- Faculty of Economics, Management and Accountancy, University of Malta, Msida, Malta

This study examines how human resources in the Maltese Public Service adopt new work practices in response to COVID-19 public health measures during the first wave of the pandemic. We analyze the data we collected through seven focus group discussions and ten in-depth interviews with Public Service employees and managers in a diversity of ministries and roles. Our study reveals that Public Service policies promoting remote working relied exclusively on the service's IT infrastructure. However, the ability to respond to customer needs effectively in a time of surging demand relied entirely on effective employees' access to responsive and efficient ICT support as well as employees' prior experience with remote work modes and their predisposition to change to remote working. Adopting remote working modes uncovered inherent weaknesses in the Public Service IT infrastructure that put additional strain on the Government's centralized IT support function, especially when Public Service employees adopted tools not supported by the centralized IT support. In circumstances where centralized IT support was ineffective, Public Service employees relied on their own knowledge resources which they informally shared in groups of practice or employed operant resources (or tacit knowledge) to achieve service level objectives. These observations suggest that in times when organizations respond to immediate and unprecedented change, human resources seek to adapt by relying on tacit knowledge that is shared among people in known (often informal) groups of people with a common interest or role.

Introduction

On March 7th 2020, Malta detected the first COVID-19 case, bringing the entire country to a new reality where social, political, legal, and economic processes had to be questioned and put to an unprecedented test. The Maltese public sector is considered as one of the most important players in the Maltese political and economic scenarios (Grixti, 2019), and was perhaps one of the first major players in the country to change the modus operandi by adopting new operating procedures in compliance with Public Health recommendations that were emerging from time to time in response to the pandemic's trends (Cassar and Azzopardi, 2019).

This response meant that a significant proportion of the Public Service workforce was assigned to work remotely, away from centralized offices as a way to execute precautionary measures intended to control the spread of COVID-19 pandemic.

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the outbreak of a pandemic on 12th March 2020. In June 2020, WHO reported over 8 million confirmed cases and over 435,000 deaths. By December 2020, the pandemic claimed over 71.5 million confirmed cases and over 1.6 million victims. In just a few weeks, the pandemic spread in almost all countries around the world creating huge damage to the global socio-economic infrastructure and forcing people to change their working styles, habits, and employment prospects. Most countries have been forced into full or partial lockdowns and gradually sought very cautious re-openings to safeguard their economies and employment prospects for their citizens. COVID-19 has indeed been a case illustrating the fragility of a number of businesses and business sectors (Amankwah-Amoah et al., in press), such as hospitality and aviation. While the literature on business continuity affirms for back-up plans and protocols to weather catastrophes, experience has now shown that this has not always been the case, with some major firms having to file for bankruptcy and laying- off thousands of workers. The essence of business continuity aimed at value presentation, continuity of operations and recovery advantage (Herbane et al., 2004) were far from ideal indicating the lack of preparedness of many organizations in such instances (e.g., Rezaei Soufi et al., 2019). This is therefore the context in which our study takes place, and specifically assesses a number of forces in favor or against the easiness and rapidity to adapt to such major changes which in many ways has been unprecedented to the generations currently alive.

In our investigation, we therefore assume the view that the pandemic represents a trigger of a major change. In view of this, we position our study within the context of major change. We postulate that COVID-19 has forced us to reconsider and to redefine the whole reality of work and work practices. Johns (2018) remarks emphatically the lack of contextual appreciation in many studies related to organizational sciences. An appreciation of the context helps us to capture factors that are either new or unexpected. Context is also a boundary feature of theory and theory is best placed within a set of defined parameters conditioned by context. For example, Bacharach (1989) remarks about the need to evaluate the utility of theory within its defined time and space. The current context has placed a huge level of stress on businesses, employers, and employees alike. Certain aspects that are critical to the survival of this business relationship have been threatened and the COVID-19 situation has pushed for many major contextual and employment changes. These range from the way teams and employees have had to maintain contact, the shift to virtual meetings, the challenging and troubling times to maintain employment and deal effectively with future concerns to issues arising from IT security as businesses moved to more telework practices and safeguard their protection to maintaining ongoing relationships with customers. These changes were massive and quick. As a consequence of these changes, the magnitude of disruption has put into question how we restore the fit between people and organizations and hence push for the realignment of the proper resources to accommodate this re-fit. This therefore takes us to the issue of the need to re-adapt. In this turmoil, organizations are rediscovering their best way to operate and to find a means to ensure that employment relations are adequate enough to restore a degree of industrial “peace” and stability. This requires people to think again of the quality relationship they will have with their employer sparking arguments about new work arrangements and contingency employment.

COVID-19: A Major External Force Triggering Massive Change

The pandemic can be considered as an external major force of change on organizations akin to what Thompson and Hunt (1996) label as a gamma change. Gamma changes force people to redefine their organizational reality to the extent that it is no longer comparable with the previous state. In other words, for an organization to regain some degree of stability would require massive adjustments. Gamma changes require a complete transformation in one's cognitive beliefs. These beliefs may not be at par with existing values and systems may consequently be stressed until such beliefs are accepted into the new cognitive structures of organizational members (Thompson and Hunt, 1996). This is in line with explanations focused on change and implications that derive from changing dynamics inherent to the so-called psychological contract (e.g., Rousseau and Wade-Benzoni, 1994; Coyle-Shapiro and Conway, 2004), although previous studies have never foreseen a shock on the scale of COVID-19. COVID-19 has already caused immense uncertainty where organizations may need to downsize operations, lay-off staff, and require adaptive and proactive behaviors by employees to enable survival and adequate organizational functioning. From an employment relationship perspective, Rousseau (1995) refers to a process of “contract reframing” where employment exchange schemata that define the exchange in the employment relationship requires redefining. This can often also result in schema mismatches (Morrison and Robinson, 1997; Freese et al., 2011) and raises insecurity and serious doubts about the future (Morrison, 1994). Thus, we hypothesize that given that people's employment represents an exchange process and therefore fulfills each party's needs, the pandemic has drastically changed this such that one would expect significant damage to the employment relationship unless all parties re-adapt to new scenarios of working. In fact, adjusting one's interpretation of the employment deal under major change appears to go through a process of gradual re-interpretation brought about through perceived cycles of breach coupled with a momentary sense of cognitive dissonance (Saunders and Thornhill, 2006; Dulac et al., 2008).

The Major Challenge: Finding a Sense in the New Work Arrangement

In these contextual realities represented by COVID-19, one wonders about the way employees and employers need to retune themselves and find a purpose in such uncertain environments which also pose a high level of risk (e.g., Bidmead and Marshall, 2020). A study by Wang et al. (2021) reveals clearly the challenges employees meet (such as work-home interference, ineffective communication, procrastination, and loneliness) in executing effectively their work and provides insights on the importance of social support and self-discipline. Griffin et al. (2007) proposed the adaptive process of work roles and perception of “performance” in a work environment that presents uncertainty. In their analysis of emerging work roles they depart from the more formalized roles we typically know in more stable socio-economic conditions. The authors identify three in particular: The first, is termed as “proficiency,” which basically describes the prerequisites required to perform one's role effectively and efficiently. The proficiency dimension is adequate in stable structures and where clarity is not inhibited by issues of major change. The other two dimensions are “adaptivity,” and “proactivity.” The former describes the extent to which individuals adapt easily to changes while the latter describes the extent an individual will engage in self-directed action to anticipate or initiate change in the work system or work roles. These two dimensions are critical whenever a work context involves uncertainty and some aspects of work roles that cannot be formalized or their formalization has been rendered impossible due to the major changes. These challenges become more acute when they also involve rapid changes that require the other workers, colleagues, employers, and indeed the whole organization to reframe itself and accommodate a new arrangement. This latter part of the argument is crucial because adaptability only depends partially on the individuals and rests mainly in the adaptivity of the whole multi-layer business ecosystem. Amankwah-Amoah et al. (in press) provide an analysis and closer look at the system shock in societies, business, and hence employees due to COVID-19. They posit that COVID-19 has had the effect of misaligning a number of relevant organizational factors and this has triggered an internal chain of events that have often been disruptive as organizations and their agents and employees struggled to reframe their new reality (Rousseau, 1995). These misalignments have been strong signals to avoid the assumptions stemming from long regulatory continuity and/or predictions (Amankwah-Amoah et al., in press). Schuster et al. (2020) further suggest that constant review of the impact of the remote modes of work among public officers requires constant monitoring as a means to identify and resolve arising problems in real time and thereby ensuring the constant engagement of public officers.

The Maltese Public Service

The context for our study is specifically the Maltese Public Service which currently employs circa 30,000 employees organized in eighteen ministries. As at July 2020, the Public Service employed about 1,250 senior civil servants (from principal permanent secretary to assistant director level). Most of the Maltese Public Service tradition is a result of British rule that lasted from 1800 to 1979. Malta became an independent state in 1964 and a republic in 1974. Like most Public Services, the Maltese Public Service went through a number of reforms. These reforms have not only been strategic but also structural and operational. Like most reforms, they have not always been plain sailing and given the size of Malta they have often conflicted with the motives and agenda of the higher political class giving rise to certain dysfunctionalities (Pirotta, 1997). This is partly due to the need for sustained political backing and partly because of competing structures that struggle for their raison d'etre (Cassar and Bezzina, 2005). The Maltese Public Service is indeed typically characterized by a high sense of legitimate authority (Cassar and Bezzina, 2005). With Malta's accession into the EU in 2004, the Maltese Public Service has had to constantly transform itself to meet the needs of Malta's economic growth and also to align itself to required obligations of the EU. Indeed, Cassar and Azzopardi (2019) note that there has been a shift from an administrative-centric institution to one that is more people-centric with a drive to become more performance-driven and accountable. Such a shift actually presents a dual tension instance: on the one hand, public officers are expected to abide to specific and strict codes of practice while on the other are required to become agile in their operations and ensure they can achieve high level organizational goals that reflect efficiency and effectiveness. These may look incompatible to each other and sometimes contradictory. This scenario thus presents the Maltese Public Service in a state of flux oscillating between a purely administrative machine but at the same time pushing ahead to re-engineer a more performance driven climate based on the efforts of its people. In doing so, employees have to constantly adapt while redefining their deal with their employer.

Scope of This Study

This study examines how human resources in the Maltese Public Service adopt new work practices in response to COVID-19 public health measures during the first wave of the pandemic. We attempt to answer the following research questions:

RQ1: What are the proficiencies and opportunities that helped the Maltese Public Service meet up the challenges presented by remote working in the COVID-19 pandemic?

RQ2: What are the limitations and challenges that hampered the Maltese Public Service from achieving better efficiency, economy, and effectiveness during the COVID-19 pandemic?

The findings from this study should better guide Public Service policy makers in their quest to make remote working facilities more comfortably accessible to employees and in doing so be more resilient in handling change. We borrow from positive psychology to conceptualize resilience as a dynamic process of successful adaptation (Pan and Chan, 2007). In addition, the study also presents lessons that will direct decision makers in strengthening such new work practices in the long term even when the pandemic is over.

We were initially inspired by a SWOT analysis approach but acknowledge that this tool fits better when analyzing organizations rather than their members. It is for this reason that we look at groups of human resources and individuals by looking at proficiencies rather than strengths, limitations rather than weaknesses and challenges as opposed to threats in our approach.

Method

Considering the nature of the study's research questions, phenomenological and ethnographic approaches seemed feasible and capable of providing a robust and rigorous approach to answer the research questions (Saunders et al., 2019). Ethnographic studies enable researchers to describe and interpret a culture-sharing group (Creswell, 2012)—a factor that we considered to be insufficient to address the prerequisites of this study's objectives. By contrast, phenomenological approaches offer a deeper understanding about the essence of the experiences as described by the actors involved in the phenomenon, justifying the application of this approach in this study. Indeed, in adopting this approach, we set out on a study that involved three distinct phases of data collection.

The first phase involved six focus group discussions with participants from a diversity of grades, salary scales and roles and who worked remotely in a selection of 12 departments within six ministries. We selected participants in these focus group discussions from a diversity of grades and salary scales and roles. A further focus group discussion was organized with senior managers. Each of the focus groups consisted of nine participants (on average). The group discussions lasted around 2 h and were moderated by trained researchers employed in the project. In our focus group discussions with a diversity of employees, we asked participants to relate to general experiences when adopting remote work in response to public health recommendations in the context of the pandemic, aspects relating to their work-life balance, social relationships, motivation, and performance as well as health and well-being. In addition to these questions, in our focus group discussion with senior managers, we asked our participants to relate to aspects of people management and work relationships. A more detailed outline of the questions asked during our focus group discussions is presented out in the Appendix.

The second phase of the project was intended to corroborate the observations in the earlier focus group discussions. During this phase we conducted ten structured interviews with individuals employed as Chief Information Officers within the different ministries. Three of these interviews were held face-to-face while the remaining seven were conducted online either to comply with public health requirements imposed during the timing of the study, or to respond to logistical challenges prevailing at the time of the study. These participants were asked about:

• the effect of remote working requirements on their role,

• tools employed to support collaboration,

• deployment of emerging technologies,

• codes of ethics for the use of tools that support remote working,

• experienced change in employees' demand and use of digital technologies during the pandemic,

• challenges emerging from systems' integration influencing remote working,

• challenges that justify prioritization for Public Service investment,

• emerging remote working threats and opportunities, and

• most successful innovative initiatives that participants rolled out during the pandemic and associated remote working.

A third and final phase was intended to complete the desired level of robustness of the study through data triangulation. To address this requirement, we reviewed the data that the Public Service had previously collected from several customer-oriented channels like customer complaints, comments and suggestions received by the Government's business promoting portal, interviews conducted by officials within the Ministry for Education and Employment with parents (or other recorded feedback at the same ministry) as well as the customer feedback channels operated by the different ministries. This data spanned several weeks after the outburst of COVID-19 in Malta and during the implementation of social distancing and remote working measures within the Public Service in Malta.

All interviews were recorded and subsequently transcribed, whereas focus group discussion recordings were annotated into summarizing scripts with key material transcribed verbatim. The resulting transcripts as well as all the data collated during the third phase of the data collection process were uploaded as a project on NVivo™ 12. Analysis of transcripts and annotations required four cycles of coding. The first cycle involved an auto-coding approach where NVivo™ software categorized text into nodes reflecting the questions asked to study participants. The second cycle of coding involved the coding of text on two sets of template nodes. The first set related to four large areas concerning proficiencies, opportunities, limitations and challenges, whereas the second set related to seven large themes about organizations' strategic factors: strategy, structure, style, systems, staff, skills, and shared values, inspired by McKinsey's 7S Framework (Peters and Waterman, 1982). A third stage of coding adopted an open coding approach of the McKinsey's 7S Framework nodes into themes through process and action perspective (Saldaña, 2015). A fourth and final cycle of coding looked at the level of analysis of the observations (separating data into three key nodes: individual, group, and organizational) as well as any relevant tools that participants referred to.

Throughout the entire process of coding, we generated a total of 58 initial nodes that were eventually reduced to 31 child nodes, aggregated into four key nodes. We report the observations emerging from this coding process in the following section of this chapter.

Findings

We relate our findings to four key themes. We start by discussing the proficiencies that helped the Public Service meet up the challenges presented by remote working as a new mode of operations. We then discuss the limitations that hampered the Public Service from achieving even better efficiency, economy and effectiveness. We see these challenges in the light of externalities that challenged the entire change process, along with the openings that COVID-19 and concurrent external factors may have presented an even better chance of achieving optimized value for money.

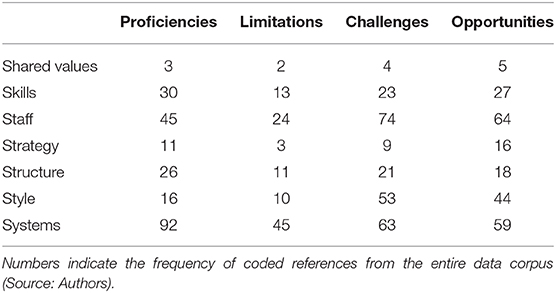

Our findings suggest that our participants see proficiencies and limitations emerging primarily from the systems adopted by the Public Service and the Public Service employees (see Table 1). By contrast, study participants see the service's key challenges and opportunities emerging from the Public Service employees, systems in use and the style of management.

Table 1. Summary of key themes' coding emerging from the study: proficiencies, limitations, challenges, and opportunities across the 7S framework themes.

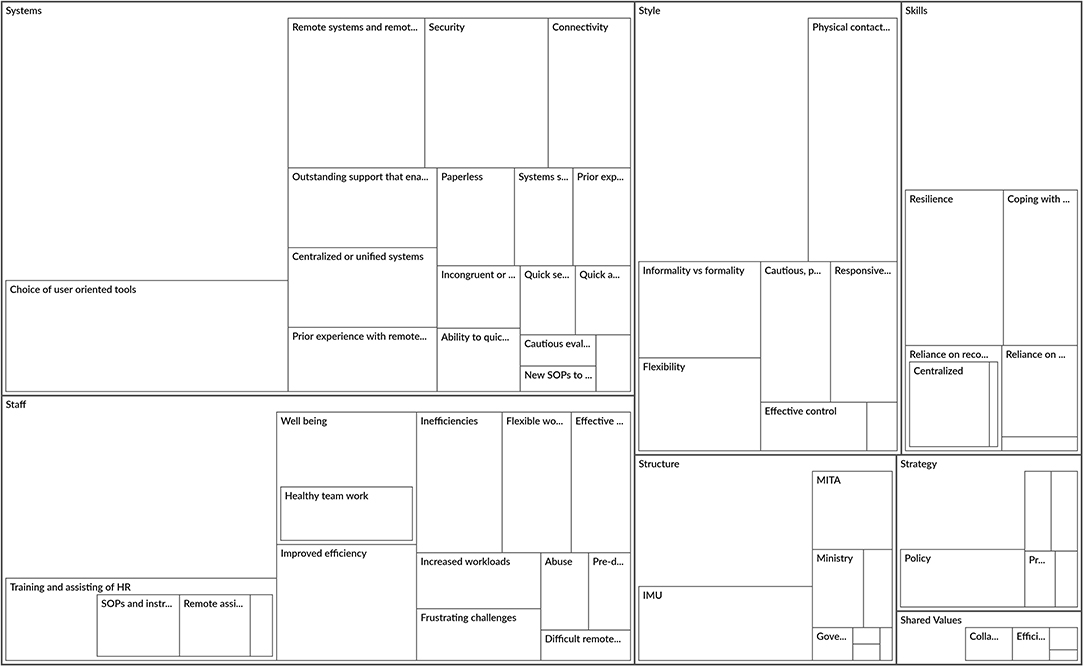

A graphic depiction of the structure of our coding with respect to the 7S framework codes is set out in Figure 1. The following paragraphs set out a more detailed discussion of these findings.

Figure 1. Graphic summary of the key themes emerging from the study, with coding consistent with 7S framework (Source: Authors).

Proficiencies

Our observations suggest that Malta's Public Service relied entirely on capabilities stemming from the Service's systems, staff, and their skills. In some instances, we also noted that the service's organizational structure proved to be an internal resource that helped the Public Service embrace change toward remote working mode effectively.

Starting with the Public Service's systems, we observed how the ICT infrastructure proved to be instrumental for most human resources to adopt remote working effectively and adapt to the new environmental circumstances while still coping with increased customer expectations and testing resource requirements. Remarkably, Public Service officials and employees had access to a wide selection of user-oriented tools ranging from portable hardware to a diversity of third-party software applications all intended to ensure continued (if not augment) service productivity. In a small proportion of cases, we noted how the Public Service could afford to acquire assets or applications in a short while, while in other cases, the modular nature of IT support systems (such as VPN accounts and licenses) helped users move seamlessly to remote working thanks for the immediate provision of VPN tokens.

From a staff and skills' perspective, earlier experience with the above tools as well as with remote working also helped Public Service human resources move to remote working swiftly, encouraging relatively inexperienced peers and colleagues to embrace such a change. Earlier experience, indeed, fueled the diffusion of a predisposition among employees who had never experienced remote work before COVID-19 pandemic struck the Maltese islands. In some cases, human resources in senior and middle positions found prolonged remote work easier to adopt having experienced the enabling assets like specific software applications, VPN access as well as other assets. This experience helped such employees transmit a word of mouth (if not project an “image”) about change as a relatively easy challenge, with possible and feasible short-term “gains”.

From a structure perspective, the virtually streamlined transition to remote working mode was possible as workers and management relied on the access to a responsive and efficient support provided by the Malta IT Agency (MITA) that organizes and manages all of the Maltese Public Service IT strategies and operations, and thanks to the different ministries' IT Management Units (IMU's) that coordinate their efforts with the MITA. MITA and IMUs are responsible for all systems and asset acquisitions, administration and the effective training of Public Service HR for the use of such systems and assets, offering several support approaches, such as online or telephone support to users. Expertise and support were also available to human resources (transiting from traditional to remote working modes) through pockets of expertise or knowledge located within known and trusted colleagues.

Overall, our observations suggest that overall, while coping effectively with a familiar yet potentially not optimal work environment, participants reported reduced levels of stress as a result of lesser commuting, less distractions and flexible hours of work as a positive outcome, helping our participants enjoy a healthier lifestyle, improved well-being and resulting higher levels of productivity as well as service delivery. These outcomes were corroborated by comments we observed in feedback from customers who pointed at enhanced service delivery as service channels proliferated online from previously plain face-to-face or phone, alongside minimal disruption in service delivery.

Limitations

Three key, highly interlinked limitations impacted on the relatively smooth transition to remote working among Public Service employees.

First, from a skills perspective, some inherent limitations in the software applications (that were made available to staff) meant that Public Service human resources faced an additional level of learning before they could fully exploit the capabilities of the software in their new mode of work. In some instances, software tools were unable to offer a complete solution for a seamless remote delivery of services, especially when Public Service employees used own assets for working remotely, such as own mobile telephone devices, own internet connectivity, if not own computer hardware. This meant that some software solutions could not be exploited to their full capabilities as employees enjoyed interrupted connectivity, low bandwidths, lack of coverage as well as other connectivity and security limitations.

Second, from a structure perspective, as large numbers of staff turned to new off-the-shelf software solutions, requests for assistance and support inundated the central support functions that MITA or the IMUs managed, rendering the available assistance unable to cope with new levels of demand, while concurrently rendering the learning process more than justifiably demanding. In some instances when remote work meant support would be unavailable within a reasonable time, users would opt for other available, third-party solutions, that presented their own challenges relating to connectivity, security, and compatibility (with other Public Service assets and systems as well as customers' systems). Alternatively, a minority of employees who were lesser ICT conversant would not get support from MITA or IMUs in time, would seek help from colleagues who would have become recognized pockets of excellence in their use of specific software and system solutions. Such reliance would, in turn, impair the productivity of such better skilled employees.

Third, from a staff perspective, working remotely meant that employees had to endure levels of isolation (actual or perceived). Although the majority of workers enjoyed reliable telephone or online connectivity with colleagues, the lack of physical presence of coworkers meant that individuals often felt a prevailing sense of seclusion and associated reduced levels of motivation. This isolation also exposed managers' limitations in their ability to monitor and motivate employees using online or remote methods. That most employees felt that working remotely meant additional work demands and loads further amplified the importance of concern emerging from isolation and seclusion that accompanied the new modus operandi, impacting on employees' work-life balance and overall felt well-being.

Challenges

Adopting remote working revealed three previously concealed challenges that threatened the attainment of the full effectiveness of operations.

First, the assets and software that staff had available in their remote locations often featured security levels that fell short of the Public Service standards, potentially exposing sensitive data and information to third parties like family workers' family members or acquaintances, if not other individuals considering the typical security protocols adopted by third party internet service providers. Although in most cases, MITA and IMUs mitigated this risk through the affording of VPN tokens, the likelihood of unauthorized access remained high with respect to printed matter or electronic data that would be exposed to family members or friends during work at home.

Second, working from remote locations meant that Public Service employees were unable to draw time boundaries between work and social life. Being unable to separate these activities, a proportion of Public Service employees saw their work-life balance shifting with resultant deterioration of their well-being and associated, resultant productivity at work. Besides, the added flexibility meant that workers can avail themselves from work during office hours without the requisite permissions (or indeed control) from supervisory or managerial staff, resulting in intermittent and unrestrained absenteeism in some cases.

Third, the very nature of remote work meant that client facing workers could not achieve full effectiveness in dealing with customers reaching the Public Service either due to intermittent connectivity or due to the inability of a segment of customers who would not be completely conversant with online service approaches. This threat is further compounded by the fact that certain segments of society remain not well-served by internet connectivity owing to geographic constraints, as well as the generally elevating social expectations among Public Service audiences.

Opportunities

Despite the challenges and inherent weaknesses of the Public Service, the thrusting of a workforce into remote work unveiled five opportunities for the Public Service to help its customers co-created augmented levels of value.

First, from a systems perspective, an increasingly digital society means that the Public Service can widen its audiences, offering more services online whilst opting out of face-to-face or traditional forms of service delivery. Our findings suggest that there are still huge openings for paper-based services to be transformed into a digital mode of rendition, especially in cases where services involve a strong element of knowledge-orientation (like consulting) or certification. On a similar note, the use of existent technology can also help the Public Service offer highly personalized delivery of specific services thanks to the use of AI or machine learning—technologies that are a growing element in mainstream online service design. The reliance on digital modes of service delivery also helps the Public Service to stay in a path of constant improvement as processes become increasingly traceable and transparent, open for relatively easier-to-implement business process re-engineering with resulting advances in economy, efficiency, and effectiveness. This transformation is likely to address existing challenges emerging from incompatibilities between systems and platforms that are still unique to specific functions/ministries.

Second, that society is increasingly dependent on an efficient and effective IT infrastructure is a notion that drives the telecom industry to constantly upgrade the levels of services provided to its markets. This trend is an additional contention that helps the Public Service rely better on remote locations from where employees can deliver services—whether at home or at other locations that are considered fit for purpose. With this objective in mind, a further motive exists for the Public Service to continue in its path of rendering services increasingly independent from the use of paper or the requirement for audiences to resort to physical, centralized locations that often present logistical challenges emerging from traffic conditions, parking and time consumption. Nonetheless, these forces mean that the Public Service needs to thread carefully in remaining entirely compliant with existing legal requirements, such as data protection, security, and privacy.

Third, as Malta progresses further in converting itself as a digital society, the Maltese Public Service becomes increasingly composed of digital savvy workers who offer further opportunities for service digitalization and online service delivery. This opportunity is likely to see, in the longer term, the vanishing of workers who are either incapable or resist work of a digital nature, helping the entire Public Service workforce adopt digital work more effectively. Nonetheless, the complete optimization of online service delivery that fully exploits the capabilities of such a workforce relies on continued improvements on the tools and services made available to Public Service employees in working remotely. For instance, the development of a unified telephony system through which employees can be reached seamlessly on their smartphone is one such tool—and—opportunity.

Fourth, as social expectations among Public Service employees rise, so do workers' expectations from their employer. In our case, we observe how Public Service employees see remote working as an opportunity for easily improved productivities (as a result of reduced commuting times and the disappearance of unproductive chores, such as waiting for meeting commencements) as well as improved presence at home (with associated improved participation in family or other social commitments). Public Service employees consider these two opportunities as a precursor for improved motivation, while senior Public Service officials see these opportunities as a forerunner of long-term reduction in costs and emissions as exemplified by reduced energy use, reduced commuting and reduced work space requirements.

Finally, the adoption of remote work as a key form of service delivery meant that the Public Service can augment the level of value co-creation with the relevant audiences. Our findings suggest how Public Service employees could better (and more quickly) respond to emerging needs as individuals availed of more time to core tasks and spent less time on distractions and unproductive chores. A more responsive Public Service is a key consideration in the eyes of increasingly demanding and expecting external stakeholders.

Discussion

Having reported our findings from our field data and analysis, we now turn to discuss the implications of these observations by relating to earlier theoretical discourse as well as the implications on the Maltese Public Service.

Our study revealed that the implementation of remote working can lead to long term benefits for the Public Service in the form of augmented reputation and cost-effectiveness. Indeed, as more employees move to work from remote locations, the Maltese Public Service may well profit from reduced fixed costs (such as rent of premises, utility) as well as be more environmentally oriented as a result of reduced reliance on transportation and commuting. This may indeed serve as a mortar to fulfill the often-conflicting position of the Maltese Public Service between complying to administrative procedures and simultaneously achieving performance related targets (Cassar and Azzopardi, 2019). Our observations also suggest that remote working leads to reduced stress, increased employee flexibility, and improved employee effectiveness in most cases. Employee flexibility in turn augments employee well-being with obvious implications on employee motivation and delivery of excellence. This is consistent with the re-framing process highlighted by Rousseau (1995) which I the case of the Maltese Public Service has been surprisingly well-managed even though the changes involved have been major; this could be possibly explained by the fact that both parties saw additional benefits to tuning into this new arrangement.

Nonetheless, we also note that the Public Service needs to address specific challenges by implementing strategies to improve the level of service delivery sustainably. There are two areas that the Public Service needs to address.

First, in ensuring that people deliver an optimized level of effectiveness, the Public Service needs to adopt measures that ensure that remote working is adopted at a widespread level, leading to a complete culture shift within the Public Service, leading to associated benefits like improved motivation levels and prolonged staff retention. We see these measures relating entirely to how Public Service employees are managed, requiring the senior and middle managers to adopt tools that enhance the motivation of the Public Service workforce to further encourage the adoption of remote work, as well as continue to perform to deliver excellence from remote locations. This is consistent with the notion of supporting employment exchange schemata fit the new work practices (Morrison and Robinson, 1997; Freese et al., 2011). Examples of such tools may range from monetary incentives to recognition of performance and initiative through awards. Remuneration levels and structures may also need to be reviewed and improved, intended to ensure that employees' efforts are rewarded equitably, especially in cases where employees sacrifice their work-life balance to cope with additional levels of responsibilities that remote work presents to them. Such as would be the case when ICT savvy employees help colleagues adopt new tools to work effectively, remotely. Lesser skilled workers' reduced reliance on ICT savvy coworkers can also be amplified if additional training and coaching can be directed toward the former, especially when such employees face customers and are required to deal with online documentation. This will certainly lead to a redefined employment relationship through rebuilding trust (Saunders and Thornhill, 2006) and needs to be adequately steered to ensure long term stability (Dulac et al., 2008).

Additional training and coaching should be directed toward employees who find it challenging to draw strict boundaries between work and life. Our findings suggest that very often workers in remote locations (especially at home) find it difficult to separate social life from work. Coaching and training by experts can help ensure that such workers can enjoy an equitable work-life balance. In monitoring and managing the attainment of such objectives, the Public Service needs to conduct an exercise that measures and evaluates how individuals working remotely can handle a reasonable workload without being subjected to excessive demands, especially over a prolonged period of time. Prolonged handling of overwhelming demands is known to lead to unjustified levels of stress that in turn reduces the levels of employee well-being and associated motivation and engagement. Inevitably this will also push for role re-formalization (Griffin et al., 2007). Further, as service delivery is subject to the effects of the uniqueness of individual employees, we see the development, publication and distribution of standard operating procedures that guide employees to adopt ethical, optimized behaviors in dealing with colleagues as well as third parties as critical for ensuring the delivery of high level, seamless quality of service. These operating procedures would need to deal with employees' handling of third parties through online written communications, online/virtual meetings, phone conversations as well as the management of surroundings in remote work locations.

Second, in safeguarding the sustained effectiveness of remote working and the successful implementation of the above people-oriented measures, the Public Service needs to implement additional measures that strengthen the next strategic asset: the ICT infrastructure and associated services. Here, additional investment is required to ensure that Public Service employees can access ICT tools seamlessly irrespective of location. Our observations suggest that MITA and IMUs need to direct investment to help workers enjoy uninterrupted, reliable, and secure connectivity, potentially involving a partnering approach with local 4G service providers. Equally, investment in new software applications and hardware needs to continue albeit focused on those solutions that are both user-oriented as well as capable to seamlessly integrate with existing applications and processes. Similar investment needs to be directed to ensure that employees in remote locations are accessible and can be reached seamlessly without relying on personal phone services.

Additional investment needs to be directed toward the introduction of automated systems that help managers monitor and manage better employee performance. Systems that help employees register and record active service and throughput are relevant examples. Equally important is the notion that investments need to be devoted to the provision of hot desk services particularly to those employees who enjoy less-than-optimal conditions at locations where they have, so far, adopted remote work. Such locations do not require huge footprints, and would help teams meet up periodically and keep a face-to-face contact especially when working on demanding projects.

With these investments brought to the fore, the role of MITA and IMUs becomes paramount in coordinating an acute evaluation of work processes as well as user requirements in view of the new work realities. However, unabated investment without the re-engineering of existing business processes is likely to not result in optimized value-for-money unless MITA and IMUs evaluate the current service processes for potential opportunities for service simplification and augment value co-creation especially where hard copy documentation is still a requirement. Equally, the supporting role of MITA and IMUs is an additional contention as Public Service employees working in remote locations remain dependent on human support for their adoption of new tools (if not processes) in their delivery of services to stakeholders. Formalizing the common assistance approaches that MITA and IMUs provide to the Public Service workforce ensures that reliance on tacit knowledge (held in pockets of excellence) is minimized. The use of AI or machine learning powered solutions may also help in this direction.

A word of caution is warranted: such investments require well-defined strategic interventions to ensure that continuity is maintained and that technological investment does not upset the long-term benefits with short term interventions (Herbane et al., 2004; Amankwah-Amoah et al., in press).

Whereas our study exposed the realities of resilience of the Maltese Public Service in responding to the demands of a pandemic, we note that our study carries its own limitations that open opportunities for future research on resilience in public sector management. We reflect on three key such opportunities.

First, our study offers a depiction of resilience that relies on individuals' recollections and observations over a short period of time. A question that emerges at this stage is how do individuals and groups respond to public health requirements over the entire duration of the pandemic. How do such individuals and groups in public service learn to cope and prevail in prolonged times of pressure as exemplified by multiple, successive waves of a pandemic? How will motivation and productivity evolve over such prolonged periods of time?

Second, an associated question that emerges from the above contention is how do individuals cope with isolation over a prolonged period of time? Our study revealed several challenges that individuals face when working in a virtually isolated context, that emerge only after working from remote locations over a period of a few weeks. Prolonged remote working relying on technology and virtual contact with peers may present a unique set of challenges that may well push so far unnoticed proficiencies and limitations at individual and group levels to the fore. COVID-19 pandemic, at the time of writing this chapter, is far from over and the entire world expects further waves of contagion as the virus continues to mutate and emerge as new variants.

Third, our study relates specifically to the Maltese Public Service—a sector that involves around 30,000 individuals located in one of the smallest nation states in the European Union. How do different public services respond to the same pandemic? Different countries employ different strategies and associated levels of investment in ICT and people development, with assumed impact on employees' learning and capabilities to cope with remote working realities. Differences between countries are bound to emerge more visibly as countries exhibit unique political, social, economic, educational, technological and legal realities. Nonetheless, the common mechanisms and structures that help specific public sectors in these countries prevail during the times of a pandemic remain unknown. Answering this question requires a multi-country approach that investigates how different public services cope and respond to the challenges emerging from the pandemic.

Concluding Comments

Our study revealed that Malta's Public Service is resilient and capable of handling rapid, demanding and unprecedented change as Public Service employees learn and embrace new work methods. Our observations emerge from a series of interviews, focus-group discussions and customer feedback conducted during the very first months after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in Malta.

For public service managers, our findings suggest that public service strategies need to address four important areas. First, people management and resourcefulness call for governments to not only revise remuneration structures that can ensure equitable rewards for employees' efforts, especially in times of crisis and change. Equally, governments need to evaluate employee work loads and demands, intent on avoiding overwhelming challenges that may well jeopardize employee well-being. Training employees to address any deficiencies like a lack of ICT skills, inability to manage work-life balance or managing problematic workers may well help public service attain new levels of efficiency and effectiveness. On managing problematic workers, systems that help managers better monitor employee performance may prove to be an important requirement. Nonetheless, addressing any lack of ICT skills may well indicate a need for governmental agencies like MITA to source or develop more user-friendly ICT applications that may well help employees become more engaged with their remote work and co-creating more value with colleagues and customers alike. Further, governments may well consider and introduce new tools to enhance employee motivation and performance while encouraging the adoption of remote working across the entire public service workforce.

Second, governance and standards are a further contention for public service managers and employees alike. This area requires the government to work on developing a common code of ethical behavior for employees to adopt when dealing with colleagues and customers online, applicable to all written and verbal communication, particularly in the context of remote work locations. The introduction of hot desk locations (for instance, using available space in local council offices) may well help employees adopt such code of ethics more easily.

Third, agility is a competence that calls for continued investment in people and systems. In times of continued strain emerging from prolonged pandemic realities, the Public Service needs to address agility by further investing in reliable connectivity, seamless voice communications (like an online PABX system that connects all public service employees through their personal smartphones) as well as seamless access and sharing of electronic documentation/data.

Finally, sustainability is an area that over the past years has garnered traction in government policies and management approaches. Yet, the realities of remote working call for the prioritization of specific measures that address this matter. For instance, whereas the public service may well be encouraging workers to adopt remote and greener working practices, further measures need to be undertaken to reduce the dependence on printed matter. Similarly, the government needs to address more acute security issues emerging from the use of applications recently adopted by employees working remotely. Encouraging remote working across an entire workforce and measuring results in terms of numbers of employees who adopt such working practice, without assessing the feasibility of processes beforehand is likely to lead to additional pressures on managers and employees alike, spelling disaster rather than success. Ensuring that remote working remains a sustainable way of public service business also calls for strengthening the support provided by agencies like MITA or IMUs in ministries by investing in additional human resources, AI or chat bots that are powered by machine learning to ease the pressure on client facing employees. Most importantly, ensuring long term sustainability also means that public service employees need to move away from an overwhelming reliance on tacit knowledge. As an example, there is a need for a formalization of common assistance/support approaches that currently provided by agencies like MITA or IMUs in ministries. Formalization and documentation of such approaches may well help employees across the entire public service rely on their own resources for seamless service provision while using public service ICT assets, rather than putting strain on the limited resources that MITA and IMUs employ.

Although our study offers a deep insight into how a complex organization like the Maltese Public Service can change, we acknowledge that our research is limited plainly to the Maltese case—a case that is dominated by a unique set of political, social and cultural elements that shape the context in which our findings emerge. Equally important is the notion that whereas our study remains exploratory in nature, we acknowledge that change in response to COVID-19 within the Maltese Public Service continues, justifying a longitudinal approach in studying how complex organizations respond to rapid, disruptive change.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by FEMA FREC, University of Malta. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following senior Public Service officers Joyce Cassar, Charmaine Busato, Joseph Tedesco, and Joseph Bugeja for supporting the research team during this research project and for helping in the collection of the data.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsus.2021.644710/full#supplementary-material

References

Amankwah-Amoah, J., Khan, Z., and Wood, G. (in press). COVID-19 business failures: the paradoxes of experience, scale, scope for theory practice. Eur. Manage. J. 10.1016/j.emj.2020.09.002

Bacharach, S. B. (1989). Organizational theories: some criteria for evaluation. Acad. Manage. Rev. 14, 496–515.

Bidmead, E., and Marshall, A. (2020). Covid-19 and the ‘new normal': are remote video consultations here to stay? Br. Med. Bull. 135, 16–22. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldaa025

Cassar, J., and Azzopardi, M. (2019). “Public service and public sector (Part 1): working for the state,” in Malta and Its Human Resources. Management and Development Perspectives, eds G. Baldacchino, V. Cassar, and J. G. Azzopardi (Msida: Malta University Press), 363–390.

Cassar, V., and Bezzina, C. (2005). People must change before institutions can: a model addressing the challenge from administering to managing the Maltese public service. Public Admin. Dev. 25, 205–215. doi: 10.1002/pad.358

Coyle-Shapiro, J., and Conway, N. (2004). “The employment relationship through the lens of social exchange,” in The Employment Relationship: Examining Psychological and Contextual Perspectives, eds J. Coyle-Shapiro, L. M. Shore, M. S. Taylor, and L. E. Tetrick (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 5–28.

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 3rd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc.

Dulac, T., Coyle-Shapiro, J. A. M., Henderson, D. J., and Wayne, S. J. (2008). Not all responses to breach are the same: the interconnection of social exchange and psychological contract processes in organizations. Acad. Manage. J. 51, 1079–1098. doi: 10.5465/AMJ.2008.35732596

Freese, C., Schalk, R., and Croon, M. (2011). The impact of organizational changes on psychological contracts. Personnel Rev. 40, 404–422. doi: 10.1108/00483481111133318

Griffin, M. A., Neal, A., and Parker, S. K. (2007). A new model of work role performance: positive behavior in uncertain and interdependent contexts. Acad. Manage. J. 50, 327–347. doi: 10.5465/amj.2007.24634438

Grixti, M. A. (2019). “Public service and public sector (part 2): pay negotiation,” in Malta and Its Human Resources. Management and Development Perspectives, eds G. Baldacchino, V. Cassar, and J. G. Azzopardi (Msida: Malta University Press), 391–410.

Herbane, B., Elliott, D., and Swartz, E. M. (2004). Business continuity management: time for a strategic role? Long Range Plan. 37:386. doi: 10.1016/j.lrp.2004.07.010

Johns, G. (2018). Advances in the treatment of context in organizational research. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 5, 21–46. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104406

Morrison, E. W. (1994). Role definitions and organizational citizenship behavior: the importance of the employee's perspective. Acad. Manage. J. 37, 1543–1567. doi: 10.5465/256798

Morrison, E. W., and Robinson, S. L. (1997). When employees feel betrayed: a model of how psychological contract violation develops. Acad. Manage. Rev. 22, 226–256. doi: 10.2307/259230

Pan, J.Y., and Chan, C. L.W. (2007). Resilience: a new research area in positive psychology. Psychologia 50, 164–175. doi: 10.2117/psysoc.2007.164

Peters, T. J., and Waterman, R. H. (1982). In Search of Excellence: Lessons From American's Best-Run Companies. New York, NY: Harper Row; Harper Collins.

Pirotta, G. A. (1997). Politics and public service reform in small states: Malta. Public Admin. Dev. 17, 197–207. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-162x(199702)17:1<197::aid-pad921>3.0.co;2-u

Rezaei Soufi, H., Torabi, S. A., and Sahebjamnia, N. (2019). Developing a novel quantitative framework for business continuity planning. Int. J. Prod. Res. 57, 779–800. doi: 10.1080/00207543.2018.1483586

Rousseau, D. (1995). Psychological Contracts in Organizations: Understanding Written and Unwritten Agreements. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc.

Rousseau, D. M., and Wade-Benzoni, K. A. (1994). Linking strategy and human resource practices: how employee and customer contracts are created. Hum. Resour. Manage. 33, 463–489. doi: 10.1002/hrm.3930330312

Saldaña, J. (2015). The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 3rd Edn. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publ. Ltd. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

Saunders, M. N. K., Lewis, P., and Thornhill, A. (2019). Research Methods for Business Students, 8th Edn. Harlow: Pearson.

Saunders, M. N. K., and Thornhill, A. (2006). Forced employment contract change and the psychological contract. Empl. Relat. 28, 449–467. doi: 10.1108/01425450610683654

Schuster, C., Weitzman, L., Mikkelsen, K.S., Meyer-Sahling, J., Bersch, K., Fukuyama, K., et al. (2020). Responding to COVID-19 through surveys of public servants. Public Admin. Rev. 80, 792–796.

Thompson, R. C., and Hunt, J. G. (1996). Inside the black box of Alpha, Beta, and Gamma change: using a cognitive-processing model to assess attitude structure. Acad. Manage. Rev. 21, 655–690. doi: 10.5465/amr.1996.9702100311

Keywords: public service, remote working, adaptation, online, Malta, human resources, COVID-19

Citation: Bezzina F, Cassar V, Marmara V and Said E (2021) Surviving the Pandemic: Remote Working in the Maltese Public Service During the Covid-19 Outbreak. Front. Sustain. 2:644710. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2021.644710

Received: 21 December 2020; Accepted: 22 February 2021;

Published: 22 March 2021.

Edited by:

Primiano Di Nauta, University of Foggia, ItalyReviewed by:

Francesca Iandolo, Sapienza University of Rome, ItalyNunzio Casalino, Università degli Studi Guglielmo Marconi, Italy

Copyright © 2021 Bezzina, Cassar, Marmara and Said. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Frank Bezzina, ZnJhbmsuYmV6emluYUB1bS5lZHUubXQ=

Frank Bezzina

Frank Bezzina Vincent Cassar

Vincent Cassar Vincent Marmara

Vincent Marmara Emanuel Said

Emanuel Said