94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Surg., 30 May 2024

Sec. Cardiovascular Surgery

Volume 11 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2024.1380570

Background: New-onset postoperative atrial fibrillation (POAF) is a common complication after pulmonary thromboendarterectomy (PEA), yet the risk factors and their impact on prognosis remain poorly understood. This study aims to investigate the risk factors associated with new-onset POAF after PEA and elucidate its underlying connection with adverse postoperative outcomes.

Methods: A retrospective analysis included 129 consecutive chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) patients and 16 sarcoma patients undergoing PEA. Univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted to examine the potential effects of preoperative and intraoperative variables on new-onset POAF following PEA. Propensity score matching (PSM) was then employed to adjust for confounding factors.

Results: Binary logistic regression revealed that age (odds ratio [OR] = 1.041, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.008–1.075, p = 0.014) and left atrial diameter[LAD] (OR = 1.105, 95% CI = 1.025–1.191, p = 0.009) were independent risk factors for new-onset POAF after PEA. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve indicated that the predictive abilities of age and LAD for new-onset POAF were 0.652 and 0.684, respectively. Patients with new-onset POAF, compared with those without, exhibited a higher incidence of adverse outcomes (in-hospital mortality, acute heart failure, acute kidney insufficiency, reperfusion pulmonary edema). Propensity score matching (PSM) analyses confirmed the results.

Conclusion: Advanced age and LAD independently contribute to the risk of new-onset POAF after PEA. Patients with new-onset POAF are more prone to adverse outcomes. Therefore, heightened vigilance and careful monitoring of POAF after PEA are warranted.

Chronic thrombotic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) originates from organized thrombosis and fibrous stenosis in the pulmonary artery, leading to reduced exercise capacity, dyspnea, and progressive right heart failure, and is Categorized as Group 4 pulmonary hypertension by the World Health Organization (WHO) (1), CTEPH poses severe life-threatening consequences, with a low survival rate if untreated. Patients with mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) >40 mmHg exhibit a 5-year survival of 30%, and the 5-year survival is only 10% among those with mPAP values exceeding 50 mmHg (2). Approximately 0.1 to 9% of survivors of pulmonary embolism eventually develop CTEPH (3), and nearly a quarter of CTEPH patients have no definite history of prior pulmonary embolism (4). The atypical early symptoms of CTEPH often lead to overlooked or misdiagnosed cases, suggesting that the incidence of CTEPH may be higher than reported in existing research (5).

Pulmonary thromboendarterectomy (PEA) stands as a potentially curative treatment for CTEPH by removing obstructions from the main pulmonary artery up to subsegmental levels, significantly improving patient survival compared to medical therapies (6). However, PEA is complex and challenging, associated with a high risk of mortality and complications (3, 7–9). Postoperative atrial fibrillation (POAF), a common occurrence in cardiac surgery, profoundly affects the postoperative recovery and prognosis (10). Some previous studies have confirmed that a percentage of patients experience atrial arrhythmias following PEA (11, 12). Despite this, existing studies have not comprehensively elucidated the risk factors related to new-onset atrial fibrillation after PEA, and there is a notable gap in research on the impact of new-onset POAF on early prognosis. This study includes common complications after PEA as adverse outcomes (in-hospital mortality, acute heart failure, acute kidney insufficiency, and reperfusion pulmonary edema). The primary objective is to assess relevant risk factors associated with new-onset POAF in patients undergoing PEA and to evaluate the influence of new-onset POAF on early postoperative outcomes.

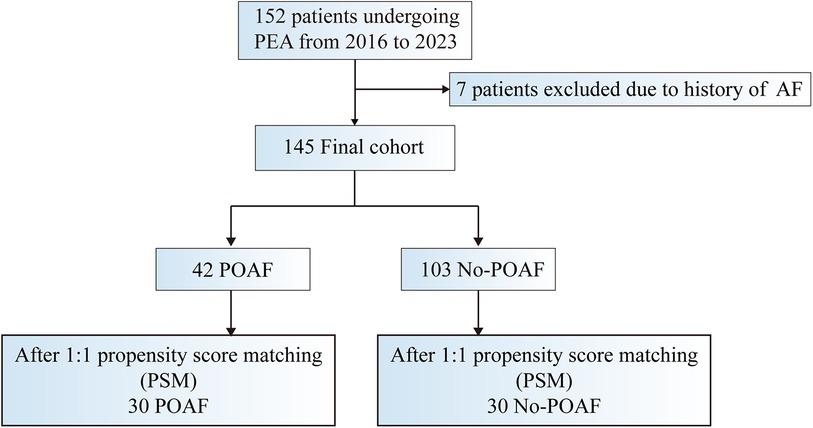

This retrospective, observational cohort study enrolled patients who underwent pulmonary endarterectomy at our hospital between December 2016 and April 2023. Illustrated in Figure 1, a total of 152 patients undergoing PEA were initially included. After excluding 7 patients with a history of paroxysmal or persistent atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter before surgery, the research focused on 145 patients, each confirmed to have sinus rhythm through routine electrocardiogram (ECG) before surgery. Among these, 129 were diagnosed with CTEPH, and 16 were diagnosed with sarcoma. The study adheres to the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the ethics board of the China-Japan Friendship Hospital, waiving the requirement for informed consent as the data were obtained from routine patient care, used for clinical purposes, and handled anonymously.

Figure 1. Study design: summary of inclusion and exclusion criteria. AF indicates atrial fibrillation; POAF postoperative atrial fibrillation; PSM, propensity score matching; and PEA, pulmonary endarterectomy.

All surgeries were conducted by a consistent team of surgeons, utilizing cardiopulmonary bypass with deep hypothermia circulatory arrest. Following the procedure, patients were transitioned to the surgical care unit for subsequent management. Postoperative ECG was obtained from both ECG monitoring and telemetry ECG monitoring. Continuous monitoring of the cardiac rhythm was employed in the ICU ward, utilizing a bedside ECG monitor or telemetry ECG monitor for recording the patient's cardiac rhythm upon transfer to the general ward. Patient data were systematically collected through the electronic medical record system.

Following the definition provided by the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National database (13), new-onset POAF was characterized by the presence of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter persisting for a minimum of 5 min after PEA. Patients maintaining a consistent sinus rhythm were categorized into the sinus rhythm (Non-POAF) group, which was assessed five days post-surgery. Amiodarone was administered to patients experiencing a single episode of atrial fibrillation lasting over 20 min or accumulating a 24-hour duration exceeding 1 h.

The diagnosis of acute heart failure was conducted by a cardiologist who integrated clinical symptoms, signs, and measurements.

Acute kidney insufficiency was characterized by a serum creatinine increase exceeding 1.5 times baseline values, a glomerular filtration rate decrease exceeding 25%, or urine output less than 0.5 ml/kg/h for a duration of 6 h.

The diagnostic criteria for RPE included exudation in chest x-ray, a chest radiograph score greater than 1, a PaO2/FiO2 ratio less than 300 mmHg, and the exclusion of other potential causes such as atelectasis or pneumonia.

A persistent central neurologic deficit (focal or generalized) was diagnosed as stroke, as assessed by 1 neurologist who integrated clinical symptoms, signs, and imaging materials.

Oral anticoagulants are routine treatment for all patients with CTEPH. According to the different mechanisms of the drugs, they were divided into two categories: vitamin K antagonists(VKAs) and direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs).

Continuous variables displaying a normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, while non-normally distributed continuous variables were presented as median (inter-quartile range). Categorical variables were conveyed as the number of cases or percentages. An unpaired t-test or the Mann-Whitney test was employed for continuous variables, and the Chi-square test or Fisher exact test was utilized for comparing categorical variables. Variables with a p-value <0.05 from univariate analysis were chosen for inclusion in binary logistic regression analysis. The Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (ROC) and the Youden index were employed to ascertain optimal cutoff values for continuous variables. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) was used to assess the diagnostic capability of risk factors. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 22.0, IBM Corp.) and R (4.3.1). All tests were two-tailed, and a significance threshold of p < 0.05 was considered.

A total of 42 (29.0%) patients were diagnosed with new-onset POAF in this cohort population. The baseline characteristics of the patients are detailed in Table 1. In comparison with the Non-POAF group, patients in the POAF group were older, exhibited a higher prevalence of hypertension, had shorter distances in the 6-minute walking test (6MWT), demonstrated worse WHO functional class grades, and presented with a larger left atrial diameter (LAD) (Table 1). Intraoperative characteristics of the patients are outlined in Table 2. There were no significant differences observed between patients with and without POAF in intraoperative characteristics (Table 2).

Variables with p < 0.05 (age, hypertension, 6MWT, WHO functional class, LAD) were incorporated into the binary logistic regression model. Age (odds ratio [OR] = 1.041, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.008–1.075, p = 0.014) and LAD (odds ratio [OR] = 1.105, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.025–1.191, p = 0.009) were identified as independent risk factors for new-onset POAF (Table 3).

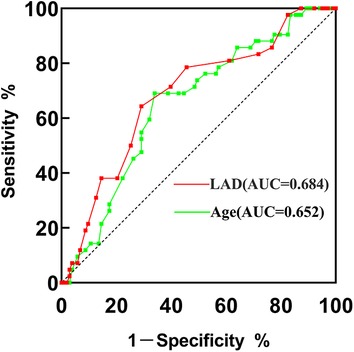

The ROC curves illustrated that the AUC of age and LAD were 0.652 (95% CI = 0.558–0.747, p = 0.004) and 0.684 (95% CI = 0.590–0.779, p = 0.001), respectively (Figure 2). The optimal cutoff point of age was 54.5, with a sensitivity of 69.0% and a specificity of 66.0%. For LAD, the cutoff value was 35.5, with a sensitivity of 64.3%, and specificity of 70.9%.

Figure 2. ROC curve of VWF and age for predicting new-onset POAF after PEA. AUC, area under the curve; PEA, pulmonary endarterectomy; ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

Patients with new-onset POAF exhibited prolonged length of stay, mechanical ventilation, and intensive care unit occupancy. Moreover, they demonstrated elevated in-hospital mortality (23.81% vs. 1.94%, p < 0.001), along with an increased occurrence of complications such as acute kidney injury, reperfusion pulmonary edema, and acute heart failure. The rate for stroke was higher in the POAF group than another group(without POAF), but the difference was not statistically significant (Table 4).

To account for baseline disparities and validate the findings, we conducted propensity score matching (PSM) for 30 patients with POAF and 30 without (Table 5). Even after PSM, the POAF group continued to exhibit an extended duration of mechanical ventilation, elevated in-hospital mortality (26.67% vs. 3.33%, p = 0.030), and a heightened frequency of complications, including acute kidney injury, reperfusion pulmonary edema, and acute heart failure (Table 6).

As the most prevalent arrhythmia following cardiac surgery, new-onset POAF has an incidence ranging from 20% to 50%, often closely linked to adverse outcomes (14, 15). However, evidence for POAF after PEA is insufficient, and previous research lacks definitive standards for POAF. In the Farasat et al. study, POAF was defined as the presence of any atrial arrhythmias based on telemetry findings (11). Conversely, another report recorded various electrocardiography results for patients at 1–6 monthly intervals after PEA, excluding those who developed atrial fibrillation/atrial tachycardia only in the first 30 days post-surgery (12). Our study differs from previous ones as it excluded patients with preoperative atrial arrhythmia, focusing specifically on the new-onset POAF after PEA. Given that POAF typically manifests between days 2 and 4 postoperatively (16), we recorded atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter occurrences five days after surgery as the criterion. In this study, the incidence of new-onset POAF after PEA was 29.0%, aligning closely with the results of previous studies (11, 12, 17).

Advanced age has been consistently identified as an independent risk factor for POAF in numerous clinical studies (18–21). Despite our patient group not surpassing the age of those reported in the cardiac surgery literature, we observed that older age remains a significant risk factor for atrial fibrillation after PEA. The aging process contributes not only to the loss of myocardial fibers but also exacerbates fibrosis and collagen deposition in the atria, particularly near the sinoatrial node, impacting atrial electrical properties (15). These age-related pathophysiological changes constitute fundamental factors in triggering POAF.

Left atrial enlargement is established as another risk factor for the occurrence of new-onset POAF after cardiovascular surgery, as corroborated by numerous prior studies (6, 7). Although pathologic changes in CTEPH primarily affect the right cardiac system, our findings reaffirm that an enlarged LAD is once again identified as a risk factor for POAF. The enlarged atrium induces remodeling of its electrophysiological conduction pathways, resulting in increased irritability of cardiomyocytes, shortened atrial refractory periods, delayed conduction, enhanced extracellular matrix fibrosis, heightened heterogeneity of atrial repolarization, and ultimately promoting the onset of atrial fibrillation.

PEA stands as the exclusive curative option for CTEPH and is recommended for patients suitable for surgical intervention. Nevertheless, it remains a challenging, invasive, and time-intensive procedure, often accompanied by common postoperative complications such as acute heart failure, acute kidney insufficiency, and reperfusion pulmonary edema (22, 23). Consequently, we designated the aforementioned three complications and in-hospital mortality as adverse outcomes. Across both cardiac and non-cardiac surgery, nearly all studies have consistently underscored the association between POAF and adverse outcomes (15–26). POAF is intricately linked to thrombosis, heart failure, stroke, and increased mortality. Our findings also reveal that patients with POAF experience a more adverse prognosis during the early postoperative period. While there was no statistically significant difference in the length of hospital and ICU stays between the two groups after PSM, patients with POAF remained predisposed to developing acute heart failure, acute kidney insufficiency, reperfusion pulmonary edema, and in-hospital mortality compared to the control group. Atrial fibrillation disrupts the hemodynamics, not only escalating the burden on the heart but also severely impairing the pumping function, leading to inadequate perfusion of vital organs such as the kidneys and lungs. Hence, it is unsurprising that corresponding damage ensues. Although our study did not observe the impact of POAF on long-term outcomes in these patients, some research has indicated that POAF also significantly influences postoperative long-term prognosis (27–29). Thus, it is imperative to identify the risk factors of POAF and implement preventive measures accordingly.

Furthermore, patients in the POAF group experienced prolonged mechanical ventilation, even after PSM. Previous studies have indicated that extended ventilation serves as a predictor of POAF (30). This is primarily due to the fact that, on the one hand, patients requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation typically exhibit more severe conditions, compromised cardiopulmonary function, and an increased likelihood of postoperative atrial fibrillation. On the other hand, mechanical ventilation induces alterations in pleural and thoracic pressure, as well as lung capacity, influencing changes in preload, afterload, heart rate, and myocardial contractility. Variations in intrathoracic pressure directly impact the heart, pericardial cavity, major arteries, and veins. Spontaneous breathing generates intrathoracic negative pressure, lowering the pressure in the right atrium. Conversely, intermittent positive pressure ventilation (IPPV) elevates intrathoracic pressure and right atrium pressure, while positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) maintains intrathoracic pressure consistently higher than atmospheric pressure throughout the respiratory cycle. Thus, these factors affecting right atrial pressure may contribute to the onset of POAF. However, acknowledging the bidirectional relationship between mechanical ventilation and atrial fibrillation, we treated mechanical ventilation as a postoperative observation rather than an analytical factor. Nonetheless, PEA is a complex and demanding procedure, often involving extended CPB durations and deep hypothermic circulatory arrest. These factors may induce heightened stress and inflammation, influencing the mechanisms underlying POAF. While previous studies have consistently associated CPB and aortic cross-clamp durations with POAF in cardiac surgery (31, 32), we did not observe a similar outcome in our study.

Some other factors may also trigger the occurrence of POAF. A recent research revealed that Del Nido cardioplegia can significantly reduced POAF rates after coronary artery bypass grafting, compared with cold blood cardioplegia. The occurrence of POAF is associated with electrolyte disorders or “retained blood syndrome”. Some reports indicated that the inotropic drugs could increase the risk of POAF (33, 34). Del Nido cardioplegia have an advantage on the electrolyte balance, myocardial protection and the need for postoperative inotropic support. It's a positive role on the volemic balance result in less occurrence of POAF (35). However, as a single center, our team's practice for PEA, which requires prolonged aortic occlusion, is always to use HTK solution as cardioplegia. Therefore, we can't observe the effect of this factor. In addition, POAF can be triggered also by pericardial effusion. The pericardial effusion stimulates the myocardium and promotes the local inflammatory response, which can lead to POAF. Another recent study found that the posterior pericardial drain can reduce late postoperative pericardial effusion and POAF, compared with the anterior drain, during the first 30 postoperative days (36). To avoid the occurrence of pericardial effusion, we also adopted the the posterior pericardial drain and a mediastinal drainage was placed in the front mediastinum. In addition, we did not suture the pericardium at all, and the pericardium cavity was completely connected to the anterior mediastinum. We only recorded POAF that occurred within postoperative 5 days, no obvious signs of pericardial effusion were found during the period.

Several limitations should be acknowledged in our study. Firstly, the clinical sample size is relatively small, potentially limiting the statistical power of our findings. Subsequent studies with larger sample sizes are warranted to validate our results. Secondly, the propensity score matching process inevitably led to some loss of original data. Lastly, the retrospective study design prevents us from establishing a definitive causal relationship between POAF and adverse outcomes. Consequently, long-term follow-up studies are essential to elucidate whether POAF serves as an indicator or a primary contributor to postoperative adverse outcomes. Although there are some shortcomings in our study, early postoperative hemodynamic stability has an important impact on the recovery of surgical patients supported by extracorporeal circulation, so our findings have certain significance for clinical work.

In summary, our results indicate that advanced age and LAD are independent preoperative risk factors for new-onset POAF after PEA. New-onset POAF after PEA is closely associated with adverse outcomes. Subsequent large-scale studies are necessary to fully explore the role of POAF in the prognosis of PEA.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving humans were approved by the ethics board of the China-Japan Friendship Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because waiving the requirement for informed consent as the data were obtained from routine patient care, used for clinical purposes, and handled anonymously.

DZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Project administration, Software. ZZ: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. YZ: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. XL: Resources, Writing – review & editing. XF: Project administration, Writing – review & editing. ZY: Visualization, Writing – review & editing. PL: Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 82170066, 82270443, 81670275, 81670443) and National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (2022-NHLHCRF-ZSYX-01), the International S&T cooperation program (2013DFA31900).

The authors thank Dr. Zhaohua Zhang for his kind assistance in data analysis. We also thank Dr. Xiaopeng Liu for useful comments and language editing, which have greatly improved the manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Simonneau G, Montani D, Celermajer DS, Denton CP, Gatzoulis MA, Krowka M, et al. Haemodynamic definitions and updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. (2019) 53:1801913. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01913-2018

2. Riedel M, Stanek V, Widimsky J, Prerovsky I. Longterm follow-up of patients with pulmonary thromboembolism. Chest. (1982) 81:151–158. doi: 10.1378/chest.81.2.151

3. Gall H, Hoeper MM, Richter MJ, Cacheris W, Hinzmann B, Mayer E. An epidemiological analysis of the burden of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension in the USA, Europe and Japan. Eur Respir Rev. (2017) 26:160121. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0121-2016

4. Pepke-Zaba J, Delcroix M, Lang I, Mayer E, Jansa P, Ambroz D, et al. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH): results from an international prospective registry. Circulation. (2011) 124:1973–1981. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.015008

5. Hoeper MM, Madani MM, Nakanishi N, Meyer B, Cebotari S, Rubin LJ. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Lancet Respir Med. (2014) 2:573–582. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70089-X

6. Deng L, Quan R, Yang Y, Yang Z, Tian H, Li S, et al. Characteristics and long-term survival of patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension in China. Respirology. (2021) 26:196–203. doi: 10.1111/resp.13947

7. Vistarini N, Morsolini M, Klersy C, Mattiucci G, Grazioli V, Pin M, et al. Pulmonary endarterectomy in the elderly: safety, efficacy and risk factors. J Cardiovasc Med. (2016) 17:144–151. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0000000000000327

8. Nierlich P, Hold A, Ristl R. Outcome after surgical treatment of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: dealing with different patient subsets. A single-centre experience. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. (2016) 50:898–906. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezw099

9. Sakurai Y, Takami Y, Amano K, Higuchi Y, Akita K, Noda M, et al. Predictors of outcomes after surgery for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Ann Thorac Surg. (2019) 108:1154–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2019.03.100

10. Woldendorp K, Farag J, Khadra S, Black D, Robinson B, Bannon P. Postoperative atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: a meta-analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. (2021) 112:2084–2093. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.10.055

11. Farasat S, Papamatheakis DG, Poch DS, Higgins J, Pretorius VG, Madani MM, et al. Atrial arrhythmias after pulmonary thromboendarterectomy. J Card Surg. (2019) 34:312–317. doi: 10.1111/jocs.14028

12. Havranek S, Fingrova Z, Ambroz D, Jansa P, Kuchar J, Dusik M, et al. Atrial fibrillation and atrial tachycardia in patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension treated with pulmonary endarterectomy. Eur Heart J Suppl. (2020) 22:F30–F37. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/suaa096

13. Arakawa M, Miyata H, Uchida N, Motomura N, Katayama A, Tamura K, et al. Postoperative atrial fibrillation after thoracic aortic surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. (2015) 99:103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.08.019

14. Budeus M, Hennersdorf M, Perings S, Röhlen S, Schnitzler S, Felix O, et al. Amiodarone prophylaxis for atrial fibrillation of high-risk patients after coronary bypass grafting: a prospective, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized study. Eur Heart J. (2006) 27:1584–1591. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl082

15. Echahidi N, Pibarot P, O’Hara G, Mathieu P. Mechanisms, prevention, and treatment of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2008) 51:793–801. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.043

16. Gillinov AM, Bagiella E, Moskowitz AJ, Raiten JM, Groh MA, Bowdish ME, et al. Rate control versus rhythm control for atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. (2016) 374:1911–1921. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602002

17. Fernandes TM, Auger WR, Fedullo PF, Kim NH, Poch DS, Madani MM, et al. Baseline body mass index does not significantly affect outcomes after pulmonary thromboendarterectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. (2014) 98:1776–1781. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.06.045

18. Shen J, Lall S, Zheng V, Buckley P, Damiano RJ, Schuessler RB. The persistent problem of new-onset postoperative atrial fibrillation: a single-institution experience over two decades. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2011) 141:559–570. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.03.011

19. Bessissow A, Khan J, Devereaux PJ, Alvarez-Garcia J, Alonso-Coello P. Postoperative atrial fibrillation in non-cardiac and cardiac surgery: an overview. J Thromb Haemost. (2015) 13:S304–S312. doi: 10.1111/jth.12974

20. Greenberg JW, Lancaster TS, Schuessler RB, Melby SJ. Postoperative atrial fibrillation following cardiac surgery: a persistent complication. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. (2017) 52:665–672. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezx039

21. Eikelboom R, Sanjanwala R, Le M-L, Yamashita MH, Arora RC. Postoperative atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. (2021) 111:544–554. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.05.104

22. Ma J, Li C, Zhai Z, Zhen Y, Wang D, Liu M, et al. Distribution of thrombus predicts severe reperfusion pulmonary edema after pulmonary endarterectomy. Asian J Surg. (2023) 46:3766–3772. doi: 10.1016/j.asjsur.2023.03.061

23. Abdelnour-Berchtold E, Donahoe L, McRae K, Asghar U, Thenganatt J, Moric J, et al. Central venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation as a bridge to recovery after pulmonary endarterectomy in patients with decompensated right heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. (2022) 41:773–779. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2022.02.022

24. Gaudino M, Di Franco A, Rong LQ, Piccini J, Mack M. Postoperative atrial fibrillation: from mechanisms to treatment. Eur Heart J. (2023) 44:1020–1039. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad019

25. Goyal P, Kim M, Krishnan U, Mccullough SA, Cheung JW, Kim LK, et al. Post-operative atrial fibrillation and risk of heart failure hospitalization. Eur Heart J. (2022) 43:2971–2980. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac285

26. Lin M-H, Kamel H, Singer DE, Wu Y-L, Lee M, Ovbiagele B. Perioperative/postoperative atrial fibrillation and risk of subsequent stroke and/or mortality: a meta-analysis. Stroke. (2019) 50:1364–1371. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.023921

27. Albini A, Malavasi VL, Vitolo M, Imberti JF, Marietta M, Lip GYH, et al. Long-term outcomes of postoperative atrial fibrillation following non cardiac surgery: a systematic review and metanalysis. Eur J Intern Med. (2021) 85:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2020.12.018

28. Rezk M, Taha A, Nielsen SJ, Martinsson A, Bergfeldt L, Gudbjartsson T, et al. Associations between new-onset postoperative atrial fibrillation and long-term outcome in patients undergoing surgical aortic valve replacement. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. (2023) 63:ezad103. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezad103

29. Zhao R, Wang Z, Cao F, Song J, Fan S, Qiu J, et al. New-onset postoperative atrial fibrillation after total arch repair is associated with increased in-hospital mortality. J Am Heart Assoc. (2021) 10:e021980. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.021980

30. Erdil N, Gedik E, Donmez K, Erdil F, Aldemir M, Battaloglu B, et al. Predictors of postoperative atrial fibrillation after on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting: is duration of mechanical ventilation time a risk factor? Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2014) 20:135–142. doi: 10.5761/atcs.oa.12.02104

31. Villareal RP, Hariharan R, Liu BC, Kar B, Lee V-V, Elayda M, et al. Postoperative atrial fibrillation and mortality after coronary artery bypass surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2004) 43:742–748. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.11.023

32. Mathew JP, Parks R, Savino JS, Friedman AS, Koch C, Mangano DT, et al. Atrial fibrillation following coronary artery bypass graft surgery. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03540040044031

33. Raiten JM, Ghadimi K, Augoustides JGT, Ramakrishna H, Patel PA, Weiss SJ, et al. Atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: clinical update on mechanisms and prophylactic strategies. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. (2015) 29:806–816. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2015.01.001

34. Yadava M, Hughey AB, Crawford TC. Postoperative atrial fibrillation. Heart Fail Clin. (2016) 12:299–308. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2015.08.023

35. Comentale G, Parisi V, Fontana V, Manzo R, Conte M, Nunziata A, et al. The role of Del Nido cardioplegia in reducing postoperative atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery in patients with impaired cardiac function. Heart Lung. (2023) 60:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2023.03.003

Keywords: postoperative atrial fibrillation (POAF), risk factors, adverse outcomes, chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH), pulmonary thromboendarterectomy (PEA)

Citation: Zhang D, Zhang Z, Zhen Y, Liu X, Fan X, Ye Z and Liu P (2024) New-onset postoperative atrial fibrillation after pulmonary endarterectomy is associated with adverse outcomes. Front. Surg. 11:1380570. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2024.1380570

Received: 1 February 2024; Accepted: 10 May 2024;

Published: 30 May 2024.

Edited by:

Yousef Shahin, The University of Sheffield, United KingdomReviewed by:

Giuseppe Comentale, University of Naples Federico II, Italy© 2024 Zhang, Zhang, Zhen, Liu, Fan, Ye and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Peng Liu, bGl1cGVuZzAxNTdAdmlwLjEyNi5jb20=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.