- 1Faculty of Medicine, Al Andalus University, Tartus, Syria

- 2International Medical Research Association (IMedRA), Cairo, Egypt

- 3Faculty of Medicine, Alexandria University, Alexandria, Egypt

- 4Radiology department, National cancer institute, Misurata, Libya

- 5Faculty of Medicine, University of Constantine 3 Salah Boubnider, Constantine, Algeria

- 6Faculty of Medicine, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt

- 7Faculty of Medicine, University of Bahri, Khartoum, Sudan

- 8New York State Department of Health, Albany, NY, United States

Placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) can cause complications like hysterectomy or death due to massive pelvic bleeding. We aim to evaluate the efficacy of two different arterial ligation techniques in controlling postpartum haemorrhage and minimizing bleeding complications. We searched six databases. 11 studies were finally included into our review and analysis. We graded their quality using the Cochrane tool for randomized trials and the NIH tool for retrospective studies. Our analysis showed that internal iliac artery ligation has no significant effect on bleeding control (MD = −248.60 [−1045.55, 548.35] P = 0.54), while uterine artery ligation significantly reduced the amount of blood loss and preserved the uterus (MD = −260.75, 95% CI [−333.64, −187.86], P < 0.00001). Uterine artery ligation also minimized the need for blood transfusion. Bleeding was best controlled by combining both uterine artery ligation with uterine tamponade (MD = 1694.06 [1675.34, 1712.78], P < 0.00001). This combination also showed a significant decrease in hysterectomy compared to the uterine artery ligation technique alone. Bilateral uterine artery ligation in women with placenta accreta spectrum can effectively reduce the amount of bleeding and the risk of complications. The best bleeding control tested is a combination of both, uterine artery ligation and cervical tamponade. These techniques may offer an easy and applicable way to preserve fertility in PAS patients. Larger randomized trials are needed to define the best technique.

1. Introduction

Placental abnormalities are a wide group of pathologies that lead to pregnancy complications including postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) and hysterectomy. Two of the most commonly searched and encountered abnormalities are placenta accreta and placenta previa. The estimated risk of postpartum haemorrhage caused by the placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) was 41% (1). PAS is considered the main cause of postpartum hysterectomy (2). According to the latest reports, 1 of every 400 pregnancies is diagnosed with placenta accreta spectrum disorder and the incidence is increasing due to the increased number of cesarean deliveries (CD) -its main risk factor (3, 4). Other risk factors include advanced maternal age, multiparity and placenta previa (3). Clark et al. established a significant association, which implies that the risk of developing placenta accreta in patients with previous placenta previa and one previous CD is 24% and the risk increases to 67% in patients with previous placenta previa and three or more CD (5). So far, the most generally accepted management of PAS is cesarean hysterectomy (6).

Besides the maternal bleeding that requires immediate blood transfusion and increases the risk of infections and hypersensitivity reactions, the neonates may be born preterm or of low birth weight, and their 5- minutes APGAR scores may be reduced (7). ICU administration and longer hospital stay are also reported (8). Prenatal diagnosis can help to reduce both maternal morbidity and mortality (9).

In order to preserve fertility and improve maternal outcomes, several methods were developed such as arterial occlusion either by ligation or balloon catheter or embolization. Uterine sutures and administration of either uterotonic agents or methotrexate were also suggested (10–13).

Internal iliac artery ligation is a well-established procedure that was first described by Kelly in 1894 (14) and since that time, several studies investigated its effect. Multiple trials aimed to increase its efficacy by combination with balloon catheterization or tranexamic acid (15, 16). Evidence is controversial about the efficacy and use of this procedure. In this study, we aim to evaluate its efficacy by meta-analysis mainly in reducing maternal haemorrhage and blood transfusion, then compare it to other techniques demonstrated in the literature. We also aim to check the safety of the procedure by investigating its complications.

2. Materials and methods

We followed the guidelines of Cochrane handbook of systematic reviews (17) and the regulations of preferred reporting items of systematic reviews and meta-analysis (The PRISMA 2020 update) (18, 19) and MOOSE guidelines (20) during the conduction of this review. (A filled form of PRISMA 2020 checklist was submitted)

2.1. Search strategy

We used MeSH terms to form the following search strategy [(“Placenta, Retained” OR “Placenta accreta” OR “placenta percreta” OR “ placenta increta” OR “abnormally Invasive placenta” OR “Morbidly adherent placenta”) AND (ligation) AND (“iliac artery” OR “hypogastric artery” OR “uterine artery”)] to search six databases: PubMed, SCOPUS (Title and abstract search for terms), Cochrane Central, Web Of Science, VHL and Open Grey during the period of May 2020 and updated our search in September 2021, for a further check, two authors performed a manual search by screening the references of the included studies.

2.2. Study selection

Our inclusion criteria were: All the reports which compared artery ligation technique either internal iliac or the uterine artery to conservative therapy or any other intervention. Trials which included only PAS patients were included in our final analysis. The main outcome was blood loss reported in means and standard deviation. The accepted study designs were: Randomized control trials (RCTs) and Cohort studies. And thus, PICO criteria for our review shall be:

Population: Pregnant women with placenta accreta spectrum disorder.

Intervention: Internal iliac artery ligation or Uterine artery ligation.

Comparison: control group or any other intervention.

Outcome: Amount of blood loss and blood transfusion and any reported complication.

We excluded case reports, conference abstracts and studies that didn't report our desired outcomes. All the included studies used standard methods for limiting blood loss such as external compression and oxytocin before residing to either artery ligation or control therapy they also excluded patients with history of bleeding disorders and anticoagulants. Studies that combined other approaches with artery ligation such as tranexamic acid or balloon occlusion were excluded from our analysis. We have gone through two steps to select the eligible studies, (1) Title and abstract screening (2) full-text screening, authors were grouped into two groups and each group performed the screening and data collection separately. The first author resolved the disputes and compared the results from the two groups. The second and the last authors were primarily responsible for data analysis and writing.

2.3. Data extraction

We extracted the data from the included studies in two Excel sheets, in the first one, two authors extracted baseline characteristics of the eligible patients: Age, BMI, parity, gravidity, number of previous cesarean sections etc. and the other contained outcomes measurement, we divided the main outcomes into (a) Primary outcomes: Blood loss (ml) and haemoglobin change(g/dl) and (b) secondary outcomes: Blood products transfusion(units), duration of surgery(min), duration of hospital stay(days) and complications such as bladder injuries, hysterectomy, isaventensive care unit admission and coagulopathy. And after finishing the task every two authors revised the other two authors' work, A. Nabhan and Y. AbdelQadir revised the entire work.

2.4. Risk of bias assessment

We used the Cochrane tool to assess the risk of bias in randomized trials, as described in chapter 8.5. Depending on the following items: Random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and other bias (Missing protocol or funding issues would be considered as a source of risk), each item was graded as high risk, low risk or unclear risk of bias.

The quality of the included cohort studies (prospective and retrospective) was assessed by a quality assessment tool of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) (21). We used the tool for observational cohort studies included in our final screening. This tool is composed of 14 questions to assess the risk of bias and confounders. These questions were answered by “yes”, “no”, “cannot determine”, “not applicable”, or “not reported” then each study was given a score to guide the overall rating of the quality as “good”, “fair”, or “poor” quality.

2.5. Data analysis

We used the Review Manager Software version 5.4 to perform the meta-analysis; the continuous outcomes were measured as mean difference (MD) and standard deviation (SD), and the dichotomous outcomes as risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence interval. In case of heterogeneity (Chi-square P value < 0.1), a random effect model was adopted, otherwise, a fixed-effect model was employed, and we used “take one out” method to resolve the heterogeneity, in general; the results were considered significant if the P-value was less than 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Literature search

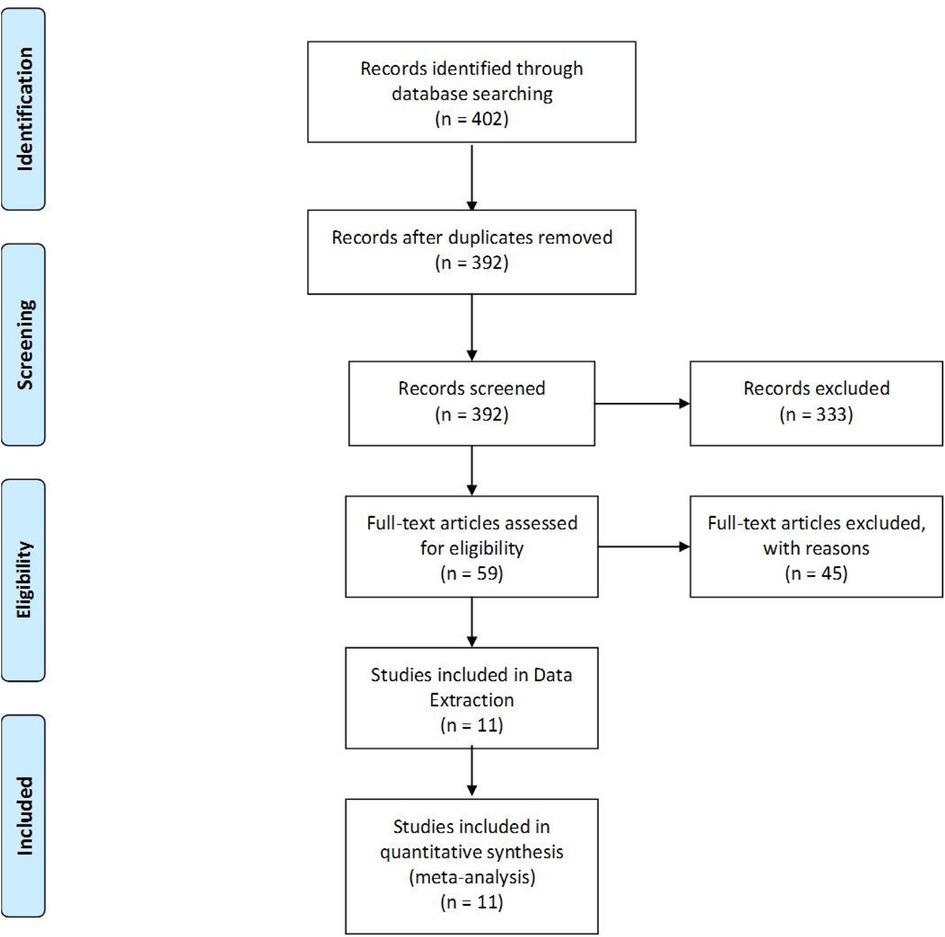

The literature search retrieved 402 citations. After title and abstract screening, 59 Articles were retrieved for further evaluation (full-text screening). Four randomized trials and ten cohort studies were included. Finally, 11 studies with 759 patients were included in data extraction. (Details about the screening process is demonstrated in PRISMA flowchart Figure 1).

3.2. Characteristics of included studies

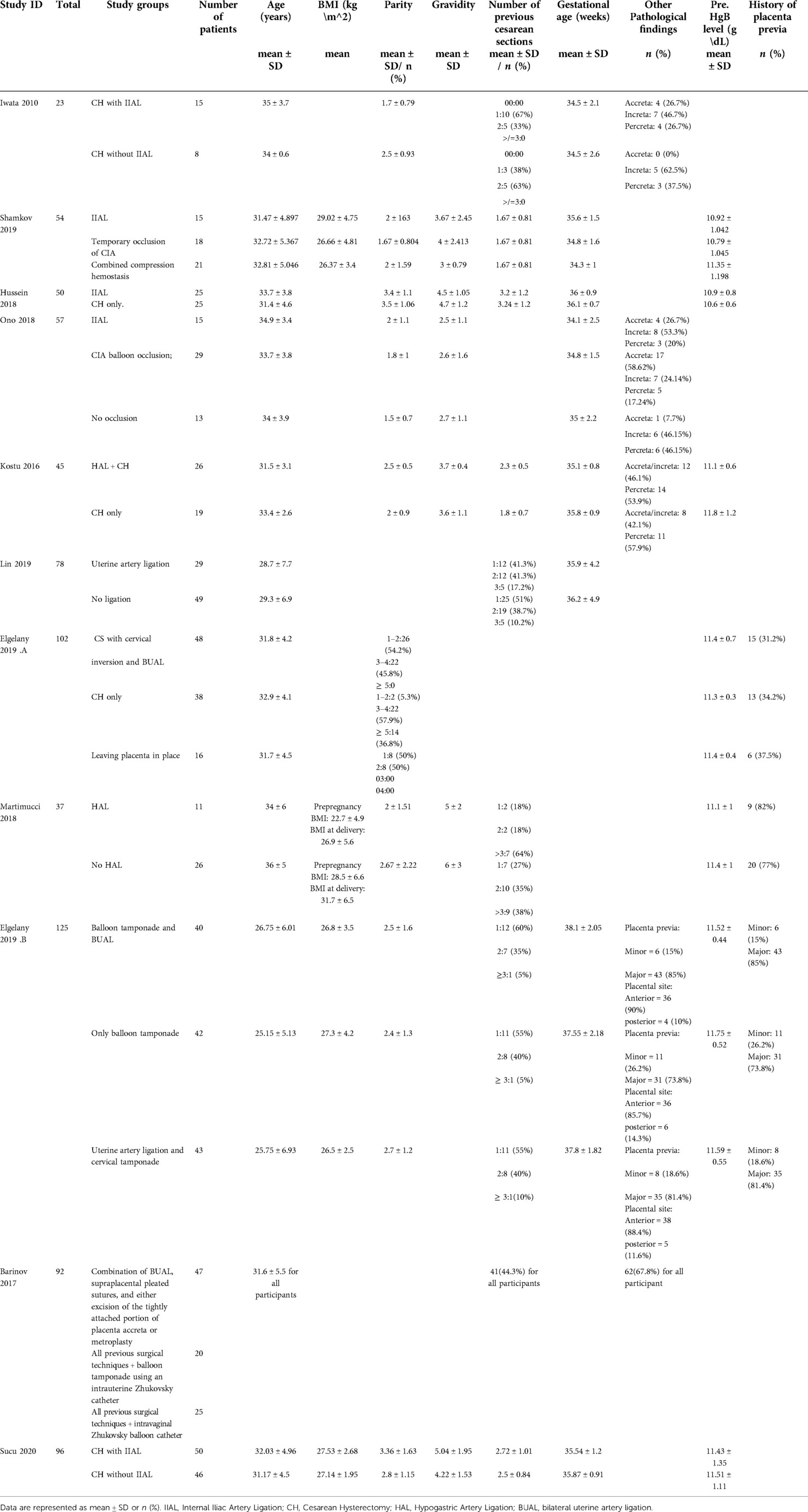

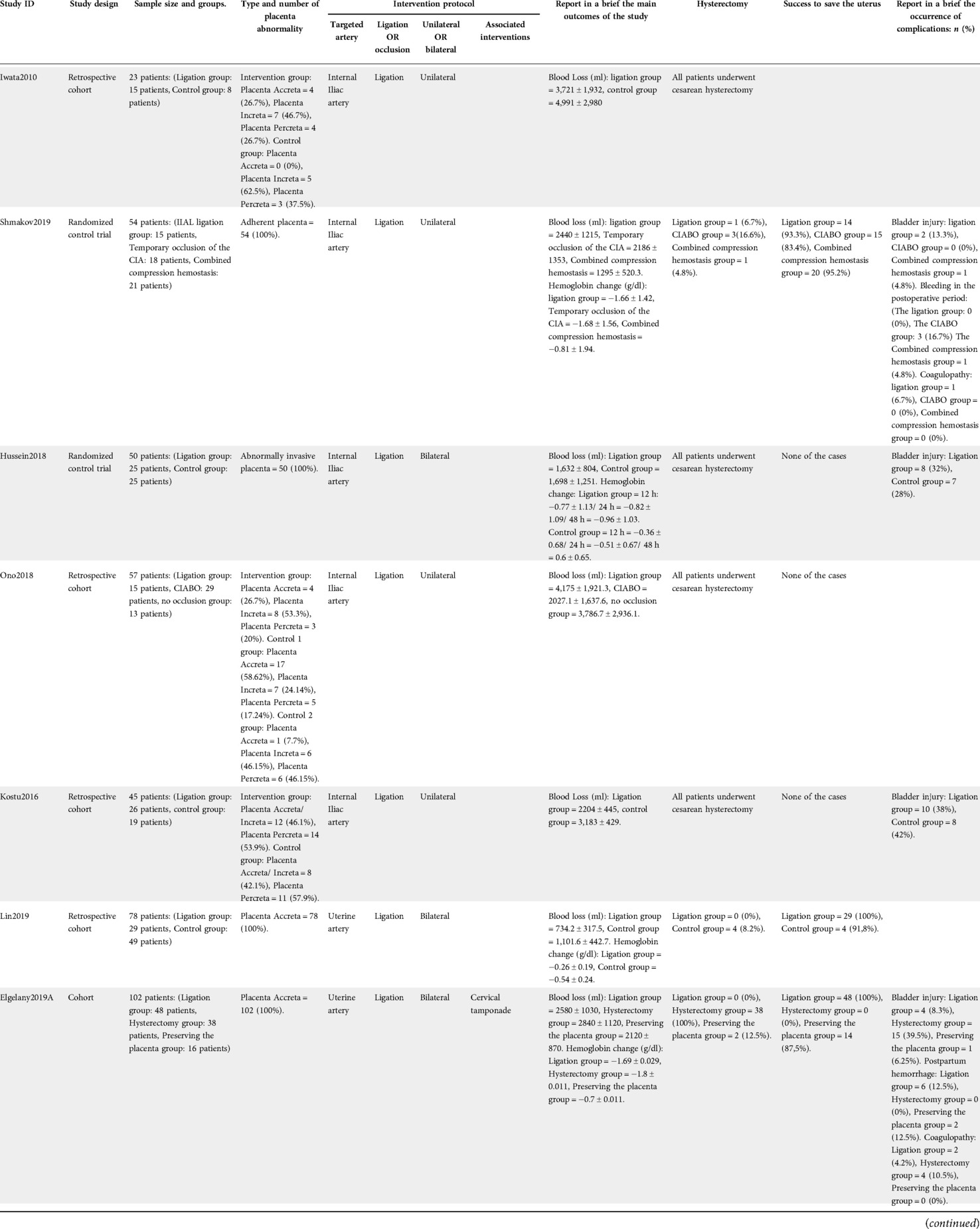

Baseline characteristics of the included studies including diagnosis and history of pregnancy are shown in (Table 1). Summary of the included studies and their results are shown in (Table 2).

A summary of the quality assessment for the included randomized trials (22, 23) is shown in Supplementary appendix 1. Six cohort studies (24–28) were fair in quality according to NIH quality assessment tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. The other four cohort studies (16, 29–31) and were of poor quality. For more details and answers to all assessment questions in each study, (See Supplementary appendix 1).

3.2.1. Internal iliac artery ligation vs. control

3.2.1.1. Blood loss

3.2.1.1.1. Blood loss (ml)

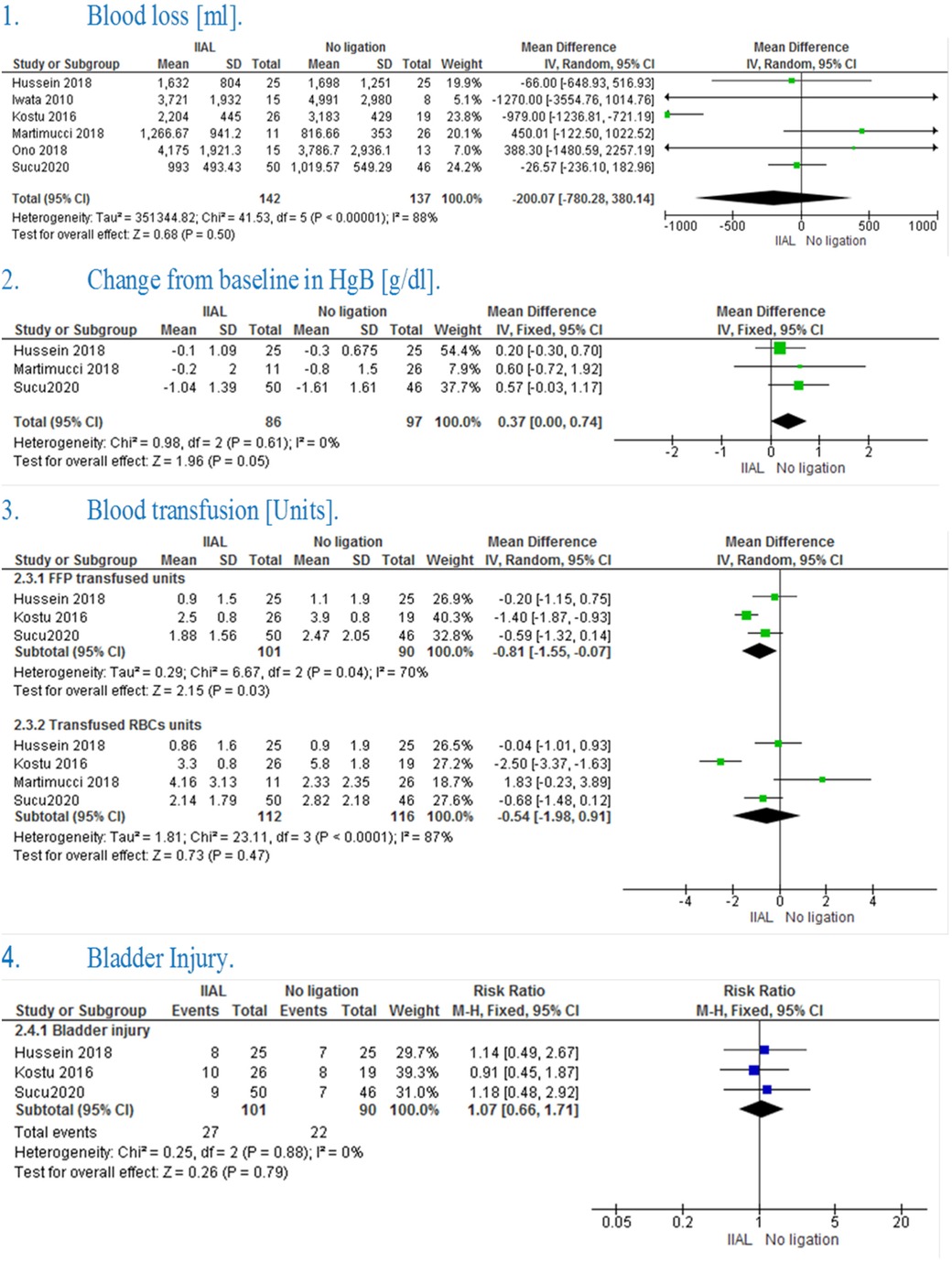

The pooled effect estimate showed no significant difference between IIAL and no ligation (MD = −200.07 [−780.28, 380.14], P = 0.50). Pooled results were heterogeneous (P < 0.00001, I² = 88%) and the detected heterogeneity was best resolved after excluding Kostu et al. (P = 0.43, I² = 0%) and the effect estimate remained non-significant (MD = 15.09 [−169.81, 199.99], P = 0.87). [Figure 2(1)]

3.2.1.1.2. Change in HgB from baseline (g/dl)

The pooled studies showed a significant change in hemoglobin level from the baseline in IIAL in comparison with No ligation (MD = 0.37 [0.00, 0.74], P = 0.05). Pooled studies were homogenous (P = 0.61, I² = 0%) [Figure 2(2)]

3.2.1.2. Blood products transfusion

3.2.1.2.1. Fresh frozen plasma transfusion (units)

The pooled mean difference showed that IIAL significantly reduced the need for FFP transfusion in comparison with No ligation (MD = −0.81 [−1.55, −0.07], P = 0.03) The pooled studies were heterogeneous (P = 0.43, I² = 70%) and the detected heterogeneity was best resolved after excluding Kostu et al. (P = 0.52, I² = 0%) but the effect estimate became non-significant (MD = −0.44 [−1.02, 0.14], P = 0.13) [Figure 2(3)].

3.2.1.2.2. Packed RBCs transfusion (units)

The pooled mean difference showed no statistically significant difference between the two groups (MD = −0.54 [−1.98, 0.91], P = 0.47).The pooled studies were heterogeneous (P < 0.0001, I² = 87%) and the detected heterogeneity couldn't be resolved [Figure 2(3)]

3.2.1.3. Complications

3.2.1.3.1. Bladder injury

The pooled risk ratio showed no statistically significant difference in bladder injury (RR = 1.07 [0.66, 1.71], P = 0.79). Pooled results were homogenous (P = 0.88, I² = 0%) [Figure 2(4)]

3.2.2. Uterine artery ligation vs. no ligation

3.2.2.1. Blood loss

3.2.2.1.1. Blood loss (ml)

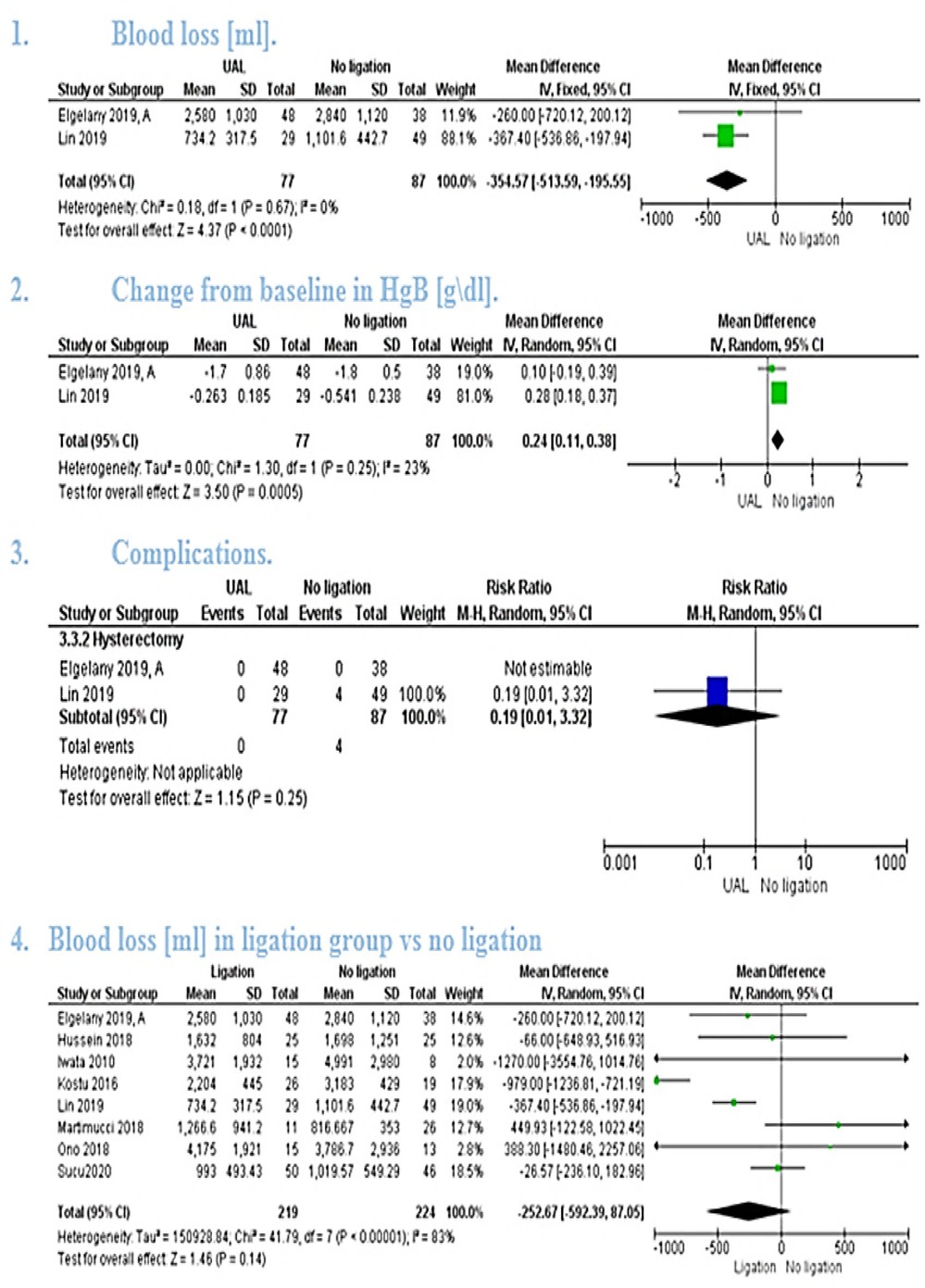

The pooled mean difference showed that uterine artery ligation significantly lowered the amount of blood loss (MD = −354.57, 95% CI [−513.59, −195.55], P < 0.0001). [Figure 3(1)] the pooled studies were homogeneous (P = 0.67, I² = 0%).

3.2.2.1.2. Change in HgB from baseline (g/dl)

The pooled mean difference showed that uterine artery ligation significantly lowered the change in hemoglobin (MD = 0.24, 95% CI [0.11, 0.38], P = 0.0005). [Figure 3(2)] The pooled studies were homogeneous (P = 0.25, I² = 23%).

3.2.2.2. Complications

3.2.2.2.1. Hysterectomy

The pooled risk ratio showed no significant difference between the two groups (RR = 0.19, 95% CI [0.01, 3.32], P = 0.25). Heterogeneity test was not applicable [Figure 3(3)].

3.2.3. Artery ligation vs. control

The pooled studies showed no statistically significant difference between Artery ligation and ligation groups (MD = −252.67 [−592.39, 87.05], P = 0.14).The pooled studies were heterogeneous (P = 0 < 0000.1, I² = 83%) [Figure 3(4)] and the detected heterogeneity couldn't be resolved by removing a single study.

3.2.4. Ligation vs. combined uterine tamponade and ligation

3.2.4.1. Blood loss (ml)

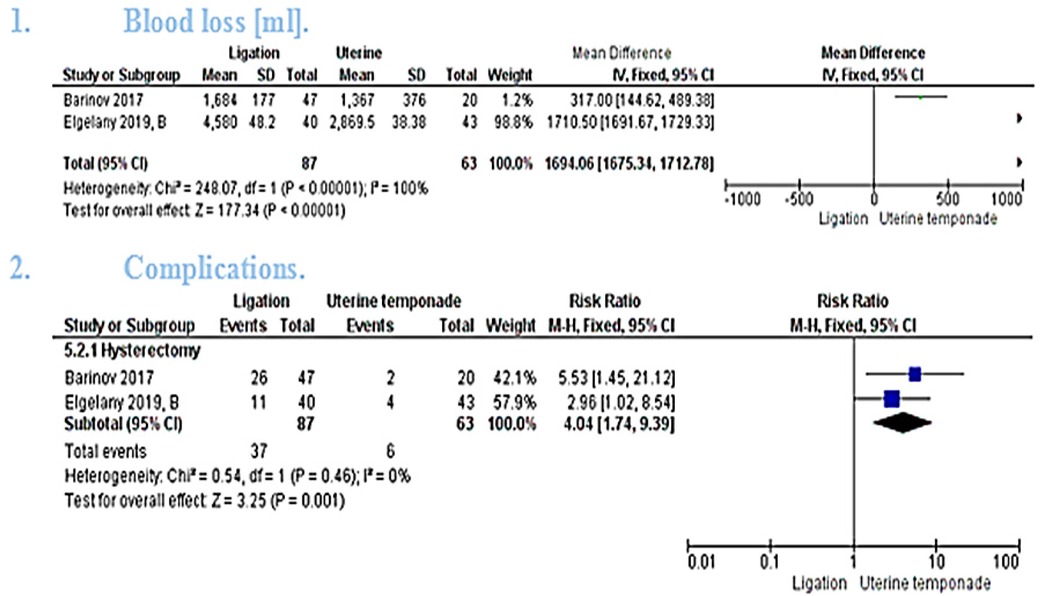

The pooled mean difference showed that combined temponade and ligation cause significant reduction in the amount of blood loss (MD = 1694.06 [1675.34, 1712.78], P < 0.00001). The pooled studies were heterogeneous (P < 0.00001, I² = 100%) and the detected heterogeneity couldn't be resolved because only 2 studies were included in the analysis [Figure 4(1)].

3.2.4.2. Hysterectomy

The pooled studies showed statistically significant higher risk ratio of hysterectomy in ligation group (RR = 4.04 [1.74, 9.39], P = 0.001). The pooled studies were homogeneous (P = 0.46, I² = 0%) [Figure 4(2)].

4. Discussion

Our results showed that Internal iliac artery ligation has no significant advantage over the control group in neither blood loss (ml), haemoglobin change from the baseline nor blood elements transfusion. This corresponds with the results from the individual included studies. On the other hand, Uterine artery ligation in adherent placenta patients planned to preserve the uterus showed a significant decrease in blood loss and change in haemoglobin from the baseline. While the best blood controlling result was obtained by combining both uterine artery ligation and uterine tamponade.

Artery ligation is used in a wide variety of operations to minimize bleeding; internal iliac artery ligation has been primarily used in women undergoing hysterectomy whilst uterine artery ligation has been used in women to help save fertility. For better results, surgeons should always ligate the internal iliac artery distal to its posterior division. In complete placenta previa cases, the placental site receives a major amount of blood from the descending cervical and vaginal arteries. Even after ligation of the uterine artery, these arteries still perfuse the lower segment which causes the haemorrhage to continue. In this case, IIAL is favoured because it stops the blood flow in the uterine, cervical and vaginal vessels (32).

In order to improve the efficacy of arterial ligation, several methods were proposed. Abbas et al. investigated the addition of Tranexamic acid to bilateral uterine artery ligation (BUAL) in placenta previa patients and it greatly reduced the amount of blood loss, but the risk of thromboembolism hinders its use as prophylaxis for PPH (15). Another technique was introduced by El Gelany et al., in which he used the cervix as a natural tamponade through inverting the cervix into the uterine cavity and suturing its lips to the lower uterine segments (26). The combination of this technique with BUAL proved to be more effective than BUAL only. In another study by Elgelany et al., he advised the use of the previous technique only in patients with focal placenta accreta wishing to preserve fertility. He also offered to leave the placenta in place for patients with diffuse placenta accreta hoping to preserve fertility. Further elective laparotomy to remove the placenta is necessary, and patients may later require embolization of the uterine artery or delayed hysterectomy (16). The results of our study –result of artery ligation techniques- support the recently published article by İçen et al. which discussed the experience of a tertiary hospital in turkey which revealed that IIAL use successfully preserved fertility in 65.9% of patients of women included. Of the 70 included placenta accreta patients, the uterus could be preserved in 47 patients (33). A promising approach was suggested by Barinov et al. to preserve fertility, which reduced blood transfusion rate by 2.4 folds. He used a combination of BUAL and external supra placental pleated sutures with either excision of a small area of placenta accreta or full metroplasty and simultaneous use of intrauterine and vaginal balloon Zhukovsky catheters. This induced greater occlusion of the collateral circulation (29). Another novel technique is the use of the LigaSure instruments, which uses high frequency and low voltage electric current to occlude blood vessels, showed a significant reduction in blood loss (34).

BAKRI balloon catheter is a very simple, easily applicable and safe technique that helps reduce PPH (35). However, results published by El Gelany et al. show that it offers a nearly similar effect to the artery ligation (16). On the other hand, our results showed that a combination of uterine tamponade and ligation is more effective than ligation only (P < 0.00001).

Arterial balloon occlusion is another proposed technique to decrease PPH. Its main complications are lower limb ischemia and radiation exposure effect on the fetus. It's commonly done in the ILA, but results showed no significant decrease in blood loss (36). Ono et al. suggested that common iliac artery balloon occlusion (CIABO) decreases blood loss more significantly than IIA occlusion because it blocks the collateral circulation that arises from the external iliac artery during ischemia (31). He also found that CIABO decreases blood loss even more than ILAL. Wei et al. tried to improve its effect by occluding the abdominal aorta, but results showed no significant difference from internal iliac artery occlusion (37).

The choice of a wide range of diseases for testing the intervention was based on the available data. Many of the included articles didn't specify the level of placental adhesion and future research should target the effect of the intervention on each of the causes of postpartum haemorrhage. The methods of blood loss estimation differed between the included studies and some retrospective studies didn't specify exactly the method for estimation. In order to investigate the effect of such differences on our results, we performed a subgroup analysis based on the study design and the results were similar to the primary results reported in the manuscript which showed that such differences were unlikely to affect the final results and interpretation of our analysis (Supplementary Appendix 2).

Limitations of our review include 1- the limited number of randomized trials and low sample size in some included studies. 2- Patient's settings and baseline characteristics including the type of PAS differed among studies and the unknown history of bleeding disorders in some of the retrospective studies that may have contributed to the detected heterogeneity. 3- Inclusion of retrospective cohort studies alongside RCTs. 4- No protocol registration was done for this review but the steps for each stage are provided in details in the methods section under supervision of experienced and published authors.

In conclusion, uterine artery ligation can significantly reduce the amount of blood loss and hence, preserve the fertility of women with the adherent placenta. Combined IIAL and tamponade is an effective way to minimize bleeding in patients undergoing hysterectomy and might serve as an option to preserve fertility. Larger multi-centre randomized trials are needed to improve this combination and generalize the fertility saving methods.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

All authors enlisted in this review participated in the preparation of this work and revised the final datasheet and manuscript. AEN: led the study team, performed the analysis and revised the tasks of members. YHA: wrote the manuscript, planned and revised the analysis, and responded to the reviewers' comments. Authors (YAA, MOK, NS, ANA, MMEE, JS): participated in screening the databases, performing manual search preparing the study tables and data extraction. AZN: performed quality assessment, paragraph editing and prepared the supplementary files. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Dr. Mohamed Fahmy Doheim for his kind advice and recommendations during the design and analysis of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsurg.2022.983297/full#supplementary-material.

References

1. Mehrabadi A, Hutcheon JA, Liu S, Bartholomew S, Kramer MS, Liston RM, et al. Contribution of placenta accreta to the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage and severe postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. (2015) 125:814–21. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000722

2. Usta IM, Khalifeh T, Nassar AH. Peripartum hysterectomy: 1999 to 2006. Obstet Gynecol. (2008) 111:1446. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31817aff21

3. Miller DA, Chollet JA, Goodwin TM. Clinical risk factors for placenta previa–placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (1997) 177:210–4. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(97)70463-0

4. Matsuzaki S, Mandelbaum RS, Sangara RN, McCarthy LE, Vestal NL, Klar M, et al. Trends, characteristics, and outcomes of placenta accreta spectrum: a national study in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (2021)225(5):534. e1–534 e38. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.04.233

5. Clark SL, Koonings PP, Phelan JP. Placenta previa/accreta and prior cesarean section. Obstet Gynecol. (1985) 66:89–92.4011075

6. Placenta Accreta Spectrum | ACOG. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/obstetric-care-consensus/articles/2018/12/placenta-accreta-spectrum (Accessed February 18, 2021) (n.d.).

7. Seet EL, Kay HH, Wu S, Terplan M. Placenta accreta: depth of invasion and neonatal outcomes. J Matern Neonatal Med. (2012) 25:2042–5. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2012.678429

8. Warshak CR, Ramos GA, Eskander R, Benirschke K, Saenz CC, Kelly TF, et al. Effect of predelivery diagnosis in 99 consecutive cases of placenta accreta. Obstet Gynecol. (2010) 115:65–9. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c4f12a

9. Chantraine F, Braun T, Gonser M, Henrich W, Tutschek B. Prenatal diagnosis of abnormally invasive placenta reduces maternal peripartum hemorrhage and morbidity. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. (2013) 92:439–44. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12081

10. Tsirulnikov MS. Ligation of the uterine vessels during obstetrical hemorrhages. Immediate and long-term results (author's Transl). J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). (1979) 8:751–3.317962

11. Cho JH, Jun HS, Lee CN. Hemostatic suturing technique for uterine bleeding during cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. (2000) 96:129–31. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(00)00852-8

12. Bretelle F, Courbière B, Mazouni C, Agostini A, Cravello L, Boubli L, et al. Management of placenta accreta: morbidity and outcome. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. (2007) 133:34–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.07.050.16965851

13. Kerber C. Balloon catheter with a calibrated leak. Radiology. (1976) 120:547–50. doi: 10.1148/120.3.547

14. Kelly HA. Ligation of both internal iliac arteries for hemorrhage in hysterectomy for carcinoma uteri. Journal de gynécologie, obstétrique et biologie de la reproduction. (1984) 20:248.

15. Abbas AM, Shady NW, Sallam HF. Bilateral uterine artery ligation plus intravenous tranexamic acid during cesarean delivery for placenta previa: a randomized double-blind controlled trial. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. (2019) 48:115–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jogoh.2018.10.023

16. El Gelany S, Ibrahim EM, Mohammed M, Abdelraheim AR, Khalifa EM, Abdelhakium AK, et al. Management of bleeding from morbidly adherent placenta during elective repeat caesarean section: retrospective -record -based study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2019) 19:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12884-019-2244-4

17. Book Series C, Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions the cochrane collaboration®. (n.d.) United kingdom, cochrane collaboration: Wiley online library.

18. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Br Med J. (2009) 339:332–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535

19. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br Med J. (2021):372:n71. doi: 10.1136/BMJ.N71

20. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. (2000) 283:2008–12. doi: 10.1001/JAMA.283.15.2008

22. Hussein AM, Dakhly DMR, Raslan AN, Kamel A, Abdel Hafeez A, Moussa M, et al. The role of prophylactic internal iliac artery ligation in abnormally invasive placenta undergoing caesarean hysterectomy: a randomized control trial. J Matern Neonatal Med. (2019) 32:3386–92. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2018.1463986

23. Shmakov RG, Vinitskiy AA, Chuprinin VD, Yarotskaya EL, Sukhikh GT. Alternative approaches to surgical hemostasis in patients with morbidly adherent placenta undergoing fertility-sparing surgery. J Matern Neonatal Med. (2019) 32:2042–8. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2018.1424821

24. Köstü B, Özer A, Ercan Ö, Bakacak M, Karakuş S, Keten H. Prophylactic hypogastric artery ligation in surgery for placental invasion disorders. Int J Clin Exp Med. (2016) 9:16735–40. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1666793

25. Lin J, Lin F, Zhang Y. Uterine artery ligation before placental delivery during caesarean in patients with placenta previa accreta. Med (United States). (2019) 98:1–4. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000016780

26. El Gelany S, Mosbeh MH, Ibrahim EM, Mohammed M, Khalifa EM, Abdelhakium AK, et al. Placenta accreta Spectrum (PAS) disorders: incidence, risk factors and outcomes of different management strategies in a tertiary referral hospital in minia, Egypt: a prospective study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2019) 19:313. doi: 10.1186/s12884-019-2466-5

27. Kuhn T, Martimucci K, Al-Khan A, Bilinski R, Zamudio S, Alvarez-Perez J. Prophylactic hypogastric artery ligation during placenta percreta surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Am J Perinatol Rep. (2018) 08:e142–5. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1666793

28. Sucu S, Özcan HÇ, Karuserci ÖK, Demiroğlu Ç, Tepe NB, Bademkıran MH. Is there a role of prophylactic bilateral internal iliac artery ligation on reducing the bleeding during cesarean hysterectomy in patients with placenta percreta? A Retrospective Cohort Stud. (2020) 91:1–6. doi: 10.5603/GP.a2020.0145

29. Barinov S, Tirskaya Y, Medyannikova I, Shamina I, Shavkun I. A new approach to fertility-preserving surgery in patients with placenta accreta. J Matern Neonatal Med. (2019) 32:1449–53. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2017.1408066

30. Iwata A. Limitations of internal iliac artery ligation for the reduction of intraoperative hemorrhage during cesarean hysterectomy in cases of placenta previa accreta. Obstet Gynaecol Res. (2010) 36:254–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2009.01157.x

31. Ono Y, Murayama Y, Era S, Matsunaga S, Nagai T, Osada H, et al. Study of the utility and problems of common iliac artery balloon occlusion for placenta previa with accreta. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. (2018) 44:456–62. doi: 10.1111/jog.13550

32. Joshi VM, Otiv SR, Majumder R, Nikam YA, Shrivastava M. Internal iliac artery ligation for arresting postpartum haemorrhage. BJOG An Int J Obstet Gynaecol. (2007) 114:356–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01235.x

33. İçen MS, Findik FM, Akin Evsen G, Ağaçayak E, Yaman Tunç S, Evsen MS, et al. Hypogastric artery ligation in postpartum haemorrhage: a ten-year experience at a tertiary care centre. J Obstet Gynaecol. (2021) 41:536–40. doi: 10.1080/01443615.2020.1755623

34. Bakacak Z, Bakacak M, Uzkar A, Yazar FM, Yaylalı A, Boran ÖF, et al. The efficacy of LigaSure™ open instruments in cases of cesarean hysterectomy due to placenta percreta: a retrospective, record-based, comparative study. J Matern Neonatal Med. (2021) 34:960–5. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2020.1846177

35. Bakri YN. Uterine tamponade-drain for hemorrhage secondary to placenta previa-accreta. Int J Gynecol Obstet. (1992) 37:302–3. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(92)90336-H

36. Papillon-Smith J, Hobson S, Allen L, Kingdom J, Windrim R, Murji A. Prophylactic internal iliac artery ligation versus balloon occlusion for placenta accreta spectrum disorders: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Gynecol Obstet. (2020) 151:91–6. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13256

Keywords: accreta, blood loss, internal iliac artery ligation, placenta accreta spectrum, uterine artery

Citation: Nabhan AE, AbdelQadir YH, Abdelghafar YA, Kashbour MO, Salem N, Abdelkhalek AN, Nourelden AZ, Eshag MME and Shah J (2022) Therapeutic effect of Internal iliac artery ligation and uterine artery ligation techniques for bleeding control in placenta accreta spectrum patients: A meta-analysis of 795 patients. Front. Surg. 9:983297. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2022.983297

Received: 2 July 2022; Accepted: 11 August 2022;

Published: 1 September 2022.

Edited by:

Andrea Tinelli, Xi'an Jiaotong University, ChinaReviewed by:

Sarma Nursani Lumbanraja, University of North Sumatra, IndonesiaDiana Buzinskiene, Vilnius University, Lithuania

© 2022 Nabhan, AbdelQadir, Abdelghafar, Kashbour, Salem, Abdelkhalek, Nourelden, Eshag and Shah. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ayman Essa Nabhan YXltYW5pc3NhLm5iQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Specialty Section: This article was submitted to Obstetrics and Gynecological Surgery, a section of the journal Frontiers in Surgery

Ayman Essa Nabhan

Ayman Essa Nabhan Yossef Hassan AbdelQadir

Yossef Hassan AbdelQadir Yomna Ali Abdelghafar

Yomna Ali Abdelghafar Muataz Omar Kashbour

Muataz Omar Kashbour Nour Salem

Nour Salem Abdelrahman Naeim Abdelkhalek

Abdelrahman Naeim Abdelkhalek Anas Zakarya Nourelden6,2

Anas Zakarya Nourelden6,2 Mona Muhe Eldeen Eshag

Mona Muhe Eldeen Eshag Jaffer Shah

Jaffer Shah