- 1Department of Surgery, Ordensklinikum Linz, Linz, Austria

- 2VYRAL, Linz, Austria

- 3Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, Ordensklinikum Linz, Linz, Austria

- 4Medical Faculty, Johannes Kepler University, Linz, Austria

Introduction: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) represents one of the most commonly performed routine abdominal surgeries. Nevertheless, besides bile duct injury, problems caused by lost gallstones represent a heavily underestimated and underreported possible late complication after LC.

Methods: Case report of a Clavien-Dindo IVb complication after supposedly straightforward LC and review of all published case reports on complications from lost gallstones from 2000-2022.

Case Report: An 86-year-old patient developed a perihepatic abscess due to lost gallstones 6 months after LC. The patient had to undergo open surgery to successfully drain the abscess. Reactive pleural effusion needed additional drainage. Postoperative ICU stay was 13 days. The patient was finally discharged after 33 days on a geriatric remobilization ward and died 12 months later due to acute cardiac decompensation.

Conclusion: Intraabdominal abscess formation due to spilled gallstones may present years after LC as a late complication. Surgical management in order to completely evacuate the abscess and remove all spilled gallstones may be required, which could be associated with high morbidity and mortality, especially in elderly patients. Regarding the overt underreporting of gallstone spillage in case of postoperative gallstone-related complications, focus need be put on precise reporting of even apparently innocuous complications during LC.

1 Introduction

Gallstone disease affects up to 20% of the European population. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is indicated in patients with symptomatic gallstones, acute cholecystitis or biliary sludge and represents one of the most commonly performed abdominal surgeries (1).

Perforation of the gallbladder is relatively common in LC and is reported in various studies to range between 10% to 40% of procedures. Gallstone spillage is less common, and the true frequency of unremoved stones is difficult to determine. Some case series indicate a range of 6% to 30% (2). Incidence increases if the surgery is performed for acute cholecystitis. Other risk factors include male sex, higher age, obesity and the presence of postoperative adhesions. Complications resulting from these spilled stones are reported to occur in 0.08% to 0.3% of patients, and most of these lost stones remain clinically silent (2).

However, even if dropped gallstones do not cause actual postoperative harm through complications, they often are not correctly identified by imaging and can be mistaken for peritoneal lesions leading to unnecessary concern. Nevertheless, a small percentage of dropped gallstones cause actual complications of immediate or delayed (even months after surgery) clinical concern, such as abscesses and fistulas (3).

Some reports show that only half of the surgeons inform the patient when gallstones are lost during operation, less than 30% inform the general practitioner about this complication and less than a quarter of surgeons informed about this complication in the consent form handed to the patient preoperatively (4). Another part of the problem is the differentiation between intraoperative iatrogenic gallbladder perforation, spillage of gallstones, retrieved and lost gallstones. Underreporting of intraoperative gallbladder perforation is common and it is almost impossible to determine the exact number of spilled gallstones. Despite examination and rinsing, it may be impossible to assure, that all gallstones spilled into the abdomen are really retrieved.

We report a case of an elderly patient presenting with a symptomatic perihepatic abscess 6 months after LC.

2 Case report

An 86-year-old male patient presented in our surgical ward 6 months after presumed, uncomplicated laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed in May 2022 due to necrotizing cholecystitis with 15 kg of weight loss, anorexia and rapid feeling of fullness since the operation. The patient denied pain or fever. Upon physical examination, the patient reported diffuse abdominal discomfort. The abdomen was described as soft with mild tenderness in the right upper abdomen. Blood tests revealed elevated C-reactive protein and white blood count. His past medical history was significant for severe tricuspid valve insufficiency, atrial fibrillation, type 2 diabetes mellitus and arterial hypertension.

Computed tomography scan (CT, Figure 1) revealed a perihepatic abscess (5.5 × 5.8 cm) with suspected connection to the pleural space and small calcareous structures. Diagnostic laparoscopy was performed. Due to a soft, vulnerable liver, small liver injuries and bleeding, open surgery was necessary to successfully and safely drain the abscess. Upon evacuation, lost gallstones were discovered and removed. Further, the diaphragm was eroded by the chronic inflammation, but the parietal pleura was intact. Follow-up x-rays revealed an increasing pleural effusion, which was considered reactive. Therefore, the placement of a chest tube in the 5th intercostal space at the midaxillary line was additionally needed and was left for 4 days. Empirical intravenous antibiotic therapy with piperacillin + tazobactam 4,000 mg/500 mg twice a day for 3 days was initiated and then switched to meropenem as a single 1,000 mg dose once every 24 h due to increasing C-reactive protein. Antibiotics were de-escalated to cefuroxime 750 mg once a day after 4 days according to the antibiogram of the detected Escherichia coli isolated from the intraoperative swab. This antibiotic regimen was followed for another 6 days.

Figure 1. Computed tomography (CT) scan and intraoperative shot of the subhepatic abscess. (A) Macroscopic intraoperative image of the subhepatic abscess. (B,C) Subhepatic abscess in transverse and sagittal sections in CT scan, the lost gallstones are marked. (D) Subhepatic abscess in coronal section in CT scan, perforated diaphragm, right-sided pleural effusion, the lost gallstones are marked.

Postoperative ICU stay was 13 days. Reintubation was necessary due to cardiac decompensation with pulmonary edema. In addition, acute to chronic kidney failure developed with need for hemodiafiltration. Cardiac recompensation was achieved using Levosimendan and Landiolol.

The patient was finally discharged after additional 33 days on a geriatric remobilization ward, where his autonomous ability and everyday skills were restored. However, chronic kidney failure with need for hemodialysis persisted. The patient died 12 months after being discharged due to acute cardiac decompensation.

3 Discussion

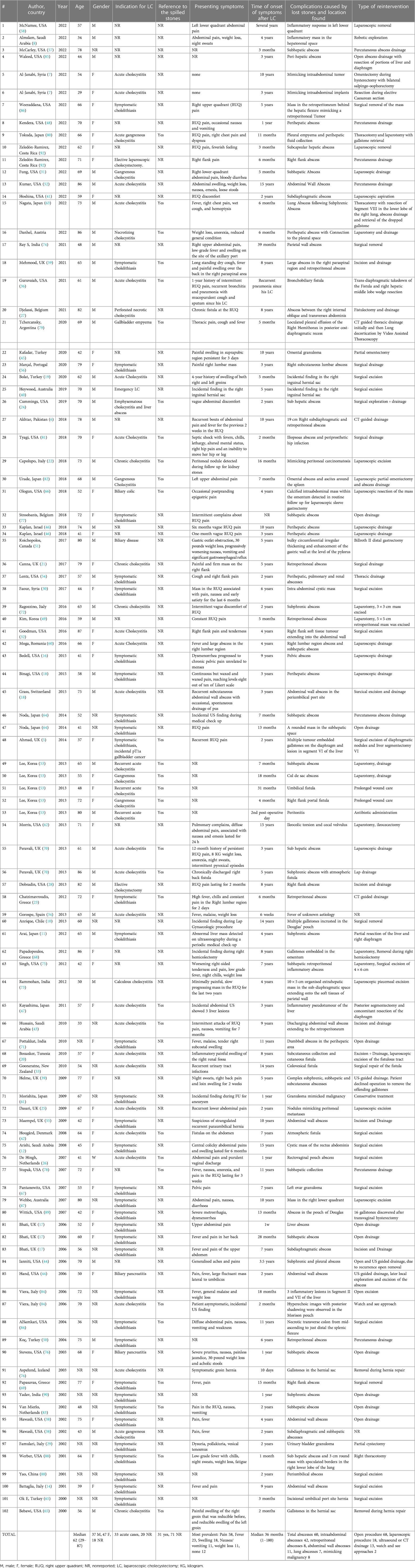

Review of the literature resulted in 211 articles, and 89 records with 102 patients (5–92) were included in the analysis (Table 1). The median age was 62 years (IQR 29–87). However, age was not reported in 6 articles. In total, there were 37 (44%) male and 47 (56%) female patients. Gender could not be determined in 18 articles. Of all 102 reports, LC was performed as emergency procedure in 33 cases (32%) (7, 13, 19, 20, 24–27, 31–36, 38, 40, 42, 43, 47, 52, 53, 60, 63, 70, 73, 79–82, 84). In 20 articles, the indication for LC was not reported. Of all 102 case reports with lost gallstones, gallstone spillage had only been recorded by the surgeon in the surgical report in 31 cases (30%). The most commonly reported symptoms of symptomatic spilled gallstones were pain (n = 58, 56.8%), fever (n = 23, 22.5%), abdominal swelling (n = 18, 17.6%), weight loss (n = 11, 10.7%) and nausea or vomiting (n = 11, 10.7%). Other symptoms were fistulation (such as bronchobiliary, colovesical or atmospheric fistulas), night sweats, changes in stool, malaise, chills, gynecological complaints and also respiratory problems such as cough, hemoptysis or dyspnoea. Furthermore, pruritus, painless jaundice, urinary tract infection or gastrointestinal reflux have been described in individual cases. In 12 patients, lost gallstones were discovered as an incidental finding in asymptomatic patients (7, 10, 11, 19, 22, 40, 47, 61, 64, 68, 84). No symptoms were reported in 11 patients. Symptom onset was reported at a median of 36 months after surgery and ranged between 1 and 180 months. Postoperative abscesses caused by spilled gallstones were reported in 60/102 (58.8%) patients. Of these, 41.1% (n = 42) were intra-abdominal abscesses, 10.7% (n = 11) abdominal wall abscesses, 7.8% (n = 8) retroperitoneal abscesses and 6.8% (n = 7) lung abscesses. In 8 (7.8%) cases the lost gallstones mimicked malignancy. Lost gallstones may either mimic peritoneal carcinomatosis or the presence of a primary tumor, leading to excision (7, 22, 25, 32, 61, 84, 86). Remarkable 66.6% (n = 68) of the patients required open surgical procedures, 17.6% (n = 18) laparoscopic revisions and 12.7% (n = 13) were treated with ultrasound or CT guided drainage. Only 2 (1.9%) patients were successfully treated conservatively (53, 61).

We aimed to conduct a census of all cases with complications from lost gallstones after laparoscopic cholecystectomy from 2000 to 2022 reported in the literature. The results should clarify that late complications from spilled gallstones are rare (0.08% to 0.3% of patients) but can cause severe problems that occur at a median of 36 months after the initial operation. However, it should be taken into consideration, that the published literature mainly covers incidental findings and small case series.

Of note, only 32% of reported cases initially had acute cholecystitis, while in the majority of cases, primary LC had been reported as elective procedure for symptomatic gallstone disease. Concerning a concept of a culture of safe cholecystectomy, surgeons should be facile with the following aspects: Knowledge of relevant anatomy, various anatomical landmarks, and anatomical variations; correct gallbladder retraction; safe use of energy devices; knowledge of the critical view of safety (including its documentation); awareness of various bailout procedures (e.g., cholecystectomy by the fundus-first approach) in difficult gallbladder cases; use of intraoperative imaging techniques (e.g., intraoperative cholangiogram) at uncertain anatomy; respecting the concept of time-out and thorough documentation (93).

It is also alarming that iatrogenic peroration of the gallbladder was only described in 30% of cases causing postoperative complications, suggesting a much higher number of actual gallbladder perforations during LC. Literature on incidental gallstone spillage may be biased by distinct underreporting, considering that only a minority of surgeons document gallbladder perforation and gallstone spillage. Mullerat et al. reported that only half of the surgeons informed their patients and less than 30% informed the general practitioner if gallstones were lost during surgery. The supposed low importance of these complications is underlined by the fact that only a quarter of the surgeons mention this complication in the surgical explanation (4). Operative difficulty is classified according to Nassar Grade and was found to be a significant independent predictor of 30-day complications and 30-day reinterventions. The score could be used to unify the severity of the disease and the technical difficulty of the operation and can be implemented as a tool to document operative findings. Therefore, it can be used in future research to compare outcome and intraoperative difficulties (94).

Since almost 60% of all complications are abscesses, predominant symptoms are fever, pain, abdominal swelling, weight loss, nausea or vomiting. This should lead to radiological cross-sectional imaging in acute diagnostics, which should quickly lead to the correct diagnosis.

The formation of an abscess can be life-threatening. The percutaneous placement of a drain or catheter under imaging control is an increasingly used medical procedure. It is an effective and safe alternative to surgery, reducing discomfort and hospitalization. An amazing 66.6% of the cases required an open procedure and only 12.7% of the patients could be treated with percutaneous drainage (95). Apparently retained gallstones are a problem for percutaneous techniques, because the removal of stones is complex or even impossible. Variations in the location of retained stones, clinical symptoms and individual risk factors of patients demand a personal treatment strategy. However, minimal invasive techniques should be applied, whenever appropriate. Thus, it remains questionable whether a standardized procedure can be found for this complication. In particular, confusion with peritoneal masses can have severe consequences. Complex symptoms such as gastrointestinal reflux, urinary tract infections or breathing problems may lead to a diagnostic dilemma.

4 Limitations

A collection of case reports has several limitations. As Gavriilidis et al. described, institutional, national, underpowered sample size, learning curve, performance and follow-up bias may have influenced the results. In addition, case reports with a poor outcome, unusual history of the disease and rare complications are more commonly reported in the literature, than those with an uncomplicated course (96).

One way to prevent these biases could be the implementation of international databases that record all complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy postoperatively and in the follow-up. Therefore, awareness of this complication must be created. Futhermore, there is still a lack of a standardized procedure at the international level for laparoscopic operations for gallbladder diseases. Therefore, the Global Evaluation of Cholecystectomy Knowledge and Outcomes (GECKO) study (GlobalSurg 4) will be an international collaborative initiative that will allow contemporaneous data collection on the quality of cholecystectomies. GECKO is a prospective, international, multicentre cohort study observing patients undergoing cholecystectomy, between 31st July 2023 to 19th November 2023, with follow-up at 30-day and one-year postoperatively. The aim of this study is to define the global variation in compliance to pre-, intra-, and post-operative audit standards including: Interventional radiology service; risk stratification via Tokyo Guidelines 18; timing of surgery; achieving a critical view of safety; intraoperative imaging; initiating different bailout procedures; antibiotic use; use of drains; bile duct injury; 30-day readmission; and critical care (97).

5 Conclusion

This case report and review of the literature shall emphasize the alertness on exact reporting of complications to patients and attending doctors by exact documentation in operating reports, to think of that late complication after LC when the symptoms described above are present, and is simply intended to create general awareness, since many surgeons are probably not aware of the problem. Radiologists may suspect unclear radiopaque concretions in the CT scan as lost gallstones after LC in order to identify the abscess genesis earlier. It should be avoided that lost stones will not be considered in patients with above presented symptoms, as there is not a single note in the operation report about them being spilled.

Surgical management in order to completely evacuate the abscess and remove all spilled gallstones should be the attempted. Generally, laparoscopic approaches must be preferred for accessible abscess collection. However, percutaneous drainage could be considered as bridge to surgery or for patients unfit for surgery. Nevertheless, attempting to treat intra-abdominal abscesses containing spilled gallstones with percutaneous drainage will always bear the risk of incomplete treatment by leaving stones in the abdomen. If gallstones spill intraoperatively during laparoscopic cholecystectomy, all stones should be recovered and copious peritoneal lavage should be performed. The initial administration of antibiotics seems to be of secondary importance, as it seems most important to eliminate the mechanical trigger.

To sum up, most lost gallstones remain clinically silent, but they may cause complications that can become symptomatic after years from surgery. In patients with unexplained abdominal abscess or fistula with a history of cholecystectomy within the last 10 years, lost gallstones should always be considered.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

LD: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration. AF: Investigation, Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing. LH: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. TK: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. PP: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. AP: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. DR: Investigation, Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing. ST: Project administration, Software, Writing – review & editing. MW: Visualization, Writing – review & editing. RF: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. MB: Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. PK: Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research or authorship of this article.

The author(s) further declare that financial support was received for the publication of this article. This work was supported by Johannes Kepler University Open Access Publishing Fund.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Gutt C, Schlafer S, Lammert F. The treatment of gallstone disease. Dtsch Arztebl Int. (2020) 117(9):148–58. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2020.0148

2. Sathesh-Kumar T, Saklani AP, Vinayagam R, Blackett RL. Spilled gall stones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a review of the literature. Postgrad Med J. (2004) 80(940):77–9. doi: 10.1136/pmj.2003.006023

3. Nayak L, Menias CO, Gayer G. Dropped gallstones: spectrum of imaging findings, complications and diagnostic pitfalls. Br J Radiol. (2013) 86(1028):20120588. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20120588

4. Mullerat J, Cooper K, Box B, Soin B. The case for standardisation of the management of gallstones spilled and not retrieved at laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. (2008) 90(4):310–2. doi: 10.1308/003588408X285883

5. Ahmad J, Mayne AI, Zen Y, Loughrey MB, Kelly P, Taylor M. Spilled gallstones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. (2014) 96(5):e18–20. doi: 10.1308/003588414X13946184900444

6. Akhtar A, Bukhari MM, Tariq U, Sheikh AB, Siddiqui FS, Sohail MS, et al. Spilled gallstones silent for a decade: a case report and review of literature. Cureus. (2018) 10(7):e2921. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2921

7. Al-Janabi MH, Aslan RG, Hasan AM, Doarah M, Daoud R, Wassouf A, et al. Dropped gallstones mimicking intraabdominal implants or tumor: a report of two cases. Ann Med Surg (Lond). (2022) 81:104557. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2022.104557

8. Almslam MS, Alshehri AI, Alshehri AA, Peedikayil MC, Alkahtani KM. Intra-abdominal spilled gallstones mimicking malignancy: a case report and a literature review. Cureus. (2022) 14(12):e32376. doi: 10.7759/cureus.32376

9. AlSamkari R, Hassan M. Middle colic artery thrombosis as a result of retained intraperitoneal gallstone after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. (2004) 14(2):85–6. doi: 10.1097/00129689-200404000-00007

10. Anrique D, Kroker A, Ebert AD. “Blueberry sign”: spilled gallstones after cholecystectomy as an uncommon finding. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. (2013) 20(3):329. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2012.11.011

11. Arai T, Ikeno T, Miyamoto H. Spilled gallstones mimicking a liver tumor. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2012) 10(11):A32. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.06.026

12. Arishi AR, Rabie ME, Khan MS, Sumaili H, Shaabi H, Michael NT, et al. Spilled gallstones: the source of an enigma. JSLS. (2008) 12(3):321–5.18765063

13. Aspelund G, Halldorsdottir BA, Isaksson HJ, Moller PH. Gallstone in a hernia sac. Surg Endosc. (2003) 17(4):657. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-4257-7

14. Battaglia DM, Fornasier VL, Mamazza J. Gallstone in abdominal wall–a complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. (2001) 11(1):50–2.11269557

15. Bebawi M, Wassef S, Ramcharan A, Bapat K. Incarcerated indirect inguinal hernia: a complication of spilled gallstones. JSLS. (2000) 4(3):267–9.10987409

16. Bedell SL, Kho KA. Spilled gallstones after laparoscopic cholecystectomy associated with pelvic pain. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (2015) 213(3):432 e 1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.04.020

17. Bhati CS, Tamijmarane A, Bramhall SR. A tale of three spilled gall stones: one liver mass and two abscesses. Dig Surg. (2006) 23(3):198–200. doi: 10.1159/000094739

18. Binagi S, Keune J, Awad M. Immediate postoperative pain: an atypical presentation of dropped gallstones after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Case Rep Surg. (2015) 2015:930450. doi: 10.1155/2015/930450

19. Bolat H, Teke Z. Spilled gallstones found incidentally in a direct inguinal hernia sac: report of a case. Int J Surg Case Rep. (2020) 66:218–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2019.12.018

20. Bouasker I, Zoghlami A, El Ouaer MA, Khalfallah M, Samaali I, Dziri C. Parietal abscess revealing a lost gallstone 8 years after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Tunis Med. (2010) 88(4):277–9.20446264

21. Canna A, Adaba F, Sezen E, Bissett A, Finch GJ, Ihedioha U. Para-spinal abscess following gallstones spillage during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: an unusual presentation. J Surg Case Rep. (2017) 2017(3):r j x 052. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjx052

22. Capolupo GT, Masciana G, Carannante F, Caricato M. Spilled gallstones simulating peritoneal carcinomatosis: a case report and literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. (2018) 48:113–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2018.04.016

23. Chatzimavroudis G, Atmatzidis S, Papaziogas B, Galanis I, Koutelidakis I, Doulias T, et al. Retroperitoneal abscess formation as a result of spilled gallstones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: an unusual case report. Case Rep Surg. (2012) 2012:573092. doi: 10.1155/2012/573092

24. Cummings K, Khoo T, Pal T, Psevdos G. Recurrence of Citrobacter koseri-associated intra-abdominal infection 2 years after spilled gallstones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Glob Infect Dis. (2019) 11(1):47–9. doi: 10.4103/jgid.jgid_9_18

25. Dasari BV, Loan W, Carey DP. Spilled gallstones mimicking peritoneal metastases. JSLS. (2009) 13(1):73–6.19366546

26. de Hingh IH, Gouma DJ. Diagnostic image (345). A woman with abdominal pain and purulent vaginal discharge. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. (2007) 151(41):2271.17987895

27. Djelassi S, Vandenbroucke F, Schoneveld M. A curious case of recurrent abdominal wall infections. J Belg Soc Radiol. (2021) 105(1):12. doi: 10.5334/jbsr.2387

28. Dobradin A, Jugmohan S, Dabul L. Gallstone-related abdominal abscess 8 years after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. JSLS. (2013) 17(1):139–42. doi: 10.4293/108680812X13517013317518

29. Famulari C, Pirrone G, Macri A, Crescenti F, Scuderi G, De Caridi G, et al. The vesical granuloma: rare and late complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. (2001) 11(6):368–71. doi: 10.1097/00129689-200112000-00006

30. Faour R, Sultan D, Houry R, Faour M, Ghazal A. Gallstone-related abdominal cystic mass presenting 6 years after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. (2017) 32:70–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2017.01.059

31. Fung BM, Sugumar A, Pan JJ. A dropped gallstone leading to abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2022) 20(5):e918. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.09.015

32. Goodman LF, Bateni CP, Bishop JW, Canter RJ. Delayed phlegmon with gallstone fragments masquerading as soft tissue sarcoma. J Surg Case Rep. (2016) 2016(6). doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjw106

33. Gooneratne DL. A rare late complication of spilled gallstones. N Z Med J. (2010) 123(1318):62–6.20651868

34. Gorospe L. Intraperitoneal spilled gallstones presenting as fever of unknown origin after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: fDG PET/CT findings. Clin Nucl Med. (2012) 37(8):819–20. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e31824c6042

35. Grass F, Fournier I, Bettschart V. Abdominal wall abscess after cholecystectomy. BMC Res Notes. (2015) 8:334. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1303-9

36. Guruvaiah N, Ponnatapura J. Bronchobiliary fistula: a rare postoperative complication of spilled gallstones from laparoscopic cholecystectomy. BMJ Case Rep. (2021) 14(7). doi: 10.1136/bcr-2021-243198

37. Hand AA, Self ML, Dunn E. Abdominal wall abscess formation two years after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. JSLS. (2006) 10(1):105–7.16709372

38. Hawasli A, Schroder D, Rizzo J, Thusay M, Takach TJ, Thao U, et al. Remote complications of spilled gallstones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: causes, prevention, and management. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. (2002) 12(2):123–8. doi: 10.1089/10926420252939664

39. Helme S, Samdani T, Sinha P. Complications of spilled gallstones following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a case report and literature overview. J Med Case Rep. (2009) 3:8626. doi: 10.4076/1752-1947-3-8626

40. Heywood S, Wagstaff B, Tait N. An unusual site of gallstones five years after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Int J Surg Case Rep. (2019) 56:107–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2019.02.038

41. Hoshina Y, Miro P. Perihepatic fluid collection with mobile echogenic foci. Clin Case Rep. (2022) 10(1):e05291. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.5291

42. Hougard K, Bergenfeldt M. Abdominal fistula 7 years after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ugeskr Laeger. (2008) 170(36):2803.18761878

43. Hussain MI, Al-Akeely MH, Alam MK, Al-Abood FM. Abdominal wall abscess following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: an unusual late complication of lost gallstones. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. (2010) 20(11):763–5.21078253

44. Iannitti DA, Varker KA, Zaydfudim V, McKee J. Subphrenic and pleural abscess due to spilled gallstones. JSLS. (2006) 10(1):101–4.16709371

45. Kafadar MT, Cetinkaya I, Aday U, Basol O, Bilge H. Acute abdomen due to spilled gallstones: a diagnostic dilemma 10 years after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Surg Case Rep. (2020) 2020(8):rjaa 275. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjaa275

46. Kaplan U, Shpoliansky G, Abu Hatoum O, Kimmel B, Kopelman D. The lost stone—laparoscopic exploration of abscess cavity and retrieval of lost gallstone post cholecystectomy: a case series and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. (2018) 53:43–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2018.10.020

47. Kayashima H, Ikegami T, Ueo H, Tsubokawa N, Matsuura H, Okamoto D, et al. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver in association with spilled gallstones 3 years after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: report of a case. Asian J Endosc Surg. (2011) 4(4):181–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-5910.2011.00094.x

48. Kendera W, Shroff N, Al-Jabbari E, Barghash M, Bagherpour A, Bhargava P. “Target sign” from dropped gallstones after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Radiol Case Rep. (2022) 17(1):23–6. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2021.09.070

49. Kim BS, Joo SH, Kim HC. Spilled gallstones mimicking a retroperitoneal sarcoma following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. World J Gastroenterol. (2016) 22(17):4421–6. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i17.4421

50. Koc E, Suher M, Oztugut SU, Ensari C, Karakurt M, Ozlem N. Retroperitoneal abscess as a late complication following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Med Sci Monit. (2004) 10(6):CS27–9.15173674

51. Koichopolos J, Hamidi M, Cecchini M, Leslie K. Gastric outlet obstruction by a lost gallstone: case report and literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. (2017) 41:128–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2017.10.014

52. Kumar K, Haas CJ. Dropped gallstone presenting as recurrent abdominal wall abscess. Radiol Case Rep. (2022) 17(6):2001–5. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2022.03.044

53. Lee W, Kwon J. Fate of lost gallstones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Korean J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. (2013) 17(2):66–9. doi: 10.14701/kjhbps.2013.17.2.66

54. Lentz J, Tobar MA, Canders CP. Perihepatic, pulmonary, and renal abscesses due to spilled gallstones. J Emerg Med. (2017) 52(5):e183–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.12.016

55. Maempel J, Darmanin G, Paice A, Uzkalnis A. An unusual “hernia”: losing a stone is not always a good thing!. BMJ Case Rep. (2009) 2009. doi: 10.1136/bcr.12.2008.1321

56. Marcal A, Pereira RV, Monteiro A, Dias J, Oliveira A, Pinto-de-Sousa J. Right lumbar abscess containing a gallstone-an unexpected late complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Surg Case Rep. (2020) 2020(7):rjaa248. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjaa248

57. McCarley S, Yu B, Guay R, Ong A, Sacks D, Butts CA. Percutaneous retrieval of retained gallstones. Am Surg. (2022) 89:31348221084944. doi: 10.1177/00031348221084944

58. McNamee M, Chambers JG. Spilled gallstones presenting as left lower quadant abdominal pain consistent with diverticulitis. Am Surg. (2022) 88(7):1530–1. doi: 10.1177/00031348221080422

59. Mehmood S, Singh S, Igwe C, Obasi CO, Thomas RL. Gallstone extraction from a back abscess resulting from spilled gallstones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a case report. J Surg Case Rep. (2021) 2021(7):r j a b 293. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjab293

60. Moga D, Perisanu S, Popentiu A, Sora D, Magdu H. Right retroperitoneal and subhepatic abscess; late complications due to spilled stones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy—case report. Chirurgia (Bucur). (2016) 111(1):67–70.26988543

61. Morishita K, Otomo Y, Sasaki H, Yamashiro T, Okubo K. Multiple abdominal granuloma caused by spilled gallstones with imaging findings that mimic malignancy. Am J Surg. (2010) 199(2):e23–4. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.04.016

62. Morris MW J, Barker AK, Harrison JM, Anderson AJ, Vanderlan WB. Cicatrical cecal volvulus following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. JSLS. (2013) 17(2):333–7. doi: 10.4293/108680813X13654754534314

63. Nagata K, Fujikawa T, Oka S, Osaki T. A case of intractable lung abscess following dropped gallstone-induced subphrenic abscess: a rare postoperative complication caused by dropped gallstone during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Cureus. (2022) 14(7):e27491. doi: 10.7759/cureus.27491

64. Noda Y, Kanematsu M, Goshima S, Kondo H, Watanabe H, Kawada H, et al. Peritoneal chronic inflammatory mass formation due to gallstones lost during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Clin Imaging. (2014) 38(5):758–61. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2014.03.011

65. Ok E, Sozuer E. Intra-abdominal gallstone spillage detected during umbilical trocar site hernia repair after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: report of a case. Surg Today. (2000) 30(11):1046–8. doi: 10.1007/s005950070032

66. Ologun GO, Lovely R, Sultany M, Aman M. Retained gallstone presenting as large intra-abdominal mass four years after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Cureus. (2018) 10(1):e2030. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2030

67. Pantanowitz L, Prefontaine M, Hunt JP. Cholelithiasis of the ovary after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a case report. J Reprod Med. (2007) 52(10):968–70.17977178

68. Papadopoulos IN, Christodoulou S, Economopoulos N. Asymptomatic omental granuloma following spillage of gallstones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy protects patients and influences surgeons’ decisions: a review. BMJ Case Rep. (2012) 2012. doi: 10.1136/bcr.10.2011.4980

69. Papasavas PK, Caushaj PF, Gagne DJ. Spilled gallstones after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. (2002) 12(5):383–6. doi: 10.1089/109264202320884144

70. Peravali R, Harris A. Laparoscopic management of chronic abscess due to spilled gallstones. JSLS. (2013) 17(4):657–60. doi: 10.4293/108680813X13654754535313

71. Pottakkat B, Sundaram M, Singh P. Abdominal wall abscess due to spilled gallstone presenting 11 years after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Clin J Gastroenterol. (2010) 3(6):324–6. doi: 10.1007/s12328-010-0180-y

72. Ragozzino A, Puglia M, Romano F, Imbriaco M. Intra-Hepatic spillage of gallstones as a late complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy: mR imaging findings. Pol J Radiol. (2016) 81:322–4. doi: 10.12659/PJR.896497

73. Rammohan A, Srinivasan UP, Jeswanth S, Ravichandran P. Inflammatory pseudotumour secondary to spilled intra-abdominal gallstones. Int J Surg Case Rep. (2012) 3(7):305–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2012.03.013

74. Ray S, Kumar D, Garai D, Khamrui S. Dropped gallstone-related right subhepatic and parietal wall abscess: a rare complication after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. ACG Case Rep J. (2021) 8(5):e00579. doi: 10.14309/crj.0000000000000579

75. Singh K, Wang ML, Ofori E, Widmann W, Alemi A, Nakaska M. Gallstone abscess as a result of dropped gallstones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Int J Surg Case Rep. (2012) 3(12):611–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2012.07.017

76. Stevens S, Rivas H, Cacchione RN, O'Rourke NA, Allen JW. Jaundice due to extrabiliary gallstones. JSLS. (2003) 7(3):277–9.14558721

77. Stroobants E, Cools P, Somville F. Case report: an unwanted leftover after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Acta Chir Belg. (2018) 118(3):196–8. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2017.1346035

78. Stupak D, Cohen S, Kasmin F, Lee Y, Siegel JH. Intra-abdominal actinomycosis 11 years after spilled gallstones at the time of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. (2007) 17(6):542–4. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3181469069

79. Tchercansky AN, Fernandez Alberti J, Panzardi N, Auvieux R, Buero A. Thoracic empyema after gallstone spillage in times of COVID. Int J Surg Case Rep. (2020) 76:221–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2020.09.181

80. Tokuda A, Maehira H, Iida H, Mori H, Nitta N, Maekawa T, et al. Pleural empyema caused by dropped gallstones after laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: a case report. Surg Case Rep. (2022) 8(1):62. doi: 10.1186/s40792-022-01419-4

81. Tyagi V, Wiznia DH, Wyllie AK, Keggi KJ. Total hip lithiasis: a rare sequelae of spilled gallstones. Case Rep Orthop. (2018) 2018:9706065. doi: 10.1155/2018/9706065

82. Urade T, Sawa H, Murata K, Mii Y, Iwatani Y, Futai R, et al. Omental abscess due to a spilled gallstone after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Clin J Gastroenterol. (2018) 11(5):433–6. doi: 10.1007/s12328-018-0853-5

83. Van Mierlo PJ, De Boer SY, Van Dissel JT, Arend SM. Recurrent staphylococcal bacteraemia and subhepatic abscess associated with gallstones spilled during laparoscopic cholecystectomy two years earlier. Neth J Med. (2002) 60(4):177–80.12164397

84. Viera FT, Armellini E, Rosa L, Ravetta V, Alessiani M, Dionigi P, et al. Abdominal spilled stones: ultrasound findings. Abdom Imaging. (2006) 31(5):564–7. doi: 10.1007/s00261-005-0241-8

85. Waleed M, Hassaan Arif Maan M, Soban Arif Maan M, Arsalan Arshad M. Non-resolving perihepatic abscess following spilled gallstones requiring surgical management. S D Med. (2022) 75(3):120–2.35708577

86. Weeraddana P, Weerasooriya N, Thomas T, Fiorito J. Dropped gallstone mimicking retroperitoneal tumor 5 years after laparoscopic cholecystectomy posing a diagnostic challenge. Cureus. (2022) 14(11):e31284. doi: 10.7759/cureus.31284

87. Wehbe E, Voboril RJ, Brumfield EJ. A spilled gallstone. Med J Aust. (2007) 187(7):397. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01310.x

88. Werber YB, Wright CD. Massive hemoptysis from a lung abscess due to retained gallstones. Ann Thorac Surg. (2001) 72(1):278–9. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(00)02563-7

89. Wittich AC. Spilt gallstones removed after one year through a colpotomy incision: report of a case. Int Surg. (2007) 92(1):17–9.17390909

90. Yadav RK, Yadav VS, Garg P, Yadav SP, Goel V. Gallstone expectoration following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. (2002) 44(2):133–5. doi: 10.1089/10926420150502959

91. Yao CC, Wong HH, Yang CC, Lin CS. Abdominal wall abscess secondary to spilled gallstones: late complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy and preventive measures. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. (2001) 11(1):47–51. doi: 10.1089/10926420150502959

92. Zeledon-Ramirez M, Siles-Chaves I, Sanchez-Cabo A. Case report: dropped gallstones diagnosis is hindered by incomplete surgical notes and a low index of suspicion. Int J Surg Case Rep. (2022) 93:106965. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2022.106965

93. Gupta V, Jain G. Safe laparoscopic cholecystectomy: adoption of universal culture of safety in cholecystectomy. World J Gastrointest Surg. (2019) 11(2):62–84. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v11.i2.62

94. Griffiths EA, Hodson J, Vohra RS, Marriott P, Chole SSG, Katbeh T, et al. Utilisation of an operative difficulty grading scale for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. (2019) 33(1):110–21. doi: 10.1007/s00464-018-6281-2

95. Harclerode TP, Gnugnoli DM. Percutaneous Abscess Drainage. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls (2023). ineligible companies. Disclosure: David Gnugnoli declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

96. Gavriilidis P, Catena F, de'Angelis G, de'Angelis N. Consequences of the spilled gallstones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a systematic review. World J Emerg Surg. (2022) 17(1):57. doi: 10.1186/s13017-022-00456-6

97. GlobalSurg. Global Surgery Research. Available online at: https://www.globalsurgeryunit.org/clinical-trials-holding-page/global-surg/ (cited September 24, 2023).

Keywords: spilled, lost, gallstones, laparoscopic cholecystectomy, abscess, case report, systematic review

Citation: Danhel L, Fritz A, Havranek L, Kratzer T, Punkenhofer P, Punzengruber A, Rezaie D, Tatalovic S, Wurm M, Függer R, Biebl M and Kirchweger P (2024) Lost gallstones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy as a common but underestimated complication—case report and review of the literature. Front. Surg. 11:1375502. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2024.1375502

Received: 23 January 2024; Accepted: 18 March 2024;

Published: 9 April 2024.

Edited by:

Antonia Rizzuto, University of Magna Graecia, ItalyReviewed by:

Abdul Wahed Nasir Meshikhes, Alzahra General Hospital, Saudi ArabiaRahul Gupta, Synergy Institute of Medical Sciences, India

© 2024 Danhel, Fritz, Havranek, Kratzer, Punkenhofer, Punzengruber, Rezaie, Tatalovic, Wurm, Függer, Biebl and Kirchweger. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: P. Kirchweger cGF0cmljay5raXJjaHdlZ2VyQG9yZGVuc2tsaW5pa3VtLmF0

L. Danhel

L. Danhel A. Fritz

A. Fritz L. Havranek1,2

L. Havranek1,2 M. Biebl

M. Biebl P. Kirchweger

P. Kirchweger