- 1Department of Psychological Sciences, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, United States

- 2School of Nursing, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, United States

Introduction: Modern racism, nationalism, and sexism have been proposed as major influences on contemporary U.S. politics. However, most work has not examined these interrelated factors together. Thus, it is unclear to what extent each form of prejudice uniquely contributes to political behavior. Furthermore, the potential motivations underlying the link between prejudice and politics have not been well elucidated. We sought to (1) determine the extent to which racism, sexism, and nationalism were uniquely associated with political outcomes in the 2020 U.S. presidential election and (2) use the dual-process motivational model to examine whether social dominance orientation (SDO) and right-wing authoritarianism (RWA) were potential motivations underlying the link between prejudice and political attitudes and behavior.

Methods: A national sample of U.S. adults (N = 531) completed online questionnaires before and after the 2020 U.S. election. Structural equation modeling was used to test mediational models in which SDO and RWA prospectively predicted presidential candidate evaluations and vote choice indirectly through racism, sexism, and nationalism.

Results: When examined in conjunction, modern racism (not sexism or nationalism) was consistently associated with evaluations of both candidates and vote choice. Furthermore, SDO and RWA both exerted indirect effects on candidate evaluations and vote choice through modern racism.

Discussion: These results are aligned with previous findings indicating that racism plays a unique role in U.S. politics and may be motivated by status threat experienced by some majority group members.

1 Introduction

Prejudice has influenced U.S. politics since the nation's founding (Clayton et al., 2021; Wolbrecht, 2010), but its role in presidential elections has recently received a lot of scrutiny. Pundits and researchers have especially emphasized the impact of racism, nationalism, and sexism on contemporary voting patterns (Brownstein, 2019; Feffer, 2017; Thomson-DeVeaux, 2019). Indeed, these prejudices were associated with the outcomes of Barack Obama's presidential bids (Payne et al., 2010; Knuckey and Kim, 2015) and Donald Trump's 2016 victory over Hillary Clinton (Schaffner et al., 2018; Bonikowski et al., 2021). Although research has linked racism, nationalism, and sexism to U.S. politics, most scholarship has examined the three prejudices separately. However, these prejudices are generally related, such that people who are higher in one prejudice tend to be higher in the others (Sidanius and Pratto, 2001; Duckitt, 2001; De Figueiredo and Elkins, 2003). Thus, the extent to which each form of prejudice uniquely contributes to political outcomes is not well understood. Furthermore, the motivations underlying the role of these prejudices in politics have not been clearly elucidated.

There were two main objectives of this study. First, we assessed all three prejudices in tandem to determine the extent to which each form of prejudice uniquely and prospectively predicted candidate evaluations and voting behavior in the 2020 U.S. presidential election. Second, we applied the dual-process motivational (DPM; Duckitt, 2001) model—-a framework for understanding the motives behind prejudice and political decision making—-to determine whether social dominance orientation (SDO; Pratto et al., 1994) and right-wing authoritarianism (RWA; Altemeyer, 1981) served as potential underlying motivations to the role of prejudice in the 2020 U.S. presidential election (Duckitt and Sibley, 2010).

1.1 Prejudice and politics

In the U.S., anti-Black racism has been empirically tied to political attitudes and behavior for decades (Clayton et al., 2021; Davis and Wilson, 2021; Bonilla-Silva, 2019; Kinder and Sears, 1981). Although overt displays of racism persist in U.S. society, covert expressions of the prejudice have become more common (Bonilla-Silva, 2019). Modern racism reflects these covert displays of anti-Black prejudice, which include opposing policies that benefit Black Americans and denying the existence of racism (McConahay, 1986). In contemporary elections, higher racism was associated with opposition to former president Barack Obama and support for his Republican opponents in 2008 (Pasek et al., 2009; Payne et al., 2010; Piston, 2010; Dwyer et al., 2009; Parker et al., 2009) and 2012 (Knuckey and Kim, 2015; Jardina, 2021). In 2016, anti-Black racism was related to support for Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton (Alamillo, 2019; Fording and Schram, 2023; Schaffner et al., 2018; Abramowitz and McCoy, 2019) and accounted for Trump support to a greater extent than other popular explanations, like opposition to political elites (Hooghe and Dassonneville, 2018) or economic disenfranchisement (Mutz, 2018). Anti-Black racism particularly disadvantages Black candidates, but it affects electoral politics regardless of candidates' racial identities and has been linked to lower support for White Democrats unaffiliated with the Obama administration (Buyuker et al., 2021; Schaffner, 2022).

Nationalism is another type of bias that has been associated with U.S. politics (Adorno et al., 1950; McFarland, 2010). Throughout U.S. history, politicians from all parties have drawn on nationalistic sentiments to motivate voter support (Bonikowski et al., 2022). However, partisan differences grew during the George W. Bush presidency, and nationalism has since become associated with support for Republican politicians, particularly those who champion far-right ideologies (Huddy and Del Ponte, 2021). There are various forms of nationalism, but generally, nationalism entails anti-immigrant sentiment, rejection of transnational organizations and pacts, and desire to uphold old national traditions (Gusterson, 2017). One form of U.S. nationalism is civic nationalism, which reflects beliefs that the U.S. is superior to other nations and should dominate over them (Kosterman and Feshbach, 1989). In recent U.S. elections, nationalism was associated with endorsing Trump over more moderate candidates in the 2016 Republican primary and voting for Trump over Clinton in the general election (Bonikowski et al., 2021). Support for Trump was also related to different forms of nationalism, such as Christian nationalism (Whitehead et al., 2018), gendered nationalism (Deckman and Cassese, 2021), and ethnonationalism (Thompson, 2021).

In addition to racism and nationalism, sexism has played a significant role in shaping U.S. voter preferences and candidate success. According to ambivalent sexism theory, sexism encompasses both hostile and benevolent attitudes toward women (Glick and Fiske, 1996). Hostile sexism refers to antipathy toward women based on beliefs that women should be subordinate to men. Benevolent sexism idealizes women as pure and caring, but also portrays them as weak and needing male protection. Though benevolent sexism includes positive sentiments, both types of sexism portray women as an inferior gender. Sexism—-particularly hostile sexism—-is a critical hindrance to female politicians (Lawless, 2009) and its effects also extend to evaluations of male candidates based on their stances on gender-relate issues. During U.S. elections, sexism was associated with support for Mitt Romney over Obama in 2012 (Simas and Bumgardner, 2017) and Trump over Clinton in 2016 (Knuckey, 2019; Schaffner et al., 2018; Bock et al., 2017; Glick, 2019). Hostile sexism also predicted intention to vote for Trump over all 2020 Democratic presidential candidates, including eventual nominee Joe Biden (Franks, 2021).

Prejudice is often generalized, such that people who devalue one marginalized group also tend to devalue other marginalized groups, and this shared variance of prejudice toward multiple groups correlated with basic personality traits (Akrami et al., 2011; Bergh et al., 2016). This is true for the prejudices examined in our study; generally, those who endorse racism also endorse sexism and nationalism, and vice versa (Adorno et al., 1950; McFarland, 2010; Pratto and Pitpitan, 2008). Given the interrelated nature of these prejudices, understanding the unique associations of each factor requires examining them in conjunction. Including these prejudices in one model yields the independent contribution of each prejudice controlling for the others, which accounts for their shared associations (VanderWeele and Vansteelandt, 2014). Using this kind of comprehensive model with multiple predictors also avoids the “single factor fallacy,” which can arise when relying on one factor to explain a large amount of variance in a complex outcome variable (Pettigrew and Hewstone, 2017; Baron and Kenny, 1986).

A few studies have investigated the joint effects of multiple prejudices on election outcomes, with mixed findings. When examined together, anti-Black racism was associated with negative evaluation of Barack Obama and positive evaluation of Sarah Palin, but sexism was not related to evaluations of the candidates in the 2008 U.S. presidential election (Dwyer et al., 2009). In 2016, some research found that supporting Trump over Clinton was more strongly associated with racism than sexism (Shook et al., 2020; Thompson, 2021), whereas other studies indicated that both prejudices were equally strong predictors (Schaffner et al., 2018; Knuckey, 2019; Buyuker et al., 2021). Few studies have examined the role of nationalism alongside other prejudices. Whitehead et al. (2018) found that Christian nationalism, but not racism or sexism indices, significantly predicted voting for Trump over Clinton in 2016, whereas another study found that civic nationalism was a weaker predictor of Trump support than racism and sexism (Shook et al., 2020). Thus, there is a lack of consensus about the possible relative effects of these prejudices in the past few U.S. presidential elections. Likewise, the motives behind the role of prejudice in political attitudes and behaviors warrants further investigation.

1.2 The dual-process motivational model

Duckitt (2001) dual-process motivational (DPM) model provides a framework for understanding the relationship between prejudice and political behavior. The DPM model is borne from a long line of social science research indicating that sociopolitical ideologies largely consist of two related but distinct dimensions (see Duckitt and Sibley, 2009 for summary). One dimension reflects preference for hierarchy over equality; the other reflects preference for authority and tradition over personal freedom and progress. These dimensions are reliably captured by SDO and RWA, respectively.

Although modestly related, SDO and RWA arise from different predispositions and social worldviews, and they thus reflect different motives (Duckitt, 2001; Osborne et al., 2023). SDO is associated with tough-mindedness and the belief that the world is a “competitive jungle” in which the weak lose and strong win. The primary motivational goal activated by SDO is domination (i.e., securing power over others; Osborne et al., 2023). On the other hand, RWA is associated with social conformity and a dangerous worldview, which classifies the world as inherently unpredictable and threatening. The primary goal induced by RWA is security (i.e., maintaining social order and stability; Osborne et al., 2023). Both ideologies predict prejudice and political outcomes, but for different reasons consistent with their primary goals (Van Assche et al., 2019; Duckitt and Sibley, 2010; Wedell and Bravo, 2022).

SDO is linked to prejudice against groups considered low in power or status—-to justify intergroup superiority—-and those threatening existing social hierarchies—-to maintain unequal power relations. People high in SDO tend to be biased against ethnic minority groups, particularly those viewed as threats to the economic resources of ethnic majority groups (Sidanius and Pratto, 2001; Duckitt and Sibley, 2010; Thomsen et al., 2008; Craig and Richeson, 2014). This bias extends to low-power or economically threatening nations, as SDO is associated with desires for global dominance (Osborne et al., 2017). High SDO is also strongly associated with hostile sexism, which reflects a desire for male dominance over women (Sibley et al., 2007). RWA is associated with prejudice against groups perceived to threaten national security, order, and tradition. RWA is also related to prejudice toward ethnic minority groups, especially those framed as dangerous, criminal, or incompatible with mainstream majority group culture (Cohrs and Asbrock, 2009; Craig and Richeson, 2014). On the global stage, RWA is associated with desires to protect one's country from physical and cultural threats posed by foreign nations (Duckitt and Sibley, 2010). People high in RWA generally also endorse sexism, especially benevolent sexism, which is grounded in adherence to traditional gender roles (Sibley et al., 2007).

Along the same lines, both SDO and RWA predict support for conservative leaders, especially those on the far-right of the political spectrum (Cornelis and Van Hiel, 2015; Pettigrew, 2017; Aichholzer and Zandonella, 2016). In general, SDO is associated with support for economically conservative politicians (Ho et al., 2015; Harnish et al., 2018). High-SDO individuals may be drawn to leaders who oppose race- and gender-based wealth redistribution initiatives (Ho et al., 2015; Fraser et al., 2015). They may also be attracted to politicians who champion displays of U.S. dominance through use of military aggression (Henry et al., 2005; Ho et al., 2015). On the other hand, RWA is most consistently associated with support for politicians who promote social conservatism (Perry and Sibley, 2013; Harnish et al., 2018). Those high in RWA may favor politicians who oppose perceived deviations from “traditional family values”, like abortion rights and same sex marriage (Duriez and Van Hiel, 2002; Duriez et al., 2005); embrace “tough-on-crime” policies (Duckitt and Sibley, 2010); and disapprove of foreign cultural influences (Craig and Richeson, 2014; Peitz et al., 2018).

Recent applications of the DPM model have illuminated directional relationships between SDO, RWA, prejudice, and politics. Cornelis and Van Hiel (2015) argued that the DPM model ideologies and prejudice are not alternative or competing predictors of right-wing politics. Instead, SDO and RWA are underlying motivations of prejudice, which encourage right-wing political preferences. Indeed, in a sample of Dutch voters, the effects of SDO and RWA on right-wing voting were mediated by ethnic prejudice (Cornelis and Van Hiel, 2015). Van Assche et al. (2019) replicated this mediational model in the U.S. and United Kingdom. In one study, modern racism mediated the relationships of both SDO and RWA with intentions to vote for Trump; in another study, anti-immigrant attitudes mediated the relationships of SDO and RWA with support for Trump's ideas. In a cross-lagged panel design, higher SDO and RWA were associated with greater anti-immigrant prejudice over time, which in turn was longitudinally related to support for a British right-wing political party.

This research indicates that prejudice, at least in part, accounts for the positive associations between SDO and RWA and preferences for right-wing politicians. That is, higher SDO and RWA are associated with greater prejudice toward groups deemed threatening to related ideological values and goals; in turn, this prejudice is positively associated with support for politicians whose stances appear to mitigate these threats. Prior applications of this model focused only on right-wing support and did not examine the effects of multiple prejudices in conjunction. Thus, we used this validated mediational model to examine the unique effects of racism, nationalism, and sexism on voters' evaluations of each presidential candidate and vote choice during the 2020 U.S. presidential election.

1.3 The present research

The first aim of this study was to conceptually replicate and extend previous examinations of the role of prejudice in U.S. presidential elections (Shook et al., 2020). Using a large national sample of U.S. adults, we assessed the extent to which modern racism, sexism (hostile and benevolent), and U.S. nationalism uniquely prospectively predicted evaluations of presidential candidates (Biden and Trump) and voting behavior in the 2020 U.S. presidential election. We expected to replicate previous results and find that modern racism would be associated with election outcomes more consistently than nationalism and sexism.

Second, we aimed to replicate and extend the mediational work (Cornelis and Van Hiel, 2015; Van Assche et al., 2019) that clarifies the potential motives underlying the link between prejudice and political decision making. We examined the mediational roles of racism, nationalism, and sexism in a unified model and predicted that the effects of SDO and RWA on election outcomes would be mediated through these prejudices.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Participants and procedure

Three waves of data were utilized from a larger 29-wave longitudinal study about social and political attitudes, health, and wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic. This project was approved by the University of Connecticut IRB (Protocol #L20-0018). Sample size for the longitudinal study was based on Monte Carlo simulations (N = 10,000) of the most conservative models for the original data analysis plan. A minimum of 500 participants were necessary to provide sufficient power (>95%) to detect anticipated effects (β = 0.15–0.20) assuming α = 0.05. A panel of 1,181 U.S. adult residents were initially recruited through the panel provider Qualtrics to account for missing or unusable data.

All participants provided electronic consent before completing online surveys administered on a weekly to monthly basis. The first wave (N = 1,181) included in this project was collected between May 11th and 17th, 2020. Participants provided their demographics and completed measures of social dominance orientation (SDO) and right-wing authoritarianism (RWA). The second wave (N = 777) utilized in this study was collected just before the 2020 U.S. presidential election, between October 26th and November 2nd, 2020. Participants completed measures of modern racism, U.S. nationalism, and sexism toward women (hostile and benevolent). They also evaluated Joe Biden and Donald Trump on several traits. The third wave (N = 742) of data for this project was collected after the 2020 U.S. presidential election, between November 9th and 16th, 2020. Participants were asked to indicate whether they voted and if so, whether they voted for Joe Biden, Donald Trump, or another presidential candidate. After completing each online survey, participants were compensated in an amount established by the panel provider.

Across the three waves of data used for this project, 625 participants completed all three surveys. Two participants were excluded from analyses due to problematic response patterns (e.g., gibberish open-ended responses, straight line responses to close-ended measures). Out of the participants who responded to all waves, some did not answer any items on the measures of SDO (0.2%), RWA (0.6%), modern racism (1.8%), U.S. nationalism (2.2%), or sexism toward women (2.4%); did not provide answers to any candidate evaluation items for Biden (1.4%) or Trump (1.3%); or did not indicate their presidential vote choice (8.0%). As our main research questions concerned factors associated with voting for Biden or Trump specifically, we excluded participants who voted for other candidates (3.4%). Missing value analyses yielded a significant Little's MCAR test statistic, indicating that data were not missing at random (p = 0.017). As such, participants with incomplete data were excluded from analyses. The final sample consisted of 531 respondents. This sample size met several requirements necessary for sufficient power to perform the statistical modeling used to address our research questions (see Wolf et al., 2013, for a discussion).

Comparisons of included and excluded participants were conducted to identify any group differences. Compared to excluded participants, participants comprising the final sample used in our analyses were older, completed more years of education, reported a greater annual family income, and were more likely to be White (ps < 0.01). Those who were included in our analyses scored lower on SDO (p = 0.013), modern racism (p = 0.003), U.S. nationalism (p = 0.047), and hostile sexism (p = 0.013) compared to excluded participants. Included participants also evaluated Joe Biden more positively (p = 0.027) than excluded participants. Participants who were included and excluded from analyses did not differ along any other demographic factors (i.e., gender and political orientation; ps > 0.10) nor measures of interest (i.e., RWA, benevolent sexism, evaluation of Donald Trump, voting behavior; ps > 0.114).

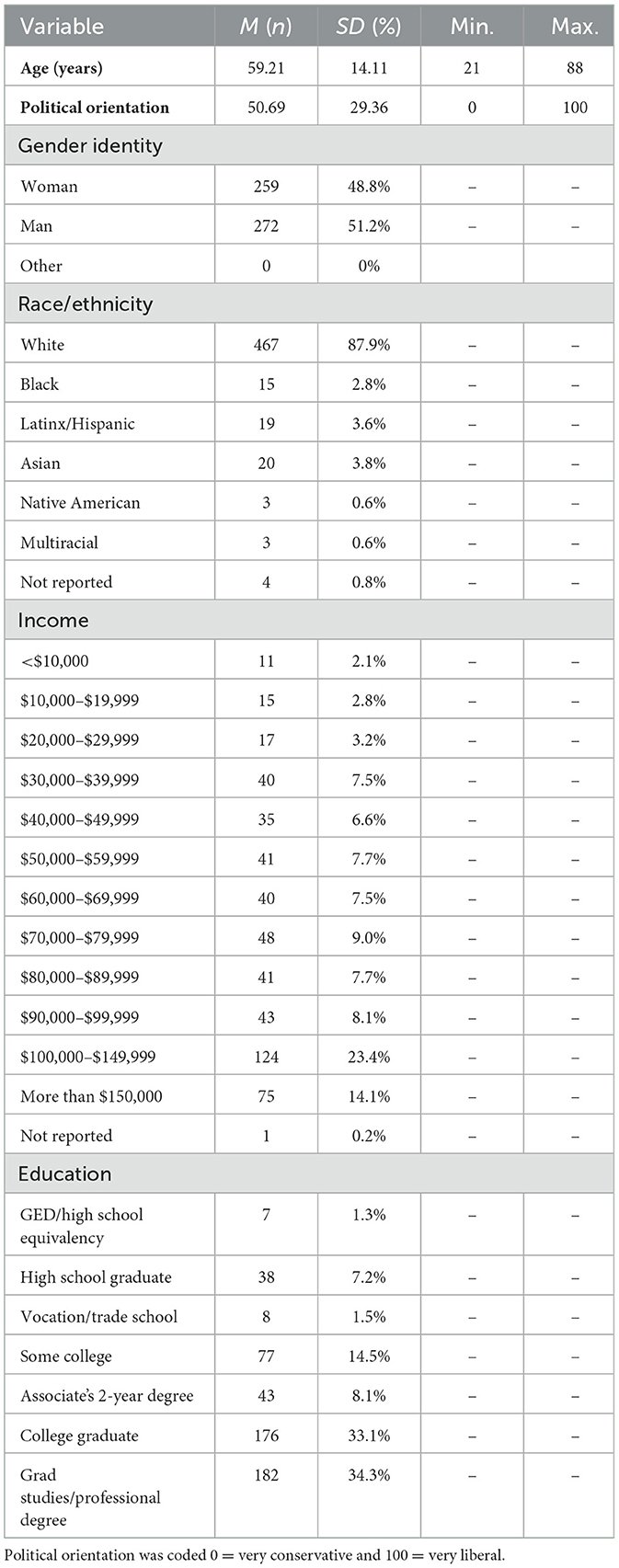

Table 1 depicts a full description of the sample. The final sample consisted of 48.8% women, was aged 21–88 years (M = 59.21, SD = 14.11), and was 87.9% White. Average political orientation of the sample was around the midpoint of the 0 (very conservative) to 100 (very liberal) scale (M = 50.69, SD = 29.24). Median education level was college graduate and median annual family income was $80,000–$89,999.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Demographics

Participants provided their age, gender identity, race/ethnicity, education level, and annual family income. Participants also indicated their political orientation, which was measured on a scale from 0 (very conservative) to 100 (very liberal).

2.2.2 Social dominance orientation

To assess the extent to which participants endorsed social hierarchies, we used the well-validated four-item Short Social Dominance Orientation (SSDO) scale (Pratto et al., 2013). Participants rated each item (e.g., “We should not push for group equality”) on a scale from 1 (extremely oppose) to 10 (extremely favor). Mean scores were calculated with higher values indicating greater endorsement of SDO (α = 0.79).

2.2.3 Right-wing authoritarianism

A short six-item version of Altemeyer (1981) Right-Wing Authoritarianism scale (Bizumic and Duckitt, 2018) was used to measure authoritarian attitudes. Participants indicated the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with each item (e.g., “What our country needs most is discipline, with everyone following our leaders in unity”) on a scale from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 9 (very strongly agree). Mean scores were calculated with higher values indicating greater endorsement of RWA (α = 0.68).

2.2.4 Modern racism

The original Modern Racism Scale (McConahay, 1986) consists of seven items. One item (“Black people have more influence upon school desegregation plans than they ought to have”) is less applicable today than it was when the scale was first constructed. We removed this item and administered a six-item scale assessing racism toward Black Americans. Participants rated each item (e.g., “Black people are getting too demanding in their push for equal rights”) on a scale from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). Mean scores were calculated such that higher values indicated greater prejudice toward Black Americans (α = 0.90).

2.2.5 Patriotism/nationalism questionnaire

The eight-item nationalism subscale from the Patriotism/Nationalism Questionnaire (Kosterman and Feshbach, 1989) was used to measure U.S. nationalism. Participants rated each item (e.g., “Other countries should try to make their government as much like ours as possible”) on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Mean scores were calculated with higher values indicating greater endorsement of nationalistic attitudes (α = 0.88).

2.2.6 Ambivalent sexism inventory

We used a short version of the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (Glick and Fiske, 1996), which has good psychometric properties consistent with those of the original scale (Rollero et al., 2014). This assessment consists of 12 items and has two subscales: hostile and benevolent sexism toward women. Six items assess hostile sexism (e.g., “Women seek to gain power by getting control over men”) and six items assess benevolent sexism (e.g., “Many women have a quality of purity that few men possess”). Participants rated their agreement with each statement on a scale from 1 (disagree strongly) to 6 (agree strongly). Mean scores were calculated for each subscale. Higher values indicated greater benevolent (α = 0.84) and hostile (α = 0.90) sexism.

2.2.7 Presidential candidate evaluations

Participants rated Joe Biden and Donald Trump on several dimensions. Participants indicated their general trust or distrust of each candidate on a scale of 1 (completely distrust) to 5 (completely trust). Participants also rated how likable, competent, qualified, intelligent, and knowledgeable they found each candidate to be on a scale from 0 to 100, where higher numbers meant more of the trait. All six items evaluating Joe Biden (rs: 0.79–0.97, ps < 0.001; α = 0.95) and Donald Trump (rs: 0.86–0.98, ps < 0.001; α = 0.95) were strongly correlated and created reliable indices. We computed a composite evaluation score for each candidate by standardizing the items and averaging them together. Higher values on this composite scale indicate a more positive evaluation of the candidate.

2.2.8 Voting behavior

During the final survey wave administered after the 2020 U.S. presidential election, participants were asked if they voted (yes or no). Those who reported casting a vote in the election were then asked to indicate for whom they voted (Trump/Pence, Biden/Harris, or Other). Presidential vote choice was represented as a binary variable, where 1 indicated voting for Trump/Pence and 2 indicated voting for Biden/Harris.

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive statistics

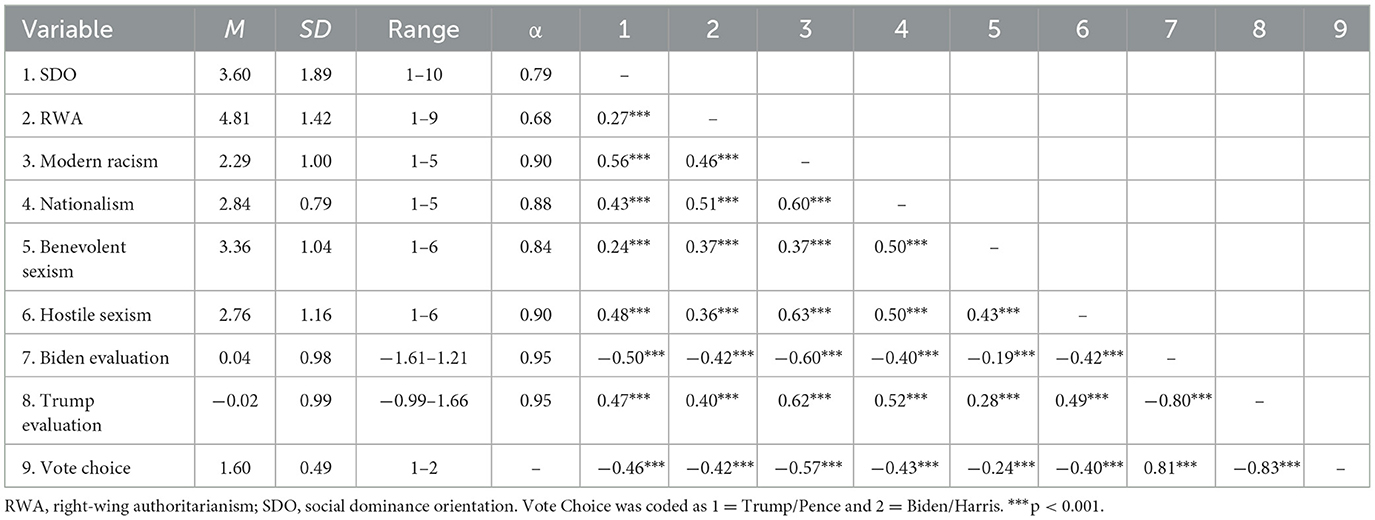

Means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations for study variables of interest are displayed in Table 2. The mean of the binary vote choice variable (1 = Trump/Pence and 2 = Biden/Harris) was significantly different than its theoretical mean of 1.5 (t530 = 4.55, p < 0.001), indicating that a greater proportion of our sample voted for Biden/Harris (59.7%) than Trump/Pence (40.3%). However, a paired-samples t-test indicated that on average, evaluations of Biden and Trump were not significantly different from each other (t530 = 0.74, p = 0.46). Evaluations of the two candidates were significantly inversely correlated. As expected, vote choice was significantly negatively associated with Trump evaluation and significantly positively associated with Biden evaluation, indicating that more positive evaluations of the candidates were correlated with voting for them in the presidential election. More positive evaluation of Trump, less positive evaluation of Biden, and voting for Trump/Pence were significantly correlated with higher scores on measures of RWA, SDO, modern racism, U.S. nationalism, hostile sexism, and benevolent sexism. RWA, SDO, modern racism, U.S. nationalism, hostile sexism, and benevolent sexism were all significantly positively correlated with one another.

Correlation coefficients between demographic factors and outcome variables were also computed to identify potential covariates. Political orientation and education level were significantly correlated with all three outcome variables. Participants with a more liberal political orientation evaluated Trump less positively (r = −0.64, p < 0.001), Biden more positively (r = 0.65, p < 0.001), and were more likely to vote for Biden/Harris than Trump/Pence (r = 0.64, p < 0.001). Similarly, higher level of education was associated with less positive Trump evaluation (r = −0.16, p < 0.001), more positive Biden evaluation (r =0.12, p = 0.01), and greater likelihood of voting for Biden/Harris in the 2020 presidential election (r = 0.12, p = 0.007). None of the other demographic variables were correlated with candidate evaluations nor vote choice (ps > 0.105).

3.2 Structural equation models

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to assess direct associations between RWA, SDO, and the outcome variables (candidate evaluations and vote choice), as well as indirect effects through attitudes reflecting modern racism, U.S. nationalism, benevolent sexism, and hostile sexism. SDO and RWA were measured at wave 1; racism, nationalism, sexism, and candidate evaluations were measured at wave 2; and vote choice was measured at wave 3. Item-level indicators were used to specify latent variables representing SDO, RWA, modern racism, U.S. nationalism, benevolent sexism, hostile sexism, and evaluations of Biden and Trump. Model fit was evaluated using standard metrics; an acceptable fit was indicated with comparative fit index (CFI) >0.90 and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.08. Some participants in the final sample missed one or more items comprising the latent measures of SDO (2.1%), RWA (0.2%), modern racism (0.2%), U.S. nationalism (0.6%), sexism (0.8%), Biden evaluation (1.1%), or Trump evaluation (1.1%). Little's MCAR test statistic assessing this item-level missingness was not significant (p =0.054), indicating that these items were missed at random. We used multiple imputation to address missed items. Analyses were performed in IBM SPSS Amos 29.

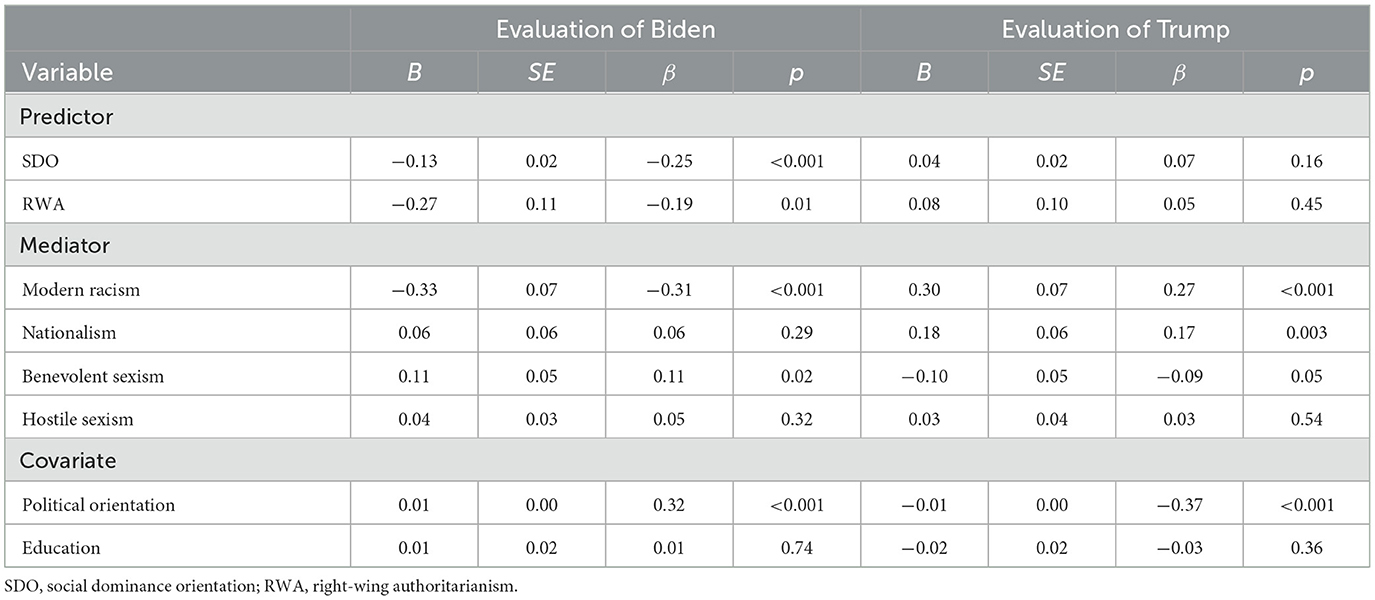

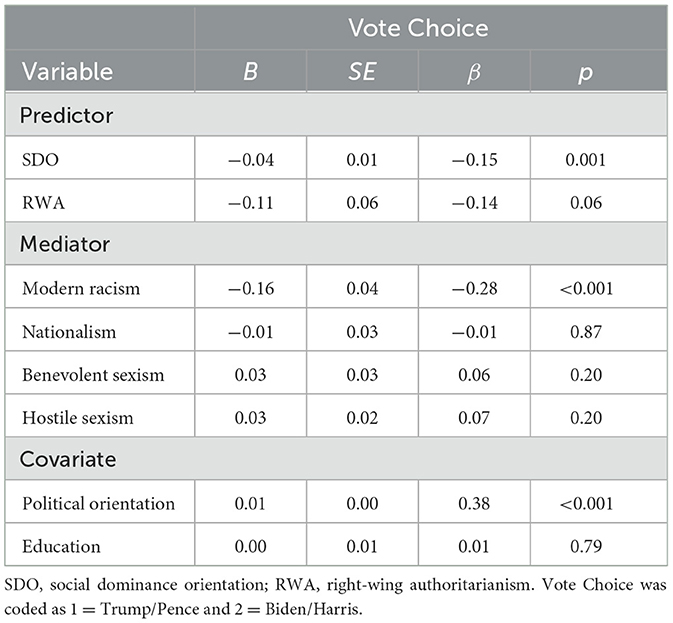

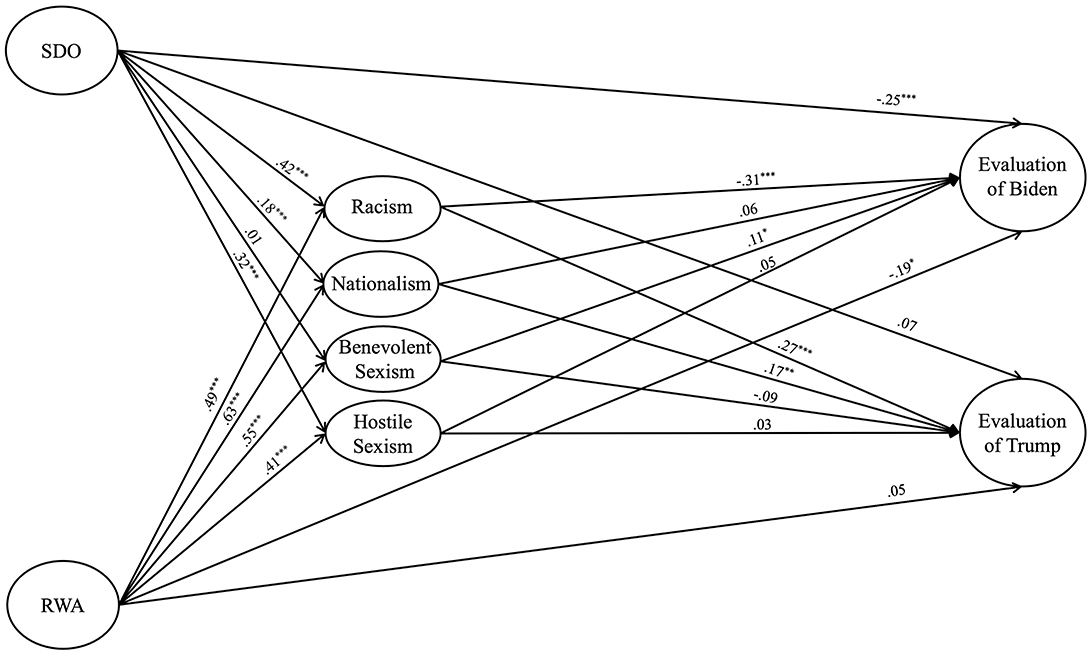

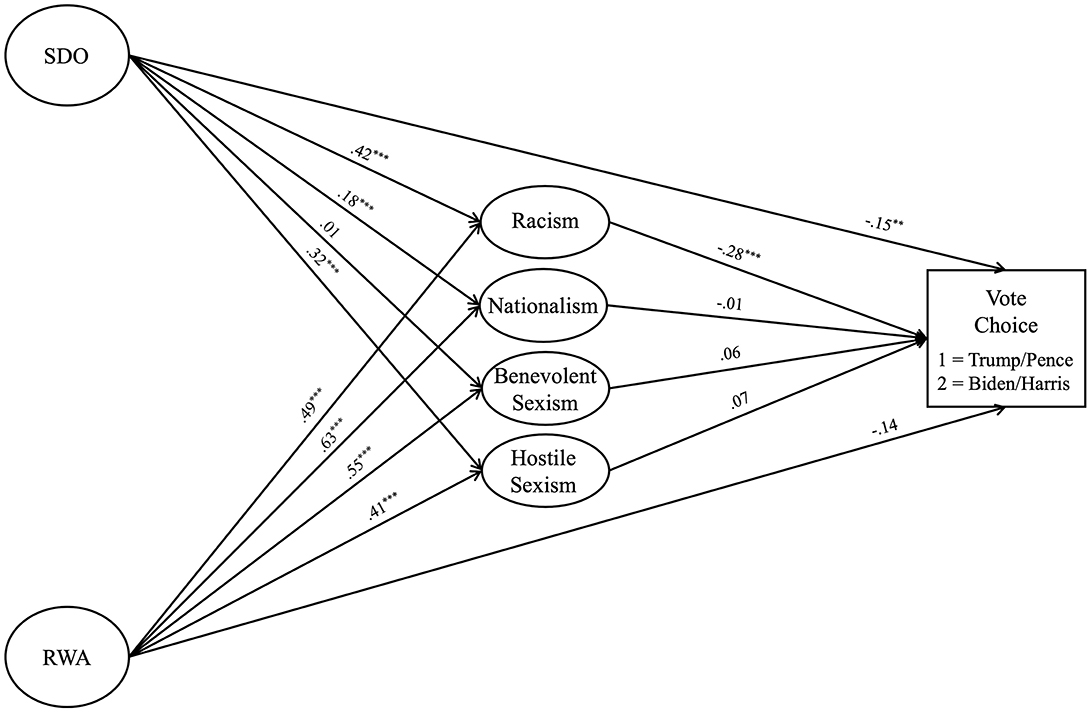

Two SEMs were created using different outcome variables. Model 1 (Figure 1) included evaluations of the presidential candidates as outcomes and Model 2 (Figure 2) included vote choice as the outcome variable. In both models, SDO and RWA were prospectively associated with outcomes via direct paths, as well as indirect paths through racism, U.S. nationalism, benevolent sexism, and hostile sexism. As both political orientation and education level correlated significantly with candidate evaluations and vote choice, they were included as covariates. Adding these covariances did not change the magnitudes or signs of the paths in either model. Given significant correlations (see Table 2), error terms were allowed to covary between SDO and RWA. Error terms were also allowed to covary among all the mediators (modern racism, U.S. nationalism, benevolent sexism, and hostile sexism). In Model 1, the error terms of candidate evaluations were allowed to covary. Modification indices suggested that, for both models, the demographic covariates (i.e., political orientation and education level) should also covary with SDO and RWA. Political orientation was significantly negatively correlated with RWA (r = −0.58, p < 0.001) and SDO (r = −0.54, p < 0.001), and education was significantly negatively correlated with RWA (r = −0.20, p < 0.001) but not significantly associated with SDO (r = 0.08, p = 0.05).

Figure 1. Model 1 depicting the relationship between SDO, RWA, and candidate evaluations mediated through modern racism, U.S. nationalism, benevolent sexism, and hostile sexism. Numbers represent standardized regression coefficients. Political orientation and education were included as covariates in the model. Error terms between SDO and RWA, among the mediators, and between the outcome variables were allowed to covary. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Figure 2. Model 2 depicting the relationship between SDO, RWA, and vote choice mediated through modern racism, U.S. nationalism, benevolent sexism, and hostile sexism. Note. Numbers represent standardized regression coefficients. Political orientation and education were included as covariates in the model. Error terms between SDO and RWA, as well as among the mediators, were allowed to covary. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01.

Both models yielded acceptable model fit: Model 1 (χ2/df = 2.99, RMSEA [90% CI] = 0.061 [0.059, 0.064], CFI = 0.904) and Model 2 (χ2/df = 3.18, RMSEA [90% CI] = 0.064 [0.061, 0.067], CFI =0.866). Regarding paths from SDO and RWA to the mediators in both models, SDO was significantly positively associated with modern racism (B = 0.20, SE = 0.02, β = 0.42), U.S. nationalism (B = 0.09, SE = 0.02, β = 0.18), and hostile sexism (B = 0.19, SE = 0.03, β = 0.32; ps < 0.001). SDO was not significantly associated with benevolent sexism (B = 0.01, SE = 0.03, β = 0.01, p = 0.82). RWA was significantly positively associated with modern racism (B = 0.66, SE = 0.12, β = 0.49), U.S. nationalism (B = 0.86, SE = 0.15, β =0.63), hostile sexism (B = 0.69, SE = 0.14, β = 0.41; ps < 0.001), and benevolent sexism (B = 0.78, SE = 0.15, β = 0.55, p < 0.001). Tables 3, 4 display the standardized estimates, unstandardized estimates, and standard errors for all direct paths to the outcome variables in Models 1 and 2, respectively.

In Model 1, higher SDO and higher RWA were both significantly negatively related to evaluation of Biden, but neither the direct path from SDO nor RWA to evaluation of Trump was significant. Greater endorsement of modern racism was significantly negatively related to evaluation of Biden and positively related to evaluation of Trump. More positive Trump evaluation was also associated with higher nationalism, but nationalism was not significantly related to evaluation of Biden. Finally, benevolent sexism significantly was positively related to evaluation of Biden; however, the correlational relationship between benevolent sexism and Biden evaluation (see Table 2) was negative, suggesting the positive relationship between the two variables in Model 1 was the result of a suppression effect (Darlington, 1968).

Specific indirect effects were calculated via user-defined estimands to assess the associations between both SDO and RWA on candidate evaluations through each of the four mediators. Modern racism significantly mediated the negative relationship between SDO and evaluation of Biden (B [95% CI] = −0.065 [−0.107, −0.029], p =0.01), as well as the positive relationship between SDO and evaluation of Trump (B [95% CI] =0.059 [.023,0.113], p =0.006). Modern racism also significantly mediated the negative relationship between RWA and evaluation of Biden (B [95% CI] = −0.217 [−0.485, −0.081], p =0.009) and positive relationship between RWA and evaluation of Trump (B [95% CI] =0.197 [.063,0.442], p =0.012). Nationalism also significantly mediated the positive relationships between both SDO (B [95% CI] =0.016 [.003,0.038], p =0.024) and RWA (B [95% CI] =0.158 [.039,0.341], p =0.028) and evaluation of Trump. Nationalism was not a significant mediator for evaluation of Biden. Finally, the indirect effect of RWA through benevolent sexism was significant and positive on evaluation of Biden (B [95% CI] =0.087 [.023,0.238], p =0.02); however, as was the case with the direct relationship between benevolent sexism and Biden evaluation, this positive mediational relationship was likely due to a suppression effect. Indeed, a simple mediation analysis performed using the Hayes PROCESS macro indicated that benevolent sexism did not mediate the relationship between RWA and Biden evaluation (B [95% CI] = −0.009 [−0.032,0.012]) when tested without modern racism, nationalism, or hostile sexism.

In Model 2, higher SDO and higher modern racism were significantly associated with voting for Trump/Pence over Biden/Harris. RWA, U.S. nationalism, benevolent sexism, and hostile sexism were not significantly associated with vote choice. The relationship between SDO and vote choice was mediated by modern racism (B [95% CI] = −0.032 [−0.058, −0.015], p =0.007), as was the relationship between RWA and vote choice (B [95% CI] = −0.107 [−0.212, −0.038], p = 0.018).

4 Discussion

4.1 Unique effects of racism, nationalism, and sexism

The first aim of this study was to compare the effects of racism, nationalism, and sexism on U.S. presidential election outcomes. Shook et al. (2020) identified modern racism against Black Americans as the most consistent predictor of 2016 election outcomes, and we replicated this finding in the 2020 election. All the prejudices were significantly correlated with the outcome variables, but modern racism was the only prejudice that significantly predicted all outcomes in our structural equation models. Lower racism was associated with a more favorable evaluation of Biden, while higher racism was associated with a more favorable evaluation of Trump. Racism was the only prejudice associated with vote choice in our models, prospectively predicting greater likelihood of voting for Trump over Biden. These associations were significant independent of SDO, RWA, sexism, nationalism, education level, and political orientation. Prior to the 2020 election, the police killing of George Floyd inspired nationwide protests calling for racial justice, which attracted record breaking numbers of attendees (Buchanan et al., 2020). Our results suggest that racial attitudes remained salient at the polls.

U.S. nationalism was the only other prejudice independently associated with an election outcome in our models. Unlike racism, it did not account for evaluation of Biden nor vote choice, but it was uniquely associated with more positive evaluation of Trump. Trump's anti-globalist doctrine (Feffer, 2017) and “America First” slogan may have garnered favor from proponents of U.S. superiority. However, in our sample, this civic nationalism was ultimately not uniquely related to voting behavior.

Of the three prejudices, sexism had the least influence in our models. In bivariate correlations, greater hostile sexism was moderately related to more negative evaluation of Biden, more positive evaluation of Trump, and voting for Trump over Biden. The same patterns emerged for benevolent sexism. However, in our structural equation models, hostile sexism was not significantly associated with any outcome variables. In Model 1, there was a positive relationship between benevolent sexism and Biden evaluation, but, as these variables shared a negative correlation, this finding was most likely a suppression effect (Darlington, 1968). Otherwise, when examined in conjunction with other factors, sexism was not a unique determinant of voter attitudes or behaviors. More research is needed to understand the relative roles of racism and sexism in political preferences, but some work suggests that the lesser impact of sexism may be related to differences among American women voters. While women of color have generally voted for Democrats and progressive policies, White women have predominately voted for Republicans since gaining suffrage (Junn, 2017). White women's motives to maintain their racial supremacy may increase the relative impact of race- compared to gender-related attitudes on political preferences and behavior (Frasure-Yokley, 2018; Junn, 2017).

Our findings closely mirrored other research identifying anti-Black racism as a stronger unique predictor of election outcomes than sexism and nationalism (Dwyer et al., 2009; Shook et al., 2020; Thompson, 2021). However, they deviated from research identifying Christian nationalism, but not racism or sexism, as an independent predictor of voting behavior (Whitehead et al., 2018) as well as research finding racism and sexism to be equally strong independent predictors of election outcomes (Schaffner et al., 2018; Knuckey, 2019; Buyuker et al., 2021). There are several possible explanations for these mixed findings, including study design and operationalization differences. For one, our measure of nationalism captures beliefs in U.S. superiority and desires for U.S. dominance over other nations. Other research has focused heavily on exclusionary forms of nationalism, like Christian nationalism and ethnonationalism (Whitehead et al., 2018; Thompson, 2021), which entail beliefs that “true Americans” are White U.S.-born Christians. These forms of nationalism are based on White supremacist ideals, and studies linking them to election outcomes are congruent with our emphasis on the role of racism. Moreover, many studies relied on retrospective analyses of national opinion polls, which did not include validated measures of each concept of interest. For example, Whitehead et al. (2018) had to approximate anti-Black racism using two items assessing beliefs about police brutality toward Black Americans. Additionally, though comparing multiple prejudices, some studies were designed to evidence the effect of one prejudice of interest, treating the other prejudices as controls. Our study design allowed us to assess all prejudices using validated scales, all of which showed good internal consistency. We also used the same scales as Shook et al. (2020) did to study 2016 election outcomes, allowing a direct replication of their work.

4.2 A DPM model mediational framework of prejudice and politics

In addition to examining the unique effects of several prejudices, we aimed to clarify motives underlying these prejudices and associated prospective political outcomes. We replicated research illustrating a mediational relationship between sociopolitical ideology, prejudice, and political preferences (Cornelis and Van Hiel, 2015; Van Assche et al., 2019). Prejudice served as a mediator between SDO, RWA, and all three election outcomes, suggesting that voter prejudice was underlain by desires to maintain social dominance and social order.

Modern racism mediated all the relationships in both models. Higher racism mediated the relationships of high SDO and RWA with more positive Trump evaluation and greater likelihood of voting for Trump over Biden. Much of Trump's race-related rhetoric was likely to motivate support from voters high in SDO and RWA. He claimed that affirmative action policies advantaged Black Americans at the expense of White Americans, which may have elicited intergroup competition motives (Sides et al., 2019; Ho et al., 2015). He also grossly exaggerated rates of violent crimes committed by Black Americans, possibly evoking security motives (Sides et al., 2019; Duckitt and Sibley, 2010). Thus, our mediational models suggests that pro-Trump attitudes and voting for Trump were, in part, motivated by desires to uphold White supremacy and maintain a law-and-order system that prioritized White safety and privilege. These findings align with prior research (Cornelis and Van Hiel, 2015; Van Assche et al., 2019), which has predominantly examined these relationships in the context of far-right support. However, our study suggests that these models can also explain support for Democratic candidates. Inversely to relationships with Trump support, lower SDO and RWA predicted more positive Biden evaluation and voting for Biden through lower racism. While racial animus may have motivated endorsement of Trump, in our sample, desires for racial equality (indicated by low SDO) and social progress (indicated by low RWA) were equally strong correlates of Biden support. A large portion of the electorate may be drawn to candidates who promote justice for Black Americans.

Nationalism was the only other significant mediator; in Model 1, higher SDO and RWA were indirectly associated with more positive Trump evaluation through higher nationalism. Trump's emphasis on U.S. economic and military prowess (Jaffe and Johnson, 2017) may have appealed to high–SDO voters' desires for U.S. global dominance (Ho et al., 2015), and his devaluation of outside cultural influence (Lind, 2015) may have aligned with RWA-related social cohesion motives (Duckitt and Sibley, 2010).

SDO and RWA also exerted direct effects in our models. In Model 1, lower SDO and RWA were both directly associated with more positive Biden evaluation but had no direct effects on evaluation of Trump. In Model 2, higher SDO was directly associated with greater likelihood of voting for Trump, but RWA exerted no direct effect. DPM literature outlines instances in which SDO and RWA differentially predict prejudice and politics; however, we are cautious not to overinterpret full and partial mediations in our models (Hayes, 2009). More work is needed to understand whether SDO and RWA played different roles in voter attitudes and behaviors during recent U.S. presidential elections.

4.3 Limitations and future directions

The results of this study must be taken in light of certain study limitations. Our sample was notably devoid of racial, ethnic, and gender diversity and thus not representative of the U.S. population. Our findings may most accurately represent White, heterosexual, cisgender Americans, and may not generalize to the electorate at large. Although our data were longitudinal, such that our predictors were collected prior to our mediators and outcomes, and research has offered support for a causal relationship between the variables in our models (Van Assche et al., 2019), it is crucial to note that our study design was correlational and does not allow for causal interpretation. We also relied exclusively on self-report measures, which introduces concerns of exaggerated variable associations due to common method variance. This topic would thus benefit from research using representative samples of U.S. adults, longitudinal or experimental study designs, and behavioral or implicit measurement methods.

Furthermore, while we employed comprehensive models that included multiple prejudices, we did not examine ingroup attitudes, which may also play a significant role in shaping political outcomes. Specifically, joint effects between ingroup identification and outgroup bias could amplify the relationships in our models. Research suggests that ingroup identification is associated with SDO and RWA, and stronger ingroup identification may lead to increased political polarization and bias (Vargas-Salfate et al., 2020; Ehrlich and Gramzow, 2015; Levin and Sidanius, 1999). Thus, future studies should examine how ethnic or national identification interacts with the variables we investigated, as this may provide a more nuanced understanding of the mechanisms and societal contexts that reinforce prejudice and impact political behaviors.

Our study also did not assess politically relevant prejudices like xenophobia, Islamophobia, homophobia, or transphobia. Xenophobia may be particularly important in this context, as one study identified it as the strongest predictor of Trump support in 2016 and intended Trump support in 2020, independent of racial resentment, sexism, and White identity (Buyuker et al., 2021). Moreover, xenophobia is closely associated with modern racism and nationalism and may represent a confound in our study. Future research should thus include measures of xenophobia and may further examine opposition to specific migrant groups. Given strong associations between racial attitudes and U.S. presidential election outcomes, it is likely that White immigrants from majority Christian countries may elicit less opposition from right-wing ideologues than non-Christian migrants of color. Attitudes toward different migrant groups may also be differentially associated with SDO and RWA.

4.4 Practical implications and conclusion

This work highlights the enduring impact of anti-Black racism on U.S. politics. We find that the relationship between prejudice and politics is driven, in part, by desires to maintain existing social hierarchies and national norms. Notably, our research does not negate the detrimental effects of sexism and nationalism on U.S. politics. The relationship between prejudice and political preferences is likely to vary based on contextual factors, and the relative roles of different prejudices may shift over time. However, our work adds to research consistently linking anti-Black prejudice to political preferences across multiple U.S. elections featuring politicians with varying racial and gender backgrounds. According to recent public opinion polls, racial attitudes will remain particularly significant in the coming presidential election (Pew Research Center, 2024; Rhodes et al., 2024). As such, anti-Black racism warrants timely and effective intervention. Since prejudice is a systemic issue, racism would ideally be addressed at the systems level. Systemic actions could include revoking discriminatory policies, improving socioeconomic conditions for marginalized racial groups (Clark et al., 2022), and codifying racial equality into federal law. Many interventions to combat anti-Black racism can also be implemented at the individual, interpersonal, and community levels (Watson-Thompson et al., 2022). Research has also found that SDO and RWA can be reduced directly through intergroup contact (Shook et al., 2016; Dhont et al., 2014; Pettigrew et al., 2011), but this approach may be difficult to execute and places the onus of redressing systemic prejudice on marginalized groups. Advocates and policymakers may additionally consider SDO- and RWA-related motives when crafting interventions and framing political messaging. For example, dispelling myths that present the social and economic standing of Black and White Americans as zero-sum could attenuate dominance motives associated with SDO (Craig and Richeson, 2014), and emphasizing polyculturalism, rather than White supremacy, as the basis of U.S. culture could attenuate RWA-related motives to maintain national norms (Rios et al., 2018). Diminishing these motives could reduce prejudice which would catalyze a downstream effect on political behavior, ultimately contributing to a more just democracy.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://osf.io/rmukb.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of Connecticut Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AR: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization. FP: Writing – review & editing. NS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by a RAPID grant from the National Science Foundation under Award ID BCS-2027027 (PI Natalie Shook). The funding organization was not involved in designing the study, collecting and analyzing the data, or preparing the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abramowitz, A., and McCoy, J. (2019). United States: racial resentment, negative partisanship, and polarization in Trump's America. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 681, 137–156. doi: 10.1177/0002716218811309

Adorno, T., Frenkel-Brenswik, E., Levinson, D. J., and Sanford, R. N. (1950). The Authoritarian Personality. New York: Harper.

Aichholzer, J., and Zandonella, M. (2016). Psychological bases of support for radical right parties. Pers. Individ. Dif. 96, 185–190. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.02.072

Akrami, N., Ekehammar, B., and Bergh, R. (2011). Generalized prejudice: common and specific components. Psychol. Sci. 22, 57–59. doi: 10.1177/0956797610390384

Alamillo, R. (2019). Hispanics para Trump?: Denial of racism and hispanic support for Trump. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race 16, 457–487. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X19000328

Baron, R. M., and Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51, 1173. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

Bergh, R., Akrami, N., Sidanius, J., and Sibley, C. (2016). Is group membership necessary for understanding generalized prejudice? A re-evaluation of why prejudices are interrelated. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 111, 367–395. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000064

Bizumic, B., and Duckitt, J. (2018). Investigating right wing authoritarianism with a very short authoritarianism scale. J. Soc. Polit. Psychol. 6, 129–150. doi: 10.5964/jspp.v6i1.835

Bock, J., Byrd-Craven, J., and Burkley, M. (2017). The role of sexism in voting in the 2016 presidential election. Pers. Individ. Dif. 119, 189–193. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.07.026

Bonikowski, B., Feinstein, Y., and Bock, S. (2021). The partisan sorting of “America”: How nationalist cleavages shaped the 2016 US presidential election. Am. J. Sociol.127, 492–561. doi: 10.1086/717103

Bonikowski, B., Luo, Y., and Stuhler, O. (2022). Politics as usual? Measuring populism, nationalism, and authoritarianism in US presidential campaigns (1952–2020) with neural language models. Sociol. Methods Res. 51, 1721–1787. doi: 10.1177/00491241221122317

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2019). “Racists,” “Class Anxieties,” Hegemonic Racism, and Democracy in Trump's America. Social Currents 6, 14–31. doi: 10.1177/2329496518804558

Brownstein, R. (2019). “Why race is moving center stage for 2020,” in CNN. Available at: https://www.cnn.com/2019/09/17/politics/2020-candidates-voters-racism-sexism-attitudes/index.html (accessed August 5, 2024).

Buchanan, L., Bui, Q., and Patel, J. (2020). “Black Lives Matter may be the largest movement in U.S. history,” in The New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/07/03/us/george-floyd-protests-crowd-size.html (accessed August 10, 2024).

Buyuker, B., D'Urso, A. J., Filindra, A., and Kaplan, N. J. (2021). Race politics research and the American presidency: thinking about white attitudes, identities and vote choice in the Trump era and beyond. J. Race, Ethnicity Polit. 6, 600–641. doi: 10.1017/rep.2020.33

Clark, E. C., Cranston, E., Polin, T., Ndumbe-Eyoh, S., MacDonald, D., Betker, C., et al. (2022). Structural interventions that affect racial inequities and their impact on population health outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 22:2162. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-14603-w

Clayton, D. M., Moore, S. E., and Jones-Eversley, S. D. (2021). A Historical Analysis of Racism Within the US Presidency: Implications for African Americans and the Political Process. J. Afric. Am. Stud. 25, 383–401. doi: 10.1007/s12111-021-09543-5

Cohrs, J. C., and Asbrock, F. (2009). Right-wing authoritarianism, social dominance orientation and prejudice against threatening and competitive ethnic groups. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 39, 270–289. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.545

Cornelis, I., and Van Hiel, A. (2015). Extreme-right voting in western europe: the role of social-cultural and antiegalitarian attitudes. Polit. Psychol. 36, 749–760. doi: 10.1111/pops.12187

Craig, M. A., and Richeson, J. A. (2014). On the precipice of a “majority-minority” America: Perceived status threat from the racial demographic shift affects White Americans' political ideology. Psychol. Sci. 25, 1189–1197. doi: 10.1177/0956797614527113

Darlington, R. B. (1968). Multiple regression in psychological research and practice. Psychol. Bull. 69, 161. doi: 10.1037/h0025471

Davis, D. W., and Wilson, D. C. (2021). Racial Resentment in the Political Mind. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

De Figueiredo, R. J. P., and Elkins, Z. (2003). Are patriots bigots? An inquiry into the vices of in-group pride. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 47, 171–188. doi: 10.1111/1540-5907.00012

Deckman, M., and Cassese, E. (2021). Gendered nationalism and the 2016 US presidential election: how party, class, and beliefs about masculinity shaped voting behavior. Polit. Gender 17, 277–300. doi: 10.1017/S1743923X19000485

Dhont, K., Van Hiel, A., and Hewstone, M. (2014). Changing the ideological roots of prejudice: Longitudinal effects of ethnic intergroup contact on social dominance orientation. Group Proc. Intergroup Relat. 17, 27–44. doi: 10.1177/1368430213497064

Duckitt, J. (2001). “A dual-process cognitive-motivational theory of ideology and prejudice,” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Cambridge: Academic Press), 41–113.

Duckitt, J., and Sibley, C. (2009). A Dual Process Motivational Model of Ideological Attitudes and System Justification, 292–312.

Duckitt, J., and Sibley, C. G. (2010). Personality, ideology, prejudice, and politics: a dual-process motivational model. J. Pers. 78, 1861–1894. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00672.x

Duriez, B., and Van Hiel, A. (2002). The march of modern fascism. A comparison of social dominance orientation and authoritarianism. Pers. Individ. Dif. 32, 1199–1213. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00086-1

Duriez, B., Van Hiel, A., and Kossowska, M. (2005). Authoritarianism and social dominance in Western and Eastern Europe: the importance of the sociopolitical context and of political interest and involvement. Polit. Psychol. 26, 299–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2005.00419.x

Dwyer, C. E., Stevens, D., Sullivan, J. L., and Allen, B. (2009). Racism, sexism, and candidate evaluations in the 2008 US presidential election. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy 9, 223–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-2415.2009.01187.x

Ehrlich, G. A., and Gramzow, R. H. (2015). The politics of affirmation theory: when group-affirmation leads to greater ingroup bias. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 41, 1110–1122. doi: 10.1177/0146167215590986

Feffer, J. (2017). “Witnessing the birth of a new nationalist world order,” in The Huffington Post. Available at: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/john-feffer/the-birth-of-a-new-nation_b_14361104.html (accessed August 5, 2024).

Fording, R. C., and Schram, S. F. (2023). Pride or prejudice? Clarifying the role of white racial identity in recent presidential elections. Polity 55, 106–136. doi: 10.1086/722807

Franks, A. S. (2021). The conditional effects of candidate sex and sexism on perceived electability and voting intentions: evidence from the 2020 democratic primary. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy 21, 11–28. doi: 10.1111/asap.12215

Fraser, G., Osborne, D., and Sibley, C. G. (2015). “We want you in the workplace, but only in a skirt!” Social dominance orientation, gender-based affirmative action and the moderating role of benevolent sexism. Sex Roles 73, 231–244. doi: 10.1007/s11199-015-0515-8

Frasure-Yokley, L. (2018). Choosing the Velvet Glove: Women Voters, Ambivalent Sexism, and Vote Choice in 2016. J. Race, Ethni. Polit. 3, 3–25. doi: 10.1017/rep.2017.35

Glick, P. (2019). Gender, sexism, and the election: did sexism help Trump more than it hurt Clinton? Polit Groups Ident. 7, 713–723. doi: 10.1080/21565503.2019.1633931

Glick, P., and Fiske, S. (1996). The ambivalent sexism inventory: differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 70, 491–512. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.70.3.491

Gusterson, H. (2017). From brexit to Trump: anthropology and the rise of nationalist populism. Am. Ethnol. 44, 209–214. doi: 10.1111/amet.12469

Harnish, R. J., Bridges, K. R., and Gump, J. T. (2018). Predicting economic, social, and foreign policy conservatism: the role of right-wing authoritarianism, social dominance orientation, moral foundations orientation, and religious fundamentalism. Curr. Psychol. 37, 668–679. doi: 10.1007/s12144-016-9552-x

Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond baron and kenny: statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun. Monogr. 76, 408–420. doi: 10.1080/03637750903310360

Henry, P. J., Sidanius, J., Levin, S., and Pratto, F. (2005). Social dominance orientation, authoritarianism, and support for intergroup violence between the Middle East and America. Polit. Psychol. 26, 569–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2005.00432.x

Ho, A. K., Sidanius, J., Kteily, N., Sheehy-Skeffington, J., Pratto, F., Henkel, K. E., et al. (2015). The nature of social dominance orientation: Theorizing and measuring preferences for intergroup inequality using the new SDO7 scale. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 109, 1003–1028. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000033

Hooghe, M., and Dassonneville, R. (2018). Explaining the Trump vote: the effect of racist resentment and anti-immigrant sentiments. PS: Polit. Sci. Polit. 51, 528–534. doi: 10.1017/S1049096518000367

Huddy, L., and Del Ponte, A. (2021). “The rise of populism in the USA: Nationalism, race, and American party politics,” in The Psychology of Populism (London: Routledge), 258–275. doi: 10.4324/9781003057680-17

Jaffe, G., and Johnson, J. (2017). “Trump delights in watching the U.S. military display its strength,” in The Washington Post. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/trump-delights-in-watching-the-us-military-display-its-strength/2017/04/14/1f0e02a4-2113-11e7-ad74-3a742a6e93a7_story.html (accessed August 5, 2024).

Jardina, A. (2021). In-group love and out-group hate: white racial attitudes in contemporary US elections. Polit. Behav. 43, 1535–1559. doi: 10.1007/s11109-020-09600-x

Junn, J. (2017). The Trump majority: white womanhood and the making of female voters in the US. Polit. Groups Ident. 5, 343–352. doi: 10.1080/21565503.2017.1304224

Kinder, D. R., and Sears, D. O. (1981). Prejudice and politics: symbolic racism versus racial threats to the good life. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 40, 414. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.40.3.414

Knuckey, J. (2019). “I just don't think she has a presidential look”: sexism and vote choice in the 2016 election. Soc. Sci. Q. 100, 342–358. doi: 10.1111/ssqu.12547

Knuckey, J., and Kim, M. (2015). Racial resentment, old-fashioned racism, and the vote choice of southern and nonsouthern whites in the 2012 US presidential election. Soc. Sci. Q. 96, 905–922. doi: 10.1111/ssqu.12184

Kosterman, R., and Feshbach, S. (1989). Toward a measure of patriotic and nationalistic attitudes. Polit. Psychol. 257–274. doi: 10.2307/3791647

Lawless, J. L. (2009). Sexism and gender bias in election 2008: a more complex path for women in politics. Polit. Gender 5, 70–80. doi: 10.1017/S1743923X09000051

Levin, S., and Sidanius, J. (1999). Social dominance and social identity in the United States and Israel: ingroup favoritism or outgroup derogation? Polit. Psychol. 20, 99–126. doi: 10.1111/0162-895X.00138

Lind, D. (2015). “Donald Trump's war on muslims, explained,” in Vox. Available at: https://www.vox.com/2015/12/9/9872908/donald-trump-muslims

McConahay, J. B. (1986). “Modern racism, ambivalence, and the modern racism scale,” in Prejudice, Discrimination, and Racism, eds. J. F. Dovidio and S. L. Gaertner (San Diego, CA: Academic Press), 91–125.

McFarland, S. (2010). Authoritarianism, social dominance, and other roots of generalized prejudice. Polit. Psychol. 31, 453–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2010.00765.x

Mutz, D. C. (2018). Status threat, not economic hardship, explains the 2016 presidential vote. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 115, E4330–E4339. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1718155115

Osborne, D., Costello, T. H., Duckitt, J., and Sibley, C. G. (2023). The psychological causes and societal consequences of authoritarianism. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 2, 220–232. doi: 10.1038/s44159-023-00161-4

Osborne, D., Milojev, P., and Sibley, C. G. (2017). Authoritarianism and national identity: examining the longitudinal effects of SDO and RWA on nationalism and patriotism. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 43, 1086–1099. doi: 10.1177/0146167217704196

Parker, C. S., Sawyer, M. Q., and Towler, C. (2009). A black man in the white house?: The role of racism and patriotism in the 2008 presidential election. Du Bois Rev.: Soc. Sci. Res. Race 6, 193–217. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X09090031

Pasek, J., Tahk, A., Lelkes, Y., Krosnick, J. A., Payne, B. K., Akhtar, O., et al. (2009). Determinants of turnout and candidate choice in the 2008 US presidential election: Illuminating the impact of racial prejudice and other considerations. Public Opin. Q. 73, 943–994. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfp079

Payne, B. K., Krosnick, J. A., Pasek, J., Lelkes, Y., Akhtar, O., and Tompson, T. (2010). Implicit and explicit prejudice in the 2008 American presidential election. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 46, 367–374. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2009.11.001

Peitz, L., Dhont, K., and Seyd, B. (2018). The psychology of supranationalism: Its ideological correlates and implications for EU attitudes and post-Brexit preferences. Polit. Psychol. 39, 1305–1322. doi: 10.1111/pops.12542

Perry, R., and Sibley, C. G. (2013). A dual-process motivational model of social and economic policy attitudes. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy 13, 262–285. doi: 10.1111/asap.12019

Pettigrew, T. F. (2017). Social psychological perspectives on Trump supporters. J. Soc. Polit. Psychol. 5, 107–116. doi: 10.5964/jspp.v5i1.750

Pettigrew, T. F., and Hewstone, M. (2017). The Single Factor Fallacy: Implications of Missing Critical Variables from an Analysis of Intergroup Contact Theory1. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 11, 8–37. doi: 10.1111/sipr.12026

Pettigrew, T. F., Tropp, L. R., Wagner, U., and Christ, O. (2011). Recent advances in intergroup contact theory. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 35, 271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.03.001

Pew Research Center (2024). Racial Attitudes and the 2024 Election. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2024/06/06/racial-attitudes-and-the-2024-election/ (accessed September 16, 2024).

Piston, S. (2010). How explicit racial prejudice hurt Obama in the 2008 election. Polit. Behav. 32, 431–451. doi: 10.1007/s11109-010-9108-y

Pratto, F., Çidam, A., Stewart, A. L., Zeineddine, F. B., Aranda, M., Aiello, A., et al. (2013). Social dominance in context and in individuals: Contextual moderation of robust effects of social dominance orientation in 15 languages and 20 countries. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 4, 587–599. doi: 10.1177/1948550612473663

Pratto, F., and Pitpitan, E. V. (2008). Ethnocentrism and sexism: how stereotypes legitimize six types of power. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2, 2159–2176. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00148.x

Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., Stallworth, L. M., and Malle, B. F. (1994). Social dominance orientation: a personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 67, 741–763. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.67.4.741

Rhodes, J., Nteta, T., and Eichen, A. (2024). “How will racial prejudice impact the 2024 election?,” in Newsweek. Available at: https://www.newsweek.com/how-will-racial-prejudice-impact-2024-election-opinion-1950957 (accessed September 16, 2024).

Rios, K., Sosa, N., and Osborn, H. (2018). An experimental approach to Intergroup Threat Theory: Manipulations, moderators, and consequences of realistic vs. symbolic threat. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 29, 212–255. doi: 10.1080/10463283.2018.1537049

Rollero, C., Peter, G., and Tartaglia, S. (2014). Psychometric properties of short versions of the ambivalent sexism inventory and ambivalence toward men inventory. TPM Test. Psychom. Method. Appl. Psychol. 21, 149–159. doi: 10.4473/TPM21.2.3

Schaffner, B. F. (2022). The heightened importance of racism and sexism in the 2018 US midterm elections. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 52, 492–500. doi: 10.1017/S0007123420000319

Schaffner, B. F., Macwilliams, M., and Nteta, T. (2018). Understanding white polarization in the 2016 vote for president: the sobering role of racism and sexism. Polit. Sci. Q. 133, 9–34. doi: 10.1002/polq.12737

Shook, N. J., Fitzgerald, H. N., Boggs, S. T., Ford, C. G., Hopkins, P. D., and Silva, N. M. (2020). Sexism, racism, and nationalism: factors associated with the 2016 U.S. presidential election results? PLoS ONE 15:e0229432. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229432

Shook, N. J., Hopkins, P. D., and Koech, J. M. (2016). The effect of intergroup contact on secondary group attitudes and social dominance orientation. Group Proc. Intergroup Relat. 19, 328–342. doi: 10.1177/1368430215572266

Sibley, C. G., Wilson, M. S., and Duckitt, J. (2007). Antecedents of men's hostile and benevolent sexism: the dual roles of social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 33, 160–172. doi: 10.1177/0146167206294745

Sidanius, J., and Pratto, F. (2001). Social Dominance: An Intergroup Theory of Social Hierarchy and Oppression. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sides, J., Tesler, M., and Vavreck, L. (2019). Identity Crisis: The 2016 Presidential Campaign and the Battle for the meaning of America. Princeton: Princeton University Press. doi: 10.2307/j.ctvktrvp5

Simas, E. N., and Bumgardner, M. (2017). Modern sexism and the 2012 US presidential election: Reassessing the casualties of the “war on women.” Polit. Gender 13, 359–378. doi: 10.1017/S1743923X17000083

Thompson, J. (2021). What it means to be a “true American”: Ethnonationalism and voting in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Nations National. 27, 279–297. doi: 10.1111/nana.12638

Thomsen, L., Green, E. G., and Sidanius, J. (2008). We will hunt them down: How social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism fuel ethnic persecution of immigrants in fundamentally different ways. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 44, 1455–1464. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2008.06.011

Thomson-DeVeaux, A. (2019). “Americans say they would vote for a woman, but…,” in Five Thirty Eight. Available at: https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/americans-say-they-would-vote-for-a-woman-but/ (accessed August 5, 2024).

Van Assche, J., Dhont, K., and Pettigrew, T. F. (2019). The social-psychological bases of far-right support in Europe and the United States. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 29, 385–401. doi: 10.1002/casp.2407

VanderWeele, T., and Vansteelandt, S. (2014). Mediation analysis with multiple mediators. Epidemiol. Methods 2, 95–115. doi: 10.1515/em-2012-0010

Vargas-Salfate, S., Liu, J. H., and Gil de Zúñiga, H. (2020). Right-wing authoritarianism and national identification: the role of democratic context. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 32, 318–331. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/edz026

Watson-Thompson, J., Hassaballa, R. H., Valentini, S. H., Schulz, J. A., Kadavasal, P. V., Harsin, J. D., et al. (2022). Actively addressing systemic racism using a behavioral community approach. Behav. Soc. Issues 31, 297–326. doi: 10.1007/s42822-022-00101-6

Wedell, E., and Bravo, A. J. (2022). Synergistic and additive effects of social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism on attitudes toward socially stigmatized groups. Curr. Psychol. 41, 8499–8511. doi: 10.1007/s12144-020-01245-7

Whitehead, A. L., Perry, S. L., and Baker, J. O. (2018). Make America Christian again: Christian nationalism and voting for Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential election. Sociol. Relig. 79, 147–171. doi: 10.1093/socrel/srx070

Wolbrecht, C. (2010). The politics of women's rights: Parties, Positions, and Change. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Keywords: prejudice, social dominance orientation, right-wing authoritarianism, modern racism, sexism, nationalism, dual-process motivational model, presidential election

Citation: Rusowicz A, Pratto F and Shook N (2024) The dual process of prejudice: racism, nationalism, and sexism in the 2020 U.S. presidential election. Front. Soc. Psychol. 2:1479895. doi: 10.3389/frsps.2024.1479895

Received: 13 August 2024; Accepted: 12 November 2024;

Published: 04 December 2024.

Edited by:

Jazmin Brown-Iannuzzi, University of Virginia, United StatesReviewed by:

Tuuli Anna Renvik, City of Helsinki, FinlandDiana Betz, Loyola University Maryland, United States

Copyright © 2024 Rusowicz, Pratto and Shook. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Natalie Shook, bmF0YWxpZS5zaG9va0B1Y29ubi5lZHU=

Aleksandra Rusowicz

Aleksandra Rusowicz Felicia Pratto1

Felicia Pratto1 Natalie Shook

Natalie Shook