practices to mitigate the risks of greenwashing, including legal repercussions. The Conclusion consolidates our study’s insights, summarizing the pervasive nature of greenwashing across sectors, its impact on corporate reputation and stakeholder trust, and the urgent need for more effective strategies to combat it. Finally, we outline the limitations of our study and propose directions for future research, mainly focusing on exploring the mechanisms enabling greenwashing and assessing the efficacy of different regulatory and preventative measures.

2 Methods

This study uses a scoping review methodology to explore greenwashing in sustainable finance. A scoping review is a form of knowledge synthesis that addresses an exploratory research question aimed at mapping key concepts, types of evidence, and research gaps related to a defined area or field by systematically searching, selecting, and synthesizing existing knowledge (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005). This methodology is beneficial for complex or emerging evidence, such as greenwashing in sustainable finance, where many different study designs might be applicable.

The scoping review methodology is guided by the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Tricco et al., 2018). This framework provides a rigorous and transparent approach to conducting scoping reviews, ensuring that the process is replicable and the findings are reliable.

The scoping review methodology is appropriate for this study as it allows for a broad exploration of the concept of greenwashing in sustainable finance. It enables the identification of the primary sources and types of evidence available, examining how research on this topic is conducted, and understanding the key findings in the field. This methodology also allows for identifying gaps in the existing literature, which can inform future research directions (Cosgrove et al., 2023).

Identifying relevant literature involves systematically searching multiple databases and sources to ensure a comprehensive review of the evidence. The search strategy aims to answer the research question and includes a combination of keywords and Boolean operators to capture all relevant studies. The search is conducted in databases such as PubMed, Web of Science, IEEE Xplore, Scopus, Google Scholar, ACM Digital Library, ScienceDirect, JSTOR, ProQuest, SpringerLink, EBSCOhost, ERIC. The examined databases also included Business Source Complete, Emerald Insight, SAGE Journals, Social Science Research Network (SSRN), Wiley Online Library, Taylor & Francis Online, CAB Abstracts, ResearchGate, Oxford Academic Journals, Nature Research, EconLit, GreenFILE, PsycINFO, Philosopher’s Index, AGRIS, LexisNexis Academic, Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ), and BioOne. The explored databases also comprised WorldWideScience, Social Sciences Citation Index, CINAHL, Project MUSE, Agricola, Environmental Sciences and Pollution Management, PAIS Index, Zetoc, The Sustainability Science Abstracts, Eldis, SAO/NASA Astrophysics Data System, Inspec, ArXiv, OpenGrey, Environmental Science Database, Sociological Abstracts, AgEcon Search, Oceanic Abstracts, Transport Research International Documentation, and Biodiversity Heritage Library.

A meticulously crafted search strategy was employed across the databases listed above to capture the relevant literature for our study. This strategy combined keywords related to the core themes of greenwashing and sustainable finance alongside Boolean operators to refine the search results. The primary keywords included ‘greenwashing,’ ‘sustainable finance,’ ‘ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance),’ ‘sustainability,’ ‘CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility),’ and ‘governance.’ These terms were paired with Boolean operators to expand, limit, or define the search. For instance:

The term ‘greenwashing’ was combined with ‘sustainable finance’ using the AND operator (greenwashing AND sustainable finance) to identify literature directly addressing greenwashing within sustainable finance.

To encompass broader discussions related to environmental and social governance, the OR operator was employed, linking ESG-related terms (ESG OR environmental social governance OR sustainability OR CSR).

The NOT operator was used sparingly to exclude irrelevant results, such as articles focusing solely on generic marketing strategies without a direct link to environmental claims (e.g., marketing NOT greenwashing).

Additionally, specific phrases were enclosed in quotation marks to ensure that the search engines retrieved articles where these terms appeared as exact phrases, enhancing the relevance of the search results. For example, “corporate social responsibility” and “environmental sustainability” were quoted to target literature discussing these precise concepts.

The search was refined by including filters for peer-reviewed articles, reports, and grey literature to ensure the sources’ academic rigor and relevance. This comprehensive and iterative approach, combining keywords and Boolean operators, facilitated a thorough and systematic exploration of the existing body of knowledge on greenwashing in sustainable finance. This strategy was designed to be inclusive, capture a broad spectrum of relevant literature, and be precise, minimizing the inclusion of tangential or unrelated studies.

The criteria utilized to include or exclude literature in our study followed a rigorous and systematic approach guided by the PRISMA framework explained above to ensure a comprehensive and relevant review of existing knowledge. The inclusion criteria included the following:

• Topical Relevance: Articles, reports, and grey literature that directly addressed the phenomena of greenwashing within the context of sustainable finance were included. This relevance was determined by examining abstracts and keywords, focusing on studies exploring the strategies, impacts, and remedies of greenwashing.

• Publication Date: Given the evolving nature of sustainable finance and greenwashing practices, recent publications from the last two decades (2004–2024) were prioritized to ensure the most current understanding of the topic.

• Peer-Reviewed Articles: Priority was given to peer-reviewed journal articles to maintain academic rigor and credibility. However, significant reports and grey literature from reputable sources were also considered to capture a broad spectrum of insights and perspectives.

• Language: The search was limited to literature published in English to ensure the feasibility of the research team’s thorough analysis.

• Availability: Articles that were accessible in full-text form and could be retrieved through database subscriptions, open access, or institutional sources were included to ensure a detailed review of the content.

The exclusion criteria comprised the following:

• Irrelevance to Sustainable Finance: Studies that mentioned greenwashing in contexts unrelated to finance, such as pure marketing strategies or product labeling without a clear link to investment or financial products, were excluded.

• Outdated Studies: Older studies, while potentially valuable historically, were excluded to maintain a focus on the current state of greenwashing within sustainable finance.

• Non-English Literature: Articles not published in English were excluded due to the language capabilities of the research team.

• Incomplete or Abstract-only Publications: Studies for which only abstracts were available or incomplete were excluded, as these did not provide sufficient detail for analysis.

• Duplicate Studies: To ensure a unique dataset, duplicates or multiple reports of the same study across different databases were identified and excluded.

This strategic approach to inclusion and exclusion ensured the compilation of a comprehensive, relevant, and up-to-date dataset that forms the basis for analyzing the prevalence, forms, and impacts of greenwashing in sustainable finance, along with potential remedies.

The search strategy was iterative, refined, and adjusted as new relevant studies were identified. Hand-searching reference lists of included studies also supplemented the search and pertinent reviews to identify any additional studies that may have been missed in the database search (Mishra et al., 2023).

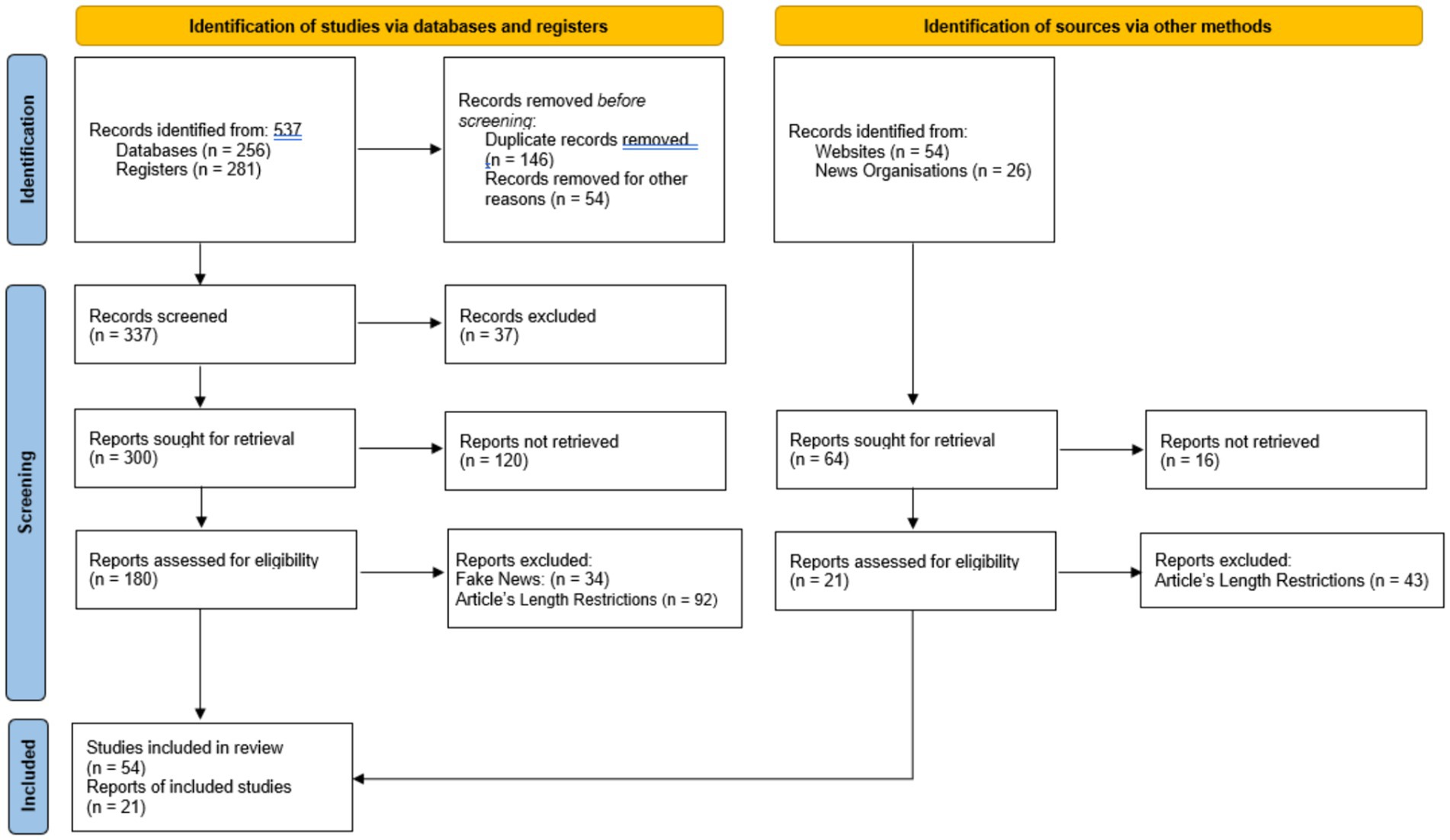

Figure 1 delineates the article selection process, detailing the initial identification, exclusions based on title and abstract, and further exclusions following a full-text review. It also presents the final count of articles included in the analysis and the rationale for exclusion at each stage. In the first phase, labeled as “Identification of sources via other methods,” we identified 80 records, which included 54 from various online platforms and 26 from institutional sources. Out of these, we aimed to retrieve 64 papers, while the remaining 16 were disregarded, as they needed to meet the inclusion criteria. We successfully retrieved 31 records, and after assessing their eligibility, we excluded 33 due to the constraints of article length, resulting in 31 articles being incorporated into the review.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram. Source: Page et al. (2021). http://www.prisma-statement.org/.

In the second phase, “Identification of studies via databases and registers,” we initially identified 537 records, with 256 documents from various databases and 281 records from registers. Before the screening process, we eliminated 200 papers: 146 due to duplication and 54 for miscellaneous reasons. This selection left us with 337 records for screening, from which 37 were excluded, as they needed to meet the inclusion criteria. We aimed to retrieve 300 papers post-screening, but 120 were not retrieved due to the exclusion criteria. We assessed the eligibility of the remaining 180 records, and 126 were excluded: 34 were identified as misinformation, and 92 due to the article’s length restrictions. This screening included 54 articles from the databases and registers and 21 from alternative sources, resulting in 75 secondary sources for our analysis.

Once the relevant literature is identified, it is analyzed and synthesized to answer the research question. This process involves extracting data from the included studies, such as study characteristics, methods, and critical findings. The data extraction process is systematic and is guided by a predefined data extraction form to ensure consistency.

The extracted data is then synthesized to provide an overview of the evidence. The synthesis can involve a narrative description of the findings, thematic analysis, or a combination of both, depending on the nature of the evidence. The synthesis provides insights into the concept of greenwashing in sustainable finance, including its forms, tactics, impacts, and the strategies companies use to engage in greenwashing (Khmyz, 2023).

Our thematic analysis is a method of synthesizing extracted data alongside or as an alternative to narrative descriptions. This methodological approach is tailored to the nature of the evidence collected. This pertains to our qualitative research methodology employed to detect, examine, and present patterns (themes) within the data. It offers an in-depth and sophisticated comprehension of the data’s substance and foundational ideas or notions.

By employing thematic analysis, we aimed to distill complex information from various sources into coherent, significant themes related to greenwashing practices, their prevalence, impacts, and the effectiveness of existing measures to combat them. This approach allowed us to explore variations and commonalities across the reviewed literature, offering insights into the mechanisms of greenwashing and the multifaceted responses to it within the sustainable finance sector. It also facilitated the identification of gaps in the current body of knowledge and future research efforts toward unexplored or underexplored areas. This approach was particularly suitable for our study’s scope, given its flexibility and applicability to various datasets. It enables a comprehensive synthesis of evidence on a relatively emerging and complex phenomenon like greenwashing in sustainable finance.

The key themes related to greenwashing in sustainable finance considered relevant to writing our article included the following:

• Forms and Tactics of Greenwashing: Corporations employ varied tactics to seem more eco-friendly than they are, including the use of ambiguous terminology, unrelated assertions, and improper application of certifications.

• Drivers of Greenwashing: Factors motivating companies to engage in greenwashing, including the desire to enhance corporate image, respond to stakeholder pressures, and comply with minimal regulatory requirements.

• Impacts on Corporate Reputation and Financial Performance: Greenwashing has short-term and long-term consequences for a company’s reputation among consumers and investors and financial outcomes.

• Stakeholder Perceptions and Behavior: How greenwashing influences the perceptions and behaviors of different stakeholders, including consumers, investors, and regulatory bodies, and their trust in sustainable finance products.

• Regulatory Responses and Effectiveness: This theme encompasses the role of governmental and regulatory bodies in establishing standards, promoting transparency, and enforcing compliance to combat greenwashing and the effectiveness of these measures.

• Role of Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and Institutions: NGOs and institutions contribute to advocating for stronger regulations, raising public awareness, and promoting genuine environmental practices.

• Third-Party Certifications and Eco-Labels: How independent certifications and eco-labels can help mitigate greenwashing by verifying companies’ environmental claims and providing credible information to stakeholders.

• Sector-Specific Examples of Greenwashing: This theme includes instances of greenwashing practices within different sectors, such as automotive, fashion, and energy, illustrating the pervasiveness and variety of greenwashing tactics.

• Challenges and Limitations: Obstacles to effectively combating greenwashing, including regulatory limitations, enforcement challenges, and the complexity of assessing environmental impact.

• Future Directions and Research Needs: This theme highlights areas where further research is needed to better understand, prevent, and respond to greenwashing in sustainable finance, highlight gaps in current knowledge, and suggest new investigative avenues.

These themes, derived from thematic analysis, likely provided a structured framework for discussing greenwashing in sustainable finance, allowing the authors to address the phenomenon’s complexity and multifaceted nature systematically.

Therefore, the scoping review methodology provides a rigorous and systematic approach to exploring greenwashing in sustainable finance. It allows for a comprehensive and in-depth understanding of the topic, informing both theory and practice in the field.

3 Literature review

The phenomenon of greenwashing in sustainable finance has been extensively studied in the literature. Delmas and Burbano (2011) provide a comprehensive analysis of the drivers of greenwashing, highlighting the role of internal and external factors. They argue that companies engage in greenwashing for various reasons, including enhancing their corporate image, responding to stakeholder pressures, and complying with regulatory requirements. Similarly, Walker et al. (2008) explore the drivers and barriers to environmental supply chain management practices, a key area where greenwashing can occur. They find that while significant incentives exist for companies to adopt green practices, substantial barriers exist, including cost and lack of legitimacy.

The impact of greenwashing on corporate reputation and financial performance has also been a significant research focus. For instance, Lyon and Wren Montgomery (2015) find that greenwashing can harm a company’s reputation, leading to loss of consumer trust and potential financial penalties. On the other hand, Parguel et al. (2011) argue that greenwashing can sometimes enhance a company’s financial performance by attracting environmentally conscious consumers and investors. However, this effect will likely be short-lived as consumers become more aware of the company’s deceptive practices.

The role of stakeholders in greenwashing is another crucial theme in the literature. According to Seele and Gatti (2017), stakeholders, particularly consumers and investors, play a vital role in enabling or discouraging greenwashing. They suggest that stakeholders’ perceptions and responses to greenwashing can significantly influence a company’s strategies. Du et al. (2010), who find that consumers’ perceptions of a company’s CSR practices can significantly influence their responses to greenwashing, echo this.

The literature also provides valuable insights into the measures to combat greenwashing. For instance, Marquis et al. (2016) argue for more stringent regulation and standardization in sustainable finance to prevent greenwashing. They suggest that regulatory bodies should be more proactive in monitoring and enforcing compliance with environmental standards. Similarly, Mitchell et al. (2010) highlight the importance of education and awareness in combating greenwashing. They argue that consumers must be more informed about companies’ environmental practices to make more sustainable choices.

The relationship between greenwashing and sustainable development is another critical area of research. According to Laufer (2003), greenwashing can undermine sustainable development by diverting resources from sustainable projects. He argues that greenwashing can create a false perception of sustainability, leading to inefficient allocation of resources. TerraChoice (2010), who finds that greenwashing can lead to cynicism and distrust, supports this among consumers, hindering the adoption of sustainable practices.

Regarding sector-specific analysis, the literature provides evidence of greenwashing across various sectors. For instance, Dauvergne and Lister (2010) examine the prevalence of greenwashing in palm oil, while Lyon and Maxwell (2011) focus on the automobile industry. These studies highlight the pervasive nature of greenwashing and the need for sector-specific strategies to combat it.

The intertwining of greenwashing and sustainable finance is a complex phenomenon that draws upon diverse perspectives, methodologies, and theoretical underpinnings (Netto et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2020). The relationship between technological innovations such as Fintech and sustainable finance is pivotal. Vergara and Agudo (2021) emphasize how digital financial solutions can enhance transparency and consumer protection, potentially mitigating greenwashing practices. This synergy is further explored through the lens of artificial intelligence, where Moodaley and Telukdarie (2023) underscore AI’s capacity to scrutinize sustainability reports for signs of greenwashing, offering a novel pathway to bolster the credibility of corporate environmental disclosures.

Consumer perceptions play a critical role in the dynamics of greenwashing, as evidenced by Wodnicka’s (2023) investigation into how greenwashing influences purchasing decisions, underscoring the necessity for clear communication and authentic sustainable practices. As proposed by Yildirim (2023), the dual nature of greenwashing introduces an intriguing dichotomy, suggesting that while certain practices may be deceptive, others could inadvertently propel companies toward genuine sustainability efforts. The adaptation of fraud accounting models to the realm of greenwashing by Kurpierz and Smith (2020) provides a novel framework to understand and address the issue within CSR reporting, highlighting the intricate relationship between fraud and greenwashing.

Within sustainable finance, the critique of current sustainability measurement methods for investment funds by Popescu et al. (2021) calls attention to the need for accurate reflection of real-world impacts and the facilitation of a transition to a low-carbon economy. The examination of green finance products within banks by Akomea-Frimpong et al. (2021) identifies critical determinants, such as environmental policies and regulations, that influence the adoption of green finance, emphasizing the banking sector’s role in this regard. The significance of green investments for sustainable economic growth, as explored by Goel (2016), alongside the barriers to green finance adoption identified through the ISM study by Khan et al. (2022), underscores the complexities of integrating sustainability into the financial sector.

Salzmann (2013) provides a comprehensive overview of sustainability issues within financial research, advocating for the deeper integration of CSR into sustainable finance and outlining directions for future research. This call for integration is echoed in the bibliometric analysis conducted by Kashi and Shah (2023), which maps the landscape of sustainable finance research and identifies pivotal gaps and areas for further exploration.

The literature underscores a burgeoning interest in delineating, understanding, and countering greenwashing in sustainable finance yet reveals persistent gaps in the development of universally accepted standards, the role of regulatory frameworks, and the potential of technological advancements to foster transparency and authenticity. Addressing these gaps necessitates robust methodologies for assessing financial products’ sustainability impact and scrutinizing the efficacy of regulatory measures against greenwashing. The call for multidisciplinary approaches and collaborative efforts among academics, policymakers, and practitioners is clear, underlining the collective endeavor required to navigate the complexities of greenwashing and cultivate a more sustainable financial ecosystem.

4 Corporate strategies and practices in greenwashing

Greenwashing tactics and techniques are diverse and often sophisticated, making it challenging for consumers and investors to discern genuine sustainability efforts from deceptive practices. One common tactic is using vague language, such as eco-friendly, green, or natural, without providing concrete evidence or certification to support these claims (Bowen and Aragon-Correa, 2014; Calma, 2023). Another technique is using irrelevant claims or false labels that may sound impressive but have little to do with the product’s environmental impact. For instance, a company might boast about the energy efficiency of its production process while ignoring the ecological harm caused by its products or their disposal (Delmas and Burbano, 2011).

In sustainable finance, greenwashing can involve misrepresenting the environmental benefits of an investment product or using funds raised through green bonds. For example, a company might claim that the proceeds from a green bond are being used to fund renewable energy projects. However, the funds might be used for projects with questionable environmental benefits or general corporate purposes (Karpf and Mandel, 2017).

Real-life examples of greenwashing tactics abound. For instance, fashion brands like H&M, Zara, and Uniqlo were caught greenwashing. These brands contribute to the massive amounts of textile waste caused by the clothing industry. Similarly, BP, a fossil fuel giant, changed its name to Beyond Petroleum and added solar panels to its gas stations despite spending more than 96% of its annual budget on oil and gas. Nestlé, Coca-Cola, and Starbucks have also been accused of greenwashing for misleading claims about the recyclability of their products or the sustainability of their practices. JP Morgan Chase, Citibank, and Bank of America have been criticized financially for promoting green investment opportunities while lending enormous sums to industries that contribute significantly to global warming, such as fossil fuels and deforestation (Robinson, 2023). These examples illustrate companies’ wide range of tactics and techniques to greenwash their products, services, and practices.

In the food and beverage industry, McDonald’s made headlines in 2019 when it launched a campaign to reduce single-use plastics in its stores, focusing on replacing all plastic straws with recyclable paper alternatives. However, it was later revealed that the new paper straws were not recyclable, and their sourcing and manufacturing raised different sustainability questions (Akepa, 2021).

Royal Dutch Shell has faced several court cases in the energy sector due to greenwashing. Despite launching campaigns and interviews describing itself as committed to global net-zero programs, reducing carbon emissions, and helping the world fight global warming, Shell has continued exploring new oil and gas production opportunities. It has only devoted 1% of its spending to renewable energy (Koons, 2022).

In the consumer goods sector, Nestlé announced in 2019 that it had “ambitions” for its packaging to be 100% recyclable or reusable by 2025. However, environmental groups criticized the company for not releasing clear targets, a timeline to accompany its ambitions, or additional efforts to help facilitate consumer recycling. Nestlé, Coca-Cola, and PepsiCo were named the world’s top plastic polluters for the third year (Robinson, 2023).

A recent study by Orazalin et al. (2023) found that companies often employ greenwashing tactics to create positive impressions among stakeholders and protect their legitimacy. The study also revealed that the impact of greenwashing varies across different sectors and periods. Another study by Madden (2022) argued that companies should focus on innovation rather than relying on Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) metrics to lead the transition to net-zero emissions. The study highlighted the complexity of navigating the path to net-zero emissions and the critical role of innovation in this process. Stridsland et al. (2023) also emphasized the importance of transparency in emission disclosure to prevent greenwashing. They argued that companies should use greenhouse gas inventories for accounting and decision support to enhance the green transition. These examples illustrate how greenwashing can manifest in different sectors, highlighting the need for consumers and investors to be vigilant and critical of companies’ environmental claims.

Greenwashing can have significant implications for a company’s reputation and financial performance. On the one hand, greenwashing can enhance a company’s reputation by creating a positive image of its environmental practices and products. This enhancement can attract environmentally conscious consumers and investors, increasing sales and investment (Bénabou and Tirole, 2010). However, when the truth about a company’s greenwashing practices is revealed, it can severely damage its reputation (Ibbetson, 2020). Consumers and investors may feel deceived and lose trust in the company, leading to declining sales and investment. This feeling can also result in legal repercussions, as companies can be held accountable for misleading environmental claims.

Moreover, greenwashing can directly impact a company’s financial performance. A study by Goss and Roberts (2011) found that companies with poor CSR practices, which can include greenwashing, pay higher costs for bank loans. These higher costs suggest that banks perceive these companies as riskier, reflecting the potential financial consequences of greenwashing.

In addition to these academic findings, factual examples further illustrate the impact of greenwashing on corporate reputation and financial performance. For instance, the German car manufacturer Volkswagen suffered a significant blow to its reputation and a sharp drop in sales following the revelation of its emissions scandal in 2015. The scandal, which involved the company cheating on emissions tests, led to billions of dollars in fines and lawsuits, demonstrating the severe financial consequences of greenwashing (Ewing, 2015).

Another example is the British multinational oil and gas company BP, which faced a public backlash and legal challenges after it was revealed that the company had misled the public about its environmental practices. Despite its efforts to rebrand itself as a green company, BP’s reputation was severely damaged, and it was forced to pay billions of dollars in fines and compensation for the environmental damage caused by its operations (Dempsey and Raval, 2019).

These examples underscore the potential risks and costs associated with greenwashing, highlighting the importance of genuine commitment to environmental sustainability for corporate reputation and financial performance.

5 The impact of greenwashing on stakeholder perceptions and behavior

Consumers’ perceptions and responses to greenwashing can vary significantly, and these reactions can profoundly affect a company’s reputation and financial performance. According to Bénabou and Tirole (2010), society’s demands for individual and corporate social responsibility are becoming increasingly prominent. However, when companies engage in greenwashing, they can undermine these demands and create a sense of mistrust among consumers. This sentiment can lead to a decline in sales and damage the company’s reputation.

Greenwashing can lead to losing trust among consumers seeking to align their buying decisions with their environmental values. When products are misrepresented as environmentally friendly, consumers may feel deceived and reluctant to buy these products (Bénabou and Tirole, 2010). A study by Walker et al. (2008) found several drivers and barriers to implementing green supply chain management practices. One of the barriers identified was the lack of legitimacy, which can be linked to greenwashing. When companies make false or misleading claims about their environmental practices, they can undermine their legitimacy and credibility in the eyes of consumers.

Moreover, a study by Barnett and Salomon (2012) found that the relationship between corporate social performance (CSP) and corporate financial performance (CFP) is U-shaped. This result suggests that companies with either low or high CSP have higher CFP than companies with moderate CSP. This finding could imply that companies engaging in greenwashing (resulting in a moderate CSP due to the discrepancy between their claims and actual practices) might achieve a different financial performance than companies genuinely committed to environmental sustainability.

In terms of practical examples, the Swedish multinational clothing-retail company H&M launched 2017 a “Conscious” collection, claiming that the clothes were made with sustainable materials. However, the Norwegian Consumer Authority accused H&M of greenwashing, arguing that the company provided insufficient information about the sustainability of the clothes and misled consumers into believing that the clothes were more sustainable than they were. This case led to a public outcry and calls for boycotts of H&M (Bain, 2019).

The examples above highlight the potential consequences of greenwashing for consumer perceptions and responses, underscoring the importance of transparency and honesty in companies’ environmental claims. Unfortunately, the legitimacy of corporate environmental policies often remains unchecked, as companies are not usually mandated by law to validate their environmental statements with third parties, leading stakeholders to question the actual implementation of these policies (Ramus and Montiel, 2005).

Similarly, investors are becoming increasingly aware of and concerned about environmental issues. As a result, they are seeking to align their investment decisions with their ecological principles. However, when companies engage in greenwashing, they can weaken these values and create a sense of distrust among investors. This perception can lead to a deterioration in investment and harm the company’s name (Bénabou and Tirole, 2010).

Greenwashing can result in a loss of confidence among investors looking to support their financial decisions with their environmental values. When financial products are tainted as environmentally friendly, investors may feel betrayed and become unwilling to invest in these products. This sentiment can slow the investment in sustainable projects and hamper the conversion to a low-carbon economy (Bénabou and Tirole, 2010).

A study by Walker and Dyck (2014) found that institutional investors, such as pension funds and mutual funds, are more likely to invest in companies with strong environmental performance. However, when companies engage in greenwashing, they can undermine this preference and deter institutional investors. This aversion can significantly affect a company’s capital access and financial performance.

Moreover, a study by Lourenço et al. (2012) found that investors respond negatively to greenwashing. The study found that companies that engage in greenwashing have lower stock market performance than those that do not. This finding suggests that investors are becoming more discerning and punishing companies engaging in deceptive environmental practices.

Regarding factual examples, the case of Deutsche Bank’s funds arm, DWS, is illustrative. In 2023, DWS was accused of greenwashing by misleading investors about its “green” investments. The company, which manages 928 billion euros ($994 billion) in assets, faced significant backlash from investors and the public, leading to the resignation of its CEO (Reuters, 2022).

Another example is the case of Holland & Knight, a law firm that launched a “greenwashing mitigation” team in 2023. The team is aimed at advising companies accused of failing to live up to their own environmental goals, highlighting the increasing legal risks associated with greenwashing (Bloomberg Law, 2023).

These examples highlight the potential consequences of greenwashing for investor perceptions and responses, underscoring the importance of transparency and honesty in companies’ environmental claims.

6 Policies and regulations

Regulatory bodies play a pivotal role in preventing greenwashing by establishing and enforcing standards for environmental claims, promoting transparency, and holding companies accountable for misleading practices. The first regulatory measure against greenwashing is the establishment of clear and stringent standards for environmental claims. These standards provide a benchmark against which companies’ ecological practices can be assessed, making it more challenging to make false or misleading claims about their environmental performance (Delmas and Burbano, 2011). For instance, the European Union has developed a classification system for sustainable activities, the EU Taxonomy, to prevent greenwashing in the financial sector. The Taxonomy sets performance thresholds for economic activities to qualify as environmentally sustainable, providing a clear framework for companies and investors (EU Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance, 2020).

Regulatory bodies also promote transparency by requiring companies to disclose their environmental practices and impacts. This promotion can involve mandatory reporting of greenhouse gas emissions, water usage, waste generation, and other environmental indicators. Such disclosure requirements make it harder for companies to hide their environmental impacts and can deter them from engaging in greenwashing (Reid and Toffel, 2009). For example, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has issued guidance on disclosing climate change-related risks, encouraging companies to provide detailed and accurate information about their environmental performance (SEC, 2010).

Similarly, regulatory bodies hold companies accountable for greenwashing by imposing penalties for misleading environmental claims. This accountability may include fines, sanctions, and even legal action. Such enforcement actions can deter greenwashing, as they increase the costs and risks associated with deceptive environmental practices (Parguel et al., 2011). However, greenwashing remains a pervasive problem despite these efforts, suggesting that more than current regulatory measures may be required. More research is needed to understand the effectiveness of different regulatory strategies and to identify new approaches to combating greenwashing. For example, in 2021, the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) launched an investigation into misleading green claims in the fashion industry. The CMA examined whether clothing and textile brands were misleading consumers about the environmental impact of their products and whether their claims comply with consumer law (CMA, 2022).

Countries have adopted varying approaches to combat greenwashing, reflecting their unique legal, economic, and cultural contexts. We analyze anti-greenwashing regulations in some countries, including the United States, the European Union, and China.

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is crucial in combating greenwashing through its Green Guides in the United States. These guides, first introduced in 1992 and most recently updated in 2012, provide businesses with guidance on making environmental claims to avoid deceiving consumers. The Green Guides are not legally binding, but the FTC can take enforcement action against companies that engage in deceptive marketing practices, including greenwashing (FTC, 2012). Despite these efforts, some critics argue that the Green Guides must be revised to prevent greenwashing due to their voluntary nature and lack of specific standards (Nyilasy et al., 2014).

In the European Union, the fight against greenwashing is primarily regulated through the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive (UCPD), which prohibits misleading and aggressive commercial practices. The UCPD applies to environmental claims and takes action against greenwashing. In addition, the EU has developed a classification system for sustainable activities, known as the EU Taxonomy, to prevent greenwashing in the financial sector. The Taxonomy sets performance thresholds for economic activities to qualify as environmentally sustainable, providing a clear framework for companies and investors (EU Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance, 2020). However, some critics argue that the UCPD and the EU Taxonomy need to be sufficiently enforced and that more specific standards and stricter enforcement are needed (Ibanez and Grolleau, 2008).

China has also taken steps to combat greenwashing. The Chinese government has implemented various policies and regulations to promote green development and prevent greenwashing. These include the Environmental Protection Law, which requires companies to disclose their environmental information, and the Green Securities Policy, which promotes green investment and requires listed companies to disclose their environmental risks. Despite these efforts, greenwashing remains a significant issue in China, partly due to weak enforcement of regulations and a lack of public awareness (Du, 2015; Yu et al., 2020).

To sum up, while several countries have implemented regulations to combat greenwashing, the effectiveness of these regulations varies. There is a need for more stringent standards, stricter enforcement, and greater public awareness to combat greenwashing effectively.

The effectiveness of current regulations in curbing greenwashing has been debated among scholars. For instance, Lyon and Wren Montgomery (2015) argue that while rules such as the Federal Trade Commission’s Green Guides in the United States and the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive in the European Union provide a framework for companies to make environmental claims, their effectiveness is limited due to their voluntary nature and lack of specific standards. These regulations may encourage companies to engage in greenwashing, as the potential benefits of greenwashing, such as enhanced corporate image and increased sales, outweigh the risks of regulatory penalties.

Similarly, a study by Marquis et al. (2016) found that regulatory enforcement of environmental standards varies significantly across countries, affecting the prevalence of greenwashing. They argue that companies may be more likely to engage in greenwashing in countries with weak regulatory enforcement due to the lower risk of penalties. This view highlights the importance of solid regulatory enforcement in preventing greenwashing.

On the other hand, a study by Dauvergne and Lister (2010) suggests that regulations can effectively curb greenwashing if accompanied by other measures, such as public pressure and market incentives. They argue that rules alone may not deter greenwashing. Still, when combined with public scrutiny and the potential for market rewards for genuine environmental performance, they can create a powerful deterrent against greenwashing.

However, despite these regulations and enforcement actions, greenwashing remains a pervasive problem, suggesting that more than current measures may be required. More research is needed to understand the effectiveness of different regulatory strategies and to identify new approaches to combating greenwashing.

Alternatively, institutions and NGOs are crucial in combating greenwashing. They can contribute to this effort through various means, such as advocacy, education, research, and the development of standards and certifications.

Institutions, particularly those focused on environmental and sustainability issues, can exert influence by researching and developing guidelines and standards for sustainable practices. For instance, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) has developed a series of standards (ISO 14020) that provide environmental labels and declaration guidelines. These standards aim to prevent misleading or unsubstantiated environmental claims, thereby reducing the incidence of greenwashing (ISO, 2020).

On the other hand, NGOs often play a more activist role, raising awareness about greenwashing and advocating for stronger regulations and enforcement. They can also provide valuable resources for consumers and investors to help them make informed decisions. For example, Greenpeace, an international environmental NGO, has been instrumental in exposing cases of greenwashing and pushing for greater transparency and accountability in corporate ecological practices (Greenpeace, 2020). Another example is the Rainforest Action Network (RAN, 2021), which has actively exposed greenwashing in the financial sector. In 2021, RAN (2021) published a report revealing that many major banks continued to finance fossil fuel projects despite their public commitments to sustainability. This advocacy work can help hold companies accountable and deter greenwashing.

In the academic sphere, Lyon and Wren Montgomery (2015) highlight the role of NGOs in monitoring corporate behavior and providing information to the public. They argue that NGOs can counter corporate power by exposing deceptive environmental claims and advocating for stronger regulations. Similarly, Marquis et al. (2016) emphasize the role of institutional investors in combating greenwashing. They argue that institutional investors, such as pension funds and mutual funds, can pressure companies to improve their environmental performance and avoid greenwashing.

Briefly, institutions and NGOs play a vital role in combating greenwashing. Through their research, advocacy, and educational efforts, they can help to promote transparency, accountability, and genuine commitment to sustainability in the corporate sector.

In the same way and by independently verifying a company’s environmental claims, third-party certifications and eco-labels are critical in preventing greenwashing. Independent organizations assessing companies’ environmental performance against predefined criteria award these certifications and labels. Providing a credible and recognizable symbol of ecological performance can help consumers and investors distinguish between genuine and deceptive environmental claims (D’Souza et al., 2007).

One of the critical benefits of third-party certifications and eco-labels is that they can reduce the information asymmetry between companies and consumers or investors. Companies often have more information about their environmental performance than consumers or investors, creating greenwashing opportunities. However, third-party certifications and eco-labels can level the playing field by providing reliable and accessible information about a company’s environmental performance. These certifications can help consumers and investors make informed decisions and deter companies from greenwashing (Dauvergne and Lister, 2010).

However, the effectiveness of third-party certifications and eco-labels in preventing greenwashing can depend on several factors. These include the credibility of the certifying organization, the rigor of the certification process, and the transparency of the certification criteria. If these factors are not adequately addressed, there is a risk that certifications and labels themselves could be used as a form of greenwashing (Ibanez and Grolleau, 2008).

In a study by Parguel et al. (2011), it was found that eco-labels could indeed help in reducing greenwashing. The study highlighted that when used correctly, eco-labels can provide a clear and credible signal of a product’s environmental performance, assisting consumers in making more informed choices and discouraging companies from making misleading environmental claims.

For example, the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC, n.d.) certification is a globally recognized standard for responsible forest management. Companies that achieve FSC certification have met rigorous environmental and social norms, assuring consumers and investors that their products are not contributing to deforestation or exploitation of forest communities. However, it is essential to note that while such certifications can help prevent greenwashing, they are not guaranteed. Critics argue that FSC has had minimal impact on deforestation since there have been instances where FSC-certified companies were involved in illegal logging and greenwashing practices. The FSC’s decision-making structure, lack of expertise in certifying agencies, and competition from industry-run forest-certifying organizations have contributed to these shortcomings (Conniff, 2018).

Another example is the Energy Star label, a widely recognized symbol of energy efficiency. Products that carry the Energy Star label have been independently certified to meet strict standards for energy efficiency set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. This label helps consumers identify energy-efficient products and reduces the likelihood of greenwashing in the energy sector (Energy Star, 2023).

Third-party certifications and eco-labels can significantly prevent greenwashing by independently verifying environmental claims and reducing information asymmetry. However, their effectiveness depends on the certifying organization’s credibility, the certification process’s rigor, and the certification criteria’s transparency.

7 Discussion

At the outset of our exploration into greenwashing within sustainable finance, we sought to unpack several intricately connected research questions, aiming to dissect the phenomenon’s prevalence, its myriad forms, impacts, and potential avenues for remediation. These queries are inherently interwoven with the broader dialog on sustainable finance’s credibility and operational dynamics amidst growing greenwashing concerns.

To elucidate, we embarked on a systematic scoping review, adhering to the PRISMA framework, which enabled us to navigate the literature about greenwashing methodically. This approach was instrumental in uncovering the diverse strategies employed across sectors to portray investment products as environmentally benign. Notably, our findings reveal a spectrum of greenwashing tactics, from the deployment of ambiguous language to outright opacity, which collectively undermine stakeholder trust, tarnish corporate reputations, and dilute the financial performance of entities implicated in such practices.

Our research questions aimed to chart the terrain of greenwashing within sustainable finance, scrutinizing its manifestations across different industry sectors. This goal was realized through an extensive review that spotlighted the severe ramifications of greenwashing, on the implicated corporations’ standing and fiscal health and the broader integrity of the sustainable finance market. The analysis further delved into the roles played by regulatory entities, NGOs, and certification mechanisms in countering greenwashing, albeit acknowledging the mixed efficacy of these interventions.

In addressing the potential measures to mitigate greenwashing, our research illuminated a spectrum of strategies, underscored by a call for stringent regulatory frameworks, bolstered international cooperation, and heightened public consciousness. Significantly, this discourse invites businesses to embrace authentic environmental stewardship, thus navigating away from the pitfalls associated with greenwashing, including legal entanglements and reputational damage.

Lastly, the study delves into how greenwashing influences investor behavior and decision-making, revealing unearthed insights into the detrimental effects of greenwashing on investment patterns and highlighting a pressing need for greater transparency and veracity in environmental claims. Through the lens of comprehensive evidence synthesis, this discussion section seeks to bridge the research questions with their corresponding findings, thus contributing a nuanced understanding of greenwashing’s multifaceted impacts on sustainable finance while paving the way for future scholarly endeavors in this domain.

The findings of this research have significant implications for both theory and practice. From a theoretical perspective, the study contributes to the growing literature on greenwashing in sustainable finance. It provides a comprehensive overview of the prevalent forms of greenwashing, their impact on the credibility and functioning of the sustainable finance market, and potential measures to combat greenwashing. The study also highlights the need for further research on the effectiveness of these measures and the role of different stakeholders in combating greenwashing.

From a practical perspective, the study offers valuable insights for various stakeholders, including government authorities, businesses, non-profit organizations, and investors. For government authorities, the findings underscore the importance of robust regulation and enforcement to prevent greenwashing. This prevention includes the development of clear and stringent standards for environmental claims, promoting transparency through mandatory disclosure requirements, and imposing penalties for misleading practices. The study also highlights the need for international cooperation in regulating sustainable finance to ensure consistency and effectiveness across different jurisdictions.

For businesses, the study emphasizes the risks and costs associated with greenwashing, including damage to corporate reputation, loss of consumer and investor trust, and potential legal repercussions. It suggests businesses adopt genuine and transparent environmental practices to avoid these risks and gain a competitive advantage. As Lyon and Maxwell (2011) noted, companies that engage in greenwashing may experience short-term gains. Still, they will face long-term costs as consumers and investors become more discerning and regulatory scrutiny increases.

The study highlights non-profit organizations and NGOs’ crucial role in combating greenwashing. These organizations can contribute to this effort through advocacy, education, research, and the development of standards and certifications. They can also be vital in monitoring corporate behavior and providing public information, as Dauvergne and Lister (2010) suggested.

The study underscores the importance of vigilance and critical evaluation of companies’ environmental claims for consumers and investors. As Walker and Dyck (2014) noted, consumers and investors are becoming increasingly aware of and concerned about environmental issues. They are seeking to align their financial decisions with their ecological values. However, the prevalence of greenwashing in sustainable finance can undermine these values and create a sense of mistrust. Therefore, consumers and investors must be equipped with the knowledge and tools to discern genuine sustainability efforts from deceptive practices.

In brief, the study provides a comprehensive understanding of greenwashing in sustainable finance, its implications, and potential solutions. It underscores the importance of transparency, accountability, and commitment to environmental sustainability in the corporate sector. It also highlights the need for further research and action to combat greenwashing and promote sustainable finance.

Our study delineated various forms of greenwashing prevalent in sustainable finance, highlighting the disconnect between advertised environmental stewardship and actual corporate practices. These findings beckon a deeper interrogation into the subtleties of greenwashing tactics, urging future research to explore the psychological and sociological dimensions that underpin corporate propensity toward such misleading practices. Moreover, this exploration into the forms and impacts of greenwashing uncovers a broader spectrum of theoretical implications, suggesting that greenwashing not only dilutes the essence of CSR but also signifies a fundamental misalignment between market incentives and environmental ethics.

One critique of our study centers on the scope and depth of the literature review. While extensive, our review may only partially capture the evolving landscape of greenwashing tactics amidst rapidly changing regulatory and technological environments. This limitation suggests a potential oversight of emerging greenwashing practices that are yet to be widely reported or scrutinized within academic circles. Furthermore, our analysis predominantly hinges on secondary data, which, while comprehensive, might not capture the nuanced motivations behind corporate greenwashing practices or the subjective interpretations of stakeholders encountering such practices.

Another limitation pertains to the geographical and sectoral scope of our study. Given the global nature of sustainable finance, our focus on predominantly Western corporations and financial markets may not adequately represent greenwashing practices and their implications in emerging markets or specific industries with unique environmental impacts and regulatory contexts.

Future research venues that can be derived from our study include, but are not limited to, the following:

• Emerging Greenwashing Practices: Subsequent research might investigate greenwashing within digital platforms and social networks, where disseminating corporate sustainability claims and stakeholder engagement presents new challenges and opportunities for greenwashing.

• Cross-Cultural and Sectoral Analysis: Research could extend to non-Western contexts and diverse industries, examining how cultural, regulatory, and market dynamics influence greenwashing practices and stakeholder perceptions.

• Motivational Analysis: Qualitative research examining the motivations of executives and marketers in pursuing greenwashing tactics could provide deeper insights into the phenomenon, potentially uncovering psychological and organizational factors at play.

• Impact of Technological Solutions: Investigating the role of emerging technologies (e.g., blockchain, AI) in detecting and mitigating greenwashing offers a promising avenue for research, addressing both practical and theoretical implications.

The theoretical implications of our findings extend beyond identifying and mitigating greenwashing to encompass broader discussions about the ethics of corporate sustainability practices, the role of transparency in sustainable finance, and the dynamics between corporate behavior, stakeholder perceptions, and regulatory responses.

Firstly, our study contributes to the discourse on CSR by highlighting the tension between genuine CSR initiatives and greenwashing practices. This tension invites a reevaluation of CSR theories to incorporate mechanisms for distinguishing between authentic and superficial environmental efforts (Bazillier and Vauday, 2015).

Secondly, the findings underscore the need for a theoretical framework that integrates stakeholder theory with concepts of legitimacy and trust. By examining how greenwashing erodes stakeholder trust and undermines the legitimacy of corporate environmental claims, future research can develop more nuanced understandings of stakeholder engagement in sustainable finance.

Lastly, our study prompts a theoretical exploration of regulatory effectiveness in combating greenwashing. The varied success of existing measures in different jurisdictions and sectors calls for a comparative analysis grounded in regulatory theory, exploring the conditions under which regulations effectively deter greenwashing and foster genuine sustainability practices.

In other words, while our study informs the pervasive issue of greenwashing in sustainable finance, its limitations pave the way for future research endeavors. By critically examining these limitations and proposing specific avenues for investigation, we can deepen our theoretical and practical understanding of greenwashing and its implications for sustainable finance.

The critical analysis of our results underscores the multifaceted repercussions of greenwashing, extending beyond the immediate corporate sphere to implicate the sustainable finance market at large. The deterioration of stakeholder trust and the erosion of market credibility underscore the need for a theoretical framework that reconciles the pursuit of financial gains with genuine environmental commitment. In this vein, our findings advocate for a paradigm shift in how environmental claims are construed, verified, and integrated within corporate strategies, heralding a new avenue of research examining current regulatory structures’ efficiency and the possibility of novel governance approaches to curb greenwashing.

Furthermore, our investigation into the potential measures to combat greenwashing reveals a significant gap in the current understanding of regulatory and voluntary mechanisms’ efficacy. This gap signals an emergent research domain that critically evaluates the interplay between policy instruments, corporate behavior, and stakeholder activism in fostering a more transparent and accountable sustainable finance ecosystem. It further emphasizes the theoretical void concerning the function of technology and data analysis in improving the identification and prevention of greenwashing tactics.

Our discussion transcends the practical implications of combating greenwashing to probe its theoretical underpinnings and broader societal implications. By situating our findings within the existing corpus of knowledge, we underscore the exigency of addressing greenwashing and chart a course for future scholarly inquiry that bridges theoretical gaps and fosters a more sustainable integration of environmental imperatives within the finance sector. This reflection reinforces the study’s contribution to advancing the discourse on sustainable finance and greenwashing.

8 Conclusion

The phenomenon of greenwashing in sustainable finance is a complex and multi-faceted issue. It manifests in various forms, from vague language and irrelevant claims to false labels and lack of transparency. This study has highlighted the prevalence of greenwashing across different sectors, with real-life examples from companies like Volkswagen, H&M, Zara, Uniqlo, BP, Nestlé, Coca-Cola, Starbucks, JP Morgan Chase, Citibank, and Bank of America.

The impact of greenwashing on corporate reputation and financial performance is significant. While it may initially enhance a company’s reputation, the eventual revelation of deceptive practices can lead to severe damage, loss of trust, decline in sales and investment, and legal repercussions. This disclosure was evident in the cases of Volkswagen and BP, which faced substantial fines and lawsuits due to their greenwashing practices.

Greenwashing also affects stakeholder perceptions and behavior. Consumers and investors, increasingly aware of environmental issues, can feel deceived when companies engage in greenwashing, leading to a loss of trust and reluctance to invest in misrepresented products. This deception was illustrated in the cases of H&M and Deutsche Bank’s funds arm, DWS (Reuters, 2022).

Regulatory bodies, institutions, NGOs, and third-party certifications play crucial roles in preventing greenwashing. However, their effectiveness varies, and greenwashing remains a pervasive problem, suggesting that more than current measures may be required.

This study has some limitations. First, while it provides a comprehensive overview of greenwashing in sustainable finance, it must delve deeper into the mechanisms and processes that enable greenwashing. Second, the study relies heavily on secondary data and factual examples, which may not fully capture the complexity and nuances of greenwashing practices. Third, the study needs to provide a detailed analysis of the effectiveness of different regulatory strategies and measures to combat greenwashing.

Future research could focus on developing a more nuanced understanding of the mechanisms and processes that enable greenwashing. This approach could involve in-depth case studies of specific companies or sectors. Research could also explore the effectiveness of different regulatory strategies and measures in combating greenwashing, including a comparative analysis of regulations in other countries. Additionally, the study could examine the role of consumers and investors in combating greenwashing, including their awareness, perceptions, and responses to greenwashing practices.

Understanding greenwashing in sustainable finance is crucial for promoting genuine environmental sustainability. Greenwashing undermines the credibility of the sustainable finance market and hinders the transition to a low-carbon economy. By shedding light on the prevalence, implications, and potential solutions to greenwashing, this study contributes to the ongoing efforts to ensure that sustainable finance lives up to its promise of driving environmental sustainability.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted without any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsus.2024.1362051/full#supplementary-material

References

Akepa. (2021). Greenwashing: 11 recent stand-out examples. The Sustainable Agency. Available at: https://thesustainableagency.com/blog/greenwashing-examples/ (Accessed July 13, 2023).

Akomea-Frimpong, I., Adeabah, D., Ofosu, D., and Tenakwah, E. (2021). A review of studies on green finance of banks, research gaps and future directions. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 12, 1241–1264. doi: 10.1080/20430795.2020.1870202

Arksey, H., and O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 8, 19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

Bain, M. (2019). Norway wants H&M to explain what’s so sustainable about its “sustainable” clothes. Quartz. Available at: https://qz.com/quartzy/1648911/norway-questions-the-sustainability-of-hms-conscious-collection (Accessed July 13, 2023).

Barnett, M. L., and Salomon, R. M. (2012). Does it pay to be really good? Addressing the shape of the relationship between social and financial performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 33, 1304–1320. doi: 10.1002/smj.1980

Bauer, R., and Hann, D. (2010). Corporate environmental management and credit risk (December 23, 2010). Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1660470 (Accessed July 13, 2023).

Bazillier, R., and Vauday, J. (2015). The greenwashing machine: is CSR more than communication? HAL Open Science. Available at: https://hal.science/hal-00448861v3 (Accessed July 13, 2023)

Bénabou, R., and Tirole, J. (2010). Individual and corporate social responsibility. Economica 77, 1–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0335.2009.00843.x

Bloomberg Law. (2023). Wake up call: Holland & Knight Touts ‘greenwashing’ defense work. Available at: https://news.bloomberglaw.com/business-and-practice/wake-up-call-holland-knight-touts-greenwashing-defense-work (Accessed 7/13/2023).

Bowen, F., and Aragon-Correa, A. (2014). Greenwashing in corporate environmentalism research and practice: the importance of what we say and do. Organ. Environ. 27, 107–112. doi: 10.1177/1086026614537078

Calma, J. (2023). Earth day 2023: Green or greenwashed? The verge. Available at: https://www.theverge.com/23688450/earth-day-2023-green-greenwashed-brands-climate-plastic-pollution (Accessed July 14, 2023).

CMA. (2022). ASOS, boohoo and Asda investigated over fashion ‘green’ claims. Gov.uk. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/asos-boohoo-and-asda-investigated-over-fashion-green-claims (Accessed July 14, 2023).

Conniff, R. (2018). Greenwashed timber: How sustainable Forest certification has failed. Yale environment 360. Available at: https://e360.yale.edu/features/greenwashed-timber-how-sustainable-forest-certification-has-failed (Accessed July 14, 2023).

Cosgrove, B., Newman, R., Grosjean, G., Dahl, H., Sharma, A., Singh, S., et al. (2023). “Sustainable finance for the transformation of food systems” in Transforming food systems under climate change through innovation. eds. B. Campbell, P. Thornton, A. M. Loboguerrero, D. Dinesh, and A. Nowak (Cambridge University Press), 130–143.