95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Surg. , 06 June 2022

Sec. Visceral Surgery

Volume 9 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2022.827481

Qiantong Dong1,2†

Qiantong Dong1,2† Haonan Song2†

Haonan Song2† Weizhe Chen3

Weizhe Chen3 Wenbin Wang2

Wenbin Wang2 Xiaojiao Ruan2

Xiaojiao Ruan2 Tingting Xie2

Tingting Xie2 Dongdong Huang2

Dongdong Huang2 Xiaolei Chen2

Xiaolei Chen2 Chungen Xing1*

Chungen Xing1*

Background: The impact of visceral obesity on the postoperative complications of colorectal cancer in elderly patients has not been well studied. This study aims to explore the influence of visceral obesity on surgical outcomes in elderly patients who have accepted a radical surgery for colorectal cancer.

Methods: Patients aged over 65 year who had undergone colorectal cancer resections from January 2015 to September 2020 were enrolled. Visceral obesity is typically evaluated based on visceral fat area (VFA) which is measured by computed tomography (CT) imaging. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to analyze parameters related to short-term outcomes.

Results: A total of 528 patients participated in this prospective study. Patients with visceral obesity exhibited the higher incidence of total (34.1% vs. 18.0%, P < 0.001), surgical (26.1% vs. 14.6%, P = 0.001) and medical (12.6% vs. 6.7%, P = 0.022) complications. Based on multivariate analysis, visceral obesity and preoperative poorly controlled hypoalbuminemia were considered as independent risk factors for postoperative complications in elderly patients after colorectal cancer surgery.

Conclusions: Visceral obesity, evaluated by VFA, was a crucial clinical predictor of short-term outcomes after colorectal cancer surgery in elderly patients. More attentions should be paid to these elderly patients before surgery.

The incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer (CRC) have been significantly increasing in China during the past decade, ranking the third most common cancer (1). Globally, with the population becoming older in recent years, a larger number of elderly patients were diagnosed with CRC, comprising the majority of the population with CRC (2). Till now, radical resection remains the only curative treatment for CRC. Also, an increasing number of colorectal resections are being performed on more and more elderly patients. Elderly patients with CRC tend to have multiple comorbidities, decreased social and cognitive functioning, poor nutritional status, and worse prognosis such as worse overall and disease-free survival (3). In addition, they are more prone to developing morbidity and mortality after surgery as advancing age reduces physiological reserve capacity to deal with major abdominal surgery (4–6). There is still some controversy about the surgical treatment for elderly patients with CRC. Some studies indicated that elderly patients with CRC had higher postoperative complication rates than younger population (7, 8). Therefore, the surgeons must weigh the benefits of radical colorectal resection for elderly patients. Moreover, highly precise geriatric assessments to identify patients at higher risks for developing adverse outcomes are required (9–11).

Aging is also associated with dramatic changes in body fat distribution. A main concern in the aging society is the increasing prevalence of obesity, which is known as a risk factor for cancer and physical dysfunction (12). Visceral obesity is characterized by excessive amounts of intra-abdominal adipose tissue accumulation (13). Visceral obesity has been shown previously to increase the risk of surgical procedures, which may increase postoperative complication rates and hospital stay (14–16).

Colorectal cancer is well known as an “obesity-related” cancer (17, 18). Epidemiological studies indicated that there was a substantial association between the incidence of CRCs and visceral obesity (19). In recent years, emerging evidence suggests that visceral obesity is closely related to poor prognosis after colorectal surgery (15, 20, 21). The impact of visceral obesity has been demonstrated in the general population, but there is limited knowledge for the elderly population.

In this study, we investigated whether visceral obesity would predict short-term outcomes in elderly patients after resection for colorectal cancer.

This retrospective study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University. Between January 2015 and September 2020, patients aged 65 and over who underwent elective resection for colorectal cancer in Gastrointestinal Surgical Department, the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University were included. Inclusion criteria were patients who (1) had an accurate diagnosis of colorectal cancer on the basis of histological evidence before surgery; (2) were medically fit for surgery (American Society of Anesthesiologists [ASA] grade ≤III); (3) had preoperative computed tomography (CT) scans to measure abdominal VFA (within 1 month before surgery). Exclusion criteria were: (1) patients who were accepted for palliative resection or emergency surgery; (2) patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy. All surgical procedures were performed by 4 surgeons who were highly experienced in radical colorectal resections for colorectal cancer (more than 150 cases).

Patient information, including patient characteristics, operative details, and postoperative short-term outcomes, were obtained from our clinical information system. Patient characteristics, collected within 1 month before surgery, comprised age, gender, body mass index (BMI), visceral fat area (VFA), plasma albumin concentration (hypoalbuminemia was defined as a plasma albumin concentration of less than 35 g/L), hemoglobin concentration (anemia is defined as a hemoglobin concentration of less than 120 g/L in men or 110 g/L in women), American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) grade, preoperative nutritional risk screening 2002 (NRS 2002) scores (22), comorbidity (assessed by Charlson comorbidity Index score) (23), history of previous abdominal surgery, tumor location, and tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage. The parameters of operative details were laparoscopic surgery, number of dissected lymph nodes (at least 15 lymph nodes were dissected), positive lymph node, surgical durations, and combined resection. Postoperative short-term outcomes consisted of postoperative complications (during hospital stays or within 30 days after operation), postoperative hospital stays, hospitalization cost, and readmissions within 30 days of discharge. Postoperative complications were classified as grade II or higher based on the Clavien-Dindo classification system (24).

Computed tomography (CT) axial slices taken at the third lumbar vertebra (L3) was used for visceral fat area (VFA) measurements. The boundaries of the adipose tissue were outlined on the CT image using standard Hounsfield unit ranges (−150 to −50 Hu), and then VFA was calculated. To minimize measurement bias, all measurements were completed by one radiologist who was blinded for the clinical details of the subjects on a dedicated processing system (version 3.0.11.3 BN17 32 bit; INFINITT Healthcare Co., Ltd). According to a previous study, visceral obesity was defined as a VFA > 130 cm2 in men and >90 cm2 in women (25). According to this parameter, patients were stratified into visceral obesity (VO) and Non-visceral obesity (Non-VO) groups.

Normally distributed data were described as mean value and standard deviation (SD). Nonnormally distributed data were presented as median value and interquartile range (IQR). Student’s t-test, Mann–Whitney U-test (or Kruskal–Wallis H test) and Chi-square test (or Fisher’s exact test) were used to compare normally distributed variables, nonnormally distributed variables and categorical variables respectively. The multivariate logistic regression or Cox proportional hazards regression analysis (forward stepwise selection processes) was used to determine the independent risk factor. P values <0.05 (two-tailed) was considered statistically significant, and all statistical analyses were performed using SPSS statistics version 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA).

The demographic and clinicopathologic characteristics of 528 patients (261 in VO group vs. 267 in Non-VO group) included are summarized in Table 1. Mean age was 74.1 years old and 318 (60.2%) patients had male sex. The median VFA was 110.0 cm2 and 261 (49.4%) patients were defined as having visceral obesity (including 138 males and 123 females). 74 patients were diagnosed with diabetes. Additionally, women were more prone to have visceral obesity than men (P = 0.001). For the clinicopathological parameters, patients with visceral obesity had higher BMI (P < 0.001), higher albumin (P = 0.039), higher Charlson comorbidity index (P < 0.001), and lower NRS 2002 scores (P = 0.033). There were no significant differences in age, hemoglobin, previous abdominal surgery, and tumor location between the two groups. Regarding the operative parameters, the median numbers of dissected lymph nodes (25 in VO group vs. 31 in Non-VO group, P < 0.001) and the median surgical durations (180 min in VO group vs. 160 min n Non-VO group, P = 0.002) were significantly different. Moreover, two groups did not show significant differences regarding laparoscopy-assisted operation, positive lymph node and combined resection.

As shown in Table 2, the overall incidence of postoperative complications was 25.9%. The most common complications were wound infection (n = 29, 5.5%), intra-abdominal abscess (n = 27, 5.1%) and anastomotic leakage (n = 25, 4.7%). The incidence of total complications was significantly higher in the VO group than that in the Non-VO group (34.1% vs. 18.0%, P < 0.001). Further analysis of the complications showed that in the VO group, both surgical (26.1% vs. 14.6%, P = 0.001), and medical (12.6% vs. 6.7%, P = 0.022) complications were more common than for patients in the non-VO group. Regarding the details of complications, VO patients experienced more wound infection (P = 0.030), intra-abdominal abscess (P = 0.025), and pulmonary complications (P = 0.023) than Non-VO patients. No case of mortality occurred. The median postoperative hospital stay was 13 days and 25 (4.7%) patients were readmitted within 30 days of discharge. No statistically significant differences were observed in postoperative hospital stay (P = 0.583), costs (P = 0.313) or readmission rate (P = 0.792) between the two groups.

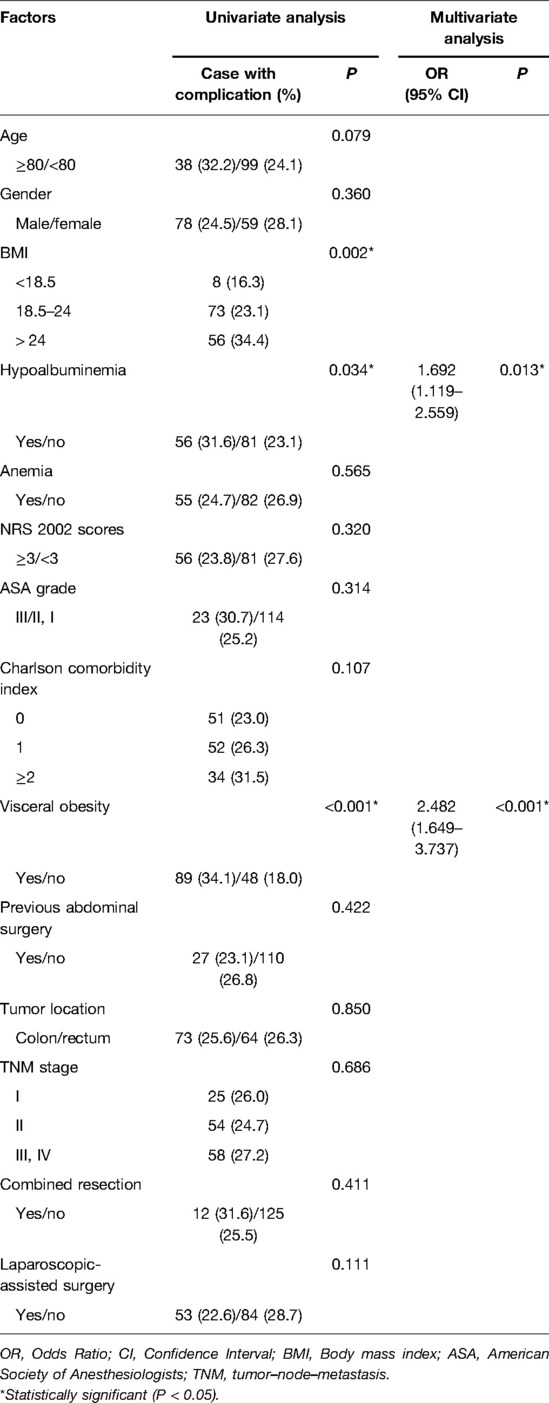

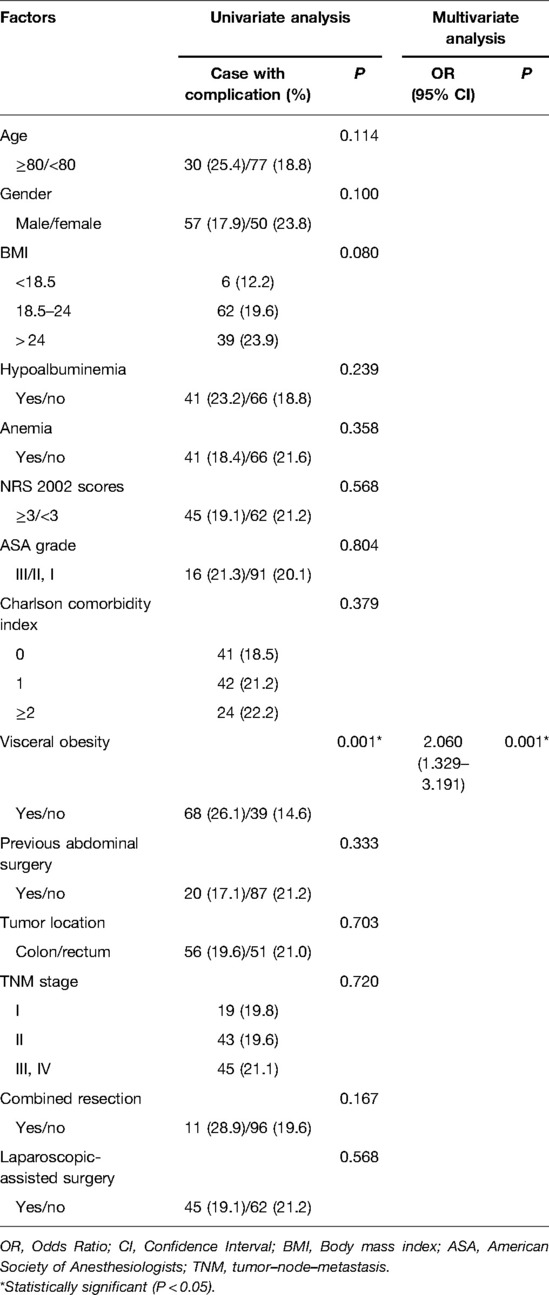

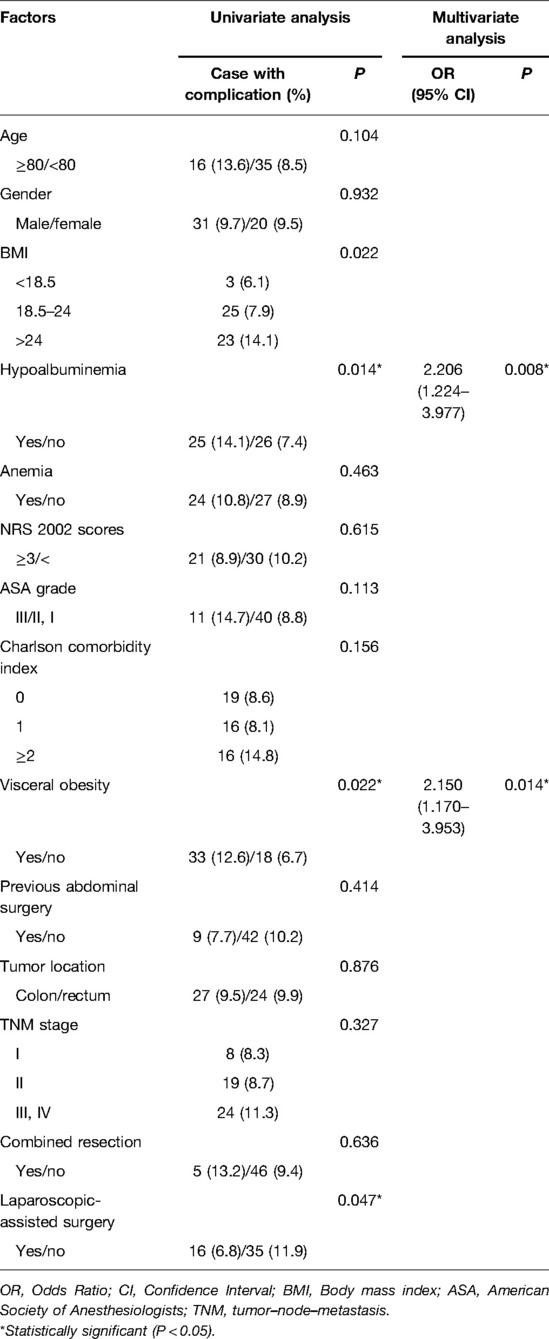

Potential risk factors for overall complications are listed in Table 3. In univariate analysis, higher BMI (P = 0.002), hypoalbuminemia (P = 0.034) and visceral obesity (P < 0.001) were associated with overall postoperative complications. The multivariate analysis revealed that hypoalbuminemia (OR: 1.692 (1.119–2.559), P = 0.013) and visceral obesity (OR: 2.482 (1.649–3.737), P < 0.001) remained as independent risk factors for overall complications. In terms of surgical complications, visceral obesity (OR: 2.060 (1.329–3.191), P = 0.001) was the unique independent risk factor (Table 4). As for medical complications, hypoalbuminemia (OR: 2.206 (1.224–3.977), P = 0.008) and visceral obesity (OR: 2.150 (1.170–3.953), P = 0.014) were independent risk factors (Table 5).

Table 3. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis of risk factors for total complications.

Table 4. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis of risk factors for surgical complications.

Table 5. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis of risk factors for medical complications.

The present study revealed that visceral obesity was an independent risk factor for overall, surgical and medical postoperative complications. Also, there was a significant positive association between visceral obesity and the operation of surgery, as the elderly patients with visceral obesity had longer surgical durations and less numbers of lymph nodes harvested. Multiple studies have examined the relationship between visceral obesity and postoperative outcomes. However, there was no study focus on the special population such as elderly population, which was the strength of our study. In addition, we also compared the prognostic value between BMI and visceral obesity. We found that visceral obesity was a better predictor than BMI for postoperative complications in elderly patients after colorectal cancer surgery.

Recently, studies investigating the association between obesity and cancer had demonstrated that it was visceral obesity rather than generalized body fat significantly contributed to poor prognosis in patients with pancreatic cancer (26). A systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated that visceral obesity resulted in higher morbidity, longer surgical time, and lower lymph node retrieval after colorectal cancer surgery (27), which was consistent with our findings. Furthermore, visceral obesity was shown to predict a negative prognosis after other forms of surgery, such as gastrectomy, pancreaticoduodenectomy, and nephrectomy (28–30). These findings indicated that visceral obesity could be a meaningful predictor of postoperative complications. Although previous studies suggested visceral obesity was associated with poor prognosis, the cut-off value for visceral fat area (VFA) has not been clearly defined. Since there is no standardized cut-off value for VFA, some western studies used top sex-specific quartile to define visceral obesity patients (31). Other western studies considered defining visceral obesity with VFA >163.8 cm2 in males and >80.1 cm2 in females as cut points coming from a white population undergoing gastrointestinal resection (32). As the body composition differs from distinct regions, the results of these study may not be applicable to Asian population. In Asians, the most commonly used sex-specific VFA cut-off points are 130 cm² for males and 90 cm² for females (25), which were very different from those used in western studies. Possible reasons for this difference may be different anthropometric and clinical characteristics between Asian and western population. In the present study, we used the latter cut-off value to define visceral obesity.

Excessive visceral fat may result in an increase in pro-inflammatory adipocytokines, such as TNF-α, and IL-6, and in the releases free fatty acids into blood, which would break the balance of the immune reaction (33). During the postoperative period, the poor immune system could lead to an increase in the risk of postoperative complications (34). What’s more, in this study, 74 patients were diagnosed with diabetes, counting for 14% of entire population. Visceral obesity could damage the insulin signaling pathway and be associated with insulin resistance, which would cause infectious complications, especially wound infection (35). Expanded visceral fat, correlated with visceral obesity, elevates the difficulty of surgery, which may increase operative time and blood loss, resulting in higher surgical complications rates (36). Furthermore, elderly patients tend to have multiple comorbidities, which may lead to a worse prognosis. For these reasons mentioned above, elderly patients with visceral obesity easily had poor prognosis.

The results of this study indicated that we cannot ignore the preoperative diagnosis and intervention of visceral obesity in elderly patients with CRC. For surgeons, when making an operation choice, elderly patients with visceral obesity should be more carefully considered. Previous studies concluded that physical exercise is beneficial for preventing abdominal fat accumulation (37, 38). What’s more, a retrospective cohort study reported that increased VFA could cause reduced lung function (39). This finding is in accordance with results presented in this study. In Table 2, it can be noticed that patients in VO group suffered more pulmonary complications than non-VO group. For elderly patients with visceral obesity, exercise therapy prior to colorectal surgery should be widely implemented to improve physical condition and pulmonary function.

In term of lymph nodes harvested, the result of the present study concluded that visceral obesity patients had less number of dissected lymph nodes, while there is no significant differences in the number of positive lymph node. A recent study revealed that visceral obesity patients were less likely to have metastatic lymph nodes involvement in colorectal cancer and gastric cancer (40–42). There may be two explanations for this finding. One hypothesis is that it is more difficult to harvest an appropriate number of lymph nodes in visceral obesity patients because the excessive amounts of intra-abdominal adipose tissue accumulation increased the difficulty of surgery and limited accessibility to some deep lymph nodes. Another possible explanation is distinct microenvironments. Previous studies demonstrated that visceral obesity may create a harsh microenvironment for CRC cells which suppresses the invasion and growth of cancer cells (43). Thus, further studies are needed to validate the relationship between visceral obesity and metastatic lymph node in elderly patients with CRC.

In the present study, hypoalbuminemia, suggesting a poor nutritional status, also proved to be an independent risk factor for overall and medical complications. Due to the low protein intake in the potential malignant process of elderly patients, hypoalbuminemia was frequently observed in elderly patients. A possible mechanism is that hypoalbuminemia is a marker of systemic immunoinflammatory response to surgery, malnutrition, and cancer cachexia. It can be a prognostic tool of postoperative complications (44). Therefore, early identification and intervention in elderly patient with CRC and hypoalbuminemia would reduce the rate of postoperative complications. In addition, hypoproteinemia can be treated with oral nutritional supplements or an intravenous infusion of albumin, which can be a part of pre-rehabilitation program before surgery.

There were several limitations in this study. First, as there were no consensus reference cut-offs of VFA for severe visceral obesity, it was not classified in this study. Second, there was no relevant data for prediabetes or dyslipidaemia. Third, the long-term prognosis was not analyzed in this study. Long-term follow-up data should be collected and analyzed in future studies as the research continues.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that elderly patients with visceral obesity, evaluated by VFA, exhibited a higher rate of postoperative complications after resection for CRC. Moreover, preoperative poorly controlled hypoalbuminemia and visceral obesity were independent risk factors for overall and medical complications. Visceral obesity was an independent risk factor for surgical complications. Therefore, as the population gets older and more susceptible to obesity, visceral obesity can be a clinical predictor for CRC resection in elderly patients.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by The Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

CGX, and XLC conceived and designed the experiments; QTD, HNS and DDH collected the data; WBW, XJR and TTX analyzed and interpreted the data; HNS, QTD and WZC wrote and reviewed the paper; CGX made the decision to submit the article for publication. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study was supported by the Special Fund of Zhejiang Upper Gastrointestinal Tumor Diagnosis and Treatment Technology Research Center (No. jbzx-202006); the clinical nutriology area of the medical support discipline of Zhejiang Province (No. 11-ZC24) and Wenzhou Municipal Science and Technology Bureau (Y20211117).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. (2018) 68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492

2. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fedewa SA, Ahnen DJ, Meester RGS, Barzi A, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. (2017) 67(3):177–93. doi: 10.3322/caac.21395

3. Hermans E, van Schaik PM, Prins HA, Ernst MF, Dautzenberg PJ, Bosscha K. Outcome of colonic surgery in elderly patients with colon cancer. J Oncol. (2010) 2010:865908. doi: 10.1155/2010/865908

4. Bakker IS, Snijders HS, Grossmann I, Karsten TM, Havenga K, Wiggers T. High mortality rates after nonelective colon cancer resection: results of a national audit. Colorectal Dis. (2016) 18(6):612–21. doi: 10.1111/codi.13262

5. Jafari MD, Jafari F, Halabi WJ, Nguyen VQ, Pigazzi A, Carmichael JC, et al. Colorectal cancer resections in the aging US population: a trend toward decreasing rates and improved outcomes. JAMA Surg. (2014) 149(6):557–64. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.4930

6. Webster PJ, Tavangar Ranjbar N, Turner J, El-Sharkawi A, Zhou G, Chitsabesan P. Outcomes following emergency colorectal cancer presentation in the elderly. Colorectal Dis. (2020) 22(12):1924–32. doi: 10.1111/codi.15229

7. Al-Refaie WB, Parsons HM, Habermann EB, Kwaan M, Spencer MP, Henderson WG, et al. Operative outcomes beyond 30-day mortality: colorectal cancer surgery in oldest old. Ann Surg. (2011) 253(5):947–52. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318216f56e

8. Grosso G, Biondi A, Marventano S, Mistretta A, Calabrese G, Basile F. Major postoperative complications and survival for colon cancer elderly patients. BMC Surg. (2012) 12(Suppl 1):S20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-12-S1-S20

9. Feng MA, McMillan DT, Crowell K, Muss H, Nielsen ME, Smith AB. Geriatric assessment in surgical oncology: a systematic review. J Surg Res. (2015) 193(1):265–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.07.004

10. Korc-Grodzicki B, Downey RJ, Shahrokni A, Kingham TP, Patel SG, Audisio RA. Surgical considerations in older adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol. (2014) 32(24):2647–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.0962

11. Montroni I, Saur NM, Shahrokni A, Suwanabol PA, Chesney TR. Surgical considerations for older adults with cancer: a multidimensional, multiphase pathway to improve care. J Clin Oncol. (2021) 39(19):2090–101. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.00143

12. Nam GE, Baek SJ, Choi HB, Han K, Kwak JM, Kim J, et al. Association between abdominal obesity and incident colorectal cancer: a nationwide cohort study in Korea. Cancers (Basel). (2020) 12(6):1368. doi: 10.3390/cancers12061368

13. Tchernof A, Despres JP. Pathophysiology of human visceral obesity: an update. Physiol Rev. (2013) 93(1):359–404. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00033.2011

14. Pecorelli N, Carrara G, De Cobelli F, Cristel G, Damascelli A, Balzano G, et al. Effect of sarcopenia and visceral obesity on mortality and pancreatic fistula following pancreatic cancer surgery. Br J Surg. (2016) 103(4):434–42. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10063

15. Pedrazzani C, Conti C, Zamboni GA, Chincarini M, Turri G, Valdegamberi A, et al. Impact of visceral obesity and sarcobesity on surgical outcomes and recovery after laparoscopic resection for colorectal cancer. Clin Nutr. (2020) 39(12):3763–70. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2020.04.004

16. Chen WZ, Chen XD, Ma LL, Zhang FM, Lin J, Zhuang CL, et al. Impact of visceral obesity and sarcopenia on short-term outcomes after colorectal cancer surgery. Dig Dis Sci. (2018) 63(6):1620–30. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-5019-2

17. Erarslan E, Turkay C, Koktener A, Koca C, Uz B, Bavbek N. Association of visceral fat accumulation and adiponectin levels with colorectal neoplasia. Dig Dis Sci. (2009) 54(4):862–8. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0440-6

18. Lee JY, Lee HS, Lee DC, Chu SH, Jeon JY, Kim NK, et al. Visceral fat accumulation is associated with colorectal cancer in postmenopausal women. PLoS One. (2014) 9(11):e110587. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110587

19. Tsujinaka S, Konishi F, Kawamura YJ, Saito M, Tajima N, Tanaka O, et al. Visceral obesity predicts surgical outcomes after laparoscopic colectomy for sigmoid colon cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. (2008) 51(12):1757–65; discussion 65–7. doi: 10.1007/s10350-008-9395-0

20. Morimoto Y, Takahashi H, Fujii M, Miyoshi N, Uemura M, Matsuda C, et al. Visceral obesity is a preoperative risk factor for postoperative ileus after surgery for colorectal cancer: single-institution retrospective analysis. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. (2019) 3(6):657–66. doi: 10.1002/ags3.12291

21. Moon HG, Ju YT, Jeong CY, Jung EJ, Lee YJ, Hong SC, et al. Visceral obesity may affect oncologic outcome in patients with colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. (2008) 15(7):1918–22. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-9891-4

22. Kondrup J, Allison SP, Elia M, Vellas B, Plauth M, et al. Educational, ESPEN guidelines for nutrition screening 2002. Clin Nutr. (2003) 22(4):415–21. doi: 10.1016/s0261-5614(03)00098-0

23. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. (1987) 40(5):373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

24. Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. (2009) 250(2):187–96. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b13ca2

25. Yamamoto N, Fujii S, Sato T, Oshima T, Rino Y, Kunisaki C, et al. Impact of body mass index and visceral adiposity on outcomes in colorectal cancer. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. (2012) 8(4):337–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-7563.2011.01512.x

26. Kim B, Chung MJ, Park SW, Park JY, Bang S, Park SW, et al. Visceral obesity is associated with poor prognosis in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Nutr Cancer. (2016) 68(2):201–7. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2016.1134600

27. You J, Liu WY, Zhu GQ, Wang OC, Ma RM, Huang GQ, et al. Metabolic syndrome contributes to an increased recurrence risk of non-metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. (2015) 6(23):19880–90. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4166

28. Zhang Y, Wang JP, Wang XL, Tian H, Gao TT, Tang LM, et al. Computed tomography-quantified body composition predicts short-term outcomes after gastrectomy in gastric cancer. Curr Oncol. (2018) 25(5):e411–22. doi: 10.3747/co.25.4014

29. Jang M, Park HW, Huh J, Lee JH, Jeong YK, Nah YW, et al. Predictive value of sarcopenia and visceral obesity for postoperative pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy analyzed on clinically acquired CT and MRI. Eur Radiol. (2019) 29(5):2417–25. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5790-7

30. Zhai T, Zhang B, Qu Z, Chen C. Elevated visceral obesity quantified by CT is associated with adverse postoperative outcome of laparoscopic radical nephrectomy for renal clear cell carcinoma patients. Int Urol Nephrol. (2018) 50(5):845–50. doi: 10.1007/s11255-018-1858-1

31. Cespedes Feliciano EM, Kroenke CH, Meyerhardt JA, Prado CM, Bradshaw PT, Dannenberg AJ, et al. Metabolic dysfunction, obesity, and survival among patients with early-stage colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. (2016) 34(30):3664–71. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.4473

32. Cavagnari MAV, Silva TD, Pereira MAH, Sauer LJ, Shigueoka D, Saad SS, et al. Impact of genetic mutations and nutritional status on the survival of patients with colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. (2019) 19(1):644. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5837-4

33. Harvey AE, Lashinger LM, Hursting SD. The growing challenge of obesity and cancer: an inflammatory issue. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (2011) 1229:45–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06096.x

34. Schrager MA, Metter EJ, Simonsick E, Ble A, Bandinelli S, Lauretani F, et al. Sarcopenic obesity and inflammation in the InCHIANTI study. J Appl Physiol (1985). (2007) 102(3):919–25. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00627.2006

35. Qin L, Wang Z, Tao L, Wang Y. ER stress negatively regulates AKT/TSC/mTOR pathway to enhance autophagy. Autophagy. (2010) 6(2):239–47. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.2.11062

36. Kim KH, Kim MC, Jung GJ, Kim HH. The impact of obesity on LADG for early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. (2006) 9(4):303–7. doi: 10.1007/s10120-006-0395-2

37. Riechman SE, Schoen RE, Weissfeld JL, Thaete FL, Kriska AM. Association of physical activity and visceral adipose tissue in older women and men. Obes Res. (2002) 10(10):1065–73. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.144

38. Winters-van Eekelen E, van der Velde J, Boone SC, Westgate K, Brage S, Lamb HJ, et al. Objectively measured physical activity and body fatness: associations with total body fat, visceral fat, and liver fat. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2021) 53(11):2309–17. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002712

39. Choe EK, Kang HY, Lee Y, Choi SH, Kim HJ, Kim JS. The longitudinal association between changes in lung function and changes in abdominal visceral obesity in Korean non-smokers. PLoS One. (2018) 13(2):e0193516. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193516

40. Park SW, Lee HL, Doo EY, Lee KN, Jun DW, Lee OY, et al. Visceral obesity predicts fewer lymph node metastases and better overall survival in colon cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. (2015) 19(8):1513–21. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-2834-z

41. Park SW, Lee HL, Ju YW, Jun DW, Lee OY, Han DS, et al. Inverse association between visceral obesity and lymph node metastasis in gastric cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. (2015) 19(2):242–50. doi: 10.1007/s11605-014-2682-2

42. Magnuson AM, Fouts JK, Regan DP, Booth AD, Dow SW, Foster MT. Adipose tissue extrinsic factor: obesity-induced inflammation and the role of the visceral lymph node. Physiol Behav. (2018) 190:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2018.02.044

43. Spychalski P, Kobiela J, Wieszczy P, Kaminski MF, Regula J. Clinical stages of colorectal cancer diagnosed in obese and overweight individuals in the Polish Colonoscopy Screening Program. United European Gastroenterol J. (2019) 7(6):790–7. doi: 10.1177/2050640619840451

Keywords: colorectal cancer, elderly patients, postoperative complication, visceral obesity, risk factor

Citation: Dong Q, Song H, Chen W, Wang W, Ruan X, Xie T, Huang D, Chen X and Xing C (2022) The Association Between Visceral Obesity and Postoperative Outcomes in Elderly Patients With Colorectal Cancer. Front. Surg. 9:827481. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2022.827481

Received: 2 December 2021; Accepted: 17 May 2022;

Published: 6 June 2022.

Edited by:

Andrew Gumbs, Centre Hospitalier Intercommunal de Poissy, FranceReviewed by:

Manana Gogol, Grigol Robakidze University, GeorgiaCopyright © 2022 Dong, Song, Chen, Wang, Ruan, Xie, Huang, Chen and Xing. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chungen Xing eGluZ2NnQHN1ZGEuZWR1LmNu

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and are co-first authors on this work

Specialty section: This article was submitted to Visceral Surgery, a section of the journal Frontiers in Surgery

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.