- Finland Futures Research Centre, University of Turku, Turku, Finland

Sustainability and wellbeing are two key global policy priorities, which despite considerable overlap, are invariably isolated. In wellbeing, the importance of social dimensions is an emergent conclusion, but recognition of the environment and nature is embryonic. In sustainability, wellbeing remains poorly characterized. Despite some procedural advantages, in practice, a continued ambiguity risks compromising both goals, and improved conceptual integration is therefore necessary. In this review article, key contemporary wellbeing accounts are considered, including preferences, needs, capabilities, happiness, psychological wellbeing, and physical wellness. Wellbeing literature suggests that a holistic multidimensional account is strongly supported, that is context- and value-dependent, with a prominent role for social and relational dimensions. A transdisciplinary systems thinking approach is appropriate to integrate from the individualism characteristic of wellbeing, to the interdependent human and environmental systems of sustainability. It is recognized that both wellbeing and sustainability are complex and value-laden, requiring the surfacing of values and ethics. A synthesis of the two branches of literature asserts four fundamental lenses: the framing of growth and change; social justice; the ethics of freedom; and the value of nature. The conceptual synthesis both platforms the relational approach of “care,” and underlines the imperative to reconsider the place of consumption. An integrated “sustainable wellbeing” offers the potential for win-win outcomes, in transformation to a flourishing of human wellbeing and the natural world.

Introduction and Background

The Concept of Sustainable Development, and the Place of Wellbeing

The concept of sustainable development (SD) emerged 40 years ago in ideas of a sustainable society, nature conservation, and resource management (Sathaye et al., 2007). It has since become ubiquitous in framing the development of human systems, and their relationship with the environment. From the analytical framing of climate change [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 2018] and biodiversity challenges [Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA), 2003; Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), 2019], to development policy practice in the UN SD Goals 2015, it continues to act as a linchpin, a concept as powerful as it is universal. Since its inception, an evolution is evident in how this complex concept is understood. In 1987, the “Brundtland report” of the World Commission on Environment and Development introduced the seminal definition of SD, that seeks to balance the human-environment relationship; “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED), 1987]1. Signs of evolution can be found in the 2007 global synthesis of Halsnæs et al. (2007), which articulated the emerging basic principles of SD as: the welfare of future generations; the maintenance of essential biophysical life support systems; more universal participation in development processes and decision-making; and the achievement of an acceptable standard of human wellbeing. In the more recent synthesis of Fleurbaey et al. (2014) SD is conceived as: development that preserves the interests of future generations, that preserves the ecosystem services on which continued human flourishing depends, or that balances the co-evolution of the three pillars or spheres; economic, social, environmental. This is a noteworthy change, to articulate SD through “human wellbeing” and “flourishing,” rather than “needs.” Yet, it could be related to a lesser cited reference in Brundtland, to satisfying “aspirations for a better life” [World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED), 1987: 44].

Despite the evolution in the SD concept, there is also robust empirical evidence of a lack of progress, as the actual outcomes of development are demonstrably unsustainable. A variety of environmental systems are now at or near critical thresholds, driven by the pressures of human activity [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 2018; Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), 2019], and attended by problems of equity and growing in-country inequality [International Panel on Social Progress (IPSP), 2018]. Further criticisms have noted, the primary focus on environmental and economic dimensions, while overlooking social, political and cultural change (Sathaye et al., 2007; Fleurbaey et al., 2014), and the anthropocentric framing of most SD frameworks, that do not recognize nature's intrinsic value (Kopnina et al., 2018). The urgency of the sustainability crises sharpens criticism of the definitional vagueness of SD, which provides a conceptual frame without guidance on priorities. Where Robinson (2004) sees “constructive ambiguity,” and Meadowcroft (2000) a necessary flexibility to allow for political contestation, James (2017) and Mensah and Casadevall (2019) point to the risks and problems arising out of continued impreciseness.

More specifically, some scholars have noted a fundamental lack of clarity on the conceptualisation of human “needs” and “wellbeing” (Kjell, 2011; Helne and Hirvilammi, 2015). Yet, as noted above, a shift has occurred widely in SD literature, from articulating human “needs,” to the placeholders of “wellbeing,” and “flourishing.” This can be found across synthesized principles [Sathaye et al., 2007; Fleurbaey et al., 2014; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 2018]2 and in comprehensive reviews (Atkinson et al., 2014; McGregor, 2014). Consistent with the conclusion that definitional ambiguity continues, Kjell (2011) observed that within sustainability research, human “needs” and “wellbeing” are poorly understood, conceptualized, and elaborated upon, arguing that there are implications for the pursuit of sustainability. On the flip-side, the literature that conceptualizes human wellbeing, continues to exist largely outside of SD. The wellbeing concept literature is almost entirely dissociated from the contribution of nature, or relationships with ecological and planetary systems. To understand the significance of this limited integration, it is imperative to recognize that wellbeing has major implications for SD, and vice versa. At the systems level, the strategies to pursue human wellbeing are fundamental to drivers of environmental pressures, where they push the consumption of resources and the generation of wastes. In turn, the environment is a critical foundation underpinning human wellbeing, by providing the natural resources and ecosystem services necessary for human survival and development. Nature also has cultural meaning, and has its own intrinsic value beyond the utility of physical functions (see Existing Literature Seeking Integration of “Sustainable Wellbeing” and The Value of Nature-Intrinsic and Instrumental).

The Concept of Wellbeing, and the Place of Sustainability

Human wellbeing, or “well-being,” is also a major global policy priority in itself, and has been receiving greater empiric and policy priority in recent years. Discussions of wellbeing and “the good life,” have an ancient global history, spanning spiritual, religious, cultural, philosophical and secular traditions, and are represented in voluminous theories (McGillivray, 2007; Varelius, 2013; Fletcher, 2016; Sachs, 2016). A rich and varied discussion is found in the philosophy of wellbeing, which draws on both ancient and contemporary accounts, as alternative perspectives on the fundamentals (Fletcher, 2016). The contemporary applied concept of wellbeing is acknowledged as complex (Huppert, 2014), and occurs across the disciplines of anthropology, economics, psychology, sociology, and other social sciences (Fleurbaey et al., 2014). Within the study of wellbeing, when broadly defined, efforts to bring more consistency to the field include Parfit's “tripartite model” (Parfit, 1984) -which identified three broad philosophical theories in: hedonism; desire fulfillment or satisfaction; and objective lists -. Further efforts can be found in what are sometimes known as MacKerron's “five standard approaches to wellbeing” (MacKerron, 2011), which were originally noted in Dolan et al. (2006a) as: preference satisfaction; objective lists; eudaimonic/flourishing; hedonic; and evaluative approaches.

In general, wellbeing accounts have invariably been conceived separately to nature-environment and sustainability (Roberts et al., 2015). While Dodds (1997) noted the importance of understanding the relationship between wellbeing and sustainability, integration has only received greater attention in the last decade, and is described here as the literature of “sustainable wellbeing.” The applied literature on physical health and mental wellbeing has begun to show increasing scholarship on the contribution of nature (Capaldi et al., 2015; Oh et al., 2017; Britton et al., 2020), but this has yet to substantially influence or integrate with the conceptual and foundational literature of wellbeing.

Existing Literature Seeking Integration of “Sustainable Wellbeing”

The conceptual literature, seeking some form of integration of sustainability and wellbeing, has been dominated by economic welfare, needs, capabilities, quality of life, and happiness studies. The concept of “human needs” has continued to manifest in a number of texts (Rogers et al., 2012; Hirvilammi and Helne, 2014; Helne and Hirvilammi, 2015; Guillen-Royo, 2016; Gough, 2017; Raworth, 2017; Büchs and Koch, 2019). The main alternative to needs, the capability approach, is also found in work by Anand and Sen (2000) and later interpretations (Lessmann and Rauschmayer, 2013; Oakley and Ward, 2018). Hybrid needs-capability approaches have been developed in the last decade (McGregor, 2008, 2014; Coulthard et al., 2011; Rauschmayer et al., 2011; Rauschmayer and Omann, 2015) and the application of happiness studies can also be found in the last decade [Kjell, 2011; New Economics Foundation (NEF), 2012; Cloutier and Pfeiffer, 2015; Sachs, 2016]. In economics, the Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi Commission broke new ground as an influential synthesis of thinking. It recommended reform to measure people's well-being, and the central importance of sustainability, rather than continuing the focus on economic production (Stiglitz et al., 2009). Further indicator discussions occurred through the UN Commission on Sustainable Development, and the OECD “Better Life” initiative, which developed frameworks supporting indicator selection for sustainable development [United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA), 2007], and for wellbeing measurement [Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2011]. See section Wellbeing Accounts in Critical Summary.

A number of synthesis frameworks have considered the links between poverty and needs with ecosystem services (Duraiappah, 2004; Agarwala et al., 2014; Roberts et al., 2015; Schleicher et al., 2018). The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) developed a groundbreaking conceptual framework of “nature and people,” in Díaz et al. (2015), as a synthesis that seeks to broaden from poverty to more generalized wellbeing, and from ecosystem services to social and ecological systems. IPBES employ epistemological and ethical innovations through a systems thinking approach, that considers social and ecological components across scales, culture and time, and the key relationships between them. Díaz et al. (2015) describe the six main elements linking people and nature as: nature; nature's benefits to people; anthropogenic assets; institutions and governance systems and other indirect drivers of change; direct drivers of change; and good quality of life. The two key innovations of IPBES are, firstly, the expansion of ethical categories, from solely anthropocentric values to include ecocentric, by declaring nature's own intrinsic value3. Secondly, they employ a synthetic description of “good quality of life4” using a broad interpretation similar to the Millenium Ecosystem Assessment [Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA), 2003], itself based on the “voices of the poor” by Narayan et al. (1999). The IPBES framework seeks deeper levels of integration, at the frontier of literature on sustainable wellbeing, by richer descriptions of wellbeing, and by enhancing the systems and ethical framings of sustainability.

The levels of integration in the sustainable wellbeing literature are vastly different, from excluding the environment in standard wellbeing literature, to shallow integration by including it as a resource to be exploited, to deep integration in the transdisciplinary synthesis of Diaz et al. Raworth's doughnut has been criticized for shallower integration, by artificially separating the environment as an ecological ceiling -a resource for consumption in development- and also for arbitrarily selecting factors in its “social foundation” (Krauss, 2018). It is also important to question if conceiving wellbeing, based on needs, is sufficient? The IPBES (Díaz et al., 2015) provides a deeper integration of nature and environment, and does not rely solely on needs, yet prompts the question could the wellbeing description based on Narayan et al. be further enriched?

Objectives, Approach, and Structure of the Article

The IPCC Fifth Assessment Report (Fleurbaey et al., 2014) concluded that decoupling human wellbeing, from economic growth and consumption, is the strongest form of transition to SD. Pioneered as the “double dividend,” to achieve improvement in wellbeing alongside a reduction in consumption by Jackson (2005), Rogelj et al. (2018) noted that the concept is crucial to sustainability transition/transformation, and shows more synergies than tradeoffs. Despite the evident merit and opportunities, conceptual literature, that integrates sustainability and wellbeing, remains embryonic. Persistent ambiguity in the characterisation of wellbeing in sustainability will hamper the task of transition. Recognizing the disconnect between contemporary sustainability and wellbeing concepts -in the weak conceptualisation of wellbeing in sustainability, and the lack of inclusion of sustainability in wellbeing- this review seeks to provide deeper transdisciplinary integration. As is defining of sustainability, Halsnæs et al. (2007), emphasize that transdisciplinary outcomes are holistic, weaving knowledge from a number of existing disciplines, into new concepts and methods, to address the many facets of sustainable development, as per Munasinghe (2002)5.

Section Introduction and Background has characterized the wider concept of sustainable development, highlighted the conceptual literature on human wellbeing, and discussed current literature that seeks some form of integration of “sustainable wellbeing.” Section Contemporary Accounts of Wellbeing considers the major approaches to human wellbeing, across the social science literature, including notable implications for sustainable development. The accounts included for discussion are in line with the standard approaches noted by Parfit and Mackerron/Dolan et al. accounts that are already found in sustainable wellbeing literature. The literature review of section Contemporary Accounts of Wellbeing demonstrates that at least three further branches of wellbeing conceptual literature have emerged in the last two decades: hybrid accounts from psychology, in “wellbeing research,” and “wellbeing science”; accounts from the study of physical health and “wellness”; and advances in philosophical discussion on the concept of wellbeing. These three branches of literature neither fit neatly into the classifications of Parfit or Mackerron, nor have they featured in the existing literature of sustainable wellbeing, and are therefore included for completeness. Section Synthesis and Discussion provides a synthesis that seeks to integrate the concept of sustainability, as discussed in section Introduction and Background, with that of human wellbeing, as discussed in section Contemporary Accounts of Wellbeing. Section Conclusion concludes the review by emphasizing the modes to deepen integration, and the broad implications for future research and policy, of an integrated concept of “sustainable wellbeing.”

Contemporary Accounts of Wellbeing

The following section considers the standard approaches to wellbeing in the literature, as per Parfit or Mackerron, supplemented with recent advances in psychology, physical health and in wellbeing philosophy. This section also scrutinizes key conclusions on each wellbeing account, through the sustainability lens, where available in the literature.

Preference Satisfaction and Desire

It is broadly accepted, across development, and welfare economics, that there is an important contributory role for physical resources and income, in support of welfare, particularly in the case of poverty and deprivation (Agarwala et al., 2014). While thinkers such as Pigou emphasized the importance of income and wealth to welfare, this has also been contested. Marshall's concept of “economic welfare,” from 1890, specifically discussed “wellbeing” and recognized the central role of immaterial “goods,” such as nature and social relations (Marshall, 2009). To simplify complexity, and enable quantitative analysis, Marshall proposed a compromise. This prioritized the “material requisites of wellbeing,” where “efforts” and “wants” are measured through the proxy of money. The related “preference satisfaction” account of wellbeing has come to dominate orthodox neo-classical economics (Roberts et al., 2015). It articulates wellbeing as the freedom and resources to meet one's wants and desires, sometimes referred to as “desire fulfillment theory.” This is core to the theoretical and ideological platform that advocates economic growth, yet the compromise of Marshall remains problematic.

Contemporary measurement and analysis of welfare has involved income, material resources, and psychological states. All three of these approaches have been described as too narrow (Sen, 1985; Fleurbaey, 2009). Fleurbaey and Blanchet (2013) recommend “equivalent income” allowing comparison of individuals functioning, by placing money values on the important dimensions of life that are not priced in the market. Yet the challenge of the “fetishising of resources and money” (Sen, 1982), remains an ongoing tension in economic welfare (Fleurbaey, 2015). Marshall's “law of diminishing marginal utility” was preceded by general discussion of the damaging effects of consumption, persistent since the Ancient Greeks, as it can undermine the balance of the individual, and threaten society (Dodds, 1997). This is particularly problematic for preference satisfaction, as its organizing principle is consistent with driving unlimited desire for income and consumption, a principle that has major consequences for individual, collective and planetary wellbeing.

While recognizing empirical innovations, as an account of wellbeing, preference satisfaction is subject to many challenges. Fleurbaey et al. (2014) note empirical controversies in the relationship between subjective well-being and income, including the “Easterlin paradox6”. Heathwood (2016) emphasize that desires can be manipulated, malicious, unwanted or ill-informed. Kahnemann concludes that awareness of the impact of our preferences on wellbeing is frequently limited (Kahneman, 1997), and Dolan et al. note that we are even less likely to be informed of the impacts on others (Dolan et al., 2006b). It has been submitted that preference satisfaction is not a model of well-being, as it is indirect and relegates it to equivalence with quantitative economic welfare [New Economics Foundation (NEF), 2008]. It is on this basis that Agarwala et al. (2014) propose that the concept of “wellbeing” has emerged largely in response to the inadequacy of uni-dimensional and monetary examinations, to describe the human condition. Two key alternatives in development and economics, are human needs and the capability approach.

Human Needs, Basic, and Fundamental

Human needs have a long heritage in western philosophy, two notable contemporary accounts can be found in “Basic Human Needs” and “Fundamental Human Needs.” These have common roots in the work of Maslow, a theory of human motivation from psychology based around a hierarchy of needs; physiological, safety, love, esteem, and self-actualisation (Maslow, 1943). Maslow's theory was later amended to place self-transcendence as a motivational step beyond self-actualisation (Maslow, 1969), and the collected works have been influential not only on psychology and sociology, but on development and economics. Drawing on Maslow, and on Rawl's theory of justice (Rawls, 1971), the basic needs movement of the 1970's and 1980's, was influential in international development policy. It was effective in platforming the moral and political argument to address poverty, in the form of core physiological needs for food, water, shelter and clothing (McGregor, 2014). This found expression in the Brundtland definition of SD, rooted in essential needs [World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED), 1987].

Basic needs analysts have insisted that non-material, as well as material needs, must be included, but in practice basic needs has focused primarily on material goods and services (Stewart, 2006). Sen is critical of what he saw as “commodity fetishism” in basic needs (Sen, 1984), giving “a meager view of humanity” (Sen, 2004). Basic needs have attempted to consider opportunities for a full life (Clark, 2006), yet they have receded as the capability approach (CA) became more dominant. The CA seeks to address all levels of development, rather than just poverty (Reader, 2006). Grix and McKibbin (2016) contend that needs are useful as accounts of wellbeing, but are critical of where they are defined by survival and harm avoidance as the ends. They propose that wellbeing and flourishing are more appropriate ends, and that needs are proxies that have different normative weight.

A distinct move away from hierarchies occurred with Allardt (1976), who defined wellbeing through satisfaction of non-hierarchical needs, in three groups: having, loving and being7. This appeared to influence Max-Neef's work on Human Scale Development (Max-Neef et al., 1989), describing nine non-hierarchical “fundamental human needs8”. These needs occur in four flexible existential categories of: being, doing, having and interacting, allowing the means to satisfy needs to be defined by culture and individual circumstance. Max-Neef proposes the nine fundamental needs as finite, few and classifiable, the same across all cultures, and in all historical periods. Common to needs-based approaches, this questions the reductive and insatiable economic “wants” in conventional preference satisfaction.

Fundamental human needs can be described as “objective lists” of wellbeing. Objective lists can be attractive as they are both intuitive and supported by theory (Fletcher, 2016). Evidence from empirical study of life evaluation and subjective wellbeing (SWB) has offered support to needs accounts (Kingdon and Knight, 2006; Tay and Diener, 2011)9. Needs have received challenge from liberal concerns about elitism and paternalism, perceiving that as the constituents of wellbeing are prescribed, it demotes the ability to freely define one's own account. Yet wellbeing philosophers have argued that such objective lists are no more a theory of what people ought to have for their wellbeing, than hedonism or desire fulfillment, and can be combined with the most stringent of anti-paternalism conditions (Fletcher, 2016; Crisp, 2017).

The Capability Approach

The social indicators movement of the 1960's gave rise to concern for multidimensional outputs, as objective lists, as opposed to inputs such as income. This movement sought to consider wellbeing independently of subjective individual happiness or desire fulfillment (Angner, 2016). In line with this flux, Sen's CA, (Sen, 1985, 1992), was developed from welfare economics as the leading alternative framework for thinking about human development (Clark, 2006). It emerged from increasing criticism of economic growth as a means to secure increases in wellbeing (Qizilbash, 1996), and also of the perceived incompleteness of the needs-based and “happiness” accounts. The CA is concerned with valuable doings and beings, and is often presented as an intermediate between the narrow resourcist (material) and hedonic (pleasure and pain) accounts. It seeks to account for all of the relevant dimensions of life, as mental and physical states conceived through freedom (Sen, 1985; Fleurbaey, 2009; Fleurbaey and Blanchet, 2013). The CA has the basic proposition that we should evaluate development and progress on what people are effectively able to do and be, as ‘the expansion of the “capabilities” of people to lead the kind of lives they value—and have reason to value' (Sen, 1999). The approach differentiates potential and achievements, where capabilities describe potential functionings, and functionings are actual achievements10, with the freedom to define valuable doings and beings at its core.

In an attempt to elaborate, Nussbaum (2005) specified a list of 10 core human capabilities that are argued as fundamental, universal entitlements to secure social justice (see Table 1). Yet only the possibility of achievements can be guaranteed, and only at minimum levels. This return to basic levels makes it “impossible” to develop a full theory of wellbeing that applies to all circumstances, not just situations of poverty and subsistence, according to Fleurbaey and Blanchet (2013). It was this challenge that led Sen away from needs, to “functionings” for all sorts of doings and beings, at any level of affluence and development, that may matter in defining a flourishing life. Sen shunned a prescriptive list of capabilities, to facilitate definition in diverse social and cultural contexts, avoiding paternalism by placing agency centrally. The CA has expanded considerably, and has been refined since its inception, with much literature in support (Stiglitz et al., 2009). Challenges have been evident in the lack of specification which creates difficulties for empirical applications (Fleurbaey, 2009)11. Schokkaert (2009) suggests that many proclaimed applications appear to be merely studies of living conditions incorporating non-market data. But beyond these empirical difficulties, the challenges of “freedom” and sustainability are considerable.

To Sen, freedom is central to the conception of capabilities, yet the philosophical underpinnings of the related issues of individual freedom, agency and what we have reason to value, are criticized (Clark, 2006). In a world that demonstrates significant inequality, with uneven opportunity and unequal power, the exercising of an individual's freedoms can significantly limit the freedom of others, and even violate their rights. This returns to social justice accounts, as the actual full extent of freedom is therefore inevitably limited by this “negative freedom” (Qizilbash, 1996). Gasper (2002) requires a balance between the needs and freedom of the individual, with those of others, and also an appropriate account of the “reason” of what people value. Gasper and van Staveren (2003) require “freedom” to be anchored by justice and the value of caring for others. Deneulin and McGregor (2010) propose a reframing to include both an individual and social conception, from “living well” to “living well together.” These criticisms can be related to Rawls first principle of justice: “Each person is to have an equal right to the most extensive total system of equal basic liberties compatible with a similar system of liberty for all” (Rawls, 1971). The criticisms are consistent with Sen's earlier work, which itself emphasized the importance of democracy, respect and friendship. Yet Sen has been deliberately ambiguous, and this can be seen either as theoretical flexibility, or as a weakness12. The lack of guidance has led to its description as “more a paradigm than a well-defined theory” (Robeyns, 2003), indeed the CA does not fully resolve these issues, and does not attempt to. Sen's more recent work has conceded that equality matters apart from capabilities, and that the approach does not provide a full theory of justice (Sen, 2009).

The considerable challenge of negative freedoms in the social dimension, also has major implications for the environmental dimension. The expansion of individual capabilities threatens both equality and environmental sustainability. An expansion of the capabilities of “having,” in increased material consumption and its related environmental pressures, has major implications across generations and for the natural world. This is clearly illustrated by global heating and ecological breakdown, which have chiefly been driven by the high consumption of the more affluent. Anand and Sen (2000) attempt to rectify this with a concept of “integrated sustainable human development” to address both the claims of the present, and of future generations, to a “generalized capacity” of the environment to produce wellbeing. However, natural capital is not perfectly substitutable [European Environment Agency (EEA), 2015], and “planetary boundaries” cannot be transgressed if the capacity for capabilities are to be transmitted to future generations (Häyhä et al., 2016). Adopting an unspecified “generalized capacity” runs into major difficulties, when it is recognized that the natural world underpins both survival and wellbeing. Consequently, it will be necessary to constrain peoples' combinations of functions in some way to reconcile capabilities with sustainability (Peters et al., 2015), aware of the problems of an absolute freedom. Fleurbaey and Blanchet (2013) suggest that the main message of the CA is to avoid narrow evaluations of individual wellbeing. It is neither a theory of wellbeing, nor of sustainability, and in response to this, Gasper (2002) recommends that capabilities focus on measuring of personal advantage.

Happiness Studies: Hedonic and Evaluative

Under the umbrella of happiness studies, both psychologists and economists have increased interest in subjective mental states. Happiness is an ambiguous concept associated with the field of positive psychology, and is often used as a catchword for subjective wellbeing (SWB) (Fleurbaey et al., 2014). Diener and Seligman (2004) describe how happiness itself can measure pleasure, life satisfaction, positive emotions, a meaningful life or a feeling of contentment among other concepts, as individual self-reported measures. Prominent among these are measures are “hedonic” indicators of current feelings -of positive and negative affect- and the “evaluative” judgement of satisfaction with life as a whole. A seminal contribution was made by Diener, through the model of SWB, which incorporates cognitive judgments of satisfaction and affective appraisals of moods and emotions (Diener, 1984).

The World Happiness Report (Helliwell et al., 2012) characterized happiness as a subjective experience, but one that can be objectively measured and analyzed, related not only to individual characteristics and objective circumstances, but to those of the wider societal context. Within the Report, Layard et al. (2012) looked at external factors (income, work, community, governance, values and religion) and “personal” factors (mental health, physical health, family, education, gender, and age), concluding from 30 years of happiness research, that while income is important, particularly for those experiencing poverty, it has limits in its contribution to average global wellbeing. They re-asserted the “diminishing marginal utility of income,” and that the results of both life satisfaction and SWB show a greater contribution of other determinants: social support; health; freedom; and the place or absence of corruption. Sachs (2016) examined the relationship of economic freedom (libertarianism), wealth generation (consumerism) and SD (holism), to global happiness13 SWB data for 119 countries. Sachs concluded that it is SD that is statistically significant in determining happiness, and this was bolstered by recent study that highlighted social safety nets and public health among key factors (Richardson et al., 2018).

While happiness is climbing up the ladder of priority for research and public policy, debate, and criticism frequently point to: conceptual challenges, as wellbeing requires more than happiness or hedonism14 (Sen, 1985; Fletcher, 2016); measurement difficulties and biases toward hedonic wellbeing (Fleurbaey and Blanchet, 2013); and the phenomenon of psychological adaptation (Fleurbaey, 2009; Stiglitz et al., 2009). As individuals undergo adaptation to circumstances, this means that self-report measurements can be somewhat immune to actual life conditions, leading to concerns about social justice where objective inequalities are hidden.

Psychological Wellbeing and Flourishing

The “flourishing” accounts focus on ways of “living well,” or the “good life,” for an individual to reach full potential. Different branches identify wellbeing with characteristics of life such as, engagement, meaning, virtue, and authenticity [New Economics Foundation (NEF), 2008]. Flourishing is classically related to Aristotelian theory of human good, the “perfectionist” account, holding that virtue or excellence are closely tied to human nature, and that flourishing involves engaging in activities that exercise these. This “eudaimonic” living, in perfectionist accounts, has been challenged for potentially excluding pleasure and preferences, and concerns of elitism. Yet Bradford (2016) notes that flourishing accounts can function either as a theory of value, or as a theory of wellbeing, and therefore can be calibrated to address these concerns. Contemporary psychological wellbeing, in “wellbeing science,” clarifies that flourishing and perfectionism are not the same.

“Wellbeing science” refers to a more broad concept than “happiness,” incorporating both hedonia and eudaimonia as distinct concepts that are mutually supportive (Kashdan et al., 2008; Huta and Ryan, 2010). “Hedonia” is linked to the Benthamite tradition of desiring pleasure and avoiding pain, and classically to Epicurus. The hedonic perspective suggests that maximizing pleasure and avoiding pain is the pathway to happiness (Henderson and Knight, 2012). While classically related to Aristotelian theory, “eudaimonia,” in wellbeing science, is described as having associations with goals, particularly those related to intimacy rather than power, and also associations such as flow, altruism, and helping and autonomy. Henderson and Knight (2012) describe eudaimonia as directed toward living a life of virtue, actualising one's inherent potentials, personal growth and meaning. While these are distinct and contribute to wellbeing in unique ways, they are also highly related (Huta and Ryan, 2010). Empirical results from numerous studies reviewed by Kashdan et al. (2008), show, that in general, eudaimonia is not simply linked to a qualitatively different kind of happiness, but quantitatively to higher levels of hedonic wellbeing. Henderson et al. (2013) argue that increasing both hedonistic and eudaimonic behaviors may be effective in both increasing wellbeing and reducing psychological distress.

In applied psychology, these philosophies have been incorporated, the resulting approach has sought to move from an approach to mental health that is pathological, dealing with mental health problems, to deal with “positive mental health” (Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). Positive mental health includes a psychological concept of “flourishing15” (Huppert, 2009), where wellbeing is defined as more than the absence of disorder. The theoretically derived dimensions of positive psychological health include; Self-acceptance, Positive relations with others, Autonomy, Environmental mastery, Purpose in life, and Personal growth (Ryff, 1989). The seminal work of Ryff, on scales of Psychological Well-Being, is the most widely used measure of positive psychological functioning. Keyes (1998) went a step further by explaining that while psychological wellbeing represents the necessary private and personal criteria, social well-being epitomizes the public and social. The social dimensions consist of social coherence, social actualisation, social integration, social acceptance, and social inclusion. Individuals can then be described as functioning well: when they see society as meaningful and understandable; that society possesses the potential for growth; when they feel they belong to and are accepted by their communities; when they accept most parts of society; and they see themselves as contributing to society. This transcendence of the individual, in the individual-society description of Keyes, can be seen in Adler and Seligman's concept of personal, societal and institutional “flourishing” (Adler and Seligman, 2016), and also in the new field of “wellbeing research,” illustrating that a systemic social perspective is emergent.

“Wellbeing research,” with roots in wellbeing philosophy and psychology, has pioneered an innovative holistic representation of individual wellbeing. It addresses difficulties noted in the philosophical separation of “hedonic” and “eudaimonic” living, and encompasses external and relational life domains. These are termed “wellbeing pathways” (Huta and Ryan, 2010; Henderson and Knight, 2012), “full-life” or “integrated pathways” (Waterman, 1993; Seligman et al., 2004; Peterson et al., 2005; Huppert and So, 2009). Delle Fave et al. (2011) refine this as “integrated wellbeing pathways,” as combinations of hedonia, eudaimonia and engagement activities16 that lead to higher overall wellbeing; physically, psychologically, socially, and in terms of flourishing, such as growth and fulfillment. Endorsed by Henderson and Knight (2012) for further wellbeing research, Delle Fave et al. (2011) define pathways by outlining 11 different life domains: work, family, standard of living, interpersonal relationships, health, personal growth, spirituality/religion, society issues, community issues, leisure, and life in general. Among the life domains, the social and relational feature prominently, and the relatively overlooked dimension of harmony/balance, constitutes an important aspect of lay people's conceptions of happiness. In a study of Eudaimonic and Hedonic Happiness Investigation (EHHI) of citizen definitions of happiness, across 12 nations, results showed that inner harmony17 predominated among psychological definitions, and family and social relationships among contextual definitions (Delle Fave et al., 2016).

Similar to happiness studies, it is important to consider potential limitations in measurement difficulties, biases and psychological adaptation. Wellbeing pathways may also benefit from directly considering nature-environment, as this is currently not included as a life domain. Nonetheless, they provide unique holistic perspectives on individual wellbeing, integrating hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing, and considering the social, relational and external. They also address an overlooked consideration in happiness studies, which exclude harmony and balance18, which could potentially be a bias of significant importance. Wellbeing pathways note that achieving a balance between different needs, commitments and aspirations may be more important to wellbeing than simply “having more” (Henderson and Knight, 2012; Delle Fave et al., 2016), providing an important overlap with SD and addressing over-consumption.

Physical Health and Wellness

A strong connection between physical health and broader wellbeing is frequently assumed. Although adaptation may occur to many life changes19, physical pain and psychological problems are exceptions in studies of SWB (Kahneman, 2003; Krueger and Stone, 2008; Fleurbaey, 2009). A priority on pathology can be intuited from utilitiarian and justice perspectives, but on its own this may constitute a “meager view.” In contrast, Larson (1999) conceptualizes physical health according to three different models: the medical model; the WHO model; and the wellness model. Whereas, the medical model pertains to pathology, the other two models are strikingly different, focusing on wellbeing rather than ill-health. The WHO model refers to a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being [World Health Organisation (WHO), 1946], and the wellness model involves progress toward to higher functioning, energy, comfort, and the integration of mind, body, and spirit. The latter two models constitute a shift toward a hybrid account, by flourishing and objective list, with wellbeing a priori as the objective. They also show that physical and psychological wellness are protective against pathology. A variety of wellness models, from the 1960's onwards, are reviewed by Oliver et al. (2018), noting that while the dimensions may differ, they are consistently holistic and multidimensional, recognizing the importance of balance and the interrelatedness of the individual with the external environment.

Naci and Ioannidis (2015) are critical that most medical research continues to address the effectiveness of drug interventions, and that little is known about the causes of “wellness.” They describe “healthy” people as differing vastly in terms of wellness; whether their life is filled with creativity, altruism, friendship, and physical and intellectual achievement. In response, they propose an agenda for “wellness research” that addresses gaps in knowledge on diverse and interconnected dimensions of physical, mental, and social well-being. Similar to the re-casting of psychological wellbeing that has occurred, this nascent effort offers a distinct opportunity to re-frame physical health, as more than survival or absence of disease, but as positive flourishing of wellbeing.

Synthesis and Discussion

Wellbeing Accounts in Critical Summary

Wellbeing has been a major theme throughout the history of moral philosophy, and recently, it has become the subject of increasing empirical investigation, particularly in the social sciences of psychology and economics. To arrive at an integrated concept of “sustainable wellbeing” it is useful to consider the existing contemporary approaches to human wellbeing. Theoretical and applied fields have sought description: by satisfaction of preferences and needs; functioning by capabilities; psychological and physical health (by subjective self-evaluation and objective measurement); and by determination of objective lists. These accounts have typically focussed reductively on the individual, or their aggregate sum, facilitating discipline and context-specific knowledge, often to enable quantitative analysis. In order to distinguish alternative accounts, the “philosophy of well-being” has provided a useful lens, to seperate “substantive” claims -what constitutes wellbeing- and “formal” claims -what makes it “good” in terms of normative, or prudential value (Grix and McKibbin, 2016).

Section Contemporary Accounts of Wellbeing illustrated that preference satisfaction, basic needs, capabilities, and happiness studies all contribute useful insights. They can also be complimentary, triangulating different perspectives on the same problem. Yet these approaches do not provide holistic theories of wellbeing in themselves, and usually do not purport to. Preference satisfaction and desire theories aid understanding of the contribution of economic welfare, but are subject to criticism for being indirect, with too many prudential goods and fetishising resources and money. Basic needs encourages the normative focus on poverty and inequality, and critique of consumption, but is criticized for being hierarchical and narrow in fetishising resources. Capability theory has been influential in prioritizing functioning, but is criticized for being under-specified, fetishising freedom, and for incompleteness relative to justice and sustainability. Happiness studies has been lauded for promoting self-evaluated outcomes, but are criticized for having too few good makers, as it is limited to hedonia, and also for being open to biases and blindspots.

In contrast, Fletcher (2016) and Grix and McKibbin (2016) point to the advantages of beginning with objective list type approaches. Objective list accounts offer advantages for description of sustainable wellbeing, enabling the kind of descriptive holism, flexibility, and integration, that are necessary to bridge social and natural sciences, in a transdisciplinary sustainability science. Holistic description is necessary for characterisation, and/or generalization, and objective lists can combine this holism with a flexibility for different values, across individuals and cultures. They can avoid the problems of too many or too few good makers, can be appropriately supported by theory and evidence and can be subjected to public deliberation.

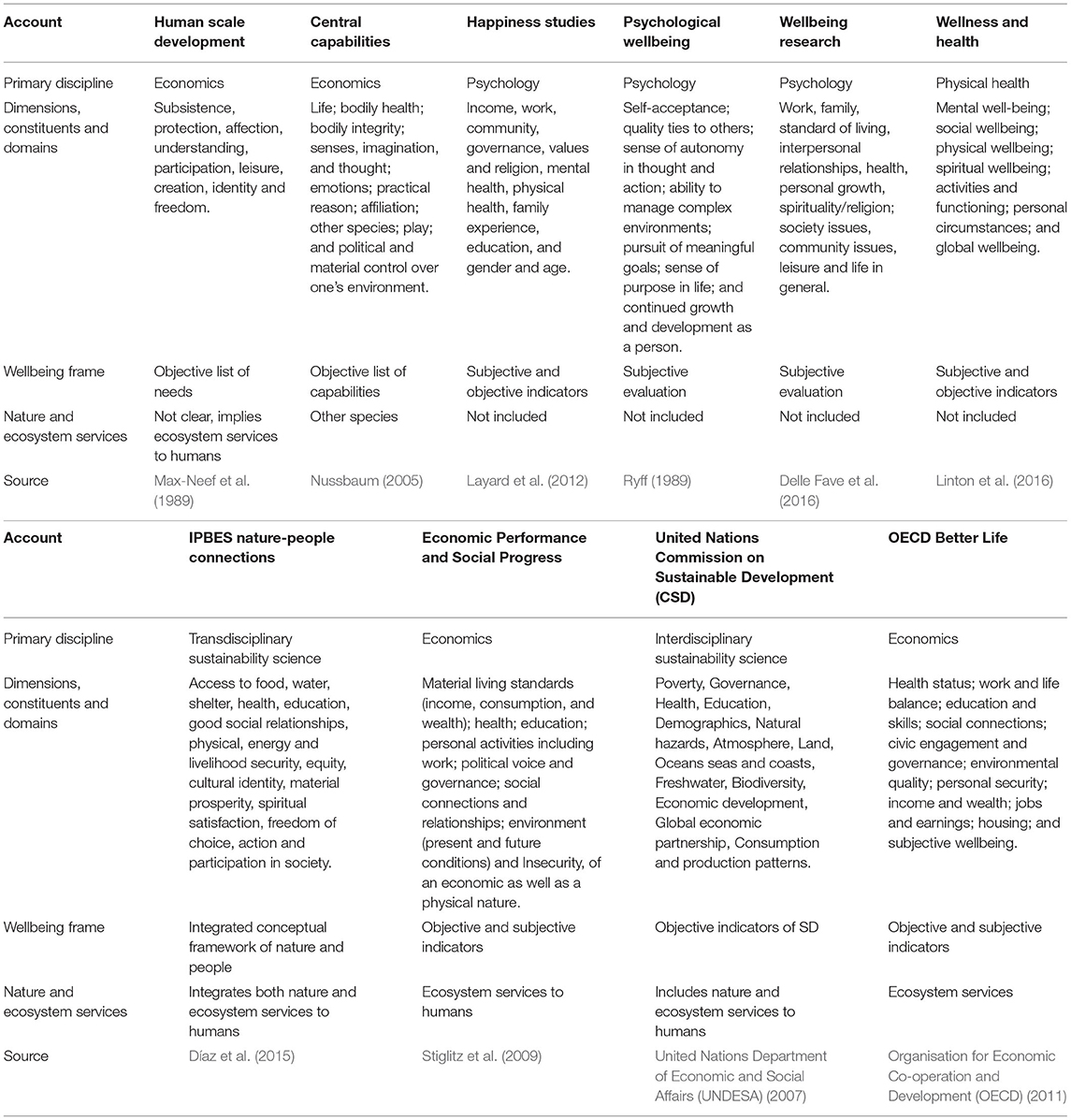

Objective lists are analogous to “multidimensional wellbeing,” described by a variety of accounts in Table 1. The table characterizes the conceptual accounts20 discussed in section Contemporary accounts of Wellbeing: human scale development (needs); central capabilities; happiness studies; psychological wellbeing; wellbeing research (psychological wellbeing and flourishing); and wellness and health. The table also includes the conceptual accounts discussed in section Introduction and Background (IPBES and Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi), supplemented with indicator initiatives from the UN Commission on Sustainable Development and the OECD, to enhance supporting illustration. The table presents the dimensions, constituents or domains that are listed under each account, and notes whether they enumerate nature or ecosystem services, to demonstrate the gaps in interpretation emphasized throughout this review. As background information, the table also notes the source, primary discipline and the “wellbeing frame.” The wellbeing frame considers defining characteristics of each account, emergent from the review in section Contemporary Accounts of Wellbeing: whether objective or subjective assessment is included; and whether the account is intended to list dimensions, to provide a conceptual framework, or to support indicator development. Table 1 does not seek a definitive universal interpretation of sustainable wellbeing, but offers support to the further interpretation required in applied contexts.

Describing Multidimensional Human Wellbeing

Using a multidimensional wellbeing concept, as an “objective list,” is consistent with recognizing it as a complex phenomenon [Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA), 2003; Waterman, 2008], understood broadly across the domains of life, similar to Easterlin (2006), and requires a transdisciplinary or at least interdisciplinary approach (Rojas, 2009). A multidimensional concept of wellbeing is supported, not only by an ancient heritage of philosophical discourse21 (Varelius, 2013; Angner, 2016; Sachs, 2016), and by a variety of needs, capability, happiness, quality of life, social progress, psychology, and physical wellness approaches, but by contemporary conceptual discussion (Alkire, 2002; McGillivray, 2007; Fletcher, 2016) empirical results (Tay and Diener, 2011; Layard et al., 2012; Sachs, 2016), expert panels [Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA), 2003; Stiglitz et al., 2009], citizen deliberation and participation (Delle Fave et al., 2011, 2016) and in the holistic new “science of wellbeing22” (Huppert et al., 2005). In Table 1, the descriptions of the dimensions of wellbeing show variations related to the specifics of discipline, aims, and context. Yet, there is also significant complementarity and overlap, which potentially enables generalization and blending. Conceptual discussion commonly concludes that wellbeing has both objective and subjective dimensions, and that relational dimensions are central to understanding (Huppert et al., 2005; McGregor, 2008; Stiglitz et al., 2009; Agarwala et al., 2014; Díaz et al., 2015).

Social and relational factors are repeatedly found to be crucial to individual wellbeing (Keyes, 2002; Huppert, 2009; Tay and Diener, 2011; Naci and Ioannidis, 2015) but are also to related societal wellbeing (Helliwell and Putnam, 2004; Delle Fave et al., 2011, 2016; Bartolini, 2014; Bartolini and Sarracino, 2014). This conclusion is consistent with the results of studies in behavioral economics, neuroscience and in evolutionary biology, as humans are now conceived of as profoundly prosocial (Jensen et al., 2014)23. The emergence of the importance of social and relational factors, beyond the reductive individual, is a key finding from the review across the disciplines in this article. It is consistent with the bio-psycho-social model, endorsed by the WHO since the 1940's, but rarely actualised in practice (Delle Fave et al., 2016).

An important conclusion from sustainability is that the relational dimensions involve society but also people-nature connections (Díaz et al., 2015). The individualist approaches have often reductively downplayed society (Kjell, 2011), but crucially for sustainability, they frequently avoided consideration of ecosystems, the environment and nature entirely. The importance of the “sustainability,” “environment,” “other species,” “ecosystems,” and “nature,” has been noted (Nussbaum, 2005; Stiglitz et al., 2009; Helne and Hirvilammi, 2015; Roberts et al., 2015), yet applied accounts have placed less emphasis, or more frequently discounted them entirely. In wellbeing research, Delle Fave et al. (2016) provide a robust defense of the “ontological interconnectedness characterizing living systems,” across conceptual frameworks, disciplines, and cultures, providing a platform to rectify this omission.

The “flourishing” concept, relatively common across psychology, and overlapping with the positive functioning of the wellness model -at the frontier of physical health- are of potential major significance for describing “sustainable wellbeing.” In contrast to other accounts, flourishing and wellness are holistic and integrated in wellbeing dimensions, seeking to focus directly on the processes and outcomes of thriving multidimensional human wellbeing. From an individual locus, they can assist in the understanding of thriving, and also languishing and the complexities of poverty, across all levels of development. The increasing emphasis on interconnectedness of dimensions, and the importance of social wellbeing, can be observed in the personal, societal, and institutional flourishing of Adler and Seligman (2016). However, there remains a clear absence of nature and environment in these accounts. Kjell (2011) also argues that as the dominant approaches in psychology are methodologically individualist, a group-level perspective is absent. To describe sustainable wellbeing it is necessary to broaden and deepen integration, to ensure sociological and environmental dimensions are appropriately represented, and provide a comprehensive sustainability concept that recognizes and embraces system interdependence.

Deepening Integration, From Wellbeing Holism to a Systems Lens

The applied fields of wellbeing have been dominated by a reductionist focus on the individual, frequently tied to issues of measurement, and the links to SD have remained tenuous. In moving toward a concept of sustainable wellbeing, integration is crucial. This involves achieving holism across wellbeing dimensions, but also beyond the individual, to the systems that are interdependent with, and impacted by, our collective wellbeing paths. As SD is accepted as a complex systemic construct24 (Halsnæs et al., 2007), describing a concept of sustainable wellbeing requires deeper integration. This involves moving beyond the individual to consider interrelated socio-ecological-economic systems (Lessmann and Rauschmayer, 2013; Díaz et al., 2015), from the local scale, up to planetary systems where aggregate sustainability impacts of human wellbeing paths are materializing. The understanding of the links between wellbeing and the economy has matured, yet as discussed, consideration of relational wellbeing with society is emergent, and relational wellbeing with environment and nature is embryonic. Synthesis can be achieved by integrating the social sciences of human wellbeing, and related social and economic systems, with the physical and sustainability sciences. The latter describe the environment and nature, and interrelationships with human systems at different levels. This process involves traversing from wellbeing theories, which are primarily methodologically individual, to sustainability science which is plural and systemic.

Dodds (1997), discussed the co-determination of social, economic and environmental systems, recommending the integration of wellbeing and sustainability using a holistic systems thinking approach. In the intervening years, the framework known under the loose term of “Systems Thinking” has emerged, as a transdisciplinary and synthetic response to the inability of normal disciplinary science to deal with complexity and systems—the challenges of sustainability (Halsnæs et al., 2007). This epistemological framework recognizes human, natural and combined systems, as interrelated in hierarchical structures that grow and adapt25. Applying sustainability science and systems thinking to wellbeing could support moving beyond the “decontextualised methodological individualism,” described by McGregor and Sumner (2010) and Kjell (2011). This could facilitate the inclusion of both the psychological and sociological co-construction of wellbeing, and also of interdependent ecosystems and nature. This was approached by Díaz et al. (2015) as “nature-people connections” -an integrative systems approach, and by West et al. (2018) as embodied in “relationality,” a set of normative, methodological, and ontological approaches that are distinct, and yet closely related.

West et al. (2018) expanded on “relational values” and “relational thinking,” where relational values reflect a normative sense of connection or kinship with other living things, reflective and expressive of care, identity, belonging and responsibility, “relational thinking” is used in sustainability science. Relational thinking may be used methodologically to describe approaches insisting on mutual consideration of social and ecological entities, or, ontologically, to challenge the idea of foundational entities altogether, in processual accounts emerging through heterogeneous associations in flux. These relational approaches allowed West et al. (2018) to expand on “stewardship,” the now popular term to describe action for sustainability (Bennett et al., 2018). Previously dominated by a focus on the responsible use of natural resources, West et al. articulated sustainability stewardship through the relational approach of “care”: care as embodied and practiced; care as situated and political; and care as emergent from social-ecological relations. Notwithstanding these ontological and methodological innovations, toward holism, it is also imperative to recognize that the questions involved, in both sustainability and wellbeing, are also deeply normative. They cannot be resolved by empirical or quantitative methods alone, as they intrinsically involve issues of values and ethics26.

Key Lenses to Assist Integrating Sustainable Wellbeing

SD has been alikened to “democracy,” “freedom,” and “justice,” as norm-based meta-objectives (Sathaye et al., 2007), and wellbeing can be similarly described. Well-being and ill-being are acknowledged as complex and value-laden concepts, expressed and experienced as context- and situation-dependent, reflecting local, social and personal factors such as geography, ecology, age, gender, and culture [Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA), 2003]. Ambiguity in these concepts facilitates appropriate contestation, and also allowed SD to act as unifying political meta-objective (Meadowcroft, 2000). However, as noted previously, while flexibility has been a key strength, it is also a critical weakness. In the practice of applied fields, it must journey from a vague value-based general concept, that wellbeing and sustainability are “good,” to context-based implementation, particularly across governance and strategic public policy, but also in analysis. Without such a process, current dynamics likely render it meaningless or ignored, with opportunities lost and ethical issues hidden in an uncritical acceptance of the status quo. This process of bringing conceptual clarity has been alluded to in the philosophy of wellbeing as moving from “thin27” generalized description, to the “thick” description in specific contexts. From the synthesis of the two branches of literature, of sustainability, and wellbeing, four lenses fundamental to sustainable wellbeing are surfaced: the framing of growth and change (for flourishing wellbeing and natural world); social justice (in poverty and equity); the ethics of freedom (and how it is balanced); and the value of nature (intrinsic and instrumental).

The Framing of Growth and Change: For Flourishing Wellbeing and Natural World

Growth and change are defining phenomena of human wellbeing, and of the natural systems that underpin sustainability. Since the industrial revolution, exponential growth in the global economy, and in human population, have exerted increasing pressure on natural systems. More specifically, the spread of higher material consumption amongst the affluent is a “mega-driver” of global resource use and environmental degradation (Assadourian, 2010; Häyhä et al., 2016). This path of pursuing human wellbeing, through a constellation of proliferating consumerism, economic growth and increasing inequality, has driven “over-consumption” (Fleurbaey et al., 2014). The resulting damages, to human wellbeing and ecosystems, have defining implications for the categories that follow in section Key Lenses to Assist Integrating Sustainable Wellbeing -equity, freedom, and nature. Yet a continuation of these historically observed development paths is not inevitable. Following from “systems change” theory (Holling et al., 2002), alternative forms of growth, accumulation, restructuring, and renewal are possible in people-nature systems. In keeping with systems change theory, alternative development paths could be framed by a flourishing of a holistic and integrated sustainable wellbeing, embracing relationships and harmony, within and across individual, society and nature. The framing of “flourishing” has been alluded to as fundamental to integration of sustainability and wellbeing (Ehrenfeld and Hoffman, 2013; Painter-Morland et al., 2017) while James (2017) describes sustainability as fundamental to human flourishing itself28. Rather than economic growth and consumption, a flourishing of a sustainable wellbeing offers a transformative reframing of growth and change.

Social Justice: In Poverty and Equity

Social justice remains a dominant concern of sustainability, from the framing of needs in Brundtland [World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED), 1987], to discussions of Rawlsian justice within and across generations in Anand and Sen (2000). In contrast, applied wellbeing has frequently shorn itself of these considerations, in search of a nominal “objectivity.” As wellbeing includes normative assumptions and constructs, this entails major ethical concerns (Alexandrova, 2017). Wellbeing aspirations cannot be described as a replacement for income, the meeting of needs or equality in general. Nevertheless, the ability to live well, and physical and mental health are important to all people, including those in poverty, and can be preventative of pathology (Lyubomirsky et al., 2005; Huppert, 2009), while inequality is also known to markedly affect subjective wellbeing (Fleurbaey et al., 2014). How wellbeing is actually applied is therefore of great importance, so that it does not become a smokescreen to avoid addressing inequality and poverty (Hanratty and Farmer, 2012; Jenkins, 2016), or the necessary ethics of social justice encompassed by sustainability. In practice, a flourishing wellbeing description needs to also encompass provisions for poverty and equity.

The Ethics of Freedom: And How It Is Balanced

The ethics of freedom and autonomy return repeatedly in the ethics of wellbeing, as the imperative of freedom to determine what is the “good life,” through individual autonomy, and also to choose the strategies to pursue it. Oft-repeated by thinkers such as Sen, this imperative led to silence in capability theory on further description. Yet freedom is practically and ethically limited by negative freedom (Deneulin, 2009). Sustainability science attests that the economic freedoms of the wealthy -and related power dynamics- increasingly foreclose the options of the majority, and of future generations, while consuming the natural world. If freedom is taken as an absolute, then the “commodity fetishism” criticized by Sen (1984), is replaced by “freedom fetishism,” that serves the affluent and powerful. This prompts the equity-related question of “freedom for whom?” and elicits consideration of more than “living well individually,” but “living well together” (Deneulin and McGregor, 2010). Achieving consensual definitions can be supported by public and expert deliberation in specific geographic and cultural contexts (Alexandrova, 2017). Practical responses to the autonomy problem include: beginning with “thinner” more universal descriptions; delivering participation when refining “thicker” descriptions in specific contexts; applying stringent anti-paternalism conditions; and also in practice, the balancing of freedoms and of social justice through institutions, public policy, markets, and cooperative arrangements.

The Value of Nature: Intrinsic and Instrumental

Sustainability science has shown the critical instrumental value of ecosystems to human wellbeing, across scales and time, and yet this is frequently divorced from consideration of wellbeing. Often categorized as “ecosystem services” [Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA), 2003] and reflected in “planetary boundaries” (Steffen et al., 2015), sustainability science describes critical natural stocks that must be maintained for humanity (Neumayer, 2010). An important ethical distinction occurs in “anthropocentric” or human-centerd value, and “ecocentric” value, where nature is framed by its own worth (Washington et al., 2017), arising in indigenous philosophies as “Mother Earth.” Díaz et al. (2015) note that a comprehensive and inclusive approach, across stakeholders, knowledge systems and worldviews, necessarily requires considering more than the instrumental or relational value of nature to human wellbeing, but inclusion of its intrinsic value29. Alexandrova (2017) noted the dangers of sneaking controversial values into wellbeing, such as ignoring the place of social justice, and how this occurs in practice through the imposition of values, or inattention to their implications. This concern is equally valid in sustainability science, with major risks and ethical concerns, when an exclusive normative value of anthropocentrism is hidden. In response, Washington et al. (2017) discuss an ecocentrism that accepts humanity as part of nature, with both the power and responsibility to respect the web of life, and heal the vast damage to nature already evident.

Conclusion

The unfolding damage to the natural world, to planetary boundaries and risks to climate, require responses based not just on production efficiency and “green consumerism,” but prompt fundamental reconsideration of wellbeing and sustainability. These primary global policy priorities are inextricably linked, yet the place of wellbeing in sustainability, and vice versa, remains underappreciated. Despite considerable overlap, they are invariably conceptually isolated. Sustainability and nature are rarely part of discussions of the social sciences of wellbeing. On the other side of this coin, in the concept of SD, the articulation of needs and wellbeing remains vague. Where limited integration has been attempted, it generally places the reductive individual of needs and preferences on one side, and the distant scale of the global environment on the other. Ambiguity in the concept of SD has had some procedural advantages, particularly at the global level, allowing freedom of definition across diverse circumstances, and has facilitated a unified political commitment. However, continuing to reproduce a lack of clarity at the applied level is at odds with providing wellbeing and sustainability in practice. Despite the imperatives, this receives little attention, creating major policy blind spots. This neglects opportunities to achieve win-wins and manage trade-offs, and puts wellbeing and sustainability at increased risk of failures. Reproducing the status quo also hides substantial ethical issues, vis-à-vis social justice and the value of nature.

This article has reviewed the major contemporary accounts of human wellbeing, synthesized with the frontier of knowledge in sustainability. It highlights that although many wellbeing accounts provide partial insights, these are often indirect or subject to limitations as descriptions of wellbeing. In contrast, the objective list accounts, occurring across a variety of disciplines, are more direct in describing a holistic human wellbeing. These multidimensional accounts are strongly supported, can provide improved conceptual clarity, and show notable overlaps and complementarity. Choosing the dimensions of the list involves conceptual and value judgements in specific contexts, a process that can be assisted by voluminous theory and evidence, and by deliberation through public and expert participation. A robust conclusion is the importance of the “relational” dimensions, in which social relationships and society are central, but with relationships to nature and SD as yet largely overlooked.

Through synthesizing wellbeing with sustainability, a unified concept of “sustainable wellbeing” can be advanced. This requires integration, from the individual locus dominant in wellbeing, to interrelated environmental (nature-ecosystems) and human systems (society-economy). It is reflected in emerging sustainability science, on how relational values such as care, and relational thinking, can animate stewardship action (West et al., 2018). The synthesis surfaces four lenses fundamental to sustainable wellbeing: the framing of growth and change -for a flourishing wellbeing and natural world; social justice -in poverty and equity; the ethics of freedom -and how it is balanced; and the value of nature -instrumental and intrinsic. Deepening integration can be assisted by: enumerating the contribution of nature in wellbeing; enriching the conception of flourishing wellbeing in sustainability; recognizing the central role of society as interconnected system; surfacing both the intrinsic value as well as function of nature; and also by further analysing links between wellbeing and sustainability, including synergies and tradeoffs.

Beyond conceptual discussions, sustainable wellbeing has potential major significance in applied sustainability settings, for the framing of policy and politics and of environmental assessments, as it is substantial to the transformations required in the 21st century. Technological transitions, through efficiency and technological change, have come to define much sustainability efforts, and while necessary, this is known to be insufficient, requiring sustainability transformation (Grubler et al., 2018; Kirby and O'Mahony, 2018). Transformation paths are more fundamental, and are recognized at the frontier of knowledge, as a sustainable development path: (i) to surface values; (ii) reconceptualise development goals; and, (iii) to design and implement strategy and policy that embrace synergies and learning (Fleurbaey et al., 2014). Consequently, sustainable wellbeing has broad potential for use, from conceptual framing and analytical scenarios, to designing systems and policy innovations. This could include reanalysis of over-consumption, a defining characteristic of our development paths, linked to our conception of wellbeing, which continues to fundamentally overwhelm all efforts toward sustainability. Collectively, these are conceptual and strategic policy processes that acknowledge complexity, but also recognize major opportunities for win-win outcomes (Fleurbaey et al., 2014; Rogelj et al., 2018), which emerge by transdisciplinary integration to uncover the synergies. The IPCC have been at the forefront of recognizing the importance of the conceptualisation of sustainable wellbeing. In the Fifth Assessment Report, Fleurbaey et al. (2014) noted that achieving sustainability can be most strongly influenced by decoupling wellbeing from economic growth and consumption. In the chapter, on “Sustainable Development and Equity,” the Panel went on to note that this requires reconceptualising development, to prioritize wellbeing and sustainability, and the related synergies that can be achieved.

This iteration of Frontiers in Sustainability, addresses the research topic of “Sustainable Consumption and Care.” Through embracing the place of care, and relational thinking, in a sustainable wellbeing that integrates society and nature, pathways and lifestyles that decouple from over-consumption can be articulated. This article has demonstrated, that empowering a transformation, for flourishing individuals, society and natural world, demands reconsideration of “development,” from economic growth and consumption as means, to wellbeing and sustainability as ends.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

The maximizing well-being minimizing emissions MAXWELL project leading to this article has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie Grant Agreement No. 657865.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

Sincere thanks to Jyrki Luukannen, Iana Nesterova, and to the reviewers, for useful comments on earlier drafts. Thanks also to Marc Fleurbaey, Tuula Helne, Tuuli Hirvilammi, Rob Socolow, Ortrud Leßmann, Paul James, Jari Kaivo-oja, Roger Crisp, Workineh Kelbessa, Stefano Bartolini, Chukwumerije Okereke, and James Juniper, amongst many discussants in the years leading up to this article.

Footnotes

1. ^This is an internationally agreed guiding principle adopted by heads of states and governments in the 1992 Rio Declaration (Principle 3), and reaffirmed at 2012 UN Conference on SD.

2. ^“Well-being for all” is placed at the core of an ecologically safe and socially just space for humanity, including health and housing, peace and justice, social equity, gender equality and political voices, and alignment with transformative social development and the 2030 Agenda of “leaving no one behind” [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 2018].

3. ^A major distinction is adopted between intrinsic values and anthropocentric values, both of which have existence value and future-oriented value.

4. ^Defining good quality of life as: “A perspective on a good life that comprises access to basic materials for a good life, freedom and choice, health and physical well-being, good social relations, security, peace of mind and spiritual experience” (Díaz et al., 2015).

5. ^Choi and Pak (2006) provide useful distinctions of multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, and transdisciplinary, as additive, interactive, and holistic, respectively. In discussions of SD, Munasinghe (2002) and Halsnæs et al. (2007), emphasize that a holistic transdisciplinary meta-framework is necessary for SD. In terms of wellbeing, Rojas (2009) recommended that it requires a transdisciplinary, or least interdisciplinary approach (see also Describing Multidimensional Human Wellbeing).

6. ^The “Easterlin paradox” arises from a body of literature finding little or no relationship between subjective well-being and the aggregate income of countries, but within countries, people with more income are happier (Easterlin, 1973). These insights have been used to question whether economic growth should be the primary goal of development.

7. ^By material resources in having, by how people relate to each other in loving and by what an individual is and what he or she does in relation to society in being.

8. ^Subsistence, Protection, Affection, Understanding, Participation, Idleness, Creation, Identity, and Freedom. See Table 1.

9. ^In large multi-country study Tay and Diener (2011) examined the association of needs fulfillment and subjective well-being (SWB), finding that needs are indeed universal, with life evaluation most associated with fulfilling basic needs, and positive feelings associated with social and respect needs. Kingdon and Knight (2006) found that basic needs of education, health, employment and living conditions, are statistically significant determinants of happiness.

10. ^The capability approach involves two key terms of “functionings” and “capability sets,” where functionings are described as the doings or beings of an individual, such as material consumption, health, and level of education. These can then be described by a functioning vector which an individual can choose to value (Sen, 1999). A capability set, is the set of potential functioning vectors that an individual can obtain, where functionings are achievements, and capabilities are opportunities.

11. ^While functionings may be more straightforward, measuring capabilities as pure potentialities are not. In addition, attaching an appropriate system of weights is problematic.

12. ^According to a “politically liberal” approach, the CA is required to respect individuals' sovereignty, by ceasing to evaluate advantage, and support removing unfreedoms and providing general purpose freedoms. On the other hand, a “perfectionist” approach needs to specify and justify its theory of value. See Wells (2013).

13. ^Sachs (2016) refers to religious and secular traditions to highlight six dimensions of happiness: mindfulness; consumerism; economic freedom; the dignity of work; good governance and social trust.

14. ^The “experience machine” is a common theoretic objection to the hedonistic view that only pleasure contributes to wellbeing. Nozick (1974) attempts to show that there is something of value other than pleasure, by imagining a machine that could give us whatever pleasurable experiences are desired. This prompts the question, would we prefer the machine to real life?

15. ^“Flourishing” in psychological wellbeing may be defined variously as fulfillment, purpose, meaning, or happiness (Horwitz, 2002). The influential work of Keyes (2002) incorporates the main components of emotional, psychological, and social well-being.

16. ^Engagement is equated with “flow,” as a state characterized by intense absorption in one's activities (Csikszentmihalyi, 1997).

17. ^“Harmony,” the most frequent subcategory within the psychological definitions of happiness, included the components of inner peace, inner balance, contentment, and psychophysical well-being (Delle Fave et al., 2016).

18. ^Delle Fave et al. (2016) discuss the importance of harmony and balance in happiness across all countries, while noting that there are cultural and age related differences in the degree of identification of happiness with high arousal positive affect (HAP: excitement, euphoria, enthusiasm) and with low arousal positive affect (LAP: serenity, peacefulness, tranquility).

19. ^Psychological adaptation can occur to some changes in objective life conditions. It can also occur for health changes that affect our capabilities (Schroeder, 2016).

20. ^Noting that an elaborated account of preference satisfaction and desire is not relevant, as “satisfaction” and “desire” are themselves the ‘dimensions' of interest in these approaches.

21. ^Aristotle is often considered the archetypal objective-list theorist (Angner, 2016).

22. ^The holistic psychological science of wellbeing includes physiological, psychological, cultural, social, and economic determinants (Huppert et al., 2005).

23. ^Delle Fave et al. note the importance to the psychology of wellbeing of Baumeister's characterisation of humans as “cultural animals” (Baumeister, 2005). Despite differences in contents of goals and meanings across cultures, in this characterisation, humans pursue goals, and search for meaning in life events, in interpersonal relationships and in daily activities.

24. ^As per the review of Halsnæs et al. (2007), sustainability is now perceived as an irreducible holistic concept, where economic, social, and environmental issues are interdependent dimensions that require a unifying framework.

25. ^This theory is based on the idea that systems of nature and human systems, as well as combined human and nature systems and social-ecological systems, are interlinked in never-ending adaptive cycles of growth, accumulation, restructuring, and renewal within hierarchical structures (Holling et al., 2002).

26. ^In the context of wellbeing measurement, Alexandrova (2017) describe the task as involving “mixed claims,” noting concerns that this can import implicit views. This involves a danger of paternalistic coercion, by excluding what citizens value, in mutual trust, sustainability of lifestyle and justice.

27. ^“Thinner” descriptions tend to be more abstract, objective, and universal, while “thicker” descriptions are more detailed in a particular individual or cultural context. For further discussion see Grix and McKibbin (2016).

28. ^James (2017) describes the “central capacities” for a flourishing social life in: vitality; relationality; productivity; and sustainability.