- Department of Philosophy and Classics, Luther College at the University of Regina, Regina, SK, Canada

An important part of successful strategies for sustainable development involves altering (or, in some cases, preventing) proposals for development that are unsustainable or have significant opportunity costs relative to more sustainable alternatives. In modern democracies, development proposals normally require formal public approvals (whether at the municipal, provincial/state, or national level) with opportunities for public and specialist input and oversight as well as legal remedies where due processes are not followed. This creates an important locus for ESD, specifically educational interventions by Regional Centers of Expertise on education for sustainable development (RCEs). RCEs are able to rapidly mobilize local, regional, and global expertise to engage such processes, frequently where there are narrow time frames and complex mechanisms for public input. The paper will use a case studies approach examining strategic communications of RCE Saskatchewan with various levels of government in proposed developments within its region in Western Canada. Despite a primary commitment of governments in the RCE Saskatchewan region to economic growth with a more limited role for sustainable development, the RCE has successfully contributed to substantially altering unsustainable development proposals in a range of areas since its acknowledgment in 2007. These proposals have included forest clear-cutting, large-scale water diversions, agricultural drainage, nuclear power, road construction, and potash mining. The RCE's interventions have been modest, involving letters and formal submissions through existing government channels aimed at public officials or elected representatives involved in key stages of decision making. This paper will document some of the main elements of the formal RCE correspondence that has lead to its strategic effectiveness including the RCE's ability to draw upon independent scholarly knowledge (including expertise about governmental processes) and legitimization of local sustainability expertise. These interventions have enabled local learning, modifications of specific development proposals, and, in some cases, system-wide transformations. Importantly, however, it highlights how an older form of university scholarship associated with the rise of the humanities, namely the art of formal correspondence or letter writing, can be customized to the goal of regional education for sustainable development.

1. Introduction

Regional Centers of Expertise (RCEs) on education for sustainable development (ESD) are meant to be practical and have impact, intervening strategically in their regions through education to transform their development patterns. As an initiative of the United Nations University, RCEs too act in service of the UN's sustainable development agenda, currently expressed in the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) directing global development from 2015 to 2030 (United Nations Department of Economic Social Affairs., 2022). UNESCO as a specialized agency of the UN with a focus on education has set out 5 priority action areas. Given their regional focus, priority action area 5 “accelerating local level actions” is central for RCE activity (UNESCO., 2021). However, the question arises: what type of educational interventions can efficiently and effectively transform one's region for sustainable development? Most RCEs have limited resources so this efficiency question is important. As important, however, is the question of effectiveness. An RCE can focus on educational approaches that build sustainable development activities within a new or existing organizational structure (for example, developing a new enterprise to manage waste more sustainably within a community). However, such approaches, while laudable, are at risk if these are overwhelmed either by other organizations within their region that continue on unsustainable paths or new developments with long-term adverse or sub-optimal sustainability impacts (e.g., approval of new carbon intensive forms of production). Unsustainable market enterprises may competitively outperform new sustainable enterprises if the full costs of their activities are not internalized in their pricing. As a result, just as schools, universities, and other organizations have sought to advance “whole-institution” approaches (see McMillan and Dyball, 2009: p. 56; UNESCO, 2014: p. 30), RCEs practically need to advance “whole-region” approaches to development that place sustainable organizations and organizational practices at least on a level playing field with other developments. At the same time, a shared citizen identity suggests that the ethical norms of sustainable development should reasonably apply to all development activities and, hence, the processes that govern these developments.

The need for a whole-region approach brings to the fore a need to focus on education that reforms and strengthens those processes regulation existing developments and especially approvals of new developments in a region. This emphasizes, then, a key role for governments, whether municipal/local, state/provincial, national, or international authorities, that provide approvals, licenses/permits, monitoring, and regulatory enforcement. A second priority action area of UNESCO, namely the need for advancing policy, takes center stage as it is governmental policies that regulate these developments. According to UNESCO: “Policy-makers have a special responsibility in bringing about the massive global transformation needed to engender sustainable development today. They are instrumental in creating the enabling environment for the successful scaling up of ESD in education institutions, communities and other settings where learning takes place” (UNESCO., 2021). Again, however, given the labyrinth of policies and regulations of multiple levels of government impacting a region, where is an RCE to start in its educational role with policy makers and how can it be effective? Since its acknowledgment in 2007, RCE Saskatchewan, an RCE in western Canada, has engaged in strategic correspondence with various levels of government related to a range of development approvals in areas such as forestry, agriculture, mining, road construction, and energy. Each letter the RCE has directed to a particular government ministry in relation to a proposed development or policy serves as its own case study having responses from specific levels of government and both short and longer term impacts. As this correspondence has seemingly had, in most cases, surprising effectiveness in altering development proposals for greater sustainability the paper will explore key dimensions of these letters. This analysis can, in turn, serve as a practical guide to RCEs pursuing a “whole-region” transformative approach for sustainable development. Further, this paper will explore how a scholarly focus on letter writing reaffirms an older part of scholarship within universities associated with the earlier rise of the humanities. This has important implications for the role of the ESD scholar in targetted letter writing and the evaluation of this form of scholarship within universities. Finally, some conceptual limitations of this analysis will also be discussed.

2. Context

In order to situate the strategic value of the letter writing RCE Saskatchewan has engaged in, it is first important to understand the policy context of development more generally as it relates to all RCEs. RCEs need to understand the systems governing existing and new developments in their territory if they are to engage in this whole-region approach. For newly acknowledged and even well-established RCEs, the development context in one's own region will be substantially unknown and, hence, the context for RCE action is characterized by uncertainty (see Scoones and Stirling, 2020, Ch. 1). While one could explore general theories of policies related to development, actual development is always situated. With any new development specific resources (or capitals) are proposed to be mobilized in specific contexts using industrial or other processes, for specific goals or ends (e.g., the production of a particular good or service). This localization of development strategies and regulatory approvals and oversight makes strategic educational interventions for a whole-region approach by RCEs challenging. How does development happen here? What are the existing policies and regulations that apply and under whose jurisdiction(s) does a particular development proposal fall? RCEs must gather knowledge of codified policies and jurisdictional responsibilities that apply to different kinds of situated development.

A further uncertainty relates to how (and whether) development policies are implemented in specific cases. The extent of regulatory implementation may be affected by conflicts in policy directions within a government agency, personal conflicts of interest, or a lack of resources for evaluation, monitoring, and/or enforcement. This suggests RCEs must also acquire tacit, non-codified knowledge (the “know-who” and “know-how”) about proposed developments and those bodies providing regulatory approval and oversight. This “know-who” can include familiarity with specific individuals involved along with their knowledge, values, interests, and motives. This “know-how” can include production technologies and market strategies of particular firms, local land uses by landowners, or even how firms and individuals are subcontracted in a development process (e.g., consultants contracted to write environmental impact assessments for resource companies or farmers renting land from out-of-province landowners). The latter might, in turn, have a quite different set of motives and interests, especially as it relates to sustainable development.

To be effective, then, an RCE must somehow acquire localized knowledge, both codified and non-codified, about these development processes. Specific interventions that can bring to light these policies, individual decision makers, and organizational roles, can, in turn, enable subsequent educational strategies within these localized contexts that bring about needed change. Modified educational strategies can also be applied to developments within the same sector (such as mining, or agriculture) or those regulated by the same legislation or government department.

This process of corresponding can be understood in terms of a traditional program logic model. The collaborative letter writing itself by the RCE is the activity with the letter generated as the output. The immediate outcome is normally a formal acknowledgment by the government department of the letter's receipt. There is then a more formal governmental reply (an intermediate outcome) to the queries in the original RCE letter along with an outline of the current state of deliberations within the department and the process that will be followed in reaching a final decision. Finally the RCE receives notification of whatever changes was finally adopted along with a rationale (a long-term outcome). The government decision will then impact the community (for better or worse) and frequently the government will set out some impact indicators that will be reported on at a later date so it, in turn, can assess the success of its decision. These measures are often included in the final notification of decision so there is public transparency as to what follow-up will occur.

Formal correspondence to specific orders of government about particular development proposals is an important vehicle for RCEs to acquire this knowledge. Letter writing and other submissions reflect a traditional method for engaging governments built on their core functions and ways of governing. Just as ancient rulers were petitioned by their subjects to undertake particular actions, so too do citizens in modern democracies have the right to make formal requests of government. This is reflected in how such correspondence is treated. In the case of RCE Saskatchewan, letters received were formally acknowledged by government departments with, typically, numbered departmental responses made available on the public record. Ancient monarchs also employed various advisors within their court to aid in decision making which nowadays is reflected not only in governments with specialized research offices but also in governments commissions to which scholars might be appointed and other public processes within which academic experts can participate. As RCEs are scholarly networks, RCE letters fulfill this advisorial role (and just like ancient rulers, political decision makers and civil servants can always choose to follow or not follow particular advice). Modern democracies also require that policies have a rationale that is articulated and justifiable in the public (vs. private) interest. This legal requirement of public policy provides a structured receptivity of government for RCE submissions that advance sustainable development (which articulates a long-term citizen interest). Lastly, a core value of government is maintaining order. This involves establishing due processes for contentious matters to be considered, avenues for expert and public input toward such deliberations, and mechanisms for impartial settlement of disputes. Proposed developments of significance frequently are contentious given the resources involved and the competing interests of diverse stakeholders and, hence, fall in this category. Importantly, the sustainable development perspective advanced by RCEs reinforces an interest in maintaining order and stability over the long term.

2.1. A case studies approach

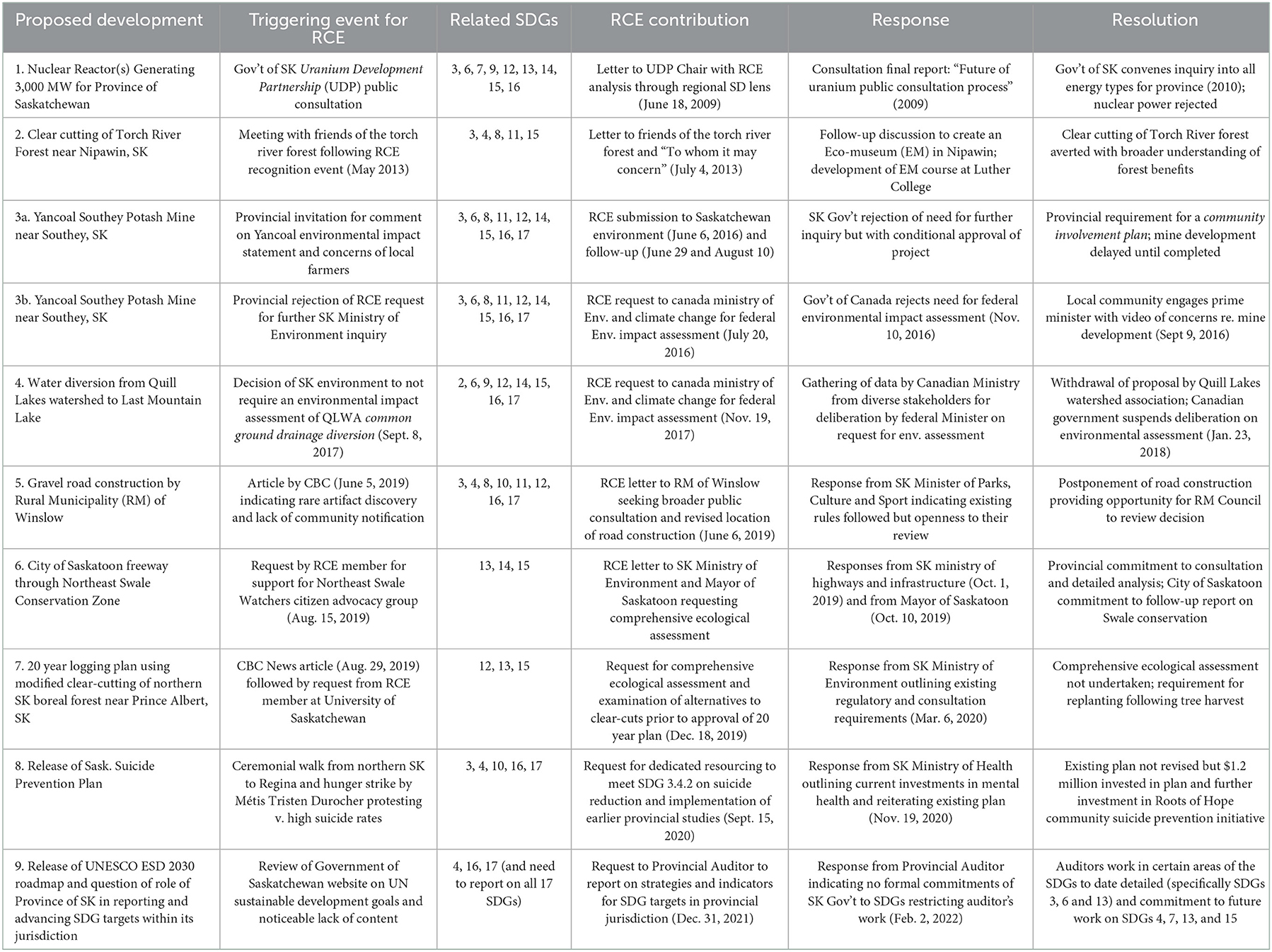

Since its acknowledgment as an RCE by the UN University in 2007, RCE Saskatchewan has intentionally made submissions to various levels of government on major development proposals. Table 1 sets out nine different developments listed chronologically on which the RCE has made submissions. These include one related to energy (#1), two on forestry (#2, #7), one on mining (#3 a, b), one on agricultural water diversion (#4), two on road construction (#5, #6), one on suicide prevention (#8), and one on SDG reporting by government (#9) (Table 1, col. 1). Governments necessarily have been involved with these developments given their legal obligation to review private development proposals within their own jurisdictional responsibilities. Actions undertaken include requiring specialist studies, preparing and/or reviewing environmental impact assessments, and public hearings. Analogous to government, RCE Saskatchewan has been triggered to act based on its own educational mandate as it relates to the proposed developments. The RCE has also responded to direct petitioning by members of the RCE or the broader community (these “triggers” are found in Table 1, col. 2). These members may include formal organizational partners of the RCE (such as universities, NGOs, or community associations), the RCE's own working groups and flagship projects, or individual RCE members that bring a matter to the attention of the RCE. Eact, in turn, may act on behalf of other groups or individuals who have heard about the RCE's work and seek its help but are not formal RCE members. That RCE Saskatchewan is often structurally mandated to respond is tied to the substantive impact of all the developments on the SDGs (Table 1, col. 3 shows all of the developments impacting at least 3 SDGs if not more). The table then documents the nature of the RCE submission (normally a letter; see col. 4), followed by the formal governmental response (col. 5), and the final resolution of the situation (col. 6).

Each RCE letter in Table 1, along with what has occasioned the letter and its resulting governmental responses and impacts, can be seen as its own distinct case study. Methodologically, the paper employs a qualitative, case studies approach to draw out key features of the letters themselves along with features of the resulting processes of which they were a part and helped shaped. Best case examples are then highlighted throughout the remaining paper to illustrate the dynamics of specific RCE interventions. A comparison of individual cases has, in turn, allowed common elements to emerge both in the letters themselves but also the dynamics at play, to enable strategic reflection on how this letter writing strategy can be employed by RCEs. This qualitative method produces a kind of “grounded theory” vs. the “general theory” generated by quantitative scientific methods (see Strauss and Corbin, 1994; Charmaz, 2004). This means the results will have more direct relevance to the situation in Saskatchewan as well as other RCEs that share its structural features, mandates, resources. Similarly the findings will have more relevance to the kinds of development proposals found in Saskatchewan, many of which involve extractive industries (such as mining) and primary production (such as agriculture), rather than other types of development (such as value-added manufacturing or ICT). Some of the limits related to generalizability of the findings are discussed in the concluding section including the inability to determine direct causal linkages between specific RCE letters and resulting outcomes. Ultimately the case studies also serve as a kind of storytelling that hopefully can both motivate and inspire action by those seeking to advance sustainable development within their regions.

3. Key elements of RCE correspondence

This collection of nine case studies have been used to identify common features shared by many (if not all) of the cases and deemed as potentially having been important to their strategic effectiveness. Here the strategic effectiveness of a letter is understood in terms of (1) whether some (or all) of the objectives stated in a letter's request have been achieved and (2) whether the letter can reasonably be seen to have contributed to the achievement (that is, did the governing authority likely act differently than it otherwise would have based on the formal requests made in the correspondence). With each of the features discussed, specific case studies are highlighted that seem to best illustrate the element under discussion. The elements include: (1) issue identification and framing, (2) background on RCE SK and global RCE network, (3) acknowledgment of government authority and constructive critique, (4) highlighting other sustainability options, (5) RCE recommendations for action, and (6) inclusion of additional appropriate stakeholders. Each will be discussed in turn.

3.1. Issue identification and framing

Any letter to government would reasonably begin by identifying the issue occasioning the correspondence. RCE SK has typically mentioned some version of the “triggering events” listed in Table 1, col. 2 in its letters (whether responding to a formal invitation for public input, expressions of expert or public concern about a development proposal in the media, or the decision of one government enabling another level of government to act). However, the RCE also indicates it is acting according to its own regional mandate in service to the particular government. To the extent both major cities (Regina and Saskatoon), the province of Saskatchewan, and the Government of Canada participated in the formation of RCE Saskatchewan this underlies the credibility of this service role to government. The citizen service role of the RCE's higher education partners (that include the University of Saskatchewan, University of Regina, and Saskatchewan Polytechnic) also affirm this.

While the RCE is also often responding to development proposals in the face of a negative community or grassroots reaction, it often reframes the situation as a positive educational opportunity. A good example of this positive reframing of a development dispute is a letter sent by RCE Saskatchewan to the Rural Municipality (RM) of Winslow following the discovery of rare artifacts (up to 10,000 years old) in a section of proposed gravel road construction by the RM (Warick, 2019a). While the site was professionally excavated according to the terms of the Saskatchewan Heritage Property Act, the Act did not require notification of Indigenous groups, the local community, or other provincial bodies (only in the event human remains were discovered would there be such notification; Saskatchewan Parks, 2019). The community was only made aware of the find by a local farmer who alerted First Nations in the area (Warick, 2019a). As the Province's Heritage Conservation Branch had already allowed the project to proceed, the RCE communicated directly with the RM of Winslow, specifically its Reeve and Councilors. The letter began highlighting the RCE's excitement about the artifacts discovery and its significance as a part of the Province's tangible cultural heritage; it affirmed the site's potential for sustainable development: the educational value for local schools and researchers, social and cultural value for local residents, and economic value from tourism (RCE Saskatchewan, 2019b: p. 1–2). The letter also addressed the connection between culture and development citing UNESCO: “[c]ulture contributes to poverty reduction and paves the way for a human-centered, inclusive and equitable development” (RCE Saskatchewan, 2019b: p. 2). This positive reframing of the find as a resource for the community helped highlight a wider vision of what constitutes development over the more traditional development reflected in the road construction. The RM chose to halt the road construction shortly thereafter for further consultation (Warick, 2019b).

3.2. Background on RCE SK and global RCE network

A key component of all letters authored by the RCE has been to provide adequate background on the structure and purpose of RCE Saskatchewan and the global RCE network. The following is a sample paragraph from a letter requesting further provincial government action on suicide prevention (Saskatchewan has the highest rate of suicide of any province in Canada, especially among Indigenous youth; RCE Saskatchewan, 2020: p. 2; see also Saskatchewan Health., 2020, for the Government of Saskatchewan's reply):

As background, RCE Saskatchewan is a Regional Center of Expertise (RCE) on Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) acknowledged by the UN University in 2007. Our RCE brings together scholars and community practitioners dedicated to researching and advancing ESD from Saskatchewan's Higher Education and other local institutions. These activities are the result of our dedicated volunteer base. This mobilization of regions by the UN University was initially in support of the UN Decade on Education for Sustainable Development (2005–2014) and the UNESCO Global Action Programme on ESD (2015–2019). We now see education for sustainable development as essential in achieving the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) meant to guide the global development agenda until 2030. ESD includes, but is not restricted to, Goal 4 on education. As one of over 175 RCEs now acknowledged globally, RCE Saskatchewan is excited about any opportunities for advancing education within our communities that reduces suicide rates and increases mental health and general wellbeing in the province but especially among the most vulnerable citizens of our society (RCE Saskatchewan, 2020).

It is worth noting the importance of key elements of this RCE background as those who work with the RCE are often surprised that it receives specific (vs. generic) replies from governmental authorities in response to RCEs correspondence. First, the RCE is working under the auspices of the UN University in service to the United Nations. The Government of Canada has made a formal commitment to the UN Sustainable Development Goals so the RCE is affirming a shared governmental commitment through the UN. Secondly, within a Canadian context, education is a provincial responsibility. By citing the RCE's focus on education and formal role in supporting UNESCO this directly connects to the jurisdictional responsibilities of the Province of Saskatchewan. Third, the RCE is acting as an autonomous Higher Education Institution, an autonomy shared with the United Nations University and its Higher Education partners whose members enjoy academic freedom. Further, the scholarly work of the RCE also incorporates community expertise including local sustainability practitioners. As it is universities that train experts who put together or evaluate development proposals, the RCE serves as an expert authority on regional sustainable development. This means that its input is taken seriously by professional organizations and governments regulating professions and evaluating their proposals. The RCE is also a qualified expert in legal settings; should the issue in question come before the courts the documentation of the RCE can play a substantive role in a legal ruling. Fourth, in the case of RCE Saskatchewan, the RCE is purely voluntary with a structural commitment to advancing education for sustainable development (ESD). As ESD reflects the long-term interests of citizens it carries both moral and legal weight for government officials and political leaders as it tends to align with citizen normative expectations and state legal accountabilities. Lastly, the RCE has both a broad regional and global connectivity. This means that political reputations are potentially affected by governmental responses, as is the global reputation of Saskatchewan and Canada.

3.3. Acknowledgment of government authority and constructive critique

In its correspondence with government the RCE has sought to ensure that the dignity of the office with which it is corresponding is maintained. This is done, in part, by recognizing the authority of a given department to act with respect to a particular matter and employ its own best judgment in relation to all information it receives (including that from the RCE). The RCE strives, on the one hand, for a formal, neutral tone so as not to distract from the evidence and lines of argument it provides, in line with the RCE's educational mandate. Where praise for existing government actions is warranted, this is included. So, for example, in 2021, RCE Saskatchewan wrote a letter to the Provincial Auditor of Saskatchewan seeking the Auditor's assistance in having the province report on those UN SDG targets falling within provincial jurisdiction along with supporting strategies (RCE Saskatchewan, 2021; Provincial Auditor of Saskatchewan, 2022). While the letter was sent due to a noticeable absence of references to sustainable development and the UN SDGs on the provincial government website, the RCE did note positive exceptions including reference to the SDGs as part of the Province's International Education Strategy (RCE Saskatchewan, 2021: p. 2).

The RCE also tries to strike a positive tone, seeking to be upbeat about the opportunities a more sustainable path of development can provide. This positivity mirrors the ancient letter writing strategy of the Christian missionary Paul of Tarsus, who in his epistles to various churches begins with a positive greetings, praise, and thanks and ends on similar words of encouragement. These words bookend often quite difficult content for the community he is addressing (see, for example, Romans 1: 7–15; 16: 19–27). This positive approach is supplemented, more generally, by a positive relationship cultivated between the RCE and government through routinely celebrating a range of ESD projects, including municipal, provincial, and federal government supported initiatives through its annual Education for Sustainable Development Recognition Event (RCE Saskatchewan, 2022).

Alongside this acknowledgment of authority and good practice to date, the RCE also sets out a constructive critique of the proposed development in terms of: (1) standard principles of good governance, (2) general principles of sustainable development, and (3) relevant UN Sustainable development goals and other UN commitments. Each will be examine in turn.

3.3.1. Critique using standard principles of good governance

A good example of a critique of a development process using standard principles of good governance is found in a submission by RCE Saskatchewan to its Uranium Development Partnership (UDP) public consultation in 2009 (RCE Saskatchewan, 2009; Perrins, 2009). In that year the Government of Saskatchewan was considering the development of a 3,000 MW nuclear reactor for the province (Uranium Development Partnership., 2009). At the time such a reactor was too large for Saskatchewan's needs, especially if it was to be only part of a mix of energy types (the province had a generating capacity of 3,641 MW). The RCE's key criticism of the UDP study, however, was the process that had been used, specifically the composition and mandate of the UDP Committee that had prepared the report. The RCE noted the lack of diversity of the committee including a lack of women and lack of expertise in the areas of health and the environment (Uranium Development Partnership., 2009). Further, the committee's composition appeared not to be impartial but rather as having a likely vested interest in securing a nuclear reactor creating a perceived conflict of interest and consensus bias. Lastly, the committee's focus on nuclear power to the exclusion of other energy types prevented useful comparisons related to the opportunity costs associated with a nuclear reactor. The RCE recommended an independent review panel be struck exploring all energy options for the province; this subsequently occurred and the RCE was invited to present (RCE Saskatchewan, 2010).

A second example where RCE Saskatchewan's critique was tied to appropriate governance was in response to the proposed construction of a water diversion channel from the Quill Lakes Watershed (a closed watershed that drains into salt water lakes) into the north end of Last Mountain Lake. The latter is the site of the Last Mountain Lake Migratory Bird Sanctuary; the sanctuary was legally set aside for this purpose in 1887 and is one of the oldest in North America (Canada Ministry of Environment Climate Change., 2022). Due to several years of high levels of precipitation and extensive illegal/non-permitted drainage by upstream farmers in the Quill Lakes watershed (see RCE Saskatchewan, 2017a: p. 6), the Quill Lakes had risen extensively thereby flooding land of farmers adjacent to the Quill Lakes. The RCE requested a federal environmental assessment of the project in part due to a number of ecological concerns including issues with diverting water that had a much higher salt content and total count of total dissolved solids (TDS) into Last Mountain Lake (RCE Saskatchewan, 2017a: p. 2; RCE Saskatchewan, 2017b). However, despite these ecological concerns, a primary set of governance issues were raised related to the Quill Lakes Watershed Association (QLWA), the project's proponent, and the Government of Saskatchewan. The QLWA is meant to manage water within its own watershed and, as such, is structurally governed by representatives within that watershed. The proposal, however, would have diverted water into a different watershed potentially imposing substantial harms on those without representation in its governance structure and beyond its jurisdictional mandate (RCE Saskatchewan, 2017a: p. 3–4). If the project were approved, the RCE noted there would also be an ongoing conflict of interest for the QLWA in monitoring and controlling the water flow given the QLWA's structural interest in diverting water into the neighboring watershed (RCE Saskatchewan, 2017a: p. 4). A second concern, however, was with the framing of the project in relation to its overall purpose, namely a lowering the Quill Lakes by 0.6 meters (RCE Saskatchewan, 2017a). The RCE noted that the proposed water diversion of 7 million m3/year was well below what was needed to actually achieve this goal; instead the diversion amount had presumably been chosen to be beneath the 10 million m3/year that would have triggered a federal environmental assessment (RCE Saskatchewan, 2017a: p. 4–5; RCE Saskatchewan, 2017b: p. 2). In light of this low volume, the negligible contribution of the project toward its stated goal of flood mitigation was a further reason from a basic governance perspective to reject the proposal (RCE Saskatchewan, 2017a: p. 5).

A second major governance issue, however, was the Government of Saskatchewan's rejection of the need for a provincial environment impact assessment (EIA) of the QLWA proposal on September 8, 2017 (Saskatchewan Environment., 2017). This determination was based, according to the provincial ministry, on the project's not meeting any of 6 criteria specified under the Saskatchewan Environmental Assessment Act, sec. 2(d) needed to trigger an EIA (SK Environment, 2017, “Reasons for Determination” 1–3). Based on the RCE's own analysis of the three criteria, 3 of the criteria were found to directly apply. These included the use (and likely degradation) of a provincial resource (in this case surface water), documented public concern about the proposal, and the project's potential for substantial environmental impacts (RCE Saskatchewan, 2017a: p. 2–3). As such, the provincial government had, on the surface, made an improper determination of the legal need for a provincial EIA. Good governance also requires considering the opportunity cost of a particular action relative to other possible courses of action (those that might cost less and potentially have a greater impact and hence be better solutions). The RCE noted that a provincial environmental assessment would have required the drainage proposal be compared against all other options (RCE Saskatchewan, 2017a: p. 4, note 10). Other options might include closing of illegal drains and wetland restoration (RCE Saskatchewan, 2017b: p. 3–4). Importantly, the lack of an EIA meant the inability of the local communities affected (including Indigenous/First Nations communities), the academic community nor other appropriate experts a formal mechanism for providing input (RCE Saskatchewan, 2017a: p. 7). In the end the QLWA withdrew its project application in January of 2018 so that the Government of Canada's Environmental Assessment Agency (CEAA) no longer had to decide whether an environmental assessment was needed (Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency, 2018).

3.3.2. Critique using general principles of sustainable development

A second avenue of constructive critique by RCE SK of development proposals has involved highlighting the additional expectations that a sustainable development approach requires that are not part of traditional development approval processes. Rather than assuming a necessary tradeoff between economic development and the natural environment in development proposals, instead the long-term, multi-generational focus of sustainability should select for developments that strengthen the capabilities of individuals and their communities, including both human and non-human species, which entails building up the underlying resources on which these depend. An increasing disconnect between communities that have expectations for sustainable development and outdated development approval processes means growing tensions with communities that, in turn, delay or prevent developments altogether due to a lack of social license. A particular case illustrates this point. In 2016, Yancoal Canada Resources Co. Ltd., a state owned Chinese enterprise, proposed to develop a potash mine (used for fertilizer) in rural Saskatchewan near the town of Southey (Yancoal Golder Associates., 2016). In responding to the Government of Saskatchewan's public call for feedback on the potash mine's Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), RCE Saskatchewan noted key areas where the EIS was inadequate due to a process that failed to incorporate current scholarly research on sustainable development (coupled with even diminished regulatory standards with the legal loss of federal government oversight for such large scale projects; RCE Saskatchewan, 2016a: p. 2). This lack of sustainable development dimensions included the neglect of the precautionary principle, particularly given the large volume of fresh water that would be used at mine's full production; this volume of water amounted to 1,450 m3/h taken from the City of Regina's water supply at Buffalo Pound, which, in turn, is located in a semi-arid region with substantive projected impacts of climate change (RCE Saskatchewan, 2016a: p. 2; Petry et al., 2018: p. 25). A further sustainability dimension of the EIS that was missing was the lack of analysis of the social impacts of the proposed mine on the local farming community, including potential loss of social and cultural capital, especially in light of the divisions that had already occurred in the local community up to that point (RCE Saskatchewan, 2016a: p. 2–3). Given these and other lacks, the RCE recommended that the Minister of the Environment call an independent inquiry, a power available under the Saskatchewan Environmental Assessment Act, to remedy these deficiencies and to also include a socio-cultural impact study to understand the agricultural livelihoods being impacted (RCE Saskatchewan, 2016a: p. 3, 9). Initially the Ministry did not respond to the primary concerns raised by the RCE (Saskatchewan Environment., 2016a) but following further correspondence from RCE Saskatchewan, 2016b, the Ministry indicated it would not undertake such an inquiry (SK Environment 2016b). However, when it issued its conditional approval of the mine, it did stipulate the need for Yancoal to create a community involvement plan including establishing a community advisory committee—presumably to address some of these concerns about inadequate social license (Saskatchewan Environment., 2016c: 2, sec. 7). The RCE, however, cited reservations about the approval in a subsequent media release analyzing the decision, including concerns about the terms for the community involvement plan being designed by the mining company (RCE Saskatchewan, 2016d, p. 1–2, sec. 2). The remedy of a community involvement plan proved inadequate with continued tensions and delays that followed the initial approval (Petry et al., 2018); regrettably with a more rigorous environmental assessment process framed around sustainable development principles and an additional supplementary inquiry as recommended by the RCE these delays could potentially have been avoided.

3.3.3. Critique using relevant UN Sustainable Development Goals and other UN commitments

A third form of constructive critique employed by the RCE has involved appeals to specific UN SDGs and other UN commitments by the Government of Canada. Prior to the adoption of the 17 UN SDGs in 2015, RCE Saskatchewan framed its analysis in light of the local sustainable development issues that had been identified in putting together its formal application to the UN University. So in critiquing the Uranium Development Partnership proposal in 2009, RCE SK used its regional thematic areas of climate change, health and healthy lifestyles, farming and local food production, reconnecting to natural prairie ecosystems, supporting and bridging cultures for sustainable living, and sustainable infrastructure, along with one of its two cross-cutting themes of sustaining rural communities (RCE Saskatchewan, 2009: p. 6–15). The use of these themeatic areas grounded in local citizen realities helped create a compelling regional case for the RCE's recommendations to the UDP.

With the approval of the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015, the RCE shifted to referencing those SDGs relevant to the development issue at hand in framing its letters to different levels of government. In 2019, for example, an RCE member requested the RCE send a letter in support of the Northeast Swale, a sensitive ecological region that would be impacted by the construction of a freeway around the perimeter of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan's largest city. As both the City of Saskatoon and the Province of Saskatchewan were funding the initiative and involved in the planning, the RCE sent a request to both levels of government asking for a comprehensive ecological assessment of the impacts of the proposed route (RCE Saskatchewan, 2019c; Saskatchewan Environment., 2020). In support of this request, the RCE cited 3 specific UN SDGs, in this case goal 13 on climate action (given the role wetlands and grasslands play in carbon sequestration), goals 14 (life below water), and goal 15 (life below land) given the habitats for specific rare and endangered species found in the Northeast Swale; RCE Saskatchewan, 2019c: p. 2). A further example employing the UN SDGs, was the RCE's response to a 20 year forestry plan proposal seeking a modified clear-cutting of the boreal forest in Northern Saskatchewan near the city of Prince Albert (Latimer, 2019). A “modified” clear cut according to Saskatchewan Environment seeks “to emulate natural disturbances caused by severe wind or fire”; however, only 9% of trees are left within the area that is clear cut (Latimer, 2019). Viewing this clear-cutting approach as inadequate, RCE Saskatchewan specifically cited Goal 15, “Life on Land” and its commitment to sustainable forestry management practices (RCE Saskatchewan, 2019d: p. 1). The RCE also pointed out a false analogy between clear-cutting and forest fires citing the much greater loss of organic material in soils following logging vs. natural fires (RCE Saskatchewan, 2019d: p. 2). RCE Saskatchewan also cited the key role of Canada's boreal forests in addressing climate change (SDG 13) as well as the need to focus on responsible consumption and production (SDG 12). In the latter case, the RCE cited Natural Resources Canada and the diversity of non-timber products and services that a natural forest provides vs. one that is clear-cut—even if it is replanted (RCE Saskatchewan, 2019d: p. 2).

The RCE also takes the opportunity to cite relevant commitments Canada has made to various UN Conventions. In the case of the proposed highway construction through the Northeast Swale in Saskatoon, the RCE identified the UN World Heritage Convention Concerning the Protection of World Cultural and Natural Heritage, specifically article 5.4 where Canada is committed “to take appropriate, legal, scientific, technical, administrative and financial measures necessary for the identification, preservation, conservation, presentation and rehabilitation of this [cultural and natural] heritage” (RCE Saskatchewan, 2019c: p. 1–2). In the case of the proposed modified clear-cutting of the boreal forest near Prince Albert, the RCE cited Canada's commitment to the UN Decade for Biodiversity (which includes target 6 on sustainable forestry management) as well as Canada's own reporting to the UN on the Decade that emphasizes the major role Canada has to play in this regard due to its forest cover (RCE Saskatchewan, 2019d: p. 3).

3.4. Highlighting other sustainability options

In order to point out the opportunity costs associated with proposed developments, the RCE has frequently highlighted alternative sustainability options that might be pursued having lower resource costs and/or greater sustainability impacts. A good example of this strategy was an RCE letter composed in support of creating a living laboratory for ESD in the Torch River Forest located in the North East part of Saskatchewan near the town of Nipawin. This was in lieu of a proposed clear cutting of the forest. Following the RCEs ESD Recognition Event held in Nipawin on May 8, 2013, the RCE had a hastily called meeting with two concerned members of the Friends of the Torch River Forest (FTRF). Deeply concerned about a looming clear cut of this old growth provincial forest, they asked what the RCE might do. On July 3, the RCE met with FTRF and interested local stakeholders from the Nipawin Region with additional faculty from the city of Regina using a virtual connection. Drawing on the local knowledge and academic expertise gathered at the meeting, the RCE composed a letter addressed to the FTRF, local stakeholders, and “To Whom it May Concern” (RCE Saskatchewan, 2013). To show the opportunity cost of the clear cut (which would have provided only a one time economic benefit to one or a few companies with relatively low quality timber), the letter documented the loss of the existing economic uses of the forest as well its non-market livelihood benefits should the clear-cut proceed. These included the high value of annual mushrooms harvested and sold to Canadian restaurants, berry picking by local residents, the value of the forest as a recreational area for existing tourism (and future opportunities for eco-tourism), a rich cultural history based on the diversity of Indigenous peoples and early European settlement in the area, and the forest's role as a source of traditional medicinal plants and site of healing (RCE Saskatchewan, 2013: p. 1–2). The letter then highlighted the potential value of the forest as an “educational forest” or “teaching forest” noting opportunities for study of its distinctive biology and for improved forest management including alternative logging practices (RCE Saskatchewan, 2013). The proposed development model, specifically the creation of an Eco-museum in the area, could advance all of these additional benefits while preserving the many livelihood opportunities already offered by the forest. By documenting the existing and potential forms of sustainable development possible with the forest, the marginal economic benefits of a clear cut for a few logging companies, and the harms to the forest's many users, the opportunity costs of the logging became readily apparent and the clear cut did not proceed.

3.5. RCE recommendations for action

Where possible, the RCE sets out recommended courses of action based on feedback from local community members, sustainability practitioners, and academic input. These recommendations are important both to provide directions that are workable with those who are being affected by a given development (thereby acquiring social license from the community) as well as enabling formal deliberation by a government body in relation to the request. It also helps ensure a formal governmental reply to the RCE regarding the recommendation with supporting rationale (whether or not the specific request is being followed). In the case of the RCE's response to the proposed development of a nuclear reactor in 2009, 5 recommendations were presented, each following detailed analysis justifying the recommendation; many of these were subsequently enacted (RCE Saskatchewan, 2009). In the case of the proposed highway development through the Northeast Swale conservation area in the city of Saskatoon, a specific recommendation was made for a comprehensive ecological assessment of the impacts of the development (RCE Saskatchewan, 2019c). In this case the Province of Saskatchewan committed to extensive consultation (naming specific groups to be consulted) along with setting out when a detailed analysis of the ecological impacts would take place (Saskatchewan Highways Infrastructure., 2019). The City of Saskatoon in its own letter also detailed its efforts for stewardship of the Swale including the commitment for the City administration to do a follow-up report on the Northeast Swale's conservation (City of Saskatoon, 2019).

In recommending alternative courses of action, the RCE also offers to provide assistance or educational supports based on its ability to draw upon the expertise of its individual members and partner organizations as well as the global RCE community. For example, in the case of the Torch River Forest, the RCE indicated the potential to make the community's progress in creating a living laboratory for sustainability visible at the next RCE Saskatchewan ESD Recognition Event the following year as well as presenting on its progress to the other 116 RCEs in 2013 at the UN University's 8th Global RCE Conference in Nairobi, Kenya (RCE Saskatchewan, 2013: p. 2).

3.6. Inclusion of additional appropriate stakeholders

While RCE letters are directed at a particular level of government for action, the RCE is always very mindful and deliberate in what individuals and organizations are cc'd on the correspondence. One reason is that multiple jurisdictions might have authority in relation to how a development project proceeds. Keeping these other jurisdictions included in correspondence from the start can be useful, especially if a later appeal is made to a different jurisdiction for action. So, for example, in the case of Yancoal Southey Potash Mine proposal, the Canadian Minister of Environment and Climate Change as well a Member of the Canadian Parliament from the Saskatchewan region who was sitting in the governing party at the time were included on the correspondence (RCE Saskatchewan, 2016a: p. 3). When the Government of Saskatchewan indicated it would not be proceeding with an independent inquiry to supplement its initial environmental assessment (Saskatchewan Environment., 2016b), RCE SK requested a cumulative environmental assessment by done by the Government of Canada (RCE Saskatchewan, 2016c). In this case the federal ministry was already well aware of the issues at stake. While it declined to conduct its own assessment, citing, in part, the province's having already conducted its own study (Canada Ministry of Environment Climate Change., 2016) this reason for the decline was later important in subsequent interactions with the federal ministry. When the Government of Saskatchewan decided in 2017 that an environmental assessment was not needed for a water diversion proposal from the Quill Lakes basin into Last Mountain Lake (Saskatchewan Environment., 2017), RCE Saskatchewan made use of this fact to argue a federal environmental assessment was warranted (RCE Saskatchewan, 2017a).

In cc'ing frequently a large number of individuals and organizations, the RCE is able to clarify and broaden who it views as stakeholders to a development that might otherwise not be included. So, for example, in most correspondence the RCE has included its own regional partners and members (given its regional accountability) as well as the United Nations University in Japan in light of the RCE network operating under the auspices of the UNU's Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability (United Nations University, 2022). In addition, the RCEs are a global learning space for sustainable development so the RCE also includes the Regional Advisor for RCEs in the Americas as well as indicating that it will keep other RCEs informed of developments in Saskatchewan (whether through reports at annual Americas meetings of RCEs or Global RCE Conferences). As the RCE serves citizens in general within the region, it will normally include both government and opposition members of the legislative assembly (i.e., the government ministers of relevant ministries as well as the opposition critics associated with the ministry) as well as related federal ministries. In addition, the intentional inclusion of other provincial or regional organizations helps make them aware of issues that fall within their organizational mandates (even if, to date, they may not have considered it as such). So, for example, in the case of the artifact discovery of the RM of Winslow, the RCE included various municipal, Indigenous, and cultural organizations, specifically the Saskatchewan Association of Rural Municipalities, the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations, and Multi-Faith Saskatchewan (RCE Saskatchewan, 2019b).

This breadth of inclusion is appropriate from a governance perspective where multiple parties have direct or indirect responsibilities related to a particular development or managing and influencing that kind of development. However, as importantly, it reflects an acknowledgment by an RCE of the significant unknowns in moving to more sustainable paths. Who has jurisdiction? In the case of the RM of Winslow, for example, a provincial government reply was received by the RCE from the Ministry of Parks, Culture, and Sport rather than Ministry of Government Relations based on their interdepartmental discussions (of which the RCE was notified on June 11, 2019). There are also other unknowns. What legislation and regulations might need to be modified or might a new authority need to be created? What interests and resources might proponents of specific kinds of development (whether mining, agricultural developments, or forestry) have for advancing more sustainable development including ESD within their own organizations? What organizations might be able to use their various forms of influence (such as public and private advocacy) to advance change? The breadth of inclusion of those cc'd on a letter also creates a platform for conversation among organizations that may not have been in communication due to differences in geographic scale, organizational silos, or past inter-organizational tensions. In this case, not only do recipients of communications frequently cc other organizations initially included in their replies, but the resulting correspondence is usefully framed around the concept of sustainable development and relevant sustainable development goals. As formal conversations evolve into future meetings, scholarly panels, or community events an avenue is created for a broadening of invitations to the stakeholders initially identified.

A final reason for the breadth of inclusion of organizational stakeholders cc'd on correspondence is the role they play as gatekeepers to enabling a broad public awareness of substantial development initiatives whose approval will have long-term impacts, for better or worse, on regional sustainability. In many cases, the RCE has been contacted precisely because developments have been perceived to be undertaken without effective public consultation (even though this is frequently a mandatory requirement). In the case of the proposed modified clear-cutting of the boreal forest near Prince Albert, a member of the Fish Lake Métis sought to have a meeting with the provincial government on the proposal only to find that the meeting would not be public; nor were further public meetings scheduled by the government (Latimer, 2019). A similar concern was raised about earlier consultations on the logging proposal; rather than being arranged by the Province these were arranged by the proponent of the logging development itself and were noted for their poor attendance (Latimer, 2019). As mentioned earlier, in the case of the proposed water diversion from the Quill Lakes watershed to Last Mountain Lake, the choice not to have an environmental assessment eliminated a key opportunity for public input (SK Environment, 2017).

A key issue here is how public consultation is viewed in the development process. Developers often view consultation as simply a hurdle to be overcome as do government's that see economic growth from new developments as the primary vehicle to livelihood improvements and quality of life (see Saskatchewan's Growth Plan: 2020-2030; Government of Saskatchewan, 2019). Rather than a hurdle or barrier, however, public participation in the approval of specific projects plays a vital role in education for sustainable development. Transforming the perception of these consultations from an obstacle to an asset (namely as an opportunity to acquire invaluable local expertise, scholarly and other organizational input) is vital to ensuring locally appropriate, sustainable development. This also avoids a “cookie cutter,” one-size-fits-all model of development by large economic players. RCE SK interventions in these public processes can be key to turning them from routine procedures into learning spaces, especially where local expertise is validated by an RCE that might otherwise be dismissed.

4. Discussion

4.1. Efficiency and effectiveness of RCE letter writing

An RCE's letter writing in response to proposed development initiatives deemed unsustainable or suboptimal within its region might be viewed as overly reactive. However, there are a number of reasons why such a strategy is both efficient and effective. It should be initially noted that in some ways it is an ancient strategy, mirroring the method of the ancient philosopher Socrates who always began his reflection by examining the merits of the ideas put forward by others rather than his own (see Plato, 1999). Here the RCE is also not putting forward its own sustainable development proposal but rather examining the merits of a development proposal put forward by another in its region. This merit is assessed based on formal academic expertise supplemented by the input of community members while employing the normative lens of sustainable development to which the RCE is committed. In terms of resource efficiency, the RCE feeds into already existing government processes that accompany new developments, whether it be a public hearing or consultation, governmental study, or commentary on an environmental assessment. In this case formal mechanisms are already in place to gather and assess the input received without an RCE having to set up its own hearings or methods for data gathering and evaluation. From an educational perspective this approach is also likely to be more effective since one already has the ear of a government needing to decide upon a particular proposal. Similarly, when a local community has mobilized to seek out an RCE to intervene, there is at least part of the local community wanting and ready to learn about possible, more sustainable alternatives to the development (whether by modifying an existing proposal or seeking alternative forms of development altogether). In this case the proposed development that is deemed to be unsustainable is like a grain of sand or other irritant around which a mollusk develops a pearl. An RCE's response to a local community's development concerns also allows an immediate avenue for identification of local expertise related to the issue at hand or, at least, local connections to relevant sustainability experts and practitioners. These would otherwise be difficult to find.

The reactive process of an RCE to write letters in response to notably unsustainable development processes is also efficient in terms of policy reform. It is not easy for most RCEs to be aware of the wide range of government development policies that might apply to particular developments within an RCE region. As mentioned earlier, such development policies are frequently opaque or applied in unusual ways with peculiar interpretations. However, these development processes are processes that already exist and are a form of social capital that govern the breadth of development types in one's region. Analogous to ESD efforts that seek to embed sustainable development into existing educational processes in schools (rather than adding on separate sustainability courses and programs), it is more efficient to reform existing development approval processes rather than adding new development streams exclusively for developments deemed sustainable. The basic strategy here, however, is to use an unsustainable project proposal as a basis for reform of existing policies. Where existing policies allow for the approval of projects with high opportunity costs that are not sustainable against relevant criteria (including the SDGs) this shows existing development policies are problematic and needing revisions. Otherwise the given project would not have been approved.

An RCE's documenting the failure of an existing development policy and approval process is normally sufficient to bring about needed reforms. Governments themselves can work out how they need to amend their policies to prevent such happenings in the future in the same way that proponents of unsustainable developments can propose more sustainable projects in the future without the help of an RCE. Should the RCE be invited, it can always participate in amending legislation or helping revise project applications. However, the RCE does not need to spend excessive time lobbying for particular policy changes but merely documents how specific cases that are being approved under current policies fail to meet standards for sustainable development.

This is not to say that the knowledge gained of policies governing existing developments is not of benefit to an RCE. As an RCE engages iteratively with specific economic and other sectors it gains further expertise and can more effectively and efficiently respond to specific issues as they arise. So, for example, in 2019, the Smith Creek Watershed Association threatened to expropriate land owned by a local farmer to facilitate the private drainage interests of upstream agricultural producers. Having already explored substantial governance and other structural issues with watershed associations in its previous experience with the Quill Lakes Watershed Association, the RCE was rapidly able to draft a letter of support for the farm couple (RCE Saskatchewan, 2019a). It was reported shortly thereafter that an agreement was being reached between the two parties (Briere, 2019). As RCE Saskatchewan is an association of volunteers the knowledge needed to draft such letters is not tied to specific employees but rather can be obtained by following up with those who have participated in the past. Repeated engagement with a single sector by an RCE can help illustrate the structural flaws in existing regulatory bodies. These could include embedded conflicts of interest, too narrow mandates, lack of public or long-term sustainability objectives, inadequate monitoring or enforcement, the need for broadened representation and/or expertise, or the need for additional resources to carry out legislated responsibilities, among others. The case for reform of these of bodies (whether through education of existing members, new membership, and/or legislative changes) is substantially enhanced by RCE documentation of repeated problematic cases as well as citing support by other bodies. So, for example, in the case of the Smith Creek Watershed Association the RCE was able to cite substantial work from a 2018 report of the Provincial Auditor critiquing limited provincial policies around water quality and wetland retention that had enabled excessive drainage (RCE Saskatchewan, 2019a: p. 2).

4.2. Direction of appeals between levels of government

It might be thought that jurisdictional appeals would proceed geographically from smaller to larger scales (e.g., municipal governments to state/provincial governments to national governments). The RCE has in specific instances appealed cases from the provincial government to the federal government when provincial responses have been inadequate (see, for example, RCE Saskatchewan, 2016c, 2017a). However, as frequently, RCE SK appeals have moved in the opposite direction, moving from a provincial jurisdiction to the municipal level. In the Yancoal potash mine case, for example, following the province's approval of the project, the Government of Saskatchewan made it clear that the project would not proceed without a satisfactory Development Agreement being negotiated between the local rural municipality (RM) of Longlaketon and the mining company (Petry et al., 2018: p. 36). In this case all of the voluntary research hours done by the local community and academics associated with the RCE (encapsulated in the RCEs correspondence with the Government of Saskatchewan and Government of Canada) put the RM in a more informed position for negotiation.

A further example of an appeal to a more local authority occurred In the case of the proposed gravel road development by the RM of Winslow in an area where artifacts had been found. The RCE chose to communicate directly with the RM since the provincial ministry of Parks, Culture and Sport had already decided that its own rules had been followed and the development could proceed (Warick, 2019a). In this case, however, the RCE cc'd the province's Ministry of Government Relations on the correspondence to the RM as municipal governments fall under this department of the provincial government (RCE Saskatchewan, 2019b: p. 4). It was felt that if ultimately rural municipalities became responsible for the final say in preserving artifact sites that the Ministry of Government Relations ought to be aware of the kinds of deliberations RMs are being asked to make and support them accordingly.

4.3. The role of public education and the media

It should be noted that unlike general public education that occurs through the media or educational activities open to the public (for example, organized by non-governmental organizations or companies in person or online), the RCE's correspondence is always intentionally directed to particular agents, both the immediate recipients and those that are cc'd on the correspondence. This is, in part, because the correspondence is normally directive with specific requests being made of particular organizations (see, for example, RCE Saskatchewan, 2009, 2016a,c) or meant to strengthen the stance of a community or individual agent in their calls for greater sustainability of a development proposal (e.g., RCE Saskatchewan, 2013, 2019a). However, because RCEs normally operate under high levels of regional transparency and communications to governments are typically on the public record, it has happened, on occasion that the media does report on particular RCE correspondence (as occurred in the case of the RM of Winslow; Warick, 2019c). In this case, the RCE's correspondence serves as a resource for the media that is engaged in standard investigative journalism using rules for access to information. While some RCE members may inform the media, it is not standard practice for the RCE to directly send correspondence to the media but only to those cc'd on the correspondence. On occasions that the RCE has contacted the media, it creates a formal media release formatted for this audience and sent to all relevant media outlets.

4.4. Innovation in university scholarship

It might be thought that letter writing as a form of scholarly output is something new. However, letter writing was central to the earlier rise of humanism in the academy in the 15th and 16th centuries. This is readily exemplified in the life and writings of the famous humanist Desiderius Erasmus who in 1,522 wrote his own manual on letter-writing entitled De Epistolis Conscribendis (Rummel and MacPhail, 2021). That the humanist focus on letter writing (an older mode of scholarship within the university) could be creatively re-purposed to advance sustainable development in government policies should perhaps not be a surprise. As I have documented elsewhere, the older parts of universities are central to the rise of newer forms of scholarship; the older language scholars were central to the development of humanism and older craft knowledge in the university was central to the design of the instrumentation needed for the rise of science (see Petry, 2012). Given the central role humanist scholars played in filling administrative offices of European towns and cities in their day as secretaries and state advisors (Petry, 2012: p. 120), we could also expect an organizational effectiveness of the tools of humanists, including letter writing, in reforming government regulatory processes for sustainable development.

The letters of RCE Saskatchewan parallel core humanist concerns. As trained humanists applied a skeptical eye in evaluating traditional biblical and classical texts in their day (to detect errors in translation and forgeries), so too does an RCE apply a critical eye to development proposals they are asked to evaluate. The humanist concern with ethical development is also reflected in the RCE evaluation of proposals against the normative lenses of sustainable development. Humanists also concerned themselves with accurately understanding historical contexts in which texts were written. RCE Saskatchewan in evaluating development proposals has also, on occasion, actively examined the history of those entities advancing a proposal, whether a nuclear power or mining company, to understand their track record with previous developments, whether positive or negative (see, for example, RCE Saskatchewan, 2009: p. 14; RCE Saskatchewan, 2016a: p. 8–9). The humanist concern with elegance in writing is equally valuable in constructing a persuasive letter for a government official or community group.

However, a substantive difference with humanist letter writing is the shift from the single author of a piece of correspondence by an independent scholar to the collective efforts of academics and community practitioners in crafting each RCE letter. Only this collective effort has enabled the breadth of knowledge needed to evaluate a particular development proposal and craft a useful set of recommendations. Similarly while the humanists aimed at enabling more accurate scholarly texts in the service of better theorizing in areas such as theology, philosophy, medicine, or law, or in the moral development of the individual, RCE letters are in the practical service of advancing more sustainable developments within their region for the benefit of entire communities. Finally, while humanist scholarship relied on the mastery of specific subject areas, such as mastery of the ancient languages of Greek, Hebrew, and Latin, and history, RCE letters necessarily draw upon a much broader interdisciplinary context determined by the development under consideration.

Given the scholarly effort to compose each RCE letter in Table 1, yet coupled with their substantive impacts, the question arises how such efforts should be evaluated in universities, especially in the context of education for sustainable development. While authoring a book was the traditional mark of a humanist scholar, since the rise of science, journal articles have been viewed as the primary scholarly output. However, a book or journal article, even on the topic of sustainable development, may have little immediate impact on a particular development proposal, especially within a given community where contextual knowledge is required. The substantial and positive impact of scholarly books and journals lies elsewhere. This raises the important question whether scholarly letter writing to governments for ESD should play a much greater role in the overall evaluation of a scholar's work (vs. seeing it merely as a kind of community service that in many universities has only a marginal value). Evaluating such letters as scholarly works in their own right could have profound impacts on the research focus of scholars. Perhaps there will come a day where a scholarly letter that preserves a forest or a wetland in the long-term public interest has as much scholarly worth as an empirical study that modifies an important theory within a discipline.

5. Acknowledgment of conceptual constraints and concluding reflections

This paper has explored the role of strategic letter writing by RCE Saskatchewan since 2009 to help inform governmental decisions for specific developments (including mining, agriculture, and forestry, among others). The goal of this correspondence has been to shift the RCE's region to more sustainable paths in these particular instances but also to strengthen the policies governing new developments. RCE efforts constructively critiquing proposals with substantial opportunity costs or lacking important sustainability dimensions serves as an indirect method for reforming existing government development policies. Where such developments are allowed to proceed without substantive revisions this points to inadequacies in existing policies. An overview of six key components drawn from past RCE letters was presented. The strategic value of each component was illustrated by best case examples. It was conjectured that letters with most or all of these components are an efficient and effective strategy for RCEs seeking a “whole-region” approach to sustainable development. It was noted that this approach is also prudent in the context of substantive levels of uncertainty on how development occurs within regional contexts faced by RCEs along with the value of strengthening existing government policies regulating entire classes of development using the principles of sustainable development embedded in the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals.

The reason the impact of RCE letters is qualified above as only a “conjecture” is due to some significant conceptual limits to this evaluation. RCE Saskatchewan's letter writing to various levels of government is likely not a sufficient causal factor, in itself, in relation to any one government decision. Government ministers and other officials have substantial political pressures along with legal and ethical commitments that shape their decisions. This is coupled with the need to navigate the power dynamics within bureaucracies, at the cabinet table, within legislative assemblies, and the general public. At best, letters from an RCE should be seen as contributing causes to the outcomes listed in Table 1 and explored within this paper. This is not to diminish what seems to have been substantive changes in development paths that have aligned with the recommendations provided by RCE Saskatchewan to government. It may be that RCE letters have acted as tipping points for government decisions, especially where there has been substantive political pressure from development proponents and the local communities affected with no obvious political gain one way or the other. Just as the political theorist Machiavelli argued that when faced with a no-win political dilemma between rival factions, decision makers will tend to choose the ethical option, it could be, all other things being equal, that government decision makers will follow those recommendations supported by the best evidence (including university scholarship and local expertise), and that follow transparent and inclusive processes, employ good governance, and support the long-term sustainability interests of citizens. In this case RCE letters would play a key role.

All the case studies explored are from a Saskatchewan context. This too presents limitations to the generalizability of these findings for other RCEs. RCEs with universities operating in contexts with more limited academic freedoms or within non-democratic countries that lack opportunities for citizen participation in evaluating major developments might find this strategy unworkable. On the other hand such RCE interventions might enable the kinds of community conversations and structural deliberations within government and the private sector that build more robust development processes in line with the sustainable development goals, especially Goal 16 on peace, justice, and strong institutions. It may be, as well, that RCE letter writing can be scaled up geographically where there are multiple RCEs within a country or continent who make strategic interventions with governmental (or other structures) operating at that scale. For example, RCEs in the United States or Canada might choose to correspond with their respective national ministries, while RCEs in the Americas could correspond with pan-American organizations (such as the Organization of American States). Finally, it should be noted that even if such RCE strategies are not generally useful nor causally effective in their own right, they may be quite important in reducing the unknowns in regional development needed for successful RCE educational strategies employed in other areas.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

Luther College at the University of Regina provided funding to cover the Open Access publication fees.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the contributions of RCE Saskatchewan members, partners, and supporters who contributed to the RCE letters on which this article is based along with the government employees who thoughtfully responded to them in the course of their duties.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer CM is currently organizing a Research Topic with the author.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Briere, K. (2019). “Settlement in sight for sask. Water dispute: Peter Onofreychuk has complained since 2011 that upstream agricultural drainage has flooded his farmland,” in The Western Producer, May 23, 2019. Available online at: https://www.producer.com/news/settlement-in-sight-for-sask-water-dispute/ (accessed July 07, 2022).

Canada Ministry of Environment Climate Change. (2016). Minister Catherine McKenna to RCE Saskatchewan re. Decision for No Federal Environmental Assessment of Yancoal Southey Potash Project. Available online at: https://saskrce.ca/official-rce-correspondence/ (accessed November 10, 2022).

Canada Ministry of Environment Climate Change. (2022). Last Mountain Lake Migratory Bird Sanctuary. Available online at: https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/migratory-bird-sanctuaries/locations/last-mountain-lake.html#toc1 (accessed July 07, 2022).

Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency (2018). Anna Kessler, Project Manager, to Kerry Holderness, Quill Lakes Watershed Association re. Common Ground Drainage Channel Diversion Project [note letter dated Jan. 23, 2017 in error]. Available online at: https://saskrce.ca/official-rce-correspondence/ (accessed January 23, 2018).

Charmaz, K. (2004) “Grounded Theory,” in Approaches to Qualitative Research: A Reader on Theory and Practice, eds S. Hesse-Biber and P. Leavy (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 496–521.

City of Saskatoon. (2019). Mayor Charlie Clark to RCE Saskatchewan re. Construction of Saskatoon Freeway and stewardship of Saskatoon Swale. Available online at: https://saskrce.ca/official-rce-correspondence/ (accessed October 10, 2019).

Government of Saskatchewan. (2019). Saskatchewan's Growth Plan: The Next Decade of Growth 2020-2030. Available online at: https://pubsaskdev.blob.core.windows.net/pubsask-prod/114516/Saskatchewan%2527s%252BGrowth%252BPlan%252BFinal%252BNov%252B13%252B2019.pdf (accessed July 11, 2022).