95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain. , 04 September 2023

Sec. Sustainable Organizations

Volume 4 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frsus.2023.1128620

This article is part of the Research Topic The Role of the Human Dimension in Promoting Education for Sustainable Development at the Regional Level View all 10 articles

Introduction: If sustainability is about imagining and pursuing desired futures, our past history, heritage, and culture will influence the kind of futures we seek and our chosen routes towards them. In Scotland, there is a strong connection between culture, land, and identity; a sense of community; and a perception of work ethic that derive from our biogeography and socio-political journey. Concepts and practises of education have been influenced by the ideas of key thinkers such as the Scot Sir Patrick Geddes, who introduced approaches to education and community through concepts such as “heart, hand, and head”, “think global, act local,” and “place, work, and folk”. This background influenced us in establishing Scotland's United Nations University-recognised Regional Centre of Expertise (RCE) in Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), known locally as “Learning for Sustainability Scotland”. Its initial development ten years ago and subsequent evolution have been built on engaging collaboratively across Scotland and linking formal, non-formal, and informal modes of learning for sustainability. In this paper, we explore how culture and context have influenced the emergence, governance, and activities of RCE Scotland over the past decade.

Methods: We developed an analytical framework of possible cultural and contextual influences on Scottish education. We used a Delphi approach to develop a novel and locally relevant definition of ESD when the RCE was established.

Results: Analysis of purposively selected RCE Scotland activities against our cultural framework illustrated how they had been influenced by culture or context. We propose that democratic intellect, local and global, and nature-culture connections have informed our initiative.

Discussion: We conclude that connection to people, place, and nature influences engagement and action on sustainability, and we suggest that additional sustainability competencies should include physical, emotional, and spiritual aspects of nature connection.

If sustainability is about imagining and pursuing desired futures (White, 2013), our heritage, natural environment and culture will influence the kind of futures we seek and our chosen routes towards these. Scotland is a small nation, inhabited for millennia by people who lived off the land and long connected to other parts of the globe through emigration and immigration. Although people were historically close to the land, socio-cultural relationships with nature have differed (Brennan, 2018), including perspectives between “crofter” or “laird”1 (Hunter, 1979). Education has always been a Scottish strength, helping to drive the Enlightenment and casting Scots and Scottish influence wide around the globe (Davie, 1961). The need for education in relation to sustainable development was eloquently defended by Sterling (2002), who argued for a holistic, ecological, “whole person” approach to learning. This paper investigates a subsequent vision of “learning for sustainability” that is inter-sectoral, interdisciplinary and inter-generational. It incorporates formal, informal and non-formal modes of learning across Public, Private and Third Sectors, throughout a lifespan and in different contexts. This vision was articulated and has been supported through the launch and activities of Scotland's United Nations University recognised Regional Centre of Expertise in Education for Sustainable Development (hereafter “RCE Scotland”), locally named “Learning for Sustainability Scotland.” In this paper, we explain why and how RCE Scotland was launched, and we describe its intentions, ethos, governance, and some activities. We critically analyse how this network organisation has drawn on place, nature and culture to offer a locally contextualised but globally relevant framework for learning for sustainability embedded in the Geddesian educational approach of “heart, hand and head” (Geddes, 1919, 1949; Higgins and Nicol, 2010; Ivanaj et al., 2014), with lessons for other such initiatives.

Sustainable development can be considered a process that facilitates the pursuit of sustainability. This is, at first, an aspiration; a vision of the future and articulation of possibilities (Ferraro et al., 2011; White, 2013; UN, 2015). Secondly, it is a journey, with different routes towards sustainability (UN, 2015). This journey requires maps and goals, technology and innovation, tools and navigation, and travelling together despite our different travel agendas. Sustainable development thus requires a form of knowledge production, exchange and implementation that is both collective and deeply individual (White, 2013). Future possibilities are human desires, influenced by region, values, status and knowledge. However, future possibilities are dependent on us living within our planetary boundaries (Rockström et al., 2009), understanding the values of ecosystem services whilst reconnecting with nature (Barragan-Jason et al., 2022).

Imagining visions of the future is a positive and empowering process, but it is now essential to enable a transition to sustainability and tackle multiple and interlinked contemporary crises (Davies et al., 2012; UN, 2015). Climate change, biodiversity loss, pollution and the interlinked globalisation and neoliberalism have caused great environmental damage and exacerbated social inequalities (Rockström et al., 2009). These global challenges manifest in local places, and their solutions will require international collaboration and charismatic leadership, but also grass-roots, locally contextualised responses (Meyerricks and White, 2021). Actors across all sectors and in all places—politicians and policymakers, practitioners and professionals, local communities, and indigenous peoples—will need to engage in ongoing dialogical processes and co-production to enable sustainability transitions (Chambers et al., 2022). Integrating different perspectives and experiences is not easy. It requires respect for ontological plurality and the epistemological spectrum, transdisciplinarity, and collaboration. We also need different skill sets and excellent facilitation to navigate and negotiate our goals and strategies (Brand and Karvonen, 2007). In this, academia will play only a part. Whilst the sciences, the social sciences and the humanities have much to offer, practitioner, local, indigenous, and traditional knowledges will all be required to co-design visions of and solutions for the future (White, 2013; Vaughter et al., 2022; Mardero et al., 2023). Linking theory to practise is essential, and holistic outlooks are required to address the systemic aspects of these crises (Voulvoulis et al., 2022).

Education is an essential aspect of this imagining—creating visions of the future—and enacting—journeying towards these futures. Learning is required to raise awareness and develop understanding of the challenges we face, to develop specific knowledge of our society and natural environment, to appreciate nature and culture and to innovate solutions for a sustainable future for the planet. Education can promote citizenship, train people for particular roles, enable individuals to develop to their potential, and encourage transformative learning for the change to a better society and fairer world (Sterling, 2002). Education can even be a power to enable freedom and self-discovery, and revolutionary educational approaches that move beyond “banking” of information can enable recognition of alternative paradigms (Freire, 1970). Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) is now seen to underpin our efforts towards a sustainable world. Definitions of ESD are often contested, however, the UNESCO approach is relevant here: “Education for Sustainable Development is a lifelong learning process and an integral part of quality education. It enhances the cognitive, social and emotional and behavioural dimensions of learning. It is holistic and transformational, and encompasses learning content and outcomes, pedagogy and the learning environment itself .” (UNESCO, 2021). Education for Sustainable Development requires innovative pedagogies, real-world examples, interdisciplinary approaches and an exciting, inspiring mode of learning that is relevant to all disciplines (Price et al., 2021; QAA/Advance HE, 2021). Such education is not merely the absorption of information but is also the acquisition of skills and capacities to equip learners to tackle the uncertain and complex world (Sterling, 2010). A competence can be seen as “a functionally linked complex of knowledge, skills, and attitudes that enable successful task performance and problem solving” (Wiek et al., 2011), but it can also include the capacity to value and understand. Hence, “a competence is defined as the ability to successfully meet complex demands in a particular context” through the mobilisation of psychosocial prerequisites (including cognitive and non-cognitive aspects; Rychen, 2009). Sustainability competencies include future, critical and systems thinking, and inter-personal, intra-personal, interdisciplinary, strategic, and normative/cultural competencies (UNECE, 2012; Giangrande et al., 2019).

It has always been recognised that we needed to strengthen education to enable sustainable development, but this recognition was strongly formalised when in 2002, from the World Summit in South Africa and the Johannesburg Plan of Implementation, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution for the Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (UNESCO, 2014). This decade, led by UNESCO, sought to strengthen the principles, values and practises of sustainable development in educational contexts around the world. In response, in 2003 the United Nations University Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability (UNU-IAS), with funding support from the Ministry of the Environment, Japan, launched a multi-stakeholder global network of Regional Centres of Expertise on ESD (RCEs), along with other initiatives (United Nations University, 2012). RCEs originally were designed to provide “an institutional mechanism to facilitate shared learning for sustainable development” (Fadeeva et al., 2014, p. 22). Delivering a scaled and multi-sectoral response, they “aspire to translate global objectives into the context of the local communities in which they operate. Upon the completion of the DESD in 2014, RCEs committed to further generating, accelerating and mainstreaming ESD by implementing the Global Action Programme (GAP) on ESD and contributing to the realisation of the Sustainable Development” (United Nations University, 2012). RCEs played a key role in facilitating the GAP on ESD (Vaughter et al., 2022) and now play a role in pursuing the UNESCO ESD for 2030 Roadmap with its five priority areas of action: advancing policy, transforming learning environments, building capacities of educators, empowering and mobilising youth, and accelerating local level actions (UNESCO, 2021). However, they also engage critically with globalising narratives whilst supporting local projects (Lotz-Sisitka et al., 2010). There are currently over 170 RCEs around the world, forming the Global Network of RCEs. Each RCE is tasked to consider governance, collaboration, research, and development and support of transformative education (RCE Network, 2022; Vaughter et al., 2022). In this way, the Global Network of RCEs attempts to cascade the global agenda into local places and processes through an emergent, self-declared, dynamic constitution of different actors, enabling the capture of interest, and ability within a loosely-coupled framework.

The governance structure of an RCE is key to outputs and impacts (Ng'ang'a et al., 2021). Successful RCEs often have a light institutional administration with active working groups, such as RCE Saskatchewan (Dahms et al., 2008). The oversight (effective director) on a RCE may rotate among key personnel, leading to shared workload but collaborative challenges (Fadeeva et al., 2014). In Japan, RCEs differ in focus and structure, but several have successfully established consortia for ESD and offer a collaborative platform with some national coordination that collectively model the kind of multi-scale, polycentric governance style required for sustainable development (Ofei-Manu and Shimano, 2012). Collectively, RCEs significantly support learning to underpin the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) across formal and non-formal contexts (Vaughter et al., 2022).

Most RCEs are hosted by universities, with the intention of enabling engagement with additional actors and strengthening the focus of universities on ESD. Universities that lead in sustainability are places of transformation and possibility (Sterling et al., 2013). They can support learners to become change agents (White, 2015), consider their operations, nurture university community (White and Harder, 2013), engage with their external communities (Mosier and Ruxton, 2018), and undertake sustainability research which is holistic, participatory, reflexive, innovative, and links theory and practise (White, 2013). Sustainable universities thus contribute to the transition to sustainability and are well-placed to host networks for scholarship and learning for sustainability. Some RCEs are firmly embedded in relevant university departments, such as RCE Makana in South Africa, whilst others represent adjacent interests or are championed by individuals (Ng'ang'a et al., 2021). Whilst many RCEs receive in-kind donations from host universities such as time, office resources and meeting spaces, these authors found that funding for staff and project activities can be difficult to acquire. RCE income sometimes included partial funding from host universities or private sector and occasionally membership fees, and some RCEs did not even have an office or core staff support. They suggested that more transparent governance models, appointment of RCE coordinators by RCE member panels and greater synergy between RCEs could enhance impact. Limited diversity and communication issues can also limit efficacy (Ofei-Manu and Shimano, 2012).

These analyses demonstrate that RCEs offer an institutional framework that can be adapted to context and location, and in response to resource opportunities or scarcities. Much of the critical reflection focuses on cross-sectoral (formal, informal, and non-formal) or scalar (global to local) interactions between stakeholders. However, there is evidence that RCEs can support learning in and with communities, with Indigenous Peoples and in relation to local environments (Fadeeva et al., 2014; Vaughter et al., 2022). Korean RCEs “value the specific cultural, historic and natural background of their communities” (Fadeeva et al., 2014, p. 63) and RCE Guatemala was able to integrate Mayan worldviews (Fadeeva et al., 2014, p. 93). Ontological plurality, local pragmatism, critical selection of methods and partnerships and the bringing in of nature are essential in RCE function (Lotz-Sisitka, 2009). However, there is little information available on how different RCEs bring in nature and how nature-culture interactions influence and are influenced by RCEs. This paper helps to address this gap.

RCE Scotland was formally launched in 2013, but evolved from previous networks. It has successfully undertaken many activities with diverse groups of stakeholders. This paper is a reflection by key individuals involved in this process over the past 10 years, and an exploration of how this local initiative connects to global efforts for a transition to sustainability. We ask, firstly, how Scotland's history, culture, and context have informed and facilitated our approach to ESD and the establishment of our RCE. Secondly, we ask how our goals and activities link to culture and context, and thirdly, what lessons are learnt and what recommendations can be made for ESD and RCEs. We do this by synthesising our history and educational principles, then describing and analysing how we established RCE Scotland, including dialogical processes, governance structures and a Delphi process to define our vision and mission, map opportunities, and inform a strategic plan. We then analyse and evaluate selected activities, with interrogation of how these link to our culture and context. Finally, we critically reflect on how our approach enables us and our RCE to be embedded in place, nature and culture whilst linking to global processes and pursuits. We argue for locally contextualised approaches to ESD that draw on intellectual competencies (head) and action-based approaches (hands) whilst acknowledging the need for motivation grounded in the earth, enlivened by the arts, held by heritage and inspired by cross cultural debate (heart).

We firstly briefly synthesise aspects of Scotland's history and culture to frame the establishment of RCE Scotland and the context within which we work. In so doing, we draw on key philosophers and planners, in particular Sir Patrick Geddes, whose ideas still underpin some educational principles in Scotland today. From this synthesis, we identified several key issues, which could potentially have shaped the emergence and practise of ESD in Scotland today.

As we established RCE Scotland, we pursued a dialogical process. We describe this process and critically analyse the governance structures and strategic priorities that emerged. In 2013, the scope of learning for sustainability, gaps, opportunities and resources in Scotland and potential partnerships were explored in Workshop 1 through plenary debates and focus groups each with 6–8 participants. Invitations were sent to RCE members (~600 individuals) and 45 participants attended, from school, university, college, NGO, community and local and, national government sectors. Ages ranged from ~19 to 67 years old. In 2014, Workshop 2 enabled us to assess Delphi results, comment on initial strategic plans and highlight priorities, with many of the same participants and using the same methods.

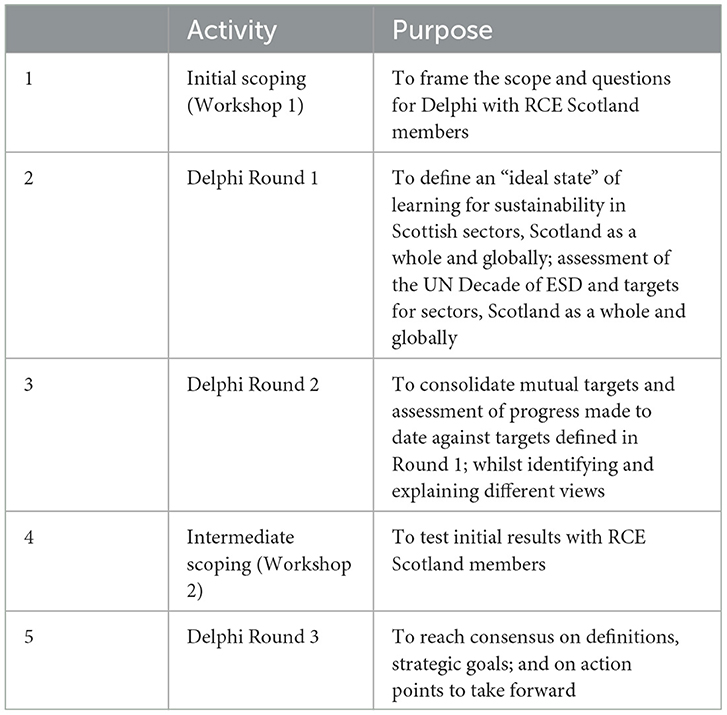

In order to develop deeper understanding and inform our strategy, we conducted a Delphi process in 2013-4 (Table 1). A Delphi process consists of rounds of questions in which informed respondents offer their perspectives, usually enabling both qualitative and quantitative assessment of an issue and convergence to a consensus situation (Devaney and Henchion, 2018). In our process, three rounds of questions and two scoping phases were undertaken with the 12 RCE Scotland Steering Group members plus 2 additional key informants who were selected to ensure coverage across the Further Education (FE; college) sector and to offer experience from the last 30 years of ESD. Fourteen participants responded to the Round 1 Delphi questions, 11 to Round 2, and 11 to Round 3. Some respondents described their experience as sectoral and others as task related; a few articulated diverse interests. Most respondents had multi-sectoral experience and some indicated long-term involvement in LfS (since its emergence). All respondents cited local and national level experience, with 10 also citing international experience. Respondents identified with NGOs (seven respondents); Higher Education (HE) (7); School (5); community (5); Government (3) and Local Authority (3) with some experience across FE and Early Years also noted.

Table 1. Delphi and scoping activities undertaken with RCE Scotland Steering Group and members during the inaugural year of RCE Scotland in 2013.

The processes above and subsequent member engagement informed our initial RCE Strategy by emphasising the cross sectoral approach, nature and culture. The Strategy has since been updated on a 3 or 5 year cycle, and our Action Plan is updated annually through prioritisation with the Steering Group, detailing with Secretariat and Chair of the Steering Group and final approval with Steering Group. In this paper, we assessed if and how RCE activities aligned with the key aspects of culture and context identified above, and responses from RCE Members. We identified indicative activities across the spread of our five strategic goals that represented a range of forms and important contributions to ESD in Scotland. We analysed their topical focus, form, target audience, impacts and ways in which they linked to culture and context. We drew on activity plans and invitations, individual event feedback forms, workshop reports, reflections from the Steering Group Executive, Member surveys and social media responses to illustrate purpose, form and responses.

The Scottish landscape is considered to be iconic, with hills and lochs to west and north romanticised in historic visions of Victorian Scotland and in contemporary film (e.g., Outlander). There is a rugged shoreline and regions that are agriculturally rich. Most of Scotland's population of 5.48 million (2021 Census) lives in the “Central Belt.” Scotland has been in a political union with England since 1707, but has retained distinctive legal, educational, and religious institutions. While this has enabled it to maintain aspects of a separate cultural identity within the union, there have been pressures for more powers to be devolved, if not indeed returned to Scotland. A Scottish Parliament was re-established in 1999. In 2014, the first referendum on independence was held, and although independence was not achieved, Scotland has seen the continued resurgence of a European small-state political nationalism (Mackie, 2022) rooted in a cultural renaissance (Kockel, 2021).

Patrick Geddes (1854–1932) was and is an influential thinker and actor in education and in precursors to “sustainability” in Scotland, with ideas that have permeated much further, as detailed below. The cultural “rebirth” of Scotland towards the end of the nineteenth century (Geddes, 1895) affected all areas of the arts, although the prime genre of the Renaissance was the novel. Nan Shepherd wrote eloquently of her surrounding landscape (Shepherd, 1977). For her, “the parish was not a perimeter, but an aperture: a space through which the world could be seen” (MacFarlane, 2016, p. 62). This global perspective, grounded in the local, was an intuition shared by the parallel revival of Gaelic poetry, led by Skye-born Sorley Maclean.

The writers of the Scottish Renaissance challenged established ways of seeing the world; uncovering the hidden ideological nature of dominant representations of Scottish life and its environment. A tension arose that is often referred to as “antisyzygy”—a characteristically Scottish ability, exemplified by many protagonists of the Scottish Renaissance, not least Patrick Geddes, to hold together seemingly contradictory traditions in creative confluence. The concept of a Caledonian antisyzygy,2 introduced by Smith (1919), was elaborated further within a generalist approach that was at once philosophical, scientific, humanistic, and democratic (Davie, 1961—see below).

The peculiarly internationalist nationalism associated with ethnological thinking in Scotland has been highlighted with reference to both the influence of Hamish Henderson on cultural practise and its study in the Scottish context (Kockel and McFadyen, 2019), and the prevalence of such a perspective among the leading protagonists of the Renaissance (Kockel, 2021). Henderson made a case for “the continuity of a distinctive Scottish tradition,” placed within “a wider European cultural setting, with Scotland absorbing and assimilating ideas and practises from the latter context in its own specific and peculiar way” (Burnett, 2014, p. 224), by virtue of the fact that Scots have always been travelers and linked to other cultures (White, 1998; Harvie, 1999). One of the most famous exemplars of Scotland's unique contribution to the world was the aforementioned Patrick Geddes.

Whilst Geddes is widely credited with the concept of “think global—act local,” the precise term does not appear in his writings (Higgins and Nicol, 2010). Nonetheless, its conceptual and practical development runs through his work, particularly in Cities in Evolution (Geddes, 1915); and, given the period of context and date of his work, represents one clear way of expressing the Caledonian antisyzygy of an internationalist nationalism. Geddes also introduced the triad Place—Work—Folk as an innovative way of thinking about and communicating the interrelationships of people with their localities, and applied this approach in his work in town and regional planning (Meller, 1990, p. 45–52). His “thinking machines” have subsequently been applied by ethnologists, geographers, and planners to explore the connections between culture and nature through the prism of “place” (see e.g., Kockel, 2008). Further, his triad Heart-Hand-Head (Geddes, 1919, 1949) has emerged as something of a rallying call for those arguing for a more experiential and practical approach to education (Higgins and Nicol, 2010). This approach resonates with the work of earlier European educational philosophers such as Comenius (1592–1670) and Pestalozzi (1746–1827), and specifically relates to the developmental “stages” of affective, physical and intellectual development of children, which Geddes argued should be emphasised in that order of priority, “for in that order they develop” (Geddes, 1949, p. 228).

Geddes drew deeply on cultural traditions and history, believing that art, drawing on folklore and tradition, creatively expressed a society's collective memory, thereby manifesting place. Geddes was, in some ways, very much a modernist; at the same time, he was an enthusiastic cultural revivalist (see Boardman, 1978; Meller, 1990). This antisyzygy is resolved, because for Geddes, “a sustainable future required an understanding of the past … and his modernism did not simply learn from the past, it depended on it” (Macdonald, 2020, p. 146). Cultural revivalism and modernism are so profoundly intertwined that “one can see them as two sides of the same early twentieth-century coin” (Macdonald, 2020, p. 146).

Holding antisyzygies such as this in a kind of creative confluence of perspective has been described as characteristic of a “democratic intellect” (Davie, 1961) that is both foundation and expression of a distinct political culture. McFadyen and Nic Craith (2019) argue that this democratic narrative has been influenced by Europe's intellectual heritage. Their analysis concentrates on Scotland's intellectual and ideological heritage, with its roots in the concept of a “democratic intellect” in education (our emphasis) as well as in Continental European political thought. Scotland has long been associated with an egalitarian ethos. The Declaration of Arbroath (1320)—described as “Europe's earliest nationalist manifesto” (Ascherson, 2003, p. 18)—argued that a king owed his position to his peers rather than to God and linked to the notion of the “lad o' pairts,” which emphasises an individual's potential to rise into good fortune from humble beginnings—a potential often attributed to Scotland's distinctive education system.

Guided by a philosophy of common sense that was both socially responsible and epistemological, Scottish students were encouraged to investigate connections between subjects, their ethical and intellectual relationships, and the functional application of their knowledge in the community. From this generalist foundation, specialised skills could be developed within a philosophical perspective that would enable the student always to refer their expertise back to its position and significance in the generalist context. This Scottish ideal of generalism was eroded by wider UK and global trends (Davie, 1986) but persists in aspects of school and university education policy in Scotland.

Connection with the land, landscape, and nature through working class roles such as crofter, fisherman and farmer, and later more recreational activities such as walking, mountaineering, and canoeing, created the basis of support for a strong outdoor learning educational approach (Higgins, 2002), which has become a key feature of the Scottish concept of Learning for Sustainability.

Contemporary Scotland integrates “New Scots” into a complex shared cultural identity with an associated heritage and future, rather than via some “shallow essentialist” identikit (Kockel, 2017). Applied initially to migrants arriving during the 1960's, mainly from Commonwealth countries, the term “New Scots” today extends to comprise migrants from other origins.

Following the internationalist-nationalist vision championed first by the Scottish Renaissance, and supported by the concept of a democratic intellect, twenty-first century Scotland is emerging as a small but globally well-connected nation (Mackie, 2022) where belonging has largely become a matter of inclusion. A Scottish identity is emerging that is built less on a (Romantic) ethnic or (Enlightened) civic vision of its nation, but instead on what one might call a “community of spirit” defined by particular shared political concerns, together with a collective commitment to stewardship of place in all its aspects. The concept of “community” persists in Scotland, partly in relation to activism for land rights, environment and self-determination (McIntosh, 2004; Wightman, 2010; Meyerricks and White, 2021), although also through deep connection with land, culture and place (McIntosh, 2004).

In this cultural climate, it is becoming necessary and more possible to confront the darker sides of heritage while navigating sustainable futures. Racism, Scotland's complicity in the imperial project of British colonialism and some powers of the Kirk (Church) are being addressed, and this is allowing traditional ecological knowledge and indigenous cultural cosmovisions gradually to reassert themselves (see contributions to Scottish Affairs 2021/22).

The history above provides cultural context for ESD in Scotland. We provide here a synthesis of the main factors identified (Table 2). Whilst these aspects are not exhaustive, they overlap, and they are not exclusive to Scotland; they do illustrate identity, relationship with nature and place, educational principles, a framing for local yet internationalised action and some influences on sustainable development. Common threads weaving throughout include the relationships between local and global, people and place, and educational plurality.

Having explored the culture and context of Scotland in relation to sustainable development, education, and Education for Sustainable Development, we now turn to the emergence of Scotland's RCE.

Scotland's RCE was formally recognised by the United Nations University in 2012, and was launched in 2013. Its emergence resulted from Scotland's longstanding commitment to education, with growing interests in environmental and then sustainability education, outdoor learning, and critical pedagogies aligned with culture and context as described above. There was also a favourable policy context immediately prior to the RCE application. The UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (DESD; 2005–2014) had stimulated coordinated activity and catalysed some policy and practise progress in Scotland and elsewhere (Martin et al., 2013; UK National Commission for UNESCO, 2013). The Scottish Government maintained a commitment to ESD through strategies and Action Plans setting out expectations for schools, universities and colleges and lifelong learning (community learning and development, workplace, and public awareness; Scottish Government, 2010; Scottish Executive, 2016).

In parallel, a significant discussion on formal education policy took place in Scotland (Sustainable Development Commission., 2010; Learning Teaching Scotland, 2011). One Planet Schools (Education Scotland, 2012) included a values-focussed definition of a re-conceptualised approach called “Learning for Sustainability” (LfS)—a whole school approach to sustainability, integrating Education for Sustainable Development, Global Citizenship and Outdoor Learning. It also included LfS as an entitlement for all learners, and a requirement of all teachers (Education Scotland, 2012). Scotland's “Curriculum for Excellence” (CfE) offered “project based, holistic education” and “provided the overarching philosophical, pedagogical, and practical framework and context in which ESD ought to be applied” (UK National Commission for UNESCO, 2013). A strong Third Sector contribution to early-years and schools promoted outdoor nurseries and global citizenship education, but there remained the need for curriculum integration and for stronger CfE implementation at secondary school level (UK National Commission for UNESCO, 2013). In Universities (HE) and Colleges (FE), guidance from the Scottish Funding Council focused almost solely on operational campus sustainability (Sustainable Development Commission., 2010). Whilst Scotland had made great progress at school level, the notion of education as empowerment was, at the same time, being eroded in universities (Doring, 2002; Higgins and Lavery, 2013).

It was recognised that lifelong learning needed further support, with the Action Plans not recognising or deepening community action such as that provided by Transition Towns groups, Development Trusts and eco-congregations (Sustainable Development Commission., 2010). During this period, Scottish Parliament (2003) and the emerging Scottish Parliament (2015) were further strengthening potential for community learning and action. There was less progress on ESD in relation to business, agriculture, forestry, marine management, and other sectors.

The desire to maintain and build momentum across the broad area of ESD (Lavery and Smyth, 2003) prompted a cross sectoral group of educators to develop and submit an application for a RCE for Scotland. The application insisted, firstly, that we wished to retain the community of practise pre-existing across all areas of Scotland, and that the partnership between the more urbanised “Central Belt” and the more rural western and northern regions was essential to link culture and resource and ensure that ESD could be supported across all sectors. Secondly, the application was framed as “Learning for Sustainability” (LfS) to reflect the education policy development at the time, bringing together the different communities of interest supporting the interconnected concepts of global citizenship, outdoor learning and ESD, and emphasising the intention to go beyond formal education. All the universities in Scotland submitted letters of support, as did the Scottish Government and school education and higher education agencies. It was approved by the United Nations University in December 2012.

To include learning in formal, informal and non-formal contexts, we brought together stakeholders from different sectors and built from existing networks (White and King, 2015). Workshop 1 focus group discussions elicited diverse and ambitious views on LfS, including that it represented “a personal journey,” and a “pedagogy for life.” Participants suggested that LfS “addresses nature deficit disorder and symptoms” and empowers people to ask difficult questions about their own and societal assumptions. They proposed that perhaps excellent learning for sustainability merely promotes excellent education; all education should provoke reflection and action, combine different forms of learning, empower individuals and build society. It was stated that such concepts can and must be understood differently by different actors, and sustainability to some extent is about respecting and working with diversity.

Participants proposed how such concepts need to be put into practise in accessible and often simple ways; getting children outside, helping communities celebrate together, promoting organisational change, embedding care. The groups explored what the relative roles of formal, informal and non-formal educational experiences were in LfS. It was noted how an individual may experience forms of LfS in different ways at different stages of their life, and this experience will be individualistic. Participants also identified potential challenges with the transitions from one learning stage to another; for example, from schools with good LfS into Universities. The lack of political literacy in young people and possible reasons for this were lamented as being a barrier in promoting civic engagement and reinforcement of a set of values beyond the individual. As well as topics related to sustainable development, pedagogy was agreed by all participants to be critical. There was strong support for approaches such as outdoor, place based or experiential learning, for example, to lead to transformative learning; and learning practises such as reflexivity, participatory engagement, shared, and embodied experiences to deepen the potential for learning for sustainability. Important ESD topics included not only environmental issues but also issues around, for example, global citizenship, social justice, development, ethics and values, and behaviours.

It was considered that learning can occur through formal teaching or through experience and practise; and that research, teaching and practise feed back into each other and are interlinked. Participants identified attributes and strategies to pursue LfS and concluded that RCE Scotland should: (a) share good practise across sectors and organisations; (b) develop a “pan sectoral” approach to actively share experiences and ideas; (c) leverage partnership working; (d) enable HE and FE to promote leaders' and vocational input; (e) form practical networks; (f) pursue advocacy for sector and policy leadership and (g) undertake research in key areas.

As a “network organisation,” the RCE needed to support a network of individuals, organisations and institutions. It was discussed that there was a difficult balance between collaborative and competitive working strategies. The focus groups suggested that we should seek funding for projects whilst remembering our main priorities as an internationally acknowledged RCE in ESD; we should pursue policy as well as practise; and we should address the needs and requests of RCE members. Suggestions for thematic strategic aims were developed that still underpin our current strategy (2018–2022) and action plan.

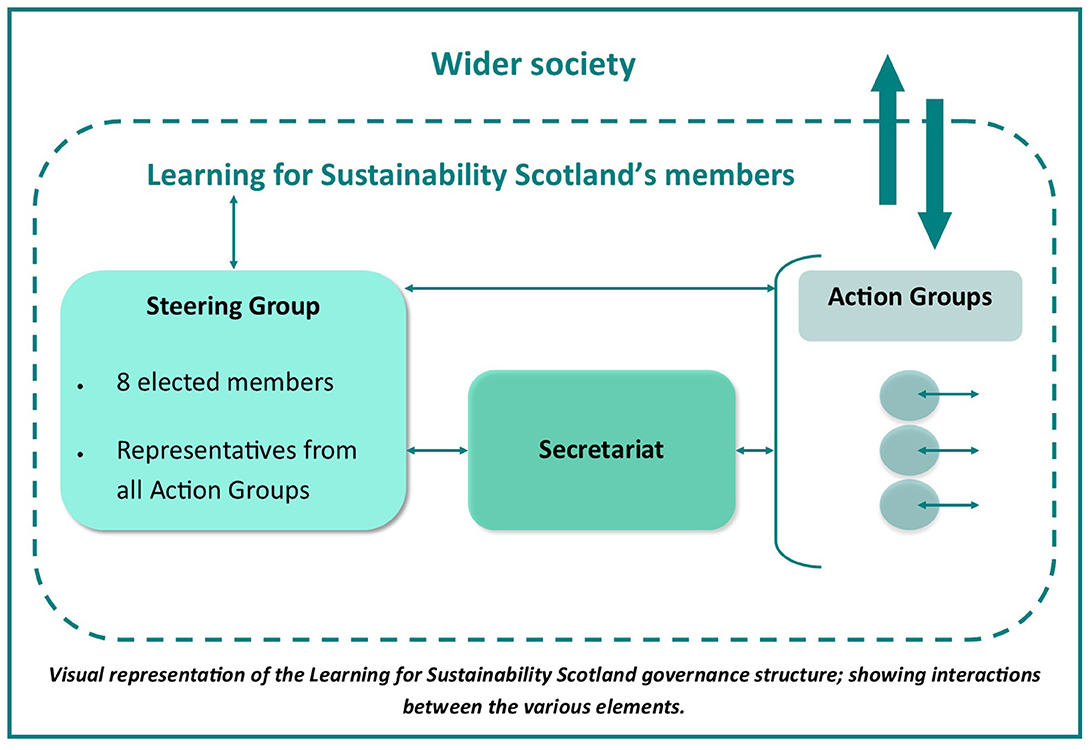

During and informed by the dialogical process, a governance structure was established for RCE Scotland (Figure 1). A Director was appointed at the hosting institution, the University of Edinburgh, which agreed to provide office, Human Resources and technical support. In addition to the Director, the Secretariat also included a development manager and administrative officer. A constitution was drafted and adopted. The inaugural Steering Group was elected through an open nomination and electoral process, and a Steering Group Chair was elected. It was planned that activities be undertaken either through member Task Groups with clearly defined and time limited aims, or through funded and resourced projects that draw in employed and volunteer resource. Events were to be run by the Secretariat, Task Groups or collaborative groups. Communication and practise sharing developed mainly through a monthly eBulletin, an Annual General Meeting and events plus occasional briefing papers, research and other activities.

Figure 1. Governance structure developed for RCE Scotland in 2013 (adapted from the RCE Scotland strategic and work plan).

This round began by addressing what “the ideal state of LfS” should be at different scales, firstly within different sectors in Scotland, then across Scotland and finally globally. This question offered participants the opportunity to develop a vision and articulate aspirations combining the form, extent, framing, and initial consequences of LfS before considering appropriate targets.

Participants suggested that LfS should be embedded in all sectors, permeating all sectors and integrated into systems or learning (10 respondents). It was stated that LfS should be woven across all subjects—“not an add-on.” More strongly, one participant suggested that LfS should be “at the core of each sector's work, training and strategy.” Secondly, participants proposed that in an ideal situation, all Scottish sectors would have understanding and respect for the principles and ethos of LfS (six respondents). A strong, well-supported network of people (N = 2) and statutory framework (N = 2) were proposed. It was suggested that LfS enable freedom from binary thinking, a state of mind, an ethos of responsibility, fostering of sense of community, (re)connection to place, and embodiment in institutions. Many participants also made sector specific comments. Our policy makers need to be “sensible, sensitive and brave” and be held to account; we need political leadership and commitment. LfS should enable a fair and just/flourishing society (N = 3) and offer empowerment (N = 2) and wellbeing (N = 1) whilst ensuring that we live within ecological limits (N = 4). There was recognition of scale with people tackling issues as individuals, in communities and in work places (N = 2); and working with local heritage and sense of place whilst engaging with those beyond Scotland (N = 2). One participant reminded us that a community can be both inclusive and exclusive; and definition of a national boundary is both useful and problematic as it cuts across communities of practise. It was suggested that a culture of tolerance and diversity be encouraged. Tensions with the market driven state were noted. Participants were asked to comment on UN and Scottish targets for LfS. It was reported that sectoral division of goals was necessary to enable sector specific progress but this may have meant that the focus on “structural change within society promoted by UNESCO was lost,” limiting the capacity for sustainability transformation (Voulvoulis et al., 2022).

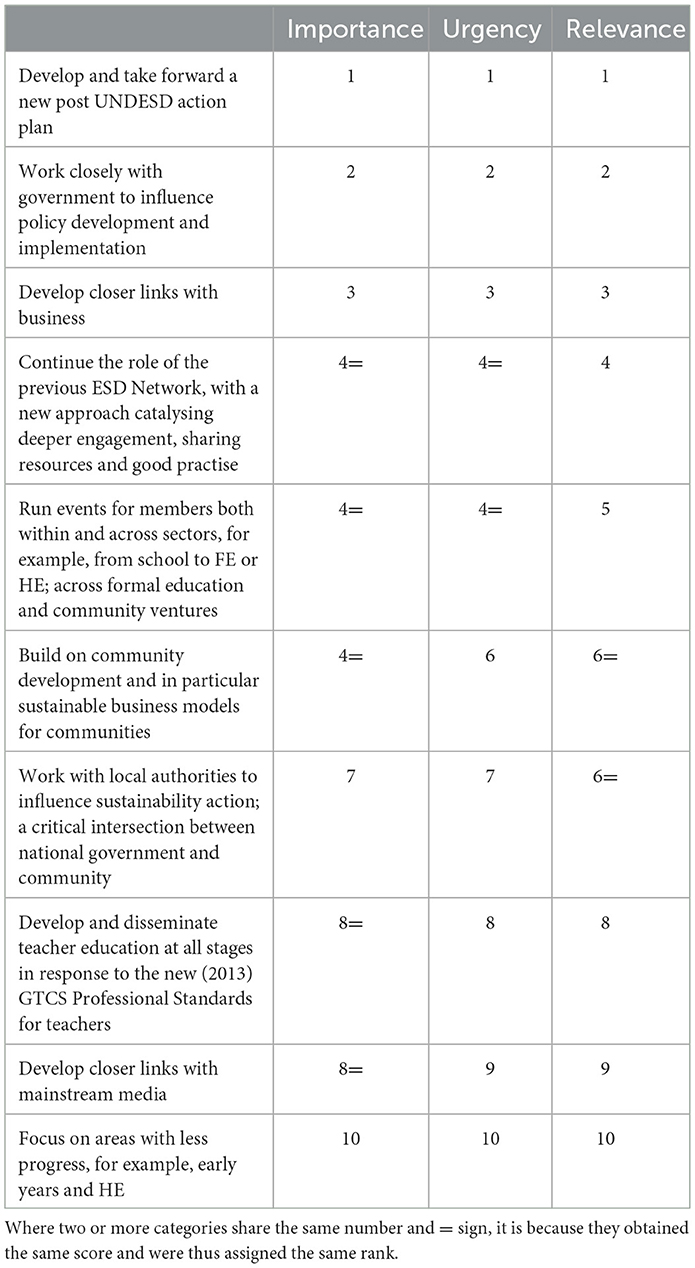

The next Delphi round sought consensus on a definition and framing for LfS and more specific perspectives on the extent to which progress has been made in LfS at different scales. Finally, Delphi respondents were asked to focus on the opportunities for the RCE, given the preceding reflection and analysis. They were asked to rank opportunities for suggested actions that had previously been identified by members at the Workshop 1 and by the Steering Group in relation to overall importance, prioritisation and applicability (Table 3). Each suggested action was scored by each individual and scores were added together to give ranked prioritisation across all Delphi participants.

Table 3. Ranked prioritisation of suggested actions for the new RCE (ranking from 1 most important/urgent/relevant to 11 least so).

In line with the participatory ethos of sustainability, we sought the opinions of a wider group of people after Round 2. Participants at Workshop 2 also ranked future priorities. Ranking broadly mirrored that of the Delphi participants (data not shown). In addition, they wanted to see a focus on areas other than formal education moving forward, especially in communities (N = 4). Other comments included need for wider public debate and the value of interdisciplinary working.

The framing of LfS was further modified in Round 3, with sustainability being explicitly introduced as being more than about environmental concerns, and a more radical framing, “challenging the accepted worldview.” It was suggested that we need to focus more on “personal sustainability,” particularly “through pedagogical interventions such as outdoor learning and …… mindfulness.” It was also proposed that we unpack the types of learning included in the term, acknowledging “everything from information and awareness to capacity building to community empowerment to formal education at all levels; a recognition of different kinds and levels of learning, each appropriate for context.” One participant commented that learning for sustainability can be framed as an on-going process of people learning and reflecting, being “empowered and equipped to deal with the uncertainty and change which are a result of all the complex challenges that the world faces,” capturing a sense of resilience. It was said that “The collaborative culture of [RCE Scotland] ensures a ‘non-partisan,' unbiased, and truly independent model for the development and dissemination of learning, teaching, and ‘good practise.”' One participant warned that there was a need for constant vigilance to ensure the conversation was opened up to members and sectors of society currently less involved, both home and abroad. Paradoxically, individuals wanted both more detail and yet greater simplicity in defining the ideal state of learning for sustainability.

A synthesis of member focus groups, three Delphi rounds and sense checking with members again led us to develop a full (see Supplementary material 1) and an abridged definition of LfS below, which served as the framing of ESD for RCE Scotland.

Learning for sustainability enables visioning of culturally and place-specific futures and contributes to the creation of a fair and flourishing society and empowerment, particularly of the currently disempowered, whilst ensuring we live within ecological limits. Such learning uses innovative, reflexive, and potentially transformative pedagogies and curricula to enable skills development and resilience and encourage people to explore value based worldviews. Learning promoted action requires a systems based, interdisciplinary, partnership approach with strong leadership and integration across formal education and informal (such as community, business) and non-formal (such as media, culture) sectors. The role of LfS Scotland is to support networking and collaboration, releasing the potential of individuals, communities and sectors to create human and planetary wellbeing within local, national, and global contexts.

Strategic goals were identified through the extensive period of consultation described above, with further strategies and action plans being developed by the Steering Group each 3–5 year period. Our 2020–25 strategic goals are explained in Table 4.

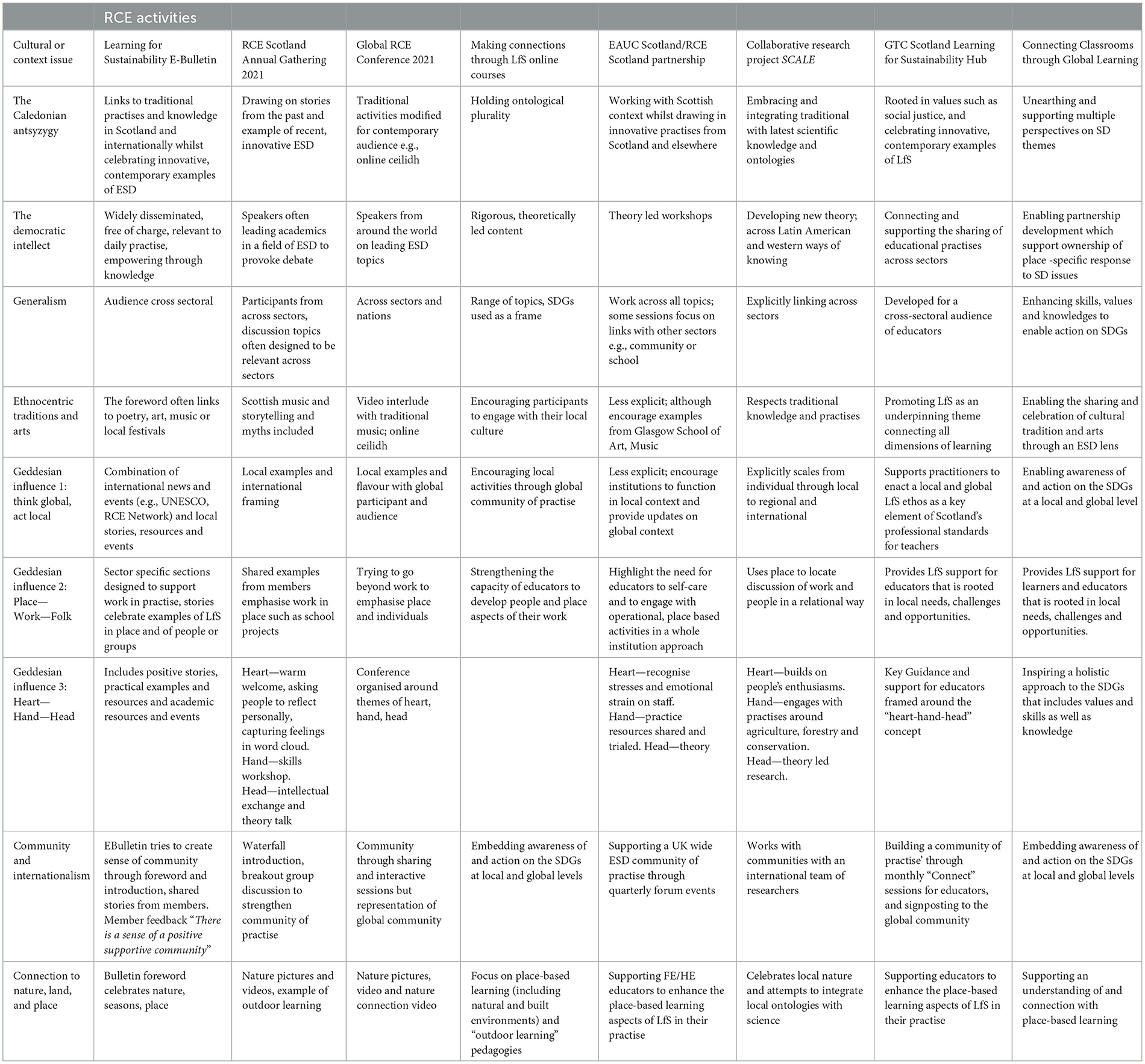

In order to evaluate how our approach and activities link to culture and context, we analysed 8 indicative activities (Table 5, Supplementary Table S1). Four of the activities are illustrated here in more detail through vignettes to illustrate a range of activities, forms of successful initiatives and different ways of engaging with culture and context.

Table 5. Attributes of activities conducted by RCE Scotland and relevance to cultural context for ESD.

A free monthly e-Bulletin shares Learning for Sustainability news, events, resources, policies and images for and from all sectors in Scotland. It has a distribution list to over 1,000 members of Scotland's ESD community and is accessed by a wider audience via our social media and website channels. This activity maintains a regular sharing of practise and conversation, enhancing the sense of a community of practise. A key feature is the nature-grounded, values-based, monthly message from the Steering Group; drawing on seasonal aspects of Scotland's natural and cultural heritage and often featuring photographs of Scottish landscapes or quotes from Scots or other writers. Feedback drawn from the bi-annual member survey 2020 suggested that “There is a sense of a positive supportive community,” “such a good variety across a broad range.” It demonstrated shared practise since “I have also posted articles to share what we are doing” and it includes “up to date resources and relevant news which I can use to adapt my practice” (see Supplementary Table S1 for evaluation feedback for all activities).

The Annual Gathering is linked to the AGM for RCE Scotland members: individuals and organisations from across formal, informal and non-formal education sectors, as well as policy- and decision-makers in Scotland; plus invited speakers and others according to the particular theme. We have now transitioned to two annual sessions with an in-person, festive, networking meeting (speaker plus creative activity) plus an online collaborative workshop. The 2021 Gathering focused on “Stories for Sustainability: transformational learning through the personal and political.” Nearly 100 members engaged with inspiring stories from the school, community and Further Education sectors, before sharing and celebrating their own stories of transformational learning in breakout sessions. Video interludes showed Scottish landscapes and places and learning in action, set to Scottish music. There were traditional stories from a professional Scottish storyteller. The meeting concluded with an invitation to “Dream Forward:” imagining and connecting with each other to co-create a sustainable future.

RCE Scotland co-created events with United Nations University Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability (UNU-IAS) and hosted two Global RCE webinars (February and June 2021) during the COVID-19 pandemic, and then an online Global RCE Conference (November 2021) on the theme of “Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals: action through learning in a time of global crises.” This complex, online, 3 day event registered over 300 delegates from 170 RCEs from across 61 member countries; as well as RCE Scotland members, policy and decision-makers in Scotland, and others. Government Ministers in Japan and Scotland, international and national NGOs, youth activists and others from across the RCE Network contributed. The event enabled networking and sharing good practise aligned to the five strategic aims of the UN 2030 ESD Action Plan. Outputs and outcomes were disseminated by UNU-IAS and RCE Scotland across the whole Global RCE Network and to a wider audience via our combined social media/website channels. These events were the first to bring the entire Global RCE Network together in a digital space.

The 2021 Global Conference used a “Hearts, Hands, and Heads” approach to enable exploration of affective, behavioural and cognitive approaches to ESD. Delegates shared culture, practise and initiatives and participated in diverse workshops. An online ceilidh at the end of the 2nd day provided delegates with an insight into Scottish culture, video interludes of Scotland were shown and a poetic narrative of seasonal change was read to accompaniment of a slideshow of Scottish nature images. Post-event evaluation was extremely positive.

Connecting Classrooms through Global Learning (CCGL) was a programme that supported educators, learners and their communities across the early learning and childcare, primary, secondary, additional support needs (ASN) and college sectors from 33 participating countries in the UK, Middle East, Africa and South Asia. Managed by a Consortium of partners, led by RCE Scotland, on behalf of the British Council and UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), the programme ran from 2018 to 2021. It supported educators and learners to take collaborative action on the UN SDGs through partnerships on either a 1:1 or “cluster” basis with other settings across Scotland, the UK and overseas. CCGL aimed to create an integrated offer of support for partnership work and fully-funded professional learning.

After 3 years, 234 (9%) of Scottish settings were engaging in funded or facilitated collaborative partnerships, 900 educational practitioners from 451 settings had engaged in professional learning activity across Scotland, and a further 318 settings had engaged in webinars and other activities offered by the programme. Partnerships have, in many cases, evolved into long-lasting friendships between educators and learners and a desire to engage in future collaborations on sustainability topics; such as the “1.5MAX” initiative, connecting schools in Scotland, Malawi, Mozambique, and Nepal to take action on climate change. Feedback from teachers and learners elucidated positive outcomes and impacts.

All activities were analysed for evidence of attributes reflecting the aspects of Scotland's cultural context that might be relevant to ESD (Table 3). A summary is presented in Table 4. It can be seen that the activities are rooted in Scotland's culture and context.

We have provided a cultural context for Scotland, with an analysis of key aspects of relevance for ESD, and we analysed the emergence of the governance structure, definitions, and scope of RCE Scotland. We also investigated activities in relation to strategic goals and our cultural context.

RCE Scotland's purpose was developed through an intentional dialogical approach, including a Delphi process, which led to its establishment, governance and strategic goals. The Delphi process allowed us to draw on the expertise of key informants (Devaney and Henchion, 2018) whilst wider member engagement empowered members to determine the future and shape of RCE Scotland. We thus redefined our field of theory and practise in a manner that was inclusive yet boundaried, generalist yet with specific inputs, and that encouraged reflection by and between practitioners and academics. This transparent, dialogical process and the democratic election of a Steering Group illustrate successful governance features identified by Fadeeva et al. (2014), Ng'ang'a et al. (2021), and Vaughter et al. (2022). Our indicative activities demonstrated how we have been successful in meeting our strategic goals whilst drawing on culture and context to provide a flourishing environment for ESD in Scotland. We begin to answer how to “bring in nature” to RCEs (Lotz-Sisitka, 2009).

We now address our research questions. We critically discuss, firstly, how Scotland's history, culture and context have informed and facilitated the establishment of our RCE and our overall approach to ESD, and, secondly, ways by which many of our activities have been influenced by culture and context. In so doing, we do not argue that culture and context is the only influence, but rather that they are present, relevant and a part of the success to date of RCE Scotland. From our analysis of culture and context, we demonstrate how attributes are reflected in RCE Scotland.

We argued successfully for the creation of one RCE across Scotland, thus allowing us to link rural areas and groups living in iconic “wild” landscapes, maintaining traditional creative arts and practises, together with urban organisations and groups that tackle social inequalities and work with elite, prosperous institutions. The Scottish population is dispersed, but is sufficiently small and connected to feel like one population and is connected by difficult as well as positive aspects of history. RCE Scotland is thus a whole nation RCE that represents a coherent (yet diverse) community and that functions at its given scale. The focus is on strengthening the “network organisation.” Rather than competing with other bodies, it works in collaboration. It has offered a model for some other RCEs, such as Belarus and Wales, to retain their national focus. The scale, coherence and intention are important and early discussions highlighted that a single RCE would not work at UK level, for example; the devolved nations have specific characteristics (Martin et al., 2013).

Whilst there is much debate on a Scottish identity (McDermid and Sharp, 2020), the identity as expressed in RCE Scotland is linked to the Scotland of place and nature (see McIntosh, 2004). Remote rural communities retaining and reviving some regenerative land practises are recognised, but also the vibrant, more urban “Central Belt,” from which people connect to rural and natural settings and cultures through recreation, history, and the creative arts. Connection to nature reinforces the sense of community in RCE Scotland; resonating with members; for example, through seasonal, specific and often culturally-linked monthly eBulletin messages and in short video pieces in the AGM. This identity is also communicated to the wider RCE Network; for example, in film and poetry in the Global RCE Conference. A Scottish identity is thus visible in our communications, such as the eBulletin, and our gatherings, such as the Annual General Meeting. At the same time, the Caledonian antsyzygy—“the presence of duelling polarities within one entity, thought of as typical for the Scottish psyche and literature” (Smith, 1919), is present. In RCE Scotland, we embrace our distinctive Scottish traditions whilst welcoming people and customs from elsewhere, as shown in the Global RCE conference. We are passionate about our local places and diverse landscapes, as shown in our eBulletin and Global RCE conference creative arts pieces, whilst entering vigorously into global debates, as demonstrated in Connecting Classrooms through Global Learning, our Global RCE engagement and our international research collaborations. We celebrate both cultural revivalism, demonstrated in our use of traditional practises such as ceilidh and music in events, and modernism, for example, in a recent exhibition with Climate Sisters.3 We honour the wild, whilst addressing impacts of modification by sporting estate, agricultural, and other human practices (Wightman, 1996, 2010).

The Geddesian triads Place-Folk-Work and Heart-Hand-Head, are key threads running through the process of establishing and conducting the work of RCE Scotland. The former resonates with contemporary linkages made across community, government and professional arenas, such as in recent events and the portfolio of members contributing to the Annual Gathering, as well as connection to place (see section below). The latter concept of Heart-Hand-Head can be interpreted broadly as an original version of sustainability competencies in that it accommodates intellectual learning and knowledge whilst celebrating development of capacities for emotional engagement and action (see UNECE, 2012; Giangrande et al., 2019 for competencies descriptions). RCEs, being based in Universities, often have a focus on intellectual (“Head”) activities, and RCE Scotland manifests this through research, evidence based consulting, research briefings and more. The “Hand” is also very present in ESD in Scotland through work, food growing, experiential and outdoor learning, and the persistence of traditional practises and crafts, often in a contemporary mode (Ferraro et al., 2011). RCE Scotland engages with the “Heart” through connection with self (expressed through creative arts and emotion as seen in Supplementary Table S1), connection with others (through the warm, friendly tone of communications, networking events and shared activities such as photo of the month; and intergenerational connection through, for example, traditional Storytelling) and connection with nature and place (see below). All professional learning offered connects with heart, hand and head, starting from the “heart.” Whilst self-awareness and normative/cultural awareness are included in sustainability competencies, nature connection is missing from the generally accepted competency framework (UNECE, 2012; Fadeeva et al., 2014; Giangrande et al., 2019) and we propose that it should be included in future iterations.

The generalist, holistic, systems-thinking approach is evident throughout RCE Scotland's emergence and current focus on and action as a network organisation, and thus, despite its small Secretariat, it is able to bring together individuals, organisations, and institutions with a common interest in ESD. The Steering Group intentionally includes pan-sectoral representation; with additional representation co-opted if it is felt lacking (e.g., youth representation). This ensures a diverse reach across early years, primary and secondary education, college, university, continued professional development, lifelong learning, and community. In this way, learning from one sector is transferred more easily to another (e.g., school to college). This approach thus also includes linkages across formal (e.g., schools and universities), non-formal (e.g., community), and informal arenas (e.g., culture and media), as promoted for ESD (UNESCO, 2021).

The generalist approach continues across sectors; with projects and member examples spanning food, creative arts, energy, transport, land management, agriculture and forestry, and amongst other topics. Intergenerational crossover is also seen in efforts to engage youth and elders in different projects, with one research project explicitly addressing this (see Supplementary Table S1). This enacts the need for joined up thinking and action identified in the Delphi approach. Finally, the network organisation structure creates a system with a network of networks, human, and organisational. Principles, policies, and practices of ESD are shared and grown across interconnected aspects of society, yet embedded in nature connection, creating an ecosystem of education unique to the Scottish context.

Key aspects of our culture noted above are the “lad o' pairts” influence (see above), which implies that social mobility and an egalitarian society are possible; “civics,” which includes citizenship for community; and wellbeing and community. An egalitarian society is less hierarchical, with horizontal connections, appropriate for networks. RCE Scotland developed from a prior network, but both expanded and strengthened this. A continued effort to listen to members and to create friendly spaces for frank exchanges and sharing of ideas was demonstrated by participant feedback after online events such as the Annual Gathering and online webinars. Such events and frequent feedback processes create a feeling of belonging, of civic agency, of social connection and of shared context—a sense of community (McMillan and Chavis, 1986) as well as a community of practise (Fadeeva et al., 2014). Many events and communications have a professional external face but a warm, down to earth, personal tone (see feedback comment—“I felt welcome and valued”). This collective, conversational, non-hierarchical process helps to develop a positive community of practice.

At the same time, RCE Scotland recognises innovation and excellence, such that the possibility to be different within community is also acknowledged. We hold visions of both universality and diversity. This tone is not only determined by culture but is also enhanced by the personalities of the leadership and staff within the network organisation, who deliberately promote the funny and the dour, collective and individual, traditional, and innovative. For example, many meetings begin with a moment of nature connection, such as sharing of recent harvesting or foraging. Rather than fostering a competitive environment, RCE Scotland promotes and facilitates collaboration and partnership. Through partnership, for example with EAUC, Scotland's SDG Network and Youthlink Scotland, the RCE has achieved a lot with very little in the way of specific resourcing.

Intellectual vibrancy was identified above as key in the Enlightenment and in subsequent scholarship in Scotland. This transfers into rigorous critical thinking and innovation, as highlighted in the second goal of RCE Scotland. Whilst all university groups might promote critical thinking, this insistence on “sound science” (DEFRA, 2005) has led to RCE Scotland being considered a reliable partner to undertake Research In Action Briefings, implement reviews and do research, for Scottish Government and a range of other partners and clients. This is evident, for example, in the intention to not “deliver the SDGs” but rather support action towards them whilst constructively critiquing them. Critical and reflective thinking was also evident in the time spent collating and synthesising member voices to frame and articulate ESD as “Learning for Sustainability” for the context of RCE Scotland.

Analysis of culture and context revealed a longstanding connection and identification with nature that was enforced through political reverence for “traditional” Scottish roles (e.g., crofter, fisherman, and gamekeeper) around the time of devolution, by the rural context of much of Scotland and by contemporary recreational and cultural activities. Such nature connection led to a strong custom for outdoor learning which is evident in the work of RCE Scotland and members. More than this, the support of community land ownership, and a preference for “stewardship” and regenerative practises rather than extractive approaches, were evidenced in the work of RCE Scotland. For example, the initial discussions emphasised the importance of non-formal ESD, especially community learning, and the annual gatherings include examples of community-based learning projects. This emphasis on “nature as land” underpinning the work of RCE Scotland is typical of a strong sustainability approach (Dietz and Neumayer, 2007) rather than a more capitalist view of education as existing merely to enhance employability and feed economic growth (see Sterling, 2010 for critique). There are places in Scotland rendered iconic through history that enter into the discussions and activities of RCE Scotland and infuse activities with a sense of shared place even in communities of practice. For example, the Isle of Eigg was the first location of community buy-out under recent legislation, and represents a return of the land to the people (McIntosh, 2004). Such perspectives see land not only as a property asset, managed and controlled as an economic entity, possibly even with an onus on equality in ownership patterns and property rights; but also as an important part of people's lives, worldviews and belief systems (Wightman, 1996; McIntosh, 2004). It has socio-cultural resonance. The Cairngorm mountains are places to go into (not merely walk on; Shepherd, 1977) and are represented frequently in image and poetry in eBulletins and videos. Some of the stories and myths of nature and place tell of climate change and consequences of overutilisation of resources in the past (e.g., the dunes at Culbin) and resonate with contemporary debates. A New Materialist perspective erodes the binary of humans and nature and views people, places and materials as assemblages of interrelated human and more-than-human actors that can be influenced by innovative pedagogies in ESD (Mannion, 2020).

Nature and culture are often interrelated in RCE Scotland activities; music reflects landscape, language draws on climate, film combines visual of nature with traditional music. The strong tradition of hospitality to one's community and visitors from elsewhere still prevalent today in the Highlands and Islands informed the online ceilidh held as part of the Global RCE Conference in 2021. In practices recounted by educators in teacher training sessions, a relationship with land and art is illustrated through emphasis on outdoors learning and creative place making—arts, music, poetry, literature, and craft are created in many educational settings.

Although community often has a warm, utopian connotation, it is a contested and potentially slippery concept (Meyerricks and White, 2021). Community can be exclusive as well as inclusive (Hayes-Conroy, 2008). However, in Scotland, this tendency can be limited through connection with the diaspora, a long term interest in global citizenship as part of ESD and a strong sense of justice. The mantra “think local, act global” is illustrated in the debates amongst members and Steering Group around the framing and purpose of ESD. Although there was an initial focus on ESD in Scotland, members highlighted the need to address concerns and context in the Global South, and to highlight and call out neoliberal, globalised context. Rather than imposing one set of values, they called for a diversity of perspectives and active debate over values. This plurality of perspective emerges through attempts to incorporate different voices from different immigration cohorts, from a range of socio-economic points, from different sectors and from different debates within Scotland (see eBulletin, website and Annual Gathering contributions for examples). Devolution enhanced discussions over Indigeneity—about being connected with a particular place, and not necessarily being born in that place. Gaelic references to ways of being in nature and place (such as Dauth and tuach) offer new/old insights (see debate in Scottish Affairs). Our contributions in global debates are evident through the RCE Network, international research, raising awareness and analysis of the SDGs and through making personal connections across borders (as in the Connecting Classrooms through Global Learning project).

There are many definitions of sustainable development and sustainability, and RCE Scotland spent time developing a broad definition of ESD for our context; it “enables visioning of culturally and place-specific futures.” If we see sustainability about being primarily about human generations living within “the life supporting capacity of ecosystems” (Fadeeva et al., 2014, p. 208) we neglect the needs of the more-than-human world and we diminish the importance of the relationships between humans and nature. Some RCEs do engage, for example, with Indigenous ontologies (Lotz-Sisitka, 2009; Fadeeva et al., 2014; Vaughter et al., 2022) and through programmes supporting nature connection (Vaughter et al., 2022). The celebration of “cultural plurality” by UNESCO and many RCEs (Fadeeva et al., 2014, p. 209) can evidence and encourage many forms of human-nature relationships. In this paper, we call for more emphasis on these relational aspects, to allow people to connect emotionally with ideas and practices of sustainability and to call to the heart, as proposed by Geddes. In this way we can celebrate intrinsic values of nature and go beyond the utilitarian framing that is often found in RCE activities linked to non-marginal ecosystems (Vaughter et al., 2022). “Heart” approaches are often supported especially through non-formal learning and enhance potential for transformative learning.

As noted briefly above, not all of Scotland's history and culture is positive. There is a dark side to most national histories, and Scotland is beginning to recognise and address past roles in colonialism, persistent racism and sectarianism, elitism, sexism, and Christian suppression of Indigenous cosmovisions. RCE Scotland tries to ensure representivity in gatherings, to promote decolonising curriculum material and case studies and to respect different worldviews in teacher training and research activities (see eBulletin). Such processes align with future thinking and normative competencies (Giangrande et al., 2019). On the other hand, perceived oppression, and marginalisation of Scots themselves in the past have provoked a reclaiming of language, music and cultural concepts along with discussions of diverse and contemporary indigeneity (Wightman, 2010; McIntosh, 2018).

RCE Scotland can be seen as a “success” by some measures—its persistence over 10 years, the large membership, many activities, the Global RCE conference, impacts, and feedback. Such “success,” however, has been won in a particular context and socio-political structure and with the efforts of key individuals. Education, ESD and RCEs need to be aligned with culture and context in other regions; but we should seek equivalence rather than sameness.

We now ask what lessons are learnt and what recommendations can be made for ESD more widely, for RCEs elsewhere and for our own further development. Firstly, a dialogical process engaged members and opened rather than closed definitions of ESD. These conversations continue today and maintain a dynamic process and potential for inclusivity. Secondly, the governance structure, with a small core directorate, a diverse and expert steering group, and flexible task groups and projects has enabled consistency but also opportunistic responses to context or resource. The structure as a network organisation has enabled cross-sectoral engagement and may serve as a useful model for other RCEs. Thirdly, we recommend embedding processes and practices in nature, culture and context, whilst also celebrating diversity. However, we recommend being sensitive to issues of heritage and sustainability; lessons from the past are not always easy to absorb. Understanding and critically interrogating the present and using such lessons to inform aspirations for the future can be beneficial, as we have demonstrated here.

This analysis has enabled us to critically reflect and to develop recommendations for this and other RCEs and for ESD more widely. However, the analysis was constrained by limited data on long term impacts of RCE activities. We suggest that future research explores outcomes and impacts of ESD initiatives using empirical methods. In addition, there is a need to further investigate the possibility of a nature connection competency.

Sustainability has been a thread throughout Scotland's history; at times stronger than others and varying in colour and weft. It has manifested particularly in connection to land; linking to the past whilst looking forward; rights and democracy; and education and enquiry. Education in Scotland has been used both as socialisation and as nationalism; both as a mechanism of creative and radical dissent and for conforming; both as grounding in place and nature and justification of destructive capitalist assault on the earth for resources; both for freedom from oppression through, for example, teaching Scots texts and Gaelic and traditional music, and for controlling overseas entities and peoples.

It follows that ESD is embedded in culture and context in Scotland and that this has shaped the emergence, structure and practises of RCE Scotland, along with other internal and external influences; such as the personalities of staff and members, policy changes, funding opportunities and wider global events. This study has demonstrated the importance of critically analysing historical framings and of acknowledging the diverse ways in which ESD can manifest.

ESD is needed to imagine and enable sustainability transformations in local contexts as well as at a global scale. We recommend that developed and emerging RCEs explore these aspects and intentionally develop dialogical processes to engage potential members in ongoing discussion about these aspects. The case of RCE Scotland demonstrated how powerful connection to local nature and place can be. We thus also call for a widening of the UNESCO ESD competencies to include physical, mental and emotional connection to nature and place, by enhancing pedagogical approaches that provide experiential and relational opportunities to engage the heart. As more RCEs develop, we hope they can support ESD in locally-relevant ways; drawing on cultures and contexts and on complex relationships between humans and more-than-humans to widen debates on what kind of futures we want and how to pursue these.

They relate to other case studies. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to cmVoZW1hLndoaXRlQHN0LWFuZHJld3MuYWMudWs=.

The studies involving humans were approved by University of St Andrews Teaching and Research Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. No potentially identifiable images or data are presented in this study.

RMW, UK, BK, KL, and AS contributed to conceptualisation and design of the study. The section on culture was led by UK, with contributions from AS, PH, and RMW. BK and KL led on organisation of Supplementary material. RMW led on article structure, introduction, other results, and discussion. All authors contributed to manuscript development.

This article included summary analysis of case studies or activities funded by a variety of sources, including British Council, Gordon Cook Foundation, UK Official Development Assistance, Scottish Government, General Teaching Council for Scotland, and Scottish Universities Insight Institute.

Sadly, AS passed away before publication of this article. His early input was invaluable. He is sadly missed. We are grateful to University of Edinburgh for hosting Scotland's RCE. The efforts of the RCE Steering Group, staff and members over the years are hugely appreciated.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsus.2023.1128620/full#supplementary-material

1. ^Crofter and laird are terms respectively for small scale farmer who has tenancy in a community land area and for a large scale landowner who was often the “lord” and is informally known as the laird. These terms thus represent opposite ends of the social spectrum with regards to living and farming in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland.

2. ^Derived in part from the astronomical term “syzygy,” which is the alignment of three celestial bodies.

Barragan-Jason, G., de Mazancourt, C., Parmesan, C., Singer, M. C., and Loreau, M. (2022). Human–nature connectedness as a pathway to sustainability: a global meta-analysis. Conserv. Lett. 15, e12852. doi: 10.1111/conl.12852

Boardman, P. (1978). The Worlds of Patrick Geddes: Biologist, Town Planner, Re-Educator, Peace-Warrior. London: Routledge.

Brand, R., and Karvonen, A. (2007). The ecosystem of expertise: complementary knowledges for sustainable development. Sustainability 3, 21–31. doi: 10.1080/15487733.2007.11907989

Brennan, R. E. (2018). The conservation “myths” we live by: reimagining human–nature relationships within the Scottish marine policy context. Area 50, 159–168. doi: 10.1111/area.12420

Burnett, R. (2014, August 2). This land is your land; this land is my land. Bella Caledonia. Available online at: https://bellacaledonia.org.uk/2014/08/02/this-land-is-yourland-this-land-is-my-land/

Chambers, J. M., Wyborn, C., Klenk, N. L., Ryan, M., Serban, A., Bennett, N. J., et al. (2022). Co-productive agility and four collaborative pathways to sustainability transformations. Glob. Environ. Change 72, 102422. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102422