- 1Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, University of North Florida, Jacksonville, FL, United States

- 2Department of Psychology, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, United States

- 3Office of Institutional Effectiveness, University of North Florida, Jacksonville, FL, United States

Within the United States (U.S.), the political landscape is polarized between two major parties: the Democratic Party and the Republican Party. Elite polarization has led to legislative gridlock and labeling the ‘other' major party as different, which hinders social change because less receptivity to the other party's ideas and less willingness to accept criticism from members of the other party. Non-major political groups and political independents are essential but understudied routes to social change because they may not be perceived as electoral and viewpoint competition to major political groups. Previous literature has examined the stereotypes of major as opposed to non-major political groups and political independents. The present research examines how fundamental stereotypes (warmth and competence) are associated with Republicans, Democrats, Libertarians, and political independents and the implications of those stereotypes for a critical intergroup outcome (i.e., dehumanization). In a sample of undergraduates (agemedian = 20) and a sample of older adults (agemedian = 34), fundamental stereotypes about major political groups but not Libertarians or independents reflect perceived competition. The pattern of fundamental stereotypes applied to Libertarians and independents is consistent with stereotypes of admired groups and our hypothesis that non-major political groups and political independents can be a vector for social change. Further, fundamental competence stereotypes about one's own major political group were associated with the dehumanization of the other major political group. In contrast, fundamental stereotypes of major political groups were not associated with the dehumanization of Libertarians or independents. Given that non-major political groups and political independents are not viewed as competition to major political groups, future research should examine how non-major political groups and political independents could reduce political polarization in the U.S.

Introduction

In the United States, two major political parties (and their associated animal mascots) dominate: the Republican Party (whose mascot is the elephant) and the Democratic Party (whose mascot is the donkey). Political party membership influences our lives in many ways, including but not limited to how we vote, our mate preferences (Hersh, 2016), where we want to live (Gimpel and Hui, 2015), what we buy (Michelitch, 2015; McConnell et al., 2018), and our employment (Gift and Gift, 2015; McConnell et al., 2018). Identifying with a major political party acts as a social category membership (i.e., Greene, 1999; Huddy et al., 2015; Iyengar et al., 2019; Theodoridis, 2017) that can lead to seeing the two parties as opposites (Layman et al., 2006). For example, the stereotypes of major political parties include negativity toward “opposing” parties (i.e., beliefs that the “opposing” party is two-faced, self-interested, and narrowminded; Iyengar et al., 2019). This framework of perceiving major political parties as competing materializes not only through competition within the electoral system but also through perceptions among members of major political parties that the other party is not aligned with their political values and goals. We argue that framing major political parties as competing hinders social change. A potential solution may lie in non-major political groups and political independents that may not be seen as competing with one's own major political group. Despite 40% of voters identifying as politically independent (Jones, 2022) and non-major political parties playing a critical role in recent U.S. Presidential elections (e.g., 2000, 2016), little research explores the stereotypes–especially the fundamental stereotypes of warmth and competence–of non-major political groups and political independents (Abramowitz and Saunders, 2006; Brady and Sniderman, 1985; Clifford, 2020; Goggin and Theodoridis, 2017; Goggin et al., 2020; Petrocik, 1996; Rothschild et al., 2019; Winter, 2010). The current research examines whether a non-major political group and political independents could be vectors for social change by studying whether they are perceived as ‘opposing' the major political groups.

Opposing parties

The major political parties in the United States (i.e., Democrats and Republicans) have become increasingly polarized since the 1970s (Layman et al., 2006). For the past 30 years, this polarization among political elites has grown (Enders, 2021), as evidenced by major political parties distancing themselves from one another on roll call votes (McCarty et al., 2006). As such, Democrats have become more liberal, and Republicans have become more conservative (Shor and McCarty, 2022). Unfortunately, polarization among elected politicians leads to less efficient governments (Sørensen, 2014) and legislative gridlock (Binder, 2004; Hughes and Carlson, 2015; Jones, 2001), which hinders social change. This polarization is partly driven by political parties (Canen et al., 2021) and political party identification (Twenge et al., 2016). Perceiving party identification as a social identity can thwart social change because people perceive their own party as their group and other parties as not being their group (Fielding and Hornsey, 2016) and thus in competition. One consequence is that people may be less receptive to ideas and critiques from members of the other major party because people, in general, are less defensive when receiving criticism from the members of their own group (Hornsey and Imani, 2004) and are less likely to evaluate the “rightness” of a message from an outsider (Esposo et al., 2013). This tendency among political elites to perceive the “other” political party as a competing group may also be related to worsening civility in political advertisements (Layman et al., 2006) and increases in uncivil speech in Congress (Jamieson and Falk, 2000).

While polarization among political elites is greater than polarization among the mass public (Enders, 2021), some scholars have indicated that polarization among the mass public is also increasing (Abramowitz and Saunders, 2008; Enders, 2021).1 Among the electorate, perceived mass polarization is related to negative evaluations of the other major political party, of other major political party candidates, and lower voting participation (Enders and Armaly, 2019). Thus, salient political identification influences political beliefs (Unsworth and Fielding, 2014), evaluations (Enders and Armaly, 2019), and behavior (Esposo et al., 2013; Hornsey and Imani, 2004), facilitating both elite and mass political polarization.

However, elite polarization, mass polarization, and partisanship can be overcome. For instance, when political identification is not salient, the public evaluates the merits of proposed political policies (Cohen, 2003) instead of using political party identification to determine their preferred position (Dalton, 2021). Alternatively, making a superordinate group salient also helps individuals overcome biases associated with political party identification (Transue, 2007). The current research explores another avenue for overcoming mass polarization: non-major political groups and political independents. In the U.S., while 60% percent of citizens identify with one of the two major political parties (Laloggia, 2019), 40% identify as independents (meaning they do not identify as Republicans or Democrats; Jones, 2022). Although three-quarters of those identifying as independents ‘lean' toward one of the major parties and tend to vote with that party, they can diverge on social issues (Laloggia, 2019). For example, even though 37% of people who identified with the Republican Party in 2019 believed gays and lesbians should be allowed to marry, almost 60% of people who identified as independent but ‘leaned' Republican supported equal marriage (Laloggia, 2019). Since stereotypes can help or hinder polarization by affecting intergroup outcomes (Prati et al., 2015), we examined whether a non-major political group and political independents can drive social change. The current research explores the stereotypes associated with Republicans, Democrats, Libertarians, and independents and their implications for a critical intergroup outcome.

Fundamental stereotypes and political groups

Stereotypes consist of beliefs, knowledge, and expectations associated with a formal or informal group (Sherman et al., 2005). When the content of stereotypes is well-rehearsed through repeated exposure, encountering a group member will bring stereotypes about the group to mind (Devine, 1989; Macrae et al., 1997). Two fundamental dimensions of stereotypes are competence (a self-orientation) and warmth (an other orientation; Cuddy et al., 2008; Fiske et al., 2002; Nicolas et al., 2022). Competence consists of traits such as intelligence, frivolous, industrious, independent, and ignorant, while warmth consists of traits such as conceited, sensitive, faithful, arrogant, and honest (Fiske et al., 2002). These fundamental dimensions of stereotypes have been studied in many groups, including housewives, the elderly, poor Black people, poor white people, welfare recipients, southerners, sexy women, feminists, the wealthy, Black professionals, Hispanics, and Asians (Fiske et al., 2002).

No published research has examined how fundamental stereotypes are associated with the major political groups, but they have been examined for political ideological groups (Crawford et al., 2013). Political groups are commonly seen as synonymous with political ideologies, such that Republicans are associated with conservatism (Abramowitz and Saunders, 2006; Brady and Sniderman, 1985; Rothschild et al., 2019), and Democrats are associated with liberalism (Abramowitz and Saunders, 2006; Brady and Sniderman, 1985; Rothschild et al., 2019). Thus, the warmth and competence stereotypes associated with liberals and conservatives could apply to beliefs about Democrats and Republicans. Regardless of the participants' political ideology (conservative, moderate, or liberal), participants perceived conservatives as higher on competence than warmth and liberals as equally high on competence and warmth (Crawford et al., 2013). We explore whether this pattern of results also occurs for political groups. We also examined the patterns of competence and warmth stereotypes for a well-known non-major political group (Libertarians) and independents. It is unclear how a non-major political group and political independents will be rated; if a non-major political group and political independents are rated high on both fundamental stereotypes, they would not be perceived as in competition with major political groups, meaning they could be a possible vector for social change.

We also examined whether participant political party identification plays a role. Given that politics is a masculine domain (Schneider and Bos, 2019) and agency (which includes competence) is typically ascribed to men (Eagly et al., 2000), major political groups, non-major political groups, and political independents should be ascribed the same competence. However, because one's own group is perceived as high on both warmth and competence (Cuddy et al., 2007, 2008), especially when people highly identify with their group (Kervyn et al., 2008), participant political party identification should play a role in the warmth and competence ascribed to a political group. Because the major political parties compete in the U.S. electoral system, we predict that people who identify with one of the major parties will rate the competing major political group as lower on competence and warmth. Further, we predict that because non-major political groups and political independents do not represent realistic competition for major political groups, people identifying with a major party will not rate a non-major political group (Libertarians) and political independents lower on competence and warmth.

Fundamental stereotypes and dehumanization

In addition to investigating the fundamental stereotypes associated with major political groups, a non-major political group, and political independents, we also studied the consequences of political group stereotypes for intergroup conflict. In particular, we examined the relationship between fundamental stereotypes and dehumanization. Dehumanization is a process by which individuals' identities are minimized (Kelman, 1973), their associated values are othered (Struch and Schwartz, 1989), and the traits that make us uniquely human are denied (Bain et al., 2009; Haslam et al., 2008). Dehumanization predicts hostility against other groups (Kteily and Bruneau, 2017), is associated with less willingness to help other groups (Andrighetto et al., 2014), and has a bidirectional relationship with negative intergroup contact (Capozza et al., 2017). While groups with varying levels of competence and warmth can be dehumanized (Boysen et al., 2023), groups perceived as lower on warmth or competence experience more dehumanization (Boysen et al., 2023; Harris and Fiske, 2006; Kuljian and Hohman, 2022; Vaes and Paladino, 2009).

We anticipate that fundamental stereotypes about political groups will be associated with dehumanization. Because major political parties are perceived as competing electorally, competing in terms of viewpoints, and are often inferred as opposing one another in the U.S. political system, the fundamental stereotypes about an individual's own identified major party will be associated with greater dehumanization of the other major political group. However, if non-major groups are not perceived as competing with the major political groups, fundamental stereotypes about the major political groups should not be associated with dehumanization of a non-major political group and political independents, indicating non-major political groups and political independents can be a possible vector for social change.

Overview

Two studies examined whether a non-major political group (Libertarians) and independents are perceived as not ‘opposing' major political groups. We measured the extent to which fundamental competence and warmth stereotypes were associated with Republicans, Democrats, Libertarians, and independents and how those stereotypes were related to dehumanization. We had two groups of hypotheses. The first hypotheses concern how fundamental stereotypes are associated with Republicans, Democrats, Libertarians, and independents.

Hypothesis 1

Republicans, Democrats, Libertarians, and independents will show different patterns of association with fundamental stereotypes.

Hypothesis 1a. Because politics is associated with masculinity, major political groups (Republicans and Democrats) will be perceived as equal in competence.

Hypothesis 1b. Consistent with the literature on political ideology (Crawford et al., 2013), Republicans will be perceived as higher on competence than warmth. In contrast, Democrats will be perceived as equal in competence and warmth. Because non-major political groups and political independents are not associated with a major political party and are not perceived as in competition with major political groups, they will be perceived as high on competence and warmth.

Hypothesis 1c. Because Republicans and Democrats compete electorally and in terms of viewpoints in the U.S. political system, people identifying with one of the major political parties will rate the competing major political group as lower on competence and warmth. Additionally, because Libertarians and political independents do not compete with Republicans and Democrats, people identifying with one of the major political parties will not rate Libertarians and political independents as lower on competence and warmth.

Exploratory analyses

We also examined whether dehumanization of major political groups (Republicans, Democrats), members of non-major political groups (Libertarians), and political independents differed depending on participants' political party identification.

Hypothesis 2

The second group of hypotheses concerns the relationship between fundamental stereotypes and dehumanization.

Hypothesis 2a. Fundamental stereotypes about major political groups will be associated with greater dehumanization of the other major political group.

Hypothesis 2b. Fundamental stereotypes about an individual's own identified major political group will be associated with greater dehumanization of the other major political group but will not be associated with the dehumanization of Libertarians and political independents.

All data and analysis code are stored on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/ge9rb/?view_only=e95244fea72b4e46a0fa2e424c471281).

Studies 1 and 2

Although conceptually and procedurally similar, Studies 1 and 2 were collected from different samples of participants within the United States. Study 1 utilized a sample of undergraduate students taking psychology classes, whereas Study 2 utilized an older online sample of adults.

Method

Participants and procedure

In Study 1, 306 (231 women; 199 white, 37 Black, 27 Hispanic/Latino/Latina, 25 Asian, 18 other; ages 10–52, median age = 20) undergraduate students participated in the study in exchange for partial course credit. Of these students, 281 were currently registered to vote.2 Participants rated their ideology (M = 3.64, SD = 1.54) and their party identification (M = 3.46, SD = 1.89) on scales ranging from 1 (extremely liberal/strong Democrat) to 4 (moderate: middle of the road; pure independent) to 7 (extremely conservative/strong Republican). In comparison to each scale's midpoint, participants leaned more liberal, t(308) = −4.10, p < 0.001, d = −0.233, and were more likely to identify as Democrats, t(308) = −5.00, p < 0.001, d = −0.284, than middle of the road/independent.

In Study 2, 361 (154 women, 200 men; 248 white, 41 Black, 30 Hispanic/Latino/Latina, 24 Asian, 17 other; ages 20–73, median age = 34) individuals within the United States were recruited through Amazon's Mechanical Turk for compensation. Of these participants, 339 were registered to vote, and 297 had voted in the most recent election (2018). Participants rated their ideology (M = 3.52, SD = 1.84) and their party identification (M = 3.46, SD = 2.04) on scales ranging from 1 (extremely liberal/strong Democrat) to 4 (moderate: middle of the road; pure independent) to 7 (extremely conservative/strong Republican). In comparison to each scale's midpoint, participants leaned more liberal, t(359) = −4.92, p < 0.001, d = −0.259, and were more likely to identify as Democrats, t(359) = −5.07, p < 0.001, d = −0.267, than middle of the road/independent.

In Studies 1 and 2, as part of a more extensive study, after consenting to participate, participants rated how society views Republicans, Democrats, Libertarians, and independents on competence and warmth stereotypes and their perceptions of how “evolved” the average member of each group was. Lastly, participants completed demographic information and were debriefed.

Competence and warmth stereotypes for studies 1 and 2

Participants rated groups on eight competence items [competent, intelligent, frivolous (reverse-scored), sophisticated, industrious, lazy (reverse-scored), independent, ignorant (reverse-scored)] and eight warmth items [warm, conceited (reverse-scored), rude (reverse-coded), sensitive, faithful, arrogant (reverse-scored), courteous, honest] (Fiske et al., 2002). Specifically, participants were asked, “as viewed by society, how (competence item/warmth item) are Republicans/Democrats/Libertarians/independents?” and used five-point scales ranging from 1 (not at all) to 3 (neutral) to 5 (extremely) to indicate their response. Competence and warmth composites were separately averaged across Republicans, Democrats, Libertarians, and independents (Study 1: competence: αRepublicans = 0.755; αDemocrats = 0.806; αLibertarians = 0.781; αindependents = 0.684; warmth: αRepublicans = 0.757; αDemocrats = 0.792; αLibertarians = 0.716; αindependents = 0.663; Study 2: competence: αRepublicans = 0.842; αDemocrats = 0.876; αLibertarians = 0.809; αindependents = 0.805; warmth: αRepublicans = 0.857; αDemocrats = 0.856; αLibertarians = 0.818; αindependents = 0.758).

Dehumanization

Participants indicated “using the scale below how evolved” they considered “the average member of each group to be- Republicans/Democrats/Libertarians/independents” using a continuous slider numeric scale underneath an “Ascent of Man” diagram that depicts different stages of human evolution. The numeric slider scale ranged from 0 (least “evolved”) to 100 (most “evolved”) (Kteily et al., 2015).

Results

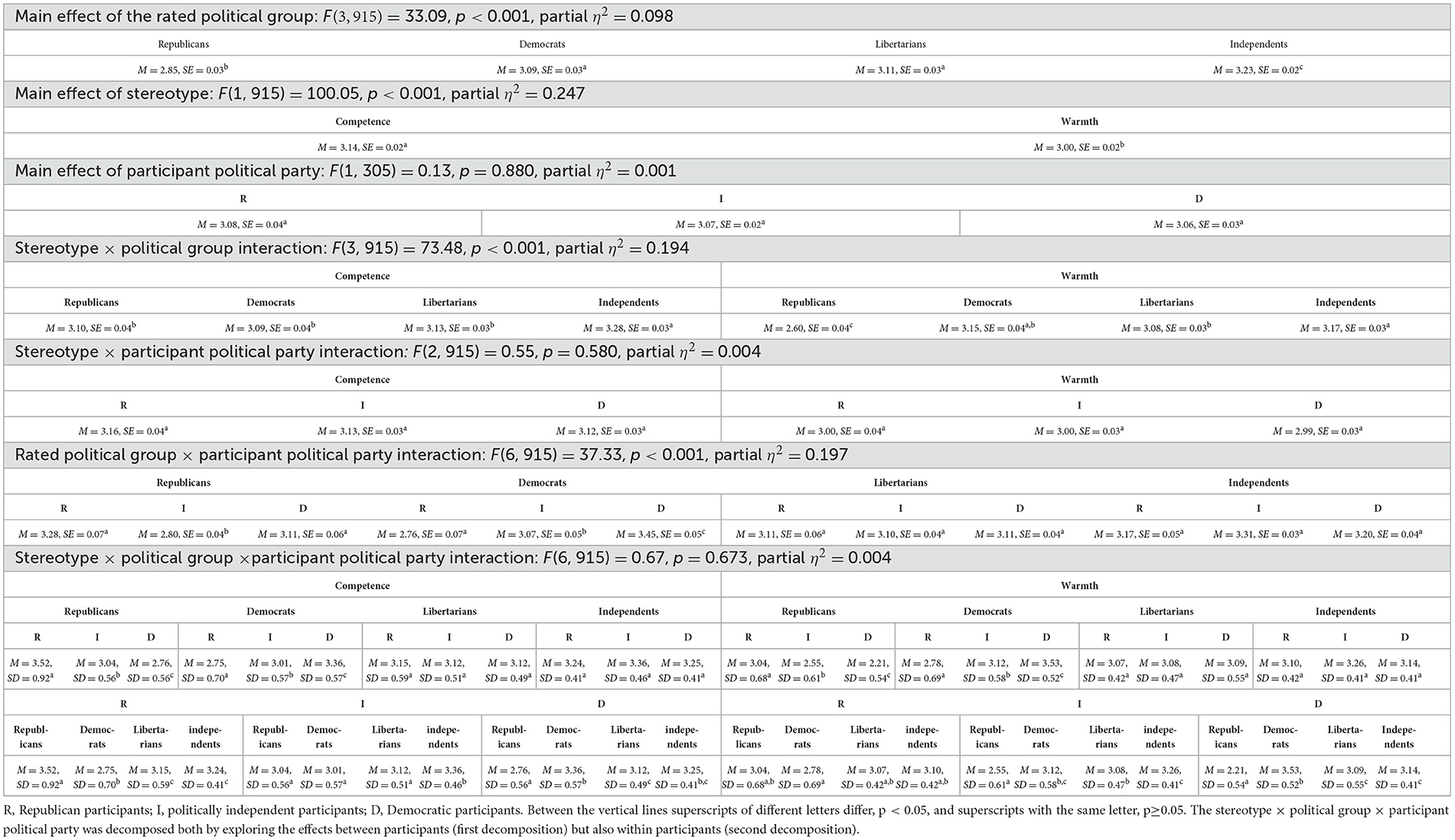

Tables 1–6 provide full results. For the analyses of variance (ANOVAs), multiple comparisons were adjusted using a Bonferroni correction.

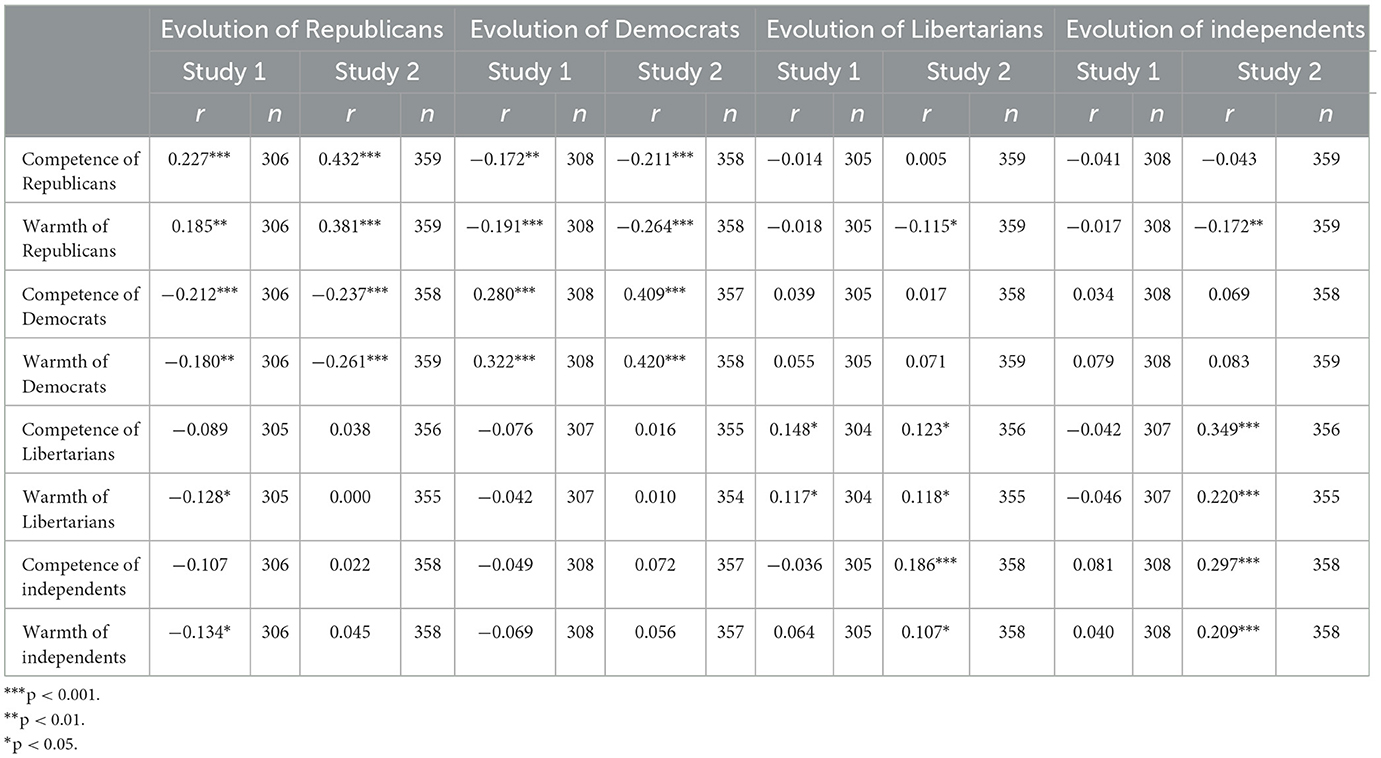

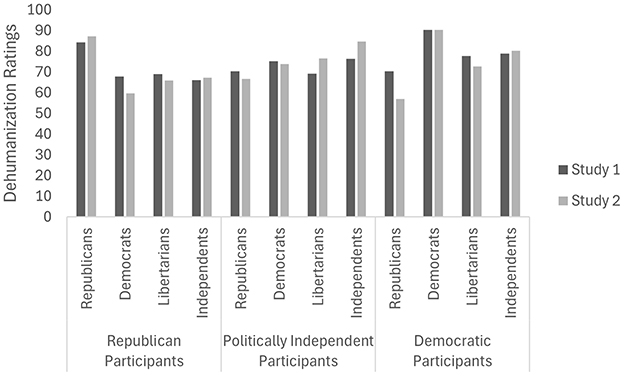

Table 6. Examining the correlations between an individual's own identified major political group and the ratings of perceived competence and warmth and dehumanization of the same and different groups.

Hypothesis 1: Political groups and fundamental stereotypes

We examined whether different patterns of fundamental stereotypes emerged for participants' perceptions of members of major political groups (Republicans, Democrats), members of a non-major political group (Libertarians), and political independents. First, we examined the competence and warmth ascribed to Republicans, Democrats, Libertarians, and independents. Because we contrasted each group's competence and warmth stereotypes, stereotype ratings were the outcome variable, meaning that competence and warmth were within-participants variables. Specifically, we used a mixed ANOVA with the political group and stereotype (competence, warmth) as within-subjects variables and participant political party identification (transformed into a categorical variable: Republican, politically independent, Democrat) as a between-subjects variable.

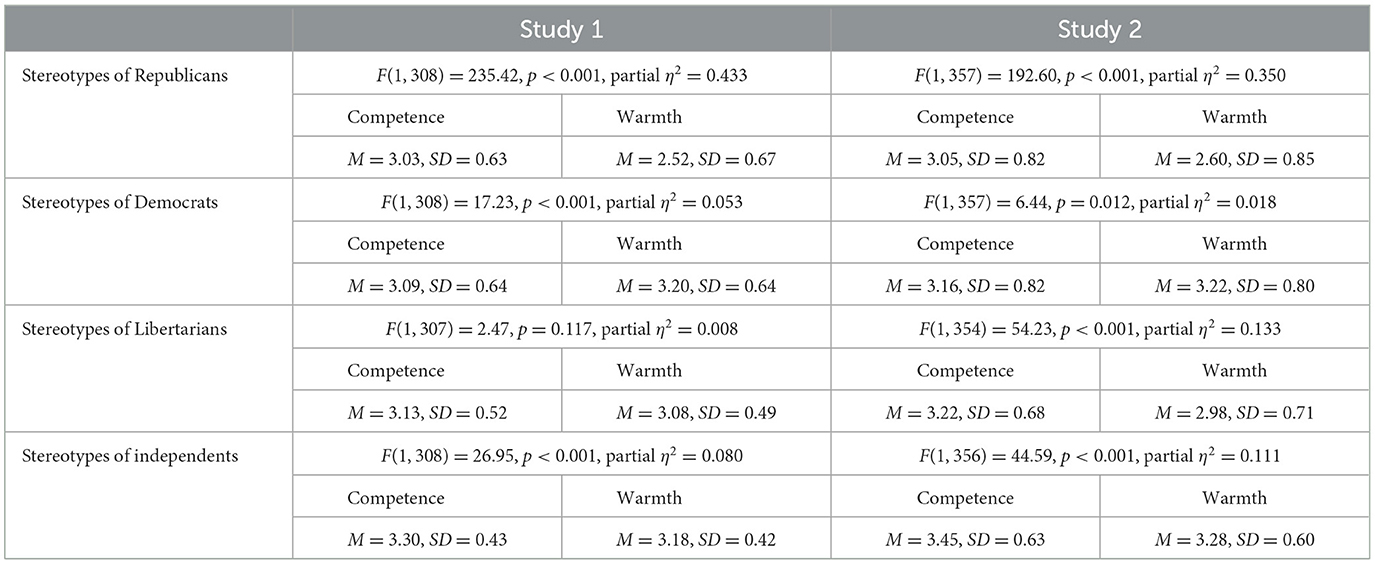

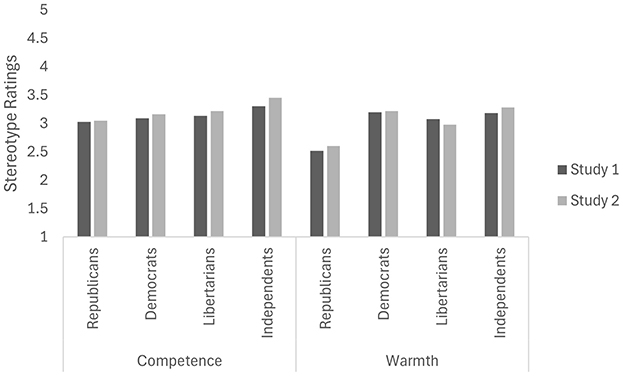

Hypothesis 1a. As predicted, a significant Political Group × Stereotype interaction emerged, ps < 0.001, partial η2s > 0.120, for competence and warmth stereotypes (see Figure 1). Participants stereotyped Republicans, Democrats (in Study 1), and Libertarians as having similar competence, ps ≥ 0.05. Independents were stereotyped as more competent than Republicans, Democrats, and Libertarians, ps < 0.001. Surprisingly, in Study 2, Democrats were stereotyped as less competent than Libertarians and independents, ps < 0.022.

Hypothesis 1b. Across Studies 1–2, participants stereotyped independents as having more warmth than Republicans and Libertarians, ps < 0.049, Democrats were stereotyped as having more warmth than Republicans, ps < 0.001, and Libertarians were stereotyped as having more warmth than Republicans, ps < 0.001. In Study 2, independents were stereotyped as having more warmth than Democrats, p = 0.008, and Democrats were stereotyped as having more warmth than Libertarians, p = 0.011 (see Figure 1).

Next, we submitted competence and warmth stereotypes of each political group to within-subjects ANOVAs. Republicans and independents were perceived as more competent than warm, ps < 0.001, but Democrats were perceived as more warm than competent, ps < 0.013. In Study 1, Libertarians were perceived as equal in competence and warmth, p = 0.117, but in Study 2, Libertarians were also perceived as more competent than warm, p < 0.001 (see Figure 1).

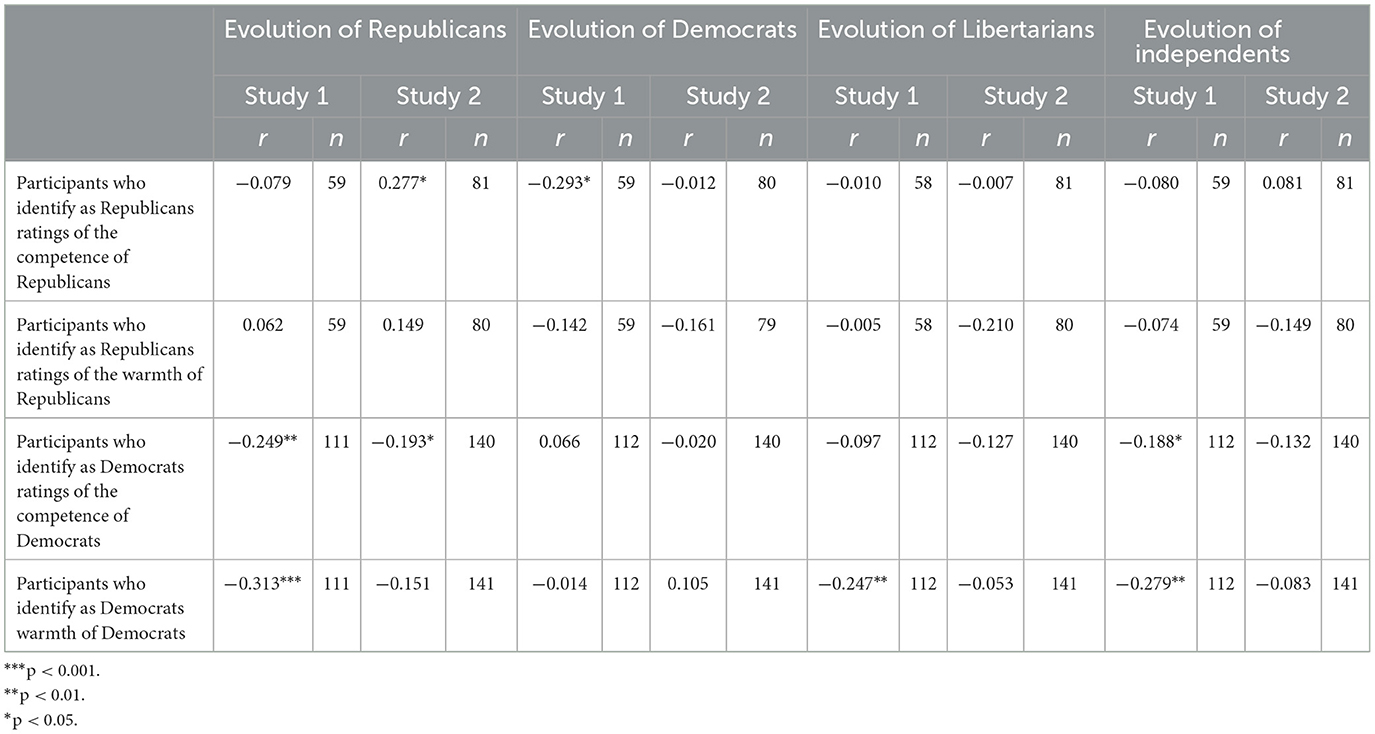

Hypothesis 1c. Consistent with our hypothesis that people identifying with a major political party would rate members of the competing major political group as lower on competence and warmth, a significant Political Group × Participant Political Party Identification interaction emerged, ps < 0.001, partial η2s > 0.196. Participants rated members of their political group as having more competence and warmth than members of competing political groups. Republicans vs. Democrats and independents rated Republicans as having more competence and warmth, ps < 0.001, and Democrats vs. Republicans and independents rated Democrats as having more competence and warmth, ps < 0.002. However, participants rated independents and Libertarians the same on competence and warmth regardless of participants' political party identification, ps > 0.069 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Examining combined warmth and competence stereotypes across groups and participant political party identification—Studies 1 and 2.

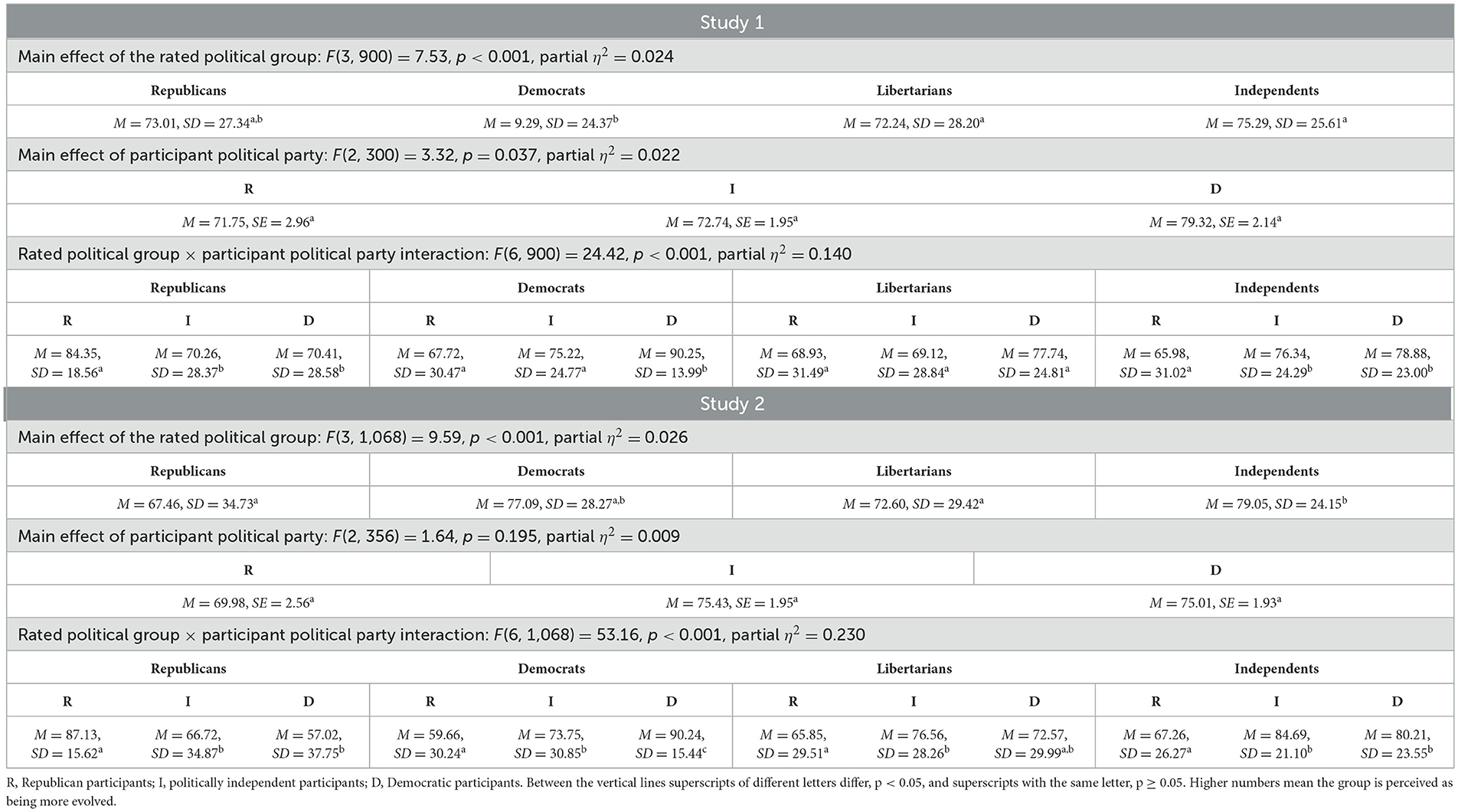

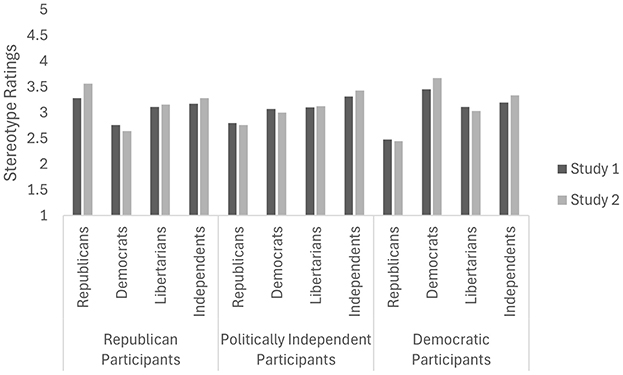

Political groups and dehumanization

We also conducted exploratory analysis to examine whether different patterns of dehumanization emerged for members of major political groups (Republicans, Democrats), members of non-major political groups (Libertarians), and political independents. We used a mixed ANOVA with political group as a within-subjects variable and participant political party identification as a between subject's variable. No consistent significant effects for ratings of political groups and participant political party emerged across both studies. However, significant Political Group × Participant Political Party Identification interactions emerged, ps < 0.001 (see Figure 3). Across both Studies, Republicans rated Republicans as more evolved than Democrats and independents did, ps < 0.006. In Study 2, independents also rated Republicans as more evolved than Democrats did, p = 0.043. Similarly, in both Studies 1 and 2, Democrats rated Democrats as more evolved than Republicans and independents did, ps < 0.001. Also, in Study 2 only, independents rated Democrats as more evolved than Republicans did, p < 0.001. Both Democrats and independents rated independents as more evolved than Republicans did, ps < 0.030. In Study 2, independents rated Libertarians as more evolved than Republicans did, p = 0.029.

Figure 3. Examining dehumanization ratings across groups and participant political party identification—Studies 1 and 2. Higher numbers mean that the group is perceived to be more evolved.

Hypothesis 2: The relationship between fundamental stereotypes and dehumanization

Hypothesis 2a. To examine whether fundamental stereotypes were associated with the dehumanization of political groups, we used correlations to examine the relationship between the competence and warmth of political groups and dehumanization. Across both studies, fundamental stereotypes of major political groups (Republicans and Democrats) were correlated with beliefs about how evolved major political groups were, ps < 0.003. Furthermore, fundamental stereotypes of major political groups were mainly unrelated to beliefs about how evolved Libertarians and independents were, ps > 0.113, except for Study 2, which found that the warmth of Republicans was associated with perceiving Libertarians and independents as less evolved, ps < 0.030. Further, in Study 1, the fundamental stereotypes of Libertarians were associated with perceptions of how evolved Libertarians were, ps < 0.042, and in Study 2, the fundamental stereotypes of Libertarians and independents were related to perceptions of how evolved Libertarians and independents were, ps < 0.005.

Hypothesis 2b. To examine whether fundamental stereotypes about an individual's own major political group were associated with the dehumanization of the other major but not Libertarians and political independents, we examined the correlations between the warmth and competence of Republicans and Democrats and the dehumanization of Republicans and Democrats and Libertarians and independents separately for participants who identified as Republicans and Democrats. Partially consistent with our hypothesis, in Study 1, when participants identified as Republican, to the extent that Republicans were perceived as competent, Democrats were perceived as less evolved, p = 0.024. However, this pattern did not emerge in Study 2 or for warmth ratings of Republicans, ps > 0.155. Consistent with our hypotheses, in Studies 1 and 2, when participants identified as Democrats, to the extent that Democrats were perceived as competent, Republicans were perceived as less evolved, ps < 0.023. Further, in Study 1, when participants identified as Democrats, to the extent that Democrats were perceived as warm, Republicans were perceived as less evolved, p < 0.001, but this pattern did not emerge in Study 2, p = 0.074. Primarily consistent with our hypothesis, fundamental stereotypes about one's own group were not related to the dehumanization of non-major political groups, ps > 0.060, except Study 1, when Democrats' ratings of the competence and warmth of Democrats were associated with the dehumanization of Libertarians and independents, ps < 0.048, and Democrats ratings of the warmth of Democrats was related to dehumanization of Libertarians, p = 0.031.

General discussion

We examined whether people view major political groups as in perceived competition and whether a non-major political group (Libertarians) and political independents offer a potential vector for social change. Our hypothesis that major political groups vs. non-major political groups and political independents would show different patterns of fundamental stereotypes was supported. Partially consistent with our hypothesis that political groups would be perceived to have equal competence, participants stereotyped Republicans, Democrats (in Study 1 only), and Libertarians as having similar competence. Still, political independents were perceived as more competent than the other groups. Further supporting our hypothesis, Republicans (conceptually replicating the political ideology results of Crawford et al., 2013) and independents were perceived as higher on competence than warmth. Democrats were perceived as higher on warmth than competence. In a sample of primarily undergraduate students, Libertarians were perceived as equal in competence and warmth (Study 1), but in an older online sample, Libertarians were perceived as higher in competence than warmth (Study 2). Further, supporting our hypothesis, Libertarians and independents were perceived as higher on competence and warmth relative to (some) major political groups (Republicans and Democrats), reflecting less perceived competition (and perhaps more admiration according to the BIAS map, Cuddy et al., 2007, 2008). Lastly, supporting major political groups as competing with one another, identification with a major political party was associated with rating the competing major political groups lower on competence and warmth.

We also conducted exploratory analyses examining whether perceptions of dehumanization of major vs. non-major political groups and political independents differed depending on participants' political identification. While participants did not differ in their perceptions of dehumanization by their political party identification, identification with a major political group was associated with dehumanizing the competing major political group. Interestingly, identification as a political independent was associated with dehumanizing Republicans, but not Democrats.

We also examined whether these fundamental stereotypes were related to dehumanization and found, consistent with our hypotheses, that fundamental stereotypes about major political groups were mostly associated with the dehumanization of major political group members but not Libertarians and independents. Partially consistent with our predictions, fundamental competence stereotypes about one's own major political group were associated with dehumanization of the other major political group, such that to the extent that Democrats perceived Democrats to be competent, Republicans were rated as being less evolved (Studies 1–2). To the extent that Republicans perceived Republicans as competent, Democrats were perceived to be less evolved (Study 1 only).

Implications, limitations, and future directions

Because Libertarians and political independents were less likely to be perceived as in competition with major political parties, non-major political groups and political independents provide an avenue for moving beyond the current polarization among elites and the masses. For instance, since elite and mass polarization is associated with a host of policy (Binder, 2004; Esposo et al., 2013; Jones, 2001), civility (Jamieson and Falk, 2000; Layman et al., 2006), and evaluative consequences (Enders and Armaly, 2019), the increased representation of non-major political parties and politically independent elected officials should slow the legislative gridlock and policy inaction while also increasing civility of political speech. Further, suppose these non-major political groups and politically independent elected officials propose “right” policies. These policies should be more likely to be considered by all, possibly because the non-major political groups and political independents and their respective groups will be associated with more favorable evaluations than major political groups and their members. Future research should examine whether the presence of non-major political group and political independent elected representatives helps alleviate some of the consequences of political polarization.

The findings of perceived competition between major political groups reflected in the stereotypes ascribed to major political groups paint a troubling picture for moving beyond polarization. However, the similarities in competence across Republicans, Democrats, Libertarians, and political independents offer a way to address polarized stereotypes of major political groups. Political polarization should decrease by highlighting commonalities between political groups, reducing animosity, and increasing reported closeness (Syropoulos and Leidner, 2023) between the other major political groups, non-major political groups, and political independents. Future research should examine whether highlighting the common competence stereotypes of political groups for voters and policymakers increases closeness, humanity, acceptance of, and support for political groups and politicians different from one's own political group. When groups are perceived as low on competence or warmth, they are perceived as less evolved (Boysen et al., 2023; Harris and Fiske, 2006; Kuljian and Hohman, 2022; Vaes and Paladino, 2009).

Competence ratings of one's own major political group were associated with dehumanizing the other major political group. While we assume that our findings reflect perceived competition between major political groups but not non-major political groups or political independents, we did not directly measure perceptions of competition and perceived competitive threat associated with each of the political groups we assessed. It is possible that the findings might not represent a perceived competitive threat but instead reflect more basic intergroup categorization processes that facilitate perceived competition. Future research should examine whether perceptions of competition and perceived competitive threat mediate our effects. Further, future research should also examine whether perceiving the other major political group as competition is due to meta-dehumanization, which is the perception that another group perceives one's own group as less human (Kteily et al., 2016). If this is the case, then providing participants with information about how political partisans overestimate how much other groups dehumanize them before participants rate stereotypes and dehumanization should decrease dehumanization and increase prosocial behaviors (Landry et al., 2023). Future work should also examine how competence stereotypes and perceptions of humanness are related to hostility (Kteily et al., 2016; Landry et al., 2022) and the desire to skirt the law to gain political power (Landry et al., 2022).

The findings for Libertarians and independents offer a promising direction as groups that are high in both competence and warmth are typically considered to be one's own group or reference group and receive admiration, help, and people want to associate with them (Cuddy et al., 2007, 2008). Although non-major political groups and political independents are not currently reference groups within the U.S. political system, based on the stereotypes associated with them, they are well-positioned to gain reference group status and further increase their following. Future research should examine how political group stereotypes translate to motivation to engage with and vote for office in a broader assortment of non-major political groups and politically independent candidates.

It is possible that participants could have been confused about non-major political groups and political independents, which might impact their ratings. Voter registration forms often list no party affiliation and minor party under party affiliation, and it is common to refer to individuals with no party affiliation as independents. Thus, participants might mistake political independents as a political party. Additionally, participants likely were less familiar with non-major political groups and political independents than major political parties. Because individuals' beliefs about others, especially those who are relatively unknown, is based on their own knowledge (Kruger and Clement, 1994), when asked to evaluate a non-major political group and political independents, participants might have projected their own political values and beliefs onto the group they were evaluating. Future research should examine the role that familiarity and political knowledge plays in our effects.

While we argue that increased support for non-major political groups and political independents might be one way to move beyond polarization, it should be noted that if a non-major political group or more politically independent individuals gain power, the U.S. might only move to a multiple-party system for a short while. According to Duverger's Law, when a political system uses a simple majority single-ballot approach to elections, the two-party system prevails in part because party elites and the voting public perceive voting for non-major party individuals as “wasted votes” (Duverger, 1959). However, this is not always the case if the broader context supports a third party (Benoit, 2006). For instance, strong local parties in countries such as Canada and India have a simple majority single-ballot approach to elections that supports more than two parties (Rae, 1971). Thus, if political group stereotypes translate to increased motivation to engage with and vote for non-major political groups and political independents, future research should examine what situational supports would be critical for the political system to support more than two political parties over time.

Since the fundamental stereotypes ascribed to the Libertarians varied depending on the sample [undergraduate students (Study 1) vs. an older online sample (Study 2)], these stereotypes might be malleable to shifts in the social environment (Eagly et al., 2020), including sociopolitical threats (Brown et al., 2011), structural changes from evolving social roles (Haines et al., 2016), and increased exposure to new information (e.g., Dasgupta and Asgari, 2004). For instance, when countries are facing crises, people are more likely to vote for a different political party (Erikson et al., 2002) to address the crisis. Since crises are often associated with anxiety, when voters are experiencing anxiety about political candidates, they are more likely to seek out new information about political candidates (MacKuen et al., 2007; Marcus et al., 2000). Thus, during times of crisis, voters might be open to seeking new information about new non-major political groups and their respective candidates or politically independent candidates to address the crisis.

Participants in the current studies were significantly younger than the median age of the average voter in the United States (50 years old; Gramlich, 2020). Future research should explore whether older, more diverse participants have similar stereotype content and perceptions about how human Republicans, Democrats, Libertarians (and other non-major political groups), and independents are. Among older participants, stereotypes about major political groups and perceptions of the humanity of these groups might be more robust because they have had more exposure to these stereotypes throughout their lives. However, stereotype content for non-major political groups and political independents might be more variable because, until 2011, most voters in the United States identified as either Republicans or Democrats (Jones, 2022). Thus, older participants might be more dedicated to major political groups.

Across both studies, participants not only indicated “as viewed by society how (competence item/warmth item) are Republicans/Democrats/Libertarians/independents,” but also indicated how evolved the average member of each group was. By asking participants to rate their perceptions of these groups in terms of how they perceive that society views them or in terms of the average member, it is unclear whether they were thinking of party elites, individuals who vote for these groups, individuals who identify with these groups, and/or politically engaged citizens. Stereotypical ratings are likely to include all these individuals. Future research should examine whether the patterns of results differ depending on whether participants are asked to rate specific subgroups of individuals. Consistent with the literature on elite partisanship (i.e., Enders, 2021), rating political elites vs. individuals who vote for these groups might elicit more pronounced warmth stereotypes, competence stereotypes, and dehumanization.

Lastly, the current study uses a correlational design to examine the relationship between competence and warmth stereotypes of Republicans, Democrats, Libertarians, and independents and dehumanization. While we argue that stereotypes are associated with dehumanization, causality cannot be determined. Future research should examine whether the activation of competence and warmth stereotypes associated with Republicans, Democrats, Libertarians, and political independents results in dehumanization or whether the activation of dehumanization of Republicans, Democrats, Libertarians, and political independents shifts the competence and warmth stereotypes associated with these groups.

Conclusion

Across two studies (a sample of undergraduates and a sample of older adults), the fundamental stereotypes associated with major (Republicans and Democrats), but not a non-major political group (Libertarians) and political independents, were perceived to compete. Libertarians and political independents offer the possibility of creating social change because the fundamental stereotypes associated with them were more consistent with those ascribed to admired groups. When individuals identified with a major political party, to the extent that they saw their political group as competent, they were more likely to dehumanize the other major political group. However, stereotypes of major political groups were, by and large, not associated with the dehumanization of Libertarians and political independents. Our findings support the perceived non-competitive nature of Libertarians and political independents and provide hope that they can help move the political system beyond polarization and its consequences.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article along with analysis code can be found on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/ge9rb/?view_only=e95244fea72b4e46a0fa2e424c471281).

Ethics statement

The studies were approved by Institutional Review Board at the University of North Florida. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

EB: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CP: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CV-M: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the D.R.E.A.M. Lab for helping with data collection and manuscript feedback. We would also like to thank the Faculty Writing Group at the University of North Florida for providing support and encouragement throughout the analysis and writing process. We would also like to thank the College of Arts and Sciences' Summer Undergraduate Research Fellow Professional Development Funding donated by Mr. Jim Van Vleck to the University of North Florida and provided to the first author for their financial support that partially paid for the publication fees associated with this manuscript. We would also like to thank the faculty start-up provided by the University of Oregon to the second author for their financial support that partially paid for the publication fees associated with this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Others indicate that mass polarization is not increasing (see Fiorina et al., 2006).

2. ^In Study 1, participants were not asked whether they had voted in the most recent election.

References

Abramowitz, A. I., and Saunders, K. L. (2006). Exploring the bases of partisanship in the American electorate: social identity versus ideology. Polit. Res. Q. 59, 175–187. doi: 10.1177/106591290605900201

Abramowitz, A. I., and Saunders, K. L. (2008). Is polarization a myth? J. Polit. 70, 542–555. doi: 30218906 doi: 10.1017/S0022381608080493

Andrighetto, L., Baldissarri, C., Lattanzio, S., Loughnan, S., and Volpato, C. (2014). Human-itarian aid? Two forms of dehumanization and willingness to help after natural disasters. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 53, 573–584. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12066

Bain, P., Park, J., Kwok, C., and Haslam, N. (2009). Attributing human uniqueness and human nature to cultural groups: distinct forms of subtle dehumanization. Group Process. Intergr. Relat. 12, 789–805. doi: 10.1177/1368430209340415

Benoit, K. (2006). Duverger's law and the study of electoral systems. French Politics 4, 69–83. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.fp.8200092

Binder, S. A. (2004). Stalemate: Causes and Consequences of Legislative Gridlock. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Boysen, G. A., Tchaikovsky, R. L., and Delmore, E. E. (2023). Dehumanization of mental illness and the stereotype content model. Stigma Health 8, 150–158. doi: 10.1037/sah0000256

Brady, H. E., and Sniderman, P. M. (1985). Attitude attribution: a group basis for political reasoning. Am. J. Polit. Sci. Rev. 79, 1061–1078. doi: 10.2307/1956248

Brown, E. R., Diekman, A. B., and Schneider, M. C. (2011). A change will do us good: threats diminish typical preferences for male leaders. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 37, 930–941. doi: 10.1177/0146167211403322

Canen, N. J., Kendall, C., and Trebbi, F. (2021). Political parties as drivers of us polarization: 1927-2018 (No. w28296). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3803669

Capozza, D., Di Bernardo, G. A., and Falvo, R. (2017). Intergroup contact and outgroup humanization: is the causal relationship uni- or bidirectional? PLoS ONE, 12, e0170554. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170554

Clifford, S. (2020). Compassionate Democrats and tough Republicans: how ideology shapes partisan stereotypes. Polit. Behav. 42, 1269–1293. doi: 10.1007/s11109-019-09542-z

Cohen, G. L. (2003). Party over policy: the dominating impact of group influence on political beliefs. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 85, 808–822. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.5.808

Crawford, J. T., Modri, S. A., and Motyl, M. (2013). Bleeding-heart liberals and hard-hearted conservatives: Subtle political dehumanization through differential attributions of human nature and human uniqueness traits. J. Soc. Polit. Psychol. 1, 86–104. doi: 10.5964/jspp.v1i1.184

Cuddy, A. J. C., Fiske, S. T., and Glick, P. (2007). The BIAS map: behaviors from intergroup affect and stereotypes. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 92, 631–648. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.4.631

Cuddy, A. J. C., Fiske, S. T., and Glick, P. (2008). Warmth and competence as universal dimensions of social perceptions: the stereotype content model and the BIAS map. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 40, 61–149. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(07)00002-0

Dalton, R. (2021). The representation gap and political sophistication: a contrarian perspective. Comp. Polit. Stud. 54, 889–917. doi: 10.1177/0010414020957673

Dasgupta, N., and Asgari, S. (2004). Seeing is believing: exposure to counterstereotypic women leaders and its effect on malleability of automatic gender stereotyping. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 40, 642–658. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2004.02.003

Devine, P. G. (1989). Stereotypes and prejudice: their automatic and controlled components. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 56, 5–18. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.56.1.5

Duverger, M. (1959). Political Parties: Their Organization and Activity in the Modern State. Second English Revised edn. London: Methuen and Co.

Eagly, A. H., Nater, C., Miller, D. I., Kaufmann, M., and Sczesny, S. (2020). Gender stereotypes have changed: a cross-temporal meta-analysis of U.S. public opinion polls from 1946-2018. Am. Psychol. 75, 301–315. doi: 10.1037/amp0000494

Eagly, A. H., Wood, W., and Diekman, A. B. (2000). “Social role theory of sex differences and similarities: a current appraisal,” in The Developmental Social Psychology of Gender, eds. T. Eckes, and H. M. Trautner (Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum), 123–174.

Enders, A. M. (2021). Issues versus affect: how do elite and mass polarization compare? J. Polit. 83, 1872–1877. doi: 10.1086/715059

Enders, A. M., and Armaly, M. T. (2019). The differential effects of actual and perceived polarization. Polit. Behav. 41, 815–839. doi: 10.1007/s11109-018-9476-2

Erikson, R. S., Mackuen, M. B., and Stimson, J. A. (2002). The Macro Polity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139086912

Esposo, S. R., Hornsey, M. J., and Spoor, J. R. (2013). Shooting the messenger: outsiders critical of your group are rejected regardless of argument quality. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 52, 386–395. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12024

Fielding, K. S., and Hornsey, M. J. (2016). A social identity analysis of climate change and environmental attitudes and behaviors: insights and opportunities. Front. Psychol. 7:121. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00121

Fiorina, M. P., Abrams, S. J., and Pope, J. C. (2006). Culture War? The Myth of a Polarized America, 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Pearson Longman.

Fiske, S., Cuddy, A., Glick, P., and Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 82, 878–902. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.878

Gift, K., and Gift, T. (2015). Does politics influence hiring? Evidence from a randomized experiment. Polit. Behav. 37, 653–675. doi: 10.1007/s11109-014-9286-0

Gimpel, J. G., and Hui, I. S. (2015). Seeking politically compatible neighbors? The role of neighborhood partisan composition in residential sorting. Polit. Geogr. 48, 130–142. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2014.11.003

Goggin, S. N., Henderson, J. A., and an Theodoridis, A. G. (2020). What goes with red and blue? Mapping partisan and ideological associations in the minds of voters. Polit. Behav. 42, 985–1013. doi: 10.1007/s11109-018-09525-6

Goggin, S. N., and Theodoridis, A. G. (2017). Disputed ownership: parties, issues, and traits in the minds of voters. Polit. Behav. 39, 675–702. doi: 10.1007/s11109-016-9375-3

Gramlich, J. (2020). What the 2020 electorate looks like by party, race and ethnicity, age, education and religion. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2020/10/26/what-the-2020-electorate-looks-like-by-party-race-and-ethnicity-age-education-and-religion/ (accessed January 22, 2024).

Greene, S. (1999). Understanding party identification: a social identity approach. Polit. Psychol. 20, 393–403. doi: 10.1111/0162-895X.00150

Haines, E. L., Deaux, K., and Lofaro, N. (2016). The times they are changing… or are they not? A comparison of gender stereotypes, 1983-2014. Psychol. Women Q. 40, 353–363. doi: 10.1177/0361684316634081

Harris, L. T., and Fiske, S. T. (2006). Dehumanizing the lowest of the low: neuroimaging responses to extreme out-groups. Psychol. Sci. 17, 847–853. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01793.x

Haslam, N., Loughnan, S., Kashima, Y., and Bain, P. (2008). Attributing and denying humanness to others. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 19, 55–85. doi: 10.1080/10463280801981645

Hersh, E. (2016). What the Yankees-Red Sox rivalry can teach us about political polarization. FiveThirtyEight. Available online at: https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/what-the-yankees-red-sox-rivalry-can-teach-us-about-political-polarization/ (accessed September 22, 2023).

Hornsey, M. J., and Imani, A. (2004). Criticizing groups from the inside and the outside: an identity perspective on the intergroup sensitivity effect. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 30, 365–383. doi: 10.1177/0146167203261295

Huddy, L., Mason, L., and Aarøe, L. (2015). Expressive partisanship: Campaign involvement, political emotion, and partisan identity. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 109, 1–17. doi: 10.1017/S0003055414000604

Hughes, T., and Carlson, D. (2015). Divided government and delay in the legislative process: evidence from important bills, 1949-2010. Am. Polit. Res. 43, 771–792. doi: 10.1177/1532673X15574594

Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N., and Westwood, S. J. (2019). The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 22, 129–146. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-051117-073034

Jamieson, K. H., and Falk, E. (2000). “Continuity and change in civility in the house,” in Polarized Politics: Congress and the President in a Partisan Era, eds. J. R. Bond, and R. Fleisher (Washington, DC: CQ Press), 96–108.

Jones, D. R. (2001). Party polarization and legislative gridlock. Polit. Res. Q. 54, 125–141. doi: 10.1177/106591290105400107

Jones, J. M. (2022). U.S. Political Party Preferences Shifted Greatly During 2021. Gallup. Retrieved from: https://news.gallup.com/poll/388781/political-party-preferences-shifted-greatly-during-2021.aspx (accessed January 22, 2024).

Kelman, H. C. (1973). Violence without moral restraint: reflection of the dehumanization of victims of violence. J. Soc. Issues 29, 48–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1973.tb00102.x

Kervyn, N., Yzerbyt, V. Y., Demoulin, S., and Judd, C. M. (2008). Competence and warmth in context: the compensatory nature of stereotypic views of national groups. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 38, 1175–1183. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.526

Kruger, J., and Clement, R. W. (1994). The truly false consensus effect: an ineradicable and ecocentric bias in social perceptions. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 67, 596–610. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.67.4.596

Kteily, N., Bruneau, E., Waytz, A., and Cotterill, S. (2015). The ascent of man: theoretical and empirical evidence for blatant dehumanization. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 109, 901–931. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000048

Kteily, N., Hodson, G., and Bruneau, E. (2016). They see us as less than human: metadehumanization predicts intergroup conflict via reciprocal dehumanization. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 110, 343–370. doi: 10.1037/pspa0000044

Kteily, N. S., and Bruneau, E. (2017). Darker demons of our nature: the need to (re)focus attention on blatant forms of dehumanization. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 26, 487–494. doi: 10.1177/0963721417708230

Kuljian, O. R., and Hohman, Z. P. (2022). Warmth, competence, and subtle dehumanization: Comparing clustering patterns of warmth and competence with animalistic and mechanistic dehumanization. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 62, 181–196. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12565

Laloggia, J. (2019). 6 facts about U.S. political independents. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2019/05/15/facts-about-us-political-independents/ (accessed January 22, 2024).

Landry, A. P., Ihm, E., and Schooler, J. W. (2022). Hated but still human: metadehumanization leads to greater hostility than metaprejudice. Group Process. Intergr. Relat. 25, 315–334. doi: 10.1177/1368430220979035

Landry, A. P., Schooler, J. W., Willer, R., and Seli, P. (2023). Reducing explicit blatant dehumanization by correcting exaggerated meta-perceptions. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 14, 407–418. doi: 10.1177/19485506221099146

Layman, G. C., Carsey, T. M., and Horowitz, J. M. (2006). Party polarization in American politics: characteristics, causes, and consequences. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 9, 83–110. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.9.070204.105138

MacKuen, M., Marcus, G. E., Neuman, W. R., and Keele, L. (2007). “The third way: the theory of affective intelligence and American democracy,” in The Affect Effect: Dynamics of Emotion in Political Thinking and Behavior, eds. G. E. Marcus, W. R. Neuman, and M. MacKuen (Oxford: Oxford Academic), 124–151. doi: 10.7208/chicago/9780226574431.003.0006

Macrae, C. N., Bodenhausen, G. V., Milne, A. B., Thorn, T. M. J., and Castelli, L. (1997). On the activation of social stereotypes: the moderating role of processing objectives. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 33, 471–489. doi: 10.1006/jesp.1997.1328

Marcus, G. E., Neuman, W. R., and Mackuen, M. B. (2000). Affective Intelligence and Political Judgment. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

McCarty, N. M., Poole, K. T., and Rosenthal, H. (2006). Polarized America: The Dance of Ideology and Unequal Riches. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

McConnell, C., Margalit, Y., Malhotra, N., and Levendusky, M. (2018). The economic consequences on partisanship in a polarized era. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 62, 5–18. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12330

Michelitch, K. (2015). Does electoral competition exacerbate interethnic or interpartisan economic discrimination? Evidence from a field experiment in market price bargaining. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 109, 43–61. doi: 10.1017/S0003055414000628

Nicolas, G., Bai, X., and Fiske, S. T. (2022). A spontaneous stereotype content model: taxonomy, properties, and prediction. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 123, 1243–1263. doi: 10.1037/pspa0000312

Petrocik (1996). Issue ownership in presidential elections, with a 1980 case study. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 40, 825–850. doi: 10.2307/2111797

Prati, F., Vasiljevic, M., Crisp, R. J., and Rubini, M. (2015). Some extended psychological benefits of challenging social stereotypes: decreased dehumanization and a reduced reliance on heuristic thinking. Group Process. Intergr. Relat. 18, 801–816. doi: 10.1177/1368430214567762

Rae, D. W. (1971). The Political Consequences of Electoral Laws, Rev edn. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Rothschild, J. E., Howat, A. J., Shafranek, R. M., and Busby, E. C. (2019). Pigeonholing partisans: Stereotypes of party supporters and partisan polarization. Polit. Behav. 41, 423–443. doi: 10.1007/s11109-018-9457-5

Schneider, M. C., and Bos, A. L. (2019). The application of social role theory to the study of gender in politics. Polit. Psychol. 40, 173–213. doi: 10.1111/pops.12573

Sherman, J. W., Stroessner, S. J., Conrey, F. R., and Azam, O. A. (2005). Prejudice and stereotype maintenance processes: attention, attribution, and individuation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 89, 607–622. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.4.607

Shor, B., and McCarty, N. (2022). Two decades of polarization in American state legislatures. J. Polit. Inst. Polit. Econ. 3, 343–370. doi: 10.1561/113.00000063

Sørensen, E. (2014). “The metagovernance of public innovation in governance networks,” in Policy and Politics Conference in Bristol (Bristol), 16–17.

Struch, N., and Schwartz, S. H. (1989). Intergroup aggression: its predictors and distinctness from in-group bias. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 56, 364–373. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.56.3.364

Syropoulos, S., and Leidner, B. (2023). Emphasizing similarities between politically opposed groups and their influence in perceptions of the political opposition: Evidence from five experiments. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 51, 530–553. doi: 10.1177/01461672231192384

Theodoridis, A. G. (2017). Me, myself, and (I), (D), or (R)? Partisanship and political cognition through the lens of implicit identity. J. Polit. 79, 1468–2508. doi: 10.1086/692738

Transue, J. E. (2007). Identity salience, identity acceptance, and racial policy attitudes: american national identity as a uniting force. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 51, 78–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00238.x

Twenge, J. M., Honeycutt, N., Prislin, R., and Sherman, R. A. (2016). More polarized but more independent: political party identification and ideological self-categorization among U.S. adults, college students, and late adolescents, 1970-2015. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 42, 1364–1383. doi: 10.1177/0146167216660058

Unsworth, K. L., and Fielding, K. S. (2014). It's political: How the salience of one's political identity changes climate change beliefs and policy support. Glob. Environ. Change 27, 131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.05.002

Vaes, J., and Paladino, M. P. (2009). The uniquely human content of stereotypes. Group Process. Intergr. Relat. 13, 23–39. doi: 10.1177/1368430209347331

Keywords: stereotypes, competence, warmth, political groups, dehumanization

Citation: Brown ER, Phills CE and Veilleux-Mesa CJ (2025) Of donkeys, elephants, and dehumanization: exploring the content and implications of stereotypes of Republicans, Democrats, Libertarians, and independents. Front. Soc. Psychol. 3:1376013. doi: 10.3389/frsps.2025.1376013

Received: 24 January 2024; Accepted: 14 February 2025;

Published: 12 March 2025.

Edited by:

Richard P. Eibach, University of Waterloo, CanadaReviewed by:

Matthew Hibbing, University of California, Merced, United StatesDavid Morris Perlman, Stanford University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Brown, Phills and Veilleux-Mesa. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Elizabeth R. Brown, ZWxpemFiZXRoLnIuYnJvd25AdW5mLmVkdQ==

Elizabeth R. Brown

Elizabeth R. Brown Curtis E. Phills

Curtis E. Phills Candice J. Veilleux-Mesa

Candice J. Veilleux-Mesa