94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Sociol., 07 April 2025

Sec. Sociological Theory

Volume 10 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2025.1504812

This article is part of the Research TopicThe Erosion of Trust in the 21st Century: Origins, Implications, and SolutionsView all 5 articles

In this paper, we examine the relationship between generalized trust and online trust to assess whether the latter is a distinct phenomenon or an extension of the former. For this purpose, we provide an overview of different approaches developed to explain trust and discuss their applicability to online trust. Our analysis is based on a nationally representative sample of Austrians aged 16 or older, collected as part of the latest International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) survey on “Digital Societies,” as well as pretest data for this survey from Austria, Greece, Poland, the Philippines, and South Africa. Regression models considering indicators associated with a wide range of different approaches show that generalized trust is the strongest predictor of online trust. Hence, our findings suggest that online trust is not an independent concept but an extension of generalized trust, supporting the initial notion of generalized trust as a concept that goes beyond personal relationships, now also into the digital world.

The concept of trust, including specific types such as social, generalized, and political trust, has gained significant prominence in the social sciences over the past few decades (Barbalet, 2019; Misztal, 2020; Vrečar, 2025). This growing interest coincides with the rapid rise of the Internet and online communication since the 1990s. Given that, many foundational studies on trust were conducted before the internet era (Rosenberg, 1956; Deutsch, 1958; Lewis and Weigert, 1985; Hardin, 1993; Yamagishi and Yamagishi, 1994; Earle and Cvetkovich, 1995; Fukuyama, 1995), questions arose, such as whether the internet positively or negatively affects trust (Uslaner, 2004) and how trust can be established in online environments (Hardin, 2004).

The present research also addresses the relationship between online and offline trust, but asks a more fundamental question of whether online trust is a distinct phenomenon or a mere extension of offline trust. This question adds notably to the existing literature on digital environments, which focuses often on specific aspects of online trust, such as consumer behavior, reputation systems, and internet transactions (Yoon, 2002; Wang and Emurian, 2005; Mutz, 2005). Additionally, studies frequently investigate specific online interactions, including reputation in internet markets (Khopkar and Resnick, 2009), gaming (Lundmark, 2015; Chen et al., 2016), experiences of discrimination (Näsi et al., 2017), negative impacts of online interactions (Näsi et al., 2015; Pavić and Šundalić, 2016; Hergueux et al., 2021), online trust’s relation to social capital (Zhou et al., 2022), and other topics.

Research on the foundations of online trust is less common. Furthermore, existing literature shows that this research draws on offline trust concepts: For instance, Beldad et al. (2010) link online trust in both commercial and non-commercial contexts to classic offline theories, such as psychological approaches and attitudes. Similarly, Taddeo (2010) applies a rational choice framework, while Antonijević and Gurak (2019) start from Luhmann’s theories. Melanie Green (2007) also adopts a psychological perspective when observing that respondents report significantly lower trust in people on the Internet compared to people in general. We consider generalized trust as an additional source of online trust and build in this regard on insights from research on offline trust that considered the relations between different types of trust, such as Freitag and Traunmüller (2009), Newton and Zmerli (2011), Glanville and Shi (2020), Zheng et al. (2023), and Fairbrother et al. (2024).

Given that the above-mentioned literature on the sources of online trust suggests that online trust shares a similar foundation with offline trust, we first present key theoretical assumptions and their potential extensions to online trust, based on prior reviews by Delhey and Newton (2003, 2005), Nannestad (2008), Delhey et al. (2011), Newton et al. (2018), Schilke et al. (2021), and Vrečar (2025). The different approaches depicted in Table 1 inform the selection of items for our subsequent analysis of the sources of trust. Table 1, therefore, also includes several items, which will be discussed in greater detail in the methods section.

The theories depicted in Table 1 can be divided into approaches focused (a) predominantly on individuals and their traits, perceptions, and evaluations and (b) approaches focused on societies and cultures and their institutional contexts and structural elements. The first individual-level approach is the personality perspective, which posits that trust is a stable trait, largely established in childhood and influenced by early life experiences (Erikson, 1950; Uslaner, 2002). It suggests that trust, whether in online or offline contexts, is associated with a positive outlook on life, including factors such as personal optimism, life satisfaction, and a sense of control. Trust, in this view, remains consistent across different domains, with online experiences having little impact on an individual’s overall level of trust (Uslaner, 2004). The rational choice perspective is another individual-focused approach. It considers trust as a product of cognitive evaluations and experiences. Individuals calculate the likelihood of others being trustworthy based on their past interactions. Positive experiences, particularly in repeated interactions, tend to increase trust, while negative experiences reduce it (Coleman, 1990; Gambetta, 1988). Trust in this context is seen as a rational decision, shaped by the perceived trustworthiness of others and the expected outcomes of trusting relationships (Hardin, 2002). Finally, the social constructivist perspective also emphasizes the role of individual perceptions in shaping trust. Trust is seen as influenced by how people perceive societal structures, conflicts, and inequalities (Larsen, 2013; Frederiksen, 2019). Individuals who view their society as predominantly egalitarian and middle-class, not eroded with cleavages and divisions, are more likely to exhibit high levels of generalized social trust, reflecting their belief in the fairness and stability of their social environment.

Contextual elements are emphasized in the civic culture and values perspective, which links trust to broader cultural processes and civic values. Trust is seen as emerging from democratic traditions, civic engagement, and social capital, which includes networks and norms of reciprocity (Putnam, 1993, 2000; Fukuyama, 1995). This approach suggests that individuals with strong bridging social capital and participative behaviors, both online and offline, are more likely to exhibit high levels of trust. Additionally, trust correlates with egalitarian attitudes and religious backgrounds, particularly Protestantism (Fukuyama, 1995: 283–6; Delhey and Newton, 2005: 318–320). The societal status/ class perspective interprets trust as reflecting the structural characteristics of society, including class, status, and ethnic divisions. Trust is more prevalent among those with higher socioeconomic status, who are more likely to experience stability and security (Patterson, 1999; Wilkinson, 2005; Rothstein and Uslaner, 2005). In the online world, this perspective would suggest that individuals who are better educated, wealthier, and more digitally literate are more inclined to trust others, as they are more familiar with and confident in navigating digital environments. Finally, from an institutional perspective, trust is closely tied to the quality of government and institutional fairness. Trust in others, including in online contexts, often stems from trust in political institutions, particularly those perceived as fair and impartial. This approach posits that individuals who see democratic state institutions as mostly fair and therefore trust them, especially those implementing policy, such as courts and their public officials, are more likely to extend that trust to fellow citizens and strangers, both online and offline (Rothstein and Stolle, 2008).

As mentioned earlier, this research examines the sources of online trust and its relationship with offline trust. More specifically, we focus on generalized trust as the survey we use in our analysis asked about trust in general and not about trust in particular individuals or groups. The literature allows for two opposing perspectives on this relationship between online and offline trust: On one hand, the core idea of generalized trust—the belief that “most people can be trusted” and that trust extends beyond direct, personal interactions (Stolle, 2002; Uslaner, 2002)—suggests that it also extends to online contexts, making online trust a subset of generalized trust. On the other hand, studies on distinctions between generalized and particularized offline trust (Freitag and Traunmüller, 2009), social and political trust (Newton and Zmerli, 2011), and the transition from particular to generalized trust (Glanville and Shi, 2020; Zheng et al., 2023) were also able to demonstrate that trust can take on distinct types. Applying these findings to the relationship between online and offline trust opens the alternative possibility that online trust may represent a separate and unique type of trust.

Our analyses are based on questions from the new International Social Survey Programme1 survey on “Digital Societies,” the ISSP survey on “Health and Health Systems,” and a few country-specific questions that were fielded in a single survey in Austria. The survey is representative of the Austrian population aged 16 and older and was conducted in early 2024. The sample was drawn randomly from the national registry and 3,800 people were invited via postal mail to complete the survey either online or, after two reminders, in a printed mail-in format. The final sample size was 1,546 respondents, which corresponds to a response rate of 40.7%. Our analysis is limited to internet users, as one of the dependent variables is about online trust and was only captured from internet users. Our final sample size is thus 1,434 cases. The data (Hadler et al., 2024) is available at the Austrian Social Science Archive (AUSSDA).

Furthermore, we used the pre-test data from the development of the ISSP Digital Society survey from 2022, which includes samples from Austria, Greece, Poland, the Philippines, and South Africa. These samples did not include all questions of the final survey and followed less strict data collection rules. Therefore, only use them to tentatively check whether our findings on the relation between generalized trust and online trust can also be observed in other countries. Here, the total sample size is 4,055. This second dataset is also available at AUSSDA for replication purposes (Andreadis et al., 2024).

Our dependent variables on trust are measured in the following way: (a) “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you cannot be too careful in dealing with people? Please tick ONE box to show what you think, where 0 means you cannot be too careful, and 10 means most people can be trusted.” This question on generalized trust uses the wording that was introduced in the US General Social Survey in 1972 and has been used ever since widely since then in various surveys including the ISSP, despite debate about its measurement properties (see for example Reeskens and Hooghe, 2008).

The ISSP group developed a similar question for online contacts for its “Digital Societies” survey: (a) “On a scale of 0 to 10, how much do you trust people you are communicating with on the Internet but have never met in person? 0 means you do not trust them at all, and 10 means you trust them completely” with the same answer categories as for the generalized trust. The wording “never met in person” was added after the pre-test to emphasize the online-only aspect and to exclude communication with family, close friends, etc. Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics for these two variables and for all independent variables. The independent variables were selected based on all items in the survey that are related to the different approaches displayed in Table 1.

Our analytical approach is as follows. Initially, we present descriptive results on the two trust variables and their correlations. This is followed by different regression analyses. Given the large number of indicators associated with the different theory approaches, we explored several reduction strategies. We considered factor analyses, which are suitable only for correlated variables and not applicable to socio-demographic variables and other sets of indicators associated with the different approaches. We also explored a stepwise regression, which adds variables based on their explanatory power. However, this method can introduce biases, such as variable omission or overfitting.

Ultimately, we adopted the following two-step approach. In the first step, we ran separate regressions with either generalized trust or online trust as the dependent variable and all independent variables associated with a single theoretical approach (e.g., personality, civic culture, etc.). We recorded which variables remained significant in each combination of trust and theory approach. In the second step, we ran regressions that included all variables identified as significant in these initial regressions. Additionally, we cross-validated the results using alternative approaches, such as regressions including all variables and the stepwise regression mentioned earlier. While the results show slight variations across methods, the main conclusion regarding the relationship between offline and online trust remained consistent.

Finally, before presenting the results of our analyses, we must place our study in a societal context for better interpretation. Austria is considered a medium-trust society (Delhey and Newton, 2005: 315). During the 1990s and early 2000s, social trust, as measured by the “most people can be trusted” question, was around 30 percent and above, according to the integrated World Values Survey Data. Since then, trust has steadily increased to over 40 percent, despite Austria’s rapidly growing ethnic diversity in the past two decades. Similar trends are observed in the ISSP data, where generalized social trust averages around 50 percent on a scale from 0 to 10, reflecting a general faith in fellow citizens (Hadler et al., 2020). Regardless, as pointed out above, we will use the international pre-test dataset to verify some of our national results and check if we see similar findings in other countries.

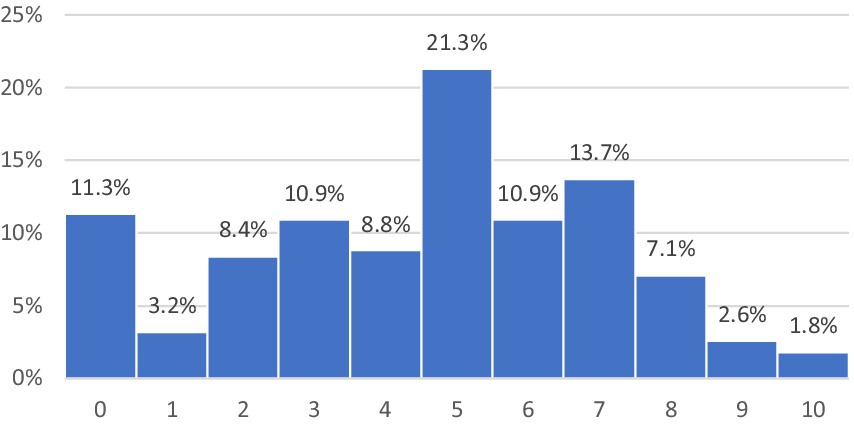

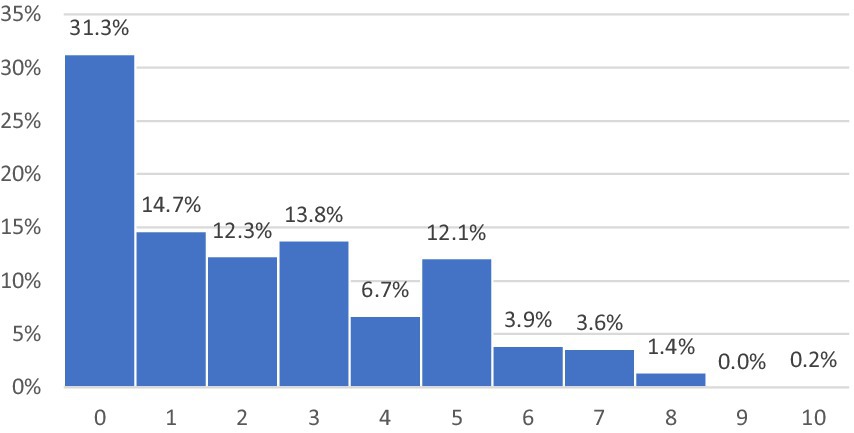

As described in the data section, we first present some basic results on offline and online trust. Figure 1 shows the level of generalized trust and Figure 2 the online trust in the Austrian data from 2024. Both figures are limited to internet users. The distributions show that the online trust is much lower with a large group of respondents indicating no trust at all. This rather low trust is also due to the question wording, which asks specifically for people who you usually do not communicate with. The pre-test data (Andreadis et al., 2024) did not include the term “stranger,” which resulted in a higher level of trust. Regardless of the magnitude, the overlap between offline and online trust is moderate with an overall Pearson correlation of 0.221 in the Austrian data and an overall correlation of 0.164 in the international dataset. The subsequent regression analyses will further explore this question and examine the underlying factors that shape trust.

Figure 1. Generalized Trust (internet users only). Formulation of the question: “In general, what do you think: can you trust people or can you not be careful enough when dealing with people? Please check ONE box to show what you think; where 0 means you cannot be too careful and 10 means you can trust most people.” Source: Austrian sample of the ISSP Digital Societies survey and Austria-specific questions. See the Methods section for details.

Figure 2. Online Trust (internet users only). Formulation of the question: “On a scale of 0 to 10, how much do you trust people you communicate with over the Internet but have never met in person? 0 means you have no trust at all, and 10 means you have complete trust.” Source: Austrian sample of the ISSP Digital Societies survey and Austria-specific questions. See the Methods section for details.

Table 3 presents the results of the regression analyses. As described in the methods section, the included variables were selected based on their significance when considering only a single theory approach. Model 1, on generalized offline trust, shows that trust in institutions—more specifically in Austrian courts—has the strongest effect with a Beta of 0.198. The feeling of control over life’s problems, related to the personality perspective, is also significant with a Beta of 0.173. In addition, variables related to societal status and the social constructivist view are significant, i.e., residency and household income. Education fails to be significant at a 0.05 level. All other variables are not significant in this model, hence, generalized trust is mostly influenced by factors related to the institutional, personality, as well as to the social status and social constructivist view.

Model 2 presents the results for online trust. Online trust is also shaped by institutional trust, in this case, trust in the Austrian parliament (Beta = 0.119). Compared to offline social trust, online trust is also influenced by other online trust indicators such as trust in the accuracy of social media (Beta = 0.134). Furthermore, sociodemographic characteristics, i.e., being young (Beta = 0.140), gender (−0.163), and belonging to a disadvantaged social group (0.082), are significant, which supports approaches considering social class and constructivist views. Furthermore, political bonding online (civic perspective) is significant (Beta = 0.116), as is being a victim of online harassment (reflecting experiential rational choice view) with a Beta of 0.098. The rational choice indicator of being a victim of online harassment has surprisingly a positive effect. A possible explanation is that the cause-and-effect direction might be reversed and trusting individuals might get in contact with perpetrators more often. Finally, similar to general trust, the issue with managing problems has a positive effect. Surprisingly, its effect is opposed to its empowering impact on generalized offline trust in the initial model. However, it shows that online trust is also influenced by personality factors. In sum, this first analysis of online trust suggests that online trust is influenced by factors associated with all approaches shown in Table 1.

To explore the relationship between online trust and generalized trust, we added the latter as an additional independent variable to Model 2. The results are shown in Model 3. The impact of sociodemographic characteristics—trusting more when young and male—remains significant. The phenomenon of political bonding also retains its relevance for online trust (Beta = 0.110)—a finding that supports the proposition that on the Internet, we may also be confronted with a distinct and more particularized dimension of trust, as engaging online with politically like-individuals results in higher trust. Factors related to social class/status, social constructivist views, and the civic perspective also remain strong. Similarly, the rational choice-related indicator and online harassment remain significant. A larger shift happens regarding trust indicators not related to the online sphere. Model 3 shows that generalized trust becomes the strongest predictor for online trust (Beta = 0.214), whereas trust in the institution “parliament” is not significant anymore. This finding supports the view that online trust is strongly related to generalized trust despite the mixed results in our initial descriptive analyses.

To verify these findings of Model 3, we estimated a similar regression with the international dataset. We included all significant indicators of Model 3 except for the difficulty managing problems indicator, which was not included in the pretest data, and added the trust in institutions indicator “parliament” and fixed effects for each country. This verifying regression confirms that generalized trust (Beta = 0.115**) has a stronger effect than institutional trust (Beta Parliament = 0.101**; Beta Social Media = 0.108**). Generalized offline trust, hence, is central to online trust, which is also underscored in another additional analysis, a factor analysis, which shows that online and offline trust and trust in a parliament form a single factor with generalized trust having the strongest loading.

The present research note explores the sources of online trust with a focus on generalized trust. The initial literature review showed that scholars addressing the sources of online trust (Beldad et al., 2010; Taddeo, 2010; Bouchillon, 2014; Antonijević and Gurak, 2019) also build on classic theories developed in an offline setting. Therefore, we presented six theoretical perspectives that highlight different sources of trust. The approaches include the personality perspective, associated with scholars such as Erikson (1950), Rosenberg (1956), Allport (1979), and Uslaner (2002, 2018), the civic culture and values perspective, studied by Almond and Verba (1963), Putnam (1993, 2000), Brehm and Rahn (1997), Fukuyama (1995), Paxton (2007), and Paxton and Ressler (2018), the rational choice perspective, as addressed by Gambetta (1988), Coleman (1990), Hardin (1993, 2002), and Cook and Santana (2018), the societal status/class perspective, associated with Patterson (1999), Wilkinson (2005), Rothstein and Uslaner (2005), and Dinesen and Sønderskov (2018), the institutional perspective, as discussed by Levi (1998), along with Rothstein and Stolle (2001, 2008), and, lastly, the social constructivist perspective covered by Larsen (2013) and Frederiksen (2019).

As for the relationship between offline and online trust, we considered two possibilities. The basic premise of generalized trust—the belief that “most people can be trusted” and that trust extends beyond personal interactions (Stolle, 2002; Uslaner, 2002)—suggests that online trust is a subset of it. However, research on offline trust was also able to differentiate between generalized and particularized trust (Freitag and Traunmüller, 2009), social and political trust (Newton and Zmerli, 2011), and transitions from particular to generalized trust (Glanville and Shi, 2020; Zheng et al., 2023), which also allows for the alternative view that offline and online trust are distinct concepts.

Using survey data from Austria and four other countries, we identified questions and items that relate to these six theoretical perspectives mentioned above and tested their effect on offline and online trust. In the separate models of offline and online trust, the institutional perspective emerged as the most influential theoretical approach, which is consistent with some recent experimental and cross-country trust research (Martinangeli et al., 2024; Domański and Pokropek, 2021). However, when adding generalized offline trust to the regressions on online trust, its effects are stronger than those of the institutional trust indicators. Furthermore, an additional factor analysis showed that online trust and generalized trust load were on the same dimension, whereas the loading of generalized trust load was stronger. These findings show that generalized offline trust is central to online trust. In this sense, these findings rather point to online trust as an extension of generalized trust than to an independent concept and suggest that the belief that “most people can be trusted” and that trust extends beyond personal interactions (Stolle, 2002; Uslaner, 2002) also applies to the link between an offline and an online environment.

In conclusion, this research note offers some first insights into the relationship between online and offline trust using the forthcoming ISSP “Digital Societies” survey. Yet, we face some limitations. At this point, we have data only for a few countries. Further, the questions asked in the survey, and the match between the indicators and the theories were not always perfect. Third, we relied on cross-sectional data, which precludes us from examining causality—such as whether trust in online contacts is a cause, effect, or both, of online harassment (or its absence). Future research could address these limitations by analyzing a broader range of countries, once the ISSP releases the full dataset with up to 45 countries in 2026, and exploring alternative datasets or methods, such as combining survey data with external indicators aligned with the theoretical frameworks.

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: Hadler et al. (2024) and Andreadis et al. (2024).

Ethical review and approval were not required for this study on human participants in accordance with local legislation and institutional requirements. Informed consent was obtained at the time of survey participation, in line with national legislation and institutional guidelines.

BV: Writing – original draft. RS: Writing – original draft. MH: Writing – original draft.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Data collection in Austria was funded by the Federal Ministry of Education, Science and Research under project number 2022-0.875.579, titled “Austria’s Participation in the International Social Survey Programme.” Additionally, funding for the publication of this work was provided by the University of Graz.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. For language editing purposes, OpenAI's ChatGPT Versions 3.5 and higher were used.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Almond, G. A., and Verba, S. (1963). The civic culture: Political attitudes and democracy in five nations. Princeton, New Jersey, USA: Princeton University Press.

Andreadis, I., Eder, A., Hadler, M., Labucay, I., Penker, M., Sandoval, G., et al. (2024). Pretest data for the ISSP digital societies module. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.15012899

Antonijević, S., and Gurak, L. (2019). The internet: a brief history based on trust. Sociologija 61, 464–477. doi: 10.2298/SOC1904464A

Barbalet, J. (2019). “The experience of trust: its content and basis” in Trust in Contemporary Society. ed. M. Sasaki (Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill), 11–30.

Bauer, P. C., and Freitag, M. (2018). “Measuring trust” in The Oxford handbook of social and political trust. ed. E. Uslaner (Oxford University Press), 17–37.

Beldad, A., de Jong, M., and Steehouder, M. (2010). How shall I trust the faceless and the intangible? A literature review on the antecedents of online trust. Comput. Hum. Behav. 26, 857–869. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.013

Bouchillon, B. C. (2014). Social ties and generalized trust, online and in person: contact or conflict - the mediating role of bonding social Capital in America. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 32, 506–523. doi: 10.1177/0894439313513076

Brehm, J., and Rahn, W. (1997). Individual-level evidence for the causes and consequences of social capital. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 41, 999–1023. doi: 10.2307/2111684

Chen, W., Shen, C., and Huang, G. (2016). In game we trust? Coplay and generalized trust in and beyond a Chinese MMOG world. Inf. Commun. Soc. 19, 639–654. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2016.1139612

Coleman, J. S. (1990). Foundations of social theory. Cambridge, Mass., USA: Harvard University Press.

Cook, K. S., and Santana, J. J. (2018). “Trust and rational choice” in The Oxford handbook of social and political trust. ed. E. Uslaner (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press), 253–278.

Delhey, J., and Newton, K. (2003). Who trusts? The origins of social trust in seven societies. Eur. Soc. 5, 93–137. doi: 10.1080/1461669032000072256

Delhey, J., and Newton, K. (2005). Predicting cross-national levels of social trust: global pattern or Nordic exceptionalism? Eur. Sociol. Rev. 21, 311–327. doi: 10.1093/esr/jci022

Delhey, J., Newton, K., and Welzel, C. (2011). How general is trust in “Most people”? Solving the radius of trust problem. Am. Sociol. Rev. 76, 786–807. doi: 10.1177/0003122411420817

Deutsch, M. (1958). Trust and suspicion. J. Confl. Resolut. 2, 265–279. doi: 10.1177/002200275800200401

Dinesen, P. T., and Sønderskov, K. M. (2018). “Cultural persistence or experiential adaptation? A review of studies using immigrants to examine the roots of trust” in The Oxford handbook of social and political trust. ed. E. Uslaner (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press), 205–229.

Domański, H., and Pokropek, A. (2021). The relation between interpersonal and institutional Trust in European Countries: which came first? Polish Sociol. Rev. 1, 87–102. doi: 10.26412/psr213.05

Earle, T. C., and Cvetkovich, G. T. (1995). Social trust: Toward a cosmopolitan society. Westport, Conn., USA: Praeger.

Fairbrother, M., Penker, M., and Hadler, M. (2024). Trust, social movements, and the state. J. Trust Res. 14, 157–187. doi: 10.1080/21515581.2024.2391385

Frederiksen, M. (2019). On the inside of generalized trust: trust dispositions as perceptions of self and others. Curr. Sociol. 67, 3–26. doi: 10.1177/0011392118792047

Freitag, M., and Traunmüller, R. (2009). Spheres of trust: an empirical analysis of the foundations of particularized and generalized trust. Eur J Polit Res 48, 782–803. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2009.00849.x

Fukuyama, F. (1995). Trust: The social virtues and the creation of prosperity. New York, USA: The Free Press.

Gambetta, D. (1988). “Can we trust trust?” in Trust: Making and breaking cooperative relations. ed. D. Gambetta (Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell).

Glanville, J. L., and Shi, Q. (2020). The extension of particularized trust to generalized and out-group trust: the constraining role of collectivism. Soc. Forces 98, 1801–1828. doi: 10.1093/sf/soz114

Green, M. C. (2007). “Trust and social interaction on the internet” in The Oxford handbook of internet psychology. eds. A. N. Joinson, K. Y. A. McKenna, T. Postmes, and U. Reips (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press), 43–52.

Hadler, M., Eder, A., Penker, M., Aschauer, W., Prandner, D., Bacher, J., et al. (2024). Social survey Austria 2024 (SUF edition). doi: 10.11587/0VKC5X

Hadler, M., Gundl, F., and Vrečar, B. (2020). The ISSP 2017 survey on social networks and social resources: an overview of country-level results. Int. J. Sociol. 50, 87–102. doi: 10.1080/00207659.2020.1712048

Hardin, R. (1993). The street-level epistemology of trust. Polit. Soc. 21, 505–529. doi: 10.1177/0032329293021004006

Hergueux, J., Algan, Y., Benkler, Y., and Fuster-Morell, M (2021). “Do I trust this stranger?” n Generalized Trust and the Governance of Online Communities, Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2021. pp. 539–543.

Khopkar, T., and Resnick, P. (2009). “In the eye of the beholder: culture, trust and reputation systems” in eTrust: Forming relationships in the online world. eds. K. S. Cook, C. Snijders, V. Buskens, and C. Cheshire (New York, USA: Russell Sage Foundation), 109–135.

Larsen, C. A. (2013). The rise and fall of social cohesion: The construction and deconstruction of social trust in the US, UK, Sweden, and Denmark. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Levi, M. (1998). “A state of trust” in Trust and governance. eds. V. Braithwaite and M. Levi (New York, USA: Russell Sage Foundation), 77–101.

Lewis, J. D., and Weigert, A. (1985). Trust as a social reality. Soc. Forces 63, 967–985. doi: 10.2307/2578601

Lundmark, S. (2015). Gaming together: when an imaginary world affects generalized trust. J. Inform. Tech. Polit. 12, 54–73. doi: 10.1080/19331681.2014.972602

Martinangeli, A. F. M., Povitkina, M., Jagers, S., and Rothstein, B. (2024). Institutional quality causes generalized trust: experimental evidence on trusting under the shadow of doubt. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 68, 972–987. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12780

Misztal, B. A. (2020). “Trust and the variety of its bases” in Cambridge handbook of social theory, volume II: Contemporary theories and issues. ed. P. Kivisto (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), 333–353.

Möllering, G. (2005). Understanding of trust from the perspective of sociological Neoinstitutionalism. Discussion Paper: Max Planck Institut für Gesellschaftsforschung.

Mutz, D. C. (2005). Social trust and e-commerce: experimental evidence for the effects of social trust on individual’s economic behavior. Public Opin. Q. 69, 393–416. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfi029

Nannestad, P. (2008). What have we learned about generalized trust, if anything? Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 11, 413–436. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.060606.135412

Näsi, M., Räsänen, P., Hawdon, J., Holkeri, E., and Oksanen, A. (2015). Exposure to online hate material and social trust among finnish youth. Inf. Technol. People 28, 607–622. doi: 10.1108/ITP-09-2014-0198

Näsi, M., Räsänen, P., Keipi, T., and Oksanen, A. (2017). Trust and victimization: a cross-national comparison of Finland, the U.S., Germany and UK. Res. Finn. Soc. 10, 119–131. doi: 10.51815/fjsr.110771

Newton, K., Stolle, D., and Zmerli, S. (2018). “Social and political trust” in The Oxford handbook of social and political trust. ed. E. M. Uslaner (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press), 37–56.

Newton, K., and Zmerli, S. (2011). Three forms of trust and their associations. Eur. Polit. Sci. Rev. 3, 169–200. doi: 10.1017/S1755773910000330

Patterson, O. (1999). “Liberty against the democratic state: on the historical and contemporary sources of American distrust” in Democracy and trust. ed. M. E. Warren (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), 161–207.

Pavić, Ž., and Šundalić, A. (2016). A comparison of online and offline social participation impacts on generalized trust. Italian Sociol. Rev. 6, 185–203. doi: 10.13136/isr.v6i2.131

Paxton, P. (2007). Association memberships and generalized trust: a multilevel model across 31 countries. Soc. Forces 86, 47–76. doi: 10.1353/sof.2007.0107

Paxton, P., and Ressler, R. W. (2018). “Trust and participation in associations” in The Oxford handbook of social and political trust. ed. E. Uslaner (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press), 149–172.

Putnam, R. D. (1993). Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton, New Jersey, USA: Princeton University Press.

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York, USA: Simon & Schuster.

Rahn, W. M., and Transue, J. E. (1998). Social trust and value change - the decline of social Capital in American Youth, 1976-1995. Polit. Psychol. 19, 545–565. doi: 10.1111/0162-895X.00117

Reeskens, T., and Hooghe, M. (2008). Cross-cultural measurement equivalence of generalized trust. evidence from the European social survey (2002 and 2004). Soc. Indic. Res. 85, 515–532. doi: 10.1007/s11205-007-9100-z

Robbins, B. G. (2016). What is trust? A multidisciplinary review, critique, and synthesis. Sociol. Compass 10, 972–986. doi: 10.1111/soc4.12391

Rosenberg, M. (1956). Misanthropy and political ideology. Am. Sociol. Rev. 21, 690–695. doi: 10.2307/2088419

Rothstein, B., and Stolle, D. (2001). “Social Capital and street-level bureaucracy: an institutional theory of generalized trust.” in Conference paper, Center for the Study of Democratic Politics, Princeton University.

Rothstein, B., and Stolle, D. (2008). The state and social capital - the institutional theory of generalized trust. Comp. Polit. 40, 441–459. doi: 10.5129/001041508X12911362383354

Rothstein, B., and Uslaner, E. M. (2005). All for all: equality, corruption and social trust. World Polit. 58, 41–72. doi: 10.1353/wp.2006.0022

Schilke, O., Reimann, M., and Cook, K. S. (2021). Trust in Social Relations. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 47, 239–259. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-082120-082850

Stolle, D. (2002). Trusting strangers - the concept of generalized Trust in Perspective. Österreichische Zeitschrift Politikwissenschaft 31, 397–412. doi: 10.15203/ozp.814.vol31iss4

Taddeo, M. (2010). Modelling Trust in Artificial Agents, a first step toward the analysis of e-trust. Mind. Mach. 20, 243–257. doi: 10.1007/s11023-010-9201-3

Uslaner, E. M. (2004). Trust, civic engagement, and the internet. Polit. Commun. 21, 223–242. doi: 10.1080/10584600490443895

Uslaner, E. M. (2018). “The study of trust” in The Oxford handbook of social and political trust. ed. E. M. Uslaner (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press), 3–14.

Vrečar, B. (2025). Perspectives on trust: Towards a historical mapping of the concept and its dimensions. Social Sciences. 14:77. doi: 10.3390/socsci14020077

Wang, Y. D., and Emurian, H. H. (2005). An overview of online trust: concepts, elements and implications. Comput. Hum. Behav. 21, 105–125. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2003.11.008

Wilkinson, R. G. (2005). The impact of inequality: How to make sick societies healthier. New York, USA: The New Press.

Yamagishi, M., and Yamagishi, T. (1994). Trust and commitment in the United States and Japan. Motiv. Emot. 18, 129–166. doi: 10.1007/BF02249397

Yoon, S. J. (2002). The antecedents and consequences of Trust in Online-Purchase Decisions. J. Interact. Mark. 16, 47–63. doi: 10.1002/dir.10008

Zheng, J., Wang, T. Y., and Zhang, T. (2023). The extension of particularized trust to generalized trust: the moderating role of long-term versus short-term orientation. Soc. Indic. Res. 166, 269–298. doi: 10.1007/s11205-023-03064-2

Keywords: generalized trust, online trust, institutional trust, internet users, ISSP, digital societies

Citation: Hadler M, Vrečar B and Schaffer R (2025) Generalized trust as a foundation for online trust: findings from Austria, Greece, Poland, the Philippines, and South Africa. Front. Sociol. 10:1504812. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2025.1504812

Received: 01 October 2024; Accepted: 07 March 2025;

Published: 07 April 2025.

Edited by:

John Owen, University of Virginia, United StatesReviewed by:

Maria Paola Faggiano, Sapienza University of Rome, ItalyCopyright © 2025 Hadler, Vrečar and Schaffer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Markus Hadler, bWFya3VzLmhhZGxlckB1bmktZ3Jhei5hdA==

†ORCID: Markus Hadler, orcid.org/0000-0002-0359-5789

Rebecca Schaffer, orcid.org/0009-0002-7513-0486

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.