- 1Department of Orthopedics, People's Hospital of Pan'an County, Jinhua, China

- 2Department of Orthopedics, Xuzhou Central Hospital, Xuzhou, China

- 3Department of Orthopedic Surgery, The Second Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou, China

- 4Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Ningbo No.6 Hospital, Ningbo, China

Purpose: Gastrointestinal neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) with bone metastasis is rarely reported. The purpose of this study is to explore the prognosis and risk factors of such patients.

Patients and Methods: We retrospectively reviewed patients diagnosed as gastrointestinal NECs with bone metastasis at diagnosis from 2010 to 2016 by using the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database. Predictors of overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS) were analyzed by univariable and multivariable Cox analyses. Kaplan–Meier plots were constructed to show the correlation between independent predictors and survival.

Results: A total of 330 gastrointestinal NEC patients with bone metastasis at diagnosis were included for analysis. Over half of patients were male and older than 60 years old. The most common primary site of gastrointestinal NEC with bone metastasis was the pancreas. The prognosis of gastrointestinal NEC with bone metastasis (3-year OS and CSS rates: 16.7 and 17.0%) was very poor. On Cox multivariable analysis, age over 60 years old, no surgery, and lung metastasis were independent predictors of decreased OS and CSS.

Conclusions: We identified three independent factors associated with prognosis among gastrointestinal NEC patients with bone metastasis, namely age, surgery, and lung metastasis. For younger gastrointestinal NEC patients with bone metastasis, surgical resection of primary tumors as well as actively treating lung metastasis might be useful for prolonging survival.

Introduction

Neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) is a poorly differentiated subtype of neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) according to the 2019 World Health Organization (WHO) classification (1). Although NECs are commonly considered as rare, they have a rising incidence in recent years (2–4). NECs are characterized by poorly differentiated morphology as well as a high proliferation capacity (Ki−67 proliferation index > 20%) (5). Moreover, NECs are often presented with metastasis at diagnosis or advanced status and have a poor prognosis (6–8). Lung is the common site of NECs, while gastrointestinal NECs are rarely seen and account for about 35–55% of all extra-pulmonary NECs (9). Gastrointestinal NECs mainly arise from the esophagus, stomach, pancreas, colon and rectum and common metastatic sites for NECs include liver, lung and bone (8, 10).

Various treatment options are available for curative and palliative treatment of gastrointestinal NECs, including surgical resection, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy (11). However, treatment outcomes of gastrointestinal NECs remain poor (12). Due to the rarity of gastrointestinal NECs, there are limited researches regarding the treatment and survival of metastatic gastrointestinal NECs. As far as we know, clinical studies on survival analysis of gastrointestinal NECs with bone metastasis are lacking. Therefore, we conducted a population-based study by applying the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database to investigate the clinical characteristics and prognostic factors for gastrointestinal NECs with bone metastasis. Our findings may bring insight into gastrointestinal NECs with bone metastasis and provide a survival benefit on survival.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

This study retrospectively reviewed patients diagnosed as gastrointestinal NECs with bone metastasis at presentation by using the U.S National Cancer Institute's SEER database (Version 8.3.8) between 2010 and 2016. This population-based database collects information on cancer patients in 18 registries, covering approximately 30% of cancer cases in the U.S (www.seer.cancer.gov). Ethical review is not required for the present study because the public database does not contain information to identify patients.

Histological types were defined by the following International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd edition (ICD-O-3) code 8246/3 (neuroendocrine carcinoma, NOS). The primary sites were defined, including the esophagus, stomach, liver, pancreas, small intestine, cecum, appendix, colon, rectum, anus, gallbladder, biliary tract and other GI sites. Cases diagnosed not by histopathological examinations were excluded. In the present study, clinicopathological data, sociological data and treatment data were included for analysis. Surgery or radiotherapy in this study refers to the primary sites (13). Based on previous literature (14, 15), overall survival (OS) and cancer specific survival (CSS) are defined as the time from initial diagnosis to death due to any cause and NEC, respectively.

Statistical Methods

All statistical analyses were performed by using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 22). First, univariable Cox regression analyses were performed to select significant survival predictors. Then, significant risk factors from univariable analyses were integrated into multivariate Cox regression analysis to identify independent risk factors. Meanwhile, hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Survival curves of independent risk factors were constructed with the Kaplan-Meier method. Variables with two-tailed p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients Characteristics

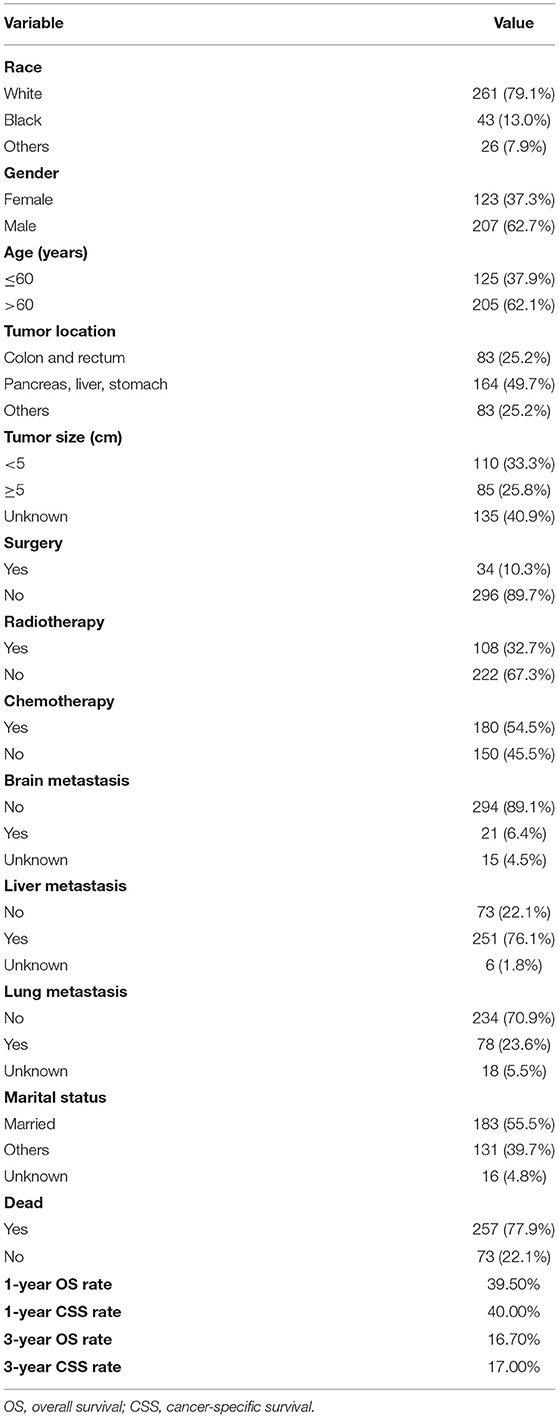

In total, 330 patients with gastrointestinal NEC and bone metastasis at diagnosis extracted from the SEER database were eligible for the analysis. Table 1 summarized the demographics of all patients. Of all patients, 79.1% were white and 62.7% were males. Over half of patients (62.1%) were aged over 60 years old. 25.2% (n = 83) of patients were located in the colon and rectum, 49.7% (n = 164) of patients were located in the pancreas, liver, stomach, and 18.31% of patients (n = 63) were located in other sites. Tumor size distribution was <5 cm 33.3%, ≥5 cm 25.8%, and unknown 40.9%. In terms of treatment methods, 34 (10.3%) patients received surgery, 108 (32.7%) received radiotherapy, and 180 (54.5%) received chemotherapy. Liver metastasis (76.1%) was more common than brain metastasis (6.4%) or lung metastasis (23.6%). Over half of the patients (55.5%) were married. One-year OS and CSS rate for all patients were 39.5 and 40%, respectively.

Table 1. Demographics of 330 gastrointestinal neuroendocrine carcinoma with bone metastasis at diagnosis.

Survival Analysis

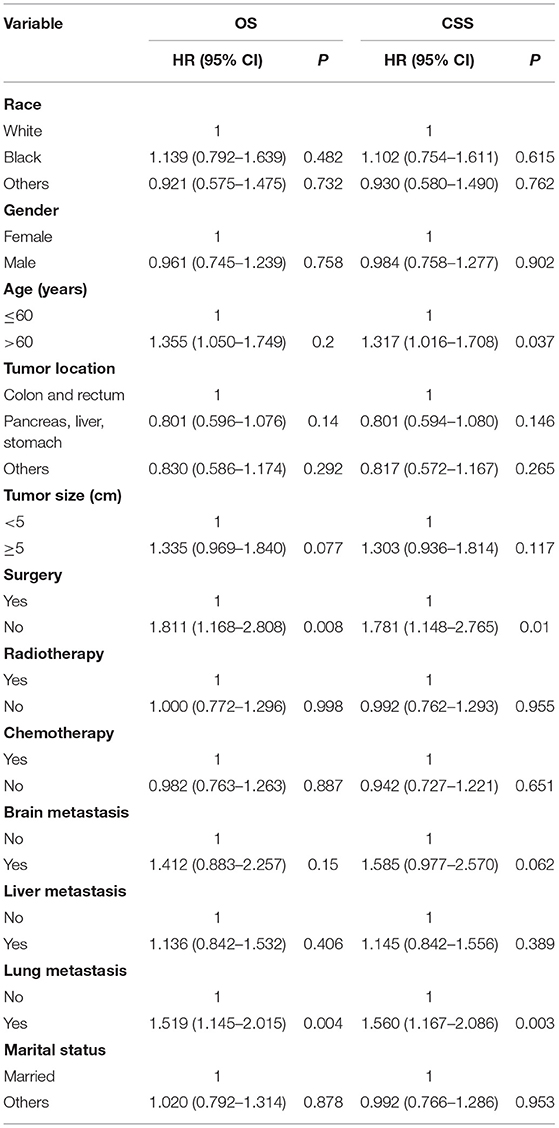

On univariable analysis, variables found to be significantly associated with both OS and CSS were age, surgery, and lung metastasis (Table 2). There was no significant difference in OS or CSS in terms of race, gender, tumor location, tumor size, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, brain metastasis, liver metastasis, and marital status (Table 2).

Table 2. Univariate Cox analysis of survival in gastrointestinal neuroendocrine carcinoma with bone metastasis.

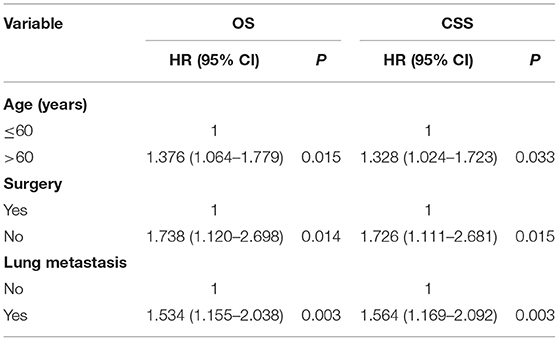

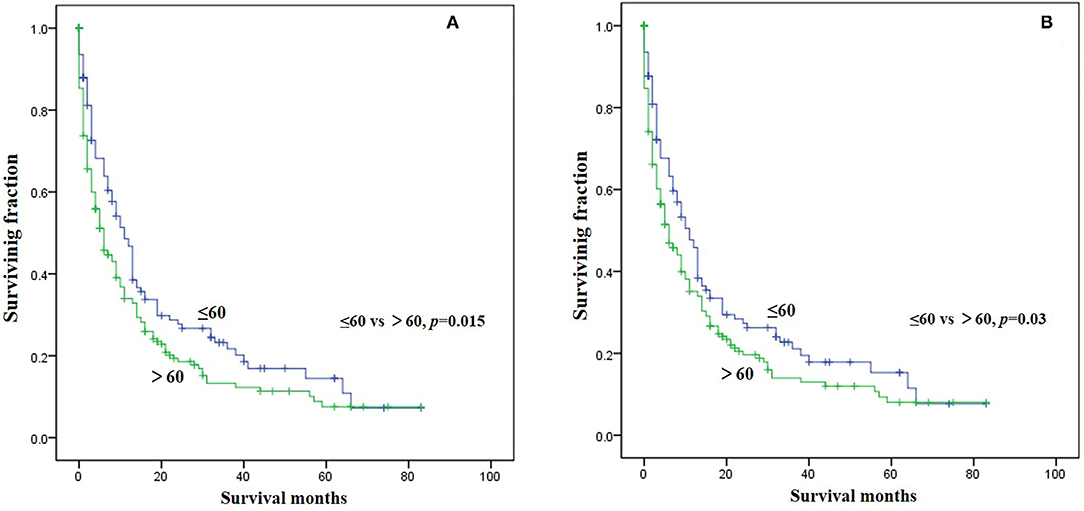

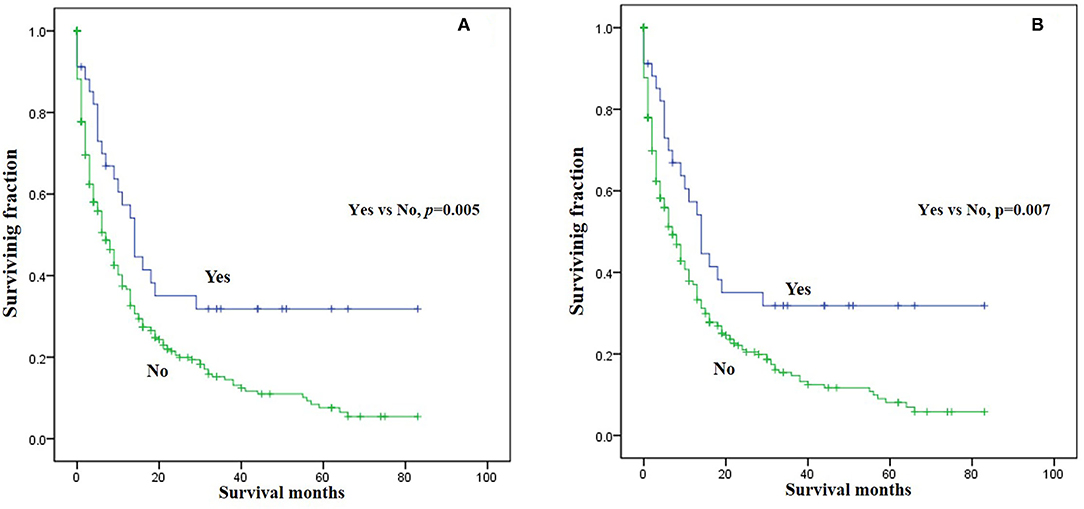

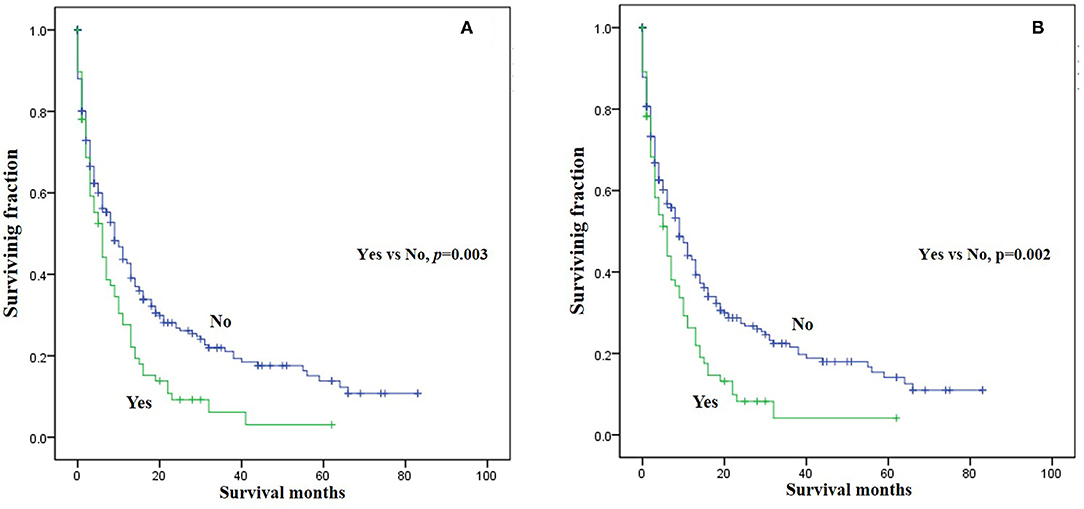

Three significant risk factors for OS and CSS identified in the univariable Cox analysis were integrated into the multivariable analysis. Multivariable analysis revealed age, surgery, and lung metastasis were significant predictors for both OS and CSS (Table 3). Additionally, the Kaplan–Meier survival curves showed that patients with age ≤60 years old (Figure 1), surgery (Figure 2), or no lung metastasis (Figure 3), had increased OS and CSS.

Table 3. Multivariate Cox regression analysis of survival in gastrointestinal neuroendocrine carcinoma with bone metastasis.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier method estimated survival in gastrointestinal NEC with bone metastasis at diagnosis stratified by age. (A) OS, (B) CSS (OS, overall survival; CSS, cancer-specific survival).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier method estimated survival in gastrointestinal NEC with bone metastasis at diagnosis stratified by surgery. (A) OS, (B) CSS (OS, overall survival; CSS, cancer-specific survival).

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier method estimated survival in gastrointestinal NEC with bone metastasis at diagnosis stratified by lung metastasis. (A) OS, (B) CSS (OS, overall survival; CSS, cancer-specific survival).

Discussion

Previous studies indicated that NEC patients were prone to metastasis. Although some studies reported the prognosis of gastrointestinal NEC, few studies have been conducted on the prognosis of gastrointestinal NEC with bone metastasis. To our knowledge, this is the largest study investigating the clinical characteristics, and prognosis of gastrointestinal NEC patients with bone metastasis. The 3-year CSS rate of these patients was only 17%, which suggested a poor outcome. Moreover, significant independent predictors affecting gastrointestinal NEC with bone metastasis included age, lung metastasis, and surgery. The results of this study may help clinicians develop appropriate treatment strategies and provide reasonable treatment suggestions for patients.

No significant difference on survival was observed in univariate analysis among patients with different races. Interestingly, some studies on lung neuroendocrine neoplasms revealed race was an independent survival predictor (16, 17). Patients over 60 years old are generally considered the elderly. Based on previous literature (18, 19), we divided the patients' age into >60 years old and ≤60 years old for convenient analysis. Multivariate analysis revealed that age under 60 years were associated with improved OS and CSS, which was in line with previous studies (20–22). There is no significant difference in survival time between male and female patients. The most common primary site of gastrointestinal NEC with bone metastasis was the pancreas. Additionally, no significant difference was observed in OS and CSS among patients with different primary tumor locations. Based on previous literature (23, 24), we divided the tumor size into ≥5 cm and <5 cm for convenient analysis. For many primary malignant tumors, tumor size is often one of the important factors affecting the prognosis of patients (25, 26). In contrast to our traditional knowledge, we noted that tumor size in the current study was not correlated with survival. Further studies are needed to confirm this finding.

Treatment patterns and outcomes of gastrointestinal NEC patients especially metastatic ones have not been well-described. Our multivariable results highlighted the role of surgical resection in prolonging the survival, which was consistent with the situation of non-metastatic patients (12). Sorbye et al. (9) recommended that chemotherapy treatment should be performed for advanced gastrointestinal NEC patients. However, our studies found that chemotherapy or radiotherapy did not improve the prognosis of those patients. Although liver metastasis was most common in gastrointestinal NEC patients with bone metastasis, it was not an independent risk factor for prognosis. Additionally, the presence of brain metastasis was not associated with a decreased survival. Of note, these patients were secondly complicated with lung metastasis, which was recognized as an independent risk factor for the decreased prognosis. Therefore, actively treating lung metastasis may have positive effect on survival. Marital status had no association with survival in this study. In accordance with these findings, we suggested that for younger gastrointestinal NEC patients with bone metastasis, surgical resection of primary tumors as well as actively treating lung metastasis might be useful for prolonging survival.

Some limitations of the present study should be noted. First, this study has retrospective nature, which can lead to bias. Second, detailed therapy information is not available in the database. Third, local recurrence or distal metastasis data during follow-up were not recorded in the database. Additionally, due to the small sample size and few independent risk factors in this study, we did not build a prediction model. Future studies can attempt to build predictive models. Although this study has these limitations, it has important implications for managing these patients.

Conclusions

This is the largest study of survival analysis on gastrointestinal NEC patients with bone metastasis. Age, surgery and lung metastasis were identified as independent risk factors of survival. Resection of primary tumors as well as actively treating lung metastasis can prolong the survival of this special cohort. However, multicenter co-operative studies should be performed to confirm our findings in the future.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

SW and ZW conceived and designed the study. GC, QX, and SQ collected the data. GC, QX, and SQ performed the statistical analysis. GC wrote the manuscript and SW and ZW revised it. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2021M692792), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82103499), and Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation (LQ22H160040).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Shi H, Qi C, Meng L, Yao H, Jiang C, Fan M, et al. Do neuroendocrine carcinomas and mixed neuroendocrine-non-neuroendocrine neoplasm of the gastrointestinal tract have the same prognosis? A SEER database analysis of 12,878 cases. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metabol. (2020) 11:2042018820938304. doi: 10.1177/2042018820938304

2. Yao JC, Hassan M, Phan A, Dagohoy C, Leary C, Mares JE, et al. One hundred years after “carcinoid”: epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. J Clin Oncol. (2008) 26:3063–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4377

3. Korse CM, Taal BG, van Velthuysen ML, Visser O. Incidence and survival of neuroendocrine tumours in the Netherlands according to histological grade: experience of two decades of cancer registry. Eur J Cancer. (2013) 49:1975–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.12.022

4. Dasari A, Shen C, Halperin D, Zhao B, Zhou S, Xu Y, et al. Trends in the incidence, prevalence, and survival outcomes in patients with neuroendocrine tumors in the United States. JAMA Oncol. (2017) 3:1335–42. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0589

5. Pellat A, Cottereau AS, Terris B, Coriat R. Neuroendocrine carcinomas of the digestive tract: what is new? Cancers. (2021) 13:3766. doi: 10.3390/cancers13153766

6. Wang Z, Li W, Chen T, Yang J, Luo L, Zhang L, et al. Retrospective analysis of the clinicopathological characteristics of gastrointestinal neuroendocrine neoplasms. Exp Ther Med. (2015) 10:1084–8. doi: 10.3892/etm.2015.2634

7. Koumarianou A, Chatzellis E, Boutzios G, Tsavaris N, Kaltsas G. Current concepts in the diagnosis and management of poorly differentiated gastrointestinal neuroendocrine carcinomas. Endokrynol Polska. (2013) 64:60–72.

8. Cai W, Tan Y, Ge W, Ding K, Hu H. Pattern and risk factors for distant metastases in gastrointestinal neuroendocrine neoplasms: a population-based study. Cancer Med. (2018) 7:2699–709. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1507

9. Sorbye H, Welin S, Langer SW, Vestermark LW, Holt N, Osterlund P, et al. Predictive and prognostic factors for treatment and survival in 305 patients with advanced gastrointestinal neuroendocrine carcinoma (WHO G3): the NORDIC NEC study. Ann Oncol. (2013) 24:152–60. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds276

10. Lokesh KN, Anand A, Lakshmaiah KC, Babu KG, Lokanatha D, Jacob LA, et al. Clinical profile and treatment outcomes of metastatic neuroendocrine carcinoma: a single institution experience. South Asian J Cancer. (2018) 7:207–9. doi: 10.4103/sajc.sajc_176_17

11. Morita M, Taguchi K, Kagawa M, Nakanoko T, Uehara H, Sugiyama M, et al. Treatment strategies for neuroendocrine carcinoma of the upper digestive tract. Int J Clin Oncol. (2020) 25:842–50. doi: 10.1007/s10147-020-01631-y

12. Fang C, Wang W, Zhang Y, Feng X, Sun J, Zeng Y, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics and prognosis of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: a multicenter study in South China. Chin J Cancer. (2017) 36:51. doi: 10.1186/s40880-017-0218-3

13. Wang Z, Cheng Y, Chen S, Shao H, Chen X, Wang Z, et al. Novel prognostic nomograms for female patients with breast cancer and bone metastasis at presentation. Ann Transl Med. (2020) 8:197. doi: 10.21037/atm.2020.01.37

14. Wang Z, Wu B, Zhou Y, Huang X, Pan W, Liu M, et al. Predictors of the survival of primary and secondary older osteosarcoma patients. J Cancer. (2019) 10:4614–22. doi: 10.7150/jca.32627

15. Wang Z, Li S, Li Y, Lin N, Huang X, Liu M, et al. Prognostic factors for survival among patients with primary bone sarcomas of small bones. Cancer Manag Res. (2018) 10:1191–9. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S163229

16. Yang Q, Xu Z, Chen X, Zheng L, Yu Y, Zhao X, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics and prognostic factors of pulmonary large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma: a large population-based analysis. Thoracic Cancer. (2019) 10:751–60. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.12993

17. Shah S, Gosain R, Groman A, Gosain R, Dasari A, Halfdanarson TR, et al. Incidence and survival outcomes in patients with lung neuroendocrine neoplasms in the United States. Cancers. (2021) 13:1753. doi: 10.3390/cancers13081753

18. Liu D, Wu J, Lin C, Andriani L, Ding S, Shen K, et al. Breast subtypes and prognosis of breast cancer patients with initial bone metastasis: a population-based study. Front Oncol. (2020) 10:580112. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.580112

19. Lin F, Duan J, Lin Y, Wu H, Xu G, Guo X, et al. Survival and risk factors in patients with liposarcoma with distant metastasis. Am J Transl Res. (2020) 12:2071–82.

20. Alese OB, Jiang R, Shaib W, Wu C, Akce M, Behera M, et al. High-grade gastrointestinal neuroendocrine carcinoma management and outcomes: a national cancer database study. Oncologist. (2019) 24:911–20. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0382

21. Yuan G, Zhan C, Zhu D, Xie H, Wei T, Lu T, et al. Population-based analysis of esophageal large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma between 2004 and 2015. J Thoracic Dis. (2019) 11:5480–8. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2019.11.34

22. Russolillo N, Vigano L, Razzore P, Langella S, Motta M, Bertuzzo F, et al. Survival prognostic factors of gastro-enteric-pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors after primary tumor resection in a single tertiary center: comparison of gastro-enteric and pancreatic locations. Eur J Surg Oncol. (2015) 41:751–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2015.02.011

23. Cao L, Zhao L, Wang M, Zhang XH, Yang ZC, Liu YP. Clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of pulmonary large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma aged ≥65 years. PeerJ. (2019) 7:e6824. doi: 10.7717/peerj.6824

24. Xu B, Chu Y, Hu Q, Song Q. The clinicopathological features and overall survival of patients with gastric neuroendocrine carcinoma. Technol Cancer Res Treat. (2021) 20:15330338211055340. doi: 10.1177/15330338211055340

25. Zhang Y, Wu Z, Wang X, Li C, Chang J, Jiang W, et al. Development and external validation of a nomogram for predicting the effect of tumor size on survival of patients with perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. BMC Cancer. (2020) 20:1044. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-07501-0

Keywords: gastrointestinal, neuroendocrine carcinoma, bone metastasis, survival, risk factors

Citation: Chen G, Xu Q, Qian S, Wang Z and Wang S (2022) Survival Analysis in Gastrointestinal Neuroendocrine Carcinoma With Bone Metastasis at Diagnosis. Front. Surg. 9:820725. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2022.820725

Received: 23 November 2021; Accepted: 03 January 2022;

Published: 28 January 2022.

Edited by:

Sanjit Mukherjee, National Institutes of Health (NIH), United StatesReviewed by:

Jun-Gang Zhang, Zhejiang Provincial People's Hospital, ChinaAbhisek Bhattacharya, National Institutes of Health (NIH), United States

Copyright © 2022 Chen, Xu, Qian, Wang and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhan Wang, wangzhanhz@zju.edu.cn; Shicheng Wang, woson004@gmail.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Genlian Chen1†

Genlian Chen1† Zhan Wang

Zhan Wang