94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

CONCEPTUAL ANALYSIS article

Front. Sociol., 30 May 2024

Sec. Work, Employment and Organizations

Volume 9 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2024.1378665

This article is part of the Research TopicRe-Building and Re-Inventing WorkplacesView all 6 articles

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated pre-existing challenges faced by academic staff in UK higher education and drawn attention to issues of Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI). Amidst global competitiveness and workplace pressures, challenges such as managerialism, increased workload, and inequalities have worsened, significantly impacting mental health. This paper presents a conceptual analysis connecting EDI with organizational compassion within the context of Higher Education. The prioritization of organizational compassion is presented as a means to enhance sensitivity to EDI in the reconstruction of post-pandemic learning environments. Anchored in the organizational compassion theory and the NEAR Mechanisms Model, our study contributes to the intersection of the organizational compassion, EDI and higher education literatures by exploring how fostering compassion relations can contribute to enhancing EDI. This offers a new perspective to creating a more humane and supportive higher education environment.

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted higher education, as evidenced by several studies (Pan, 2020; Rapanta et al., 2020; Dinu et al., 2021; Wray and Kinman, 2022; Denney, 2023), intensifying pre-existing challenges such as managerialism, increased workload, and inequalities, all of which have worsened the mental health of academic staff. As the pandemic reshapes the higher education environment, it accentuates critical areas requiring attention. One such area relates to Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI), concerned with the ensuring fair treatment, access, opportunity, and advancement for all, including those of minority ethnic and identity groups (Nishii, 2013; Górska et al., 2021; Alkan et al., 2022; Mickey et al., 2023).

In response to the challenges heightened by the COVID-19 pandemic, UK universities have been compelled to re-evaluate their teaching methods and support systems. Unfortunately, these changes have inadvertently burdened academic staff, leading to heightened work-related stress and additional difficulties, particularly for staff of color and women (Górska et al., 2021; Mickey et al., 2023). The amalgamation of increased demands to prioritize a 'students first' logic (Denney, 2022) and a simultaneous reduction in available resources has taken a considerable toll on the overall well-being of academic staff (Wray and Kinman, 2022).

The UK's higher education system finds itself amidst upheaval, as it navigates a global atmosphere of competitiveness, complexity, and uncertainty (Maratos et al., 2019; Denney, 2020, 2021b, 2023; Waddington, 2021). Factors such as increasing market competition, managerialism, workplace inequality, and continuous workload pressure have contributed to heightened mental health risks among academic staff (Kinman, 2001; Wallmark et al., 2013; Waddington, 2016; Denney, 2020; Urbina-Garcia, 2020; Shen and Slater, 2021; D'Cruz et al., 2023). Particularly vulnerable to such pressures are those staff associated underrepresented minority groups such as women facing gender-related challenges; LGBTQ+ individuals encountering visibility and acceptance issues, individuals with disabilities facing accessibility and attitudinal barriers, international scholars navigating cultural adjustments; religious minorities contending with potential bias; and individuals from Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities.

Considering these challenges, the significance of EDI in higher education cannot be overstated. EDI represents foundational values that advocate for the equitable treatment and full engagement of all individuals, particularly those historically marginalized or subjected to discrimination based on factors such as gender, background, identity, and (dis)ability (Gill et al., 2018; Özbilgin, 2019). This commitment extends to addressing the specific barriers encountered by various marginalized populations, including people of color, women, LGBTQ+ individuals, individuals with disabilities, indigenous peoples, refugees, and those on the autism spectrum (Wolbring and Lillywhite, 2021). Despite historical efforts to advance EDI in higher education, academic staff still grapple with inequality, discrimination, and exclusion events (Özbilgin, 2009; Fossland and Habti, 2022; Hofstra et al., 2022). Recognizing that cultivating EDI is of core importance in higher education, there is a critical need to reconstruct a compassionate and inclusive learning environment, extending beyond embracing diversity among academic staff.

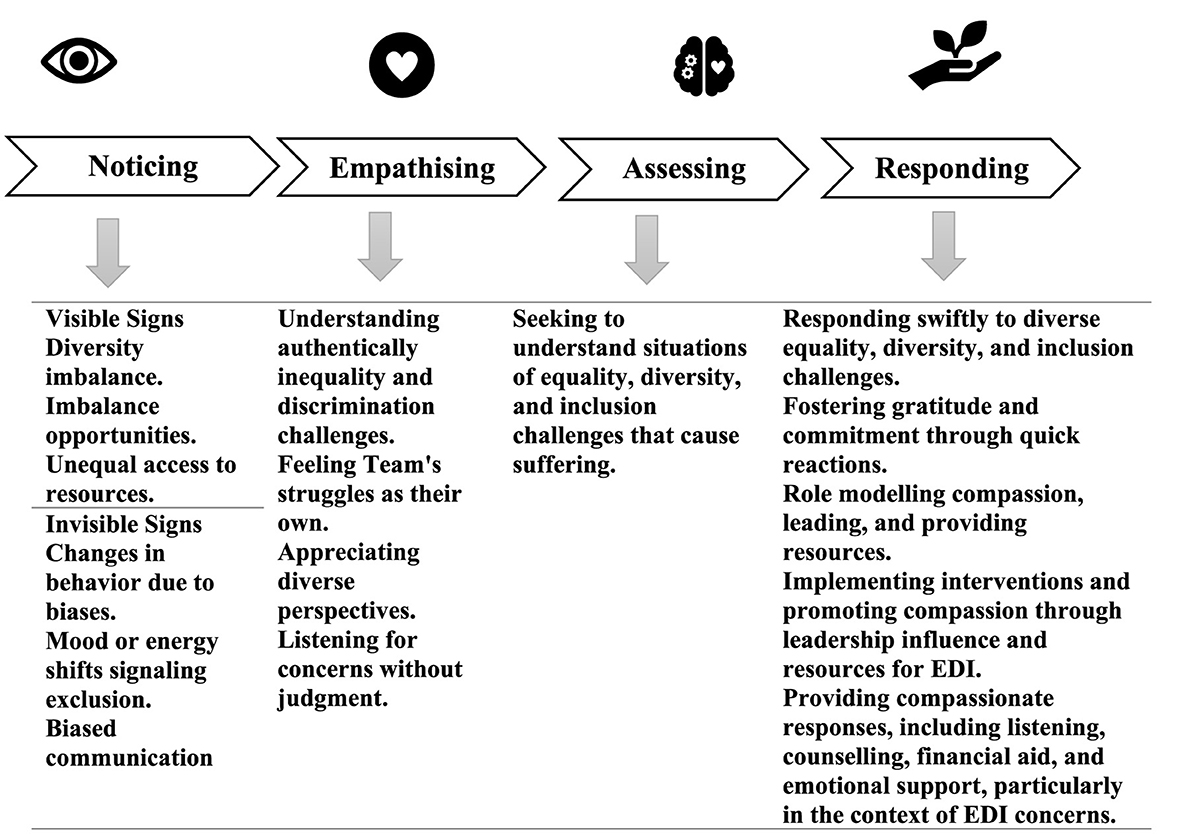

To address these challenges, our conceptual analysis explores the intersection of these concepts and issues through reflective practices. We propose leveraging an organizational compassion lens. Within the higher education context, compassion can be understood as a dynamic interpersonal and social process characterized by NEAR: noticing suffering experienced by students and academic staff, empathizing with their distress, appraising their suffering through a specific perspective, and responding by undertaking meaningful actions to alleviate their hardships (Kanov et al., 2004; Dutton et al., 2014; Worline and Dutton, 2017, 2022; Simpson et al., 2019a). Investigating the dynamic interaction between workplace compassion and the advancement of EDI, along with their reciprocal impacts, emerges as a recognized potential focus within the field of applied compassion scholarship. This holds particular significance considering the criticism surrounding the efficacy of diversity training, a prevalent tool in EDI initiatives, often deemed ineffective or even counterproductive (Dobbin and Kalev, 2018).

Exploration of the nexus between organizational compassion and EDI is, however, still at an early stage of emergence. Gibbs (2019, p. 161) argues that “compassion lies at the core of diversity.” Emirza (2022, p. 31) suggests that specifically compassionate leadership can act as a mechanism for “fostering a sense of inclusion among diverse employees.” Kizilenis Ulusman et al. (2023, p. 22), drawing insights from their empirical study involving 25 female migrant participants, propose that “compassion in organizations can be a valuable resource for addressing diversity-related challenges.” These observations indicate the potential of approaching EDI through an organizational compassion lens. Accordingly, in this article we seek to theorize further the potential of promoting EDI through an organizational compassion theory lens. More specifically we propose the NEAR (Noticing, Empathizing, Assessing, and Responding) Mechanisms Model as practical framework to guide the cultivation of EDI in higher education. This strategic approach aims to support not only alleviating the struggles faced by marginalized academic staff but to build a more human-centered and compassionate higher education environment in the post-pandemic era.

Our paper is structured as follows: firstly, we provide a comprehensive exploration of the impact of neoliberal managerialism on higher education, its challenges to EDI, the associated mental health impacts. Additionally, we propose a framework for rebuilding learning environments through organizational compassion.

Universities are traditionally envisioned as learning environments that serve to create a positive and safe foundation for teaching and are integral elements of the education system. Leadership within universities assumes a vital role in promoting the development of positive and inclusive environments in which knowledge creation, cultural transmission, free thought, and the pursuit of truth can thrive, as well as inspiring the values of integrity, respect, and compassion throughout their institutions (Flückiger, 2021; Waddington, 2021). Additionally, universities are committed to fostering equality and inclusion among diverse groups of individuals (Özbilgin and Erbil, 2021, 2023). While universities often express commitment, particularly for staff members, including academic staff or students, the reality may not always reflect this dedication (Maratos et al., 2019). Moreover, as Marginson (2020) highlights, higher education faces fundamental challenges associated with a growing economy and social inequality globally. He emphasizes that while higher education plays a vital role, it cannot address these challenges thoroughly on its own. Other sectors, such as wage and salary determination, taxation, and government programmes are often more influential in shaping societal inequalities (Marginson, 2020). This broader view is crucial when exploring into the impact of neoliberal managerialism on EDI in higher education, as we will further explore next.

The impact of neoliberal managerialism on EDI in higher education has become more evident as the landscape has undergone significant changes (Maratos et al., 2019; Denney, 2020; Waddington, 2021). This shift has created a global atmosphere of competitiveness, complexity, and uncertainty, particularly in the UK, where higher education is in a perpetual state of change and turbulence (Denney, 2021b). Neoliberalism's influence on higher education in the UK dates back to the 1970s, coinciding with the political leadership of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan and the subsequent global spread of four key changes in political economy capitalism: privatization, deregulation, financialization, and globalization (Radice, 2013). This neoliberal paradigm, as highlighted by Benatar et al. (2018), is associated with negative consequences such as increased poverty, inequality, and the pervasive commercialization of social life and educational systems. Radice (2013) contends that neoliberalism has manifested as new managerialism in the UK public sector, characterized by the adoption of private business sector structures, technologies, and values. Specifically, new managerialism blends hierarchical control with elements of the free market, imposing private sector values on the public sector (Deem, 1998) and shifting the university's focus from elite education to contributing marketable skills and research outputs to the “knowledge economy” (Radice, 2013, p. 408). New managerialism in higher education involves internal cost centers, staff rivalry, marketization of public sector services, and the monitoring of efficiency through outcome measurement and performance evaluation, particularly for academic staff (Deem, 1998). Performativity in managing academic labor in UK universities is a key aspect of new managerialism, as detailed performance measurement shifts the culture from collegial to managerial (Cowen, 1996).

Academic women face unique challenges as a result of cultural shifts in higher education. UK higher education institutions' underlying systems, structures, processes, and cultures are inherently referred to as masculine managerialism since they were designed for men, contributing to systemic gender biases. The combination of masculinized higher education institutions with neoliberalism's performativity has created a challenging environment hindering the progression of academic women into senior leadership roles (Denney, 2021a).

In tandem with gender inequalities, racial disparities persist in higher education, posing a significant concern for academia. Fossland and Habti (2022) highlight ongoing racial inequalities in higher education, emphasizing the continued support for white male scientists and their scientific contributions, diminishing the visibility of research contributions from women and minority scholars. This intersectionality of gender and race underscores the need for a comprehensive approach to address multiple dimensions of inequality in academia.

It is crucial to recognize and rectify inequality issues in UK higher education institutions across various other dimensions. LGBTQ+ representation, disability inclusion, and the intersectionality of identities must also be central considerations in fostering a truly inclusive higher education environment. Research consistently demonstrates that diverse and inclusive institutions not only enhance innovation and research but also contribute to advancements in science (Østergaard et al., 2011; Nielsen et al., 2017, 2018). Thus, a comprehensive approach to EDI is essential for the flourishing of academics representing diverse groups in higher education, but also the realization of new discoveries and advancements in knowledge.

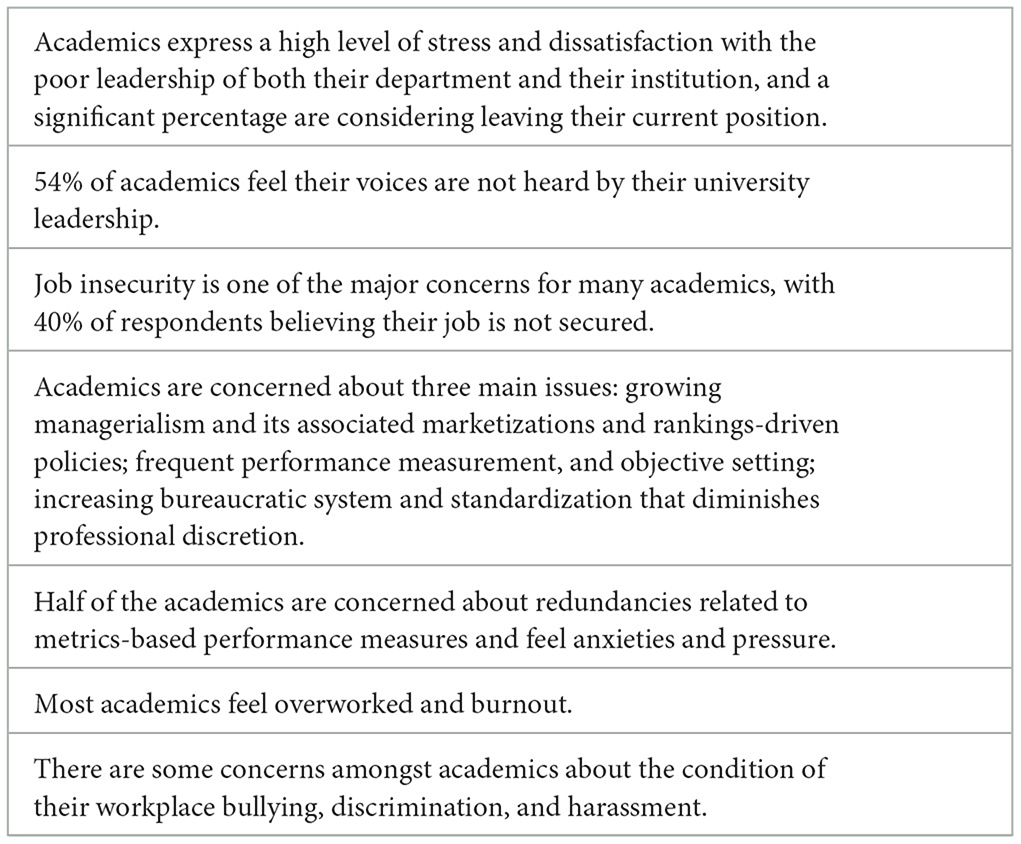

Considering the EDI challenges faced by academic staff in UK higher education institutions, it is not surprising that many academics struggle in what are experienced as challenging and toxic environment in which to work (Denney, 2020). This is notably reflected in highlights from the latest Times Higher Education University Workplace survey (2016), which included 1,398 (49 percent) UK academics from nearly 150 universities across the UK (as shown in Table 1), revealing that academics are increasingly suffering at work. Consideration of these pre-pandemic findings would suggest that, in the interim, circumstances have likely deteriorated further.1

Table 1. Times Higher Education University Workplace Survey 2016 (Grove, 2016).

As illustrated in Table 1, academics reported experiencing high levels of stress and dissatisfaction with their institutions' leadership, with a significant percentage considering resigning from their roles. Additionally, 54% of academics felt unheard by their institution's leadership (Grove, 2016). These findings are concerning and could be indicative of a dearth of compassionate leadership at UK universities. The survey further revealed that a substantial number of academics were worried about job insecurity, with 40% feeling their positions were at risk of redundancy. Specifically, academics expressed anxiety and pressure related to metrics-based performance measures, as well as concerns about expanding managerialism, frequent performance monitoring, and an increasingly bureaucratic system that eroded professional discretion (Grove, 2016).

A more recent empirical study surveying over five thousand academic staff from across the UK found that academic personnel frequently encountered difficult, stressful, and sometimes humiliating situations (Erickson et al., 2021). More relevant to the state of EDI in UK higher education institutions, this study highlighted those chronic issues of bullying, discrimination, and harassment, along with elevated levels of mental health difficulties, general health and wellbeing concerns, and alarming levels of hopelessness and dissatisfaction among UK academics. Other research has reported that disabled university professors, instructors, teachers, and researchers, were particularly vulnerable to unfair treatment, biased discrimination, bullying, and harassment, placing them at a higher risk of burnout (Wolbring and Lillywhite, 2023).

In sum, the pervasive impact of neoliberal managerialist logic on academic life, as evidenced by the stress, dissatisfaction, and mental distress experienced by academic staff, particularly those in vulnerable positions, underscores the urgency of transformative measures. The existing conditions, marked by limited EDI and the resulting toxic work environment in universities, demand a paradigm shift toward organizational compassion. The distress faced by academic members not only highlights the need for immediate alleviation but also emphasizes the imperative to rebuild universities with a foundation rooted in compassion. Beyond addressing the sufferings of academic staff, this transformation calls for a steadfast commitment to respecting diversity, fostering inclusion, and valuing equality, as emphasized by Gibbs (2019). In the upcoming section, we consider the value of compassion and its pivotal role in promoting EDI in the context of higher education.

Scholars have recently begun to emphasize the value of organizational compassion and caring in advancing EDI (Rynes et al., 2012), which is also applicable to the higher education context. Compassion serves as a dynamic force that bridges individuals with the wider community and forms the core principles for EDI (Nussbaum, 1996; Gibbs, 2019). Expanding on this viewpoint, Waddington (2018) argues that universities have a moral and legal responsibility to take reasonable measures to protect all individuals associated with the institutions from personal physical and/or emotional suffering, including both academic staff and students.

Organizational scholars view compassion not merely as an emotion but as a dynamic interpersonal and social process (Goetz et al., 2010; Simpson et al., 2019b, 2022). In the context of higher education and EDI it begins with recognizing suffering among students and academic staff, particularly within areas of inequality, injustice, and racism. Beyond recognizing suffering, the compassion process continues when there is empathy for the sufferer's pain, assessing of the suffering through a particular lens, and a response of taking meaningful action to alleviate the distress (Kanov et al., 2004; Dutton et al., 2014; Strauss et al., 2016; Stellar et al., 2017; Worline and Dutton, 2017, 2022; Anstiss et al., 2020; Waddington, 2021).

Building on this definitional foundation of organizational compassion as a NEAR process of noticing, empathizing, appraising and responding to address workplace suffering, Simpson and Farr-Wharton (2017), Simpson et al.'s (2019b, 2020) NEAR mechanisms model of organizational compassion integrates these key processes with facilitative organizational mechanisms. We argue that this model, which offers a practical framework for cultivating organizational compassion, can be drawn upon to manage organizational processes fostering EDI systematically and consciously (Figure 1). 2

Figure 1. NEAR framework lens (Dutton et al., 2014; Simpson and Farr-Wharton, 2017; Simpson et al., 2019a, 2023).

In the context of fostering EDI within higher education, an essential initial step in fostering healing, is the act of noticing distress. Compassionate leaders play a crucial role in fostering an environment where academic members can openly discuss their distress. By cultivating a culture openness and trust, leaders can inspire employees to support one another through compassionate actions whether through words, presence, or in providing tangible support, such as making available existing resources or coordinating to generate new resources. Such empowerment leads to the cultivation of a collective capacity for compassion, which is crucial during difficult times. These examples indicate that compassionate leadership involves more than showing personal compassion and caring for a colleague or dependent in need (Dutton et al., 2002; Poorkavoos, 2016).

In the context of addressing inequality within the academic setting, noticing becomes the initial step in cultivating awareness of indicators, both visible and invisible (Simpson et al., 2015). Recognizing these signals is crucial for noticing inequality in the academic environment. These subtle signals can demonstrate through changes in mood, energy levels, daily routines, language use, or changes in behavior (Dutton et al., 2014).

In the realm of higher education not everyone openly articulates their struggles. This highlights the importance of leaders being sensitive to these less overt signs. Noticing these subtle signals enables leaders to identify potential imbalance opportunities, access to resources, or instances of bias. A deeper awareness of these subtle indicators empowers leaders to take proactive action, cultivating a more fair, equitable and inclusive learning environment for all (Chang and Milkman, 2020; Özbilgin and Erbil, 2023).

Empathizing is the second step in the NEAR framework. In the pursuit of equality, a leader actively engages in this crucial step by authentically connecting with the challenges faced by their followers, internalizing the team's struggles as if they were their own (Dutton et al., 2014; West, 2021). This empathetic approach, closely connected with recognizing and appreciating each team member's unique perspective, fosters an environment where attentive listening and mutual understanding flourish (Gibbs, 2019).

Appraising is the third step which refers to leaders keenly assess the situation and underlying causes of challenging work situations that contribute to academic staff suffering, demonstrating a keen appraisal of their team's struggles (West, 2019, 2021). In the context of promoting equality, diversity, and inclusion, this proactive assessment aims to identify and rectify any inequalities, job segregation, unfairness, or discriminatory practices that may be triggering difficulties for team members (DiTomaso and Parks-Yancy, 2014). Furthermore, it involves establishing a socially sustainable learning environment (D'Cruz et al., 2023) where individuals are treated fairly and have equal opportunities. This includes addressing issues related to gender inequality and ensuring that every team member, regardless of background, can thrive and contribute to their fullest potential.

Thus far, we have presented the NEA (noticing, empathizing, and appraising) process model of organizational compassion theory. However, a response is required to complete the process (Simpson et al., 2020). Responding involves taking action to address challenges faced by a diverse group of academic members (Dutton et al., 2006; Emirza, 2022). A compassionate response particularly involves recognizing a co-worker's suffering and providing resources to alleviate it. When the response to alleviate suffering is prompt, it indicates efficient compassion organizing to address diverse needs and promote an inclusive environment (Dutton et al., 2002, 2006; Worline and Dutton, 2017). A quick reaction to suffering is seen as a hallmark of genuine care and concern, enhancing the likelihood of gratitude and commitment from the recipient of compassion (Simpson et al., 2013, 2015).

Thus far we have looked at an organizational compassion informed view of how EDI can be cultivated within higher education institutions through a fourfold NEAR process, however, it is also important to consider how this process can be facilitated through leveraging organizational mechanisms. In the following section, we focus specially on the mechanisms of organizational leadership and organizational culture.

Among the six organizational social architecture mechanisms crucial for facilitating workplace compassion, such as relational networks, routine practices, roles, and stories told, leadership and culture stand out as pivotal factors that compassionate organizations can prioritize to enhance their compassion capabilities (Dutton et al., 2006, 2014; Worline and Dutton, 2017). Accordingly, we will discuss leadership and culture in turn within the context of leveraging organizational compassion to enhance EDI.

Leaders in higher education have a duty to not only uphold certain shared values such as a passion and commitment to the pursuit of the truth, knowledge dissemination, and freedom (Dearing and National Committee of Inquiry Into Higher Education, 1997). Additionally, they are responsible for promoting an inclusive environment where all members, such as academic members and students, feel welcomed, valued, and respected regardless of their identities, backgrounds, and experiences (Emirza, 2022). These fundamental values provide an opportunity for those who work in higher education, particularly academic members, to engage more to community and teaching activities for the benefit of all (Waddington, 2021). Therefore, universities would benefit from cultivating a compassionate caring working atmosphere, with leaders playing a significant role. It is observed, however, that this is often not the case, especially for academics (Maratos et al., 2019), particularly those representing EDI domains.

Research findings show that traditional equality, diversity, and inclusion training within institutions have faced criticism for being ineffective or even having some negative effects (Dobbin and Kalev, 2018). Furthermore, universities' hectic and toxic work environments significantly impact the physical health, emotional wellbeing, meaningful social connections, and cognitive performance of academic members (Waddington, 2016; Denney, 2020, 2021a). Despite the growing stress among academic members at work, universities have the potential to be compassionate caring environments for all academic staff and students (Waddington, 2016, 2021).

Within the context of suffering and EDI, leaders can start the healing process by role modeling compassionate behavior through their presence, leading processes of sense making, and providing resources to take action in addressing distress (Dutton et al., 2002, 2006; Worline and Dutton, 2017). Furthermore, leaders have the resources and influence to promote compassion and make meaning in the institutions they lead (Dutton et al., 2006; Worline and Dutton, 2017; Simpson et al., 2019a, 2020, 2022). Compassionate responses may involve attention from leaders, empathic listening (Worline and Dutton, 2017), counseling and psychological support, financial aid (Simpson et al., 2019a, 2020), compassionate leave, and hybrid working during times of crisis, such as COVID-19. These compassionate leadership interventions can enhance inclusiveness and support diversity (Emirza, 2022).

An argument for positing that leadership and inclusive culture are perhaps the most important organizational compassion mechanisms for rebuilding learning environments to align with the principles of EDI, is that leaders significantly influence the extent to which inclusive culture mechanism may be deployed or undermined (see Table 2). Accordingly, we next discuss culture.

Culture is an important explanatory organizational concept (Schein, 2010) that refers to the combination of the members' shared patterns of meaning, beliefs, attitudes, and practices (Simpson et al., 2019a, 2020). It can be observed at three levels: artifacts, espoused values, and basic assumptions. Artifacts include visible organizational structures and processes such as an institution's physical environment, the architecture of university buildings, interior design, landscapes, technologies, and uniforms. Espoused values include organizational' strategies, goals, and philosophies such as value statements, code of conduct, mission statements. Basic assumptions are the unconscious, taken for granted beliefs, values, and feelings that underpin an organization's culture (Schein, 2010). Level one, artifacts, is the most visible. Level two, espoused values, and beliefs are found in published organizational statements on websites, annual reports, policy documents and training material. Level three, basic assumptions, are the most difficult to observe and define (Schein, 2010).

Compassionate leaders can play a significant role in shaping espoused values and basic assumptions, which are critical aspects of a university's culture that influence compassion competence. When compassionate cultures promote the inherent value, capability, and deservingness of all humans, members are more likely to interpret pain generously and engage in compassionate action. Organizational cultures that support compassion competence are characterized by humanistic values such as respect, teamwork, collaboration, inclusiveness, stewardship, dignity, and fairness. To promote a compassionate organizational culture, compassionate leaders should articulate and support values, beliefs, and norms that support human wellbeing, dignity, respect, and inclusion for all members of the academic community (Worline and Dutton, 2017; Gibbs, 2019; Emirza, 2022). As Schein (2010) noted, leadership and culture often go hand in hand, and compassionate leadership can have a significant impact on developing a compassionate institutional culture. Compassionate leadership can promote EDI and shape the culture of their university through their leadership behavior and the structures, routines, rules, and norms that they help to implement individually and collectively (Schein, 2010; West, 2021).

Research findings show that cultivating organizational compassion has numerous benefits for both individuals and organizations (Simpson et al., 2020). These include higher levels of positive emotions, employee loyalty, affective commitment within an organization, and high-quality connection among members of the organization (Lilius et al., 2008, 2011) along with a strengthened sense of authenticity (Ko and Choi, 2020). Consequently, organizational compassion practices hold much promise for alleviating suffering and addressing high levels of staff burnout, anxiety and turnover (Simpson et al., 2020), particularly within the higher education sector. This aligns with the values of equality, diversity, and inclusion, contributing to a more compassionate and caring working environment for staff and learning environment for students.

In the face of current challenges in higher education, prioritizing EDI together with compassion and humanity is crucial for alleviating much suffering experienced by those working within the sector (Gibbs, 2019; Özbilgin, 2019). The challenges faced by academic staff in UK higher education, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, demand an holistic and compassionate response. By incorporating reflective practices into our analysis, we aim to reflect the voices and experiences of academic staff, amplifying their perspectives in our exploration of EDI challenges. Prioritizing EDI through the cultivation of workplace compassion provides an opportunity for rebuilding inclusive learning and working environments post-pandemic. Our conceptual analysis suggests that at the intersection of compassion, EDI, and higher education the application of the NEAR Mechanisms Model, rooted in organizational compassion theory, offers a practical framework for leaders to navigate the complexities of EDI challenges in higher education.

A commitment to EDI combined with a compassionate organizational approach goes beyond merely addressing immediate challenges. It lays the foundation for a sustainable and inclusive future in higher education. By fostering an environment that values diverse perspectives and promotes equal opportunities, institutions can empower individuals and contribute to long-term systemic change. This not only benefits the current generation of academic professionals but also sets a precedent for future cohorts, creating a more resilient and adaptable educational landscape. In essence, the integration of EDI and compassion serves as a transformative force that extends far beyond the current exigencies, shaping a more equitable and compassionate academic community for generations to come.

HHT: Writing—original draft. FD: Supervision, Writing—review & editing. AS: Supervision, Writing—review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^Although the reference gives information about all staff in HE, our table here only refers to academics.

2. ^We have brought together existing compassion process models and applied them to EDI to create this new framework.

Alkan, D. P., Ozbilgin, M., and Kamasak, R. (2022). Social innovation in managing diversity: COVID-19 as a catalyst for change. Eq. Div. Inclusion Int. J. 41, 709–725. doi: 10.1108/EDI-07-2021-0171

Anstiss, T., Passmore, J., and Gilbert, H. (2020). Compassion: the essential orientation. The Psychol. 33, 38–42.

Benatar, S., Upshur, R., and Gill, S. (2018). Understanding the relationship between ethics, neoliberalism and power as a step towards improving the health of people and our planet. Anthropocene Rev. 5, 155–176.

Chang, E. H., and Milkman, K. L. (2020). Improving decisions that affect gender equality in the workplace. Org. Dyn. 49:100709. doi: 10.1016/j.orgdyn.2019.03.002

Cowen, R. (1996). Performativity, post-modernity and the university. Comp. Educ. 32, 245–258. doi: 10.1080/03050069628876

D'Cruz, P., Kanov, J., Simpson, A. V., Noronha, E., Dodson, S., Pei, A., et al. (2023). “Leveraging compassion to address inequality at work,” in Academy of Management Annual Meeting Proceedings, 10–11. doi: 10.5465/AMPROC.2023.13561symposium

Dearing, R., and National Committee of Inquiry Into Higher Education (1997). Higher Education in the Learning Society: Report of the National Committee. London: NCIHE, 34.

Deem, R. (1998). New managerialism and higher education: the management of performances and cultures. in in universities in the United Kingdom. Int. Stud. Sociol. Educ. 8:14. doi: 10.1080/0962021980020014

Denney, F. (2020). Compassion in higher education leadership: casualty or companion during the era of coronovirus? johepal. 1, 41–47. doi: 10.29252/johepal.1.2.41

Denney, F. (2021a). A glass classroom? The experiences and identities of third space women leading educational change in research-intensive universities in the UK. Educ. Manage. Admin. Leadership 22:17411432211042882. doi: 10.1177/17411432211042882

Denney, F. (2021b). The “golden braid” model: courage, compassion and resilience in higher education leadership. johepal. 2, 37–49. doi: 10.52547/johepal.2.2.37

Denney, F. (2022). Working in universities through COVID-19: an interpretation using the lens of institutional logics. in academy of management proceedings. Acad. Manage. 10510:12431. doi: 10.5465/AMBPP.2022.12431abstract

Denney, F. (2023). “Get on with it. cope.”: the compassion-experience during COVID-19 in UK universities. Front. Psychol. 14:2404. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1112076

Dinu, L. M., Dommett, E. J., Baykoca, A., Mehta, K. J., Everett, S., Foster, J. L. H., et al. (2021). A case study investigating mental wellbeing of university academics during the COVID-19 pandemic. Educ. Sci. 11:702. doi: 10.3390/educsci11110702

DiTomaso, N., and Parks-Yancy, R. (2014). The social psychology of inequality at work: Individual, group, and organizational dimensions. Handb. Soc. Psychol. Ineq. 12, 437–457. doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-9002-4_18

Dobbin, F., and Kalev, A. (2018). Why doesn't diversity training work? The challenge for industry and academia. Anthropo. Now 10, 48–55. doi: 10.1080/19428200.2018.1493182

Dutton, J. E., Frost, P. J., Worline, M. C., Lilius, J. M., and Kanov, J. M. (2002). Leading in times of trauma. Harvard Bus. Rev. 11, 54–61.

Dutton, J. E., Workman, K. M., and Hardin, A. E. (2014). Compassion at work. Ann. Rev. Org. Psychol. Org. Behav. 1, 277–304. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091221

Dutton, J. E., Worline, M. C., Frost, J., and Lilius, J. (2006). Explaining compassion organizing. Admin. Sci. Q. 51, 59–96. doi: 10.2189/asqu.51.1.59

Emirza, S. (2022). “Compassion and diversity: a conceptual analysis of the role of compassionate leadership in fostering inclusion,” in Leading With Diversity, Equity and Inclusion: Approaches, Practices and Cases for Integral Leadership Strategy, eds. J. Marques, and S. Dhiman (Cham: Springer), 31–46. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-95652-3_3

Erickson, M., Hanna, P., and Walker, C. (2021). The UK higher education senior management survey: a statactivist response to managerialist governance. Stu. Higher Educ. 46, 2134–2151. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2020.1712693

Flückiger, Y. (2021). The conditions for higher education institutions to meet the social challenges ahead. johepal. 2, 120–129. doi: 10.52547/johepal.2.1.120

Fossland, T., and Habti, D. (2022). University practices in an age of supercomplexity: revisiting diversity, equality, and inclusion in higher education. J. Praxis Higher Educ. 4, 1–10. doi: 10.47989/kpdc355

Gibbs, P. (2019). At the core of diversity is compassion. Glob. Div. Manage. Fusion Ideas Stories Prac. 2019, 161–171. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-19523-6_15

Gill, G. K., McNally, M. J., and Berman, V. (2018). Effective Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Practices. Healthcare Management Forum. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications, 196–199.

Goetz, J. L., Keltner, D., and Simon-Thomas, E. (2010). Compassion: an evolutionary analysis and empirical review. Psychol. Bullet. 136:351. doi: 10.1037/a0018807

Górska, A. M., Kulicka, K., Staniszewska, Z., and Dobija, D. (2021). Deepening inequalities: What did COVID-19 reveal about the gendered nature of academic work?. Gender Work Org. 28, 1546–1561. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12696

Grove, J. (2016). THE University Workplace Survey 2016: results and analysis. Times Higher Education (THE), 1–33. Available online at: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/features/university-workplace-survey-2016-results-and-analysis

Hofstra, B., McFarland, D. A., Smith, S., and Jurgens, D. (2022). Diversifying the professoriate. Socius 8:23780231221085120. doi: 10.1177/23780231221085118

Kanov, J. M., Maitlis, S., Worline, M. C., Dutton, J. E., Frost, P. J., and Lilius, J. M. (2004). Compassion in organizational life. Am. Behav. Sci. 47, 808–827. doi: 10.1177/0002764203260211

Kinman, G. (2001). Pressure Points: A Review of Research on Stressors and Strains in UK Academics. Educational Psychology (Dorchester-on-Thames). Abingdon: Taylor and Francis Group, 473–492.

Kizilenis Ulusman, G., Turnalar-Çetinkaya, N., and Alpay Oraman, E. (2023). “Compassion in organizations: A new perspective for maintaining diversity management,” in Academy of Management Proceedings. Academy of Management Briarcliff Manor, NY, 17808.

Ko, S., and Choi, Y. (2020). The effects of compassion experienced by SME employees on affective commitment: double-mediation of authenticity and positive emotion. Manage. Sci. Lett. 10, 1351–1358. doi: 10.5267/j.msl.2019.11.022

Lilius, J. M., Worline, M. C., Dutton, J. E., Kanov, J. M., and Maitlis, S. (2011). Understanding compassion capability. Hum. Relat. 64, 873–899. doi: 10.1177/0018726710396250

Lilius, J. M., Worline, M. C., Maitlis, S., Kanov, J., Dutton, J. E., and Frost, P. (2008). The contours and consequences of compassion at work. J. Org. Behav. 29, 193–218. doi: 10.1002/job.508

Maratos, F. A., Gilbert, P., and Gilbert, T. (2019). Improving Well-Being in Higher Education: Adopting a Compassionate Approach in Values of the University in a Time of Uncertainty. Cham: Springer, 261–278.

Marginson, S. (2020). Public and Common Goods: Key Concepts in Mapping the Contributions of Higher Education. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Mickey, E. L., Misra, J., and Clark, D. (2023). The persistence of neoliberal logics in faculty evaluations amidst COVID-19: Recalibrating toward equity. Gender Work Org. 30, 638–656. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12817

Nielsen, M. W., Alegria, S., Börjeson, L., Etzkowitz, H., Falk-Krzesinski, H. J., Joshi, A., et al. (2017). “Gender diversity leads to better science,” in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences - PNAS. National Academy of Sciences, 1740–1742.

Nielsen, M. W., Bloch, C. W., and Schiebinger, L. (2018). Making gender diversity work for scientific discovery and innovation. Nat.re Hum. Behav. 2, 726–734. doi: 10.1038/s41562-018-0433-1

Nishii, L. H. (2013). The benefits of climate for inclusion for gender-diverse groups. Acad. Manage. J. 56, 1754–1774. doi: 10.5465/amj.2009.0823

Nussbaum, M. (1996). Compassion: the basic social emotion. Soc. Philos. Policy 13, 27–58. doi: 10.1017/S0265052500001515

Østergaard, C. R., Timmermans, B., and Kristinsson, K. (2011). Does a different view create something new? The effect of employee diversity on innovation. Res. Policy 40, 500–509. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2010.11.004

Özbilgin, M. (2009). Equality, Diversity and Inclusion at Work: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow. London: Edward Elgar Cheltenham.

Özbilgin, M. F., and Erbil, C. (2021). “Social movements and wellbeing in organizations from multilevel and intersectional perspectives: the case of the# blacklivesmatter movement,” in The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Wellbeing, ed. T. Wall (Cham: Springer), 119–138.

Özbilgin, M. F., and Erbil, C. (2023). Insights into Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion. Contemporary Approaches in Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: Strategic and Technological Perspectives. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited, 1–18.

Pan, S. (2020). COVID-19 and the Neo-Liberal Paradigm in Higher Education: Changing Landscape. Singapore: Asian Education and Development Studies.

Poorkavoos, M. (2016). Compassionate Leadership: What is it and Why do Organisations Need More of It. Horsham: Roffey Park.

Radice, H. (2013). How we got here: UK higher education under neoliberalism. ACME Int. J. Crit. Geograph. 12, 407–418.

Rapanta, C., Botturi, L., Goodyear, P., Guàrdia, L., and Koole, M. (2020). Online university teaching during and after the COVID-19 crisis: refocusing teacher presence and learning activity. Postdigital Sci. Educ. 2, 923–945. doi: 10.1007/s42438-020-00155-y

Rynes, S. L., Bartunek, J. M., Dutton, J. E., and Margolis, J. D. (2012). Care and Compassion Through an Organizational Lens: Opening up New Possibilities. Academy of Management Review. New York, NY: Academy of Management, 503–523.

Shen, P., and Slater, P. F. (2021). The effect of occupational stress and coping strategies on mental health and emotional well-being among university academic staff during the COVID-19 outbreak. Int. Educ. Stu. 14, 82–95. doi: 10.5539/ies.v14n3p82

Simpson, A. V., Clegg, S., and Pina e Cunha, M. (2013). Expressing compassion in the face of crisis: Organizational practices in the aftermath of the brisbane floods of 2011. J. Conting. Crisis Manag. 21, 115–124. doi: 10.1111/1468-5973.12016

Simpson, A. V., and Farr-Wharton, B. (2017). The NEAR Organizational Compassion Scale: Validity, Reliability and Correlations. Wollongong, NSW: Australian and New Zealand Academy of Management.

Simpson, A. V., and Farr-Wharton, B. (2017). The NEAR Organizational Compassion Scale: validity, reliability and correlations. Australian and New Zealand Academy of Management.

Simpson, A. V., Farr-Wharton, B., Cunha, M. P. e, and Reddy, P. (2019b). “Organizing organizational compassion subprocesses and mechanisms: A practical model,” in The Power of Compassion, eds. L. Galiana and N. Sansó (Nova Science Publishers, Inc), 339–357.

Simpson, A. V., Farr-Wharton, B., and Reddy, P. (2020). Cultivating organizational compassion in healthcare. J. Manage. Org. 26, 340–354. doi: 10.1017/jmo.2019.54

Simpson, A. V., Farr-Wharton, B. S. R., and Reddy, P. (2019a). Correlating workplace compassion, psychological safety and bullying in the healthcare context. Acad. Manage. Proc. 10510:16632. doi: 10.5465/AMBPP.2019.16632abstract

Simpson, A. V., Pina e Cunha, M., and Rego, A. (2015). Compassion in the context of capitalistic organizations: evidence from the 2011 Brisbane floods. J. Bus. Ethics 130, 683–703. doi: 10.1007/s10551-014-2262-0

Simpson, A. V., Rego, A., Berti, M., Clegg, S., and Cunha, M. P. e. (2022). Theorizing compassionate leadership from the case of Jacinda Ardern: Legitimacy, paradox and resource conservation. Leadership, 18, 337–358. doi: 10.1177/17427150211055291

Simpson, A. V., Simpson, T., and Hendy, J. (2023). Organising Compassionate Care with Compassionate Leadership in The Art and Science of Compassionate Care: A Practical Guide. Cham: Springer, 85–99.

Stellar, J. E., Gordon, A. M., Piff, P. K., Cordaro, D., Anderson, C. L., Bai, Y., et al. (2017). Self-transcendent emotions and their social functions: compassion, gratitude, and awe bind us to others through prosociality. Emot. Rev. 9, 200–207. doi: 10.1177/1754073916684557

Strauss, C., Taylor, B. L., Gu, J., Kuyken, W., Baer, R., Jones, F., et al. (2016). What is compassion and how can we measure it? A review of definitions and measures. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 47, 15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.05.004

Urbina-Garcia, A. (2020). What do we know about university academics' mental health? A systematic literature review. Stress Health 36, 563–585. doi: 10.1002/smi.2956

Waddington, K. (2016). The compassion gap in UK universities. Int. Prac. Dev. J. 6:10. doi: 10.19043/ipdj.61.010

Waddington, K. (2018). Developing compassionate academic leadership: The practice of kindness. J. Perspect. Appl. Acad. Pract. 87–89. doi: 10.14297/jpaap.v6i3.375

Waddington, K. (2021). Towards the Compassionate University: From Global Thread to Global Impact. New York, NY: Routledge.

Wallmark, E., Safarzadeh, K., Daukantaite, D., and Maddux, R. E. (2013). Promoting altruism through meditation: an 8-week randomized controlled pilot study. Mindfulness 4, 223–234. doi: 10.1007/s12671-012-0115-4

West, M. A. (2019). “Compassionate leadership in health and care settings,” in The Power of Compassion, eds. L. Galiana and N. Sansó (Nova Science Publishers), 317–338.

West, M. A. (2021). Compassionate Leadership: Sustaining Wisdom, Humanity and Presence in Health and Social Care. Sligo: The Swirling Leaf Press.

Wolbring, G., and Lillywhite, A. (2021). Equity/equality, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) in universities: the case of disabled people. Societies 11:49. doi: 10.3390/soc11020049

Wolbring, G., and Lillywhite, A. (2023). Burnout through the lenses of equity/equality, diversity and inclusion and disabled people: a scoping review. Societies 13:131. doi: 10.3390/soc13050131

Worline, M., and Dutton, J. E. (2017). Awakening Compassion at Work: The Quiet Power That Elevates People and Organizations. Oakland, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Worline, M. C., and Dutton, J. E. (2022). The courage to teach with compassion: enriching classroom designs and practices to foster responsiveness to suffering. Manage. Learn. 22:13505076211044612. doi: 10.1177/13505076211044611

Keywords: organizational compassion theory, equality, diversity, inclusion, higher education, wellbeing, suffering, COVID-19

Citation: Hashemi Toroghi H, Denney F and Simpson AV (2024) Cultivating staff equality, diversity, and inclusion in higher education in the post-pandemic era: an organizational compassion perspective. Front. Sociol. 9:1378665. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2024.1378665

Received: 30 January 2024; Accepted: 13 May 2024;

Published: 30 May 2024.

Edited by:

Maria Balta, University of Kent, United KingdomReviewed by:

Kathryn Waddington, University of Westminster, United KingdomCopyright © 2024 Hashemi Toroghi, Denney and Simpson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fiona Denney, ZmlvbmEuZGVubmV5QGJydW5lbC5hYy51aw==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.