- Department of Industrial Management, Faculty of Engineering and Sustainable Development, University of Gävle, Gävle, Sweden

Governance is instrumental to the implementing sustainability in organisations (civil society, companies, and public sector ones). Seven governance factors have been identified to achieve this: vision and mission, policies, reporting, communication, board of directors, department, and person in charge. However, their importance and interrelations are still under-researched. A survey was sent to 5,299 organisations, with 305 responses. The responses were analysed using descriptive statistics, rankings, comparison between organisation types, correlations, and centrality. The results provide the ranking of the factors, where vision and mission, person in charge, and reporting were highest ranked. The analysis also reveals that the seven factors are interrelated, albeit some more than others. The research provides a comparison of the rankings and interrelations between the organisation types. Each factor and its relation to other factors can contribute to better governance for sustainability, and better governance can contribute to a more holistic implementation of sustainability in organisations.

Introduction

Organisations, including civil societies, companies and public sector organisations (PSOs) have recognised that they need to go beyond traditional economic concerns and address economic, environmental, and social values in the short, medium, and long-terms (Rana and Chopra, 2019) to become more sustainability oriented (Ghosh et al., 2014; Horak et al., 2018). The number of research on organisations and sustainability has been increased over the last couple of decades (Petrini and Pozzebon, 2010; Horak et al., 2018; Lozano, 2018a,b; Nawaz and Koç, 2019), where the nature and purpose of an organisation will affect how it addresses sustainability (Soyka, 2012).

There have been a number of definitions of organisational sustainability, e.g., focussing on products and services with a base on efficiency and effectiveness (Rodríguez-Olalla and Avilés-Palacios, 2017), contributing to the economic, environmental, and social dimensions (Leon, 2013; Kim et al., 2016; Batista and Francisco, 2018). One of the most complete and holistic definitions is the one proposed by Lozano (2018b), which focuses on the four dimensions of sustainability (economic, environmental, social, and time), and the system elements (operations and production, organisational systems, service provision, strategy and management, assessment and reporting, and governance).

In general, the organisational sustainability literature has focused on companies (e.g., Dyllick and Hockerts, 2002; Schaltegger and Burrit, 2005; Tschopp, 2005; Pfeffer, 2010), followed by higher education (e.g., Dlouhá et al., 2013; Lozano et al., 2015). There has been increasing attention to how PSOs and other civil society organisations have been addressing sustainability (Guthrie and Farneti, 2008; Dumay et al., 2010; Lodhia et al., 2012; Domingues et al., 2017). There have been only a handful of papers that compare the types of organisations, e.g., drivers to change (Blanco-Portela et al., 2017; Lozano and von Haartman, 2018), circular economy approaches (Barreiro-Gen and Lozano, 2020); change management (Lozano and Garcia, 2020); and responses to COVID-19 (Barreiro-Gen et al., 2020).

Among the organisation's system elements, governance has been recognised as instrumental implementing sustainability in organisations (Jaimes-Valdez and Jacobo-Hernandez, 2016; Patterson et al., 2017; Sila and Cek, 2017; Arslan and Alqatan, 2020). The majority of research on governance for sustainability in organisation has been carried on companies, under the aegis of corporate social responsibility (CSR) (see Aras and Crowther, 2008; Petrini and Pozzebon, 2010), with limited work in other types of organisations, such as civil society and PSOs (Fuente et al., 2017). Seven governance factors have been identified to facilitate the implementation of sustainability into organisations (Sánchez et al., 2020); however, their importance and interrelations are still under-researched. This research is aimed at providing insights into these two topics.

This paper is structured in the following way: Section Literature Review discusses governance factors for organisational sustainability literature; Section Methods presents the methods used; Section Results presents results; Section Discussion discusses the results; and Section Conclusions draws conclusions from the study.

Literature Review

Seven governance factors that facilitate the implementation of sustainability into organisational practises have been identified (Sánchez et al., 2020), and summarised below1: (1) Vision and mission (Elkington, 2006; Lee et al., 2013; Amran et al., 2014; Patterson et al., 2017), also called institutional framework (Lozano, 2018a); (2) Policies (Klettner et al., 2014; Shrivastava and Addas, 2014; Glass and Newig, 2019); (3) Reporting (Krechovská and Procházková, 2014; Ortas et al., 2017), (4) Communication (Newig et al., 2013; Klettner et al., 2014; Becodo, 2018); (5) Board of Directors (BoD) (Salvioni et al., 2017; Mohamed Adnan et al., 2018; Sánchez et al., 2020); (6) Sustainability department (Ntim et al., 2017; Gennari, 2019); and (7) Person in charge (Mader et al., 2013; Bauer et al., 2018; Sánchez et al., 2020).

Vision and mission (including strategies) are one of the most discussed governance factors, which are used guidance in decision-making and daily business (Kiesnere and Baumgartner, 2019). Vision and mission statements are effective for establishment of sustainability structure (E-Vahdati et al., 2019). An organisation should include sustainability in its vision and mission to make it an integral part of the organisation's policies (Hahn, 2013). A vision and mission prepared with sustainability values enables an organisation to better adopt an effective strategy, considering organisational competencies and demands of the stakeholders (Amran et al., 2014). For example, companies, with their vision and mission are committed to the satisfaction of their stakeholders, providing better sustainability knowledge than those which are shareholder-oriented (Moneva et al., 2007), whereas a vision can help civil society organisation, such as higher education institutions (HEIs), to better implement sustainability (Lozano, 2013).

Policies are established to conduct an organisation's social relationship, and its effects of the organisation's activities, programs, and plans for sustainability (Moneva et al., 2007; Sánchez et al., 2020). Policies can help embedding sustainability into an organisation's culture, where sustainability should be integrated in the organisation's strategy and business model, and not as a separate policy (Klettner et al., 2014). For example, some companies have sustainability-related policy statements, as companies have investigated that expressing how they aim to address social expectations may play a key role in dealing with internal and external stakeholders (Hahn, 2013). The participation of several stakeholders and the commitment of leaders is helpful in making HEIs' policies more sustainable (Leal Filho et al., 2021).

Sustainability reporting is key in communicating an organisation's policies (Tregidga and Milne, 2006; Lee et al., 2013; Amran et al., 2014). Integrating sustainability into the vision or mission statement affects the quality of sustainability reporting, which provides guidance for actions and decision-making positively (Amran et al., 2014). A number of codes and guidelines have been introduced to foster sustainability in organisations (Juiz et al., 2014), such as the Cadbury Report in 1992 in the UK (Matei and Drumasu, 2015).

Communication has a significant role in informing an organisation sustainability efforts and their results (Kang and Kim, 2017), as well as creating an effective channel between the organisation and its stakeholders (Dyllick and Hockerts, 2002; Ortas et al., 2017). Communication between an organisation's leaders and its members can help to achieve goals, the vision and mission, and to provide sustainability information (Becodo, 2018). Communication is necessary to transfer information between different organisational level, including from the BoDs to the organisation (Petrini and Pozzebon, 2010). Organisations have used different mechanisms for communication: the creation of a network of employees; reporting and social balances that communicate socio- environmental performance; campaigns to promote socially responsible actions in the organisation; and training and education (Petrini and Pozzebon, 2010). Communication, as a governance factor, increases the effectiveness of conventional communication, while adopting progressive applications which contain a process for shareholders to communicate directly with members of the BoD (Becodo, 2018).

The BoD is key in integrating sustainability into an organisation's strategy (Kiesnere and Baumgartner, 2019). The BoD provides strategic guidance [such as vision, mission, and policy (Arslan and Alqatan, 2020)], effective monitoring of management, and accountability to the organisation and its shareholders (Matei and Drumasu, 2015). A BoD engaged with sustainability can result in better performance and are more likely to ease the flow of dialogue about sustainability issues in the organisation and to its stakeholders (Shrivastava and Addas, 2014).

In some organisations, a specific department, or committee, has been created to work with sustainability issues (Ghosh et al., 2014). Such department has a vital role in creating policies, targets, and objectives, and developing favourable strategies (Juiz et al., 2014; Domingues et al., 2017; Niedlich et al., 2020). A sustainability survey on the largest German companies indicated that CSR and sustainability, human resources and personnel, and management were the most frequently involved developments in social issues, whilst the CSR and sustainability and manufacturing, research and development, and public relations and communication departments were more involved in environmental topics (Schaltegger et al., 2014).

The person in charge, also referred to as champion (Niedlich et al., 2020), can influence an organisation's success (Sánchez et al., 2020), help to create a clearer sustainable structure (E-Vahdati et al., 2019), and promote the organisation commitment to sustainability (Krechovská and Procházková, 2014), especially when working closely with leadership (Lozano, 2006; Mader et al., 2013; Bauer et al., 2018).

Methods

A survey was developed to investigate the importance of how sustainability has been embedded in organisations, including governance. The survey was applied using the online survey tool (Qualtrics, 2018). The survey consisted of six sections:

1. Organisation characteristics, including country of origin, size, and product-service-focus

2. Role of sustainability for the organisation and role of the respondent in the company

3. Sustainability questions, including governance factors

4. Organisational change toward sustainability, and incorporation of sustainability

5. Stakeholders' role in the organisation's sustainability engagement

6. Role of the supply chain.

This paper is focussed on Sections Introduction and Methods, whereas other sections have been analysed in papers already published (see Barreiro-Gen and Lozano, 2020; Lozano, 2020; Lozano and Garcia, 2020). The survey was sent to a database of 5,299 contacts from different organisations obtained from the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) list of organisations worldwide, and personal contacts. In addition, 107 anonymous links were sent out. Three reminders were sent out, one in July 2018, one in September 2018 and one in October 2018. From the total list of emails, 616 emails bounced back. From the total number of organisations canvassed, 305 full responses were obtained for the governance part, i.e., a response rate of 6.51%.

The governance questions asked if the organisation's governance factors (Vision and mission, Policies, Reporting, Communication, BoD, Sustainability department, Person in charge) focused on sustainability issues, with the following possible answers on a 5-point scale: definitely not; probably not; might or might not; probably yes; or, definitely yes.

The data were analysed using descriptive analysis, the Friedman test for the importance of the factors (i.e., their relative ranking), Spearman correlations and centrality measures to assess their interrelations, and Kruskal-Wallis tests to analyse the differences between the factors for each organisational sector (Bryman, 2004; Jupp, 2006; Saunders et al., 2007). The Kruskal-Wallis test did not show any statistically significant differences between organisation size. The analyses were done using SPSS 24 (IBM, 2016) and yED (2009).

Limitations

The methods may have the following limitations. The wide scope of the survey, which tried to cover many topics of sustainability in organisations, might limit the internal validity of this study. The Likert scale may suffer from acquiescence problems and desirability. A non-response bias may be caused by companies from sectors which were contacted but refused to complete the survey. The number of respondents (305), most of them from Europe, may not allow a complete generalisation to all types of organisations and to other regions. The generalisability of results to all organisations may be limited to the application of a non-random sampling procedure, and the focus on companies listed in the GRI Disclosure Database with additional input from personal contacts and “snowballing” methods. Generalisability could be improved by a study based on a randomly selected sample drawn from the total number of organisations active in sustainability.

Results

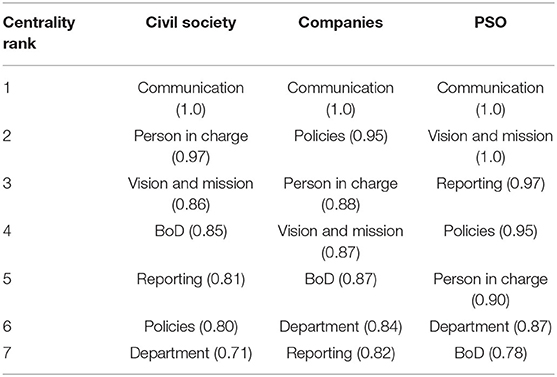

The respondents were companies (204), civil society (54), and PSOs (47). As Figure 1 shows the respondents' countries, where the majority were from European countries: Germany (39), Sweden (38), Spain (31), Netherlands (26), UK (15), Belgium (14), Austria (13), Italy (12), Finland (10), and Portugal (10).

Figure 1. Number of responses from the countries. Countries used are represented in varied colours, and in red the ones “No response.”

Ranking for All Organisations

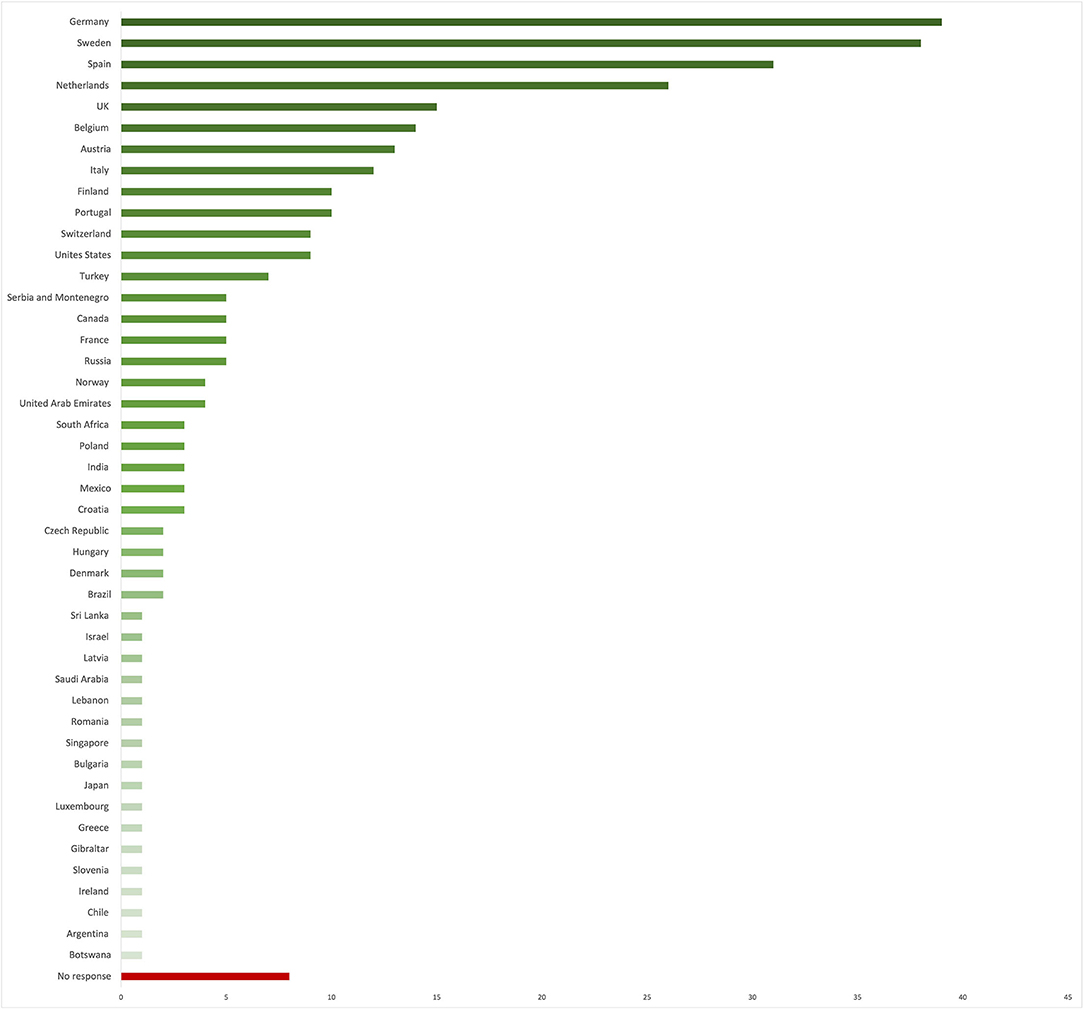

The overall importance of each governance factor for all organisations is presented in Figure 2, which shows that the vision and mission was ranked the highest (4.54), followed by person in charge (4.26), reporting (at 4.11), department and policies (3.93) and communication (3.88). The lowest ranked governance item was BoD with 3.35. The ranking results show that all the factors are important, albeit some more than others.

Figure 2. Ranking of the governance factors for all organisations (n = 305; Friedman test, p < 0.01).

Correlations of Governance Factors for All the Organisations

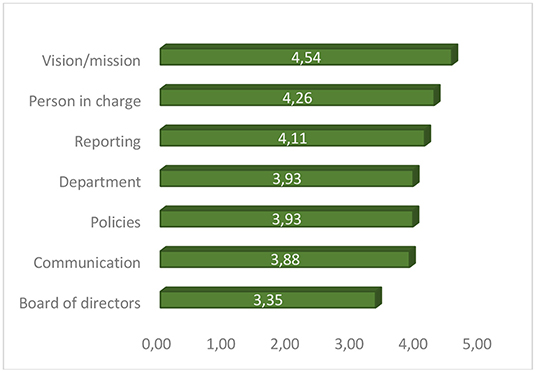

The correlation between governance factors in all organisations is presented in Table 1. The differences between the maximum (0.558) and the minimum (0.341) indicates that there are all interrelated, some more than others. The highest correlations (in green and more than 0.50) were: between policies and reporting; between person in charge and communication; between policies and BoD; between communication and policies; between vision and mission and BoD; between person in charge and department, and between person in charge and policies. The ones with medium correlation (in light green and between 0.45 and 0.50) were: between person in charge and reporting; between communication and reporting; between communication and vision and mission; between policies and vision and mission; between communication and BoD; and, between person in charge and vision and mission. Correlations between person in charge and policies, and between BoD and department are in white (between 0.40 and 0.45). The ones with the lowest value of correlation (lower than 0.40) between governance factors are highlighted in light red.

Table 1. Correlations between governance factors in all organisations (n = 305; Spearman Test at p < 0.01) Green indicates correlation above 0.5; light green between 0.45 and 0.5; white between 0.40 and 0.45, and red lower than 0.4.

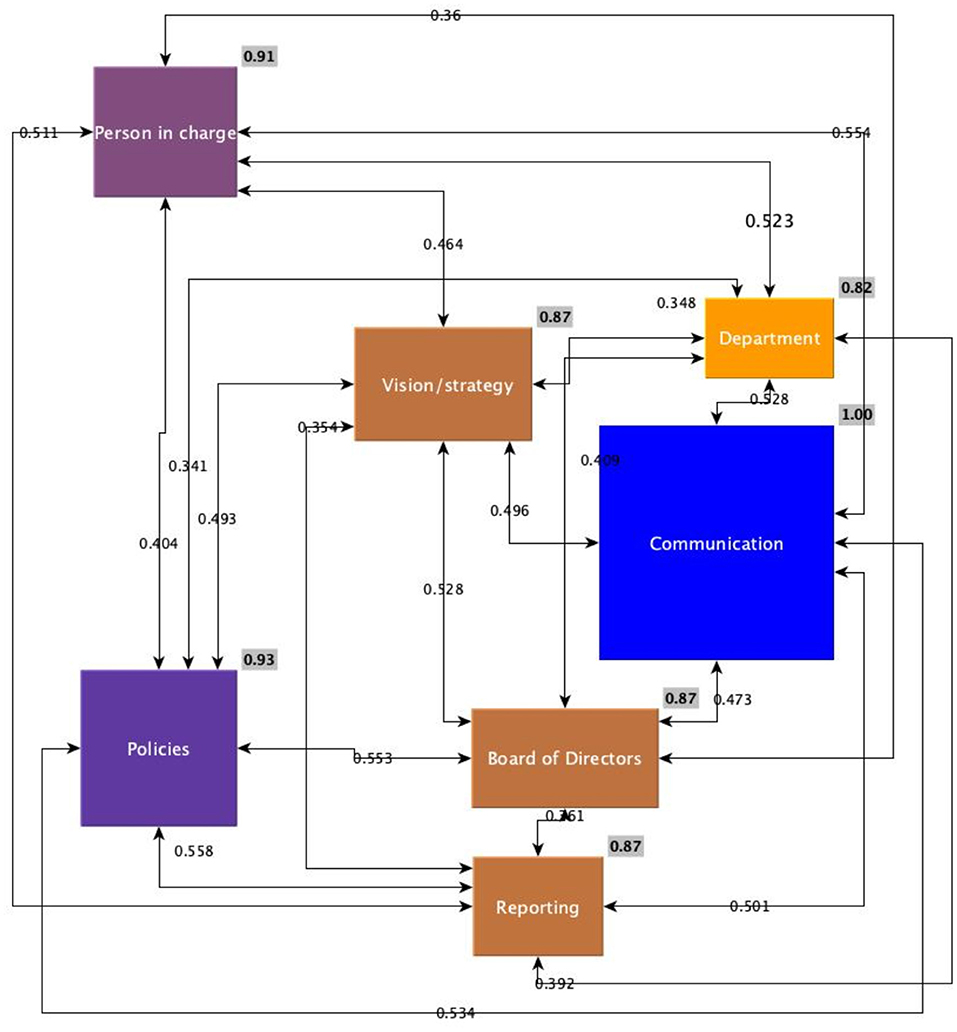

Figure 3 shows that communication had the highest centrality (1.00), which means that it is the most connected factor. It was followed by policies (0.93) and person in charge (0.91). The centrality was similar in BoD, vision and mission, and reporting (0.87). Department, with the lowest centrality (0.82) is the least connected governance factor.

Figure 3. Centrality network map of connections between governance factors. The bigger the node, the higher the strength of connections.

Comparison Between Organisation Types

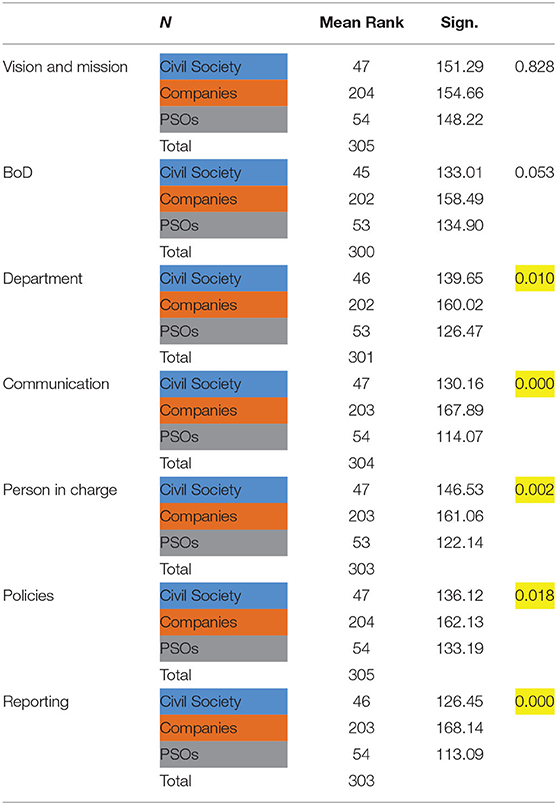

Table 2 shows the statistical differences between the governance factors and the three organisation types (civil society, companies, and PSOs). The test shows that there are statistically significant differences in five out of the seven factors of governance (i.e., policies, department, person in charge, communication, and reporting). It should be noted that companies had a higher mean rank in all the governance factors that showed statistical differences.

Table 2. Kruskal Wallis test on the organisation type for the governance factors with p < 0.05 highlighted in yellow.

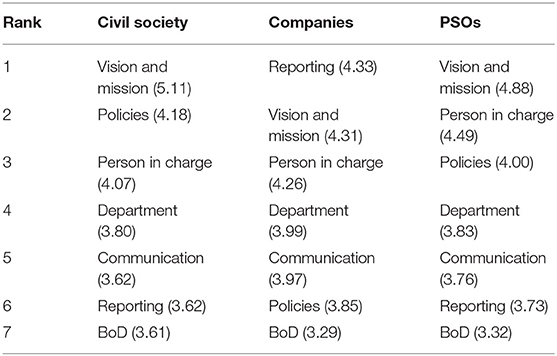

Ranking for Each Organisation Type

The ranking of the governance factors for each organisation type is shown in Table 3. Vision and mission was ranked at the top [the highest for civil society (5.11) and PSOs (4.88), and as the second most important governance item for companies (4.31)], whereas the lowest-ranked governance factor in the three type of organisations was BoD (3.29, 3.32, and 3.61 for companies, PSOs, and civil society, respectively), in line with the Kruskal-Wallis test.

Table 3. Ranking of the governance factors for sustainability in 3 type of organisations (n = 305; Friedman test, p < 0.01).

The largest factor difference between the organisation types were in policies, which was ranked in second and third position (in civil society and in PSOs, respectively) whereas it was in the sixth position in companies; and in reporting, which was ranked number one for companies and almost at the bottom for civil society and PSOs. The other factors were ranked in about the same position in the three types.

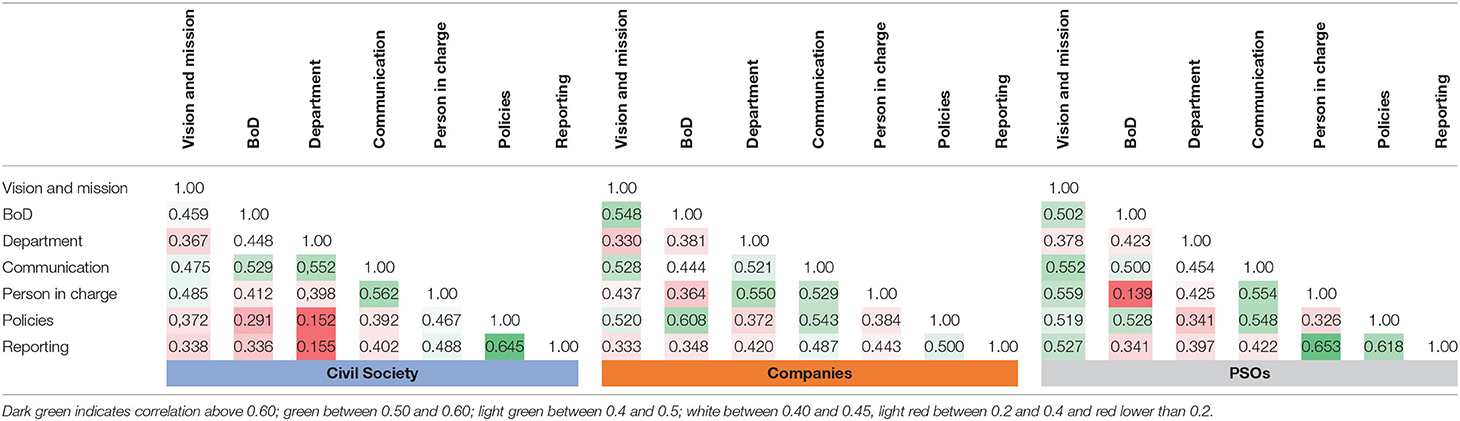

Correlations Between Different Organisation Types

Table 4 shows the correlations of the governance factors between the organisation types. There were positive correlations between most of the governance factors, where the highest correlations (in dark green and more than 0.60) were found between reporting and person in charge in PSOs (0.653), between policies and reporting in civil society (0.645) and in PSOs (0.618), and between policies and BoD in companies (0.608). The medium-high correlation (range from 0.50 to 0.60) between governance factors are highlighted in green. The ones with medium-low correlations are indicated in light green (between 0.50 and 0.45). Correlations between 0.40 and 0.45 are showed in white, whereas the correlations between 0.2 and 0.4 are highlighted in light red. The lowest correlations (in red and <0.20) were between person in charge and BoD in PSOs (0.139), between department and policies and between department and reporting in civil society (0.152 and 0.155, respectively). Communication had medium-high values in almost all correlation factors in each organisation type and department had, in average, low values.

Table 4. Correlations between governance factors in each organisation type (civil society, PSOs, companies) (n = 305; Spearman Rho Correlation Test, p < 0.01).

There were some differences in the correlation patterns comparing the three organisation types. Policies and reporting in civil society, for instance, had lower correlations with almost all governance factors than in companies and PSOs, whereas vision and mission had strongest correlations in PSOs than in the other types of organisation.

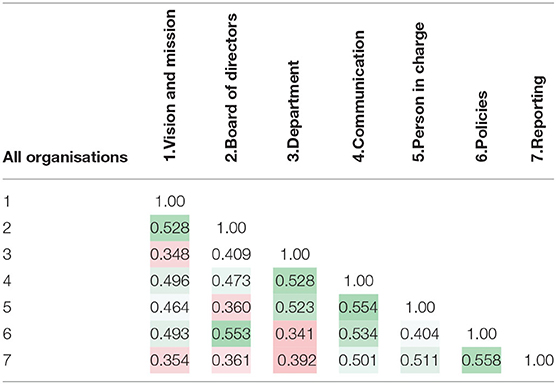

Table 5 shows that there were similar centrality patterns in governance factors for the three organisation types: communication had the highest centrality in the three of them (1.0), whereas Department had the lowest (or almost the lowest) centrality in each of these organisation types (0.71 in civil society, 0.82 in companies, and 0.87 in PSOs). There were some differences between the organisation types: civil society and companies had a similar pattern of centrality, except for policies, where in the former it was ranked number six and the latter number two. PSOs showed the highest differences in centrality measures, where vision and mission and reporting were ranked second and third and BoD the last one.

Discussion

The results provide insights into the ranking of the seven sustainability factors with vision and mission in first place, followed by person in charge, reporting, department, policies, communication, and BoD, which expands the governance factors discussions as proposed by Sánchez et al. (2020). The ranking results show that all the factors are important, albeit some more than others. It should be noted that BoD has received considerable attention in sustainability discourses (see Matei and Drumasu, 2015; Kiesnere and Baumgartner, 2019), but it was ranked the lowest, which may indicate that its importance may be overrepresented in academic discourses. This may also indicate that in practise, sustainability efforts and the required attention to sustainability are not sufficiently provided by the BoD (see Amran et al., 2014). Another reason may be that governance structures involving more people with different profiles may focus on other strategic issues more relevant to competitiveness and may not prioritise sustainability issues (as proposed by Sánchez et al., 2020).

The results show a more complete picture of the interrelations of the governance factors, complementing the indications of interrelations between factors, such as vision and mission and policies (see Hahn, 2013), reporting and policies (as discussed by Tregidga and Milne, 2006; Lee et al., 2013; Amran et al., 2014), communication and BoD (c.f. Becodo, 2018), and department and BoD (see Ghosh et al., 2014). The centrality analysis provides a more robust picture of the importance of the interrelations between the factors, where communication (although ranked in penultimate place), has the most central position.

The comparison between organisation types shows statistical differences in five of the seven factors (i.e., policies, department, person in charge, communication, and reporting), and no differences in vision and mission and BoD between the three types of organisation. The former is usually on the top rank, whereas the latter in the bottom one. The correlation analyses between the governance factors in three types of organisations indicate interrelations between them, and the centrality analyses show that there were some notable differences, especially in the case of PSOs. These results offer a broader perspective on governance in companies (see Aras and Crowther, 2008; Petrini and Pozzebon, 2010) and a new insights on civil society and PSOs (c.f. Fuente et al., 2017; Niedlich et al., 2020; Leal Filho et al., 2021).

Conclusions

Organisations have recognised that they can contribute to making societies more sustainable. Research on organisations' interest in sustainability issues has been increased over the last two decades. One of the essential elements to implement sustainability in organisations is governance; however, there has been limited research on its factors' importance and their interrelations. Despite the increasing number of studies on governance for sustainability in companies, there are only a few studies analysing governance in civil society and PSOs.

A survey was carried out to analyse factors of governance for organisational sustainability. The survey was sent to 5,299 organisations, with a response rate 6.51%. The results help to dissect governance into seven factors (vision and mission; policies; reporting, communication; 5) BoD; sustainability department; and person in charge. The results provide the relative ranking of these factors for all organisations, civil society, companies, and PSOs, as well as the factors interrelations.

This paper provides insights into sustainability governance in organisations by: (1) ranking of governance factors in organisations; (2) analysing the interrelations and centrality of the factors in organisations; and (3) comparing the rankings, the interrelations, and centrality of the factors between civil society organisations, companies, and PSOs.

A better understanding of governance factors and how they interrelate to each other can provide organisations with better structures to implement their sustainability efforts. Each factor and its relation to other factors can contribute to better governance for sustainability, and better governance can contribute to a more holistic implementation of sustainability in organisations.

Further research should be carried out on, for example, how communication can be improved in implementing sustainability in governance and organisations, on the relations between the governance factors, the differences between organisation sectors, and on governance in civil society and PSOs.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used for this article are not publicly available since they were generated for a larger project and used in separate publications. Partial access to the dataset (in particular to this research) may be provided. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Melis Temel, bWVsaXMudGVtZWxAaGlnLnNl.

Author Contributions

RL and MB-G: conceptualisation and supervision. MT, RL, and MB-G: methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation, and writing—review and editing. MT: investigation and visualisation. MT and MB-G: data curation. RL: project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1. ^Each governance factor's contribution to sustainability can be explained at length; however, for clarity and conciseness purposes the paper provides a summary of each.

References

Amran, A., Lee, S. P., and Devi, S. S. (2014). The influence of governance structure and strategic corporate social responsibility toward sustainability reporting quality. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 23, 217–235. doi: 10.1002/bse.1767

Aras, G., and Crowther, D. (2008). Governance and sustainability: an investigation into the relationship between corporate governance and corporate sustainability. Manag. Decis. 46, 433–448. doi: 10.1108/00251740810863870

Arslan, M., and Alqatan, A. (2020). Role of institutions in shaping corporate governance system: evidence from emerging economy. Heliyon 6:e03520. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03520

Barreiro-Gen, M., and Lozano, R. (2020). How circular is the circular economy? Analysing the implementation of circular economy in organisations. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 29, 3484–3494. doi: 10.1002/bse.2590

Barreiro-Gen, M., Lozano, R., and Zafar, A. (2020). Changes in sustainability priorities in organisations due to the COVID-19 outbreak: averting environmental rebound effects on society. Sustainability 12:5031. doi: 10.3390/su12125031

Batista, A. A. D. S., and Francisco, A. C. D. (2018). Organisattional sustainability practices: a study of the firms listed by the Corporate Sustainability Index. Sustain. 10:226. doi: 10.3390/su10010226

Bauer, M., Bormann, I., Kummer, B., Niedlich, S., and Rieckmann, M. (2018). Sustainability Governance at Universities : Using a Governance Equalizer as a Research Heuristic. Higher Educ Policy. 31, 491–511. doi: 10.1057/s41307-018-0104-x

Becodo, R. P. (2018). Governance Communication: A Primer (In the Context of Disaster Risk Reduction and Management). Ricky Palma Becodo.

Blanco-Portela, N., Benayas, J., Pertierra, L. R., and Lozano, R. (2017). Towards the integration of sustainability in Higher Education Institutions: a review of drivers of and barriers to organisational change and their comparison against those found of companies. J. Clean. Prod. 166, 563–578. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.07.252

Dlouhá, J., Huisingh, D., and Barton, A. (2013). Learning networks in higher education: universities in search of making effective regional impacts. J. Clean. Prod. 49, 5–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.01.034

Domingues, A. R., Lozano, R., Ceulemans, K., and Ramos, T. B. (2017). Sustainability reporting in public sector organisations: exploring the relation between the reporting process and organisational change management for sustainability. J. Environ. Manage. 192, 292–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.01.074

Dumay, J., Guthrie, J., and Farneti, F. (2010). GRI sustainability reporting guidelines for public and third sector organisattions: a critical review. Public Manag. Rev. 12, 531–548. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2010.496266

Dyllick, T., and Hockerts, K. (2002). Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 11, 130–141. doi: 10.1002/bse,.323

Elkington, J. (2006). Governance for sustainability. Corp. Gov. An Int. Rev. 14, 522–529. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8683.2006.00527.x

Fuente, J. A., García-Sánchez, I. M., and Lozano, M. B. (2017). The role of the board of directors in the adoption of GRI guidelines for the disclosure of CSR information. J. Clean. Prod. 141, 737–750. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.09.155

Gennari, F. (2019). How to lead the board of directors to a sustainable development of business with the CSR committees. Sustainability. 11:6987. doi: 10.3390/su11246987

Ghosh, S., Buckler, L., Skibniewski, M. J., Negahban, S., and Kwak, Y. H. (2014). Organisattional governance to integrate sustainability projects: a case study. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 20, 1–24. doi: 10.3846/20294913.2014.850755

Glass, L.-M., and Newig, J. (2019). Governance for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals: how important are participation, policy coherence, reflexivity, adaptation and democratic institutions? Earth Syst. Gov. 2:100031. doi: 10.1016/j.esg.2019.100031

Guthrie, J., and Farneti, F. (2008). GRI Sustainability Reporting by Australian Public Sector Organisattions. Public Money Manag. 28, 361–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9302.2008.00670.x

Hahn, R. (2013). ISO 26000 and the standardization of strategic management processes for sustainability and corporate social responsibility. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 22, 442–455. doi: 10.1002/bse.1751

Horak, S., Arya, B., and Ismail, K. M. (2018). Organisattional sustainability determinants in different cultural settings: a conceptual framework. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 27, 528–546. doi: 10.1002/bse.2018

Jaimes-Valdez, M. A., and Jacobo-Hernandez, C. A. (2016). Sustainability and corporate governance: theoretical development and perspectives. J. Manag. Sustain. 6:44. doi: 10.5539/jms.v6n3p44

Juiz, C., Guerrero, C., and Lera, I. (2014). Implementing Good Governance Principles for the Public Sector in Information Technology Governance Frameworks. Open J. Account. 3, 9–27. doi: 10.4236/ojacct.2014.31003

Kang, D., and Kim, S. (2017). Conceptual model development of sustainability practices: the case of port operations for collaboration and governance. Sustainability 9, 1–15. doi: 10.3390/su9122333

Kiesnere, A. L., and Baumgartner, R. J. (2019). Sustainability management in practice: organisattional change for sustainability in smaller large-sized companies in Austria. Sustainability 11:572. doi: 10.3390/su11030572

Kim, W., Khan, G. F., Wood, J., and Mahmood, M. T. (2016). Employee engagement for sustainable organisattions: keyword analysis using social network analysis and burst detection approach. Sustainability 8, 1–11. doi: 10.3390/su8010001

Klettner, A., Clarke, T., and Boersma, M. (2014). The Governance of corporate sustainability: empirical insights into the development, leadership and implementation of responsible business strategy. J. Bus. Ethics 122, 145–165. doi: 10.1007/s10551-013-1750-y

Krechovská, M., and Procházková, P. T. (2014). Sustainability and its integration into corporate governance focusing on corporate performance management and reporting. Procedia Eng. 69, 1144–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.proeng.2014.03.103

Leal Filho, W., Salvia, A. L., Frankenberger, F., Akib, N. A. M., Sen, S. K., Sivapalan, S., et al. (2021). Governance and sustainable development at higher education institutions. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 23, 6002–6020. doi: 10.1007/s10668-020-00859-y

Lee, K. H., Barker, M., and Mouasher, A. (2013). Is it even espoused? An exploratory study of commitment to sustainability as evidenced in vision, mission, and graduate attribute statements in Australian universities. J. Clean. Prod. 48, 20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.01.007

Leon, D. (2013). The sustainable knowledge-based organisation from a dynamic capabilities approach. Int. J. Learn. Intellect. Cap. 10:243.

Lodhia, S., Jacobs, K., and Park, Y. J. (2012). Driving public sector environmental reporting. Public Manag. Rev. 14, 631–647. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2011.642565

Lozano, R. (2006). A tool for a graphical assessment of sustainability in Universities (GASU). J. Clean. Prod. 14, 963–972. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2005.11.041

Lozano, R. (2013). Are companies planning their organisational changes for corporate sustainability? An analysis of three case studies on resistance to change and their strategies to overcome it. Corp. Soc. Respons. Environ. Manag. 20, 275–295. doi: 10.1002/csr.1290

Lozano, R. (2018a). Proposing a definition and a framework of organisational sustainability: a review of efforts and a survey of approaches to change. Sustainability. 10:1157. doi: 10.3390/su10041157

Lozano, R. (2018b). Providing a more holistic prespective on sustainable business models: Incorporating organisational theory principles. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 27, 1159–1166. doi: 10.1002/bse.2059

Lozano, R. (2020). Analysing the use of tools, initiatives, and approaches to promote sustainability in corporations. Corp. Soc. Respons. Environ. Manag. 27, 982–998. doi: 10.1002/csr.1860

Lozano, R., Ceulemans, K., Alonso-Almeida, M., Huisingh, D., Lozano, F. J., Waas, T., et al. (2015). A review of commitment and implementation of sustainable development in higher education: results from a worldwide survey. J. Clean. Prod. 108, 1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.09.048

Lozano, R., and Garcia, I. (2020). Scrutinizing sustainability change and its institutionalization in organisattions. Front. Sustain. 1, 1–16. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2020.00001

Lozano, R., and von Haartman, R. (2018). Reinforcing the holistic perspective of sustainability: analysis of the importance of sustainability drivers in organisattions. Corp. Soc. Respons. Environ. Manag. 25, 508–522. doi: 10.1002/csr.1475

Mader, C., Scott, G., and Abdul Razak, D. (2013). Effective change management, governance and policy for sustainability transformation in higher education. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 4, 264–284. doi: 10.1108/SAMPJ-09-2013-0037

Matei, A., and Drumasu, C. (2015). Corporate governance and public sector entities. Proc. Econ. Finance 26, 495–504. doi: 10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00879-5

Mohamed Adnan, S., Hay, D., and van Staden, C. J. (2018). The influence of culture and corporate governance on corporate social responsibility disclosure: a cross country analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 198, 820–832. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.07.057

Moneva, J. M., Rivera-Lirio, J. M., and Muñoz-Torres, M. J. (2007). The corporate stakeholder commitment and social and financial performance. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 107, 84–102. doi: 10.1108/02635570710719070

Nawaz, W., and Koç, M. (2019). Exploring organisattional sustainability: themes, functional areas, and best practices. Sustainability 11:4307. doi: 10.3390/su11164307

Newig, J., Schulz, D., Fischer, D., Hetze, K., Laws, N., Lüdecke, G., et al. (2013). Communication regarding sustainability: conceptual perspectives and exploration of societal subsystems. Sustainability 5, 2976–2990. doi: 10.3390/su5072976

Niedlich, S., Bauer, M., Doneliene, M., Jaeger, L., Rieckmann, M., and Bormann, I. (2020). Assessment of Sustainability Governance in Higher Education Institutions—A systemic tool using a governance equalizer. Sustainability 12:1816. doi: 10.3390/su12051816

Ntim, C. G., Soobaroyen, T., and Broad, M. J. (2017). Governance structures, voluntary disclosures and public accountability: the case of UK higher education institutions. Account. Audit. Account. J. 30, 65–118. doi: 10.1108/AAAJ-10-2014-1842

Ortas, E., Álvarez, I., and Zubeltzu, E. (2017). Firms' board independence and corporate social performance: a meta-analysis. Sustainability 9, 1–26. doi: 10.3390/su9061006

Patterson, J., Schulz, K., Vervoort, J., van der Hel, S., Widerberg, O., Adler, C., et al. (2017). Exploring the governance and politics of transformations towards sustainability. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transitions 24, 1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2016.09.001

Petrini, M., and Pozzebon, M. (2010). Integrating sustainability into business practices: learning from Brazilian firms. Braz. Adm. Rev. 7, 362–378. doi: 10.1590/S1807-76922010000400004

Pfeffer, J. (2010). Building sustainable organisattions: the human factor. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 24, 34–45. doi: 10.5465/AMP.2010.50304415

Rana, S., and Chopra, P. (2019). “Developing and sustaining employee engagement,” in Management Techniques for Employee Engagement in Contemporary Organizations, 142–164. doi: 10.4018/978-1-5225-7799-7.ch009

Rodríguez-Olalla, A., and Avilés-Palacios, C. (2017). Integrating sustainability in organisations: an activity-based sustainability model. Sustainability 9, 1–17. doi: 10.3390/su9061072

Salvioni, D. M., Franzoni, S., and Cassano, R. (2017). Sustainability in the higher education system: an opportunity to improve quality and image. Sustainability 9:914. doi: 10.3390/su9060914

Sánchez, R. G., Flórez-Parra, J. M., López-Pérez, M. V., and López-Hernández, A. M. (2020). Corporate governance and disclosure of information on corporate social responsibility: an analysis of the top 200 universities in the Shanghai ranking. Sustainability 12, 1–22. doi: 10.3390/su12041549

Saunders, M., Lewis, P., and Thornhill, A. (2007). Research Methods for Business Students, 4th Edn. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited.

Schaltegger, S., and Burrit, R. L. (2005). “Corporate sustainability,” in The International Yearbook of Environmental and Resource Economics 2005/2006, eds H. Folmer, and T. Tietenberg (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar), 185–222.

Schaltegger, S., Harms, D., Windolph, S. E., and Hörisch, J. (2014). Involving corporate functions: who contributes to sustainable development? Sustainability 6, 3064–3085. doi: 10.3390/su6053064

Shrivastava, P., and Addas, A. (2014). The impact of corporate governance on sustainability performance. J. Sustain. Finance Invest. 4, 21–37. doi: 10.1080/20430795.2014.887346

Sila, I., and Cek, K. (2017). The impact of environmental, social and governance dimensions of corporate social responsibility: Australian evidence. Proc. Comput. Sci. 120, 797–804. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2017.11.310

Tregidga, H., and Milne, M. J. (2006). From sustainable management to sustainable development: a longitudinal analysis of a leading New Zealand environmental reporter. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 15, 219–241. doi: 10.1002/bse.534

Tschopp, D. J. (2005). Corporate social responsibility: a comparison between the United States and the European Union. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 12, 55–59. doi: 10.1002/csr.69

Vahdati, E.-S., Zulkifli, N., and Zakaria, Z. (2019). Corporate governance integration with sustainability: a systematic literature review. Corp. Gov. 19, 255–269. doi: 10.1108/CG-03-2018-0111

Keywords: organisations, sustainability, governance factors, centrality analysis, companies

Citation: Temel M, Lozano R and Barreiro-Gen M (2021) Analysing the Governance Factors for Sustainability in Organisations and Their Inter-Relations. Front. Sustain. 2:684585. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2021.684585

Received: 23 March 2021; Accepted: 25 May 2021;

Published: 30 June 2021.

Edited by:

Irina Safitri Zen, International Islamic University Malaysia, MalaysiaReviewed by:

Elena Escrig Olmedo, University of Jaume I, SpainFrank Bezzina, University of Malta, Malta

Copyright © 2021 Temel, Lozano and Barreiro-Gen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Melis Temel, bWVzdGVsQGhpZy5zZQ==

Melis Temel

Melis Temel Rodrigo Lozano

Rodrigo Lozano Maria Barreiro-Gen

Maria Barreiro-Gen