- Department of Geography and Rural Planning, Faculty of Geographical Sciences, Kharazmi University, Tehran, Iran

Introduction: Since the enactment of the Law of Comprehensive Structure for Social Welfare and Security in Iran, only a small fraction of its target has been accomplished and a significant part of rural women have not been covered by the social insurance service yet. A few studies have been conducted on the social insurance of rural people. However, no study has ever addressed the issue of women with a focus on the theoretical aspects of sociology science, which is the contribution of the present research. Therefore, the present research aimed to explore the barriers to rural women’s participation in social insurance.

Methods: The research adopted a qualitative approach and the grounded theory method. It was conducted among the brokers of social insurance for farmers, villagers, and nomads in Iran. Data were collected through interviews.

Results and Discussion: The results showed that the barriers to women’s participation in social insurance were economic (e.g., women’s economic dependence on the family head), social (e.g., low social trust, low literacy and awareness of rural women, and limitations imposed by religious doctrine), cultural (e.g., limited social communications, limited use of technology, and poor insurance culture), legal (e.g., poor legal support for rural women’s insurance and non-satisfaction of expectations from the fund services), and institutional (e.g., inefficient advertisement methods and poor awareness-raising measures).

1 Introduction

In the contemporary world, women, who constitute half of the world population, have a highly important role in developmental programs, and their active participation in all economic, social, cultural, political, environmental, and family contexts guarantees the success of the schemes and programs (Izadi et al., 2019; Jamshidi et al., 2024). So, societies have tried to expand their cooperation in social, economic, cultural, political, and family affairs, increase their share in decision levels and the implementation of development programs (Moradhaseli et al., 2019; Naderi et al., 2024), and create conditions for their flourishing in various aspects by identifying and resolving the barriers to their extensive presence and participation (Shu, 2018; Evangelakaki et al., 2020; Anabestani et al., 2024; Aliabadi et al., 2024).

There are numerous important impediments implicated in women’s low or lack of participation in development programs in different societies (Inneh et al., 2024; Samad et al., 2024), e.g., the social status of women in society, their social awareness (Vu et al., 2024; El Dessouky, 2023), cultural values (such as traditions, customs, values, and social norms), religious and people’s insights, literacy level, cultural pressures (e.g., honor, fidelity, and gratitude to parents) (Sasikumar and Sujatha, 2024), and the dominance of patriarchism (Fan et al., 2021; Giles et al., 2021; Green et al., 2021). Women’s value orientation is a factor that influences their social cooperation. In this regard, family, patterns in the social environment (such as the participation of their members) (Ataei et al., 2021), and awareness of facilities that exist in the living environment are important variables underpinning women’s participation (Gui, 2018; Ataei et al., 2023b; Anbari et al., 2024). Besides social, cultural, and identity issues, women’s economic conditions and features influence the sort and extent of their participation (Liu et al., 2018; Yang, 2018).

Unemployment, elderliness, and incidents are issues that threaten women’s lives more than men’s lives. Women are more vulnerable in rural areas than in urban areas (Wu and Xiao, 2018; Ma and Oshio, 2020; Gholamrezai et al., 2021), so the significance of the social welfare and security system and support insurance system has drawn attention to filling the gaps and covering the likely future risks (Aazami et al., 2019; Moradhaseli et al., 2021). In Iran, given the importance put on the comprehensive system of social welfare and security, Article 29 of the Constitution and Article 96 of the Fourth and Fifth Economic, Social, and Cultural Development Plans have emphasized the implementation of social insurance across rural areas. Social insurance in most countries has been extended to rural areas, targeting both women and men similarly. Social insurance is a major instrument to ensure the security of women’s future and can play a key role in improving their socio-economic status by reducing their poverty and financial dependence. This will happen if women are actively involved in insurance to enjoy this facility.

The Social Insurance Fund of Farmers, Villagers, and Nomads of Iran (SIF) was founded in 2005 and has been active since then. It is voluntary to apply for insurance in SIF, and SIF covers all people in the target community including women and men for its services. People in the age range of 18–50 years can become a member of SIF. Three main services provided for the social insurance of farmers and villagers include elderly insurance (retirement), disability insurance, and life insurance (survivor annuity). This insurance system in Iran is chiefly characterized by the advantage that the government pays 66.7 percent of the insurance premium and the policyholders only pay 33.3 percent, or one-third, of the premium. In other words, the government pays a subsidy of two-thirds of the premium to the policyholders of SIF. Despite this advantage, evidence shows the low participation of women in this fund. According to the latest statistics on SIF, this fund had 1,776,017 members by 2019 out of whom 81 percent (1,439,003 people) were male and the remaining 19 percent (337,016 people) were female. The latest general census of Iran in 2016 shows that the number of rural males and females was 10,630,549 and 10,100,076, respectively. The comparison of these two figures reveals that since the enactment of the Law of Comprehensive Structure for Social Welfare and Security in 2004, only a small fraction of its target has been accomplished and a significant part of rural women are not covered by the social insurance service yet. Similarly, research on poverty shows that women have a greater share of poverty than men, and rural women are more exposed to poverty than urban women (Obadha et al., 2020; Xie et al., 2021; Peng and Ling, 2019; Vaez Roudbari et al., 2024). Although women play important roles in production, family, and diverse activities that they do, they enjoy lower revenue sources. Iran is not an exception and women in its rural areas have lower economic resources despite their participation in agricultural and homemaking activities (Moradhaseli et al., 2017; Ghadermarzi et al., 2022, 2023; Ataei et al., 2023a). Therefore, rural communities in general and rural women in particular are in more urgent need of social insurance and its expansion. The expansion of social insurance across rural communities needs the identification of the reasons and solutions and the proposition of executive courses of action. This, in turn, needs to precisely identify all aspects of the issue and make plans based on scientific findings.

A few studies have been conducted on the social insurance of rural people and yet no study has ever addressed the issue of women with a focus on the theoretical aspects of participation, which is the contribution of the present research. It may be hoped that the results of this study and the recent interest shown by social insurance in the sociological approach is more than a flash in the pan and that a new survey of the subject in a few years will lead to a more positive evaluation of the contribution of sociology. Both sociologists and social insurance practitioners can contribute to this development and benefit from it using the results of this study. The contribution of sociologists should be to undertake more impactful studies, which requires improved knowledge of the user of social insurance and a better definition of the concept of social “insecurity” in order to be able to isolate the effects of social security programs and assess them more accurately in the rural areas. Rural women can be helped to better enjoy the legal capacities of insurance supply by recognizing the barriers to their participation in social insurance and thinking about solutions for tackling them. Finally, by adopting these solutions, SIF, which is the organization in charge of providing insurance in rural areas, can successfully accomplish its mission set by the upstream documents, i.e., the expansion of insurance across all regions. Therefore, the question arises, what are the obstacles to women’s participation in the social insurance of farmers, villagers, and nomads? This research question will be answered in the Results section. The results can be applied in the field of women by SIF officials and planners, the Ministry of Cooperatives, Labor, and Social Welfare, and rural development planners in developing countries.

2 Literature review

Ghadermazi et al. (2021) researched the factors affecting the effectiveness of social insurance for farmers, villagers, and nomads in the rural areas of Kurdistan province, Iran. They consider social insurance a part of the social support system for rural people in Iran that pursues such goals as alleviating deprivation and poverty, establishing social justice, and ensuring public welfare. The results show that socioeconomic factors are more influential on rural people’s social insurance than cultural and geographical factors. Varmazyari and Moradi (2017) explored the barriers to the development of social insurance for farmers, villagers, and nomads and proposed five categories of structural, executive, economic, socio-cultural, and motivational barriers. Rezvani and Azizi (2013) studied the challenges of SIF in interviews with some insurance experts in which the barriers to the expansion of social insurance among rural people and nomads were divided into two categories. One category included structural and legal factors, e.g., regulations and lack of proper advertisement, and the other was related to the status of the rural community including distrust in insurance agents, unawareness of insurance, and insurers’ economic inability to pay the insurance premium, especially in less-developed regions.

Shafieezadeh et al. (2013) studied the factors influencing the institutionalization of social insurance in rural areas and categorized them into three groups: cognitive-normative factors, cultural-social factors, and regulatory factors. In a study on the factors affecting farmers’ adoption of social insurance, Sharifi and Hosseini (2009) conclude that the adoption of social insurance is influenced by such factors as the household economic potential, farmers’ lack of trust, household human capital, rural development level, and following others. In a study on the barriers to rural social insurance, classified 11 key concepts as the main problems of rural insurance development among villagers and nomads. They include socio-economic issues, structural-infrastructural issues, motivational-incentive issues, lack of institutional coordination, advertisement and awareness-raising, managerial-executive issues, lack of human resources, professional ethics, and financial-credit issues. Javanmard et al. (2019) discuss that social status, prudence, social trust, social insurance quality, and knowledge and awareness level are effective in rural people’s participation in social insurance.

In a study on the problems of the rural social security system in China and solutions for them, Chen and Yang (2014) reveal that the rural social security system of China has a vital strategy for agricultural development and it has prominent achievements after decades of endeavor. However, there are problems like limited social security coverage due to financial shortages and the government tries to settle them by increasing investment, creating united social security management, emphasizing rural social security, adopting advertisement measures, and completing supervision of the system. In a study in Indonesia, Angelini and Hiros (2004) reported that the weakness of production resources was the main reason for the non-adoption of insurance in the informal economy, and this factor along with the low level of literacy and non-farming skills had limited the expansion of insurance among landless farmers, farmers with limited lands, fishers, marginal users, and women in rural areas. According to this research, the lack of trust between governmental and non-governmental institutions, insurance agents, and farmers was mutual and the reluctance of both parties had led to their low participation. This reluctance as a norm had a negative impact on farmers’ adoption of social insurance. Ramesh (2007) and Yari et al. (2024) specified some barriers to the expansion of social insurance in developing countries. They include villagers’ lack of awareness about rural insurance status and benefits, the limitation of insurance benefits to some specific cases, the focus of insurance agents and firms on urban areas, and the lack of institutional innovation for rural people’s needs, which are different from the urban sector in nature.

Anderson (2001) states that social insurance for farmers is an innovation whose adoption by the target community needs to go through specific steps. He argues that the philosophy of social insurance and its benefits for society requires that the government provides the requirements and support for its adoption by farmers. Akwaowo et al. (2021) and Moradhaseli et al. (2018) argue that social insurance is mainly focused on urban areas and has been neglected in rural areas. Insurance companies adopt various marketing strategies, but their penetration is still lower in rural areas than in urban areas. Bairoliya and Miller (2021) studied the penetration of rural insurance and the reasons for the poor performance of insurance firms and found that the insurance sector was developed in India but it still covered rural areas poorly. The reasons for the low popularity of insurance can be enumerated as unawareness, lack of motivation, and lack of timely payment of indemnity. Bairoliya and Miller (2021), Fan et al. (2021), and Hajrasouliha and Shahgholi Ghahfarokhi (2021) concluded that institutional and legal challenges have hindered the development of social insurance in rural areas in many countries.

The literature review revealed that various factors and components can affect the participation of people in social insurance. These factors may vary with the socio-cultural context of each region and community. Also, most researchers have not provided categories of factors and have examined components separately. If these factors are extracted more comprehensively with different subcategories, a broader perspective for social insurance services will be provided in rural areas.

3 Methodology

The research is an applied study in terms of goal and a qualitative study in terms of approach. The statistical population was composed of all brokers of the Social Insurance Fund of Farmers, Villagers, and Nomads (SIF) in 31 provinces of Iran (1,800 brokers). The sample whose size was determined at 317 brokers by Cochran’s formula was taken by the stratified random sampling technique. To distribute the representatives, the proportion of the sample size to the total number of brokers was first determined for each province. Then, a sample was taken from each county considering the geographically proportional distribution of the samples. When the number of representative brokers in a province was fewer than that of its counties, the samples were taken from more populated counties. If the representative brokers of a province outnumber the number of province counties, more than one representative was selected from more populated counties considering the geographical distance of the populated counties from one another.

The research adopted Grounded Theory. Ground Theory refers to what is induced from the study of a phenomenon and represents that phenomenon. In other words, it must be discovered, completed, and proven experimentally by regular collection and analysis of data rooted in the phenomenon. So, data collection and analysis are in a mutual relationship (Bryant, 2020; Khosravi and Amjadian, 2024). The method uses an inductive approach, i.e., going from the specific to the general. With this approach, the researcher shapes a theory by identifying its components. The theory derived from this strategy is closer to real-world facts (Scholes, 2020). The reason for the adoption of this method is that there is no significant research literature available on the barriers to rural women’s participation in social insurance. In addition, to gain an in-depth and all-inclusive understanding of the issue, it seemed necessary to use a method that could provide a comprehensive picture of the participants. So, we employed Grounded Theory as the base method of the research.

The executive steps of Grounded Theory in the research include theoretical sampling, data collection, coding, and data analysis, which was initiated concurrent with the other steps and continued until theoretical saturation. The data were collected through in-depth interviews and using an open-ended questionnaire as the research instrument. The interviews could not be conducted face-to-face due to the COVID-19 pandemic, so they were carried out by telephone. First, the phone numbers of the brokers were collected in each province, and then, the selected brokers were contacted to be invited for telephone interviews. During the phone conversation, the brokers’ responses were jotted carefully.

The data were coded through three steps: open coding, axial coding, and selective coding. In the open coding step, after the main sentences were extracted, the similar meaning components were specified, and then, a code was assigned for each main and core code. In the next step, i.e., concentrated coding, which is the second step of open coding and aims to compare the codes to recognize similar and overlapped codes, the researcher arranged the codes or concepts and integrated similar and common codes within a united category. So, the plenty of data (codes and concepts) were reduced to a certain number of main categories. Before axial coding, the experts and some participants were requested to review the categories and sub-categories derived from open coding to specify if there were any irrational categories. The participants confirmed all categories and sub-categories. In the selective coding step, the relationships of the categories derived from the axial coding step were first specified for which rural women’s participation in social insurance was regarded as the core phenomenon. After the relationships of the identified factors with the core category were specified, the conceptual framework of the research was developed. To ensure reliability, the techniques of triangulation, long-term engagement with data, selection of proper meaning unit, selection of the amount of data required, and the use of quotations and narrations from the jotted text were employed. The research adopted two methods for triangulation. First, it was tried to select people who had different views on the issue at hand. Second, the data were collected by different methods so that they could give their opinions in different conditions. For example, the in-depth interview was conducted individually so that the participants were in different conditions and it was ensured that the environmental conditions or external factors would not influence the results. Finally, the model was provided to several experts to ensure that the results matched the reality.

4 Results

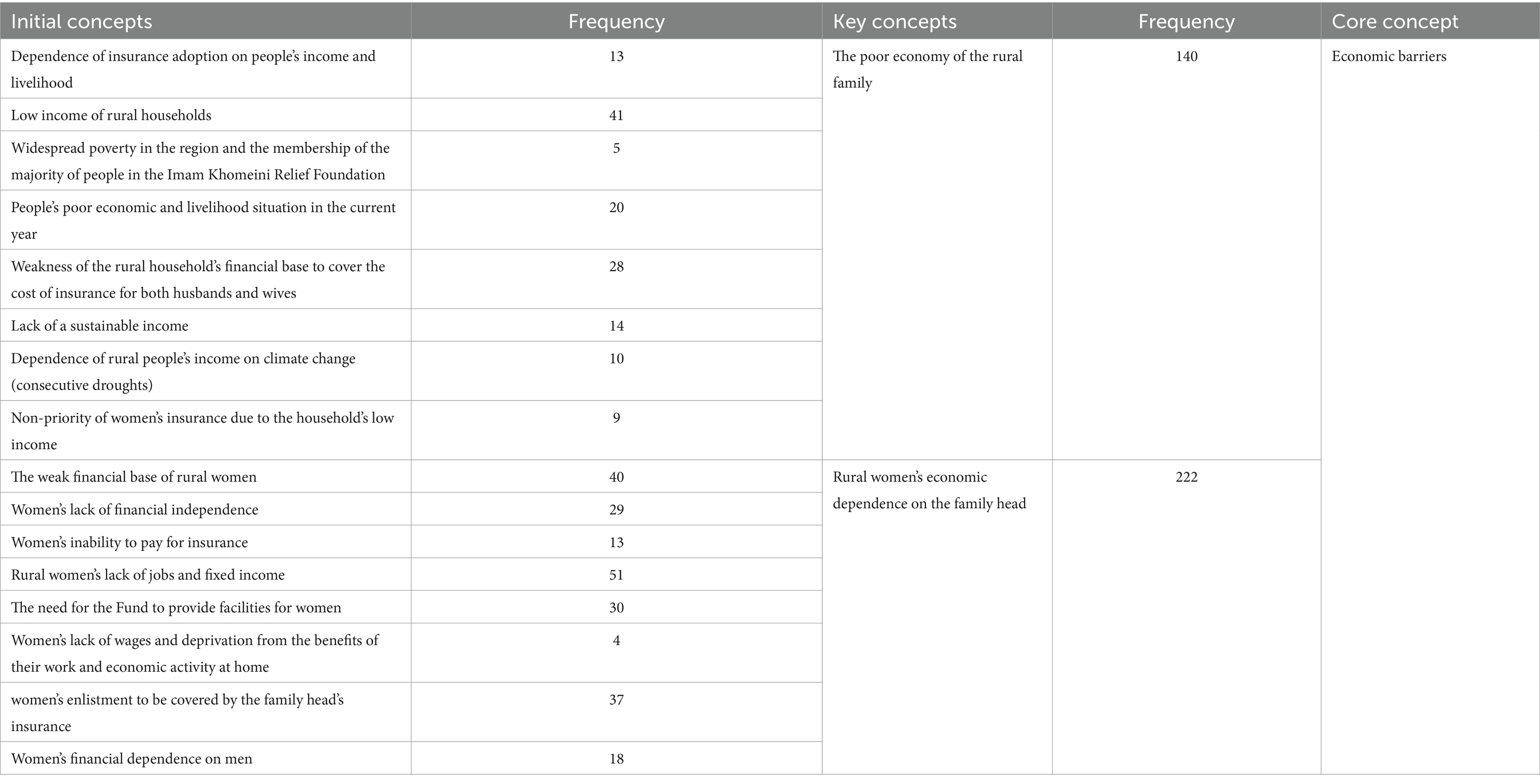

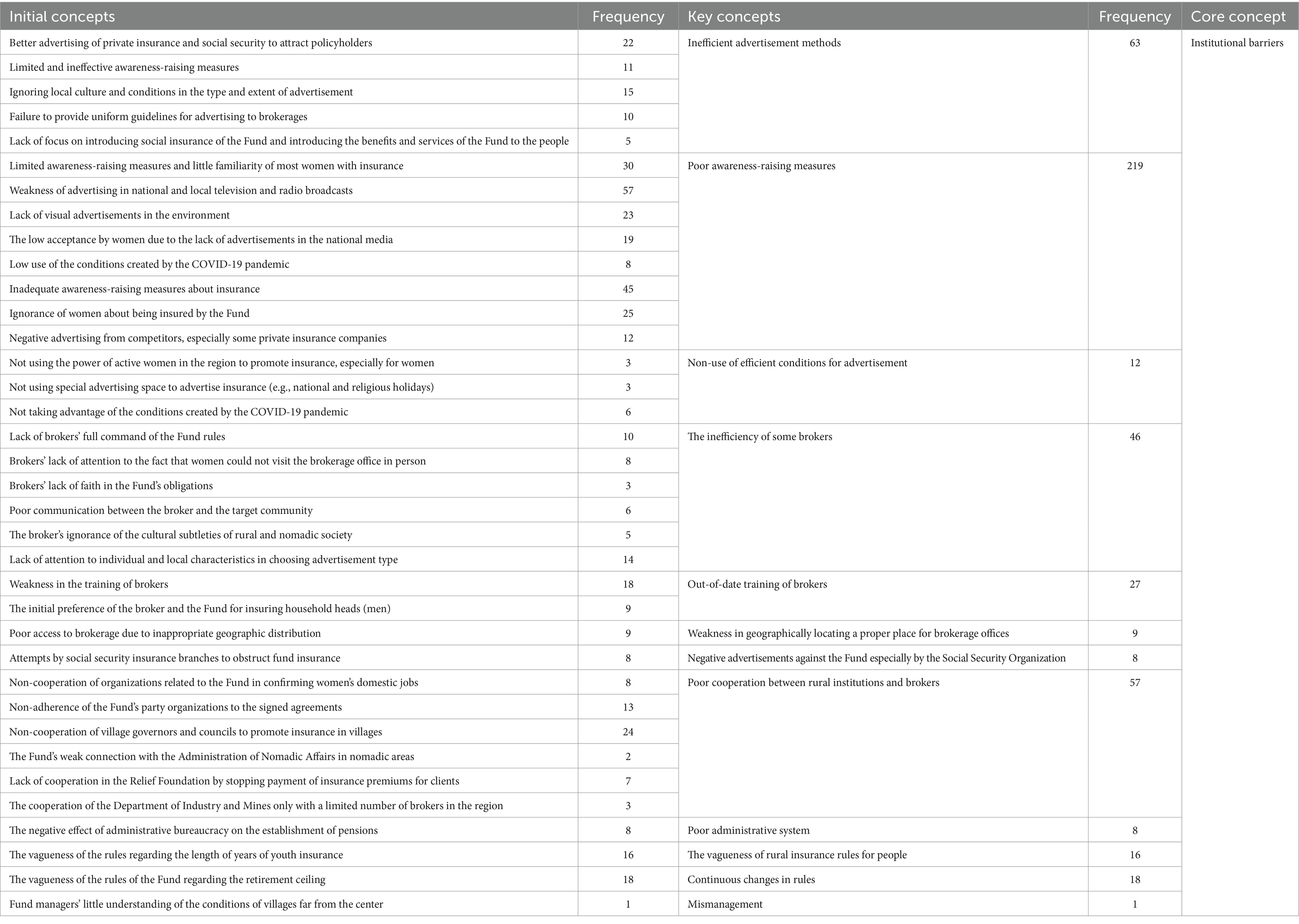

After the data were subjected to open coding, 118 initial concepts were extracted and 28 key concepts were identified about the research topic. In the open coding step, the full texts of the interviews were checked individually to extract the initial concepts. In the axial coding step, the initial concepts derived from each interview were compared to those of the other interviews, and the key concepts were integrated. In the selective coding step, the key concepts and their dimensions were specified and finally, the core concepts were obtained. They included economic, social, cultural, legal, and institutional concepts. In other words, in response to the research question, what are the obstacles to women’s participation in the social insurance of farmers, villagers, and nomads, it should be acknowledged that the barriers to their participation in the social insurance of farmers, villagers, and nomads were categorized within five core concepts (economic, social, cultural, legal, and institutional obstacles) (Figure 1).

4.1 Economic barriers

Although rural women have always been a significant part of the workforce and production in rural communities and have been involved in the household’s economic activities, which are mainly related to crop and animal farming, in various forms, their economic activity has been regarded as a part of family labor with no direct wage payment by the family head. This has limited their economic capacity to invest and spend money.

As is evident in Table 1, rural women’s non-participation in social insurance is a function of their economic dependence on the family head (a frequency of 222) and the weak economy of rural families (a frequency of 14). These factors influence one another as rural families in Iran are mainly at the lower income deciles. “Rural women’s lack of job and fixed income,” “weak financial base of rural women,” and “women’s enlistment to be covered by the family head’s insurance” were the main concepts in the category of “women’s economic dependence on the family head.” Also, the three categories of “low income of rural households,” “weakness of the rural household’s financial base to cover the cost of insurance for both husbands and wives,” and “people’s poor economic and livelihood situation in the current year” had the highest impact on the core category of “the poor economy of the rural family” as the frequencies showed.

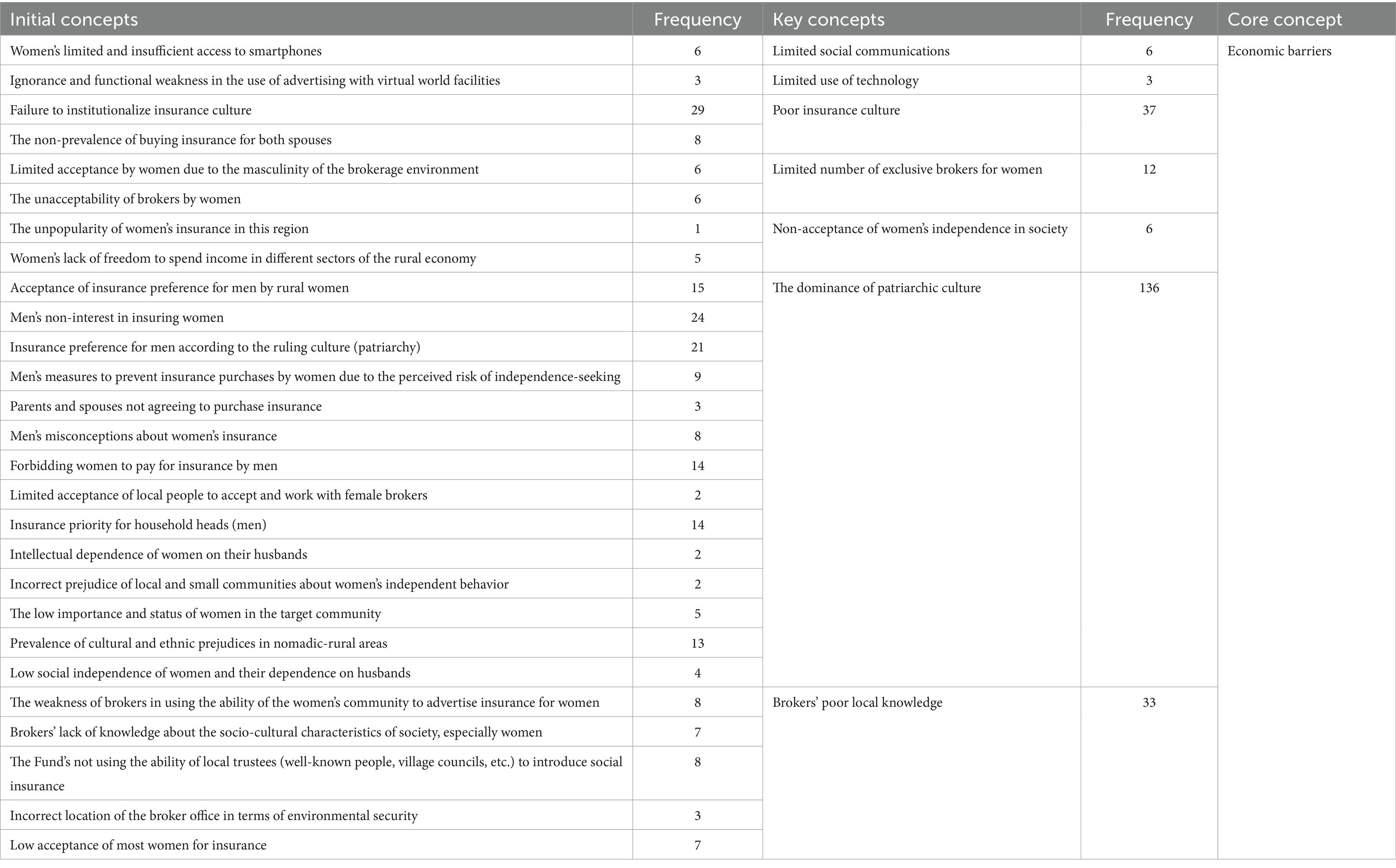

4.2 Cultural barriers

The cultural barriers to rural women’s non-participation in social insurance are a function of limited social communications, limited use of technology, poor insurance culture, limited number of exclusive brokers for women, non-acceptance of women’s independence in society, the dominance of patriarchic culture, and the brokers’ poor local knowledge. The most important cultural barrier to rural women’s participation in social insurance is the dominance of patriarchic culture. This key concept is composed of 14 initial concepts, the most important ones being “men’s non-interest in insuring women,” “insurance preference for men according to the ruling culture (patriarchy),” and “acceptance of insurance preference for men by rural women.” Other findings are presented in Table 2.

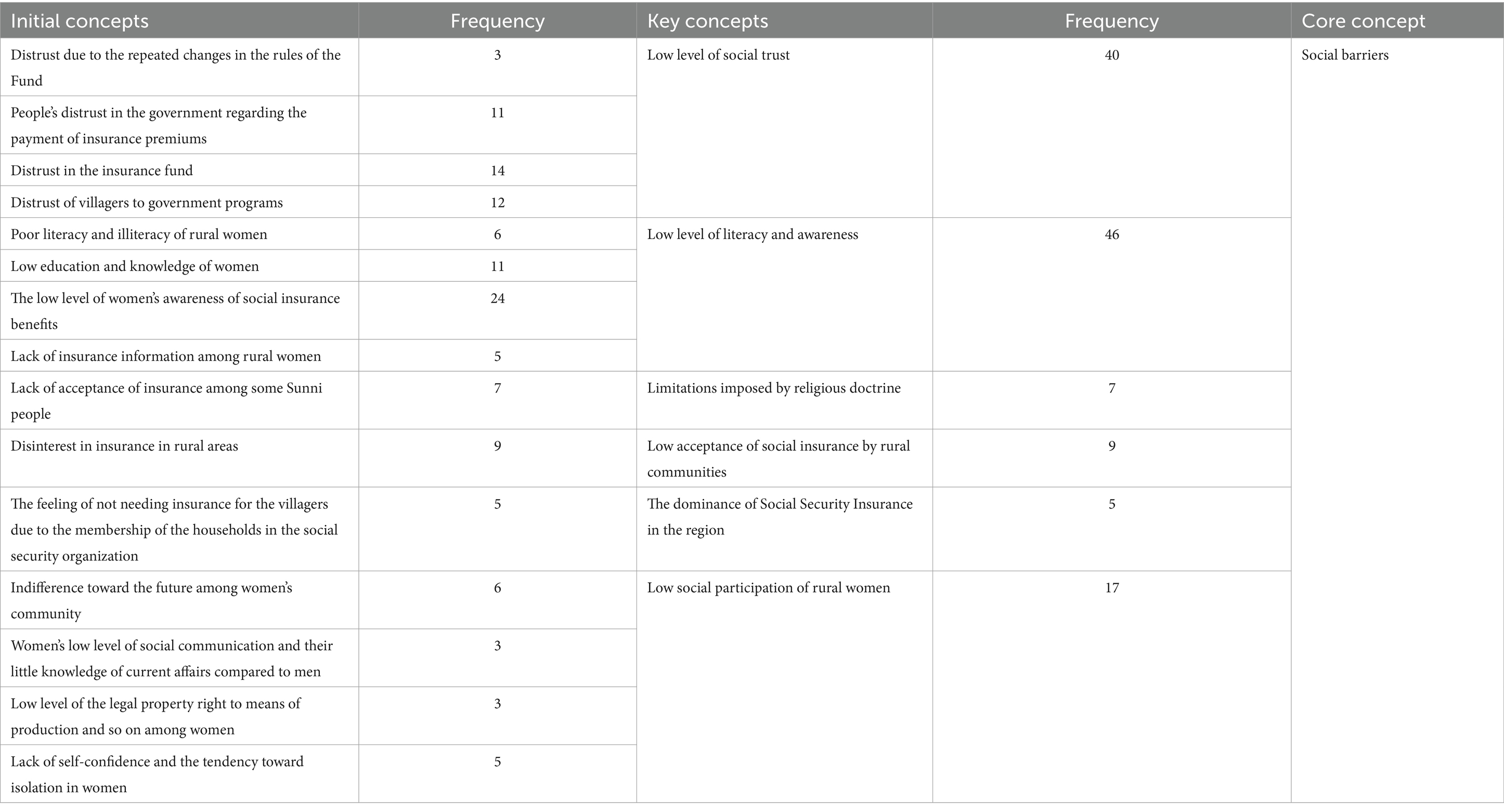

4.3 Social barriers

Based on the results, the social barriers to rural women’s participation in social insurance include low social trust, literacy, and awareness of rural women, limitations imposed by religious doctrine, low acceptance of social insurance by rural communities, the dominance of Social Security Insurance in the region, and low social participation of rural women. The key factor of low literacy and awareness was most strongly influenced by “the low level of women’s awareness of social insurance benefits” (a frequency of 24). Likewise, the key factor of low level of social trust was most strongly influenced by the initial factors of “distrust in the Social Insurance Fund of Farmers and Nomads” and “distrust of villagers to government programs,” respectively (Table 3).

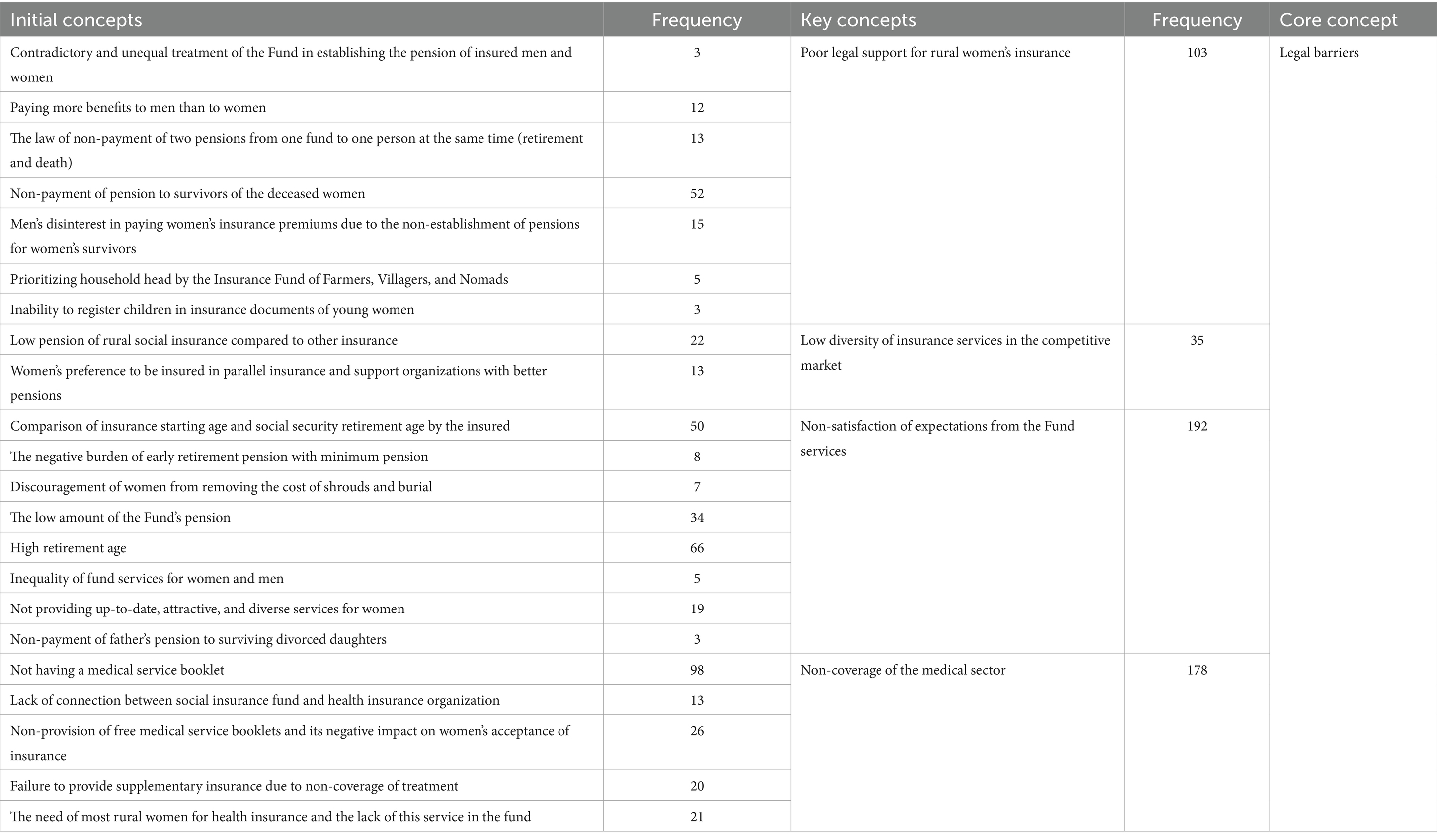

4.4 Legal barriers

According to Table 4, the legal barriers to women’s non-participation in social insurance are a function of the key concepts of non-satisfaction of expectations from the Fund services (a frequency of 192), non-coverage of the medical sector (a frequency of 178), poor legal support for rural women’s insurance (a frequency of 103), and low diversity of insurance services in the competitive market (a frequency of 35). These challenges in the legal dimension have prevented the Fund from achieving its main goals in developing rural women’s social insurance and have been a source of dissatisfaction. The key factor of non-satisfaction with expectations from the Fund services has been most strongly affected by the concepts of “high retirement age” and “the low amount of the Fund’s pension.” The initial concept of “not having a medical service booklet” was the most important factor for the non-coverage of the medical services. The main factor involved in the poor legal support of rural women’s insurance was “non-payment of pension to survivors of the deceased women.”

4.5 Institutional barriers

Some weaknesses identified in the research are related to the institutional structure of SIF. As is observed in Table 5, the institutional barriers to rural women’s participation include inefficient advertisement methods, poor awareness-raising measures, non-use of efficient conditions for advertisement, the inefficiency of some brokers, out-of-date training of brokers, weakness in geographically locating a proper place for brokerage offices, negative advertisement against the Fund especially by the Social Security Organization, poor cooperation between rural institutions and brokers, poor administrative system, the vagueness of rural insurance rules for people, continuous changes in rules, and mismanagement. The key factor of poor awareness-raising measures was emphasized as the most essential institutional barrier to rural women’s participation in social insurance. The main concepts constituting this factor include “weakness of advertising in national and local television and radio broadcasts” (with a frequency of 57) and “inadequate awareness-raising measures about insurance” (with a frequency of 45). One another important institutional barrier to rural women’s participation in social insurance was found to be inefficient advertisement methods whose most important constituent concepts included “better advertising of private insurance and social security to attract policyholders” and “ignoring local culture and conditions in the type and extent of advertisement.”

5 Discussion

The results showed that legal barriers are among the main obstacles to rural women’s participation in social insurance. Rural women constitute half of the rural population in Iran. However, they are not culturally of the same status as the men, which shows its implications in the form of the non-participation of women in development activities. The culture of rural communities gives limited authority and freedom of communication to women due to the dominance of patriarchic culture. In these cultural conditions, rural women who are used to the ruling culture avoid any behavior that is not within their acquired mental framework. In other words, it can be said that cultural factors penetrate traditions, values, norms, religious beliefs, and insights of people, thereby hindering women’s participation in different affairs, so their participation in social insurance will face problems in Iran’s cultural conditions. The adverse cultural traditions and gender-related cultural beliefs have been mentioned as barriers to participation in Shafiei Sabet et al. (2018), Ataei et al. (2022), and Safari Shali (2008). Similarly, Varmazyari and Moradi (2017) and Dustmohammadloo et al. (2023) reported the poor insurance culture in traditional rural and nomadic communities as the reason for low participation in social insurance.

Some weaknesses identified in this research are related to the institutional structure of SIF. Poor advertisements, the inefficiency of brokers, poor interaction between the Fund and parallel insurance institutions, and poor management created conditions in which rural women’s participation can be expected to be at a low level. Tao (2017), Giles et al. (2021), Rezvani and Azizi (2013), and Afrakhteh et al. (2016) support this finding. They have also stated that structural and institutional barriers can reduce people’s participation in social insurance, making its development difficult in societies.

Presently, equality and justice between women and men have been accepted by people, and planners and policymakers emphasize the need for the participation of both women and men in development programs. As with other human rights, women have the right to be treated as equally as men are in using social insurance, but various social barriers impede them from participating in this insurance. Personal and personality characteristics, the power structure in the family, knowledge and literacy, and social trust are some factors that influence women’s participation in formal activities. The power structure in most rural families of Iran is in favor of men, and women are less informed and naturally less aware of different social affairs than men. Living in these conditions reduces the social trust of women’s community whereas the adoption of social insurance requires awareness, self-confidence, self-belief, and trust in society. Ramesh (2007), Moradhaseli et al. (2023), and Angelini and Hiros (2004) have concluded that the social barriers to women’s participation in social insurance are a function of low social trust and low literacy and awareness.

Although rural women have always been a key part of labor and production in rural communities and have participated in the economic activities of the rural household (which are mostly related to the crop and animal farming sectors) in various forms, their economic activities are regarded as a part of family labor with no wage payment by the family head. This limits the economic capacity of rural women for investment and money spending. Indeed, they can be considered unemployed employed people who are lowly involved in activities that require investment and money spending since they do not receive a direct wage. Participation in social insurance requires paying the premium, which is influenced by the dominance of the economic culture on rural women’s employment. Other researchers (Chen et al., 2017; Javanmard et al., 2019; Green et al., 2021; Moradhaseli et al., 2022) have also regarded economic barriers (e.g., the poor economy of the rural family and women’s economic dependence on the household head) as the main factors that influence women’s participation in social insurance.

The results reveal that legal barriers also hinder rural women’s participation in social insurance. These barriers to the development of the Fund within communities are impediments to their goals and cause dissatisfaction whereas rules and regulations are designed and enacted by planners and policymakers to handle the affairs of communities, organizations, and institutions. If these regulations do not satisfy the needs of the majority, since they have an extensive scope, they will get farther from their goals and become obstacles and challenges. Other authors (Miao et al., 2018; Ataei et al., 2018; Peng and Ling, 2019; Obadha et al., 2020; Ebrahimi et al., 2023) have supported this finding and expressed that awkward and tough regulation will reduce people’s motivation to accept social insurance.

6 Conclusion

In the past, family needs were traditionally supplied by family members (Talebi Khameneh et al., 2023; Mansourihanis et al., 2024). Following social and economic reforms and renovations and transformations in living style, the methods of supporting vulnerable people changed, and the social welfare policy was shifted from the traditional style to government-managed support policies. One of the most important social welfare policies in present societies is social insurance, which has been established to support people in old age and during unemployment periods. In other words, governments have adopted measures to cover their urban and rural populations and can supply people’s future by alleviating the implications of old age, poverty, and sickness periods. This is more eminent in rural areas, especially for rural women. Since rural women participate in social insurance to a lesser extent than rural men, we aimed to explore the barriers to rural women’s participation in social insurance in the present work to find out the obstacles to women’s participation, especially in the Social Insurance Fund of Farmers, Villagers, and Nomads (SIF) and to propose solutions for resolving these obstacles, thereby contributing to the realization of social justice, especially gender justice. The results showed that the barriers to rural women’s participation in social insurance are in five broad categories: cultural, institutional, social, economic, and legal barriers. In other words, the results of this study revealed that to improve rural women’s participation in social insurance, the cultural, institutional, social, economic, and legal barriers must be solved by various organizations and people. So, the barriers to rural women’s participation are not limited to only one aspect, but there is a set of factors that impede their participation in insurance. In other words, there must be an all-inclusive view to understand and plan for social insurance development. Each of these factors may be rooted in the macro-policies of the government, social and personal norms, cultures, regional and family conditions, and many more. So, a precise plan is required to tackle each set of these barriers.

According to the results for economic barriers, it is recommended to SIF policymakers to set a premium for women that will allow maximizing their participation considering the economic and income level of non-insured rural women. Cultural barriers, also, show that SIF planners should develop the culture of insurance in the target community by training and thereby contribute to maximizing women’s participation in social insurance by adopting incentive policies for the membership of couples and creating specific benefits and facilities for women who apply for the insurance. Furthermore, since most social barriers are related to rural women’s knowledge and awareness, it is recommended to adopt measures for enhancing their awareness and trust in future policies in order to develop social insurance among rural women. To tackle legal barriers, a revision should be made in the legislation procedure of the Fund and in bylaws and regulations that are enacted with no scientific and experimental support. This shows that to motivate women’s participation in the Fund, it is necessary to revise or eliminate discriminative regulations and develop new regulations as per the needs and opinions of the target community. Finally, to solve the institutional barriers, the higher management of the Fund should lay the ground for implementing sound advertisement programs through available and popular media, create constructive interactions with parallel insurance organizations in rural areas, and cooperate with experienced institutions in rural and nomadic areas optimally.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

HG: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Data curation.

Funding

The author declares that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aazami, M., Izadi, N., and Ataei, P. (2019). Women participation in rural cooperatives in Iran. Rural. Soc. 28, 240–255. doi: 10.1080/10371656.2019.1687872

Afrakhteh, H., Jalalian, H., Tahmasebi, A., and Armand, M. (2016). An analysis of the obstacles in front of rural social insurance using analytical network process (ANP) in Hamedan County. J. Res. Rural Plan. 6, 73–91. doi: 10.22067/jrrp.v6i2.56620

Akwaowo, C. D., Umoh, I., Motilewa, O., Akpan, B., Umoh, E., Frank, E., et al. (2021). Willingness to pay for a contributory social health insurance scheme: a survey of rural Resi-dents in Akwa Ibom state, Nigeria. Front. Public Health 9:654362. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.654362

Aliabadi, V., Ataei, P., and Gholamrezai, S. (2024). Sustainability of small-scale knowledge-intensive enterprises in the agricultural sector: a focus on sustainable innovators. J. Knowl. Econ. 15, 4115–4136. doi: 10.1007/s13132-023-01374-x

Anabestani, A., Jafari, F., and Ataei, P. (2024). Female entrepreneurs and creating small rural businesses in Iran. J. Knowl. Econ. 15, 8682–8705. doi: 10.1007/s13132-023-01216-w

Anbari, M., Talebzadeh, H., Talebzadeh, M., Fattahiamin, A., Haghighatjoo, M., and Moghaddas Jafari, A. (2024). Understanding the drivers of adoption for Blockchain-enabled intelligent transportation systems. Tech. J. 18, 598–608. doi: 10.31803/tg-20240411223559

Anderson, J. R. (2001). Risk management in rural development: a review. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

Angelini, J., and Hiros, K. (2004). Extension of social security coverage for the informal economy in Indonesia. Manila: ILO, SubRegional Office for South-East Asia and the Pacific.

Ataei, P., Karimi, H., Moradhaseli, S., and Babaei, M. H. (2022). Analysis of farmers' environmental sustainability behavior: the use of norm activation theory (a sample from Iran). Arab. J. Geosci. 15, 1–13. doi: 10.1007/s12517-022-10042-4

Ataei, P., Khatir, A., Izadi, N., and Frost, K. J. (2018). Environmental impact assessment of artificial feeding plans: the Hammami plain in Iran. Int. J. Environ. Qual. 27, 19–38. doi: 10.6092/issn.2281-4485/7345

Ataei, P., Moradhaseli, S., Karimi, H., and Abbasi, E. (2023a). Hearing protection behavior of farmers in Iran: application of the protection motivation theory. Work 74, 967–976. doi: 10.3233/WOR-210009

Ataei, P., Mottaghi Dastenaei, A., Karimi, H., Izadi, N., and Menatizadeh, M. (2023b). Strategic sustainability practices in intercropping-based family farming systems: study on rural communities of Iran. Sci. Rep. 13:18163. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-45454-z

Ataei, P., Sadighi, H., and Izadi, N. (2021). Major challenges to achieving food security in rural. Iran. Rural Soc. 30, 15–31. doi: 10.1080/10371656.2021.1895471

Bairoliya, N., and Miller, R. (2021). Social insurance, demographics, and rural-urban migration in China. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 91:103615. doi: 10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2020.103615

Bryant, A. (2020). “The grounded theory method” in The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research, 167–199.

Chen, J., and Yang, S. (2014). Rural social security system of China: problems and solutions. Stud. Sociol. Sci. 5, 32–37. doi: 10.3968/j.sss.1923018420140501.4185

Chen, W., Zhang, Q., Renzaho, A. M. N., Zhou, F., Zhang, H., and Ling, L. (2017). Social health insurance coverage and financial protection among rural-to-urban internal migrants in China: evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. BMJ. Glob. Health 2:e000477. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000477

Dustmohammadloo, H., Nikeghbalzadeh, A., Fathy Karkaragh, F., and Souri, S. (2023). Knowledge sharing as a moderator between organizational learning and error management culture in academic staff. Int. J. Multicult. Educ. 25, 56–73. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.10839929

Ebrahimi, P., Dustmohammadloo, H., Kabiri, H., Bouzari, P., and Fekete-Farkas, M. (2023). Transformational entrepreneurship and digital platforms: a combination of ISM-MICMAC and unsupervised machine learning algorithms. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 7:118. doi: 10.3390/bdcc7020118

El Dessouky, N. F. (2023). Post COVID-19: the effect of virtual workplace practices on social sustainable development policy. Int. J. Public Policy Admin. Res. 10, 1–13. doi: 10.18488/74.v10i1.3285

Evangelakaki, G., Karelakis, C., and Galanopoulos, K. (2020). Farmers’ health and social insurance perceptions – a case study from a remote rural region in Greece. J. Rural. Stud. 80, 337–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.10.009

Fan, X., Su, M., Si, Y., Zhao, Y., and Zhou, Z. (2021). The benefits of an integrated social medical insurance for health services utilization in rural China: evidence from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. Int. J. Equity Health 20:126. doi: 10.1186/s12939-021-01457-8

Ghadermarzi, H., Ataei, P., Karimi, H., and Norouzi, A. (2022). The learning organisation approaches in the Jihad-e agriculture organisation, Iran. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 20, 141–151. doi: 10.1080/14778238.2020.1767520

Ghadermarzi, H., Ataei, P., Mottaghi Dastenaei, A., and Bassullu, C. (2023). In-service training policy during the COVID-19 pandemic: the case of the agents of the farmers, rural people, and nomads social insurance fund. Front. Public Health 11:1098646. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1098646

Ghadermazi, H., Fayeghi, N., and Riahi, V. (2021). Explaining the effective factors on the effectiveness of the performance of the social insurance fund for farmers, villagers and nomads (case study: Sarvabad city). Geogr. Eng. Territory 4, 295–308.

Gholamrezai, S., Aliabadi, V., and Ataei, P. (2021). Recognizing dimensions of sustainability entrepreneurship among local producers of agricultural inputs. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 64, 2500–2531. doi: 10.1080/09640568.2021.1875998

Giles, J., Meng, X., Xue, S., and Zhao, G. (2021). Can information influence the social insurance participation decision of China's rural migrants? J. Dev. Econ. 150:102645. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2021.102645

Green, C., Hollingsworth, B., and Yang, M. (2021). The impact of social health insurance on rural populations. Eur. J. Health Econ. 22, 473–483. doi: 10.1007/s10198-021-01268-2

Gui, S. (2018). New Rural Social Endowment Insurance in China: A Critical Analysis, In Studies on Contemporary China Shanghai: WORLD SCIENTIFIC. 3, 65–72.

Hajrasouliha, A., and Shahgholi Ghahfarokhi, B. (2021). Dynamic geo-based resource selection in LTE-V2V communications using vehicle trajectory prediction. Comput. Commun. 177, 239–254. doi: 10.1016/j.comcom.2021.08.006

Inneh, E. G., Ayoola, T. J., Olasanmi, O. O., Fakunle, I. O., and Ologunde, O. A. (2024). Does the strength of women in the upper echelon influence earnings quality? The application of critical mass theory. Int. J. Appl. Econ. Finan. Account. 18, 270–281. doi: 10.33094/ijaefa.v18i2.1387

Izadi, N., Ataei, P., Karimi, H., and Norouzi, A. (2019). Environmental impact assessment of construction of water pumping station in Bacheh bazar plain: a case from Iran. Int. J. Environ. Qual. 35, 13–32. doi: 10.6092/issn.2281-4485/8890

Jamshidi, S., Dehnavi, A., Roudbari, M. V., and Yazdani, M. (2024). An integrated approach through controlled experiment and LCIA to evaluate water quality and ecological impacts of irrigated paddy rice. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31, 45264–45279. doi: 10.1007/s11356-024-34188-8

Javanmard, K., Reshno, B., and Eslami, J. (2019). Investigation and identification of factors affecting the rural population’s tendency to social insurance funds. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Technol. 28, 288–293. Available at: http://sersc.org/journals/index.php/IJAST/article/view/389

Khosravi, S., and Amjadian, M. (2024). A parametric study on the energy dissipation capability of frictional mechanical metamaterials engineered for vibration isolation. In: Proceedings volume 12946, active and passive smart structures and integrated systems XVIII; 1294615.

Liu, Z., Li, K., Zhang, N., Li, L., and Fan, Y. (2018). Are farmers’ behaviors rational when they pay less for social endowment insurance? Evidence from Chinese rural survey data. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 54, 2995–3012. doi: 10.1080/1540496X.2017.1382347

Ma, X., and Oshio, T. (2020). The impact of social insurance on health among middle-aged and older adults in rural China: a longitudinal study using a three-wave nationwide survey. BMC Public Health 20:1842. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09945-2

Mansourihanis, O., Maghsoodi Tilaki, M. J., Sheikhfarshi, S., Mohseni, F., and Seyedebrahimi, E. (2024). Addressing Urban Management challenges for sustainable development: analyzing the impact of neighborhood deprivation on crime distribution in Chicago. Societies 14:139. doi: 10.3390/soc14080139

Miao, Y., Gu, J., Zhang, L., He, R., Sandeep, S., and Wu, J. (2018). Improving the performance of social health insurance system through increasing outpatient expenditure reimbursement ratio: a quasi-experimental evaluation study from rural China. Int. J. Equity Health 17:89. doi: 10.1186/s12939-018-0799-8

Moradhaseli, S., Ataei, P., Farhadian, H., and Ghofranipour, F. (2019). Farmer’s preventive behavior analysis against sunlight by using health belief model: a study from Iran. J. Agromedicine 24, 110–118. doi: 10.1080/1059924X.2018.1541036

Moradhaseli, S., Ataei, P., Karimi, H., and Hajialiany, S. (2022). Typology of Iranian farmers’ vulnerability to the COVID-19 outbreak. Front. Public Health 10:1018406. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1018406

Moradhaseli, S., Ataei, P., Karimi, H., Hajialiany, S., and Norouzi, A. (2023). Designing an economic empowerment model for self-employed women under the MENARID project in Iran. SN Bus. Econ. 3, 1–20. doi: 10.1007/s43546-023-00480-x

Moradhaseli, S., Ataei, P., Van den Broucke, S., and Karimi, H. (2021). The process of farmers’ occupational health behavior by health belief model: evidence from Iran. J. Agromedicine 26, 231–244. doi: 10.1080/1059924X.2020.1837316

Moradhaseli, S., Mirakzadeh, A. A., Rostami, F., and Ataei, P. (2018). Assessment of the farmers’ awareness about occupational safety and health and factors affecting it; a case study in Mahidasht, Kermanshah Province. Health Educ. Health Promot. 6, 23–29. doi: 10.29252/HEHP.6.1.23

Moradhaseli, S., Sadighi, H., and Ataei, P. (2017). Investigation of the farmers’ safety and protective behavior to use pesticides in the farms. Health Educ. Health Promot. 5, 53–65. Available at: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-8131-en.html

Naderi, F., Perez-Raya, I., Yadav, S., Pashaei Kalajahi, A., Mamun, Z. B., D’Souza, M., et al. (2024). Towards chemical source tracking and characterization using physics-informed neural networks. Atmos. Environ. 334:120679. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2024.120679

Obadha, M., Colbourn, T., and Seal, A. (2020). Mobile money use and social health insurance enrolment among rural dwellers outside the formal employment sector: evidence from Kenya. Int. J. Health Plann. Manag. 35, e66–e80. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2930

Peng, B. L., and Ling, L. (2019). Association between rural-to-urban migrants' social medical insurance, social integration and their medical return in China: a nationally representative cross-sectional data analysis. BMC Public Health 19:86. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6416-y

Ramesh, T. V. (2007). Rural initiative, micro-insurance. Beijing: School of Statistic, Central Univercity of Finance and Economics.

Rezvani, M. R., and Azizi, F. (2013). Challenges on rural and nomadic social insurance in Iran. Soc. Welfare Q. 13, 271–311. Available at: http://refahj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1241-en.html

Safari Shali, R. (2008). A study on social and cultural factors related to the participation level of rural women. Woman Dev. Polit. 6, 137–159.

Samad, N. H. A., Ahmad, N. H., and Ismail, R. F. (2024). Social entrepreneurial orientation and social value of nonprofit organisation during crises. Edelweiss Appl. Sci. Technol. 8, 45–58. doi: 10.55214/25768484.v8i1.415

Sasikumar, G. M., and Sujatha, S. (2024). Perceptions of women employees on the quality of work life practices in the electronics manufacturing industry - an analysis. Qubahan Acad. J. 4, 129–152. doi: 10.48161/qaj.v4n2a488

Scholes, J. (2020). The practice of grounded theory: An interpretivist perspective Critical Qualitative Health Research: Exploring Philosophies, Politics and Practices, London: Routledge.

Shafieezadeh, H., Mojaradi, G., and Karami Dehkordi, E. (2013). The affecting of the institutionalization of social insurance in rural areas of the Kabodarahang township. J. Rural Res. 3, 189–214. doi: 10.22059/jrur.2013.30237

Shafiei Sabet, N., Hosseinei, S., and Maleki, H. (2018). Analysis of economic barriers of women participation in the process of rural development (case study: Hamedan village city). Geogr. Hum. Relationsh. 1, 685–705.

Sharifi, M., and Hosseini, S. (2009). Factors affecting the adoption of social insurance among farmers: a case study of Ghorveh and Dehgolan counties in Kordestan province of Iran. Village Dev. 12, 37–67.

Shu, L. (2018). The effect of the new rural social pension insurance program on the retirement and labor supply decision in China. J. Econ. Ageing 12, 135–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jeoa.2018.03.007

Talebi Khameneh, R., Elyasi, M., Özener, O. O., and Ekici, A. (2023). A non-clustered approach to platelet collection routing problem. Comput. Oper. Res. 160:106366. doi: 10.1016/j.cor.2023.106366

Tao, J. (2017). Can China’s new rural social pension insurance adequately protect the elderly in times of population ageing? J. Asian Public Policy 10, 158–166. doi: 10.1080/17516234.2016.1167413

Vaez Roudbari, V., Dehnavi, A., Jamshidi, S., and Yazdani, M. (2024). A multi-pollutant pilot study to evaluate the grey water footprint of irrigated paddy rice. Agric. Water Manag. 282, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.agwat.2023.108291

Varmazyari, H., and Moradi, M. (2017). Analysis of obstacles related to the development of social security of farmers, villagers, and nomads in Kermanshah County. Soc. Welfare Q. 17, 291–320. Available at: http://refahj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3030-en.html

Vu, V. V., Nguyen, P. M., and Hoang, V. H. (2024). Does job satisfaction mediate the relationship between corporate social responsibility and employee organizational citizenship behavior? Evidence from the hotel industry in Vietnam. Int. J. Innovat. Res. Sci. Stud. 7, 1017–1029. doi: 10.53894/ijirss.v7i3.3012

Wu, Y., and Xiao, H. (2018). Social insurance participation among rural migrants in reform era China. Asian Pac. Migr. J. 27, 383–403. doi: 10.1177/0117196818808412

Xie, S., Chen, J., Ritakallio, V. M., and Leng, X. (2021). Welfare migration or migrant selection? Social insur-ance participation and rural migrants’ intentions to seek permanent urban settlement in China. Urban Stud. 58, 1983–2003. doi: 10.1177/0042098020936153

Yang, M. (2018). Demand for social health insurance: evidence from the Chinese new rural cooperative medical scheme. China Econ. Rev. 52, 126–135. doi: 10.1016/j.chieco.2018.06.004

Keywords: grounded theory, participation barriers, rural women’s participation, social insurance of farmers, villagers, and nomads, social welfare

Citation: Ghadermarzi H (2024) Barriers to rural women’s participation in social insurance for farmers, villagers, and nomads: the case of Iran. Front. Sociol. 9:1433009. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2024.1433009

Edited by:

Anelise Gregis Estivalet, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, FranceReviewed by:

Hari Harjanto Setiawan, National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), IndonesiaYasar Selman Gültekin, Duzce University, Türkiye

Copyright © 2024 Ghadermarzi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hamed Ghadermarzi, Z2hhZGVybWFyemlAa2guYWMuaXI=

Hamed Ghadermarzi

Hamed Ghadermarzi