- 1Institute of Psychology, Faculty of Social and Political Science, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland

- 2Department of Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland

This study investigates how socialization in two different educational environments (during and after the communist regime) affects the level of social influence (manifest and latent) of a director on employees. We compared employees educated during and after the communist regime in Albania and measured the influence of a message delivered in an authoritarian vs. democratic style, by a director of a company labeled as expert vs. non-expert. Results showed that employees educated during the communist regime were more influenced at both the latent and manifest level by an authoritarian expert rather than a democratic one, whereas employees educated after the communist regime were influenced only at a latent level by a democratic expert rather than an authoritarian one. No manifest influence appeared on employees educated after the communist regime independently from the leadership style. This study highlights that the influence of leadership style is context-dependent, with early socialization shaping employees' perceptions of legitimacy and determining the levels of both manifest and latent influence.

Introduction

In an attempt to define which leadership style (approach and methodology used to lead) yields greater influence, researchers have concluded that there is no style superior to another as a general rule (Gastil, 1994), and that influence depends on several factors linked to the context within which the relationship unfolds (Ayman and Adams, 2012; Hannah et al., 2009; Stogdill, 1948). Among other so-called contextual leadership theories that explore how context or situational factors impact leadership practices (see for example Contingency Theory proposed by Fiedler, 1978; Situational Leadership Role proposed by Hersey and Blanchard, 1969), the Correspondence Hypothesis (Quiamzade et al., 2004) is one of the theoretical frameworks that seeks to explain the conditions under which one leadership style exerts more influence than another. It posits that a leadership style is influential when it corresponds with the beliefs and expectations people hold regarding what should constitute an appropriate style, meaning a style perceived as legitimate and accepted in a given context (Tyler and Lind, 1992).

This theoretical approach on the dynamics of social influence has been tested in various relationships with authority figures, notably in educational settings. Studies have investigated the leadership style of professors and its impact on the amount of social influence on students in various cultures, including former communist countries like Romania and western countries with longstanding liberal traditions like France. In Romania, studies differentiated between students at different levels of knowledge (1st year vs. 4th year students, Quiamzade et al., 2003), and students varying in their beliefs on the epistemic dependence on authority figures (high vs. low in dependence on professors, Mugny et al., 2006). The results revealed that 1st year students were more influenced by the professors with an authoritarian style compared to democratic one although the opposite trend was not observed for 4th year students. Similarly, students perceiving a higher epistemic dependence on their professors were more influenced with an authoritarian style than a democratic one, but the asymmetry was not confirmed among students low in epistemic dependence.

In contrast, in western countries like France, highly competent students were influenced more by a democratic professor compared to an authoritarian one, whereas no significant effect was found for authoritarian professors among less competent students (Quiamzade et al., 2005). An additional study conducted by Manushi Sundic et al. (under review),1 suggests that the absence of influence in certain conditions may be attributed to the overlooked role of what is construed at the ideological as being a legitimate style of leadership. This study, differently from the previous ones based on correspondence hypothesis, targeted people educated in the same national context, but in different socio-historical regimes (during vs. after communist regime) in order to investigate more thoroughly the possible effects of cultural variation using the same culture. The study showed that a leadership style is more likely to exert influence when it corresponds to people' beliefs about a legitimate style, such belief being different according to socialization with authority figures during early education in different regimes.

While these studies have confirmed the pivotal role of correspondence between leader's styles and the beliefs held by targets concerning legitimate leadership styles for the occurrence of influence, they have been short on the examination of some crucial elements essential for a more comprehensive understanding of the role of correspondence in effectiveness of leaders' styles to exert social influence. First, as we previously emphasized, most of the studies were conducted in a knowledge dependent context, such as university wherein dependence between source and target is mainly epistemic in nature, thus confirming the results of influence primarily with an expert source (a professor who possesses legitimate knowledge disparity with students). This means that generalization across contexts has been implicitly assumed but not formally tested. Second, in previous studies, the context of influence was also considered as a determinant of participants' beliefs regarding what constitutes a legitimate leadership style. This approach overlooked the impact of socialization context at an early age and its contribution to shaping a legitimate leadership style independently of the context of influence. Finally, these studies have not examined in detail the level of social influence (manifest and latent). By addressing these gaps, this study aims to develop the Correspondence hypothesis by testing crucial elements, thereby contributing to its further enhancement as one of the prominent contextual leadership theories.

The (non) expertise of leaders and the impact on the dynamics of social influence

Drawing upon the Correspondence Hypothesis, the appropriation of information provided by an epistemic authority—defined as the expertise that a source of influence possesses in a particular domain of knowledge—depends on the leadership style of the source. This assumes implicitly that expertise constitutes a core element for a source to have influence and that the amount of influence will vary with the perceived legitimacy of the leadership style.

While an expert may appear as potentially threatening by highlighting the comparison of competences between the source and the target (Major et al., 1990; Mugny et al., 2001; Zheng et al., 2022), a large body of evidence has argued that an expert can be perceived as a non—threatening source of influence when certain conditions are met (Clark et al., 2012; Petrocelli et al., 2007). One crucial condition facilitating this positive perception is related to the knowledge, experience and skills of the expert in a given domain. These attributes can be perceived as beneficial for the target's performance. Under these conditions, the target might view the expertise of the source as valuable to their own interest and acknowledge the gap between themselves and the expert in terms of expertise.

Furthermore, this dynamic becomes particularly evident when there is a disparity in status between the source and the target (Baker and Petty, 1994). When an expert source has a high status in a given context, they are not only seen as valuable for the information they possess, but also as an inspiring role model (Morgenroth et al., 2015). The target is then motivated to reach the same elevated status as the expert, thereby focusing on setting goals and motivation to attain them.

Additionally, it has been shown that message content constitutes a condition in determining the impact of experts on influencing others. People are more willing to engage with information presented by an expert, as opposed to a non-expert when it provides a counter-attitudinal content. This inclination is rooted in the expectations that experts will provide valid and robust arguments to the opposing viewpoint (Clark et al., 2012; Mackie and Goethals, 1987). Consequently, when the content of a message does not correspond to initial beliefs of the target, a non-expert source is unlikely to deliver compelling information, resulting in a lack of information acceptance.

Based on these contextual conditions, we posit that, for influence to appear, the source needs a certain level of expertise. Lack of expertise from the source would neither motivate individuals to process the information nor inspire them to follow the source as a model. Therefore, we assume that the dynamics of social influence would appear only with an expert source, and depend on the perception of leadership style as legitimate.

The role of early-age socialization in the dynamics of social influence

To determine which leadership style exerts influence, previous studies using the correspondence hypothesis, have delved into the context in which influence takes place to define people's beliefs. More specifically, participants' beliefs of style legitimacy were determined based on students' educational level (1st year vs. 4th year, Quiamzade et al., 2003), their beliefs on dependence on teachers (high vs. low dependence, Mugny et al., 2006), and proximity with the source's request (students who are already oriented to act as asked by the teacher vs. students not oriented, Tomasetto, 2004). This approach has generated a number of possible hypotheses regarding the impact of context on belief formation and the dynamics of social influence, while simultaneously overlooking the role of early-age socialization context in shaping perceptions and beliefs (Socialization Theory, Newcomb and Feldman, 1969) of what constitutes a legitimate style of leadership, independently from the context in which influence takes place.

Socialization theory posits that the most important, lasting socialization takes place during childhood years (Smith and Rogers, 2000), and that school (especially the interaction with teachers) constitutes a primary socialization context, transmitting values, attitudes, roles and other cultural products (Bukowski et al., 2015). This context helps students develop social skills (Durlak et al., 2011) and impact their beliefs and values (Grusec and Hastings, 2015; Perry, 2009).

Building upon this evidence, the present study examines the role of early socialization by clearly distinguishing between the context of socialization, which establishes accepted norms, values and perceptions, and the context of influence, which describes the factors that affet the influence of a leader. This distinction enables a more precise analysis of the underlying mechanisms explaining how a leadership style becomes influential for individuals with diverse beliefs of what constitutes a legitimate leadership style.

To test these assumptions, our study focuses on the context of Albania2 and more specifically on people educated in two distinct educational contexts (during and after the communist regime) (Alhasani, 2015; Devlin and Godfrey, 2004). This has resulted in two cohorts holding varying views on what constitutes a legitimate leadership style. People educated during communism perceive an authoritarian style and those educated after communism perceive a democratic style as more legitimate (see Manushi Sundic et al., in review).1 The notion underlying this study is that socialization under two distinct socio—historical contexts (during communism vs. after communism) will determine the level of influence that an expert leader, depending on whether their style is perceived an more or less legitimate.

Evidence suggests that a leader with a legitimate style and a certain level of expertise can foster changes in attitudes and behaviors through socio-cognitive elaboration of information, recognized as latent influence (Maass, 1987; Moscovici and Personnaz, 1980; Nemeth, 1986). Nevertheless, a social influence target might also follow an expert at the manifest level, without engaging in elaborate cognitive processing when: (a) the expert is perceived as threatening for the self-esteem of the followers (as shown in the work conducted in the framework of the Conflict Elaboration Theory developed by Pérez and Mugny, 1993), (b) followers seek trusted sources amidst cognitive dissonance (as outlined in Festinger's Cognitive Dissonance Theory, Festinger, 1954), (c) followers prefer not to engage in deep information processing (according to the Heuristic-Systematic Model by Chaiken, 1980), or (d) when they feel ill-equipped to succeed in a task (as described in the Elaboration Likelihood Model by Petty and Cacioppo, 1986). Under these conditions, a legitimate expert may engender more manifest influence. Investigating the level at which influence occurs is pivotal for understanding whether change will impact immediate behavior only or bring about a shift in beliefs and attitudes that could lead to more enduring and significant behavioral change. This differentiation can become crucial in situations involving the need for immediate responses to emerging circumstances (i.e., war, pandemic).

Generalization of the findings to other contexts

Many previous studies based on the correspondence hypothesis were performed in the school context. The present study aims to determine if the results of these studies, which are based on the relationship between teachers and students, might be generalized into different contexts. In the school context, the hierarchy between teachers and students is, by definition, conflated with knowledge discrepancy.

The workplace context is recognized as a context where, similarly to the school context, there is a hierarchy between the leader and the employee, but differently from school, hierarchy is not strictly related to discrepancy in knowledge. Consequently, despite the commonly accepted belief that leaders progress in the hierarchy based on their expertise, empirical studies have demonstrated that this is not universally applicable, and status does not always imply expertise (Carrier et al., 2014; Chng et al., 2018). Therefore, the dependence between the leader and employee in the workplace is expected to be less based on knowledge discrepancy. This dependence implies that both employees and leaders might perceive themselves high in competence leading to a threatening comparison of competences between them, that motivate them to protect self-esteem (Maass and Clark, 1983; Moscovici and Personnaz, 1980; Mugny et al., 1975-1976).

However, there is evidence suggesting that at workplace, even in situations where there is not a clear consensus regarding the leader's superior expertise compared to employees, the leaders' hierarchical position is considered as legitimate (Tyler, 2006) and their power is recognized to be proper, appropriate and just (Kanter, 1977; Ross and Reskin, 1992). Perceiving power as a structural property of social relations that derives from the powerholder's degree of control over outcomes, and not an “attribute” of an individual (Fiske and Berdahl, 2007), results in the perception of leader as less threating for the self-esteem. Hence, dependence transitions from being based on comparison of expertise to being based on the structurally derived power, thus constituting a context known as informational dependence (Quiamzade et al., 2013). The model proposed by Quiamzade et al. (2013) has inspired the present work, in that it posits that social influence depends on three key elements: the expertise of the source of influence (high vs. low), the expertise of the target of influence (high vs. low), and the perceived threat arising from the comparison of expertise levels (high vs. low threat). It provides distinct predictions for manifest and latent influence, depending on the level of each factor.

Hypotheses

We hypothesize, based on the preceding literature review, that social influence will emerge from an expert (vs. non-expert) leader (H1). Furthermore, we posit that the expert's (vs. non-expert's) influence will depend on the correspondence between their leadership style and the period in which participants were educated (H2): The expert (vs. non-expert) leader will be more influential at a manifest and latent level for participants educated during communism when using an authoritarian (vs. democratic) style (H2a). The expert (vs. non-expert) leader will be more influential at a manifest and latent level for participants educated after communism when using a democratic (vs. authoritarian) style (H2b).

Method

Sample

Participants (N = 391) were active employees of private (e.g., NGOs, call centers, private institutions) or public companies, institutions, or organizations (e.g., various ministries, state universities, state institutions) in Albania. In this study, we aimed to include participants who have received their compulsory and secondary education entirely or at least partially during the communist era and participants who received their education exclusively after communism. The threshold used for distinguishing the two cohorts was 1991, which is considered the beginning of the post-communist period in Albania (Abrahams, 2015). More specifically, cohort 1 included all participants who started their compulsory education before 1991, and cohort 2 those who started it in 1991 or after it. Taking into consideration that the age to start school in Albania was between 6 and 7 years old, and that we had only the information on the date of birth, but not the date of starting school, we eliminated the participants whom we could not categorize unambiguously in the cohorts.

The current study was conducted in May 2017, defining the age range for cohort 1 (N = 137) between 34 and up and for cohort 2 (N = 254) between 18 and 32 years old. Participants of cohort 1 had a minimum age of 34 years and a maximum of 62 (M = 41.65, SD = 6.66), and were 53 men and 84 women. Participants of cohort 2 had a minimum age of 18 and a maximum of 32 (M = 25.52, SD = 3.30), and were 83 men and 171 women. Furthermore, in cohort 1, 57 employees were from the private sector, while 80 were employed in the public sector. In cohort 2, 159 employees worked in the private sector, compared to 95 in the public sector.

The sample size was defined by the number of persons we could have access to; subsequently, a sensitivity analysis was conducted on G*Power to evaluate the detectable effect size of the sample. For a one-way ANOVA, assuming 80% power, and α of 0.05 (two-tailed), the results revealed that our final sample (N = 391) has a detectable effect size f of 0.124.

Procedure

After a set of demographic questions, participants completed an initial letter string task. The task was inspired from Nemeth and Kwan (1985, see also Quiamzade et al., 2000) and consisted of five strings of five letters. For each string, they had to write the first word they located, the letters being arranged so that in most cases they found a word derived from the usual direction of reading in Albanian (for example, the letter string QT MAMI promotes the discovery and proposition of the word MAMI). This initial task was intended to focus targets on a particular strategy, which will be referred to as “direct” strategy (reading from left to right), and to maximize the divergence from the source's strategy (see below).

In a second phase, participants were informed of the answers to each letter string task given by the director of a company akin to theirs. Incorporating a leadership example from a company similar to the participants' own in an experimental design can yield several benefits such as increased relevance that make participants consider the experiment with higher external validity, boost engagement by motivating participants to view the experiment as a reflection of potential real-life experiences (Creswell and Creswell, 2018), and increase perception of credibility of the study, resulting in more accurate responses regarding the relationship with the leader. The source's responses corresponded to a diachronically consistent strategy (Moscovici and Lage, 1976), referred to as “reverse”, involving a construction of words while using the opposite direction of reading (from right to left, e.g., IMAM for the QT MAMI string).3 They were then given additional information on this director. It was explained that “During the performance evaluation interview of his employees, of course among other instruments, this director uses anagram tasks of the type you just completed, to decide which of the employees would have a promotion”. Once the introduction was made, each participant was randomly assigned to one of four experimental conditions in a 2 (source expertise: expert vs. non-expert) x 2 (message style: democratic vs. authoritarian) design.

Expert vs. non-expert conditions

Participants were introduced to a director of a company akin to theirs. Expertise in the task was manipulated through the practice of similar tasks. For half of the participants, the source was presented as an expert: “This director is an expert in anagram tasks, as he plays letter games every day. He is member of a letters club and participates in national and international competitions”. For the other half, the source was presented as a non-expert: “This director is not at all an expert in anagram tasks, as he rarely plays letter games and has never participated in any letter club or competitions”. Despite the difference in the level of expertise, both groups of participants read as follows “…the director claims that using letters in the reverse order of their apparence in the series of letters (called the reverse strategy) brings more positive outcomes.” This procedure reproduced the one used by Quiamzade et al. (2009).

Authoritarian vs. democratic leadership style

The expert or non-expert source was introduced to the participants in either an authoritarian or democratic way. All participants had read beforehand that “During the evaluation interview of his employees, this director emphasizes the use of the reverse strategy to solve anagram tasks.” The results were presented in the authoritarian condition as follows: “... I believe that employees should undoubtedly apply this technique when doing these tasks, and only those who follow the reverse strategy will be considered for a promotion.” Instead, in a democratic condition, the director declared that “He praises employees who apply this technique when doing these tasks, but of course, even those who do not follow the reverse strategy will be considered for a promotion”.

Manipulation check

After reading the director of the company's statement, participants were asked two questions, one to evaluate the level of expertise of the director, “To which extent do you consider this director as expert or not in anagram tasks?” (1 = expert, 7 = not expert, M = 4.06, SD = 1.90), and one for his style of leadership “To which extent do you consider this director as democratic (1) or authoritarian (7)?” (M = 4.49, SD = 1.85).

Social influence measures

Then, participants were invited to a third phase which involved measuring the performance of the participants and the use of the various strategies in a complex anagram task (Quiamzade et al., 2009). The principal task used to measure social influence was to find as many words as possible in Albanian language from a 12-letter anagram introduced in a given order (PIRGMAJNATOK). Once the anagram was introduced, the following instructions were given to participants: “We now ask you to participate in another word game. Your task is to form as many words as possible in Albanian with the letters listed below. Each word can be composed with as many letters as you want, but each word must be composed of at least 3 letters. Please do not use the same letter twice in the same word. Also, proper nouns are not allowed”. Participants answered on a grid of 60 boxes numbered from 1 to 60. It should be noted that it was suggested to take only 5 min to complete this task.4

The task consisted of composing as many words as possible, and the main dependent variables were related specifically to the strategies used to compose the words. Four categories of words were distinguished: correct words constructed from reading the 12-letter anagram only from left to right, which corresponds to the usual reading direction in Albanian (“direct” strategy; M = 4.65, SD = 2.43); those produced from reading the 12-letter anagram only from right to left (“reverse” strategy; M = 3.29, SD = 2.05) corresponding strictly to the strategy attributed to the source; and those combining the two strategies, the direct and reverse ones (“mixed” strategy; M = 5.81, SD = 7.37) reading the 12-letter anagram in all directions to find meaningful words. The “direct” strategy is a measure that refers to the extent to which participants maintain consistency in their actions from the previous task. The “reverse” strategy measures manifest influence as a mere imitation of the source's way of responding, because it simply corresponds to reproducing its strategy, whereas the “mixed” strategy is a latent influence because it corresponds to a form of constructivism in which participants combine their own “direct” strategy with the source's “reverse” strategy to create a new and distinct strategy. Incorrect words that do not correspond to the instructions given on the task were also counted (words containing spelling mistakes or non-existent in Albanian, composed with less than 3 letters, or containing several times the same letter) and were categorized as incorrect words; M = 1.64, SD = 3.29.

Additional measures

Perception of the relationship between leader's expertise and status at the workplace

Perception of leader's expertise and status within the company was measured using three questions (7-point scale, 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree): “Directors have high status, but no particular expertise in their field” (M = 4.24, SD = 2.05), “Directors have high expertise, regardless of their status” (M = 4.60, SD = 1.89), and “Directors have both high status and high expertise” (M = 4.64, SD = 1.93). This measure seeks to validate the assumption that workplace leadership is not always based on expertise. It aims to assess participants' perceptions of whether leadership in their organization is driven primarily by status, expertise, or a combination of both.

Results

To test the effect of style of leadership and level of expertise per cohort, educated in two distinct socio-historical periods, on the levels of social influence (manifest and latent influence) we conducted in SPSS Statistics 29.0.1.0 a 2 (period in which participants were educated: during communism vs. after communism) x 2 (source: expert vs. non-expert) x 2 (style: democratic vs. authoritarian) between-participants analysis. We applied this analysis on the number of words found using “reverse” strategy (manifest influence), “mixed” strategy (latent influence), and “direct” strategy (consistency).

Manipulation check of leadership style

The analysis of variance on the manipulation checks of leadership style applying the aforementioned design (cohorts x leadership styles x source's expertise) showed a marginally significant difference only on the perception of leadership style of the director, F(1, 383) = 2.04, p = 0.15, = 0.005. The leader was perceived as more authoritarian in the authoritarian condition (M = 4.67, SD = 1.84) than in the democratic condition (M = 4.31, SD = 1.85). No other main effects or interactions reached significance (ps > 0.05).

Manipulation check of leader's expertise

The analysis of variance on the manipulation check on the leader's expertise applying the same experimental design (cohorts x leadership styles x source's expertise) showed no statistically significant differences either in main effects, i.e., perception of leadership expertise, F(1, 383) = 1.38, p = 0.24, = 0.004, (expert, M = 3.95, non-expert, M = 4.16), cohorts (p = 0.54), leadership style (p = 0.94), or in interactions (ps > 0.05).

Social influence dynamics

The number of words found per strategy was analyzed using the same design (cohort x leadership style x source's expertise). This analysis was performed on the “direct strategy,” the strategy proposed by the source (reverse strategy), and the new strategy combining both “direct” and “reverse” strategy (mixed strategy).

Number of correct words found by using the “reverse” strategy (manifest influence)

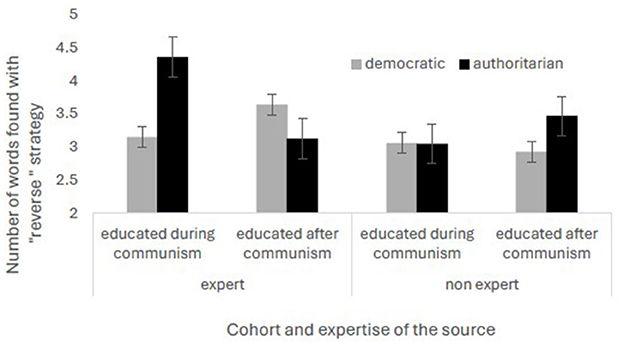

Regarding the total number of words found by using the strategy suggested by the source (“reverse” strategy), the results showed a main effect of the expertise of the source, F(1, 383) = 4.17, p = 0.042, = 0.011. The expert source made participants produce more words in the opposite direction of reading (M = 3.43, SD = 1.99) than the non-expert source (M = 3.13, SD = 2.10).

The three-way interaction was also significant, F(1, 383) = 6.74, p = 0.01, = 0.017, partially supporting H2a. Results showed a significant difference between styles of leadership, when the message was delivered by an expert, only for participants educated during communism, F(1, 383) = 5.40, p = 0.021, = 0.013. Participants educated during communism found significantly more words using the “reverse” strategy when the message was introduced by an authoritarian expert, M = 4.35 SD = 0.38 rather than a democratic expert, M = 3.15, SD = 0.35. For participants educated after communism, we observed the expected reversal of results, i.e., more words with a democratic expert (M = 3.63, SD = 0.23) rather than an authoritarian expert (M = 3.13, SD = 0.24). However, the interaction between style and expertise for this cohort did not reach statistical significance, F(1, 383) = 1.89, p = 0.16, = 0.004, therefore H2b was not confirmed.

The non-expert leader did not yield any differences in the level of imitation in participants independently from the style of leadership, in both participants educated during communism, F(1, 383) = 0.00, p = 0.99, = 0.00, and participants educated after communism, F(1, 383) = 2.25, p = 0.13, = 0.005 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Number of correct words found by using the “reverse” strategy when introduced to an authoritarian vs. democratic message by an expert vs. non-expert source. Error bars are shown in this figure.

Number of correct words found by using the “mixed” strategy (latent influence)

The analysis of the words constructed on the “mixed” strategies highlighted the main effects of cohort and source expertise, respectively F(1, 383) = 29.05, p = 0.000, = 0.071, and F(1, 383) = 8.53, p = 0.004, = 0.022. Participants educated during communism found more words using “mixed” strategy (M = 8.28, SD = 8.92) than those educated after (M = 4.42, SD = 5.98), and participants educated during communism produced more words using “mixed” strategy when the message was delivered by an expert (M = 6.43, SD = 7.44), rather than by a non-expert (M = 5.25, SD = 7.37).

The interactions between cohort and source's expertise F(1, 383) = 11.74, p = 0.001, = 0.030 and between cohort and leadership style F(1, 383) = 5.65, p = 0.018, = 0.015 were also significant. Participants educated during communism produced more words with this strategy when the message was delivered by an expert source (M = 10.74, SD = 9.41) rather than a non-expert one (M = 6.24, SD = 7.99), F(1, 383) = 15.47, p = 0.00, = 0.039 and more than participants educated after communism in front of the expert source (M = 4.26, SD = 5.01), F(1, 383) = 36.14, p < 0.001, = 0.086. There was no significant differences in participants educated after communism when confronted to an expert source (M = 4.26, SD = 5.01), or a non-expert source (M = 4.69, SD = 6.80), p = 0.66.

On the other hand, participants educated during communism found more words using “mixed” strategy when the message was delivered in an authoritarian style (M = 12.93, SD = 10.11), rather than a democratic one (M = 7, SD = 7.92), F(1, 383) = 6.31, p = 0.012, = 0.016. No difference attained the significance level for participants educated after communism (p > 0.05).

Finally, the three-way interaction was marginally significant, F(1, 383) = 3.07, p = 0.08, = 0.008. The results showed that there was a difference between styles for each cohort only when the director was introduced as an expert, and not as a non-expert. More specifically, participants educated during communism found significantly more words using the “mixed” strategy, F(1, 383) = 4.99, p = 0.026, = 0.01 when the message was delivered by an authoritarian expert, M = 12.92, SD = 1.32 rather than a democratic expert, M = 8.94, SD = 1.19, supporting H2a. Participants educated after communism found marginally more words using the “mixed” strategy, F(1, 383) = 2.95, p = 0.086, = 0.007 when the message was delivered by a democratic expert, M = 5.45, SD = 0.93 rather than an authoritarian expert M = 3.26, SD = 0.85, supporting H2b (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Number of correct words found by using the “mixed” strategy when introduced to an authoritarian vs. democratic message by an expert vs. non-expert source. Error bars are shown in this figure.

Number of correct words found using the “direct” strategy

The analysis of variance on the words found using the “direct” strategy revealed main effects of cohort and source's expertise, respectively F(1, 383) = 8.73, p = 0.003, = 0.022, and F(1, 383) = 6.22, p = 0.013, = 0.016. Participants educated during communism found more words using “direct” strategy (M = 5.00, SD = 0.35) than those educated after (M = 4.41, SD = 0.13), and participants found more words using the same strategy when the source was presented as an expert (M = 4.84, SD = 0.18), rather than a non-expert (M = 4.47, SD = 0.17).

The interaction between cohort and source's expertise F(1, 383) = 8.24, p = 0.004, = 0.021 was also significant. The difference between cohorts reached significance only with an expert source, F(1, 383) = 15.78, p = 0.002, = 0.097, and not with a non-expert, F(1, 383) = 0.004, p = 0.95, = 0.00. When the message was delivered by an expert, participants educated during communism produced more words (M = 5.86, SD = 0.30), than participants educated after communism (M = 4.37, SD = 0.21).

Finally, the three-way interaction was marginally significant F(1, 383) = 3.56, p = 0.06, = 0.009. The results showed that there was a marginal difference between styles only for participants educated after communism when the director was introduced as an expert, F(1, 383) = 2.17, p = 0.14, = 0.005. More specifically, participants educated after communism found significantly more words using “direct” strategy, when the message was delivered by a democratic expert, M = 4.69, SD = 0.31 rather than an authoritarian expert, M = 4.06, SD = 0.29.

Additional analyses

Perception of the relationship between leader's expertise and status at the workplace

Analysis of variance applying the same between participants design was conducted to assess the perception of the relationship between status and expertise in directors within companies akin of those of participants.

The results did not reveal any significant main effect or interaction regarding the perception of directors with a status lacking expertise (“Directors have high status, but no particular expertise in their field”, ps > 0.05). Concerning the perception of directors possessing expertise regardless of their status, the findings showed only a main effect of periods of education, F(1, 375) = 7.55, p = 0.006, = 0.020. Participants educated during communism perceived directors as having high expertise regardless of the status more than participants educated after communism (respectively, M = 4.64, SD = 1.98, and M = 4.02, SD = 2.06). Additionally, a marginally significant main effect of period of education was found for the perception of directors having both status and expertise, F(1, 375) = 2.86, p = 0.091, = 0.008. The combination of status and expertise convinced participants educated after communism (M = 4.77, SD = 1.93) marginally more than those educated during communism (M = 4.41, SD = 1.91).

Discussion and conclusion

The purpose of this study was to examine the levels of influence engendered by an expert (vs. non expert) leader employing a leadership style recognized as legitimate by employees educated in two distinct socio-historical contexts. Our general hypothesis posited that the presence of correspondence between the style of an expert leader and employees' beliefs about legitimate leadership style would result in both manifest and latent influence. We specifically predicted that employees educated under the communist regime would be influenced at both manifest and latent influence by an authoritarian expert (as opposed to a democratic expert), in contrast to employees educated after the communist regime, who would be subject to a democratic (rather than authoritarian) expert.

The results partially supported our hypothesis on the impact of an expert leader (as opposed to a non-expert) to engender influence at both manifest and latent levels in employees when the message was delivered in a legitimate style. Such support was observed among employees educated during communism when the message was conveyed in an authoritarian style. Contrary to our expectations, a democratic expert influenced employees educated after communism only at a latent level. It is worth noting that even if the manifest influence was not significantly greater for these participants, the difference appeared in the expected direction. Moreover, it can be expected, with small observed effect sizes, that three out of four effects were found and not all of them.

An ideological difference between the two cohorts regarding the legitimacy of a leadership style, conditioned by the socialization in two distinct socio-historical regimes, may explain the variation in the dynamics of influence between them. Employees educated during communism recognized as legitimate an authoritarian style, in which the leader has the authority to make decisions, lead, and, due to their elevated position in the hierarchy, also reward and punish those who follow them. Contrary to that, employees educated after communism recognized as legitimate a democratic style that encourages participation in decision-making and initiative-taking but does not punish or reward those who do not follow the orders of their manager. Toorn et al. (2011) found that the prominent use of power to lead, decide and reward or punish induces a sense of outcome dependence on the leader. While this dependence is in alignments with the beliefs of the cohort educated during communism, it might be perceived as a threat to the beliefs of the cohort educated after communism. This perception of threat in terms of beliefs might prevent knowledge acceptance (Falomir et al., 1998) in the cohort educated after the communism, and incite an elaboration of the information in order to validate and prove its accuracy, resulting in latent influence.

Additional analyses comparing status and expertise could provide support for a different argument. It was shown that participants educated during communism accepted that a high-status director may lack expertise, while those educated after communism believed that high status was always associated with a high level of expertise. Accepting this disparity in expertise and status made the cohort educated during communism attribute high status to factors unrelated to competence. Consequently, they may have refrained from engaging in a comparison of competences, fostering a perception of the relationship with the leader as non-threatening. The non-threatening comparison in an informational dependence context such as the workplace might explain the emergence of influence at both manifest and latent levels (see Quiamzade et al., 2013).

Conversely, participants educated after the fall of communism consistently associated status with competence. This perception may have led this cohort to interpret the status disparity with the leader in terms of expertise, perceiving the relationship with the leader as a threat to their self-esteem in terms of competences. Nevertheless, since the leader's style was deemed legitimate by this cohort (democratic), the attention shifted from comparison of competences to task elaboration to validate its content leading to more latent influence.

Contribution to the extant literature

This study makes three substantial contributions to the literature on social influence in hierarchical relationships, and most particularly to the framework of correspondence hypothesis. First, it highlights that the correspondence between a leader's style and beliefs that employees hold about legitimate style of leadership yields higher influence only when the message is delivered by an expert. However, the effect of correspondence does not apply to all sources of influence independently of their level of expertise. This study was conducted within a workplace context, diverging from the educational settings emphasized in most prior research, and thereby disentangling expertise from hierarchical status. Second, it examines the dynamics of social influence by distinguishing between the socialization context and the influential context. It leverages a recent historical change in regime in Albania to look at different expectations about leadership styles within the same country based on the system of government in which they grew up, rather than comparing between different countries. Third, it measures both manifest and latent influence, as predicted by contextual leadership theories. By making this distinction the study provides evidence for the pivotal role of early-age socialization context in shaping beliefs about legitimate style of leadership that moderate afterwards the level of both manifest and latent influence.

As previously noted, beliefs, values, norms are rooted in the early stages of school's socialization. While much of psychological research focuses on the role of parenting style and practices that foster the development of social representations across cultures (Keller, 2007; Vignoles et al., 2016), this study makes a notable contribution to the literature on the impact of education by examining the role of an educational context in shaping the dynamics of social influences (Alwin et al., 1991; Newcomb, 1943; Chatard et al., 2007). According to Steutel and Spiecker (2011), school has always been viewed as an authoritative institution, which implies that it not only disciplines students but also shapes their beliefs and attitudes (Bruner, 1996; Feldman and Newcomb, 1969; Guimond et al., 2003). Teachers, as the primary source of information on what students must learn, have legitimate authority in schools. Consequently, this study constitutes an interdisciplinary contribution to social, educational, and organizational psychology. Moreover, this study adds to the body of knowledge regarding the methodology used for investigating the dynamics of social influence concerning authoritarian figures as it stands out as one of the few that focuses on actively employed participants rather than students.

Furthermore, despite the fact that this study was conducted in Albania, an ex-communist regime, we posit that our findings can be applicable beyond the Albanian context since they contribute to a better understanding of the relationships between important theoretical constructs such as socialization, social representations, and legitimacy, and their impact on levels of social influence in the organizational context. Additionally, the study emphasizes the significance of cross-cultural studies in knowledge replication, acknowledging the varying degrees of context dependency in different aspects of human behavior (Smith et al., 2013). Last, by measuring latent and manifest influence through a direct task (the anagram), rather than relying on self-administered questionnaires, this study introduces an innovative methodology (Quiamzade et al., 2000, 2009, study 2). Once validated, this approach has the potential to become widely adopted tool for measuring influence levels, as anticipated by contextual leadership theories (Spector, 2019).

Limitations and conclusion

Limitations

We note three key limitations in this study pertaining to sample characteristics, and the methodology used. First, in order to precisely describe the cohorts, we examined their attitudes toward a specific leadership style, discovering a substantial difference among employees educated during communism (vs. after communism). For instance, people educated during communism perceived the high dependence from leader as more satisfying compared to people educated after the communism. As previously proven, people with a more positive attitude (vs. a negative attitude) are more likely to engage in subsequent behaviors that address an issue that they care about (Brugger and Hochli, 2019), assuming that the attitude influences behavior. In light of these findings, we propose that future studies address the impact of attitudes toward a leadership style in the relationship between leadership style and dynamics of social influences.

Second, our analyses revealed that while there was no significant effect observed in the manipulation check concerning the director's level of expertise, the results pertained to the dynamics of social influences indicated an impact of expertise. Additional analyses on the perception of director in terms of status and expertise suggested that there were no differences between cohorts in their perception of director possessing status without expertise. Both cohorts agreed that status necessitates expertise. This finding highlights the significance of expertise within a context of informational dependence, explaining its impact on the dynamics of social influences. Therefore, we suggest that future studies provide a scenario with more detailed definition of the source's expertise, offering clearer indicators of the level of expertise.

Third, from a methodological perspective, this study employed an anagram game to assess two distinct levels of social influence: manifest and latent. Although this approach has been employed in previous studies (i.e., Quiamzade et al., 2000, 2009, study 2) to measure the amount of influence, it has yet to be validated through a dedicated methodological validation study in order to be used for the distinction of influence levels. Consequently, future research should aim to validate this approach to establish its reliability and utility for future studies.

Conclusions

This study provides insight into the pivotal role of the educational context in defining the dynamics of social influence with a leadership style (Burak, 2018). The exploration goes beyond the impact of the context of influence alone, acknowledging the significance of the socialization context in understanding individuals' beliefs and perceptions regarding what constitutes a legitimate leadership style.

Adopting a contextual leadership approach, this study affirms that there is no universally superior leadership style that influences at both manifest and latent level at the workplace (Friesen et al., 2014; Jordan et al., 2010). The socialization context at an early age plays a crucial role in shaping the perception of leadership style legitimacy by employees thereby affecting the levels of social influence (manifest and latent) induced by a specific leadership style.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://osf.io/vzsmw/?view_only=dde738449e1c476ca140b16e396d0fc5.

Ethics statement

The requirement for ethical approval was waived by the University of Lausanne, Institute of Psychology, following the Swiss law on studies involving human participants. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

EM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. AQ: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. FB: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsps.2024.1425868/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Manushi Sundic, E., Mugny, G., Quiamzade, A., and Butera, F. (under review). Past educational context and legitimacy of leadership styles at the workplace.

2. ^Albania was selected as the research context because it provides a unique setting characterized by the influence of two distinct socio-historical regimes that significantly impacted the conditions of socialization in the realm of education.

3. ^Note that Quiamzade et al. (2000, Study 2) have shown that this strategy was viewed as more complex than a “direct” strategy, and that the source was considered especially competent in this type of task.

4. ^The results showed that the imposed time limit was not always respected by participants, based on the high number of answers they provided on the task. Being a paper-based questionnaire made it challenging to monitor the time spent in each section of the questionnaire, however it might explain the discrepancy in the number of words found among participants.

References

Abrahams, F. C. (2015). Modern Albania: From Dictatorship to Democracy in Europe. New York: NYU Press.

Alhasani, M. D. (2015). Educational turning point in albania: no more mechanic parrots but critical thinkers. J. Educ. Issues 1, 117–128. doi: 10.5296/jei.v1i2.8464

Alwin, D. F., Cohen, R. L., and Newcomb, T. M. (1991). Political Attitudes Over the Life Span: The Bennington Women After Fifty Years. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Ayman, R., and Adams, S. (2012). Contingencies, context, and gender in leadership: insights from the past and agendas for the future. Eur. J. Work Org. Psychol. 21, 743–760. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2011.649229

Baker, S. M., and Petty, R. E. (1994). Majority and minority influence: Source-position imbalance as a determinant of message scrutiny. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 67, 5–19. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.67.1.5

Brugger, A., and Hochli, B. (2019). The rôle of attitude strength in behavioural spillover: Attitude matters-but not necessarily as a moderator. Front. Psychol. 10:1018. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01018

Bruner, J. S. (1996). The Culture of Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. doi: 10.4159/9780674251083

Bukowski, W. M., Castellanos, M., Vitaro, F., and Brendgen, M. (2015). “Socialization and experiences with peers,” in Handbook of Socialization: Theory and Research, eds. J. E. Grusec and P. D. Hastings (New York: Guilford Press), 228–250.

Burak, O. (2018). Contextual leadership: a systematic review of how contextual factors shape leadership and its outcomes. Leader. Q. 29, 218–235. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.12.004

Carrier, A., Louvet, E., Chauvin, B., and Rehmer, O. (2014). The primacy of agency over competence in status perception. Social Psychol. 2014:76. doi: 10.1027/1864-9335/a000176

Chaiken, S. (1980). Heuristic versus systematic information processing and the use of source versus message cues in persuasion. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 39, 752–766. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.39.5.752

Chatard, A., Quiamzade, A., and Mugny, G. (2007). Les effets de l'éducation sur les attitudes sociopolitiques des étudiants: Le cas de deux universités en Roumanie. L'Année Psychologique 107, 225–237. doi: 10.4074/S0003503307002047

Chng, D. H. M., Kim, T.-Y., Andersson, L., and Gilbreath, B. (2018). Why people believe in their leaders - or not. MIT Sloan Managem. Rev. 60:65–80. doi: 10.7551/mitpress/12450.003.0021

Clark, J. K., Wegener, D. T., Habashi, M. M., and Evans, A. T. (2012). Source expertise and persuasion: the effects of perceived opposition or support on message scrutiny. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bullet. 38, 90–100. doi: 10.1177/0146167211420733

Creswell, J. W., and Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Los Angeles: Sage.

Devlin, P. J., and Godfrey, A. D. (2004). Still awaiting orders: reflections on the cultural influence when educating Albania. Accounting Educ. J. 13:347. doi: 10.1080/0963928042000273816

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., and Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students' social and emotional learning: a meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Dev. 82, 405–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

Falomir, J. M., Mugny, G., Sanchez-Mazas, M., Pérez, J. A., and et Carrasco, F. (1998). “Influence et conflit d'identité: de la conformité à l'intériorisation,” in Perspectives Cognitives et Conduites Sociales, eds. J. L. Dans, R. V. Beauvois, and J. M. Joule et Monteil (Neuchâtel: Delachaux et Niestlé), 313–339.

Feldman, K. A., and Newcomb, T. M. (1969). The Impact of College on Students. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Hum. Relat. 7, 117–140. doi: 10.1177/001872675400700202

Fiedler, F. E. (1978). The contingency model and the dynamics of the leadership process. J. Adv. Experim. Soc. Psychol. 11, 59–112. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60005-2

Fiske, S. T., and Berdahl, J. (2007). “Social power,” in Social Psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles, A. W. Kruglanski & E. T. Higgins (New York: The Guilford Press), 678–692.

Friesen, J. P., Kay, A. C., Eibach, R. P., and Galinsky, A. D. (2014). Seeking structure in social organization: Compensatory control and the psychological advantages of hierarchy. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 106, 590–609. doi: 10.1037/a0035620

Gastil, J. (1994). A definition and illustration of democratic leadership. Hum. Relat. 47, 953–975. doi: 10.1177/001872679404700805

Grusec, J. E., and Hastings, P. D. (2015). Handbook of Socialization: Theory and Research (2nd ed.). New York: The Guilford Press.

Guimond, S., Dambrun, M., Michinov, N., and Duarte, S. (2003). Does social dominance generate prejudice? Integrating individual and contextual determinants of intergroup cognitions. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 84: 697–721. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.697

Hannah, S. T., Uhl-Bien, M., Avolio, B. J., and Cavarretta, F. L. (2009). A framework for examining leadership in extreme contexts. Lead Q. 20, 897–919. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.09.006

Jordan, P. J., Dasborough, M. T., Daus, C. S., and Ashkanasy, N. M. (2010). A call to context. Indust. Organiz. Psychol. 3, 145–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-9434.2010.01215.x

Maass, A. (1987). Linguistic intergroup bias: stereotype perpetuation through language. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 57, 981–993. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.981

Maass, A., and Clark, R. D. (1983). Internalization versus compliance: differential processes underlying minority influence and conformity. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 13, 197–215. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2420130302

Mackie, D. M., and Goethals, G. R. (1987). “Individual and group goals,” in Group Processes, ed. C. Hendrick (Thousands Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc.), 144–166.

Major, B., Cozzarelli, C., Sciacchitano, A. M., Cooper, M. L., Testa, M., and Mueller, P. M. (1990). Perceived social support, self-efficacy, and adjustment to abortion. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 59, 452–463. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.59.3.452

Morgenroth, T., Ryan, M. K., and Peters, K. (2015). The motivational theory of role modeling: how role models influence role aspirants' goals. Rev. General Psychol. 19, 465–483. doi: 10.1037/gpr0000059

Moscovici, S., and Lage, E. (1976). Studies in social influence: III. Majority versus minority influence in a group. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 6, 149–174. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2420060202

Moscovici, S., and Personnaz, B. (1980). Studies in social influence: V. Minority influence and conversion behavior in a perceptual task. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 16, 270–282. doi: 10.1016/0022-1031(80)90070-0

Mugny, G., Butera, F., and Falomir, J. M. (2001). “Social influence and threat in social comparison between self and source's competence: relational factors affecting the transmission of knowledge,” in Social Influence in Social Reality: Promoting Individual and Social Change, eds. F. Butera and G. Mugny (Boston: Hogrefe & Huber Publishers), 225–247.

Mugny, G., Chatard, A., and Quiamzade, A. (2006). The social transmission of knowledge at the University: teaching style and epistemic dependence. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 21, 413–427. doi: 10.1007/BF03173511

Mugny, G., Doise, W., and Perret-Clermont, A.-N. (1975-1976). Sociocognitive conflict and cognitive progress. Bulletin de Psychologie, 29, 199–204. doi: 10.3406/bupsy.1976.10686

Nemeth, C. J. (1986). Differential contributions of majority and minority influence. Psychol. Rev. 93, 23–32. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.93.1.23

Nemeth, C. J., and Kwan, L. (1985). Minority influence, divergent thinking, and the detection of incorrect judgments. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 48, 399–410. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.48.2.399

Newcomb, T. (1943). “Personality and attitude change,” in Attitude Formation in Student Community. New York: Dryden.

Newcomb, T. M., and Feldman, K. A. (1969). The Impact of College on Students: An Analysis of Four Decades of Research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Pérez, J. A., and Mugny, G. (1993). Influences sociales: La théorie de l'élaboration du conflit. Delachaux et Niestlé Neuchatel.

Perry, B. D. (2009). Examining child maltreatment through a neurodevelopmental lens: Clinical applications of the neurosequential model of therapeutics. J Loss Trauma 14, 240–255. doi: 10.1080/15325020903004350

Petrocelli, J. V., Tormala, Z. L., and Rucker, D. D. (2007). Unpacking attitude certainty: attitude clarity and attitude correctness. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 92, 30–41. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.30

Petty, R. E., and Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). Communication and Persuasion: Central and Peripheral Routes to Attitude Change. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag.

Quiamzade, A., Mugny, G., and Buchs, C. (2005). Correspondance entre rapport social et auto-compétence dns la transmission de savoir par une autorité épistémique: une extension. L'Année Psychologique 105, 423–449. doi: 10.3406/psy.2005.29703

Quiamzade, A., Mugny, G., and Butera, F. (2013). Psychologie sociale de la connaissance. Fondements théoriques. Grenoble: Presses Universitaires de Grenoble, PUG.

Quiamzade, A., Mugny, G., and Darnon, C. (2009). The coordination of problem solving strategies: When low competence source exert more influence than high competence source. Br. J. Soc.Psychol. 48, 159–182. doi: 10.1348/014466608X311721

Quiamzade, A., Mugny, G., Dragulescu, A., and Buchs, C. (2003). Interaction styles and expert social influence. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 18, 389–404. doi: 10.1007/BF03173243

Quiamzade, A., Mugny, G., Falomir, J. M., Invernizzi, F., Buchs, C., and Dragulescu, A. (2004). “Correspondance entre style d'influence et significations des positions initiales de la cible: le cas des sources expertes,” in Perspectives Cognitives et Conduites Sociales, eds. J. L. Beauvois, R. V. Joule and J. M. Monteil (Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes), 341–363.

Quiamzade, A., Tomei, A., and Butera, F. (2000). Informational dependence and informational constraint: social comparison and social influences in anagram resolution. Int. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 13, 123–150.

Ross, C. E., and Reskin, B. F. (1992). Education, control at work, and job satisfaction. Soc. Sci. Res. 21, 134–148. doi: 10.1016/0049-089X(92)90012-6

Smith, A., and Rogers, V. (2000). Ethics-related responses to specific situation vignettes: Evidence of gender-based differences and occupational socialization. J. Busin. Ethics 28, 73–86. doi: 10.1023/A:1006388923834

Smith, C. E., Harris, P. L., and Paul, L. H. (2013). I should but I won't: why young children endorse norms of fair sharing but do not follow them. PLoS ONE. 8:10.1371/annotation/4b9340db-455b-4e0d-86e5-b6783747111f. doi: 10.1371/annotation/4b9340db-455b-4e0d-86e5-b6783747111f

Spector, P. E. (2019). Do not cross me: Optimizing the use of cross-sectional designs. J. Bus. Psychol. 34, 125–137. doi: 10.1007/s10869-018-09613-8

Steutel, J., and Spiecker, B. (2011). “Civic Education in A Liberal-Democratic Society1,” in Moral Education and Development, eds. D. Ruyter, and S. Miedema (Boston: SensePublishers).

Stogdill, R. M. (1948). Personal factors associated with leadership; a survey of the literature. J. Psychol. 25, 35–71. doi: 10.1080/00223980.1948.9917362

Tomasetto, C. (2004). Influence style and student's orientation toward extracurricular activities: An application of correspondence hypothesis. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 19, 133–145. doi: 10.1007/BF03173228

Toorn, J., Tyler, T. R., and Jost, J. T. (2011). More than fair: Outcome dependence, system justification, and the perceived legitimacy of authority figures. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 47, 127–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2010.09.003

Tyler, T. R. (2006). Psychological perspectives on legitimacy and legitimation. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 57, 375–400. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190038

Tyler, T. R., and Lind, E. A. (1992). “A relational model of authority in groups,” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, ed. M. P. Zanna (New York: Academic Press), 115–191.

Vignoles, V. L., Owe, E., Becker, M., Smith, P. B., Easterbrook, M. J., Brown, R., et al. (2016). Beyond the ‘east–west' dichotomy: global variation in cultural models of selfhood. J. Experim. Psychol. 145, 966–1000. doi: 10.1037/xge0000175

Keywords: education, expert power, leadership style, social influence, socialization

Citation: Manushi Sundic E, Mugny G, Quiamzade A and Butera F (2025) The (il) legitimate experts and their impact on manifest and latent social influence on employees educated in distinct socio - historical contexts. Front. Soc. Psychol. 2:1425868. doi: 10.3389/frsps.2024.1425868

Received: 08 May 2024; Accepted: 19 December 2024;

Published: 15 January 2025.

Edited by:

Marco Bilucaglia, IULM University, ItalyReviewed by:

Alessandro Fici, Università IULM, ItalyDavid Morris Perlman, Stanford University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Manushi Sundic, Mugny, Quiamzade and Butera. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fabrizio Butera, ZmFicml6aW8uYnV0ZXJhQHVuaWwuY2g=

†Deceased

Erjona Manushi Sundic

Erjona Manushi Sundic Gabriel Mugny2†

Gabriel Mugny2† Alain Quiamzade

Alain Quiamzade Fabrizio Butera

Fabrizio Butera