- Department of Urban Studies, Collaborative Future Making (CFM), Center for Worklife Evaluation Studies (CTA), Malmö University, Malmö, Sweden

The Covid-19 pandemic pushes organizations to innovate, adapt, and be responsive to new conditions. These demands are exacerbated as organizations respond to the triple sustainability challenge of social and environmental issues alongside economic recovery. These combined factors highlight the need for an inclusive definition of organizational resilience, the increased agility to adapt, learn, and transform to rapidly shifting external and internal conditions. This paper explores a gendered perspective of organizational resilience and the implications for degendering the concept to incorporate masculine and feminine constructs equally valuable to the theory and practices of organizational resilience during times of crisis. Viewing the organizational demands of crisis and the expectations of the millennial workforce through the degendering lens elucidates conceptualizations of gender constructions and power that limit inclusive practices and processes of organizational resilience. Data was used from focus groups of men and women between the ages of 21–35 (millennials) who have experience in the workplace and a shared knowledge of sustainability including social aspects of gender equity and inclusion. The Degendering Organizational Resilience model (DOR) was used for analysis to reveal barriers to inclusive, resilient organizational practices. The data was organized according to the three aspects of the DOR, power structures, gendering practices, and language. A unique contribution of this study is that it explores a cross-cultural gender perspective of organizational resilience focused on a specific cohort group, the millennials. Based on the findings three organizational recommendations for practice were identified. These include recommendations for policies and practices that deconstruct inequitable practices and co-create more agile structures, practices, and narratives for sustainable and resilient organizations.

Introduction

As predicted, modern society will increasingly be subjected to crises like the Covid-19 pandemic, that impact organizations, industries, and entire economies (Linnenluecke et al., 2012; Ross et al., 2015). Circumstances pressure organizations, to innovate, adapt and be responsive to new conditions e.g., high rates of unemployment, supply chain issues, health, and safety of employees/customers and uncertain futures (Barreiro-Gen et al., 2020; Fernandes, 2020). Pandemic challenges are occurring alongside a climate crisis as well as the exposure of structural racial inequities. Demands require organizational resilience in response to the triple sustainability challenge of addressing social and environmental issues alongside economic recovery (Lozano, 2018a,b; Barreiro-Gen et al., 2020). This is heightened by a recent shift in sustainability priorities since the covid-19 outbreak, a shift that emphasizes social priorities over environmental and economic (Barreiro-Gen et al., 2020). Concurrently, the largest generational group in the workforce is the Millennial generation, workers born between 1982 and 2004. Millennials are a generational cohort group that encompasses values that challenge predominant assumptions and power structures in relation to equity and sustainable futures (Calk and Patrick, 2017; Risman, 2018). The convergence of the pandemic, the climate crisis, and the Millennials' expectations place demands on organizations to be resilient, so they can be flexible and responsive to multiple changing conditions (Barreiro-Gen et al., 2020; Fernandes, 2020). These combined factors, point to the need for an inclusive understanding of organizational resilience, the agility to adapt, learn, and transform to rapidly shifting external and internal conditions (Sheffi, 2015; Branicki et al., 2016; Witmer and Mellinger, 2016).

The challenge this paper addresses is that during times of crisis sustainable organizations require the full scope of resilient capacities. Present constructions of organizational resilience favor traditional masculine coded practices (e.g., hierarchical, tough, strategic) marginalizing feminine coded aspects (e.g., collaboration, reflection, innovation), equally valuable to organizational resilience, aspects that are necessary for organizational change and adaptation (Lozano, 2018a,b). Using the degendering organizational resilience (DOR) model of analysis, this paper explores the exclusion of organizational resilience qualities from theory and practice for sustainable organizations not because of their lack of value but due to their gender weighted associations. Thereby limiting equitable participation during change processes.

At present there is an absence of a gendered discussion on organizational resilience in sustainable organizations from the millennial perspective (Omilion-Hodges and Sugg, 2019). Definitions of organizational resilience, favor concepts associated with masculine constructions of organizational forms and power dynamics. These aspects emphasize hierarchical detachment and control to the exclusion of feminine coded constructs such as collaboration, emotional engagement and reflection (Calas and Smircich, 2005, 2014; Witmer, 2019). If the influence of a binary gender perspective of organizational resilience is not continually acknowledged and explored a faux ungendered perspective of organizational resilience will continue to be perpetuated. This gendered, unequal representation gives the impression that sustainable organizations are rational neutral places where everyone has an equal opportunity unbound by gender associated constructions. In contrast, by acknowledging social constructions of gender and its contribution to the theoretical development and practices of organizational resilience one can challenge current and dominant conceptualizations of organizational resilience toward a more inclusive perspective (Martin, 2006). An inclusive perspective that more accurately reflects practices that equip an organization to be agile and resilient during times of crisis.

The millennial generation is the group most represented numerically in the workforce, they are characterized as innovative and entrepreneurial, have a high commitment to issues of sustainability and equity and share a critical perspective of formal organizational structures (Singh et al., 2012; Calk and Patrick, 2017; Valenti, 2019). The target group in this study are also actively pursuing higher education in the area of sustainability to become sustainable entrepreneurs and leaders in areas of social equity, climate change, urban development and sustainable consumption (Lozano, 2018b). Within sustainable organizations, leadership, and the promotion of sustainable values is often generated from a top down perspective and limited to a few powerful individuals (Bendell and Little, 2015). This type of hierarchical Weberian leadership constricts the influence of organizational sub cultures such as millennial groups of employees and also limits innovation that contributes to organizational resilience (Ramona, 2013; Bendell and Little, 2015; Lozano, 2015).

This paper explores processes of organizational resilience from a gender and equity perspective and how it is perceived in practice by the millennial generation in the workplace. The aim being to expose and eventually deconstruct the influence of oppressive power structures that limit a sustainable organization's resilient capacity to adapt, respond, and innovate during times of crisis. Data was gathered from focus group interviews comprised of millennial men and women between the ages of 21–35. The participants had experience in the workplace, experience working with sustainability issues and academic knowledge on sustainability. The data was analyzed using the Degendering Organizational Resilience model (DOR) to explore millennial perceptions and experiences of organizational power structures, practices and narratives in relation to organizational resilience and inclusive processes for sustainable organizations. The research questions were: RQ 1: How are gendered constructions of organizational resilience discussed by aspiring millennial leaders? RQ 2: How are they formulated within the context of organizational power structures, practices/processes and narratives? RQ 3: What are the implications for degendering organizational resilience in both theory and practice as applied to sustainable organizations?

The paper is structured as follows: First, a theoretical foundation is established on gendered resilient organizations, sustainable organizations and leadership and the millennial generation. This is followed by the methods section including a description of the degendering organizational resilience (DOR) model, and its application to analysis. Next are the findings, discussion and conclusion sections that outline the implications for degendering the concept of organizational resilience toward inclusive practice and theory development. The aim being to provide an example whereby feminine and masculine coded practices of resilience can conjointly contribute to resilient sustainable organizations.

Theoretical Foundation

Organizational Resilience

In a resilient organization the attributes of flexibility and agility are fundamental characteristics of the organization imbuing it with a constant state of readiness to go through cycles of learning, innovation, and transformation (Westley, 2013; Zolli and Healy, 2013; Mallak and Yildiz, 2016). This definition distinguishes resilience from a response to a single event that returns an organization back to its original state. Instead it is a dynamic process whereby an organization as a collective of people and processes is constantly learning and adapting to its context (Limnios et al., 2014; Witmer and Mellinger, 2016; Duchek, 2019). Based on the latter definition, when faced with an unexpected short- or long-term challenge, such as a pandemic, a resilient organization reorganizes itself and increases its collective capacity toward transformative change and often a new definition of normal (Hamel and Valikangas, 2003; Westley, 2013; Duchek, 2019). Resilient organizational practices include but are not limited to a shared commitment to the organization's mission, reciprocity between the organization and the community where it operates, collaborative, and strategic decision-making processes and a shared value of learning and innovation (Lengnick-Hall et al., 2011; Witmer and Mellinger, 2016).

Resilience as positioned within organizational scholarship is vulnerable in its construction to gendered organizational power dynamics that favor normative masculine practices as the “ideal” organizational form. Constructing the theory of organizational resilience in the context of normative perceptions of masculinity and femininity, positionions what is identified as masculine as the good and acceptable aspects included in theory while subordinating, and at times excluding, what is perceived as feminine and “other” than the “ideal” male (West and Zimmerman, 1987; Connell, 2002; Bendl, 2008; Calas and Smircich, 2009). This is in direct contrast to a resilient organization that depends on both masculine coded aspects—strategic thinking and directive problem solving as well as feminine coded aspects of cooperation, inclusivity, and collective transformation. These are all elements that equip organizations to be resilient as they adapt to existing crisis and/or prepare for future conditions (Martin, 2006; Witmer and Mellinger, 2016).

Challenging current and dominant conceptualizations of resilience through a degendering lens can reveal which resilient properties receive status based on established gendered organizational conditions (Acker, 1990; Butler, 1990; Nentwhich and Kelan, 2014). If conceptualizations and practices of organizational resilience are not challenged, gendered constructs that reinforce what is good and acceptable will continue to influence which resilient practices receive status and thereby control organizational discourse and processes that enforce a binary perspective of organizational behavior and constrict the full scope of organizational resilient practices (Acker, 1990; Crevani, 2015). These non-reflexive practices, where people act without being aware of how gendered assumptions influence their actions, if unchallenged, could subjugate, and marginalize organizational practices that are valuable aspects of organizational resilience but are eliminated due to being categorized as feminine practices (Martin, 2006).

Organizational Resilience, Gender, and Power

Organizational resilience is enacted during times of high stress when organizations typically turn to normative masculine practices of rationality and reason to address “tough” problems (Hamel and Valikangas, 2003; Kantur and Iseri-Say, 2012; Kantur and Say, 2015; Mallak and Yildiz, 2016), thereby marginalizing normative feminine practices of collaboration, learning, and creating a safe emotional environment which are equally crucial to organizational resilience (Gittell, 2008; Ely and Meyerson, 2010; Van Breda, 2016). Resilience thrives best in contexts of shared power, decentralized decision-making, and team based or network structures (Weick and Sutcliffe, 2007; Lengnick-Hall et al., 2011). In contrast, patriarchal structures with hegemonic masculine management practices support an unequal gendered order, which define and limit who has access to resources and to the broader space where innovative decisions are made that could lead to resilience (West and Zimmerman, 1987; Walby, 1990; Billing, 2011).

One of the key aspects of resilience is bricolage, which requires access to material and human resources to facilitate inventiveness and innovation (Kantur and Iseri-Say, 2012; Kantur and Say, 2015; Kossek and Perrigino, 2016; Mallak and Yildiz, 2016). To easily access these resources means that they must be available and accessible within the organizational “space” where problem solving and decision making occurs. If voice and the valued space for practice are limited by unequal power distribution encased in gendered relationship of power and further entrenched in unreflexive practices/practicing of masculinities and femininities, then the organization's ability to practice resilience through collaborative reflection, learning, and transformation is at risk of being restricted (West and Zimmerman, 1987; Martin, 2006, 2013). Degendering the physical space where resilience is practiced can remove these binary gendered distinctions and open the way to incorporate all aspects of organizational resilience such as strategic adaptation and innovation (Lorber, 2000; Duchek, 2019).

Job roles, access to power and resources are often bound by gendered organizational constructions and practices, creating power imbalances by excluding non-hegemonic male actions thereby determining what is valued and which voices are heard in the workplace (West and Zimmerman, 1987; Martin, 2013; Liu et al., 2015). These gendered boundaries structure the daily work life in organizations and can include or exclude practices of organizational resilience depending on their association with the less valued gendered role. This association is exacerbated when roles are imbued with power within the organization's structured hierarchies, reinforcing precedence to a specific type of gendered voices (Nentwhich and Kelan, 2014). The process of acknowledging embedded gendered practices through reflexive practices as used in this study can reveal how institutionally embedded inequalities are enacted and hinder theory development of inclusive organizational resilience practices (Martin, 2006, 2013).

The Millennial Generation in the Workplace

The Millennial generation, those born between 1982 and 2004, are expected to make up 75% of the workforce by 2025 (Valenti, 2019). This group of workers brings a unique set of sustainable values, beliefs, needs and attitudes to the workplace. In relation to gendered constructs and organizational resilience, the voices of this dominant cohort are largely absent (Thompson and Gregory, 2012; Calk and Patrick, 2017; Omilion-Hodges and Sugg, 2019). As a group, Millennial employees have different ways of prioritizing their work needs than other generations. They tend to embrace values beyond economic gain and advocate for practices that value equity, sustainability, and worklife balance (Calk and Patrick, 2017; Omilion-Hodges and Sugg, 2019). Many are not bound by gender roles, or expectations at home or in school and hold a feminist ideology of equity and inclusion that they bring with them as a baseline assumption into the workplace (Risman, 2018). As a group, they generally have a shared value of individualism, a distrust of institution's and a tendency to trust in individual networks rather than corporate networks (Williams et al., 2017; Risman, 2018). These beliefs appear to be further reinforced by the contextual underpinning of neoliberal feminism that prioritizes individual responsibility over organizational and social constructions of power (Rottenberg, 2019). These compounded values and individualized perspectives can limit this generational group's willingness to contribute to workplace goals that influence the sustainability of organizations (Thompson and Gregory, 2012; Calk and Patrick, 2017; Rottenberg, 2019).

In relation to leadership they have a higher need for a meaningful relationship with their direct supervisor who they view as mentors to their personal and professional process of growth and development (Calk and Patrick, 2017). They view the organization as a place where they can learn and grow as individuals (Omilion-Hodges and Sugg, 2019). They view leadership as a co-creation, collaborative process rather than one powerful individual making the decision for many (Ferdig, 2007; Quinn and Dalton, 2009; Duchek, 2019).

As the largest generation represented in the workplace, this group has power to create a critical mass for change that could influence future conditions in relation to equity and organizational resilience in sustainable organization. Their detached relationship to organizations offers a more objective workplace perspective of a beginning or mid-career professional who are aware of, but not necessarily bound by, existing organizational logics (Risman, 2018; Thompson and Gregory, 2012). Acknowledging their reticence, once engaged their collective insights could assist in deconstructing organizational processes, structures and narratives that perpetuate oppressive power structures on a systemic level (Nyberg, 2012; Calk and Patrick, 2017). A contribution that could open the way to innovative processes and sustainable solutions not previously recognized.

Studying a group as a collective cohort has inherent strengths and weaknesses. The strength is that they have similar experiences at a specific point in time in history. This can contribute to a shared narrative in relation to the impact of climate crisis or a pandemic. The weakness is that their collective experiences are also influenced by individual aspects such as personality and gender. This study acknowledges that while people and their experiences are complex the literature supports that there are shared and identifiable characteristics that are unique to this group as a whole that influences their perspectives of the workplace (Boone, 2016).

Sustainable Organizations and Leadership

There are multiple definitions of sustainable organizations; all include strategies for economic environmental and social aspects of organizational performance as well as their interrelations within and through time dimensions (short, long, and longer term impact) (Rodriguez-Olalla and Aviles-Palacios, 2017; Lozano, 2018a,b). Organizations share in different strategic sustainable priorities based on the purpose of the organization and the alignment of economic, environmental, and social priorities (Lozano, 2018b; Purvis et al., 2019). Leadership as a core component of sustainable organizations influences strategy, decision making, agenda setting and innovation in relation to sustainabile change and the role of managers (Rodriguez-Olalla and Aviles-Palacios, 2017; Batista and de Francisco, 2018; Lozano, 2018a,b). Ethical or values-based leadership is often viewed as a key component of sustainable change. Based on values that are a part of organizational cultural norms that often occur non-reflexively (Bendell and Little, 2015; Lozano, 2018b). It is both the combination of individual leadership practices and organizational processes that contribute to sustainable organizational leadership. Leaders and managers create alignment and maintain organizational comittment as drivers of sustainable change (Quinn and Dalton, 2009; Batista and de Francisco, 2018). Sustainable leadership practices and processes define, reward, and thereby shape a work context of long-lasting sustainable corporate change (Lozano, 2018b).

Leadership for sustainability is a systemic process that is in many ways is antithetical to mainstream leadership approaches that are embedded in traditional organizational power dynamics (Bendell and Little, 2015). Power dynamics that are based in traditional Weberian structures that favor top down, upper management perspectives and limit sustainable leadership to a few key leaders. The later as contrasted to a complex, systemic process that enages internal and external stakeholders in the process of creating shared value (Quinn and Dalton, 2009; Ramona, 2013; Bendell and Little, 2015; Lozano, 2015; Barreiro-Gen et al., 2020).

Despite this understanding of what is needed, what is typically found within sustainable organizations, is the promotion of sustainable values from a traditional top down perspective that is limited to a few powerful individuals (Bendell and Little, 2015). This type of hierarchical leadership constricts the sharing of power thereby limiting collaborative, systemic processes and broad engagement. Processes that exclude the influence of less-powerful organizational sub-cultures and members (Ramona, 2013; Lozano, 2015; Uhl-Bien and Arena, 2017). In contrast, the systemic process perspective of sustainable leadership embraces complexity, engages multiple stakeholders, includes intra-organizational communication, and encourages knowledge sharing (Ramona, 2013; Bendell and Little, 2015; Uhl-Bien and Arena, 2017; Lozano, 2018b).

To move away from the traditional organizational leadership approaches to an integrated process perspective of sustainable leadership entails a deconstruction process of leadership practices. This includes the exposure of widespread discourses, organizational norms and assumptions that perpetuate, oppressive power relations. What is offered in this study, is the exposing of resilient practices of organizational leadership as a frame for exploring what needs to be learned and unlearned (i.e., abandoning of old routines, behaviors, and beliefs) to move toward inclusive defintion of organzational resilience for sustainable organizations (Bendell and Little, 2015; Orth and Schuldis, 2020).

Research Design and Method

The study was based on data from millennial focus groups designed to obtain a general understanding of Millennials collective perceptions of organizational experiences of gender, equity and sustainability. The millennial group was selected as the focus due to their knowledge and commitment to sustainability. They are also the largest generational group represented in the workplace thereby, influenced by present conditions and positioned for future influence on workplace conditions in relation to sustainability (Risman, 2018).

Participant Selection

The participants selected for this study were a part of the millennial generation ranging between ages 21–34, they had workplace experience, had functioned in formal or informal leadership roles. All had expressed the aim of being sustainability leaders, managers or entrepreneurs in areas such as climate change, social equity, and sustainable consumption. A total of 70 international students were invited by email to participate in the study. Twenty-two individuals chose to participate they were representative of multiple organizations and industries that ranged from engineering, media marketing, NGOS, and international relations. All participants had knowledge of sustainability as acquired through higher education. Their countries of origin or residence represented 5 continents (Africa, Asia, Europe, North America, and South America). Each participant had a high level of English proficiency. Participants identified as male (13) and female (9) with none indicating as other. Approximately half of the participants in each group had a previous interaction with someone else in the group, in a social and/or academic context.

Research Method

There were five focus groups that were a combination of gender exclusive and mixed gender groups. Participants chose which group to attend based on their availability. The focus groups occurred over a 3-month time period, for approximately 90 min each. All were conducted in university conference rooms. The focus groups were recorded and transcribed in English. Notes were also transcribed by the moderator or co-moderator during the focus group interview.

Focus groups were selected as the method for data collection due to the effectiveness of focus groups in providing insights into how people in groups perceive and make sense of situations as a collective (Krueger and Casey, 2009; Onwuegbuzie et al., 2009). The focus group method provided the space for participants to construct their answers in a collaborative process thus providing a safe venue for open discussions around sensitive issues such as gender and power (Onwuegbuzie et al., 2009). The open format of a focus group also enabled interactions that drew out new and relevant insights regarding processes of de/construction and shared meaning making (Krueger and Casey, 2009). The heterogeneous nature of the groups provided a milieu for participants to challenge each other's ideas and trigger discussions that challenged normative assumptions about gender and power.

The focus group questions were about gendering structures, gendering actions, and gendering language in relation to organizational leadership and resilience. In line with the focus group format, open ended questions were posed to the group for discussion around specific topics, allowing space for the group to collectively shape their own narrative (Onwuegbuzie et al., 2009). The focus group questions were constructed to facilitate discussion between participants, with occasional prompting by the facilitator on the topics germane to the study e.g., gender and leadership, influence in decision making, and positions/roles within the organizational structure (Onwuegbuzie et al., 2009).

Data Analysis

The data was first analyzed to identify emergent themes in the areas of leadership, gender, power and influence in decision making (Strauss and Corbin, 1998). The themes were then grouped into categories according to key aspects of the DOR model, (1) power structures, to identify access to resources in relation to differing levels of power according to organizational role and position; (2) gendering practices and the practicing of gender, to identify how resilience is enacted through actions and interactions; (3) language, to identify narratives of collective practicing of masculinities and femininities that are embedded in the organization's story and culture (Witmer, 2019). After the focus group data was compiled, feedback workshops occurred for the purpose of discussing, reviewing, and adapting findings based on the groups' collective input.

Limitations

Studying a group as a collective cohort has inherent strengths and weaknesses. The strength is that as a group they have experienced the same political and economic conditions at the same point in history and at a similar point in their professional and personal developmental process. This shared experience contributes to similarities in the constructed understanding of society and the workplace (Boone, 2016; Omilion-Hodges and Sugg, 2019). The weaknesses are found in the intersectionality of multiple influences that affect individual responses to identical events such as national culture, race, economic class, and personality. There are also cultural differences based on the political context. For example Swedes are further along in their valuing of gender equality due to the underpinning philosophy of the Social Democratic political system where equality is valued over individualism (Schewe et al., 2013). This study acknowledges that while people and their experiences are complex that the literature supports that there are shared and identifiable characteristics that are unique to this group as a whole that influences their perspectives of the workplace. In addition this generational group, all see themselves as a part of a global community (Schewe et al., 2013; Boone, 2016). A different research design would need to be selected for a more precise focus on the influence variables such as industry, nationality, or personality of the participants.

Findings

The purpose of this research was to explore a gender perspective of organizational resilience of aspiring millennial leaders for sustainable organizations. The degendering resilience model was used as a critical feminist lens of analysis to reveal conceptualizations of gender constructions and power that limit inclusive practices and processes of organizational resilience. Gender was analyzed as something someone performs based on the social constructions of a particular context not something someone possesses (Butler, 1990). In this study, the value or weight given to voices based on gender was viewed as a representation of the value of gender associated qualities that are ascribed as masculine or feminine (Knights, 2009; Branicki et al., 2016). The clusters of traits, not the individual is the focus of the study which may or may not align with the gender of the individual.

Research Question 1: Millennial Gendered Constructs

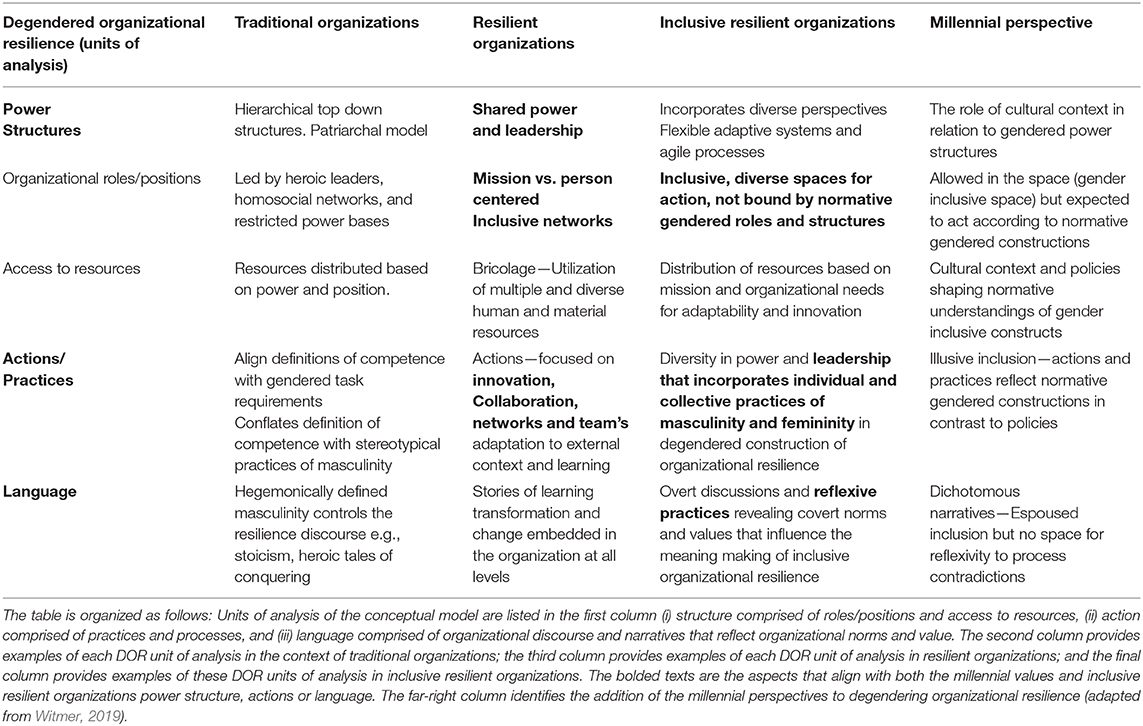

In response to research question 1: How are gendered constructions of organizational resilience discussed by aspiring millennial leaders? The findings highlight that millennials valued a collaborative style of leadership, look to individual mentors for their leadership training and development rather than corporate structures and processes. An example of this perspective is illustrated in the following quote: My best experiences have been with leaders who have been experts at being relational not just the objective but care enough to get into your world. The participants as a whole were also critical of hierarchical structure and distrustful of power that was limited to an individual vs. a collaborative processes. The following is how one millennial described their understanding of collaborative leadership: Being closer to citizens, communities … leadership is also about personality and sharing experiences and empowering people and offering opportunity to get new skills based on others experiences. Many of these aspects align with both the research on millennial values and inclusive resilient organizations. Table 1 illustrates through the use of bolded text, the aspects of millennial leadership that align with aspects of resilient organizations.

Table 1. The table illustrates how the DOR model can be used to analyze resilient practices in three types of organizations.

Research Question 2: Millennial Constructs and the DOR Model

To answer research question two, how are millennial perceptions formulated within the context of organizational power structures, practices/processes, and narratives, the data was analyzed based on the three categories of the DOR model. The three categories are power Structures, actions and language. In Table 1, the far-right column identifies the addition of the millennial perspectives to degendering organizational resilience. Descriptive examples of each category are described in the following section.

Power Structures

In this study power structures were analyzed based on access to resources and ability to influence decisions as reflected in roles/positions. Power in this study was not viewed as an innate individual capacity but as something located in an institutionalized structure and enacted through practices, policies, and systems of relations (Foucault, 1998). What emerged from this set of findings was the macro influence of national culture on organizational policies and perceived power differentials. Although culture specific differences have been found to influence sustainability in global markets, there has not been much research in this area on an organizational level (Schewe et al., 2013; Jeong and Park, 2017).

Cultural Context and Policies

In half of the focus groups, the starting point of the discussion on power and gender referenced organizational policy as a reflection of cultural gendered norms

“In our country gender is a non-issue. We have gender mainstreaming policies in place where everyone is treated equally in addition women are much more educated than men. It is a gap that is getting really big (female, Millennial).

Our organizations don't have policies like that there are less women in the workforce, that is just how our country works (male, Millennial)

The first example, references the policy of “gender mainstreaming” (Daly, 2005), illustrating how organizational policies are influenced by political mandates that reinforce societal (cultural) values of equity and inclusion. In the second example the lack of policies reflected the same understanding that there was no need for organizational policies because societies social constructions did not mandate the need. These examples, illustrate how organizational policies and practices can be bound by the cultural norms of the physical cultural context of the company vs. being determined by broader global discourses in relation to gender and power. This form of bounded rationality, was challenging for the millennials who had been exposed to the global discourses of social sustainability such as gender equity. They viewed themselves as global citizens but were bound by organizational norms that were bound cultural context.

It is not surprising that organizations as societal constructs mirror the norms of their context, what was unique was the identification and sense of empowerment individuals expressed when aligning with countries that had more equalitarian policies. The empowerment was a type of hierarchical elevation among focus group members in contrast to assumed lesser positions of power ascribed to cultures with patriarchal norms. For example, the first quote was asserted by a female, who spoke quickly about policy as both a way to establish her own right to speak in the group as well as using the policy to establish the superior positioning of her cultural norms. The policy was perceived as giving her the power to speak, to speak first, and to guide the focus group conversation. The power legitimized by corporate policy and cultural norms. The second response was by a male whose body posture indicated a reluctance to respond, an embarrassment that seemed to be related to the cultural patriarchal norms of his home country. His association with the company's practices and cultural patriarchal norms, decreased his perceived sense of power among his peers who asserted a more equalitarian view of gender. This power dynamic appeared to reflect a hierarchy of shame based on what were perceived as the more socially “gender equity advanced” countries and less progressive countries.

Some of the participants reported the compounded tension of societal and organizational expectation, implying that they have two systems (Societal and organizational) imposing different values creating dual pressure on their individual sensemaking processes as well as their organizational engagement.

From my perspective, it's still extremely challenging because it's like the tables are turning and now females are expected to do so much and be so much. It's so much pressure, but the other way around, because you're supposed to do so many things: to have a family, to be a great mom, to be a leader at work, to work out and have a perfect apartment. And, I see that more in developed countries. It feels like here (developed country) there's the pressure for male and women, but especially for female, to be perfect or have perfect lives and I'm not sure that's possible, and it shouldn't be demanded or expected of male or female. So, even in societies where you have more equal roles where you both take care of the kids or do the cleaning at home, still it feels like women tend to be expecting of themselves or expected by society to fulfill all the roles, including leadership in every area of their lives and that's unfair and unrealizable (female, Millennial).

This quote highlights that they may have equal opportunities in the workplace but due to societal norms and expectations they may not have equal support outside of the workplace. Furthermore, this can be exacerbated if working internationally where the context is incongruent with the organization's values. In this way they are embodying a similar tension to what organizations are experiencing, how to align organizational policies with cultural context and employee needs. The millennials as caught in the nexus of this dilemma on both a conceptual and individual level. They viewed themselves as global citizens yet they were still bound, and at times marginalized by the norms of their national culture.

Organizational Roles and Positions (Illusive Empowerment)

Upon further reflection and discussion among focus group members, they found that within organizations, inclusive policies offered initial but not sustained power. The women in countries with progressive gender equity policies were talked about in equal term with equal gender weighting to feminine coded and masculine coded workplace behavior however in practice the actions aligned with normative masculine gendered expectations.

As illustrated in the following quote:

..the more I think about it, I realize that although it looked like the women had equal opportunities, that the only time the one female on our leadership team was asked to provide input it was in relation to a product being sold to women….There was not a single girl in the video department. The ones working the equipment - Producing, editing, practical work only done by males (even though all had the skill sets). Then there were 4 guys working on a cosmetic case and then they thought maybe we should include a women in the producing and editing (male, Millennial).

Whereas, the next quote is from a country where there are few if any political mandates for gender equity. Another example of how workplace norms reflected societal norms.

“the women took care of birthdays and social events, it is just expected” (female, Millennial).

These quotes illustrate that the companies with gender policies, appeared to give women, and by association feminine coded behaviors a “seat at the table,” however once at the table they had to prove themselves in a different way than their male counterparts and/or they were assigned to tasks considered feminine. In this way reinforcing a male gendered hierarchy that elevates both men and masculinity as acceptable, normative, and often the preferable organizational behavior that is rewarded with power and position.

Actions/Gendering Practices

To degender organizational resilience it is important to look at both intentional practices of doing gender but also unintentional practices of doing gender. Gender differences are enacted through men and women as they participate in the act of socially constructing each other through gendering practices in the work environment (Martin, 2006: Deutsch, 2007). Analyzing gendering processes can provide insight into the collective practicing of masculinities and femininities in order to understand if certain actions receives higher value based on their gendered association rather than their contribution to an organization's resilience during times of crisis (Lorber, 2000; Collinson and Hearn, 2005; Connell and Messerschmidt, 2005; Martin, 2006, 2013).

The Gender Weighted Workplace

The participants reported that although in many of their organizations there was an emphasis on equal representation based on meritocracy that they were only validated when they acted in accordance with normative masculine attributes (e.g., strength and decisiveness) as described by the following participant:

Not fighting against, but acting male in some kind of ways, like being harder or pushing and using power and things to act more male than female (female, Millennial).

While others experienced masculinity as the dominant and preferred practice as acted out in the paternal pattern of all-knowing wise father and little girl. A pattern that could only be altered when women acted in accordance with normative masculine attributes of strength and decisiveness as described by the following interviewee

…..I think it took me a few months before they started to respect me and that they understand that I have the skills, because for them it was superficial like “that's just a little girl how can she know, how can she have the responsibility to tell me what to do?” (female, Millennial).

While in contrast others did not experience gendered distinctions:

Personally, it never felt like I was being treated differently as a woman. For example, in the last place where I worked there were two people who have the same possibility or potential. It was the guy who actually became the manager. He was the replacement of the leader who was a male. I don't think he got it over me because he was a male, I don't think that way, I think it was because he has been there longer, I never think it is because of gender, maybe he is better at dealing with the other people. Or maybe he had more experience in the field (female, Millennial).

This contradiction could be reflective of the dissonance the Millennials experience in the workplace. They describe being caught in both their individual frustration of acting on personal values of equity within the workplace along with the organizational contradictions between espoused and practiced gender policies and actions.

In the following example, even though a woman had a gender-normative masculine role in the organization, this person's level of influence (power) was described as follows by a male in the same position.

It is a male dominated culture, when women are in positions of leadership they are still asked to get coffee regardless of their position. I had one supervisor who was power hungry and anyone with less power than him could be asked to get him coffee. However, it was an unspoken option for a male to refuse but never for a woman to refuse. Furthermore, women would do the same thing as a male but would never be acknowledged (male, Millennial).

These examples illustrate that even if hiring practices are changed that concurrently there need to be processes for deconstructing embedded work place assumptions regarding function not just job titles. If it is only the titles that are given attention, an illusion of inclusion occurs, while binary distinctions in functions are perpetuated and masculine organizational practices continue to be elevated (Scholten and Witmer, 2017).

An interesting point about the last example is that it was put forth by a homosexual male who described his reflections on his own process. He explained how he learned to conduct himself in accordance with hegemonic masculine expectations in the workplace. Describing it as a persona that he did not identify with but had to adopt to gain legitimacy and power. He observe that this masculine persona is easily accepted and quickly legitimized for him as a male, albeit a homosexual male, while a female counterpart, acting in the same way is dismissed. He also identified that if his sexual preference was “discovered” that this would affect his “assumed” position of power. This illustration points to the tight linking of masculinity and power that is often double layered and points to the importance of decoupling these concepts to create space for removing binary distinctions that limit organizational resilient responses.

Masculine Gendered Tensions

Millennial males expressed a different type of societal and organizational tension that resulted in high levels of frustration and what they described as guilty by (male) association. The millennial men expressed being in a double bind, expressing that their generation had been raised with a gender equity perspective yet in the institutions they enter “they get treated as an offender of the gender code, just by nature of being male” they as men are expected to operate according to hegemonic masculine behavior (assertive, aggressive, competitive) and on the other hand are demonized for being male (accused of having positions of male privilege). As one interviewee said—I don't want to be put in the same category as those old white men who are accused of abusing their power to oppress others!

The pressure that was initially described as external (other's ridicule) was further exacerbated by their own internal dissonance. They described the internalization of a gender fluid identity as compared to a binary definition yet they were unsure how to express this gender integrated approach in the workplace. This dissonance is reflected in the following quote:

I'm also more of a feminine man. It's like if you think from the biological side, you have the extreme male and the extreme female, and you have everything in between. And, of course, we can say we are a little bit more in the middle. This makes the whole discussion more difficult, because you don't know where you are, you're not just this or this, you're somewhere maybe in between, and you have to fulfill certain roles or certain things. Are you like this very masculine man or.? …. Of course you somehow want to be masculine, but also want to be empathetic. This is like the new roles that men have to fit (male, Millennial).

Language: Entrapment Between Narratives

The last category of the DOR is language, how gender is talked about. As a group the Millennials espoused values of equity and inclusion however when providing narratives of their organizational experience they struggled with using inclusive language. For example: Female leaders tend to be more careful and care more about the emotions. Male seldom do these things (male, Millennial). Women get stressed out all the time so I am careful around them, not to stress them out (female, Millennial). In their language they expressed greater value on masculine associated traits of individuality and strength as characteristics of change agents and feminine characteristics such as compassion and collaboration as weaker less valued aspects in need of protecting. These responses are consistent with normative organizational narratives, what is atypical was their apparent discomfort between their self-assessment as gender inclusive and the binary-gendered narratives that were reflected in the focus group discussions.

The participants expressed feeling that they are walking a fine line between the taboo of discussing issues related to gender equity as well as being responsible to bring about future change. They also expressed that there is not a physical or virtual space where they can give voice to internal and external contradictions.

As poignantly stated in the following quote:

…just like climate change. These (gender issues) are problems that others have created but we, our generation is expected to fix it !” (male, Millennial).

These quotes highlight the Millennial generations unique positioning of both observing the tension between philosophical equity and practice and their personalized experience of this phenomenon. Although typically millennials value independence and are reluctant to trust formal organizations, engaging them in issues of sustainable development such as equity and climate change could benefit themselves society and the organization. Their engagement in these issues could expose both their own dissonance and organizational contradictions that hinder inclusive practices of organizational resilience.

Reflexivity as an Example of Change

What follows is an example of how change through reflexivity could occur. This example occurred as a part of the focus group, whereby the focus group functioned as a “mini-learning lab.” This intervention illustrates the potential for changing perceptions through open inclusive spaces for reflection, discussion, and learning. What started as a discussion in response to assumed norms around masculine and feminine coded actions evolved into a more reflective and collective discussion of incongruencies between practice and values. As they began to step away from what they described as political rhetoric they began to articulate their own shared understandings and frustrations and began the process (as a group) of exposing gendered assumptions. As a group they began to deconstruct the contradictions between what they hoped and believed to be true in relation to gender, equity, and organizational resilience and what was being exercised in practice. The end result was the exploration of potential new frame for an inclusive narrative around the expression of masculine and feminine resilient actions in the workplace. This brief example points to the value of safe, inclusive spaces for learning and reflection to deconstruct restrictive organizational processes.

Discussion

What emerged from the findings was a motivated cohort group that felt empowered as individuals to bring about social change for a sustainable future, however within the organizational context they felt frustrated and powerless to affect organizational change due to limited gender weighted perspectives of organizational resilience. Their frustrations were due to competing tensions that fell into three key area: (1) A layering of power factors (cultural, organizational, and individual), (2) Millennial embodiment of organizational gendered tensions, and (3) Entrapment between narratives. What follows is a discussion that incorporates these aspects with existing theory for the purpose of revealing ways to engage the millennial generation in deconstructing gender associated power structures toward inclusive practices of organizational resilience.

In relation to gender coded aspects of resilience and organizational practices, the practices the millennial group reported consistently illustrated that the sex (sex as biological distinction vs. gender preference) of the individual as well as the gendered association of the action quickly tipped the power imbalance in favor of men and masculine practices. The highest imbued power favored stereotypical masculine expressions when expressed by men regardless of their position within the organizational hierarchy. Including masculine aspects of organizational resilience such as rationality and logical reasoning to address “tough” problems (Hamel and Valikangas, 2003; Kantur and Iseri-Say, 2012; Kantur and Say, 2015). Much further down the value chain was women who exercised masculine constructions of resilience and last were women operating according to normative feminine practices. This organizational pattern reinforces the value of masculine coded resilience aspects and the marginalization of feminine coded practices such as collaboration, learning, and creating a safe emotional environment which are equally crucial to organizational resilience (Gittell, 2008; Ely and Meyerson, 2010; Van Breda, 2016). Limiting these aspects limits the capacity of the organization to respond with the full scope of resilient practices.

In practice organizational gendered hierarchies still remained intact highlighting the importance of undoing gender in social interactions (Lorber, 2000). Undoing gender is the first step in degendering with the aim of removing gender differences in positions where there is equal organizational power but unequal expression in practice. If this exercise is not employed, greater weight, and value will continue to be given to masculine coded organizational toughness, fortitude and logic and marginalize feminine coded practices of collaboration, compassion and creativity. For organizations to be resilient and adaptive, both masculine and feminine coded aspects of organizational resilience are needed (West and Zimmerman, 1987; Lorber, 2000; Deutsch, 2007; Billing, 2011).

In relation to organizational structures, the participants narratives reflected degendered conceptual views of organizations. In contrast, their descriptions of experiences aligned with a “traditional” Weberian view where organizations operate according to hierarchical structures run by bureaucratic management, where men occupy most influential positions of power (Walby, 1990). These organizational constructions, elevate masculine coded practices as the more valuable, powerful, and influential aspects of workplace practice (Acker, 1990; Calas and Smircich, 2009, 2014).

In relation to resilience, patriarchal structures with hegemonic masculine management practices such as described by the participants support an unequal gendered order. A gendered order which defines and limits who has access to resources and to the broader space where innovative decisions are made that could lead to resilience (West and Zimmerman, 1987; Walby, 1990; Billing, 2011). This frame of organizations, where gender is a primary means of signifying relationships of power, perpetuates oppression and power dominance that is limiting to organizational processes and thereby detrimental to women, men and the organization (Kanter, 1977; Walby, 1990).

The influence of power structures depended on a convergence of factors. An individual's position within the organizational hierarchy, organizational gender policies, and the gender coding of the action as masculine or feminine were interconnected in relation to power dynamics (Hirdman, 2003; Scholten and Witmer, 2017). Configurations of these factors determined who had power in relation to organizational influence. This is another illustration of how the millennials were entrapped between narratives. When they framed organizational resilience conceptually based on their personal believe system, they described a degendered conceptual view of organizational resilience. Power was described as embodied in an organizational system and enacted through policies and structures rather than an innate individual capacity (Foucault, 1998). When they described practices of gender within an organization, they saw it embodied in individuals based on the role and the sex of the individual. Men and masculine coded roles carrying the greatest authority and power. They observed an increase in relation to the number of women represented in the workplace and slight changes in gendered role perceptions. They observed the greatest leveling of power when the women exercised their agency, stood their ground and demonstrated competence. Although roles and positions were becoming more gender inclusive, in practice there were gendered distinction in function with the men taking on the more difficult tasks and in many cases women were represented in number only with little or no power to influence decision making (Scholten and Witmer, 2017). The unique contribution of this dynamic is the tension and discomfort expressed in relation to power being limited to sex and position and embodied in an individual. Herein lies the implications for organizational resilience, if power can be decoupled from organizational structure, roles and individual this can be a tipping point for degendering organizational resilience. This process has potential to shift the narrative away from the influence of women and men to power distribution based on what is needed for organizational resilience. This example highlights the need for organizations to incorporate reflexive processes that reveal and acknowledge embedded gendered practices (Martin, 2006, 2013; Witmer, 2019). The aim being to expose and deconstruct narratives that lead to further entrenchment of gendered norms and limit theorization and practice of organizational resilience to special forms of hegemonic masculinity (Connell, 2002; Connell and Messerschmidt, 2005; Bendl, 2008). When embedded inequalities are exposed they can be deconstructed and replaced with inclusive practices and processes of organizational resilience.

The Millennial Generation Tensions

Millennials prefer collaborative styles of shared leadership rather than heroic leadership and rigid organizational structures, aspects that are conducive to organizational resilience (Alvesson et al., 2009; Barasa et al., 2018). Bureaucratic management and hierarchical structure, are masculine constructions of leadership and are the antithesis of the millennial's preference for leadership and organizational conditions. As a group they are more comfortable with complexity and ambiguity, and value democratic processes where individuals work together making equal contribution to innovative solutions for complex leadership challenges (Ferdig, 2007; Quinn and Dalton, 2009; Pal et al., 2014; Barasa et al., 2018). The individualized network preference that the millennials share has relevance to two of the key challenges of organizational resilience, the ability to be flexible, and adapt to changing conditions and the value of collaboration (Williams et al., 2017).

Weick and Sutcliffe (2007), point to the connection between personal agency and contribution to the organization's ability to be resilient in a volatile and competitive environment. Without personal agency it is unlikely that individuals will contribute innovative ideas that lead to organizational agility and resilience. Here lies a serious problem, this group as a whole has potential to be an asset to the organization and its capacity to be resilient yet millennials are individualistic in their approach limiting organizational commitment and engagement (Chou, 2012; Singh et al., 2012; Calk and Patrick, 2017). As a group they are committed to larger societal goals and social values such as sustainability, they tend to distrust formal structures and corporate development programs, and value individual personal development and entrepreneurship (Chou, 2012; Singh et al., 2012; Calk and Patrick, 2017). Due to these individualistic values and loose commitment to formal organizations, the millennials are difficult to engage and retain in the workplace (Thompson and Gregory, 2012; Calk and Patrick, 2017). This lack of engagement creates multiple challenges for organizations, challenges that cannot be ignored because of the size of this group and the valuable perspective they bring to organizational resilience. Millennials bring innovation and a comfort with complexity that is a requisite for organizational resilience. They are also beginning or mid-career professionals who are aware of but not rooted in previous organizational constructions, thereby having the knowledge of how organizations operate but not being limited by existing practices and processes. This combination uniquely equips them to challenge structures and open the way for innovation which are also key aspects of organizational resilience (Witmer and Mellinger, 2016). Furthermore, based on numbers, they are the largest generational group in the workforce yet their voice is largely absent in workplace literature (Omilion-Hodges and Sugg, 2019). To empower their sense of agency, the Millennials as a group expressed a desire for there to be designated space in the workplace for collaborative, democratic processes where they are invited to discuss disparate messages between espoused equity and organizational practices. With an empowered sense of agency they could be engaged in contributing to increasing an organization's sustainability and resilience capacity by challenging existing structures and processes and promoting reflexive opportunities for learning, innovation, and transformation (Westley, 2013; Duchek, 2019).

Conclusion

During times of crisis all resources are needed for an organization to realize its resilience capacity. This process includes equally valuing all people as well as valuing each person's contribution without binary gender weighted distinctions that marginalize key aspects of organizational resilience. A unique contribution of this study is that it explored a cross-cultural gender perspective of organizational resilience focused on a specific cohort group. The Millennials are the largest cohort in the workplace. As a group the Millennials are committed to social values and equity however they are reluctant to commit to corporate cultures. Due to the numbers of millennials in the workplace as a group they have potential of creating a critical mass to influence narratives and workplace practices, furthermore they share a more equalitarian gender perspective, and sustainability. These combined attributes highlight the importance of finding ways to engage them in the process of building resilient organizations and contributing to sustainable solutions.

What emerged from the findings were competing tensions that hindered inclusive participation in resilient practices during times of crisis. The tensions were divided into three areas, (1) a layering of power factors (cultural, organizational, and individual), (2) Millennial embodiment of organizational gendered tensions, and (3) Entrapment between narratives.

Analysis of the data suggested that Millennials perceived organizational resilience differently than the existing theoretical binary perspective that associates resilience with machismo, stoicism and/or heroic tales of overcoming crisis (Branicki et al., 2016). They instead embrace a more integrated perspective that included feminine associated constructions of collaboration, and compassion as equally valuable to organizational resilience practices (Gittell, 2008; Van Breda, 2016). Despite this perspective, they had difficulty identifying examples of these constructions within organization as well as reconciling some of their own dissonance in relation to gender and equalitarian resilient practices.

Recommendations

Based on the findings, three organizational recommendations for practice were identified. These recommendations use the tensions as pivot points to deconstruct inequitable power structures and decouple gendered constructions from organizational resilience actions. The aim of this process is to 'increase organizations capacity to innovate by improvising and solving problems creatively in response to and/or preparation for external crisis conditions (Humphreys and Brown, 2002; Duchek, 2019). What follows are three recommendations for practice.

Recommendations for Practice

1) To adapt policies and align practices with policies. For example, create hiring criteria and performance review criteria that evaluate the gender weighting of “preferable attributes” and make adjustments by incorporating resilient attributes that are gender inclusive. In addition, allocate resource that create learning opportunities for innovation around topics of inclusivity and sustainable development. This would include creating groups that bring together people who cross over power boundaries created by organizational structure and gender bound assumptions.

2) To provide emotionally safe spaces for Millennials to discuss their opinions and reflections in relation to organizational challenges. For example, this could include innovation labs that are representative of cross-cultural, cross-departmental groups of millennials. The purpose for these groups would be to create new narratives/around inclusion and sustainability for building a resilient organization (Jørgensen, 2020). They could also be incorporated into existing organizational groups to integrate their perspectives as a part of ongoing organizational development. Their participation could provide insight for the organization (through their own experiences), on organizational barriers and challenges that hinder inclusivity and innovation in relation to organizational resilience and sustainability.

3) For organizations to evaluate their written and spoken language and create inclusive narratives and stories of equity and inclusion. This could include expanding the organization's narrative to include the organization's role as an actor in larger societal changes. A focus on creating shared value with the surrounding society, aligns with both, the millennial values of equity and sustainable development and a sustainable organizations shared value perspective.

Limitations

One of the challenges of this paper is the complexity of the convergence of multiple factors which made it difficult to identify primary and secondary influencers in the millennial groups sensemaking process e.g., organizational culture, national culture, industry or the norms of the focus group. Another challenge was distinguishing whether responses were attributed to a cognitive frame that was the result of being a part of a generational cohort group (experiencing world events at a similar developmental stage) or if responses were the result of a being at a developmental life stage (young adults, few responsibilities, new in their careers) and would change when circumstances changed. These challenges point toward opportunities for future research.

Future Research

This study offers many opportunities for future research including but not limited to the following areas (1) to distinguish and weight precipitating factors of degendering organizational resilience from an intersectionality perspective, (2) further exploration of the dissonance between espoused equity values and the organizations value from an organizational learning and organizational culture perspective, and (3) action research that uses story boards and living labs to create gender inclusive organizational resilience stories.

The point of departure for this paper was the exploration of inclusive processes of organizational resilience from a gender perspective as perceived in practice by the millennial generation in the workplace. The study revealed that limited gendered constructions of organizational resilience and existing power structures can restrict inclusive processes for innovation that lead to resilience during times of crisis. The recommendations highlight that using the tensions experienced by the millennials can facilitate conversations that create new frames for problem solving and innovation. These are perspectives that challenge gendered conceptualizations of organizational resilience as well as highlighting the importance of creating spaces for reflection and action. Incorporating a degendered perspective of organizational resilience that integrates masculine and feminine aspects of equal value can equip an organization to innovate, respond, adapt, and thrive, qualities requisite of resilient and sustainable organizations. Combined, this points to inclusive practices of organizational resilience that equip sustainable organizations for rapid responses during times of crisis such as a pandemic.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Acker, J. (1990). Hierarchies, jobs, bodies: a theory of gendered organizations. Gender Soc. 4, 139–158.

Alvesson, M., Bridgman, T., and Willmott, H. (2009). “Introduction,” in The Oxford Handbook of Critical Management Studies, eds M. Alvesson, T. Bridgman, and H. Willmott (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 1–26.

Barasa, E., Mbau, R., and Gilson, L. (2018). What is resilience and how can it be nurtured? a systematic review of empirical literature on organizational resilience. Int. J. Health Policy Manage. 7, 491–503. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2018.06

Barreiro-Gen, M., Lozano, R., and Zafar, A. (2020). Changes in sustainability priorities in organizations due to the COVID-19 outbreak: averting environmental rebound effects in society. Sustainability 12:5031. doi: 10.3390/su12125031

Batista, A. S., and de Francisco, A. C. (2018). Organizational sustainability practices: a study of the firms listed by the Corporate Sustainability Index. Sustainability 10:226. doi: 10.3390/su10010226

Bendell, J., and Little, R. (2015). Seeking sustainability leadership. J. Corp. Citizenship 60, 13–26. doi: 10.9774/GLEAF.4700.2015.de.00004

Bendl, R. (2008). Gender subtext – reproduction of exclusion in organizational discourse. Br. J. Manag. 19, S50–S64. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8551.2008.00571.x

Billing, Y. (2011). “Are women in management victims of the phantom of the male norm”? Gender Work Org. 18, 298–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0432.2010.00546.x

Boone, M. M. (2016). Millenial Feminisms: How the Newest Generation of Lawyers May Change the Conversation About Gender Equality in the Workplace. Baltimore, MD: University of Baltimore Law Review.

Branicki, L., Sullivan-Taylor, B., and Steyer, V. (2016). Why resilience managers aren't resilient, and what human resource management can do about it. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manage. 30, 1261–1286. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2016.1244104

Butler, J. (1990). Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York, NY: Routledge.

Calas, B., and Smircich, L. (2005). “From the woman's point of view: feminist approaches to organization studies”, in Studying Organization: Theory and Method, eds S. Clegg and C. Hardy (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications), 212–251.

Calas, B., and Smircich, L. (2009). “Feminist perspectives on gender in organizational research: what is and is yet to be,” in The Sage Handbook of Organizational Research Methods, eds D. Buchanan and A. Bryman (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications), 246–269.

Calas, B., and Smircich, L. (2014). “Engendering the organizational: feminist theorizing and organizational studies,” in The Oxford Handbook of Sociology, Social Theory, and Organization Studies: Contemporary Currents, eds P. Adler, P. Gay, G. Morgan, and M. Reed (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 605–659.

Calk, R., and Patrick, A. (2017). Millennials through the looking glass: workplace motivating factors. J. Bus. Inquiry 16, 131–139. Available online at: http://161.28.100.113/index.php/jbi/article/view/81

Chou, S. Y. (2012). Millennials in the workplace: a conceptual analysis of millennials' leadership and followership styles. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Stud. 2, 71–83. doi: 10.5296/ijhrs.v2i2.1568

Collinson, D. L., and Hearn, J. (2005). “Men and masculinities work, organization, and management connell,” in Handbook of Studies on Men and Masculinities, eds M. Kimmel, J. Hearn, and R. W. Connell (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.), 289–310.

Connell, R. W., and Messerschmidt, J. W. (2005). Hegemonic masculinity: rethinking the concept. Gender Soc. 19, 829–859. doi: 10.1177/0891243205278639

Crevani, L. (2015). Is there leadership in a fluid world? Exploring the ongoing production of direction in organizing. Leadership 14, 83–109. doi: 10.1177/1742715015616667

Daly, M. (2005). Gender mainstreaming in theory and practice. Soc. Politics 12, 433–450. doi: 10.1093/sp/jxi023

Duchek, S. (2019). Organizational resilience: a capability-based conceptualization. Bus. Res. 13, 215–246. doi: 10.1007/s40685-019-0085-7

Ely, R., and Meyerson, D. (2010). An organizational approach to undoing gender: the unlikely case of offshore oil platforms. Res. Org. Behav. 30, 3–34. doi: 10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.002

Ferdig, M. (2007). Sustainability leadership: co-creating a sustainable future. J. Change Manage. 7, 25–35. doi: 10.1080/14697010701233809

Fernandes, N. (2020). “Economic effects of coronavirus outbreak (COVID-19) on the world economy,” IESE Business School Working Paper No. WP-1240-E (Pamplona). doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3557504

Gittell, J. (2008). Relationships and resilience: care provider responses to pressures from managed care. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 44, 25–47. doi: 10.1177/0021886307311469

Humphreys, M., and Brown, A. D. (2002). Narratives of organizational identity and identification: a case study of hegemony and resistance. Org. Stud. 23, 421–447. doi: 10.1177/0170840602233005

Jeong, J. Y., and Park, N. (2017). Core elements for organizational sustainability in global markets: Korean public relations practitioners' perceptions of their job roles. Sustainability 9:1646. doi: 10.3390/su9091646

Jørgensen, K. M. (2020). Storytelling, space and power: an Arendtian account of subjectivity in organizations. Organization 1–16. doi: 10.1177/1350508420928522

Kantur, D., and Iseri-Say, A. (2012). Organizational resilience: a conceptual integrative framework. J. Manage. Org. 18, 762–773. doi: 10.5172/jmo.2012.18.6.762

Kantur, D., and Say, A. I. (2015). Measuring organizational resilience: a scale development. J. Bus. Econ. Finance 4, 456–472. doi: 10.17261/Pressacademia.2015313066

Knights, D. (2009). “Power at work in organizations,” in The Oxford Handbook of Critical Management Studies, eds M. Alvesson, T. Bridgman, and H. Willmott (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 144–165.

Kossek, E. E., and Perrigino, M. B. (2016). Resilience: a review using a grounded integrated occupational approach. Acad. Manage. Ann. 10, 1–69. doi: 10.1080/19416520.2016.1159878

Krueger, R., and Casey, M. (2009). Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research, 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Lengnick-Hall, C. A., Beck, T. E., and Lengnick-Hall, M. L. (2011). Developing a capacity for organizational resilience through strategic human resource management. Hum. Resour. Manage. Rev. 21, 243–255. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2010.07.001

Limnios, E. A. M., Mazzarol, T., Ghadouani, A., and Schilizzi, S. G. (2014). The resilience architecture framework: four organizational archetypes. Eur. Manage. J. 32, 104–116. doi: 10.1016/j.emj.2012.11.007

Linnenluecke, M. K., Griffiths, A., and Winn, M. (2012). Extreme weather events and the critical importance of anticipatory adaptation and organizational resilience in responding to impacts. Bus. Strategy Environ. 21, 17–32. doi: 10.1002/bse.708

Liu, H., Cutcher, L., and Grant, D. (2015). Doing authenticity: the gendered construction of authentic leadership. Gender Work Org. 22, 237–255. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12073

Lorber, J. (2000). Using gender to undo gender: a feminist degendering movement. Feminist Theory 1, 79–95. doi: 10.1177/14647000022229074

Lozano, R. (2015). A Holistic Perspective on Corporate Sustainability Drivers. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Mgmt. 22, 32–44. doi: 10.1002/csr.1325

Lozano, R. (2018a). Sustainable business models: providing a more holistic perspective. Bus. Strategy Environ. 27, 1159–1166. doi: 10.1002/bse.2059

Lozano, R. (2018b). Proposing a definition and a framework of organisational sustainability: a review of efforts and a survey of approaches to change. Sustainability 10:1157. doi: 10.3390/su10041157

Mallak, L. A., and Yildiz, M. (2016). Developing a workplace resilience instrument. Work 54, 241–253. doi: 10.3233/WOR-162297

Martin, P. Y. (2006). Practising gender at work: further thoughts on reflexivity. Gender Work Org. 13, 254–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0432.2006.00307.x

Martin, P. Y. (2013). Sociologists for women in society: a feminist bureaucracy? Gender Soc. 27, 281–293. doi: 10.1177/0891243213481263

Nentwhich, J. C., and Kelan, E. K. (2014). Toward a topology of ‘doing gender': an analysis of empirical research and its challenges. Gender Work Org. 21:2. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12025

Nyberg, A. (2012). Gender Equality policy in Sweden: 1970s−2010s. Nordic J. Work. Life Stud. 2, 67–84. doi: 10.19154/njwls.v2i4.2305

Omilion-Hodges, L. M., and Sugg, C. E. (2019). Millennials' views and expectations regarding the communicative and relational behaviors of leaders: exploring young adults' talk about work. Bus. Profess. Commun. Q. 82, 74–100. doi: 10.1177/2329490618808043

Onwuegbuzie, A., Dickinson, W. B., Leech, N. L., and Zoran, A. G. (2009). A qualitative framework for collecting and analyzing data in focus group research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 8, 1–21. doi: 10.1177/160940690900800301

Orth, D., and Schuldis, P. M. (2020). Organizational Resilience and the Roles of Learning and Unlearning: An Empirical Study on Organizational Capabilities for Resilience During the COVID-19 Crisis. Malmö: Malmö University. Retrieved from urn:nbn:se:mau:diva-21860

Pal, R., Torstensson, H., and Mattila, H. (2014). Antecedents of organizational resilience in economic crises—an empirical study of Swedish textile and clothing SMEs. Int. J. Product. Econ. 147, 410–428. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpe.2013.02.031

Purvis, B., Mao, Y., and Robinson, D. (2019). Three pillars of sustainability: in search of conceptual origins. Sustainability Sci. 14:681–695. doi: 10.1007/s11625-018-0627-5

Quinn, L., and Dalton, M. (2009). Leadership for sustainability: implementing the tasks of leadership. Corp. Governance 9, 21–38. doi: 10.1108/14720700910936038

Ramona, D. L. (2013). “Sustainable knowledge based organization from an international perspective,” in The International Journal of Management Science and Information Technology (Toronto, ON: NAISIT Publishers), 160–175. Available online at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/97844

Risman, B. (2018). Where the Millennials Will Take Us: A New Generation Wrestles with the Gender Structure. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Rodriguez-Olalla, A., and Aviles-Palacios, C. (2017). Integrating sustainability in organisations: an activity- based sustainability model. Sustainability 9:1072. doi: 10.2290/su9061072

Ross, A. G., Crowe, S. M., and Tyndall, M. W. (2015). Planning for the next global pandemic. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 38, 89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.07.016