- 1Cambridge Judge Business School, Faculty of Business and Management, School of Technology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom

- 2Sustainable Earth Institute, University of Plymouth, Plymouth, United Kingdom

- 3Royal Scientific Society, Amman, Jordan

As the extent of damage to environmental systems from our business-as-usual activity becomes ever more alarming, Universities as core social institutions are under pressure to help society lead the transition to a sustainable future. Their response to the issues, that they themselves have helped reveal, has, however, been widely criticised for being wholly inadequate. Universities can be observed to engage with sustainability issues in ad-hoc ways, with the scale of attention and commitment dependant mainly on the level of pressure exerted by stakeholders that works to overcome aspects of inherent inertia. Sustainability initiatives can therefore be regarded mainly as bolt-ons. This mirrors how other sectors, including businesses, have tended to respond. As the environmental and social crisis mounts and the window for adaptive change to ensure long-term wellbeing for all narrows, the pressure for deeper systemic change builds. It is in this context that transformation to a “purpose-driven organisation” has emerged as a systemic approach to change, enabling an organisation to align deeply and rapidly with society's long-term best interest and hence a sustainable future. Nowhere has this concept been taken forward more obviously than in the business sector. As business leadership towards purpose becomes more apparent, so the lack of action in this area by universities appears starker. In this paper we clarify what it means to be a purpose-driven organisation, why and how it represents a deep holistic response to unsustainability, and what core questions emerging from the business world university leaders can ask themselves to begin the practical journey to transform their institutions into purpose-driven universities.

Introduction

“I believe what we do, and by “we” I mean humanity as a whole over the next five years, could well determine the future of humanity. This is a critical time.”1

This blunt warning that humanity is at crisis point, delivered in June 2021 by the former UK Chief Scientist Sir David King, reflects the scientific consensus that climatic and ecological breakdown is happening at a scale and intensity that ultimately threatens the wellbeing of all life on earth. This 1 sits alongside dire warnings of the fragmentation and break down of social fabric globally, from extremely low trust in institutions and science to extreme inequalities “lethal partisanship” of political ideologies. All organisations need to respond to these emergencies that threaten the long-term wellbeing of all people and planet, but the role of universities would seem to be especially crucial. After all, it was research from the global academic community that helped identify and track the decline in the planet's natural support systems (Rockström et al., 2009; Dearing et al., 2014) and continues to expose a pattern of severe social challenges which both affect and are affected by environmental system breakdown (Galbraith, 2007; Turchin et al., 2018). Building on that knowledge base, the higher education sector also offers the critical learning infrastructure to support society transition away from unsustainable practises (Tilbury, 2011). And as socially-embedded institutions vital to the economic development of cities and regions, universities would appear well-positioned to motivate transformations most effectively at scale (Bhowmik et al., 2020).

These three fundamental academic missions—education, research, and societal engagement—form the basis of how universities are expected to respond to the global unsustainability challenge. However, the best way in which universities can apply their transformative potential to help society reconfigure itself rapidly and at scale remains uncertain and contested (e.g., Fazer, 2020; Vogt and Weber, 2020; Chankseliani and McCowan, 2021).

Building on their traditional “first mission” —education—universities are introducing new teaching programmes and specialisation tracks that cover sustainability issues (Nordén and Avery, 2021) and the principles and practises of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) are gaining wider academic traction (e.g., Rieckmann, 2017). However, many universities struggle on how best to incorporate the SDGs in their operations (Leal Filho et al., 2021), how to embrace the whole-institution interdisciplinary thinking and deep system transformation that ESD truly demands (Sterling, 2004; Waas et al., 2012; Singer-Brodowski et al., 2019; Bauer et al., 2021) or rethinking education that reinforces unsustainability (Renouf et al., 2019). Instead, the accusation is that pedagogic makeovers at many universities appear skin deep, presenting incremental changes to study programmes rather than radically refocusing the educational mission on the emergency we face (Maassen et al., 2019; Fazer, 2020).

With regard to universities' research-oriented “second mission,” discovery-led knowledge production underpins scientific understanding of the planetary crisis and, looking forwards, would seem critical for establishing a safe and just living space for humanity (Rockström et al., 2021). Research strategies in many universities are being reconfigured around these new “grand challenges” of sustainable living (e.g., Tyndale et al., 2021), facilitated by interdisciplinary research groups and institutes that confront cross-disciplinary concerns. But beneath the surface, the vast research superstructure often remains wedded to long-enduring, deeply-rooted academic silos in which “frontier science” remains at the heart of knowledge production and outcomes are measured by prestige and volume rather than the likely success or failure of achieving global sustainability goals (Watermeyer, 2019). Despite calls for universities to align their research enterprise with real-world sustainability targets (Schneidewind et al., 2016), there is resistance to the perceived institutional pandering to a “trendy” sustainability rhetoric (Mittelstrass, 2020, p. 27; Crow, 2010) and just a few global institutions have commenced the organisational reform needed to span the sprawling complexity of planetary problems (Schneidewind and Singer-Brodowski, 2014; Crow and Dabars, 2015).

But it is in universities' more recent “third mission” —the direct transfer of knowledge and technology to society (Krücken, 2003, 2020; Laredo, 2007; Zomer and Benneworth, 2011; Trencher et al., 2014; Compagnucci and Spigarelli, 2020) that their contribution to society has been most effectively expanded (Gibbons et al., 1994; Nowotny et al., 2002; Benneworth and Jongbloed, 2010). Ultimately, that third mission sets the boundaries of universities' social licence to operate—the licence given by society to an institution to utilise commonly shared resources and transform them, ostensibly because this transformation of resources is deemed by society to improve its overall wellbeing2. The idea of “the university” —and its long-standing twin academic missions of “education” and “research” —was established long before the relative democratisation of social decision-making, during times when broader societal legitimacy was not required. In modern democratic societies, however, institutions such as universities increasingly require legitimisation by society if they are to retain a licence to operate, and the third mission emerged from this context (Weymans, 2010).

The third mission is only a few decades old, and the nature of this “invisible revolution” (Etzkowitz, 1998) remains still only weakly institutionalised (Zomer and Benneworth, 2011). For many universities, its implementation has provoked “…fundamental discussions about what they are expected to accomplish for society, how they are to be made more accountable to society, and what kind of relationship they should have with core organizations and actors in society” (Maassen et al., 2019, p. 8). If the third mission is viewed as a default mechanism to better align universities with the interests of society, then its enterprising and entrepreneurial activities arguably provide the practical means by which they may transform to better serve the long-term wellbeing of society, hence the third mission is epitomised by the rise of entrepreneurial academies such as MIT and Stanford (Etzkowitz et al., 2000; Etzkowitz, 2004). However, this premise arguably rests on questionable assumptions deep within the current economic paradigm about what wellbeing is and how it is best delivered to society.

Because the third mission is intricately connected with economic organising, fundamental problems arise when seeking to advance the third mission because our current economic way of organising tends to be regarded as deeply complicit in the current socio-ecological crisis (Van Weenen, 2000). This western-inspired, but globally implemented “business-as-usual” neo-classical economic system emerged during, and co-evolved with, the dramatic post-war global surge in economic growth and human activity across the world, dubbed the “Great Acceleration” (Steffen et al., 2015; McNeill, 2016). It is this “human age” —or Anthropocene—that is associated with the simultaneous acceleration in biodiversity loss, climate change, pollution and destruction of natural capital (Steffen et al., 2004, 2015; Rockström et al., 2009; Griggs et al., 2013; Dearing et al., 2014). A dominant narrative, therefore, is that, in the late 20th century, esteemed independent establishments of knowledge acquisition, curation and dissemination gradually, through “mission creep,” became harnessed as “organs of the state,” increasingly utilised for solving problems of the economy (Clark, 1998; Etzkowitz, 1998; Bleiklie and Kogan, 2007; Laredo, 2007; Perkin, 2007; Zomer and Benneworth, 2011; Davey, 2017). With the economy charged with being at the very heart of our unsustainability, the third mission can be viewed tied to the root of the unsustainability issue, as taking universities off-track with delivering in the interests of society rather than its saviour.

For some, the route to better aligning universities with society's long-term interest is for universities to be unshackled from delivering for the economy via its third mission, and therefore again be freed to better futureproof the academic endeavour (Boulton and Lucas, 2011). For others, the remedy is to re-position even more deliberately towards the “entrepreneurial university” (Clark, 1998) but in more socially-oriented terms, as “sustainable,” “stakeholder,” “civic,” “transformative” or “compassionate” institutions (Bleiklie and Kogan, 2007; Sterling, 2013; Waddington, 2021). While some see the pursuit of sustainable development goals as being achievable through fragmentation into socially-, environmentally- and economically-oriented universities (Beynaghi et al., 2016), others see the need to distinguish a “4th mission” (Trencher et al., 2014; Riviezzo et al., 2020). (Trencher et al. 2014, p. 152) calls this new mission “co-creation for sustainability”, defined whereby a university “collaborates with diverse social actors to create societal transformations with the goal of materialising sustainable development in a specific location, region or societal sub-sector.”

Some, however, go further, beyond a triple helix of missions and towards an overarching reconceptualising of the core reason of the university to exist that would guide how all other missions are achieved. Lueddeke (2020) argues for a thorough re-conceptualisation of the higher educational fundamental goals and scope to focus on developing an interconnected ecological knowledge system with a concern for the whole Earth. Utilising the concept this paper will focus on, Haski-Leventhal (2021) calls for universities to consciously become “purpose-driven” by utilising their “resources, knowledge, talent, and people to continuously and intentionally contribute to the communities and the environment in which it operates, through research, education, programmes and services” (Haski-Leventhal, 2021, p. 7). This latter proposition draws from “organisational purpose,” a concept with deep roots in management thinking (Barnard, 1938; Drucker, 1974; Freeman and Ginena, 2015), and recently popularised in the practical business context with bespoke reports (e.g., Deloitte “2030 Purpose”), rankings (e.g., Radley Yeldar “Fit for Purpose”), guidance from most of the large consultancies (KPMG, Deloitte, Accenture etc.) and a range of popular literature (e.g., Sinek, 2011; Rozenthuler, 2020). However, confusion has reigned regarding what, precisely, “organisational purpose” means and how to achieve it. As clarity and consensus increases, and examples of purpose-driven transformation, particularly in the business sector, are ever more accessible (Deloitte, 2020; British Academy, 2021), we make a theoretical contribution by arguing that the concept of purpose has the potential to both help elucidate the current barriers and future opportunities for universities to become aligned with delivering long-term wellbeing for all (sustainability).

Core to our theoretical argument is that it is not universities' role in the economy per se that is the issue but the assumptions about how the economy should be organised. The economy, after all, is the central organising system for transforming resources into wellbeing outcomes for all of society in the long term. Hence the very definition of the ultimate ends of the economy are fundamentally aligned with the definition of the goal of sustainability as conceptualised by the Brundtland report (Brundtland, 1987)—satisfaction of needs (wellbeing) for everyone, into the future—which can be considered an expression of society's “meta-purpose.” What is of issue, however, is that in recent decades society has effectively outsourced these long-term wellbeing outcomes to a very specific and almost unquestioned way of organising—a “wellbeing machine”, market-based, resting on the optimising of self-interest of all parties and focused on measures of financial success as a proxy for wellbeing. As a system in theory optimised ultimately for society's wellbeing, this business-as-usual system has provided a moralising agenda for drawing all other organisations into its service as a way of securing social legitimacy. As these assumptions change rapidly, and impelled by purpose as a central concept operationalising a new economic paradigm, the basic reason for a university to exist is coming into the spotlight, illuminating its role in delivering long-term wellbeing for all.

Purpose involves rejecting, in effect, of many of the fundamental economic assumptions that have become engrained in organisational worldviews, principles and behaviours, and which uphold pervasive power structures and those that benefit from them. Hence, this makes it both unintuitive and hard for organisations, including universities, to initiate and maintain the radical change agenda that purpose requires. These challenges aside, and given the requirement for rapid change, purpose appears almost singular in its potential to provide the deepest level of alignment between organisations and society's long-term wellbeing and therefore need to be seriously considered by both university governing bodies and executive managers, as well as the broader social and legislative environment that enables them.

Hence, we argue that the solution to unleashing the ability of universities to address unsustainability lies not in avoiding their role in the economy but by them becoming more active participants in reshaping the economy's assumptions and ways of operating towards delivering its intended promise—long-term wellbeing for all. This, we set out, involves re-envisioning the university's reason to exist, and all resulting behaviour, as a strategic contribution to society's meta-purpose of long-term wellbeing for all people and planet and consciously achieving this in a way that protects and enhances the environmental and social systems that underpin it—in other words, becoming purpose-driven.

We start by setting out in more detail the prevailing notion that business is the engine for wellbeing generation and how this business-as-usual “wellbeing machine” has influenced the worldviews, principles and behaviours of all organisations, including universities. From there we use a modified Daly's Triangle of the economy to outline business-as-usual's inherent misalignment with sustainability and situate the concept of purpose as a paradigmatic break with business-as-usual amongst two other organisational paradigms, which form adaptive tweaks that are constrained in their ability to address sustainability. We then specifically compare universities to these three organisational logics, illuminating current university logic as firmly aligned to business-as-usual. A Supplementary Table 1 is available that makes this case through archetypal university behaviours. We end by suggesting core questions emerging from the business world that university leaders can ask themselves to begin the journey to being purpose-driven organisation.

The Wellbeing Machine and “Business-As-Usual” Logic

Wellbeing is an umbrella term for what makes an optimal life for humans, and therefore the overarching goal of “development.” Here, it is defined based on the definition used by the British Standard in Social Value as: “a state of being where subjective and objective psychological or physical human needs are met in varying degrees, with increased wellbeing corresponding with better states of physical and psychological health” (British Standards Institute, 2020). Although wellbeing can be viewed as either hedonic or eudaimonic (Ryan and Deci, 2001), the more common eudaimonic approach is emphasised here, where wellbeing can be likened to the notion of flourishing or the “good life,” including being able to participate purposefully (Brand-Correa and Steinberger, 2017). This is not always correlated with hedonic wellbeing, which is individualistic and pleasure/happiness oriented.

In economics, wellbeing has been variously interpreted and abstracted through concepts of welfare or the mechanism of utility—representing various levels of distancing and proxy assumptions about the core underlying concept of wellbeing.

The phrase “long-term wellbeing for all” is a re-expression of sustainability—the goal of sustainable development as expressed by the Brundtland's definition and endorsed by the majority of the world's nations. It may, as the Brundtland report itself implied, be the closest we may get to an expression of humanity's “meta purpose” (Hurth and Whittlesea, 2017; Hurth and Vrettos, 2021). Optimally transforming and allocating resources for the wellbeing of society as a whole in the longer-term is also, importantly, a fairly stable interpretation of the object of an economy. Hence, stripped down to its fundamentals, the economy should be a core vehicle of sustainability, and the key delivery mechanism is business.

“Businesses as human institutions are established in order to better society through the production of goods and services and the advancement of knowledge” (Freeman and Ginena, 2015, p. 12).

Business enterprises…are organs of society. They do not exist for their own sake, but to fulfil a specific social purpose and to satisfy a specific need of a society, a community or individuals. (Drucker 1974, p. 39).

The “Business-As-Usual” (BAU) view is that wellbeing is optimised for society as a whole through each individual selfishly focusing subjectively on discernible personal wellbeing and selecting the best offerings from the choices available in the formal market to match this. As long as companies act competitively, and in their self-interest, and are free to offer their wares in the market place to fulfil that customer demand—and as long as people are able to freely choose from what is on offer, then, with perfect information to guide their (generally) rational decision-making, only income, or interferences from government that reduce this free-flowing supply and demand, constrains their ability to maximise their wellbeing (Sen, 1977; McFadden, 2006). Hence, there is a self-reinforcing idea that a selfish focus on financial income generation by all parts of the economic and broader societal system is the morally valid focal pursuit for delivering optimised societal wellbeing for everyone. At an organisational level, these assumptions translate to: (1) that people act (generally) self-interestedly, (2) that institutions need to focus primarily on their financial health, and (3) that market demand and market share (which feed financial indicators) are the core measure of success.

As well as society's wellbeing being fulfilled through market choices in an unconstrained market, the assumption described as “a rising tide lifts all boats” or “trickle down” justifies the in-built tendency for wealth to concentrate under these conditions (Stiglitz, 2019). Trickle-down economics accepts that those who create and run businesses may become much richer than others, but this is a necessary condition to enable money to be raised for business activities which after all create jobs, enabling poorer people to invest and spend in the market and thereby enhance their wellbeing.

Under BAU logic, there are two key ways an organisation can contribute to society's wellbeing as part of the market system, both of which have been emphasised by universities in recent years as part of their wider service to society. These are either by employing more people or by selling more of the products and services that people judge as useful to maximise their utility. As well as being a macro-level indication of financial income success of a nation, at a meso-organisational level, growth in sales is an indication that preferences are being met, because it shows that more people are choosing that company's offerings above competitors. By extension, growth is an indication that the organisation is better at providing for wellbeing in the market.

The assumptions of business-as-usual thinking that profoundly underpin actions across society and its institutions now, have deep roots—roots that go back to Smithian (Smith, 1776) views of the market. The “free hand of the market” and related concepts, were dominant in the mid 19th century in the US and beyond, saw a fall from favour as government intervention began to address issues of concern to society at the time immediately following the First World War (Bowen, 1953), only to be re-popularised (and many argue misrepresented) and made more morally resonant in the 1970s by Friedman and others at the “Chicago School of free-market economists” (Stout, 2012). The conditions for the widespread acceptance of these assumptions was in the post-war period when the dangers of subjective, value-based whims of government (e.g., Hitler); an increasingly powerful managerial class (whose interests were seen to be aligned with government rather than investors) helped, set the scene for the dominance of free-market economic thinking that we live with today. This thinking also manifested as a concern by investors that their money should not be used either to line the pockets of managers or to divert this money to pursue the non-democratic individual values of managers (Jensen and Meckling, 1976). Rather, given the risks taken by investors, financial income should be maximised through companies, and this income should be for the primary benefit of shareholders, who should also have ultimate control rights (Friedman, 1970; Stout, 2012). Laissez-faire, profit-maximisation version of capitalism, based on neo-classical economic thinking and extended politically as neo-liberalism [which we will refer to as business-as-usual (BAU)], hence became established as the largely unquestioned way to allocate scarce resources for society. Further, socialism and social responsibility were contrarily positioned as non-market, values-based fulfilment of wellbeing outcomes by a political or managerial elite: “the doctrine of “social responsibility” involves the acceptance of the socialist view that political mechanisms, not market mechanisms, are the appropriate way to determine the allocation of scarce resources to alternative uses” (Friedman, 1970, p. 3). In the context of the cold-war this deliberate symbolic association was even more powerful.

From these US-leaning, neo-classical roots, the BAU view of wellbeing production has been globally embedded and promulgated as a centrepiece of Western ideological dominance, to the extent that, across cultures worldwide, its underpinning philosophical and technical assumptions are dominant (Stiglitz and Pike, 2004; Gray, 2015) and affect every level of global society in some way (e.g., Freeman and Liedtka, 1991; Kilbourne et al., 1997; Firat and Dholakia, 2006). As a result, a very specific “theory of change” about how an economy can best deliver long-term wellbeing for all that has become encoded in the paradigmatic worldviews of a least two generations. This worldview situates wellbeing as the default outcome of “an automatic self-regulating system motivated by the self-interest of individuals and regulated by competition” (Bowen, 1953, p. 14) —a “wellbeing machine” that just needs to be fed and its rules adhered to.

If society views businesses as the “engine room” of the wellbeing machine (because the economy is assumed to be the most effective way, overall, to optimise social wellbeing), then it makes moral sense for universities and all other non-business institutions to support this system. Thus, universities may accept BAU assumptions, genuinely believing this was the best contribution to society they could make. Even if not, it still makes sense for a university to be seen to feed this wellbeing machine economy, as a way to ensure their continued social legitimacy. Viewed in this light, universities have evolved to become “business-like,” and to serve the business through their third mission, expressly because it is business that society has positioned as the best means to deliver society's wellbeing. Rather than mission creep or immoral and illogical “selling-out,” the “third mission,” therefore, simply reflects universities' alignment to the prevailing moral landscape that positions the market as the optimal way to deliver and sustain public good. In that context, it is not only the logical, but also the morally correct response of universities to serve this system.

Over the course of the 20th century, BAU could be judged as having delivered significant improvements in human wellbeing (Pinker, 2018; Rosling, 2019), but the level abstraction and false reliance on proxy measures of wellbeing has driven a lack of accountability to the ultimate ends of wellbeing that has taken us to a point of potentially irreversible unsustainability.

Globally, financial income growth has not been decoupled from resource consumption and environmental pressures and is unlikely to become so, at least within the urgent timescales for action (Hickel and Kallis, 2020; Wiedmann et al., 2020). The global material footprint, gross domestic product (GDP) and greenhouse gases emissions have increased rapidly over time, and strongly correlate (Coscieme et al., 2019). While population growth was the leading cause of increasing consumption from 1970 to 2000, the emergence of a global affluent middle class has been the stronger driver since the turn of the century (Panel, 2019; Wiedmann et al., 2020). This tight coupling between the unfolding socio-ecological crisis that fundamentally threatens long-term equitable wellbeing, and growth in financial measures that are supposed to indicate wellbeing success (e.g., GDP), sets the scene for the dramatically unfolding paradigm shift in assumptions about how resources are best transformed into long-term wellbeing for all (Fioramonti et al., 2022). By extension this puts a spotlight on all organisations, including universities, that have become complicit in upholding the current BAU assumptions and are intricately organised in ways that align with them. This, in turn, has fundamental implications about why and how universities will need to change over the next few short years, the reflexive challenges they will need to confront, and the scope of the changes they will need to make if they are to continue to be accepted and supported as legitimate public institutions.

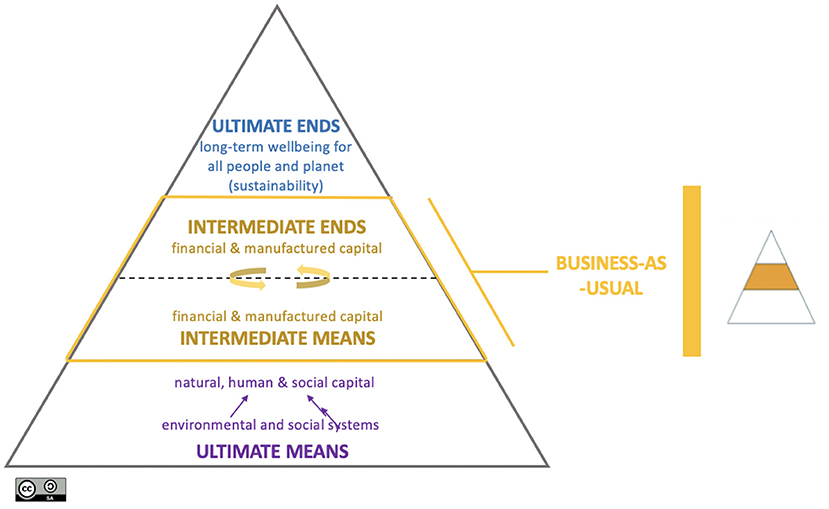

Moving Away from Business-As-Usual—Adapting Daly's Triangle

One of the clearest ways of visualising why the current BAU paradigm is inherently unsustainable, and which provides a simultaneous conceptual frame to reimagine it, comes from eminent ecological economist Herman Daly. His “triangle” (Daly, 1973) as adapted by Donella Meadows, depicts the myopic view of institutions that results from BAU, where both thinking and action focuses on intermediate means for intermediate ends. By contrast, a sustainable economy requires both a focus on delivering the ultimate ends (wellbeing) and achieving this within the ultimate means (planetary health). Donella Meadows and her colleagues appraised this as the most effective overarching framework that could clearly encapsulate both the problem of unsustainability and the way to achieve it (Meadows, 1998). Although Daly and Meadows viewed wellbeing, delivered through a suite of universal human needs as the ultimate ends of the economy. The adapted triangle (Figure 1) aligns this more fully to the expression of sustainability and its three conditions—wellbeing, over time and for everyone. Furthermore, the ultimate means were originally limited to the natural capital provided by planetary resources, however the triangle in Figure 1 is adapted to incorporate and situate the full spectrum of ultimate and intermediate capitals which an organisation utilises as inputs into its operating model (IIRC, 2020).

The modified triangle highlights how current BAU thinking relegates the ultimate ends of society as outside of the scope of economic consideration, and by extension outside of the strategic imperative of organisations. As the gravitational allure of BAU logic has drawn most parts of the wider social system into its narrow orbit, the sheer power and reach of the formal market and its actors has evidently diminished the ability of the system to be held to account, both in terms of whether it is actually achieving the wellbeing ends it claims to and whether it is doing this in a way that ensures healthy environmental and economic systems for future generations.

As evidence grows that humanity faces an ultimate means (planetary and societal system) crisis and an ultimate ends (wellbeing) crisis—and bruised by huge economic crises—faith in the BAU wellbeing machine is faltering fast. Arguments that the current form of capitalism must be urgently reinvented are now building with force within most mainstream sectors, including civil society, academia and perhaps most prominently, business itself. World Economic Forum executives freely pass judgement that “Neoliberal economics has reached a breaking point” [WEF (World Economic Forum), 2017, p. 1] and the global trade governance institutions themselves, who have been key advocates of BAU but are now recognised by some as “a tool to identify solutions to problems created by neo-liberal globalisation” (Biermann and Pattberg, 2008, p. 279 in Jang et al., 2016).

The Practical Backlash to BAU: The Rise of the Wellbeing Economy

The urgent new imperative is to re-align the economy directly to its ultimate ends of wellbeing in a way that can be delivered in the long-term and for everyone. At a global governance level, this imperative began as a way of addressing the perceived dangers of focusing on GDP as the ultimate financialised expression of the BAU economic imperative, by broadening or replacing it with direct measures of the ultimate ends of the economy i.e., wellbeing (Stiglitz and Pike, 2004; Stiglitz, 2019). Countries such as Bhutan were early in replacing GDP with a measure of “Gross National Happiness” but since then a range of overarching wellbeing methodologies have been developed. In 2007, the European Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress (CMPEPS) “gave a huge impulse to a discussion that had been ongoing for several years on the limits of GDP as a welfare metric” (OECD, 2020). This, in turn, led to global measurement frameworks such as the OECD's “Better Life Index.”

The pursuit of human and ecological wellbeing rather than material growth has become known as the “Wellbeing Economy” (Fioramonti et al., 2022), or in OECD's words the “Economy of Wellbeing” (Llena-Nozal et al., 2019)—the first level of ensuring operationalisation of long-term wellbeing for all (sustainability) through the economy. Measuring the ultimate outcomes of the economy—and whether they align with the wellbeing outcomes they claim to, represents a significant step away from faith in BAU thinking. However, realigning value creation activities across society and its institutions to effectively create long-term wellbeing for all is the more important and difficult task. To that end, organisations such as the Wellbeing Economy Alliance are bringing together global actors to share insights and advance practise (Waddock, 2021). As part of this, WeGO represents a small but growing group of governments, including Scotland, New Zealand, Iceland, Wales and Finland, who are declaring that their countries are to be governed directly for wellbeing outcomes (Wellbeing Alliance, 2021)3. According to Fioramonti et al. (2022), adoption of the Wellbeing Framework could be extended globally, holding the promise of a powerful and adaptable cultural and socio-economic narrative that offers radical change in a timely fashion.

The Wellbeing Economy utilises market mechanisms and maintains the overall private investment structures in place and hence can be considered a reinterpretation of capitalism rather than a rejection of it4. However, it marks a fundamental paradigm shift in the assumptions about the economy. It directly counters neo-classical assumptions about the efficacy of the “wellbeing machine” and how institutions should engage with the market to deliver wellbeing for society as a whole. By extension, the Wellbeing Economy contests the prevailing notion that an organisation is morally sanctioned to focus on capturing value for itself (be that profit for members, or financial reserves for growth). Instead, the focus and accountability of the economy are resituated very deliberately to society's ultimate wellbeing outcomes (“ends”) and the contribution to health of social and environmental systems as the ultimate means by which this wellbeing can be achieved.

Purpose and Purpose-Driven Organisational Logic

The Wellbeing Economy sets the macro-level economic response to the crisis of faith in BAU but at the meso business level, solutions have come in the form of the concept of “purpose-driven organisations.” Essentially, the concept of “purpose” can be considered as the way to practically operationalise the Wellbeing Economy, by anchoring a company's primary reason to exist to wellbeing outcomes and by relegating financial considerations to an intermediate means to that meaningful end (Hurth and Vrettos, 2021).

Various conceptualisations and definitions of purpose have emerged (e.g., Ellsworth, 2002; Hollensbe et al., 2014; Henderson and Van den Steen, 2015; Mayer, 2018) but two key aspects tend to unite them. The first is that purpose lies at the deepest level of an organisation's identity—its reason to exist in the first place—and in the fundamental outcomes it has been set up to produce. The second is that purpose is purposeful, in that it is about serving the fundamental wellbeing of another. At its essence, therefore, purpose is an organisation's “meaningful and enduring reason to exist” (Ebert et al., 2018). In the sense that it is meaningful and in the service of others, purpose eliminates the idea that a self-interest motivation can be a valid purpose, or that serving someone can be based on a superficial reading of their short-term desires. Hence, purpose, fully implemented, acts to strategically orient daily decision making across an organisation towards a shared, central and non-self-interested value generation goal. The British Academy investigation into the “Future of the Corporation” contend that “the purpose of business is to solve the problems of people and planet profitably, and not profit from causing problems” (British Academy, 2019, p. 8). If it is to be a socially legitimate and optimal then these “problems” have to be aligned with positive impacts that progress towards humanity's most consistently expressed meta-purpose of long-term wellbeing for all (Hurth and Vrettos, 2021). Further, to ensure this contribution, the purpose needs to achieved in a way that protects and enhances the ultimate means i.e., not delivered in a way that has negative impacts on them. Additionally, purpose makes clear that profits are an important means to an end because they provide the financial resources necessary to achieve the purpose and satisfy stakeholders who support this endeavour. For that reason, organisations of all types need to produce their outcomes profitably.

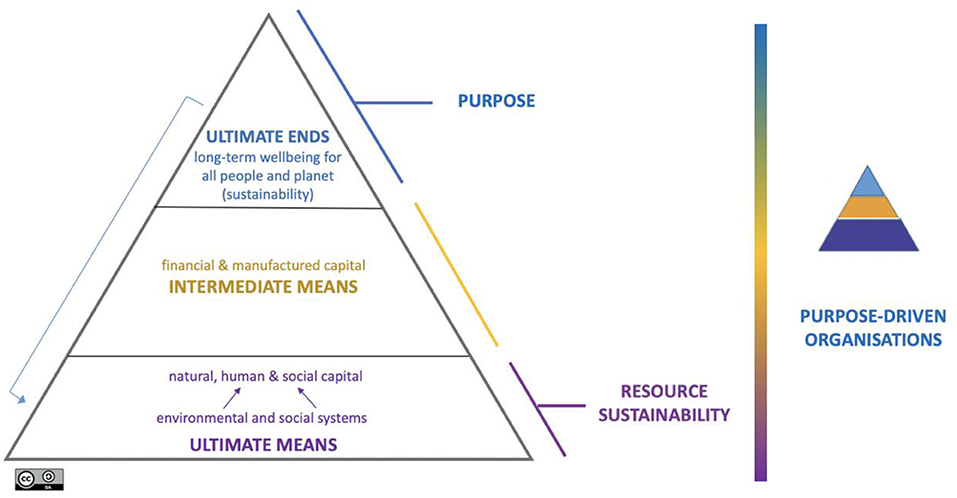

Thus, in effect, purpose and the Wellbeing Economy work together to address problems of BAU by expanding the economic logic and strategic sights of organisations from near-term financial gain for the firm and its members, to deliberate impact on the ultimate ends of the economy and deliberate protection of the economic means. In this way, purpose, at least theoretically, brings into line the goals of society, organisations, the economy and sustainability. At their best, purpose-driven organisations are an expression and operationalising of a sustainable economy as they encompass the totality of Daly's triangle (Figure 2). Thus, purpose tackles head on the enduring issue of how to embed sustainability in organisations, and universities in particular (Lozano et al., 2015), by effectively situating sustainability as the “golden thread” that runs “throughout the entire university system” (Lozano et al., 2013).

Through declaring and delivering against a purpose as conceived above, organisational notions of “value,” strategies to achieve it, and ideas of accountability become, through purpose, directly related achieving sustainability.

Purposes can be set at a high level such as “make sustainable living commonplace (Unilever)” or at a more strategic level “Helping home-based patients become healthy and autonomous” (Buurtzorg). The travails of traditionally “for-profit maximisation” companies attempting to becoming purpose-driven are refining the notion of purpose and reveal that this assumption cannot be taken for granted even for organisations that are socially embedded and engaged. For example, whereas charities, social enterprises and public sector institutions may be assumed to already be purpose-driven, in reality the clarity and alignment needed to deliver a useful, sustainable contribution to society may be absent.

The difficulties of shifting from one set of, usually implicit, assumptions about the ultimate value an organisation exists to create, towards a very different kind of value, within a short period of time, cannot be underestimated. For many the allure of the rewards and the difficulty of the path have led to widespread evidence “purpose-washing,” where a company is creating the impression that it is purpose-driven for financial gain. In fact, purpose involves the deepest level changes to identity, stakeholder constellation, and organisational culture [Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership (CISL), 2020]. Organisational culture constitutes “the pattern of beliefs, values and learned ways of coping with experience that have developed during the course of an organization's history, and which tend to be manifested in its material arrangements and in the behaviours of its members.” (Brown, 1998). Many of these cultural arrangements (hardware) and behaviours (software) are likely to require “unfreezing” in a transformative process that is radical and episodic but also which needs continual maintenance given that the external system remains influenced by BAU thinking and path dependency. Hence, purpose represents a huge adjustment for any organisation that has been part of the wider BAU culture, particularly incumbent businesses, and especially those that are shareholder owned.

As with the Wellbeing Economy, only a few short years ago, the idea of purpose-driven business would have seemed fantastical and even heretical, but is now talked about openly and positively by in the likes of The Economist (2019), The Financial Times (2021), and WEF (World Economic Forum) (2017); Schwab (2019). Perhaps because of the corporate sector's central role in the market economy (and its unsustainability), the first signs of foundational change are showing. One especially important signal of intent came from the bastion of BAU thinking, the US Business Roundtable, when around 180 CEOs of the US's largest companies declared that the purpose of business was no longer to maximise profits for shareholders but promote an economy that serves all Americans (US Business Roundtable, 2019). This statement added credence to the bold view of Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock, the world's largest and most powerful financial asset manager, who asserted a year earlier to the CEOs of all firms they invest in that “Society is demanding that companies, both public and private, serve a social purpose” (Fink, 2018, p. 1).

Firms that are making the shift to purpose, not unexpectedly, are also finding that that purpose is addressing a wide range of issues they were facing, from hiring and retaining the best talent and improving customer loyalty to increasing agility and productivity (Blueprint for Better Business, 2015). It is more than a happy coincidence that purpose taps into, and unleashes, the fundamental drive of humans to serve the wellbeing of others (i.e. be purpose-driven)—something which has until now been relatively ignored in organisational management in favour of a BAU financial self-interest approach (Ebert et al., 2018).

Reflecting these sentiments in practise, albeit with varying levels of authenticity and progress, it is now commonplace to see companies revealing their “purpose” or rediscovering one they had prior to BAU's cultural dominance and undertaking the hard journey to transform the cultural hardware and software of their organisations. This means the deliberate auditing and appropriate transformation of functions, processes, structures and behaviours so that they are working to strategically optimise delivery of the purpose and not some other kind of value. It also serves to shift the innovation potential of institutions to beyond market solutions, somewhat addressing the issue of over-marketisation.

Whilst purpose-driven start-ups are commonplace and relatively straightforward, companies that have gone on a journey of transformation include companies as large, complex and established as Unilever or Natura (which was the first publicly floated company to be constituted as a Benefit Corp—a particular form of constituted company where a meaningful purpose must be encoded in its statutes). It also includes companies from sectors as problematic as fossil fuel extraction, such as DSM, the Dutch state coal mining company which shifted to sustainable nutrition, and Ørsted, the Danish multinational power company that switched from oil and gas production to being the world's largest developer of offshore wind energy (Madsen and Ulhøi, 2021). Such shifts are now increasingly aided by large business consultancies that help organisations move from BAU to Purpose and abetted by purpose-driven rankings. Despite such rankings, because purpose is fundamentally about core intent, which is then translated into a journey of implementation, discerning the genuine purpose-driven firm from one that falls short of this transformative mark requires a framework of analysis. Two alternative firm logics have emerged from the sustainability crises which may make an organisation appear purpose-driven, when in fact they are not (Hurth, 2021). As will be outlined later, these archetypes are just as relevant for universities as for businesses.

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Logic

If organisations are pretending their reason to exist is to serve society, when actually this is just an image management exercise that is being cynically used to capture the support of stakeholders or to hold off negative stakeholder pressure (including regulatory pressure by government), then they are “purpose-washing.” These organisations are operating firmly as classic BAU organisations, bounded within the middle of Daly's triangle with a focus on near-term self-interest (see Figure 3).

Developing a purpose to appear in line with sustainability is part of suite of ad hoc stakeholder pressure-reducing measures that are often referred to in the business world as ‘Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) measures. In contrast to the more recent deeper social impact focused intent of the academic concept of “broad CSR” (Schwartz and Saiia, 2012)—we use the term here in the way that CSR has generally been interpreted by businesses. As the ex-brand manager of Dove, a Unilever brand noted: “If you think about corporate social responsibility, it kind of feels very bolted on to an organisation, and it's often one of the first things that get hit by budget cuts. It's often one of the things that most people dismiss as not core to their business strategy. But if you have a purpose, then that is your core” (Ebert et al., 2018, p. 12).

Enlightened Shareholder/Self Value/Stakeholder View (ESV) Logic

For another category of BAU companies, profit maximisation still remains the overarching goal but there has been a genuine shift in their thinking as they confront the unsustainability data and the stakeholder pressure in a far more considered and mature way.

This category is known as “enlightened shareholder value” (Ho, 2010), but could be more broadly termed “enlightened self-value” because many companies' imperative is survival at all costs, and because shareholders are, at least in theory, also part of the internal system. The stakeholder is “enlightened” through recognition of the deep crises of the ultimate means. For ESV organisations, the key shift is a move from short-term securing of maximised financial resources for the firm and/or its members, to longer term maximisation. ESV is often prompted by the realisation that an organisation will not be able to deliver maximised profits, or continue to survive for much longer, unless they confront the issues of unsustainability and respond adequately to stakeholders' demands for value to be better distributed to them. The result is a deeper mindset change to strategizing and operate against longer-term, and hence more systemic, context.

For ESV organisations, therefore, decision-making begins to extend to all resources that value generation rests on, including, crucially, the sustainability of the resource base. As a result, understanding to what extent a company's survival rests on the health of the climate, ecosystems, forests, social equality, mentally healthy workforce etc., and then acting to protect this, becomes central. An ESV approach therefore encapsulates both the middle and the bottom of Daly's triangle (Figure 4) by bringing the resources that underpin value creation into its realm of thinking and action (“resource sustainability”). This new thinking leads to a company displaying a range of positive stakeholder- and sustainability-aligned actions. However, ultimately, their actions are tethered to whether or not they can be justified to ensure the firm's long-term survival and/or optimal financial success. If not, then actions are unlikely to get support. For this reason, these organisations are limited in their sustainability innovations and cannot be considered purpose-driven because their ultimate ends are not anchored to optimising wellbeing.

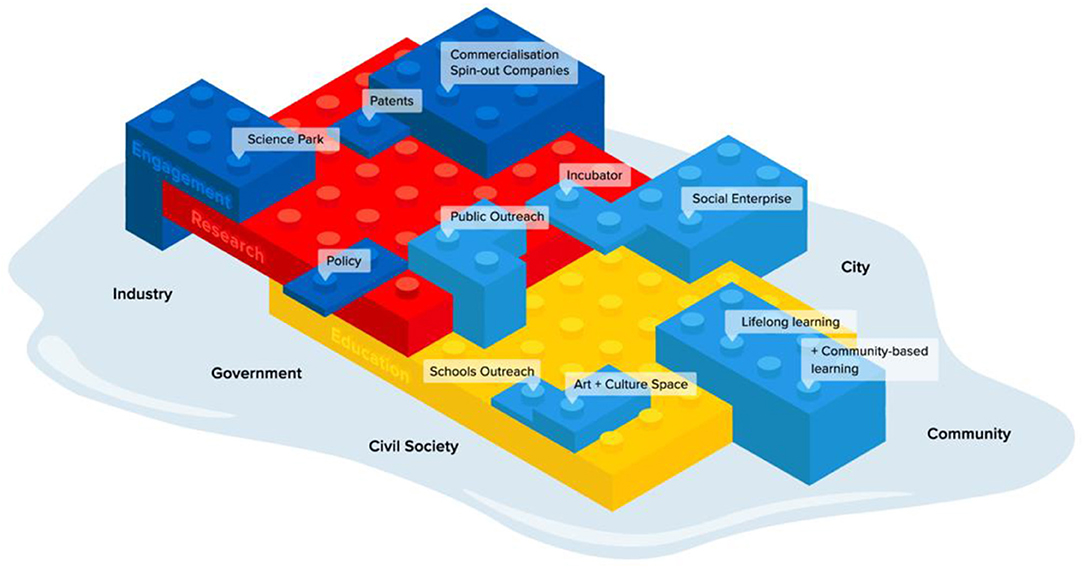

Figure 4. The Amalgam of university third mission activities. In many universities, recent “third mission” activities are often bolted on to their long-standing twin missions of education (yellow) and research (red). Some of these third mission activities are focused on business and innovation ventures (dark blue) whilst others are more socially and community directed engagements (light blue), resulting in a complicated amalgam of extra-mural functions.

Universities: The Path to Purpose

Many in the academic sector would argue that universities cannot or should not be compared to businesses. But, in part, this reflects the tendency of the BAU approach to compartmentalise the economy, promoting a view that profit-(maximising) organisations are somehow fundamentally different to non-profit (maximising) ones. Profits, however, are a necessary operating condition for all organisations—the differentiating factor is what they are used for. An example of how the “profit problem” can be reframed is provided by the University of Aberdeen's vision strategy Aberdeen 2040, which expresses a commitment to “generate resources for investment in education and research year on year, so that we can continue to develop the people, ideas and actions that help us to fulfil our purpose5.” Indeed, the above analysis of businesses can be applied to universities expressly because all organisations have become business-like in the way they are led and run and in the way they operate from the similar economic paradigmatic assumptions. Moreover, purpose is a concept that is institutionally agnostic—it sets an orienting frame of long-term wellbeing for all that profoundly unites all organisations regardless of their constitutions. Research into purpose-driven firms shows that this unites not just the destination of organisations of different types, but also the path, motivating collaborations and innovations that transcend traditional boundaries (Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership (CISL), 2020).

The BAU University

Universities may see themselves as socially-responsive, and responsible, organisations with an academic mission to improve the common good, but applying the above framework of analysis it is hard to see most universities as purpose-driven, or even on a purpose-driven journey. Instead, the weight of current evidence points to universities being locked into a CSR approach to unsustainability data, firmly entrenched within a BAU paradigm of the world.

The third mission has been the core way in which universities have sought to directly address the concerns of society. The third mission, in itself, could be seen as a CSR-type activity, being bolted on to what is considered the core work of education and research. It is therefore not surprising that, despite offering the promise of new moral narratives to bridge with society (Lee et al., 2020), in many universities “the third mission” has accrued as an ad hoc amalgam of outward-facing academic ventures (Philpott et al., 2011; Knudsen et al., 2021) (Figure 4).

Some of these ventures tend to be coordinated from the top, notably strategic knowledge-transfer partnerships that strengthen links between research and industry (commercialisation, licencing of patents, spin-out companies, science and technology parks) to support regional innovation, job creation and economic competitiveness (Mathisen and Rasmussen, 2019). Others are decentralised and grafted on as a bottom-up portfolio of diverse civic initiatives, social enterprise, lifelong and community-based learning, and public outreach programmes (Bell et al., 2021). The result of this hybridisation can be a bewildering multiplicity of extra-mural activities that academics are expected to engage in (Bleiklie et al., 2011) but which appear to react to varying external demands rather than reflecting a coherent internal strategic intent.

By extension, much of the observed university responses to global sustainability imperatives has been criticised as “strategic posture” (Oliver, 1991), in which universities' promote sustainability agendas as a form of university boosterism and stakeholder “capital,” rather than driving real change (Latter and Capstick, 2021; O'Neill and Sinden, 2021). Critically, the reality of the day-to-day, year-to-year operations of most remain tied to the competitive market place of research funding and student courses. Budgets have become increasingly performance based, and with public attention and scrutiny focused on performance and compliance, resources are concentrated in the best performing academic areas (Bleiklie et al., 2011). In this way the utilisation of intermediate means for intermediate ends appears to be the driving motivation and rationale for decisions.

Reflecting what has been termed “academic capitalism” (Slaughter and Leslie, 1997), the key performance metrics of most higher education institutions increasingly mimic those of short-term profit-maximisation corporations. Institutional wellbeing comes from maintaining or expanding the customer base, namely recruiting undergraduate and taught postgraduate students, especially higher-fee-paying students from abroad. Internationalisation, marketisation and commodification of educational programmes dictate the nature and direction of global engagement. Reputational prestige, and much valued additional income, comes from enhancing externally-funded research activity, including from contract research and commercialisation initiatives. Performance in national and international research and teaching rankings and league tables, alongside metrics around the likes of graduate employability, student satisfaction and widening participation, are seen as independent measures of the quality of the academic offering, allowing “customers” to differentiate between competitors and giving confidence that the product is delivering social value in the marketplace (Watermeyer, 2019; Reed and Fazey, 2021).

In terms of Daly's triangle, BAU universities and their strategic thinking are firmly focused on the central issue of survival over relatively short-term horizons. Their responsibility to addressing concerns of ultimate means are either: directly through their attention to reducing their own greenhouse carbon footprint; about improving energy efficiencies in their building stock, and generally greening their campuses; or by proxy through research efforts to better clarify the issues of climate change and degradation of the biosphere. In the main, they are driven ad hoc by where stakeholder pressure is the greatest (O'Neill and Sinden, 2021). The attention that CSR universities pay to ultimate ends is purely aspirational or based on compliance commitments such as: widening participation for less advantaged or marginalised groups; improving student and staff satisfaction; and to strengthening equality, diversity and inclusion. In reality, these activities represent a short-term reflex to relieve stakeholder pressure and retain the licence to operate, and thus their survival. In short, across most universities, the narrow and instrumentalised BAU focus on performance as tracked by rankings, profits and graduate income would seem to come at the expense of maximising real sustainability impact (O'Neill and Sinden, 2021). The Supplementary Table 1 to this paper outlines the archetypal impact related behaviour that would be expected from universities that are CSR, ESV or purpose-driven.

The ESV University

As universities begin to recognise the magnitude and urgency of the coupled socio-ecological crises there are signs of a genuine shift to long-term strategic thinking (e.g., Fazey et al., 2021; Tyndale et al., 2021). According to Sterling (2020), “…universities tend to be what might be called “inside out” institutions, concerned with all the normal parameters of university governance and operation, and secondarily looking to the external world. But current conditions are perhaps beginning to turn this around: some are becoming more “outside in” establishments, where massive contextual issues are precipitating a re-think on what universities can and should do…”.

This means that many universities are broadening their individual and collective horizons, even though carried out for self-interest. They are recognising that if they do not fundamentally reorient their research and teaching to focus on the urgent task of altering how society transforms resources and impacts society then their future survival is threatened (e.g., Crow 2010; Crow and Dabars 2015). More and more institutions are formalising public engagement activities to be more attentive to local community or broader society needs (e.g., Bell et al., 2021) and skilling academics to better communicate the real-world applicability of the work (Stewart and Hurth, 2021). This approach would seem consistent with an ESV logic and the third mission, suggesting that through their external engagement with non-traditional audiences, universities are becoming more “outside in” institutions who understand society's sustainability needs, recognise its problems and motivate solutions. Rather than being motivated by a fundamental intent to delivery for society and co-create the solutions, often universities retain a more arms-length approach to defining and accounting for their third mission activities (Loi and Di Guardo, 2015; Maassen et al., 2019), something which is symptomatic of the constraints of ESV organisational thinking.

Such actions, therefore, would not constitute a purpose-driven university. Academic external relations tend to remain less about directly satisfying public needs and more about better targeting their research messages to maintain and enhance the conventional model of business-as-usual knowledge production. To be genuinely purposeful, such external relations need to go much further, forming deep relationships with those they serve by developing a co-creative model of public engagement based on social learning and building an overtly interdisciplinary, participatory, reflexive, ethical and socially transformative academic culture (Fazey et al., 2021; Reed and Fazey, 2021).

In short, the transition to ESV will only take universities so far down the necessary innovation track. If decisions about impact are restricted by the over-arching desire to protect the university's survival, then the potential for genuine innovation and transformation towards sustainability will be fundamentally restricted. With ESV thinking, decisions to innovate towards sustainability will only be able to be justified within the governance system to the extent that they can be judged as a threat to long-term university viability and financialised success. Therefore, within an ESV approach it is hard to see how a university could develop the true reflexivity of thinking and whole-institution approach required to help society lead itself towards a sustainability future (Maxwell, 2021; Sterling, 2021).

The Purpose-Driven University

Arguably, no university has taken the lead from business and explicitly embarked on a purpose-driven journey, although papers in this special issue provide instructive examples of the innovations that would support such a repurposing. The Supplementary Table 1 presents indicative examples of archetypal arrangements and behaviours that might be expected in a purpose-driven university, but here we draw some general insights from the business experience.

Perhaps most critically, the experience in the business sector confirms that the move to purpose represents a significant and complex process of organisational transformation [Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership (CISL), 2020]. As publicly oriented institutions, universities might seem to be in a better position than commercial, shareholder-led corporations to embrace purpose, articulate the wellbeing outcomes they seek to address, and alter their organisational systems to deliver against them. However, many businesses, and business as a sector, appear further down the road on the journey to purpose. The emergence of genuinely purpose-driven businesses as a pivot away from unsustainable economic assumptions, under perhaps the most difficult of circumstances, means that rather than resisting closer alignment with business, purpose provides universities with a template for transformation. Universities can use this information to navigate the change, and support the co-creation of this important novel organisational form, drawing on tried and tested examples of this deep shift and adopting ideas on how to implement it [Haski-Leventhal, 2021]. Crucially, “purpose” offers a holistic conceptual framework for universities to learn from the business sector and rapidly apply their expertise and capacity for social and technological innovation at scale across society (Trencher et al., 2014). In the university context, that would involve blending the triple helix of academic missions (education, research and social engagement) under an overarching reason to exist that is a strategic contribution to the wellbeing of all people and planet in the long-term (sustainability).

A key lesson from business is that while the logical imperative to purpose may be sound and stakeholder support may be strong, the power structures and vested interest that stand to lose by such a transformation are likely to provide cultural inertia to such profound change. Furthermore, amid a wider cultural and legislative environment that has been optimised for financial income under BAU, concerted efforts are needed in order to optimise for impact around wellbeing outcomes. Daunted by this prospect, universities, like many businesses, might be tempted to continue along the BAU track; they may accommodate stakeholder demands by adopting a Corporate Social Responsibility approach. As a transitionary step, some may make the difficult step to Enlightened “Self” Value models, embedding long-term stakeholder-oriented decision-making. In both these cases, there is a risk that purpose is used, disingenuously, as a way of securing financial gain via stakeholder favour. But given the scale of the planetary crisis we face, the role of BAU in creating it, the radical paradigmatic change needed to avert crises, and the central leadership role universities play, it would therefore appear that becoming “purpose-driven” is the most adequate strategic response for universities.

Based on the business experience, the starting point for that strategic response is to fully understand what a purpose-driven university is likely to look like, in terms of cultural hardware and software, and to be able to analyse the gap between where a university is now and where they want and need to be. As in business, in universities it is likely that an appetite for deep-seated radical change will be found scattered throughout the organisation, especially amongst fresh faculty and the student body, but unleashing that potential to drive purposeful change through the entire institution will require university leaders to adopt purpose as a new organisational paradigm. This paper can only present the foundational proposition of purpose, though Supplementary Material to this paper (see Supplementary Table 1) provides an overview of the types of university behaviours that are legitimately and logically connected to the underlying organisational logics of purpose. For those university leaders—governing bodies and executive managers—asking “what are the first next steps I can take,” we offer insights informed by two empirical studies of the practises guiding purpose-driven firms [Ebert et al., 2018; Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership (CISL), 2020]. These seven key reflective questions form the starting behaviours that in business have helped initiate the radical and powerful change agenda that purpose embodies:

1 What Worldviews (Including Values) do We Really have and Which do We Want to Create?

As universities appear to be largely locked into BAU thinking then this suggests the lack of embedded critical “double loop” learning reflexivity needed to break through to a new paradigm (Sterling, 2004). This is deeply ironic, given that universities ought to be places where this deep level reflexivity about fundamental philosophical questions of society's meta purpose can be debated and solutions designed. To break this impasse will require exposure, examination and re-framing of doxic-level assumptions that have long-plagued universities, in the context of sustainability (Lozano et al., 2013; Maxwell, 2021; Sterling, 2021).

Using the insights of stakeholders (internal and external) to “hold up a mirror” for the company to understand itself is something noted by leading purpose-driven companies. University leaders will need to be clear about what stakeholder-informed process it will use to reveal, appraise and reconceptualise the individual worldviews, and associated structures, processes and behaviours that shape the university and work to move these towards worldviews aligned with the long-term wellbeing of all.

2 What is our University's Purpose?

The organisational purpose will be the reason the university exists, expressed as a strategic contribution of the university to long-term wellbeing for all (sustainability). University governing body and executive managers will need to use wide stakeholder engagement to thoroughly understand “long-term wellbeing for all” as the resonant context, appreciate how it is threatened, and decide what their university is best placed to focus its contribution on, given its attributes and particular context. This will give the leaders the basis to make explicit what value the university primarily seeks to create (its purpose); be able to justify why this is in the interest of long-term wellbeing; clarify how it will make sure that social and environmental systems and related capitals are protected and enhanced, and how wellbeing is delivered in a way that accords with its values.

As described above, universities are arguably the place where deep reflection about humanity's meta-purpose and how best to deliver on it can be focused on. Currently, the third mission only enables reflection at a myopic, abstracted level where concerns within the frame of BAU logic are of primary focus. With purpose, a university might question how it can enable society more broadly to reflect on these deeper questions about the meta purpose of humanity and beyond and then support operationalising this normative agenda in the economy and beyond.

3 How do We Assess What Value Our University is Currently Creating and Destroying?

In order to move from a statement of intent to a set of strategic objectives and policies for how the university as a whole can deliver the purpose, university leaders will need to understand their current and desired impacts on long-term wellbeing for all. Specifically, they will need to assess the nature of the impacts they create for social and environmental systems, and the associated capitals—the resources that wellbeing ultimately rests on and which are inputs into any organisational operating system. This means understanding direct and indirect (scope 3) impacts on wellbeing, and pathways to it, as a result of the knock-on effects of decisions. This also requires pinpointing how these impacts in turn come back to affect the university and the effects of uncertainty on its objectives (risk). Stakeholder engagement and scenario planning are useful ways to understand and predict impacts and create a consistently updated “theory of change” about how the purpose can best be achieved, forming the basis of strategic planning. The governing body can then devise strategic objectives, targets, measures and policies detailing parameters for the university to work to when devising and delivering strategy and addressing risk. These are vital to make sure that when achieving the purpose, the health of the resource base is not destroyed, and ideally is enhanced and that the manner in which the university delivers the purpose is ethical and based on sound information.

4 How can We Embed Purpose to Create the Value Intended, in the Way Intended?

The purpose, once defined, should serve as the touchstone for all decisions and can be used to help select amongst the myriad of sustainability “tools, initiatives and approaches” available to universities (Lozano, 2020). University leaders will need to make sure that decision-making at all levels is working towards achieving the purpose in the way intended and isn't, in fact, working against it or to some other assumed university objective. This involves understanding, and strategically adapting, the university's cultural hardware and software, including aligning rewards and incentives, recruitment, measurement and investment decision-making. Central to this will be building a “guide-and-co-create” marketing and communication culture which result in purpose-aligned products and services (what is researched, what courses exist, what consulting activities offer etc.), how they are made available and at what cost, and how they, and the university as a whole, is imbued with meaning via all related internal and external communications (Stewart and Hurth, 2021).

5 How do We Ensure Stakeholders, Including the Internal Academic Community, are Able to Support of Our Purpose?

To deliver a university purpose, the university leaders will need to have clarity about the nature of its stakeholders and how to engage with them and integrate their system wisdom into the ongoing decision-making throughout the university. They will need to be clear which are the “primary beneficiary stakeholders encompassed in the purpose,” which are the “enabling stakeholders” that support them in doing do and which are those stakeholders affected by the organisation in ways that may not be within strategic sight. As well as deeply understanding the pathways to wellbeing for primary beneficiary stakeholders, university leaders will need to ensure that they deeply understand their dependencies on their enabling stakeholders and what value needs to be distributed to them to ensure their ongoing health. For a BAU university (CSR or ESV), stakeholder relationships are likely to have been deliberately formulated so that they primarily support financialised outcomes. Persistent and strategic effort will be needed to understand, plan for and execute changes to this stakeholder constellation so that it is purpose-outcome optimised and not financial income optimised. This process should be an open and transparent one and allow for debate and challenge, particularly from the internal academic community who are those that need to have ownership of the purpose and capacity to deliver it. Stakeholder engagement should also be based on the recognition that by authentically existing to contribute to long-term wellbeing for all, a university can be a conduit for the deep desire of stakeholders, as humans, to help with this meaningful pursuit.

6 In What Ways are We Accountable to Society and Our Stakeholders for Our Purpose and How it is Delivered?

At the heart of becoming purpose-driven is accountability to society for the legitimacy of that purpose and in delivering it, in the way intended. University leadership will need to ensure it has a quality accountability system, based on transparency, that ensures that stakeholders (internal and external) have the information and accessibility they need to be able to critically support the university in achieving its purpose, question that purpose, and to be able to make informed decisions based on how the university acts. Research on leading purpose-driven businesses suggests that purpose provides the transparent touchstone for an organisation to make and defend difficult, but necessary, decisions and arbitrate amongst stakeholders where win wins have been exhausted. Hence, a robust accountability system should bring further clarity to the purpose and what it means in practise.

7 Is Our Governance Fit for Purpose?

Centrally, the university leadership needs to alter its governance system to be able to direct the purpose, oversee it and be accountable for it. ISO 37000 is the first global guide for organisational governance that has purpose and sustainability at its heart and can be used for reference. Without governance practise that is aligned with delivering a purpose-driven organisation it is highly unlikely that university transformation will be achieved or sustained.

Final Remark

All organisations, including universities, will be judged by future generations in terms of how they respond to the call for deep and rapid institutional transformation at this critical moment in time. Universities, like all other organisations—businesses, charities, and government—will require bold, vulnerable leadership and hard decisions. As the Wellbeing Economy and organisational purpose begin to transform notions of the economy and business as a driver of sustainability, rather than unsustainability, so organisational efforts and success will need to adapt. The urgency of the planetary crisis and the emerging global imperative of delivering wellbeing for all over the long-term, in a way that protects and enhances the underpinning social and environmental systems, is likely to become the foundational reason for universities to exist. In that context, the third mission provides the seeds of alignment of universities with the broader public good, but as currently conceived it is reinforcing a business-as-usual mindset that prioritises economic development and instrumentalises societal engagement. Using a shift to ESV as a step on the path may be wise—it will require long-term thinking to integrate research and teaching with more direct societal action, providing a more systemic and holistic approach to the relationship between universities and the local, regional and global communities they serve. However, for third mission seeds to grow into an overarching reason to exist that and authentically connects universities with society and sits above all three missions of research, education and social engagement, the old assumptions of the “Wellbeing Machine” need to be consciously shed. Instead, there needs to be whole scale alignment with the tenets of the emerging Wellbeing Economy. It seems, given the position we find ourselves in and the options available, that only by encompassing the academic three missions through the singular, long-term, motivating intent of purpose, and by learning quickly from business and other organisations about the practical challenges of purpose-driven transformation, can universities hope to play a truly central role in ensuring the wellbeing of life on earth in this critical decade.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsus.2021.762271/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Sir David King—interview with the University of Cambridge Judge Business School in June 2021 https://www.jbs.cam.ac.uk/insight/2021/the-climate-emergency/ Accessed 1 July 2020.

2. ^Flourishing/prosperity/ “good life” /needs fulfilment are all potential ways of capturing the essence of a eudaimonic expression of the ultimate positive human state, but wellbeing when used as a pinnacle outcome concept and not as short-hand for lower order input of mental health (e.g., health and wellbeing) is increasingly the concept used globally. Its definitions and pathways are necessarily under continual debate.

3. ^In Wales, the Welsh Assembly has also passed a Future Generations Act and created the post of Minister for Future Generations, showing that embracing the Wellbeing Economy consciously lengthens the time horizon for this wellbeing delivery to be overtly across generations (Davidson, 2021).

4. ^The definition of capitalism used here is “an economic system characterized by private or corporate ownership of capital goods, by investments that are determined by private decision, and by prices, production, and the distribution of goods that are determined mainly by competition in a free market” (Merriam-Webster, 2021).

References

Bauer, M., Rieckmann, M., Niedlich, S., and Bormann, I. (2021). Sustainability governance at higher education institutions: equipped to transform? Front. Sustain. 2:640458. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2021.640458

Bell, S., Lee, R., Fitzpatrick, D., and Mahtani, S. (2021). Co-producing a community university knowledge strategy. Front. Sustain. 2:661572. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2021.661572

Benneworth, P., and Jongbloed, B. (2010). “Who matters to universities? a stakeholder perspective on humanities, arts and social sciences valorisation.” High. Educ. 59, 567–588. doi: 10.1007/s10734-009-9265-2

Beynaghi, A., Trencher, G., Moztarzadeh, F., Mozafari, M., Maknoon, R., and Leal Filho, W. (2016). Future sustainability scenarios for universities: moving beyond the United Nations Decade of education for sustainable development. J. Cleaner Prod. 112, 3464–3478. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.10.117

Bhowmik, A. K., McCaffrey, M. S., Ruskey, A. M., Frischmann, C., and Gaffney, O. (2020). Powers of 10: seeking ‘sweet spots' for rapid climate and sustainability actions between individual and global scales. Environ. Res. Lett. 15:094011. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/ab9ed0

Biermann, F., and Pattberg, P. (2008). Global environmental governance: Taking stock, moving forward. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 33, 277–294.