- 1Department of Political Science, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY, United States

- 2Department of Political Science, Carleton College, Northfield, VT, United States

In the context of longstanding racial discrimination within the legal system, high-profile incidents of police violence and misconduct have recently precipitated widespread collective action among members of marginalized communities. A large body of evidence demonstrates that social movements like Black Lives Matter, which were organized in response to legitimate concerns about racial inequality and discrimination in the legal system, have led to increased political participation, egalitarian racial attitudes, and policy reform. Still, much is unknown about the factors that shape public perceptions of Black Lives Matter; even less is known about factors influencing public opinion toward Blue Lives Matter—a movement concerned with the safety of the law enforcement community, and which may also provide ideological defense against the claims and demands of Black Lives Matter and in support of police officers believed to be unfairly maligned. Using data from two panel studies, including one sampled to approximate national representativeness, we demonstrate that positive affect toward Black Lives Matter covaries with pro-democratic attitudes and legal forms of social protest, and the belief that one's behavior can precipitate meaningful political change. We also demonstrate that anti-democratic attitudes, more satisfaction with democracy, and increased trust in government predict positive affect toward Blue Lives Matter. These results emerge while controlling for ideological self-placement and demographic variables, as well as political interest and knowledge. We discuss these findings in light of perspectives on collective action and social movement, intergroup conflict and prejudice, and ideological differences in support of democratic norms and values.

1 Introduction

When law enforcement is perceived as acting without fairness or with malice, the public lacks trust and confidence in police officers' objectivity and benevolent intentions while serving their communities (Jackson and Gau, 2016; Peffley and Hurwitz, 2010).1 For example, widely publicized instances of fatal police encounters involving racial minorities challenge perceptions of police legitimacy and contribute to what some have referred to as a “crisis” of confidence in law enforcement (Cook, 2015). These events have also given rise to increased public concern about systemic bias against racial minorities in the legal system (Parker et al., 2020)—an empirical reality long substantiated by the reported experiences of members of marginalized communities (Peffley and Hurwitz, 2010). These inequities are further evidenced by the findings of police department investigations by the U.S. Department of Justice in major municipalities (e.g., United States Department of Justice Civil Rights Division, 2016, 2017, 2016), and thoroughly documented by scientific investigations and scholarly literatures (e.g., Alexander, 2012; Glaser, 2014; Leach and Teixeira, 2022; Swencionis and Goff, 2017).

Inequities of these kind undermine citizens' willingness to accept legal authority, processes, and outcomes (Tyler et al., 2015), and can corrode citizens' satisfaction with democracy and trust in government. Scholars of social movements have long noted that a loss of legitimacy or feelings of disaffection can motivate protest designed to redress these inequities by bringing about change in public opinion, norms, and policies (Campbell, 2021; Sawyer and Gampa, 2018; Skoy, 2020; Farhart, 2017). Indeed, a prominent example of this form of collective action, Black Lives Matter (henceforth Black LM; Black Lives Matter, n.d.) represents a diverse coalition of activists seeking policy reform to redress racial bias in policing, excessive use of force among law enforcement, and other racial disparities in important life domains (Cobbina, 2019; Lowery, 2016). Since it first emerged, Black LM has inspired millions to protest in most major metropolitans and states throughout the U.S. (Williamson et al., 2018), representing one of the largest social movements in U.S. history (Buchanan et al., 2020). It is no surprise that a movement of this size and magnitude had a major influence on public opinion, political discourse, electoral outcomes, and public policy.

Research examining the impact of Black LM is burgeoning (for a review, see Ilchi and Frank, 2020; Leach and Allen, 2017). With regard to the effects of the Black LM movement on racial discourse and racial attitudes, Sawyer and Gampa (2018) and Mazumder (2019) both found that racial attitudes became more egalitarian among White Americans following the Black LM protests. One reason for these changes in racial attitudes among White Americans is that public discourse regarding anti-racism, systemic racism, and white supremacy is amplified both during and after Black LM protests (Anoll et al., 2022; Dunivin et al., 2022). Increased perceptions of discrimination against Black people increases support for governmental efforts to increase the social and economic positions of racial and ethnic minorities (Mutz, 2022).

Black LM protests also impacted local political choice and electoral outcomes by influencing political discourse and public opinion. For example, Drakulich and colleagues demonstrated that concern about bias in policing, support for civil rights protests, or positive affect toward Black LM predicted both increased preference for racially liberal political candidates (Drakulich et al., 2017) and turnout among Democrats in the 2016 U.S. presidential election (Drakulich et al., 2020). In contrast, both positive affect toward police and negative affect toward Black LM increased turnout among Republicans in the 2016 U.S. presidential election (Drakulich et al., 2020). Relatedly, Riley and Peterson (2020) found that White people, ideological conservatives, and supporters of Donald Trump hold negative attitudes toward Black LM (also see Isom et al., 2022). Mutz (2022) also found that perceptions of racial inequality increased vote switching to the Democratic candidate, Joe Biden, in the 2020 U.S. Presidential election.

The Black LM movement also affected policing behavior and practices. For example, Campbell (2021) and Skoy (2020) found that regions with Black LM protests experienced decreases in police violence. Moreover, Campbell (2021) and Peay and McNair (2022) found that Black LM protests led to increased reform in policing practices.2 For instance, Campbell (2021) found that the occurrence of Black LM protests increased the likelihood that police departments adopted the use of body-cameras and community policing models, and both increased their operating budget and reduced arrests for property crime.

Together, these findings demonstrate that Black LM protests are politically consequential; protestors organized in response to legitimate concerns about racial inequality and discrimination in the legal system, and protests motivated increased electoral participation on behalf of candidates committed to anti-Black racism, more egalitarian racial attitudes in the general public, and the adoption of policy reform. However, while the impacts of Black LM on racial attitudes, political discourse, electoral outcomes, and policing practices have garnered extensive scholarly attention, there remains a paucity of empirical research examining factors that shape public perceptions of or opinions about Black LM. Even less research has examined public opinions toward Blue Lives Matter (Blue LM)—a counterprotest movement purportedly concerned with the safety of the law enforcement community and supporting law enforcement during times of need (https://bluelivesmatternyc.org/), but which also provides ideological defense against the claims and demands of Black LM and in support of officers believed to be unfairly maligned (Chammah and Aspinall, 2020; Keyes and Keyes, 2022). To help address this gap in the literature, we join recent investigations that seek to move beyond an analysis of the political effects of Black LM protests (e.g., Riley and Peterson, 2020). Using data from two panel studies, including one sampled to approximate national representativeness, we investigate a wide range of psychological and political factors that may shape the public's perception of these consequential social movements.

Our results indicate that positive affect toward Black LM covaries with decreased antidemocratic norms and increased support for legal forms of social protest, as well as the belief that one's behavior can precipitate meaningful political change. We also find that antidemocratic attitudes, increased satisfaction with democracy, and higher levels of trust predict more positive affect toward Blue LM. These results emerge while controlling ideological self-placement, demographic variables, and political interest and knowledge. Together, these findings demonstrate that differences in beliefs about democracy, democratic norms and values, and trust predict support for different kinds of social movements.

1.1 Predictors of attitudes toward Black LM

While many Americans disapproved of the protest in its early days, Black LM gained widespread support over time (Cohn and Quealy, 2020). In the summer of 2016, for example, the Pew Research Foundation found that approximately 43% of Americans supported Black LM (Horowitz and Livingston, 2016). By the summer of 2020, the Pew Foundation reported that approximately 67% of Americans supported Black LM (Parker et al., 2020). Public support dropped slightly from this high benchmark in the summer of 2020 in September 2020 to ~55%, which remained stable through September 2021 (Horowitz, 2021). What accounts for variability in public perceptions?

Opinion polling indicates that, unsurprisingly, support for Black LM is more common among racial minorities, Democrats, liberals and women, whereas opposition to Black LM is more common among White people, Republicans, conservatives, and men (Richardson and Conway, 2022; Updegrove et al., 2020, 2018). Ilchi and Frank (2020) demonstrated the centrality of anti-Black prejudice in attitudes toward Black LM, finding that racial resentment and conservative crime ideology (i.e., “tough on crime” beliefs) are among the strongest predictors of attitudes toward Black LM. Similar observations are reported by Riley and Peterson (2020), who found that anti-Black racial resentment and prejudice are associated with negative attitudes toward Black LM. Relatedly, West et al. (2021) found that support for All Lives Matter, a counterprotest movement that emerged in opposition to Black LM, was associated with anti-Black prejudice (i.e., implicit anti-Black racism, color-blind ideologies, and narrow definition of racism).

While racial prejudice and resentment clearly predict opposition to Black LM, there remains open and important questions concerning public perceptions of and opinions about Black LM (see Richardson and Conway (2022) for an exception). For example, prior research has examined the implications of political trust and efficacy for various forms of political participation (Hetherington and Rudolph, 2015; McGarty et al., 2014), but these constructs have not been examined in relation to perceptions of Black LM protests (Leach and Allen, 2017). We address this oversight. Consistent with research on collective action (Miller et al., 2009; Osborne et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2012; Tausch et al., 2011), we anticipate that people who are dissatisfied with democracy, who lack trust in the government, or who believe that they can precipitate meaningful change (i.e., external efficacy) are hypothesized to report more positive affect toward Black LM (Hypothesis 1).

1.2 Anti-black racism and opposition to Black LM

Criticisms of and opposition to Black LM have sought to characterize its motivations, demands, and tactics as illiberal, un-American, and even violent (Clayton, 2018; Flores, 2016; Leopold and Bell, 2017; Ocasio, 2016; Solomon et al., 2019; Tillery, 2019; Weigel and Zezima, 2015). Negative beliefs about the goals of Black LM formed early (Rasmussen Reports, 2015) and have persisted, with 58-59% of likely voters endorsing the view that there is an ongoing “war on police,” and 42% reporting that “most protestors [associated with the BLM movement] are trying to incite violence or destroy property” (Rasmussen Reports, 2020). Thus, a sizable share of the public holds hostile views toward Black LM protests even though the movement explicitly advocates for nonviolence (Black Lives Matter, n.d.; Movement for Black Lives, 2016) and has overwhelmingly engaged in peaceful protest and organization (Chenoweth and Pressman, 2020).

Such criticism is particularly striking given that the demands of the Black LM movement appeal to widely shared values of equality, justice, and fairness. In this sense, Black LM joins other civil rights movements throughout history that have been viewed with suspicion and as a threat to existing social order (Clayton, 2018; Tillery, 2019; Bobo, 1988). One way to resist peaceful and legal forms of collective action designed to motivate social change and challenge existing power dynamics is to delegitimize it as extreme or radical, that is, as advancing undeserving requests or demands through nondemocratic means (Hafer and Choma, 2009; Jost, 2020; Knowles et al., 2009; Lin, 2017; Osborne et al., 2018; Solomon et al., 2019; Solomon and Martin, 2019; Teixeira et al., 2020). Indeed, members of high-status groups may reject even normatively acceptable (i.e., peaceful) forms of social protest undertaken by members of low-status groups when they perceive that such collective action damages their social image or standing (Silver et al., 2022; Teixeira et al., 2020). Consistent with this observation, Beckett (2021) found that US police were three times as likely to use force against leftwing protestors, who commonly seek social change, than rightwing protestors, who more commonly seek to maintain or restore existing social order (Jost, 2020).

It is therefore no surprise that attitudes about race and perceptions of racial inequality are central when racial or ethnic minorities engage in collective action designed to precipitate social change—that is, the kind of social movement represented by Black LM. For example, Teixeira et al. (2022) found that, among White people, a belief in systemic racial injustice translates to increased support for Black LM protests. Yet Burrows et al. (2021) found that Black activists are seen as more reactive and angrier than White activists. Thus, framing the Black LM protesters as disruptive, violent, combative, or confrontational in the media increases criticism toward protestors, reduces support for the movement, and decreases police criticism (Brown and Mourão, 2021). In this way, stereotypes about Black activists can undermine public support for Black LM and motivate a willingness to justify or ignore racial inequality (Vitriol, 2016).

In short, social movements that seek to raise awareness about an inequitable status quo and to implement progressive social change commonly invite criticism, incite ideologically motivated opposition, and energize reactionary counter-protests (Jost, 2020). Even peaceful forms of collective organization are more likely to be perceived as threatening and violent when undertaken by racial minorities (vs. White people; Peay and Camarillo, 2021). Indeed, Jones and Cox (2015) found lower levels of support for protests against unfair treatment by the government when protesters were described as “Black Americans” compared to “Americans.” For these reasons, empirical investigations of the relationship between democratic attitudes and legal forms of political participation are needed. Yet, prior research has not examined if or how attitudes toward democracy and legal forms of social protest predict perceptions of Black LM. Given the largely peaceful nature of Black LM protests and appeal to widely shared values of fairness and equality, we expect rejection of antidemocratic attitudes and respect for legal forms of protest to covary with more positive affect toward Black LM (Hypothesis 2).

1.3 Attitudes toward Blue LM: principled concern?

Opposition to collective action and social protest may also reflect genuine concerns about the implications of widespread civil unrest for public safety or principled opposition to the perceived political goals of a social movement. For example, as noted above, concerns that the Black LM protests constitute a “war on police” or contribute to violence and property damage have persisted (Rasmussen Reports, 2020; Smith et al., 2020). During the summer of 2020, 9% of Black LM protests encountered direct police intervention and 5% of the time the police used force (U.S. Crisis Monitor, 2020). Black LM demonstrations were met with counter-protestors, who were often armed and who often agitated Black LM as part of a broader strategy to undermine the movement's nonviolent focus (U.S. Crisis Monitor, 2020).

Thus, even while Black LM protests have gained public support, organizations or movements ostensibly concerned with the safety of law enforcement and their families emerged in response. Among the more prominent of these, Blue Lives Matter (henceforth Blue LM; Blue Lives Matter NYC, n.d.) originated as a coalition supporting active and retired law enforcement and is devoted to supporting families of police and advocating for more punitive action against those who commit violence against police (Chammah and Aspinall, 2020).

Over time, however, identification with and support for Blue LM may have come to represent what Solomon and Martin (2019) refer to as a countermovement (i.e., Meyer and Staggenborg, 1996), providing not just financial support and advocacy for the law enforcement community, but defense against the claims and demands of Black LM as well. Accordingly, some scholars have argued that support for Blue LM reflects symbolic solidarity in (a) opposition to the social change, demand for social justice, or policy reform represented by Black LM, and (b) in support of those believed to be unfairly targeted or misaligned by it (i.e., police; Bacon, 2016; Solomon et al., 2019; Solomon and Martin, 2019). It may itself function as a form of racial prejudice, as a way to express racial resentment, or to cast as illegitimate efforts undertaken to challenge existing power arrangements and social hierarchies. Consistent with this perspective, Riley and Peterson (2020) conceptualizes support for Blue LM within the framework of racial reaction theory, which predicts opposition, among White people, to social protest that centers on racial justice for Black people (Silver et al., 2022).

While a large body of work has examined factors that shape general perceptions of police and policing (e.g., Peffley and Hurwitz, 2010), surprisingly little research has examined affect toward the Blue LM movement. We address this oversight by testing the hypothesis that positive affect toward Blue LM will be more common among those with higher levels of satisfaction with the current state of democracy and with more trust in political actors and institutions (Hypothesis 3). After all, we anticipate that those most comfortable with existing political institutions and power arrangements will be most willing to support social movements and counter-protests that affirm or legitimize the status quo (Jost, 2020). We explore but do not advance any a priori hypotheses concerning perceptions of Blue LM and political efficacy or antidemocratic attitudes or legal activism.

2 Methods

2.1 Data and participants

We test these hypotheses using data from two panel studies, including one sampled to approximate national representativeness, recruited before and after the 2020 U.S. Presidential Election. The first sample was recruited from Amazon's Mechanical Turk platform (MTurk). MTurk samples are more diverse than student samples and more representative than typical Internet samples (Berinsky et al., 2012; Mason and Suri, 2012). The second study was quota sampled to approximate national representativeness by Forthright, an online research panel with national representative sampling capabilities, part of market research agency Bovitz, Inc. We use data from Wave 1 of both panel studies (Sample 1, October 23–30, 2020, N = 1,089, 60.4% female and 39.5% male, 56.3% with at least a BA, 54.8% with family income greater than $50,000, mean age = 44.18, SD = 14.66; White = 83.98%; Sample 2, October 27–November 2, 2020, N = 1,127, 52.80% female and 46.50% male, 32.6% with at least a BA, 50.7% with family income >$50,000, mean age = 46.34, SD = 17.04; White = 62.11%). In both samples, all measures included in the survey were presented in random order (both within and between scales), and the participants subject to this analysis completed a random subset of measures in the broader survey, including the ones relevant to our hypothesis. We rely upon data from participants who completed all measures used in the analysis described below (Sample 1 N = 474; Sample 2 N = 441). Additional demographic information about the subset of the sample included in or excluded from this analysis is reported in Appendix A.

2.2 Measures

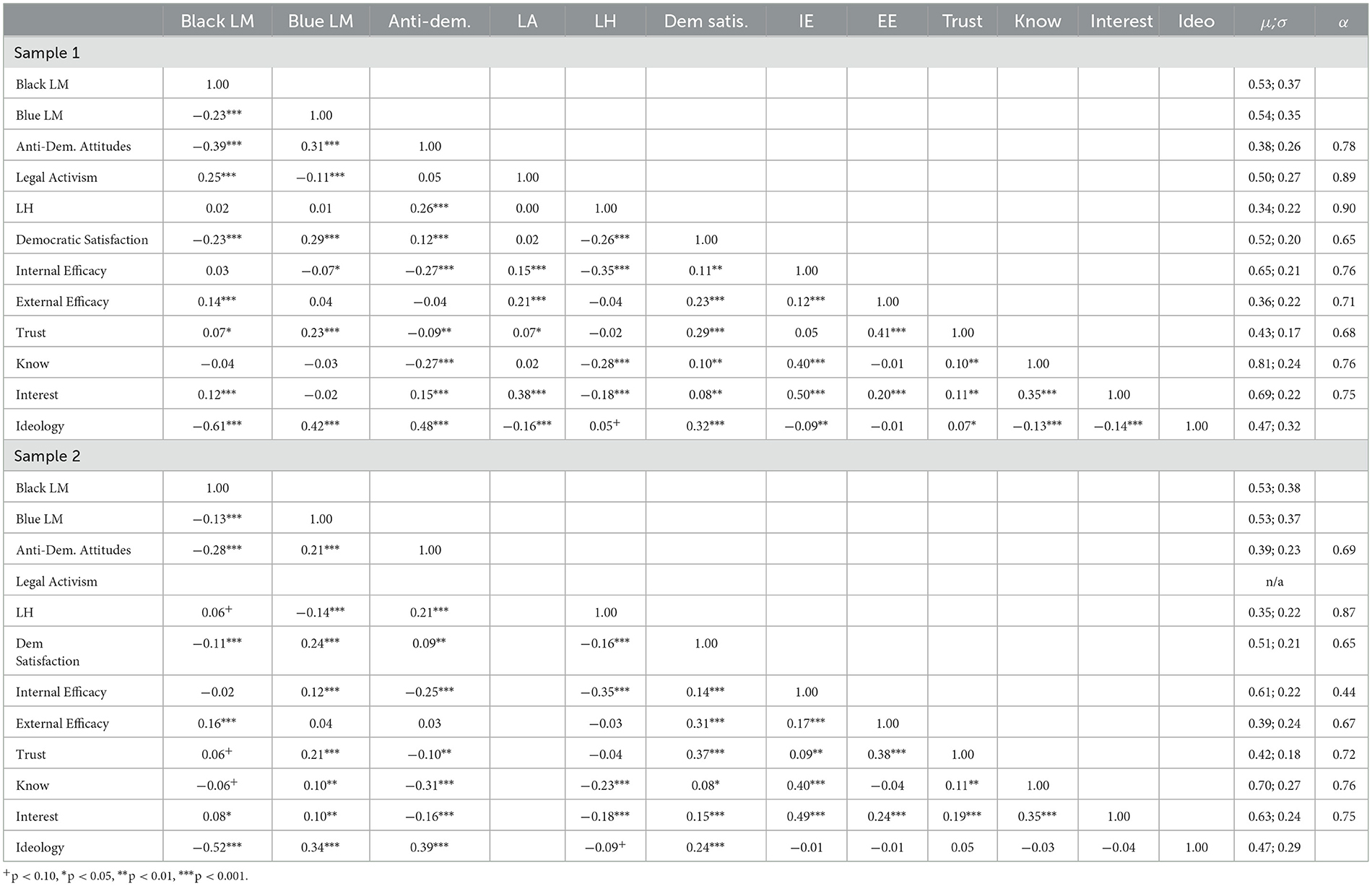

Means (SD), alphas, and intercorrelations between key variables are shown in Table 1. Question wording and response scales are available in Appendix B; additional measures that were administered in Wave 1 of the survey for both samples, but which are not central to the hypotheses examined here, are also reported in Appendix B. All measures were rescaled to range from 0 to 1.

2.2.1 Dependent variables

2.2.1.1 Black Lives Matter and Blue Lives Matter

Feeling thermometers toward Black and Blue LM were assessed as our primary dependent variables on a scale ranging from 0 (“Cold”) to 100 (“Warm”), with higher values indicating more positive affect. This approach to measuring affect toward Black or Blue LM in our study is consistent with other research examining perceptions of political groups (e.g., Bai and Federico, 2021) and Black or Blue LM (e.g., Ilchi and Frank, 2020).

2.2.2 Independent variables

We estimated the effect of support for legal activism (Sample 1 only) and democratic norms, trust, efficacy, learned helplessness, and satisfaction with democracy (Sample 1 and Sample 2).

2.2.2.1 Support for legal activism

This variable was assessed using five items, first created by Moskalenko and McCauley (2009) and revised by Petersen et al. (2023), measured on a scale ranging from 1 to 5 (1 = Strongly Agree, 2 = Agree, 3 = Neither, 4 = Disagree, 5 = Strongly Disagree). Participants are presented with a series of possible legal actions that they can carry out to promote their group's “political rights and interests.” For example, such items include “I would become a member of an organization that fights for my group's political rights and interests.” “I would travel for 1 h to join in a public rally, protest, or demonstration in support of my group.” and “I would donate money to an organization that fights for my group's political rights and interests.” Responses were coded such that higher values indicate increased support for legal activism, whereas lower values indicate less support for legal activism.

2.2.2.2 Antidemocratic attitudes

This variable was assessed using a composite of four items, measured on a 5-point scale (1 = Strongly agree, 2 = Agree, 3 = Neither/unsure, 4 = Disagree, 5 = Strongly disagree). This composite scale included three items designed to evaluate anti-democratic attitudes that were created by Bartels (2020) and an additional item administered by the Latin American Public Opinion Project (n.d.). For example, such items include “Strong leaders sometimes have to bend the rules in order to get things done.”, “When the country is facing difficult times, it is justified for the president of the country to close Congress and govern without Congress.”, “A time will come when patriotic Americans have to take the law into their own hands.”, and “It is hard to trust the results of elections when so many people will vote for anyone who offers a handout.”. Responses were coded such that higher values indicate increased levels of anti-democratic attitudes, whereas lower values indicate lower levels of anti-democratic attitudes.

2.2.2.3 Political disaffection

Prior work has demonstrated that those who are politically disaffected are distrusting of the political system, less interested, exposed to, and informed about politics, less likely to attend political rallies or engage in volunteer work on behalf of a party or candidate, less likely to believe they can change the political system or that political elites care about them, and are less likely to be satisfied with democracy and political institutions (Farhart, 2017; Torcal and Montero, 2006). Thus, we utilize five measures of political disaffection: generalized trust, internal and external efficacy, learned helplessness, and democratic satisfaction.

2.2.2.4 Trust

Trust was measured using a generalized index of trust in federal and local government, media, people in general, and law enforcement, measured on a 4-point scale (1 = almost always, 2 = most of the time, 3 = some of the time, 4 = almost never). Participants responded to the stem, “How much of the time do you think you can trust the following to do what is right?” for each referent. Responses were coded such that higher values indicate higher levels of trust.

2.2.2.5 Internal and external efficacy

These constructs were each assessed using short two-item batteries from Craig et al. (1990), measured on a 5-point scale (1= Always, 2 = Most of the time, 3 = About half of the time, 4 = Some of the time, 5 = Never). For internal efficacy, participants were asked, “How often do politics and government seem so complicated that you can't really understand what's going on?” For external efficacy, participants were asked, “How much can people like you affect what the government does?” Responses were coded such that higher values indicate higher levels of internal and external efficacy.

2.2.2.6 Learned helplessness

While similar to some measures of trust and efficacy, we also assessed Learned Helplessness, which provides a unique approach to assess perceptions of one's repeated attempts and failures, inside and outside of the political domain (Peterson et al., 1993), measured here using a short six-item battery (Farhart, 2017) taken from the original 20-items (Quinless and McDermott Nelson, 1988). These items were measured on a 4-point scale (1 = Strongly agree, 2 = Agree, 3 = Disagree, 4 = Strongly disagree). For example, such items include. “No matter how much energy I put into a task, I feel I have no control over the outcome,” “Other people have more control over their success and/or failure than I do,” and “No matter how hard I try, things never seem to work out the way I want them to.” Responses were coded such that higher values indicate higher levels of learned helplessness.

2.2.2.7 Democratic satisfaction

We also measured satisfaction with democracy, the economy, and life in general (Di Palma, 1969) using a three-item index, including: (1) “On the whole, how satisfied are you with the way democracy works in the United States?” (2) “All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole these days?” and (3) “Over the last 5 years, when you compare your economic situation to how others in our society are doing, do you think you are doing better than average, about the same, or worse than average?” Responses to the first two items were assessed on a 4-point scale (1 = Very satisfied, 2 = Fairly satisfied, 3 = Not very satisfied, 4 = Not at all satisfied). Responses to the third item were assessed on a 5-point scale (1 = Much better than average, 2 = Somewhat better than average, 3 = About the same, 4 = Somewhat worse than average, 5 = Much worse than average). Responses to these items were averaged and coded such that higher values correspond to higher levels of satisfaction with democracy.

2.3 Control variables

Several control variables were included as covariates. First, demographics included: age, income (ordered categories rescaled from 0 to 1), gender (0 = male, 1 = female), education (ordered categories rescaled from 0 to 1), and race (0 = nonwhite, 1 = White). Second, because affect toward social or political groups may covary with levels of political engagement (e.g., Federico and Sidanius, 2002), we controlled for knowledge about and interest in politics using two variables: (1) Political knowledge was assessed using eight factual political knowledge items (e.g., Delli Carpini and Keeter, 1996). Items were scored on a 0 (incorrect) or 1 (correct) basis, summed, and averaged; (2) Political interest was assessed using three items that evaluated interest in politics and the importance of politics (Vitriol et al., 2019). Third, we controlled for ideological self-placement because political predispositions covary with perceptions of political groups (e.g., Bai and Federico, 2021; Updegrove et al., 2020). Higher scores correspond with greater knowledge, interest, and conservatism.

3 Results

Table 1 reports the means (SD), alphas, and intercorrelations of all measures.3 The direction of the correlation between Black and Blue LM (rs = −0.13 to −0.23, p < 0.001) indicates that as positive affect for one increases, negative affect for the other decreases. This observation aligns with characterizations of Blue LM as a counter-movement to Black LM, although the small relationship indicates other factors relate to perceptions of both. For this reason, we turn to formal tests of our hypotheses.

In particular, we examine three hypotheses. First, we anticipate that people who are dissatisfied with democracy, lack trust in the government, or believe they can precipitate meaningful change (i.e., external efficacy) will report more positive affect toward Black LM (Hypothesis 1). We also expect rejection of anti-democratic attitudes and respect for legal forms of protest to covary with more positive affect toward Black LM (Hypothesis 2). Finally, we test the hypothesis that positive affect toward Blue LM will be more common among those with higher levels of satisfaction with the current state of democracy and with more trust in political actors and institutions (Hypothesis 3).

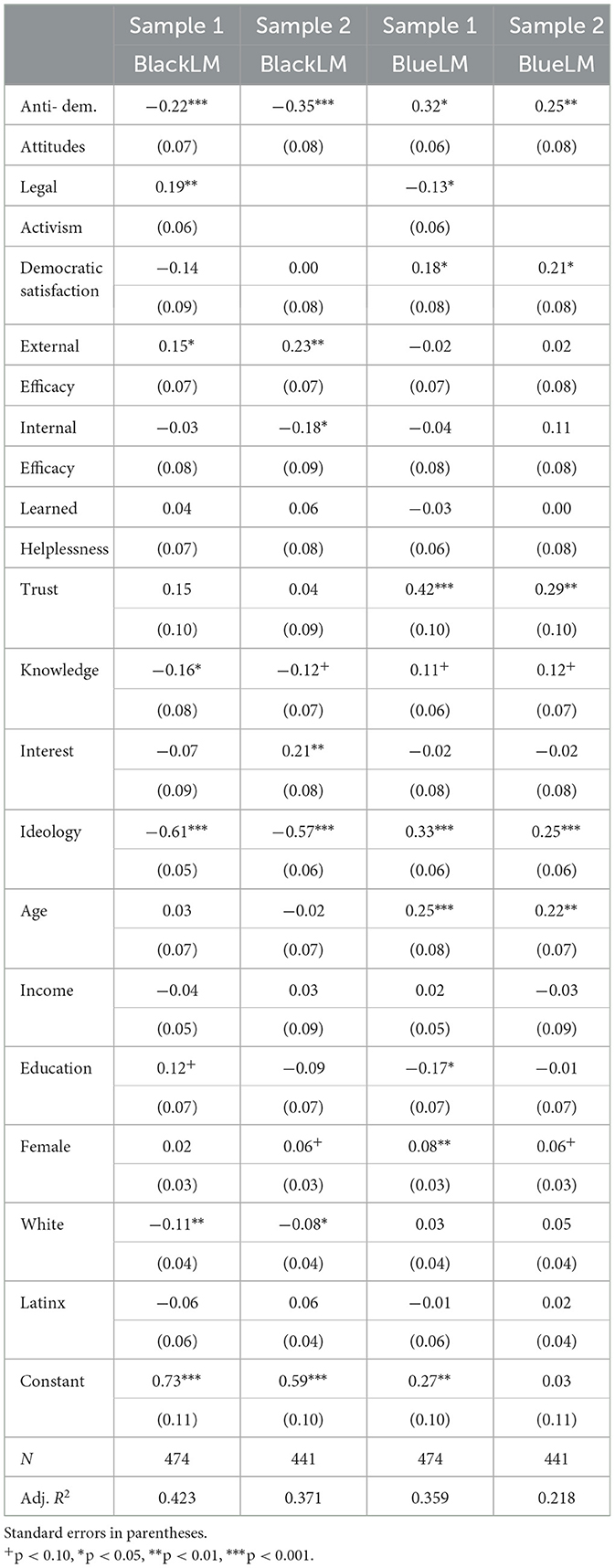

We estimated a series of OLS regression models. In each sample, we regressed each dependent variable on all independent variables and covariates. To guard against heteroscedasticity, standard errors and confidence intervals were computed using HC3 variance estimates (Long and Ervin, 2000). Given the 0-1 coding of all variables, the coefficients represent the proportion change (or percentage change when multiplied by 100) in the dependent variable associated with going from the lowest to the highest level of each predictor. The results for Samples 1 and 2 largely confirm Hypotheses 2 and 3 and partially confirm Hypothesis 1 (summarized in Table 2).

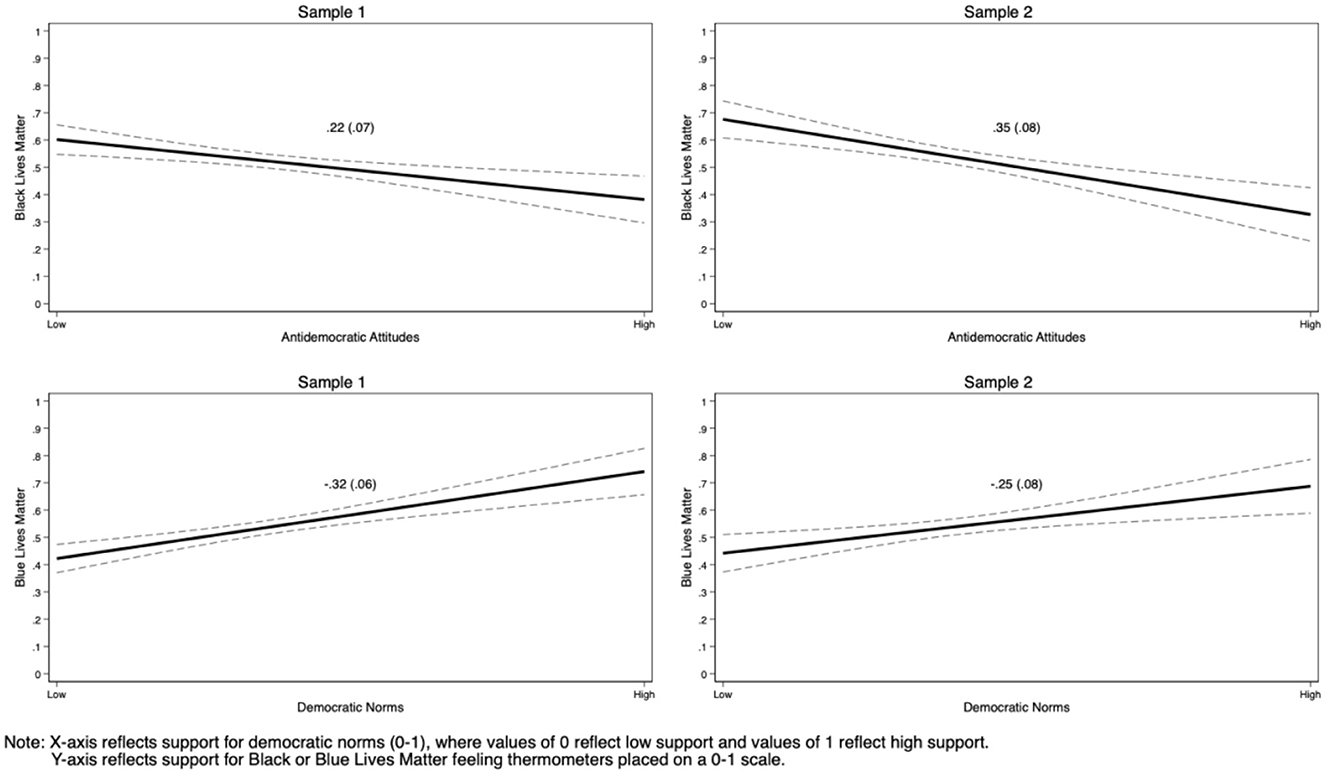

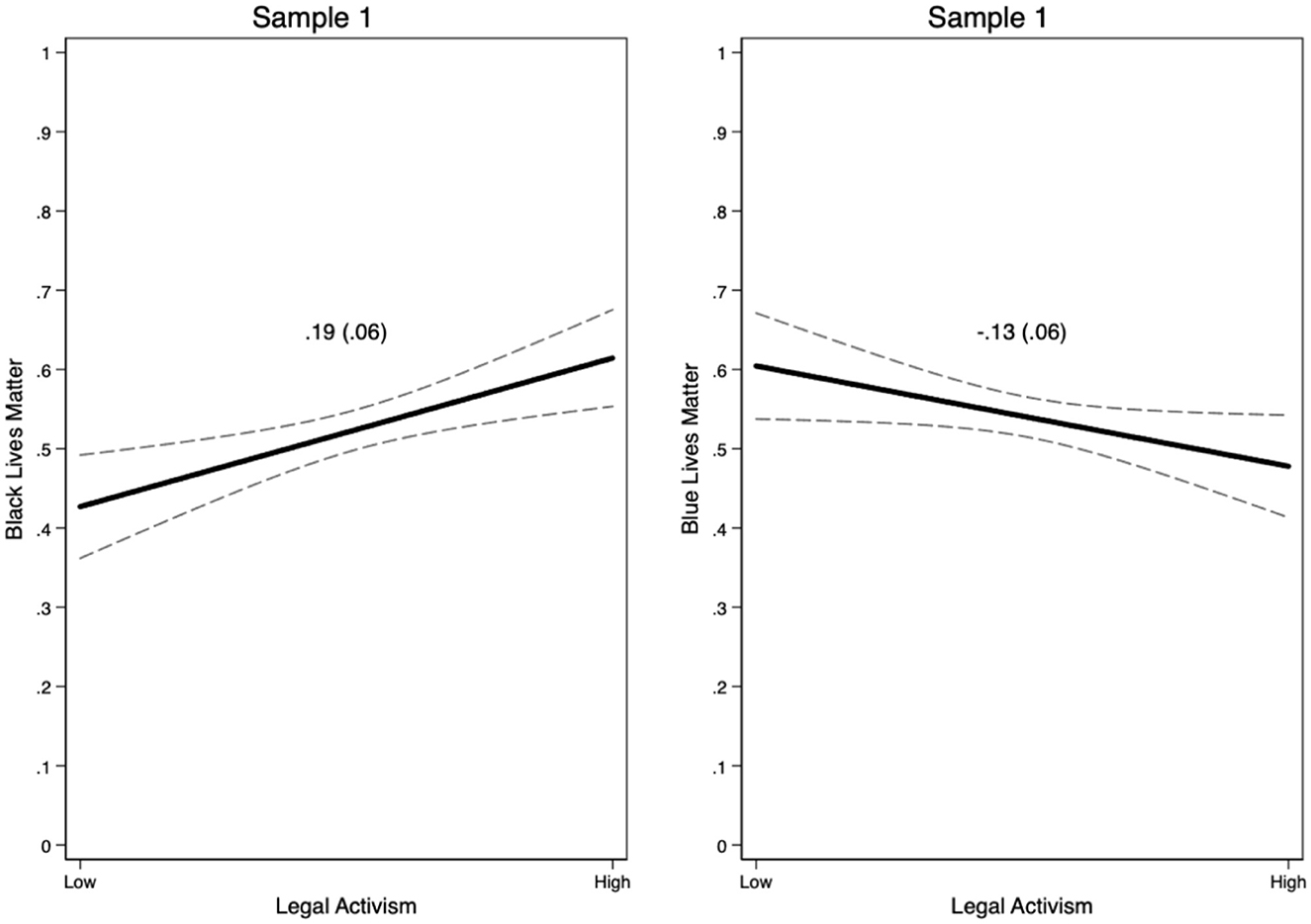

Positive affect toward Black LM was predicted by lower levels of anti-democratic attitudes (Sample 1, b = −0.22, p < 0.001; Sample 2, b = −0.35, p < 0.001) and higher levels of support for legal activism (Sample 1, b = 0.19, p < 0.01). Similarly, positive affect toward Blue LM was predicted by higher levels of anti-democratic attitudes (Sample 1, b = 0.32, p < 0.05; Sample 2, b = 0.25, p < 0.01) and legal activism (Sample 1, b = −0.13, p < 0.05). Going from the lowest to the highest level of anti-democratic attitudes was associated with a 22–35% decrease in positive affect toward Black LM or a 25–32% increase in positive affect toward Blue LM (Figure 1). Going from the lowest to the highest level of support for legal activism was associated with a 19% increase in positive affect toward Black LM or a 13% decrease in positive affect toward Blue LM (Figure 2). These were considerable changes compared to those associated with other predictors in the model (25–65% for ideological self-placement; see Table 2 and Appendix C).

Figure 1. Relationship between anti-democratic attitudes and affect toward black lives matter and blue lives matter.

Figure 2. Relationship between legal activism and affect toward black lives matter and blue lives matter. X-axis reflects level of agreement with legal activism engagement (0–1), where values of 0 reflect strong disagreement and values of 1 reflect strong agreement. Y-axis reflects support for Black or Blue Lives Matter feeling thermometers placed on a 0–1 scale.

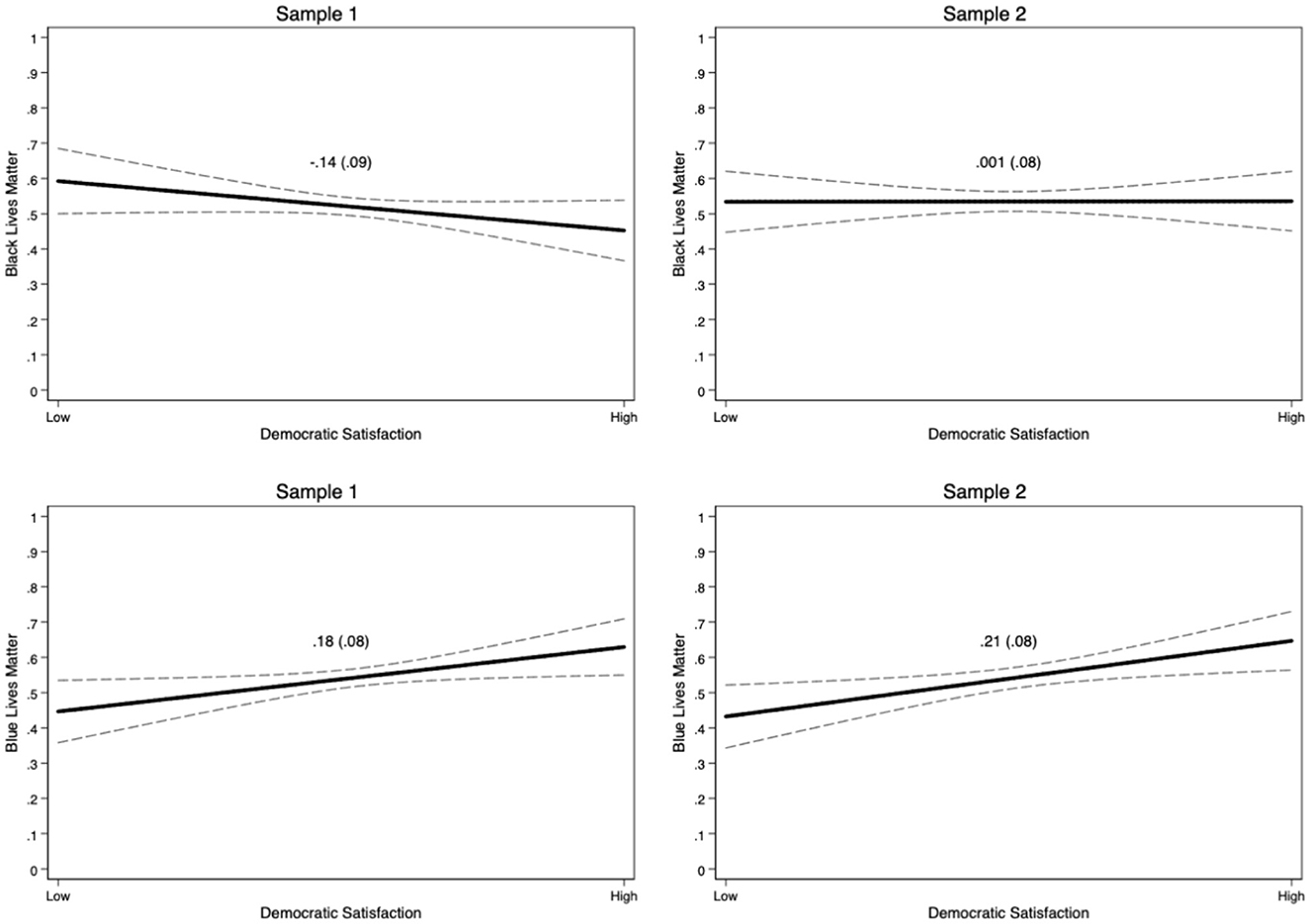

Regarding feelings of disaffection, higher external efficacy covaried with positive affect toward Black LM (Sample 1, b = 0.16, p < 0.05; Sample 2, b = 0.23, p < 0.01), but is not related to affect toward Blue LM (see Figure 3). Internal efficacy was an inconsistent predictor, only acquiring significance in Sample 2 for Black LM (b = −0.18, p < 0.05). Trust predicted positive affect toward Blue LM (Sample 1, b = 0.42, p < 0.001; Sample 2, b = 0.29, p < 0.01), but was not related to affect toward Black LM. High democratic satisfaction predicted positive affect toward Blue LM (Sample 1, b = 0.18, p < 0.05; Sample 2, b = 0.21, p < 0.05), but was unrelated to Black LM (see Figure 4). Finally, learned helplessness did not significantly predict affect toward Black or Blue LM.

Figure 3. Relationship between external and affect toward black lives matter and blue lives matter. X-axis reflects level of external efficacy (0–1), where values of 0 reflect low external efficacy and values of 1 reflect high external efficacy. Y-axis reflects support for Black or Blue Lives Matter feeling thermometers placed on a 0–1 scale.

Figure 4. Relationship between democratic satisfaction and affect toward black lives matter and blue lives matter. X-axis reflects level of democratic satisfaction (0–1), where values of 0 reflect low satisfaction and values of 1 reflect high satisfaction. Y-axis reflects support for Black or Blue Lives Matter feeling thermometers placed on a 0–1 scale.

4 Discussion

The maltreatment of racial minorities during police encounters is certainly not unique to modern times (Edwards et al., 2018). Nonetheless, in the context of longstanding persecution and discrimination within the legal system, high-profile incidents of police violence and misconduct have recently precipitated widespread collective action among members of marginalized communities (Cobbina, 2019; Peay and Camarillo, 2021; Williamson et al., 2018). A large body of evidence demonstrates that Black LM organized in response to legitimate concerns about racial inequality and discrimination in the legal system (Cobbina, 2019; Lowery, 2016; Peffley and Hurwitz, 2010), and has precipitated meaningful change in public opinion, political discourse, electoral outcomes, and public policy (for a review, see Ilchi and Frank, 2020; Leach and Allen, 2017). For example, Black LM protests increased public awareness and discussion of racial inequality (Anoll et al., 2022; Dunivin et al., 2022), led to more egalitarian racial attitudes (Anoll et al., 2022; Dunivin et al., 2022; Mazumder, 2019; Sawyer and Gampa, 2018), increased support for more racially liberal political candidates (Drakulich et al., 2017), and motivated the adoption of criminal justice reform and change in policing practices (Boudreau et al., 2022; Campbell, 2021; Peay and McNair, 2022; Skoy, 2020).

While work has examined factors that motivated participation in Black LM and the impact of Black LM protests specifically on public attitudes, discourse, and policy, little is known about the factors that shape the public's perceptions of Black LM; even less research has examined factors that shape public perceptions of Blue LM, a counter-movement concerned with the safety of the law enforcement community, but which often provides ideological defense against the claims and demands of Black LM (Chammah and Aspinall, 2020; Keyes and Keyes, 2022). This is no small matter. Racial inequality perpetuates harm against marginalized communities and has long threatened the integrity of American democracy, as does ideological backlash against peaceful and lawful forms of social protest designed to remediate police misconduct and discrimination in the legal system. Movements like Black LM aim to address these issues through peaceful and lawful forms of social protest and have been impactful in achieving much of its goals. However, counter-movements like Blue LM can function to maintain existing inequitable power dynamics, often by obfuscating, undermining, or otherwise opposing the claims, goals, and demands of movements like Black LM. Understanding public perceptions of social movements designed to address racial inequality and counter-movements that function to maintain a status quo of inequitable power arrangements represents, in our view, a scientific imperative for social and political psychologists.

What shapes perceptions of Black and Blue LM? Research pursuing this question has largely been limited to investigations of intergroup attitudes and racial resentment in underpinning opposition to Black LM (e.g., Ilchi and Frank, 2020; Riley and Peterson, 2020; Silver et al., 2022; West et al., 2021). The current study sought to extend this work by addressing open and important questions concerning public perceptions of Black and Blue LM. Using data from two panel studies, including one sampled to approximate national representativeness, we investigated the extent to which the same set of psychological and political factors predicted perceptions of this consequential social movement and counterprotest. By juxtaposing perceptions of Black and Blue LM in our analysis, we aimed to identify critical similarities and differences in public perceptions of political organization that challenges or affirms the racial status quo, and to understand ideological divisions more fully in the contemporary sociopolitical landscape. Our results provide consistent evidence across two samples that positive affect toward Black LM covaries with decreased antidemocratic attitudes and increased legal forms of social protest, and the belief that one's behavior can precipitate meaningful political change. In contrast, increased antidemocratic attitudes, and increased satisfaction with democracy and trust predicted positive affect toward Blue LM. These results were robust to controls for ideological self-placement, demographic variables, and political knowledge and engagement.

Together, these findings are consistent with existing research on motivations for collective action, which emphasize how legal and political inequity can undermine institutional legitimacy and trust, leading to feelings of disaffection that can trigger participation in protest designed to bring about change in public opinion, norms, and policies (Campbell, 2021; Sawyer and Gampa, 2018; Skoy, 2020; Farhart, 2017). Critically, our results also indicate that support for Black LM is underpinned by broader support for peaceful and lawful forms of political participation—actions that are central to functioning democracies and necessary to redress systemic inequity and inequality in the legal system and elsewhere. Yet history teaches us that even nonviolent protests, such as Black LM, that seek remediation for maltreatment, discrimination, and disadvantage may not always garner widespread public support. Instead, such movements might invite opposition from those who are content with existing power dynamics and may weaken their commitment to democratic norms and values if doing so helps protect their social standing.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary material.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Stony Brook University and Lehigh University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JV: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CF: Data curation, Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Leonie Huddy for her role in helping to develop our thinking and for providing critical feedback on earlier versions of this manuscript. The authors would also like to thank the Research Foundation for The State University of New York, the Stony Brook Foundation, Inc., and the College of Arts and Sciences at Stony Brook University for providing the resources needed to recruit the two samples used in this research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsps.2024.1417995/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Even members of historically marginalized groups that have been subject to maltreatment by law enforcement support “good” policing and desire fair, legitimate forms of law enforcement (Peffley and Hurwitz, 2010).

2. ^While Vaughn et al. (2022) find support for police reform following Black LM protests; they do not observe change in support for abolishing or defunding the police.

3. ^Replication data and syntax are available at: https://osf.io/72vhd/?view_only=1ceec9433ad94e19b6edfd362cb2881f.

References

Alexander, M. (2012). The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York, NY: The New Press.

Anoll, A. P., Engelhardt, A. M., and Israel-Trummel, M. (2022). Black lives, white kids: white parenting practices following black-led protests. Persp. Polit. 20, 1328–1345. doi: 10.1017/S1537592722001050

Bacon, P. (2016). Trump and Other Conservatives Embrace ‘Blue Lives Matter' Movement. New York City: NBC News. Available at: https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/2016-election/trump-other-conservatives-embrace-blue-lives-matter-movement-n615156

Bai, H., and Federico, C. M. (2021). White and minority demographic shifts as an antecedent of intergroup threat and right-wing extremism. J. Exp. Social Psychol. 94:104114. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2021.104114

Bartels, L. M. (2020). Ethnic antagonism erodes Republicans' commitment to democracy. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 117, 22752–22759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2007747117

Beckett, L. (2021). US police Three Times as Likely to use Force Against Leftwing Protesters, Data Finds. New York: The Guardian.

Berinsky, A. J., Huber, G. A., and Lenz, G. S. (2012). Evaluating online labor markets for experimental research: Amazon.com's Mechanical Turk. Polit. Analy. 20, 351–368. doi: 10.1093/pan/mpr057

Black Lives Matter (n.d.). Black Lives Matter. Available at: https://blacklivesmatter.com

Blue Lives Matter NYC (n.d.). Blue Lives Matter NYC. Available at: https://bluelivesmatternyc.org/

Bobo, L. (1988). Attitudes toward the Black political movement: trends, meaning, and effects on racial policy preferences. Soc. Psychol. Quart. 51, 287–302. doi: 10.2307/2786757

Boudreau, C., MacKenzie, S. A., and Simmons, D. J. (2022). Police violence and public opinion after George Floyd: how the Black Lives Matter movement and endorsements affect support for reforms. Polit. Res. Quart. 75, 497–511. doi: 10.1177/10659129221081007

Brown, D. K., and Mourão, R. R. (2021). Protest coverage matters: How media framing and visual communication affects support for Black civil rights protests. Mass Commun. Soc. 24, 576–596. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2021.1884724

Buchanan, L., Bui, Q., and Patel, J. K. (2020). Black Lives Matter may be the Largest Movement in U.S. History. New York: The New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/07/03/us/george-floyd-protests-crowd-size.html

Burrows, B., Selvanathan, H. P., and Lickel, B. (2021). My fight or yours: stereotypes of activists from advantaged and disadvantaged groups. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 49, 110–124. doi: 10.1177/01461672211060124

Campbell, T. (2021). Black Lives Matter's effect on police lethal use-of-force. SSRN Elect. J. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3767097

Chammah, M., and Aspinall, C. (2020). The Short, Fraught History of the ‘Thin Blue Line' American Flag. Arlington, VA: Politico. Available at: https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2020/06/09/the-short-fraught-history-of-the-thin-blue-line-american-flag-309767

Chenoweth, E., and Pressman, J. (2020). This Summer's Black Lives Matter Protestors were Overwhelmingly Peaceful, our Research Finds. Washington: The Washington Post. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/10/16/this-summers-black-lives-matter-protesters-were-overwhelming-peaceful-our-research-finds/

Clayton, D. M. (2018). Black Lives Matter and the civil rights movement: a comparative analysis of two social movements in the U.S. J. Black Stud. 49, 448–480. doi: 10.1177/0021934718764099

Cobbina, J. E. (2019). Hands Up, Don't Shoot: Why the Protests in Ferguson and Baltimore Matter, and How They Changed America. New York: New York University Press.

Cohn, N., and Quealy, K. (2020). How Public Opinion Has Moved Black Lives Matter. New York: The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/06/10/upshot/black-lives-matter-attitudes.html

Cook, P. J. (2015). Will the current crisis in police legitimacy increase crime? Research offers a way forward. Psychol. Sci. Public Inter. 16, 71–74. doi: 10.1177/1529100615610575

Craig, S. C., Niemi, R. G., and Silver, G. E. (1990). Political efficacy and trust: a report on the NES pilot study items. Polit. Behav. 12, 289–314. doi: 10.1007/BF00992337

Delli Carpini, M. X., and Keeter, S. (1996). What Americans Know About Politics and Why it Matters. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Di Palma, G. (1969). Disaffection and participation in Western democracies: the role of political oppositions. J. Polit. 31, 984–1010. doi: 10.2307/2128355

Drakulich, K. M., Hagan, J., Johnson, D., and Wozniak, K. H. (2017). Race, justice, policing, and the 2016 American presidential election. Du Bois Review 14, 7–33. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X1600031X

Drakulich, K. M., Wozniak, K., Hagan, J., and Johnson, D. (2020). Race and policing in the 2016 presidential election: Black lives matter, the police, and dog whistle politics. Criminology 58, 370–402. doi: 10.1111/1745-9125.12239

Dunivin, Z. O., Yan, H. Y., Ince, J., and Rojas, F. (2022). Black Lives Matter protests shift public discourse. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 119:e2117320119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2117320119

Edwards, F. R., Esposito, M., and Lee, H. (2018). Risk of police-involved death 1 by race/ethnicity and place, United States, 2012-2018. Am. J. Public Health 108, 1241–1248. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304559

Farhart, C. E. (2017). Look Who is Disaffected Now: Political Causes and Consequences of Learned Helplessness in the U.S. (Doctoral dissertation) Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota.

Federico, C. M., and Sidanius, J. (2002). Racism, ideology, and affirmative action revisited: the antecedents and consequences of ‘principled objections' to affirmative action. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 82, 488–502. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.82.4.488

Flores, R. (2016). Donald Trump: Black Lives Matter calls for Killing Police. New York, NY: CBS News. Available at: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/donald-trump-black-lives-matter-calls-for-killing-polic

Glaser, J. (2014). Suspect Race: Causes and Consequences of Racial Profiling. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hafer, C. L., and Choma, B. L. (2009). “Belief in a just world, perceived fairness, and justification of the status quo,” in Series in Political Psychology: Social and Psychological Bases of Ideology and System Justification, eds. J. T. Jost, A. C. Kay, & H. Thorisdottir (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 107–125.

Hetherington, M. J., and Rudolph, T. J. (2015). Why Washington Won't Work: Polarization, Political Trust, and the Governing Crisis. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Horowitz, J. M. (2021). Support for Black Lives Matter Declined after George Floyd Protests, but has Remained Unchanged Since. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2021/09/27/support-for-black-lives-matter-declined-after-george-floyd-protests-but-has-remained-unchanged-since/

Horowitz, J. M., and Livingston, G. (2016). How Americans view the Black Lives Matter Movement. Washington, DC: Pews Research Center. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/07/08/how-americans-view-the-black-lives-matter-movement/

Ilchi, O. S., and Frank, J. (2020). Supporting the message, not the messenger: the correlates of attitudes towards Black Lives Matter. Am. J. Crimi. Just. 46, 377–398. doi: 10.1007/s12103-020-09561-1

Isom, D. A., Boehme, H. M., Cann, D., and Wilson, A. (2022). The white right: a gendered look at the links between ?victim? ideology and anti-black lives matter sentiments in the era of trump. Crit. Sociol. 48, 475–500. doi: 10.1177/08969205211020396

Jackson, J., and Gau, J. M. (2016). “Carving up concepts? Differentiating between trust and legitimacy in public attitudes towards legal authority,” in Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Trust: Towards Theoretical and Methodological Integration, eds. E. Shockley, T. M. S. Neal, L. M. Pytlik-Zillig, & B. H. Bornstein (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 49–69.

Jones, R. P., and Cox, D. (2015). Deep Divide Between Black and White Americans in Views of Criminal Justice System. Washington, DC: PRRI. Available at: http://www.prri.org/research/divide-white-black-americans-criminal-justice-system/

Keyes, V. D., and Keyes, L. (2022). Dynamics of an American countermovement: Blue Lives Matter. Sociol. Compass 16:e13024. doi: 10.1111/soc4.13024

Knowles, E. D., Lowery, B. S., Hogan, C. M., and Chow, R. M. (2009). On the malleability of ideology: Motivated construals of color blindness. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 96, 857–869. doi: 10.1037/a0013595

Leach, C. W., and Allen, A. M. (2017). The social psychology of the Black Lives Matter meme and movement. Curr. Direct. Psychol. Sci. 26, 543–547. doi: 10.1177/0963721417719319

Leach, C. W., and Teixeira, C. P. (2022). Understanding sentiment toward “Black Lives Matter.” Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 16, 3–32. doi: 10.1111/sipr.12084

Leopold, J., and Bell, M. P. (2017). News media and the racialization of protest: an analysis of Black Lives Matter articles. Equal. Divers. Inclus. 36, 720–735. doi: 10.1108/EDI-01-2017-0010

Lin, S.-Y. (2017). White Americans' Legitimizing Reasoning of Police Violence: In Defense of America's Moral Image and Maintenance of Racial Hierarchy (Publication No. 10618027). (Doctoral dissertation) Bethlehem, PA: Lehigh University.

Long, J. S., and Ervin, L. H. (2000). Using heteroscedasticity consistent standard errors in the linear regression model. Am. Statist. 54, 217–224. doi: 10.1080/00031305.2000.10474549

Lowery, W. (2016). They Can't Kill Us All: Ferguson, Baltimore, and a New Era in America's Racial Justice Movement. Boston, MA: Little, Brown, and Company.

Mason, W., and Suri, S. (2012). Conducting behavioral research on Amazon's Mechanical Turk. Behav. Res. Methods 44, 1–23. doi: 10.3758/s13428-011-0124-6

Mazumder, S. (2019). Black Lives Matter for Whites' racial prejudice: assessing the role of social movements in shaping racial attitudes in the United States. SocArXiv. doi: 10.31235/osf.io/ap46d

McGarty, C., Thomas, E. F., Lala, G., Smith, L. G. E., and Bliuc, A.-M. (2014). New technologies, new identities, and the growth of mass opposition in the Arab Spring. Politi. Psychol. 35, 725–740. doi: 10.1111/pops.12060

Meyer, D. S., and Staggenborg, S. (1996). Movements, countermovements, and the structure of political opportunity. Am. J. Sociol. 101, 1628–1660. doi: 10.1086/230869

Miller, D. A., Cronin, T., Garcia, A. L., and Branscombe, N. R. (2009). The relative impact of anger and efficacy on collective action is affected by feelings of fear. Group Proc. Intergroup Relat. 12, 445–462. doi: 10.1177/1368430209105046

Moskalenko, S., and McCauley, C. (2009). Measuring political mobilization: the distinction between activism and radicalism. Terror. Polit. Viol. 21, 239–260. doi: 10.1080/09546550902765508

Movement for Black Lives (2016). A Vision for Black Lives: Policy Demands for Black Power, Freedom, & Justice. Available at: https://cjc.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/A-Vision-For-Black-Lives-Policy-Demands-For-Black-Power-Freedom-and-Justice.pdf

Mutz, D. C. (2022). Effects of changes in perceived discrimination during BLM on the 2020 presidential election. Sci. Adv. 8:eabj9140. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abj9140

Ocasio, B. P. (2016). Police Group Director: Obama Caused a ‘War on Cops.' Arlington, VA: Politico. Available at: https://www.politico.com/story/2016/07/obama-war-on-cops-police-advocacy-group-225291.

Osborne, D., Jost, J. T., Becker, J. C., Badaan, V., and Sibley, C. G. (2018). Protesting to challenge or defend the system? A system justification perspective on collective action. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 49, 244–269. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2522

Osborne, D., Smith, H. J., and Huo, Y. J. (2012). More than a feeling: Discrete emotions mediate the relationship between relative deprivation and reactions to workplace furloughs. Person. Soc. Psychol. Bullet. 38, 628–641. doi: 10.1177/0146167211432766

Parker, K., Horowitz, J. M., and Anderson, M. (2020). Amid Protests, Majorities Across Racial and Ethnic Groups Express Support for the Black Lives Matter Movement. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2020/06/12/amid-protests-majorities-across-racial-and-ethnic-groups-express-support-for-the-black-lives-matter-movement/

Peay, P. C., and Camarillo, T. (2021). No justice! Black protests? No peace: the racial nature of threat evaluations of nonviolent #BlackLivesMatter protests. Soc. Sci. Quart. 102, 198–208. doi: 10.1111/ssqu.12902

Peay, P. C., and McNair, C. R. (2022). Concurrent pressures of mass protests: the dual influences of #BlackLivesMatter on state-level policing reform adoption. Polit. Groups Identi. 12, 277–301. doi: 10.1080/21565503.2022.2098148

Peffley, M., and Hurwitz, J. (2010). Justice in America: The separate realities of Blacks and Whites. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Petersen, M. B., Osmundsen, M., and Arceneaux, K. (2023). The “need for chaos” and motivations to share hostile political rumors. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 117, 1486–1505. doi: 10.1017/S0003055422001447

Peterson, C., Maier, S. F., and Seligman, M. E. P. (1993). Learned Helplessness: A Theory for the Age of Personal Control. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Quinless, F. W., and McDermott Nelson, M. A. (1988). Measure of learned helplessness. Nurs. Res. 37, 11–15. doi: 10.1097/00006199-198801000-00003

Rasmussen Reports (2015). 58% Think There's a War on Police in America Today. Available at: http://www.rasmussenreports.com/public_content/lifestyle/general_lifestyle/august_2015/58_think_there_s_a_war_on_police_in_america_today

Rasmussen Reports (2020). Most Want ‘Blue Lives Matter' Laws to Protect Police, Fear for Public Safety. Available at: https://www.rasmussenreports.com/public_content/politics/general_politics/september_2020/most_want_blue_lives_matter_laws_to_protect_police_fear_for_public_safety

Richardson, I., and Conway, P. (2022). Standing up or giving up? Moral foundations mediate political differences in evaluations of BLACK LIVES MATTER and other protests. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 52, 553–569. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2837

Riley, E. Y., and Peterson, C. (2020). I can't breathe: Assessing the role of racial resentment and racial prejudice in Whites' feelings toward Black Lives Matter. Nat. Rev. Black Polit. 1, 496–515. doi: 10.1525/nrbp.2020.1.4.496

Sawyer, J., and Gampa, A. (2018). Implicit and explicit racial attitudes changed during Black Lives Matter. Person. Soc. Psychol. Bullet. 44, 1039–1059. doi: 10.1177/0146167218757454

Silver, E., Goff, K., and Iceland, J. (2022). Social order and social justice: moral intuitions, systemic racism beliefs, and Americans? divergent attitudes toward Black Lives Matter and police. Criminology 60, 342–369. doi: 10.1111/1745-9125.12303

Skoy, E. (2020). Black Lives Matter protests, fatal police interactions, and crime. Contemp. Econ. Policy 39, 280–291. doi: 10.1111/coep.12508

Smith, G., Ax, J., and Kahn, C. (2020). Exclusive: Most Americans Sympathize With Protests, Disapprove of Trump's Response. London: Reuters. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-minneapolis-police-poll-exclusive/exclusive-most-americans-sympathize-with-protests-disapprove-of-trumps-response-reuters-ipsos-idUSKBN239347

Smith, H. J., Pettigrew, T. F., Pippin, G. M., and Bialosiewicz, S. (2012). Relative deprivation: a theoretical and meta-analytic review. Person. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 16, 203–232. doi: 10.1177/1088868311430825

Solomon, J., Kaplan, D., and Hancock, L. E. (2019). Expressions of American White ethnonationalism in support for Blue Lives Matter. Geopolitics. 26, 946–966. doi: 10.1080/14650045.2019.1642876

Solomon, J., and Martin, A. (2019). Competitive victimhood as a lens to reconciliation: an analysis of the Black Lives Matter and Blue Lives Matter movements. Confl. Resol. Quart. 37, 7–31. doi: 10.1002/crq.21262

Swencionis, J. K., and Goff, P. A. (2017). The psychological science of racial bias and policing. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 23, 398–409. doi: 10.1037/law0000130

Tausch, N., Becker, J. C., Spears, R., Christ, O., Saab, R., Singh, P., et al. (2011). Explaining radical group behavior: Developing emotion and efficacy routes to normative and nonnormative collective action. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 101, 129–148. doi: 10.1037/a0022728

Teixeira, C. P., Leach, C. W., and Spears, R. (2022). White Americans' belief in systemic racial injustice and in-group identification affect reactions to (peaceful vs. destructive) “Black Lives Matter” protest. Psychol. Viol. 12, 280–292. doi: 10.1037/vio0000425

Teixeira, C. P., Spears, R., and Yzerbyt, V. Y. (2020). Is Martin Luther King or Malcolm X the more acceptable face of protest? High-status groups' reactions to low-status groups' collective action. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 118, 919–944. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000195

Tillery, A. B. (2019). What kind of movement is Black Lives Matter? The view from Twitter. J. Race, Ethn. Polit. 4, 1–27. doi: 10.1017/rep.2019.17

Torcal, M., and Montero, J. R. (2006). Political Disaffection in Contemporary Democracies: Social Capital, Institutions, and Politics, eds. M. Torcal and J. R. Montero (London: Routledge).

Tyler, T. R., Goff, P. A., and MacCoun, R. J. (2015). The impact of psychological science on policing in the United States: procedural justice, legitimacy, and effective law enforcement. Psychol. Sci. Public Inter. 16, 75–109. doi: 10.1177/1529100615617791

U.S. Crisis Monitor (2020). US Crisis Monitor Releases Full Data for Summer 2020. ACLED. Available at: https://acleddata.com/2020/08/31/us-crisis-monitor-releases-full-data-for-summer-2020/

United States Department of Justice Civil Rights Division (2016). Investigation of the Baltimore City Police Department. Available at: https://www.justice.gov/crt/file/883296/download

United States Department of Justice Civil Rights Division (2017). Investigation of the Chicago Police Department. Available at: https://www.justice.gov/opa/file/925846/download

Updegrove, A. H., Cooper, M. N., Orrick, E. A., and Piquero, A. R. (2020). Red states and Black lives: applying the racial threat hypothesis to the Black Lives Matter movement. Justice Quart. 37, 85–108. doi: 10.1080/07418825.2018.1516797

Updegrove, G. F., Mourad, W., and Abboud, J. A. (2018). Humeral shaft fractures. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 27, 87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2017.10.028

Vaughn, P. E., Peyton, K., and Huber, G. A. (2022). Mass support for proposals to reshape policing depends on the implications for crime and safety. Criminol. Public Policy 21, 125–146. doi: 10.1111/1745-9133.12572

Vitriol, J. (2016). The (In)Egalitarian Self: on the motivated rejection of implicit racial bias (Manuscript submitted for publication).

Vitriol, J. A., Reifen Tagar, M., Federico, C. M., and Sawicki, V. (2019). Ideological uncertainty and investment of the self in politics. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 82, 85–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2019.01.005

Weigel, D., and Zezima, K. (2015). Cruz leads a GOP Backlash to “Black Lives Matter” Rhetoric. Washington, DC: The Washington Post. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-politics/wp/2015/09/01/cruz-leads-a-gop-backlash-to-black-lives-matter-rhetoric/?utm_term=.8bec26c7b703

West, K., Greenland, K., and Laar, C. (2021). Implicit racism, colour blindness, and narrow definitions of discrimination: why some White people prefer ‘All Lives Matter' to ‘Black Lives Matter.' Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 60, 1136–1153. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12458

Keywords: protest (causes), democratic attitudes, intergroup attitude, Black Lives Matter, criminal justice

Citation: Vitriol JA, Sandor J and Farhart CE (2024) Black and Blue: how democratic attitudes shape affect toward Blue or Black Lives Matter. Front. Soc. Psychol. 2:1417995. doi: 10.3389/frsps.2024.1417995

Received: 15 April 2024; Accepted: 20 November 2024;

Published: 13 December 2024.

Edited by:

Kimberly Rios, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, United StatesReviewed by:

Julian Rucker, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, United StatesBrier Gallihugh, Ohio University, United States

Copyright © 2024 Vitriol, Sandor and Farhart. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Joseph A. Vitriol, am9ldml0cmlvbEBnbWFpbC5jb20=

†Present address: Joseph A. Vitriol, Department of Management, Business School at Lehigh University, Bethlehem, PA, United States

Joseph A. Vitriol

Joseph A. Vitriol Joseph Sandor

Joseph Sandor Christina E. Farhart

Christina E. Farhart