- 1Department of Wellness and Sport Sciences, Millersville University, Millersville, PA, United States

- 2Department of Exercise Science and Athletic Training, Springfield College, Springfield, MA, United States

Introduction: As individuals with occupational status and power, sport leaders (e.g., coaches and athletic administrators) are responsible for enforcing cultures of inclusion within institutions of athletics. Yet, sport leaders who possess LGBTQ+ sexual identities are frequently marginalized and stigmatized by entities within and outside of athletics (e.g., athletes, parents of athletes, colleagues). Therefore, LGBTQ+ sport leaders are often faced with a challenging set of circumstances: negotiate the authenticity of their sexual orientation in the context of sport, or leave the profession entirely.

Methods: The purpose of this study was to conduct a systematic review of research related to LGBTQ+ sport leader experiences. Using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA), research across six countries (China/Taiwan/Hong Kong, Italy, New Zealand, Norway, United Kingdom, United States) between 1997 and 2021 was analyzed.

Results: Themes across included studies (N = 34) describe intrapersonal experiences of LGBTQ+ sport leaders, interpersonal studies examining stakeholder attitudes (i.e., parents and athletes) toward LGBTQ+ sport leaders, and sport manager attitudes toward LGBTQ+ topics.

Discussion: Findings convey that sport leaders continue to face marginalization due to the presence of heterosexism and heteronormativity in athletics. Future research should continue to explore LGBTQ+ sport leader experiences, behaviors, attitudes, and identities to determine their impact on fostering inclusion and belonging within athletic spaces.

1 Introduction

Research on lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+1) identities in sport has expanded tremendously over the previous decade (1). Reviews of LGTBQ+ scholarship in sport-related disciplines have identified a wide range of topic areas that have been examined, including athlete experiences and identities; policy, management, and advocacy; and experiences of sexual prejudice, discrimination, and homophobia among others (1–3). Notably, an understudied area within this scholarship regards the experiences of LGBTQ+ sport leaders, including coaches and athletic administrators (1, 4).

Although there are some indications of LGBTQ+ experiences in and across sport improving [e.g., increased prevalence of athletes coming out and promoting LGBTQ+ social justice initiatives (5–8)], LGBTQ+ sport leaders continue to report marginalization and stigmatization in the context of sport (9, 10). For instance, LGBTQ+ coaches and administrators encounter discrimination on an everyday basis from athletes, parents, colleagues, and other stakeholders (11–13). These discriminatory behaviors can be overt in nature, consisting of homophobic comments (14) or negative recruitment strategies [e.g., “gay bashing” (15)]. Discrimination can also occur through covert actions, such as the lack of intervention when LGBTQ+ individuals encounter homophobic remarks (16), or the avoidance of discussing LGBTQ+ identities [e.g., “Don't Ask, Don't Tell” attitudes (13, 17, 18)]. Whether overt or covert in nature, this discrimination is rooted in heterosexism, a system of attitudes and beliefs carried out through structural practices and interpersonal behaviors to reinforce heterosexuality as the norm [i.e., heteronormativity (19)]; thereby labeling LGBTQ+ individuals as “other” and “deviant” (20).

Ultimately, encountering heterosexism at a structural level and stigmatization and/or discrimination at an interpersonal level has led to many LGBTQ+ sport leaders leaving the profession (15, 21), or negotiating their identities in the workplace (20, 22). These negotiations include: dressing or acting in a stereotypically feminine (16) or masculine (23) manner, concealing or compartmentalizing personal lives from professional lives (13, 24), and prioritizing professional identities over sexual orientation (25). These strategies enable sport leaders to successfully navigate their occupational environments in light of their marginalized sexual orientation.

Sport leaders uphold a variety of occupational responsibilities; broadly, they oversee the implementation of policies and practices within their organizations, athletic departments, and/or teams (26). They also possess the status and power to influence organizational culture related to diversity, equity, and inclusion [DEI; (27)]—especially by what they say or fail to say in relation to DEI topics, issues, and initiatives (18, 28, 29). Because sport leaders retain occupational status and power in their respective roles and organizations, it is necessary to explore potential resistances and opportunities for action related to LGBTQ+ topics (7, 30). Thus, developing a holistic understanding of existing research is critical, especially as it pertains to the experiences of LGBTQ+ sport leaders, and sport leaders’ attitudes regarding LGBTQ+ issues.

The purpose of this study was to conduct a systematic review of research related to LGBTQ+ sport leader experiences, stakeholder attitudes toward current or former LGBTQ+ sport leaders, and the attitudes of sport leaders toward LGBTQ+ issues using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). The current study responds to calls for additional research on LGBTQ+ topics for sport leaders, including coaches, administrators, and managers (1, 3, 4). By critically examining previous scholarship, this systematic review provides next steps for research related to LGBTQ+ sport leaders and LGBTQ+ inclusive leadership practices.

2 Methods

2.1 Search process

A systematic review was conducted by searching six databases (SPORTDiscus, PsycINFO, Business Source Complete, ERIC, SocINDEX, and Academic Search Complete). Databases were selected based on their alignment with the topic area for this study (i.e., SPORTDiscus, PsycINFO, Business Source Complete, ERIC, SocINDEX) and their breadth of scholarly research (i.e., Academic Search Complete) in order to ensure relevant scholarship was included. The following keyword combinations were used: ““gay or lesbian or bisexual or homosexual or “same sex” or transgender or queer or GLBT or LGBT or LGBTQ or LGBTQ+”” AND ““sport or athletics or team or basketball or soccer or lacrosse or swimming or diving or track or “track and field” or volleyball or “field hockey” or hockey or wrestling or gymnastics or golf or tennis or football or crew or fencing or softball or baseball or rugby”” AND “management or manager or director or administrator or administration or coach* or sport coach*”. Articles were also hand-searched to include relevant studies not found in the initial search process, resulting in the addition of three references. The original search process took place between September and November of 2021. The search was subsequently updated in September of 2022 and May of 2024 to confirm no new scholarship meeting inclusion criteria had been published since the original search. Both updated searches did not yield any scholarship that met inclusion criteria for this study.

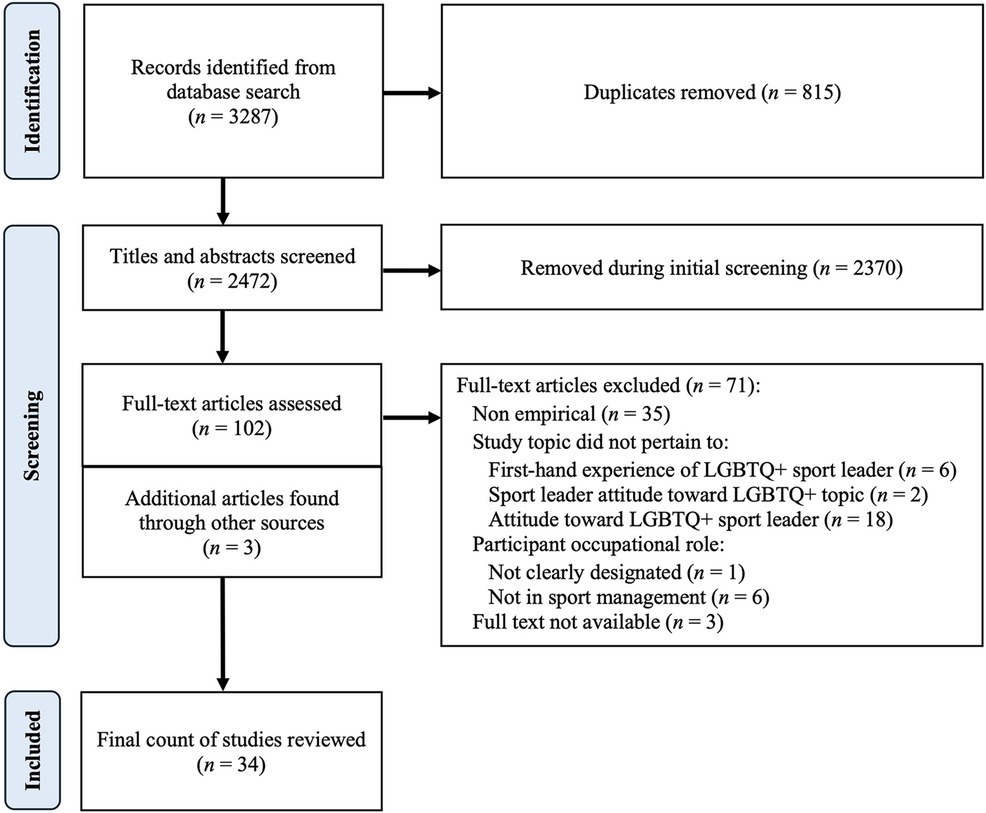

Articles were included based on the following criteria: (a) the study was an original empirical study; (b) the study topic pertained to (i) first-hand, lived experiences reported by LGBTQ+ individuals working in managerial roles in sport; or (ii) sport stakeholder attitudes toward LGBTQ+ individuals that occupy managerial roles in sport; or (iii) attitudes of individuals working in sport managerial roles toward LGBTQ+ issues within sport; (c) the managerial role in the sport organization was designated as athletic director, athletic administrator, sport manager, sport information director, support staff, or sport coach. To reduce the possibility of missing relevant studies, there was no date restriction for the search process; any record published within searched databases up to and including the date of original and updated search(es) was screened. References that were excluded during the screening process included: (a) media or journalistic reports, textbook chapters, and non-empirical studies; (b) studies in which (i) all participants were heterosexual or sexual orientation was not designated; or (ii) topics other than attitudes towards occupational role designee were explored; or (iii) LGBTQ+ physical or mental health behaviors or issues were researched; (c) studies in which participant roles were not clearly designated or roles were not in the sport industry. The selection process was conducted in four phases according to PRISMA guidelines and is displayed in Figure 1 (31).

2.2 Quality appraisal

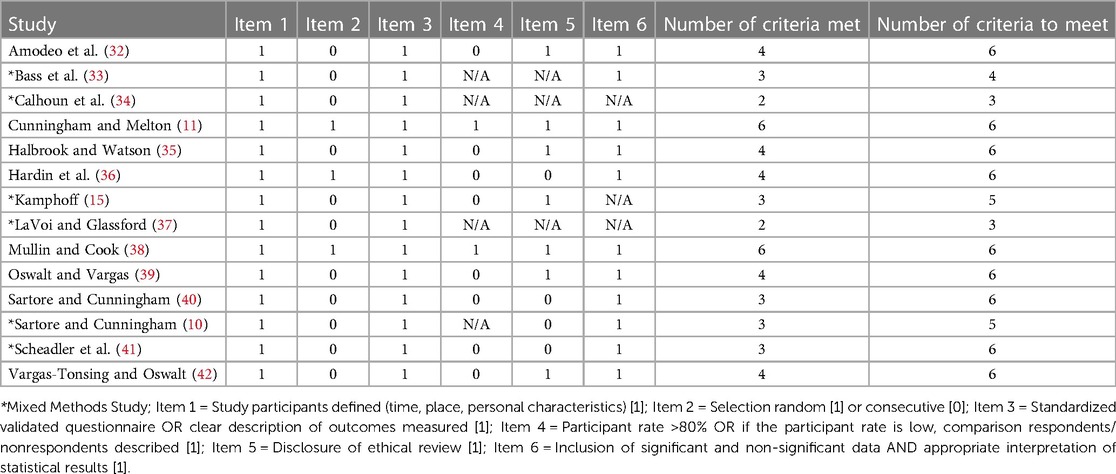

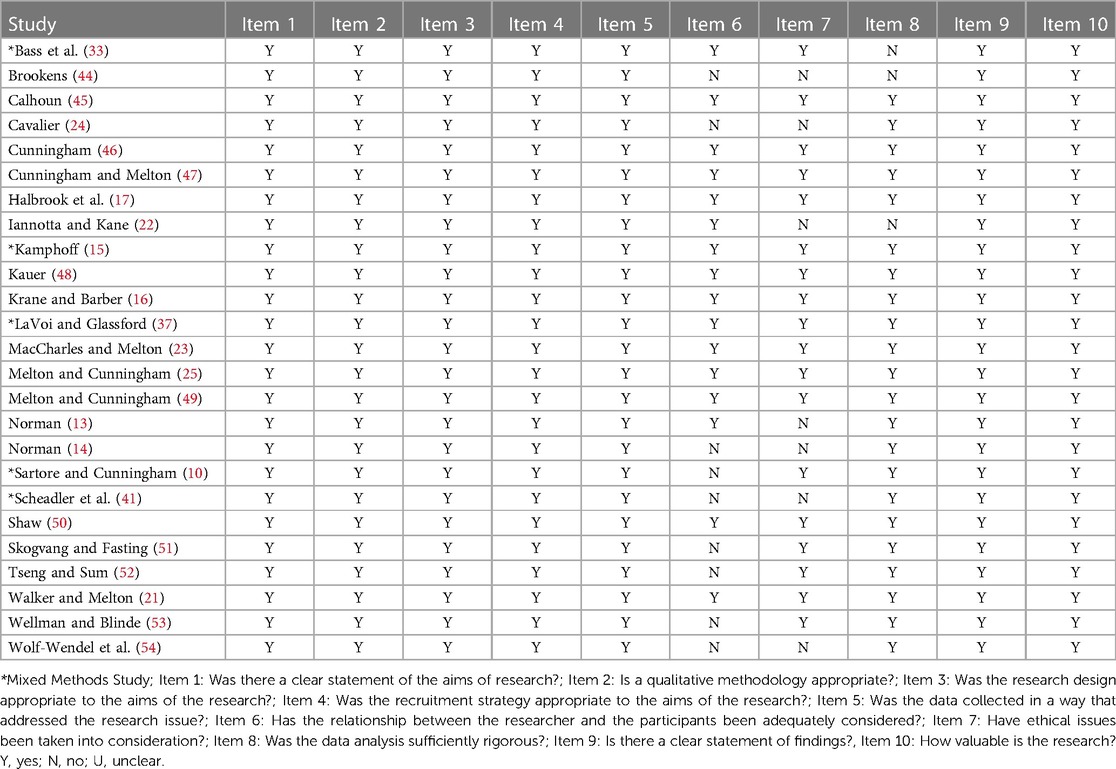

Included articles did not contain studies with randomized control trials; overall, the studies utilized a variety of methodologies to conduct empirical research. A quality assessment of bias was performed using two accepted standards of methodological appraisal. For quantitative studies, risk of bias assessments were informed by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) observational research criteria tool as shown in Table 1 (43); for qualitative studies, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) was utilized, as shown in Table 2 (55, 56). Mixed methods studies were evaluated through both standards of appraisal. Both authors independently completed quality assessments for all included articles. Then, authors jointly discussed any discrepancies regarding methodological rigor of included studies until reaching consensus regarding if and how each study met appraisal criteria. Following quality assessment, relevant information was extracted from selected articles. Extracted information, displayed in Table 3, included country of study, methodological design, theoretical framework, subject focus, sample (participant characteristics), and results.

3 Results

The initial literature search, conducted by the primary author, resulted in 3,287 articles. After removing duplicate articles by hand, the primary author screened 2,472 articles based on title and abstract relevance, deleting 2,370 articles within the second phase. A total of 102 full-text articles were then assessed according to the three inclusion/exclusion criteria. As discussed previously, both authors independently evaluated all articles and ultimately reached consensus regarding articles included in the final analysis. Thus, 71 articles were removed and 3 additional articles were added, yielding 34 articles to be included in the final analysis (Figure 1).

3.1 Profile of selected articles

Empirical studies were published within a 24-year range from 1997 to 2021, with most articles (n = 26) being published after 2010. Reviewed studies were predominantly composed of samples from the US (n = 28), with additional studies containing samples from the United Kingdom (n = 2), China/Taiwan/Hong Kong (n = 1), New Zealand (n = 1), Norway (n = 1), and Italy (n = 1). Additionally, ten authors accounted for multiple articles (n = 18).

3.2 Study design, data analysis, and quality appraisal

Selected studies possessed a variety of methodological designs, including mixed methods (n = 7), quantitative (n = 8), and qualitative (n = 19). Mixed method designs most frequently used survey research (n = 4) for quantitative analysis, while interviews (n = 3) and content analysis (n = 3) were most used in qualitative analyses. All quantitative studies used survey research (n = 8); qualitative studies used interviews (n = 16) and case studies (n = 3).

Two quantitative studies met all appraisal criteria (11, 38), while two quantitative studies met all but one aspect of appraisal criteria (Table 1). Remaining quantitative studies (n = 10) met most of the appraisal criteria with scores of 3/6, 3/5, or 4/6. Because of the stigmatized subject of articles, random selection of participants (Item #2; Table 1) was not frequently used by researchers and participant rates were generally low. However, these articles (n = 10) were deemed to be of high enough quality for inclusion, as all studies defined participants, described significant and non-significant results appropriately, and used a validated questionnaire or clearly described measured outcomes.

Twelve qualitative studies met all appraisal criteria, as displayed in Table 2. Remaining studies (n = 13) met most appraisal criteria, including statement of aims, appropriate methodology and research design, defined recruitment strategy, relevant data collection, rigorous data analysis, and statement of findings. However, 36% of qualitative studies (n = 9) did not delineate the researcher-participant relationship and 28% of studies (n = 7) did not address whether ethical considerations within the study design or analytic process were described to participants. Regardless, most of the other appraisal criteria were met and therefore the studies were deemed strong enough for inclusion in the present review.

3.3 Theoretical framework

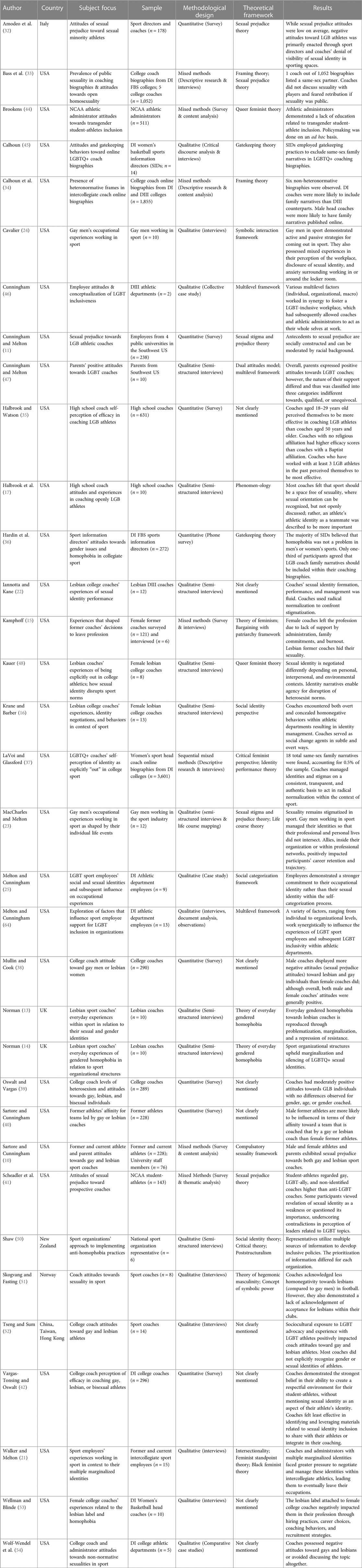

There was no universal theoretical framework used by researchers (Table 3). In total, 24 different theoretical frameworks were used within the examined articles to ground methodology and subsequent data analysis, with the most frequently used frameworks being Sexual Stigma and Prejudice Theory [n = 5; e.g., (19, 49)] and Multilevel Framework [n = 3; e.g., (46, 57)]. Five studies were grounded in theories related to feminism: specifically, Queer Feminist Theory [n = 2; e.g., (58, 59)] Black Feminist Theory [n = 1; e.g., (60, 61)] Feminist Standpoint Theory [n = 1; e.g., (62)] and the Theory of Feminism [n = 1; e.g., (63)]. Nine studies did not clearly define the theoretical framework utilized for analysis. Eight studies within the sample leveraged multiple frameworks simultaneously to guide empirical research.

3.4 Subject focus, sample, and results

To develop a holistic perspective of sport leaders’ experiences with LGBTQ+ topics, the systematic review of articles was divided into three topic areas prior to the search process. Given the lack of research on LGBTQ+ sport manager experiences (1) and the influence of sport leader policies and practices on inclusion and LGBTQ+ athlete experiences (7, 18, 29), topic areas were pre-selected to best represent the experiences, behaviors, and attitudes of sport leaders in relation to LGBTQ+ topics. More specifically, these subjects included: (a) studies examining the first-hand lived experiences of sport leaders with LGBTQ+ sexual identities; (b) studies exploring stakeholder attitudes toward LGBTQ+ identifying sport leaders; and (c) studies concerning attitudes of those working within sport leadership positions towards LGBTQ+ sport issues. All included articles were analyzed for subject area and sample characteristics to reveal the research focus alongside key findings within the population of interest, as outlined in Table 3.

3.4.1 First-hand lived experiences of LGBTQ+ sport leaders

Twelve studies within the sample examined the first-hand lived experiences of LGBTQ + individuals occupying sport leadership positions. Lesbian females composed the entire sample (n = 8) or the majority of the sample (n = 2) in 83.3% of studies. Only two studies (23, 24) investigated the experiences of gay men working in sport. Sport coaches were the predominant focus within this subject area, as 58.3% of studies solely examined coach experiences (n = 7). Three studies (21, 23, 64) had mixed samples of sport coaches and other employees and two studies (24, 25) did not reveal specific occupational roles to maintain participant confidentiality. Additionally, 66.7% of studies (n = 8) had samples in which the majority of participants were White; only one study (21) possessed a sample with majority non-White participants, as Black intercollegiate sport employees comprised most of their sample. Three studies (16, 23, 37) did not provide demographic information to protect participant confidentiality.

Understanding and exploring sexual identity within the context of sport was a major aim of studies examining lived experiences of LGBTQ+ sport leaders. Participants’ experiences were highlighted by the intersectionality of power dynamics, occupational status (64), and social identity (21). Many LGBTQ+ sport leaders reported encountering sexual prejudice or homophobia within their sport organizations or via interactions with colleagues due to their marginalized sexual orientation (13, 15, 16).

In general, sexual identities were classified as complex and fluid in nature. Participants described their “level of outness,” in terms of public disclosure of their sexual orientation, to be dependent on contextual factors such as situational safety, personal comfort level, and an opportunity to foster interpersonal connection (16, 22). Further, LGBTQ+ sport employees and coaches engaged in a variety of identity performance (22, 24) and identity management (25, 37) tactics in occupational settings. For some sport leaders, identity management involved covering [i.e., concealment of stigmatized identity by promoting hyperfeminine or hypermasculine dress or behavior (16, 23)]. Other LGBTQ+ sport leaders compartmentalized their personal lives from their professional lives to conceal their marginalized identity (48). An additional method of covering involved emphasizing athletic and/or occupational identities to be most important to their sense of self, especially when compared to their aspects of themselves within the workplace (24, 25). Together, these covering strategies effectively disguised participants’ marginalized sexual orientation from student-athletes, colleagues, and supervisors alike.

Continuous engagement in identity management practices had differential effects on LGBTQ+ sport leaders. Some lesbian coaches described their workplace as a homophobic environment and feared negative backlash due to their sexual identity (13, 15, 16). Other lesbian coaches felt that identity management provided them with agentic control over their personal narratives. Further, by choosing when and how to disclose their LGBTQ+ identity, some participants were able to engage in radical normalization (22, 37). Iannotta and Kane (22) reported that lesbian coaches strategically normalized their marginalized identity by integrating routine actions, such as casually mentioning their partners during interactions with their athletes and colleagues. Coaches also shared their LGBTQ+ family narratives in their online biographies to publicly normalize their sexual identities (37). These actions aimed to disrupt the heteronormative culture of sport (14), while also promoting inclusion within participants’ respective sport environments.

In the particular case of participants who identified as gay men, these individuals did not always perceive workplace environments in sport as overtly hostile (23, 24). However, their perceptions still influenced their identity management behaviors, in the sense that some perceived their occupational identity to be more central to their person, and therefore downplayed marginalized identities [e.g., sexual orientation (24)]. Consequently, in some cases, gay men who held low occupational status in their organizations (e.g., early career roles, shorter tenure within an organization) concealed their sexual identities by avoiding discussions of their personal lives or “passing” as heterosexual through hypermasculine appearances or behaviors (23).

Coaches and administrators with multiple marginalized identities faced greater pressures to negotiate aspects of their identity to remain working in sport. Walker and Melton (21) reported that lesbian intercollegiate sport employees not only felt they had to manage their marginalized sexual orientation but also their gender and racial identities within their respective athletic departments. Black lesbian employees described that working in collegiate sport was more challenging for them because they consistently needed to manage both their race and sexual orientation without any shared community for their identities (i.e., a Black lesbian community in sport). As such, the necessity to continuously engage in identity management created a tipping point, influencing many participants to leave their occupation (21).

Overall, studies examining the lived experiences of LGBTQ+ individuals in sport leadership positions revealed a predominant focus on lesbian women, especially in coaching roles, with limited representation and exploration of gay men or LGBTQ+ individuals with multiple marginalized identities (e.g., race). Many LGBTQ+ sport leaders reported experiences of encountering homophobia within their workplaces. Identity management strategies varied among participants, ranging from covering, compartmentalization, and radical normalization. Each strategy had a differential effect on participants depending on their personal context (64), and social identities were navigated differently depending on interpersonal, sociocultural, organizational, and environmental factors (21, 23, 48).

3.4.2 Studies exploring stakeholder attitudes toward LGBTQ+ sport leaders

There were limited studies (n = 5) in the sample that explored stakeholder attitudes toward LGBTQ+ sport leaders. In these articles, prominent stakeholders included parents (11, 47) and athletes (10, 40, 41). Participants in four studies were predominantly White, with only one study possessing a sample of diverse racial identities [i.e., African American, Hispanic, and White individuals (47)]. Stakeholders identified as predominantly heterosexual in three studies (10, 41, 47); remaining studies did not report the sexual orientation of participants.

Studies explored attitudes of sexual prejudice toward LGBTQ+ sport coaches, as well as affinity for teams led by gay or lesbian coaches. Findings related to parent attitudes were variable: Sartore and Cunningham (10) revealed that parents possessed prejudicial attitudes toward gay and lesbian sport coaches and would not allow their children to compete for them, while Cunningham and Melton (47) found that parents generally possessed positive attitudes toward LGBT coaches, but the level of support varied between unequivocal (e.g., unconditional), indifferent, and qualified (e.g., conditional). Notably, racial identity was classified as a moderating variable in the relationship between parent prejudice and LGB coaches (11).

Similar to parents, athletes also exhibited different attitudes toward LGBTQ+ coaches. Some had more positive views of gay or LGBT-ally prospective coaches (41); others exhibited attitudes of sexual prejudice towards gay or lesbian coaches and, in some cases, conveyed that they would not play for them (10). Gender of the athlete also influenced affinity for teams led by a gay or lesbian coach. Specifically, former male athletes were increasingly influenced to like a team when they were aware that the coach was gay or lesbian (40).

In summary, while two key sport stakeholder groups were studied (parent and athlete), findings regarding attitudes toward LGBTQ+ sport coaches were inconsistent, and at times, contradictory. There was limited information about the influence of demographic variables on stakeholder attitudes, and no research concerning attitudes towards LGBTQ+ individuals in sport leadership positions outside of coaches.

3.4.3 Studies related to sport leader attitudes toward LGBTQ+ sport topics

The majority of articles (n = 17) within the sample focused on sport leader attitudes toward LGBTQ+ topics in sport. Across the examined studies in this subject area, participants represented a range of occupational roles and perspectives toward LGBTQ+ topics in sport. Specific occupations included athletic administrators and sport directors (32, 44), high school coaches (17, 35), college coaches (38, 39, 42, 52, 53), sport information directors (36, 45), and athletic departments (46, 54). Studies in this subject area also examined a variety of topics, including attitudes towards LGB sexual identities (n = 5), attitudes towards LGB athletes (n = 5), inclusiveness (n = 3), public same sex family narratives (n = 2), and efficacy to coach LGB athletes (n = 2). Two primary themes identified across these topic areas were (a) attitudes toward LGBTQ+ student-athletes, and (b) the portrayal and discussion of LGBTQ+ sexual identity in sport, both of which are expanded upon in the following paragraphs.

Sport directors and coaches at both the high school and college levels were surveyed in studies concerning sport leader attitudes toward LGBTQ+ athletes. Antecedents to coach attitudes included education surrounding topics of sexual or gender identities, previous contact with LGBTQ+ athletes, societal influences, age, and religious beliefs (35, 52). Some research suggested that coaches possessed a more tolerant or increasingly positive view toward LGB athletes in Italy (32), China, Taiwan, Hong Kong (52), and the United States (38, 39), which could result in fewer instances of openly prejudicial behaviors based on athlete sexual identity (32, 52). Other studies identified heterosexist norms to be prevalent amongst coaches (51) and other sport leaders, including sport information directors (45); these studies indicated that structural ideologies (i.e., gender ideology, heterosexist ideology) continue to influence individual attitudes and thoughts toward LGBTQ+ topics (17, 39).

The influence of heterosexist ideology extended beyond mere attitudes and thoughts to impact sport leader behaviors. This was specifically observed in the context of LGBTQ+ identities. Particularly, coaches at both the high school (17) and college (33, 54) levels did not openly discuss LGBTQ+ topics with their athletes. Instead, coaches failed to acknowledge the sexual orientation of LGBTQ+ athletes (32) or chose to prioritize the acknowledgment of their athletic identities over other identities such as sexual orientation (52). Further, organizational sport managers (50), intercollegiate athletic administrators (44), and coaches (42) felt like they lacked knowledge and/or experience navigating LGBTQ+ sport issues or access to appropriate resources to do so. The lack of acknowledgement and education surrounding the presence of LGBTQ+ sexual orientations demonstrated a form of covert silencing that perpetuated heterosexism (17, 32).

Silencing of LGBTQ+ sexual orientations by sport leaders also extended to overt forms across included studies. For example, by mere association with LGBTQ+ identities (e.g., being labeled or perceived as a “lesbian”), both heterosexual and queer female coaches engaged in specific occupational behaviors (i.e., staff hiring practices, student-athlete recruitment strategies) to ensure that they avoided the “lesbian” label while navigating their career paths (53). Understanding the potential repercussions such a label could pose to their career progression in a new institution, coaches also reported altering their career choices (i.e., accepting new positions) to avoid these perceived or actual labels (53). Additionally, sport information directors in collegiate athletic departments engaged in gatekeeping practices by excluding same sex family narratives in public online coaching biographies (33, 34) while reporting their belief that they did not view homophobia as an issue in intercollegiate athletics (36).

While some participants within the included studies displayed increasing tolerance toward LGBTQ+ athletes, the research within this subject area indicates that heterosexism and heteronormativity continue to exist at a structural level across sport organizations. Heterosexist ideology influenced sport leader attitudes, thoughts, and behaviors. It resulted in the covert silencing of LGBTQ+ identities and continued presence of organizational barriers (such as exclusionary gatekeeping), all of which underscore the complexities of LGBTQ+ inclusion within sport.

4 Discussion

The sexual orientation of sport leaders influences not only the ways in which they experience their lives but also how they experience their occupational role and environment (9, 15, 25). This systematic review found that sport leaders, including coaches and athletic administrators, continue to face marginalization because of heteronormativity and homophobia (10, 20, 22). This marginalization was present in everyday interactions (13) and was upheld by leaders and organizational practices (14, 21, 64). These findings align with extant scholarship in relation to LGBTQ+ discrimination in sport (3, 7).

The predominant theme across included studies underscored a heterosexist notion: sport is a place where sexual orientation should not be present nor discussed (17, 18, 32, 45). Exacerbated by a lack of knowledge surrounding inclusive LGBTQ+ practices, policies, and resources (17, 39, 42, 44), coaches and administrators perpetuate this notion in their organizational cultures. These practices do not only impact athletes, but also LGBTQ+ identifying sport leaders and sport leader attitudes towards LGBTQ+ issues. In essence, the research findings underscore the need to further explore and measure allyship behaviors in sport leadership positions (30), and the occupational behaviors of LGBTQ+ sport leaders.

The review of the included studies indicates that many sport organizations operate inclusively out of compliance. Additionally, previous literature denotes that leaders can react ad hoc to avoid legal repercussions (27), rather than proactively fostering LGBTQ+ inclusion through practices and policies (18). Management by this philosophy can result in the differential treatment of LGBTQ+ individuals in sport settings, whether by policies (e.g., specific team or departmental rules) or institutionalized practices [e.g., “Don't Ask, Don't Tell” behaviors (28)]. When sport leaders do attempt to proactively address LGBTQ+ inclusion (42), they must balance competing interests within and beyond their organizations. This creates additional barriers to fostering inclusion, especially if leaders are fearful of losing the support from external stakeholders [e.g., athletic donors, boosters, and sponsors (18)].

Some research suggests that sport is becoming more LGBTQ+ inclusive. LaVoi et al. (37) noted an increase in the visibility of openly lesbian coaches in public online biographies, and Scheadler et al. (41) revealed increasingly positive athlete attitudes towards LGBT+ or LGBT-ally coaches. However, LaVoi et al. (37) reported only 0.5% of examined online biographies contained a same-sex family narrative. Further, Scheadler et al. (41) described that some athletes viewed sexuality as a weakness, and others expressed respect for an anti-LGBT coach's views.

However, multiple studies in this systematic review present interpretive paradoxes for LGBTQ+ identities and topics in sporting contexts. Particularly, sport employees value LGBTQ+ inclusion in the workplace (46), yet sport leaders fail to portray same sex family narratives or believe that LGBTQ+ identities should not be displayed publicly (36, 45); LGBTQ+ sport leaders recognize the importance of their sexual identity (37), yet they engage in a variety of identity management techniques to conceal it (16, 23); sport leaders report more positive attitudes toward LGBTQ+ individuals (38, 52), yet they reproduce heterosexism in policy and practice (21, 39); sport environments are viewed as less hostile for LGBTQ+ identifying individuals because of a decrease in overt homonegativity (24), yet more subtle forms of discrimination, like ignoring or the silencing of LGBTQ+ identities, equally communicates exclusion (14, 32).

The results of these studies convey that while inclusion may be championed on an interpersonal level (64), it faces sociocultural and structural barriers at large due to the heteronormative and heterosexist nature of sport (14, 47). Inclusion can serve as an umbrella term that sport leaders use to promote ideological progression, but in reality, it is not practiced. Instead, sport leaders fail to regularly acknowledge LGBTQ+ sexual orientations in athletic contexts for athletes, coaches, and other stakeholders. By avoiding this, they fail to bridge the connection between identity and behavioral practice in sport leadership.

4.1 Strength and weaknesses

The studies in this review possess several strengths. The first is the use of multiple theoretical frameworks to guide methodology and data analysis in qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method studies. The lack of a universally accepted framework within this subject area emphasizes the need to understand LGBTQ+ experiences in sport from multiple perspectives. Additionally, it provides both practitioners and scholars with a complex, nuanced understanding of LGBTQ+ experiences and topics from a sport leadership perspective.

The second is the use of qualitative methodologies throughout strictly qualitative research and in mixed method studies. Qualitative research can spotlight the voices and experiences of marginalized individuals. It also provides participants the opportunity to not only describe the what (e.g., behaviors, attitudes, experiences, beliefs) but also the how or why (e.g., explaining attitudes, events, experiences) in greater detail to reveal contradictory perceptions towards and the complexity of lived experiences for LGBTQ+ sport leaders.

The third is the examination of sport leaders’ attitudes toward LGBTQ+ topics from a variety of occupational positions, including high school coaches, college coaches, athletic directors, sport administrators, and sport information directors, among others. Including participants from multiple sport leadership positions allowed for a comprehensive understanding of their attitudes and beliefs toward LGBTQ+ inclusion.

It is also important to note limitations of included studies. First, only one study (44) in this review examined sport leader attitudes towards transgender inclusion. Policies and provisions surrounding transgender athlete participation create repercussions for all transgender, nonbinary, gender non-conforming and/or intersex individuals operating in sport, including sport leaders. As such, future research must address the experiences of all athletes and sport leaders encompassed by the LGBTQ+ acronym.

Second, the majority of studies that reported racial demographic information (n = 12) had a participant sample that was predominantly White. While this is reflective of current demographic data for sport leaders (i.e., coaches, athletic directors, athletic administrators) across NCAA divisions (65), it fails to include the perspectives of Black, Asian, Hispanic, Latino, Multiracial, and additional marginalized racial identities who also identify as LGBTQ+. Only one study examined the experiences of current and former sport employees with multiple marginalized identities (21).

Third, consistent with previous literature (2), identity was the most prevalent topic explored when considering the firsthand experiences of LGBTQ+ sport leaders. Further, in this investigation of lived experiences, examined studies contained homogeneous samples in terms of gender and occupational role. Many studies (n = 11) had samples composed of predominantly female participants; additionally, most studies (n = 16) explored the experiences or attitudes of sport coaches. Only two articles (23, 24) explored the lived experiences of gay men. Outside of two studies with mixed coach-administrator samples (21, 64) or athletic department case studies (25, 46, 54), no studies examined the experiences of athletic administrators, who serve as major sport leaders in intercollegiate athletic departments in the U.S. Because participant samples were similar in terms of occupation and gender, it was not possible to draw comprehensive conclusions about the diverse experiences of LGBTQ+ sport leaders.

Fourth, the most frequently researched LGBTQ+ topic in sport leadership was sport leader attitudes toward LGBTQ+ topics (n = 17). However, a closer examination of topic areas revealed that only one study explored administrative decision-making related to organizational policies and practices (44). This gap in the literature is interesting, considering that administrative functions involving planning, implementation, and evaluation of policies and practices are key occupational responsibilities for athletic administrators, especially at the collegiate level.

4.2 Future directions

This systematic review critically explored findings related to lived experiences of LGBTQ+ sport leaders, attitudes toward LGBTQ+ sport leaders, and attitudes of sport leaders toward LGBTQ+ topics. A comprehensive picture of the extant scholarship shows that sport leadership positions at large are still understudied, especially in the context of LGBTQ+ identities and topics.

Future studies can extend previous research by: (a) continuing to explore the experiences of LGBTQ+ athletic administrators, with particular emphasis on demographics that are historically (and remain) underrepresented in sport scholarship, including the experiences of bisexual people and gay men, transgender and/or gender-nonconforming individuals, as well as Black, Asian, Hispanic, Latino, Multiracial, and individuals with other marginalized racial identities; (b) continuing to examine the intersectional experiences of LGBTQ+ sport leaders (e.g., race, gender, sexual orientation); (c) interrogating the privilege and influence of occupational status and power in conjunction with marginalized sexualities in sport leadership positions; (d) investigating the leadership behaviors of LGBTQ+ athletic administrators in relation to decision-making; (e) surveying the attitudes of athletic administrators toward LGBTQ+ coaches and/or topics [see (30)]; (f) investigating the attitudes of sport leaders toward transgender sport policies and inclusion at all organizational and competitive levels; and (g) examining (with the intent to reform) the effectiveness of current educational trainings/programming surrounding LGBTQ+ identities and topics.

It is important to acknowledge the existence of significant sociopolitical barriers that can impact scholarship. One such example is in the United States. As of 2024, 85 legislative bills that prohibit DEI initiatives and training in admissions, employment, and/or education regarding race, ethnicity, national origin, sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, and religion have been introduced to U.S. Congress. In 13 states (Idaho, Wyoming, North Dakota, Utah, Texas, Kansas, Indiana, Tennessee, Alabama, North Carolina, and Florida), these bills have been signed into law (66). Further, each of these proposed or passed bills invoke nuanced impacts due to various prohibitions. Anti-DEI legislation could have a chilling effect on scholarship in this area due to reduced institutional support, decreased research funding, and the existence of potential occupational and physical dangers to the safety of researchers and participants. At the time of this manuscript submission, the consequences of these legislative bills on DEI-related scholarship in sport have not been studied.

Beyond legislation, sociocultural barriers in sport remain—resulting in the stigmatization of and discrimination against LGBTQ+ individuals working and participating in sport (7). These barriers impact the lived experiences of LGBTQ+ sport leaders and pose significant challenges for researchers attempting to study this population. If LGBTQ+ individuals cannot safely disclose their identities in the workplace, it is difficult for researchers to identify and recruit participants to conduct studies.

To advance this research, exploring future avenues of scholarship is needed, especially in light of the aforementioned barriers. To best promote the visibility of LGBTQ+ research, it is crucial to collaborate with scholars and practitioners to highlight the importance of LGBTQ+ allyship/advocacy in sport settings and to promote policies that protect DEI initiatives in sport and other social institutions.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

CO: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AB: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

This study was supported by Millersville University, USA, through a Publication Grant (ID#6012205022-609272).

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the support of Springfield College, USA, where this research project started. The authors also thank Millersville University of Pennsylvania, USA, for the continued support of this project.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnote

1. ^The term “LGBTQ+” was used throughout this manuscript to mirror language in reviewed studies. The authors reference specific labels within the acronym “LGBTQ+” that were also explicitly represented in included studies. To the authors’ best knowledge, intersex and asexual identities were not represented in this sample.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Shaw S, Cunningham GB. The rainbow connection: a scoping review and introduction of a scholarly exchange on LGBTQ+ experiences in sport management. Sport Manag Rev. (2021) 24(3):365–88. doi: 10.1080/14413523.2021.1880746

2. Brackenridge C, Alldred P, Jarvis A, Maddocks K, Rivers I. A Review of Sexual Orientation in Sport: Sportscotland Research Report no. 114. Edinburgh: sportscotland (2008).

3. Kavoura A, Kokkonen M. What do we know about the sporting experiences of gender and sexual minority athletes and coaches? A scoping review. Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol. (2020) 14(1):1–27. doi: 10.1080/1750984X.2020.1723123

4. Newhall KE, Walker NA. Sport administration. In: Krane V, editor. Sex, Gender, and Sexuality in Sport: Queer Inquiries. Abingdon, OX: Routledge (2019). p. 123–42.

5. Anderson E, Magrath R, Bullingham R. Out in Sport: The Experiences of Openly gay and Lesbian Athletes in Competitive Sport. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, UK: Routledge (2016).

6. Cahn SK. Coming on Strong: Gender and Sexuality in Women’s Sports. 2nd ed Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press (2015).

7. Denison E, Bevan N, Jeanes R. Reviewing evidence of LGBTQ+ discrimination and exclusion in sport. Sport Manag Rev. (2021) 24(3):389–409. doi: 10.1016/j.smr.2020.09.003

8. Krane V. Introduction: LGBTIQ people in sport. In: Krane V, editor. Sex, Gender, and Sexuality in Sport: Queer Inquiries. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, UK: Routledge (2019). p. 1–12.

9. Cunningham GB. Diversity & Inclusion in Sport Organizations. 3rd ed New York, NY: Routledge (2019).

10. Sartore M, Cunningham G. Gender, sexual prejudice and sport participation: implications for sexual minorities. Sex Roles. (2009) 60:100–13. doi: 10.1007/s11199-008-9502-7

11. Cunningham GB, Melton N. Prejudice against lesbian, gay, and bisexual coaches: the influence of race, religious fundamentalism, modern sexism, and contact with sexual minorities. Sociol Sport J. (2012) 29(3):283–305. doi: 10.1123/ssj.29.3.283

12. Griffin P. Changing the game: homophobia, sexism, and lesbians in sport. Quest. (1992) 44(22):251–65. doi: 10.1080/00336297.1992.10484053

13. Norman L. Gendered homophobia in sport and coaching: understanding the everyday experiences of lesbian coaches. Intl Rev Sociol Sport. (2012) 47(6):705–23. doi: 10.1177/1012690211420487

14. Norman L. The concepts underpinning everyday gendered homophobia based upon the experiences of lesbian coaches. Sport Soci. (2013) 16(10):1326–45. doi: 10.1080/17430437.2013.821255

15. Kamphoff CS. Bargaining with patriarchy: former female coaches’ experiences and their decision to leave collegiate coaching. Res Q Exerc Sport. (2010) 81(3):360–72. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2010.10599684

16. Krane V, Barber H. Identity tensions in lesbian intercollegiate coaches. Res Q Exerc Sport. (2005) 76(1):67–81. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2005.10599263

17. Halbrook MK, Watson JC II, Voelker DK. High school coaches’ experiences with openly lesbian, gay, and bisexual athletes. J Homosex. (2019) 66(6):838–56. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2017.1423222

18. Turk MR, Stokowski SE, Dittmore SW. “Don’t be open or tell anyone”: inclusion of sexual minority college athletes. J Issues Intercollegiate Athletics. (2019) 12:564–89. https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/jiia/vol12/iss1/1

19. Herek GM. Confronting sexual stigma and prejudice: theory and practice. J Soc Issues. (2007) 63(4):905–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2007.00544.x

20. Griffin P. Strong Women, Deep Closets: Lesbians and Homophobia in Sport. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics (1998).

21. Walker NA, Melton EN. The tipping point: the intersection of race, gender, and sexual orientation in intercollegiate sports. J Sport Manag. (2015) 29(3):257–71. doi: 10.1123/jsm.2013-0079

22. Iannotta JG, Kane MJ. Sexual stories as resistance narratives in women’s sports: reconceptualizing identity performance. Sociol Sport J. (2002) 19(4):347–69. doi: 10.1123/ssj.19.4.347

23. MacCharles JD, Melton EN. Charting their own path: using life course theory to explore the careers of gay men working in sport. J Sport Manag. (2021) 35:407–25. doi: 10.1123/jsm.2019-0415

24. Cavalier ES. Men at sport: gay men’s experiences in the sport workplace. J Homosex. (2011) 58(5):626–46. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2011.563662

25. Melton EN, Cunningham GB. Examining the workplace experiences of sport employees who are LGBT: a social categorization theory perspective. J Sport Manag. (2014) 28(1):21–33. doi: 10.1123/jsm.2011-0157

26. Covell D, Barr CA. Managing Intercollegiate Athletics. Scottsdale, AZ: Holcomb Hathaway Publishers (2010).

27. Fink JS, Pastore DL, Riemer HA. Do differences make a difference? Managing diversity in division IA intercollegiate athletics. J Sport Manag. (2001) 15:10–50. doi: 10.1123/jsm.15.1.10

28. Anderson AR, Stokowski S, Turk MR. Sexual minorities in intercollegiate athletics: religion, team culture and acceptance. Sport Soc. (2022) 25(11):2303–22. doi: 10.1080/1743047.2021.1933452

29. Toomey RB, McGeorge CR. Profiles of LGBTQ ally engagement in college athletics. J LGBT Youth. (2018) 15(3):162–78. doi: 10.1080/19361653.2018.1453428

30. McGeorge CR, Toomey RB, Zhao Z. Measuring allyship: development and validation of two measures to assess collegiate athlete department staff engagement in LGBTQ allyship and ally behaviors. J Homosex. (2024) 71(8):1900–17. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2023.2217315

31. Moher D, Liberati A, Tatzlaff K, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. (2009) 6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

32. Amodeo AL, Antuoni S, Claysset M, Esposito C. Traditional male role norms and sexual prejudice in sport organizations: a focus on Italian sport directors and coaches. Soc Sci. (2020) 9(12):218. doi: 10.3390/socsci9120218

33. Bass J, Hardin R, Taylor EA. The glass closet. J Appl Sport Manag. (2015) 7(4):1–36. doi: 10.18666/JASM-2015-V7-I4-5298

34. Calhoun AS, LaVoi NM, Johnson A. Framing with family: examining online coaches’ biographies for heteronormative and heterosexist narratives. Int J Sport Commun. (2011) 4(3):300–16. doi: 10.1123/ijsc.4.3.300

35. Halbrook M, Watson JC. High school coaches’ perceptions of their efficacy to work with lesbian, gay, and bisexual athletes. Int J Sport Sci. (2018) 13(6):841–8. doi: 10.1177/1747954118787494

36. Hardin M, Whiteside E, Ash E. Ambivalence on the front lines? Attitudes toward title IX and women’s sports among division I sports information directors. Int Rev Sociol Sport. (2014) 49(1):42–64. doi: 10.1177/1012690212450646

37. LaVoi NM, Glassford SL. “This is our family”: LGBTQ family narratives in online NCAA D-I coaching biographies. J Homosex. (2021) 69:1–24. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2021.1921506

38. Mullin EM, Cook S. Collegiate coach attitudes towards lesbians and gay men. Int J Sports Sci Coach. (2021) 16(3):519–27. doi: 10.1177/1747954120977130

39. Oswalt SB, Vargas TM. How safe is the playing field? Collegiate coaches’ attitudes towards gay, lesbian, and bisexual individuals. Sport Soci. (2013) 16(1):120–32. doi: 10.1080/17430437.2012.690407

40. Sartore ML, Cunningham GB. Gay and lesbian coaches’ teams: differences in liking by male and female former sport participants. Psychol Rep. (2007) 101(1):270–2. doi: 10.2466/pr0.101.1.270-272

41. Scheadler TR, Bertrand NA, Snowden A, Cormier ML. Student-athlete attitudes toward gay, ally, and anti-LGBT+ prospective coaches. J Issues Intercollegiate Athletics. (2021) 14:135–51. https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/jiia/vol14/iss1/26

42. Vargas-Tonsing TM, Oswalt SB. Coaches’ efficacy beliefs towards working with gay, lesbian, and bisexual athletes. Int J Coaching Sci. (2009) 3(2):29–42. doi: 10.1177/1747954118787494

43. Harris RP, Helfand M, Woolf SH, Lohr KN, Mulrow CD, Teutsch SM, et al. Current methods of the U.S. Preventative task force: a review of the process. Am J Prev Med. (2001) 20(3 Suppl):21–35. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00261-6

44. Brookens L. Athletic administrator perspectives hindering transgender inclusion in U. S. collegiate sports: a queer-feminist analysis. ICSSPE Bull. (2011) 62:12–12.

45. Calhoun AS. Sports Information Directors and the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell Narrative: Applying Gatekeeping Theory to the Creation and Contents of Division I Women’s Basketball Online Coaching Biographies (Doctoral dissertation). University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN (2015).

46. Cunningham GB. Creating and sustaining workplace cultures supportive of LGBT employees in college athletics. J Sport Manag. (2015) 29(4):426–42. doi: 10.1123/jsm.2014-0135

47. Cunningham G, Melton EN. Varying degrees of support: understanding parents’ positive attitudes toward LGBT coaches. J Sport Manag. (2014) 28(4):387–98. doi: 10.1123/jsm.2013-0004

48. Kauer KJ. Queering lesbian sexualities in collegiate sporting spaces. J Lesbian Stud. (2009) 13(3):306–18. doi: 10.1080/10894160902876804

49. Herek GM. Sexual stigma and sexual prejudice in the United States: a conceptual framework. In: Hope DA, editor. Contemporary Perspectives on Lesbian, gay, and Bisexual Identities. Lincoln, NE: Springer (2009). p. 65–111.

50. Shaw S. The chaos of inclusion? Examining anti-homophobia policy development in New Zealand sport. Sport Manag Rev. (2019) 22(2):247–62. doi: 10.1016/j.smr.2018.04.001

51. Skogvang BO, Fasting K. Football and sexualities in Norway. Soccer Soc. (2013) 14(6):872–86. doi: 10.1080/14660970.2013.843924

52. Tseng Y, Sum RKW. The attitudes of collegiate coaches toward gay and lesbian athletes in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and China. Int Rev Sociol Sport. (2021) 56(3):416–35. doi: 10.1177/1012690220943140

53. Wellman S, Blinde E. Homophobia in women’s intercollegiate basketball: views of women coaches regarding coaching careers and recruitment of athletes. Women Sport Phys Act J. (1997) 6(2):63–82. doi: 10.1123/wspaj.6.2.63

54. Wolf-Wendel LE, Douglas TJ, Morphew CC. How much difference is too much difference? Perceptions of gay men and lesbians in intercollegiate athletics. J Coll Stud Dev. (2001) 42(5):465–79.

55. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). CASP Systematic Review Checklist (2018). Available online at: https://casp-uk.net/checklists/casp-systematic-review-checklist-fillable.pdf (accessed March 22, 2024)

56. Hannes K. Critical appraisal of qualitative research. In: Noyes J, Booth A, Hannes K, Harden A, Harris J, Lewin S, Lockwood C, editors. Supplementary Guidance for Inclusion of Qualitative Research in Cochrane Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 1. (2011). p. 1–14. Available online at: http://cqrmg.cochrane.org/supplemental-handbook-guidance

57. Ferdman BM. The practice of inclusion in diverse organizations: toward a systemic and inclusive framework. In: Ferdman BM, Deane BR, editors. Diversity at Work: The Practice of Inclusion. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass (2014). p. 3–54.

58. Sykes H. Turning the closets inside/out: towards a queer feminist theory in women’s physical education. Sociol Sport J. (1998) 15:154–73. doi: 10.1123/ssj.15.2.154

59. Travers A. The sport nexus and gender injustice. Stud Soc Justice. (2008) 2(1):79–101. doi: 10.26522/ssj.v2i1.969

60. Borland JF, Bruening JE. Navigating barriers: a qualitative examination of the underrepresentation of black females as head coaches in collegiate basketball. Sport Manag Rev. (2010) 13(4):407–20. doi: 10.1016/j.smr.2010.05.002

61. Krane V. One lesbian feminist epistemology: integrating feminist standpoint, queer theory, and feminist cultural studies. Sport Psychol. (2001) 15:401–11. doi: 10.1123/tsp.15.4.401

62. Hallstein DO. A postmodern caring: feminist standpoint theories, revised caring, and communication ethics. West J Comm. (1999) 63:32–56. doi: 10.1080/10570319909374627

63. Hall MA. Feminism and Sporting Bodies: Essays on Theory and Practice. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics (1996).

64. Melton EN, Cunningham GB. Who are the champions? Using a multilevel model to examine perceptions of employee support for LGBT inclusion in sport organizations. J Sport Manag. (2014) 28(2):189–206. doi: 10.1123/jsm.2012-0086

65. National Collegiate Athletic Association. NCAA Demographics Database (2023). Available online at: https://www.ncaa.org/sports/2018/12/13/ncaa-demographics-database.aspx (accessed March 22, 2024)

66. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Here are States where Lawmakers are Seeking to Ban Colleges’ DEI Efforts (2024). Available online at: https://www.chronicle.com/article/here-are-the-states-where-lawmakers-are-seeking-to-ban-colleges-dei-efforts (accessed May 15, 2024)

Keywords: LGBTQ, coach, leader, administrator, sport, sexuality, leadership

Citation: O’Connell CS and Bottino A (2024) A systematic review of LGBTQ+ identities and topics in sport leadership. Front. Sports Act. Living 6:1414404. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2024.1414404

Received: 8 April 2024; Accepted: 12 June 2024;

Published: 1 July 2024.

Edited by:

Julie McCleery, University of Washington, United StatesReviewed by:

Elizabeth Gregg, University of North Florida, United StatesSarah Stokowski, Clemson University, United States

© 2024 O'Connell and Bottino. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Colleen S. O’Connell, Y29sbGVlbi5vY29ubmVsbEBtaWxsZXJzdmlsbGUuZWR1

Colleen S. O’Connell

Colleen S. O’Connell Anna Bottino2

Anna Bottino2