- Department of Mathematical Sciences, Kent State University, Kent, OH, United States

In this work, we study the equilibrium configurations in a nematic pi-cell under an electric field using the one-dimensional Oseen-Frank director model. The equilibrium orientational configurations that can be attained in a pi-cell are known as splay, bend, and twist. Among those, bend and twist are topologically equivalent and can be transitioned into one another as voltage varies. The transition can be continuous or abrupt depending on the material parameters. On the other hand, the splay configuration becomes asymmetric for sufficiently high voltages if the liquid crystal has a positive dielectric anisotropy. We determine those threshold voltages and characterize the order of transitions in terms of the elastic constants and the pretilt angle at the boundary.

1 Introduction

A multistable-state device has two or more locally stable states which are separated by energy barriers. The transitions among the states can be realized by applying an external field large enough to overcome the energy barrier to reach another state. After the field is removed, the device will remain in its locally stable state without a constant supply of power. Some known bistable devices include cholesteric liquid crystal (LC) display (Yang et al., 1994), bistable twist nematic (BTN) (Berreman and Heffner, 1980), surface controlled bistable nematic (Berreman and Heffner, 1981; Dozov and Durand, 1998; Kim et al., 2001), and Zenithally bistable nematic device (Bryan-Brown et al., 1994), just to name a few.

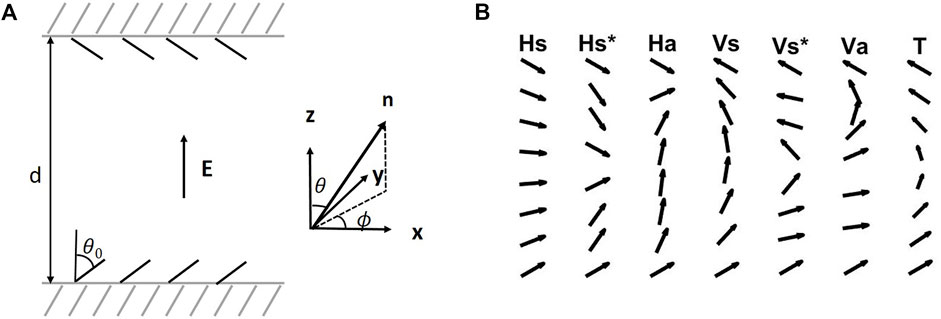

In 1980, Boyd, Cheng, and Ngo (Boyd et al., 1980) proposed a nematic LC display, later referred to as the pi-cell: nematic liquid crystals are enclosed between two parallel substrates; the boundaries are conditioned to induce the same pretilt alignment, characterized by the polar angle θ0 of the directors at the plate surfaces; and the top plate is rotated by angle π relative to the bottom plate, see Figure 1A. Three locally stable configurations, known as horizontal (H) for predominately splay, vertical (V) for predominately bend, and twist (T) states, can be achieved by specifying appropriate boundary conditions and proper material parameters. Switching among the topologically distinct states (V/T and H) can be realized via formation and movement of disclinations near the bounding surfaces after the application of electric and magnetic fields.

FIGURE 1. (A) A schematic of the nematic pi-cell with boundary pretilt conditions θ0, showing the coordinate system and definitions of angles θ and ϕ for the director n. (B) A schematic showing seven possible equilibrium orientation patterns of a nematic pi-cell under a vertical electric field. They are referred to as monotonic symmetric splay (Hs), nonmonotonic symmetric splay (Hs*), asymmetric splay (Ha), monotonic symmetric bend (Vs), nonmonotonic symmetric bend (Vs*), asymmetric bend (Va), and twist (T). The director field is assumed to be uniform in a plane parallel to the bounding plates.

In 1984 (Bos and Koehler/Beran, 1984), demonstrated that the pi-cell can be used for fast optical-switching devices in the V-state, also known as optically compensated bend (OCB) mode. Since then, many liquid crystal display devices with fast response time, large viewing angles, and high transmittance have been proposed based on the pi-cell (Yu and Kwok, 2004; Jhun et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2017).

There are seven possible equilibrium orientational patterns of a nematic pi-cell under an electric field applied normal to the cell, as shown in Figure 1; three are predominately splay configurations, which we label as Hs, Hs*, and Ha, three are predominately bend configurations, which we label as Vs, Vs*, and Va, and one is the out-of-plane twist configuration, which we label as T. Here Hs stands for monotonic symmetric splay where the tilt angle θ(z) monotonically increases from the bottom plate to the midplane, Hs* is for nonmonotonic symmetric splay where the tilt angle θ(z) first decreases and then increases from bottom plate to the midplane, and Ha represents the asymmetric splay. Similarly, Vs is for monotonic symmetric bend where the tilt angle θ(z) monotonically decreases from bottom plate to the midplane, Vs* is for nonmonotonic symmetric bend where the tilt angle θ(z) first increases and then decreases from bottom to the midplane, and Va for the asymmetric bend. Among them, the Hs* and Ha configurations can only be found for LCs with positive dielectric anisotropy under sufficiently strong field. Similarly, Vs* and Va exist only for LCs with negative dielectric anisotropy under sufficiently strong field but, as we shall show, are unstable to twist state (T). The director field in the plane parallel to the bounding plates is assumed to be uniform.

In this work, we aim at a thorough parameter study of equilibrium configurations in a nematic pi-cell under an electric field. We do not consider the switching among the topologically distinct configurations in this work. The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the mathematical model, where the distortion energy of the director field in the pi-cell is modeled with the one-dimensional Oseen-Frank elastic theory, and the electric field satisfies the Maxwell equations. The Euler-Lagrange equations and the corresponding first integrals for the equilibrium configurations are derived. In Section 3, the results of the equilibrium configurations in the absence of electric field are presented in terms of the elastic constants and the boundary pretilt angle. In Section 4, we show the effect of the electric field on the equilibrium configurations. We summarize the paper in Section 5.

2 Mathematical model

In this section, we first present the free energy of the system, featuring the Oseen-Frank elastic energy and the electric energy. We then derive the Euler-Lagrange equations and corresponding first integrals which determine the equilibrium director fields.

2.1 Free energy

In this work, we assume that the orientation field of the nematic liquid crystal is uniaxial and has a constant scalar order parameter throughout the cell, thus can be described by the unit vector field n(x). We take the free energy due to the distortion in the director field n as given by Oseen-Frank theory (Oseen, 1933; Frank, 1958),

Here K1, K2, and K3 are the elastic constants corresponding to splay, twist, and bend distortions, respectively, and the combination K2 + K4 is the saddle-splay constant. This energy is bounded from below if K1 ≥ 0, K2 ≥ 0, K3 ≥ 0, K2 ≥|K4|, and 2K1 ≥ K2 + K4 ≥ 0 (Ericksen, 1966). The last term, known as null Lagrangian, can be integrated by divergence theorem and becomes a surface term, which depends on the director variation along the bounding surface. Since we consider strong anchoring on the surface, this becomes an additive constant in the energy, thus can be ignored.

The electric energy is given by (cf. (Lagerwall, 1999))

where the electric displacement is D = ɛ(n)E, with the dielectric tensor

The constants ɛ‖ and ɛ⊥ are the relative dielectric permittivities of the liquid crystal when the field is parallel and perpendicular to the director, respectively. The difference ɛa = ɛ‖ − ɛ⊥ is the dielectric anisotropy of the liquid crystal. For materials with positive dielectric anisotropy, that is, ɛa > 0, the molecules prefer to align parallel with the electric field; whereas for materials with negative dielectric anisotropy, that is, ɛa < 0, the molecules prefer to align perpendicular to the electric field.

It is well known that the electric field will be altered by the director distortion, whereas the influence of the director on the magnetic field is negligible (Deuling, 1972; Gartland, 2020). An accurate model of electric field involves solving the Maxwell’s equations

under the assumption that there are no free charges in the cell. The curl free condition on the electric field gives immediately E = −∇U, where U is the electric potential. In this work, we consider that the electric potential difference is applied parallel to the normal of the bounding plates along the z − direction, and assume that both the director field and electric field are functions of z, that is

and the director n(z) adopts the usual parametrization

where the polar angle θ is measured from z − axis, and the azimuthal angle ϕ is measured from x − axis. Following the similar treatment as in (Deuling, 1972), the z − component of electric displacement D(z) is a constant, that is,

and the electric potential difference across the cell is

We note that there is no singularity in the integrand since ɛa/ɛ⊥ > −1. With Eq. 8, the electric energy (2) can be written as

where A is the area of the bounding plates, and d is the gap thickness.

We define the following dimensionless parameters,

where k1, k2, γ ∈ (−1, ∞), the cell thickness is rescaled to π, and the parameter α, which is proportional to

where

The electric field,

It is also useful to define the dimensionless parameter

and α and δ are related, via Eq. 8, as

Using Eq. 17, the total free energy in (11) can be written as

We will use this equation for subsequent calculations for the energies of the equilibrium configurations. For convenience, we drop the bar from the variable

2.2 Euler-Lagrange equations and first integrals

Setting the first variations of the free energy functional in Eq. 11 with respect to θ and ϕ to zeros, and utilizing Eq. 17, we obtain the Euler-Lagrange (EL) equations for θ and ϕ,

Multiplying Eq. 19 by θ′, Eq. 20 by ϕ′, adding them together, and integrating the result with respect to z, we obtain a first integral

Integrating Eq. 20 with respect to z yields another first integral

Here C and k are constants of integration. We note that from Eqs 18, 21, the free energy density is invariant in space and is proportional to the integration constant C.

Since the director fields of splay and bend configurations are constrained to lie in a plane orthogonal to the bounding plates, ϕ(z) is a constant, and the EL equations reduce to a single equation for θ(z). The boundary conditions for splay, bend, and twist configurations differ drastically because of the different underlying topologies. To conveniently describe the transitions among different configurations, we further manipulate those differential equations, together with symmetry properties and boundary conditions, to obtain algebraic equations which, upon solving, give the essential quantities associated with each configuration, e.g. integration constants C and k, the extreme tilt angle θm, and energy F. We discuss the details for each configuration separately in the subsections below.

2.2.1 Splay configuration

For the splay configuration, the azimuthal angle ϕ(z) is constant, so Eq. 22 is automatically satisfied with k = 0, and Eq. 21 simplifies to

Separating the variables, we get

where the plus sign is adopted if θ increases with z, and the minus sign is adopted otherwise. Eq. 24 provides the implicit relation between θ and z.

The boundary conditions specifying the pretilt angles for the splay configuration are given by

where 0 ≤ θ0 ≤ π/2, and are illustrated in Figure 1B, where the pretilt angles are formed by the director n at the boundary plates with the positive z − axis for the Hs, Hs*, and Ha configurations. Eqs 17, 24–26 determine the solution θ(z) for the splay configuration for given θ0 and α.

Below, we comment briefly on the monotonicity of θ(z) and its associated symmetry property. We first show that in the absence of electric field, the solution θ(z) for the splay configuration is monotonic. If θ0 = π/2, then θ(z) ≡ π/2, which is automatically monotonic. If θ0 ≠ π/2, the monotonicity can be shown by contradiction. Since if otherwise, θ(z) possesses a local extremum at an interior point z = z∗ such that θ′(z∗) = 0, then θ′(z) ≡ 0 by setting δ = 0 in Eq. 23, and θ(z) is a constant, violating the boundary conditions Eqs. 25, 26. As we shall show in Section 4, monotonic splay configurations only exist if α is smaller than a positive threshold value αcs, beyond which θ(z) becomes nonmonotonic.

Furthermore, if θ(z) is monotonic, the plus sign is taken in Eq. 24. Integrating Eq. 24 in (0, z), we have

and integrating Eq. 24 in (π − z, π) gives

Equating the right hand sides of Eqs 27, 28, we obtain the symmetry property for monotonic θ(z), that is,

Further manipulations of equations are different for monotonic and nonmonotonic splay configurations, which we defer to Sections 3 and 4.

2.2.2 Bend configuration

The EL equation for bend configuration is the same as that for splay configuration,

So is the implicit relation between θ and z,

The boundary conditions for bend configuration are

with 0 ≤ θ0 ≤ π/2. Eqs 17, 31–33 determine the solution θ(z) for the bend configuration for given θ0 and α.

Similar to the splay configuration, the solution θ(z) for bend configuration is monotonic in the absence of electric field and continues to be monotonic for α > αcb, with the threshold value αcb < 0. For α < αcb, θ(z) becomes nonmonotonic. With the similar argument as in the splay configuration, one can show that if θ(z) is monotonic, it satisfies the symmetry property

2.2.3 Twist configuration

For twist configuration, one has to solve the full set of Eqs 17, 21, 22, together with boundary conditions

where 0 ≤ θ0 ≤ π/2, and ϕ0 is an arbitrary angle. We set ϕ0 = 0 such that the director on the boundary lies in the xz − plane. The boundary condition ϕ(π) = ϕ0 + π is for the right-handed twist configuration, and ϕ(π) = ϕ0 − π is for left-handed twist: each is equally probable. We focus on the right-handed twist for further analysis.

We seek the solution θ(z) in twist configuration which is unimodal, that is, θ(z) possesses only one local extreme for z ∈ (0, π). Generally speaking, if θ(z) possesses multiple local extremum points, the corresponding configuration often has high energy due to the rapid variations in θ(z), so we do not consider those solutions. Following the similar line of argument as for the splay configuration, we can show that if θ(z) is a unimodal function, then θ(z) is symmetric with respect to the midplane, that is

Meanwhile, one can also establish the symmetric relation for ϕ(z), using Eq. 22,

Combining Eqs 21, 22, 37, we get

Separating the variables in Eq. 21, via Eqs 22, 39, yields

Integrating Eq. 40 from z = 0 to z = π/2 leads to

Similarly, by Eqs 22, 38, 40, we obtain

In Eqs 41, 42, the positive signs are taken for increasing θ(z) or θm > θ0, which we refer to as a large tilt twist, and the negative signs are taken for decreasing θ(z) or θm < θ0, which we refer to as a small tilt twist.

Eqs 41, 42 relate θ0, θm, δ, and k. Given any two quantities, we can solve for the other two. It is important to point out that there might be zero, one, or two values of θm corresponding to a given θ0, as shown in Figures 2–4 in Section 3. The direct method which solves θm in terms of α and θ0 is an involved procedure, especially when the number of solutions is not known a priori (Scheffer, 1978). However, there is always a unique value θ0 for each given θm ∈ [0, π/2]. With this, our strategy is to solve for θ0 for a given θm. First, for a given set of δ/k2 and θm, the pretilt angle at the boundary θ0 is numerically solved from Eq. 42. In this work, we used the FindRoot function in Wolfram Mathematica 10 as our numerical solver. Knowing the values of θ0, k can be evaluated by multiplying Eq. 41 by k throughout. Next, α can be obtained by Eq. 17, which can be written, upon substituting Eq. 40 and rearranging, as

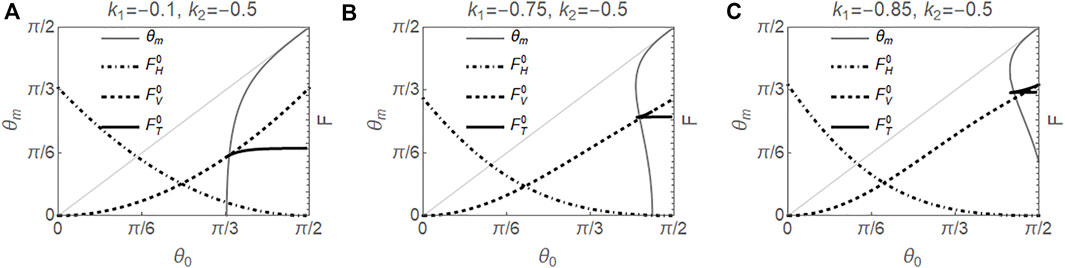

FIGURE 2. Results for k2 = 0 in the absence of electric field. Left axes show θm vs. θ0 for the twist configuration, and right axes show the scaled energies for splay

This enables us to relate the tilt angle θm at the midplane with θ0 and α. Furthermore, the energy for the resulting configuration can be expressed as

Special cares have to be taken in the above procedure, since in both Eqs 41, 42, the radicand cannot be negative, and proper signs need to be chosen based on the monotonicity of θ(z). Since f(θ) > 0, the denominator of the radicand has to be positive, that is,

for θ in between θ0 and θm. We note that since h(θm) = 0, the sign of h′(θm) alone determines the monotonicity of θ(z) such that the nonnegative requirement of the radicand is satisfied. Specifically, if h′(θm) > 0, then θ is necessarily greater than θm to ensure h(θ) > 0. This gives θ0 > θm, hence θ′ < 0, and the minus signs are adopted in Eqs. 41, 42. If h′(θm) < 0, θ is necessarily less than θm to satisfy h(θ) > 0, thus θ0 < θm, which gives θ′ > 0, and the positive signs are adopted. If h′(θm) = 0, then θ0 = θm. In this special case, the twist configuration has a constant tilt angle and a uniform twist with ϕ′ = 1. From Eqs 22, 17, we obtain k = g(θ0) and

It is important to note that in the limiting case of θm → 0, ϕ(z) approaches a step function with ϕ = 0 at the lower half and ϕ = π at the upper half of the cell, with ϕ not uniquely defined at the midplane. This is illustrated by the dotted curves in Figure 11 in Section 4. Due to the head-to-tail symmetry of n, that is, n and − n refer to the same orientation, we recognize that twist configuration becomes bend as θm → 0. Since twist configuration can be transformed to a bend configuration through a continuous mapping, and vice versa, those two configurations are topologically equivalent.

3 Solutions in the absence of electric field

Let’s first consider the equilibrium configurations in a pi-cell without the electric field. We first obtain the energies for splay, bend, and twist equilibrium configurations in Sections 3.1, 3.2 and 3.3, and the results are shown in Section 3.4.

3.1 Splay configuration

We showed earlier in Section 2.2.1 that in the absence of electric field, θ(z) for splay configuration is monotonic, hence satisfies the symmetry relation Eq. 29, which gives θ(π/2) = π/2. Setting δ = 0 in Eq. 23, we obtain CS = (1 + k1)θ′(π/2)2. Since θ(z) is increasing, the plus sign is taken in Eq. 24. Integrating Eq. 24 from z = 0 to z = π/2 and rearranging gives

Together with Eqs 18, 23, the energy for the splay configuration can be written as

It can be readily shown that the energy for the splay configuration increases with k1 and decreases with θ0.

3.2 Bend configuration

Similarly, for bend configuration, the symmetry relation Eq. 34 implies θ(π/2) = 0. Setting δ = 0 in Eq. 30, we have CB = θ′(π/2)2. Since θ(z) is monotonically decreasing, the negative sign is taken in Eq. 31. Integrating Eq. 31 from z = 0 to z = π/2 and rearranging gives

The energy for the bend configuration, using Eqs 18, 30, can be written as

It follows that the energy for the bend configuration increases with both k1 and θ0.

3.3 Twist configuration

If δ = 0, Eq. 45 simplifies to

and the sign of h′(θm) follows that of g′(θm). Given θm, θ0 is solved from Eq. 42, which by setting δ = 0, becomes

where the plus sign is taken if g′(θm) < 0, and the minus sign is taken otherwise. Once θ0 and θm are known, k can be evaluated by setting δ = 0 in Eq. 41 and rearranging, that is,

Together with Eqs 21, 22, one obtains CT = k2/g(θm), and the corresponding energy for the twist configuration can be evaluated as

3.4 Results

In this section, we show the results of equilibrium configurations in a pi-cell in the absence of electric field with three representative values of k2 = 0, −0.5, −0.75, and k1 is allowed to vary continuously from −1 to ∞.

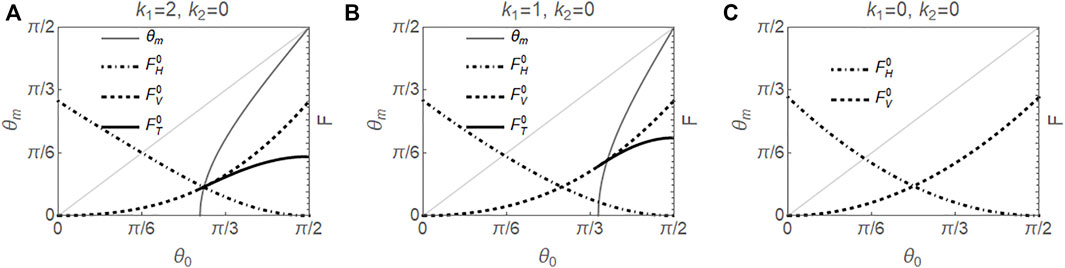

3.4.1 k2 = 0

For k2 = 0, since g′(θm) = sin 2θm > 0 for θm ∈ (0, π/2), the minus sign was adopted when solving Eq. 51, and θm < θ0. Therefore all twist solutions, if they exist, have small tilt angles in the midplane, as shown in Figure 2 where the solid curves for θm lie below the diagonal. Figure 2 also shows energies of equilibrium splay, bend, and twist solutions as functions of θ0, calculated from Eqs 47, 49, 53, respectively.

For higher values of k1, as θ0 increases, there is a twist solution branching from the bend solution as a supercritical bifurcation, indicating a second order transition, as shown in Figures 2A,B. Beyond the bifurcation point, the twist solution corresponds to a local minimum energy state, and bend solution corresponds to a saddle point in the energy landscape. The bifurcation point moves towards π/2 as k1 decreases and becomes larger than π/2 and nonphysical at k1 = 0, as shown in Figure 2C, where there is no twist solution for any θ0 ∈ (0, π/2). We note that the case of k1 = k2 = 0 corresponds to the situation usually referred to as the one constant approximation.

On the other hand, the splay solution always corresponds to a local minimum energy state. The energy curves of splay and bend intersect at a θ0c, which increases with k1. In particular, the two energies are the same when θ0c = π/6 for k1 → −1, θ0c = π/4 if k1 = 0, and θ0c = π/3 as k1 → ∞.

3.4.2 k2 = −0.5

The parameter k2 = −0.5 is a typical value for MBBA (Haller, 1972; Leger, 1972). Similar to the case of k2 = 0, since

FIGURE 3. Results for k2 = −0.5 in the absence of electric field. Left axes show solutions θm vs. θ0 for the twist configuration, and right axes show the scaled energies for splay

In the case that there are two twist configurations for a given θ0, the one with the larger θm corresponds to a local minimum energy state, the other, with smaller θm, is a local maximum energy state, and the bend state is a local minimum state. If the system is excited to a high energy configuration and then allowed to relax, the resulting configuration depends sensitively on which attraction basin that high energy configuration resides in.

3.4.3 k2 = −0.75

If k2 = −0.75, g′(θm) = (1–1.5 sin2θm) sin 2θm is positive if θm ≲ 0.955, and negative otherwise. It follows that the twist configurations are with large tilt angle when θm ≳ 0.955, as shown in Figure 4 where the curve of θm is above the diagonal. Figures 4B,C clearly show the first order transition between bend and twist as θ0 varies at small values of k1, and the bifurcation point shifts to smaller values of θ0, compared with the results from k2 = −0.5.

FIGURE 4. Results for k2 = −0.75 in the absence of electric field. Left axes show solutions θm vs. θ0 for the twist configuration, and right axes show the scaled energies for splay

As can be seen from Figures 2–4, the splay (H) is always a locally stable configuration and has lower energy than those of the bend (V) and twist (T) at large pretilt angles. However, the system will not automatically be in the global minimum energy state. In fact, the configuration the system adopts depends sensitively on the initial condition. If an electric field is applied to align the directors in the interior to be parallel to the plates, then after the field is removed, the system will relax to the splay (H) configuration. On the other hand, if the field is to align the directors parallel to the normal direction, then after the field is turned off, the system will relax to either bend (V) or twist (T) configuration, depending on which attraction basin that initial high energy configuration resides in.

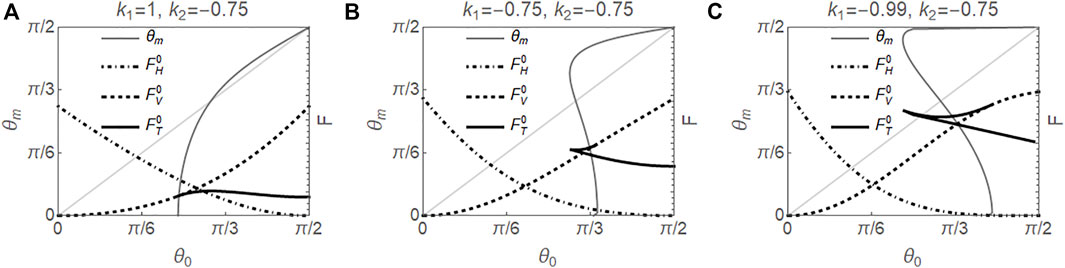

Figure 5 shows the phase diagrams for the stable bend (V) and twist (T) configurations in terms of k1 and θ0 for those three values of k2. As noted above, the bend (V) or twist (T) configuration can only be observed if the system is relaxed from an excited state with the director field in proximity of homeotropic configuration, where the directors in the interior of the cell are perpendicular to the plates. Dashed curves indicate the spontaneous second order transitions as θ0 varies, and thick solid curves indicate spinodal lines where the bend (V) configuration loses its local stability at the upper solid curve, and the twist (T) configuration loses its local stability at the lower solid curve. The regions enclosed by these solid curves contain one locally stable bend (V) and one locally stable twist (T) configuration. The thin curves in the bistable region mark the first order transitions where the free energies of the bend (V) and twist (T) are the same. Specifically, for k2 = 0, containing the one constant approximation case, if k1 > 0, there is a second order transition from bend to twist as θ0 increases, whereas equilibrium twist configuration does not exist if k1 < 0, as shown in Figure 5A. For k2 = −0.5, the transition from bend to twist is second order for larger k1 and becomes first order for smaller k1, as shown in Figure 5B. The transition for k2 = −0.75 is similar to that of k2 = −0.5, except that the bistable region becomes much larger and shifts to smaller values of θ0. Those results are consistent with the fact that the twist distortion is energetically cheap for small k2, and the bend distortion is expensive for large k1 and θ0.

FIGURE 5. Phase diagrams for locally stable bend and twist configurations in the absence of electric field in terms of k1 and θ0 for (A) k2 = 0, (B) k2 = −0.5, and (C) k2 = −0.75. The second order transitions between bend and twist configurations are represented by dashed curves. The thick solid curves are spinodal lines where the bend (V) configuration loses its local stability at the upper solid curve, and the twist (T) configuration loses its local stability at the lower solid curve. The thin curves in between mark the first order transitions where the free energy of the bend (V) is the same as that of the twist (T). These phases are observable when the LC director field is relaxed from the homeotropic configuration where interior directors are aligned perpendicular to the plates. We note that splay is always a locally stable configuration, not shown in the phase diagrams, and can be realized when the system is relaxed from the homogeneous configuration where the interior directors are aligned parallel to the plates.

Porte and Jadot (Porte and Jadot, 1978) have considered the transition between twist and bend configurations of a twisted nematic liquid crystal cell induced by the pretilt angle at bounding surfaces. When the overall twist is π, it is equivalent to the pi-cell. The authors concluded that the order of transition between bend and twist depends only on the value of k2. In particular, they claimed that the second order transition occurs for k2 ≤ −0.5 and first order transition occurs for k2 > − 0.5. As we just showed, our results are in contrast with those in (Porte and Jadot, 1978); the order of transition between the bend and twist indeed depends on both values of k1 and k2. Specifically, second order transition occurs for larger values of k1 for all values of k2, and first order transition occurs for smaller values of k1 for k2 = −0.5, −0.75.

4 Solutions under an electric field

In this section, we study the configuration transitions for a nematic pi-cell under an electric field. As we shall show in Section 4.1, the symmetric splay configuration becomes asymmetric splay as α increases, and in Section 4.2, the bend configuration becomes twist as α decreases, and vice versa.

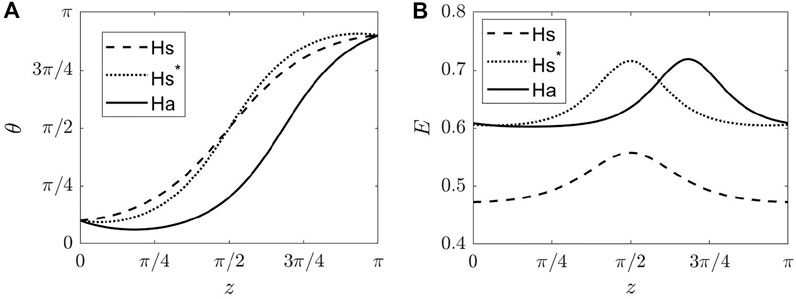

4.1 Splay configurations

When an electric field is applied perpendicular to the pi-cell with ɛa < 0 and initial splay configuration, the splay configuration is reinforced as the field tends to align the director parallel with the bounding plates, hence θ(z) approaches π/2 everywhere in the cell and remains monotonic, as illustrated by the dashed curve in Figure 6A. However, if ɛa > 0, the field tends to align the director parallel with the cell normal, and θ(z) tends to either 0 or π everywhere in the cell. Beyond a threshold voltage αcs, θ(z) loses its monotonicity and two nonmonotonic splay configurations are found: a symmetric splay (Hs*) and an asymmetric splay (Ha), illustrated by the dotted and solid curves in Figure 6A, respectively. We remark that the symmetric configuration Hs* is unstable to Ha under an asymmetric perturbation of the solution. Figure 6B shows the corresponding electric field variations in the cell for each configuration in A. We note that the relation between the magnitude of the electric field and tilt angle is given in Eq. 16.

FIGURE 6. Representative solutions for splay configurations in a pi-cell under an electric field, obtained with Matlab numerical package BVP5c. The (A) tilt angle θ and (B) corresponding nondimensionalized electric field are shown. The dashed curve for Hs represents the solution for α = 2.5, and the dotted and solid curves represent the symmetric (Hs*) and asymmetric splay (Ha) configurations when α = 4, respectively. Parameters used are k1 = k2 = 0, θ0 = π/10, γ = 0.2, αcs ≈ 2.9.

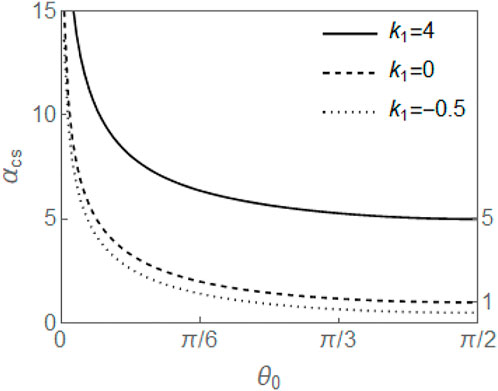

The threshold voltage can be found by recognizing that at αcs, θ′(0) = θ′(π) = 0. Then from Eqs. 17, 23, 24, we obtain

The singularity in the integrand at θ0 in Eq. 54 can be removed by the change of variables, sin λ cos θ0 = cos θ, which gives

The threshold values αcs in terms of θ0 are plotted in Figure 7 for three values of k1. The critical voltage decreases with θ0 and increases with k1. As θ0 → π/2, αcs → 1 + k1, which is consistent with the result of

To study the nature of the transitions among Hs, Hs*, and Ha, we show necessary steps leading to energy calculation for each of them in detail below.

4.1.1 Monotonic splay configuration (Hs) (α < αcs)

For small voltages α < αcs, the splay configuration remains monotonic. Substituting Eq. 24 into Eq. 17, we have

For a given θ0 and α, we first solve Cs/δ from Eq. 56 or Eq. 57. Once Cs/δ is known, δ can be evaluated by integrating Eq. 24 from z = 0 to z = π/2 and rearranging, which gives

Now that Cs is known, the energy for the monotonic splay configuration is then

4.1.2 Symmetric splay configuration (Hs*) (α > αcs)

For voltages above the critical value α > αcs, θ(z) is no longer monotonic. Assuming the solution continues to have the mirror symmetry, θ(π − z) = π − θ(z), then we only need to focus on the bottom half. In this half of the cell, θ(z) first decreases in

and increases back in

where the plus sign is taken for

where sin λ0 cos θm = cos θ0. In Eq. 61 and similar ones hereinafter, both integrals on the right hand sides share the same integrand. The integrand in the first integral is omitted to make the presentation compact.

For given θ0 and α, θm is determined from Eq. 61. We note the right hand side of Eq. 61 is a continuous decreasing function of θm in (0, θ0). This guarantees the existence of the solution θm for each α > αcs. Once θm is known, δ can be calculated by integrating Eq. 60 from z = 0 to z = π/2 and rearranging to get

The energy is then given by

4.1.3 Asymmetric splay configuration (Ha) (α > αcs)

Since the asymmetric splay configuration is nonmonotonic, the corresponding θ(z) necessarily possesses an interior local extremum. In fact, there is one such configuration where θ1(z) possesses a local minimum, and another where θ2(z) possesses a local maximum. We focus on the first configuration as the other is related by θ1(π − z) = π − θ2(z).

Now since θ(z) has a local minimum, it follows that θ(z) decreases from z = 0 and reaches its local minimum θm at

and increases back for

where the plus sign is taken for

where sin λ0 cos θm = cos θ0.

Given θ0 and α, we first solve θm from Eq. 66. Similar to the case of the nonmonotonic symmetric Hs*, the right hand side of Eq. 66 is a continuous decreasing function of θm in (0, θ0), which guarantees the existence of the solution θm for any α > αcs. Once θm is known, δ can be evaluated by integrating Eq. 65 from z = 0 to z = π and rearranging for

and the energy for the asymmetric splay configuration can be evaluated by the same equation as Eq. 63.

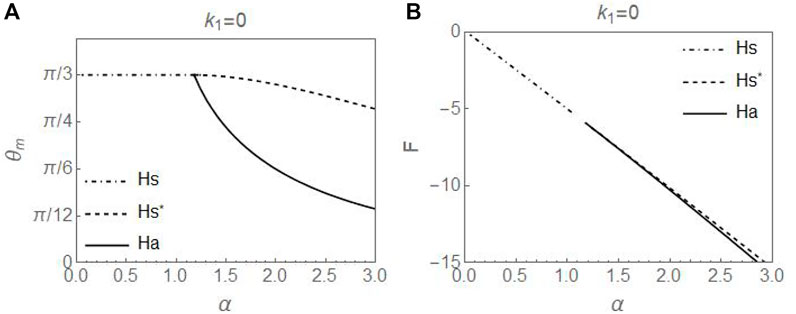

The results in Sections 4.1.1 4.1.2, and 4.1.3 are exemplified in Figure 8, which shows the representative minimum tilt angles θm and associated energies for Hs, Hs*, and Ha for one specific set of parameters. It clearly shows that the Ha state branches off from the Hs state as a second order transition at αcs and possesses lower energy than that of the Hs* configuration. We note that the results are independent of values of k2.

FIGURE 8. The (A) minimum values θm and (B) associated energies of symmetric monotonic (Hs), symmetric nonmonotonic (Hs*), and asymmetric (Ha) splay configurations as functions of α. Parameters used are k1 = 0, θ0 = π/3, γ = 0.2.

4.2 Bend and twist configurations

We have shown in Section 3 that bend and twist configurations can be transitioned into one another by varying the boundary pretilt angles, and the transitions can be either first order or second order depending on the material parameters. In this section, we show how the electric field affects both configurations and the transitions between them.

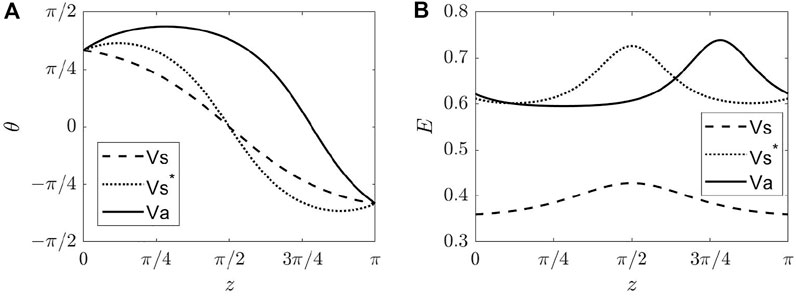

When an electric field is applied across the pi-cell with initial bend configuration and the nematic has ɛa > 0, the bend configuration is reinforced, since the field tends to align the director parallel to the field direction, and θ(z) remains monotonic, as illustrated by the dashed curve in Figure 9A. However, if ɛa < 0, the field tends to align the director parallel with the bounding plates, and θ(z) increases in its magnitude as voltage increases. Here, we consider two scenarios: first, we confine the directors lying in the xz − plane; second, the directors are allowed to have nonvanishing out-of-plane components.

FIGURE 9. Representative solutions for bend configurations in a pi cell for LCs with ɛa < 0. The (A) tilt angle θ(z) and (B) corresponding nondimensionalized electric field are shown. The dashed curve for symmetric bend configuration (Vs) is obtained when α = −1.5, and the dotted and solid curves for the symmetric (Vs*) and asymmetric (Va) bend configurations are obtained when α = −4. Parameters used are k1 = k2 = 0, θ0 = π/3, γ = −0.2, αcb ≈ − 2.

In the first scenario, the bend configuration loses its monotonicity beyond a threshold voltage. Similar to the case of splay configuration, we found a symmetric (Vs*) and an asymmetric (Va) nonmonotonic equilibrium bend configuration, as shown as the dotted and solid curves in Figure 9A. Further calculations show the asymmetric one having less energy than that of the symmetric. We omit the detailed calculations here as the analyses are identical to the case of splay configurations aside from the different boundary conditions and the nonmonotonic solution existing for ɛa < 0.

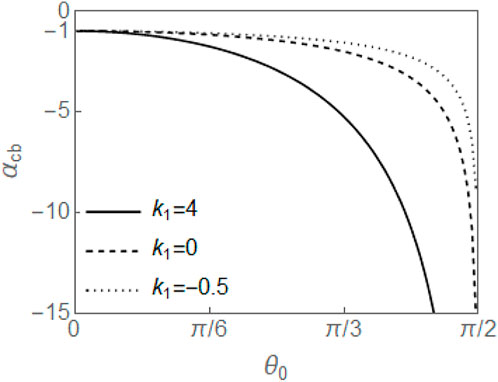

The threshold αcb can be found by recognizing that at α = αcb, θ′(0) = θ′(π) = 0. Using Eqs 17, 30 and 31, and the transformation cos λ sin θ0 = sin θ, the threshold value αcb is given by

The threshold values αcb in terms of θ0 are plotted in Figure 10 for three values of k1. The critical voltage increases with θ0 and with k1. As θ0 → 0, αcb → −1, which is independent of k1. This is consistent with the critical voltage

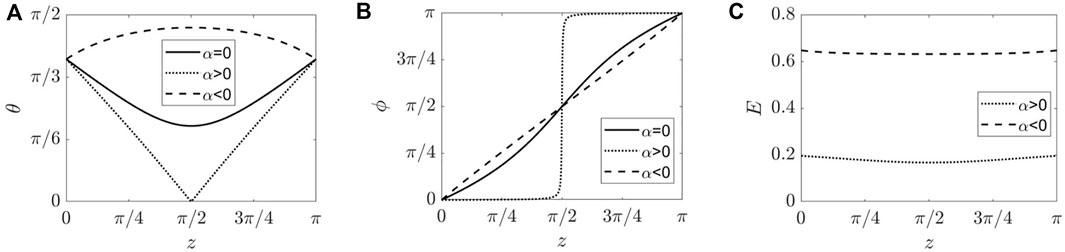

In the second scenario, the bend configuration is subject to out-of-plane perturbation. For sufficiently high voltages, the bend becomes twist. To study the configuration transition between bend and twist as α varies, we carry out the calculations for the twist configurations under an electric field as described in Section 2.2.3 and find the critical voltage when θm becomes zero, an indicator for the transition from twist to bend. Figure 11 shows three representative solutions of (A) θ(z), (B) ϕ(z), and (C) the magnitude of the electric field of twist configurations in a pi-cell for the cases α = 0, α > 0, and α < 0. If ɛa < 0, the tilt angle increases with α, and the configuration remains as twist, shown as dashed curves. However if ɛa > 0, the tilt angle decreases with α. At a threshold voltage, depicted by the dotted curve, the tilt angle at the midplane θm goes to 0, and ϕ approaches a step function with ϕ = 0 at lower half and ϕ = π at the upper half of the cell. It follows that the twist configuration becomes bend.

FIGURE 11. Representative solutions for twist configurations in a pi-cell with α = 0, 0.32, and − 4. The (A) tilt angle θ(z), (B) corresponding azimuthal angle ϕ(z), and (C) corresponding nondimensionalized electric field are shown. Parameters used are k1 = 1, k2 = 0, θ0 = 1.2, |γ| = 0.2.

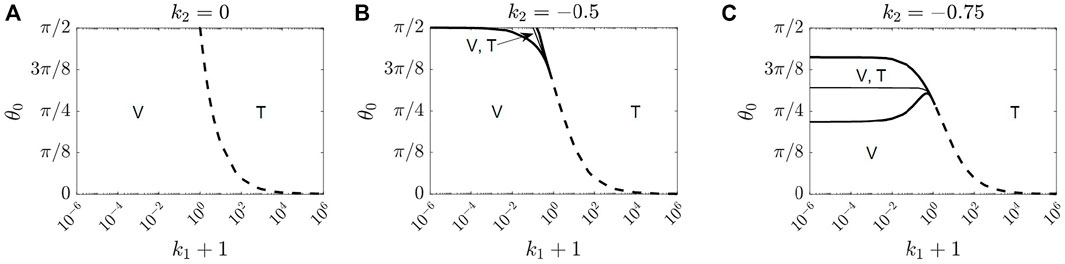

Figure 12 shows the phase diagrams for stable bend and twist configurations in terms of θ0 and α with three representative sets of material parameters. Figure 12A with k1 = k2 = 0, Figure 12B with k1 = −0.1, k2 = −0.5, and Figure 12C with k1 = k2 = −0.75, separately represent the parameter sets where there is no transition, a second order transition, and a first order transition from bend to twist configurations as θ0 varies in the absence of an electric field. In Figure 12C, there are two critical boundary pretilt angles at α = 0 (also shown in Figure 4B), with the smaller one corresponding to the critical θ0 below which the twist solution loses its local stability, and the larger one corresponding to the critical θ0 beyond which the bend solution loses its local stability. In between these two angles, both bend and twist are locally stable. The bistable region shrinks as α decreases and second order transition takes over. In all three cases, the threshold voltage for the transition from bend to twist decreases with θ0, whereas the threshold voltage for the transition from twist to bend increases with θ0.

FIGURE 12. Phase diagrams for locally stable bend and twist configurations in terms of θ0 and α for (A) k1 = k2 = 0, (B) k1 = −0.1, k2 = −0.5, and (C) k1 = −0.75, k2 = −0.75. Dashed curves indicate that the transition between bend (V) and twist (T) configurations is second order. Solid curves indicate the spinodal lines where the bend and twist lose their local stabilities at the lower and upper solid curves, respectively, and in between the two solid curves are two locally stable states Vs, and T.

We remark that the transitions from monotonic bend to twist always occur at an αct ≥ −1, as shown in Figure 12, whereas the transitions from monotonic bend to nonmonotonic bend always occur at αcb ≤ −1, as shown in Figure 10. Therefore, the transition from bend to twist occurs at a lower voltage, thus the latter transition is preempted and typically not observable.

5 Summary

In this work, we have conducted a detailed parameter study of equilibrium states in a nematic pi-cell under an electric field applied perpendicular to the bounding plates. The distortion of liquid crystals is modeled with the one-dimensional Oseen-Frank director model, and the effect of director distortion on the electric field has been incorporated.

In the absence of electric field, the equilibrium splay, bend, and twist configurations all possess certain symmetries with respect to the midplane. The splay configuration is always locally stable. Bend is always stable for small θ0, the pretilt angle at the boundary. As θ0 increases, bend is likely to lose its stability to twist if k2 is small, where twist configuration is energetically cheap, or if k1 is large, where the energy cost for the bend configuration is large. A range of θ0 where both bend and twist are locally stable is found for small k1 and k2 ≤ −0.5. Our results are in contrast with those in (Porte and Jadot, 1978), where the authors reported that the second order transition between bend and twist occurs for k2 ≤ −0.5, and first order transition occurs for k2 > − 0.5, whereas, we have shown that second order transition occurs for larger values of k1 and for all k2 and first order transition occurs for smaller values of k1 and k2.

When a voltage difference is applied perpendicular to the pi-cell, the configuration transitions depend on the initial configuration and the sign of the dielectric anisotropy. Starting from the splay configuration and ɛa > 0, the symmetric splay continuously transitions to asymmetric splay at a threshold voltage. If the initial configuration is bend (twist) and ɛa < 0 (ɛa > 0), then bend (twist) configuration becomes twist (bend) for sufficiently high voltages. The transition between bend and twist is likely to be second order for large values of k1 and for small θ0 and could be first order for small values of k1 and k2 and large θ0.

Our results based on the one-dimensional Oseen-Frank director model cannot describe the transitions between splay and bend/twist configurations as the switching among those topologically distinct configurations would require at least a two-dimensional model or a tensor description (Amoddeo and Barberi, 2021) of orientation field where the disclinations are allowed. With that said, our results will help to predict the equilibrium configurations after the voltage is removed and the voltage required to ensure that an asymmetric splay, bend or twist configuration is achieved given the material parameters and the pretilt angle at the boundary.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

The authors contributed equally to the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The handling Editor HY declared a shared affiliation with the authors at the time of review.

The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Amoddeo, A., and Barberi, R. (2021). Phase diagram and order reconstruction modeling for nematics in asymmetric pi-cells. Symmetry 13 (11), 2156. doi:10.3390/sym13112156

Berreman, D. W., and Heffner, W. R. (1980). New bistable cholesteric liquid crystal display. Appl. Phys. Lett. 37 (1), 109–111. doi:10.1063/1.91680

Berreman, D. W., and Heffner, W. R. (1981). New bistable liquid crystal twist cell. J. Appl. Phys. 52 (4), 3032–3039. doi:10.1063/1.329049

Bos, P. J., and Beran, K. R. (1984). The pi-cell: A fast liquid-crystal optical-switching device. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 113 (1), 329–339. doi:10.1080/00268948408071693

Boyd, G. D., Cheng, J., and Ngo, P. D. T. (1980). Liquid crystal orientational bistability and nematic storage effects. Appl. Phys. Lett. 36 (7), 556–558. doi:10.1063/1.91578

Bryan-Brown, G. P., Towler, M. J., Bancroft, M. S., and McDonnell, D. G. (1994). “October. Bistable nematic alignment using bigratings,” in Proceedings of International Display Research Conference, 209–212.

Deuling, H. J. (1972). Deformation of nematic liquid crystals in an electric field. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 19 (2), 123–131. doi:10.1080/15421407208083858

Dozov, I., and Durand, G. (1998). Surface controlled nematic bistability: From surface anchoring bifurcation to fast displays with video compatibility. Liq. Cryst. Today 8 (2), 1–7. doi:10.1080/13583149808047702

Ericksen, J. L. (1966). Inequalities in liquid crystal theory. Phys. Fluids. 9 (6), 1205–1207. doi:10.1063/1.1761821

Frank, F. C. (1958). I. Liquid crystals on the theory of liquid crystals. Discuss. Faraday Soc. 25, 19–28. doi:10.1039/df9582500019

Gartland, E. C. (2020). Forces and variational compatibility for equilibrium liquid crystal director models with coupled electric fields. Continuum Mechanics and Thermodynamics, 32 (6), 1559–1593.

Haller, I. (1972). Elastic constants of the nematic liquid crystalline phase of p-Methoxybenzylidene-p-n-Butylaniline (MBBA). J. Chem. Phys. 57 (4), 1400–1405. doi:10.1063/1.1678416

Jhun, C. G., Chen, C. P., Lee, U. J., Lee, S. R., Yoon, T. H., and Kim, J. C. (2006). Tristate liquid crystal display with memory and dynamic operating modes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89 (12), 123507. doi:10.1063/1.2354430

Kim, J. H., Yoneya, M., Yamamoto, J., and Yokoyama, H. (2001). Surface alignment bistability of nematic liquid crystals by orientationally frustrated surface patterns. Appl. Phys. Lett. 78 (20), 3055–3057. doi:10.1063/1.1371246

Leger, L. (1972). Static and dynamic behaviour of walls in nematics above a Freedericks transition. Solid State Commun. 11 (11), 1499–1501. doi:10.1016/0038-1098(72)90508-x

Lin, G. J., Chen, T. J., Lin, B. R., Liao, H. I., Chang, Y., Wu, J. J., et al. (2015). Effects of pretilt angle on electro-optical properties of optically compensated bend liquid crystal devices with a mixed polyimide alignment layer. J. Disp. Technol. 12 (3), 302–308. doi:10.1109/jdt.2015.2502722

Oseen, C. W. (1933). The theory of liquid crystals. Trans. Faraday Soc. 29, 883. doi:10.1039/tf9332900883

Porte, G., and Jadot, J. P. (1978). A phase transition-like instability in static samples of twisted nematic liquid crystal when the surfaces induce tilted alignments. J. Phys. Fr. 39 (2), 213–223. doi:10.1051/jphys:01978003902021300

Scheffer, T. J. (1978). Distorted twisted nematic liquid-crystal structures in zero field. J. Appl. Phys. 49, 5835–5842. doi:10.1063/1.324600

Wu, J. J., Hu, S. S., Hsu, C. C., Chen, T. J., and Lee, K. L. (2012). Electro optical characteristics of high-pretilt twisted liquid crystal pi-cells. Appl. Phys. Express 6 (1), 012201. doi:10.7567/apex.6.012201

Yang, D. K., West, J. L., Chien, L. C., and Doane, J. W. (1994). Control of reflectivity and bistability in displays using cholesteric liquid crystals. J. Appl. Phys. 76 (2), 1331–1333. doi:10.1063/1.358518

Yu, X. J., and Kwok, H. S. (2004). Bistable bend-splay liquid crystal display. Appl. Phys. Lett. 85 (17), 3711–3713. doi:10.1063/1.1810215

Keywords: nematic pi-cell, electric field induced transition, pretilt angle, frank-oseen free energy, dielectric anisotropy

Citation: Allen AC and Zheng X (2022) Equilibrium configurations in a nematic pi-cell under an electric field. Front. Soft. Matter 2:984400. doi: 10.3389/frsfm.2022.984400

Received: 02 July 2022; Accepted: 25 July 2022;

Published: 02 September 2022.

Edited by:

Hiroshi Yokoyama, Kent State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Jun-ichi Fukuda, Kyushu University, JapanSeung Hee Lee, Jeonbuk National University, South Korea

Copyright © 2022 Allen and Zheng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaoyu Zheng, eHpoZW5nM0BrZW50LmVkdQ==

Aaron C. Allen

Aaron C. Allen Xiaoyu Zheng

Xiaoyu Zheng