- Sport and Movement Studies, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

Gender represents a confounding social construction within the multiple-layering of relative disenfranchisement in the Sub-Saharan context of poverty. Class and race play a significant role in the socialisation process, structures and policy frameworks that contribute to the perpetuation of gender inequalities in broader society and within different sport-related spheres. This paper draws on the conceptual insights of Marxian and Feminist approaches, socialisation literature and the understanding of the social inequality of condition, opportunity and capacity. It aims to reflect critically on the lived-realities of women in post-Apartheid South Africa to illustrate how ideology, culture, significant others, the availability of resources and democracy continue to shape the lives of women and girls. A discussion of policy frameworks, from the global to the local levels and experiences of how people “do gender,” are discussed. Main study data entails that from a 10-year review (1994–2004) on the status of South African women in sport and recreation and from three case studies linked to a sport-for-development 2010 FIFA World Cup legacy project. The latter entails the impact assessment of the GIZ/YDF (German Development Corporation Youth Development through Football) programme over a period of 7 years (2007–2014). Data were updated and re-interpreted in view of current gender discourses and public debates around gender inequality. Patriarchal ideology and hegemonic gender structures and practices continue to contribute to barriers women and girls face to participate in traditionally male sports and for gaining access to leadership positions. Enabling factors for addressing gender equality exist within the policy frameworks and human agency, where male gate-keepers filter access to gender inclusivity and empowerment. Gender inequality has taken the backseat to social transformation in post-Colonial contexts and should feature prominently on public agendas with mechanisms in place for monitoring and evaluating progress. It necessitates structural and systemic reform beyond current piece meal offerings and neo-Liberal initiatives to hold girls and women responsible for their own enlightenment and full participation in sport and society.

Introduction

Gender inequality is not merely an echo of political promises or rhetoric in the discourse of global “sport (for) development”—it is a stark reality in Sub-Sahara Africa that influences people in all spheres of their existence. Discriminatory effects based on gender parity in society, represent fluid and ever-changing realities embedded in socially constructed phenomena. Debates, discourses and statistical representations captured in indexes may send warning signals, but do not do justice to the complexity and diversity associated with gender inequality in real life circumstances. It does not inform global agencies and key stakeholders to what Messner and Musto (2014) refer to as the underside of the iceberg—in this case, the silence of voices that may articulate unique experiences often invisible to the gaze of sociological inquiry.

For instance, Maseko (2017) alerts society to gender inequality by referring to a widened (wage) equality gender gap across health, education, politics and the workplace from 2006 to 2017 as communicated by the Global Gender Gap Report (issued by the World Economic Forum). It further shows that 56% of all South African women's work is unpaid compared to 25% of their male counterparts (Maseko, 2017). Inter-gender comparisons, within the context of extreme poverty, come under public scrutiny when it affects the welfare of broader society. Gender equality is out of the reach of most impoverished households costing Sub-Saharan Africa's economy about $95bn annually (Anon, 2016). Inequality also finds expression in increased AIDS infections, teenage motherhood and child-brides that constitute circumstances associated with neglect and sexual abuse (Shisana, 2014; Rudman, 2015; Staff Reporter, 2017).

Confounded factors of poverty-related inequalities contribute to cultural patterns and the acceptance that 75% of poor girls from impoverished households are deprived of schooling (Suliman, 2017). Poverty is indirectly related to public and domestic violence (including rape) as expression of masculinity and control (Migiro, 2015). If men and women are considered to be of equal value (Ferreira, 2011), commissions, policies and influential actors are challenged to move beyond reductionist understandings of gender inequality (as in the case of economic feminism) (De Silva De Alwis, 2018), and address it head-on with agency (Mbete, 2017).

Addressing gender inequality and diversity in all its forms, including manifestations in sport sectors, may demonstrate spill-over effects or parallel systemic challenges evident in broader society. Closing the gender inequality gap remains on the global agenda and policy frameworks, such as South Africa's National Development Plan and that of the African Union 2063 that have limitations in addressing “gender equality and women empowerment in all spheres of life” (Ngwenya, 2016, p. 4). Policy statements and visionary perspectives may even distract from the complex layering of systemic disenfranchisement, particularly when following global trends reflective of Euro-American or Global northern domination (Saavedra, 2009; Cronin, 2011; Schulenkorf et al., 2016).

It is against the background of chronic poverty and post-Apartheid socio-political and economic realities where “race” is prioritised for socio-economic redress that this paper reflects on the perpetuation of gender inequality in broader South African society and as a discourse in sport. A national study as a reflection of women's positioning in sport 10 years after Apartheid (1994–2004), serves as core reference (Burnett, 2004), along with another regional sport for development study (Burnett and Hollander, 2013).

The nexus of gender, sport and development is problematised and guides substantiated arguments contributing to a constructivist view of how women and girls exert, challenge, negotiate or avoid agency as inherently part of society. In South Africa socio-political reform as part of a broader agenda of development and social transformation, contextual realities within the society, and particularly in sport spheres play out in a unique way. In contemporary South Africa, gender equality manifests as a complex and multi-faceted phenomenon within a society that is still highly unequal along racial and socio-economic lines.

Conceptual Framework

Scholarship grounded in the critical sociology, Marxian and feminist approaches has accrued legitimacy and praxis associated with influential socio-political movements since the 1960s. The language of equity and equality of social justice underpins a plethora of approaches across a diverse range of studies in the social and management sciences (Ahmed, 2007; Cunningham, 2008; Embrick, 2011). By problemising the discursive qualities of institutional habitus, critical scholars took a broader view of diversity work and thus brought new insights to the scrutiny of gender, racial and class inequality (Cunningham, 2015). Diversity and inclusion speak to institutional change in an open-ended way and inherently include conditions for the strategic distribution of resources to address inequalities, including those based on gender as factor for justification of social stratification (Rubin and Lough, 2015; Spaaij et al., 2018).

Equity is one of the key principles that alerts to resource allocation based on “contribution,” compared to equality where all groups or populations would receive the same allocation (Mahony and Pastore, 1998). Another principle entails “needs,” which considers the idea of relative allocation of resources to groups or collectives displaying patterns of differential access to resources thus bringing a corresponding sense of entitlement. Globally, it has been identified that men favour the principle of equity having had relatively more access to resources and power compared to women who generally prefer equality (Mahony et al., 2002). Similar sentiments are displayed by marginalised populations, such as lower classes, ethnic minorities and persons with disabilities.

Jarvie (2011, p. 95) argues that social inequality in sport constitutes: “(i) inequality of condition; (ii) inequality of opportunity and (iii) inequality of capacity.” Such social divisions are entrenched in competitive and colonial sport traditions, where hegemonic positions of ownership and resource access favour capitalist and more development economies. Unequal power relations are inherent in the phenomenon of “who” is sport rather than “what” is sport. Title IX pioneers in the USA, identified gender-minded leaders as the driving force behind legislative redress based on unequal access and opportunity in public sport spheres (Hardin and Whiteside, 2009). Individuals or organisations with political power are mainly responsible for the equitable distribution of resources. For change to happen, all dimensions of gender inequality should be addressed at all levels of engagement–from social relationships at the individual, organisational and societal levels (Burton, 1987; Sekot, 2011; Szto, 2015).

Doing Gender in Sport-Related Spheres

The notion of gender equality appears in international public policy within human rights, but in corporate governance policy the concept is framed as gender diversity with often stipulated targets, or a gender quota (United Nations, 2007). Such quotas or demographical representations characterise gender parity (for example, 40% as minimum level of representation) for the equal participation of all (men and women) (Whelan and Wood, 2012). The complexity of gender (in)equality in sport leadership goes beyond a scoreboard approach and requires multi-dimensional analysis of power relations (the number of female decision-makers) in addition to symbolic relations (creation of an ideology, culture and conducive environment favouring multi-levelled female engagement in sport) (Adriaanse and Claringbould, 2016). This multi-dimensional approach is also known as the gender regime which provides a systematic explanation of how gender works within an organisational setting (Adriaanse and Schofield, 2014).

Following the constructionism of approaches in the 1970s and strategic actions of counter-hegemonic of feminist movements, multiple constructivism emerged from the work of socialist feminism (Messner, 2011). Post-feminist focus on “choice” celebrates women's material roles and supports binary constructionism based on the biological differences. Multiple constructionism speaks to gender multiplicity and reveals a continuum of difference between men and women. It brings an understanding of why female athletes contest the traditional binary gender boundaries, such as in the case of Caster Semenya as an inter-sexed athlete (Kane, 1995). A social constructivist framework further explains gender identity formation that is fluid and self-selecting as girls negotiate their “web of selves” (Pielichaty, 2015, p. 493).

Late modernity brought progress in terms of increased elite sport participation for females as seen in the 2012 London Olympic Games where all competing country delegations featured female athletes (44% compared to 24% in 1984) (Capranica et al., 2013). However, such a superficial pre-post (Games) comparison, projects a distorted reality and does not expose the persisting systemic cultural and socio-political factors that limit the majority of females to access competitive sport. Similarly, a percentage comparative analysis of male vs. female National Olympic Board membership (83.4% males and 16.6% females) and that of International Sport Federations (82% male and 18% female) reveal little of real gender-dynamics and power relations (Jeanes et al., 2016; Lindsey and Chapman, 2017, p. 83).

Female-focused study provide a biased, but in-depth perspective. A baseline study on gender, participation and leadership in sport in southern Africa (Fasting et al., 2014) discloses the under-representation of women in leadership positions in national sport structures–one in five board members are women. The latter study also explored broader societal issues as barriers to full female participation that include cultural beliefs, family socialisation practices and stigma and safety issues. It is inevitable that beliefs, values and norms are acquired during socialisation when entering sport and through sport.

Socialisation

Gender, unlike sex (biological category), represents social presentations of the body that involves individual identity and social understandings or expressions in complex interactions, where masculinity and femininity are biologically demonstrated (Blank, 2012). The latter relates to the way individuals dress, behave and encapsulate social roles with stereotypical identifications of women being nurturing, intuitive, deviant and submissive compared to men and assumed superior masculine attributes (Connell, 2009). Through interaction and socialisation influences, individuals learn how their bodies and behaviours are situated according to existing cultural norms, which reinforces the subordination of “weaker bodies” associated with female physicality (Anderson, 2005). In such an assumption lies the perspective of a closed, unchanging world, but if viewed as a limiting situation that can be transformed, the creation of a more just dispensation is possible (Freire, 2012). If patriarchal ideology goes unchallenged, women and girls are complicit in their own oppression (Gramsci, 1971).

Connell's gender theory utilised by Eliasson (2011) explains the gender socialisation process as one in which children actively participate and accept or reject traditional notions of masculinity. Individuals behaviour should be understood from their perspective and reviewed as reactive to their own circumstances within the discriminatory systems they may find themselves (Messner and Musto, 2014). The consciousness of gender inequality is differently constructed and understood by boys and girls in various social institutions and contexts (Shehu et al., 2012). The local should be connected to the global in a meaningful way as to avoid disconnection. Similarly, different sport practices carry meaningful value propositions to address various nuances of gender inequality as cross-cutting issue (Burnett, 2013; Shehu, 2014; Cohen and Ballouli, 2016).

Structural inequalities in post-Apartheid South Africa facilitate and simultaneously impede the construction of collective (national and gender) identities and demonstrate the persisting dialectics of race, gender and class as divisionary and mitigating against a collective sense of sisterhood (Pelak, 2002, 2009). Socio-cultural barriers remain a pervasive theme in preventing equitable gender participation in structured physical activities for Xhosa-speaking women in the Eastern Cape Province (Walter and Du Randt, 2011). Ogunniyi (2013, 2015) conducted critical feminist research in the soccer domain and identified intersectional ideologies that inform socio-cultural and political constraints for women and girls despite sporadic agency and resistance.

Complementary to the influence of significant others and peers, female role models may serve as important social agents in identify formation as sources of inspiration and in challenging dominant gender norms (Meier, 2015). Inter-gender relationships and creating an environment and culture that breeds sensitivity to gender (in)equality may contribute to effective advocacy and meaningful change among males and females alike (Chawansky, 2011). Especially the development and exposure to female leadership send powerful messages out to legitimise girls' and women's role as change agents in a development agenda (Hayhurst, 2014). The sport-for-development sector is expected to provide more opportunities for addressing gender inequality due to the focus on civic society engagement and global donors driving such an agenda (Schulenkorf et al., 2016).

Sport for Development

Development work mirrors that of the formal sport sector in the sense that it constitutes layers of disenfranchisement for women and girls. Inequality comes layered from the domination of the Global Northern donors dictating the nature and parameters of development to the Global South as space of implementation (Coalter, 2013; Darnell, 2014; Burnett, 2015; Schulenkorf et al., 2016). Various mapping studies by Levermore and Beacom (2009), Cronin (2011) and Schulenkorf et al. (2016) addressed the issue of the bio-politics and Euro-American centrism in knowledge production and governmentality (Darnell et al., 2016, 136). Such political dominance comes with (neo)colonial and (neo)conservative logic “that tend to see social marginalisation or global inequality as a product of poor behaviour, bad policy or an inability to compete, as opposed to the ongoing historical fallout of colonialism or the collateral damage of mobile global capital” (Darnell et al., 2016, p. 136). As captured in neo-liberal understandings of development, the relative marginalisation of females in sport for development initiatives hold them responsible for their enablement, whilst ignoring significant systemic and ideological realities (Chawansky, 2011). For instance, girls may be taught about their rights of equal access to sport participation but face multiple challenges, such as having obligations of domestic work, lack of parental support and the financial means to travel to competitions or afford specialised coaching. The lack of robust research evidence and proven causality question the real sport-for-development effects and longitudinal impact thereof (Van Eekeren et al., 2013; Langer, 2015).

With the focus on research in the sport-for-development field, researchers often utilise critical approaches exposing issues of unequal power relations evident in women's subsidiary position in sport decision-making and leadership (Zipp and Nauright, 2018). The advocacy for a holistic paradigm in terms of investigating gender inequality provides a way for an in-depth understanding of how people “do” gender by adhering or rejecting gendered social norms. The conceptualisation of sport for development–a programme and legacy approach, centred on youth-centeredness (underpinned by Positive Youth Development) and earmarked for vulnerable populations as dedicated recipients of developmental aid (Coakley, 2011; Levermore, 2011; Burnett, 2013). Differential levels of vulnerability are associated with the relative marginal positions of implementing youth, and recipient populations, such as the HIV/AIDS infected and affected, refugees (Wisniewski, 2009; Waardenburg et al., 2018), as well as girls and women (Hayhurst, 2011; Van der Klashorst, 2018).

Sport for Development and Peace (SDP) scientific inquiry into gender draws on feminist theories and postcolonial (feminist) perspectives where the “girl-effect” emerged as a significant contributor to poverty alleviation and female empowerment in contexts of chronic poverty (Hayhurst, 2011). Female social entrepreneurs serve the interests of corporates and agencies in the development sector as they can provide (uncritical) support and penetrate untapped markets for global donors in their quest to feature female empowerment on their development agendas.

Authentic life stories and confessions of life-changing (often evangelical) experiences provide legitimacy to such sport for development marketing (Coalter, 2013). A longitudinal study on girls' empowerment in the Moving the Goal Posts programme in northern Kenya, demonstrates the relatively limited enduring effects of sport participation (Forde, 2008). Women's and girls' participation in sport may sporadically challenge gender inequality and various forms of discrimination, but are faced with layers of relative disenfranchisement as gender, (dis)ability, ethnicity and class intersects (Jeanes et al., 2016).

Gender on Global and National Agendas for Change

The devastating racial politics of the Apartheid era (1948–1994) has as legacy not only racial division and class divides, but it disproportionally affected women and girls situated at the bottom of the social scale (Fakier and Cock, 2010). The racial and class divides existed in all spheres of life and negatively impacted on a female solidarity despite gender inequality becoming a priority in post-Apartheid South Africa. Smith and Seedat (2016) discuss the legislative and political strides relating to: the Women's Charter that was adopted in 1994; the South African government ratified the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) the next year; followed by the approval of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (in 1997); and by 1999 about a third of the National Parliament comprised of women (Smith and Seedat, 2016).

Since the early 2000s, the United Nations' Millennium Development Goals set significant targets for addressing gender equality at the global level as captured in goal three to which governments became signatories (United Nations, 2007, 2010). The post-2015 era saw a continuation of the global development agenda captured by seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) where gender inequality is a cross-cutting them in addition to being specifically addressed by Goal 5 (Lindsey and Chapman, 2017). Multiple resolutions and strategic partnership configurations focused on the delivery of sustainable development by utilising sport, especially since 2005 following this declaration of the International Year of Sport and Physical Education (Beutler, 2008; Schulenkorf et al., 2016).

On 5 May 2010, the Inaugural Plenary Session of the United nations approved the Sport for Development and Peace International Working Group (SDP IWG), supported by the establishment of the United Nations Office for SDP (UNSDP) in Geneva (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation, 2017a). Endorsed by UN agencies and global stakeholders, the thematic working groups were tasked to lead, mobilise and monitor social change under the directives set out by the 2008 Report entitled: Harnessing the Power of Sport for Development and Peace: Recommendations to Governments (Beutler, 2008). These thematic areas include the utilisation of sport as a tool for addressing social transformation with relation to health, child and youth development, inequalities for women (gender), persons with disabilities and peace-building. South Africa's then Deputy Minister took a leadership role as rotating Chair of the SDP IWG and continued in that capacity, whilst also chairing the discussions at the 2017 MINEPS VI's (International Conference of Ministers and Senior Officials Responsible for Physical Education and Sport) meeting that contributed in the formulation of the Kazan Action Plan as the most recent pace setter for multi-party engagement (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation, 2017a). This plan proclaims that the empowerment of women and girls through sport should be an integral part of sport policies, good governance, a diversity agenda and peace-building as part of wider approaches and mechanisms to address gender equality globally and nationally.

The drafting of the Kazan Action Plan involved multiple UN agencies, influential partnerships and stakeholders (including the World Health Organisation, governments, corporates and NGOs). MINEPS VI featured a reconfiguration of stakeholder alignments after the UN's closure of the international office of SDP in Geneva in 2016, and the announcement of a direct partnership between the International Olympic Committee (IOC) with UN agencies (such as UNICEF and UNESCO) (Mann, 2017; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation, 2017a). UN-driven global initiatives also found pathways into the sport, education and health sectors for their advocacy and consultative work as evidenced in driving Quality Physical Education of which South Africa and Zambia are part of the four pilot countries (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation, 2015, 2017b; Burnett, 2017).

Mega-sport legacy projects often mobilise huge resources to address different societal issues. This was the case with the ambitious German Development Corporation's Youth Development through Football (GIZ/YDF) project that was rolled out to ten African countries during an extended time frame (2007 to 2014) linked to the 2010 FIFA World Cup hosted in South Africa (Burnett and Hollander, 2013). This project, like many other, favour football as a dominant male sport in a society where patriarchal ideology still informs major legislation and support systemic challenges for girls and women (Levermore, 2011). Gender inequality remains a thorny issue despite government legislation and policies targeted at closing gender-related inequalities. For instance, the National Sport and Recreation Plan (NSRP) incorporated a Transformation Charter that set benchmarks though a Transformation Performance Score Card and provide direction for addressing gender equality under the strategic Objective 23 with a broader focus on inclusion of marginal populations including women, persons with disabilities, youth, aged and rural communities (Sport and Recreation South Africa, 2012a). Whilst prioritising ethnicity and race as priority in an agenda of redress through policy and institutional reform driving resource allocation, the focus on gender inequality becomes an inherent category across a wide spectrum of development initiatives. Socio-economic inequalities relating to household and individual survival may disproportionally affect women as a vulnerable population, but is mostly seen as a nuanced manifestation of systemic disenfranchisement and poverty (Pelak, 2010). Only in cases, such as gender-based violence (GBV) where women are specifically identified as most vulnerable, would it become a social issue to be addressed by policy, structures and related practices.

Multiple stakeholders aligned themselves with government policies and directives by advocating and driving gender-related social transformation, although it is a relatively marginal social issue compared to race-related manifestations of poverty. The sport sector is of secondary importance compared to government departments dealing with social welfare, education and public health. Collective or institutionalised advocacy is rather lacking with the disbandment of a structure like Women and Sport South Africa (WASSA) in 2001 after only 5 years of its existence and when in 2003, the South African Women, Sport and Recreation (SAWSAR) became a sub-component of Equity with provincial representation within related sport and recreation structures, although the National Charter remained (Women and Sport South Africa, 2011).

Gender transformation in sport should thus be understood as a relatively less important government priority for redress and development (Jones, 2005). It does not make it less real or less discriminatory. For instance, in South Africa media sexist culture and male bias in the most prominent national newspapers promote masculine ideals in sport and athletic achievements (Goslin, 2008; Ogunniyi and Burnett, 2012). Relative limited opportunities for women to occupy leadership positions (as coaches, technical officials and administrators) were also challenged (Hargreaves, 1997; Jones, 2005). Low sport and physical participation and proportionally high dropout rates for women and girls were reported in national studies. In 2005, Rule and Struwig (2005) reported South African female participation to be 11.2% against a national average of 25.6%, and a male participation rate of 42.6%. Burnett and Hollander (2008), who conducted a baseline study for the School Sport Mass Participation Programme as a national initiative of Sport and Recreation South Africa to bring sport to the masses, found that girls were still marginalised in sport. However, the political framing of the Caster Semenya saga in resisting defined gender boundaries in sport, and the recent appointment of a female Sports Minister in South Africa, bring a different public awareness and praxis to the gender equality discourse.

Taking this discussion to the real-life worlds of women and girls, data from two main studies of national and regional scope within the sport sector will be discussed. The first national study was the first of its kind and provide an in-depth understanding of how girls and women constructed their participation across sport sectors, 10 years after a new political dispensation was established (Burnett, 2004; Sport and Recreation South Africa, 2012b). The results were not exposed to academic scrutiny due to a volatile political climate in which public universities found themselves. Fifteen years later, the findings are still very much relevant due to slow systemic changes. The other study relates to the GIZ/YDF project which significantly contributed to the mobilised resources and civic society actors to address multiple levels of disenfranchisement in the sport sector. It contributed to the establishment of the Sport for Social Change Network (SSCN) and assisted with institutionalising the philosophy of sport for development and gender issues within Sport and Recreation South Africa (Burnett and Hollander, 2013).

For this paper, two studies in which the author collected and interpreted the primary narrative data are re-interpreted in view of emerging discourses and public debates relevant to contemporary issues of gender equality that persist within South African society and sport. The emerging discourses particularly focus on the demystification of female empowerment and exposing the rhetoric if it is not followed by tangible results of policy implementation. For instance, the unequal representation of women holding political and economic power in improving the status and professionalism in traditional female sports, like netball exacerbated to relative limited media exposure for female athletes, are issues of public debate. Such issues have persisted for many years as evidenced in the 10 year review entitled, The Status of SA Women in Sport and Recreation 1994 to 2004. From the GIZ/YDF study, three case studies of women who were life skill coaches, will be discussed so as to gain insight into their social worlds and the role sport plays in their daily existence (Burnett, 2012). In the latter study, the selection of cases demonstrate the complexity of real life situations within the context of South African township poverty that affects households and individuals in a profound way and provide women with limited options to demonstrate agency.

For both studies ethical clearance was obtained from the Ministry of Sport (SRSA) and for the latter study, ethical clearance was also obtained from the GIZ/YDF Executive Board which included copy-right sharing. In both cases proposals were submitted that included a literature review, document analysis research questions and methodology, as well as ethical considerations, ethical conduct ascribed to and consent forms to be signed by all research participants for the completion of a questionnaire, being interviewed or being part of a focus group discussion. The relevant authorities approved the proposals and were satisfied with the ethical aspects. For the GIZ study, several impact assessments were preceded by abbreviated proposals and in all cases the GIZ executive board expressed their satisfaction with the high ethical conduct of the senior researchers. All consent forms were filed and could be called up for follow-up with certain research participants without their names be used. For narrative material, these research participants agreed to their stories been mediated and they chose tier own pseudo names. Both written and informed consent was obtained from all adult research participants and from the parents or guardians from all non-adult research participants. In all research matters, strict academic ethical guidelines were implemented to ensure anonymity, safeguarding and respect for research participants, multiple triangulations, Participatory Action Research methodology (using the S∙DIAT) and validation of findings (Burnett, 2004, 2012).

Research and Evidence

A 10 Year Review

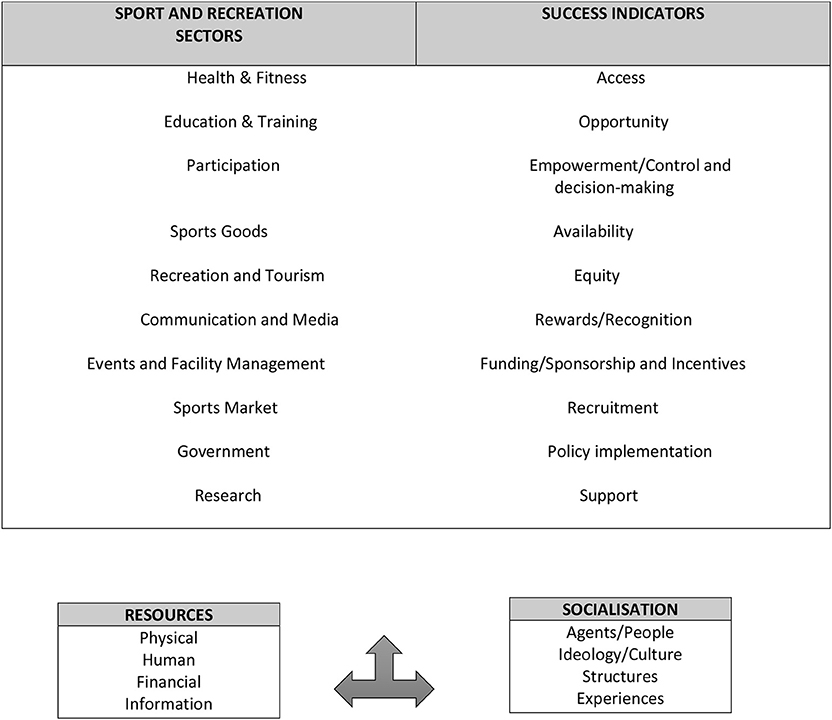

The rationale of the review drew on the prescribed success indicators of the Synthesis Report of Government Programmes that was issued by the Presidency in 2003 (Burnett, 2004). The study aimed at assessing macro policy frameworks, programmes and to establish how girls and women “do” and are affected by “gender.” The findings still have much relevance in current public discourse about gender in sport and will be reflected upon while considering retrospective (post-Apartheid) realities and expectations. The methodology entailed interviews with 488 decision-makers, leaders, practitioners and athletes across all sectors as a purposive sample identified by representatives of multi-levelled government structures. Of the selected sample, 356 were interviewed (with interviews lasting between 40 and 60 min), 132 participated in focus groups, of which 123 also completed a questionnaire. The mixed-method approach enhanced the explorative study and captured trends with nuanced experiences relating to gender-related experiences and reflections (Hesse-Biber, 2010; Sparkes, 2015). Figure 1 illustrates the selection of representative research participants from national to local levels and components informing the 10-year review study.

Figure 1. Components impacting on experiences of women in sport and recreation sectors (Burnett, 2004, p. 6).

The complexity and scope of the study rendered four overarching themes that provide high levels of integration between the data sets. These themes mainly relate to: (i) ideology and cultural influences; (ii) people of influence; (iii) resources and equality of access; and (iv) democracy–expectations and reality.

Ideology and Culture

Ideology and culture played an overarching role in the socialisation and creation of opportunities to play sport competitively, take up a leadership position or enter into a sports-related career. Most women who excelled in sport or entered a sporting career, were supported within social institutions like sport clubs, the school and at household level where they received encouragement and recognition. Most successful female athletes and team players in traditionally female sports (like netball or tennis) experienced enabling cultural influences, whereas most successful females in traditionally male sports (like soccer) resisted patriarchal ideology and were criticised, discouraged and, in some cases, stigmatised. In some cases, women reflected on the status quo of sport being recognised as a predominantly male activity, whilst even leaders in the field had to obtained permission from traditional leaders in rural areas to motivate parents to allow their daughters to take part in sport. Selected narratives articulate parental involvement, socialisation influences, cultural norms and contextual realities bearing on female participation in sport and recreation:

Parents don't like their girls to play soccer. When they play soccer, you can see behavioural change, they behave like boys. They walk like boys and pull their trousers down. They cut their hair. This also put other girls off from the sport. (Sport Manager from Mpumalanga)

In our culture they will tell you female runners will not have children in future. (Athletic Coach from Limpopo)Personally as an athlete, I did not experience cultural hindrances, but as an administrator, I had to dress “appropriately” (long dresses and head gear) to plead with traditional leaders to “release” girls to participate in sport. (Manager, Representative from a National Organisation, Burnett, 2004, p. 23)

An individual is mostly socialised into sport by significant others within various social institutions which exert a positive, negative or no influence. In more traditional cultures or environments dominated by patriarchal values, heterosexual (gender) identity markers are enforced and carry significant gender symbolism that inform acceptable norms for directing behaviour. Most married women felt trapped in a domestic role and the norm of nurturer at their homes and in the work place. One educator and researcher from the Western Cape said: “It is not access to resources that poses a problem, but the ability to take advantage of the opportunities due to gender role responsibilities at home and also the way female staff often have to assume the nurturing role” (Burnett, 2004, p. 46).

People of Influence

As previously indicated, primary caregivers, teachers, coaches and peers (significant others) are most influential influences in socialising girls into and through sport. For successful female athletes, male and female mentorship and support need to be augmented by enabling structures, as well as a supportive cultural and physical environment. Star athletes as role models are considered less important, although may be inspirational, particularly if the person is from the same background or challenging life circumstances.

Availability and Access to Resources

Physical resources is most important for taking part in sport and structured forms of recreation. This entails the availability of adequate (number and quality) infrastructure and equipment. For sporting success and talent development, qualified coaches and accessible coaching (human resources) are essential. Then, material resources and finances, as well and access to information and knowledge are equally needed for sport participation and an active life style. Limited free time and opportunity were key limiting factors on girls' access to sport. Older boys and male teams mostly dominate community facilities and are favoured by management in scheduling their sport matches as a priority.

Many women indicated that exiting facilities are not female-friendly or cater for women's needs in terms of safety, privacy and child care. Narratives relating to these issues include:

Girls have to undress in front of the male coach or in the bus before the games. This is not acceptable. (Sport Coach from Limpopo, Burnett, 2004, p. 46)

Physical resources still do not cater for the safety of women, as well as child care facilities. (Sport Manager from KwaZulu-Natal)

Most women and girls (65%) indicated that they have relatively less access to financial resources than men, which disadvantages them to access career opportunities in sport, sponsorships, equal recognition and rewards, and income. A national female race walker from Gauteng related her experiences where she received less prize money than her male counterpart, despite the fact that she beat him in a race where women and men raced together over the same distance. The unequal distribution of access empowering of human resources in different sport sectors, contributed to relatively less access than men to decision-making roles concerning coaching and leadership, career advancement in different sectors and being recognised as role models.

Women view the public media as key normative influence in perpetuating patriarchal ideology and gender stereotyping. Interviewees from the media said that national media houses are reliant on their international counterparts for news stories and pictures relating to international competitions and star athlete performances. The male bias in the media is however perpetuated by national media communication and exposure in addition to a public space that is represented by male staff and decision makers upholding patriarchal values.

Democracy: Expectations and Realities

For the individual, “democracy” implies that s/he will experience “freedom” in having choices and expression. Most women did not experience significant inroads being made on addressing gender issues in sport. Research participants from African, Coloured and Indian decent had mixed expectations with the realisation of having more opportunities available to them in different sport sectors, but also continued to be hamstrung by male dominance and socio-economic realities. Women were largely ignorant about how they are disadvantaged from the policy to implementation levels in the field of sport. The lack of agency and frustrations are largely communicated in an ad hoc and uncoordinated way that minimises the collective and negotiated agency it might have on a more democratic dispensation. Most were sceptic about policy implementation and the transparent monitoring of progress.

Sport for Development: GYZ/YDF Case Studies

Burnett (2012) publication, Stories from the Field, includes 45 case studies of players, administrators and participants who were part of the GIZ/YDF programme that was implemented in ten African countries. For this section, stories of three female coaches or peer leaders were selected to illustrate how women constructed their sport involvement within their social worlds. All cases were abbreviated for this paper and mainly feature their own experiences and sense-making. Pseudo-names (*) were selected to ensure anonymity and represent real life experiences of women in similar positions in the contexts of poverty within South African townships.

Lerato* was a youth leader and coach for a Pretoria-based Non-Government Organisation (NGO) active in the sport for development space. In 2007, she was 19 years old and lived in a township within the larger Pretoria Metropole. Her household members consisted of her twin sister, three brothers and her parents. During the research period she played competitive soccer and saved money to study sport management. The family migrated from the Limpopo Province to the township and afforded her a relatively care free life consisting of much outdoor play and regularly playing soccer in the streets or open areas with her siblings and their male friends. Her sister remembers that:

…the boys did not like us playing soccer, but because they played a lot with our brothers and were skilled players, we were accepted. Some boys would say: ‘Wow! That's why you want to play, because you're good!' In the beginning, our father did not like us to play soccer. We (my sister and I) have always been active in playing soccer together and were socialised with boys as “soccer players” (Burnett, 2012, included CD, story 10 Lerato, South Africa).

Lerato explained:

‘We mostly played against boys which made us very good players. In the beginning we lost and could not keep up with the boys then we founded a Ladies team. There were only four girls in the team and the rest of the team members were boys. The coach was firm and did not want to change the team, but wanted to develop girls and boys. The boys did not like the name, but they could not change it (Burnett, 2012, included CD, story 10 Lerato, South Africa).'

Over the years, the two sisters became were very active and played for a team in their local community. It was the coach of this team who introduced them to be peer educators at the local NGO. They felt passionate about working in the community and acting as role models to younger girls. Having joined the NGO as youth leader and coach in the GIZ/YDF programme, Lerato was selected to represent South Africa in a street soccer tournament in South America. She explained:

I got training and I was chosen to go to Paraguay. I was not necessarily the best player, but they took me for my leadership qualities and personality. It was a sad moment for my sister, as she could not come along. I did not tell anybody and only told my mother after two days after an evening meal. During the week in South America, I got to talk a lot about my community and my country. It changed me and I realised that I can be somebody in sport. I was not shy anymore and could speak in front of people. Even now, I can just start talking to somebody that I do not even know (Burnett, 2012, included CD, story 10 Lerato, South Africa).

Lerato enthusiastically talked about her role as youth leader:

I love sitting down with the kids and talking to them. I love bringing smiles to their faces and then ask them what is wrong with them if I see that they are sad. Some do not have easy lives. I would also tell them how people made fun of me, calling me a lesbian just because I was playing soccer (Burnett, 2012, included CD, story 10 Lerato, South Africa).

For Lerato being stigmatised as a lesbian did not bother her too much as it was common for them to be called such names. What was a concern for her, was that girls who had a different sexual persuasion hit on her and her sister. The opportunities and exposure facilitated by the NGO were particularly meaningful and contributed to her journey in life. She explained:

GIZ gave us opportunities to travel and to attend short courses. We trained how to deal with journalists and many of them interviewed me during the World Cup. I attended various panels and did some public speaking (Burnett, 2012, included CD, story 10 Lerato, South Africa).

Personal development and social recognition associated with status-conferring experiences, provided Lerato with aspirations, skills and competencies that steered her on a path of self-discovery and upward social mobility.

My work with the NGO* (identifiable identity omitted) afforded me lots of opportunities. I have been given so many experiences to develop personally. Last year I was sent to Germany, where I attended a seminar on how to follow one's own path of development. GIZ gave us opportunities to travel and to attend short courses. We trained how to deal with journalists and many of them interviewed me during the World Cup. I attended various panels and did public speaking (Burnett, 2012, included CD, story 10 Lerato, South Africa).

In 2008, Nkosozana* was a coach for a NGO in Khayelitsha, a township in Cape Town. She was born in the Eastern Cape, and like many Xhosa families, her parents had moved to Cape Town in search of employment. In 2009, this 24-year-old advanced to a management position in the NGO structure. As she had a troubled relationship with her father, her mother was always looking out for her safety in Khayalitsha. She remembers:

I came to live here in Khayalitsha when I was two years old. I was the only girl and was always surrounded by boys. The primary school closest to home was a 45-minute walk away. It was not safe to go there alone. Once I was harassed coming back from school so I got an ‘older brother', James, to walk with me and protect me (Burnett, 2012, included CD, story 3 Lerato, South Africa).

Nkosozana who is from Xhosa descent, at first found it difficult to adapt in a predominantly “Coloured school” in a Cape Town township, but she found her feet and took up a leadership position as a prefect. What she found challenging, was to deal with an abusive father which affected her to become quiet in her final primary school year.

My father was abusing my mother and he was hitting her so that she had some miscarriages. I felt I could not speak to anyone and felt side-lined. In 1999, I was sent away to live with my aunt and only got back on Sundays. My little sister was born, but my father would not stop. One day he was hitting me and my mother when my little sister came into the room, asking us why he was hitting us. I felt so very ashamed as I did not want her to see this. I started hitting back at my father and took my sister… It went on and on, and my father only left us when I was in Grade 11. He moved everything out of the house (Burnett, 2012, included CD, story 3 Nkosozana, South Africa).

Her personal circumstances and troubled home environment ruined her changes to study further after school as she needed employment to assist in taking care of her household. Her father abandoned the family and there was not enough support from her extended family or from her mother to provide the essential material resources.

In Grade 11, I got very poor marks, but I managed to pass Grade 12. After that, I went to the Oval International College to study business management. But after six months, I fell ill and I didn't have money to continue as my uncle could not afford it anymore. My mother was selling sweets to send me to school, but I didn't want to take her last money. I just wanted to find a job) (Burnett, 2012), included CD, story 3 Nkosozana, South Africa).

The earning of a R2,000 stipend from the NGO, afforded her an avenue to financially contribute to the household's survival–she considered it as a “God-send.” Just as valuable, was the respect she received being an All Star coach and Life Skill manager. She was highly regarded by programme participants, peers, the NGO staff and community members. Her uncle recruited her as a coach and over time the organisation became a safe haven where her “troubled life” could be shared and where she could find meaning and compassion. She explained:

In 2006, my uncle who was a coach at a local NGO* (name omitted), recruited me also as a coach. At first I didn't like working with kids, rather wanted to hit them. Yet I stayed as a volunteer and soon I started appreciating it (Burnett, 2012, included CD, story 3 Nkosozana, South Africa).

I had a sense of belonging at work and a sense of home. I got fully involved in the community through the girls I was coaching. I wanted to plant the seed in their lives so that they could face the challenges. I wanted to be that someone for them. I wanted for them, like it was for me, to move into that other zone, to cope (Burnett, 2012, included CD, story 3 Nkosozana, South Africa).

Later, Nkosozana was trained as YDF instructor, so that she could train other coaches. In 2013, Nkosozana still loved working with children and found such satisfaction to “share her life” and having a meaningful engagement with young people. She said:

At the programme* (specific name omitted), we develop the personalities of coaches and peer-educators. The participants acknowledge and listen to us. They come to us with their problems and then trust us–we found common ground as the coaches are also from the community. Some kids do not want to go home after practice, there is too much abuse at home and then they find they cool down at our activities (Burnett, 2012, included CD, story 3 Nkosozana, South Africa).

She excelled in her roles at the NGO, and through the YDF programme she was invited to travel abroad and represent her community, organisation and programme. She appreciated the opportunity to grow and be recognised because of her hardships and the identity that she created for herself. Her popularity in the community also aided her mother to begin an Early Childhood Centre at their home and afforded them the opportunity to earn a monthly income.

During the research Thoko* was 23-years old and acted as a peer-educator/coach for a local NGO in offering sport and life skill programmes to schools in the Elizabeth township and adjacent areas. In 2009, she had lost her parents and lived with her sister in KwaZakhele (a township in Port Elizabeth). At that stage she and her sister both had several children for whom they had to provide for.

Thoko's mother provided for the family and contributed to them enjoying a rather care-free childhood. One of her friends said that when Thoko's father committed suicide, she changed from being carefree to becoming withdrawn and depressed. The family faced extreme poverty and both sisters engaged in (sexual) relationships and found odd jobs to earn some income. They moved in together to pool their resources. Life became more complicated when Thoko's sister tested HIV positive and put on antiretroviral medication. Afterwards, she regularly attended a support group and could assist Thoko when she contracted AIDS. Although they are stigmatised by some community members and tried to cope with the situation by becoming AIDS Counsellors. Thoko explained:

My way of teaching children is to introduce myself and tell them that I am HIV positive. We call it ‘The Coach's Story'. At first they are surprised but then they realise that I can teach them better because I am in this position–it encourages them to share their problems. The kids often tell me about rapes. But they just want to share, they don't want anything to be done about it (Burnett, 2012, included CD, story 3 Nkosozana, South Africa).

Although survival was a struggle, Thoko and her sister found comfort and support in the inter-dependence of community life where people looked out for each other. It is explained by a philosophy of Ubuntu where people are tied into reciprocal care and a common destiny. Many people are very poor, which leads to crime and alcohol abuse. People need to cope, families are broken and children neglected causing young boys to drink at shebeens (taverns) and girls to find “sugar daddies” who can pay them for sex.

For Thoko being contracted to implement the GIZ/YDF programme meant an increase in earnings as she had to live on a meagre stipend as volunteer at another local NGO during 2008. Since working at the new NGO (where she is still on contract in 2018), she retained her responsibility to ‘oversee other coaches to make sure that they keep up with the programme'. She also implemented a Training of Trainers course for other organisations in order to spread the YDF approach. She really likes the programme as “you can be your own person and they do not push you–they let you do your job without pressure.”

The greatest benefit for her is that she acquired special knowledge about HIV and AIDS, as well as a new methodology. She also engages with international volunteers who delivered sports coaching at the NGO and could assist them. She was popular. On one occasion, they even collected funds for her to pay for the medical care of her child. Her sister said that her position at the NGO made her more responsible and she would be consulted at all hours of the day by children from the community where she works.

Irregular income from the NGO she worked for necessitated her to look at other informal ways of earning money, such as managing a netball team to perform traditional dances at weddings and informal trading. Being an attractive woman and a single parent to two young children led to her continuous search for a prospective husband. One of her young girls has rickets and she was told by a local doctor that medical treatment, which she could not afford, is only available in Cape Town. In 2016, she had a (sexual) relationship with a man from East London and when she fell pregnant, he left her. She said:

…he did not show interest to marry me. Now we are just friends, but I did lose face in my church for becoming pregnant. I could not continue singing in the choir with my big tummy. I want to change my life around, but still dream to find somebody to look after me and my children (Burnett, 2012, included CD, story 3 Nkosozana, South Africa).

My sister has to live with us, despite having a boyfriend. Now I have three children and I have to be a responsible mother. I am still working for the NGO and I know they want to get rid of me because I am not an example to others, but I will not give them the opportunity to fire me. I need to keep the job … what else will I do? (Burnett, 2012, included CD, story 3 Nkosozana, South Africa).

From a conversation with a friend, it became clear that Thoko is respected and her advice is highly regarded in managing troubled relationships or resolving conflict. Her friend explained:

Thoko is good at motivating children. She gives them healthy advice. She also gives me advice, even though I am older. I will fight with my brother and then there will be a bad relationship. She will give me advice on how to handle him and after not talking to each other for a week, we will make up. She is wiser than me (Burnett, 2012, included CD, story 3 Nkosozana, South Africa).

From the three case studies, the emerging themes speak to relative levels of poverty, which by far supersedes the issue of being a female of embodied physicality. The lives of Nkosozana and Thoko are filled with a threat of male violence and finding ways of resisting it and surviving. For both, the NGO provided the opportunity and space to bond with others, act as role models and find respect and appreciation. The role of “coach” is status-conferring and meaningful as they find themselves in a position to share their experiences, make sense of their own lives and demonstrate agency. For the young Lerato, entrance into traditionally male sports (soccer) carries a stigma and opposition from parents, compared to activities where girls opted for an NGO position to serve the community. Female coaches showing high levels of altruism are respected as they do not challenge broader patriarchal values. Women earn the respect of the wider community if they can successfully negotiate the survival of their households and dedicate themselves to care for others. Resistance comes with significant change when a father or partner is rejected under circumstances with few other options for survival remaining. In the following section the results from both studies are discussed. It is not so much a common sisterhood, but creating bonds of reciprocal care referred to as a philosophy of Ubuntu (I am because of other people). Insight is provided into the barriers and limitations, and existing opportunities, but as illustrated by the research findings and case discussions, the scope and agency in addressing the ways of women doing gender are overlaid with complex identities, cultural expectations and realities.

Barriers, Limitations, and Opportunities

Barriers and Limitations

Barriers are mainly viewed as ideological and institutional factors that are highly entrenched in norms, values and cultural expressions and supported by existing male-biased philosophies, structures and practices. Sport as a male preserve seems to be a global phenomenon (Anderson, 2005; Messner, 2011), which to some extent mirrors the engendered meanings and spaces of sport in southern Africa (Fasting et al., 2014). Limitations are not universally experienced and nuances of social transformational actions are possible as challenges present in an open-ended way as potential pathways on a continuum of possibilities (Freire, 2012). For many women, resistance is possible if they are in a leadership position, such as Lerato's coach who established a Ladies team or Nkosozana whose popularity in the community drew children to her mother's Early Childhood Development centre.

The construction of the social worlds of the women and girls in the different settings, constitute in some sense parallel universes. The one social world exists in a more formal, legalised and recognised institutional environment whilst the other constitutes a fluctuating informal space, where doing gender translate into different behaviours. For young girls, it means access to play with boys and gain physical skills. For others, it means being elected into a leadership position within different spheres of influence, although such mainstreaming of gender, inevitably disadvantages females as it takes place in engendered spaces (Connell, 2009; Chawansky, 2011; Ogunniyi, 2013, 2015). The research findings reflect how females can mobilise support in the broader community by capitalising on her role as coach and “community builder” by teaching life lessons to children or providing emotional support.

Socialisation influences are paramount in the formation of a gender identity. The internalisation of the norms and values are often a prerequisite for acceptance at inter-personal, institutional and community levels. Pielichaty (2015) refers to creating a “web-of-selves” with reference to how girls present different versions of themselves according to circumstances and relationships, which they negotiate for personal gain. The traditional and contemporary South African society is ideologically positioned by patriarchy. From a very young age, girls are coerced through stigmatisation (being labelled a lesbian) or violence (not being safe) and marginalised (not having the same access to public sport facilities) as systemic barriers (Hayhurst, 2011; Messner, 2011). They are co-creators of such a culture of disenfranchisement. Gramsci (1971) argues that such enfranchisement comes with their silence and inability (including capacity) to exert individual or collective agency. Jarvie (2011) argues that multiple layers of gender inequality could be explained as females are disadvantaged with relation to conditions, capacity and opportunity, which presents as inter-related factors and have a bearing on identifiable needs.

The engendered physicality and heteronormativity firstly allows girls to associate and play (particularly soccer) with boys, where fathers and or other boys are the gatekeepers. When they perform well, they are accepted, but if not, they are rejected and have to find an alternative. Such as in the case of the twins (see case study of Lerato) and then as professional positioning (manager asking permission from traditional leaders) or connectivity (knowing an NGO) may broker continued participation or provide access to income-generation. The level of powerlessness articulates with opportunity (male/status broker), capacity (collective action or support from female siblings and/or mother) and conditions in which women and girls find themselves (Chawansky, 2011; Jarvie, 2011).

Neo-liberal understandings and a common sisterhood has little meaning for girls and women, who are mainly viewed as “possessions” for men, who would side-line them as players to the role of spectators, act violently, dismiss their needs and use them as “tokens” to adhere to gender targets. Such an interpretation confirms the viewpoint of patriarchal dominance and how male hegemony is exerted through the production of power (Sekot, 2011; Szto, 2015). Unless men and women take up equality and human justice as a societal and institutional value, patriarchal beliefs and “equity” will ring hollow, favour men (and merit) with public confirmation from media portrayals. The latter does not only under-represent women and traditional female sports, but filter and manipulate content from the global to the local that perpetuate gender discrimination (Goslin, 2008; Ogunniyi and Burnett, 2012).

Fathers and men mainly act as gatekeepers for women and girls to access public (sport) spaces as players, coaches, managers and activists (Kidd, 2014; Zipp and Nauright, 2018). Male role models are considered symbols of superior sport performers, whereas mothers and sisters or local sport females carry the signified marker of “people like us.” Altruism and compassion from women and acting as role model to less privileged children is status conferring, but adhere to the gender script of society (Forde, 2008; Ogunniyi, 2013). The peer leaders found relative empowerment and acceptance by sharing their stories of survival and as such, claim heroin status, but for women in organisational settings they find themselves in a position to act as trail blazers for gender rights, but refrain from it as they are challenged to secure their own positions (Jeanes et al., 2016). Leadership is mostly associated with masculine characteristics with males being associated with decision-making power and styles of leadership.

In the aftermath of Apartheid, “race” became the dominant face of redress and the struggle for freedom from poverty as the agenda for social transformation. Women of Colour could hardly do battle at both fronts (socio-economic and politically) and thus opted for first being a black person and then considering the issue of being female (Pelak, 2002, 2009; Walter and Du Randt, 2011; Ogunniyi, 2015). The public space constitutes a political forum for human rights in the same way as competitive sport occupies the public domain. The latter became a space of collective struggle and relatively agency for women speaking out, as in the case of the female race walker beating a male athlete but receiving less prize money. The public space remains a hostile environment for women, where they are permanently under the male scrutiny and surveillance–from being safe, having access to change rooms or self-selected feminist appearance and behaviours that would aid their chances to become wives and mothers (Chawansky, 2011; Jeanes et al., 2016).

The most severe obstacle for girls and women remain their socio-economic status encompassing the level of material dependency on fathers and husbands or partners. Female athletes are disadvantaged because of not being able to access a sporting career in sports like rugby, football and cricket that offer professional opportunities for multiple vocations (Ogunniyi, 2013). Layers of social stratification for females is aggravated by being an incomer to a community (a Xhosa in a Coloured school), being young (daughter to stand up against an abusive father) and having to survive and as such using connections (to start an ECD centre) or enter into sexual relationships (Hayhurst, 2011; Walter and Du Randt, 2011; Van der Klashorst, 2018).

Opportunities

Global influences emanating from the sustainable development goals, feminist movements and the Kazan Action Plan, alert decision-makers to gender issues and profile possible change. Especially at community level, civic society organisations (NGOs) implementing sport programmes provide an enabling space for women to find a social home, acceptance, peer support and elicit community respect for their agency to resist abusive male relationships and destitution. At the other end of the spectrum of sport, being competitive and elite, sport powerhouses, like the IOC and FIFA, would provide opportunities for girls to enter and reap the benefit of sport participation, but their approach and structuring of (relatively more) equitable gender participation dislodge entrenched institutional barriers to select, promote and empower women (Lindsey and Chapman, 2017).

Placing “gender” on the agenda for social transformation is already supported by legislation and the liberal policies where women's rights are acknowledged (Hardin and Whiteside, 2009). The change from Apartheid to a democratic dispensation provided opportunities for empowerment for the previously oppressed with redress focusing on pro-poor and gender liberation. It is not possible to homogenise the complex and overlapping experiences of women given the high level of existing diversities. To a certain degree, it is more difficult for uneducated and rural women living in poverty to access resources that would address their socio-economic and political vulnerability. Institutional reform in different sport sectors may open up somewhat more opportunities for women and girls to gain access to funding opportunities and recognition, but they still need to be able to access such opportunities. For the relatively more socio-economically fortunate, women of African descent in post-Apartheid South Africa could trade on their identities of “race” and “gender” to access leadership positions in various sport sectors.

Educating and sensitising the media, men and women in decision-making positions (from the institutions of power inside and outside the direct sporting sphere) are crucial to change perceptions and set examples for gender-mindedness and breaking down stereotypes. If “gender” continues to be viewed as a female rather than a societal issue, institutional barriers and hegemonic practices will remain in favour of patriarchal biases. Finding mechanisms to break down the barriers between women from different spheres of life so as to create the formation of a common sisterhood, may present a related and more concerted collective voice and public exposure for addressing a pro-gender equity agenda in society and within the sport sector (Pelak, 2009; Sekot, 2011; Szto, 2015). In South African society that is still riddled with multiple layers of disenfranchisement, “race” and “socio-economic status” trumps that of “gender” as it affects the majority of people living with the dehumanising and devastating consequences of poverty. Having access to formal sport participation or leadership, constitute a more public arena for showcasing pro-gender policy frameworks and practices.

In elite sport, female role models like Caster Semenya and successful national all-female teams open pubic debates on gender equality in different ways than that which happens at grassroots level. For instance, in the informal sport for development sector, women are granted the opportunity to find a social home, psycho-social support and experience enhanced status in their communities. Recognising them first and foremost as women, who not only take responsibility for their families, but also serve as role models on how to survive and earn respect in their community (as in the case of Nkosozana and Thoko) (Ogunniyi, 2015). Such recognition is liberating for women who have experienced extreme levels of abuse and marginality, but it also provides them with a purpose in life of servitude (Forde, 2008). Their resistance against male oppression and structural poverty is perceived differently. Sport is a factor in their own and partially in their community's development, but the identity markers are different for women and girls in more affluent circumstances (Jeanes et al., 2016).

Extreme poverty is a great (gender) equaliser. Both men and women are in need of employment or income-generating opportunities. These may serve them more meaningfully than expecting them to oppose structural barriers successfully (Van der Klashorst, 2018). From research evidence, it seems that the first level of social transformation (and liberation) lies in addressing high levels of poverty and associated structural barriers that perpetuate such class inequality. Unequal power relations and hegemonic practices are also evident in keeping the poor in “voluntary coaching roles” despite paying them a stipend for services rendered (Levermore, 2011; Darnell et al., 2016). In the sport-for-development sector, donors should be responsive to the needs of implementers and see them as direct beneficiaries of programme effects rather than in a mere implementing capacity.

Reflection

Gender inequality is a complex, multi-faceted and a multi-levelled phenomenon that needs society in all its sectorial linkages–from the global to the local. It is a global and societal issue that will take time to dislodge from invested male hegemonic practices and structures that are reaffirmed daily in public spaces underpinned by patriarchal ideology. By addressing human justice, women may be treated more humanly in spheres where they struggle to survive. Only when women are afforded the same value as their male counterparts may they join the boardrooms and sport pitches in a more equitably way.

Researchers have a role to play in the dissemination and packaging of research results that will expose gender inequality as a societal issue and advocate for social change. Promoting, publishing and understanding the co-writing of authentic stories may be a mechanism in making women's plights heard and understood (Burnett, 2012; Langer, 2015). Pro-gender policies only provides a framework, but it is at the level of implementation and monitoring set targets that may enforce social change. Social transformation and the combat of poverty is complex phenomena in which research findings and the mediation of authentic life stories contribute to the body of knowledge of how women negotiate gender among other identities to live meaningful lives.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Adriaanse, J. A., and Claringbould, I. (2016). Gender equality in sport leadership: from the brighton declaration to the sydney scoreboard. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 51, 547–566. doi: 10.1177/1012690214548493

Adriaanse, J. A., and Schofield, T. (2014). The impact of gender quotas on gender equality in sport governance. J. Sport Manage. 28, 485–497. doi: 10.1123/jsm.2013-0108

Ahmed, S. (2007). The language of diversity. Ethnic Racial Stud. 30, 235–256. doi: 10.1080/01419870601143927

Anderson, E. (2005). In the Game: Gay Athletes and the Cult of Masculinity. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Beutler, I. (2008). Sport serving development and peace: achieving the goals of the United Nations through sport. Sport Soc. 11, 359–369. doi: 10.1080/17430430802019227

Blank, H. (2012). Straight: The Surprisingly Short History of Heterosexuality. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Burnett, C. (2004). The status of SA Women in Sport & Recreation 1994 to 2004. Pretoria: South African Sports Commission.

Burnett, C. (2012). Stories from the Field: GIZ/YDF Footprint in Africa. Pretoria: GIZ GmbH Youth Development Project.

Burnett, C. (2013). GIZ/YDF and youth as drivers of sport for development in the African context. J. Sport Dev. 1, 4–15. doi: 10.1080/13573322.2013.833505

Burnett, C. (2015). Assessing the sociology of sport: on sport for development and peace. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 50, 385–390. doi: 10.1177/1012690214539695

Burnett, C. (2017). “What is meaningful physical education in a South African context of rural poverty,” in Physical Education and best practices in Primary Schools, eds. B. Antala, D. Colella and S. Epifani (Prague: FIEP-EUROPE), 337–350.

Burnett, C., and Hollander, W. J. (2008). The Pre-impact Assessment of the School Sport Mass Participation Project. Johannesburg: University of Johannesburg, Department of Sport and Movement Studies.

Burnett, C., and Hollander, W. J. (2013). GIZ/YDF Final Impact Assessment: 2014. Johannesburg: University of Johannesburg, Department of Sport and Movement Studies.

Burton, C. (1987). Merit and gender: organisations and the mobilisation of masculine bias. Aust. J. Soc. Issues 22, 424–435. doi: 10.1002/j.1839-4655.1987.tb00835.x

Capranica, L., Piacentini, M. F., Halson, S., Myburgh, K. H., Ogasawara, E., and Millard-Stafford, M. (2013). The gender gap in sport performance: equity influences equality. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 8, 99–103. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.8.1.99

Chawansky, M. (2011). “New social movements, old gender games? Locating girls in the sport for development and peace movement,” in Critical Aspects of Gender in Conflict Resolution, Peacebuilding, and Social Movements, eds A. C. Snyder, and S. P. Stobbe (Bingley; West Yorkshire: Emerald Group Publishing Limited), 121–134.

Coakley, J. (2011). Youth Sports: what counts as “positive development?” J. Sport Soc. Issues 35, 306–324. doi: 10.1177/0193723511417311

Cohen, A., and Ballouli, K. (2016). Exploring the cultural intersection of music, sport and physical activity among at-risk youth. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 41, 283–294. doi: 10.1177/1012690216654295

Cronin, O. (2011). Comic Relief Review: Mapping the Research on the Impact of Sport and Development Interventions. Manchester: Orla Cronin Research.

Cunningham, G. B. (2008). Creating and sustaining gender diversity in sport organizations. Sex Roles 58, 136–145. doi: 10.1007/s11199-007-9312-3

Cunningham, G. B. (2015). Diversity and Inclusion in Sport Organizations. 3rd Edn. Milton Park Oxfordshire: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group.

Darnell, S. C. (2014). Orientalism through sport: towards a Said-ian analysis of imperialism and ‘Sport for Development and Peace'. Sport Soc. 17, 1000–1014. doi: 10.1080/17430437.2013.838349

Darnell, S. C., Chawansky, M., Marchesseault, D., Holmes, M., and Hayhurst, L. (2016). The state of play: critical sociological insights into recent ‘Sport for Development and Peace' research. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 53, 133–151. doi: 10.1177/1012690216646762

De Silva De Alwis, R. (2018, January 10). Commission in bid to tackle gender equality challenges. The New Age. p. 16.

Eliasson, I. (2011). Gendered socialization among girls and boys in children's football teams in Sweden. Soccer Soc. 12, 820–833. doi: 10.1080/14660970.2011.609682

Embrick, D. (2011). The diversity ideology in the business world: a new oppression for a new age. Critic. Sociol. 37, 541–556. doi: 10.1177/0896920510380076

Fakier, K., and Cock, J. (2010). A gendered analysis of the crisis of social reproduction in contemporary South Africa. Int. J. Femin. Politics 11, 353–371. doi: 10.1080/14616740903017679

Fasting, K., Huffman, D., and Sand, T. S. (2014). Gender, Participation and Leadership in Sport in Southern Africa: A Baseline Study. Oslo: The Norwegian Olympic and Paralympic Committee and Confederation of Sports.

Forde, S. (2008). Playing by their Rules: Coastal Teenage Girls in Kenya on Life, Love and Football. Kilifi: Moving the Goalposts.

Goslin, A. (2008). Print media coverage of women's sport in South Africa. Afr. J. Phys. Health Educ. Recreation Dance 14, 299–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00087.x

Gramsci, A. (1971). Selections from the Prison Notebooks. eds Q. Hoare and G. M. Smith. London: Lawrence and Wishart.

Hardin, M., and Whiteside, E. E. (2009). The power of “small stories”: narratives and notions of gender equality in conversations about sport. Sociol. Sport J. 26, 255–276. doi: 10.1123/ssj.26.2.255

Hargreaves, J. (1997). Women's sport, development, and cultural diversity: the South African experience. Women's Stud. Int. Forum 20, 191–209. doi: 10.1016/S0277-5395(97)00006-X

Hayhurst, L. M. C. (2011). Corporatizing sport, gender and development: postcolonial IR feminisms, transnational private governance and global corporate social engagement. Third World Q. 32, 531–549. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2011.573944

Hayhurst, L. M. C. (2014). The ‘Girl effect' and martial arts: Social entrepreneurship and sport, gender and development in Uganda. Gender Place Culture 21, 297–315. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2013.802674

Hesse-Biber, S. (2010). Qualitative approaches to mixed methods practice. Qual. Inquiry 16, 455–468. doi: 10.1177/1077800410364611

Jarvie, G. (2011). Sport, social division and social inequality. Sport Sci. Rev. 20, 95–109. doi: 10.2478/v10237-011-0049-0

Jeanes, R., Hills, L., and Kay, T. (2016). “Women, sport and gender inequity,” in Sport and Society, eds B. Houlihan and D. Malcolm (London: Sage), 134–156.