94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain., 10 March 2022

Sec. Sustainable Organizations

Volume 3 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frsus.2022.799359

Environmental degradation is a complex global challenge requiring the urgent attention of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which are collectively responsible for a large proportion of global pollution. For those SMEs who are still thinking about sustainability at the level of the organization and reducing its environmental damage, there must be an immediate shift in SME strategy and operations to consider planetary systems and practices that can regenerate ecosystems critical for the business's success. Responding to this urgent need, the authors were keen to identify how SMEs could move from “doing less bad” to “doing more good,” as a critically needed shift toward “regenerative business practice.” Using two case studies of Australian manufacturing sector SMEs already self-identified as regenerative business practices, their transition pathways and current operations were explored for insights and lesson learning that could be used to empower other SMEs. Collected interview data revealed three themes of priority during the two SMEs' journeys: (1) Organization and Nature conviviality; (2) Organizational freedom to innovate; and (3) Organizational innovative outlook. The SMEs' experiences were also explored in relation to an “Action Framework for Regenerative Business” developed by the authors. The framework draws on Stewardship Theory together with a set of “Principles and Strategies of Regenerative Business” for SMEs to consider their current operations and identify opportunities for their next steps accordingly. Such directed actions are imperative to move away from just “reducing pollution” to “restoring planetary systems,” demonstrating truly responsible consumption and production. Within the framework the authors add “advocate” to the existing stewardship roles of “doers,” “donors” and “practitioners,” which acknowledges the importance of this role in enabling SMEs to shift practices; in this case to regenerative business practice.

Small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) have long been responsible for around 70 per cent of the world's pollution (Hillary, 2000; Revell et al., 2010; Aboelmaged and Hashem, 2019), and nearly 17 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions (Berners-Lee et al., 2011; Quintás et al., 2018). Over the last two decades there has been increasing awareness about the need for standardized methods and tools to limit resource consumption, reduce emissions and prevent pollution, including through the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (Kerr, 2006; Kolk, 2008; Adeola et al., 2021) and the International Standards Organisation (ISO) environmental and other management systems (de Junguitu and Allur, 2019). Approaches have included for example industrial ecology (Erkman, 1997), “Sustainability 3.0” (Beatley, 2009), the ideal corporation (Van Marrewijk and Werre, 2003), restorative business (Heyes et al., 2018) and circular economy (Geissdoerfer et al., 2017). While there are standout success examples for each of these, for the majority of SMEs, sustainability efforts have been focused on compliance—managing environmental risk and reducing environmental harm—and enhancing reputation and competitiveness in the market (Wright and Nyberg, 2017; Caldera et al., 2019a).

Over the last decade it has become increasingly clear that more substantive and transformative change will be necessary in order to adequately halt and reverse trends in environmental pollution and degradation (López-Pérez et al., 2017). Furthermore, regenerative business practices are critical to create a circular—not linear—economy, to integrate humans as full participants in planet's cyclical process of life (Raworth, 2017; Klomp and Oosterwaal, 2021). Such discourse has also arisen in considering “shared value” as described by Porter and Kramer (2011) where organizations focus on profits that create societal benefits rather than diminish them.

Precedents exist where SMEs have materially improved the health of the environmental systems within which they operate (Simpson et al., 2004; Sanford, 2016; Westman et al., 2018). “Corporate Sustainability” has emerged as an alternative to traditional, short-term, profit-oriented methods to manage organizations by balancing economic, environmental, and social issues holistically in the present and for future generations (Lozano et al., 2015). Six criteria were identified more than two decades ago for corporate sustainability, namely: eco-efficiency, socio-efficiency, eco-effectiveness, socio-effectiveness, sufficiency and ecological equity (Dyllick and Hockerts, 2002). However, the dominant understanding of business sustainability still emphasizes the organization and its business case, seeking strategies for less harmful social and environmental practices—i.e., “doing less bad”—to achieve competitive advantage rather than “doing more good” (Desha et al., 2010).

There is a substantial set of literature regarding sustainable business practice, considering a range of pathways for addressing environmental performance and social responsibility (Lawrence et al., 2006; López-Pérez et al., 2017; Caldera et al., 2019b). Stewardship Theory (Davis et al., 1997) is a common foundation for many of these studies (López-Pérez et al., 2018), which provides a theoretical lens to analyze sustainable business practices. There is also emergent research in the use of a systems approach to generate improved business strategies from the logic of social-ecological systems (SES) and regenerative development, described by Hahn and Tampe (2021). In this “regenerative business practice” research, taking a systems approach means to conceptualize business sustainability in terms of enhancing, and thriving through SES health in a co-evolutionary process to address “doing more good.” It draws on “regenerative sustainability” and “regenerative development” scholars' research in learning from the discipline of ecology, using living systems theory and systems thinking to inform built environment problem solving (du Plessis, 2012; du Plessis and Brandon, 2015; Robinson and Cole, 2015).

Building on discourse into why it is critical to shift to regenerative business practice, and appreciating the current collective impact of SMEs on planetary health, the authors asked, “How can SMEs transition to regenerative business practice?” This included firstly investigating the characteristics of “regenerative SME operations” (i.e., SMEs already conducting regenerative business practices) and then exploring how these businesses shifted their practices. The authors focused on two in-depth case studies manufacturing SMEs in their region of residence, which was a pragmatic response to ensuring physical proximity of the study for face to face interviews, and acknowledging the existing cluster of self-nominated regenerative businesses in Southeast Queensland (Australia). During the analysis of the data, an extant literature review then revealed a new paper that synthesized the discourse of regenerative business practice (Hahn and Tampe, 2021). Their “Principles and Strategies of Regenerative Business” were subsequently used to evaluate the case study findings.

This paper begins with an introduction to the theoretical lens used in the study, drawing on stewardship theory” (Davis et al., 1997), regenerative sustainability (du Plessis, 2012; du Plessis and Brandon, 2015) and regenerative development (Holden et al., 2016). This lens was used to select the case studies, shape the interview questions and to evaluate the case study findings. A paper by Hahn and Tampe (2021) presented two principles and three strategies of regenerative business, which guided the interpretation of the findings of our study. This study provides the restore-preserve-enhance scale for regenerative business strategies reflecting a continuum of strategies for regeneration.The case study method was used to probe and generate in-depth, rich, contextualized insights. Collected interview findings are presented using themes constructed from the initial theoretical review, and evaluated with regard to the enhanced theoretical lens. The authors propose a new “Action Framework for Regenerative Business” to support SMEs' transitions to regenerative business practice, immediately informing strategic business plan renewal and shifts in operational goals. The following sections present the analysis of key literature, the methodology, findings, and framework discussion.

This section presents the theoretical literature underpinning the research into regenerative business practice, comprising the established constructs of stewardship theory, regenerative sustainability and regenerative development.

Stewardship theory describes a model of a human based on the notion of being a steward, “whose behaviour is ordered such that pro-organisational, collectivistic behaviours have higher utility than individualistic, self-serving behaviours” (Davis et al., 1997). It centers on the role of people and networks in pursuing and achieving goals of environmental protection and preservation within an organization. Furthermore, companies have a moral commitment to protect and respect wider society and the environment, which is separate from their fiduciary obligations. According to Roberts and Feeley (2008), planetary stewards can be classified into three important roles for any given cause (goal). This includes “doers” who work by taking action, “donors” who financially assist, and “practitioners” who work day-to-day to enable and direct stakeholders such as governmental agencies community groups, and organizations in the supply chain.

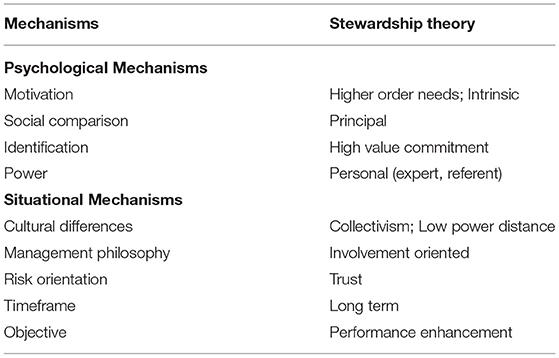

Within any given “stewardship relationship,” there will be emphasis on the higher order needs of Maslow's hierarchy (Maslow, 1970), on Alderfer's growth need (Alderfer, 1972), and on the achievement and affiliation needs of McClelland (1970). Stewardship theory describes four psychological and five situational mechanisms that are exhibited in an organization, which helps individuals and groups to align their goals with their organization's success in being a planetary steward. These are summarized in Table 1 and discussed below.

Table 1. A summary of stewardship mechanisms drawn from Stewardship Theory (Adapted from Davis et al., 1997).

For example, within the psychological mechanisms, “motivation” points to an organizational stewardship focus on intrinsic rather than extrinsic rewards, including growth, achievement, affiliation, and self-actualization. Employee roles and responsibilities are shaped by these intrinsic, intangible reward structures, which motivate individuals to pursue stewardship goals on behalf of the organization. Within the situational mechanisms, “cultural differences” points to a stewardship focus on collectivism wherein the individual employee identity is defined as belonging to a part of the larger group. One's group memberships outside the workplace (e.g., family, university) are also important statements of identity and achievement. Collectivists have a very positive attitude toward harmony in groups, avoiding conflict and confrontation. Within this culture there is low power distance which means inequalities are minimized, independence of the less powerful is valued and encouraged (Hodgetts and Luthaus, 1993).

The focus of stewardship theory on key actors and their roles can help to understand how employees can shift business practices within the system of “organization.” The adoption and diffusion of innovation within a system relies heavily on the roles and influences of agents. Stewardship theory aligns well with regenerative concepts of net positive performance, mutually beneficial outcomes and whole systems thinking (Nan et al., 2014).

In recent decades, the scale of environmental pollution and degradation has become more widely understood, and negative trends have highlighted the inadequacy of existing approaches to improving environmental performance due to its primary focus on damage reduction. The term “regenerative development” is based on the premise that regeneration “provides a foundation for a sustainability paradigm that is relevant to an ecological worldview” (du Plessis, 2012, p. 7). It has been used to describe a holistic approach that goes beyond “sustaining,” to improving the resilience and health of the environment through anthropogenic activities (Cole, 2012; Howard et al., 2019).

Regenerative sustainability has been well-researched in urban planning and the built environment contexts. This approach is being discussed and enabled within some sectors such as design and construction services in the built environment sector (Birkeland, 2002; Cole, 2012; Pedersen Zari and Hecht, 2020), urban development (Perales-Momparler et al., 2015), and design and agriculture (Duncan, 2016). Regenerative development seeks to generate positive environmental and social benefits of development (Birkeland, 2002; Rahimifard et al., 2018), applying a systems-thinking approach to create positive and mutually beneficial feedback loops between physical, natural, economic, social/community, and human capital. The goal is to generate net positive performance outcomes for social and ecological systems (du Plessis, 2012; Dake, 2018).

It is well-understood that regeneration “cannot be well without an understanding of the feedback effects across nested systems” (Williams et al., 2019, p. 1), wherein enhancing practices seek to identify leverage points across different scales to improve the adaptive capacity of socio-economic systems (Meadows, 1999; Etzion, 2018). It extends upon sustainability concepts of intergenerational equity (positioning current development in a way that retains the ability for future generations to meet their own needs), proposing that it is in fact necessary to foster development in a way that supports equitable, healthy, and prosperous relationships among built and living systems (Dake, 2018). Co-creative partnerships with nature enables cultivating relationships to provide both life-support and life-enhancing conditions for the global human community within a healthy eco-system (du Plessis, 2012, p. 19; Folke et al., 2010; Zhang and Wu, 2015). Regenerative systems require the capacity to function inside an ever changing process, with a complex web of reciprocal exchanges that generate multidirectional benefits, yet where exchanges are often indirect and non-equivalent (Mang and Haggard, 2016).

Regeneration provides a foundation to reconceptualize business sustainability toward regenerative business, addressing the challenges in relying on a systems approach which has been somewhat undermined by the “business case for sustainability” and associated commercial logic at the organizational level (Whiteman et al., 2013). Regenerative business is defined instead at the level of ecosystem, as “businesses that enhance, and thrive through, the health of socio-ecological systems (SES) in a co-evolutionary process” (Hahn and Tampe, 2021, p. 454).

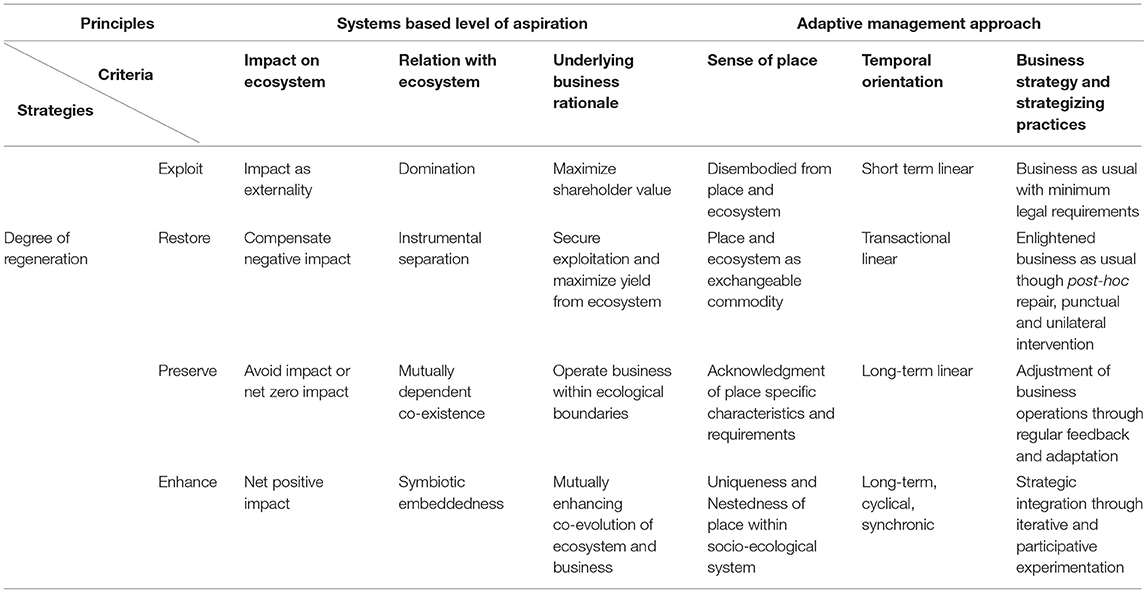

In conceptualizing business sustainability in terms of regenerative business, Hahn and Tampe (2021) distilled two SES related fundamental principles. The first principle of “systems-based level of aspiration” calls for the objectives of business activities to be derived from the perspective of the SES into which the business activity is incorporated. This principle reflects that, from a systems perspective, the finality of business sustainability is not the sustainability of a single business entity, but the sustainability of overarching SES that enable and constrain human economic activity (Grumbine, 1994; Hahn and Figge, 2011; Starik and Kanashiro, 2013; Bansal and Song, 2017). The second principle of “adaptive management approach” calls for the management approach to be adaptive, to be commensurate with the characteristics and the complexity of SESs. Here adaptation means enabling, “the system to better cope with, manage or adjust to some changing condition, stress, hazards, risk, or opportunity” (Smit and Wandel, 2006, p. 282).

To operationalize the goal of regenerative business, Hahn and Tampe (2021) present three regenerative strategies of “restore,” “preserve,” and “enhance” beyond “exploit,” as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Principles and criteria of regenerative business (extracted from Hahn and Tampe, 2021).

Restoration—i.e., returning to a previous or original state (Mang and Reed, 2012; Morseletto, 2020)—relates to a comparatively low level of aspiration, optimizing yield from ecosystems where, for example, natural resources are exploited. Preservation is more integrative as it encapsulates the relationship of business activity with SES as a mutually dependent co-existence rather than a restoration of damage. Preservation also demonstrates in business models the limited carrying capacity of SES. Enhance strategies are about the ways in that a business “can be a catalyst for positive change within and add value to the unique ‘place' in which it is situated” (Robinson and Cole, 2015, p. 135). Enhance aims to improve the conditions for life in SES (du Plessis and Brandon, 2015), using a systems approach to aim for net positive impact on SES (Birkeland, 2002; Mang and Reed, 2015), improving the adaptive, life-enhancing capacity of SES (du Plessis and Brandon, 2015). Enhance strategies understand the relationship between business activities and SES as symbiotically embedded (Marcus et al., 2010). In doing so, it reinforces the appreciation that businesses exist not as siloed entities but as integrated components of complex socio-eco-technical systems (Markolf et al., 2018).

In summary, regenerative business practices are critical to create a circular economic system and to enable humans to contribute to earth's cyclical process of life. Regenerative economic approaches are sustainable for both society and the planet in the long term (Raworth, 2017; Klomp and Oosterwaal, 2021). However there is limited research that focusses on how small and medium enterprises can engage in regenerative business practice. Within this context this study addressed the research question, “How can SMEs transition to regenerative business practice?”.

The study followed an interpretive, case study approach due to the nature of research questions and previous research studies as outlined below (Walsham, 1995; Klein and Myers, 1999). A literal replication approach was adopted where similar SME settings were chosen (Yin, 2009), comprising in-depth case studies. The manufacturing sector was selected considering its significant impact on environmental issues including resource and energy consumption, and emissions (Kek and Kandasamy, 2018), with “regenerative business operations” selected as the unit of analysis (Caldera et al., 2019a). The study focused on a “cluster” (i.e., a group within the manufacturing sector) of SMEs in Southeast Queensland, Australia who were part of a professional manufacturing network in Queensland. This enabled the research team to have ready access to employees and a high-level of on-site engagement. This method was deemed appropriate as it has the ability to probe further into the phenomena and generate more in-depth, rich, contextualized insights (Walsham, 2006) and was not aimed to develop a representative sample of the population of SMEs (Yin, 2009).

The resultant study allowed meaningful exploration and consideration of the many facets of how organizations have shifted to regenerative business practices. Such studies are important in the early phases of emerging practice areas, to inform discussions in how organizations can move from ad hoc, champion-based examples of a given goal can be reached, to successful goal outcomes being part of mainstream practice (López-Pérez et al., 2018). As such, this research provides a foundation for further investigation into generalizable trends, patterns and gaps across a wider sample. The following sections summarize the case study details (ethical approval reference QUT 1500000783).

Following an open invitation to the cluster to engage with the research project, several SMEs self-nominated to share their learnings for research purposes, to gain theoretical and managerial insights into the phenomena of “regenerative business practice,” to elicit compelling practical insights (Herriott and Firestone, 1983; Walsham, 1995). Case study selection was subsequently informed by five criteria following their use in previous academic research on SMEs business practice. Firstly, the SMEs should be in Southeast Queensland. Secondly, the business should comply with the Australian Bureau of Statistics defined criteria for SMEs. Thirdly the SMEs should represent the manufacturing sector. Fourth, the SME should have demonstrated leadership in sustainable business practice (i.e., recipients of national/ regional sustainability awards/accolades). Finally, the SMEs should have attempted regenerative business practice and consider their business practices advocates for nature as necessary stakeholder.

Compliance with the characteristics of SMEs defined by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (2015) include that the companies employ no more than 250 people. To identify these SMEs who have demonstrated leadership in sustainability, several methods were adopted: information gathered on their websites regarding awards and accolades; interaction with professional industry body for Queensland manufacturing businesses; and a preliminary exploratory study with a cohort of manufacturing SMEs in South East Queensland (Caldera et al., 2017, 2019b).

Two case studies satisfied the selection criteria. In both selected cases studies detailed interviews were conducted on site to validate information about business practices. The selection of two case studies within the same region also avoided major variations in regulatory and policy conditions.

The two case organizations have established regenerative business practice and their evidence offers different market contexts (i.e.: paint and mulch manufacturing), providing unique perspectives on regenerative development related transformation (Eisenhardt, 1989; Seidel et al., 2009). Firm-A—a manufacturer of innovative eco-paints and render products—had been recognized for their innovation inspired by nature, leadership and sustainable, regenerative business practices with a multitude of awards. Firm-B—a manufacturer of recycled mulch from urban food waste—provided an example of improving the health of people and place, and “closing the loop” through supplying product back to landscape yards to improve local soil conditions. They had also received a number of state and national awards and accolades.

Semi-structured interviews were used to collect data from the SME industry practitioners (Cassell and Symon, 2006), focusing on lesson learning about organizational shifts to regenerative business practice (Cole, 2012; Sanford, 2016). Key literature relevant to SMEs and regenerative business practice was used to develop the interview guide (Rubin and Rubin, 2011). Prompts were used to delve deep into the regenerative business phenomena (Yin, 2009). The interviews ranged typically between 1 and 1.5 h which were recorded digitally, with consent obtained from each participant prior to the interview. Publicly available information from each SME's website and hard-copy materials were also collected.

Interviews were undertaken across all levels of the organizational structure including managing directors, senior managers and operational staff involved in implementing regenerative business practices. The involvement of multiple informants provided multiple viewpoints for the phenomena. Initial questions were asked to establish the background context of the SME. Then, to probe into the regenerative business phenomena questions included, “What triggered your organisation to implement regenerative business practice?” and “What is the role of innovation/eco-preneurship in regenerative business practice?” (Appendix 1). After theoretical saturation was reached, in total there were 31 interviews conducted on-site for the two organizations. This includes 13 participants from Firm A (P1-P15) and 15 participants from Firm 15 (P1-P16). A summary of the SMEs and participants is presented in Table 3 (Caldera et al., 2019b).

It was evident that detailed information with specific examples about this transition was shared by key respondents (Managing Directors and Senior Managers coded as P1, P2, P3, P15 from Firm A and B) as they were instrumental in driving this transition and their lived experiences provided insights.

The audio-recorded interviews were manually transcribed and coded through the NVivo Pro (version 11) software. The transcripts were re-read three times before starting the data reduction process (Bandara, 2006). The Gioia methodology (Gioia et al., 2013) was adopted to initially analyze the data collected from interviews. The constant comparative method was adopted to cross-examine answers from different interviewees (Glaser and Strauss, 2009).

Data analysis involved five steps: (1) create initial codes while maintaining the integrity of first-order, informant-centric terms; (2) develop a comprehensive collection of first-order terms; (3) organize first-order codes into second-order, theory-centric themes using thematic analysis; (4) distill second-order themes into overarching theoretical dimensions, in the form of aggregated categories; and (5) assemble the terms, themes, and dimensions into a logical data structure (Gioia et al., 2013; Feng et al., 2021).

The thematic analysis to distill themes for each case (Braun and Clarke, 2006) was followed by a cross-case analysis of the two companies to synthesize themes that emerged across the cases (Yin, 2009; Creswell, 2013). Two authors participated in the coding process to mitigate potential bias in data analysis. There was a percentage agreement of 80 per cent, which is an acceptable inter-coder reliability rating (Pettigrew, 1990; Lombard et al., 2002; Silverman, 2013). The interview findings were also cross-checked with publicly available online information including biographies, brochures and published case studies, to minimize possible elimination of important information (Yin, 2009). This section presents the results of the case study analysis according to the data structure (Corley and Gioia, 2004) presented in Figure 1.

There was a strong nature narrative, and a human health narrative being used to drive “doing more good.” Nature was also used for direct inspiration in product manufacturing, and for inspiration in organizational management. The results are discussed for each of the three characteristics distilled from the analysis, i.e.,: “Organization and Nature conviviality,” “Organizational freedom,” and “Organizational innovative outlook.

Reflecting on the vocabulary used by participants, regenerative business practice was consistently perceived across the two firms as requiring an approach that connected with and related to the natural environment. Participants identified a company-wide desire to move to a bigger-picture relationship that considered Nature as friend; i.e., to be related to, and have an affinity with. The theme was subsequently termed “Organization and Nature conviviality,” recognizing participants' frequent personification of nature with a capital “N.” Table 4 presents a map of the findings, considering which of the stewardship mechanisms and regenerative business practice principles and strategies were evident in the interviews. The table contents are elaborated on in the following paragraphs.

For Firm-A, conviviality with Nature is embedded at the level of the company in a vision of “re-seek and develop.” This is a process whereby staff reflect on the ancient/ indigenous practices of sustainability and healthy practice, including learning to mimic nature in their choice of material and construction methods while still catering for modern demands. Through this practice, Firm-A adopted a “minimum intervention model” whole system approach (Example 1, Stewardship), which utilized optimal planet-benefiting technology to cater to contemporary market needs. In this case the SME was producing breathable, toxic free products to reduce landfill waste and wastewater treatment requirements—i.e., preserving water and land quality, avoiding treatment and future remediation. One participant emphasized how maintaining the health of people including employees and customers was of great concern, as was appreciating the interrelationships with the natural environment (Example 2, Stewardship and regeneration). The SME also focused on using natural raw materials for the health of people affected by their products (Example 3, Stewardship).

For Firm-B, conviviality with Nature was embedded in its holistic approach to increase utilization of urban waste that was perceived as “wrong time and place” materials (that has no further value to the owner), to “right time and place resources” that are good for people and planet. For example, their value recovery process of recycling and coloring transformed “wrong time and place pallets and crates,” into a compelling commercial “right time and place resource” which reduced waste to landfill (Example 1, Stewardship). The mulch also helped suppress weeds, retain moisture, reduce erosion and as it degrades, and add carbon to nutrient deficient soils, supporting carbon cycle improvements that help sequester greenhouse gas emissions (Example 1, Regeneration).

Senior decision maker participants across both SMEs referred to these regenerative practices as enabling them to connect the principles of a circular economy, leading to a competitive advantage. Several of these participants also perceived regenerative development as a market response as well as an opportunity. Pursuit of regenerative practices ultimately led to enhanced organizational capability that enabled the SMEs to engage in circular economy strategies by reducing resource inputs and waste through durable design, productive maintenance, re-use, and recycling. These SMEs did not place benefits to nature under some sort of performance gain but embraced it as the ultimate goal (Example 3, Regeneration).

Participants in both case studies commented on the freedom granted by their company to innovate, and encouragement to make mistakes and learn from them. This resulted in a theme of “Organizational Freedom,” which is also a methodology described by Frederic Laloux (Laloux, 2014). Table 5 summarizes the mapped Theme 2 findings, highlighting identified stewardship mechanisms and regenerative business practice principles and strategies.

A senior participant from Firm-A spoke directly to the importance of organizational freedom and how they were inspired by the principles of re-inventing organizations. A key lesson for Firm-A was that where conventional structures are removed, this creates space for other structures to emerge (Example 1, Stewardship and regeneration; Example 3, Regeneration). They reflected on the natural phenomena of “murmuration,” where a flock of birds fly in one direction, in the same pattern, without being led (Example 2, Stewardship). Senior management saw how this phenomenon resonated with desirable company behavior and so took measures to emulate this nature's practice and connect these learnings with the company culture (Example 2, Regeneration). They subsequently removed formal structures, bureaucracy, and rules, to create an organizational culture where employees could feel valued and free. For example, one participant operations management stated, “There is a lot of communication from the top management and we are valued” (P9, Firm B). Another participant recalled a Japanese proverb to explain this company's connection to nature-inspired problem solving, “When confronted with a problem always look for nature. I think it's really important, people can dismiss that, when you confront a problem first look to nature, that's the best way to do no harm” (P15, Firm-A). Another Firm-A participant commented on the need for situational leadership in a company with this type of arrangement, to recognize the right people and help them to grow (P3, Firm-A).

Participants from Firm-A (P1, P2, P3, P15) and Firm-B (P2, P3) reflected on the importance of having a strong innovative outlook, which imagined “what could be” for the future market place, considering co-evolution and co-benefits to people (business) and nature. Table 6 summarizes the mapped Theme 3 findings, highlighting identified stewardship mechanisms and regenerative business practice principles and strategies.

For Firm-B, participants were consistent in their reflections that a firm focused on innovation creates accelerates regenerative practice. For example, one participant provided two examples of mulching innovation, and food waste anaerobic digestion creating odorless food waste (Example 3, Regeneration). Firm-B participants spoke about shifting governmental requirements to enable regenerative outcomes, working together with soil scientists to test the composition of the innovative mulch solution to ensure the manufactured product adheres to the Australian Standard AS4454-2012 for composts, soil conditioners and mulches. There is clear evidence of these participants advocating for regenerative outcomes with extra effort and focus on creating healthy outcomes.

Senior managers of Firm-A and Firm-B perceived lean manufacturing as a way to “look up” and “look ahead,” to create possibilities for diversifying their business practices. For example, “Lean mediate[s] innovation in the organization. I think so. As it will formulate a framework, so we go from idea to activate the idea and actually market it” (P3, Firm-B). Another participant added, “What is good about integrating lean is that they could methodically address the non-value adding activities in their operations and get all employees involved, engaged” (P16, Firm-B).

The importance of innovation culture was reflected on by P2 of Firm-B, “I could say innovation culture is embedded in our business and it was done out of necessity. The employees are adjusting to change. Adjusting to how quickly it's happening. Get a system on board.” A production operator shared an example, “We use drone technology to take aerial photographs of the stock piles and remove unnecessary waste” (P10, FirmA). This sentiment was shared by another participant from Firm-B, “I definitely think there is a culture of innovation. I think we look at lean as a way stabilizing and securing how innovation is going on.” (P2, Firm-B).

For Firm-A, the innovation outlook was directed toward a specific knowledge area in the form of biomimicry principles. For example, “Biomimicry is the gold standard, we are looking at our clay building products and we look at how nature build things. [abridged] We see people have been using these [ideas] to build for [millennia]. It's healthy because nature [is] doing [it] like that to start with. So, it's healthy living. It is a good system; we can't argue with that.” (P1, Firm-A). Their focus on regenerative practice inspired Firm-A to use natural materials like lime, mud, clay and fibrous ingredients like straw, to create aesthetically pleasing and enduring buildings. Their efforts to re-invent the nature-based design is illustrated in their use of natural bamboo as an equally relevant architectural coatings that augments contemporary building design and construction. Such practices have created a competitive edge for Firm-A to sell their eco-efficient products to the consumer market providing new options for customers to choose from, ahead of demand. These details on eco-products were further confirmed from a review of the firm's website.

Considering the case study findings in light of the theoretical context presented earlier, there are a number of insights for how SMEs can shift the context for operating and enable workplace changes. This is presented in an “Action Framework for Regenerative Business” (Figure 2). Core considerations for SMEs are listed on the left-hand side, drawing on Stewardship Theory (Davis et al., 1997) and Regenerative Business Practice (Hahn and Tampe, 2021).

Presenting these two theories together shows how people within an organization can shift mindsets and place-based actions to pivot the organization from exploitation to restoring, preserving and enhancing planetary health. In “Organization roles” in Figure 2, an arrow passes between “business as usual” to “regenerative business practice” with the term “Advocates” as a fourth type of environmental steward. This new role extends the role typologies defined by Roberts and Feeley (2008). Advocates promote regenerative business practice, enabling a shift in the mindsets of doers, donors and practitioners during the transition beyond traditional environmental stewardship. Advocates seek regenerative development and build resilience, enhance eco system health and ability to thrive. Advocates drive regenerative business practices and change organizational practice to halt and reverse their negative environmental impacts and improve their systematic thinking. They are well aware of the interactions and interconnectedness to the natural ecological system will promote this thinking within the organization.

This study analyzed SME efforts related to regenerative business practice, after they had made the transition, to explore how they operated and how they could be emulated by others contemplating a transition. For Firm-A and Firm-B, the transition proceeded through connecting with nature, nurturing organizational freedom and ensuring an organizational innovative outlook:

• Within Theme 1 Organization and Nature conviviality, the regenerative strategies of preserve and enhance were visible, where participants in both firms discussed mutually dependent co-existence rather than just restoration of damage.

• Within Theme 2 Organizational freedom, participants of both firms spoke to the importance of engaging with supply chain and communities of practice. This included stewardship notions of trust, and regenerative concepts of potential and reciprocity.

• Within Theme 3 Organizational innovative outlook, participants spoke to the importance of organizations keeping up to date with leading edge thinking for regenerative sustainability and regenerative development, to enable stewardship ideals around value commitment and to improve the adaptive, life-enhancing capacity of their products.

Evaluating progress using Hahn and Tampe (2021) Regenerative Business Practice Principles and Strategies (Table 2), both firms' efforts result in a “degree of regeneration” in the realm of “Preserve” and “Enhance.”

This section discusses the case studies in relation to the framework for shifting to regenerative business practice, considering the theoretical and practical contributions of the framework, and limitations of the study that could be addressed through future research.

The findings provide insights into how regenerative business practice can be integrated within an SME's operations through an ‘action framework' for shifting to regenerative business practice (Figure 2). Firstly, the authors expanded the context of stewardship theory to include the role of “advocate.” Secondly, the authors connected the important mindset (psychological) and situational (place-based) strategies described by Davis et al. (1997) to be able to achieve the systemic and adaptive transition of an SME to a regenerative business practice as described by Hahn and Tampe (2021). Three strategies observed in the case studies are discussed in the following paragraphs.

1. Embedding a place-based and temporal appreciation of “system of systems”:

Regarding the regenerative business discussion by Hahn and Tampe (2021), both firms planned to run their business as a closed loop system, converting waste into resource streams. They engaged with whole system thinking in addition to ecosystem-based enquiry into how they could achieve co-evolution of ecosystem and business. Considering the work of Benne and Mang (2015, p. 42), both firms considered the “nested-ness” of local SES in a larger context, working through how their business operations—as a “small intervention” could influence the health and renewal of planetary systems. Both firms also took on long-term perspectives to consider ecosystem and societal interrelationships, enabling them to plan how they could influence long-term, lagged, and non-linear effects of human interventions in SES (Bansal and Song, 2017; Williams et al., 2017). In Firm-A, there was also a focus on iterative and continued consideration of indigenous methods and world view to inform future approaches. They reconnected through literature, local elders and knowledge holders, to the original place rituals which helped them to define and work toward restorative and regenerative practice.

The practices shared by Firm-A and Firm-B participants align with the current understanding that regenerative practices are iterative and procedural in that they are based on ongoing experimentation, reflective processes, and probing based on the feedback from SES complementing previous research on regenerative practice (du Plessis and Cole, 2011; du Plessis and Brandon, 2015; Williams et al., 2017). Using Stewardship theory language, the firms embedded performance enhancement objectives as opposed to only cost control. Within the language of Regenerative Practice, both firms considered their performance improvement goals through a complex systems lens, recognizing that such outcomes can be iteratively supported through continuously engaging with knowledge and innovation.

2. Restructuring to foster trust and engagement:

In terms of organizational structure, participants from both firms shared about deliberate efforts to remove hierarchies and empower individuals within their organizations. Both firms hired personnel or consultant support, to identify and speak to regenerative business practice opportunities—i.e., advocates of the “doing more good” behaviors that would lead to becoming a regenerative business. These actions directly address the psychological (mindset) mechanisms discussed in Stewardship theory, which recognizes the benefits of trust and employee involvement and engagement. For Firm-B this enabled them to adopt an involvement-oriented approach, the means of dealing with increased uncertainty and risk is through more training, empowerment, and ultimately trust in workers (Davis et al., 1997). For both firms, where uncertainty or complexity arise, they were addressed through greater training and empowerment of the individuals within the organization, rather than increased controls and restriction. Active and inclusive involvement of employees was considered critical by senior management in both cases.

The findings highlighted a strong tendency for both firms toward two-way learning and knowledge sharing; within each firm and also between the firm and connected ecological systems. They provide two inspiring examples of integrated systems of ecosystems and human society, with reciprocal feedbacks and interdependence. This fits within Stewardship theory language as enabling low power distances between individuals within the organization. Within the regenerative concept of nestedness, the two case studies demonstrate SMEs moving beyond the organizational context to appreciate the role of ecosystems and the opportunities for relationships between both.

3. Building agility muscles for meaningful work in rapidly changing markets:

Within the stewardship lens, the meaningfulness of work is derived through a personal responsibility for outcomes and a feeling of purpose as key drivers for individual motivation, and where individuals identify themselves in terms of their alignment with the organizations mission and objectives. For both case studies, meaningful work was a strong motivator, with an agreed organizational motivation to achieve regenerative environmental outcomes, that in turn fostered the development and growth of individuals within the organization who contribute to that broader goal—i.e., a mutual accountability for regenerative outcomes.

Firm-A and Firm-B both prioritized innovation cultures and their capacity to adapt and respond to change, toward improving conditions for life in socio-ecological systems. For the two SMEs, their actions are an interesting evolution of the stewardship mechanism of involvement-oriented management involving self-control and self-management, favoring agility, employee-motivated innovation and engagement with senior management. This was evidenced though the organizational freedom culture inculcated in Firm-A and training, empowerment, and ultimately trust in workers evidenced through activities in Firm-B. In supporting innovation cultures, there is an inherent need to recognize this complex web perspective of the “reciprocity,” wherein investment in one idea, innovation or initiative may not, in itself generate equal or greater return on investment. Instead, both Firm-A and Firm-B recognized the importance of supporting innovation over the longer term, with trust the overall, the investment of time, resources and energy would deliver benefits across the system.

While regenerative business practice is critical to build resilience, enhance eco system health and to improve ability to thrive, it is a complex shift from business as usual. Moving from the exploitive relationship into a regenerative relationship with the ecosystem can be achieved through different levels of aspirations. This means SMEs can aim to achieve regenerative strategies of “restore,” “preserve,” and “enhance” as a spectrum of opportunities toward the goal. Through this study it was evident that advocates are critical to enable this transition along with the appropriate mindset. Advocates drive regenerative business practices and change organizational practice to halt and reverse their negative environmental impacts and improve their systematic thinking. They are aware of the interactions and interconnectedness to the natural ecological system will promote this thinking within the organization.

Keeping this in mind industry practitioners can learn look through a lens of a whole system to identify where there is conviviality (affinity) between their organization and Nature. This opportunity for SMEs to be inspired by Nature can help SMEs to become sentient to more complex ecosystems changes and adapt to changes accordingly (Muisenberg et al., 2013). Furthermore, organizational freedom will reduce friction and enable a flow-oriented culture that can help industry practitioners to steer through the system and have clear, authentic communication between hierarchical and adaptive systems (Hooker and Csikszentmihalyi, 2003; Sharp, 2015). Having advocates on staff with appropriate psychological tools will help them to deal with the emotional labor associated with enabling this shift and creating psychological safety for decision makers.

The authors acknowledge that this research could be considered limited in terms of the sample size (Myers, 2013). To ensure the credibility of the research findings, four key guidelines were used. These guidelines include: recording the chain of evidence, using multiple data collection methods for corroboration (Glaser and Strauss, 2009; Yin, 2013), collecting data until theoretical saturation is reached (Strauss and Corbin, 1996), “explanation building” (Yin, 2013), using a case study protocol (Yin, 2013) and using theory to relate findings to literature (Klein and Myers, 1999). Regenerative business practice in SMEs demand deeper explorations and therefore future studies could investigate different tools SMEs could use to restore, preserve, and enhance the ecosystem. While these case studies help to establish recommended actions for SMEs, the next step would be to test the “Action Framework for Regenerative Business” in different industries and conduct field experiments to determine the level of influence organization roles have on degree of regeneration.

While many organizations will focus on change management issues such as gender equality, and health and safety, there is a critical need to shift to regenerative business practice to ensure the health and well-being of people and place. In this study provides a rich narrative of SME experiences in shifting to Regenerative Business Practices by addressing the research question of “how can SMEs transition to regenerative business practice.” Three key themes emerged from the two SMEs studied, providing a point of reference for other SMEs seeking to improve their performance. These include: Organization and nature conviviality; organizational freedom to innovate; and organizational innovative outlook. The findings of this research are immediately relevant for SMEs to guide renewal of strategic business plans and goals, and to inform how their organizations shift mindsets and actions accordingly.

For the two firms studied, the construct of “regenerative business practice” inspired them to slow, stop and then reverse their negative environmental impacts, then progressively positively influence their surrounding socio-ecological systems. Senior Management advocated clearly to promote regenerative business practice in their organizations, enabling staff at all levels to engage in regeneration in different degrees of restore, preserve and enhance. The many individual examples collectively propelled them from business as usual to a regenerative business practice.

The exploration of the two Southeast Queensland manufacturing SME case studies also helped to understand how theory connects with practice. This includes understanding how Stewardship Theory can continue to support improved planetary outcomes, with the addition of an advocacy role to pivot organizations in the direction of regenerative business practice, and some evolving context about the ways that roles may be enacted. It also includes immediate use of the recently published Regenerative Business Practice Theory, to holistically evaluate how an SMEs is currently performing, and opportunities for improving. The Action Framework presented in this paper provides a human—organizational map for navigating the shift with reference to these two theories.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the interview data are confidential. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to cy5jYWxkZXJhQGdyaWZmaXRoLmVkdS5hdQ==.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by QUT Ethics approval number: 1500000783. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

SC wrote the manuscript while incorporating the individual contributions. CD, LD, and SH helped to develop the framework, assisted with writing the manuscript, in particular the Abstract, Introduction, and Discussion. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The authors undertook an inductive process of inquiry that commenced with working with an industry-facing framework known as the Seven Arenas of Regeneration by Sanford (2016). The provocation provided by this framework informed the early development of the investigation and guided a practioner-relevant synthesis of opportunities for enabling regenerative business practice. The authors acknowledge Leith Sharp, for providing deeper insights on sustainability transformation through the Harvard's Executive Education for Sustainability Leadership program.

Aboelmaged, M., and Hashem, G. (2019). Absorptive capacity and green innovation adoption in SMEs: the mediating effects of sustainable organisational capabilities. J. Cleaner Prod. 220, 853–863. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.02.150

Adeola, O., Gyimah, P., Appiah, K. O., and Lussier, R. N. (2021). Can critical success factors of small businesses in emerging markets advance UN sustainable development goals? World J. Entrepreneursh. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 17, 85–105. doi: 10.1108/WJEMSD-09-2019-0072

Alderfer, C. P. (1972). Existence, Relatedness, and Growth: Human Needs in Organizational Settings. New York, NY: Free Press.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2015). Australian and New Zealand Standard Industrial Classification(ANZSIC). Available online at: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/1292.0.55.002. (accessed January 15, 2020).

Bandara, W. (2006). “Using Nvivo as a research management tool: a case narrative,” in Paper presented at the Quality and Impact of Qualitative Research: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Qualitative Research in IT & IT in Qualitative Research (Brisbane, QLD).

Bansal, P., and Song, H. -C. (2017). Similar but not the same: Differentiating corporate sustainability from corporate responsibility. Acad. Manag. Ann. 11, 105–149. doi: 10.5465/annals.2015.0095

Beatley, T. (2009). Sustainability 3.0. Building tomorrow's earth-friendly communities. Planning 75. Available online at: https://trid.trb.org/view/892159

Benne, B., and Mang, P. (2015). Working regeneratively across scales—Insights from nature to the built environment. J. Cleaner Prod. 109, 42–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.02.037

Berners-Lee, M., Howard, D., Moss, J., Kaivanto, K., and Scott, W. (2011). Greenhouse gas footprinting for small businesses—The use of input–output data. Sci. Total Environ. 409, 883–891. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.11.023

Birkeland, J. (2002). Design for Sustainability: A Sourcebook of Integrated, Eco-Logical Solutions. London: Earthscan.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualit. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Caldera, H. T. S., Desha, C., and Dawes, L. (2017). “Evaluating SMEs' relationships with ‘lean' and ‘green' thinking when aiming for sustainable business practice,” in Paper presented at the Proceedings of 18th European Rountable for Sustainable Consumption and Production (Skiathos Island).

Caldera, H. T. S., Desha, C., and Dawes, L. (2019a). Evaluating the enablers and barriers for successful implementation of sustainable business practice in ‘lean'SMEs. J. Cleaner Prod. 218, 575–590. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.01.239

Caldera, H. T. S., Desha, C., and Dawes, L. (2019b). Transforming manufacturing to be ‘good for planet and people', through enabling lean and green thinking in small and medium-sized enterprises. Sustain. Earth 2, 4. doi: 10.1186/s42055-019-0011-z

Cassell, C., and Symon, G. (2006). Taking qualitative methods in organisation and management research seriously. Qual. Res. Organ. Manag. 1, 4–12. doi: 10.1108/17465640610666606

Cole, R. J. (2012). Regenerative design and development: current theory and practice. Build. Res. Inf. 40, 1–6. doi: 10.1080/09613218.2012.617516

Corley, K. G., and Gioia, D. A. (2004). Identity ambiguity and change in the wake of a corporate spin-off. Admin. Sci. Q. 49, 173–208. doi: 10.2307/4131471

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. New York, NY: Sage publications.

Dake, A. (2018). Thriving Beyond Surviving: A Regenerative Business Framework to Co-Create Significant Economic, Social, and Environmental Value for the World ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. Available online at: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2279899858?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true (accessed May 20, 2019).

Davis, J. H., Schoorman, F. D., and Donaldson, L. (1997). Toward a stewardship theory of management. Acad. Manag. Rev. 22, 20–47. doi: 10.2307/259223

de Junguitu, A. D., and Allur, E. (2019). The adoption of environmental management systems based on ISO 14001, EMAS, and alternative models for SMEs: a qualitative empirical study. Sustainability 11, 1–17. doi: 10.3390/su11247015

Desha, C., Hargroves, C., and Smith, M. H. (2010). Cents and Sustainability: Securing Our Common Future by Decoupling Economic Growth From Environmental Pressures. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781849776370

du Plessis, C. (2012). Towards a regenerative paradigm for the built environment. Build. Res. Inf. 40, 7–22. doi: 10.1080/09613218.2012.628548

du Plessis, C., and Brandon, P. (2015). An ecological worldview as basis for a regenerative sustainability paradigm for the built environment. J. Cleaner Prod. 109, 53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.09.098

du Plessis, C., and Cole, R. J. (2011). Motivating change: Shifting the paradigm. Build. Res. Inf. 39:436–449. doi: 10.1080/09613218.2011.582697

Duncan, T. (2016). “Chapter 4.3 - case study: taranaki farm regenerative agriculture. pathways to integrated ecological farming A2 - Chabay, Ilan,” in Land Restoration, eds M. Frick and J. Helgeson (Boston: Academic Press), 271–287. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-801231-4.00022-7

Dyllick, T., and Hockerts, K. (2002). Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Bus. Strat. Environ. 11, 130–141. doi: 10.1002/bse.323

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 14, 532–550. doi: 10.2307/258557

Erkman, S. (1997). Industrial ecology: an historical view. J. Cleaner Prod. 5, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/S0959-6526(97)00003-6

Feng, Y., Papastamoulis, V., Mohamed, S. A., Le, T., Caldera, S., and Zhang, P. (2021). Developing a Framework for Enabling Sustainable Procurement: Research Report# 2. Perth: Sustainable Built Environment National Research Centre.

Folke, C., Carpenter, S. R., Walker, B., Scheffer, M., Chaplin, T., and Rockstrom, J. (2010). Resilience thinking: Integrating resilience, adaptability and transformability. Ecol. Soc. 15:art20. Available online at: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol15/iss4/art20/

Geissdoerfer, M., Savaget, P., Bocken, N. M. P., and Hultink, E. J. (2017). The circular economy – a new sustainability paradigm? J. Cleaner Prod. 143, 757–768. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.12.048

Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., and Hamilton, A. L. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: notes on the Gioia methodology. Organ. Res. Methods 16, 15–31. doi: 10.1177/1094428112452151

Glaser, B. G., and Strauss, A. L. (2009). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction publishers.

Hahn, T., and Figge, F. (2011). Beyond the bounded instrumentality in current corporate sustainability research: Toward an inclusive notion of profitability. J. Bus. Ethics 104, 325–345. doi: 10.1007/s10551-011-0911-0

Hahn, T., and Tampe, M. (2021). Strategies for regenerative business. Strat. Organ. 19, 456–477. doi: 10.1177/1476127020979228

Herriott, R. E., and Firestone, W. A. (1983). Multisite qualitative policy research: optimizing description and generalizability. Educ. Res. 12, 14–19. doi: 10.3102/0013189X012002014

Heyes, G., Sharmina, M., Mendoza, J. M. F., Gallego-Schmid, A., and Azapagic, A. (2018). Developing and implementing circular economy business models in service-oriented technology companies. J. Cleaner Prod. 177, 621–632. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.12.168

Hillary, R. (2000). Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises and the Environment: Business Imperatives. Austin, TX: Greenleaf Publishing.

Hodgetts, R. M., and Luthaus, F. (1993). U.S. multinationals' compensation strategies for local management: cross-cultural implications. Comp. Benelits Rev. 25, 42–48. doi: 10.1177/088636879302500207

Holden, M., Robinson, J., and Sheppard, S. (2016). “From resilience to transformation via a regenerative sustainability development path,” in: Urban Resilience, Y. Yamagata and H. Maruyama (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 295–319.

Hooker, C., and Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2003). Flow, Creativity, and Shared Leadership. Shared Leadership: Reframing the Hows and Whys of Leadership. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, 217–234.

Howard, M., Hopkinson, P., and Miemczyk, J. (2019). The regenerative supply chain: a framework for developing circular economy indicators. Int. J. Prod. Res. 57, 7300–7318. doi: 10.1080/00207543.2018.1524166

Kek, V., and Kandasamy, J. (2018). Sensitization of Sustainable Manufacturing Strategies to Benefit Indian SMEs. Green Production Strategies for Sustainability. Hershey: IGI Global. 92–98. doi: 10.4018/978-1-5225-3537-9.ch005

Kerr, I. R. (2006). Leadership strategies for sustainable SME operation. Bus. Strat. Environ. 15, 30–39. doi: 10.1002/bse.451

Klein, H. K., and Myers, M. D. (1999). A set of principles for conducting and evaluating interpretive field studies in information systems. MIS Q. 23, 67–93. doi: 10.2307/249410

Klomp, K., and Oosterwaal, S. (2021). Thrive: Fundamentals for a New Economy. Amsterdam: Atlas Contact, Uitgeverij.

Kolk, A. (2008). Sustainability, accountability and corporate governance: exploring multinationals' reporting practices. Bus. Strat. Environ. 17, 1–15. doi: 10.1002/bse.511

Lawrence, S. R., Collins, E., Pavlovich, K., and Arunachalam, M. (2006). Sustainability practices of SMEs: the case of NZ. Bus. Strat. Environ. 15, 242–257. doi: 10.1002/bse.533

Lombard, M., Snyder-Duch, J., and Bracken, C. C. (2002). Content analysis in mass communication: assessment and reporting of intercoder reliability. Hum. Commun. Res. 28, 587–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2002.tb00826.x

López-Pérez, M. E., Melero, I., and Javier Sese, F. (2017). Management for sustainable development and its impact on firm value in the SME context: does size matter? Bus. Strat. Environ. 26, 985–999. doi: 10.1002/bse.1961

López-Pérez, M. E., Melero-Polo, I., Vázquez-Carrasco, R., and Cambra-Fierro, J. (2018). Sustainability and business outcomes in the context of SMEs: comparing family firms vs. non-family firms. Sustainability 10, 4080. doi: 10.3390/su10114080

Lozano, R., Carpenter, A., and Huisingh, D. (2015). A review of 'theories of the firm'and their contributions to corporate sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 106, 430–442. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.05.007

Mang, P., and Haggard, B. (2016). Regenerative Development and Design: A Framework for Evolving Sustainability. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. doi: 10.1002/9781119149699

Mang, P., and Reed, B. (2012). Designing from place: A regenerative framework and methodology. Build. Res. Inf. 40, 23–38. doi: 10.1080/09613218.2012.621341

Marcus, J., Kurucz, E. C., and Colbert, B. A. (2010). Conceptions of the business-society-nature interface:Implications for management scholarship. Bus. Soc. 49, 402–438. doi: 10.1177/0007650310368827

Markolf, S. A., Chester, M. V., Eisenberg, D. A., Iwaniec, D. M., Davidson, C. I., Zimmerman, R., et al. (2018). Interdependent infrastructure as linked Social, Ecological, and Technological Systems (SETSs) to address lock-in and enhance resilience. Earth's Future 6, 1638–1659. doi: 10.1029/2018EF000926

Meadows, D. (1999). Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System. The Sustainability Institute. Available online at: http://donellameadows.org/archives/leverage-points-places-to-intervene-in-a-system/ (accessed December 20, 2021).

Morseletto, P. (2020). Restorative and regenerative: Exploring the concepts in the circular economy. J. Indus. Ecol. 24:763–773. doi: 10.1111/jiec.12987

Muisenberg, S., Appelman, J., and Baumeister, D. (2013). Biomimicry: Design and Innovation That Help Reach Eco-Effective Solutions. Green ICT & Energy. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. 151–160. doi: 10.1201/b16361-17

Nan, N., Zmud, R., and Yetgin, E. (2014). A complex adaptive systems perspective of innovation diffusion: an integrated theory and validated virtual laboratory. Comput. Math. Organ. Theory 20, 52–88. doi: 10.1007/s10588-013-9159-9

Pedersen Zari, M., and Hecht, K. (2020). Biomimicry for regenerative built environments: mapping design strategies for producing ecosystem services. Biomimetics 5, 18. doi: 10.3390/biomimetics5020018

Perales-Momparler, S., Andrés-Doménech, I., Andreu, J., and Escuder-Bueno, I. (2015). A regenerative urban stormwater management methodology: the journey of a Mediterranean city. J. Cleaner Prod. 109, 174–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.02.039

Pettigrew, A. M. (1990). Longitudinal field research on change: theory and practice. Organ. Sci. 1, 267–292. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1.3.267

Porter, M. E., and Kramer, M. R. (2011). Creating shared value: Redefining capitalism and the role of the corporation in society. Harv. Bus. Rev. 89, 62–77.

Quintás, M. A., Martínez-Senra, A. I., and Sartal, A. (2018). The role of SMEs' green business models in the transition to a low-carbon economy: differences in their design and degree of adoption stemming from business size. Sustainability 10, 2109. doi: 10.3390/su10062109

Rahimifard, S., Stone, J., Lumsakul, P., and Trollman, H. (2018). Net positive manufacturing: a restoring, self-healing and regenerative approach to future industrial development. Procedia Manufact. 21, 2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.promfg.2018.02.088

Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist. Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing.

Revell, A., Stokes, D., and Chen, H. (2010). Small businesses and the environment: turning over a new leaf? Bus. Strat. Environ. 19, 273–288. doi: 10.1002/bse.628

Roberts, S., and Feeley, M. (2008). “Increasing capacity for stewardship of oceans and coasts: findings of the National Research Council Report,” in Paper presented at the AGU Spring Meeting Abstracts (Washington, DC).

Robinson, J., and Cole, R. J. (2015). Theoretical underpinnings of regenerative sustainability. Build. Res. Inf. 43, 133–143. doi: 10.1080/09613218.2014.979082

Rubin, H. J., and Rubin, I. S. (2011). Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Sanford, C. (2016). Regenerative Business. Available online at: http://trimtab.living-future.org/trim-tab/carol-sanford-regenerative-business/

Seidel, M., Seidel, R., Tedford, D., Cross, R., Wait, L., and Hämmerle, E. (2009). Overcoming barriers to implementing environmentally benign manufacturing practices: Strategic tools for SMEs. Environ. Qual. Manag. 18, 37–55. doi: 10.1002/tqem.20214

Sharp, L. (2015). Transformational Leadership Summit: Delivering the Core Business Integration of Sustainability (CBI-S) Framework. Leeds: University of Leeds.

Silverman, D. (2013). Doing Qualitative Research (Vol. Fourthition.). Thousand Oaks, CA; London: SAGE.

Simpson, M., Taylor, N., and Barker, K. (2004). Environmental responsibility in SMEs: does it deliver competitive advantage? Bus. Strat. Environ. 13, 156–171. doi: 10.1002/bse.398

Smit, B., and Wandel, J. (2006). Adaptation, adaptive capacity and vulnerability. Glob. Environ Change. 16, 282–292. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.03.008

Starik, M., and Kanashiro, P. (2013). Toward a theory of sustainability management: Uncovering and integrating the nearly obvious. Organ. Environ. 26, 7–30. doi: 10.1177/1086026612474958

Strauss, A. L., and Corbin, J. M. (1996). Grounded Theory: Grundlagen Qualitativer sozialforschung. Weinheim: Psychologie-Verlag-Union.

Van Marrewijk, M., and Werre, M. (2003). Multiple levels of corporate sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 44, 107–119. doi: 10.1023/A:1023383229086

Walsham, G. (1995). Interpretive case studies in IS research: nature and method. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 4, 74–81. doi: 10.1057/ejis.1995.9

Walsham, G. (2006). Doing interpretive research. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 15, 320–330. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.ejis.3000589

Westman, L., Luederitz, C., Kundurpi, A., Mercado, A. J., Weber, O., and Burch, S. L. (2018). Conceptualizing businesses as social actors: a framework for understanding sustainability actions in small- and medium-sized enterprises. Bus. Strat. Environ. 28, 388–402. doi: 10.1002/bse.2256

Whiteman, G., Walker, B., and Perego, P. (2013). Planetary boundaries: Ecological foundations for corporate sustainability. J. Manag. Stud. 50, 307–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2012.01073.x

Williams, A., Kennedy, S., Phillip, F., and Whiteman, G. (2017). Systems thinking: A review of sustainability management research. J. Clean. Prod. 148, 866–881. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.02.002

Williams, A., Whiteman, G., and Kennedy, S. (2019). Cross-scale systemic resilience: Implications for organization studies. Bus. Soc. 60, 95–124. doi: 10.1177/0007650319825870

Wright, C., and Nyberg, D. (2017). An inconvenient truth: How organisations translate climate change into business as usual. Acad. Manag. J. 60, 1633–1661. doi: 10.5465/amj.2015.0718

Yin, R. K. (2013). Validity and generalization in future case study evaluations. Evaluation 19, 321–332. doi: 10.1177/1356389013497081

Zhang, X., and Wu, Z. (2015). Are there future ways for regenerative sustainability? J. Clean. Prod. 109, 39–41.

Appendix A (Interview guide)

Background/context

• Could you please give an introduction to your organization and your role in it?

• What does the term “sustainable business practice” mean to you? And what does it mean to your organization?

Regenerative business practice

• How is sustainable business practice different from regenerative business practice? (i.e.: individual perspective)

• Does regenerative business practice have positive impact on the natural environment?

• Does regenerative business practice have a net positive impact on the environment? (net positive is not just reducing negative and compensating to make zero impact, but to go beyond that and make positive impact)

Innovation/Eco-preneurship

• What is the role of innovation/eco-preneurship in regenerative business practice?

Drivers and potential benefits

• What does regenerative business practice mean for your organization?

◦ Is it a priority/ important? (Yes/ No)

◦ What triggered your organization to implement regenerative business practice?

◦ What tools/ processes have been incorporated toward regenerative business practice?

◦ How has it benefited your organization so far?

◦ How do you think it might benefit in the future?

• What are the pathways your organization took to advocate regenerative business practice?

◦ Was it a top down approach or a bottom up approach or both?

◦ Is this regenerative practice embedded in your organizational culture?

• Is an innovation culture embedded in to your organization?

◦ How long has this been this case?

◦ Who is involved in developing this process?

◦ What have you learned through this experience?

Keywords: regenerative business practice, small and medium-sized enterprises, environmental pollution, stewardship theory, case studies

Citation: Caldera S, Hayes S, Dawes L and Desha C (2022) Moving Beyond Business as Usual Toward Regenerative Business Practice in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Front. Sustain. 3:799359. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2022.799359

Received: 21 October 2021; Accepted: 08 February 2022;

Published: 10 March 2022.

Edited by:

Bankole Awuzie, Central University of Technology, South AfricaReviewed by:

Maria Barreiro-Gen, University of Gävle, SwedenCopyright © 2022 Caldera, Hayes, Dawes and Desha. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Savindi Caldera, cy5jYWxkZXJhQGdyaWZmaXRoLmVkdS5hdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.