- 1Department of Sports Science, School of Pharmacy, Institut Teknologi Bandung, Bandung, Indonesia

- 2Department of Exercise Science, Institute of Sport Science and Motology, Philipps University of Marburg, Marburg, Germany

- 3Movement and Training Science, Faculty of Sport Science, Leipzig University, Leipzig, Germany

Introduction: This systematic review aimed to investigate differences in match-play data according to the five playing categories in badminton.

Materials and methods: The systematic review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Searches were conducted on ScienceDirect, PubMed, Google Scholar, Scopus, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library databases. Studies assessing technical-tactical actions, activity profiles, or external and internal loads as match-play outcome measures according to the five playing categories in badminton were deemed eligible. Quality assessment was performed using a modified version of the AMSTAR-2 checklist to compare the outcome measures, effect sizes (ES) and associated 95% confidence intervals were calculated.

Results: Of the 12,967 studies that were identified, 34 met the eligibility criteria. Among these, 29 and five were rated as excellent and good quality, respectively. Some individual ESs of activity profiles showed up to large differences (ES ≤ 4.52) favouring the men's compared with the women's singles category. Some individual ESs of activity profiles showed up to large differences (ES ≤ -2.72) favouring the women's doubles category compared with other doubles categories. The overall ESs for the activity profiles were large (ES = −0.76 to −0.90), favouring the doubles over the singles categories in both sexes.

Discussion: There are up to large differences in match-play data according to the five playing categories in badminton, each category placing specific demands on the players. Thus, each category requires specific training and testing procedures, what should be considered by scientists and coaches.

1 Introduction

Since 1992, badminton has been part of the Olympic Games and has developed into a racquet sport with a professional structure and high level of competition (1). It has been estimated that over 200 million people play this sport recreationally and more than 7,000 athletes compete in hundreds of international and national competitions each year (1). To compete, the intermittent characteristics of badminton require optimised physical, technical-tactical, and psychological factors (2–4). An important aspect of badminton is the five different playing categories: men's and women's singles and men's, women's, and mixed doubles (5). Without strong evidence, the different playing categories are assumed to place specific demands on the players (1). Thereon, specific training and testing procedures are required to prepare the players (6, 7). Generally, such procedures should mimic particular playing demands (8), thereby requiring knowledge of match-play data (9, 10).

Badminton match-play data can be categorised into four groups: (1) technical-tactical actions, (2) activity profiles, (3) external (mechanical), and (4) internal (physiological) loads (9, 11). The four groups are interrelated (12). For example, technical-tactical actions such as smash, drive, drop, lob, and clear shots affect the activity profiles regarding the match duration, rally time, and work density (13–15). Furthermore, the resulting activity profiles affect the external and internal loads that players must meet (1, 9, 10). Finally, internal loads can induce long-term adaptations that can influence all the aforementioned aspects (10). Thus, a comprehensive understanding of these variable groups and their interactions is valuable to consider for scientists and coaches in badminton, when aiming to design specific training and testing procedures for the playing categories and other important influencing attributes of the players such as sex, playing level, and age (1, 9, 16–18). As evidence, analyzing match-play data helps identify the specific demands placed on players, enabling them to enhance performance through physiological adaptations and reduce the risk of injuries (17). Unfortunately, evidence on match-play data in badminton is limited; especially, regarding the specific demands of the five playing categories (1). Thus, more evidence-based research is needed.

To our knowledge, there are three reviews on badminton match-play. One systematic review investigated the effects of badminton on health outcomes and discovered that this sport improves cardiopulmonary function and physical abilities such as endurance and strength (19). A further review on general playing characterises of badminton was narrative in its nature (1) and the other solely focused on internal loads across several racquet sports (20). While previous reviews have provided evidence of the health benefits (19), general characteristics (1), and internal loads of badminton (20), there is no systematic overview regarding match-play data in badminton yet. Consequently, how the existing literature on badminton match-play data differs especially based on the five playing categories is still unclear. This problem creates ambiguity and debates among scientists and coaches (1). Therefore, a systematic literature review of match-play data concerning the five playing categories in badminton is warranted.

Thus, this systematic review aimed to investigate differences in match-play data according to the five playing categories in badminton.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Research design and search strategy

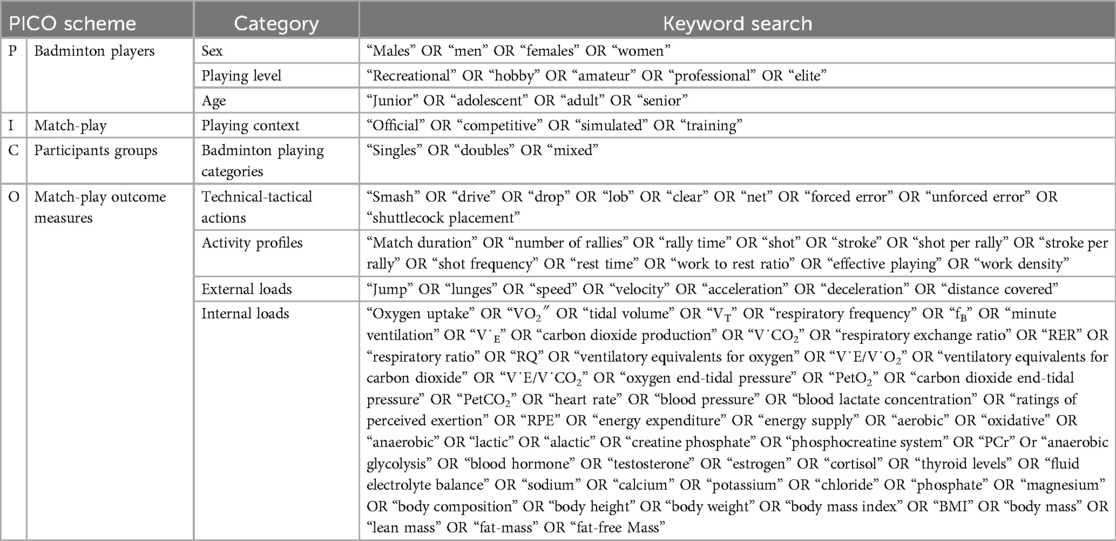

The systematic review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (21). The initial literature search was conducted in databases, including ScienceDirect, PubMed, Google Scholar, Scopus, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library on 1 June 2023. Additionally, to ensure that all actual available literature was included, an update was conducted immediately before submission on July 2024. The P = Population, I = Intervention, C = Comparisons, and O = Outcomes (PICO) scheme (21) was used to develop the search lines. Search terms were created by linking category sections with the Boolean operator “AND” to ensure that at least one term from each section appeared in searches, while the “OR” operator was used to link terms within a section (Table 1). The received entries were downloaded to a citation manager (Clarivate Analytics, Endnote X9, London, UK), and duplicates were removed. Furthermore, the “related citations” feature of PubMed was used to identify further relevant studies. A spreadsheet (Microsoft Office, Excel 2016, Redmond, WA, USA) was created to manage the detected studies following the developed PICO scheme. The titles, abstracts, and full texts of the selected studies were screened based on the defined eligibility criteria and studies considered unsuitable were excluded. Additionally, the reference lists of eligible studies were reviewed to identify relevant studies that were not detected by the search line. Any studies using the pre-2006 scoring system were excluded due to significant differences in playing time, which could affect the match-play outcome measures (22). All data were independently extracted by two authors (BW and TA). In terms of disagreements, a third author (MWH) was added and it was discussed until a consensus was reached. This proceed was also applied to the study quality assessment described below.

2.2 Eligibility criteria

This review included cross-sectional and longitudinal studies involving both sexes, playing level, all ages of badminton players investigated during match-play. The specific eligibility criteria included studies: (1) written in English; (2) with ethical approval (except for retrospective studies); (3) involving non-injured or non-paralympic players; (4) including the five badminton playing categories; (5) investigating official or simulated matches without experimental approaches; and (6) involving technical-tactical actions, activity profiles, or external and internal loads as match-play outcome measures.

2.3 Study quality assessment

A modified version of the AMSTAR-2 checklist (23) was used to assess the study quality based on 16 specific questions related to: (1) clarity of purpose; (2) relevance of background literature; (3) appropriate study design; (4) study sample; (5) sample size justification; (6) informed consent procedure (if any); (7) reliability and (8) validity of outcome measures; (9) detailed method description; (10) results reporting; (11) analysis methods; (12) description of practical importance; (13) description of drop-outs (if any); (14) appropriately drawn conclusions; (15) implications for practice; and (16) acknowledgement of study limitations. Previous study was modified critical review components into a single score, which proved effective for assessing the risk of bias in observational studies (10). Each question was scored using binary values (0 = no, 1 = yes), except for questions 6 and 13, for which “not applicable” was also an option. Finally, the results were converted into a percentage score by summing all individual scores and dividing by the maximum possible score; thus, a higher percentage indicated a higher study quality (10). As previously conducted, the scores were divided into three methodological quality categories: low (≤50%), good (51% to 75%), and excellent (>75%) (10, 24).

2.4 Data extraction

The data were extracted using the PICO scheme. The following data were collected: P = sample size, sex, playing level, and age; I = playing context (official or simulated match-play); C = single, double, or mixed playing categories; and O = main outcome measure regarding technical-tactical actions, activity profiles, and external and internal loads. If published data were unclear or missing, the corresponding authors were contacted via e-mail.

2.5 Data synthesis

The outcome measures were categorised into the five playing categories in badminton. Additionally, sex (men and women) and playing level were considered, whereby the latter was clustered into world-class, elite/international level, highly trained/national level, trained/developmental, and recreationally active players, as previously recommended (25).

2.6 Statistical analysis

Since a meta-analysis could not be conducted due to the large heterogeneity of the included studies and their data, effect sizes (ES) and associated 95% confidence intervals (CI) were alternatively calculated to compare differences in means (26), as conducted in previous systematic reviews with similar applied sport science purposes before (27, 28). The main advantage of that alternative statistical approach is that ESs can easily be computed from the means and standard deviations of the included original studies, which enhances the transparency and reliability of the outcome statistics of reviews. With respect to the computation, both individual and overall ESs were computed. Therefore, the mean differences were divided by the average standard deviations (29), with pooled baseline standard deviations (30). Based on established criteria (30), ESs were interpreted as small (<0.40), moderate (0.40–0.70), and large (>0.70). For validity, ESs were calculated only for means based on, at least in part, two studies or comparisons. Microsoft Excel 2016 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) was used for all the calculations.

3 Results

3.1 Literature search

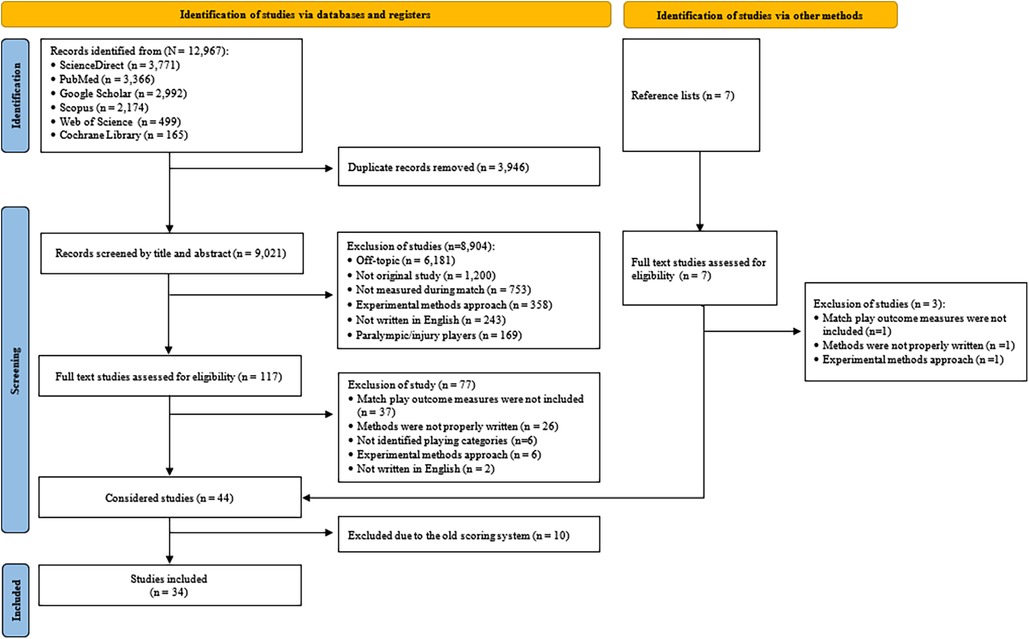

Figure 1 illustrates the results of the literature search. Initially, 12,967 studies were identified, with 3,946 removed because of duplication, leaving 9,021 studies. These studies were screened by title and abstract against the defined eligibility criteria, resulting in the exclusion of 8,904 studies. The remaining 117 studies underwent full-text screening, with 77 excluded based on the exclusion criteria. From the 40 studies considered, seven additional studies were obtained from the reference lists. Of these, three were excluded for not meeting the eligibility criteria, resulting in 44 studies. However, 10 of these 44 studies were removed because they used an outdated badminton scoring system that existed until 2006 (13–15, 22, 31–36). Finally, the remaining 34 studies were considered for the quality assessment (2–5, 37–66).

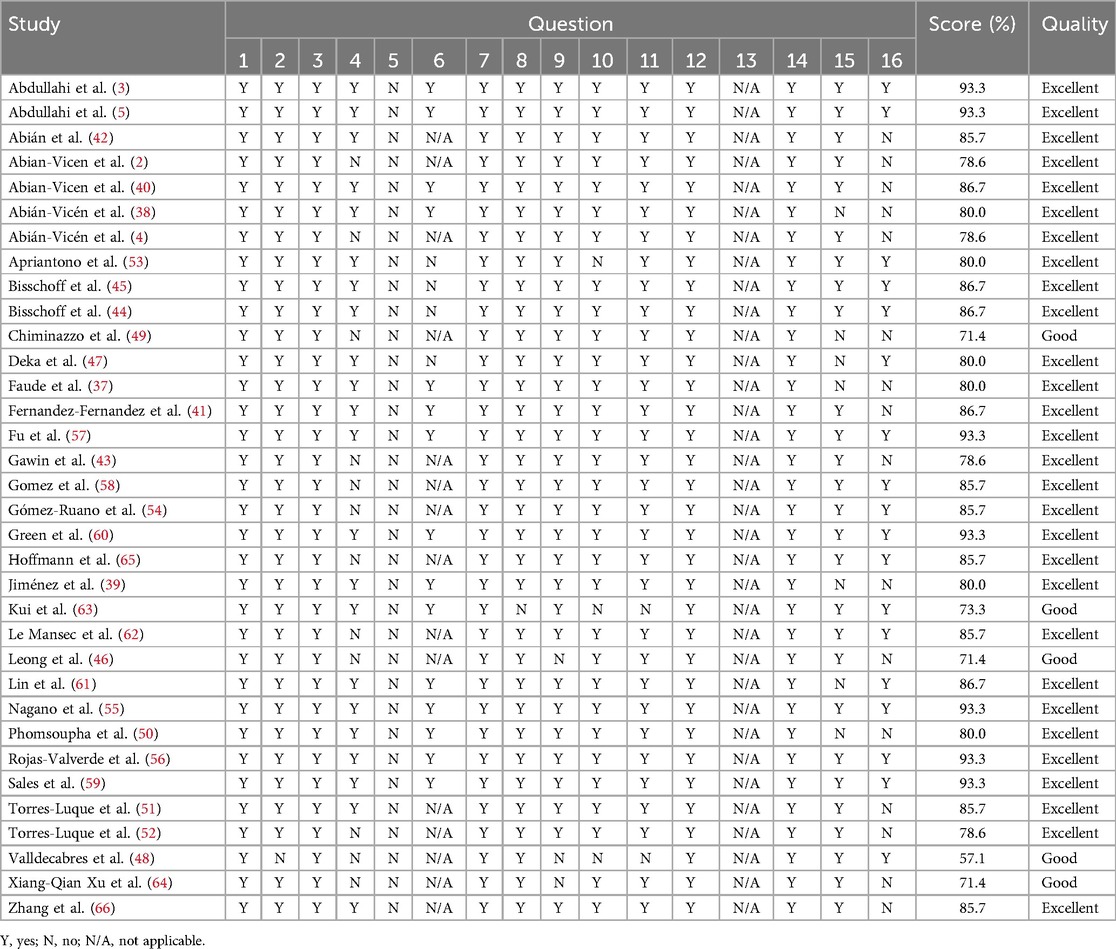

3.2 Study quality of the studies

Table 2 presents the results of the quality assessment of the 34 included studies. The mean quality score was 83.1%. No study had a score of 100%, but 29 studies (2–5, 37–45, 47, 50–62, 65, 66) were rated as excellent quality. Five studies (46, 48, 49, 63, 64) were of good quality; no study was of low quality. Studies with higher scores had practical implications (Question 15) and limitations (Question 16). No study provided drop-out rates, making question 13 always “not applicable”. Fifteen studies (2, 4, 42, 43, 46, 48, 49, 51, 52, 54, 58, 62, 64–66) showed “not applicable” for question 6 owing to their retrospective designs. All studies lost quality points on sample size justification (Question 5), and 12 studies (2, 4, 43, 46, 48, 49, 52, 54, 58, 62, 64, 65) lost points owing to sample description (Question 4).

3.3 Study characteristics

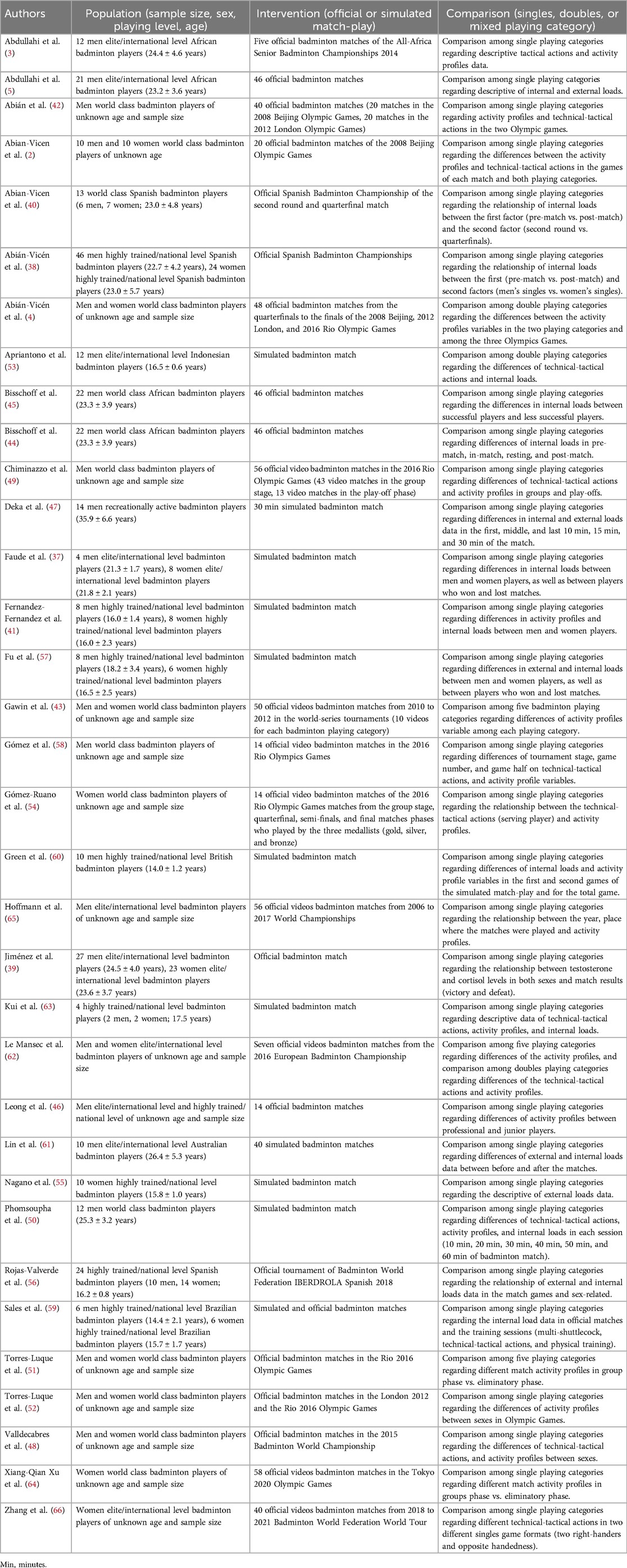

Tables 3–5 summarise the characteristics of the 34 studies using the PICO scheme. Fourteen studies (4, 42, 43, 46, 48, 49, 51, 52, 54, 58, 62, 64–66) did not provide data regarding sample size. The remaining 20 studies reported data on 362 players, including 244 men and 118 women. The mean age of all players was 20.6 ± 4.9 years, with 21.5 ± 5.4 and 18.9 ± 3.5 years for men and women, respectively. Sixteen studies (2, 4, 37–41, 43, 48, 51, 52, 56, 57, 59, 62, 63) investigated men and women; 14 studies (3, 5, 42, 44–47, 49, 50, 53, 58, 60, 61, 65) investigated only men; and four studies (54, 55, 64, 66) reported data on only women. Regarding playing level, world-class players were most frequently observed in 14 studies (2, 4, 40, 42–45, 49–52, 54, 58, 64); twelve studies (3, 5, 37–39, 46, 48, 53, 61, 62, 65, 66) focused on elite/international players; seven (41, 55–57, 59, 60, 63) on highly trained/national players; and one study (47) investigated recreationally active players. No study investigated players at the training or developmental levels.

Table 3. Study characteristics of the 34 included studies concerning the population, intervention, and comparison.

Table 4. Study characteristics of the 34 included studies concerning the match-play outcome measures of singles category in both sexes.

Table 5. Study characteristics of the 34 included studies concerning the match-play outcome measures of the doubles category in both sexes and mixed.

In terms of playing context, official matches were most commonly investigated in 24 studies (2–5, 38–40, 42–46, 48, 49, 51, 52, 54, 56–58, 62, 64–66), followed by simulated matches in nine studies (37, 41, 47, 50, 53, 55, 60, 61, 63). One study (59) analysed official and simulated matches. Regarding playing categories, men's singles were most often investigated in 28 studies (2, 3, 5, 37–52, 56–63, 65), followed by women's singles in 19 studies (2, 37–41, 43, 48, 51, 52, 54–57, 59, 62–64, 66). Fewer studies have been conducted in the doubles categories: men's doubles in five studies (4, 43, 51, 53, 62), women's doubles in four studies (4, 43, 51, 62), and mixed doubles in three studies (43, 51, 62). Concerning outcome measures, most studies focused on activity profiles with eight studies (4, 43, 46, 51, 52, 58, 64, 65), followed by the internal loads with seven studies (37–40, 44, 45, 59). Seven studies (2, 3, 42, 48, 49, 54, 62) combined technical-tactical actions and activity profiles, five studies (5, 47, 56, 57, 61) combined internal and external loads, two studies (41, 60) combined activity profiles and internal loads, two studies (50, 63) combined technical-tactical actions, activity profiles, and internal loads, one study (53) combined technical-tactical actions and internal loads, one study (66) focused on technical-tactical actions only, and one study (55) focused on external loads only.

3.4 Differences in match-play outcome measures

Table 6 summarises the descriptive differences in match-play outcome measures. The outcomes are further specified concerning sexes and playing categories.

Table 6. Descriptive overview of the match-play outcome measures according to the five playing categories in badminton (means and standard deviations).

3.4.1 Differences between singles category in both sexes

Figure 2 shows the individual and overall ESs regarding differences in match-play outcome measures between men's and women's singles categories. Concerning technical-tactical actions, men performed largely more drive (9.9 ± 11.9 vs. 4.6 ± 3.7%; ES = 1.18 ± 0.96) and smash shots (20.3 ± 9.4 vs. 14.6 ± 6.3%; ES = 1.29 ± 0.79) than women. All further individual differences were small (ES = 0.37). The overall ES for technical-tactical actions was small (ES = 0.04 ± 0.43), favouring men's singles. Regarding activity profiles, men had a largely higher effective playing time (34.1 ± 5.3 vs. 29.0 ± 6.6%; ES = 1.13 ± 0.78), longest rally (41.7 ± 1.7 vs. 32.2 ± 4.1 n; ES = 0.86 ± 0.75), shots per rally (8.9 ± 2.1 vs. 6.9 ± 1.1 n; ES = 0.82 ± 0.43), shots per second (1.0 ± 0.2 vs. 0.8 ± 0.2 shots/s; ES = 4.52 ± 1.30), total points played (77.0 ± 7.5 vs. 42.3 ± 20.6 points; ES = 2.71 ± 1.15), and rest time between rallies (22.9 ± 10.6 vs. 17.2 ± 4.4 s; ES = 0.81 ± 0.56) than women. All further differences were small (ES = 0.00). The overall ES for the activity profiles was small (ES = −0.34 ± 0.37), favouring women's singles. No large differences were observed for external loads between men's and women's single categories. However, men executed moderately more acceleration (25.9 ± 0.6 vs. 24.7 ± 0.2 n/min; ES = 0.54 ± 0.72) than women. All further differences were small (ES = 0.11–0.20). The overall ES for the external loads was small (ES = 0.27 ± 0.56), favouring men's singles. Regarding internal loads, men had a largely higher energy expenditure (57.4 ± 15.1 vs. 45.4 ± 0.7 kJ/min; ES = 1.08 ± 1.14) and blood lactate (5.4 ± 3.1 vs. 2.2 ± 0.4 mmol/L; ES = 1.16 ± 0.88) than women. All further differences were small (ES = 0.00–0.20). The overall ES for internal loads was small (ES = 0.34 ± 0.50), favouring men's singles.

Figure 2. Individual and overall ESs and associated 95% confidence intervals with respect to differences between singles category in both sexes regarding (A) technical-tactical actions, (B) activity profiles, and (C) external and (D) internal loads. The dashed vertical lines present thresholds for small effect sizes; solid lines present zero effect sizes. BPM, beats per minutes; kJ/min, kilojoule per minute; km/h, kilometre per hour; L/h, liters per hour; m/min, meter per minute; mmol/L, millimole per liter; n/min, newton per minute; n, number; n/s, number per seconds; pH, potential of hydrogen; s, seconds.

3.4.2 Differences between the doubles category in both sexes and mixed

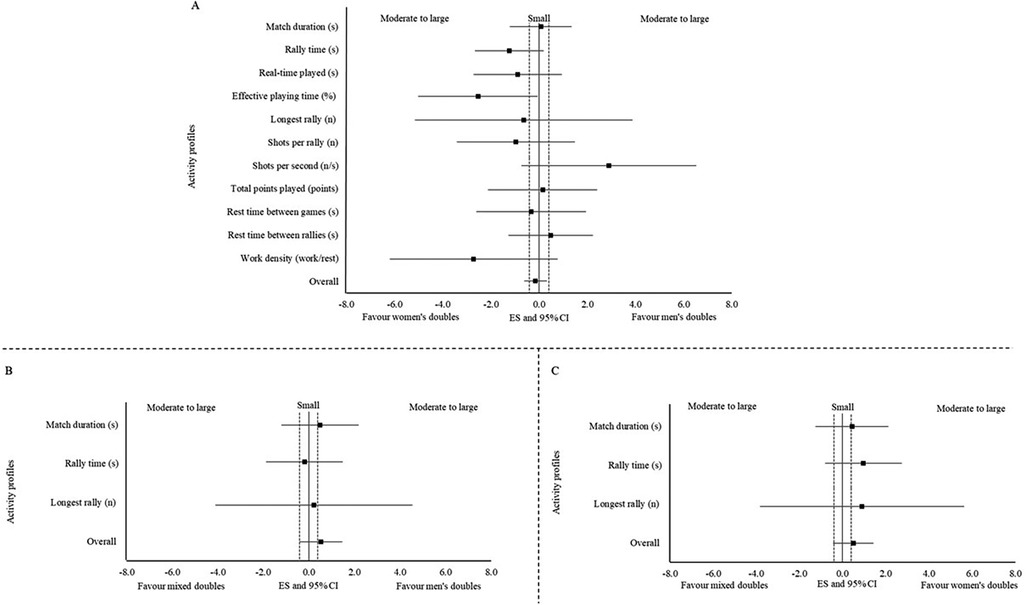

Figure 3 shows the individual and overall ESs for differences in doubles categories between sexes and mixed activity profiles. Regarding activity profiles between men's and women's doubles categories, men's doubles categories performed largely more shots per second (1.5 ± 0.0 vs. 1.3 ± 0.1 n/s; ES = 2.90 ± 1.31) than women's doubles. Furthermore, men's doubles had moderately higher rest time between rallies (24.9 ± 3.4 vs. 22.8 ± 4.0 s; ES = 0.48 ± 0.72) than women's doubles. All further differences were small (ES = 0.07–0.15). The overall ES for the activity profiles was small (ES = −0.15 ± 0.24), favouring women's doubles. Regarding activity profiles between men's and mixed doubles categories, men's doubles had a moderately higher match duration (3,106.2 ± 665.0 vs. 2,653.0 ± 176.5 s; ES = 0.49 ± 0.72) than mixed doubles. All further differences were small (ES = 0.23). The overall ES for the activity profiles was moderate (ES = 0.54 ± 0.45), favouring men's doubles. Regarding activity profiles between women's and mixed doubles categories, women's doubles had a largely higher rally time (9.7 ± 0.9 vs. 6.8 ± 1.1 s; ES = 0.97 ± 0.75), and longest rally (57.4 ± 1.4 vs. 39.0 ± 3.1 n; ES = 0.90 ± 1.10) than the mixed doubles. Furthermore, women's doubles had moderately higher match duration (3,040.1 ± 743.0 vs. 2,653.0 ± 176.5 s; ES = 0.44 ± 0.72), than the mixed doubles. The overall ES for activity profiles was moderate (ES = 0.50 ± 0.45), favouring women's doubles.

Figure 3. Individual and overall ESs and associated 95% confidence intervals with respect to differences between the doubles category in (A) both sexes, (B) men's and mixed, and (C) women's and mixed regarding the activity profiles. The dashed vertical lines present thresholds for small effect sizes; solid lines present zero effect sizes. n, number; n/s, number per seconds; s, seconds.

3.4.3 Differences between singles and doubles categories in both sexes

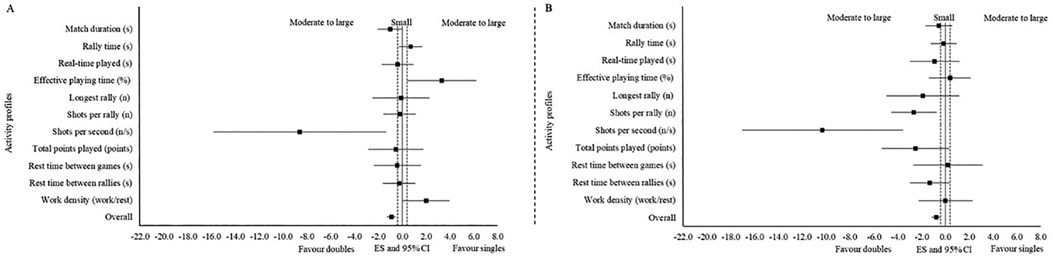

Figure 4 shows the individual and overall ESs with respect to differences in the single- and double-categories between sexes regarding activity profiles. In men's activity profiles, singles categories had a largely higher effective playing time (34.1 ± 5.3 vs. 19.2 ± 2.3%; ES = 3.32 ± 1.19) and work density (0.4 ± 0.1 vs. 0.2 ± 0.0 work/rest; ES = 2.00 ± 0.85) than doubles categories. Furthermore, singles categories had moderately higher rally time (8.8 ± 2.0 vs. 6.5 ± 0.7 s; ES = 0.69 ± 0.48) than doubles categories. The overall ES for activity profiles was large (ES = −0.90 ± 0.20), favouring doubles categories. No large differences were observed in women's activity profiles. All further differences were small (ES = 0.00–0.38). The overall ES for activity profiles was large (ES = −0.76 ± 0.21), favouring doubles categories.

Figure 4. Individual and overall ESs and associated 95% confidence intervals with respect to differences between singles and doubles categories in (A) men and (B) women regarding the activity profiles. The dashed vertical lines present thresholds for small effect sizes; solid lines present zero effect sizes. n, number; n/s, number per seconds; s, seconds.

4 Discussion

This systematic review is the first to investigate differences in match-play data according to the five playing categories in badminton. The main finding was that each playing category places specific demands on the players, which are important to consider when optimising training and testing procedures.

No previous systematic review of match-play data in badminton directly supports our findings. The only previous systematic review of badminton focused on health outcomes (19). Additionally, two other previous reviews focused on a similar topic to ours, but one of them was conducted narratively (1) and the other solely focused on internal loads across several racquet sports (20). In our review, we discovered that most studies investigated men and world-class players during official matches. Compared with other playing categories, men's singles were investigated most often. Moreover, most studies focused on activity profiles as an outcome measure. Therefore, research on women, recreationally active players, doubles categories, and external load measures is lacking. This research gap should be addressed by future studies. With this in mind, advanced methodological approaches may be helpful to investigate match-play data more profoundly in each of the five playing categories during the next years. For example, conducting cross-sectional and longitudinal studies on women, recreationally active players, and doubles categories by utilizing wearable technology such as local positioning systems (67) for external, and also extrapolated internal (metabolic) load measures (68) may contribute to close the here observed research gab.

In the men's singles category, the overall ESs for match-play data regarding technical-tactical actions, activity profiles, and external and internal loads showed only small differences (ES = −0.34 to 0.34) compared with women's singles (Figures 2A–D). However, some individual ESs showed up to large differences (ES ≤ 4.52), favouring the men's single category. For instance, men performed moderately to largely more drive shots, smash shots, accelerations, effective playing time, longest rallies, shots per rally, shots per second, total points played, and rest time between rallies than women. Additionally, men had a largely higher energy expenditures and blood lactate than women (Figure 2D). These observations are supported by a previous review stating that men's singles exhibit more aggressive attacking characteristics and are more physically demanding than women's singles (1, 2, 41–43, 48, 52). Thus, men's singles often require longer rest times between rallies (1). Differences in particularly muscular performance between men and women can explain these findings (69). A larger muscle mass allows men to engage in more aggressive play than women (69). Consequently, men's singles players need longer recovery time to maintain high energy levels for continued aggressive attacks (1, 70). Overall, these outcomes suggest that men's singles matches are characterised by more aggressive attacks at higher intensities during rallies, interspersed with longer recovery times than women's singles.

Regarding sex differences in the singles categories, some individual ESs also showed up to large differences (ES ≤ −1.63), favouring the women's single category (Figure 2A). For instance, women performed moderately to largely more drop shots, clear shots, real-time play, rest time between games and had a higher average heart rate than men (Figures 2B, D). These results are supported by previous studies stating that the women's singles category tends to be more defensive with a dominance of smoother shots than men's singles, resulting in longer real-time play (1, 2, 41, 43, 51, 52). In contrast, Valldecabres et al. (48) showed that the women's singles category was dominant in executing powerful shots (such as drive shots) compared with the men's singles category. However, this study (48) was based only on final matches, whereas other studies focused on matches across all phases (43, 51, 52). Sex differences in muscle masses (71) and hormones (69, 72) as well as cardiovascular (73) and neuro-muscular characteristics (74) including aerobic and anaerobic capacities (75) may contribute to the variations observed the in activity profiles between women and men. For example, women's singles players, characterized by lesser muscle mass, engage in less aggressive play with longer rallies (69). Consequently, defensive characteristics are more evident in women's singles (1, 2). Overall, the outcomes suggest that the women's singles category is characterised by a more defensive play with smoother shoots, leading to longer real-time plays than in men's singles.

In the doubles category, the overall ESs for the activity profiles were small to moderate (ES = −0.15, 0.50), favouring women's doubles over men's and mixed doubles, respectively (Figures 3A, C). Specifically, some individual ESs showed up to large differences (ES ≤ −2.72), favouring the women's doubles category (Figure 3A). The overall ES for activity profiles was moderate (ES = 0.54), favouring men's doubles over mixed doubles (Figure 3B). In contrast, the overall ESs for activity profiles were large (ES = −0.76 to −0.90), favouring the doubles category for both sexes (Figures 4A, B). These results are supported by previous studies (4, 43, 51, 53). For example, Gawin et al. (43) stated that the work density of women (30.1%) was greater than that of men and mixed doubles (approximately 20% for each). This statement supports our findings, where our results (ES = −2.72) showed that women's doubles had a largely higher work density than men's doubles (Figure 3A). No comparison of work density between women and mixed doubles was observed; however, rally time (ES = 0.97) was largely higher in women's doubles than in mixed doubles. A previous study assumed that shortening coverage areas could intensify match play by increasing shot frequency (4). This statement is supported by our findings, where shots per rally and shots per seconds showed up to large differences (ES ≤ −10.31), favouring the doubles category for both sexes (Figure 4B). These results suggest that the shortening coverage area prompts double players to hit the shuttlecocks earlier, thereby increasing shot frequency. Overall, the outcomes suggest that women's doubles categories have greater work density and rally time than men's and mixed doubles categories. Additionally, the results of activity profiles showed an increase in shot frequency for the doubles compared to the singles category, but no clear conclusion concerning the playing demands in doubles are possible due to a lack of external and internal load measures on an individual player level yet.

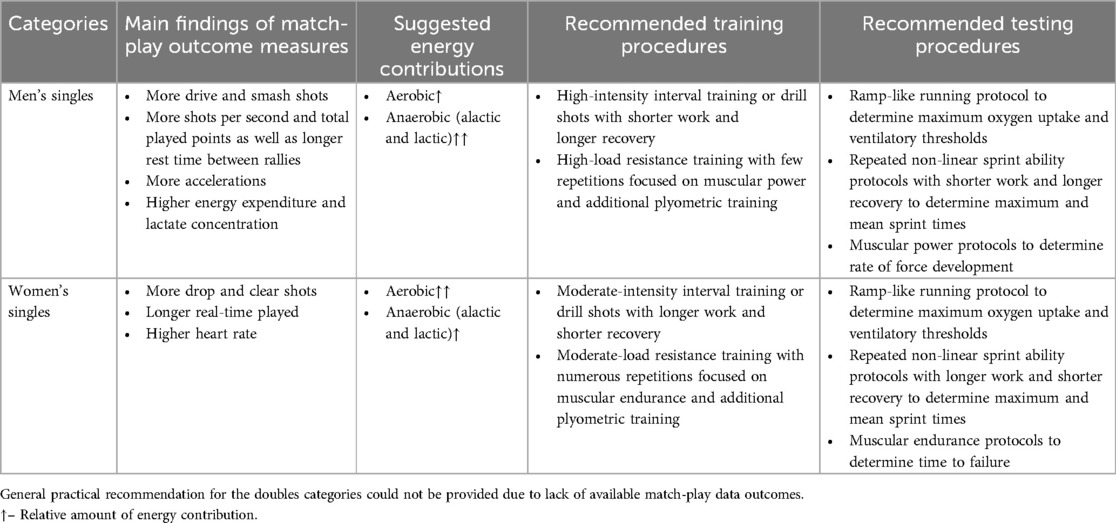

Overall, these findings support that badminton shares some demands in common with further racquet sports as tennis and squash (76). However, our subgroup analysis indicates that each category in badminton places specific demands on players. From a practical perspective, our results can serve as a framework to design training, testing and talent identification procedures in badminton. As a general implementation, we carefully recommend such practical aspects based on our main findings summarized in Table 7. Specifically, these recommendations were derived from our match-play data outcomes measure of each category. Therefore, suggested energy contributions serve as foundation for guiding training and testing procedures, which should be worked out by badminton experts. However, our general recommendations should be treated with caution due to the large 95% confidence intervals of some ESs (e.g., longest rally, shots per second, and energy expenditure), indicating a large heterogeneity of the underlying data, which limits a generalization. Therefore, more research is needed not only to prove the observed heterogeneity, but also to evaluate the provided general recommendations, as we have not investigated them here.

Table 7. General practical recommendations for training and testing procedures for men's and women's singles according to main findings of our study.

This systematic review had several limitations. First, a meta-analysis could not be conducted due to the large heterogeneity of the included studies and their data. However, ESs were calculated as an established alternative statistical approach (27, 28). Second, we did not investigate differences in playing levels between players, because this would have significantly exceeded the scope of our review. Therefore, further studies are needed to address these issues.

5 Conclusion

There are differences in match-play data according to the five playing categories in badminton, each category placing specific demands on the players. Men's singles are characterised by explosive movements at high intensity, indicating that not only a high aerobic, but also a sufficient amount of anaerobic capacity is needed. In contrast, women's singles are characterised by more defensive play and smoother shoots, suggesting a greater aerobic demand compared to men's singles. In the doubles category, the frequency of shots is increased, but no clear conclusion concerning the playing demands are possible due to a lack of outcome measures on an individual player level. Nevertheless, specific training and testing procedures are essential for the players to prepare them according to the specific demands of each category, what should be considered by scientists and coaches.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

BW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft. JB: Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. TA: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. MH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Open access funding provided by the Open Access Publishing Fund of Philipps-Universität Marburg.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Badminton World Federation (BWF) for their support of this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Phomsoupha M, Laffaye G. The science of badminton: game characteristics, anthropometry, physiology, visual fitness and biomechanics. Sports Med. (2015) 45:473–95. doi: 10.1007/s40279-014-0287-2

2. Abian-Vicen J, Castanedo A, Abian P, Sampedro J. Temporal and notational comparison of badminton matches between men’s singles and women’s singles. Int J Perform Anal Sport. (2013) 13:310–20. doi: 10.1080/24748668.2013.11868650

3. Abdullahi Y, Coetzee B. Notational singles match analysis of male badminton players who participated in the African badminton championships. Int J Perform Anal Sport. (2017) 17:1–16. doi: 10.1080/24748668.2017.1303955

4. Abián-Vicén J, Sánchez L, Abián P. Performance structure analysis of the men’s and women’s badminton doubles matches in the Olympic Games from 2008 to 2016 during playoffs stage. Int J Perform Anal Sport. (2018) 18:633–44. doi: 10.1080/24748668.2018.1502975

5. Abdullahi Y, Coetzee B, Van Den Berg L. Relationships between results of an internal and external match load determining method in male singles badminton players. J Strength Cond Res. (2019) 33:1111–8. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000002115

6. Madsen CM, Karlsen A, Nybo L. Novel speed test for evaluation of badminton-specific movements. J Strength Cond Res. (2015) 29:1203–10. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000635

7. Abián-Vicén J, Bravo-Sánchez A, Abián P. AIR-BT, a new badminton-specific incremental easy-to-use test. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0257124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0257124

8. Wonisch M, Hofmann P, Schwaberger G, Von Duvillard SP. Validation of a field test for the non-invasive determination of badminton specific aerobic performance. Br J Sports Med. (2003) 37:115–8. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.37.2.115

9. Hoppe MW, Hotfiel T, Stückradt A, Grim C, Ueberschär O, Freiwald J, et al. Effects of passive, active, and mixed playing strategies on external and internal loads in female tennis players. PLoS One. (2020) 15:e0239463. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239463

10. Helwig J, Diels J, Röll M, Mahler H, Gollhofer A, Roecker K, et al. Relationships between external, wearable sensor-based, and internal parameters: a systematic review. Sensors (Basel). (2023) 23:827. doi: 10.3390/s23020827

11. Murphy AP, Duffield R, Kellett A, Reid M. A descriptive analysis of internal and external loads for elite-level tennis drills. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. (2014) 9:863–70. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2013-0452

12. Impellizzeri FM, Marcora SM. Test validation in sport physiology: lessons learned from clinimetrics. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. (2009) 4:269–77. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.4.2.269

13. Pearce A. A physiological and notational comparison of the conventional and new scoring systems in badminton. J Hum Mov Stud. (2002) 43:49–67.

14. Cabello Manrique D, González JJ, Cabello M. Analysis of the characteristics of competitive badminton. Br J Sports Med. (2003) 37:62–6. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.37.1.62

15. Laffaye G, Phomsoupha M, Dor F. Changes in the game characteristics of a badminton match: a longitudinal study through the Olympic Game finals analysis in men’s singles. J Sports Sci Med. (2015) 14:584–90. Available online at: http://www.jssm.org.26335338

16. Bartlett JD, O’connor F, Pitchford N, Torres-Ronda L, Robertson SJ. Relationships between internal and external training load in team-sport athletes: evidence for an individualized approach. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. (2017) 12:230–4. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2015-0791

17. Edel A, Weis JL, Ferrauti A, Wiewelhove T. Training drills in high performance badminton-effects of interval duration on internal and external loads. Front Physiol. (2023) 14:1189688. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2023.1189688

18. Edel A, Vuong JL, Kaufmann S, Hoos O, Wiewelhove T, Ferrauti A. Metabolic profile in elite badminton match play and training drills. Eur J Sport Sci. (2024) 24(11):1639–1652. doi: 10.1002/ejsc.12196

19. Cabello-Manrique D, Lorente JA, Padial-Ruz R, Puga-González E. Play badminton forever: a systematic review of health benefits. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:9077. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19159077

20. Cádiz Gallardo MP, Pradas De La Fuente F, Moreno-Azze A, Carrasco Páez L. Physiological demands of racket sports: a systematic review. Front Psychol. (2023) 30:1149295. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1149295

21. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. (2009) 6:e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100

22. Lee Ming C, Keong Chen C, Kumar Ghosh A, Chee Keong C. Time motion and notational analysis of 21 point and 15 point badminton match play. Int J Sports Sci Eng. (2008) 02:216–22. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242527916.

23. Sarmento H, Clemente FM, Araújo D, Davids K, Mcrobert A, Figueiredo A. What performance analysts need to know about research trends in association football (2012–2016): a systematic review. Sports Med. (2018) 48:799–836. doi: 10.1007/s40279-017-0836-6

24. Low B, Coutinho D, Gonçalves B, Rein R, Memmert D, Sampaio J. A systematic review of collective tactical behaviours in football using positional data. Sports Med. (2020) 50:343–85. doi: 10.1007/s40279-019-01194-7

25. McKay AKA, Stellingwerff T, Smith ES, Martin DT, Mujika I, Goosey-Tolfrey VL, et al. Defining training and performance caliber: a participant classification framework. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. (2022) 17:317–31. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2021-0451

26. Glass GV. Integrating Findings: The Meta-analysis of Research. Washington, DC: American Educational Research (1977).

27. Engel FA, Holmberg HC, Sperlich B. Is there evidence that runners can benefit from wearing compression clothing? Sports Med. (2016) 46:1939–52. doi: 10.1007/s40279-016-0546-5

28. Swinton PA, Burgess K, Hall A, Greig L, Psyllas J, Aspe R, et al. Interpreting magnitude of change in strength and conditioning: Effect size selection, threshold values and Bayesian updating. J Sports Sci. (2022) 40:2047–54. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2022.2128548

29. Wasserman S, Hedges LV, Olkin I. Statistical methods for meta-analysis. JSTOR. (1988) 13:75. doi: 10.2307/1164953

30. Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page M, et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2nd edn. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons (2019).

31. Faccini P, Dal Monte A. Physiologic demands of badminton match play. Am J Sports Med. (1996) 24:S64–6. doi: 10.1177/036354659602406S19

32. Liddle SD, Murphy MH. A comparison of the physiological demands of singles and doubles badminton: a heart rate and time/motion analysis. J Hum Mov Stud. (1996) 30:159–76. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237081096.

33. Majumdar P, Khanna GL, Malik V, Sachdeva S, Arif M, Mandal M. Physiological analysis to quantify training load in badminton. BrJ Sports Med. (1997) 31:342–5. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.31.4.342

34. Tong Y-M, Hong Y. The playing pattern of world’s top single badminton players. 18 International Symposium on Biomechanics in Sports (2000).

35. Alcock A, Cable NT. A comparison of singles and doubles badminton: heart rate response, player profiles and game characteristics. Int J Perform Anal Sport. (2009) 9:228–37. doi: 10.1080/24748668.2009.11868479

36. Chen H-L, Wu C-J, Chen TC. Physiological and notational comparison of new and old scoring systems of singles matches in men’s badminton. Asian J Phys Educ Recreat. (2011) 17:6–17. doi: 10.24112/ajper.171882

37. Faude O, Meyer T, Rosenberger F, Fries M, Huber G, Kindermann W. Physiological characteristics of badminton match play. Eur J Appl Physiol. (2007) 100:479–85. doi: 10.1007/s00421-007-0441-8

38. Abián-Vicén J, Del Coso J, González-Millán C, Salinero JJ, Abián P. Analysis of dehydration and strength in elite badminton players. PLoS One. (2012) 7:e37821. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037821

39. Jiménez M, Aguilar R, Alvero-Cruz JR. Effects of victory and defeat on testosterone and cortisol response to competition: evidence for same response patterns in men and women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2012) 37:1577–81. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.02.011

40. Abian-Vicen J, Castanedo A, Abian P, Gonzalez-Millan C, Salinero JJ, Del Coso J. Influence of successive badminton matches on muscle strength, power, and body-fluid balance in elite players. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. (2014) 9:689–94. doi: 10.1123/IJSPP.2013-0269

41. Fernandez-Fernandez J, De La Aleja Tellez JG, Moya-Ramon M, Cabello-Manrique D, Mendez-Villanueva A, Hernandez M. Gender differences in game responses during badminton match play. J Strength Cond Res. (2013) 27:2396–404. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31827fcc6a

42. Abián P, Castanedo A, Feng XQ, Sampedro J, Abian-Vicen J. Notational comparison of men’s singles badminton matches between Olympic Games in Beijing and London. Int J Perform Anal Sport. (2014) 14:42–53. doi: 10.1080/24748668.2014.11868701

43. Gawin W, Beyer C, Seidler M. A competition analysis of the single and double disciplines in world-class badminton. Int J Perform Anal Sport. (2015) 15:997–1006. doi: 10.1080/24748668.2015.11868846

44. Bisschoff CA, Coetzee B, Esco MR. Relationship between autonomic markers of heart rate and subjective indicators of recovery status in male, elite badminton players. J Sports Sci Med. (2016) 15:658–69. Available online at: http://www.jssm.org.27928212

45. Bisschoff CA, Coetzee B, Esco MR. Heart rate variability and recovery as predictors of elite, African, male badminton players’ performance levels. Int J Perform Anal Sport. (2018) 18:1–16. doi: 10.1080/24748668.2018.1437868

46. Leong KL, Krasilshchikov O. Match and game performance structure variables in elite and youth international badminton players. J Phys Educ Sport. (2016) 16:330–4. doi: 10.7752/jpes.2016.02053

47. Deka P, Berg K, Harder J, Batelaan H, Mcgrath M. Oxygen cost and physiological responses of recreational badminton match play. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. (2017) 57:760–5. doi: 10.23736/S0022-4707.16.06319-2

48. Valldecabres R, De Benito AM, Casal CA, Pablos C. 2015 Badminton world championship: singles final men’s vs women’s behaviours. J Hum Sport Exerc. (2017) 12:775–88. doi: 10.14198/JHSE.2017.12.PROC3.01

49. Chiminazzo JGC, Barreira J, Luz LSM, Saraiva WC, Cayres JT. Technical and timing characteristics of badminton men’s single: comparison between groups and play-offs stages in 2016 Rio Olympic Games. Int J Perform Anal Sport. (2018) 18:245–54. doi: 10.1080/24748668.2018.1463785

50. Phomsoupha M, Ibrahime S, Heugas A, Laffaye G. Physiological, neuromuscular and perceived exertion responses in badminton games. Int J Racket Sports Sci. (2019) 1:16–25. doi: 10.30827/Digibug.57323

51. Torres-Luque G, Fernández-García ÁI, Blanca-Torres JC, Kondric M, Cabello-Manrique D. Statistical differences in set analysis in badminton at the RIO 2016 Olympic games. Front Psychol. (2019) 10:731. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00731

52. Torres-Luque G, Carlos Blanca-Torres J, Cabello-Manrique D, Kondric M. Statistical comparison of singles badminton matches at the London 2012 and Rio De Janeiro 2016 Olympic games. J Hum Kinet. (2020) 75:177–84. doi: 10.2478/hukin-2020-0046

53. Apriantono T, Herman I, Winata B, Hidayat II, Hasan MF, Juniarsyah AD, et al. Physiological characteristics of Indonesian junior badminton players: men’s double category. Int J Hum Mov Sports Sci. (2020) 8:444–54. doi: 10.13189/saj.2020.080617

54. Gómez-Ruano MÁ, Cid A, Rivas F, Ruiz LM. Serving patterns of women’s badminton medallists in the Rio 2016 Olympic Games. Front Psychol. (2020) 11:136. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00136

55. Nagano Y, Sasaki S, Higashihara A, Ichikawa H. Movements with greater trunk accelerations and their properties during badminton games. Sports Biomech. (2020) 19:342–52. doi: 10.1080/14763141.2018.1478989

56. Rojas-Valverde D, Gómez-Carmona CD, Fernández-Fernández J, García-López J, García-Tormo V, Cabello-Manrique D, et al. Identification of games and sex-related activity profile in junior international badminton. Int J Perform Anal Sport. (2020) 20:323–38. doi: 10.1080/24748668.2020.1745045

57. Fu Y, Liu Y, Chen X, Li Y, Li B, Wang X, et al. Comparison of energy contributions and workloads in male and female badminton players during games versus repetitive practices. Front Physiol. (2021) 12:640199. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.640199

58. Gómez MA, Cid A, Rivas F, Barreira J, Chiminazzo JGC, Prieto J. Dynamic analysis of scoring performance in elite men’s badminton according to contextual-related variables. Chaos Solitons Fractals. (2021) 151:111295. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2021.111295

59. Sales KCG, Santos MAP, Nakamura FY, Silvino VO, Da Costa Sena AF, Ribeiro SLG, et al. Official matches and training sessions: physiological demands of elite junior badminton players. Motriz Rev Educ Fisica. (2021) 27:e1021021520. doi: 10.1590/S1980-65742021021520

60. Green R, West AT, Willems MET. Notational analysis and physiological and metabolic responses of male junior badminton match play. Sports (Basel). (2023) 11:35. doi: 10.3390/sports11020035

61. Lin Z, Blazevich AJ, Abbiss CR, Wilkie JC, Nosaka K. Neuromuscular fatigue and muscle damage following a simulated singles badminton match. Eur J Appl Physiol. (2023) 123:1229–40. doi: 10.1007/s00421-023-05148-w

62. Mansec L, Boiveau Y, Doron M, Jubeau J. Double analysis during high-level badminton matches: different activities within the pair? Int J Racket Sports Sci. (2023) 5(1):14–22.

63. Kui WSW, Ler HY, Woo MT. Physical fitness profile and match analysis of elite junior badminton players: case studies. In: Syed Omar SF, Hassan MHA, Casson A, Godfrey APP, Abdul Majeed A, editors. Innovation and Technology in Sports. Malaysia: Springer (2023). p. 21–5.

64. Xu XQ, Korobeynikov G, Han W, Dutchak M, Nikonorov D, Zhao M, et al. Analysis of phases and medalists to women’s singles matches in badminton at the Tokyo, 2020 Olympic Games. Slobozhanskyi Her Sci Sport. (2023) 27:64–9. doi: 10.15391/snsv.2023-2.002

65. Hoffmann D, Vogt T. Does a decade of the rally-point scoring system impact the characteristics of elite badminton matches? Int J Perform Anal Sport. (2024) 24:105–18. doi: 10.1080/24748668.2023.2272121

66. Zhang Y, Leng B. Performance of elite women’s singles badminton players: the influence of left-handed players. J Hum Kinet. (2024) 92:239–49. doi: 10.5114/jhk/172783

67. Alt PS, Baumgart C, Ueberschär O, Freiwald J, Hoppe MW. Validity of a local positioning system during outdoor and indoor conditions for team sports. Sensors (Switzerland). (2020) 20:1–11. doi: 10.3390/s20205733

68. Brochhagen J, Hoppe MW. Metabolic power in team and racquet sports: a systematic review with best-evidence synthesis. Sports Med Open. (2022) 8:133. doi: 10.1186/s40798-022-00525-9

69. Lewis DA, Kamon E, Hodgson JL. Physiological differences between genders implications for sports conditioning. Sports Med. (1986) 3:357–69. doi: 10.2165/00007256-198603050-00005

70. Rampichini S, Limonta E, Pugliese L, Cè E, Bisconti AV, Gianfelici A, et al. Heart rate and pulmonary oxygen uptake response in professional badminton players: comparison between on-court game simulation and laboratory exercise testing. Eur J Appl Physiol. (2018) 118:2339–47. doi: 10.1007/s00421-018-3960-6

71. Bredella MA. Sex differences in body composition. In: Mauvais-Jarvis F, editor. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. New York LLC: Springer (2017). p. 9–27. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-70178-3_2

72. Nuzzo JL. Narrative review of sex differences in muscle strength, endurance, activation, size, fiber type, and strength training participation rates, preferences, motivations, injuries, and neuromuscular adaptations. J Strength Cond Res. (2022) 37:494–536. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000004329

73. Afaghi S, Rahimi FS, Soltani P, Kiani A, Abedini A. Sex-Specific differences in cardiovascular adaptations and risks in elite athletes: bridging the gap in sports cardiology. Clin Cardiol. (2024) 47:e70006. doi: 10.1002/clc.70006

74. Nuzzo JL. Sex differences in skeletal muscle fiber types: a meta-analysis. Clin Anatomy. (2024) 37:81–91. doi: 10.1002/ca.24091

75. Nikolaidis PT, Knechtle B. Participation and performance characteristics in half-marathon run: a brief narrative review. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. (2023) 44:115–22. doi: 10.1007/s10974-022-09633-1

Keywords: game characteristics, metabolism, notational analysis, physical demands, physiology, racquet sports

Citation: Winata B, Brochhagen J, Apriantono T and Hoppe MW (2025) Match-play data according to playing categories in badminton: a systematic review. Front. Sports Act. Living 7:1466778. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2025.1466778

Received: 22 July 2024; Accepted: 13 February 2025;

Published: 26 February 2025.

Edited by:

Rafael Martínez-Gallego, University of Valencia, SpainReviewed by:

Carlos David Gómez-Carmona, University of Zaragoza, SpainAlejandro Zurano Clemente, Universidad CEU Cardenal Herrera, Spain

Manrique De Jesús Rodríguez Campos, University of Valencia, Valencia, Spain, in collaboration with reviewer [AZC]

Copyright: © 2025 Winata, Brochhagen, Apriantono and Hoppe. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Matthias Wilhelm Hoppe, bWF0dGhpYXMuaG9wcGVAdW5pLW1hcmJ1cmcuZGU=

Bagus Winata

Bagus Winata Joana Brochhagen

Joana Brochhagen Tommy Apriantono

Tommy Apriantono Matthias Wilhelm Hoppe

Matthias Wilhelm Hoppe