94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain., 22 January 2024

Sec. Sustainable Chemical Process Design

Volume 5 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frsus.2024.1287543

This article is part of the Research TopicCurrent and Emerging Trends in CO2 Utilization Towards the Global Challenge of SustainabilityView all 5 articles

This study extends our exploration of the potential of biomass ashes for their CO2-reactivity and self-cementing properties. The ability of three hardwood-based biomass ashes to mineralise CO2 gas and partially replace CEM I in mortars was investigated. The three hardwoods were English oak (Quercus rober), English lime (Tilia x europaea), and beech (Fagus sylvatica). The woody biomass wastes were incinerated at 800°C to extract their key mineral phases, which are known to be reactive to CO2 gas to form carbonates. The selected biomass ashes were analysed for their CO2-reactivity, which was in the range of 32–43% (w/w). The ashes were used to replace CEM I at 7 and 15% w/w and this “binder” was mixed with sand and water to produce cylindrical monolithic samples. These monoliths were then carbonated and sealed cured over 28 days. The compressive strength, density and microstructure of the carbonate-hardened monoliths were examined. The ash-containing monoliths displayed mature strengths comparable to the cement-only reference samples. The CO2 uptake of oak containing monoliths was 7.37 and 8.29% w/w, for 7 and 15% ash substitutions, respectively. For beech and English lime they were 4.96 and 6.22% w/w and 6.43 and 7.15% w/w, respectively. The 28 day unconfined compressive strengths for the oak and beech ashes were within the range of ~80–94% of the control, whereas lime ash was 107% of the latter. A microstructural examination showed carbonate cemented sand grains together highlighting that biomass ash-derived minerals can be very CO2 reactive and have potential to be used as a binder to produce carbonated construction materials. The use of biomass to energy ash-derived minerals as a cement replacement may have significant potential benefits, including direct and indirect CO2 emission savings in addition to the avoidance of landfilling of these combustion residues.

By 2045, the world’s urban population is expected to grow by 1.5 to 6 Bn people. An additional 1.2 M km2 of new “built environment” will be constructed by 2030 and cities will be responsible for 66% of energy consumption and 70% of greenhouse gas emissions (World Bank, 2023). This staggering pace of development requires sustained additional energy supplies and natural resources, including construction materials.

Globally, the current production of cement is estimated to be ~4.2 Gt/year (Schneider et al., 2011; Ezema, 2019). Portland cement production is energy-intensive and involves transformation of limestone and clay to a clinker at 1450°C. Almost 1 t of carbon dioxide (CO2) is emitted/t of cement produced, with 60% of the emissions arising from the decomposition of limestone, and 30% from the burning of fossil fuels to achieve the temperature required (Richardson and Taylor, 2017; Maries et al., 2020; Maschowski et al., 2020). The remaining 10% arise from the workings of the cement plant (WBCSD, 2009).

The global “shift” from fossil fuels to renewables involves increasing biomass to energy use. Sustainable biomass-derived energy contributed ~70% of the total renewable supply in 2017, with 90% of this coming from solid biomass sources (WBA, 2019). In 2020, 685 TWh of electricity was generated globally from biomass sources (WBA, 2022). Currently, bioenergy contributes 55% of renewable energy, equating to >6% of world total energy supply (IEA, 2023). Further projections indicate that around 60% of the total global bioenergy demand in 2050 will be met by solid bioenergy, 30% from liquid biofuels (including energy use for their production), and 10% from biogases (IEA, 2021).

The forest sector is the most significant contributor to the world’s bioenergy supply (Thiffault et al., 2023). Approximately 4.6 Gt is harvested annually with 60% contributing to energy production, 20% to the round wood industry and the remaining being lost during processing (Tripathi et al., 2019). According to FAO (2018), for every cubic metre of log harvested, a cubic metre of woody waste remains in the forest. Forest (primarily wood-derived) products, including charcoal, fuelwood, pellets and wood chips contribute to >85 percent of the total biomass used for energy purposes (Thiffault et al., 2023).

Wood fuels, sourced from tropical hardwood, temperate hardwood, and softwood contribute dominantly to wood fuel ashes (~68% of global forestry ash total) (Zhai et al., 2021). Despite overachieving its 20% target in 2020 with a 22% share of gross final energy consumption from renewable sources, the EU’s recent Renewable Energy Directive 2018/2001/EU outlined a new target of at least 32% for 2030, with a clause of possible upwards revision by 2023 (Eurostat, 2022, 2023). Recently, about 80% of Europe’s renewable heating has been contributed by biomass, mainly by solid biomass, burning (EEA, 2023). However, in developing countries, biomass is dominantly used for non-commercial uses, including as household fuel for both cooking and heating (World Energy Outlook, 2010; Benti et al., 2021). Vassilev et al. (2013) assumed that approximately 7 Gt/yr. of biomass were available for combustion worldwide for energy production. Zhai et al. (2021) estimated that approx. 3 Gt/yr. are currently being utilised.

The use of biomass for energy production is a transition option to “more” sustainable renewable energy. However, biomass burning contributes to CO2 emissions in the longer term (Brack et al., 2021). The CO2 emissions associated with biomass burning (including crop residues) contribute about 18% of global emissions (FAO, 2002; Jain et al., 2014; Tripathi et al., 2020). In respect to the UK, gaseous emissions from biomass to energy have increased by about 11 Mt of CO2 equivalent over the 8 years from 2010 to 2017 (Ricardo Energy and Environment, 2019). The burning of biomass also results in the generation of significant amount of fly and bottom ashes (Tarelho et al., 2015; Cruz et al., 2019). Both fly and bottom ashes are categorised as waste in the European list of wastes and their handling should follow permitted waste management/disposal routes (EC (European Commission), 2000). The estimated worldwide production of biomass ash is 500 Mt/y, of which about 70% is landfilled (Ban et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2017). Vassilev et al. (2013) and Odzijewicz et al. (2022) reported the biomass ash generation from combustion to be 476 Mt/y. However, the global production of biomass ash is ~170 Mt/y and may exceed 1,000 Mt/y in future decades providing all available biomass resources are exploited (Zhai et al., 2021). The emissions from burning woody biomass to energy plants are 1.2 Gt CO2e/y (~2.3% of global emissions) (Bailis et al., 2015). This is further projected to be 2 Gt CO2e by 2050 (Booth, 2018).

The nature of biomass ash depends on the feedstock, the temperature of the burn and the flue gas the treatment system employed (Cruz et al., 2019; Horák et al., 2019). The burn temperature influences ash morphology and chemistry. In general, the original internal and external structure of the biomass, including fibres can be retained at about 600°C (Yao et al., 2017). However, the tendency of an ash to fuse increases at temperatures of 800–1,200°C, leading to loss of volatile elements that may condensate “downstream” in the process and be adsorbed onto ash particles (Li et al., 2012). The elemental composition of biomass ashes varies with ash type, with finer grained fly ashes tending to contain higher amount of nutrients such as Ca, K, Mg, and P and the volatilised elements K and Pb (Barbosa et al., 2013). Bottom ashes concentrate non-volatile elements such as Ba and Si (Kilpimaa et al., 2013). Different biomasses have different mineral compositions and thus carry a “signature” (Zhai et al., 2021a). For example, ashes from eudicots (hardwoods and woody energy crops) are largely dominated by calcium and potassium oxides (CaO and K2O) with modest amounts of silica (SiO2) and low levels of organic contaminants and trace elements and heavy metals. However, temperate hard and soft wood bark ash contain much higher CaO than their parent wood ashes (Zhai et al., 2021).

The EU supports the valorisation of biomass ash to meet its “end-of-waste” strategy towards a circular economy (EC (European Commission), 2011). The utilization of woody biomass ash as a partial cement replacement is being progressively investigated over the years (Cheah and Ramli, 2011; Berra et al., 2015). Biomass ashes from forestry and agriculture contain functional elements such as calcium, silica, alumina, and iron, and have potential to be used as a replacement for clay, shale and limestone (Buruberri et al., 2015; Modolo et al., 2017). They can act as a pozzolana (Snellings et al., 2012) or secondary cementitious material (SCM), in combination with ordinary Portland Cement (CEM I) (Tosti et al., 2021). Albeit the large proportion of the total biomass ash produced is landfilled (Carević et al., 2021), example uses of biomass and its ashes in construction are given in Table 1.

The demand for “carbon efficient” management to minimise CO2 emissions and utilise wastes is increasing and both solid and gaseous waste resources are being explored (Tripathi et al., 2019, 2020). Worldwide, CO2 is being increasingly used as feedstock for manufactured products, such as urea, fuel and polycarbonate. The transformation of CO2 into mineralised products, such as carbonate-based construction aggregates based on thermal process residues is commercially available.1 Under the right conditions, minerals found in biomass ash, for example, calcia (CaO) and magnesia (MgO) can combine with CO2 gas to produce carbonate salts which permanently “lock-up” the CO2 imbibed (Tripathi et al., 2019; Hills et al., 2020). This transformation is thermodynamically driven (Bertos et al., 2004; Flannery, 2015; www.carbicrete.com). However, the handling of biomass waste ashes and their subsequent mineralisation is critical to the efficient production of valorised products, which are “fit for purpose”.

The present work explores the potential for sequestering CO2 in ashes arising from 3 selected hard wood species and their suitability for use as a partial replacement of a hydraulic cement, that is inherently CO2-reactive. As cement production generates significant CO2 emissions, alternative materials that can act as a cement replacement are attractive, especially if there is potential to meet the requirements of “end of waste”. Further, this work also quantifies the global potential for CO2 mineralisation of biomass ash for CO2 savings and emission avoidance. The available biomass ash data used for this calculation is taken from Zhai et al. (2021).

Two materials were prepared for examination. The first was a mortar made with CEM I and <2 mm sand, which acted as our reference material. The second was another mortar containing CEM I, sand and three biomass ashes, where ashes partially replaced CEM I at 7 and 15% w/w (total weight).

Three types of industrial wood-derived biomass residues sourced in the UK were investigated: English oak (Quercus rober), beech (Fagus sylvatica) and English lime (Tilia × europaea) (oak and lime hereafter, respectively). These woody residues were combusted in a Muffle furnace at 800 ± 25°C with a residence time of 4 h to obtain carbon free ashes. These resulting ashes were a concentrated reactive mineral suite particular to each biomass.

The biomass ashes were characterised for selected physical properties (e.g., surface area and ash content) and their chemical (total carbon, elemental oxides and mineral phase) properties. The biomass ashes and their mortar mixtures were examined for their simple physico-chemical properties, elemental and phase-chemistry, compressive strength development and density. The surface area of ashes was determined (Micromeritics Gemini V2.00), and total carbon was analysed by CHN analysis (FLASH EA 1112 Series). The bulk elemental composition was determined by X-ray fluorescence spectrometry (Bruker S2 Puma). The crystalline and amorphous phases in both CEM I and biomass ashes were determined by using X-ray diffraction (Bruker D8 Advance using Cu Kα radiation generated at 40 kV voltage and 40 mA current, between 2° and 80° 2θ). The interpretation of diffractograms was aided by DIFFRACplus EVA software (Bruker AXS), an internal corundum standard and Rietveld refinement using TOPAS V4.1 (Bruker AXS).

Both CEM I and biomass ashes were tested for their reactivity to pure CO2 at 15% moisture (w/w) and a pressure of ~2 bar. The ashes were exposed to CO2 for four-separate cycles in a closed pressurised carbonation chamber, with the first three cycles extending to one hour each, and the fourth cycle being 24 h. The uptake of CO2 in ashes was determined on weight gain (% w/w) basis, following Hills et al. (2020). The theoretical CO2 uptake was also calculated using stoichiometry following Steinour equation (Huntzinger et al., 2009; Nam et al., 2012). The theoretical uptake was compared with the measured CO2 uptake in this study.

The mix design consisted of CEM I (CEMEX, United Kingdom), 2 mm sand (S Walsh and Sons) and biomass ash (as a cement replacement at 7 and 15% w/w), and a control with CEM I and 2 mm sand only (Table 2). The cylindrical monoliths (20 mm in height and diameter) were fabricated by hand tamping the mixtures in 3 layers. Monolithic specimens of this size are not covered by civil engineering standards but are appropriate for research purposes. Hand tamping produces relatively low-density products that were pervious to CO2 gas. The monoliths were divided into two halves, with one being allowed to mature for 28 days in sealed plastic bags, whereas the other was carbonated in 100% CO2 at 2 bar pressure for 24 h prior to curing. The wood ash containing monolithic samples are given the acronym O-7, B-7, and L-7 for the 7% and O-15, B-15, and L-15 for the 15% CEM I substitutions.

The monoliths were tested in triplicate for their unconfined compressive strengths after 1, 7, and 28 days after being formed (ELE International, 65KN compression testing apparatus). The monoliths were tested for their mechanical properties (including density and unconfined compressive strength) and CO2-reactivity. Dry density of oven dried monolith was determined using mass/volume relationship, with the volume calculated for each individual monolith using the diameter and length relationship measured using digital callipers. For each ash, 36 monoliths were broken plus 18 for the control (includes both carbonated and non-carbonated monoliths), making 126 monoliths in total.

The indicative CO2 uptake in monoliths was calculated from the calcite content in carbonated monoliths at 28 days using an atomic mass balance approach. It should be recognised that some of the carbonate detected in “uncarbonated” monoliths might have arisen from atmospheric carbonation during materials handling and preparation. The CO2 uptake in carbonated monoliths includes both atmospheric and added CO2.

The biomass ashes and both uncarbonated and carbonated biomass ash-containing monolithic products were investigated by XRD and electron microscopy (Zeiss, Sigma 300VP, with Oxford Instruments X-maxN Energy Dispersive System, with an accelerating voltage of 10 kV and working distance between 8 to 10 mm). The capture of back-scattered electron micrographs and EDAX analysis was performed on polished resin-impregnated blocks.

The physical and chemical characteristics of the biomass ashes are given in Table 3. The ash content was highest in lime ash, being 3.80%, followed by beech (1.26%) and oak (0.83%) (w/w total weight) ashes. The beech ash presented the highest surface area at 4.53 m2/g followed by the lime and oak ashes at 3.28 and 3.8 m2/g, respectively. The total carbon content of oak ash was highest at 8.21 g/kg, followed by lime and beech ashes, at 5.47 and 2.80 g/kg, respectively. The composition of ashes as oxide equivalents is given in Table 4 and shows the calcium oxide (CaO) content was highest in oak (77% w/w), followed by lime (58%) and beech (45%). Calcium oxide is the key mineral indicator of the CO2 reactivity in ashes and its presence is critical for carbonation to proceed. Lime ash contained the highest silica content at 37% w/w followed by beech (8%) and oak ash (3%).

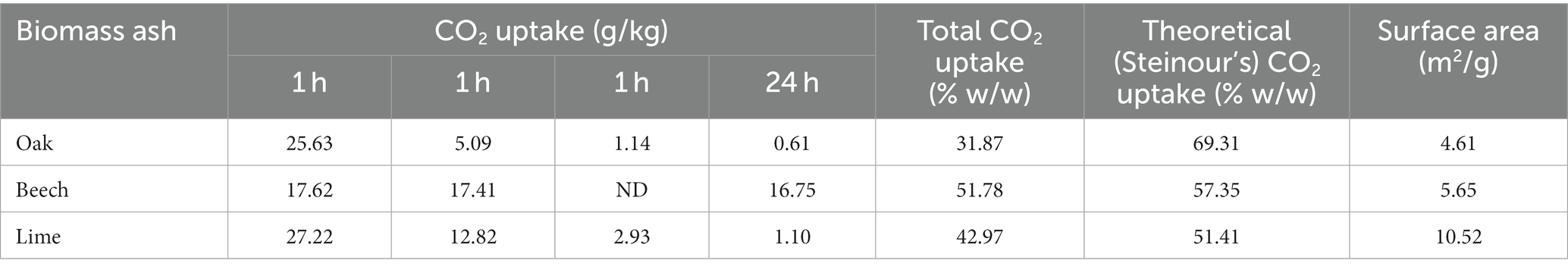

After each successive cycle of exposure to carbon dioxide gas, a gradual individual decrease in the amount of CO2 uptake was observed, as mineral phases progressively carbonated. For oak ash, the first hour CO2 uptake was 25.63 g/kg, which declined to 0.61 g/kg after the fourth cycle of carbonation. In contrast, beech as reacted with approximately the same amount of CO2 over all four consecutive cycles, ranging between 16.75 and 17.62 g/kg. The cumulative CO2 uptake in ashes after 24 h is given in Table 5. The key major mineral phases of uncarbonated and carbonated biomass ashes are given in Tables 6, 7.

Table 5. CO2 uptake in wood biomass ashes and their surface areas after 4 carbonation cycles (moisture added 15% w/w, total weight).

The mechanical properties of monoliths, including density and compressive strength, are shown in Table 8. Although our primary interest is in comparing carbonated monoliths to elucidate the influence of ashes on compressive strength development, the data for the uncarbonated monoliths is available in the Appendix 1. The results show an increase in compressive strength development over time, both during and after carbonation, with the latter indicating that some residual hydraulic activity in CEM I may have been present. The control sand-cement mix achieved a compressive strength of 740 KPa at 28 days. Compared to control, the compressive strengths of all ash-containing composites were slightly lower at 1, 7, and 28 days of age, except for the L-15 composite which was approximately 9% higher than the control.

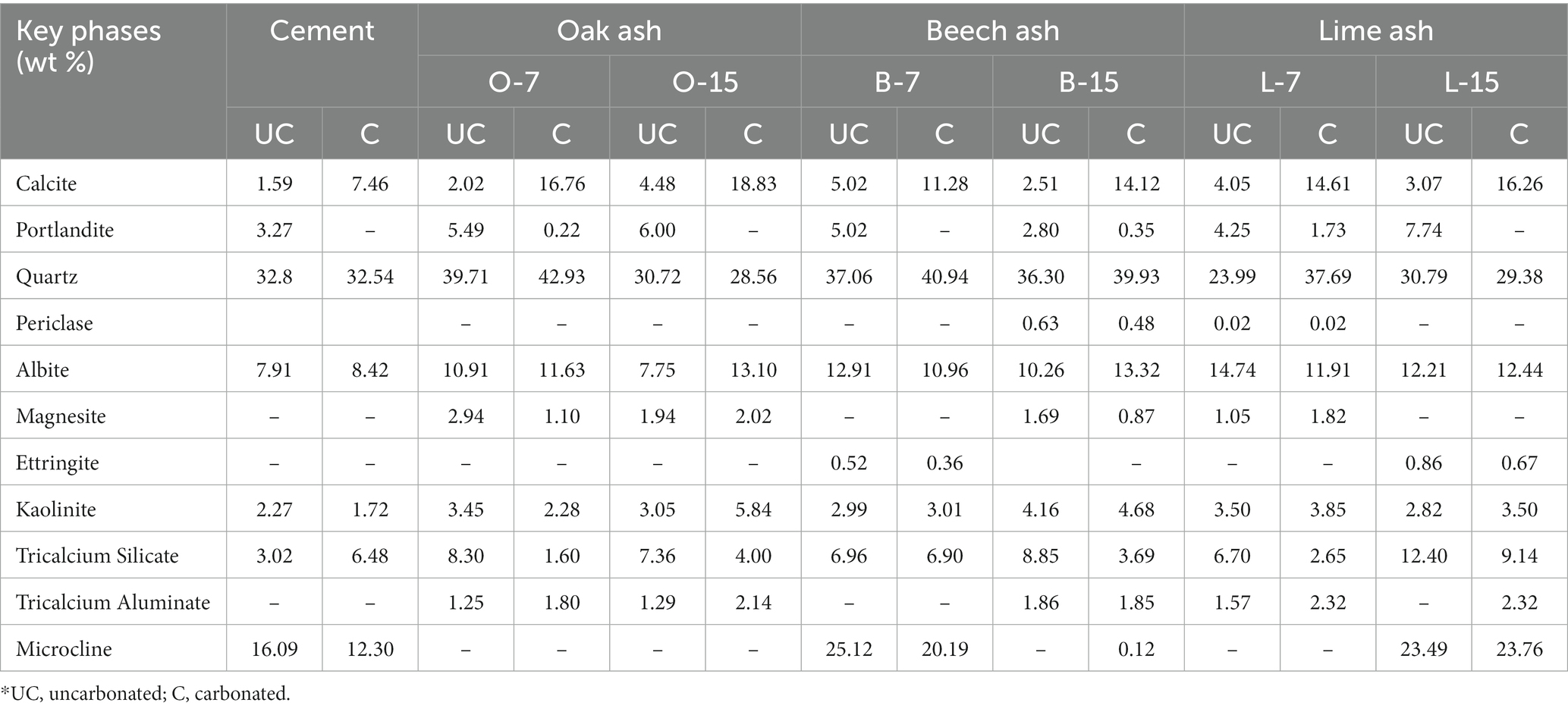

The key major mineral phases of uncarbonated and carbonated biomass ash containing monoliths matured after 7 days of curing are given in Table 9. Calcite was the only crystalline carbonate-containing phase detected in carbonated monoliths. The calcite content of O-7, B-7, and L-7, and O-15, B-15, and L-15 was 16.76 and 18.83, 11.28, and 14.12, and 14.61 and 16.26% w/w, respectively. The results for 28 days old samples are not presented. The effects of atmospheric carbonation upon these porous materials after 7 days of age was significant despite being sealed cured in snap-shut plastic bags, with the effect of reducing the discrepancies observed earlier between carbonated and uncarbonated specimens.

Table 9. Example major phases in carbonated biomass ash-containing monoliths after 7 days (% w/w, total weight) as determined by X-ray diffractometry.

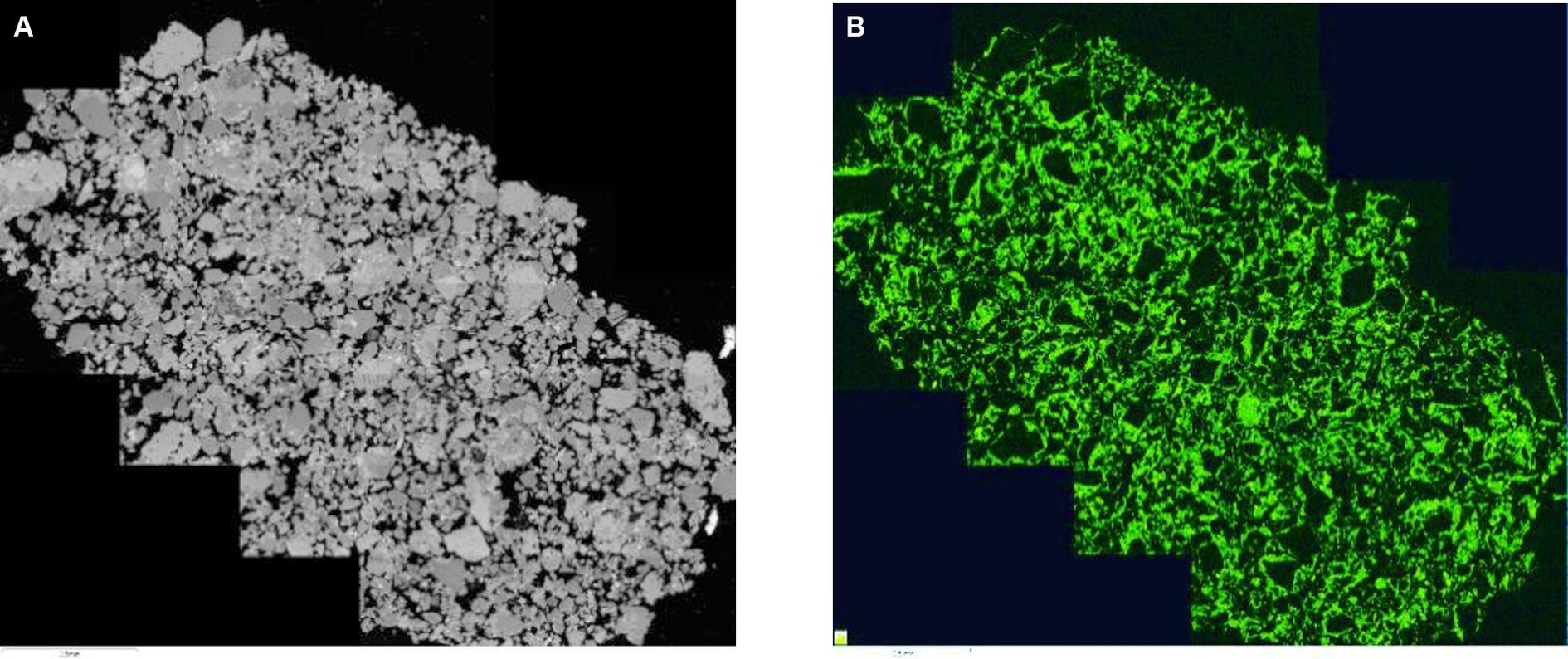

The backscattered composite electron-micrograph of carbonated oak ash is given in Figure 1. Figure 1A shows angular polymineralic sand grains (grey tones) and porosity (black). The composite is very porous and the matrix containing carbonate-able CEM I and oak ash is found primarily coating the individual sand-sized aggregate grains. Figure 1B is an element map of the same sample showing the distribution of Ca (green). The image clearly shows where the carbonate-able cement is located as it forms a lace-like distribution pattern around the surfaces of the sand-sized aggregate particles.

Figure 1. (A) Composite backscattered electron micrography of the oak ash containing monolith with (B) the element map showing the distribution of Ca.

The potential of ashes to mineralise CO2 was calculated theoretically, using the Steinour equation (Huntzinger et al., 2009; Nam et al., 2012) which uses the stoichiometry of a mineral “system” to predict the maximum possible carbon (% w/w) “uptake”. The approach assumes that all the mineral oxides in our ashes are available for carbonation (Kashef and Ghoshal, 2013). However, it should be noted that this equation and modifications thereof are not appropriate to all potentially carbonate-able wastes and the predictions are normally greater than can be achieved under laboratory conditions.

The Steinour equation considers that the (hydr-)oxides of Ca, Mg, Na, and K undergo carbonation, while the corresponding carbonates as well as sulphur and chlorine compounds (expressed as CaCO3, SO3, and KCl) lower the CO2 uptake (Hutzinger et al., 2009; Schnabel et al., 2021). Vassilev and Vassileva (2020) studied the theoretical CO2 uptake of 141 biomass ashes and reported the mean value to be 33.99% (340 kg CO2/t of biomass ash). However, our calculations for given biomass ashes indicate a much higher theoretical uptake, following Nam et al. (2012). Our calculated theoretical CO2-uptakes were 69.31, 57.35, and 51.41% (w/w) for the oak, beech and lime ashes, respectively. However, the experimentally derived CO2 uptake upon 24 h of CO2 exposure was 32, 52, and 43% (w/w), respectively (Table 4). Schnabel et al. (2021) also reported a lower CO2 uptake in biomass bottom and fly ashes than predicted and referred to the theoretical values as overestimations.

The beech ash contains less calcium oxide but higher K2O, MgO, P2O5, and Fe2O3. One of the consequences of this is that the diffractogram for beech ash was very noisy showing “peaks” that were difficult to identify. Further, the presence of CaO appears lower than expected, and may be due to the presence of both amorphous and crystalline forms. Indeed, the amorphous phase content of beech ash is 70.93% w/w, approximately 31–35% higher than the other two ashes. Interestingly, despite the complex mineralogy of this ash, upon carbonation the diffractogram is more resolved and comparable to the other two ashes, supporting our view that amorphous CO2-reactive phases were indeed present. The presence of butschliite (K2Ca(CO3)2) indicates the presence of other carbonate phases and portlandite indicates that the hydroxides were formed, inhibiting carbonation.

The carbonation of mineral systems can be regarded essentially completed in three distinct phases involving 8 steps (Maries, 1985; Nam et al., 2012). In our dry carbonation “system” CO2 gas diffuses and dissolves into a thin film of water (pore fluid) and ionises to H2CO3, leading to a drop in pH. As pH drops due to the neutralisation of pore fluid containing dissolved CaO, CaCO3 is precipitated in pore space present in ash (Tripathi et al., 2020).

According to Vassilev et al. (2021), the formation of secondary carbonates in biomass ashes is due to solid–gas reactions between the CO2 and Ca, Mg, K, and Na oxyhydroxides generated by thermal degradation. However, CO2 uptake potential of biomass ashes depends on the decomposition/combustion temperature of biomass varying between 600–900°C (Vassilev and Vassileva, 2020). During the thermal degradation of biomass between 500 to 900°C, transformation of minerals and their phases present in biomass takes place. This includes combustion of residual char, dehydration and dehydroxylation of biomass minerals, decomposition of carbonates, and initial and partial decomposition of sulphates followed by formation of new active or partially active secondary Ca-, Mg-, K-, and Na-bearing minerals, and phases with potential to react with CO2 gas (Vassilev et al., 2014).

The carbonation of calcia-containing phases can result in more complex carbonate mineral products other than calcium carbonate (CaCO3). By way of example, ankerite (Ca(Mg,Fe)(CO3)2) and fairchildite (K2Ca(CO3)2) may form upon carbonation. In the present study, the CO2 mineralised was confirmed by X-ray diffractometry by the presence of calcite and other carbonate containing phases, such as fairchildite (oak ash) and butschiite (beech ash) (Tables 6, 7). The observed maximum CO2 uptake recorded after exposure of biomass ashes to CO2 was in the order: beech, lime, and oak (Table 5), which was not in accordance with the calcium oxide content, present in the following decreasing order: oak, lime, and beech (Table 4). It is possible that the unintended formation of portlandite in oak and beech ashes (shown in the XRD in Table 7), limited its carbonation on exposure to CO2 gas. It is also possible to achieve higher rates of carbonation during prolonged exposure of portlandite to CO2 gas (Tripathi et al., 2020), but in the present work the carbonation step was limited to 24 h. It is also possible that in these ashes, high amorphous phases consist of carbonates. Vassilev et al. (2021) also reported formation of different carbonate containing phases in biomass ashes.

The mineralisation of CO2 in the biomass ashes was aided by their finely divided nature, their relatively high reaction surface available (Filho et al., 2009; Castel et al., 2016) and their calcium oxide, and other CO2-reactive phases present. However, the reaction could be very slow, if CaO is converted into portlandite (Ca(OH)2) and not “quickly” then to CaCO3, as might happen if too much water in the sample limited the diffusion of CO2. The nature of individual biomass may also have influenced carbonate formation (Tripathi et al., 2020).

The backscattered electron-micrographs taken from polished sections of carbonated monolithic samples given in Figure 1 further confirm the carbonation potential of these mixtures through their uniformly distributed Ca content. The grey-scale backscattered electron micrograph (a) showed the fine aggregate grains coated with the carbonate-able matrix as identified by the distribution of Ca in the element map (b). As carbonation proceeds cementation of the fine aggregate particles within the newly carbonated matrix occurs, augmented by the enhanced (CO2 gas permeable) porosity of the matrix thereby, following the same lace-like distribution pattern.

The compressive strength of all ash-containing carbonated monoliths was higher for all additions at 1, 7, and 28 days of age when compared to their non-carbonated analogues. By way of an example, the 7% ash w/w substitutions gave compressive strength increases in the range 82–672% (Appendix 1). At 28 days of age carbonated monoliths containing O-7, B-7, and L-7 displayed compressive strength increases of 109, 28, and 138%, respectively. For 15% w/w ash, the increase was 210, 97, and 119% at 28 days of age, respectively.

Compressive strength development in ash containing monoliths at early age is ascribed to carbonate cementation (mainly calcite) as described above (Usta et al., 2023). However, in CEM I-only monoliths, strength is not mainly imparted by carbonate formation upon carbonation (calcite formation was lower than for biomass ash containing monoliths), but also by hydration. This indicates that the CEM I was not fully carbonated under the conditions prevailing, and that compressive strength gain was augmented by enhanced hydraulic activity (on exposure to CO2) from the Le Chatelier principle, where the development of CSH is “forced” by a change in pH (Ali et al., 2015).

The results clearly indicate the conversion of calcium oxide and portlandite to calcite after exposure to CO2. Calcite contributes to an increase in early strength development, which in this case increased over 28 days for both 7 and 15% ash containing mixes. We observed a lower compressive strength in the O-15 and B-15 monoliths containing, relative to those containing 7% ash (a 3–7% reduction) over 28 days. However, the compressive strength of the L-15 monoliths was 14.5% higher that the L-7 counterpart. The higher compressive strength of lime ash monoliths could be due to the presence of the higher silica content of this ash (Table 4), which may be reactive/pozzolanic in nature.

The European standard for cement (EN 197-1, 2011) reports the use of blended or Portland composite cements in construction. These cements include coal fly ash, natural volcanic materials, burnt oil shale, blast furnace steel slag, zeolites, ceramic wastes, etc., and are used as substitutes for “common” cement clinker (Canpolat et al., 2004; Taylor et al., 2006; Maschowski et al., 2020; Zeng et al., 2022). Based on their physico-chemical properties, these blended materials impart properties to the cement in different ways (Schneider et al., 2011; Sigvardsen and Ottosen, 2019). However, under right conditions and with proper product design, blended cements can be formulated for different applications (Bentz, 2010).

In the present study, it is observed that both 7 and 15% replacements of CEM I by biomass ashes in monoliths have attained/exceeded the selective mechanical properties compared to the CEM I only control (Appendix 1). Thus, the results obtained indicate that biomass ashes have potential to directly replace CEM I up to 15% w/w. Whilst recognising this is a limited study, further investigation of a broader range of key properties of mortar/concrete such as workability, water absorption and other transport properties is required.

In our earlier work (Tripathi et al., 2019, 2020) we showed that a 10% substitution of biomass ash to CEM I might be beneficial in terms of strength development and the level of substitution on CO2e emissions. In the present work, we show that a 7–15% w/w substitution of the 3 ashes of interest is also beneficial. However, the strengths of oak and beech ash containing monoliths are slightly higher that the CEM I-only controls with a lower replacement of 7% w/w, indicating the optimal dosage rate is yet to be identified.

From the calcite content of monoliths, the CO2 uptake achieved during carbonation was calculated (Table 9). The CO2 uptake was derived using the stoichiometry of this phase, i.e., via the relative atomic weights of CaO and CO2. The CO2 uptake for O, B, and L at 7 and 15% substitution of CEM I was 7.37 and 8.29, 4.96 and 6.22, and 6.43 and 7.15% w/w, respectively. The corresponding unconfined compressive strengths recorded at 28 days were all within the range of ~80–94% of the control, except for L-15, which was 107% of the control.

One tonne of quick lime has the theoretical capacity to react with 799 kg of CO2 to form calcite (comprising 56% CaO and 44% CO2). With other secondary minerals including Ca-, Mg-, K-, and Na-bearing oxides, hydroxides, silicates, phosphates, and inorganic amorphous material, biomass ash can react with additional CO2 gas (Vassilev et al., 2021). Due to carbonate cementation of biomass-contained minerals, replacing reactive calcium oxide (normally present in cement phases) as the fundamental raw material in cement (in a carbonation application) is potentially attractive. Low carbon materials utilising waste are employed elsewhere as geopolymer cements, blended cements, and magnesium cements (Lippiatt et al., 2020).

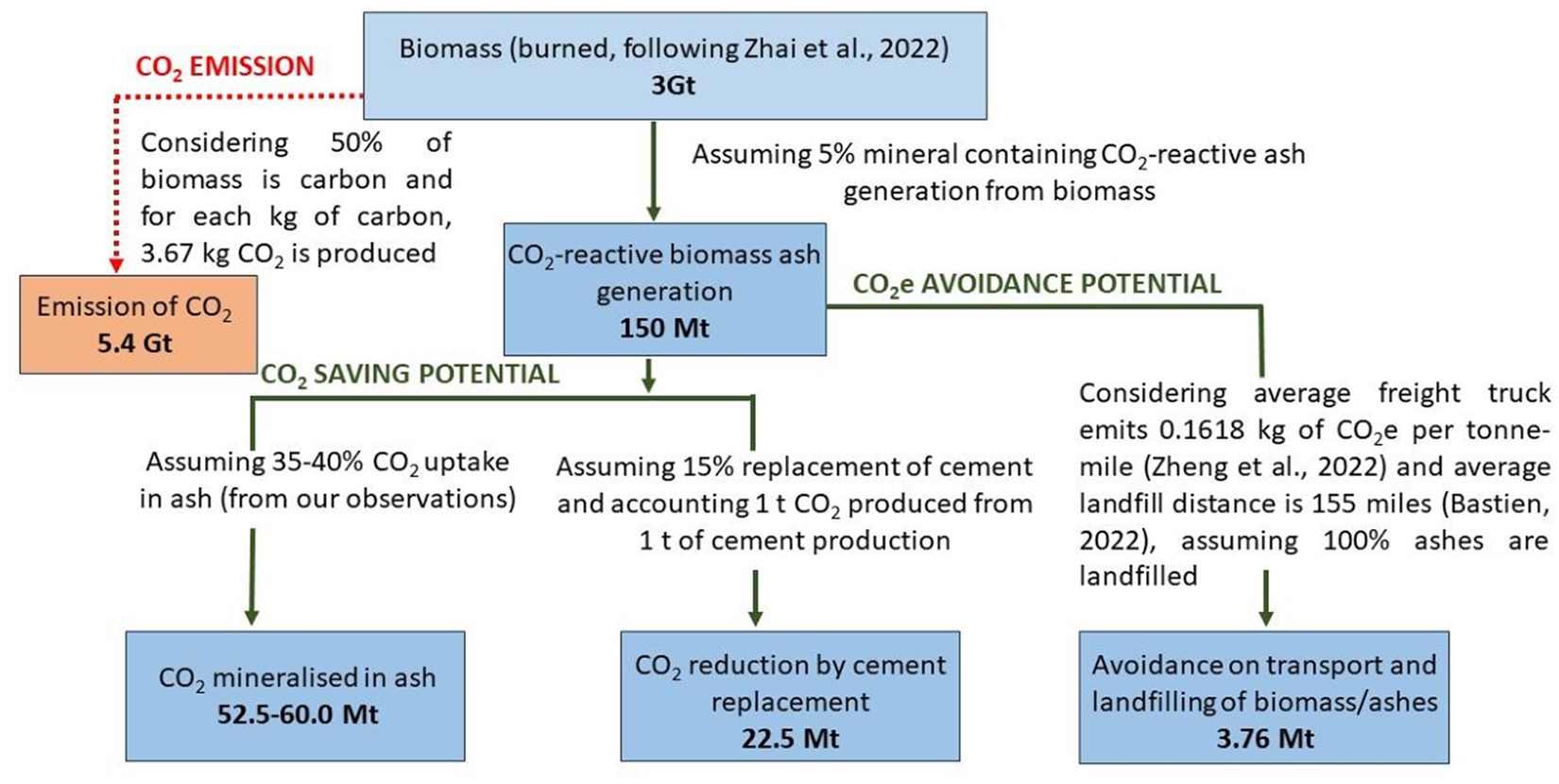

The conceptual diagram shown in Figure 2 summarises our observations on the potential of biomass ashes to act as a cement replacement in a carbonated system. This figure considers the currently available data for biomass ashes from biomass energy plants, following Zhai et al. (2021) and assumptions are made to quantify the CO2 emissions from the burning of biomass. The figure also incorporates CO2 saving potential (assuming 35–40% CO2 uptake in biomass ashes), from our data given in Table 5, following Tripathi et al. (2020) and Hills et al. (2020). This also includes the CO2 avoidance potential based on assumptions made for CO2 emissions associated with transportation and landfilling, follows Zheng et al. (2022). This high-level calculation indicates that 150 Mt of CO2-reactive mineral containing biomass ashes (derived from the 3 Gt of biomass used for energy production, from Zhai et al. (2021)) have potential to:

i. Directly capture/mineralise about 60 Mt of CO2,

ii. Reduce about 23 Mt CO2 by partially replacing cement, and

iii. Helping avoidance of 3.76 CO2e emissions by diverting ash disposal to landfills and associated transport requirements.

Figure 2. Conceptual diagram showing CO2(e) saving and avoidance potential of carbonate mineralised biomass ashes.

Although the amount of CO2 emitted during incineration cannot be compensated by the mineralisation of CO2 in ashes or that saved by their replacement for cement, the CO2 offsets that can be achieved by low-carbon products are significant and much higher than the calculations presented in this paper. This study does not include the total CO2 emissions and environmental implications of biomass burning for energy plants and has only considered landfilling of biomass ashes. Similarly, the implications of developing low-carbon materials to partially replace cement and natural aggregates are significant but have not been taken into account in this paper (see Figure 2).

Ash transport has environmental and economic implications, and we have undertaken the example from Zheng et al. (2022), where an emission of 0.1618 kg of CO2 equivalent (CO2e) per tonne-mile was calculated for freight transport of a (full) 15 tonne load and a 0% loading on the return trip. Bastian (2020) reported that the cost of transporting ash for the bioenergy industry in the UK is around £4 million, depending on the ash properties, with cost of fly ash being significantly higher than bottom ash. Bastian (2020) also reported that in the UK, the cost of ash disposal to a distance of 140–170 miles (including transport, landfilling and landfill tax) in two biomass plants ranged from £140–210 per tonne.

With the significant quantity of ash residue generated from biomass energy production, their ultimate disposal is energy intensive, involving transport to a landfill site, landfill engineering costs, site closure/maintenance and further potential emissions. Landfilling requirements can be minimised if ash can be used for its self-cementing properties, or in a blended system (Tripathi et al., 2020). In the UK and elsewhere, landfill capacity is challenged, costs are rising, and alternative management scenarios are needed for the 21st century (Eyre-Walker, 2018). The valorisation of biomass ash residues contributes to sustainable environmental and economic goals. Hope et al. (2017) performed a cost analysis for biomass to energy ash disposal in Canada and reported the landfill cost to be $77 per tonne. However, this was lower than the cost of ash application to forest sites ($92 per tonne) (Hope et al., 2017).

The key mineral phases extracted from biomass residues react with CO2 gas to produce carbonate minerals. When incorporated in mortar as a CEM I substitute and carbonated they were hardened by carbonate cementation. A CEM I – only reference product was also hardened this way but attained its “full” strength partially from the enhancement of hydration via the le Chetalier principle.

It was observed that the 7–15% w/w cement replacements resulted in an enhanced early strength development relative to the control, but at 28 days of age the ash-containing monolithic product presented similar or lower compressive strength to the control mortar, except for lime ash at 15% w/w. In this respect, the additions used were not optimised for each ash. The use of ash as a CEM I replacement has significant potential to reduce CO2 emissions when in a carbonation application. Further, the utilisation of biomass residues and their ashes in carbonate-able cements has significant positive environmental and economic implications, as biomass ashes arising from energy production tend to be disposed to landfill or are spread on land. These ultimate management options involve considerable transport costs, landfill taxes and significant consequent CO2 emissions.

Our approach to the mineralisation of CO2 in biomass waste-derived ashes has long-term sustainability implications for this voluminous solid waste stream. Biomass to energy plants producing ash and CO2 gas at the same site can utilise this approach to harness environmental benefits by negation of solid and gaseous emissions, through what is in essence a circular economic solution. Our high-level calculations show that the 150 Mt of ash arising from waste biomass contain key CO2-reactive minerals, with potential to “save” 82.5 Mt of CO2 via direct uptake to form carbonate phases and as a cement replacement. In addition, 3.76 Mt CO2 can be avoided by negating the transport associated with landfill disposal.

The authors are continuing their investigation of potential biomass (ashes) in new range of materials that are “fit for purpose” for use in construction, and which have potential to help achieve the sustainable renewable energy goals with net zero targets. The utilisation of mineralised CO2 in the built environment can be considered as permanent solution that protects virgin materials use, preserves landfill space, and reduces the amount of CO2 being emitted to atmosphere.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

NT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. SK: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. AH: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors would like to thank Simon and Lindsay Goddard from Kingston, Kent, UK for the provision of biomass and preparation of ashes.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Ali, M., Abdulla, M. S., and Saad, S. A. (2015). Effect of calcium carbonate replacement on workability and mechanical strength of Portland cement concrete. Adv. Mater. Res. 1115, 137–141. doi: 10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.1115.137

Bailis, R., Drigo, R., Ghilardi, A., and Masera, O. (2015). The carbon footprint of traditional woodfuels. Nat. Clim. Change. 5, 266–272. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2491

Ban, C. C., Nordin, N. S. A., Ken, P. W., Ramli, M., Hoe, K. W., and Ban, C. C. (2014). The high-volume reuse of hybrid biomass ash as a primary binder in cementless mortar block. Am. J. Appl. Sci. 11, 1369–1378. doi: 10.3844/ajassp.2014.1369.1378

Barbosa, R., Dias, D., Lapa, N., Lopes, H., and Mendes, B. (2013). Chemical and ecotoxicological properties of size fractionated biomass ashes. Fuel Process. Technol. 109, 124–132. doi: 10.1016/J.FUPROC.2012.09.048

Bastian, E. J. M. (2020). Towards circular economy: wood ash management for biomass CHP plants in the UK. Maste of Science Thesis, KTH School of Industrial Engineering and Management, Stockholm, Energy Technology: TRITA-ITM-EX 2020: 559. Available at: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1484551/FULLTEXT01.pdf

Beltrán, M. G., Barbudo, A., Agrela, F., Jiménez, J. R., and de Brito, J. (2016). Mechanical performance of bedding mortars made with olive biomass bottom ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 112, 699–707. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.02.065

Benti, N. E., Gurmesa, G. S., Argaw, T., Aneseyee, A. B., and Gunta, S. (2021). The current status, challenges and prospects of using biomass energy in Ethiopia. Biotechnol. Biofuels 14:209. doi: 10.1186/s13068-021-02060-3

Bentz, D. P. (2010). Blending different fineness cements to engineer the properties of cement-based materials. Macro 62, 327–338. doi: 10.1680/macr.2008.62.5.327

Berra, M., Mangialardi, T., and Paolini, A. E. (2015). Reuse of woody biomass fly ash in cement-based materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 76, 286–296. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.11.052

Bertos, M. F., Simons, S. J. R., Hills, C. D., and Carey, P. J. (2004). A review of accelerated carbonation technology in the treatment of cement-based materials and sequestration of CO2. J. Hazard. Mater. B112, 193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2004.04.019

Booth, M. (2018). Not carbon neutral: Assessing the net emissions impact of residues burned for bioenergy. Environmental Research Letters. 13:35001. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/aaac88

Brack, D., Birdsey, R., and Walker, W. (2021). Greenhouse gas emissions from burning US-sourced woody biomass in the EU and UK. Environment and society Programme October 2021, Chatham house report. Available at: https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/2021-10/2021-10-14-woody-biomass-us-eu-uk-summary.pdf

Buruberri, L. H., Seabra, M. P., and Labrincha, J. A. (2015). Preparation of clinker from paper pulp industry wastes. J. Hazard. Mater. 286, 252–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2014.12.053

Cabrera, M., Rosales, J., Ayuso, J., Estaire, J., and Agrela, F. (2018). Feasibility of using olive biomass bottom ash in the sub-bases of roads and rural paths. Constr. Build. Mater. 181, 266–275. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.06.035

Canpolat, F., Yilmaz, K., Köse, M. M., Sümer, M., and Yurdusev, M. A. (2004). Use of zeolite, coal bottom ash and fly ash as replacement materials in cement production. Cem. Concr. Res. 34, 731–735. doi: 10.1016/S0008-8846(03)00063-2

Carević, I., Štirmer, N., Serdar, M., and Ukrainczyk, N. (2021). Effect of wood biomass ash storage on the properties of cement composites. Materials 14:1632. doi: 10.3390/ma14071632

Castel, Y., Amziane, S., and Sonebi, M. (2016). Durabilite du beton de chanvre: resistance aux cycles d’immersion hydrique et sechage, lère Conférence EuroMaghrébine des BioComposites, Marrakech 28–31 March (2016)

Cheah, C. B., and Ramli, M. (2011). The implementation of wood waste ash as a partial cement replacement material in the production of structural grade concrete and mortar: an overview. Resource Conserv Recycl 55, 669–685. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2011.02.002

Chen, R., Cai, G., Dong, X., Pu, S., and Dai, X. (2022). Green utilization of modified biomass by-product rice husk ash: a novel eco-friendly binder for stabilizing waste clay as road material. J. Clean. Prod. 376:134303. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134303

Cruz, N. C., Silva, F. C., Tarelho, L. A. C., and Rodrigues, S. M. (2019). Critical review of key variables affecting potential recycling applications of ash produced at large-scale biomass combustion plants. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 150:104427. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104427

Dawood, E. T., and Ramli, M. (2012). Durability of high strength flowing concrete with hybrid fibres. Constr. Build. Mater. 35, 521–530. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2012.04.085

EC (European Commission) (2000). Commission decision (2000/532/EC) of replacing decision 94/3/EC establishing a list of wastes pursuant to article 1(a) of council directive 75/442/EEC on waste and council decision 94/904/EC establishing a list of hazardous waste pursuant to article 1(4) of council directive 91/689/EEC on hazardous waste. Off. J. Eur. Communities L 226/3

EC (European Commission) (2011). Report from the commission to the European Parliament, the council, the European economic and social committee, and the committee of the regions on the thematic strategy on the prevention and recycling of waste. COM/11/13.19/1/2011, Brussels

EEA (2023), Renewable energy in Europe: Key for climate objectives, but air pollution needs attention. Available at: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/renewable-energy-in-europe-key

EN 197-1 (2011). CEN European Committee for Standardization. 2011. Standard EN 197-1: Cement-part 1: composition, specifications and conformity criteria for common cements

Eurostat (2022). Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/ddn-20220119-1

Eurostat (2023). Available at: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/renewable-energy/renewable-energy-directive-targets-and-rules/renewable-energy-targets_en

Eyre-Walker, G. (2018). Groundsure-the reducing landfill capacity in the UK. Available at: https://www.groundsure.com/resources/the-reducing-landfill-capacity-in-the-uk/

Ezema, I. C. (2019). Chapter 9 – materials, V. W. Y. Tam., K. N. Le (Eds.), Sustainable Construction Technologies. Butterworth-Heinemann, 237–262.

FAO (2002). World agriculture: Towards 2015/2030. Summary report ISBN 92–5–104761-8. Available at: http://www.fao.org/3/a-y3557e.pdf and http://www.fao.org/docrep/004/y3557e/y3557e04.htm#TopOfPage

FAO (2018). Available at: www.fao.org/docrep/006/AD576E/ad576e00.pdf; Accessed on 24th November, 2018

Filho, R. D. T., Silva, F. D. A., Fairbairn, E. M. R., and Filho, J. D. A. M. (2009). Durability of compression molded sisal fiber reinforced mortar laminates. Const. Build. Mat. 23, 2409–2420. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2008.10.012

Flannery, T. A. (2015). Third way to fight climate change. The opinion pages. New York Times. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/24/opinion/a-third-way-to-fight-climate-change.html?_r=0

Gunasekaran, K., Kumar, P. S., and Lakshmipathy, M. (2011). Mechanical and bond properties of coconut shell concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 25, 92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2010.06.053

Hills, C. D., Tripathi, N., Singh, R. S., Carey, P. J., and Lowry, F. (2020). Valorisation of agricultural biomass-ash with CO2. Sci. Rep. 10:13801. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-70504-1

Hope, E. S., McKenney, D. W., Allen, D. J., and Pedlar, J. H. (2017). A cost analysis of bioenergy-generated ash disposal options in Canada. Can. J. For. Res. 47, 1222–1231. doi: 10.1139/cjfr-2016-0524

Horák, J., Kuboňová, L., Dej, M., Laciok, V., Tomšejová, Š., and Hopan, F. (2019). Effects of the type of biomass and ashing temperature on the properties of solid fuel ashes. Pol. J. Chem. Technol. 21, 43–51. doi: 10.2478/pjct-2019-0019

Huntzinger, D. N., Gierke, J. S., Kawatra, S. K., Eisele, T. C., and Sutter, L. L. (2009). Carbon dioxide sequestration in cement kiln dust through mineral carbonation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 1986–1992. doi: 10.1021/es802910z

IEA (2021). What does net-zero emissions by 2050 mean for bioenergy and land use?, Available at: https://www.iea.org/articles/what-does-net-zero-emissions-by-2050-mean-for-bioenergy-and-land-use

IEA (2023). Available at: https://www.iea.org/energy-system/renewables/bioenergy

Jain, N., Pathak, H., and Bhatia, A. (2014). Sustainable management of crop residues in India. Curr. Adv. Agricult. Sci. 6, 1–9.

Kashef, S., and Ghoshal, S. (2013). Physico-chemical processes limiting CO2 uptake in concrete during accelerated carbonation curing. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 52, 5529–5537. doi: 10.1021/ie303275e

Khellou, A., Kriker, A., Hafssi, A., Belbarka, K., and Baali, K. (2016). Effect of the addition of by-product ash of date palms on the mechanical characteristics of gypsum-calcareous materials used in road construction. AIP Conf. Proc. 1758:30005. doi: 10.1063/1.4959401

Kilpimaa, S., Kuokkanen, T., and Lassi, U. (2013). Characterization and utilization potential of wood ash from combustion process and carbon residue from gasification process. Bioresources 8, 1011–1027. doi: 10.15376/biores.8.1.1011-1027

Kunchariyakun, K., Asavapisit, S., and Sinyoung, S. (2018). Influence of partial sand replacement by black rice husk ash and bagasse ash on properties of autoclaved aerated concrete under different temperatures and times. Constr. Build. Mater. 173, 220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.04.043

Li, L., Yu, C., Bai, J., Wang, Q., and Luo, Z. (2012). Heavy metal characterization of circulating fluidized bed derived biomass ash. J. Hazard. Mater. 233–234, 41–47. doi: 10.1016/J.JHAZMAT.2012.06.053

Lippiatt, N., Ling, T., and Pan, S. (2020). Towards carbon-neutral construction materials: carbonation of cement-based materials and the future perspective. J. Building Eng. 28:101062. doi: 10.1016/j.jobe.2019.101062

Liu, Q., Chmely, S. C., and Abdoulmoumine, N. (2017). Biomass treatment strategies for thermochemical conversion. Energy Fuel 31, 3525–3536. doi: 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.7b00258

Mahmoud, H., Belel, Z. A., and Nwakaire, C. (2012). Groundnut shell ash as a partial replacement of cement in sandcrete blocks production

Maries, A. (1985). The activation of Portland cement by carbon dioxide, in proceedings of conference in cement and concrete science, Oxford, UK

Maries, A., Hills, C. D., and Carey, P. (2020). Low-carbon CO2-activated self-pulverizing cement for sustainable concrete construction. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 32:3370. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0003370

Maschio, S., Tonello, G., Piani, L., and Furlani, E. (2011). Fly and bottom ashes from biomass combustion as cement replacing components in mortars production: rheological behaviour of the pastes and materials compression strength. Chemosphere 85, 666–671. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.06.070

Maschowski, C., Kruspan, P., Arif, A. T., Garra, P., and Trouvé, G. (2020). Use of biomass ash from different sources and processes in cement. J. Sustain. Cement Mater. 9, 350–370. doi: 10.1080/21650373.2020.1764877

Merta, I., and Tschegg, E. K. (2013). Fracture energy of natural fibre reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 40, 991–997. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2012.11.060

Modani, P. O., and Vyawahare, M. R. (2013). Utilization of bagasse ash as a partial replacement of fine aggregate in concrete. Procedia Eng. 51, 25–29. doi: 10.1016/j.proeng.2013.01.007

Modolo, R. C. E., Senff, L., Ferreira, V. M., Tarelho, L. A. C., and Moraes, C. A. M. (2017). Fly ash from biomass combustion as replacement raw material and its influence on the mortars durability. J. Mater. Cycle Waste Manag. 20, 1006–1015. doi: 10.1007/s10163-017-0662-9

Nam, S. Y., Seo, J., Thriveni, T., and Ahn, J. W. (2012). Accelerated carbonation of municipal solid waste incineration bottom ash for CO2 sequestration. Geosystem Engineering 15, 305–311. doi: 10.1080/12269328.2012.732319

Odzijewicz, J. I., Wołejko, E., Wydro, U., and Wasil, M. (2022). Utilization of ashes from biomass combustion. Energies 15:9653. doi: 10.3390/en15249653

Olutoge, F., and Abiodun, B. (2013). Characteristics strength and durability of groundnut Shell ash (GSA) blended cement concrete in sulphate environments. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 4, 2122–2134.

Pereira, A., Akasaki, J. L., Melges, J. L. P., Tashima, M. M., and Soriano, L. (2015). Mechanical and durability properties of alkali-activated mortar based on sugarcane bagasse ash and blast furnace slag. Ceram. Int. 41, 13012–13024. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2015.07.001

Ricardo Energy and Environment (2019). Office for National Statistics-UK environmental accounts, Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/environmentalaccounts/articles/aburningissuebiomassisthebiggestsourceofrenewableenergyconsumedintheuk/2019-08-30

Sales, A., and Lima, S. A. (2010). Use of Brazilian sugarcane bagasse ash in concrete as sand replacement. Waste Manag. 30, 1114–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2010.01.026

Sargın, Ş., Saltan, M., Morova, N., Serin, S., and Terzi, S. (2013). Evaluation of rice husk ash as filler in hot mix asphalt concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 48, 390–397. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.06.029

Schnabel, K., Brück, F., and Pohl, S. (2021). Greenhouse gases: Science and technology published by Society of Chemical Industry and John Wiley & Sons LTD. Greenhouse Gas Sci. Technol. 11, 506–519. doi: 10.1002/ghg.2063

Schneider, M., Romer, M., Tschudin, M., and Bolio, H. (2011). Sustainable cement production: present and future. Cement Concrete Res. 41, 642–650. doi: 10.1016/j.cemconres.2011.03.019

Sigvardsen, N. M., and Ottosen, L. M. (2019). Characterisation of coal bio ash from wood pellets and low-alkali coal fly ash and use as partial cement replacement in mortar. Cement Concrete Composites 95, 25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2018.10.005

Snellings, R., Mertens, G., and Elsen, J. (2012). Supplementary cementitious materials. Rev. Mineral Geochem. 74, 211–278. doi: 10.2138/rmg.2012.74.6

Tarelho, L. A. C., Teixeira, E. R., Silva, D. F. R., Modolo, R. C. E., and Labrincha, J. A. (2015). Characteristics of distinct ash flows in a biomass thermal power plant with bubbling fluidised bed combustor. Energy 90, 387–402. doi: 10.1016/J.Energy.2015.07.036

Taylor, M., Tam, C., and Gielen, D. (2006). Energy efficiency and CO2 emissions from the global cement industry. Korea. 50, 61–67.

Thiffault, E., Gianvenuti, A., Zuzhang, X., and Walter, S. (2023). The role of wood residues in the transition to sustainable bioenergy – analysis of good practices and recommendations for the deployment of wood residues for energy. Rome, FAO

Tosti, L., van Zomeren, A., Pels, J. R., and Rob, N. J. (2021). Evaluating biomass ash properties as influenced by feedstock and thermal conversion technology towards cement clinker production with a lower carbon footprint. Waste Biomass Valorisation 12, 4703–4719. doi: 10.1007/s12649-020-01339-0

Tripathi, N., Hills, C., Singh, R. S., and Atkinson, C. J. (2019). Biomass waste utilisation in low-carbon products: harnessing a major potential resource. NPJ climate and atmospheric. Science 2:35. doi: 10.1038/s41612-019-0093-5

Tripathi, N., Hills, C. D., Singh, R. S., and Singh, J. S. (2020). Offsetting anthropogenic carbon emissions from biomass waste and mineralised carbon dioxide. Sci. Rep. 10:958. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-57801-5

Usta, M. C., Yörük, C. R., Uibu, M., Traksmaa, R., Hain, T., and Gregor, A. (2023). Carbonation and leaching behaviors of cement-free monoliths based on high-sulfur fly ashes with the incorporation of amorphous calcium aluminate. ACS Omega 8, 29543–29557. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.3c03286

Vassilev, S. V., Baxter, D., Andersenm, L. K., and Vassileva, C. G. (2013). An overview of the composition and application of biomass ash. Part 1. Phase–mineral and chemical composition and classification. Fuel 105, 40–76. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2012.09.041

Vassilev, S., Baxter, D., and Vassileva, C. (2014). An overview of the behaviour of biomass during combustion: part II. Ash fusion and ash formation mechanisms of biomass types. Fuel 117, 152–183. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2013.09.024

Vassilev, S., and Vassileva, C. (2020). Extra CO2 capture and storage by carbonation of biomass ashes. Energy Convers. Manag. 204:112331. doi: 10.1016/j.enconman.2019.112331

Vassilev, S. V., Vassileva, C. G., and Petrova, N. L. (2021). Mineral carbonation of biomass ashes in relation to their CO2 capture and storage potential ACS. Omega 6, 14598–14611. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.1c01730

WBA (2022). Global bioenergy statistics 2022, Available at: https://www.worldbioenergy.org/uploads/221223%20WBA%20GBS%202022.pdf

World Bank (2023). Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/urbandevelopment/overview

World Energy Outlook (2010). Energy poverty: How to make modern energy access universal? In: World energy outlook 2010 for the UN general assembly on the millennium development goals. Paris, organisation for economic co-operation and Development & International Energy Agency. Available at: www.c8s.co.uk; Accessed 16th August, 2023

Yao, X., Xu, K., Yan, F., and Liang, Y. (2017). The influence of ashing temperature on ash fouling and slagging characteristics during combustion of biomass fuels. BioRes. 12, 1593–1610. doi: 10.15376/biores.12.1.1593-1610

Yaro, S. N. A., Sutanto, D. M. H., Usman, D. A., and Jagaba, A. H. (2022). The influence of waste Rice straw ash as surrogate filler for asphalt concrete mixtures. Construction 2, 118–125. doi: 10.15282/construction.v2i1.7624

Zeng, Q., Li, L., Liu, J., Lu, T., Xu, J., and Al-Mansour, A. (2022) in Microstructure and properties of concrete with ceramic wastes. Handbook of sustainable concrete and industrial waste management (Elsevier), Francesco Colangelo. eds. R. Cioffi and I. Farina, 229–253.

Zhai, J., Burke, I. T., Mayes, W. M., and Stewart, D. I. (2021a). New insights into biomass combustion ash categorisation: a phylogenetic analysis. Fuel 287:119469. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2020.119469

Zhai, J., Burke, I. T., and Stwart, D. I. (2021). Beneficial management of biomass combustion ashes. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 151:111555. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2021.111555

Zheng, Y., Liu, C., Zhu, J., Sang, Y., and Wang, J. (2022). Carbon footprint analysis for biomass-fuelled combined heat and power station: a case study. Agriculture 12:1146. doi: 10.3390/agriculture12081146

Keywords: biomass residue/waste, biomass ash, CO2 mineralisation, construction materials, cement replacement, CO2 emission reduction

Citation: Tripathi N, Hills CD, Singh RS, Kyeremeh S and Hurt A (2024) Mineralisation of CO2 in wood biomass ash for cement substitution in construction products. Front. Sustain. 5:1287543. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2024.1287543

Received: 01 September 2023; Accepted: 05 January 2024;

Published: 22 January 2024.

Edited by:

Ana V. M. Nunes, New University of Lisbon, PortugalReviewed by:

Giorgio Tofani, National Institute of Chemistry, SloveniaCopyright © 2024 Tripathi, Hills, Singh, Kyeremeh and Hurt. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nimisha Tripathi, bi50cmlwYXRoaUBncmUuYWMudWs=; Colin D. Hills, Yy5kLmhpbGxzQGdyZWVud2ljaC5hYy51aw==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.