- 1Centre for Climate Change and Social Transformations, Cardiff University, Cardiff, United Kingdom

- 2Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, Cardiff University, Cardiff, United Kingdom

- 3School of Psychology, Cardiff University, Cardiff, United Kingdom

On April 17, 2019, the University of Bristol became the first university in the United Kingdom (UK) to declare a climate emergency. Against a backdrop of high visibility and public concern about climate change, as well as climate emergency declarations from other sectors, another 36 UK universities followed suit over the next year. This paper explores what these climate emergency declarations show about how UK universities are responding to climate change and wider sustainability concerns, as well as how they view and present themselves in relation to this. Critical Discourse Analysis of the declarations allowed for in-depth scrutiny of the purpose and wider social context of the documents, demonstrating that they function as promotional statements, as presenting a collective voice, and showing a commitment from the universities to action. We argue that while these provide the potential for advancing sustainability within the sector, the tendency to use declarations as publicity and promotional material does detract from new commitments and action. The research contributes to the discussion around the role of universities as institutions with a responsibility both to act on climate change and to shape the broader societal response to it. It also provides insights as to how future research can evaluate universities in relation to their commitments and strategies, and provides suggestions to help ensure they live up to the promises and intentions that they have publicly made.

Introduction

Climate mitigation and progress on sustainability requires action across society, although some sectors have greater power—and obligation—to make an impact than others. With the autonomy (Collini, 2012) and expertise (Boulton and Lucas, 2008) to push for change, universities are in a privileged position. These institutions are uniquely situated to lead the way in responding to the climate and ecological emergency as they are multidisciplinary and collaborative, part of the local and national economy, able to think longer term, and provide a fertile space for discussion and debate (Katehi, 2012). This substantial potential to push for change is furthermore allied with universities' core functions of research and education (Harayama and Carraz, 2012; Bauer et al., 2018). The Higher Education sector represents a substantial share of economies worldwide (Calderon, 2018) and the UK reflects this wider trend, with 2.38 million students and almost 440,000 staff in UK Higher Education institutions in 2018–19 (Universities UK, n.d.).

Universities have made progress in addressing sustainability through measures such as sourcing renewable energy for their operations (Milligan, 2019), researching routes towards more sustainable societies (White, 2013) and considering global citizenship in education (Fiselier et al., 2017). Nevertheless, in terms of tackling their own carbon emissions, the scale and nature of change needed is substantial. Previously, the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE),1 set a target of 43% reduction in carbon emissions by 2020 against a 2005 baseline (HEFCE, 2010). However, Amber et al. (2020, p. 514) found this would be missed “by a huge margin” and that new policies and mechanisms are needed urgently to deal with this issue. Of the UK universities ranked in the People and Planet University League (2019a)—a student-led initiative that rates institutions on a range of indicators—only a third were on course to achieve their 2020 emissions targets (People and Planet, 2019b).

The action needed by universities goes beyond reducing emissions; as Sterling (2013) argues, sustainability must become part of their purpose, rather than it being tackled as an “add-on.” In a similar manner, Facer (2020) stresses that more profound change is needed in how universities operate, including through reconfiguring their operations and refocusing educational missions, in ways that help promote wider society's move away from unsustainable practises. This has not yet occurred to the extent needed to position sustainability concerns at the heart of the ethos and institutional purposes of Higher Education; Ralph and Stubbs (2014) suggest that universities have in many cases been behind government and industry in taking action, and Facer (2020) likewise argues that universities' civic role in relation to industry and communities needs reinvigorating (Facer, 2020). Leal Filho's et al. (2017) global study of universities found that the main barriers to sustainable development are institutional limits to their ability to enact rapid change, as well as sustainability issues not being prioritised, and the lack of dedicated structures to put solutions into practise. More far-reaching change will present challenges to universities, not least in reconciling their aim to be sustainable on the one hand, and international in their outlook and collaborations on the other (Glover et al., 2017). Ultimately, fully addressing sustainability and climate change raises questions about how universities operate and what purpose they serve. This includes whether they are prepared to advocate for substantial social, economic and cultural change for emissions reduction and sustainability, or see this as beyond the remit of “disinterested” scholarly work (Capstick et al., 2014).

One indication that the centrality of sustainability and climate concerns may be rising up the agenda of universities, has been the practise of declaring a “climate emergency.” Since the University of Bristol became the first UK university to declare a climate emergency on April 17, 2019, 36 others followed suit within a year, of a total of 161 UK universities (Amber et al., 2020). These declarations occurred at a time of unprecedented publicity and visibility of the climate crisis, with the UK public more worried about climate change than has been previously recorded (Capstick et al., 2019); despite even the impact of COVID-19, public concern has remained high (Whitmarsh, 2020). University students are also more worried about climate change than has been previously recorded (NUS, 2019).

Drawing attention to climate change in terms of an emergency suggests a recognition that fast and substantial action is needed. However, closer attention to these declarations is necessary, to understand how universities are responding to climate change both operationally and in a wider social context, how they are positioning themselves and their role in response to the climate emergency, and how these public-facing statements may differ between universities. The declarations made across UK universities have not previously been systematically analysed. This study aims to contribute to an understanding of how UK universities are addressing climate change. Scrutiny of what universities are saying and doing will contribute to an understanding of how change is taking place, and provides a basis for holding the sector to account for action on the climate crisis. While the present study focuses primarily on universities' climate emergency declarations, we also consider climate change to be a valuable focal point for exploring sustainability in a wider sense.

Methods

In order to systematically analyse the declarations, documents were collated from universities who declared a climate emergency between April 17, 2019 and April 16, 2020. This year-long period was deemed a suitable time period from the date of the first declaration, not least as the initially rapid rate of declarations began to slow into early 2020: whereas 14 universities declared during the first 3 months from mid-April 2019, only six did so in the final 3 months to mid-April 2020. Some universities made declarations as standalone announcements whereas others declared by signing the Global Universities and Colleges Climate Letter (hereafter referred to as the Climate Letter), a public online document organised by the Environmental Association for Universities and Colleges (EAUC), the climate action non-profit Second Nature, and the UN Environment Programme's Youth and Education Alliance (UN Environment, 2019); this declaration included the wording “we collectively declare a Climate Emergency” (SDG Accord, n.d.). Although 37 universities declared a climate emergency during this time, only 26 documents are included in this research: the Climate Letter and 25 standalone declarations. The universities are from across Great Britain and are distributed across the Times Higher Education (2020) rankings, with institutions in both the top and bottom ten (for further detail see Supplementary Material).

Standalone declarations were defined as documents where the main purpose was to declare a climate emergency, or which had a dedicated section within them doing so. One document per university was analysed. Documents which simply referred to the declaration or made mention of a climate emergency but whose main aim was not to make a declaration were not included. Declaring universities were identified either through the Climate Letter, a list of university sustainability commitments on the EAUC website or through news articles on the climateemergency.uk website. Further universities were identified via search engines using the terms “university” and variants of “climate emergency declaration.” Declarations were then obtained directly from university websites. The full list of universities that made a climate declaration during the 1-year time period are shown in Table 1.

The research applied a Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) method to analyse the declarations. This was used in order to reveal both what is conveyed in text and the way this is done, and additionally as it allows us to situate documents in the broader contexts in which they were created to provide a wider frame of reference. CDA is concerned with how language is used as a means of exercising different types of power (Fairclough et al., 2011). As Blackledge (2012, p. 617) puts this, “language is not powerful on its own, but gains power through the use powerful people make of it.” The analysis follows a three-step process outlined by Oswick (2013) which addresses:

1. The text dimension

2. The discursive practise dimension

3. The social practise dimension

Documents were read several times before commencing the analysis to ensure familiarity with the content. For step one, the text dimension, the documents were coded inductively over several iterations to identify recurrent topics and areas of emphasis. The analysis then proceeded to identify broader, over-arching themes. Having identified three main themes, the analysis proceeded to step two, the discursive practise dimension. This considered the author, audience, stakeholders, and where and when the documents were published. These sensitising questions are recommended by Oswick (2013) to look beyond the content and provide insights into the wider context in which documents are produced and consumed. The third step, the social practise dimension, considered power and the broader institutional and societal landscape. This complements the first two steps by considering factors relevant to universities: for example, concerning reputation, their core business, and civic responsibility. This drew on insights from the literature to understand how the declarations interact with wider landscape in which universities function and how the declarations demonstrate power.

The Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) used in this study is grounded in a critical theory approach. Critical theory consists of four main elements: an ontology that states that social reality is constructed; an emphasis on power and ideology; internal and external connections and contexts; and reflection and suggestions for change (Prasad and Caproni, 1997). The epistemological position for the present research is therefore that it sees truth or meaning as “constructed” – that is, assembled through the use of language and other symbols. CDA views text in documents as being particularly important, as the language used within them creates and mediates social action (Lee, 2013), for example by shaping institutional narratives or priorities. A critical theory approach can be used to understand the nature and operation of organisations (Symon and Cassell, 2013); in the case of the present research, the elements outlined above are used to understand the climate emergency declarations of universities in order to scrutinise how they are responding to climate change. Further detail about CDA and the analytic approach is provided in the Supplementary Material.

Results

Aside from carbon neutral targets, the Climate Letter provides no information about the individual signatories. Therefore, the results mainly draw from the standalone declarations.

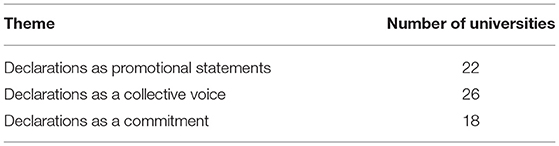

The analysis identifies three overarching themes. We highlight how these function as promotional statements, as demonstrating a collective voice, and as showing a commitment to action. See Table 2 for a summary of the distribution of universities across each theme.

Declarations as Promotional Statements

The declarations function, firstly, as promotional statements about the universities' achievements on climate change and broader related issues. Many of the universities highlighted work that they have previously done, that was ongoing or that would be taking place in future.

Examples of promotional statements identified within declarations include the following:

“Keele University launched its new Institute for Sustainable Futures last year.” (Keele University, 2019).

“For many years, the University has been deeply committed to social, environmental and financial sustainability at a strategic and operational level.” (Canterbury Christ Church University, 2019).

“Between 2009 and 2018 we produced 9,209 publications relating to Sustainable Development Goal 13: Climate Action.” (University of Manchester, 2019).

As can be seen from the statements above, despite the declarations ostensibly being concerned with the climate emergency, there was a clear sense in which they sought to draw attention to the reputation and good name of declaring institutions.

The university's role in research and education was frequently mentioned, and focused typically on the content of curricula and type of research carried out (e.g., conservation), as opposed to research or educational practises (such as internationalism or long-haul travel). Staff and student practises, awareness and engagement were mentioned but to a lesser extent; the main focus across the declarations was on operations, research and education. Although there is a clear focus on climate change, 14 of the universities referred specifically to animals and/or nature, with four declaring an ecological, biodiversity or environment and climate emergency. This suggests that these universities sought to publicly acknowledge and give weight to these related issues.

A clear indicator of the promotional function of declarations, was their use to show leadership in climate change and sustainability through awards and rankings, subject expertise and being the “best” or “first” at something. There were explicit mentions of leadership, both current and aspirational, for the university as a whole as well as researchers and students, as illustrated by the following statements:

“Lauren McDougall, President of the Students' Representative Council (SRC), commented: ‘Students at the University of Glasgow feel passionately about the issue of climate change and want their institution to play a lead role in tackling it.”' (University of Glasgow, 2019).

“We have some of the best teams anywhere in the world working on climate change and the environment.” (University of Exeter, 2019a).

“This builds on the university's long-standing commitment to sustainability which has.seen it receive a first-class award every year since 2012 from the People & Planet University Green League” (University of Brighton, 2020).

This emphasis on leadership is designed to showcase universities' proficiency and the recognition that they have received for their efforts. Such leadership was often framed in an international context, reflecting the priorities of the university sector to be successful globally, not only for research and education but also for sustainability issues.

The placing of the publication of declarations, as well as their content, also shows them to have a strong promotional aspect. The majority of declaration announcements were published as public-facing news articles on universities' websites. This indicates the intended audience was not only staff and students, but also aimed at wider stakeholders and the general public. Many of the declarations were mentioned in local and national press, enabling a wider public reach and promotional function for universities (e.g., Falmouth Packet, 2019; Walker, 2019).

The timing of the declaration announcements also points towards their promotional function. Following the University of Bristol's initial declaration, a concentrated series of declarations were made, particularly in the first 6 months. Some universities made their declarations on specific days where more publicity was likely: four declared on September 20, 2019, the start of a week of international climate change strikes, and one declared on World Environment Day 2019. These declarations were made at a time when climate change and the climate emergency were very much in the public eye, suggesting an ideal time for universities to demonstrate their achievements in this area.

Declarations as a Collective Voice

The declarations are used to demonstrate both internal and external togetherness: that the universities are part of a bigger whole and that there is attention to this topic across the sector. Many universities stated that they were joining with others in the UK and around the world in declaring a climate emergency. As with the expressions of leadership, there was an international focus by many universities. Framing the declarations in this way gives a collective voice to the universities, even though many of the declarations were made separately and there is a clear element of competition shown by their emphasis on leadership. As so many of the declarations were announced during a short period of time and others by way of the Climate Letter, this also gives them a collective voice. Examples of this feature are illustrated by the following statements:

“Aberystwyth University has joined organisations around the world in declaring a climate emergency.” (Aberystwyth University, 2019).

“We all need to work together to nurture a habitable planet for future generations.” (Climate Letter; SDG Accord, n.d.).

“The University of Plymouth has declared a climate emergency, joining an international movement.” (University of Plymouth, 2019).

The universities appear keen to demonstrate that others have already declared a climate emergency, even the University of Bristol (2019), which was the first university in the UK to do so. By framing their announcements in this way, the universities give more legitimacy to their declarations through showing they are part of a wider initiative.

Staff and students are mentioned in almost all of the declarations and are positioned as key collaborators in relation to climate change and sustainability. There are also specific mentions of the Student Unions supporting the universities' actions, working with them or jointly declaring a climate emergency.

“Bath Spa University and its Students' Union have joined forces to declare a climate emergency.” (Bath Spa University, 2020).

“Professor Juliet Osborne, Director of the Environment and Sustainability Institute, will be chairing a working group bringing together staff and students.” (University of Exeter, 2019a).

“A comprehensive action plan will be drawn up in consultation with staff and student unions.” (Goldsmiths, 2019).

Staff and students are often positioned as active and independent stakeholders as well - raising awareness, showing concern, pushing for action and providing ideas, though students are positioned in this way to a greater extent; for example as in the University of Sussex's (2019) declaration: “in declaring a climate emergency, our students and supporters will hold us to account for our own actions.” External stakeholders are also mentioned, but to a lesser extent and depth than internal stakeholders. This suggests that although the declarations are public, they focus on demonstrating the importance of their internal stakeholders who are likely to be most attentive to the declarations.

Declarations as a Commitment

The declarations function as a way to demonstrate the universities' commitment to tackling climate change in tangible ways such as policies, targets and committees, as well as talking broadly about action and commitment. Many of the universities referred to the severity and urgency of climate change, with their commitments used as a way of demonstrating that they understand this, as in the phrasing used by Liverpool John Moores University (2020): “We are deeply committed to playing our part at this critical time.”

While much of the wording of the declarations is promotional, as described above, many nevertheless include action-oriented statements. Six universities explicitly addressed the need to go beyond words and take action (Cardiff University, 2019; Falmouth University, 2019; Goldsmiths, 2019; University of Exeter, 2019a; University of Sussex, 2019; University of Warwick, 2019), for example:

“We must…work together to help move us on from making this declaration to a comprehensive plan of action.” (Cardiff University, 2019).

Commitment was also demonstrated through more tangible outcomes or objectives. Most universities mentioned specific targets or goals, mainly for becoming carbon neutral or reaching net zero; this is also referred to in the Climate Letter, signed by 20 of the universities. For example, Keele University (2019) “announced an ambitious climate emergency target to be carbon neutral by 2030.” In some cases, universities also stated their intentions to incorporate sustainability more deeply into the university's practises and some referred to sustainability being at the “heart” of the university (University of Manchester, 2019; University of Plymouth, 2019; University of Winchester, 2019). The notion of more transformative change to the universities' modes of operation and ethos was only occasionally touched upon, however, as in the following example:

“Through this declaration, Birmingham City University commits to putting in place a programme that will deliver a transformed university.” (Birmingham City University, 2019).

Both current and future internal committees, groups and boards were mentioned, though to a lesser extent than targets and documents. In many cases, Vice Chancellors' statements are used to convey the commitment at senior level to the declaration. All of these tangible outcomes and practises demonstrate ways in which the universities' actions are made legitimate and can be scrutinised in future.

Discussion

Since late 2018 there has been a sustained and high level of publicity around climate change in the UK, including through media coverage of the IPCC's (2018) 1.5°C special report, Sir David Attenborough's television programme “Climate Change – The Facts” (BBC, 2019), as well as widely-reported school strikes and large-scale protests. The heightened visibility of climate change has been unprecedented and unexpected. As well as contributing to, and reflecting, a substantial increase in public concern (Capstick et al., 2019), it has paved the way for increased pressure on and by civil society, including universities. Although it is difficult to know the exact mechanisms driving each university's declaration, it is clear that this wider social context, as well as the growing interest in climate emergency declarations, has been influential.

In their declarations, the universities address the main barriers to sustainable development identified by Leal Filho et al. (2017) to varying degrees, in terms of reflecting their institutional priorities and structures. By way of a public declaration and the language used to describe climate change and sustainability, they clearly give a heightened importance to tackling it. By framing it as an emergency they suggest that rapid action needs to be taken, and some have announced dedicated structures to do so. This demonstrates that universities do, on the face of it, appear to be firmly committed to action and to be pursuing this towards addressing sustainability.

The emphasis on research and education in the declarations, as well as frequent mention of their international focus, demonstrates that universities are, to some extent, linking climate change to their core roles and interests. This reflects Chapleo et al.'s (2011) findings about how universities brand themselves on their websites. However, while the declarations typically suggest that universities want to be seen as leaders, none go as far as to suggest re-purposing universities, with only a small number mentioning sustainability being at their heart, or other indicative language of more transformative change. In light of this, there remains a risk that climate change and sustainability are seen as “add-ons” or peripheral to their core business; in this, they would appear to conform to Huisman and Mampaey's (2018, p. 437) argument that universities are more comfortable with “legitimised action” and are unwilling to stand out on more fundamental questions that could be asked of the Higher Education sector in a time of climate emergency.

Even with respect to achieving emissions reductions from operations, setting targets does not necessarily mean they will be achieved – as is indicated by progress to date in the form of HEFCE (2010) and People and Planet (2019b) data for universities. It is nevertheless encouraging that many declarations also mentioned more concrete action and plans beyond target-setting. One promising example in this vein, is that by the University of Exeter (2019b), which published an Environment and Climate Emergency Working Group White Paper 6 months after their announcement, explicitly stating that this came about as a result of their declaration.

Although these declarations tell us about the image that the universities are trying to portray, the present research is limited in that it cannot show the internal workings of the universities either in the lead up to making the declarations nor what action they have taken after doing so – in this sense the analysis carried out here should be seen primarily as a snapshot of universities' public-facing intentions and perspectives at a critical juncture in society's response to the climate emergency. This has implications for future research that could identify which actions universities have taken following their declarations, such as whether they use their collective voice on this issue and achieve the emissions reductions to which they have committed. This will demonstrate whether momentum has been maintained – particularly given the shocks to the sector experienced from COVID-19.

Conclusion

This research sought to identify what UK universities' climate emergency declarations show about how they are addressing climate change. Our analysis found some revealing contrasts in how universities position themselves. There is a competitiveness in how the declarations are used as promotional statements, yet there is also a clear interest in showing that individual universities are part of a greater whole. From their emphasis on a collective voice, the declarations suggest that universities are seeking to emphasise that the climate emergency is a shared problem. The difference between how the universities declared may also indicate a variability in their interest in publicity. While the Climate Letter, signed by many declaring universities, contains clear commitments and recognition of the climate emergency, for those universities that only signed that pre-written letter this arguably indicates less ambition and expectation of scrutiny than a standalone announcement.

It remains to be seen what impact the climate emergency declarations will have, over and above any action that universities were already taking on climate change. Universities should be commended for their public commitment to take climate change seriously, but as Falmouth University (2019) states, these declarations “must be more than warm words” if universities are to be taken seriously. There remains an important difference between the specific commitments in the declarations, and arguments for more far-reaching reorientation of purpose and practise of the sector. Staff and students are frequently mentioned within universities' declarations, and it is likely—indeed essential—that universities will be held to account by these groups for the level of action they pursue following their declarations. The declaration of a climate emergency is only a starting point, but provides a firm basis for demanding institutions live up to the promises and aspirations they have put forward.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions generated for the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

BL developed the research, ideas and methodology and carried out the analysis. SC supervised the research, helped shape the analysis, and revised the article. BL led in writing the article with input from SC. All authors approved the submitted version.

Funding

The open access fee for this article was paid for by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC): grant reference ES/S012257/1.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Christina Demski and Dr. Sarah Mander as co-supervisors of the research.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsus.2021.660596/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Now replaced by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) and Office for Students.

References

Aberystwyth University (2019). Aberystwyth University Declares Climate Emergency and Commits to Reducing Fossil Fuel Investments. Available online at: https://www.aber.ac.uk/en/news/archive/2019/11/title-227209-en.html (accessed January 26, 2021).

Amber, K. P., Ahmad, R., Chaudhery, G. Q., Khan, M. S., Akbar, B., and Bashir, M. A. (2020). Energy and environmental performance of a higher education sector – a case study in the United Kingdom. Int. J. Sustain. Energy 39:5. doi: 10.1080/14786451.2020.1720681

Bath Spa University (2020). Bath Spa University Joins Forces With Students' Union To Declare Climate Emergency. Available online at: https://www.bathspa.ac.uk/news-and-events/news/climate-emergency-declaration (accessed January 26, 2021).

Bauer, M., Bormann, I., Kummer, B., Niedlich, S., and Rieckmann, M. (2018). Sustainability governance at universities: using a governance equalizer as a research heuristic. High. Educ. Policy 31:4. doi: 10.1057/s41307-018-0104-x

BBC (2019). David Attenborough Climate Change TV Show a ‘Call to Arms'. Available online at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-4798833 (accessed January 26, 2021).

Birmingham City University (2019). Declaration of Climate Emergency. Available online at: https://bcuassets.blob.core.windows.net/docs/20190920bcuclimateemergencystatement-132235705426425876.pdf (accessed January 26, 2021).

Blackledge, A. (2012). “Discourse and power,” in The Routledge Handbook of Discourse Analysis, eds. J. P. Gee and M. Handford (Oxon: Routledge), 616–627.

Calderon, A. J. (2018). Massification of Higher Education Revisited. Melbourne: RMIT University. Available online at: http://cdn02.pucp.education/academico/2018/08/23165810/na_mass_revis_230818.pdf (accessed January 2021).

Canterbury Christ Church University (2019). Christ Church Declares a Climate Emergency. Available online at: https://www.canterbury.ac.uk/news/news.aspx?id=aa3b543e-9c2d-46b0-90f8-82b2be788bca (accessed January 26, 2021).

Capstick, S., Demski, C., Poortinga, W., Whitmarsh, L., Steentjes, K., Corner, A., et al. (2019). “Public opinion in a time of climate emergency,” in: CAST Briefing Paper 02.

Capstick, S., Lorenzoni, I., Corner, C., and Whitmarsh, L. (2014). Prospects for radical emissions reduction through behavior and lifestyle change. Carbon Manag. 5:4. doi: 10.1080/17583004.2015.1020011

Cardiff University (2019). Cardiff University Declares Climate Emergency. Available online at: https://www.cardiff.ac.uk/news/view/1730638-cardiff-university-declares-climate-emergency (accessed January 26, 2021).

Chapleo, C., Carrillo Durán, M. V., and Castillo Díaz., A. (2011). Do UK universities communicate their brands effectively through their websites? J. Mark. Higher Educ. 21:1. doi: 10.1080/08841241.2011.569589

Facer, K. (2020). “Beyond business as usual: higher education in the era of climate change,” in: HEPI Debate Paper 24.

Fairclough, N., Mulderrig, J., and Wodak, R. (2011). “Critical discourse analysis,” in Discourse Studies: A Multidisciplinary Introduction, ed. T. A. Van Dijk (London: SAGE Publications Ltd.), 357–378.

Falmouth Packet (2019). Falmouth University Declares Climate Emergency. Available online at: https://www.falmouthpacket.co.uk/news/17719770.falmouth-university-declares-climate-emergency (accessed January 26, 2021).

Falmouth University (2019). Falmouth University Declares Climate & Ecological Emergency. Available online at: https://www.falmouth.ac.uk/news/falmouth-university-declares-climate-ecological-emergency (accessed January 26, 2021).

Fiselier, E. S., Longhurst, J. W. S., and Gough, G.K. (2017). Exploring the current position of ESD in UK higher education institutions. Int. J. Sustain. Higher Educ. 19:2. doi: 10.1108/IJSHE-06-2017-0084

Glover, A., Strengers, Y., and Lewis, T. (2017). The unsustainability of academic aeromobility in Australian universities. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 13:1. doi: 10.1080/15487733.2017.1388620

Goldsmiths (2019). Goldsmiths' New Warden Pledges Action on Climate Emergency. Available online at: https://www.gold.ac.uk/news/carbon-neutral-plan/ (accessed January 26, 2021).

Harayama, Y., and Carraz, R. (2012). “Addressing global and social challenges and the role of university,” in Global Sustainability and the Responsibilities of Universities, eds. L. E Weber and J. J. Duderstadt (France: Economica Ltd.), 85–96.

HEFCE (2010). Carbon Reduction Target and Strategy for Higher Education in England. Bristol, UK: HEFCE.

Huisman, J., and Mampaey, J. (2018). Use your imagination: what UK universities want you to think of them. Oxford Rev. Educ. 44:4. doi: 10.1080/03054985.2017.1421154

IPCC (2018). “Summary for Policymakers,” in Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5°C Above Pre-industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty, eds V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, et al. (Geneva, IL: IPCC).

Katehi, L. P. B. (2012). “A university culture of sustainability: principle, practice and economic driver,” in Global Sustainability and the Responsibilities of Universities, eds. L. E. Weber and J. J. Duderstadt (France: Economica Ltd.), 117–128.

Keele University (2019). Keele University Declares ‘Climate Emergency'. Available online at: https://www.keele.ac.uk/discover/news/2019/may/climate-emergency/sustainability.php (accessed January 26, 2021).

Leal Filho, W., Wu, Y.J., Brandli, L.L., Avila, L.V., Azeiteiro, U.M., Caeiro, S., et al. (2017). Identifying and overcoming obstacles to the implementation of sustainable development at universities. J. Integrat. Environ. Sci. 14:1. doi: 10.1080/1943815X.2017.1362007

Lee, B. (2013). “Using documents in organizational research,” in Qualitative Organizational Research: Core Methods and Current Challenges, 2nd Edn. eds. G. Symon and C. Cassell (London: SAGE), 389–407.

Liverpool John Moores University (2020). LJMU Declares Climate Emergency. Available online at: https://www.ljmu.ac.uk/about-us/news/articles/2020/2/7/ljmu-declares-climate-emergency (accessed January 26, 2021).

Milligan, R. (2019). Collaborative Clean Energy Deals: Universities Lead the Way. Available online at: https://energysavingtrust.org.uk/blog/collaborative-clean-energy-deals-universities-lead-way (accessed January 6, 2021).

Oswick, C. (2013). “Discourse analysis and discursive research,” in Qualitative Organizational Research: Core Methods and Current Challenges, 2nd Edn. eds. G. Symon and C. Cassell (London: SAGE), 473–491.

People Planet (2019a). People & Planet University League. Available online at: https://peopleandplanet.org/university-league (accessed January 26, 2021).

People Planet (2019b). Press Release 2019. Available online at: https://peopleandplanet.org/university-league/press (accessed January 6, 2021).

Prasad, P., and Caproni, P. (1997). Critical theory in the management classroom: engaging power, ideology, and praxis. J. Manag. Educ. 21:3. doi: 10.1177/105256299702100302

Ralph, M., and Stubbs, W. (2014). Integrating environmental sustainability into universities. Higher Educ. 67:1. doi: 10.1007/s10734-013-9641-9

SDG Accord (n.d.). Global Climate Letter for Universities Colleges. Available online at: https://www.sdgaccord.org/climateletter (accessed January 27 2021).

Sterling, S. (2013). “The sustainable university: challenge and response,” in The Sustainable University: Progress And Prospects, eds. S. Sterling, L. Maxey and H. Luna, (London: Routledge), 17–50.

Symon, G., and Cassell, C. (2013). Qualitative Organizational Research: Core Methods and Current Challenges, 2nd Edn. London: SAGE.

Times Higher Education (2020). Best Universities in the UK. Available online at: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/student/best-universities/best-universities-uk (accessed February 20, 2021).

UN Environment (2019). Higher and Further Education Institutions Across the Globe Declare Climate Emergency. Available online at: https://www.sdgaccord.org/files/eng_highered_pressrelease10072019.pdf (accessed January 26, 2021).

Universities UK (n.d.) Higher Education in Numbers. Available online at: https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/facts-and-stats/Pages/higher-education-data.aspx(accessed January 26 2021).

University of Brighton (2020). University Declares Climate Emergency. Available online at: https://www.brighton.ac.uk/news/2020/university-declares-climate-emergency (accessed January 26, 2021).

University of Bristol (2019). University of Bristol Declares a Climate Emergency. Available online at: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/biology/news/2019/university-of-bristol-declares-a-climate-emergency.html (accessed January 26, 2021).

University of Exeter (2019a). University Declares an Environment and Climate Emergency. Available online at: https://www.exeter.ac.uk/news/featurednews/title_717135_en.html (accessed January 26, 2021).

University of Exeter (2019b). Environment and Climate Emergency Working Group White Paper. UK: University of Exeter.

University of Glasgow (2019). UofG Declares a Climate Emergency. Available online at: https://www.gla.ac.uk/news/archiveofnews/2019/may/headline_646140_en.html (accessed January 28, 2021).

University of Manchester (2019). University Supports Government's Climate Declaration. Available online at: https://www.manchester.ac.uk/discover/news/university-supports-governments-climate-declaration (accessed January 26, 2021).

University of Plymouth (2019). University of Plymouth Declares a Climate Emergency. Available online at: https://www.plymouth.ac.uk/news/university-of-plymouth-declares-a-climate-emergency (accessed January 26, 2021).

University of Sussex (2019). University of Sussex Declares Climate Emergency. Available online at: http://www.sussex.ac.uk/broadcast/read/49187 (accessed January 28, 2021).

University of Warwick (2019). University of Warwick Climate Emergency Declaration. Available online at: https://warwick.ac.uk/newsandevents/pressreleases/university_of_warwick_climate_emergency_declaration1/ (accessed January 26, 2021).

University of Winchester (2019). University of Winchester Declares Climate Emergency. Available online at: https://www.winchester.ac.uk/news-and-events/press-centre/media-articles/university-of-winchester-declares-climate-emergency.php (accessed January 26, 2021).

Walker, A. (2019). Goldsmiths Bans Beef From University Cafes to Tackle Climate Crisis. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/aug/12/goldsmiths-bans-beef-from-university-cafes-to-tackle-climate-crisis (accessed January 26, 2021).

Keywords: climate emergency, climate emergency declaration, universities, higher education, climate change, sustainability

Citation: Latter B and Capstick S (2021) Climate Emergency: UK Universities' Declarations and Their Role in Responding to Climate Change. Front. Sustain. 2:660596. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2021.660596

Received: 29 January 2021; Accepted: 16 April 2021;

Published: 19 May 2021.

Edited by:

Victoria Hurth, University of Cambridge, United KingdomReviewed by:

Francesco Caputo, University of Naples Federico II, ItalyPekka Juhani Peura, University of Vaasa, Finland

Copyright © 2021 Latter and Capstick. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Briony Latter, bGF0dGVyYmlAY2FyZGlmZi5hYy51aw==

Briony Latter

Briony Latter Stuart Capstick

Stuart Capstick