94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Soc. Psychol., 28 January 2025

Sec. Attitudes, Social Justice and Political Psychology

Volume 2 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frsps.2024.1497434

This article is part of the Research TopicSocial and Political Psychological Perspectives on Global Threats to DemocracyView all 8 articles

Danit Finkelstein1

Danit Finkelstein1 Sonia Yanovsky1

Sonia Yanovsky1 Jacob Zucker2

Jacob Zucker2 Anisha Jagdeep2

Anisha Jagdeep2 Collin Vasko2

Collin Vasko2 Ankita Jagdeep2

Ankita Jagdeep2 Lee Jussim1*

Lee Jussim1* Joel Finkelstein2

Joel Finkelstein2Three studies explored how TikTok, a China-owned social media platform, may be manipulated to conceal content critical of China while amplifying narratives that align with Chinese Communist Party objectives. Study I employed a user journey methodology, wherein newly created accounts on TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube were used to assess the nature and prevalence of content related to sensitive Chinese Communist Party (CCP) issues, specifically Tibet, Tiananmen Square, Uyghur rights, and Xinjiang. The results revealed that content critical of China was made far less available than it was on Instagram and YouTube. Study II, an extension of Study I, investigated whether the prevalence of content that is pro- and anti-CCP on TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube aligned with user engagement metrics (likes and comments), which social media platforms typically use to amplify content. The results revealed a disproportionately high ratio of pro-CCP to anti-CCP content on TikTok, despite users engaging significantly more with anti-CCP content, suggesting propagandistic manipulation. Study III involved a survey administered to 1,214 Americans that assessed their time spent on social media platforms and their perceptions of China. Results indicated that TikTok users, particularly heavy users, exhibited significantly more positive attitudes toward China's human rights record and expressed greater favorability toward China as a travel destination. These results are discussed in context of a growing body of literature identifying a massive CCP propaganda bureaucracy devoted to controlling the flow of information in ways that threaten free speech and free inquiry.

In today's digital landscape, the manipulation of information on social media platforms has emerged as a powerful tool for shaping global narratives, with authoritarian regimes like Russia, Iran, the Islamic State (ISIS), and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) increasingly exploiting these channels to advance their strategic interests (Bradshaw and Howard, 2019; Elswah and Howard, 2020; Freedom House, 2023; King et al., 2017; Michaelsen, 2018; Woolley and Howard, 2018). Russia, for example, has been particularly aggressive at using disinformation through social media to advance its geopolitical goals, like interfering in the U.S. 2016 presidential election and weakening alliances such as NATO and the European Union (Mejias and Vokuev, 2017). China has developed sophisticated strategies to control narratives, influence public opinion, and maintain political control (Tsai, 2021). Likewise, across the Arab world, authoritarian regimes have responded to online dissent by monitoring and controlling digital discourse, leading to the arrest and imprisonment of bloggers, activists, and social media users, a trend that was particularly prominent during the Arab Spring (Kraidy, 2017; York, 2010). This growing trend raises critical concerns about the implications for international relations, democratic processes, and global security in the digital age (Benkler et al., 2018).

Authoritarianism, defined by centralized control and suppression of dissent, whether of the political right (e.g., Altemeyer, 1981, 1996; Yourman, 1939) or left (e.g., Costello et al., 2022; Dikötter, 2016), has long relied on propaganda as a key instrument of power. In the modern digital era, this propaganda has evolved into a more covert and pervasive form of influence referred to as “networked authoritarianism” (e.g., Maréchal, 2017). State actors, through algorithmic manipulation and strategic content curation, subtly shape narratives on popular social media platforms (Gunitsky, 2015). Unlike traditional forms of propaganda, these digital tactics are often invisible to users, making them particularly effective in altering public perception and behavior without overt detection (Bradshaw and Howard, 2019).

Propaganda on social media can promote an “informational autocracy” (Krekó, 2022) by controlling the flow of information in such a manner as to maintain false impressions of the competence, honesty, and effectiveness of an authoritarian regime, and to suppress dissenting voices and obscure narratives that challenge the status quo (Guriev and Treisman, 2020; Kalathil, 2020; Maréchal, 2017). For example, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) systematically fabricates social media content to distract and divert public attention from sensitive issues (King et al., 2017). By influencing the information flow on these platforms, the CCP can reshape narratives, alter global perceptions, and reinforce its strategic objectives (King et al., 2017), whether these involve curbing dissent, promoting nationalism, or maintaining domestic stability. According to previous work by the French Armed Forces' Institute for Strategic Research (IRSEM), the CCP's operations in the information environment1 strive to achieve two primary objectives: (1) “seduce and subjugate foreign audiences by painting China in a positive light,” and (2) “infiltrate and constrain—a ‘harsher' category of operations that do not involve seducing its opponents but rather bending them” (Charon and Jeangène Vilmer, 2021, p. 413).

The threat posed by authoritarian foreign interference through operations in the information environment is increasingly recognized as a significant challenge to modern democracies (Benkler et al., 2018; Office of the Director of National Intelligence, 2021; Rosenbach and Mansted, 2018; United States Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, 2019). By infiltrating and manipulating social media platforms, authoritarian regimes can engage in propaganda operations that alter the attitudes and beliefs of foreign populations, often without their knowledge (Tufekci, 2017). These operations exploit the open nature of democratic societies (Woolley and Howard, 2018). Interference such as this can undermine public trust in media, weaken democratic institutions, and sow division within societies, all in service of expanding authoritarian influence (Benkler et al., 2018).

Herman and Chomsky's (1988) Manufacturing Consent posits that media systems in liberal democracies, while ostensibly free, often serve as instruments for elite-driven propaganda. While originally applied to traditional media, their “propaganda model” offers a prescient lens through which to understand TikTok's role in possibly shaping perceptions of China among American users. Herman and Chomsky (1988) argued that media, operating under elite control, often serve to propagate narratives aligned with dominant political and economic interests. This model describes how mechanisms such as ownership, advertising reliance, and sourcing biases filter content to support state or corporate objectives.

TikTok, a platform owned by the Chinese company ByteDance, may function as a digital analog of the ideological machinery described in Manufacturing Consent. With 1 billion active users worldwide, TikTok holds a vast audience (Backlinko, 2024). Its sheer scale and reach make it a formidable vehicle for shaping public perception. By amplifying content that is favorable to the CCP and suppressing narratives critical of the CCP, TikTok can influence international discourse in ways that align with the CCP's strategic interests. This platform's ability to subtly curate content echoes the “invisible” manipulation mechanisms emphasized by Herman and Chomsky (1988), wherein propaganda is delivered not through overt censorship but by determining what content is readily accessible to users.

Amplifying narratives favorable to CCP interests, or suppressing narratives that threaten CCP interests, stems from its broader goal of maintaining authoritarian political control domestically while cultivating a positive image internationally to advance its geopolitical objectives. In December 2023, the Network Contagion Research Institute (NCRI) published research that compared the number of hashtags between TikTok and Instagram for terms that are sensitive issues domestically and externally for the CCP. Although the study was preliminary, it found that the number of hashtags of CCP-critical topics on TikTok was substantially lower than the number of the same hashtags on Instagram, concluding that there exists “a strong possibility that TikTok systematically promotes or demotes content on the basis of whether it is aligned with or opposed to the interests of the Chinese Government” (NCRI, 2023).

In this study we classified content into anti- or pro-CCP, which is a mere shorthand for more nuanced categories, which we describe here. Content that the CCP seeks to suppress—such as human rights abuses and political dissent—was coded as anti-CCP. Content that the CCP seeks to amplify—such as promotion of tourism by government-owned companies, idyllic portrayals of rural life, etc.—was coded as pro-CCP. Throughout the rest of this paper, we refer to content that is unfavorable to CCP interests or critical of the Chinese government as “anti-CCP,” and content that is supportive of the Chinese government or favorable to CCP interests as “pro-CCP.”

The current research builds on the foundation laid by King et al. (2017), IRSEM (Charon and Jeangène Vilmer, 2021), and NCRI (2023) to explore the broader implications of these operations in the information environment by examining the nature and prevalence of CCP-sensitive content on TikTok, and evaluating how different platforms handle such content. Specifically, this research examines whether there is evidence that TikTok and other social media platforms are being used to advance the CCP's propaganda objectives.

Although it may be easier for the Chinese government to manipulate information on a Chinese-owned social media company, manipulation of the content of other social media companies is also possible. One form of such manipulation is to create puppet accounts to promote propaganda and preferred narratives and to distract authentic users from information casting the Chinese government in a negative light. Thus, although our studies are focused primarily on evaluating biases on TikTok, they will also explore the possibility, as has been previously reported (Bond, 2023), that Chinese propaganda operations are occurring on other platforms.

The present research explored: (1) whether the amplification of narratives favorable to the CCP's interests and suppression of critical content can be observed across multiple social media platforms, (2) whether the amplification of narratives favorable to the CCP's interests and suppression of critical content are more pronounced on TikTok than on other platforms, and (3) whether users exposed to such content are more favorable toward China's policies and actions.

If a platform like TikTok is subtly advancing CCP interests, we would expect it to present more content favorable to CCP interests while suppressing or distracting users from content unfavorable to CCP interests. This could manifest as an increased prevalence of flattering content about China and a relative absence of critical narratives. Additionally, algorithms might divert users away from critical content by prioritizing irrelevant or neutral material, a tactic that could obscure sensitive topics such as the Uyghur genocide, Tibet, and the Tiananmen Square massacre.

The following overarching research questions guided the three studies reported here:

1. How does the content served on TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube differ in terms of pro- and anti-CCP narratives, particularly concerning sensitive issues like Xinjiang, Tibet, Tiananmen Square, and the Uyghurs (Study I)?

2. Is there any detectable evidence of content bias on TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube in amplifying irrelevant content and pro-CCP content while suppressing anti-CCP content (Study II)?

3. To what extent do TikTok users exhibit more positive attitudes toward China compared to users of other platforms (Study III)?

Study I addressed our first research question: How does the content served on TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube differ in terms of pro- and anti-CCP narratives? For example, do searches on TikTok yield a lower frequency of critical narratives related to sensitive issues such as the Uyghurs, Tibet, and the Tiananmen Square massacre, compared to searches on Instagram and YouTube? We focused on Instagram and YouTube as comparison platforms alongside TikTok due to their prominence as video-sharing platforms with massive global user bases. Like TikTok, both Instagram and YouTube rely heavily on algorithms to recommend and amplify content, making them ideal for assessing whether pro-CCP narratives are disproportionately promoted or anti-CCP narratives suppressed across multiple platforms. By examining Instagram and YouTube, we can determine if TikTok's content moderation and amplification patterns are unique, or if similar biases exist in other widely used, video-centric social media environments.

The Chinese government, through bot networks and hired influencers, can theoretically flood all platforms with pro-CCP, irrelevant, or neutral content to obscure critical narratives. Given that this is a possibility and they have been caught doing it before on Facebook (Bond, 2023), we expect to see high proportions of this content across the board.

In contrast, anti-CCP content would not be as easily censored from platforms not owned by China, such as YouTube and Instagram, which may offer fewer opportunities for direct CCP censorship compared to TikTok. Thus, anti-CCP content may be more prominent on Instagram and YouTube, whereas TikTok might have mechanisms to suppress or limit the visibility of anti-CCP content.

This study implemented a user journey methodology, which simulates the on-platform experience of a newly created, organic user, to evaluate the type of content surfaced by the search algorithm. Importantly, while we cannot directly analyze TikTok's algorithm, we can assess the prominence and frequency of different types of content (pro-CCP interests, anti-CCP interests, irrelevant, or neutral) appearing in search results.

The user journey method has been previously employed by organizations like AI Forensics, a European non-profit, in partnership with Amnesty International, to examine how TikTok influences user engagement, particularly among vulnerable populations (Amnesty International, 2023). If TikTok is being used as a vehicle for advancing CCP interests, we would expect to see certain patterns in the search results. Specifically, Study 1 tested the following hypotheses:

1. Less anti-CCP content on TikTok (i.e., content critical of the Chinese government, particularly related to human rights abuses) compared to Instagram and YouTube.

2. More pro-CCP content (i.e., content supportive of the Chinese government or promoting positive narratives about China) compared to anti-CCP content, across all platforms.

3. More irrelevant or neutral content on TikTok than on the other platforms, a prediction that is explained next.

One potential method of suppressing critical narratives is by distracting users with a flood of irrelevant or neutral content (King et al., 2017). This strategy could obscure or dilute sensitive topics, making it more difficult for users to encounter anti-CCP material. In this context, irrelevant content could include generic videos unrelated to politics (e.g., entertainment or lifestyle content), while neutral content might feature apolitical representations of Chinese culture, history, or geography. Thus, if TikTok is advancing Chinese state interests, searches for sensitive topics (like Uyghur genocide or Tiananmen Square) should produce a higher proportion of irrelevant and neutral content, compared to the same searches on the American-owned platforms, Instagram and YouTube.

The methodological basis of Study I was the user journey (Amnesty International, 2023). A user journey refers to the process of simulating or tracking the steps a typical user would take while interacting with a system, platform, or network. In the context of Open Source Intelligence (OSINT), this involves recreating or following the pathways and interactions that users undergo on social media or other digital platforms to analyze how content is encountered, consumed, and disseminated. The goal is to replicate real-world user behavior to uncover patterns in content delivery, algorithmic bias, and manipulation strategies used by platforms or state actors (Endmann and Keßner, 2016; Rodrigues, 2021).

Keywords to search through the new user accounts were selected given their importance in the CCP's information warfare and propaganda doctrine, which enshrines projecting a positive image of China both inwards and outwards as a core pillar (King et al., 2017).

Uyghur: The term “Uyghur” relates to the predominantly Muslim ethnic minority group in Xinjiang. The CCP has faced international condemnation for alleged human rights abuses, including mass detention camps (BBC, 2020; Sudworth, 2020; Ramzy and Buckley, 2019).

Xinjiang: As the region where the Uyghur population resides, Xinjiang (Zenz, 2019) is a central focus of CCP propaganda.

Tibet: Tibet is another sensitive region for China due to its history of resistance and calls for independence (Barnett, 2012; Bodeen, 2019; Ellis-Petersen, 2021; Shakya, 1999).

Tiananmen: The 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre remains one of the most heavily censored topics in China (Miles, 1996).

The user journey methodology simulated the on-platform experience of a newly created, organic teenage TikTok user account. We chose to create teenage instead of adult user accounts because 25% of U.S. TikTok users are 10–19 years of age (Howarth, 2024) and because extremist actors often target youth to gain adherents (Abalian and Bijan, 2021; Sugihartati et al., 2020). User journey data were collected by creating a total of 24 new accounts on each platform (TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube). To recreate a typical user experience, each account was associated with an IP address in the USA and was labeled as belonging to a 16-year-old user. An equal number of male and female accounts were created.

Both TikTok and Instagram collection was performed on mobile Android phones and recorded using a phone screen recording app called V Recorder, while YouTube collection was done on the computer and recorded using a screen recording tool. A separate account was created for each keyword (“Uyghur,” “Xinjiang,” “Tibet,” “Tiananmen”) per platform to prevent cross-contamination between search terms and to ensure that the platform algorithms were exposed to only the specific keyword and related content. To ensure accuracy and consistency in the results, all browsing history, cookies, and cache were cleared before account creation to avoid any pre-existing biases or algorithmic influences. Beyond account creation, searching for the target search term, scrolling through video results, and saving/bookmarking viewed content, no additional actions were performed that could skew the profile's search preferences (e.g., no accounts were followed, no prior searches were performed, no engagements except views and saves were performed).

A standard collection methodology was followed for all search terms across each platform. Each user began by typing the term into the Search field and selecting the first post that appeared. The users then scrolled through each subsequent video, saving each one on TikTok and Instagram. Each video on YouTube (excluding shorts and videos in playlists), TikTok, and Instagram was played for at least 15 s or until the video concluded. Upon completing the recording session, the users navigated to the Saved page on the User Profile (on TikTok and Instagram) or scrolled back to the top of the list (on YouTube), and the users clicked on each post to copy the upload date and URL into a spreadsheet.

Link retrieval for the search terms across all platforms took place during the first 2 weeks of July 2024. The objective for user journey data collection was to collect the first 300 videos for each of four target search terms (“Uyghur,” “Xinjiang,” “Tibet,” “Tiananmen”) across three different social media platforms (TikTok, YouTube, Instagram).

Following data collection, the first phase of analysis categorized content as either pro-CCP, anti-CCP, neutral, or irrelevant. Search results were independently coded by two analysts. When they disagreed, a third analyst independently coded the search result and assigned a final coding category (i.e., without knowing how the other analysts coded the result). The intercoder agreement rates were high across all platforms and search terms. For instance, TikTok showed agreement rates of 98.94% for “Tibet” and 99.37% for “Tiananmen,” while Instagram and YouTube also demonstrated high agreement, particularly for “Tiananmen” at 99.33 and 100%, respectively. However, lower but still substantial agreement was observed for “Xinjiang,” particularly on Instagram (75.33%) and YouTube (73.67%) (see Table 1).

Our coding system was customized for each search term and served as a blueprint for analysts responsible for the process (see Table 2). It may seem counterintuitive to code news coverage of the Tiananmen Square massacre as “neutral” rather than “anti-CCP.” However, this decision was based on several considerations that align with the goals of maintaining objectivity in our coding process. First, “anti-CCP” content was defined as material explicitly critical of the Chinese government, often involving clear condemnations of its actions or calls for accountability. News reports, even on sensitive topics like the Tiananmen Square massacre, often present information in a more factual, less opinionated manner. These reports focus on recounting events rather than directly criticizing the government, making it appropriate to categorize them as “neutral.” While the subject matter of such news reports may be implicitly critical by shedding light on events that the Chinese government seeks to suppress, the neutral coding reflects the objective, factual nature of news media, as opposed to content that includes explicit criticism, advocacy, or direct opposition to the Chinese government. In this way, we maintained a distinction between fact-based reporting and content with an overtly critical stance, ensuring that the coding process remained consistent across different platforms and topics.

Table 3 presents the total number of search results (links) produced for each search term for each platform. The main analyses focused on discovering whether there were differences in the distribution of anti-CCP, pro-CCP, irrelevant and neutral content produced by the search terms “Tiananmen,” “Tibet,” “Uyghur,” and “Xinjiang” across TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube.

Although our objective was to obtain 300 results for each platform/search term combination, some search feeds stopped serving content before 300 videos per term was reached, resulting in a total of 3,435 video results.

Table 4 summarizes the main results for all platforms and searches. A series of chi-square tests assessed differences among content type (pro-CCP, anti-CCP, neutral, and irrelevant) and platform (TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube). The chi-square results for each content type are reported in Table 5, and show that the content varied significantly by platform.

There are eight substantive comparisons for each search term: two platform comparisons (TikTok compared to Instagram, and TikTok compared to YouTube) by four search terms. In all eight comparisons focused on anti-CCP interest content, the results confirmed the hypothesis that TikTok's search results would be biased in favor of the CCP. TikTok produced far less anti-CCP content than did the other platforms (see Table 4; Figure 1).

Our second hypothesis was that there would be more pro-CCP than anti-CCP content across all platforms. This hypothesis was not confirmed, though the result raised even more reasons to suspect algorithmic bias among TikTok. There was more pro-CCP than anti-CCP content for all four TikTok searches, but no pattern emerged for YouTube or Instagram. Four of eight comparisons involving YouTube and Instagram found more pro-CCP than anti-CCP content, but four of eight found more anti-CCP than pro-CCP content (see Table 4).

Consistent with the distraction hypothesis, the percentage of irrelevant content on TikTok was generally higher across all search terms than on the other platforms. The one exception was for Tibet searches, where YouTube (33%) produced slightly more irrelevant results than did TikTok (30.9%).

Interestingly, there was no consistent evidence that TikTok searches produced more pro-CCP or neutral content than did the other platforms. TikTok did produce more pro-CCP content than did the other platforms for searches involving Tiananmen Square and Tibet, and it produced more pro-CCP content in searches involving Uyghur than did Instagram. However, TikTok produced less pro-CCP content in searches for Uyghur than did YouTube searches, and it produced less pro-CCP content than did both other platforms in searches for Xinjiang. Furthermore, it generally produced about the same or less neutral content for all search terms than did the other platforms. Thus, although Study I provided ample evidence that TikTok produces less anti-CCP and more irrelevant (distracting) content than other platforms, the hypotheses that it would also produce more pro-CCP or neutral content were not confirmed.

The clearest evidence for some sort of bias in TikTok search results was for anti-CCP and irrelevant content. Both results are consistent with some sort of suppression of negative information about CCP on TikTok. It is obvious why the CCP would seek to suppress negative information about the CCP. However, the distraction hypothesis specifically predicted the results for the irrelevant search results—one way to steer users away from unflattering information about CCP is by sending them to links irrelevant to searches on topics about which the CCP is sensitive.

One possibility is that the CCP prefers to steer people away from political links involving the CCP, both positive and negative (King, 2018). This perspective, which is post-hoc and speculative and therefore points to a direction for future research, suggests that CCP policies, though targeting suppression of negative information about the CCP, do not focus on amplifying positive political information about China or the CCP, perhaps in an effort to avoid making anything about the issues addressed here (Tiananmen, Tibet, and the Uyghurs) too salient in people's minds and social media discourse.

This analysis could also explain the stark difference in findings regarding irrelevant vs. neutral search results. Irrelevant links avoid the search topic altogether. Therefore, if they are being used by the CCP to distract people from the topic, steps may have been taken to amplify this sort of content when people search for the terms we examined. In contrast, if the CCP is trying to steer users away from considering topics about which it is sensitive, it will not steer people to neutral content that simply factually reported events involving our four search terms.

There were no clear, consistent differences between TikTok and the other platforms with respect to pro-CCP or neutral content. There was, however, consistently lower anti-CCP content on TikTok. There was also a high amount of irrelevant content across all platforms. These findings suggest that CCP manipulation or influence on TikTok may not exclusively manifest as promoting the CCP's preferred narratives. Instead, it could be understood as a broader strategy that overwhelms search results with irrelevant or distracting content, effectively diluting the visibility of critical material.

The disparities observed across platforms, especially for anti-CCP and irrelevant content, could result from TikTok's parent company, ByteDance, implementing algorithmic processes to disproportionately produce results that align with CCP interests. However, it is also possible that the disparities observed across platforms did not result from any algorithmic manipulation. Instead, perhaps they merely reflect differences in user preferences by platform. It is possible that TikTok attracts a user base more inclined toward the type of content the CCP would like to promote.

The amount of time users spend interacting with content on social media—such as watching a video, liking a post, or leaving a comment—is known as user engagement. Higher engagement with a piece of content makes it more valuable for advertisers because the engaged audience is more likely to notice and respond to ads displayed alongside that content. For example, if a piece of content is ignored by users, any ads paired with it are less likely to be effective, making the ad placement a waste of money. Conversely, if a piece of content is highly popular and engaging, ads placed alongside it have a better chance of reaching an attentive audience and potentially boosting sales (Gharib, 2024).

Social media platforms, driven by commercial goals, aim to maximize ad revenue. To achieve this, they often amplify and promote content that generates high levels of user engagement, as such content tends to be more profitable for advertisers (Reputation Sciences, 2024). This means that the algorithms on these platforms are typically designed to prioritize engaging content, regardless of its specific subject matter, to attract more ad spending (7th Peak Marketing, n.d.).

If TikTok attracts users inclined to engage with pro-CCP content, then it may have more such content for purely commercial reasons, and not because of any algorithmic manipulation. Differences between TikTok and other platforms would then be a reflection of the platform's user demographics and their preferences rather than undue influence by the CCP.

However, if TikTok users disproportionately (compared to users on other platforms) preferred pro-CCP content, we would also expect to see low levels of user engagement with anti-CCP content.

On the other hand, if the CCP has undue influence on TikTok, then content advancing CCP narratives might be amplified even when its user engagement metrics are not particularly high. Similarly, content advancing narratives opposed by the CCP may be suppressed even if user engagement metrics are high.

These alternative possibilities were examined in Study II.

Study II analyzed engagement data from user journeys across TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube to determine whether there are systematic differences in how users interact with different types of content. We investigated how user engagement metrics, specifically likes and comments, aligned with the distribution of pro-CCP and anti-CCP content on TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube. This type of analysis can reveal potential algorithmic biases. In this study, we evaluated bias by calibrating search results against engagement. If engagement drives prominence in search results (appearing early, e.g., within the first 300 results returned for a search), as is typically the case, there would be no evidence of bias or algorithmic manipulation. In contrast, if anti-CCP content had high engagement metrics but was not returned early in search results, or if pro-CCP content had low engagement metrics but was returned early in search results, we interpreted it as evidence of bias or algorithmic manipulation to advance CCP interests or propaganda.

It was, of course, also possible that American-owned platforms (Instagram and YouTube) suppress pro-CCP content or amplify anti-CCP content. Our approach to evaluating anti-CCP bias was identical to our approach to evaluating pro-CCP bias. If anti-CCP content had low engagement metrics but was returned early in search results, or if pro-CCP content had high engagement metrics but was not returned early in search results, we interpreted it as evidence of bias or algorithmic manipulation on the American platforms to suppress information favorable to the CCP.

TikTok's algorithm, according to internal company documents (Smith, 2021), is built around four main goals: “user value,” “long-term user value,” “creator value,” and “platform value.” The underlying design emphasizes maximizing user engagement through retention and time spent on the app, effectively aiming to keep users scrolling for as long as possible. TikTok's recommendation algorithm supposedly scores videos based on several inputs, including:

∘ Likes

∘ Comments

∘ Whether the video was played

∘ Playtime

These factors are combined in a machine-learning-driven equation that assigns scores to each video. Videos with the highest scores are more likely to be shown in users' “For You” feeds. While the actual equation is more complex, the central principle is to promote content that maximizes user engagement by using existing engagement metrics. Moreover, the more engagement a video receives (through likes, comments, and views), the more likely it is to be prioritized by the algorithm, leading to greater visibility in future content recommendations.

Use of these criteria for amplifying content reflects basic commercial interests, not propaganda. However, if TikTok is being used as a vehicle for promoting Chinese propaganda, we would expect to observe distinctive divergences from that predicted by use of these criteria to amplify content. Study I found that the greatest differences between TikTok and the other platforms was for anti-CCP content, and the smallest differences were for pro-CCP content. Therefore, Study II focused exclusively on anti-CCP and pro-CCP engagement. If some sort of algorithmic bias is operating with respect to anti-CCP content, these comparisons would be most likely to uncover it.

Specifically, the unbiased algorithm hypothesis is that:

If the larger amount of pro-CCP than anti-CCP content served up by TikTok is driven by user engagement, then pro-CCP content should receive disproportionately higher engagement (likes and comments) than does anti-CCP content.

Alternatively, the biased algorithm hypothesis is that:

TikTok serves up more pro-CCP than anti-CCP content, even though users engage as much or more with anti-CCP content than with pro-CCP content.

The primary engagement metrics collected were the number of likes, views, shares, and comments associated with each post or video. These metrics were extracted directly from the platform within 2 weeks of content collection. Not all platforms provided the same set of engagement metrics: Instagram provided likes and comments, TikTok provided likes, views, comments, shares, and bookmarks, and YouTube provided views, likes, and comments. Because the only engagement data that is the same across platforms was for likes and comments, our analyses focused exclusively on likes and comments.

It is important to note that some content was taken down after link collection, rendering certain metrics inaccessible. Additionally, comments were restricted on some platforms, such as YouTube, further limiting the available data. For these reasons, when reporting percentages, we are referring only to the total within the available metrics. For example, for Tiananmen Square content on YouTube, although 300 usable links were initially retrieved, the final count reflected 296 links for likes and 276 links for comments, because one of the YouTube videos was removed from the platform, three videos did not report the number of likes, and 24 videos did not allow comments.

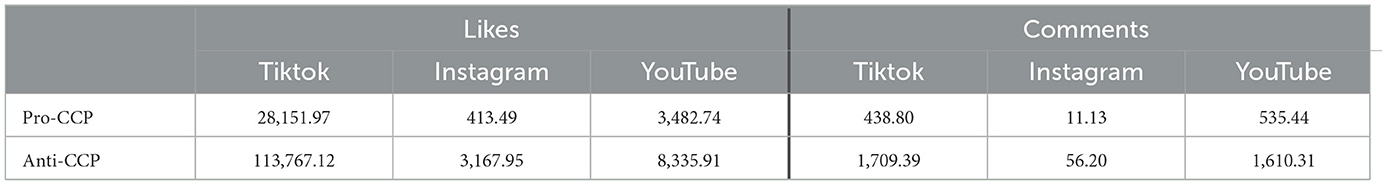

Table 6 reports the average number of likes and comments per search result across TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube.

Table 6. (Study II) Average numbers of likes and comments for each search result link across each platform for pro- and anti-CCP content.

In order to compare support for the unbiased algorithm hypothesis vs. the biased algorithm hypothesis, we computed three ratios: (1) the ratio of pro-CCP to anti-CCP results obtained in Study I, and the ratios of (2) likes for pro-CCP vs. anti-CCP content and (3) comments for pro-CCP vs. anti-CCP content, obtained in the present study.

The unbiased algorithm hypothesis would be supported by results showing that the ratios are similar within and between platforms; this would be the case if purely commercial criteria were being used to amplify content. The biased algorithm hypothesis would be supported by results showing that these ratios would be dramatically different for TikTok than for the other platforms. Specifically, if TikTok suppresses anti-CCP content (which is one interpretation of Study I results), then the ratio of pro-CCP to anti-CCP engagements should be much lower than the ratio of pro-CCP to anti-CCP results found in Study I for TikTok, both on its own and, especially, when compared to the other platforms. In other words, if TikTok makes relatively less anti-CCP (compared to pro-CCP) content available than would be justified by user engagement statistics, it raises the possibility that its algorithm is being used to advance CCP propaganda. Such a result would suggest that TikTok makes it much harder for searches to yield anti-CCP content than pro-CCP content.

Table 7 reports these ratios. It shows that, in Study I, TikTok produced a vastly higher ratio of pro- to anti-CCP content (content ratio) than could be explained by user engagement (likes and comments ratios). On TikTok, users liked or commented on anti-CCP content nearly four times as much as they liked or commented on pro-CCP content, yet the search algorithm produced nearly three times as much pro-CCP content. Neither Instagram nor YouTube showed this extreme a discrepancy between the content ratio and the likes and comments ratios.

Table 7 also provides evidence that bears on the exploratory research question of whether the American-owned platforms (Instagram and YouTube) are biased against the CCP. Such bias would manifest as a lower ratio of pro-CCP to anti-CCP content than engagement ratios for likes and comments. This did not happen. If anything, there might be a modest pro-CCP bias even on the American platforms. On Instagram, users liked or commented on anti-CCP content about five and eight times more frequently, respectively, than they liked or commented on pro-CCP content, yet the search algorithm produced half as much pro-CCP content as anti-CCP content. On YouTube, users liked or commented on anti-CCP content about two to three times as often as they liked or commented on pro-CCP content, yet the search algorithm produced about equal amounts of pro-CCP content and anti-CCP content. Although our methods cannot definitively establish pro-CCP bias on the American platforms, these results warrant further investigation of the potential for such biases in future research.

Regardless of how these results are interpreted, however, TikTok's results are vastly more favorable to the CCP than are results returned by Instagram and YouTube. Furthermore, the TikTok results are a nearly complete inversion of their own engagement metrics.

The results supported the biased algorithm hypothesis. Differences between users' engagement on the different platforms do not explain the differences between the content posted on each platform found in Study I. Across all platforms, users engaged far more with anti-CCP content than with pro-CCP content. TikTok, however, was the only platform that produced vastly more pro-CCP content than anti-CCP content. Thus, differences between users' engagement with pro-CCP and anti-CCP content explains neither why TikTok serves up more pro-CCP than anti-CCP content nor why it serves up far less anti-CCP content than do the other platforms.

In short, Study II results strongly suggest that algorithmic amplification of pro- and anti-CCP content on Instagram and YouTube is largely determined by commercial considerations, whereas advancing CCP propaganda plays some role in the algorithmic curation of TikTok content. Given that Study I found far less anti-CCP content on TikTok than on the other platforms, but not systematically higher levels of pro-CCP content, the results from the two studies, when taken together, strongly suggests that TikTok suppresses anti-CCP content.

Finally, the patterns obtained across both Studies I and II raise important questions about the relationship of such algorithmic content curation to user perceptions. Specifically, if users are exposed to less anti-CCP and more irrelevant content on TikTok than on other platforms—less than might be predicted based on engagement statistics—how does this relate to their overall attitudes toward China? To explore the potential relationship between content exposure and user psychology, we conducted Study III to examine whether social media usage, particularly on TikTok, is associated with users' perceptions of China's human rights record and its appeal as a travel destination.

Building on the insights from Study II, Study III explored the potential real-world association between content exposure and user beliefs about China. In Study III, we conducted a survey to examine whether users' social media habits, particularly on TikTok, were associated with their views on China's human rights record and its appeal as a travel destination.

The rationale for assessing beliefs about China's human rights record is straightforward. Based on the findings from Studies I and II suggesting that TikTok suppresses information about China's human rights violations, Study III tested the hypothesis that:

The more time users spend on TikTok, the more positively they may view China's human rights record.

We also assessed beliefs about China as a travel destination because: 1. Encouraging tourism in China is in the CCP's interest; 2. Some search results directed people to tourist destinations; and 3. Previous work in this vein by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) shows that the CCP makes a concerted effort to influence perceptions of China through online travel videos. As an ASPI report (Ryan et al., 2022) remarks, seemingly benign travel videos made by “frontier influencers” are directly managed by the CCP to shape perceptions of China abroad, particularly relating to sensitive frontier regions like Tibet and Xinjiang.

A frontier influencer refers to social media personalities or content creators who focus on promoting tourism and cultural narratives in geographically sensitive or politically contested regions, often at the behest of government authorities. In the context of China, these influencers are used by the CCP to produce and amplify content that portrays areas like Tibet and Xinjiang in a favorable light. These regions, known for their complex histories of human rights concerns and ethnic tensions, are critical to China's domestic and international image. Thus, an additional hypothesis was generated by the possibility that TikTok is being exploited to advance CCP interests:

The more time users spend on TikTok, the more desirable they will view China as a tourist destination.

One thousand two hundred and fourteen U.S. adult participants were recruited through Amazon's Prime Panels CloudResearch service. The sample was matched to U.S. census data and stratified to ensure greater representativeness across demographic categories. The full set of demographic information on this sample is reported in the Supplementary material.

The survey assessed: (1) time spent on social media platforms; (2) evaluation of human rights violations for 10 countries, including China; and (3) evaluation of China as a travel destination. The Supplementary material presents all survey questions reported here.

Participants reported the amount of time they spend daily on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, X (Twitter), Reddit, and YouTube, with response options ranging from “Never” to “More than 3 hours.” See Supplementary material for details about participants' social media use per platform (Supplementary Table S1; Supplementary Figure S1).

Participants rated the human rights records of 10 countries (China, USA, Iran, Switzerland, Israel, Mexico, North Korea, Australia, Cuba, and Sudan) using a sliding scale ranging from 1 (extremely poor) to 10 (extremely good). This section was randomized to disguise the purpose of the survey. Analyses reported herein focus exclusively on China, but ratings for all countries are available in Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Figure S2.

Participants' beliefs about China as a travel destination were also assessed. Participants answered “True” or “False” to the following statement: “China is one of the most desirable travel destinations in the world.”

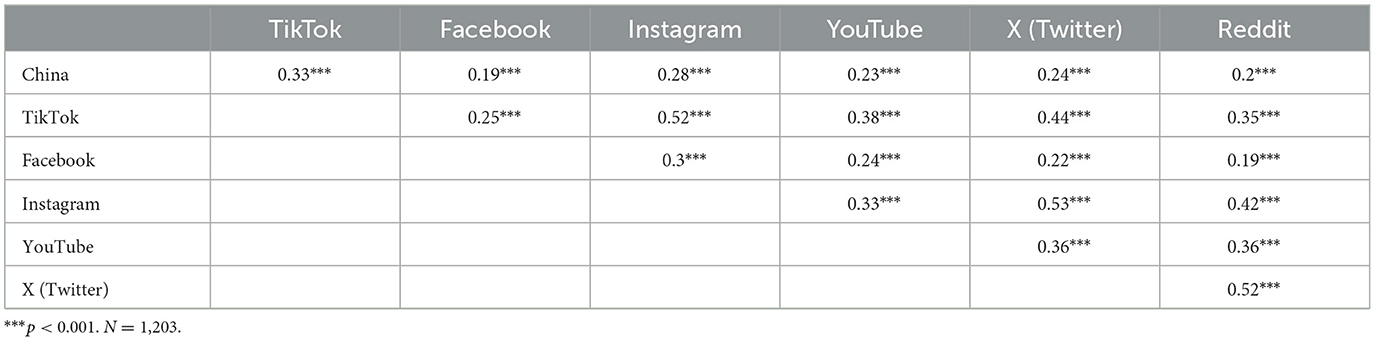

We first tested the hypothesis that the more time people spend on TikTok, the more positively they would view China's human rights record. Table 8 reports the correlations among time spent on each platform and ratings of China's human rights record. This hypothesis was confirmed: the correlation between time reported spending on TikTok usage and ratings of China's human rights record was r(1,212) = 0.33, p < 0.001.

Table 8. (Study III) Correlations for China human rights rating and time spent on social media platforms.

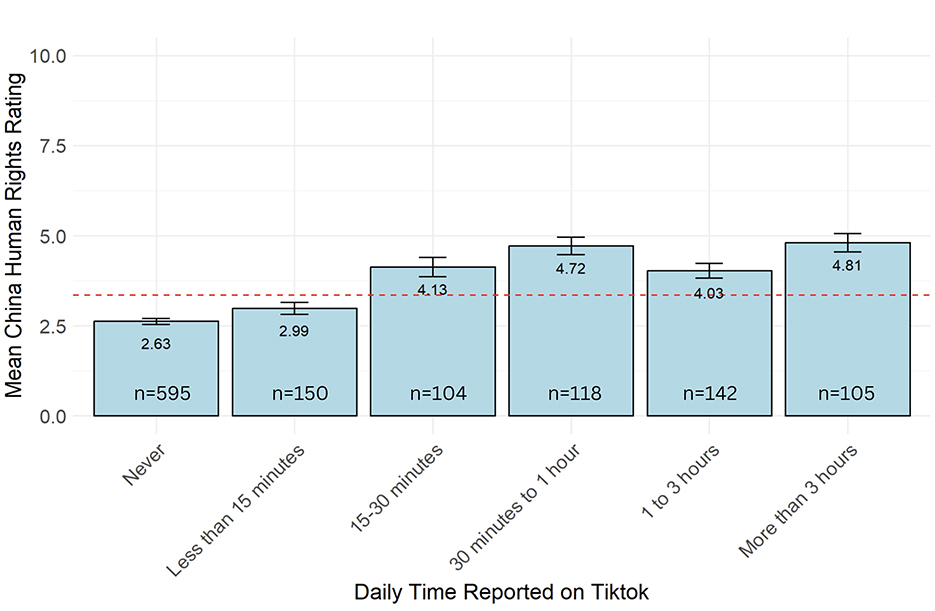

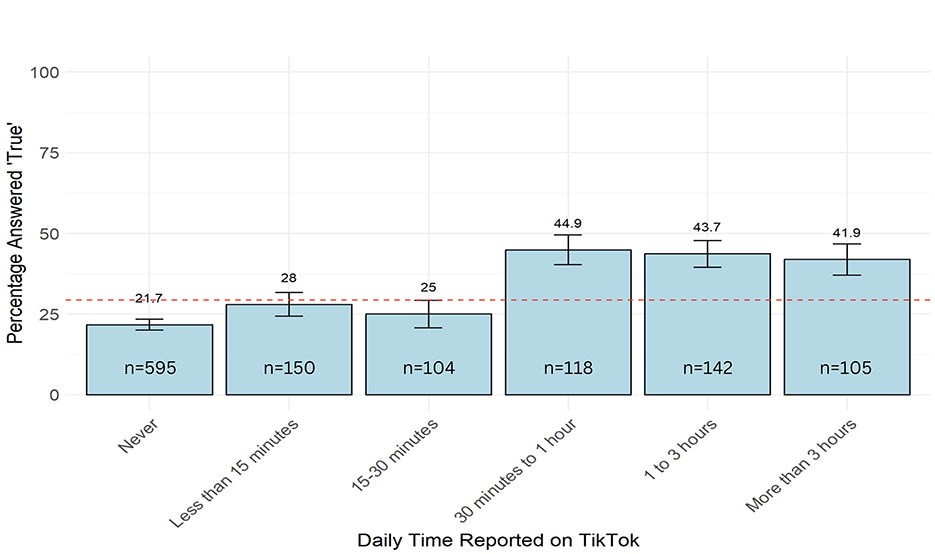

Figure 2 presents the mean ratings of China's human rights record based on varying levels of TikTok usage. Although the pattern is not completely linear, those who reported spending no time on TikTok held the least favorable views of China's human rights record and those who reported spending more than 3 h per day on TikTok had the most favorable views.

Figure 2. Mean China human rights ratings by TikTok usage. The red dotted line denotes the sample mean.

However, as can also be seen in Table 8, time spent on all the platforms was positively correlated with views of China's human rights record (i.e., the more time spent on any of the platforms, the more favorable the view respondents held of China's human rights record). Therefore, we conducted follow-up analyses to examine whether this relationship was stronger for time spent on TikTok than for time spent on the other platforms.

As can be seen in Table 8, the r = 0.33 correlation for TikTok was higher than that for any other platform. A series of z-tests compared the r = 0.33 found for TikTok use to the r found for the other platforms. This analysis indicated that the correlation for TikTok was significantly higher than that for Facebook (z = 3.721, p = 0.0002), Reddit (z = 3.579, p = 0.0003), YouTube (z = 2.695, p = 0.0070) and X (formerly Twitter) (z = 2.521, p = 0.0116). However, the comparison between TikTok and Instagram did not reach statistical significance (z = 1.387, p = 0.1654).

Table 8 also makes clear that time spent on TikTok was itself moderately to highly correlated with use of the other platforms. This raised the possibilities that TikTok use is driving much of the correlation between time spent on the other platforms and ratings of China's human rights record, or that use of other platforms is driving much of the relationship between TikTok use and ratings of China's human rights record. In addition, it was possible that there were demographic differences in the use of the different platforms which might explain some or most of the relationship between time spent on TikTok to ratings of China's human rights record. For example, if, independent of any use of TikTok, younger people have more positive views of China's human rights record and are also more likely than older people to spend time on TikTok, this could account for some or all of the correlation between TikTok use and ratings of China's human rights record. A similar analysis applies to other demographic variables as well.

Table 9 reports the correlations between platform use and the demographic variables we assessed. Indeed, TikTok use was negatively correlated with age [r(1,212) = −0.51, p < 0.001] and was correlated with political affiliation [r(1,212) = −0.09, p < 0.01], ethnicity [r(1, 212) = −0.18, p < 0.001], and gender [r(1,201) = 0.1, p < 0.001]. Table 9 reports how the demographic variables were coded in order to interpret the correlations with TikTok use.

Therefore, we conducted a regression analysis to evaluate whether TikTok use predicted beliefs about China's human rights record over and above time spent on the other platforms and independent of user demographics. Specifically, the regression model included time spent on each of the platforms, age, gender, ethnicity, and political affiliation as predictors of beliefs about China's human rights record.

Those results, which are presented in Table 10, show that TikTok use still predicted beliefs about China's human rights record. Specifically, the relationship of time spent on TikTok to ratings of China's human rights record remained substantial and statistically significant (b = 0.182, β = 0.134, p < 0.001). Thus, neither time spent on other platforms nor demographics fully explain the relationship of time spent on TikTok with ratings of China's human rights record. Furthermore, usage of the other platforms did not predict ratings of China's human rights record, with the exception of Facebook (b = 0.146, β = 0.099, p < 0.01). Understanding why time spent on Facebook also predicts ratings of China's human rights record is, however, beyond the scope of the present investigation and is not discussed further. Among demographic variables, age (b = −0.02, β = −0.15, p < 0.001) and ethnicity (b = −0.42, β = −0.17, p < 0.01) were significant negative predictors, indicating that older and White participants rated China's human rights record as worse than did younger and non-White participants.

Overall, therefore, these analyses confirmed the hypothesis that the more time users spend on TikTok, the more favorable their views of China's human rights record. This relationship was observed in the bivariate correlation between TikTok use and ratings of China's human rights record, and it remained statistically significant even when controlling for time spent on each of the other platforms, demographics, and political affiliation.

Next, we tested the hypothesis that the more time spent on TikTok, the more favorably respondents would rate China as a travel destination. Because the question asked them to rate as true or false the statement “China is one of the most desirable travel destinations in the world,” the hypothesis predicts that the more time people spend on TikTok, the more likely they would be to evaluate the statement as “true.”

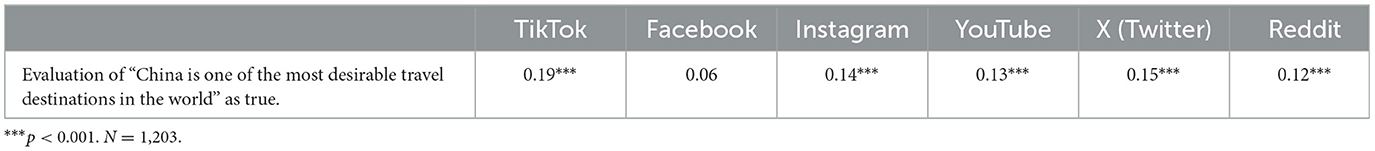

Table 11 reports the correlations between time spent on each platform and ratings of China as a travel destination. The hypothesis that time spent on TikTok would correlate with ratings of China as a travel destination was supported, r(1,212) = 0.19, p < 0.001.

Table 11. (Study III) Correlations between social media use and evaluation of China as a desirable travel destination.

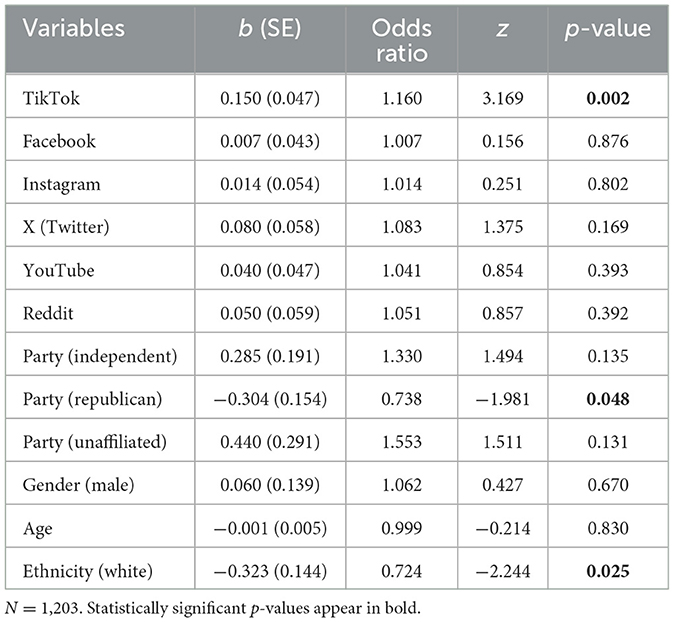

Figure 3 presents the mean ratings of China as a travel destination based on varying levels of TikTok usage. Although the pattern is not monotonic, there is a clear and dramatic difference between those who spend 0–30 min on TikTok and those who spend 30 min or more.

Figure 3. Percentage of users who chose “true” for China is one of the most desirable travel destinations in the world. The red dotted line denotes the sample mean.

As can be seen in Table 11, time spent on all the platforms was positively correlated with views of China as a travel destination, though the relationship for Facebook was not statistically significant. The r = 0.19 correlation for TikTok was higher than that for any other platform, so we conducted follow-up analyses to examine whether this relationship was significantly stronger for time spent on TikTok than for time spent on the other platforms. A series of z-tests indicated that the correlation for TikTok was significantly higher than that for Facebook (z = 3.288, p = 0.001). However, the comparisons with X (formerly Twitter) (z = 1.55, p = 0.248), YouTube (z = 1.614, p = 0.107), Instagram (z = 1.495, p = 0.135), and Reddit (z = 1.798, p = 0.072) did not reach statistical significance.

Because TikTok use was correlated with use of other platforms (Table 8) and several of the demographic variables (Table 9), further analyses assessed whether the association of TikTok use with ratings of China as a travel destination was robust while controlling for these other variables. Because ratings of China as a travel destination was a dichotomous variable, we conducted a logistic regression, with time spent on each of the platforms and the demographic variables as predictors. Table 12 reports these results.

Table 12. (Study III) Logistic regression results for true/false responses to “China is one of the most desirable travel destinations in the world.”

The results indicated that TikTok usage significantly predicted agreement with the statement [β = 0.15, SE = 0.047, OR (odds ratio) = 1.16, p = 0.002], suggesting that higher TikTok usage was associated with a greater likelihood of viewing China as a desirable travel destination. Facebook, Instagram, X (Twitter), YouTube, and Reddit usage were not significant predictors in this model. Republicans were less likely than Democrats to agree that China was one of the world's most desirable travel destinations (b = −0.304, SE = 0.154, OR = 0.738, p = 0.048). Ethnicity was also a significant predictor, with fewer White than non-White respondents rating China as one of the world's most desirable travel destinations (b = −0.323, SE = 0.144, OR = 0.724, p = 0.025).

Overall, therefore, these analyses confirmed the hypothesis that the more time users spend on TikTok, the more favorable their views of China as a travel destination. This relationship was observed in the bivariate correlation between TikTok use and ratings of China as a travel destination, and it remained statistically significant even when controlling for time spent on each of the other platforms, demographics, and political affiliation. Use of the other platforms did not significantly predict ratings of China as a travel destination when controlling for TikTok use. This means that the correlation of use of the other platforms with ratings of China as a travel destination is probably being driven primarily by TikTok use, which correlated with use of the other platforms (Table 8).

The three studies reported herein examined evidence about the content available on TikTok and its relationship to user beliefs about China. Study I found that TikTok produced far less anti-CCP content and far more irrelevant content than did other platforms when our simulated users searched for “Tiananmen,” “Tibet,” “Uyghur,” and “Xinjiang.” Study II found that the pro-CCP content that emerged from our user journey methodology was amplified disproportionately when compared to anti-CCP content on TikTok, despite massively more user engagement (i.e., likes, comments) with anti-CCP content than with pro-CCP content. In contrast, the content that was amplified on other platforms was approximately proportionate to user engagement metrics. Study III found that the more time real users reported spending on TikTok, the more positively they viewed China's human rights record and China as a travel destination. These relationships were robust to controls for time spent on other platforms and a slew of demographic variables.

Taken together, the findings from these three studies raise the distinct possibility that TikTok is a vehicle for CCP propaganda. The three studies reported here focused exclusively on the content served up by TikTok's search algorithm and did not provide evidence regarding direct CCP interference in TikTok. We did not have evidence regarding CCP influence on the TikTok corporate board or among its algorithm designers. Nonetheless, such evidence has been reported elsewhere. NBC News (Dilanian, 2024) recently stated they had obtained a report concluding that TikTok “...is deeply entangled with some of China's major government propaganda organs.” The report stated that a Chinese government company holds a 1% interest in ByteDance (TikTok's parent company), giving it “golden shares,” which come with “...three director's seats and other special privileges.” The report also stated that “TikTok says there is nothing unusual about the structure”—which, in our view, may be precisely the problem.

Despite the concerning nature of the findings of the three studies reported herein, the research has some important limitations. First, this research was exploratory and was not pre-registered. As such, all findings should be considered preliminary pending replication, especially by independent teams of researchers.

Second, our research in Studies I and II relied on the analysis of content served up to newly created accounts. While this methodology is designed to mimic the experience of typical users, it does not account for personalized content that may be delivered based on individual user histories and interactions over time. Consequently, the data may not fully capture the breadth of content experienced by the average American teen user. Relatedly, our simulated users were teens, so whether similar patterns of content would be served up to adult users or users under 16 years of age was not addressed in the present research.

Additionally, the coding and classification of content as pro-CCP, anti-CCP, neutral, or irrelevant involved subjective judgments. Although efforts were made to minimize subjectivity, the potential for interpretative differences remains. Furthermore, our study did not explore the full range of user engagement metrics, such as views and shares, which are also used by algorithms to decide which content to amplify. Moreover, we did not have direct access to TikTok's algorithm or insider information. This means that we can only speculate on why the platform suppresses anti-CCP content. It could be a deliberate decision made by the platform's parent company, ByteDance, to stay in good graces with the CCP. It could reflect the direct influence of political pressure from the CCP on TikTok. It could be an unintended consequence of algorithmic design that is unique to TikTok and which does not characterize other social media platforms. Without transparency from the company, we cannot definitively determine whether this content prioritization is purposeful or accidental.

Furthermore, our sample in Study III, though large and stratified to correspond to U.S. demographics for greater representativeness, was not a truly representative sample. As an opt-in sample, every adult American did not have an equal chance of being selected. Whether the results generalize to the American population, then, remains an open question.

Because Study III was nonexperimental, its results were insufficient to definitively conclude that more time spent on TikTok caused people to develop more favorable views of China's human rights record or of its desirability as a travel destination. Although the positive relationship between reported time spent on TikTok and these outcomes was larger than that for other social media companies, and robust to many controls, it remains possible that Study III omitted some variable that can account for that relationship. It is also possible that causality runs in the other direction; perhaps holding uniquely favorable views of China (independent of their demographics, use of other platforms, and political affiliation, which were controlled) causes people to spend more time on TikTok. In principle, these are alternative but not necessarily competing explanations. It is possible that all three causal mechanisms occur simultaneously (TikTok use increases favorability toward China; a priori favorability toward China increases TikTok use, and some as yet unidentified third variable causes both TikTok use and attitudes toward China). Future research employing experimental or longitudinal methodologies would be useful to tease apart these explanations.

Last, the present studies only focused on understanding biases in social media platform search results regarding terms that could produce content that the CCP would rather have suppressed or amplified. Whether potential CCP exploitation of social media is similar to, worse than, or not as bad as that conducted by other national governments was not addressed by the present studies.

As hypothesized, our Study I simulated TikTok users encountered biased content, a result that could not easily be explained by user engagement metrics (Study II). The more time real people reported spending on TikTok (Study III), the more their perceptions and attitudes favored CCP interests. Furthermore, evidence from the present three studies and other reports (Dilanian, 2024; Ryan et al., 2022) converges on the conclusion that the CCP is advancing its propaganda by manipulating social media. Thus, even though the present studies were not definitive, a plausible case is growing that suggests that one avenue of such manipulation may be occurring through TikTok.

Our findings are also consistent with other reports finding that the CCP has shifted away from “hard” propaganda (exaggerated claims glorifying the nation and party, which is mostly intended to coerce rather than persuade) to “soft” propaganda (presentation of positive information about the nation and party presented through mass and social media, generally making less extreme and more credible claims, e.g., Mattingly and Yao, 2022). Indeed, anti-American and anti-Japanese soft propaganda has been found to be quite effective in increasing anger and anti-American and anti-Japanese sentiment within China (Mattingly and Yao, 2022). If the CCP propaganda apparatus believes in the effectiveness of anti-foreign propaganda, a natural extension would be to attempt to blunt the effectiveness of anti-CCP information—which is consistent with the findings of Studies I and II regarding the suppression of such information on TikTok and the distraction hypothesis.

China has a vast propaganda apparatus that starts with the national level Propaganda Department (Shambaugh, 2007; Tsai, 2021). CCP documents are quoted by Shambaugh (2007, p. 27) as stating that the CCP's Propaganda Department is responsible for overseeing “newspaper offices, radio stations, television stations, publishing houses, magazines, and other news and media departments…” and much more. Although Shambaugh (2007) was published long before the explosion of social media usage, exploitation of social media to advance CCP propaganda was a natural adaptation of existing practices, and has itself been amply documented (King et al., 2017; Ryan et al., 2022). Thus, there are growing reasons that go well-beyond the results of the three studies reported herein to be concerned about CCP manipulation of information online for propaganda purposes.

Free inquiry can be abridged through algorithmic manipulation of social media platforms to carefully indoctrinate masses and not only through hard propaganda and censorship. Our research highlights how algorithmic manipulation may undermine free expression and free inquiry, and advance authoritarian agendas by suppressing information about human rights transgressions. Although more research is clearly needed, there is a sufficient body of evidence to conclude that there is an urgent need for greater transparency in social media platform algorithms. Developing robust methods to pressure test algorithms and detect when they subvert free expression and inquiry without user consent should be a priority for researchers and policymakers alike interested in preserving democratic practices and values in the face of threats from authoritarian actors.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://osf.io/zkarg/.

The studies involving humans were approved by Rutgers Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. The social media data was accessed and analyzed in accordance with the platforms' terms of use and all relevant institutional/national regulations.

LJ: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DF: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SY: Data curation, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AniJ: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CV: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AnkJ: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JF: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

A preliminary report, using partially overlapping data, was published by the NCRI in August of 2024.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://osf.io/zkarg/.

1. ^“Operations in the information environment” is the term currently used by the U.S. government (Congressional Research Service, 2024) to refer to “the aggregate of social, cultural, linguistic, psychological, technical, and physical factors that affect how humans and automated systems derive meaning from, act upon, and are impacted by information, including the individuals, organizations, and systems that collect, process, disseminate, or use information.”

7th Peak Marketing (n.d.). Understanding Social Media Algorithms: 6 Key Insights for Maximizing Your Reach. 7th Peak Marketing. Available at: https://www.7thpeakmarketing.com/blog/understanding-social-media-algorithms-6-key-insights-for-maximizing-your-reach?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed September 2, 2024).

Abalian, A. I., and Bijan, A. (2021). Youth as an object of online extremist propaganda: The case of the IS. RUDN J. Polit. Sci. 23, 78–96. doi: 10.22363/2313-1438-2021-23-1-78-96

Amnesty International (2023). Driven Into Darkness: How TikTok's ‘For You' Feed Encourages Self-Harm and Suicidal Ideation. Available at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/POL40/7350/2023/en/ (accessed September 2, 2024).

Backlinko (2024). TikTok Statistics You Need to Know. Available at: https://backlinko.com/tiktok-users (accessed September 2, 2024).

Barnett, R. (2012). Restrictions and their anomalies: the third phase of reform in Tibet. J. Curr. Chin. Aff. 41, 47–86. doi: 10.1177/186810261204100403

BBC (2020). China Forcing Birth Control on Uighurs to Suppress Population, Report Says. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-53220713 (accessed September 2, 2024).

Benkler, Y., Faris, R., and Roberts, H. (2018). Network Propaganda: Manipulation, Disinformation, and Radicalization in American Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bodeen, C. (2019). As Tibetans Mark 60 Years Since Dalai Lama Fled, China Defends Policies. PBS. Available at: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/as-tibetans-mark-60-years-since-dalai-lama-fled-china-defends-policies (accessed September 2, 2024).

Bond, S. (2023). Meta Warns That China Is Stepping Up Its Online Social Media Influence Operations. NPR. Available at: https://www.npr.org/2023/11/30/1215898523/meta-warns-china-online-social-media-influence-operations-facebook-elections (accessed September 2, 2024).

Bradshaw, S., and Howard, P. N. (2019). The Global Disinformation Order: 2019 Global Inventory of Organised Social Media Manipulation. Oxford: Oxford Internet Institute.

Charon, P., and Jeangène Vilmer, J.-B. (2021). Chinese Influence Operations: A Machiavellian Moment. The Institute for Strategic Research (IRSEM), Paris, Ministry for the Armed Forces. Available at: https://www.irsem.fr/en/report.html (accessed September 2, 2024).

Congressional Research Service (2024). Defense primer: Information operations (CRS Report No. IF10771). Federation of American Scientists. Available at: https://sgp.fas.org/crs/natsec/IF10771.pdf (accessed September 2, 2024).

Costello, T. H., Bowes, S. M., Stevens, S. T., Waldman, I. D., Tasimi, A., and Lilienfeld, S. O. (2022). Clarifying the structure and nature of left-wing authoritarianism. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 122:135. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000341

Dikötter, F. (2016). The Cultural Revolution: A People's History, 1962–1976. Great Britain: Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

Dilanian, K. (2024). TikTok Says It's Not Spreading CHINESE Propaganda. The U.S. Says There's a Real Risk. What's the Truth? NBC News. Available at: https://www.nbcnews.com/investigations/tiktok-says-not-spreading-chinese-propaganda-us-says-real-risk-rcna171201 (accessed September 2, 2024).

Ellis-Petersen, H. (2021). Tibet and China clash over next reincarnation of the Dalai Lama. The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jul/31/tibet-and-china-clash-over-next-reincarnation-of-the-dalai-lama (accessed September 2, 2024).

Elswah, M., and Howard, P. N. (2020). “Anything that causes chaos”: the organizational behavior of Russia Today (RT) and Islamic State (IS) on Twitter. J. Commun. 70, 620–644. doi: 10.1093/joc/jqaa027

Endmann, A., and Keßner, D. (2016). User journey mapping – A method in user experience design. i-com 15, 105–110. doi: 10.1515/icom-2016-0010

Freedom House (2023). Freedom on the Net 2023: Iran. Available at: https://freedomhouse.org/country/iran/freedom-net/2023 (accessed September 2, 2024).

Gharib, R. (2024). The Impact of Social Media Marketing on Sales Increase. ProfileTree. Available at: https://profiletree.com/social-media-marketing-sales-increase/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed September 2, 2024).

Gunitsky, S. (2015). Corrupting the cyber-commons: social media as a tool of autocratic stability. Perspect. Polit. 13, 42–54. doi: 10.1017/S1537592714003120

Guriev, S., and Treisman, D. (2020). Spin dictators: The changing face of tyranny in the 21st century. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Herman, E. S., and Chomsky, N. (1988). Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media. New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

Howarth, J. (2024). TikTok User Age, Gender, and Demographics. Exploding Topics. Available at: https://explodingtopics.com/blog/tiktok-demographics (accessed September 2, 2024).

Kalathil, S. (2020). The evolution of authoritarian digital influence: grappling with the new normal. PRISM 9, 32–51.

King, G. (2018). Gary King on Reverse engineering Chinese government information controls. Taiwan. J. Polit. Sci. 78, 1–16. doi: 10.6166/TJPS.201812_(78).0001

King, G., Pan, J., and Roberts, M. E. (2017). How the Chinese government fabricates social media posts for strategic distraction, not engaged argument. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 111, 484–501. doi: 10.1017/S0003055417000144

Kraidy, M. (2017). The Naked Blogger of Cairo: Creative Insurgency in the Arab World. Cambridge; London: Harvard University Press.

Krekó, P. (2022). The birth of an illiberal informational autocracy in Europe: a case study on Hungary. J. Illiber. Stud. 2, 55–72. doi: 10.53483/WCJW3538

Maréchal, N. (2017). Networked authoritarianism and the geopolitics of information: understanding Russian Internet policy. Media Commun. 5, 29–41. doi: 10.17645/mac.v5i1.808

Mattingly, D. C., and Yao, E. (2022). How soft propaganda persuades. Comp. Polit. Stud. 55, 1569–1594. doi: 10.1177/00104140211047403

Mejias, U. A., and Vokuev, N. E. (2017). Disinformation and the media: the case of Russia's ‘news'. Media, Cult. Soc. 39, 1027–1042. doi: 10.1177/0163443716686672

Michaelsen, M. (2018). Transforming threats to power: the international politics of authoritarian internet control in Iran. Int. J. Commun. 12, 3856–3876. Available at: https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/8544/2462

Miles, J. A. (1996). The Legacy of Tiananmen: China in Disarray. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

NCRI (2023). A Tik-Tok-ing Timebomb: How TikTok's Global Platform Anomalies Align With the Chinese Communist Party's Geostrategic Objectives. Available at: https://networkcontagion.us/reports/12-21-23-a-tik-tok-in-timebomb-how-tiktoks-global-platform-anomalies-align-with-the-chinese-communist-partys-geostrategic-objectives/ (accessed September 2, 2024).

Office of the Director of National Intelligence (2021). Annual Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community. U.S. Government Printing Office. Available at: https://www.dni.gov/index.php/newsroom/reports-publications/reports-publications-2021/3532-2021-annual-threat-assessment-of-the-u-s-intelligence-community (accessed September 2, 2024).

Ramzy, A., and Buckley, C. (2019). ‘Absolutely No Mercy': Leaked Files Expose How China Organized Mass Detentions of Muslims. The New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/11/16/world/asia/china-xinjiang-documents.html (accessed September 2, 2024).

Reputation Sciences (2024). How Does Algorithm Work on Social Media Platforms? Reputation Sciences. Available at: https://www.reputationsciences.com/how-does-algorithm-work-on-social-media-platforms/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed September 2, 2024).

Rodrigues, M. A. (2021). Dynamic OSINT System Sourcing From Social Networks (Publication No. 28762451) (Master's thesis, Universidade da Beira Interior, Portugal). ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Rosenbach, E., and Mansted, K. (2018). The Geopolitics of Information. Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School. Available at: https://www.belfercenter.org/publication/geopolitics-information (accessed September 2, 2024).

Ryan, F., Impiombato, D., and Pai, H.-T. (2022). Frontier Influencers: The New Face of China's Propaganda. Australian Strategic Policy Institute. Available at: https://www.aspi.org.au/report/frontier-influencers (accessed September 2, 2024).

Shakya, T. (1999). The Dragon in the Land of Snows: A History of Modern Tibet Since 1947. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Shambaugh, D. (2007). “China's propaganda system: institutions, processes and efficacy,” in Critical Readings on the Communist Party of China (4 Vols. Set), eds. K. E. Brodsgaard, C. Shei, W. Wei (Leiden; London: Brill), 713–751.

Smith, B. (2021). How TikTok Reads Your Mind. The New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/05/business/media/tiktok-algorithm.html (accessed September 2, 2024).

Sudworth, J. (2020). China Uighurs: A Model's Video Gives a Rare Glimpse Inside Internment. BBC News. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-53650246 (accessed September 2, 2024).

Sugihartati, R., Suyanto, B., and Sirry, M. I. (2020). The shift from consumers to prosumers: susceptibility of young adults to radicalization. Soc. Sci. 9:40. doi: 10.3390/socsci9040040

Tsai, W. H. (2021). “The Chinese Communist Party's control of online public opinion: toward networked authoritarianism,” in The Routledge Handbook of Chinese Studies (Routledge), 493–504.

Tufekci, Z. (2017). Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest. New Haven; London: Yale University Press.

United States Senate Select Committee on Intelligence (2019). Russian Active Measures Campaigns and Interference in the 2016 U.S. election: Volume 2: Russia's Use of Social Media. U.S. Senate. Available at: https://www.intelligence.senate.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Report_Volume2.pdf (accessed September 2, 2024).

Woolley, S. C., and Howard, P. N. (2018). Computational Propaganda: Political Parties, Politicians, and Political Manipulation on Social Media. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

York, J. C. (2010). The Arab digital vanguard: How a decade of blogging contributed to a new Arab Spring. Georgetown J. Int. Aff. 11, 17–23.

Yourman, J. (1939). Propaganda techniques within Nazi Germany. J. Educ. Sociol. 13, 148–163. doi: 10.2307/2262307

Keywords: authoritarian foreign influence, information manipulation, propaganda, Chinese Communist Party, social media, TikTok

Citation: Finkelstein D, Yanovsky S, Zucker J, Jagdeep A, Vasko C, Jagdeep A, Jussim L and Finkelstein J (2025) Information manipulation on TikTok and its relation to American users' beliefs about China. Front. Soc. Psychol. 2:1497434. doi: 10.3389/frsps.2024.1497434

Received: 17 September 2024; Accepted: 30 December 2024;

Published: 28 January 2025.

Edited by:

Shannon Houck, Naval Postgraduate School, United StatesReviewed by: