95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Soc. Psychol. , 25 March 2025

Sec. Intergroup Relations and Group Processes

Volume 3 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frsps.2025.1477434

Cultural appropriation is a critique of cultural borrowing or outgroup cultural use, typically when a more powerful cultural group adopts cultural elements from a less powerful group. Accusations of appropriation have been fiercely debated in recent years, which raises questions about appropriate vs. appropriative adoption of another group's culture. We propose that these different evaluations hinge in part on diversity ideologies. In four studies of U.S. participants (total N = 1,549), we examined the differing effects of three diversity ideologies (colorblindness, multiculturalism, and polyculturalism) on judgments of common cases of cultural appropriation. We found that multiculturalism was associated with harsher judgment, whereas colorblindness and polyculturalism were associated with more lenient judgment. Additionally, we explored the perception of the costs and benefits involved in cultural appropriation and found the associations between diversity ideologies and judgments to be mediated by perceived misrepresentation, permission, distinctiveness, and honorific intent. We conclude that each diversity ideology makes different trade-offs salient in the perceived costs and benefits of cultural use across groups.

Cultural appropriation, a term that has been around in the English language for at least 70 years (Oxford English Dictionary, 2018), did not begin enjoying widespread usage in the public discourse until very recently. In the United States, public interest started spiking around 2015 and peaked in 2018 (Google Trends). Cultural appropriation emerges as a critique of cultural borrowing or out-group cultural use, one group adopting cultural styles or products from another group. The vast majority of public discussions sprouted in response to viral charges of cultural appropriation (e.g., Halloween costumes on college campuses and white artists performing in a minority group's cultural style). In its current form, cultural appropriation has been intricately involved in cultural politics and become ideological (Cho et al., 2025). For example, pundit opinions run the gamut from being critical and outraged to mounting defenses and singing praises (Avins, 2015; Arewa, 2017; Frum, 2018; Johnson, 2015; Malik, 2017; Nittle, 2019; Weiss, 2017; White, 2016).

We propose that the range of reactions is, at its core, about managing competing issues that arise from cultural borrowing or use in intergroup contexts. We seek to understand this divide from the perspective of diversity ideologies (Morris et al., 2015; Rosenthal and Levy, 2010). Diversity ideologies are lay beliefs about how to manage the different groups coexisting in pluralistic societies that have implications for intergroup relations, such as prejudice reduction (Morris et al., 2015; Plaut, 2010; Rosenthal and Levy, 2010). Our thesis is that diversity ideologies provide different lenses for understanding the nature of cultural appropriation and the historical and political conditions in which it takes place, which, in turn, shape evaluations. Two commonly studied ideologies are colorblindness (CB) and multiculturalism (MC). In recent years, polyculturalism (PC), which recognizes historical and contemporary connections among groups, emerged as a third, complementary approach (Morris et al., 2015; Rosenthal and Levy, 2010).

In this article, we examine not only the differing effects of these ideologies on judgments of cultural appropriation but also where the ideological differences may stem from. In short, we show that the differences contributing to the polemic discourse may be rooted in different prescriptions of weighing the various costs and benefits involved in acts of appropriation. MC prioritizes protecting vulnerable source groups and thus sensitizes people to the various costs of cultural appropriation, such as misrepresentation, collective ownership, and violating group distinctiveness. CB reflects the erasure of group categories altogether and, consequently, a dismissal of group-based concerns about cultural appropriation. Finally, PC orients people toward seeing appropriation as micro-instances of mutual influence of interacting groups and highlights the willingness to consider, on balance, more benefits than costs.

The controversy over cultural appropriation begins with the definition itself, which is evident in public as well as scholarly discussions (Lenard and Balint, 2020; Matthes, 2016; Young, 2005). Although cultural adoption across groups is an age-old phenomenon that has been studied in fields such as anthropology (Richerson and Boyd, 2006; Redfield et al., 1936), cultural appropriation is often used to problematize cultural borrowing, conveying the sentiment that some acts are inappropriate. Central to common charges of appropriation is the existence of a power difference between groups (Jackson, 2019). When the more powerful group borrows from the less powerful—such as when white people adopt styles, symbols, and artifacts associated with African Americans and indigenous peoples—it tends to stir public outrage. Asymmetry in perceptions of appropriation is mirrored in asymmetry in status (Finkelstein and Rios, 2022; Mosley and Biernat, 2021). Thus, we focus on prototypical cases of dominant group appropriation in this research.

To further understand why cultural appropriation is controversial requires probing people's assumptions, especially about the historical and political conditions producing contemporary discussions. Our key theoretical assumption lies in construing cultural appropriation differently, which elicit diverging evaluations. In his seminal work, Rogers (2006) distinguished four forms of cultural borrowing: cultural exchange, cultural exploitation, transculturation, and cultural dominance. Consider, for a moment, construing cultural borrowing as exploitation vs. exchange. Exploitation comes closest to how laypeople often invoke cultural appropriation to condemn acts by the majority group. Viewed through this lens, cultural borrowing reproduces intergroup inequality and amounts to a form of theft or illegitimate cultural consumption. In contrast, if cultural borrowing is understood as the free exchange of cultural goods between groups, it may be deemed permissible and even laudable as it serves to break down cultural barriers. Implicit in public and scholarly discourses is where to draw the boundary between genuine cultural exchange and exploitation (Kunst et al., 2024).

Diversity ideologies have been studied mostly in relation to efforts to reduce prejudice and improve intergroup relations in racially and ethnically diverse societies such as the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands (Morris et al., 2015; Plaut, 2010; Rosenthal and Levy, 2010). Much of this work focuses on examining the divergent effects of diversity ideologies on intergroup relations and identifying circumstances or ways in which one ideology is more effective relative to another in reducing intergroup bias (for reviews, see Apfelbaum et al., 2012; Rattan and Ambady, 2013; Rosenthal and Levy, 2010, for meta-analyses, see Leslie et al., 2020; Whitley and Webster, 2019). In the following, we connect this body of work with different construals of cultural appropriation to elucidate how diversity ideologies shape perceptions of cultural appropriation.

As a historically influential approach, especially in the United States, CB attributes the problem of racial bias to the overemphasis of group categories and prescribes identity-blind messages such as universalism and uniqueness of individuals (Rosenthal and Levy, 2010). We predicted that CB sets up a mindset akin to Rogers's cultural exchange and thus should be associated with a permissive stance of cultural borrowing.

By downplaying group categories (i.e., color evasion), CB provides an ideological justification for separating the appropriated product from its original context and cultural meaning. For example, CB allows white youth to consume hip-hop music in a way that allows them to present themselves as cool but glosses over its racially coded meanings and historical roots (Rodriquez, 2006). The universalism appeal in CB—similarities among groups and individualization (Whitley et al., 2023)—is likely to locate cultural borrowing in a context resembling a marketplace in which individuals voluntarily trade cultural goods. Thus, CB encourages people to see cultural borrowing as an exchange between individuals on equal terms. In addition, although it has the promise of reducing intergroup bias (Correll et al., 2008; Wolsko et al., 2000), CB as practiced is also shown to blind people to existing injustice between racial groups in support of the status quo (Apfelbaum et al., 2010; Knowles et al., 2009; Neville et al., 2013). Because group-based concerns are often voiced amid outcries of cultural appropriation (e.g., misrepresentation, group distinctiveness, and collective ownership), by stripping away the relevance of group categories, CB could therefore desensitize its supporters from recognizing these concerns in their judgment of cultural borrowing.

Overall, our analysis indicates CB affords a benign view of cultural borrowing by equating it with an exchange of cultural products taking place in a free and fair market and downplaying potential group-based costs involved in borrowing by the majority group.

As an ideological counterpoint to CB, MC advances a group-based philosophy about managing diversity. MC as practiced takes several related forms, but the common elements are recognizing group differences and valuing cultural diversity (Cobb et al., 2020; Rosenthal and Levy, 2010). Empirically, MC is often tested against CB with a view of evaluating which ideology produces generally more positive intergroup outcomes (e.g., Leslie et al., 2020; Vorauer and Sasaki, 2010). Compared to CB, MC leads to less explicit or implicit intergroup bias (Richeson and Nussbaum, 2004), more positive affect toward the out-group (Vorauer et al., 2009), and higher ethnic identification among minority groups (Verkuyten, 2005). We predicted that MC sets up a protectionist mindset toward the majority group's cultural borrowing and should be associated with a critical view.

This prediction may seem less intuitive because MC suggests an open and accepting attitude toward other cultures. For example, MC can instill an outward focus on engaging with and learning from other cultures (Rios and Wynn, 2016; Vorauer et al., 2009). Cultural borrowing by the majority group could be thus seen as appreciating diversity through the recognition of differences (as opposed to similarities emphasized by CB). However, we believe that this is only partially true and that MC aligns better with Rogers's cultural exploitation for two reasons.

First, MC is often framed as respecting minority groups' autonomy to maintain their cultural traditions (Cobb et al., 2020; Rosenthal and Levy, 2010; Verkuyten and Yogeeswaran, 2020). As a result, endorsing MC may increase the perception that cultural borrowing by the majority group is a form of unauthorized commodification (“stealing”; Scafadi, 2005) or harmful misrepresentation (“caricature”; Fryberg et al., 2008). Respecting minority groups through the MC lens implies protecting them from the majority group laying claim to their cultures, thus justifying condemnation of cultural borrowing.

Second, recognizing group differences assumes some degree of groups' cultural distinctiveness and the relatively fixed boundaries between them (Morris et al., 2015; Verkuyten and Yogeeswaran, 2020). Cultural borrowing by the majority group is therefore likely to be interpreted as a threat to the source group's distinctiveness through the MC lens, resulting in appropriation charges. For example, compared with white Americans, Black Americans are more likely to perceive cultural borrowing by white Americans as appropriative because they experience a more salient distinctiveness threat (Mosley and Biernat, 2021). Similarly, people who endorse MC may be more likely to infer a distinctiveness violation from the majority group's cultural borrowing.

Overall, we suggest that MC affords a critical view of cultural borrowing. Although MC might allow people to see cultural borrowing as a token of appreciation, we think it sensitizes people more to various group-based costs such as misrepresentation and a distinctiveness threat borne out by minority groups.

The more recently studied ideology, PC shares important features of MC, namely, recognizing group identities and differences, making both differ from CB. Drawing on key insights from historians who study how cultural traditions shaped each other in the past (Kelley, 1999; Nederveen Pieterse, 2009; Prashad, 2001, 2003), however, PC encourages people to see cultures as interacting with each other and evolving over time (Morris et al., 2015; Rosenthal and Levy, 2010). It is thus similar to Rogers's transculturation, which refers to recombining cultural elements and styles. Compared with MC, which has received backlash in recent years for resulting in segregation and provincialism (Hahn et al., 2015; Morris et al., 2015; Verkuyten and Yogeeswaran, 2020), PC promotes connections between groups and prescribes intercultural dialogue as the basis for diversity policy (Morris et al., 2015; Rosenthal and Levy, 2010; also see, Verkuyten et al., 2020). Although MC and PC are positively correlated with each other in previous research (e.g., Rosenthal and Levy, 2012), they should be dissociable when it comes to predicting judgment of cultural borrowing. We predicted that PC should be associated with more lenient evaluations of cultural borrowing because its benefits are perceived to outweigh the costs.

A major difference between the two is the distinctiveness of group differences. Because MC emphasizes group differences, it tends to promote a museum view of culture frozen in time and separated by space. Consistent with this difference, MC is shown to increase essentialist beliefs about groups (Wilton et al., 2019) and stereotyping (Gutiérrez and Unzueta, 2010; Wolsko et al., 2000). In contrast, people who endorse PC are less likely to essentialize race (Bernardo et al., 2016) and more likely to borrow foreign ideas (Cho et al., 2018) and seek culturally hybrid experiences (Cho et al., 2017). This means that PC advocates may be more likely to categorize cultural borrowing as a culturally hybrid experience and believe societal benefits accrue from such interactions in the long run. Although policing group boundaries to preserve cultural distinctiveness is a major concern of MC, it is seen as impeding intercultural engagement through the PC lens (Morris et al., 2015; Verkuyten et al., 2020). Thus, PC should also be associated with discounting group-based concerns that have specifically to do with maintaining group boundaries, such as authenticity and purity threats (Cho et al., 2017).

Overall, PC should differ from MC in that it is expected to be associated with benefit perceptions more and/or cost perceptions less. Importantly, despite expecting both CB and PC to be associated with more lenient evaluations, we believe the underlying reasons differ. CB involves dismissing all group-based concerns, whereas PC fosters culturally hybrid experiences and is concerned less with policing group boundary crossing.

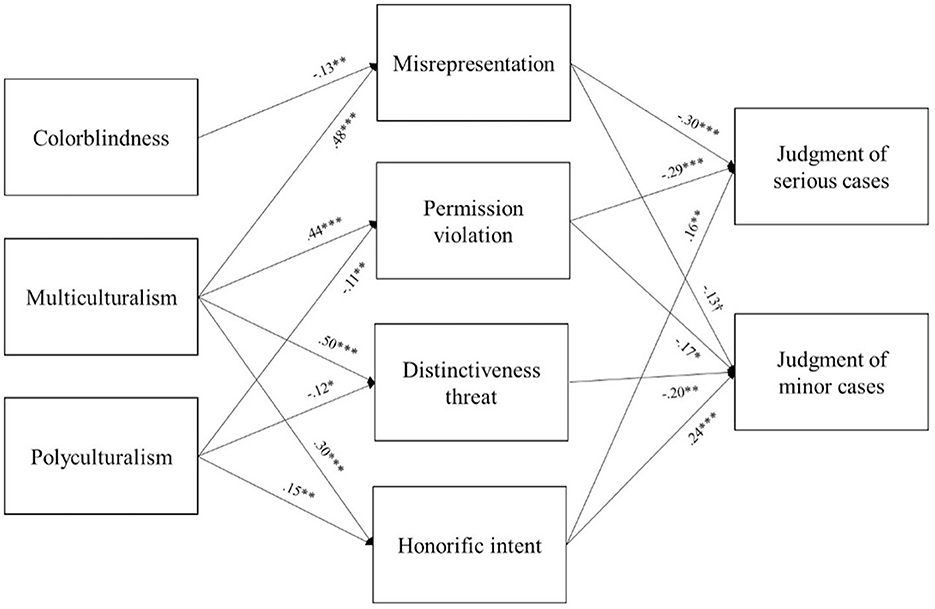

We aim to test both the direct and indirect effects of diversity ideologies on evaluations of cultural borrowing. Figure 1 presents the full theoretical model which delineates how diversity ideologies affect judgments via perceived costs and benefits of cultural borrowing. In this model, we treat diversity ideologies as antecedents of judgments. We expect CB and PC to be directly associated with less condemnation of cultural borrowing and MC to be directly associated with more condemnation. In all the studies we report in this article (Studies 1–4), we tested the unique contribution of each ideology while controlling for demographic covariates in multiple regression models. These direct associations between diversity ideologies and judgments represent our primary hypotheses.

In addition, these hypothesized associations are predicated on diversity ideologies sensitizing people to the different tradeoffs reflected in perceived costs and benefits. From Study 2 onward, we developed items to capture the various costs and benefits arising from cultural borrowing. Because we did not have a firm idea of the number of factors a priori, we took a more empirical approach. Once we empirically confirmed the factor structure, we proceeded to test whether the ideology–judgment associations are mediated by those factors and then attempted to replicate the indirect effects. Modeling the indirect effects allowed us not only to test whether a particular pathway exists but also to ascertain the overall indirect effects of a particular ideology, thus providing a glimpse of trade-offs between costs and benefits.

In all studies, American participants reported their endorsement of CB, MC, and PC and evaluated hypothetical cases of cultural borrowing. Except for the student sample in Study 1, we recruited participants online via Prolific Academic (Prolific) and Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) platforms to increase the power and generalizability of the results beyond undergraduate populations. Table 1 lists the demographic information for each sample. Compared to the student sample, the online samples were older, more gender-balanced, and more politically diverse. The student participants received course credit in exchange for their participation, while the online participants were compensated at a predetermined rate in each study that ranged from $6.50 to $9.00 in US dollars per hour. We administered attention checks to screen out inattentive participants. The details of those checks and the exclusion criteria are reported in each study (see Table 1 for a summary of initial vs. final N in each sample). Tables 2, 3 present the descriptive information of the focal variables and their intercorrelations in each sample, respectively.

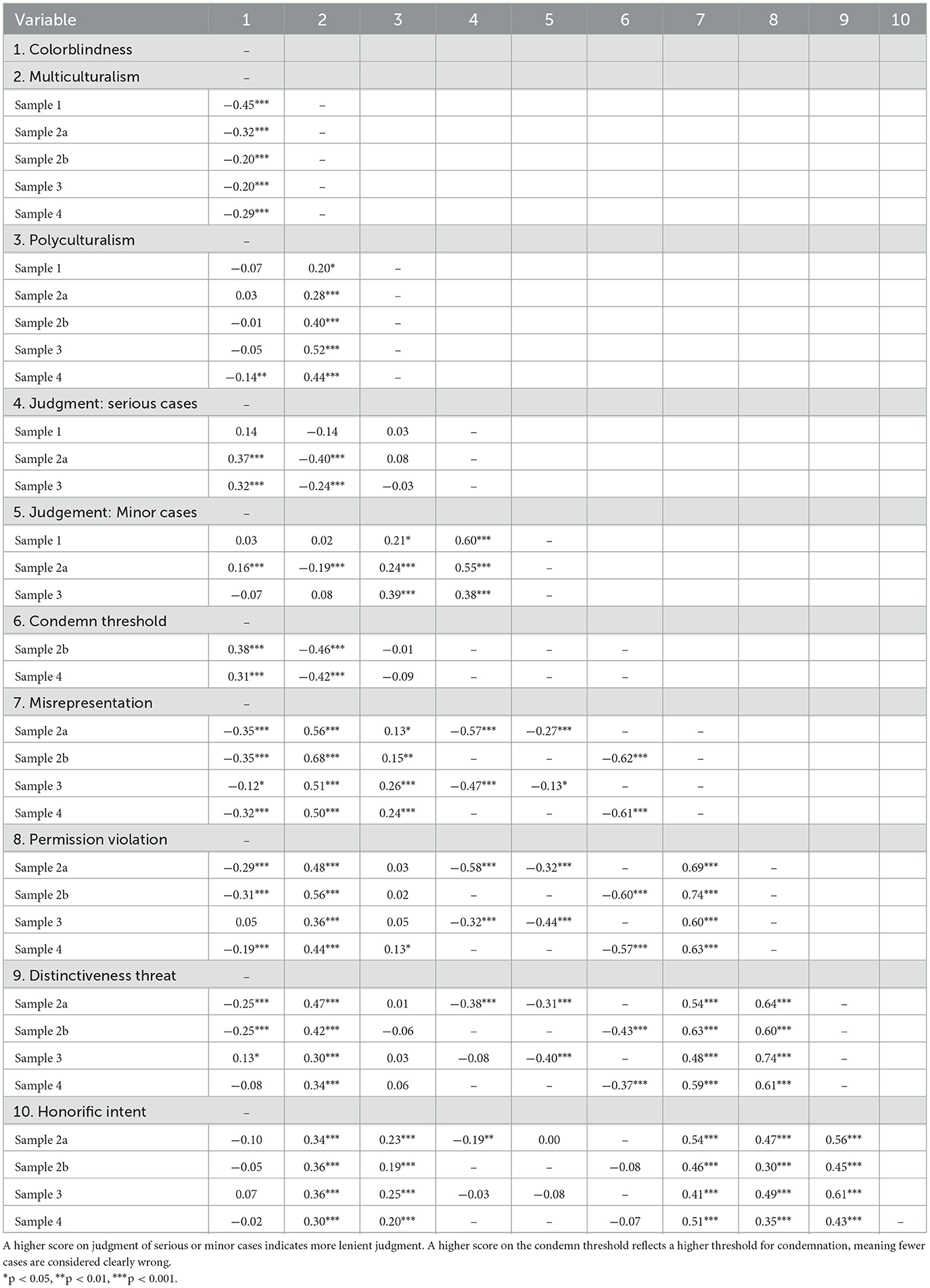

Table 3. Bivariate correlations between diversity ideologies, judgment factors, and evaluations of cultural borrowing.

Study 1 was an initial exploration of the diversity ideologies' direct effects on judging cultural borrowing. To assess individual differences in endorsing the three ideologies, we adopted standard measures from previous research in which their effects were directly compared (e.g., Bernardo et al., 2016; Rosenthal and Levy, 2012; Rosenthal et al., 2012).

This study included 127 students from a college in the northeastern United States. After providing consent, they were first shown a neutral definition of cultural appropriation: “Cultural appropriation is typically thought of as use or borrowing of cultural elements of one group by another group”. The paragraph then noted cultural appropriation is controversial because “some view it as inappropriate, unauthorized, or offensive, while others view it as defensible, benign, or admirable”. Participants proceeded to judge a number of hypothetical cases, followed by the diversity ideologies measures and demographic questions. We interspersed three instructional attention checks throughout the survey, and only those who answered at least two of them correctly were retained in the final sample.

Participants indicated their agreement with five items for each ideology—CB (Rosenthal and Levy, 2012; e.g., “At our core, all human beings are really all the same, so racial and ethnic categories do not matter”), MC (Rosenthal and Levy, 2012; e.g., “There are differences between racial and ethnic groups, which are important to recognize”), and PC (Rosenthal and Levy, 2012; e.g., “Different racial, ethnic, and cultural groups influence each other”). These scales were presented in a randomized order for each participant. All items were rated on a 7-point scale (1 = Strongly disagree to 7 = Strongly agree).

Participants responded to 12 short, hypothetical cases of cultural borrowing, presented in a random order, on a 7-point scale (1 = Completely wrong, 4 = Not sure, 7 = Not wrong at all). In assembling the cases, we aimed to (a) sample a wide range of domains in which charges of cultural appropriation have occurred and (b) capture incidents that have received media coverage to enhance ecological validity. To that end, we wrote 12 cases covering music, fashion, cuisine, literature, cinema, sports teams, and college campuses (see Supplementary Table S1). In most cases, a dominant group (e.g., white Americans) is described as adopting cultural styles from a marginalized group (e.g., African Americans). Specific details were removed to make each case appear as generic as possible.

We analyzed the factors of 12 cases using Promax rotation. Results supported a two-factor solution (Supplementary Table S1). While 11 cases loaded strongly on one factor (>0.40), one item loaded weakly on both and thus was excluded. What distinguished the two factors was the level of perceived wrongness. Cases comprising the first factor were rated, on average, considerably more wrong (M = 3.01, SD = 1.13) compared to those comprising the second factor (M = 5.50, SD = 0.93). Thus, we labeled them high-controversy and low-controversy cases, respectively. Notably, high-controversy cases cover topics widely discussed in public as cultural appropriation (e.g., Halloween costumes, Native American mascot, African American hairstyle) and are thus most prototypical (Mosley and Biernat, 2021). For each type of case, we computed composite scores, with higher scores indicating more lenient judgment.

The intercorrelations among diversity ideologies (see Table 31) are consistent with what was reported in previous research (Bernardo et al., 2016; Rosenthal and Levy, 2012; Rosenthal et al., 2012).

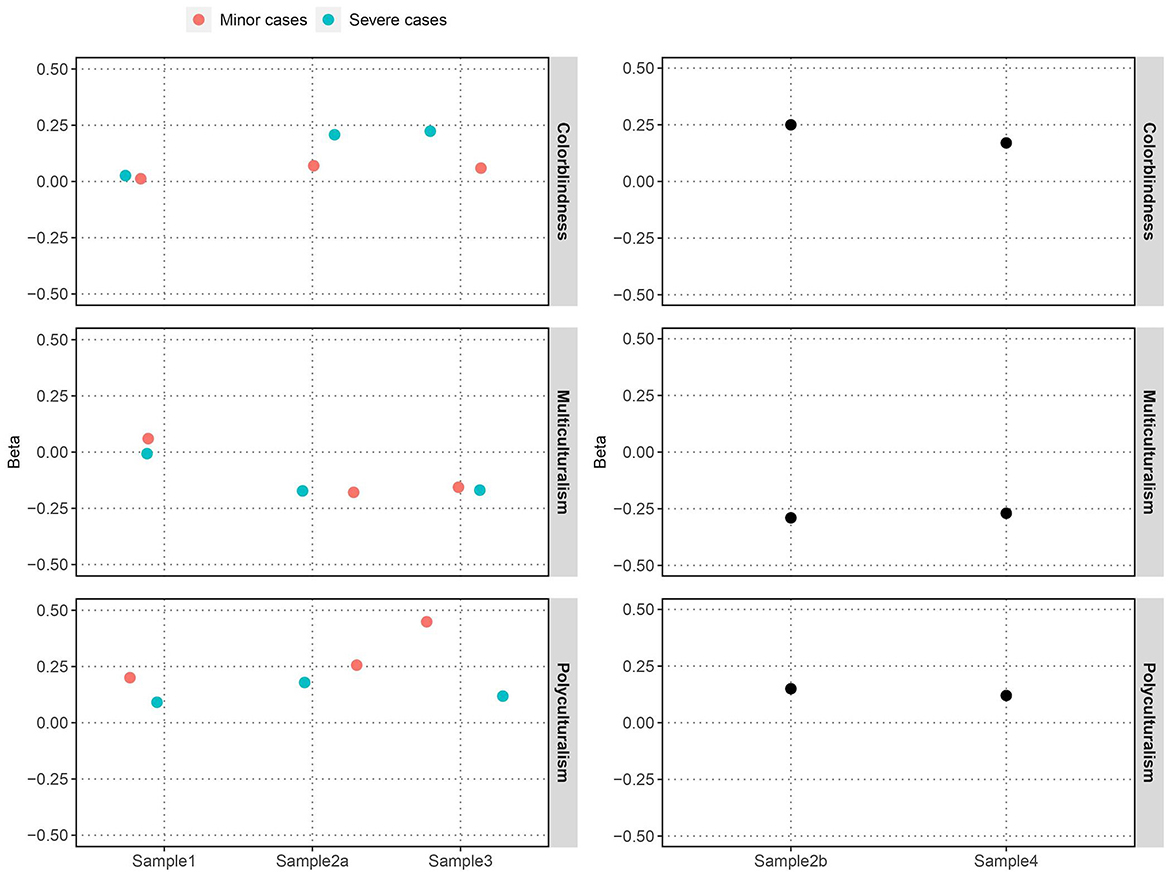

Regarding bivariate associations between diversity ideologies and evaluations, only PC was significantly correlated with judging minor cases more leniently. Next, we conducted regression analyses to test the unique effects of each diversity ideology while controlling for the effects of the other ideologies and gender, race2, and political orientation on social and economic issues. Controlling for demographic variables helps rule out some alternative explanations. For example, compared to conservatives, American liberals condemn cultural borrowing more (Cho et al., 2025), so controlling for political orientation disentangles the effects of diversity ideologies from political differences such that the diversity ideologies' effects are not due to liberals supporting MC more or CB less than conservatives. For each case type, we conducted a hierarchical regression analysis in which demographic variables were entered as predictors in Step 1, followed by the three ideologies in Step 2. Multicollinearity diagnostics confirmed that all variance inflation factors (VIFs) were acceptable (<2)3. Demographic variables accounted for 21% and 16% of the variance; women, racial minorities, and social liberals tended to perceive more wrongness. In Step 2, consistent with the bivariate association, only PC was correlated with more lenient judgment, β = 0.20, p = 0.02. Figure 2 provides a visualization of the unique effects of diversity ideologies for all four studies (for details on hierarchical regression models, see Supplementary Tables S5–S9).

Figure 2. Divergent effects of diversity ideologies on evaluations of cultural borrowing. Each dot represents a standardized coefficient for the corresponding diversity ideology from hierarchical regression models in which demographic variables and diversity ideologies were entered at Steps 1 and 2, respectively. The left panel shows results for evaluations of serious and minor cases, with a positive coefficient indicating the ideology was correlated with a less negative evaluation. The right panel shows results for condemnation threshold, with a positive coefficient, indicating the ideology was correlated with a higher condemnation threshold.

In this study, we sought to extend Study 1 in several ways. First, we tested the associations between diversity ideologies and judgment in two larger and demographically broader samples (Samples 2a and 2b). Second, we tested the full theoretical model by assessing the perceived costs and benefits of cultural borrowing and explored whether these factors would mediate the associations between diversity ideologies and judgment. Third, we used Wolsko et al. (2006) measure of MC. Compared with Rosenthal and Levy's measure that focuses on recognizing differences, MC is conceptualized more broadly in Wolsko et al.'s measure; it also includes appreciation for contributions from different cultures and the need to maintain cultural traditions (see Rosenthal and Levy, 2010). Finally, in addition to having participants rate how wrong each case was, we developed an alternative measure we call threshold for condemnation. We applied this threshold scoring in Sample 2b, while we retained the standard evaluation scale in Sample 2a.

Samples 2a and 2b, respectively, consisted of 318 and 363 participants recruited from Prolific. The procedure was identical to Study 1 but added a set of items assessing the perceived costs and benefits of cultural borrowing. These items were presented after the judgment measure but before the diversity ideologies measures. The only difference between the two samples was the judgment measure. In Sample 2a, we used the same instructional attention checks and exclusion criteria as we did in Study 1. In Sample 2b, we employed two different checks: one instructing participants to choose an out-of-range option (Oppenheimer et al., 2009) and the other, embedded in the new items, asking participants the extent to which being good at math was relevant to their judgment of cultural borrowing (for a similar method, see Graham et al., 2009). Those who answered the first question incorrectly or rated being good at math as being somewhat, very, or extremely relevant were subsequently removed.

We assessed the endorsement of CB and PC with the same measures used in Study 1. For MC, we used Wolsko et al. (2006) six-item measure. An example item of appreciating contributions from different cultures is “we must appreciate the unique characteristics of different ethnic or cultural groups to have a cooperative society”; an example item of the need to maintain cultural traditions is “if we want to help create a harmonious society, we must recognize that each ethnic or cultural group has the right to maintain its own unique traditions”. As in Study 1, all items were rated on a 7-point scale.

In Sample 2a, we presented the same 12 cases from Study 1. A factor analysis using Promax rotation resulted in a similar two-factor structure differentiating high- (M = 4.10, SD = 1.63) from low-controversy (M = 6.16, SD = 0.99) cases (see Supplementary Table S2). Two cross-loaded items were removed.

In Sample 2b, we developed a more direct measure of where people draw the line between appropriate and appropriative acts, which we term condemnation threshold. Specifically, participants were presented with a list of 18 cases that included the original 12 cases and 6 additional cases. They were instructed to select those that were clearly wrong in their opinion. We did not ask participants about their perception of appropriation per se (i.e., whether the act is appropriative) to avoid confusion over the term itself (cf. Mosley et al., 2023b). To reduce demand characteristics, it was emphasized that they could select as many or few cases as they saw fit. The number of selections each participant made, bounded between 0 and 18 (M = 5.85, SD = 3.62), reflects individual differences in readiness to condemn. For example, someone who selects 12 cases is more ready to condemn, thus having a lower threshold for condemnation compared to the person who selects 3 cases. We subtracted 19 from the number of selections for each participant such that a higher score reflected a higher threshold for condemnation. People with a lower condemnation threshold cast more cases as condemnable, whereas those with a higher threshold are less sweeping in their judgment and reserve fewer cases for condemnation.

We randomly presented 36 items to the participants in Samples 2a and 2b, asking them to rate the relevance of each item to evaluating cultural borrowing in general on a 6-point scale (0 = Not at all relevant to 5 = Extremely relevant; see Table 4 for the full list). Because these ratings referenced cultural borrowing in general rather than each case presented, they capture individual differences between perceivers instead of differences within the same perceiver as a function of case. Through exploratory factor analysis, we extracted five factors (see the Supplementary material for details): intent to insult, capturing malicious intent of the agent behind cultural borrowing; harmful consequences, specifically in terms of misrepresentation; permission violation, with items raising the questions of who owns cultural products and who is permitted to represent the source culture; distinctiveness threat, referring to the distinctiveness of boundaries between groups that may be blurred by acts of borrowing; and honorific intent, with most items capturing positive intent and some social benefits. Composite scores for each factor were calculated by averaging the corresponding items.

Compared with Study 1, Study 2′s bivariate correlations between diversity ideologies and evaluations were much stronger in both samples (Table 3).

As in Study 1, hierarchical regression analyses were conducted (see Supplementary Table S6). We controlled for age in addition to gender, race, and political orientation (social and economic issues). First, demographic variables accounted for 32% and 13% of the variance, respectively. Women and social liberals perceived more wrongness in serious cases, whereas women and ethnic minorities perceived more wrongness in minor cases. Next, diversity ideologies accounted for an additional 10% and 6% of the variance. CB was correlated with more lenient judgment in serious cases only, β = 0.21, p < 0.001. MC was correlated with harsher judgment in both types of cases, β = −0.18, p < 0.001, and β = −0.12, p = 0.04, respectively. PC was correlated with more lenient judgment in both types of cases, β = 0.18 and β = 0.25, ps < 0.001, respectively.

Demographic variables accounted for 26% of the variance in condemnation threshold. Women, younger adults, and liberals (social and economic) showed lower condemnation thresholds. Diversity ideologies accounted for an additional 16% of the variance. Although MC was correlated with a lower condemnation threshold, β = −0.32, p < 0.001, both CB and PC were uniquely correlated with higher thresholds, β = 0.26, p < 0.001, and β = 0.16, p < 0.001, respectively (see Supplementary Table S7).

In summary, diversity ideologies were correlated with judgment beyond demographic variables. CB and PC were correlated with more lenient judgment and higher condemnation thresholds, whereas MC was correlated with the opposite.

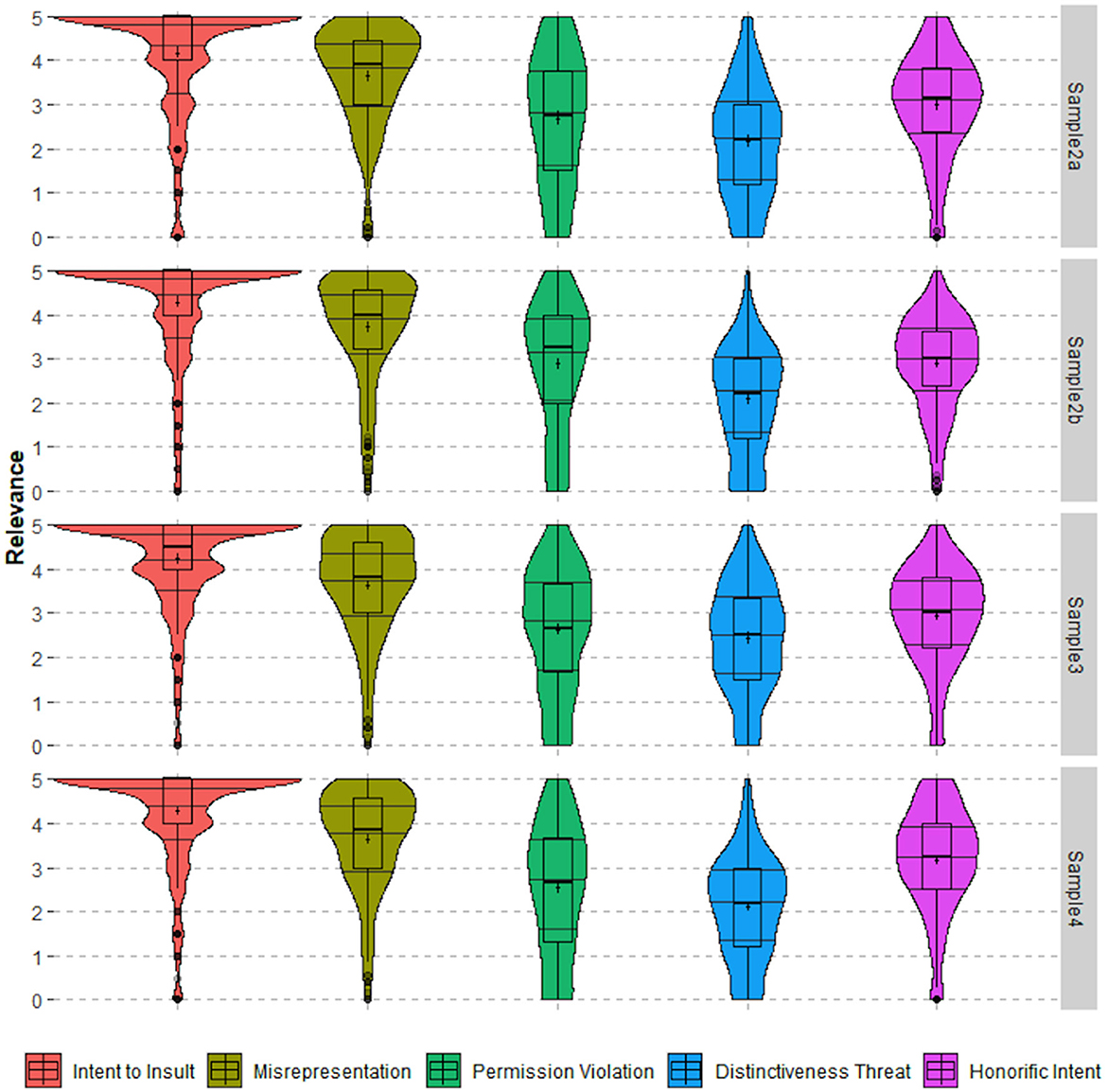

Figure 3 visualizes the rank order of the five factors pertaining to the costs and benefits of cultural borrowing. Intent to insult was judged most relevant in both samples, so much so that there was a ceiling effect as its median was 5 (the highest possible scale point), followed by misrepresentation. Farther down, honorific intent and permission violation were similarly rated. Distinctiveness threat was judged least relevant, with its means hovering below the scale midpoint.

Figure 3. Distribution of the five judgment factors across samples. Graph shows violin plots with density distribution of the five judgment factors, 25%, medians, and 75% quantiles, boxplots, and means with bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals.

We omitted intent to insult due to its restricted range. Diversity ideologies showed divergent associations with the remaining four factors (Table 3). CB and MC showed opposite patterns such that MC was associated with an increased relevance of all four factors, whereas CB was associated with reduced relevance of misrepresentation, permission, and distinctiveness but unrelated to honorific intent. Similar to MC, PC was associated with an increased relevance of misrepresentation and honorific intent. Unlike MC, it was unrelated to permission and distinctiveness. Finally, all four judgment factors were associated with the two evaluation measures.

Given these correlations, we constructed and tested path models with the four judgment factors as mediators to explain the associations between diversity ideologies and evaluation. We built each path model in an iterative fashion, beginning with linking variables based on the bivariate correlations. We improved the model by checking the overall model fit indices and modification indices. Meanwhile, we controlled for demographic variables correlated with judgment factors or evaluation. To test indirect effects, we constructed 95% confidence intervals (CIs) with 5,000 bootstrapped resamples. We examined both individual indirect effects and overall indirect effects.

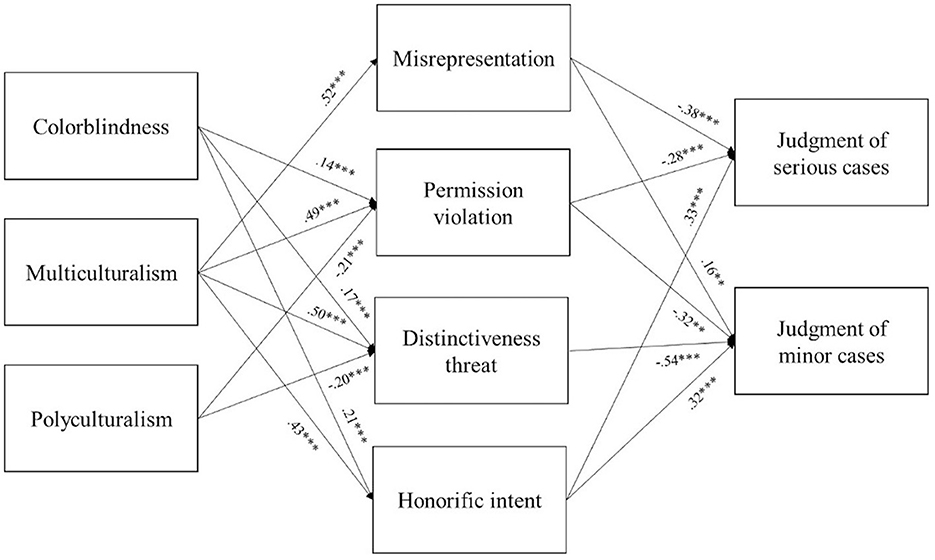

Figure 4 shows the final path model: χ2(14) = 12.44, p = 0.57, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 1.00, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.00, 90% CI [0.000, 0.049], Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) = 0.020. Several patterns are noteworthy: First, misrepresentation, permission, and distinctiveness were correlated with harsher judgment, whereas honorific intent was correlated with more lenient judgment. The only exception is distinctiveness, which was not correlated with judgment of serious cases. Second, CB was correlated with more lenient judgment via reduced concerns about misrepresentation (serious cases: b = 0.04, 95% CI [0.015, 0.084]; minor cases: b = 0.01, 95% CI [0.001, 0.034]). Third, PC was correlated with more lenient judgment of serious cases via reduced concerns about permission (b = 0.07, 95% CI [0.018, 0.139]) and increased relevance of honorific intent (b = 0.05, 95% CI [0.016, 0.106]). PC was correlated with more lenient judgment of minor cases via reduced concerns about permission (b = 0.02, 95% CI [0.002, 0.064]) and distinctiveness (b = 0.03, 95% CI [0.005, 0.075]) as well as increased relevance of honorific intent (b = 0.05, 95% CI [0.016, 0.099]). The overall indirect effects of PC were positive (serious cases: B = 0.12, 95% CI [0.061, 0.187]; minor cases: B = 0.10, 95% CI [0.057, 0.154]), resulting in overall positive evaluations.

Figure 4. Path model showing the indirect effects of diversity ideologies on judgment (sample 2a). Standardized coefficients are displayed. The effects of demographic variables were controlled for. The direct effects of colorblindness and polyculturalism on judgment of serious cases and a direct effect of polyculturalism on judgment of minor cases remained. †p < 0.07, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Finally, MC was correlated with harsher judgment of serious cases via heightened concerns about misrepresentation (b = −0.22, 95% CI [−0.319, −0.133]) and permission (b = −0.20, 95% CI [−0.294, −0.109]); meanwhile, it was also associated with more lenient judgment via the increased relevance of honorific intent (b = 0.07, 95% CI [0.030, 0.128]). MC was correlated with harsher judgment of minor cases via heightened concerns about misrepresentation (b = −0.06, 95% CI [−0.125, −0.003]), permission (b = −0.07, 95% CI [−0.139, −0.007]), and distinctiveness (b = −0.09, 95% CI [−0.155, −0.028]) but was associated with more lenient judgment via increased relevance of honorific intent (b = 0.07, 95% CI [0.031, 0.122]). Importantly, the overall indirect effects of MC were negative (serious cases: B = −0.34, 95% CI [−0.445, −0.256]; minor cases: B = −0.15, 95% CI [−0.213, −0.098]), indicating the perceived costs outweighed the benefits, resulting in overall negative evaluations.

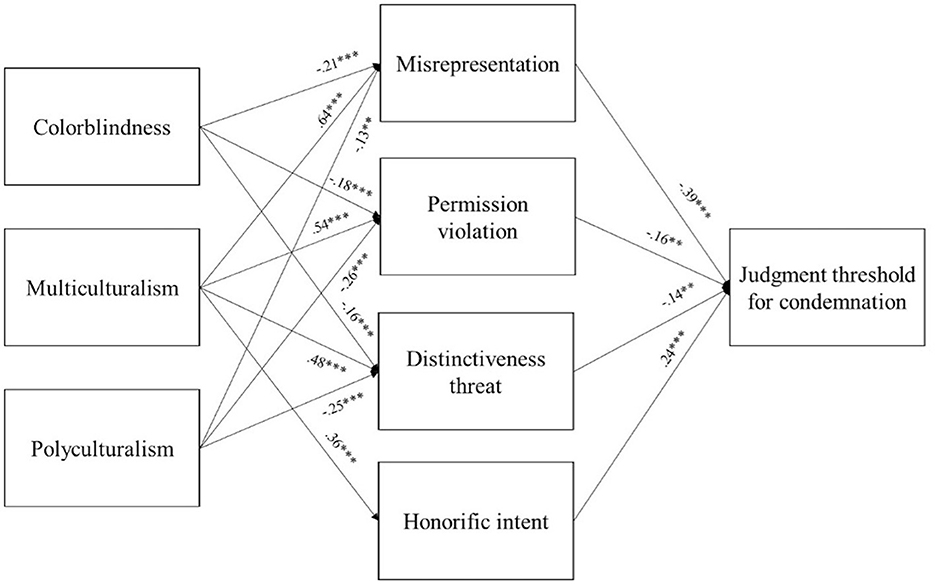

Figure 5 shows the final path model: χ2(16) = 15.02, p = 0.52, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.00, 90% CI [0.000, 0.046], SRMR = 0.019. Parallel to Figure 4, misrepresentation, permission, and distinctiveness were each correlated with a lower condemnation threshold, whereas honorific intent was correlated with a higher threshold. MC was correlated with a lower threshold via reduced concerns about misrepresentation (b = −0.85, 95% CI [−1.140, −0.562]), permission (b = −0.29, 95% CI [−0.542, −0.072]), and distinctiveness (b = −0.22, 95% CI [−0.417, −0.043]) but with a higher threshold via increased relevance of honorific intent (b = 0.30, 95% CI [0.172, 0.459]). Similar to Sample 2a, the overall indirect effects of MC were negative (B = −1.06, 95% CI [−1.299, −0.838]), indicating perceived costs outstripping benefits. PC was correlated with a higher threshold via reduced concerns about permission (b = 0.17, 95% CI [0.049, 0.344]) and distinctiveness (b = 0.15, 95% CI [0.032, 0.292]). Unexpectedly, PC was also correlated with a higher threshold via reduced concerns about misrepresentation (b = 0.22, 95% CI [0.101, 0.398]). The total indirect effects of PC were positive (B = 0.54, 95% CI [0.343, 0.748]) resulting in overall lenient judgment. CB was correlated with a higher threshold via reduced concerns about misrepresentation (b = 0.21, 95% CI [0.125, 0.338]), permission (b = 0.07, 95% CI [0.019, 0.160]), and distinctiveness (b = 0.06, 95% CI [0.011, 0.133]). The total indirect effects of CB were positive (B = 0.34, 95% CI [0.230, 0.473]) resulting in overall lenient judgment.

Figure 5. Path model showing the indirect effects of diversity ideologies on judgment threshold (sample 2b). Standardized coefficients are displayed. The effects of demographic variables were controlled for. A direct effect of colorblindness on condemnation threshold remained. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Overall, the path models shed initial light on the mechanisms by which diversity ideologies come to shape judgment. MC was correlated with harsher judgment and a lower condemnation threshold via all four factors operating in opposite directions. Importantly, the overall indirect effects indicate that the perceived costs of cultural borrowing outweigh the benefits. Across the two samples, we found consistent support for the indirect effects of MC. Although both CB and PC were correlated with more lenient judgment and a higher condemnation threshold, they did so through different lines of reasoning. On one hand, CB's permissive view of cultural borrowing was attributed to reduced concerns about misrepresentation in both samples. On the other hand, PC's lenient view was attributed to reduced concerns about permission and distinctiveness. However, there were also some inconsistent findings. CB was also associated with reduced concerns about permission and distinctiveness in Sample 2b, whereas PC was also associated with reduced concerns about misrepresentation in Sample 2b and increased relevance of honorific intent in Sample 2a.

The first goal of Study 3 was to replicate the direct effects of diversity ideologies observed in Sample 2a. We predicted that CB and PC would be associated with more lenient judgment, whereas MC would be associated with harsher judgment. Second, we continued examining the role of judgment factors by linking ideologies with judgment. We aimed to reproduce the same five-factor structure in a new sample (Sample 3) using a confirmatory approach. We then tested whether these factors would similarly mediate the associations between diversity ideologies and evaluations.

Sample 3 consisted of 352 MTurkers. We inserted two instructional attention checks, and only those who answered at least one of them correctly were retained. We closely replicated the procedure and measures used in Sample 2a. The only difference was the order of measures. In Study 2, diversity ideologies were assessed after evaluating cases and judgment factors. In this study, we presented them first to rule out the possibility of an order effect.

We conducted a confirmatory factory analysis (CFA) on the 28 items retained in Study 2, resulting in the same five-factor structure with 20 items (see the Supplementary material for details). Most of the removed items originated from misrepresentation and honorific intent. For misrepresentation, the removed items mostly reflect redundancy. For honorific intent, item reduction resulted in the loss of items representing freedom of self-expression but did not significantly alter the overall interpretation of this factor (see Table 4).

In the hierarchical regressions, demographic variables accounted for 16% and 8% of the variance in the first step. Women and social liberals perceived more wrongness in serious cases; younger adults, economic liberals, and ethnic minorities perceived more wrongness in minor cases, whereas social liberals perceived less wrongness. Next, diversity ideologies accounted for an additional 7% and 14% of the variance. CB uniquely was correlated with more lenient judgment in serious cases only, β = 0.22, p < 0.001. MC uniquely was correlated with harsher judgment in both types of cases, respectively, β = −0.17, p = 0.006, and β = −0.13, p = 0.04. PC uniquely was correlated with more lenient judgment in both types of cases, β = 0.11, p = 0.05, and β = 0.43, p < 0.001, respectively (see Supplementary Table S8). This result pattern fully replicated the Sample 2a findings.

Following the same procedure in Study 2, we constructed the path model by first linking diversity ideologies, judgment factors, and evaluation based on bivariate correlations. We used factor scores generated by CFA for judgment factors. Figure 6 shows the final model: χ2(25) = 25.54, p = 0.72; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = 0.00; 90% CI [0.000, 0.033]; SRMR = 0.018. Unexpectedly, misrepresentation was associated with more, rather than less, lenient judgment of minor cases, although the effect was small.

Figure 6. Path model showing the indirect effects of diversity ideologies on judgment (sample 3). Standardized coefficients are displayed. The effects of demographic variables were controlled for. The direct effects of colorblindness and polyculturalism on judgment of serious cases and a direct effect of polyculturalism on judgment of minor cases remained. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001.

A comparison with the Sample 2a path model indicates the indirect effects of MC were fully replicated. The associations between MC and judgment of serious cases were mediated by increased concerns reflected in misrepresentation (b = −0.32, 95% CI [−0.457, −0.204]), permission (b = −0.15, 95% CI [−0.265, −0.057]), as well as the benefits reflected in honorific intent (b = 0.17, 95% CI [0.076, 0.267]). The associations between MC and judgment of minor cases were mediated by all four factors: misrepresentation (b = 0.06, 95% CI [0.005, 0.128]), permission (b = 0.119, 95% CI [−0.228, −0.029]), distinctiveness (b = −0.25, 95% CI [−0.390, −0.115]), and honorific intent (b = 0.11, 95% CI [0.042, 0.183]). In both cases, the overall indirect effects were negative (serious cases: B = −0.31, 95% CI [−0.416, −0.205]; minor cases: B = −0.20, 95% CI [−0.273, −0.125]) such that the perceived costs outweighed the benefits, resulting in overall negative evaluations.

Second, the indirect effects of PC were largely replicated. Like Sample 2a, the associations between PC and judgment of serious cases were mediated by reduced concerns about permission (b = 0.07, 95% CI [0.023, 0.133]); the associations between PC and judgment of minor cases were mediated by reduced concerns about permission (b = 0.05, 95% CI [0.012, 0.112]) and distinctiveness (b = 0.10, 95% CI [0.047, 0.172]). Unlike Sample 2a, the indirect pathway through honorific intent was not significant. The overall indirect effects of PC were positive (B = 0.15, 95% CI [0.093, 0.219]), resulting in overall lenient judgment.

Third, the indirect effects of CB were not replicated. In Sample 2a, CB was associated with more lenient judgment via reduced concerns about misrepresentation. In Sample 3, the following indirect pathways were found instead: increased concerns about permission (serious cases: b = −0.03, 95% CI [−0.059, −0.008]; minor cases: b = −0.02, 95% CI [−0.052, −0.004]) and distinctiveness (minor cases: b = −0.06, 95% CI [−0.103, −0.023]), as well as increased relevance of honorific intent (serious cases: b = 0.05, 95% CI [0.019, 0.082]; minor cases: b = 0.03, 95% CI [0.010, 0.062]). The total indirect effect of CB was non-significant in serious cases (B = 0.02, 95% CI [−0.009, 0.057]), suggesting that the indirect effects of permission and honorific intent canceled each other out. The total indirect effect of CB was negative in minor cases (B = −0.04, 95% CI [−0.081, −0.012]), resulting in overall harsh judgment. The bivariate correlations between CB and judgment factors are notably different in Sample 3. To summarize, we largely replicated the indirect effects of MC and PC but not those of CB.

Study 4 was a preregistered direct replication of the findings from Sample 2b (https://aspredicted.org/blind.php?x=RDL_DXM). We preregistered the following hypotheses: First, the key hypothesis was that MC would predict a lower condemnation threshold, whereas CB and PC would predict higher condemnation thresholds. Second, we made the following predictions regarding the indirect effects of diversity ideologies: Given the consistently demonstrated indirect effects of MC across studies, we expected MC to predict a lower condemnation threshold via all four judgment factors. Next, we expected PC to predict a higher condemnation threshold via reduced permission and distinctiveness concerns as both pathways were consistently found across studies. Finally, because the indirect effects of CB were not coherent, we made no specific predictions.4

Before the data collection, we conducted Monte Carlo simulations to determine the sample size for regression-based analyses (Muthén and Muthén, 2002). Unlike a simple power analysis for a multiple regression model, in which several predictors collectively explain a particular amount of variance, our interest lay in estimating the sample size needed for a model in which a specific regression coefficient is expected for each predictor. To that end, we fitted a population model with regression parameters from the hierarchical regression analysis of diversity ideologies in Sample 2b and simulated 1,000 samples of this regression model using the lavaan and simsem packages in R (Beaujean, 2014). Multiple sample size simulations indicated that an N of 400 would yield >0.92 power for detecting the three diversity ideologies' regression coefficients observed in Sample 2b.

We recruited 425 participants on Prolific (Sample 4) to account for attrition due to attention check failure. The survey included one instructional attention check; those who answered it correctly were retained, resulting in a final sample of 389. We closely replicated the procedure used in Sample 2b except that, as in Study 3, measures of diversity ideologies were presented first.

The confirmatory factor analysis reproduced the same factor structure with 21 items (see the Supplementary material for details). Like Study 3, most removed items originated from misrepresentation and honorific intent. For misrepresentation, item reduction did not alter the overall interpretation of the factor. For honorific intent, however, item reduction resulted in losing items representing positive civic effects. Thus, the remaining items represent this factor more narrowly (see Table 4).

In a hierarchical regression, demographic variables accounted for 25% of the variance. Women, younger adults, and social liberals showed lower condemnation thresholds. Diversity ideologies accounted for an additional 9% of the variance. Whereas, MC was correlated with a lower condemnation threshold, β = −0.27, p < 0.001, both CB and PC were correlated with higher thresholds, β = 0.17, p < 0.001, and β = 0.12, p = 0.01, respectively (see Supplementary Table S9). Those results replicated the Sample 2b findings, although the effect size became slightly smaller. Thus, our key hypothesis received full support.

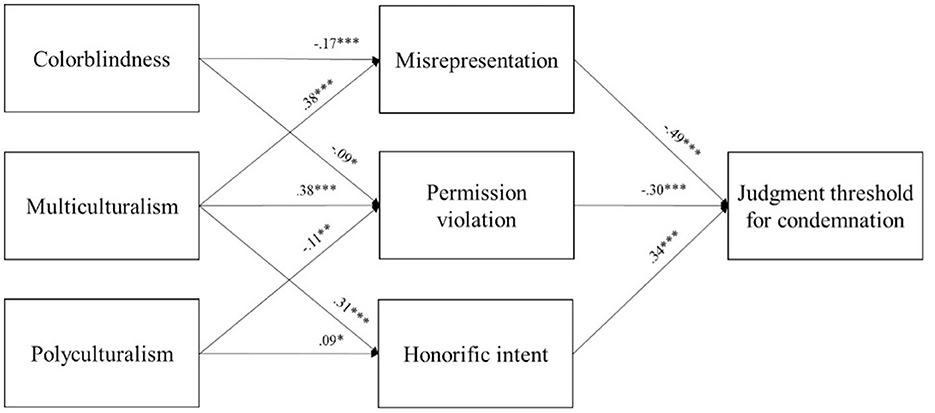

We constructed the initial path model based on our predictions regarding MC and PC. Specifically, we linked all four judgment factors with judgment threshold, on one hand, and MC with all four factors and PC with permission and distinctiveness, on the other. In addition, we linked CB with PC, permission, and distinctiveness based on the bivariate correlations. As in Study 3, we used CFA-generated judgment factor scores and controlled for demographic variables. Although the model fit was acceptable, distinctiveness was not uniquely associated with judgment threshold and was thus removed. We also added one pathway based on the modification indices: the direct effect of CB on judgment threshold. The final model fit was as follows: χ2(15) = 17.50, p = 0.29; CFI = 0.998; RMSEA = 0.021; 90% CI [0.000, 0.055]; SRMR = 0.017 (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Path model showing the indirect effects of diversity ideologies on judgment threshold (sample 4). Standardized coefficients are displayed. The effects of demographic variables were controlled for. There remained a direct effect of colorblindness on condemnation threshold. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001.

Except for distinctiveness, the results fully replicated the indirect effects of MC and PC. MC was correlated with a lower threshold via heightened concerns about misrepresentation (b = −0.80, 95% CI [−1.144, −0.516]) and permission (b = −0.48, 95% CI [−0.726, −0.298]), as well as increased relevance of honorific intent (b = 0.53, 95% CI [0.363, 0.748]). The overall indirect effects of MC were negative (B = −0.75, 95% CI [−1.043, −0.475]), resulting in overall harsh judgment. PC was correlated with a higher threshold via reduced concerns about permission (b = 0.15, 95% CI [0.044, 0.302]). Finally, the CB effects were mediated by reduced concerns about misrepresentation (b = 0.23, 95% CI [0.136, 0.353]) and permission (b = 0.07, 95% CI [0.009, 0.153]). The overall indirect effects of CB were positive (B = 0.30, 95% CI [0.158, 0.464]), resulting in overall lenient judgment. On the whole, our mediation hypotheses received substantial support regarding MC and PC.

We began this research to understand the divide over charges of cultural appropriation from the perspective of diversity ideologies. We proposed that CB, MC, and PC provide ideological lenses for managing competing issues that arise from borrowing across groups. Across five U.S. samples, we consistently found divergent associations between diversity ideologies and evaluations. Consistent with our hypotheses regarding direct associations, MC was associated with harsher judgment, while CB and PC were associated with more lenient judgment. We also systematically explored how diversity ideologies shape evaluations by empirically identifying five judgment factors and subsequently testing the indirect effects of diversity ideologies via four of them. We then conducted internal meta-analyses for a quantitative summary of the overall results (see the Supplementary material for details). Results from the one-stage meta-analytical structural equation modeling approach (Supplementary Tables S11, S12) are largely consistent with direct and indirect effects reported in the individual studies. MC was uniquely associated with harsher judgment via all four factors, whereas CB and PC were associated with more lenient judgments via reduced misrepresentation concerns, on one hand, and reduced permission, as well as distinctiveness concerns, on the other hand.

Apart from the effects of diversity ideologies, the most reliable demographic correlates of judgements were gender, age, and politics on social issues. Women, younger adults, and social liberals were more likely to be critical of cultural borrowing. Together, those demographic variables accounted for between 9% and 32% of the variance. Complementing this, cultural borrowing cases were not all treated equally. The participants distinguished serious from minor cases in our sample cases. This is further confirmed on the measure of condemnation threshold. Most participants indicated that only a small number of consensual appropriative cases are clearly wrong and should be condemned (e.g., a brand profiting from selling indigenous artifacts and wearing stereotypical Halloween costumes; see Supplementary Table S4). These findings underscore that what is often in dispute is where to draw the line between benign or genuine exchange and cultural exploitation or appropriation (Kunst et al., 2024).

The indirect effects of diversity ideologies clarify their prescriptive implications by showing how they orient people to different trade-offs in the costs and benefits of the powerful group's cultural borrowing. MC was consistently associated with perceiving more wrongness with cultural borrowing (in terms of both bivariate associations and partial correlations in multiple regression models), but those overall associations mask countervailing processes revealed in indirect effects. Although MC was associated with more lenient judgment via honorific intent, it was associated with harsher judgment via concerns reflected in misrepresentation, permission violation, and distinctiveness threat. Importantly, the total indirect effects of MC produced an overall critical evaluation. In other words, MC tips the scales toward perceiving more group-based costs, supporting our prediction that MC prioritizes protecting minority groups' rights to their own cultural traditions without encroachment by the powerful group. MC thus aligns most closely with perceiving cultural borrowing as exploitative. Moreover, MC as captured in our measure (Wolsko et al., 2006; except for Study 1) is associated with concerns beyond apparent harms, such as misrepresentation and misuse, to include sensitivity to issues of ownership (who owns a culture?), permission (does a cultural outsider need permission?), and authentic experience (what kind of experience does it take to be a cultural insider?). These additional concerns are often more salient to minority groups (e.g., Mosley and Biernat, 2021). As a whole, MC expresses a cautionary, if not fraught, tale of cultural appropriation and prioritizes protection against the powerful group.

Despite positive correlations with MC across studies, PC was consistently associated with perceiving less wrongness, thus supporting the divergent effects of MC and PC in previous work (Bernardo et al., 2016; Cho et al., 2017; Wilton et al., 2019; Wolsko et al., 2000). Also, in contrast to MC, the consistent indirect effects of PC via reduced permission and distinctiveness concerns suggest that the lessened need for adhering to essentialism to uphold group boundaries represents the PC perspective (Danaher, 2018; Matthes, 2016). Given that contesting notions of ownership, purity, and authenticity are the means for recognizing mixing and fusing cultural styles, those endorsing PC may be less sensitive to the inequality being reproduced in cultural borrowing by the powerful group. This may explain the robust associations between PC and lenient judgment of low-controversy cases such as preparing cuisine in non-traditional ways and mainstream movies retelling stories of minority cultures. Because not all our cases explicitly describe a majority group appropriating from a minority group, it is possible that lessening rigid boundaries between groups takes general precedence over other group-based concerns from the PC perspective. Therefore, PC expresses guarded optimism for cultural borrowing (even by the more powerful group) as it encourages people to regard it as instances of the inevitable yet messy processes by which cultures come to influence each other.

Similar to PC, CB was also associated with more lenient judgment. Results from the indirect effects indicate that reduced misrepresentation concerns robustly explain the overall positive evaluation. This points to one major difference between PC and CB in understanding cultural borrowing. Because arguments predicated on group identities are the least likely to resonate with CB, those endorsing CB may be blind to the possibility that the more powerful group's borrowing devalues or harms the appropriated culture. In fact, part of its appeal lies in its potential to be co-opted by the dominant group to justify the existing racial hierarchy (Apfelbaum et al., 2008; Knowles et al., 2009; Neville et al., 2013). In contrast, PC was consistently and positively associated with misrepresentation concerns at the bivariate level (Table 3), and misrepresentation did not mediate its overall positive evaluation of cultural borrowing (Supplementary Table S12). Moreover, other indirect effects of CB are less coherent. For example, CB was associated with increased permission and distinctiveness concerns, as well as increased honorific intent, in Sample 3, which deviates from what was found in other samples. Overall, CB expresses a laissez-faire attitude toward cultural borrowing on the grounds of dismissing group-based complaints.

We empirically derived five factors pertaining to the costs and benefits believed to be accrued from cultural borrowing, making an important contribution to delineating the basis of judging when cultural boundary-crossing is permissible or not (also see Oshotse et al., 2024) Intent to insult and misrepresentation reflect concerns that clearly argue against cultural borrowing, while honorific intent speaks to the converse. Interestingly, in part evidenced by their relevance being rated around the scale's midpoint, permission violation and distinctiveness threat could be described as gray areas. Although both tended to be associated with more negative evaluations, how much they were considered depended on the ideology.

Permission and distinctiveness raise questions of how to properly define culture and, by extension, distinguish cultural insiders from outsiders. After all, the interrelated issues of ownership, authenticity, and consent presuppose a clear, or at least practical, demarcation of cultural boundaries (Lenard and Balint, 2020; Lindholm, 2007; Matthes, 2016; Scafadi, 2005). Previous work shows that compared to majority groups, minority groups are more sensitive to distinctiveness threat, which explains their differences in perceptions of cultural appropriation (Mosley and Biernat, 2021). Our work adds to the understanding by linking these concerns with support for different diversity ideologies. Particularly, permission and distinctiveness reflect the crux of the differences between MC and PC. Because most cases in our studies are described as borrowing by the majority group, the two ideologies differ in how much the minority source group is factored in. MC reflects a protectionist mindset and requires distinct boundaries to guard against the majority group's intrusion and exploitation. Because PC sees rigid boundaries as stifling intergroup exchanges, the consideration is not so much how much the majority group stands to benefit at the cost of the minority source group as the fact that preventing cultural boundary-crossing creates another source of harm (Danaher, 2018; Matthes, 2016).

Intent to insult and misrepresentation parallel the widely documented distinction between intent- and outcome-based5 moral judgments (e.g., Cushman, 2008; Young and Tsoi, 2013). Notably, intent to insult was rated most relevant in all samples, irrespective of diversity ideologies. Intentions play a pivotal role in moral judgments in Western and industrialized populations (Barret et al., 2016). Our results with American participants extend the predominance of sensitivity to mental states in moral judgments to perceptions of cultural appropriation. Cultural borrowing is unanimously wrong when it is intended as a cultural offense. In fact, cultural offense may be considered a necessary condition for appropriation charges (Kunst et al., 2024; Lenard and Balint, 2020). However, one remaining puzzle is the lack of a parallel distinction between positive intent and positive consequences—they were largely collapsed into one factor (honorific intent). This asymmetry might mean that people are more responsive to clues of negative (vs. positive) intent in evaluating cultural borrowing, perhaps particularly so by the powerful group. That negative intent is more revealing of the person performing a potentially harmful act of borrowing than positive intent may be a case of the Knobe effect (Knobe, 2003; Holton, 2010).

We lay out a few important limitations that could be addressed in future research. First, although the path models reveal how diversity ideologies may influence evaluations, the correlational data constrain the causal inferences we are allowed to make. Future research should follow established experimental paradigms to manipulate diversity ideologies (e.g., Cho et al., 2017; Vorauer and Sasaki, 2010; Wolsko et al., 2000). Second, our online samples are not very racially diverse, which precluded a closer examination of potential differences between majority and minority groups shown in previous research. Although we did find that non-white participants judged cultural borrowing slightly more harshly in some samples, we did not examine racial differences in the direct or indirect effects of diversity ideologies (e.g., Ryan et al., 2007; Verkuyten, 2005). Sample 3 is the least racially homogeneous and produced results that are least coherent with the other samples. Future research could test whether the influence of diversity ideologies is moderated by group status.

Third, although the five factors of costs and benefits have the strength of being empirically supported by exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis, more work is needed toward a comprehensive understanding of conditions that dial up or down perceptions of cultural appropriation. Considerable connections and notable differences exist between the factors that emerged from this work and those suggested or shown in other independent lines of work. On one hand, along with the present research, this growing work on perceptions of cultural appropriation starts to sketch out a few common ingredients (Finkelstein and Rios, 2022; Kunst et al., 2024; Lenard and Balint, 2020; Mosley and Biernat, 2021; Mosley et al., 2023b): power/status difference, misrepresentation/misuse, cultural knowledge/ignorance, consent/permission, group identity threat, and cultural appreciation/investment. On the other hand, other work highlights factors muted or absent from the current set of studies. Take financial gain as an example. Originally proposed as a reason against cultural borrowing by the majority group because minority groups' cultural products are exploited without compensation (Brown, 1998; Jackson, 2019; Scafadi, 2005; Young, 2008), its items failed to form another factor or cluster with other items in our samples. This could mean that for an average liberal-leaning white American, material benefits conferred on the majority group via cultural adoption are not salient enough. This underscores individual and group differences in the saliency of common judgment factors and, as a result, how they are weighted in predicting perceptions of cultural appropriation. The number of factors considered may be elastic such that some people and groups consider an expanded set of factors and differentiate among them more sharply than others.

Finally, our measures of diversity ideologies do not exhaust the different ways they have been conceptualized. Recent work has questioned the construct validity of existing measures of CB (Whitley and Webster, 2019) and revealed distinct components of CB, which were differentially related to racial prejudice (Whitley et al., 2023). Measurement issues may thus explain the mixed findings regarding the indirect effects of CB. Given the recent findings suggesting that CB's power-evasion manifestation may distinctly facilitate an ahistorical view of cultural appropriation (Mosley et al., 2023a), future research should examine the potentially divergent effects of CB components on judgments of cultural appropriation. Similarly, Rosenthal and Levy's measure of PC used in our studies is valence-free in that it does not prompt people to think about negative interactions, such as intergroup conflict and colonization. This could have exaggerated the differences between PC and MC because people endorsing this version of PC may not have attended adequately to inequality resulting from negative intergroup interactions. PC may be similarly multifaceted (Verkuyten et al., 2020); more refined measures will yield additional insights into PC as a new diversity ideology. Finally, the notion of something new emerging from intercultural influence is somewhat captured in the items assessing honorific intent, but PC was not consistently associated with honorific intent, which merits further research.

Returning to what motivated this research, what explains the range of public opinions over cultural appropriation? Our findings suggest diversity ideologies prescribe different cost/benefit calculations. On the one hand, critics of cultural appropriation may be motivated by MC. Not only do they tend to argue that many cases cause symbolic or structural harm, but they may also have additional reservations about group rights and distinctiveness. On the other hand, defenders of cultural appropriation may be motivated by either CB or PC. Some tend to either dismiss group-based concerns as largely immaterial, while others see many cases accusations of appropriation as reflecting or promoting intercultural connections. This overall picture has two practical implications. First, people have different prior beliefs about where to draw the line about cultural appropriation when important contextual details are missing. Second, even when contextual information is available, people will likely show different sensitivities. If information consonant with the embraced ideology is present, it should be weighed more heavily in the judgment.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://osf.io/9jq5v/?view_only=b153c20867ed4dd9bdd7647a58b42634.

The studies involving humans were approved by the Dickinson College Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

RZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. JC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. MM: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. LC: Formal analysis, Visualization, Software, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by Dickinson College research and development grants awarded to Rui Zhang and a grant from the Chazen Global Research Fund issued to Michael W. Morris by the Jerome A. Chazen Institute for Global Business.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsps.2025.1477434/full#supplementary-material

1. ^We first checked the study variables for normality. Both MC and PC showed a moderate degree of negative skewness in this study and all subsequent studies. Additionally, the judgment of minor cases in Samples 2a and 3 showed negative skewness, reflecting that those cases were judged to be not particularly wrong. Importantly, data transformations aimed at reducing skewness did not change the results in any of the studies. Therefore, we present the results based on analyses without data transformation.

2. ^Given the limited ethnic diversity in all samples, we created a simple dichotomous variable in each sample contrasting whites with non-whites.

3. ^In hierarchical regression analyses of the subsequent studies, all VIFs were below 3.

4. ^Due to our oversight, we failed to preregister the indirect effects via honorific intent.

5. ^Within misrepresentation, items pertaining to ignorance (and negligence) may be considered a mental state rather than a consequence per se. Typically, ignorance of a negative outcome counts as a mitigating factor in moral judgment. In the context of cultural appropriation, however, offense may still be taken at ignorance because one should have known better (e.g., ignorance is no excuse for causing harm). That is, even if ignorance represents unintended harm, it may be perceived as unjustifiable inattention to the likely negative consequences (Lenard and Balint, 2020; Young et al., 2010). This property of ignorance in relation to cultural appropriation makes it similar to negligent harm, which is somewhere between accidental and intentional harm (Malle et al., 2014).

Apfelbaum, E. P., Norton, M. I., and Sommers, S. R. (2012). Racial color blindness: emergence, practice, and implications. Curr. Direct. Psychol. Sci. 21, 205–209. doi: 10.1177/0963721411434980

Apfelbaum, E. P., Pauker, K., Sommers, S. R., and Ambady, N. (2010). In blind pursuit of racial equality? Psychol. Sci. 21, 1587–1592. doi: 10.1177/0956797610384741

Apfelbaum, E. P., Sommers, S. R., and Norton, M. I. (2008). Seeing race and seeming racist? Evaluating strategic colorblindness in social interaction. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 95, 918–932. doi: 10.1037/a0011990

Avins, J. (2015). “The dos and don'ts of cultural appropriation. Borrowing from other cultures isn't just inevitable, it's potentially positive,” The Atlantic. Available online at: https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2015/10/the-dos-and-donts-of-cultural-appropriation/411292/ (accessed online at: October 20, 2015)

Barret, H. C., Bolyanatz, A., Crittenden, A. N., Fessler, D. M. T., Fitzpatrick, S., Gurven, M., et al. (2016). Small-scale societies exhibit fundamental variation in the role of intentions in moral judgment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 113, 4688–4693. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1522070113

Beaujean, A. (2014). Sample size determination for regression models using Monte Carlo methods in R. Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation, 19, n12. doi: 10.7275/d5pv-8v28

Bernardo, A. B. I., Salanga, M. G. C., Tjipto, S., Hutapea, B., Yeung, S. S., Khan, A., et al. (2016). Contrasting lay theories of polyculturalism and multiculturalism: associations with essentialist beliefs of race in six Asian cultural groups. Cross-Cult. Res. 50, 231–250. doi: 10.1177/1069397116641895

Cho, J., Chao, M., Zhang, R., Morris, M. W., and Choi, J. M. (2025). Who sees cultural appropriation? The role of political orientations and moral foundations. Manuscript under review.

Cho, J., Morris, M. W., Slepian, M. L., and Tadmor, C. T. (2017). Choosing fusion: the effects of diversity ideologies on preference for culturally mixed experiences. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 69, 163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2016.06.013

Cho, J., Tadmor, C. T., and Morris, M. W. (2018). Are all diversity ideologies creatively equal? The diverging consequences of colorblindness, multiculturalism, and polyculturalism. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 49, 1376–1401. doi: 10.1177/0022022118793528

Cobb, C. L., Lilienfeld, S. O., Schwartz, S. J., Frisby, C., and Sanders, G. L. (2020). Rethinking multiculturalism: toward a balanced approach. Am. J. Psychol. 133, 275–293. doi: 10.5406/amerjpsyc.133.3.0275

Correll, J., Park, B., and Smith, J. A. (2008). Colorblind and multicultural prejudice reduction strategies in high-conflict situations. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 11, 471–491. doi: 10.1177/1368430208095401

Cushman, F. (2008). Crime and punishment: distinguishing the roles of causal and intentional analyses in moral judgment. Cognition 108, 353–380. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2008.03.006

Danaher, J. (2018). “Is the criticism of cultural appropriation self-defeating? Thoughts on the paradox of cultural appropriation,” Philosophical Disquisitions. Available online at: https://philosophicaldisquisitions.blogspot.com/2018/08/is-criticism-of-cultural-appropriation.html (accessed online at: August 31, 2018).

Finkelstein, S. R., and Rios, K. (2022). Cultural exploitation or cultural exchange? The roles of perceived group status and others' psychological investment on reactions to consumption of traditional cultural products. Psychol. Market. 39, 2349–2360. doi: 10.1002/mar.21728

Frum, D. (2018). “Every culture appropriates. The question is less whether a dress or an idea is borrowed, than the uses to which it's then put,” The Atlantic. Available online at: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2018/05/cultural-appropriation/559802/ (accessed online at: May 8, 2018).

Fryberg, S. A., Markus, H. R., Oyserman, D., and Stone, J. M. (2008). Of warrior chiefs and Indian princesses: The psychological consequences of American Indian mascots. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 30, 208–218. doi: 10.1080/01973530802375003

Graham, J., Haidt, J., and Nosek, B. A. (2009). Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 96, 1029–1046. doi: 10.1037/a0015141

Gutiérrez, A. S., and Unzueta, M. M. (2010). The effect of interethnic ideologies on the likability of stereotypic vs counterstereotypic minority targets. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 46, 775–784. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2010.03.010

Hahn, A., Banchefsky, S., Park, B., and Judd, C. M. (2015). Measuring intergroup ideologies: positive and negative aspects of emphasizing vs. looking beyond group differences. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 41, 1646–1664. doi: 10.1177/0146167215607351

Johnson, M. Z. (2015). “What's wrong with cultural appropriation? These 9 answers reveal its harm,” Everyday Feminism. Available online at: https://everydayfeminism.com/2015/06/cultural-appropriation-wrong/ (accessed online at: June 14, 2015).

Knobe, J. (2003). Intentional action and side effects in ordinary language. Analysis 63, 190–193. doi: 10.1093/analys/63.3.190

Knowles, E. D., Lowery, B. S., Hogan, C. M., and Chow, R. M. (2009). On the malleability of ideology: Motivated construals of colorblindness. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 96, 857–869. doi: 10.1037/a0013595

Kunst, J. R., Lefringhausen, K., and Zagefka, H. (2024). Delineating the boundaries between genuine cultural change and cultural appropriation in majority-group acculturation. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 98:101911. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2023.101911

Lenard, P. T., and Balint, P. (2020). What is (the wrong of) cultural appropriation? Ethnicities 20, 331–352. doi: 10.1177/1468796819866498

Leslie, L. M., Bono, J. E., Kim, Y., and Beaver, G. R. (2020). On melting pots and salad bowls: a meta-analysis of the effects of identity-blind and identity-conscious diversity ideologies. J. Appl. Psychol. 105, 453–471. doi: 10.1037/apl0000446

Malik, K. (2017). In Defense of Cultural Appropriation. New York City: The New York Times. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/14/opinion/in-defense-of-cultural-appropriation.html (accessed online at: June 14, 2017).

Malle, B. F., Guglielmo, S., and Monroe, A. E. (2014). A theory of blame. Psychol. Inquiry, 25, 147–186. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2014.877340

Matthes, E. H. (2016). Cultural appropriation without cultural essentialism? Soc. Theor. Pract. 42, 343–366. doi: 10.5840/soctheorpract201642219

Morris, M. W., Chiu, C. Y., and Lui, Z. (2015). Polycultural psychology. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 66, 631–659. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015001

Mosley, A. J., and Biernat, M. (2021). The new identity theft: perceptions of cultural appropriation in intergroup contexts. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 121, 308–331. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000327

Mosley, A. J., Biernat, M., and Adams, G. (2023a). Sociocultural engagement in a colorblind racism framework moderates perceptions of cultural appropriation. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 108:104487. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2023.104487

Mosley, A. J., Heiphetz, L., White, M. H., and Biernat, M. (2023b). Perceptions of harm and benefit predict judgments of cultural appropriation. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 5, 299–308. doi: 10.1177/19485506231162401

Muthén, L. K., and Muthén, B. O. (2002). How to use a Monte Carlo study to decide on sample size and determine power. Struct. Eq. Model. 9, 599–620. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0904_8

Nederveen Pieterse, J. (2009). Globalization and culture: Global mélange (2nd ed.). Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

Neville, H. A., Awad, G. H., Brooks, J. E., Flores, M. P., and Blumel, J. (2013). Color-blind racial ideology: theory, training, and measurement implications in psychology. Am. Psychol. 68, 455–466. doi: 10.1037/a0033282

Nittle, N. K. (2019). A Guide to Understanding and Avoiding Cultural Appropriation. New York: ThoughtCo. Available online at: https://www.thoughtco.com/cultural-appropriation-and-why-iits-wrong-2834561 (accessed online at: July 3, 2019).

Oppenheimer, D. M., Meyvis, T., and Davidenko, N. (2009). Instructional manipulation checks: detecting satisficing to increase statistical power. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 45, 867–872. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2009.03.009

Oshotse, A., Berda, Y., and Goldberg, A. (2024). Cultural tariffing: appropriation and the right to cross cultural boundaries. Am. Sociol. Rev. 89, 346–390. doi: 10.1177/00031224231225665

Oxford English Dictionary (2018). “New words notes March 2018,” OED.com dictionary. Available online at: https://public.oed.com/blog/march-2018-new-words-notes/ (Retrieved May 28, 2020).

Plaut, V. C. (2010). Why and how difference makes a difference. Psychol. Inquiry. 21, 77–99. doi: 10.1080/10478401003676501