95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Soc. Psychol. , 06 November 2024

Sec. Attitudes, Social Justice and Political Psychology

Volume 2 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frsps.2024.1465810

This article is part of the Research Topic Social and Political Psychological Perspectives on Global Threats to Democracy View all 8 articles

Introduction: In recent years, the literature on Christian nationalism has grown exponentially. Studies have found that individuals who score high on a widely used Christian nationalism scale are likelier to advocate for traditional gender roles, endorse anti-immigrant policies, support policies limiting voting rights, oppose gun control and interracial marriage, express anti-vaccine attitudes, hold anti-globalist sentiments, and vote for Donald Trump. The literature on Christian nationalism is not without its critics, however. Some, for example, have questioned whether the scale used by many studies adequately identifies Christian nationalists and suggested alternative methods for doing so. Much of the literature also implicitly or explicitly equates Christian nationalism with white Christian nationalism, ignoring the fact that 25 to 30 percent of respondents who express Christian nationalist sentiments identify as Black, Hispanic, Asian, or another race or ethnicity. Finally, most of it has focused on the consequences of Christian nationalism. Very little has explored the predictors of Christian nationalism. The latter is the focus of this paper.

Methods: Drawing on multivariate logistic regression, it examines potential factors driving Christian nationalist attitudes.

Results: It finds that age, whether someone identifies as a conservative or a Republican, biblical literalism, and frequent worship attendance are positively associated with Christian nationalism, while being affiliated with religious traditions other than evangelicalism (or having no affiliation at all) is negatively associated with it. Notably, race and ethnicity have no effect, suggesting that other factors may be at work.

Discussion: As such, the paper briefly considers four potential factors not readily captured by statistical analyses of cross-sectional data. It concludes by noting that if Christian nationalism is potentially undemocratic and dangerous, then concerned individuals need to focus as much time and energy on its predictors as its consequences.

In June 2024, Louisiana Governor Jeff Landry signed a law requiring that public schools place the 10 Commandments in every classroom. A few weeks later, Oklahoma state superintendent Ryan Walters ordered all public schools to teach the Bible. Both mandates will almost certainly be challenged in court. Regardless of the outcome, they reflect some of the latest attempts to fuse Christianity and American civic life, what is generally called Christian nationalism. In recent years, this toxic form of nationalism has caught the attention of scholars and pundits alike e.g., (see Baker et al., 2020; Perry et al., 2020; Whitehead and Perry, 2020; Whitehead et al., 2018a; Du Mez, 2020; Stewart, 2020; Gorski, 2020; Perry and Whitehead, 2015). We can trace much of their interest to the political climate that led to the 2016 election of Donald Trump. However, after the January 6, 2021, raid on the U.S. Capitol, some of which blended Christian imagery with political violence, research on Christian nationalism “exploded” (Smith and Adler, 2022, p. 1). Everyone, it seems, wants to get in on the act e.g., (see Tyler, 2022; Tyler, 2024; Butler, 2022; Gorski and Perry, 2022; Perry and Whitehead, 2015; Stewart, 2022; Tisby, 2022; Whitehead and Perry, 2022; Nie, 2024; Perry et al., 2023; Jones, 2021; Jones, 2023; Kaylor and Underwood, 2023; Kaylor and Underwood, 2024; Corcoran et al., 2021; Armaly et al., 2022; Butler, 2021; Perry et al., 2022; Braunstein, 2021). Including me, apparently.

Not all forms of nationalism are harmful or incompatible with liberal democracy (Tamir, 2019; Tamir, 1993; Mounk, 2018; Mounk, 2022; Brooks, 2018). At its core, nationalism is the idea that states should be ruled in the name of the nation rather than dynastic succession (e.g., kingdoms), a particular civilization (e.g., empires), or a God (e.g., theocracies; Wimmer, 2021; Wimmer and Feinstein, 2010; Wimmer and Min, 2006). To be sure, nation-states are “imagined political communities” in the sense that “even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion” (Anderson, 2016, p. 6). Nevertheless, in its simplest form, nationalism holds that nations should be free to govern themselves and opposes any form of foreign rule or outside interference that disregards the interests of the national majority (Wimmer, 2021; Wimmer and Feinstein, 2010; Wimmer and Min, 2006). As such, it can be entirely compatible with philosophical liberalism (Tamir, 1993; Tamir, 2019).

Nationalism can turn illiberal when it connects national identity with a limited number of cultural and ethnic identities (e.g., religion, ideology, race; Miller, 2022). Overlapping social identities strengthen ingroup boundaries and foster outgroup prejudice and intolerance (Roccas and Brewer, 2002; Miller et al., 2009; Brewer and Pierce, 2005). Indeed, over 70 years ago, Niebuhr ([1952] 2008) warned about the dangers of religious nationalism because it brought together different forms of collective pride (Gorski, 2017). He traced Christian nationalism’s development in the U.S. to the belief that America is God’s “American Israel” (Niebuhr, [1952] 2008, p. 24) and that with the founding of the United States, America had turned its “back upon the vices of Europe” (Niebuhr, [1952] 2008, p. 28) to “make a new beginning in a corrupt world” (Niebuhr, [1952] 2008, p. 28:25). Although, at first, Americans initially saw their nation’s increasing prosperity as a sign of God’s grace, over time they came to believe it was evidence of their moral superiority and virtue (Niebuhr, [1952] 2008, p. 28:51).

American Christian nationalism is similar to other forms of religious nationalism that seek to fuse nationalistic pride with a particular faith (e.g., Hindu nationalism in India). It is the belief that (1) America was founded as a Christian nation (or, at a minimum, its founding is based on Christian principles), (2) Christian beliefs should inform the crafting of the laws and policies of the United States, and (3) Christianity should be accorded a privileged place in American public life. American Christian nationalism is not unlike the Christian nationalisms that have emerged in other countries. For example, Hungary’s Prime Minister, Victor Orbán, has advocated on behalf of Christian nationalism and has pushed through laws supportive of Christian nationalist concerns. His efforts have received plaudits from the American conservative political observer and Orthodox Christian Rob Dreher:

Orbán was so unafraid, so unapologetic about using his political power to push back on the liberal elites in business and media and culture. It was so inspiring: this is what a vigorous conservative government can do if it’s serious about stemming this horrible global tide of wokeness (Marantz, 2022).

Dreher is no fan of Donald Trump, but he does support electing a President who will seek to pass laws that are consistent with Christian nationalist values. “According to Dreher, what the Republican Party needs is ‘a leader with Orbán’s vision—someone who can build on what Trumpism accomplished, without the egomania and the inattention to policy, and who is not afraid to step on the liberals’ toes’” (Marantz, 2022). Similarly, journalist Tim Alberta notes many parallels between American and Russian Christian nationalism. “As the historian Mara Kozelsky observed, ‘Orthodox Christian nationalism has been on the rise in Russia from the collapse of the Soviet Union,’ the by-product of a state desperate to rediscover legitimacy in the eyes of a chastened and aimless populace” (Alberta, 2023, p. 232). Despite these similarities, however, we should not assume that the underlying causes of Christian nationalism in Hungary, Russia, and other countries are identical to those in the United States. Each has its historical context, which shapes how and why citizens in those countries find it appealing.

Christian nationalism is just one of many types of nationalism (Schildkraut, 2002; Schildkraut, 2011; Smith, 1997a; Smith, 1997b). For example, Bonikowski and Dimaggio (2016) have identified four types in the United States: creedal (22 percent), disengaged (17 percent), restrictive (38 percent), and ardent (24 percent). “Creedal nationalism refers to the form of national self-understanding associated with a set of liberal principles—universalism, democracy, and the rule of law—sometimes referred to as the American creed” (Bonikowski and DiMaggio, 2016, pp. 962–963). Creedal nationalists are likelier to be immigrants and tend to be well-educated, enjoy high levels of income, and live outside of the South. They differ from disengaged nationalists, who profess low levels of national pride, appear reluctant to embrace a national identity, and are unlikely to affirm even the most widely held nationalist beliefs. Most are well-educated, well-paid immigrants or young, well-educated, secular Democrats who live on the East or West Coast. Restrictive nationalists tend to express “only moderate levels of national pride but [understand what it means to be] ‘truly American’ in particularly exclusionary ways” (Bonikowski and DiMaggio, 2016, p. 961). Over half agree that to be “truly American,” one must be a Christian. Restrictive nationalists are “disproportionately female, African American or Hispanic, Evangelical or Black Protestant, low in education and income, and born in the United States” (Bonikowski and DiMaggio, 2016, p. 964). Finally, ardent nationalists rank high on nearly every nationalism measure. Most are “very proud” of being an American and of America’s history, its armed forces, and its achievements and are “disproportionately older, less educated, white Evangelical Republicans living in the South” (Bonikowski and DiMaggio, 2016, p. 964). This final category closely resembles those identified as Christian nationalists in much of the literature.

Many, if not most, of the recent studies of Christian nationalism, have used a 24-point scale that combines responses to six 5-point Likert scale survey items, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree, that ask respondents their attitudes to various religious freedom policies (see Table 1). Whitehead and Perry et al. (2020) have sorted respondents into four categories based on their responses to these questions: Ambassadors (18 to 24 points), Accommodators or sympathizers (12 to 17 points), Resisters (6 to 11 points), and Rejecters (0 to 5 points). Ambassadors are “wholly supportive of Christian nationalism” (p. 35); accommodators tend to believe “that the federal government should advocate for Christian values [but are] undecided about the federal government officially declaring the United States is a Christian nation” (p. 33); resisters tend to oppose Christian nationalist views but are often “undecided about allowing the display of religious symbols in public places” (p. 31); and rejectors “generally believe there should be no connection between Christianity and politics” (p. 26). Along with their colleagues, Whitehead and Perry show that individuals scoring high on the scale are likelier to advocate for traditional gender roles, endorse anti-immigrant policies, support policies limiting voting rights, oppose gun control and interracial marriage, express anti-vaccine attitudes and resist wearing masks during the pandemic, hold small-government libertarian views, anti-globalist sentiments, and vote for Donald Trump (Whitehead and Perry, 2020; Baker et al., 2020; Perry et al., 2020; Whitehead et al., 2018a; Perry et al., 2023; Tyler, 2024; Davis et al., 2023; Whitehead et al., 2018b; Perry and Whitehead, 2015).

The literature on Christian nationalism is not without its critics. Some have questioned whether the scale adequately identifies Christian nationalists and have suggested alternative methods for identifying them (e.g., Davis, 2023; Li and Froese, 2023; Smith and Adler, 2022; Woodward, 2023). Another issue is that some of the literature implicitly or explicitly equates Christian nationalism with white Christian nationalism (Jones, 2021; Jones, 2023; Gorski and Perry, 2022; Butler, 2022; Stewart, 2020; Du Mez, 2020; Tisby, 2019; Whitehead and Perry, 2020). Consider, however, Table 2. It presents the racial and ethnic breakdown of Christian nationalists according to three different classification schemes;1 it shows that approximately 25 to 30 percent identify as Black, Hispanic, Asian, or another race or ethnicity. Notably, the table also shows that Christian nationalism appears to be in decline. Regardless of the scheme, the proportion of Americans expressing Christian nationalist sentiments dropped 5 to 6% from 2017 to 2021. Only 15 to 20 percent could be classified as Christian nationalists in 2021. The focus on white Christian nationalism can also leave readers with the impression that most non-Hispanic white Christians are Christian nationalists. However, as the results in Table 3 show, that is not the case. Only between 22 and 31 percent of white Christians can be classified as Christian nationalists.

A final weakness is that, aside from historical accounts (e.g., Braunstein, 2021; Du Mez, 2020; Hoffman and Ware, 2024; Kaylor and Underwood, 2024), most of the literature has focused on the consequences of Christian nationalism. As we have seen, Christian nationalists are likelier to embrace traditional gender roles, endorse anti-immigrant policies, support limitations on voting rights, oppose gun control, express anti-vaccine attitudes, hold anti-globalist sentiments, and so on. However, very few have explored the predictors of Christian nationalism. That is the focus of this paper. It begins with an extended examination of the scale pioneered by Whitehead and Perry and used in much of the current literature. We will see that the questions used for the scale were not originally intended to measure Christian nationalism and do not reflect a single dimension of belief. Accordingly, the paper introduces and utilizes two additional methods for identifying Christian nationalists. Using these two schemes plus the original Whitehead and Perry scale, it estimates a series of logistic regression models to explore potential factors driving Christian nationalist attitudes. After discussing the results, the paper considers four additional factors not readily captured by statistical analyses of cross-sectional data. The paper concludes with a summary of the results and an appeal to those concerned about Christian nationalism to focus as much time and energy on its causes as its consequences.

The questions used in the Whitehead and Perry scale first appeared in the 2005 wave of the Baylor Religion Survey (BRS). They were intended to capture what some scholars call a “sacralization ideology” (Froese and Mencken, 2009; Hadden, 1987; Stark and Iannaccone, 1994), not Christian nationalist sentiments (Smith and Adler, 2022; Li and Froese, 2023). Notably, only two of the questions explicitly mention Christianity. The others could easily be used to examine civic republicanism, civil religion, religious traditionalism, and/or debates about the separation of church and state (Gorski, 2017; Smith and Adler, 2022; Froese and Mencken, 2009; Li and Froese, 2023). Another concern is that Whitehead and Perry treat the undecided option as a neutral midpoint. However, it is unclear whether the response reflects an indifferent attitude toward Christian nationalism or a moderate one. Accordingly, the scale likely introduces measurement error by assigning a “nontrivial number of ‘points’” to a respondent’s score (Davis, 2023, p. 5). For example, if someone selected the “undecided” option for all six questions, their aggregate score of 12 points would classify them as a Christian nationalist accommodator/sympathizer when, in fact, they may be nothing of the sort.

Concerns such as these have led some to question whether the scale adequately captures “Christian nationalism.” For example, Woodward (2023, 2024), the former religion editor at Newsweek, was surprised to learn that he is a Christian nationalist:

Respondents were sorted into four categories: ambassadors (strong support for all or some of the statements); accommodators (weak support); resisters (weak objections); and rejecters (strong opposition). Despite my total opposition to the first and [fifth] statements, my tempered support for the other propositions, mainly on First Amendment grounds, identifies me as an accommodator. Being an accommodator of Christian nationalism is a daunting responsibility. My problem, though, is this: I do not know any Christian nationalists (Woodward, 2023, emphasis added).

Woodward also notes that a 2022 Pew Survey found that 54 percent of Americans “had never heard of the term ‘Christian nationalism,’ and another 17 percent or so had heard only ‘a little bit.’ Of the 14 percent who had heard ‘quite a bit’ or ‘a great deal,’ only 5 percent held a favorable view. Another 24 percent were unfavorable. That’s not a base broad enough to support a populist movement” (Woodward, 2023).

Nicholas Davis (2023) believes the scale is so flawed that it should be scrapped altogether. Although it registers a high Cronbach-α score, which is generally seen as a sign of internal reliability, he notes that “Cronbach’s α cannot tell the researcher much about dimensionality, despite researchers commonly reporting it as such” (Davis, 2023, p. 6, emphasis in original). Using factor analysis, he shows that the six items “do not readily collapse” into a unidimensional scale (Davis, 2023, p. 2). He argues that scholars would be better off operationalizing Christian nationalism using a categorical approach, such as latent class analysis (LCA), which sorts respondents into groups based on the similarity of their responses:

LCA first determines how many classes are needed to account for the variation among input items and then assigns respondents a probability of being placed in a group with other individuals whose pattern of responses to the input items resembles a group archetype. It is an agnostic approach to clustering that can determine how many groups exist within the Christian nationalism index, as well as who goes with what group (Davis, 2023, p. 9).

Davis uses LCA to sort respondents into four categories or classes and shows that they differ substantially from those used by Whitehead and Perry. According to his analysis, the Whitehead and Perry scale misclassifies 28 percent of respondents.

Davis does not explore how the four classes predict various outcomes or the sociodemographic factors driving class membership. Smith and Adler (2022) do, however.2 They apply LCA to responses to the six items in the 2017 BRS. They identify six classes instead of four,3 whom they label Christian nationalists (20 percent), religious conservatives (21 percent), undecideds (9 percent), pluralist civic republicans (18 percent), secular civic republicans (20 percent), and radical secularists (13 percent). They find that Christian nationalists tend to be less educated and, surprisingly, more likely to count themselves among the religious “nones” (i.e., the religiously unaffiliated). Interestingly, though, they are likelier than religious conservatives to be biblical literalists and more likely than any other group (except the undecideds) to oppose same-sex marriage. They are also inclined to vote for Donald Trump and believe that the police treat white and black individuals equally.

Like Davis (2023) and Li and Froese (2023) argue that the scale’s six items reflect more than a single dimension. Using exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis, they find that two of the items “load” (are associated with) what they call Christian statism (CS), two with what they call religious traditionalism (RT), and two cannot be uncategorized.4 Specifically, they find that the first two questions listed in Table 1 (the federal government should declare the United States a Christian nation and advocate Christian values) are associated with CS, while the third and sixth (the federal government should allow the display of religious symbols in public spaces and prayer in public schools) are associated with RT.5 Importantly, their analysis shows that CS and RT predict very different outcomes. For example, while CS is positively associated with the belief that Middle East refugees are terrorists and illegal immigrants are criminals, RT is not. CS is also positively associated with the belief that Muslims are morally inferior, endanger personal safety, and want to limit individual freedoms, while RT is not. Furthermore, “Religious Traditionalists tend to reject overt nativism, racial antipathy, and religious intolerance—attitudes strongly expressed by many of Trump’s white evangelical supporters” (Li and Froese, 2023, p. 794).

Li and Froese’s analysis does not provide a means to distinguish Christian nationalists from religious traditionalists and other respondents. They provide no threshold CS score above which a respondent could be classified as a Christian nationalist. It is unlikely they could, however, since respondents can score high on both the CS and RT dimensions. However, we can classify respondents who agree or strongly agree that the federal government should declare the United States a Christian nation and promote Christian values as Christian Statists (CS).6 Table 4 compares the similarity of this approach with the Whitehead and Perry scale and Smith and Adler’s LCA. It presents the Jaccard similarity scores of the three schemes using responses to the 2021 BRS.7 It shows that while there are some similarities between them, there are clear differences, suggesting that identifying who is and who is not a Christian nationalist is not as straightforward as some would want us to believe.

To explore potential factors driving Christian nationalist attitudes, this paper estimates a series of multivariate logistic regression models predicting whether a respondent is classified as a Christian nationalist by Whitehead and Perry’s scale, Smith and Adler’s LCA, or Li and Froese’s CS. Using all three classification schemes allows us to identify factors that consistently predict Christian nationalist sentiments rather than those that only “matter” using one classification scheme but not the others. For the analysis below, the models use the 2021 BRS. Since 2005, the Baylor Department of Sociology has partnered with Gallup to conduct “a nationally representative multiyear study” of American religion and its place in American society (Bader et al., 2007). The 2021 BRS is the sixth wave of the BRS. The previous five were collected in 2005, 2007, 2010, 2014, and 2017. The paper utilizes multiple imputation (MI) methods as implemented in Stata 18 (Statacorp, 2023) to supplement the original data.8 Some scholars use MI for both independent and dependent variables (e.g., Smith and Adler, 2022). This analysis estimates and compares models that impute missing data for both and for models that only use MI for the independent variables. Because some scholars (e.g., Winship and Radbill, 1994) recommend not using sampling weights when estimating multivariate models, the following analysis compares models with and without sampling weights. Models that used sampling weights and only imputed missing data for independent variables yielded the lowest AIC (Akaike, 1974) and BIC (Schwarz, 1978) scores, indicating a better fit. Accordingly, those are the results presented below.9

Tables 5–7 present the results of the logistic regressions. The first model in all three sets of regressions includes only race and ethnicity variables. The second includes additional demographic variables, such as gender, marital status, age (65 and over), education, income level, and whether respondents live in a rural setting and/or the South. The third adds two dummy variables: one indicating whether respondents identified as conservative and one whether they identified as Republican. The fourth adds religious affiliation data (e.g., Mainline Protestant, Roman Catholic, etc.), and the fifth adds variables indicating whether respondents are biblical literalists or attend worship services once a month or more.

In the models with only race and ethnicity variables (Model 1), Asians and Hispanics appear less likely to express Christian nationalist sentiments than white individuals. The coefficients are negative and statistically significant in two of the three tables. The Hispanic effect disappears once other demographic variables are included (Model 2), while the Asian effect remains statistically significant until the conservative and Republican variables are included (Model 3). Of the demographic variables, only age remains statistically significant in the remaining models. As the results show, individuals 65 years and older are more likely to be classified as Christian nationalists. In contrast, the effects of gender, being married, having a college degree, earning more than $100 thousand a year, and living in a rural area or the South cease to be statistically significant by Model 5. Two primary drivers of Christian nationalist attitudes are identifying as a conservative or a Republican. From the third through the fifth models, the coefficients for both variables are statistically significant and positively associated with being classified as a Christian nationalist. This is perhaps unsurprising considering former President Trump’s “takeover” of the Republican party. Whether this will hold in the future remains to be seen.

The religious affiliation variables included in the fourth model indicate that Black Protestants, Roman Catholics, members of other religious traditions, and the unaffiliated are less likely than Evangelical Protestants to be sorted into a Christian nationalist category. What is less clear is how Mainline Protestants compare to Evangelical Protestants. The Mainline Protestant coefficient is negative across all sets of models, but it is only statistically significant in those using Adler and Smith’s LCA classification scheme. Mainline Protestantism is typically associated with theological and political liberalism (Finke and Stark, 2005), so the fact that in two of the three sets of models, Mainline Protestants are no less likely than evangelicals to express Christian nationalist attitudes is perhaps somewhat surprising. However, as Kaylor and Underwood (2023, 2024) have recently shown, Mainline Protestantism also played a role in the development of American Christian nationalism.

Finally, in the fifth and full model, the coefficients for biblical literalism and worship attendance are positively and statistically significant. Biblical literalism’s positive effect is consistent with Philip Gorski’s (2017, 2021) claim that American Christian nationalism is linked to literalist interpretations of the biblical text:

Religious nationalism is rooted in the Bible [and] a heterodox reading of the apocalyptic texts popularly known as “prophecy belief.” On the orthodox reading of these texts originally set out by Saint Augustine and other church fathers, the apocalyptic texts are to be read figuratively and allegorically. The violent struggles between the forces of good and evil described in the texts are actually recurring struggles that take place in the human heart. On the heterodox reading that has become among American evangelicals, these struggles take place on an earthly stage and the forces of good and evil assume physical form, probably at some date in the not too distant future. Prophecy believers interpret the apocalyptic texts literally and predictively rather than allegorically and figuratively (Gorski, 2021, pp. 25–26).

The positive and statistically significant coefficient for monthly worship attendance is notable since there is some evidence of a negative (or no) association between church attendance and voting for Trump (Gorski, 2021; Whitehead et al., 2018a). To be sure, voting for Trump and expressing Christian nationalist sentiments are not the same. Nevertheless, given the strong and positive association between Christian nationalism and voting for Trump (Baker et al., 2020; Whitehead et al., 2018a), we should not be surprised that worship attendance is positively associated with Christian nationalism.

To visually compare the effect of the independent variables on the likelihood of being classified as a Christian nationalist, Figure 1 presents a coefficient plot of the average marginal effects of the variables included in the full model (Model 5) for the three sets of logistic regressions. A variable’s marginal effect reflects how changes in the variable are associated with changes in the dependent variable, holding other variables constant. The effects are normalized, making the effects of the variables comparable. In the plot, the circles (Whitehead and Perry Scale), squares (Adler and Smith LCA), and diamonds (Li and Froese CS) indicate the variables’ marginal effects, while the lines intersecting them indicate their 95% confidence intervals. An effect is statistically significant if a variable’s confidence interval does not cross the 0.00 threshold (vertical dotted line). Visually, the plot suggests that although the effects of the individual variables differ, they tend to “follow” one another. That is, the sizes of the effects are similar, and they generally “point” in the same direction (i.e., either positive or negative). At a glance, we can see that age, whether someone identifies as a conservative or a Republican, biblical literalism, and frequent worship attendance are positively associated with Christian nationalism, while Black Protestants, Roman Catholics, people of other faiths (e.g., Judaism, Buddhism, Hinduism, and Islam), and the unaffiliated are not.

Most notably, at least for the purposes of this paper, race and ethnicity do not appear to affect whether someone is classified as a Christian nationalist, at least not in the way one might expect. In some of the reduced models, the Asian and Hispanic coefficients are negative and statistically significant, but these effects disappear in the full models. Surprisingly, though, in the models using Smith and Adler LCA, African Americans are more (not less) likely than white respondents to be classified as Christian nationalists, and this effect holds even when Black Protestant affiliation is absent from the model (Model 3). Since this effect does not appear in the other two sets of models, we probably should regard it with caution and treat it as something worthy of additional research. Regardless, in all three sets of models, non-Hispanic white respondents are not more likely than respondents who identify as Black, Hispanic, Asian, or another race or ethnicity to be classified as Christian nationalists.

This result is not new. Others have noted it, including Whitehead and Perry (2020, p. 179), Smith and Alder (2022, p. 9), and Li and Froese (2023):

Our theory and past research suggest that CS and [Christian nationalism] are racially coded that promote overt white racism… Using our data, we… fail to make the inference that non-Hispanic whites score higher on both CS and RT scale than blacks and other ethno-racial groups… To properly test the racialized thesis, new survey items including more straightforward reference of race would perhaps be necessary. For example, one may ask if the country will be a better nation if the federal government declares America a white Christian nation (Li and Froese, 2023, p. 793).

Interestingly, although the 2021 BRS did not ask respondents “if the country will be a better nation if the federal government declares America a white Christian nation,” it did ask them, “Do you support or oppose [this] social movement? White Nationalism.” Thus, we can calculate how many Christian nationalists indicated that they support (or strongly support) white nationalism. Unsurprisingly, very few did. Of all respondents, only 3.77 percent expressed support for it, and of those classified as Christian nationalists, between six to 7 % did, approximately 1 % of all respondents. To paraphrase Kenneth Woodward, that is not a very large base of support for a populist movement. To be sure, some respondents may have been reluctant to express support for white nationalism openly, so the level of support among Christian nationalists (and non-Christian nationalists) may be higher. Nevertheless, these low percentages do suggest that white Christian nationalism is better seen as a relatively small subset of those individuals who hold Christian nationalist sentiments.

The cross-sectional survey data used in most studies of Christian nationalism cannot capture all possible factors that could have led to its (re)emergence in the last 10 to 20 years. Thus, it seems appropriate to briefly explore other potential dynamics before concluding. Here, we will consider four: (1) the rise in deaths of despair (Case and Deaton, 2015), (2) the left behind in rural America (Wuthnow, 2018), (3) technocratic liberalism and the tyranny of merit (Sandel, 2020), and (4) nationalism’s natural appeal (Reno, 2019). In isolation, they would unlikely have led to the most recent rise of Christian nationalism. Together, though, they can help account for why many Americans felt as if they were “under siege,” leading them to yearn for a “bygone era” when America was great (Bonikowski, 2016, p. 428), a yearning nicely captured by the promises of Christian nationalism.

Case and Deaton (2015) showed that after 1998, the mortality rate of middle-aged non-Hispanic white Americans had begun to rise after decades of decline. They traced the reversal to a surge in alcohol-related deaths, drug overdoses, and suicides. These soon became known as “deaths of despair” (Case and Deaton, 2020) because scholars connected them to a rising sense of despair in areas of the U.S. that had lagged economically and demographically behind the rest of the country. It is notable that in 2016, Trump and his fellow Republicans attracted higher-than-expected support in many “left behind” counties, particularly in those where life expectancy had stagnated or fallen (Bor, 2017). Indeed, counties with a net gain in Republican voters had a 15 percent higher age-adjusted death rate in 2015 than counties with a net gain in Democratic voters; in the former, the increase in deaths of despair was 2.5 times higher than in the latter counties (Goldman et al., 2019).

Researchers have struggled to identify factors contributing to the increase in deaths of despair. Are they purely due to material causes, or do other factors, such as social capital, play a role (Zoorob and Salemi, 2017; Case and Deaton, 2020)? Recently, Giles et al. (2023) have shown that for middle-aged white Americans, the increase in deaths of despair actually began earlier, in the early 1990s. They trace this increase to the widespread decline in religious participation that started in the 1980s,10 a decline primarily driven by middle-aged white Americans. They show that the decline in religious practice significantly affected the increase in deaths of despair mortality rates. Why? It is well established that religious practice is strongly correlated with well-being; on average, active people of faith enjoy healthier, happier, and longer lives (Flannelly et al., 2002; Koenig et al., 2001; Pargament et al., 1998; Hummer et al., 2004; Hummer et al., 1999; Beit-Hallahmi and Argyle, 1997; Asma, 2018; Levin, 1994; Levin, 2016). One reason is that people of faith consistently eat better, exercise more, drink and smoke less, and regulate their sexual behavior (Beit-Hallahmi and Argyle, 1997); most religious traditions also provide adherents with psychological resources that help them navigate traumatic events (Asma, 2018; Pargament and Park, 1995; Pargament et al., 1998). A second reason is that faith communities offer numerous opportunities for social interaction, which, all else equal, enhances health and subjective well-being. Frequent churchgoers report larger social networks, more favorable perceptions of their social relationships, and higher levels of social support from their network ties (Ellison and George, 1994).11 Recent studies have found that people with numerous social ties are less likely to suffer from heart disease, strokes, hypertension, diabetes, infectious diseases, cognitive decline, dementia, depression and anxiety, suicidal thoughts, and self-harm (U.S. Surgeon General of The United States, 2023). Finally, religious belief and practice provide the faithful with a sense of meaning and belonging (Smith, 2003; Smith, 2017; Smith et al., 1998; Thompson, 2024). It affords them ways of looking at the world that give them a sense of purpose (Froese, 2016; Smith, 2003). Thus, it is likely that some or perhaps many of those who did not succumb to (or overcame) the despair around them by embracing a way of looking at the world, Christian nationalism, that offered them a sense of purpose, meaning, and belonging. This could also help account for the strong positive association between regular church attendance and Christian nationalist sentiments we saw above.

In 2016, 59 percent of rural voters voted for Donald Trump; only 34 percent voted for Hillary Clinton (Pew Research Center, 2018). Accordingly, a popular explanation of the current political climate and support for Donald Trump is the rural–urban divide, and it is not a coincidence that many rural counties in the U.S. are among the “left behind.”12 Importantly, though, rural voters do not feel as if they have only been left behind demographically and economically. Many living in rural communities believe their way of life is disappearing and that small-town values and a sense of community are becoming a thing of the past. Moreover, many feel as if they are under attack from liberal and cultural elites. That is, except for perhaps in a romantic (e.g., Hallmark movies) or nostalgic sense (e.g., weekend escapes), the perception among rural Americans is that cultural elites—Schleiermacher’s (1893) “cultured despisers”—regard small-town America with barely-concealed contempt. They view rural Americans as uneducated and backward, holding beliefs that anyone with an ounce of intelligence would reject. Finally, many rural Americans believe that Washington (i.e., the federal government) is broken. It lacks common sense and is tone-deaf about the needs and wants of rural America. Add to this the perception that Washington is in league with cultural elites to force liberal values down their throats (what some might term “legislating morality”), and it is easy to see why many small-town Americans found the norm-breaking, liberal-elite hating Donald Trump appealing (Hochschild, 2016; Vance, 2016). Wuthnow (2018) has captured rural America’s frustrations in his book, The Left Behind: Decline and Rage in Rural America:13

People up there in Washington, does not matter what party it is, those people do not know a thing about what’s going on down here in Gulfdale. They do not want to listen to us. They do not care! (p. 97).

Those people up there in Washington, they think they know more than we do. They treat us like second-class citizens, like we are dumb hicks, like we do not know what’s going on (pp. 97–98).

They’re just not listening to us out here (pp. 98–99).

Do not forget us… Maybe our population is not as big as cities, but we represent something cities never will (p. 99).

Do not assume I’m stupid and do not know anything just because I’m a farmer! (p. 103).

[Washington’s] a money-hungry, dog-eat-dog place. Lobbyists are ruining it, and it’s just gone to pot. We just need somebody with a little gumption. Somebody to go up there and do what a common man knows to do. That’s all we need! (p. 107).

As we saw above, though, individuals living in rural areas are not likelier to express Christian nationalist attitudes. A subset of rural Americans may be, however. Table 8 considers this possibility. It shows the proportion of Americans living in rural areas (16.29%), the proportion of Americans living in the rural U.S. who identify as evangelical Protestant (6.86%), the proportion living in the rural U.S. and lack a college degree (12.73%), and the proportion living in the rural U.S. who identify as evangelical Protestant and lack a college degree (5.76%). It also indicates the percentage classified as Christian nationalists for each category. As it shows, the lack of a college degree has little effect on Christian nationalist attitudes, but identifying as an evangelical has a large one. The proportion of evangelical, rural Americans who we can classify as Christian nationalists is almost double that of all rural Americans. Still, this group represents, at most, 4 % of Americans (6.86% x 60.30%) and a third of all Christian nationalists (see Table 2). Rural Americans who feel left behind may find Christian nationalism appealing, but by themselves, they do not account for all Americans sympathetic to Christian nationalism.

Sandel (2020) traces the condescending view that some cultural elites have for working-class Americans to what he calls the “tyranny of merit” or, perhaps better, the “politics of humiliation.” Sandel’s focus is on the anger of those who voted for Trump:

It is a mistake to see only the bigotry in populist protest, or to view it only as an economic complaint… the election of Donald Trump… was an angry verdict on decades of rising inequality and a version of globalization that benefits those at the top but leaves ordinary citizens feeling disempowered. It was also a rebuke for a technocratic approach to politics that is tone-deaf to the resentments of people who feel the economy and the culture have left them behind… these grievances are not only economic but also moral and cultural; they are not only about wages and jobs but also about social esteem (Sandel, 2020, p. 17, 18, emphasis added).

Sandel locates these grievances in the technocratic conception of the public good and its corresponding meritocratic ethic. The former is “bound up with a faith in… the… belief that market mechanisms are the primary instruments for achieving the public good” (Sandel, 2020, pp. 19–20). According to Sandel, market-driven globalization has generated increasing inequality and devalued national identities. Those who benefit from it have “valorized cosmopolitan identities as a progressive, enlightened alternative to the narrow parochial ways of protectionism, tribalism, and conflict” (Sandel, 2020, p. 20). He argues that by 2016, the Democratic Party had become the party of technocratic liberalism, which reflects more the interests of professional elites than blue-collar and middle-class voters.

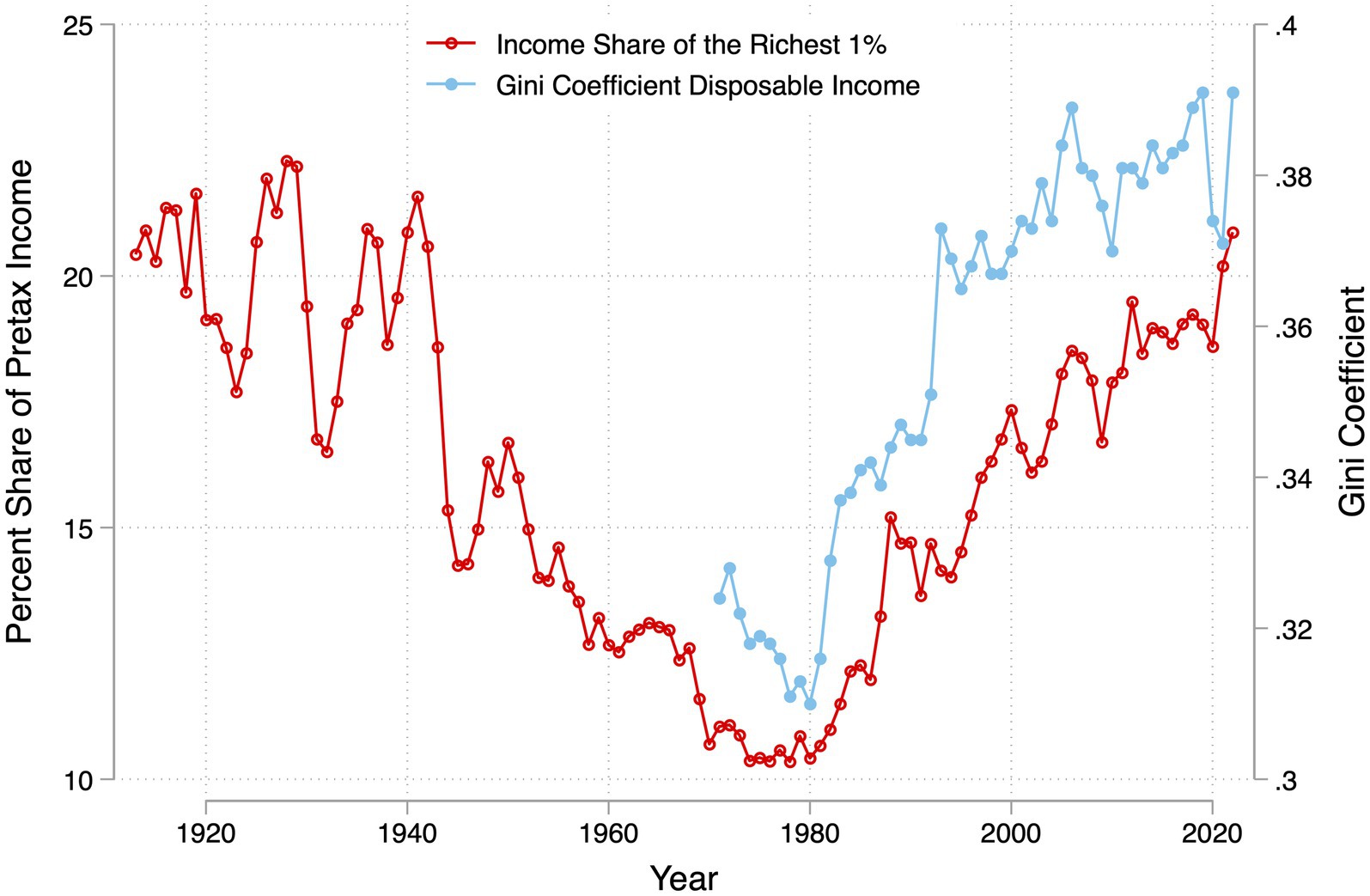

Sandel contends that technocratic liberalism frequently employs a “rhetoric of rising” that holds that people “who work hard and play by the rules” should rise as far as “their talents will take them.” The issue, of course, is that not everyone can make it, not even those who try and play by the rules. Take, for example, Figures 2, 3. Figure 2 plots two measures of income inequality in the U.S: The income share of the wealthiest 1 % of pretax income from 1913 to 2022 (World Inequality Database, 2024) and the Gini coefficient of U.S. disposable income from 1970 to 2022 (Luxembourg Income Study, 2024). Both plots suggest that inequality has increased since the early 1980s.

Figure 2. Income inequality in the United States, 1913-2022 (Luxembourg Income Study, 2024).

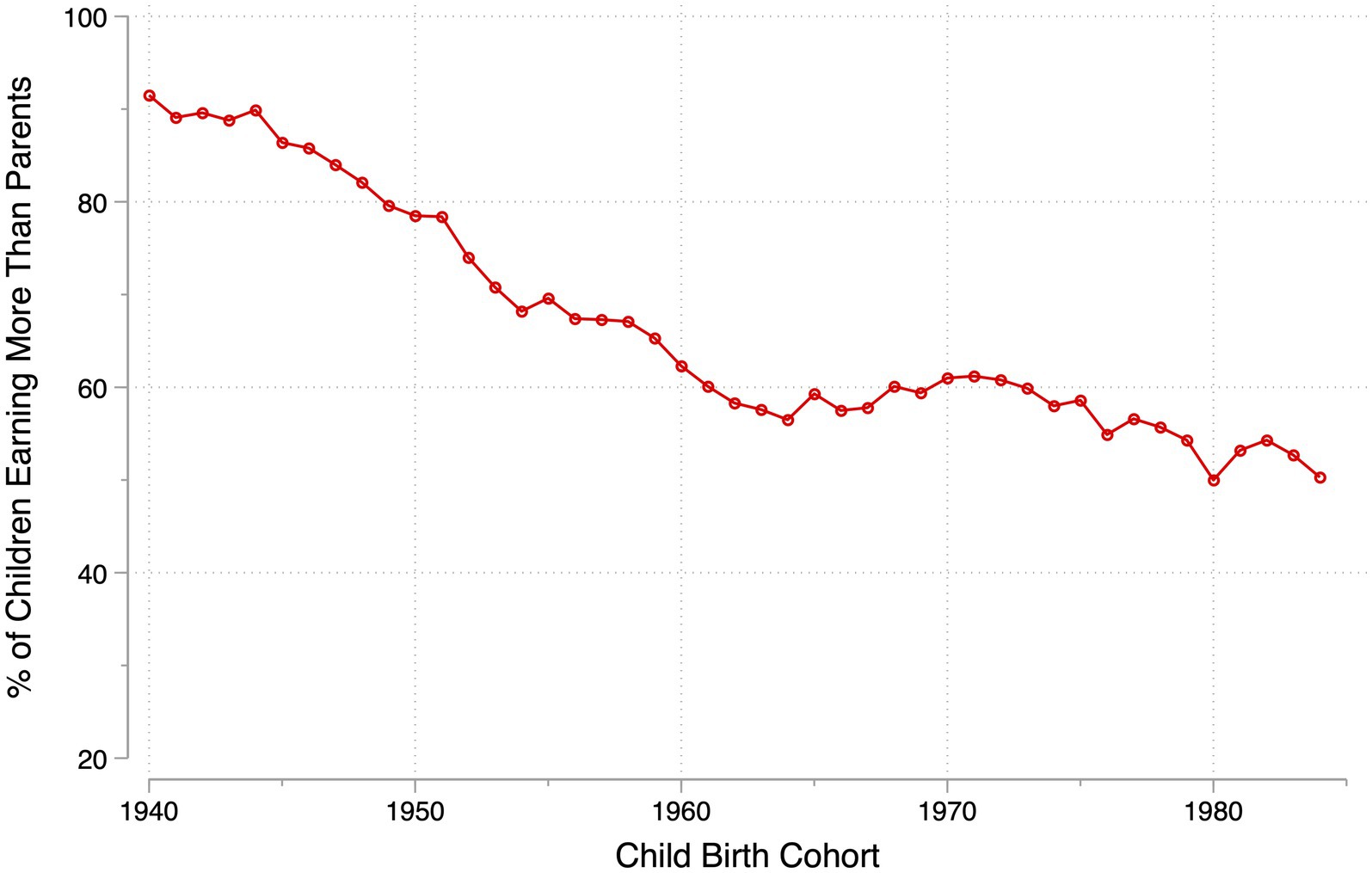

Figure 3. Percentage of children earning more than parents by birth cohort, 1940–1984 (Chetty et al., 2017; Opportunity Insights, 2016).

Now, consider Figure 3. It plots mobility rates by birth cohort (Opportunity Insights, 2016; Chetty et al., 2017). Specifically, the y-axis represents the percentage of children who make more than their parents, and the x-axis indicates the year someone was born. It clearly shows that the dream that children born in America will have a higher standard of living than their parents has become less and less likely. None of the plots in the two figures “prove” Sandel’s thesis. They are, however, consistent with it.

The meritocratic ethic that accompanies technocratic liberalism implicitly holds that those endowed with the gifts our market society rewards deserve more esteem than those who do not possess such talents:

Among the winners, it generates hubris; among the losers, humiliation and resentment. These moral sentiments are at the heart of the populist uprising against elites. More than a protest against immigrants and outsourcing, the populist complaint is about the tyranny of merit. And the complaint is justified… Meritocratic hubris leads winners to “inhale too deeply of their success… It is the smug conviction… that they deserve their fate, and that those on the bottom deserve theirs too. This attitude is the moral companion of technocratic politics.” (Sandel, 2020, p. 25).

We see evidence for such an attitude in how the media portrays technocratic liberalism’s winners and losers. One study found that television shows portray blue-collar dads as stupid, impotent, and the butt of jokes (e.g., Archie Bunker and Homer Simpson). By contrast, they paint upper-middle-class and professional dads in a favorable light (Sandel, 2020). It is no wonder that some have criticized “the class-cluelessness” of progressive elites (Williams, 2017). And it should be no surprise that those on the receiving end of the smug contempt of many elites have embraced an identity that offers them a sense of self-worth and purpose. We have already seen that religious belief and practice excels at providing the faithful with a sense of meaning, belonging, and purpose (Smith, 2003; Smith, 2017; Smith et al., 1998; Thompson, 2024; Froese, 2016). Thus, it is unsurprising that some will find a narrative that blends religious faith with national pride appealing.14

A final factor worth considering is the appeal of nationalist sentiments, a product of a natural desire to be part of something greater. Although a handful of philosophers may have proclaimed the death of “grand narratives,” the rest of the world, or at least most of it, was not listening. Grand narratives are alive and well. Scholars of all stripes have concluded that people experience the world in terms of narratives: literary critics (Kermode, 1980; Morson, 1994), historians (White, 1980; Mink, 1978), philosophers (Ricoeur, 1984-1988; Macintyre, 1984), religious scholars (Crites, 1971; Ganzevoort et al., 2013), theologians (Gerkin, 1984; Hauerwas, 1981), psychologists (Polkinghorne, 1988; Sarbin, 1986), anthropologists (Hill, 2005; Reck, 1983), sociologists (White, 2008; Somers, 1994; Tilly, 2002; Polletta et al., 2011), political scientists (Patterson and Monroe, 1998; Miller, 2022), and economists (Morson, 2017; Shiller, 2019). As the political scientist Miller (2022, p. 230) puts it, “We cannot escape some kind of overarching story of who ‘we’ are, a story that gives us meaning, purpose, and direction:”

Nationalism provides people with a fervent sense of belonging. Countries do not hold together because citizens make a cold assessment that it’s in their self-interest to do so. Countries are held together by shared loves for a particular way of life, a particular culture, a particular land. These loves have to be stirred in the heart before they can be analyzed by the brain. Nationalism provides people with a sense of meaning. Nationalists tell stories that stretch from a glorious, if broken, past forward to a golden future. Individuals live and die, but the nation goes on. People feel their life has significance because they contribute to these eternal stories (Brooks, 2022).

To pretend that most people are not attracted to transcendent stories only creates a vacuum that someone or something will fill:

It would be a tragedy if nationalism—with its tremendous creative and productive powers—were left in the hands of extremists. Open-minded liberal democrats, social democrats, and justice-seeking individuals must learn to harness nationalism to their cause, creating a more just social order, closing socio-economic gaps, while providing people with a cultural and normative reference to live by Tamir (2019, pp. 181–182).

In other words, the question is not whether people will be drawn to a nationalist narrative. It is a question of which one. For instance, Reno (2019) has recently argued that the recent rise of nationalism is a reaction to “the post-war consensus,” the quest for what Karl Popper called the “open society” where there are no transcendent truths (i.e., “grand narratives”) but only private interests. He claims that an increasing number of people have rejected the open society’s “weak gods” and have sought a return of strong ones. “The sacralizing impulse in public life is inevitable. Our social consensus always reaches for transcendent legitimacy” (Reno, 2019, p. 136). As such, he argues that we should embrace nationalism because it gives our lives a sense of meaning, purpose, and belonging:

The strong god of the nation draws us out of our “little worlds.” Our shared loves—love of our land, our history, our founding myths, our warriors and our heroes—raise us to a higher vantage point. We see our private interest as part of a larger whole, the “we” that calls upon our freedom to serve the body politic with intelligence and loyalty. As Aristotle recognized, this loyalty is intrinsically fulfilling, for it satisfies the human desire for transcendence (Reno, 2019, p. 155).

Reno contends that we should resist open society’s “globalist utopianism” and instead cultivate healthy forms of strong gods while resisting those that lead to “militarism, totalitarian regimes, and vicious racial segregation” (Reno, 2019, p. 147). Only by attending “to the strong gods who come from above and animate the best of our traditions” will we be able to turn away from “the dark gods that rise up from below” (Reno, 2019, p. 162). Yascha Mounk makes a similar point. While celebrating the diversity of modern society, he argues on behalf of a “cultural patriotism” that can balance the “centrifugal forces” that diversity can set loose (Brooks, 2022). “Historically, it has played a significant role in extending the circle of our sympathy beyond our own family, our own village, and our own tribe… For diverse democracies to thrive, their citizens need to share a common identity. Without some sense of inclusive patriotism, they are condemned forever to regard one another as strangers or adversaries” (Mounk, 2022, p. 146–147).

The first three factors highlight the experiences related to feeling as if one has fallen behind, a sense of despair, anger, and humiliation. Their interaction can lead people to embrace strongmen who promise to make all things right:

Authoritarians rise when economic, social, political, or religious change makes members of a formerly powerful group feel as if they have been left behind. Their frustration makes them vulnerable to leaders who promise to make them dominant again. A strongman downplays the real conditions that have created their problems and tells them that the only reason they have been dispossessed is that enemies have cheated them of power (Richardson, 2023:xii).

Their interaction can also increase the appeal of narratives that promise to restore a mythic past, what Reno calls “the strong gods.” Christian nationalism is one such narrative. But there are alternatives (Bellah, 1967; Bellah, 1970; Gorski, 2017; Gorski, 2021; Burton, 2020). Not all forms of nationalism are toxic. Not all “rise up from below.” Some tell a much different story. Some tell stories that are forward-looking and inclusive while at the same time providing citizens with a sense of direction, meaning, and belonging (Mounk, 2018; Mounk, 2022; Tamir, 1993; Tamir, 2019). These are the stories that need to be told.

This paper has explored potential predictors of Christian nationalist sentiments. Using three different schemes for identifying Christian nationalists and estimating a series of multivariate logistic regression models, it found that Americans who are older, identify as a conservative or a Republican, believe the Bible is literally true, and attend church frequently are more likely to embrace Christian nationalism, while Black Protestants, Roman Catholics, people of non-Christian faiths, and the unaffiliated are less likely. Most notably, race and ethnicity do not affect whether someone expresses Christian nationalist attitudes, at least not in expected ways. Indeed, in the models using the Smith and Adler LCA classification scheme, African American respondents are more (not less) likely than non-Hispanic white respondents to be classified as Christian nationalists, a result that should, at a minimum, give us pause. More importantly, though, in all three sets of models, non-Hispanic white respondents are not more likely than respondents who identify as Black, Hispanic, Asian, or another race or ethnicity to be classified as Christian nationalists.

All studies have their limitations, and this one is no exception. In fact, it has already highlighted one such limitation: cross-sectional survey data cannot capture all possible factors that lead some to find Christian nationalism appealing. In light of this, it briefly explored four factors that may have contributed to the recent (re)emergence of Christian nationalism in the U.S. All four deserve more detailed and systematic analyses, in particular, ones that definitively demonstrate whether a tie between any or all of the four factors and Christian nationalism exists. Needless to say, these four do not exhaust the possible causes of Christian nationalism, but it will be up to others to tease out what those might be. Another limitation is the paper’s reliance on a single survey. Other surveys with potentially “better” questions exist (Gorski and Perry, 2022; Perry et al., 2023), and an analysis of them may yield different results from those here (e.g., finding that White respondents are likelier to embrace Christian nationalism). Notably, though, studies that have used these surveys have created a scale similar to Whitehead and Perry’s, raising many of the same methodological concerns discussed earlier. To better test whether American Christian nationalism is coded to promote white racism, future studies can take a lead from the suggestion of Li and Froese (2023, p. 793): create a survey item that specifically asks respondents if America would be a better nation if the federal government declared it a white Christian nation.

Nothing in this study should be interpreted to suggest that white Christian nationalism is a myth. It is not, and some white Christian nationalists have few, if any, qualms about using violence to achieve political ends (Hoffman and Ware, 2024). Instead, what the results suggest is that we should view white Christian nationalism as a subset of those who express Christian nationalist sentiments. How large or how small this subset may be is difficult to determine. It is probably larger than the 1 % of Americans classified as Christian nationalists who express support for white nationalism, but it certainly does not include the 15 to 20 percent who harbor Christian nationalist views. Unfortunately, the portion of the 15 to 20 percent who are not white Christian nationalists are often lumped together with those who are and then unfairly (unhelpfully) labeled racist. A better strategy for those concerned about Christian nationalism’s potentially harmful influence would be to address the underlying dynamics that have given rise to Christian nationalism. Here, we have considered four—the feeling of being economically and culturally left behind, the hubris of those who have benefitted from technocratic liberalism, the loss of purpose and the rise in deaths of despair, and the appeal of transcendent stories like nationalism—but there are almost certainly others. Indeed, until factors such as these are addressed, it is likely that the dark gods will continue to rise up from below.

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://www.thearda.com/data-archive?fid=BRS2021.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the patients/ participants or patients/participants' legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

SE: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The views expressed in this document are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^All three schemes draw on answers to the questions in Table 1 in the 2017 and 2021 Baylor Religion Surveys. They are discussed in detail in the next section.

2. ^Smith and Adler cite Davis’s analysis although their article was published in 2022 and Davis’s (2023). This apparent discrepancy is accounted for by the fact that Davis’s article was first published online in 2022.

3. ^Davis (2023: footnote 14, p. 20) notes that the fit statistics presented in Appendix Table A2 (p. 23) indicate that, like Adler and Smith, a six-class solution provides the best fit. However, since the difference in fit between the four- and six-class solutions is “modest,” he uses four-class solution to facilitate comparison with Whitehead and Perry’s four categories.

4. ^This is what they found when analyzing waves of the BRS. However, their analysis the 2021 Pew American Trends Panel found that the belief that “God favors the United States” does load with Christian statism (Li and Froese, 2023:782).

5. ^Davis’s (2023) factor analysis of the 2017 BRS yields the same result. See also Braunstein (2021).

6. ^Davis (2023:17-18) suggests a similar solution.

7. ^Using Smith and Adler’s Stata code, graciously shared by Jesse Smith, I first replicated their analysis of the 2017 BRS and then analyzed the 2021 BRS. It, too, yielded a six-class solution.

8. ^MI avoids the statistical pitfalls of other methods for handling missing data (Carpenter and Kenward, 2013; Rubin, 1987; Rubin, 1996; Schafer, 1997; Enders, 2010; Statacorp, 2015, pp. 3–4). I generated 30 imputations for each case with missing information and then averaged them together before estimating the models.

9. ^Results for models without sampling weights and including imputed information on the dependent variables are available upon request. Results for models that do not include imputed information are also available.

10. ^Notably, the decline has occurred primarily in terms of participation not belief (Levin et al., 2022).

11. ^Social support ranges from spiritual support (confirmation of religious beliefs) to emotional comfort (it is easier to bear an illness or a depressing event in the company of friends than alone), and to material aid (e.g., goods and services, such as providing people with meals when sick or in distress).

12. ^According to Benzow (2024), of the 972 “left behind” counties, 873 are rural, 38 are exurban/suburban counties (not rural, not urban), 50 are small urban counties (metropolitan areas without a large city), and 11 are urban counties.

13. ^Wuthnow’s fieldwork (with help from his students) took him all over the United States and, as such, his book likely paints a relatively representative picture of rural Americans. Although it was published after the 2016 election, the fieldwork was conducted before.

14. ^This also helps account to the strong positive association between regular church attendance and Christian nationalist sentiments. Additionally, it may help explain the strong association between evangelical Protestantism and Christian nationalism. As some have noted, American evangelicalism has long associated “being a good Christian” with “being a good American” (Du Mez, 2020; Alberta, 2023).

Akaike, H. (1974). A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 19, 716–723. doi: 10.1109/TAC.1974.1100705

Alberta, T. (2023). The kingdom, the power, and the glory: American evangelicals in an age of extremism. New York, NY: Harper.

Anderson, B. (2016). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. London and New York: Verso.

Armaly, M. T., Buckley, D. T., and Enders, A. M. (2022). Christian nationalism and political violence: victimhood, racial identity, conspiracy, and support for the capitol attacks. Polit. Behav. 44, 937–960. doi: 10.1007/s11109-021-09758-y

Bader, C. D., Mencken, F. C., and Froese, P. (2007). American piety 2005: content and methods of the Baylor religion survey. J. Sci. Study Relig. 46, 447–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5906.2007.00371.x

Baker, J. O., Perry, S. L., and Whitehead, A. L. (2020). Keep America Christian (and White): Christian nationalism, fear of ethnoracial outsiders, and intention to vote for Donald Trump in the 2020 presidential election. Sociol. Relig. 81, 272–293. doi: 10.1093/socrel/sraa015

Beit-Hallahmi, B., and Argyle, M. (1997). The psychology of religious behavior, belief and experience. London: Routledge.

Bellah, R. N. (1970). Beyond belief: Essays on religion in a post-traditional world. New York: Harper & Row.

Benzow, A. (2024). Economic renaissance or fleeting recovery? Left-Behind Counties See Boom in Jobs and Businesses Amid Widening Divides. Economic Innovation Group [Online]. Available AT: https://eig.org/left-behind-places/ (Accessed July 8, 2024).

Bonikowski, B. (2016). Nationalism in settled times. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 42, 427–449. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-081715-074412

Bonikowski, B., and Dimaggio, P. (2016). Varieties of American popular nationalism. Am. Sociol. Rev. 81, 949–980. doi: 10.1177/0003122416663683

Bor, J. (2017). Diverging life expectancies and voting patterns in the 2016 us presidential election. Am. J. Public Health 107, 1560–1562. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303945

Braunstein, R. (2021). The “right” history: religion, race, and nostalgic stories of Christian America. Religion 12:95. doi: 10.3390/rel12020095

Brewer, M. B., and Pierce, K. P. (2005). Social identity complexity and outgroup tolerance. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 31, 428–437. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271710

Brooks, D. (2018). A generation emerging from the wreckage. The New York Times [Online]. Available AT: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/26/opinion/millennials-college-hopeful.html?smid=pl-share [Accessed May 15, 2023].

Brooks, D. (2022). The triumph of the Ukrainian idea. The New York Times [Online]. Available AT: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/06/opinion/ukraine-liberal-nationalism.html [Accessed May 15, 2023].

Burton, T. I. (2020). Strange rites: New religions for a godless world. New York, NY: Public Affairs (Hachette Book Group).

Butler, A. (2022). “What is White Christian nationalism?” in Christian nationalism and the January 6, 2021 insurrection. ed. A. Tyler (Washington D.C.: Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty (Bjc) and Freedom From Religion Foundation (Ffrf)).

Carpenter, J., and Kenward, M. G. (2013). Multiple imputation and its application. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Case, A., and Deaton, A. (2015). Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among White non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 15078–15083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518393112

Case, A., and Deaton, A. (2020). Deaths of despair and the future of capitalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Chetty, R., Grusky, D., Hell, M., Hendren, N., Manduca, R., and Narang, J. (2017). The fading American dream: trends in absolute income mobility since 1940. Science 356, 398–406. doi: 10.1126/science.aal4617

Corcoran, K. E., Scheitle, C. P., and Digregorio, B. D. (2021). Christian nationalism and Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy and uptake. Vaccine 39, 6614–6621. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.09.074

Crites, S. (1971). The narrative quality of experience. J. Am. Acad. Relig. Xxxix, 291–311. doi: 10.1093/jaarel/XXXIX.3.291

Davis, N. T. (2023). The psychometric properties of the Christian nationalism scale. Politics Religion 16, 1–26. doi: 10.1017/S1755048322000256

Davis, J. T., Perry, S. L., and Grubbs, J. B. (2023). Liberty for us, limits for them: Christian nationalism and Americans’ Views on Citizens’ Rights. Sociology of Religion.

Du Mez, K. K. (2020). Jesus and John Wayne: How White evangelicals corrupted a faith and fractured a nation. New York, NY: Liveright Publishing Corporation.

Ellison, C. G., and George, L. K. (1994). Religious involvement, social ties, and social support in a southeastern community. J. Sci. Study Relig. 33, 46–61. doi: 10.2307/1386636

Finke, R., and Stark, R. (2005). The churching of America, 1776–2005: Winners and losers in our religious economy. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Flannelly, K. J., Weaver, A. J., Larson, D. B., and Koenig, H. G. (2002). A review of mortality research on clergy and other religious professionals. J. Relig. Health 41, 57–68. doi: 10.1023/A:1015158122507

Froese, P. (2016). On purpose: How we create the meaning of life. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Froese, P., and Mencken, F. C. (2009). A U.S. holy war? The effects of religion on Iraq war policy attitudes. Soc. Sci. Q. 90, 103–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2009.00605.x

Ganzevoort, R. R., Hardt, M., and Scherer-Rath, M. (2013). Religious stories we live by: Narrative approaches in theology and religious studies. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers.

Gerkin, C. V. (1984). The living human document: Re-visioning pastoral counseling in a hermeneutical mode. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press.

Giles, T., Hungerman, D. M., and Oostrom, T. (2023). Opiates of the masses? Deaths of despair and the decline of American religion. Nber Working Paper. pp. 1–38.

Goldman, L., Lim, M. P., Chen, Q., Jin, P., Muennig, P., and Vagelos, A. (2019). Independent relationship of changes in death rates with changes in us presidential voting. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 34, 363–371. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4568-6

Gorski, P. S. (2017). American covenant: A history of civil religion from the puritans to the present. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Gorski, P. S. (2020). American Babylon: Christianity and democracy before and after trump. New York, NY: Routledge.

Gorski, P. S. (2021). “The past and future of the American civil religion” in Civil religion today: Religion and the American nation in the twenty-first century. eds. R. H. Williams, R. Haberski Jr., and P. Goff (New York, NY: New York University Press).

Gorski, P. S., and Perry, S. L. (2022). The flag and the cross: White Christian nationalism and the threat to American democracy. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Hadden, J. K. (1987). Toward desacralizing secularization theory. Soc. Forces 65, 587–611. doi: 10.2307/2578520

Hauerwas, S. (1981). A Community of Character: Toward a constructive Christian social ethic. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame.

Hill, J. H. (2005). “Finding culture in narrative” in Finding culture in talk: A collection of methods. ed. N. Quinn (New York: Palgrave Macmillan US).

Hochschild, A. R. (2016). Strangers in their own land: Anger and mourning on the American right. New York, NY: The New Press.

Hummer, R. A., Ellison, C. G., Rogers, R. G., Moulton, B. E., and Romero, R. R. (2004). Religious involvement and adult mortality in the United States: review and perspective. South. Med. J. 97, 1223–1230. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000146547.03382.94

Hummer, R. A., Rogers, R. G., Nam, C. B., and Ellison, C. G. (1999). Religious involvement and U.S. adult mortality. Demography 36, 273–285. doi: 10.2307/2648114

Jones, R. P. (2021). White too long: The legacy of White supremacy in American Christianity. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Jones, R. P. (2023). The hidden roots of White supremacy: And the path to a shared American future. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Kaylor, B., and Underwood, B. (2023). How mainline Protestants help build Christian nationalism. Religion & Politics [Online]. Available AT: https://religionandpolitics.org/2023/01/04/how-mainline-protestants-help-build-christian-nationalism/ [Accessed June 13, 2024].

Kaylor, B., and Underwood, B. (2024). Baptizing America: How mainline Protestants helped build Christian nationalism. Des Peres, MO: Chalice Press.

Koenig, H. G., Mccullough, M. E., and Larson, D. B. (2001). Handbook of religion and health. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Levin, J. S. (1994). Religion and health: is there an association, is it valid, and is it causal? Soc. Sci. Med. 38, 1475–1482. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90109-0

Levin, J. S. (2016). For they knew not what it was": rethinking the tacit narrative history of religion and Health Research. J. Relig. Health 56, 28–46. doi: 10.1007/s10943-016-0325-5

Levin, J. S., Bradshaw, M., Johnson, B. R., and Stark, R. (2022). Are religious ‘Nones’ really not religious?: revisiting Glenn, three decades later. Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion [Online], 18. Available at: https://www.religjournal.com/articles/article_view.php?id=169 (Accessed August 15, 2022).

Li, R., and Froese, P. (2023). The duality of American Christian nationalism: religious traditionalism versus Christian Statism. J. Sci. Study Relig. 62, 770–801. doi: 10.1111/jssr.12868

Luxembourg Income Study (2024). Gini Coefficient (After Tax). Luxembourg Income Study (with major processing by Our World in Data) [Online]. Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/explorers/inequality-lis?tab=chart&facet=none&country=~Usa&Indicator=Gini+coefficient&Income+measure=After+tax&Adjust+for+cost+sharing+within+households+%28equivalized+income%29=false [Accessed June 26, 2024].

Macintyre, A. (1984). After virtue: A study in moral theory. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press.

Marantz, A. (2022). Does Hungary offer a glimpse of our authoritarian future. The New Yorker [Online]. Available at: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/07/04/does-hungary-offer-a-glimpse-of-our-authoritarian-future [Accessed September 7, 2024].

Miller, P. D. (2022). The religion of American greatness: What’s wrong with Christian nationalism. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press.

Miller, K. P., Brewer, M. B., and Arbuckle, N. L. (2009). Social identity complexity: its correlates and antecedents. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 12, 79–94. doi: 10.1177/1368430208098778

Mink, L. O. (1978). “Narrative form as a cognitive instrument” in The writing of history: Literary form and historical understanding. eds. R. H. Canary and H. Kozicki (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press).

Morson, G. S. (2017). Cents and sensibility: What economics can learn from the humanities. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Mounk, Y. (2018). How liberals can reclaim nationalism. The New York Times [Online]. Available AT: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/03/opinion/sunday/liberals-reclaim-nationalism.html?smid=pl-share (Accessed August 15, 2022).

Mounk, Y. (2022). The great experiment: Why diverse democracies fall apart and how they can endure. New York, NY: Penguin Random House.

Nie, F. (2024). In god we distrust: Christian nationalism and anti-atheist attitude. J. Sci. Study Relig. 63, 103–116. doi: 10.1111/jssr.12886

Opportunity Insights. (2016). Fading American dream: baseline estimates of absolute mobility by parent income percentile and child birth cohort. Opportunity Insights [Online]. Available AT: https://opportunityinsights.org/data/?geographic_level=0&topic=0&paper_id=546#resource-listing [Accessed June 26, 2024].

Pargament, K. I., and Park, C. L. (1995). Merely a defense? The variety of religious means and ends. J. Soc. Issues 51, 13–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1995.tb01321.x

Pargament, K. I., Smith, B. W., Koenig, H. G., and Perez, L. (1998). Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. J. Sci. Study Relig. 37, 710–724. doi: 10.2307/1388152

Patterson, M., and Monroe, K. R. (1998). Narrative in political science. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 1, 315–331. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.1.1.315

Perry, S. L., and Whitehead, A. L. (2015). Christian nationalism and White racial boundaries: examining Whites' opposition to interracial marriage. Ethn. Racial Stud. 38, 1671–1689. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2015.1015584

Perry, S. L., Whitehead, A. L., and Grubbs, J. B. (2020). Culture wars and Covid-19 conduct: Christian nationalism, religiosity, and Americans’ behavior during the coronavirus pandemic. J. Sci. Study Relig. 59, 405–416. doi: 10.1111/jssr.12677

Perry, S. L., Whitehead, A. L., and Grubbs, J. B. (2022). “I Don’t want everybody to vote”: Christian nationalism and restricting voter access in the United States. Sociol. Forum 37, 4–26. doi: 10.1111/socf.12776

Perry, S. L., Whitehead, A. L., and Grubbs, J. B. (2023). Race over religion: Christian nationalism and perceived threats to National Unity. Sociol. Race Ethn. 23326492231160530. doi: 10.1177/23326492231160530

Pew Research Center (2018). For Most trump voters, ‘very warm’ feelings for him endured. Washington D.C.: Pew Research Center.

Polkinghorne, D. E. (1988). Narrative knowing and the human sciences. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Polletta, F., Chen, P. C. B., Gardner, B. G., and Motes, A. (2011). The sociology of storytelling. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 37, 109–130. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-081309-150106

Reno, R. R. (2019). Return of the strong gods: Nationalism, populism, and the future of the west. Regnery Gateway: Washington D.C.

Roccas, S., and Brewer, M. B. (2002). Social identity complexity. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 6, 88–106. doi: 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0602_01

Rubin, D. B. (1996). Multiple imputation after 18+ years. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 91, 473–489. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1996.10476908

Sandel, M. J. (2020). The tyranny of merit: What’s become of the common good? New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Sarbin, T. R. (1986). Narrative psychology: The storied nature of human conduct. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

Schildkraut, D. J. (2002). The more things change… American identity and mass and elite responses to 9/11. Polit. Psychol. 23, 511–535. doi: 10.1111/0162-895X.00296

Schildkraut, D. J. (2011). Americanism in the twenty-first century: Public opinion in the age of immigration. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Schleiermacher, F. (1893). On religion: Speeches to its cultured despisers. London, UK: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., Ltd.

Shiller, R. J. (2019). Narrative economics: How stories go viral and drive major economic events. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Smith, R. (1997a). Americanism in the twenty-first century: Public opinion in the age of immigration. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Smith, R. (1997b). Civic ideals: Conflicting visions of American citizenship in U.S. history. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Smith, C. S. (2003). Moral, believing animals: Human personhood and culture. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Smith, C. S. (2017). Religion: What it is, how it works, and why it matters. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Smith, J., and Adler, G. J. (2022). What Isn’t Christian nationalism? A call for conceptual and empirical splitting. Socius 8:23780231221124492. doi: 10.1177/23780231221124492

Smith, C. S., Emerson, M. O., Gallagher, S., Kennedy, P., and Sikkink, D. (1998). American evangelicalism: Embattled and thriving. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Somers, M. R. (1994). The narrative constitution of identity: a relational and network approach. Theory Soc. 23, 605–649. doi: 10.1007/BF00992905

Stark, R., and Iannaccone, L. R. (1994). A supply-side reinterpretation of the 'Secularization' of Europe. J. Sci. Study Relig. 33, 230–252. doi: 10.2307/1386688

Stewart, K. (2020). The power worshippers: Inside the dangerous rise of religious nationalism. London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Stewart, K. (2022). “Network of Christian nationalism leading up to January 6” in Christian nationalism and the January 6, 2021 insurrection. ed. A. Tyler (Washington D.C.: Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty (Bjc) and Freedom From Religion Foundation (Ffrf)).

Thompson, D. (2024). The true cost of the churchgoing bust. The Atlantic [Online]. Available AT: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2024/04/america-religion-decline-non-affiliated/677951/ [Accessed April 7, 2024].

Tisby, J. (2019). The color of compromise: The truth about the American Church’s complicity in racism. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan.

Tisby, J. (2022). “The patriotic witness of black Christians” in Christian nationalism and the January 6, 2021 insurrection. ed. A. Tyler (Washington D.C.: Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty (Bjc) and Freedom From Religion Foundation (Ffrf)).

Tyler, A. (2022). “Christian responses to Christian nationalism after January 6” in Christian nationalism and the January 6, 2021 insurrection. ed. A. Tyler (Washington D.C.: Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty (Bjc) and Freedom From Religion Foundation (Ffrf)).

U.S. Surgeon General of The United States (2023). “Our epidemic of loneliness and isolation: the U.S” in Surgeon General’s advisory on the healing effects of social connection and community (Washington D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services).