95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Sports Act. Living , 24 March 2025

Sec. Sports Coaching: Performance and Development

Volume 7 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2025.1515200

This article is part of the Research Topic Environmental Determinants of Athletes’ Development and Performance View all 3 articles

This research aims to investigate the significant experiences of adolescent athletes in competitive sports activities and their development through the available literature. This study systematically reviews research on adolescent athletes participating in competitive sports over the past 10 years. We evaluated and reported 19 studies in four sections: sample characteristics, research design, significant experiences, and key findings related to the development of adolescent athletes. This study includes adolescent athletes who participate in various sports and pursue careers in organized and competitive sports using qualitative and mixed methods designs. This study employs a systematic literature review as its research method. The initial online search was conducted in April 2023 and updated on January 2025 on electronic databases: Web of Science (WoS), PubMed, and Scopus. The process of searching for articles used the PRISMA guidelines proposed by Moher. We synthesized and interpreted the findings in each article. The main findings of this study lead to three main themes: meaningful experiences for adolescents, barriers in the development of adolescent athletes, and that influencing athlete development. This study concludes that working with adolescent athletes requires attention to unseen factors to ensure that they are in a supportive environment that encourages their positive development into elite athletes in the future.

There is much dispute and complexity in understanding competitive sports in adolescents. Literature (1) explains that, on the surface, adolescents appear healthy and happy, with families reporting higher satisfaction levels when adolescents participate. On the other hand, competitive sports with pressure to win can damage the psychological and mental health of adolescents, not to mention the constant threat of injury and the high costs associated with participation in competitions. Competitive and organized sports, in many cases, aim to be a step towards Olympic elite sports or professional sports through increased competitiveness and professionalization (2). This trend confirms the increasing professionalization and specialization in youth sports, aiming to maximize the identification and development of talent for advancement to elite sports, a striking trend with potential physical and psychological consequences (3). The widely adopted trend of professionalization in youth sports training has generated various speculations (4–6). A survey estimates that 63.1% of Australian youth participate in organized sports (7). Thus, organized sports programs hold a legitimate place in Australian culture and have a significant role in youth development (8). In addition, millions of children around the world participate in community, school, and private sports programs (9).

Organized sports play an important role in the development of children and adolescents today. It has been proposed that sports can be an important mechanism for facilitating growth and well-being in young people (10). This is primarily because sports involve elements generally proven to positively affect mental health, such as physical activity and social engagement. In a systematic review in 2013, Eime and colleagues found many psychological and social health benefits from sports participation for young people, including increased self-esteem, social interaction, and reduced symptoms of depression (11). The physical and psychosocial benefits of involvement in sports are well recognized (12). This is reinforced by meta-analysis findings that show adolescents involved in sports report fewer symptoms of depression and anxiety-based symptoms compared to those who do not participate in sports. However, the effects are minor (13).

Unfortunately, adolescent athletes face competitive demands that can increase vulnerability to symptoms and mental health disorders during a developmental period or puberty, which is already challenging with emotional, cognitive, and behavioral changes (14, 15). Based on the mental health survey, also known as the Young Minds Matter Survey, conducted in Australia in (2013–14), it was reported that 14% of all children and adolescents (aged 4–17 years) experienced mental health disorders in the previous 12 months (8, 15). Common mental health disorders among adolescents include attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, depression, and anxiety (15, 16), and half of all mental health disorders occur during adolescence (16). Demands and competitive pressures are placed on adolescent athletes to perform at high standards in organized sports, while adolescent athletes also experience stressful developmental periods during puberty (17). Adolescent athletes experience frequent mood swings and fluctuating training performance (17–19). Adolescent athletes also experience fatigue from intensive training conducted almost year-round (20), and stress negatively impacts their physical and mental conditions (21, 22), which in turn can lead to injuries (22–24). Young athletes are often less prepared to face challenging issues in organized or competitive sports (25, 26). As a result, many young athletes choose to drop out of competitive sports and opt not to continue their participation.

Research has shown that adolescent athletes have various positive and negative impacts from their participation, but the contribution of social support is often overlooked. How do adolescent athletes interpret their experiences in competitive sports activities in their development? The research findings indicate that the experiences of adolescent athletes are influenced by support from their social networks, such as demonstrating resilience during difficult times (25, 27, 28). Therefore, adolescent athletes need to receive adequate support in their sports and from the social networks around them to minimize the negative impact on their long-term health, well-being, and performance (29, 30). Participation in sports contributes to self-confidence through encouragement, self-talk, and successful performance (31, 32). Thus, successful performance at the elite level inevitably develops athletes’ self-confidence and their ability to manage emotions under pressure, influenced by their social environment (32). However, much of the literature on youth sports highlights the reasons for discontinuing training in competitive sports (33–36) from various perspectives of social support.

Thus, although several reviews broadly discuss this area, for example (37–40), to our knowledge, a review specifically focusing on adolescent athletes exploring experiences qualitatively and influencing their development in competitive sports is needed by synthesizing and uncovering the essence of the existing literature. This article presents the results of a systematic review that investigates the significant experiences of adolescent athletes in competitive sports activities in their development. Then, the information obtained from the systematic review is used to develop a conceptual model of adolescent athletes in competitive sports life. The conclusions of our review will be directly relevant to those working in competitive sports environments for adolescents.

The research utilized a systematic literature review method, as outlined in study (41). This approach followed the principles of a systematic literature review with a descriptive qualitative design, aligned with the research questions, to explore the body of publications on a specific topic based on existing literature.

The search strategy was developed through consultation among co-authors with expertise in youth sports. H.P.R, a seasoned journal editor with expertise in systematic searches, took the lead in performing searches across databases and organizing the articles for review. The initial online search was carried out in April 2023 and updated on January 2025, using electronic databases such as Web of Science (WoS), PubMed, and Scopus, which are among the most comprehensive academic search engines (42). The article search process followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (43, 44). Furthermore, the findings in each article were evaluated and interpreted (45).

The purpose of this research was to understand how adolescent athletes interpret their experiences in competitive sports, including psychological, social, and cultural aspects. Therefore, the search equation was designed to encompass concepts such as the meaning of experience, the identity of adolescent athletes, and the impact of competitive sports. Several key terms relevant to the research theme include: (a) Adolescent athlete: “youth athlete,” “adolescent athlete,” “young athlete,” “junior” (b) Meaning of experience: “meaning,” “perception,” “experience,” “identity” (c) Competitive sports: “competitive sports,” “elite sports,” “high-performance sports,” “Sport Achievement”. Search queries used Boolean operators such as “AND” and “OR” to ensure the search results were relevant and specific. These search terms included: (“youth athlete” OR “adolescent athlete” OR “young athlete” OR “junior”) AND (“meaning” OR “perception” OR “experience” OR “identity” OR “life”) AND (“competitive sports” OR “elite sports” OR “high-performance sports” OR “sports achievement”).

The design followed the PICOS strategy, which defined participants, intervention, outcome, and study design. We defined the inclusion and exclusion criteria in the PICOS table, which can be seen in (Table 1). The research results chapter grouped all article findings relevant to the research theme, namely adolescent athletes in competitive sports, into specific field categories.

Studies retrieved from each database were initially exported to Microsoft Excel. Duplications were carefully checked and flagged for exclusion on subsequent Excel tab sheets. Two authors (H.P.R. and A.K.) were tasked with independently selecting studies by reading the title and abstract, followed by the full text, and identifying systematic reviews that met the eligibility criteria. Discrepancies regarding study inclusion were discussed and resolved by consensus with the author (M.F.D.). A manual search in the references of the selected articles used the same eligibility criteria as the studies obtained from the electronic database search.

The initial search using Boolean operators and relevant keywords across electronic databases yielded a total of 367 articles. Two authors, H.P.R. and A.K., extracted data based on key characteristics of each study. They organized the information into columns: author, publication year, article title, journal, database searched, study purpose, and methodology. The extraction process was carried out methodically and carefully. In the end, 19 articles were selected that met the inclusion criteria. A comprehensive summary of the study characteristics, including sample details, research methods, and key findings, is provided in (Table 2).

These articles were then subjected to further synthesis in order to facilitate an investigation of the pivotal findings emanating from the research. In the subsequent analysis, we identified significant findings that would guide the researcher in developing the research theme, as illustrated in the table below: (i) Author, year (ii) Sample characteristics (iii) Type of sport, (iv) Research objectives (v) Research design (vi) Important findings (vii) Research themes. Data was input according to the table columns provided.

The initial step in determining the theme of each article was based on its main findings. These findings were carefully reviewed multiple times until the content was fully understood. The interpretation of these findings was then used to derive a major theme of the article. At this stage, the themes were not categorized or grouped but were formed freely based on the author's in-depth understanding. Subsequently, the main themes of the articles were organized into similar categories, leading to three research themes: obstacles, meaning, and development. These themes were color-coded (yellow for meaning, red for barriers, green for athlete development) to aid in the grouping process.

We then synthesized the key research findings from each article within the same thematic group. At this stage, we simplified the key findings and provided conclusions for each article. After that, we grouped each simplified conclusion into a table with intersections or closeness of meaning. Finally, we pulled the key findings back into the subordinate themes and gave them meaning and appropriate descriptions. For a clearer understanding of the data synthesis process, see an example of the analysis of the theme The meaning of competitive sports for adolescents (Table 3).

The risk of bias and methodological quality of the included studies were assessed independently by two authors with an understanding of adolescent athletes (C.S. and H.S.) using Risk of Bias Assessments. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (A.K). We adopted the risk of bias assessment for the study, a systematic review of talent assessment in sports (46), and the methodological quality of the included studies using the critical appraisal for qualitative studies (containing 21 items) (47). Each qualitative article is evaluated based on the following 21 items: objectives (item 1), literature review (item 2), study design (items 3, 4, and 5), sampling (items 6, 7, 8, and 9), data collection (descriptive clarity: items 10, 11, and 12; procedural rigor: item 13), data analysis (analytical rigor: items 14 and 15; audibility: items 16 and 17; theoretical connection: item 18), overall rigor (item 19), and conclusion/implications (items 20 and 21). The results per item are coded as 1 (meets the criteria), 0 (does not fully meet the criteria), or NA (not applicable). The final score expressed in relative value is reported for each study following the assessment guidelines (46). The final score is the total of all scores for specific items divided by the total number of items assessed for that specific research project (i.e., 21 items). Classification of articles as (1) low methodological quality - with a score <50%; (2) good methodological quality—score between 51% and 75%; and (3) very good methodological quality—with a score > 75%.

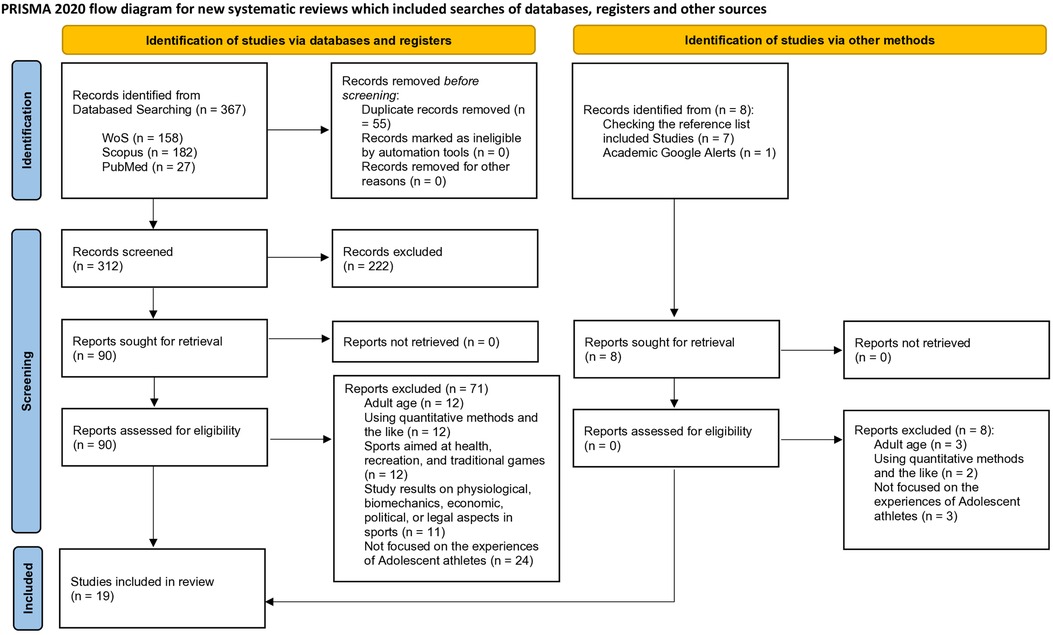

The research team examined an initial set of 367 articles generated by the search engine: Web of Science (WoS) = 158, Scopus = 182, PubMed = 27. The initial screening identified 55 disqualified articles consisting of duplicate files, resulting in 312 articles to be re-selected. From the 312 articles, our team conducted a re-screening by examining the relevance of the title to the research topic, the article's completeness, the year of publication, and the article's eligibility. The result was that 222 were excluded, leaving 90 articles included. The report was assessed for eligibility, and 90 articles met the criteria for full-text analysis. All important information from the articles in Microsoft Excel includes the author, publication year, title, journal, objective, method, participants, research objective, and results.

The result was that 71 articles were excluded for the following reasons; twelve (12) articles have participants who have reached adulthood, as many as twelve (12) articles use quantitative methods or questionnaires and the like that do not capture the meaning and experience of participants, as many as twelve (12) articles discuss health sports, recreation, and traditional games, fifteen (15) of his research articles focus on health, biomechanics, and physical, twenty (20) articles do not focus on exploring teenagers’ experiences or being adolescent athletes.

From a rigorous selection process, 19 articles were included. All included articles were eligible for analysis and synthesis as they met the criteria of: having adolescent participants, using qualitative methods with an emphasis on meaning and immersive experiences, including competitive and organized sports, research findings on the psychological and social environment of being an adolescent athlete, and lastly focusing on the experience of being an adolescent athlete or during being an adolescent athlete. The PRISMA flowchart summarizes the details of all study options (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart illustrating the screening process. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram showing number of reports collected and number of eligible studies after the screening process.

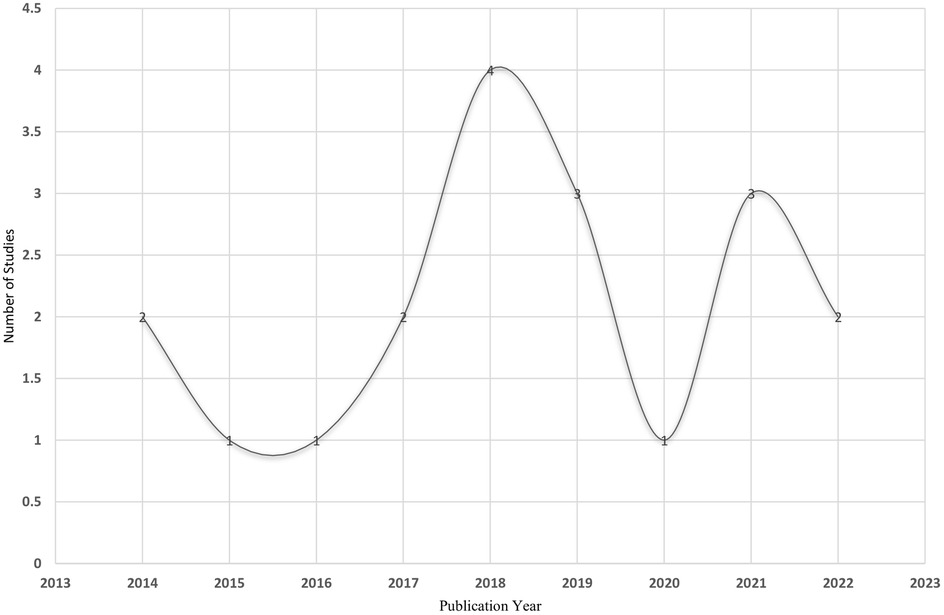

The results risk of bias assessment of the research methodology quality of the 19 included qualitative studies is as follows: (1) the average score for the 19 included qualitative studies is 96.0%; (2) 9 articles achieved a maximum score of 100%; (3) no publication received a score below 75%. The results of the bias risk assessment of the included review are presented in (Table 4). Figure 2 illustrates the publication year profile of the studies. Of the included studies, 13 (68.4%) were published within the 5 years between 2018 and 2023. The remaining publications on the experiences of adolescent athletes in competitive sports consistently only range from 1 study (2015, 2016) to 2 studies (2014, 2007).

Figure 2. The number of studies on significant experiences of adolescent athletes based on the year of publication.

As shown in the data description results (Table 5), this study is specifically aimed at examining the experiences of adolescent athletes in competitive sports life, with participants generally under 18 years old, totaling 14 (74%). In contrast, 5 (26%) adult participants are former athletes reflecting on their experiences as adolescent athletes. Because the emphasis is on the experiences and meanings encountered, this study predominantly used qualitative methods, with 15 (79%) employing qualitative research and 4 (21%) using a mixed-method approach. All the sports included are organized competitive sports with a wide variety of types; there are 6 (31.6%) team or group types, 6 (31.6%) individual types, and 7 (36.8%) a mix of individual and group types. This research yields significant experiences of adolescent athletes in competitive sports activities in their development through literature that includes (19 studies), divided into three themes. First, a depiction of the most meaningful experiences provided by adolescent athletes at every moment of their journey in competitive sports was presented in a study of 6 (31.5%). Second, a review of negative experiences that hindered adolescent athletes in competitive sports was examined by several 6 studies (31.5%). Third, positive experiences that influence athlete development were reviewed with a total of 8 studies (37%).

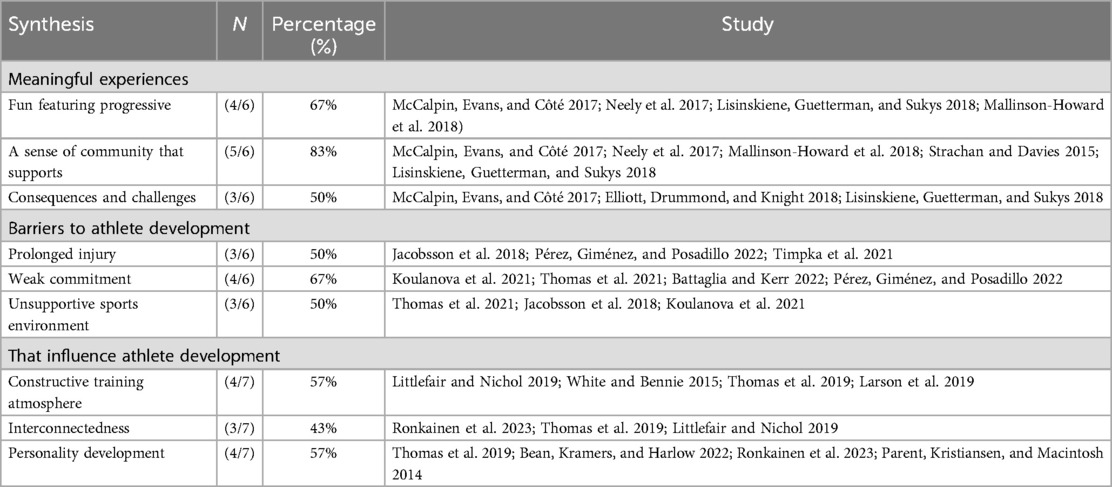

Table 6 summarizes the synthesis of the research theme findings. The theme of meaningful experiences, in terms of enjoyment, shows progression (48–51) 67% (4/6) studies show that participation in competitive sports is considered enjoyable, exciting, pride-inducing, skill-enhancing, and continuously improving. Regarding the sense of community that supports each other (48–52) 83% (5/6) studies discuss that adolescent athletes experience a sense of togetherness (parents, coaches, friends), which in turn forms a community that creates mutually supportive relationships for the athletes’ progress. In terms of consequences (48, 50, 53) 50% (3/6) studies report that loss of friends, frequency of play, and high social expectations become the consequences and challenges that adolescent athletes bear to continue developing. On the theme of barriers for adolescent athletes: in terms of prolonged injuries (2, 54, 55) 50% (3/6) studies report injuries as a highly negative experience that significantly affects their participation in competitive sports. Regarding weak commitment (38, 55–57) 67% (4/6) studies report pressure from various sources affecting the commitment of adolescent athletes to participate in competitive sports. In terms of an unsupportive sports environment (38, 54, 56) 50% (3/6) studies report various inadequate support such as funding, transparency, and psychological support for adolescent athletes. On the theme of the influence of athlete development: in terms of a constructive training atmosphere (39, 40, 58, 59) 57% (4/7) studies describe how athletes feel that a well-established training atmosphere makes them feel enjoyable, relaxed, and easy to socialize, enjoying the social aspect as members of the sports community. In terms of Connectedness 43% (3, 39, 58) (3/7), studies report that the connections formed (family, friends, coaches) create stability for adolescent athletes, which in turn positively influences their development. In terms of personality development (3, 39, 60, 61) 57% (4/7), studies report that positive experiences in competitive sports have a transformative impact on the personal development of adolescent athletes, such as discipline, confidence, leadership, and socio-cultural skills valuable for their future.

Table 6. The synthesis results of the research theme on the experiences of adolescent athletes in competitive sports.

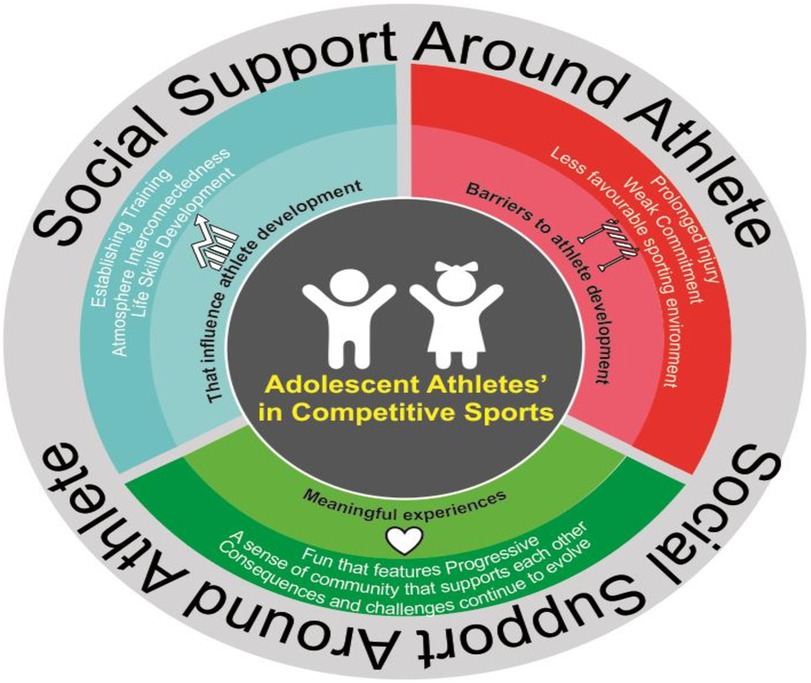

Based on the findings from the synthesis of each theme of the included research results, the concept of the social environment influencing the significant experiences of adolescent athletes in competitive sports has been developed and presented visually in (Figure 3). This concept explains that in competitive sports activities, adolescent athletes gain meaningful experiences, experiences that become obstacles, and experiences that influence their development. The capture of meaningful experiences refers to adolescent athletes who attribute deep significance to every moment of their journey in organized sports. Experiences that become obstacles lead to the challenges or hurdles athletes face when participating in competitive sports. Developmental experiences occur through a reciprocal process of competitive sports activities for adolescent athletes, influenced by various factors that affect the progressive changes in adolescent athletes. This conceptual model then views the significant experiences of these adolescent athletes as a process of their activities in competitive sports, with the surrounding social support interactions being highly influential. Adolescent athletes consistently mention coaches, parents/family, friends, and organizations influencing their journey in competitive sports, ultimately creating significant experiences for them. Coaches, for example, are almost involved in all significant experiences for adolescent athletes; meaningful experiences can be created through enjoyable training patterns (50), the sense of togetherness among coaches like family (52), and the coaches’ art of continuously challenging athletes (48). Even though it can have negative meanings that become obstacles, such as the wrong training patterns (54), the coach's anticipation affecting commitment (56), and the lack of attention from the coach (57). The coach is someone who influences the development of athletes by creating a training atmosphere (39), the positive behavior of the coach (40), and providing a strong personality (60).

Figure 3. The pattern of research findings on the essence of adolescent athletes' participation with social support.

This systematic review investigates the scientific evidence regarding the significant experiences of adolescent athletes’ participation in competitive sports life. This is the first systematic review highlighting key aspects of adolescent life in the complex realm of competitive sports, based on evidence from 19 studies representing the lives of adolescent athletes with a qualitative approach. Based on the analysis and synthesis of the literature included in this review, the experiences of adolescent athletes participating in competitive sports life are depicted (Figure 4). The following section will discuss some of the most interesting findings from this review.

Figure 4. Flowchart illustrating important experiences of adolescent athletes in competitive sports.

Adolescent athletes in competitive sports must create much excitement in the early stages of participation. Pleasure is an important predictor of athletes’ intrinsic motivation in the conclusion of his research (62). There is a sense of fulfillment within them because the competitive element of sports is closely tied to competition, pride, showcasing developing skills, and winning medals, but enjoying it in an atmosphere of excitement and fun will make it more meaningful in their research findings (48, 49). The role of the coach is very dominant here; coaches are perceived as life coaches for adolescents by adopting a more supportive approach, paying attention to the players’ needs, providing instructional feedback in a non-threatening manner, and praising the athletes; they seem to be able to reinforce the desire of adolescent athletes to develop (49). Coaches’ transformational leadership behavior and coach-athlete relationship quality are the best predictors of athlete development experiences (63).

In excitement, adolescent athletes also give meaning to new friends in the sports community by forming strong friendships that become a part of an adolescent's sports journey. Friends can provide feedback and motivate each other for improvement, and their skills create a drive to work harder and collaborate for team victories and success (49). Friendship and adult support in sports environments are woven over long periods, providing a sense of care that transcends organized relationships into enjoyable experiences for athletes’ well-being (48, 49). In its findings, sports become an opportunity to feel a sense of belonging and togetherness and blend into the crowd (51). Reflecting on the uniqueness of the sports experiences of adolescent athletes, the importance and strength of the friendships they create and maintain (48). Close friendships and the support and encouragement received from friends present in their sports experiences (52).

Thus, attention to field practice is significant to ensure that young athletes can develop through meaningful experiences participating in competitive sports. Practitioners and the adult environment of adolescent athletes must understand that the primary foundation for athletes starting in the world of sports is the enjoyment of adolescent athletes and meaningful friendships in competitive sports. Although they must be aware of the consequences of their participation, it becomes increasingly difficult to spend quality time with friends due to training commitments, and the nature of these relationships developing into potential sources of stress for adolescent athletes is a finding of the study (50, 53). Moreover, athletes learn from almost selective experiences of failure in competitive sports life, which significantly contributes to their growth; instead of giving up, they train harder to prove to their coaches that they are worthy (49). They see this pressure as an ‘opportunity’ for future challenges while understanding themselves as adolescent athletes. Of course, preventing and anticipating the negative consequences and meanings that can arise in the competitive sports lives of adolescent athletes and providing meaningful experiences in their activities to become elite athletes in the future will undoubtedly become a necessity.

Prolong injuries in adolescent athletes are a negative experience for their long-term participation in competitive sports. Adolescent athletes experience an increase in training volume and intensity alongside the rising demands of training and competition, but this is also when they suffer the most injuries, leading to frustration and withdrawal from competitive sports (2, 55). Many athletes experience injury pain that develops gradually during training, such as from hamstring strains and ankle sprains (2, 54). In the findings (2), adolescent athletes recruited from the World Athletics Championships narrated that continuous training activities caused their injuries despite feeling pain to meet the competition and national team requirements (2). Adolescent athletes, consisting of national teams from six countries representing three continents (Africa, Europe, and Asia), also recounted that their parents wanted them to continue training despite injuries to avoid jeopardizing their future athletic careers. The athletes’ experiences also consistently mention broken or inadequate equipment, lack of warm-up, and improper technique during matches, which in turn lead to injuries. Supporting similar findings in many cases, poor facilities became the leading cause of their injuries and failure to reach high levels of competition (54, 55). Then, Poor handling, as concluded from a study that asked adolescent athletes to summarize their experiences with medical support, often leads young athletes to repeatedly state that they must manage their health issues (2, 64). The main points of the findings indicate that the risk of injury and the severity of injuries are significant concerns among elite adolescent athletes.

The understanding and caution of stakeholders, such as the social environment, play an important role in managing athlete injuries and athlete commitment in competitive sports. Social support from organizations that are transparent in fund allocation can help the commitment of young athletes (54, 64). However, the lack of professionalism within organizations (e.g., sports federations, sports managers/administrators) can hinder young athletes in developing and maintaining sports operations. The negative experiences of young athletes reporting insufficient funding from organizations to continue their sports, potentially burdening their parents or themselves, are the main reasons why most of them choose to leave sports early (38, 55).

The negative experiences of the elitist nature of high-performance sports impact their academic performance and disrupt their other life commitments, leading to conflicts of interest and attempts at other activities (38, 57). In some cases, negative experiences such as concerns about negative body image are common among the adolescent female athletes, ranging from mild dissatisfaction (e.g., body dissatisfaction) to more serious issues (e.g., eating disorders), and that the sports environment can either support or hinder the development of a positive body image (56). Not to mention the excessive pressure often exerted by parents to excel in their sports and win competitions, which sometimes leads to frustration instead of supporting the athletic performance of young athletes (38, 54). In line with previous literature, this study provides additional support showing that the social psychological climate affects the perception of commitment (65). High levels of social support and external regulation in the long term can influence their goals, enhance satisfaction, and help their commitment to sports activities (62). By explicitly highlighting the important role of social support in sports development practices, athlete well-being (e.g., physical, mental, social) is not independent but interconnected and must be deliberately pursued by social support stakeholders (66). The lack of relationships with adults and an unsupportive organizational environment for adolescent athletes create negative experiences that hinder them from continuing to commit to and participate in competitive sports in the long term.

Changes in athlete development are often related to positive experiences in the sports activity environment. Coaches are responsible for creating a constructive training atmosphere where the coach-athlete relationship influences positive experiences that encompass trust, mutual understanding through discussion, and goal-oriented communication as key elements of positive experiences during childhood and adolescence (39, 40, 59). Coaches emphasize their desire to create an environment that facilitates player development through their experience and enthusiasm for the club and the sport (58). Such as validating findings that show the enjoyment of sports among adolescent athletes begins to fade due to excessive training with longer training distances and doing the same “work,” negative experiences with coaches or teammates (59). It is an art for a coach to continuously enhance an athlete's competence without diminishing their enjoyment and happiness in the atmosphere of competitive sports training.

When everything goes well, without interruptions, many young athletes focus their energy on athletic development and, to varying degrees, on their studies. In achieving those connections (parents, peers, coaches), they create stability for adolescent athletes in competitive sports (3). The family emerges as an introduction to sports for adolescent athletes and continues to motivate them to remain engaged in sports throughout childhood and adolescence (39, 58). The role of the family in several studies also ensures emotional support and self-esteem, attending training sessions, providing transportation to and from training, as well as tangible support and information through financial provision of equipment, supplies, and work-life balance (38, 39, 67–70). Equally important are relationships with friends who have similar experiences, which can foster a sense of belonging, need, understanding, and drive to continue improving (40, 58). In turn, connections with family, coaches, and friends significantly influence the maintenance of motivation and the consistent enjoyment of competitive sports, creating positive experiences in the development of young athletes.

Positive experiences in competitive sports have a transformative impact on the personal development of athletes. Scheduled activities such as eating, sleeping, and training take up a lot of time, so athletes rarely have the freedom to choose their activities, which becomes a valuable positive experience for future adolescent athletes (60). Adolescent athletes also explain how their self-confidence increases through participation in their respective sports teams, which influences the development of other skills, such as leadership, self-confidence, dedication, commitment, enjoyment, pride, and perseverance (3, 39, 60). Experience at the Youth Olympic Games (YOG) young athletes recounting the positive aspects of their participation such as: village environment, sports facilities, travel, ceremonies, medical services, and international experiences, sociocultural (especially informal) international, socio-cultural (especially informal) from the participation of young athletes in competitive sports (61). The participation of young athletes in competitive sports creates many positive experiences and, in turn, provides good personal development for young athletes for their future.

Understanding the significant experiences of adolescent athletes from the concept (Figure 3) may be beneficial in helping more adolescents engage in competitive sports while enhancing their positive developmental experiences. Confirming the theory that the characteristics of competitive sports training activities for adolescents reveal that consistent social support from coaches, parents, peers, and sports organization officials significantly contributes to relationships at the psychosocial development level during adolescence (50, 71, 72). At the same time, it supports the research model by Taryn K. Morgan, which describes how social support affects young people (73). For example, specific support system behaviors from coaches, parents, and peers influence the motivational atmosphere of adolescent athletes (74), creating a motivational climate that sustains athletes’ perseverance in sports (75, 76). In turn, it provides positive experiences by demonstrating trust and attachment to the sport and love for the sport they choose (77). Adolescent athletes speak very enthusiastically about how sports support autonomy and how meaningful and enjoyable they are for them (30, 78). The relationship with this social support fosters mutual understanding, trust, and friendship, culminating in the formation of harmonious connections that provide positive experiences in the sustainability of their competitive sports.

These findings align with the socio-ecological model (56, 79), where social support can address negative body image in adolescent girls’ sports. With a focus on negative experiences, improvements in all areas of the sports system may be valuable to help keep more adolescent female athletes engaged in sports while enhancing their positive sports experiences where misunderstandings in coaching adolescent athletes can transform the role of social support from coaches, parents, organizations, and peers into negative experiences in the competitive sports life of adolescents. As the theoretical findings from the Grounded Theory study of the influences affecting the sports experiences and withdrawal patterns of young athletes show, adolescents’ sports experiences and withdrawal patterns are influenced by their interpretations of personal, social, and organizational influences (80). Qualitative studies reveal that college, professional, and semi-professional athletes describe the theme of mental skill inhibition as consisting of athletes’ descriptions of poor coaches as distractions, causing self-doubt, demotivation, and team division (81). Similar to qualitative studies revealing that coaches are overly critical, negatively impacting their confidence during the transition period in elite sports (82). Athletes report that one of the main reasons they quit competitive sports is because they ‘do not like the pressure’ and ‘do not like their coach’ (83–85). Consistent studies on the withdrawal of adolescent athletes indicate that their negative experiences are influenced by their social environment, such as negative parental behaviors, which include placing too much emphasis on winning, having unrealistic expectations, and criticizing their children (76), deep sadness due to injuries, which can be caused by inadequate training programs (86, 87), poor coping techniques, and inadequate facilities (55, 88–90), conflicts with friends during training (84, 91).

Therefore, this becomes a concern in field practice to ensure that young athletes have positive experiences participating in competitive sports, which is undoubtedly greatly influenced by their social environment that works with their hearts for the development of young athletes—not just performing their duties and obligations without touching their hearts, for example, only focusing on teaching techniques, strategies, or physical aspects without considering the athletes’ emotions (63, 92–95). This is similar to parents who only accompany their child to the gym without asking, “How was your workout today?”. Give them space to grow and develop in competitive sports by experiencing positive experiences and reducing negative ones. If this process goes well, their transition to elite athletes will indeed be achieved and will benefit the personal development of young athletes.

A general consideration of this systematic review is the lack of literature comprehensively discussing adolescents experiencing organized competitive sports. The initial goal of this study is to synthesize various research projects that reveal important insights about adolescent athletes in their journey through organized competitive sports. The results of this synthesis are expected to enhance understanding and provide valuable insights into the significant experiences of adolescent athletes participating in competitive sports. This review is based on electronic databases, which apply secondary search strategies. This may have resulted in the identification and exclusion of several studies from the review. Finally, a total of 19 articles that met the inclusion criteria qualified, which is a modest evidence base, to examine the experiences of adolescent athletes. However, it is important to note several significant limitations. First of all, it is important to consider the heterogeneity of the participants, which can be seen from their ages. Secondly, competitive sports pursued by athletes have different characteristics, depending on whether individual- or team-oriented. Moreover, a deep understanding of the culture in which athletes are raised can make a significant difference, facilitating positive adaptation and development. The findings of this study will provide a broader understanding of adolescent athletes in competitive sports while also highlighting the importance of their socio-cultural development.

The findings suggest that working with young athletes requires attention to both visible and invisible factors. It is not just about tracking time, training loads, and medal targets. Young athletes need to be in the right environment, and the environment must be right for them to support positive development. Ensuring that sport provides meaning in their lives, fostering happiness, togetherness, and growth, is essential. They must connect with social elements such as family, coaches, and peers to support their journey towards becoming elite athletes. Future research should: (i) incorporate a wider range of methods to explore adolescent athletes in professional sports; (ii) investigate the long-term outcomes of both successful and unsuccessful adolescent athletes in professional sports; (iii) delve into the stories of adolescents being prepared to become elite athletes; and (iv) consider gender perspectives in competitive sport.

Three important characteristics of the experiences of adolescent athletes in competitive sports activities in their development through the available literature. First, it highlights how young athletes perceive their sport, experiencing deep happiness, friendships, and their challenges. Second, it emphasizes the negative experiences that become obstacles faced by young athletes in their development, such as injuries, weak commitment, and lack of social support, which adults often overlook. Third, it emphasizes the important positive experiences in life skills that athletes must develop through harmonious relationships with social elements that support their growth. From the significant experiences of adolescent athletes participating in competitive sports, the social environment contributes to each of those experiences. The practical implications of these findings indicate that working with young athletes is not only about training loads and medal goals but also about ensuring that they are in a supportive environment that fosters their development. To help adolescent athletes become elite, we must connect all the social elements within their sports environment. Future research should focus on developing a framework that highlights the social roles of young athletes and explores their personal experiences in a highly competitive sports environment, ultimately offering a comprehensive understanding of athlete development.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

MD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Software, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft. HR: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. CS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported in part by the Higher Education Financing Agency (BPPT) under the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research and Technology of the Republic of Indonesia, and the LPDP.

The authors would like to thank Universitas Musamus Merauke. The authors also thank BPPT under the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research and Technology of the Republic of Indonesia, and the LPDP.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Merkel DL. Youth sport: positive and negative impact on young athletes. Open Access J Sports Med. (2013) 4:151–60. doi: 10.2147/OAJSM.S33556

2. Timpka T, Fagher K, Bargoria V, Gauffin H, Andersson C, Jacobsson J, et al. ‘The little engine that could’: a qualitative study of medical service access and effectiveness among adolescent athletics athletes competing at the highest international level. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18(14):7278. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18147278

3. Ronkainen N, Aggerholm K, Allen-Collinson J, Ryba TV. Beyond life-skills: talented athletes, existential learning and (un)learning the life of an athlete. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. (2023) 15(1):35–49. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2022.2037694

4. Brower JJ. The professionalization of organized youth sport: social psychological impacts and outcomes. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. (1979) 445(1):39–46. doi: 10.1177/000271627944500106

5. Camiré M, Santos F. Promoting positive youth development and life skills in youth sport: challenges and opportunities amidst increased professionalization. J Sport Pedagogy Res. (2019) 5(1):27–34.

6. Sweeney L, Horan D, MacNamara Á. Premature professionalisation or early engagement? Examining practise in football player pathways. Front Sports Act Living. (2021) 3:660167. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2021.660167

7. A. B. of Statistics. Children’s Participation in Cultural and Leisure Activities Australia. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics (2000).

8. Ryska T, Hohensee D, Cooley P, Jones C. Participation motives in predicting sport dropout among Australian youth gymnasts. N Am J Psychol. (2002) 4(2):199–210.

9. De Knop P, Engstroem L-M, Skirstad B, Weiss MR. Worldwide Trends in Youth Sport. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics (1996).

10. Eime RM, Harvey JT, Sawyer NA, Craike MJ, Symons CM, Polman RCJ, et al. Understanding the contexts of adolescent female participation in sport and physical activity. Res Q Exerc Sport. (2013) 84(2):157–66. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2013.784846

11. Eime RM, Young JA, Harvey JT, Charity MJ, Payne WR. A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for children and adolescents: informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2013) 10(1):1–21. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-10-98

12. Fraser-Thomas JL, Côté J, Deakin J. Youth sport programs: an avenue to foster positive youth development. Phys Educ Sport Pedagogy. (2005) 10(1):19–40. doi: 10.1080/1740898042000334890

13. Panza MJ, Graupensperger S, Agans JP, Doré I, Vella SA, Evans MB. Adolescent sport participation and symptoms of anxiety and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sport Exerc Psychol. (2020) 42(3):201–18. doi: 10.1123/jsep.2019-0235

14. Patton GC, Viner R. Pubertal transitions in health. Lancet. (2007) 369(9567):1130–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60366-3

15. Lawrence D, Johnson S, Hafekost J, Boterhoven de Haan K, Sawyer M, Ainley J, et al. The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents. Canberra: Department of Health (2015).

16. Walton CC, Rice S, Hutter RIV, Currie A, Reardon CL, Purcell R. Mental health in youth athletes: a clinical review. Adv Psychiatry Behav Health. (2021) 1(1):119–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ypsc.2021.05.011

17. Schubring A, Thiel A. Growth problems in youth elite sports. Social conditions, athletes’ experiences and sustainability consequences. In: Barker-Ruchti N, Barker D, editors. Sustainability in High Performance Sport. London: Routledge (2017). p. 88–101. doi: 10.4324/9781315657394

18. Brettschneider W-D. Risks and opportunities: adolescents in top-level sport ñ growing up with the pressures of school and training. Eur Phy Educ Rev. (1999) 5(2):121–33. doi: 10.1177/1356336X990052004

19. Hayward FPI, Knight CJ, Mellalieu SD. A longitudinal examination of stressors, appraisals, and coping in youth swimming. Psychol Sport Exerc. (2017) 29:56–68. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2016.12.002

20. Raedeke TD, Smith AL. Coping resources and athlete burnout: an examination of stress mediated and moderation hypotheses. J Sport Exerc Psychol. (2004) 26(4):525–41. doi: 10.1123/jsep.26.4.525

21. Fry RW, Morton AR, Keast D. Overtraining in athletes: an update. Sports Med. (1991) 12:32–65. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199112010-00004

22. Grove JR, Main LC, Partridge K, Bishop DJ, Russell S, Shepherdson A, et al. Training distress and performance readiness: laboratory and field validation of a brief self-report measure. Scand J Med Sci Sports. (2014) 24(6):e483–490. doi: 10.1111/sms.12214

23. Gilbert JN, Gilbert W, Morawski C. Coaching strategies for helping adolescent athletes cope with stress. J Phys Educ Recreat Dance. (2007) 78(2):13–24. doi: 10.1080/07303084.2007.10597967

24. Mountjoy M. International Olympic committee consensus statement: harassment and abuse (non-accidental violence) in sport. Br J Sports Med. (2016) 50(17):1019–29. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096121

25. Galli N, Vealey RS. ‘Bouncing back’ from adversity: athletes’ experiences of resilience. Sport Psychol. (2008) 22(3):316–35. doi: 10.1123/tsp.22.3.316

26. Rutter M. Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms’. In: Rolf J, Masten AS, Cicchetti D, Nuechterlein KH, Weintraub S, editors. Risk and Protective Factors in the Development of Psychopathology. Cambridge: Cambridge Unversity Press (1990). p. 181–214.

27. Bennie A, O’Connor D. Athletic transition: an investigation of elite track and field participation in the post-high school years. Change Transform Ed. (2006) 9(1):59–68.

28. Tamminen KA, Holt NL. A meta-study of qualitative research examining stressor appraisals and coping among adolescents in sport. J Sports Sci. (2010) 28(14):1563–80. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2010.512642

29. Baker J, Cote J, Abernethy B. Sport-specific practice and the development of expert decision-making in team ball sports. J Appl Sport Psychol. (2003) 15(1):12–25. doi: 10.1080/10413200305400

30. Côté J, Fraser-Thomas J. Youth involvement in sport. In: Crocker PRE, editor. Sport Psychology: A Canadian Perspective. Toronto: Pearson Prentice Hall (2007). p. 266–94.

31. Besharat MA, Pourbohlool S. Moderating effects of self-confidence and sport self-efficacyon the relationship between competitive anxietyand sport performance. Psychology. (2011) 2(07):760. doi: 10.4236/psych.2011.27116

32. Hays K, Maynard I, Thomas O, Bawden M. Sources and types of confidence identified by world class sport performers. J Appl Sport Psychol. (2007) 19(4):434–56. doi: 10.1080/10413200701599173

33. Compton MT, Koplan C, Oleskey C, Powers RA, Pruitt D, Wissow L. Prevention in Mental Health: an Introduction from the Prevention Committee of the Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing (2010). p. 1–2. doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9781615378029.lg01

34. Lindner KJ, Johns DP, Butcher J. Factors in withdrawal from youth sport: a proposed model. J Sport Behav. (1991) 14(1):3. doi: 10.1123/pes.1.3.195

35. Weiss MR, Petlichkoff LM. Children’s motivation for participation in and withdrawal from sport: identifying the missing links. Pediatr Exerc Sci. (1989) 1(3):195–211. doi: 10.1123/pes.1.3.195

36. Williams MD, Braun LA, Cooper LM, Johnston J, Weiss RV, Qualy RL, et al. Hospitalized cancer patients with severe sepsis: analysis of incidence, mortality, and associated costs of care. Crit Care. (2004) 8(5):1–8. doi: 10.1186/cc2893

37. Strachan L, Côté J, Deakin J. A new view: exploring positive youth development in elite sport contexts. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. (2011) 3(1):9–32. doi: 10.1080/19398441.2010.541483

38. Thomas CE, Chambers TP, Main LC, Gastin PB. Motives for dropout among former junior elite Caribbean track and field athletes: a qualitative investigation. Front Sports Act Living. (2021) 3:1–13. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2021.696205

39. Thomas CE, Chambers TP, Main LC, Gastin PB. Influencing the early development of world-class caribbean track and field athletes: a qualitative investigation Bursa, Turkiye. J Sports Sci Med. (2019) 18(4):758–71.31827361

40. White RL, Bennie A. Resilience in youth sport: a qualitative investigation of gymnastics coach and athlete perceptions. Int J Sports Sci Coach. (2015) 10(2–3):379–93. doi: 10.1260/1747-9541.10.2-3.379

41. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, t PRISMA Group*. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. (2009) 151(4):264–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

42. Gusenbauer M. Google scholar to overshadow them all? Comparing the sizes of 12 academic search engines and bibliographic databases. Scientometrics. (2019) 118(1):177–214. doi: 10.1007/s11192-018-2958-5

43. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br Med J. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

44. Shaffril HAM, Samah AA, Samsuddin SF, Ali Z. Mirror-mirror on the wall, what climate change adaptation strategies are practiced by the Asian’s fishermen of all? J Clean Prod. (2019) 232:104–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.05.262

45. Donthu N, Kumar S, Mukherjee D, Pandey N, Lim WM. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: an overview and guidelines. J Bus Res. (2021) 133:285–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.070

46. Faber IR, Bustin PMJ, Oosterveld FGJ, Elferink-Gemser MT, Nijhuis-Van der Sanden MWG. Assessing personal talent determinants in young racquet sport players: a systematic review. J Sports Sci. (2016) 34(5):395–410. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2015.1061201

47. Letts L, Wilkins S, Law M, Stewart D, Bosch J, Westmorland M. Guidelines for Critical Review Form: Qualitative Studies (Version 2.0). Hamilton: McMaster University Occupational Therapy Evidence-based Practice Research Group (2007). p. 1–12.

48. McCalpin M, Evans B, Côté J. Young female soccer players’ perceptions of their modified sport environment. Sport Psychologist. (2017) 31(1):65–77. doi: 10.1123/tsp.2015-0073

49. Neely KC, McHugh TLF, Dunn JGH, Holt NL. Athletes and parents coping with deselection in competitive youth sport: a communal coping perspective. Psychol Sport Exerc. (2017) 30:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.01.004

50. Lisinskiene A, Guetterman T, Sukys S. Understanding adolescent–parent interpersonal relationships in youth sports: a mixed-methods study. Sports. (2018) 6(2):41. doi: 10.3390/sports6020041

51. Mallinson-Howard SH, Knight CJ, Hill AP, Hall HK. The 2×2 model of perfectionism and youth sport participation: a mixed-methods approach. Psychol Sport Exerc. (2018) 36:162–73. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.02.011

52. Strachan L, Davies K. Click! using photo elicitation to explore youth experiences and positive youth development in sport. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. (2015) 7(2):170–91. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2013.867410

53. Elliott S, Drummond MJN, Knight C. The experiences of being a talented youth athlete: lessons for parents. J Appl Sport Psychol. (2018) 30(4):437–55. doi: 10.1080/10413200.2017.1382019

54. Jacobsson J, Bergin D, Timpka T, Nyce JM, Dahlström Ö. Injuries in youth track and field are perceived to have multiple-level causes that call for ecological (holistic-developmental) interventions: a national sporting community perceptions and experiences. Scand J Med Sci Sports. (2018) 28(1):348–55. doi: 10.1111/sms.12929

55. Pérez BD, Giménez AR, Posadillo AÁS. Women and competitive sport: perceived barriers to equality. Cultura Ciencia Deporte. (2022) 17(54):63–86. doi: 10.12800/ccd.v17i54.1887

56. Koulanova A, Sabiston CM, Pila E, Brunet J, Sylvester B, Sandmeyer-Graves A, et al. Ideas for action: exploring strategies to address body image concerns for adolescent girls involved in sport. Psychol Sport Exerc. (2021) 56:102017. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.102017

57. Battaglia A, Kerr G. Exploring sport stakeholders’ interpretations of the term dropout from youth sport. J Appl Sport Psychol. (2022) 34(1):67–88. doi: 10.1080/10413200.2019.1707727

58. Littlefair D, Nichol D. Youth sport: a frontier in education. Front Educ (Lausanne). (2019) 4:1–6. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00119

59. Larson HK, McHugh TLF, Young BW, Rodgers WM. Pathways from youth to masters swimming: exploring long-term influences of youth swimming experiences. Psychol Sport Exerc. (2019) 41:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.11.007

60. Bean C, Kramers S, Harlow M. Exploring life skills transfer processes in youth hockey and volleyball. Int J Sport Exerc Psychol. (2022) 20(1):263–82. doi: 10.1080/1612197X.2020.1819369

61. Parent MM, Kristiansen E, Macintosh EW. Athletes’ experiences at the youth Olympic games: perceptions, stressors, and discourse paradox. Event Management. (2014) 18(3):303–24. doi: 10.3727/152599514X13989500765808

62. Berki T, Piko BF, Page RM. The relationship between the models of sport commitment and self-determination among adolescent athletes. Acta Fac Ed Phys Univ Comen. (2019) 59(2):79–95. doi: 10.2478/afepuc-2019-0007

63. Vella SA, Oades LG, Crowe TP. The relationship between coach leadership, the coach–athlete relationship, team success, and the positive developmental experiences of adolescent soccer players. Phys Educ Sport Pedagogy. (2013) 18(5):549–61. doi: 10.1080/17408989.2012.726976

64. Fraser-Thomas J, Côté J, Deakin J. Understanding dropout and prolonged engagement in adolescent competitive sport. Psychol Sport Exerc. (2008) 9(5):645–62. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2007.08.003

65. Hall MS, Newland A, Newton M, Podlog L, Baucom BR. Perceptions of the social psychological climate and sport commitment in adolescent athletes: a multilevel analysis. J Appl Sport Psychol. (Jan. 2017) 29(1):75–87. doi: 10.1080/10413200.2016.1174906

66. Berg BK, Warner S. Advancing college athlete development via social support. J Issues Intercoll Athl. (2019) 12(1):87–113.

67. Trussell DE, Shaw SM. Organized youth sport and parenting in public and private spaces. Leis Sci. (2012) 34(5):377–94. doi: 10.1080/01490400.2012.714699

68. Scanlan TK, Lewthwaite R. Social psychological aspects of competition for male youth sport participants: i. Predictors of competitive stress. J Sport Exerc Psychol. (1984) 6(2):208–26. doi: 10.1123/jsp.6.2.208

69. Dorsch TE, Smith AL, McDonough MH. Early socialization of parents through organized youth sport. Sport Exerc Perform Psychol. (2015) 4(1):3. doi: 10.1037/spy0000021

70. Howie EK, Daniels BT, Guagliano JM. Promoting physical activity through youth sports programs: it’s social. Am J Lifestyle Med. (2020) 14(1):78–88. doi: 10.1177/1559827618754842

71. Sheridan D, Coffee P, Lavallee D. A systematic review of social support in youth sport. Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol. (2014) 7(1):198–228. doi: 10.1080/1750984X.2014.931999

72. Wylleman P, Lavallee D. A developmental perspective on transitions faced by athletes. Developmental Sport and Exercise Psychology: A Lifespan Perspective. Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology (2004). p. 507–27.

73. Morgan TK, Giacobbi PR. Toward two grounded theories of the talent development and social support process of highly successful collegiate athletes. Sport Psychol. (2006) 20(3):295–313. doi: 10.1123/tsp.20.3.295

74. Keegan R, Spray C, Harwood C, Lavallee D. The motivational atmosphere in youth sport: coach, parent, and peer influences on motivation in specializing sport participants. J Appl Sport Psychol. (2010) 22(1):87–105. doi: 10.1080/10413200903421267

75. Carr S. Adolescent–parent attachment characteristics and quality of youth sport friendship. Psychol Sport Exerc. (2009) 10(6):653–61. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2009.04.001

76. Le Bars H, Gernigon C, Ninot G. Personal and contextual determinants of elite young athletes’ persistence or dropping out over time. Scand J Med Sci Sports. (2009) 19(2):274–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2008.00786.x

77. Baxter-Jones ADG, Maffulli N. Parental influence on sport participation in elite young athletes. J Sports Med Phys Fitn. (2003) 43(2):2505.

78. Lafrenière M-AK, Jowett S, Vallerand RJ, Carbonneau N. Passion for coaching and the quality of the coach–athlete relationship: the mediating role of coaching behaviors. Psychol Sport Exerc. (2011) 12(2):144–52. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2010.08.002

79. Bronfenbrenner U, Morris PA. The ecology of developmental processes. In: Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of Child Psychology: Theoretical Models of Human Development. Vol. 1. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. (1998). p. 993–1028.

80. Battaglia A, Kerr G, Tamminen K. A grounded theory of the influences affecting youth sport experiences and withdrawal patterns. J Appl Sport Psychol. (2022) 34(4):780–802. doi: 10.1080/10413200.2021.1872732

81. Gearity BT, Murray MA. Athletes’ experiences of the psychological effects of poor coaching. Psychol Sport Exerc. (2011) 12(3):213–21. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2010.11.004

82. Bruner MW, Munroe-Chandler KJ, Spink KS. Entry into elite sport: a preliminary investigation into the transition experiences of rookie athletes. J Appl Sport Psychol. (2008) 20(2):236–52. doi: 10.1080/10413200701867745

83. Salguero A, Gonzalez-Boto R, Tuero C, Marquez S. Identification of dropout reasons in young competitive swimmers. J Sports Med Phys Fitn. (2003) 43(4):530–4.

84. Evans L, Hardy L. Sport injury and grief responses: a review. J Sport Exerc Psychol. (1995) 17(3):227–45. doi: 10.1123/jsep.17.3.227

85. Ruggiero TE, Lattin KS. Intercollegiate female coaches’ use of verbally aggressive communication toward African American female athletes. Howard J Commun. (2008) 19(2):105–24. doi: 10.1080/10646170801990946

86. Protivnak JJ, Tessmer SS, Lockard NL, Spisak T. Unrecognized grief: counseling interventions for injured student-athletes. J Counselor Practice. (2023) 14(1):75–101. doi: 10.22229/aws8975026

87. Van der Poel J, Nel P. Relevance of the kübler-ross model to the post-injury responses of competitive athletes. S Afr J Res Sport Phys Ed Recreation. (2011) 33(1):151–64. doi: 10.4314/sajrs.v33i1.65496

88. Diekfuss JA. Can we capitalize on central nervous system plasticity in young athletes to inoculate against injury? J Sci Sport Exerc. (2020) 2(4):305–18. doi: 10.1007/s42978-020-00080-3

89. Jowett S. Coaching effectiveness: the coach–athlete relationship at its heart. Curr Opin Psychol. (2017) 16:154–8. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.05.006

90. Von Rosen P, Heijne A, Frohm A, Fridén C, Kottorp A. High injury burden in elite adolescent athletes: a 52-week prospective study. J Athl Train. (2018) 53(3):262–70. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-251-16

91. Mutz M. Athletic participation and the approval and use of violence: a comparison of adolescent males in different sports disciplines. Eur J Sport Soc. (2012) 9(3):177–201. doi: 10.1080/16138171.2012.11687896

92. Jowett S, Chaundy V. An investigation into the impact of coach leadership and coach-athlete relationship on group cohesion. Group Dyn Theory Res Pract. (2004) 8(4):302. doi: 10.1037/1089-2699.8.4.302

93. Jowett S, Poczwardowski A. Understanding the coach-athlete relationship. In: Jowette S, Lavallee D, editors. Social Psychology in Sport. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics (2007). p. 3–14. doi: 10.5040/9781492595878.ch-001

94. Nash C, Collins D. Tacit knowledge in expert coaching: science or art? Quest. (2006) 58(4):465–77. doi: 10.1080/00336297.2006.10491894

Keywords: youth athlete, athlete development, competitive life, youth experience, sports complexity

Citation: Dongoran MF, Setyawati H, Kristiyanto A, Raharjo HP and Setiawan C (2025) Understanding significant experiences of adolescent athletes’ participation in competitive sports life: a systematic review. Front. Sports Act. Living 7:1515200. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2025.1515200

Received: 22 October 2024; Accepted: 6 March 2025;

Published: 24 March 2025.

Edited by:

Mabliny Thuany, University of Porto, PortugalReviewed by:

Artur Jorge Baptista Santos, Polytechnic Institute of Bragança (IPB), PortugalCopyright: © 2025 Dongoran, Setyawati, Kristiyanto, Raharjo and Setiawan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: M. Fadli Dongoran, ZG9uZ29yYW5fcGprckBzdHVkZW50cy51bm5lcy5hYy5pZA==; Heny Setyawati, aGVueXNldHlhd2F0aUBtYWlsLnVubmVzLmFjLmlk

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.