In recent years, discussions about the binary nature of gender/sex have flourished in both academic and public spaces. The gender/sex binary is the longstanding and deeply ingrained (at least in modern Western countries) belief system dictating that gender and sex are binary (i.e., women vs. men) and that gender follows directly from biological sex (Morgenroth and Ryan, 2021). However, challenges to the gender/sex binary have become more common in recent decades in the United States: transgender people—whose very existence challenges the notion that gender must follow from sex—have gained public visibility and certain legal rights such as the right to serve in the military and the right to be free from employment discrimination (Steinmetz, 2014; Totenberg, 2020; De Luce and Pettypiece, 2021), and nonbinary people—who identify as neither women nor men—have also gained visibility and certain legal rights such as the right to use a gender-neutral designation on driver's licenses and/or birth certificates in some states (Liszewski et al., 2018). However, much of the legal and social progress made toward transgender and nonbinary equality in recent years is at risk of actively being dismantled, evidenced by—for example—the rapid increase of anti-transgender legislation in the United States in recent years (Trans Legislation Tracker, 2024).

Social and cultural changes such as those described above often reverberate through our research in psychology. Though the field has a history of neglecting transgender and nonbinary populations or even actively harming transgender and nonbinary individuals by policing the boundaries of “normal” and “abnormal” gender identity and pathologizing nonconformity (Ansara and Hegarty, 2012; Tosh, 2016; Riggs et al., 2019), research on these topics is becoming more common (and more ethical). For example, clinical, counseling, and developmental psychologists have produced powerful research on trangender and nonbinary wellbeing (e.g., Simons et al., 2013; Olson et al., 2015, 2016; Connolly et al., 2016; Testa et al., 2017; McLemore, 2018; Tordoff et al., 2022). At the same time, in social psychology, Hyde et al. (2019) reviewed scholarship and activism that present challenges to the gender binary in a paper strengthened by interdisciplinary collaboration, Morgenroth and Ryan (2018) suggested ways for gender researchers to better reflect the complexities of gender, and Axt et al. (2021) developed a measure to study implicit attitudes toward transgender people.

Though transgender- and nonbinary-related research is becoming more common, whether such research possesses status and/or power is a different question. In this paper, we discuss whether, despite its increased frequency in social psychology, transgender and nonbinary-related research has not correspondingly become more common in our field's top, high-status journals. Similarly, we discuss how frequently research on these topics is awarded funding.

The extent to which marginalized topics and groups have been excluded by our science has been a frequent topic of conversation amongst psychologists in recent years, including in the context of race and ethnicity (Roberts et al., 2020; Thalmayer et al., 2021), nationality/location (Thalmayer et al., 2021), religion (Rios and Roth, 2020), sexual orientation (Lee and Crawford, 2012), and (binary) gender (Brown and Goh, 2016; Cikara et al., 2012; Rios and Roth, 2020). Our work adds to scholarship suggesting that psychology must do more to include both research on marginalized identities and researchers with marginalized identities, while expanding this conversation to include transgender and nonbinary identities.

Given the pivotal moment we currently occupy in the history of the struggle for transgender rights, research on these topics must not only be produced but also valued. One purpose of publishing research is to inform future research by other scientists and/or application in real-world contexts. If such research is rarely represented in the “top” journals in social psychology or funded by high status grants, the power of this work to inform research and application will be hindered.

Power and status in social psychology

While power and status have more commonly been discussed by social psychologists as qualities belonging to individuals or groups, they can also be possessed by institutions and structures (Kraus and Torrez, 2020). Status is defined as the prestige something has in the eyes of others, while power is control over resources and outcomes (Fiske, 2010; Blader and Chen, 2012; Fiske et al., 2016). Here, this means that editors (and, to some extent, reviewers) of top journals hold the power to confer status upon submitted research or not. The same applies to those making funding decisions.

Journals

Using PsycINFO, we analyzed the proportion of articles referring to transgender or nonbinary people published in some of social psychology's highest-status journals: Personality and Social Psychology Review [PSPR; impact factor (IF) = 10.8], Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (JPSP; IF = 7.6), Social Psychological and Personality Science (SPPS; IF = 5.7), and Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin (PSPB; IF = 4.0; Clarivate, 2024). We also searched for research related to other gender-related issues to determine whether status is withheld from research about gender more broadly or whether research conducted within the parameters of the gender/sex binary is valued more than research challenging them. To be clear, we do not mean to imply that research related to issues faced by women (e.g., Glick and Fiske, 1997; Reuben et al., 2014; Leskinen et al., 2015; Carli et al., 2016) and men (e.g., Vandello et al., 2008; Rudman and Mescher, 2013) is not important. After all, it is not just transgender and nonbinary populations who currently find their rights under threat; the overturning of Roe v. Wade in 2022 led to the loss of bodily autonomy for many women. Issues affecting binary, cisgender populations are important to study, but research on transgender and nonbinary populations should likewise be valued.

We also searched high status general psychology journals [Psychological Bulletin (IF = 22.4), American Psychologist (IF = 16.4), Psychological Science (IF = 8.2), and Journal of Experimental Psychology: General (JEP:G; IF = 4.1)] to assess whether these journals would follow similar patterns. Given social psychology's focus on social justice and inequality (Ross et al., 2010; Hammack, 2017), it may be the case that these issues are even more pronounced in psychology more broadly.

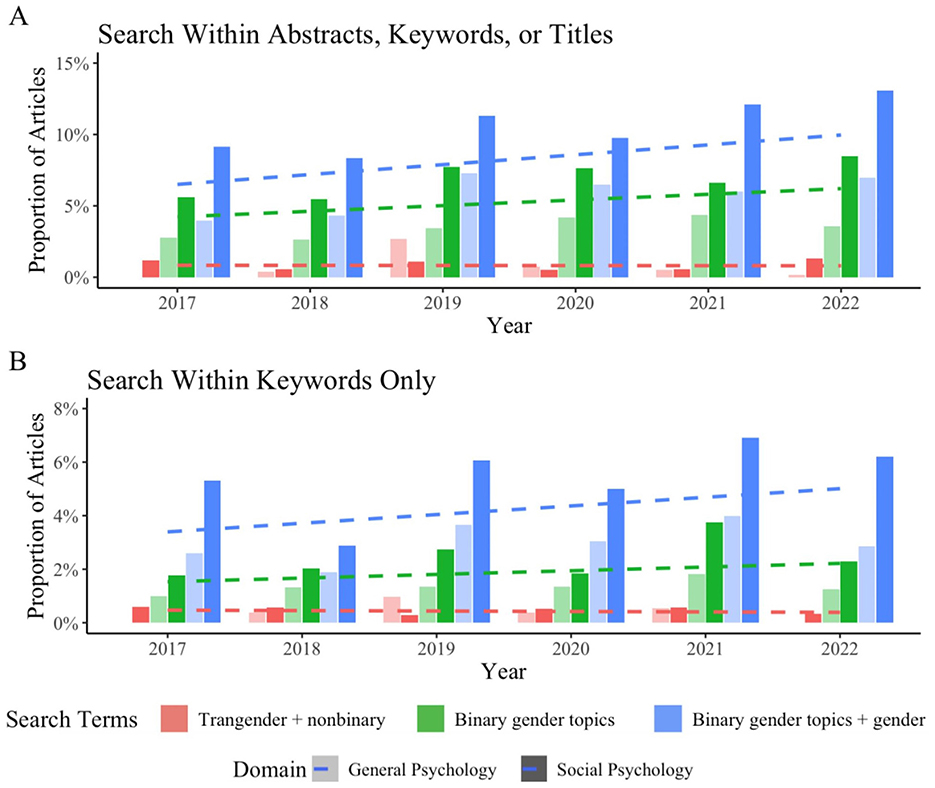

For each journal, we performed searches for the following terms, separated by the Boolean operator “OR”: transgender, trans, nonbinary, non-binary, gender minority, gender minorities, transphobia, gender binary, gender/sex binary, misgendering, androgyny, androgynous, agender, genderqueer, and gender fluid. The terms for the broader gender-related searches were: gender inequality, gender equality, sexism, gender bias, gender discrimination, gender stereotypes, gender roles, women, men, woman, man, masculinity, femininity, masculine, and feminine (i.e., “binary gender topics”). Additionally, we performed searches adding to this list “gender” and “gender identity” (i.e., “binary gender topics + gender”)—likely representing a wide variety of research at least somewhat related to gender.1 For all searches described above, we searched within (a) the abstracts, keywords, or titles of articles, and (b) the keywords of articles only. While the abstracts, keywords, and titles search was likely to return a wide variety of articles related to the search terms, we also wanted to include a narrower search within only the keywords of articles, which reflect the focus of the research.2 For each journal, we examined articles between 2017 and 2022 because most of the chosen journals did not publish any articles related to transgender or nonbinary populations prior to 2017, and for some journals (e.g., SPPS), PsycINFO listed no or very few articles published in 2023.

Within high-status social psychology journals, other gender-related topics and gender broadly were represented much more often than transgender and nonbinary topics. Searching within abstracts, keywords, or titles, the transgender/nonbinary search represented 0.00% (n = 0) of articles published between 2017 and 2022 in PSPR, 0.40% (n = 3) in JPSP, 1.40% (n = 8) in SPPS, and 1.02% (n = 7) in PSPB.3 In contrast, all of these journals published at least some research related to other gender-related topics or gender more generally, with our broadest search representing 9.52% (n = 6) of articles in PSPR, 10.89% (n = 81) in JPSP, 12.28% (n = 70) in SPPS, and 8.93% (n = 61) in PSPB (see Figure 1A).4 When searching within only keywords of the articles, proportions were even lower (see Figure 1B).

Among general psychology journals, we saw, for the most part, even more scarcity of transgender- and nonbinary-related research. The transgender/nonbinary search represented 0.00% (n = 0) of articles in Psychological Bulletin, 0.20% (n = 2) in Psychological Science, and 0.22% (n = 2) in JEP:G. Notably, 1.97% (n = 20) of American Psychologist articles met the search criteria, compared to 6.19% (n = 63) that met our broadest gender-related search. The majority of American Psyschologist's transgender- and nonbinary-related articles were published as part of a 2019 special issue titled, “Fifty Years Since Stonewall: The Science and Politics of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity.”

It also appears that the low representation of transgender- and nonbinary-related research in high-status journals is not simply a consequence of low output on these topics more generally. Across gender-related “specialty journals” like Psychology of Women Quarterly (PWQ), Sex Roles, Psychology and Sexuality, Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, and Men and Masculinities from 2017 to 2022, yearly proportions of articles meeting our transgender- and nonbinary-related search criteria within abstracts, keywords, or titles ranged from 12.79% (averaged across journals; 2017) to 26.01% (2022), much higher than the high status journals described above, though it should be noted that PWQ, Sex Roles, and Men and Masculinities had noticeably lower proportions than the other two journals (see OSF for data).

Funding

Funding agencies like the National Science Foundation (NSF) are another source of power within social psychology. These agencies and those who make funding decisions for them quite literally control the distribution of crucial resources for research. Being awarded competitive grants from agencies like the NSF also signifies high status, and allows researchers to conduct research with larger, more representative samples and more complicated designs, which are valued by social psychologists (Button et al., 2013; Hanel and Vione, 2016).

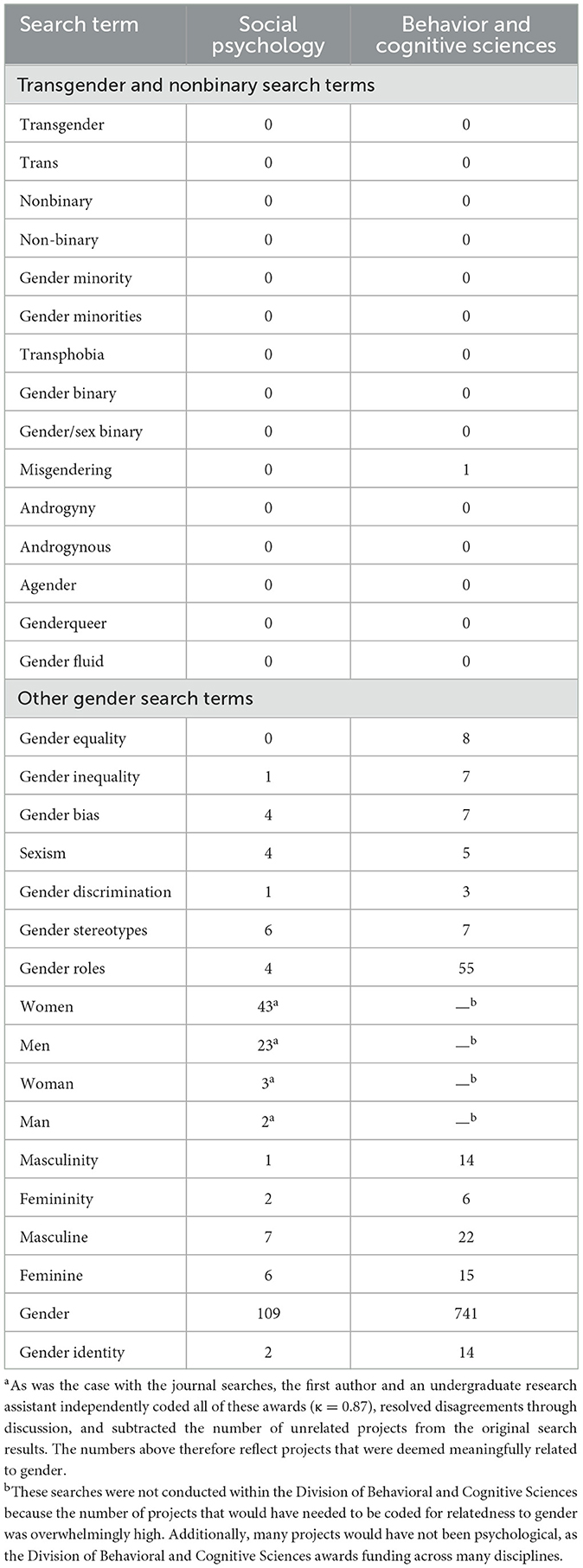

To analyze whether transgender- and nonbinary-related research occupies a low-status position in the context of funding, we searched for NSF awards using the same search terms as described above; however, because Boolean searching is not enabled on the NSF award search website, each term was entered separately. We searched within project abstracts and titles, as this is the only method possible through the NSF award search website. For each term, we performed two searches: within the Social Psychology program in the Division of Behavioral and Cognitive Sciences (BCS), and within BCS. Though these searches approximately mirror the social psychology and psychology journal searches described previously, BCS encompasses more than just psychological research, making it an even broader category. We searched for any active or expired awards, with no time limits on the dates. Within BCS, 470.17 awards were distributed on average per year between 2017 and 2022, while the average for the Social Psychology program was 26.67.

Zero awards matched any of the transgender- or nonbinary-related searches within the Social Psychology program, while one award in BCS included the term “misgendering.”5 In contrast, across both Social Psychology and BCS, a relatively large number of awards mentioned “gender” within their abstracts/titles while smaller but non-zero numbers of awards mentioned other gender-related terms within their abstracts/titles. While transgender- and nonbinary-related research has been funded by the NSF in other fields, it does not appear that any researchers have received NSF funds to study these topics through social psychological lenses. See Table 1 for results of the NSF award searches.

Discussion

Research on transgender and nonbinary populations becoming more common is an important first step in reckoning with psychology's historical marginalization of these communities and increasing our psychological understanding of these identities and gender more broadly. However, if research on these populations is not valued, the power of this important work to have theoretical and practical impacts will inevitably be constrained. The searches we performed demonstrate that, indeed, even if research related to transgender and nonbinary populations is becoming more common, this research is still lacking in status and power, as reflected by its rarity of publication in social psychology's highest status journals and its infrequency of NSF award funding.

The practical impacts of this work are especially important given the current challenges facing transgender and nonbinary communities, including legislation limiting transgender and nonbinary people's rights (Trans Legislation Tracker, 2024), stigmatization (White Hughto et al., 2015; Worthen, 2021; Valente et al., 2022), high rates of violence (Wirtz et al., 2020), and transgender and nonbinary identities being the subject of public debate (Friedersdorf, 2023; Mulvihill, 2023).

Additionally, the low status position of transgender- and nonbinary-related research likely contributes to the exclusion of transgender and nonbinary researchers. Settles et al. (2020) argue that the epistemic exclusion of topics related to marginalized populations harms marginalized researchers because (1) marginalized researchers are particularly likely to study these topics and (2) scholarship devaluation can be a covert way of expressing prejudice toward those belonging to marginalized groups. Thus, our results have implications for both the broad impact of research on these topics and for the inclusion of transgender and nonbinary psychological researchers.

One concrete way for journals to combat their scarcity of transgender- and nonbinary-related publications is to publish special issues on these topics. American Psychologist did just this in 2019, leading to this journal having the highest representation of transgender- and nonbinary-related articles of those we searched, and at the time of writing, they are putting together another transgender-related special issue (American Psychological Association, 2024). We encourage other high status journals to follow American Psychologist's lead in soliciting research on these under-valued yet important topics. In addition, improving the representation of transgender and nonbinary researchers and those who study these topics on editorial boards would likely have both direct (e.g., by placing transgender and nonbinary researchers in positions of power) and indirect (e.g., by demonstrating that journals value these topics and ensuring that people with expertise on topics relevant to transgender and nonbinary people are available to review related articles) effects on increasing the power and status of transgender and nonbinary research and researchers.

Some limitations should be kept in mind when reflecting on our results. First, we could not account for how many transgender- and nonbinary-related proposals and articles were submitted to the NSF and the journals in question. Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility that research on these topics is submitted less frequently and that those in power are accepting a substantial proportion of transgender- and nonbinary-related research that is submitted. However, even if this were the case, the reasons for low submission rates to these journals and NSF awards should be interrogated. If, for example, researchers of these topics are under the impression that their research is likely to be rejected from high-status journals or is unlikely to be funded by the NSF because it is regarded as “niche” or unimportant, this could still reflect a substantial cultural problem in the field. Though there is little research on perceptions of transgender and nonbinary-related research specifically, research certainly suggests a stigmatization of gender-related work more generally (Brown et al., 2022), which could bolster impressions that transgender- and nonbinary-related research is unwelcome in high-status academic spaces. Additionally, the lack of representation of these topics itself could also contribute to these perceptions, and thus, strategies to improve representation like those mentioned above may also lead to higher submission rates. However, more research is needed to understand (a) the rates of transgender- and nonbinary-related submissions to high-status journals and the NSF, (b) to what extent low submission rates (if there is evidence of low rates) can explain the scarcity of research we found, and (c) factors influencing submission decisions for research on these topics.

Additionally, although our searches can provide a snapshot of how much research on various topics is being published or funded, they are also imperfect. For example, we could have chosen different search terms and seen slightly different results of these searches. It is therefore possible that the search terms and methodology chosen did not capture all transgender- and nonbinary-related research.

Lastly, some research identified in our searches may not have been transgender-affirming. Psychological research has harmed transgender and nonbinary communities in the (even recent) past. Because we did not code for this aspect of the research, we cannot assume that all of the articles identified by our searches were affirming of transgender and nonbinary identities.

Conclusion

Transgender and nonbinary people, whose very identities challenge the gender/sex binary, have been studied by psychologists more frequently, comprehensively, and ethically in recent years. However, we demonstrate that, while research on these populations has increased in frequency, it is still regarded as relatively low status, published infrequently by social psychology and psychology's highest status journals, and funded infrequently by the NSF. Those in power, who make decisions about which research is accepted for publication or funded, must be aware of and work to reverse this pattern. Conferring higher status upon transgender and nonbinary research through mechanisms like high status journal acceptance and NSF funding is likely to increase the impact of this research both theoretically and practically, a goal that is especially important given the pervasive challenges facing transgender and nonbinary communities today.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.

Author contributions

KM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Project administration. TM: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Methodology.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Carter Skeels and Angelina Robinson for their help coding these data. We would also like to thank the UNICORN and DIP labs for their feedback on drafts of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Some of the transgender- and nonbinary-related articles identified may also have been identified by the broader gender-related searches, with this overlap especially likely for the binary gender topics + gender search.

2. ^All of the journals included in our searches allow researchers to enter their own keywords.

3. ^Journal-level data are available at: https://osf.io/dkw5p/.

4. ^Because the “women,” “men,” “woman,” and “man” search terms were especially likely to be identified in research not meaningfully related to gender (e.g., in descriptions of sample characteristics, in research reporting a non-focal gender/sex difference, etc.), the first author and a research assistant coded articles identified by the respective searches for whether they were related to gender or not (social psychology κ= 0.79, general psychology κ= 0.63) and resolved disagreements through discussion. The numbers here reflect the number of articles determined to be related to gender only.

5. ^Within BCS, 56 projects were returned for the search for “trans.” The first author and a research assistant independently coded each of these articles for whether these projects were related to transgender or nonbinary populations or not. Both coders agreed that the term “trans” (e.g., “trans-regional,” “trans-national”) was never used in ways that are relevant to our search and these projects therefore were not included.

References

American Psychological Association (2024). Call for Papers: American Trans Psychology Amid anti-Transgender Legislation. Available at: https://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/amp/american-trans-psychology (accessed April 27, 2024).

Ansara, Y. G., and Hegarty, P. (2012). Cisgenderism in psychology: pathologising and misgendering children from 1999 to 2008. Psychol. Sex. 3, 137–160. doi: 10.1080/19419899.2011.576696

Axt, J. R., Conway, M. A., Westgate, E. C., and Buttrick, N. R. (2021). Implicit transgender attitudes independently predict beliefs about gender and transgender people. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 47, 257–274. doi: 10.1177/0146167220921065

Blader, S. L., and Chen, Y.-R. (2012). Differentiating the effects of status and power: a justice perspective. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 102, 994–1014. doi: 10.1037/a0026651

Brown, A. J., and Goh, J. X. (2016). Some evidence for a gender gap in personality and social psychology. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 7, 437–443. doi: 10.1177/1948550616644297

Brown, E. R., Smith, J. L., and Rossmann, D. (2022). “Broad” impact: Perceptions of sex/gender-related psychology journals. Front. Psychol. 13:796069. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.796069

Button, K. S., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Mokrysz, C., Nosek, B. A., Flint, J., Robinson, E. S. J., et al. (2013). Power failure: why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14, 365–376. doi: 10.1038/nrn3475

Carli, L. L., Alawa, L., Lee, Y., Zhao, B., and Kim, E. (2016). Stereotypes about gender and science: women ≠ scientists. Psychol. Women Q. 40, 244–260. doi: 10.1177/0361684315622645

Cikara, M., Rudman, L., and Fiske, S. (2012). Dearth by a thousand cuts?: Accounting for gender differences in top-ranked publication rates in social psychology. J. Soc. Issues 68, 263–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2012.01748.x

Clarivate (2024). Journal Citation Reports. Available at: https://jcr.clarivate.com/jcr/home (accessed April 27, 2024).

Connolly, M. D., Zervos, M. J., Barone, C. J., Johnson, C. C., and Joseph, C. L. M. (2016). The mental health of transgender youth: advances in understanding. J. Adolesc. Health 59, 489–495. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.012

De Luce, D., and Pettypiece, S. (2021). “Biden admin scraps Trump's restrictions on transgender troops,” in NBC News. Available at: https://www.nbcnews.com/news/military/biden-admin-scraps-trump-s-restrictions-transgender-troops-n1262646 (accessed March 28, 2024).

Finkel, E. J., Eastwick, P. W., Karney, B. R., Reis, H. T., and Sprecher, S. (2012). Online dating: a critical analysis from the perspective of psychological science. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 13, 3–66. doi: 10.1177/1529100612436522

Fiske, S. T. (2010). “Interpersonal stratification: Status, power, and subordination,” in Handbook of Social Psychology, Vol. 2, 5th ed. (Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.), 941–982.

Fiske, S. T., Dupree, C. H., Nicolas, G., and Swencionis, J. K. (2016). Status, power, and intergroup relations: the personal is the societal. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 11, 44–48. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.05.012

Friedersdorf, C. (2023). “Another side of the gender debate,” in The Atlantic. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/newsletters/archive/2023/05/another-side-of-the-gender-debate/673985/ (Accessed April 15, 2024).

Glick, P., and Fiske, S. T. (1997). Hostile and Benevolent Sexism: Measuring Ambivalent Sexist Attitudes Toward Women. Psychol. Women Q. 21, 119–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00104.x

Hammack, P. L. (2017). “Social psychology and social justice: critical principles and perspectives for the twenty-first century,” in The Oxford Handbook of Social Psychology and Social Justice, ed. P. L. Hammack (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Hanel, P. H. P., and Vione, K. C. (2016). Do student samples provide an accurate estimate of the general public? PLoS ONE 11:e0168354. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168354

Hyde, J. S., Bigler, R. S., Joel, D., Tate, C. C., and van Anders, S. M. (2019). The future of sex and gender in psychology: five challenges to the gender binary. Am. Psychol. 74, 171–193. doi: 10.1037/amp0000307

Kraus, M. W., and Torrez, B. (2020). A psychology of power that is embedded in societal structures. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 33, 86–90. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.07.018

Lee, I. C., and Crawford, M. (2012). Lesbians in empirical psychological research: a new perspective for the twenty-first century? J. Lesbian Stud. 16, 4–16. doi: 10.1080/10894160.2011.557637

Leskinen, E. A., Rabelo, V. C., and Cortina, L. M. (2015). Gender stereotyping and harassment: a catch-22 for women in the workplace. Psychol. Public Policy Law 21:192. doi: 10.1037/law0000040

Liszewski, W., Peebles, J. K., Yeung, H., and Arron, S. (2018). Persons of nonbinary gender — awareness, visibility, and health disparities. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 2391–2393. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1812005

McLemore, K. A. (2018). A minority stress perspective on transgender individuals' experiences with misgendering. Stigma Health 3, 53–64. doi: 10.1037/sah0000070

Morgenroth, T., and Ryan, M. K. (2018). Gender trouble in social psychology: how can butler's work inform experimental social psychologists' conceptualization of Gender? Front. Psychol. 9:01320. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01320

Morgenroth, T., and Ryan, M. K. (2021). The effects of gender trouble: an integrative theoretical framework of the perpetuation and disruption of the gender/sex binary. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 16, 1113–1142. doi: 10.1177/1745691620902442

Mulvihill, G. (2023). “Conflict over transgender rights simmers across the US,” in AP News. Available at: https://apnews.com/article/lgbtq-laws-states-gender-affirming-zephyr-fc2528326823c8232cb0aaa7ece0beab (accessed April 15, 2024).

Olson, K. R., Durwood, L., DeMeules, M., and McLaughlin, K. A. (2016). Mental health of transgender children who are supported in their identities. Pediatrics 137:e20153223. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3223

Olson, K. R., Key, A. C., and Eaton, N. R. (2015). Gender cognition in transgender children. Psychol. Sci. 26, 467–474. doi: 10.1177/0956797614568156

Reuben, E., Sapienza, P., and Zingales, L. (2014). How stereotypes impair women's careers in science. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 4403–4408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314788111

Riggs, D. W., Pearce, R., Pfeffer, C. A., Hines, S., White, F., and Ruspini, E. (2019). Transnormativity in the psy disciplines: constructing pathology in the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders and standards of care. Am. Psychol. 74, 912–924. doi: 10.1037/amp0000545

Rios, K., and Roth, Z. C. (2020). Is “me-search” necessarily less rigorous research? Social and personality psychologists' stereotypes of the psychology of religion. Self Identity 19, 825–840. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2019.1690035

Roberts, S. O., Bareket-Shavit, C., Dollins, F. A., Goldie, P. D., and Mortenson, E. (2020). Racial inequality in psychological research: trends of the past and recommendations for the future. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 15, 1295–1309. doi: 10.1177/1745691620927709

Ross, L., Lepper, M., and Ward, A. (2010). “History of social psychology: insights, challenges, and contributions to theory and application,” in Handbook of Social Psychology, eds. S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, and G. Lindzey (New York: Wiley).

Rudman, L. A., and Mescher, K. (2013). Penalizing men who request a family leave: is flexibility stigma a femininity stigma? J. Soc. Issues 69, 322–340. doi: 10.1111/josi.12017

Settles, I. H., Warner, L. R., Buchanan, N. T., and Jones, M. K. (2020). Understanding psychology's resistance to intersectionality theory using a framework of epistemic exclusion and invisibility. J. Soc. Issues 76, 796–813. doi: 10.1111/josi.12403

Simons, L., Schrager, S. M., Clark, L. F., Belzer, M., and Olson, J. (2013). Parental support and mental health among transgender adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 53, 791–793. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.07.019

Steinmetz, K. (2014). “The transgender tipping point,” in TIME. Available at: https://time.com/135480/transgender-tipping-point/ (accessed March 28, 2024).

Testa, R. J., Michaels, M. S., Bliss, W., Rogers, M. L., Balsam, K. F., and Joiner, T. (2017). Suicidal ideation in transgender people: Gender minority stress and interpersonal theory factors. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 126, 125–136. doi: 10.1037/abn0000234

Thalmayer, A. G., Toscanelli, C., and Arnett, J. J. (2021). The neglected 95% revisited: is American psychology becoming less American? Am. Psychol. 76, 116–129. doi: 10.1037/amp0000622

Tordoff, D. M., Wanta, J. W., Collin, A., Stepney, C., Inwards-Breland, D. J., and Ahrens, K. (2022). Mental health outcomes in transgender and nonbinary youths receiving gender-affirming care. JAMA Netw. Open 5:e220978. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0978

Tosh, J. (2016). Psychology and Gender Dysphoria: Feminist and Transgender Perspectives. London: Routledge.

Totenberg, N. (2020). “Supreme court delivers major victory To LGBTQ employees,” in NPR. Available at: https://www.npr.org/2020/06/15/863498848/supreme-court-delivers-major-victory-to-lgbtq-employees (accessed March 28, 2024).

Trans Legislation Tracker (2024). 2024 Anti-Trans Bills: Trans Legislation Tracker. Available at: https://translegislation.com (accessed April 27, 2024).

Valente, P. K., Dworkin, J. D., Dolezal, C., Singh, A. A., LeBlanc, A. J., and Bockting, W. O. (2022). Prospective relationships between stigma, mental health, and resilience in a multi-city cohort of transgender and nonbinary individuals in the United States, 2016–2019. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 57, 1445–1456. doi: 10.1007/s00127-022-02270-6

Vandello, J. A., Bosson, J. K., Cohen, D., Burnaford, R. M., and Weaver, J. R. (2008). Precarious manhood. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 95, 1325–1339. doi: 10.1037/a0012453

White Hughto, J. M., Reisner, S. L., and Pachankis, J. E. (2015). Transgender stigma and health: A critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Soc. Sci. Med. 147, 222–231. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.010

Wirtz, A. L., Poteat, T. C., Malik, M., and Glass, N. (2020). Gender-based violence against transgender people in the united states: a call for research and programming. Trauma Viol. Abuse 21, 227–241. doi: 10.1177/1524838018757749

Keywords: gender, gender binary, social psychology, transgender, nonbinary

Citation: Means KK and Morgenroth T (2024) The ubiquity of the gender/sex binary: power and status in social psychology. Front. Soc. Psychol. 2:1455364. doi: 10.3389/frsps.2024.1455364

Received: 26 June 2024; Accepted: 11 November 2024;

Published: 29 November 2024.

Edited by:

Sarah J. Gervais, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, United StatesReviewed by:

Jes L. Matsick, The Pennsylvania State University (PSU), United StatesCopyright © 2024 Means and Morgenroth. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kira Kay Means, bWVhbnM2QHB1cmR1ZS5lZHU=

Kira Kay Means

Kira Kay Means Thekla Morgenroth

Thekla Morgenroth