- Defense Analysis Department, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, CA, United States

Russia's invasion of Ukraine and China's escalatory threats to use military force to annex Taiwan underscore the importance of resilience building in smaller nations vulnerable to expansionist powers. Despite a renewed focus among scholars and practitioners on building resilient societies, there is a gap in our current understanding of the psychological resilience a populace needs to defend and strengthen sovereignty. To help fill this gap, this article focuses on social and organizational psychology theory and research to explore (a) individual psychological motivations and (b) individual and societal capabilities that can strengthen national resilience before, during, and after a crisis (namely invasion). As a framework I use Significance Quest Theory, one of the foremost social psychological theories that synthesizes previous research on motivation. I use Mongolia, an economically and militarily smaller democratic nation bounded by authoritarian Russia and China, as a case example and incorporate quantitative survey data from Mongolians using the World Values Survey database. This paper provides a conceptual foundation of psychological resilience that future research can build upon and later integrate with other social science disciplines to further refine our understanding of how smaller nations can preserve sovereignty in the face of pressures from stronger powers.

Introduction

Small is dangerous. This axiom of international relations remains as true today as it was a thousand years ago. Small generally equates to weak, and weakness attracts unwanted attention from those desiring to accumulate more territory and resources. In the current century, like previous ones, the powerful get what they want through traditional military force and diplomacy, plus modern tools of information power (such as social media and other digital activities), and economic statecraft. These basic tenants of national power have long been studied by the “realpolitik” school of international relations (Dougherty and Pfaltzgraff, 1997) that traces its roots back to Thucydides' writings on the Peloponnesian War in the 4th century BCE and runs through recent scholarship on the rise of China (Allison, 2018).

However, sometimes powerful states overestimate their own strength and underestimate the hidden power of others. For instance, Afghanistan, known as the “graveyard of empires” has always been small and weak compared to its neighbors (Dupree, 1973). Yet in both 1990 and 2021 it showed it could again defeat two of the strongest military powers on earth, the USSR and United States. International relations studies are important for understanding why smaller nation-states sometimes prevail against larger powers, but they largely lack consideration of the psychological motivations and capabilities that foster resilient societies.

Resilience is a “fuzzy” term defined differently across academic disciplines and contexts. For this article resilience is defined as “the will of the people to maintain what they have; the will and ability to withstand external pressure and influences and/or recover from the effects of those pressures or influences (Fiala, 2019).” The context for this definition is rooted in security scholarship. Despite a renewed focus on resilience among security scholars and practitioners, most resilience building efforts concentrate heavily on civil preparedness for natural, accidental, or malicious disasters through infrastructure resource management, emergency response protocols, communication networks, and educating the public (Roepke and Thankey, 2019). This type of preparedness is necessary yet insufficient if individuals are not psychologically ready and motivated to maintain, withstand, and recover from crises to include invasion. Psychological resilience, like the term “resilience,” has been conceptualized in many different ways but most definitions in the psychology literature include two core concepts—adversity and positive adaptation. There is a robust research literature on psychological resilience in domains of health and wellbeing, sports, business, education, and economic and environmental sectors (Fletcher and Sarkar, 2013), but its application to how smaller nations can maintain and strengthen sovereignty in the face of pressures from stronger powers is limited (for discussion, see Houck, 2022).

To help fill these gaps, this article focuses on social and organizational psychology theory and research to explore (a) individual psychological motivations and (b) individual and societal capabilities essential for psychological resilience before, during, and after a crisis (specifically invasion). For this I turn to one of the foremost social psychological theories that synthesizes previous research on motivation: Significance Quest Theory (Kruglanski et al., 2019). I use Mongolia, an economically and militarily weaker democratic nation bounded by authoritarian Russia and China, as a case example. The scope of this work focuses on psychology specifically, but ideally future research can incorporate cross-disciplinary perspectives to build upon this conceptual foundation.1 To illustrate why Mongolia is a useful initial case example requires elaboration on its historical context.

The case of mongolia: background

After nearly 2 centuries of Chinese rule, Mongolia declared its independence from China's Qing dynasty in 1911. Yet just a decade later it found itself tied to its Northern communist neighbor when Mongolia became a Soviet satellite—Asia's first socialist country. After decades of heavy Soviet dominance like that experienced in Eastern Europe, the winter of 1989–1990 marked a critical turning point as a non-violent resistance movement emerged in Mongolia against continued external Soviet control and internal Marxist rule. Like the revolutions in Eastern Europe, during the months of December through May, citizens gathered in Sukhbaatar Square in the capital city Ulaanbaatar to peacefully demonstrate their support for democracy. They held banners displaying images of Chinggis (Genghis) Khan, a singularly important cultural icon long suppressed under Marxist rule. The protestors also unveil what would later become Mongolia's new flag, and emblem absent the communist star it once depicted (see Figure 1, before and after flags). Shortly afterward, Mongolia held its first multi-party elections in 1990, and later and passed a democratic constitution in 1992 (Global Nonviolent Action Database, n.d.).

With the democratic movement's success, however, came many challenges.

Indeed, Mongolia's transition to democracy is a time known as “the hard years.” As Mongolian author of The Secret Driving Force Behind Mongolia's Successful Democracy writes: “Given the hardships our people faced, nostalgia about our communist past could have surged. But it did not. Mongolians agreed with then President Ochirbat's call, ‘to tighten our belts,' and proceed further with democratic changes and the development of a market economy” (Tsedevdamba, 2016). Significant political and economic challenges persist today, intensified by the strategic competition between the U.S. and Mongolia's direct neighbors, China and Russia (Jargalsaikhan, 2017).

Mongolian democracy between authoritarian China and Russia

“Ukraine is fighting an overt war, while Mongolia is fighting a covert war, to protect our freedom.” – Former Mongolian President Elbegdorj Tsakhia (2022)

A liberal democracy is “a political system marked not only by free and fair elections, but also by the rule of law, separation of powers, and the protection of basic liberties of speech, assembly, religion, and property (Zakaria, 1997).” In contrast, authoritarian regimes are “political systems with limited, not responsible, political pluralism: with-out elaborate and guiding ideology (but with distinctive mentalities); without intensive nor extensive political mobilization (except at some points in their development), and in which a leader (or occasionally a small group) exercises power within formally ill-defined limits but actually quite predictable ones” (p. 297). By these definitions, Mongolia is a liberal democracy; Russia and China are authoritarian regimes.

Whether Mongolia can maintain its sovereignty for the long-term in the face of potential pressures from authoritarian Russia and China under Presidents Putin and Xi remains to be seen. Russia's revanchist mindset against former Soviet states (Snegovaya and Lanoszka, 2022; Kok-Kheng, 2022) is apparent through its invasions of Georgia in 2008 (Dickinson, 2021), the Ukrainian region of Crimea in 2014 (Muradov, 2022), and Ukraine in 2022 (Miller and Tabachnik, 2023). Likewise, the Communist Party of China (CCP) today, over 70 years after annexing Tibet, imperiously monitors Tibetan behavior (Hennig, 2023), as evidenced by the 2022 CCP-issued directive to all districts in the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) that demands its citizens remain unwaveringly loyal to the CCP and reject the Dalai Lama and his followers (Panda and Pankaj, 2023; Shah, 2022). In the same year China reaffirmed its threats to use military force to annex Taiwan (Amonson and Egli, 2023). These actions by two stronger powers that geographically surround Mongolia provide a cautionary tale for Mongolian democracy and sovereignty. As historian James Millward aptly notes: “…Mongolia's independent political status challenges the CCP historical narrative that everything once part of the Qing Dynasty [1636–1912] is now part of the PRC—the very argument underpinning Beijing's assertions about Taiwan.”

To be clear, there is no definitive evidence that either Russia or China have active programs in place to influence the Mongolian democratic system, however, scholars and practitioners have raised concerns about this possibility for several reasons (e.g., see Adiya, 2023; Lkhagvasuren, 2022). First, Mongolia is sparsely populated, geographically confined, and heavily economically dependent on both China and Russia. Mongolia serves as a key transport corridor between China, Russia, and Europe and exports an estimated 85%−90% of its goods (mostly minerals) to China. It is similarly dependent on both China and Russia for its imports. Moreover, China accounts for the largest segment of foreign direct investment (FDI) in Mongolia, while Russia provides 92 percent of Mongolia's energy (Lkhaajav, 2021). Russian banks facilitate most of Mongolia's foreign trade (Stanway, 2022). Most recently, the “Power of Siberia 2” gas pipeline will use Mongolian territory to transport gas from Russia to China (Roy and Kumar, 2023). China and Russia's economic leverage over Mongolia makes them well-positioned to exert influence in non-economic domains, including politics and culture. In their 2023 article in the Journal of Strategic Studies, Wong et al. state: “Beijing can leverage economic ties to punish critics and reward supporters, shape vested interest groups that fall in line with Beijing's wishes, influence broader public and elite opinion, and set market standards.” For example, when the Dalai Lama visited Mongolia in 2016, China closed a China-Mongolia border crossing, imposed fees on Mongolian imports, suspended bilateral talks and a $4.2 billion economic loan. Consequently, Mongolia agreed it would not invite the Dalai Lama back to Mongolia (Frederick and Shatz, 2022; Pieper, 2020; Wong et al., 2023). Mongolia's access to the Chinese market and Chinese economic support is contingent on its non-interference with issues pertaining to Tibet, Xinjiang, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region of Northern China Inner Mongolia (Tsolmon, 2024). Meanwhile, in Inner Mongolia, home to ethnic Mongolians, China has recently suppressed the teaching of the Mongolian language in schools, and imposed Mandarin, China's official language. This policy impacts the more than 4 million ethnic Mongolians living in Inner Mongolia. In 2020, protests erupted in response; Chinese authorities swiftly cracked down on Mongolian protests, making arrests and threatening families with job losses and other penalties (Ekstrom, 2023).

Russia is similarly impacting Mongolian ways of life. During his 2019 visit to Mongolia to sign a “permanent treaty on friendship and extensive strategic partnership,” Russian President Vladimir Putin said: “Today, Russian-Mongolian cooperation is comprehensive and multilateral, and covers the political, trade, economic, investment, financial, agricultural, scientific, educational, cultural, and sports areas (Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty, 2019).”

Second, there is robust evidence of Russian and Chinese disinformation campaigns in the Asia-Pacific to include Mongolia (Chultemsuren and Aldar, 2022; Lee, 2022; Polyakova and Meserole, 2019; Lkhagvasuren, 2022; Tzu-Chieh and Tzu-Wei, 2022; Weber, 2019). Dorj Shurkhuu, former director of the Institute of International Studies at the Mongolian Academy of Sciences, summarized these concerns in her 2021 interview, stating that “Russia and China have a common interest in keeping Mongolia in a vacuum… It is a question about who will control Mongolia militarily, financially, culturally, linguistically, and even civilizationally (Pieper, 2020, p. 760).”

Strength in diplomacy: Mongolia's efforts to maintain independence

According to Mongolia's National Security Concept, “the prime purpose of ensuring national security shall be safeguarding and guaranteeing national independence, sovereignty and unity” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Mongolia, n.d.). Mongolia accomplishes this in part due to its ability to effectively balance diplomatic relations with Russia and China through its “Third Neighbor” foreign policy. “Third Neighbors” refer to countries (other than Russia and China) that Mongolia has built relationships with—amongst others Japan, India, U.S., Turkey, Germany, South Korea, Canada, and Australia—all of which support liberal democracy (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Mongolia, n.d.). Mongolia also has long-standing good diplomatic relations non-democratic “Third Neighbors” such as North Korea. Indeed, “Mongolia is one of the few countries on earth that has good relations with all of the most relevant powers in Northeast Asia and South Asia (Andregg, 2021, p. 167–173).”

In addition to investing in third neighbor relations, Mongolia also strives to remain neutral with respect to Russia and China (Nyamtseren, 2024). In 2015, under President Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj, the Mongolian Government pursued a “permanent neutrality” status, which was heavily debated and ultimately nullified in 2020. Neutrality, whether official policy or intended strategy, cannot ensure Mongolia's security long-term. According to Jang and Kim (2023), “even if Mongolia pursues a permanent neutral nation policy, Russia and China can invade Mongolia anytime they want, and the possibility that the international community will not be able to guarantee Mongolia's security has increased.” It can also draw criticism when neutrality is in Mongolia's national interests but controversial among third neighbors. Consider, for example, Vladimir Putin's September 2024 invited visit to Mongolia. Putin, wanted in International Criminal Court (ICC) for his alleged mass deportation of Ukrainian children, was ceremoniously welcomed in Mongolia despite calls from Ukraine and others in the international community for Mongolia to arrest Putin, arguing it was Mongolia's obligation as a member of the ICC (Edwards, 2024).

Though Mongolia often defers to its border states as a political necessity, overall, Mongolian political leadership and the populace stands in support of democracy and independence. In a 2021 survey conducted by the International Republican Institute's (IRI) Center for Insights in Survey Research, 72% of Mongolian respondents (N = 2,500) reported that democracy is their preferred form of government (IRI Mongolia Poll, 2021). According to the Bertelsmann Stiftung's Transformation Index (BTI) 2022 report: “Mongolians have overwhelmingly approved the notion of a democratic regime since 1990. Several opinion surveys confirm that 85% to 90% of Mongolians regard democracy as the best form of government (BTI, 2022).”

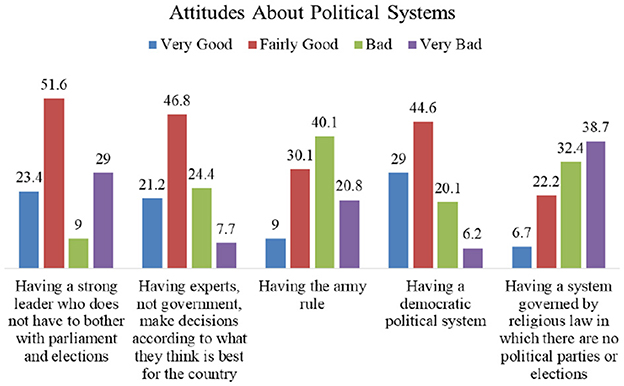

However, we would be remiss to exclude other data that suggest a more complex picture. Findings from the 2017–2022 World Values Survey (detailed more extensively later in this paper) show that 75% of Mongolians viewed “having a strong leader who does not have to bother with Parliament or elections” as either “very good” or “fairly good” compared to the 73.6% who agreed that “having a Democratic political system” is “very good” or “fairly good.” Moreover, many Mongolian youth are dissatisfied with the current government's handlings on several key issues spanning from limited economic opportunities, corruption scandals, and overall youth health (Batsaikhan et al., 2018). In her article covering the April 2022 youth protest, Mongolian researcher Bolor Lkhaajav writes: “An overriding demand is to alter government policies in order to promote and support the youth as opposed to the conglomerates that have benefitted from the government for decades (Lkhaajav, 2022).”

Strength in resilience: efforts to build a resilient Mongolia

Recognizing these vulnerabilities of a relatively young democracy, many entities have worked to build resilience by addressing some of the pressing societal problems across urban and rural regions. Most of the resiliency building efforts in Mongolia are not well documented in English language sources, but the literature that is publicly available suggests a focus on education, economic diversification, disaster preparedness, food security, and energy security (Mercy Corps, 2017). These efforts share similarities with Japan's “Fundamental Plan for National Resilience” thought Japan has a legally formalized national resilience plan (Cabinet Decision, 2014). Mongolia may already be following suit. In a 2024 Mongolian National News report, the Mongolian President said, “it is time to develop and implement a ‘National Resilience Building Strategy' based on defense and disaster management systems (Montsame, 2024).” Moreover, the Mongolian Journal of Strategic Studies recently published an issue (in Mongolian language), on resilience concept in the Mongolian context, spanning topics such as the resilience capacity of the state, cyber resilience, economic resilience, and environmental resilience to name a few (Jargalsaikhan, 2023).

These efforts reveal Mongolia's commitment to physical and organizational readiness, while also showing a commitment to resiliency by adaptation to political, social, and environmental changes. These efforts, however, have not yet deliberately addressed individual psychological resilience. Recent Mongolian scholarship accentuates this point. According to Lkhagvasuren (2022): “Mongolian national defense policies have relied on conventional military forces for decades, but those policies do not include the psychological preparation and involvement of the Mongolian population.” How Mongolia pursues this line of effort going forward can be informed by psychological research and theory.

Psychological resilience

Cultivating a collective sense of psychological resilience in any society requires individual-level efforts. This idea is underscored in the Resistance Operating Concept, a document published by Swedish Defense University:

National resilience begins with the individual. To the greatest extent possible, every member of society should be capable of avoiding, and if necessary, caring for themselves during a crisis. Resilient individuals are also better able, and generally more willing, to contribute to whole-of-society efforts (Fiala, 2019, p. 5).

Although some people have personality traits that make them inherently more resilient than others, research suggests resilience is not just a static trait; it is also a process. It can change over time and across contexts (Fletcher and Sarkar, 2013). This malleability underscores the importance of sustained efforts to foster resilient individuals, communities, and ultimately nations. Beginning with the individual, efforts ought to emphasize whole-of-person psychological resilience. At a minimum it should account for an individual's cognitive, emotional, and social capabilities and motivations. One might have the cognitive capacity, emotional fortitude, and social connections to engage in resiliency building activities, but these capabilities render little utility absent the motivation to participate. Likewise, motivation alone is insufficient; one must be properly equipped to act on their motivations. This highlights two important questions for understanding resilience at an individual level. First, why do people defend sovereignty during peacetime (motivations for resiliency)? Second, what do people need to successfully defend sovereignty during peacetime (capabilities for resiliency)? We address both questions from a psychological perspective and apply key concepts to Mongolia.

The will to defend: psychological motivations

For over a century, scholars have theorized about what drives behavior. Some emphasize motivation as a function of arousal (Yerkes and Dodson, 1908), instinct (McDougall, 1932), physiological needs (Hull, 1943), hierarchical needs spanning physiological to esteem (Maslow, 1943) cognitive consistency (Festinger, 1957), incentives (Deci, 1971), and evolution (Schaller et al., 2017). At the root of most major theories of motivation is the idea that humans share basic needs. Some of these universal needs are biological (i.e., hunger, hydration, rest, and reproduction) and others psychological (i.e., belonging, achievement, autonomy, and value). Both categories motivate action. For example, whereas the biological need for rest motivates one to sleep, the psychological need for belonging motivates friendships. According to Kruglanski et al. (2019); “the myriad of people's specific goals that vary widely across cultures and societies may be thought of as culturally specific means to the same universal needs: satisfaction of people's basic biological and psychogenic needs.” To understand motivations for resilience, or why people defend sovereignty, we can consider the universal psychological needs it satisfies. For this we turn to one of the foremost social psychological theories that synthesizes previous research on motivation: Significance Quest Theory (Kruglanski et al., 2019).

Significance quest theory posits that significance—an individual's desire to matter and have social worth—is a universal human need satisfied by embodying the values of one's social group. This need becomes more prevalent when personal feelings of significance are threatened, whether by rejection, loss of social identity (Sageman, 2004), humiliation (Pedahzur, 2005), intergroup conflict (Speckhard and Paz, 2012), exclusion (Pretus et al., 2018), war (Kulyk, 2023), or some other form of assault to the group's values (for discussion, see Houck, 2022). Such threats are clear in the case of Mongolia, where, as previously discussed, cultural practices and economic freedom are under progressive pressures from China and Russia.

Just as significance loss activates significance quests, so too can opportunities for significance gain activate behavior. From this we see superior leaders emerge to defend or promote their group's values. For example, Mongolian history highlights no other leader more than Chinggis Khan, revered by Mongolians as the founder of the Mongol Empire who united nomadic tribes and in doing so came to power, which he greatly expanded through his notorious conquests. Consider a recent example. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky has become a symbol for what it means to be Ukrainian, refusing to concede to Putin and fighting back against the Russian invasion (Zachara-Szymańska, 2023).

Although significance quests are universal, the specific means by which one attains a sense of meaning and social worth largely depend on the sociocultural context. This is shaped by narratives. Cultural narratives signal the values one must strive for to be significant in a social group. Whereas militaries promote discipline, hard work, and self-sacrifice to live up to service expectations, extremist groups may espouse violence to fulfill the group's ideological objectives. In turn, the social group, or network, lends credibility to the narrative and reinforces individuals who demonstrate commitment to the group's values. War heroes are honored with awards and ceremonies; terrorist networks venerate suicide bombers who become idols for new recruits.

The significance quest theory demonstrates the connections between individual motivations, actions, and collective values. Thus, psychological resiliency-building efforts require both recognition and validation of the deeply held values in a society so that national narratives can echo those values. Recent data from the World Values Survey highlight several important values in Mongolian society (Haerpfer et al., 2022).

Mongolian values: world values survey results (2017–2022)

The World Values Survey (WVS) is “a global network of social scientists studying changing values and their impact on social and political life, led by an international team of scholars.” WVS conducts in-person surveys across the globe using a common questionnaire assessing various opinions. All data are open-source and can be accessed on the WVS webpage, which also includes a detailed description of data collection methods.2

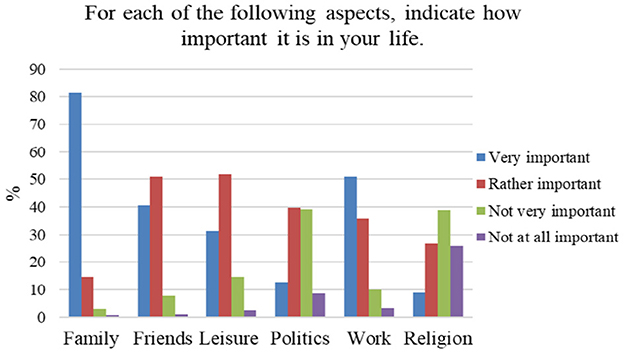

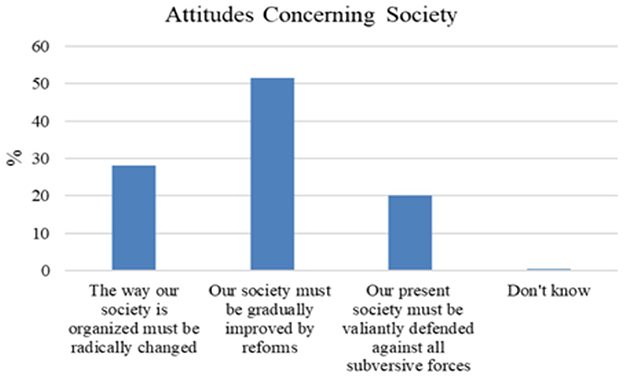

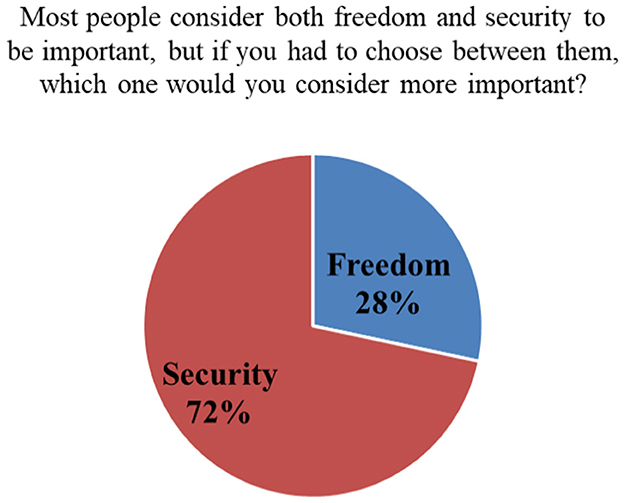

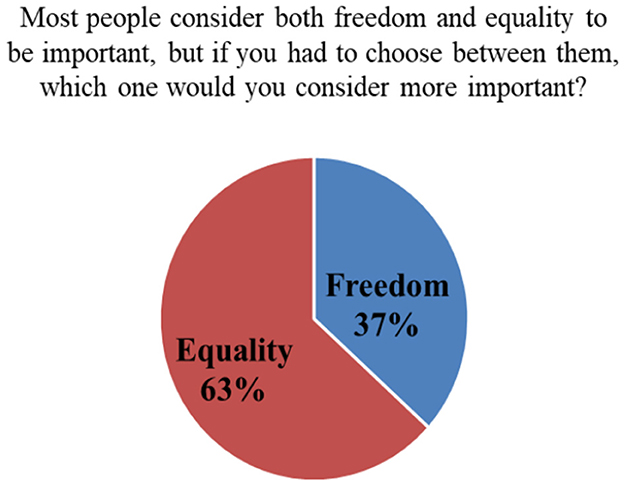

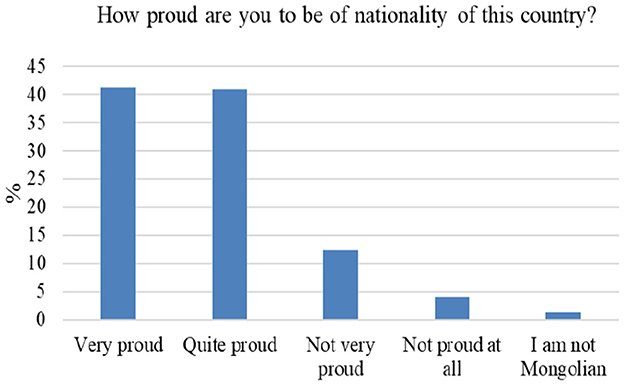

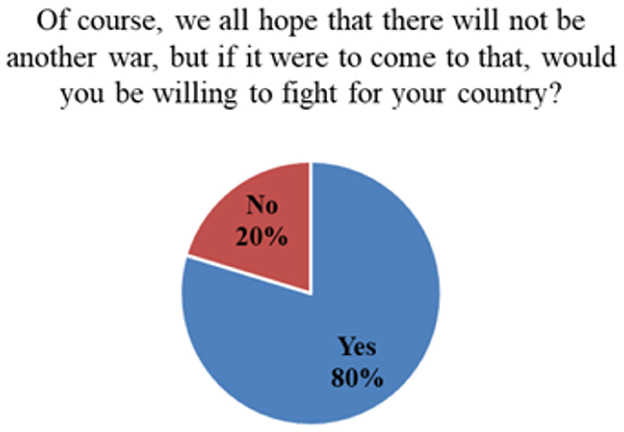

To capture a broad picture of Mongolian values, we examined data collected in the 7th wave of the WVS (2017–2022).3,4 In this sample of 1,638 Mongolians (Ages Ranges: [up to age 29] = 30%; [age 30–49] = 45.2%; [age 50 or more] = 24.8%; Sex: [Males] = 48.4%, [Females] = 51.6%), respondents ranked family as the most important value, followed by work and friends. Leisure, politics, and religion were least important. Of the societal attitudes participants were asked about, 51.5% agreed that “society must be gradually improved by reforms,” 28% agreed that “the way our society is organized must be radically changed,” and 20.1% thought “our present society must be valiantly defended against all subversive forces.” Compared to the 73.6% who viewed “Having a Democratic political system” as either “very good” or “fairly good,” 75% thought it “very good” or “fairly good” to “have a strong leader who does not have to bother with Parliament or elections.” Moreover, when asked to choose between freedom and security and, separately, between freedom and equality, both security and equality were viewed as more important than freedom. Finally, the majority (82.3%) reported feeling “very proud” or “quite proud” to be Mongolian, which is likely related to the high level of reported willingness to fight for one's country (80%). See Figures 2–8 for a summary.

These survey data shed light on some of the narrative themes likely to resonate with Mongolian's individual motivations and collective values. Mongolian national narratives should reflect the importance Mongolians place on family and work, security and equality, strong leadership, and pride in national identity. These findings also suggest it may be a mistake to shape narratives around politics, religion, and freedom. That said, it is important not to over-interpret these data given the limitations associated with survey data in general and these data specifically. Namely, these data were collected prior to Russia's invasion of Ukraine, a significant event that could arguably make freedom more salient to Mongolians. To increase confidence in these survey findings, current and more in-depth data collection on large, representative samples is merited.

The will to defend: psychological capabilities

Motivation is critical to resilience but insufficient on its own. Resilient individuals must also be capable of defending their sovereignty. Resilience capabilities include things like economic resourcing, communication networks, support to infrastructure, etc., all of which have been written about extensively in the context of natural disaster preparedness. However, it is less understood what psychological capabilities societies require to maintain and increase the will to defend sovereignty. To address this gap, we draw from diverse bodies of research in sports psychology (resilience in athletic competition), organizational psychology (business and management resilience), and social psychology (resilience and group dynamics) to inform psychological resilience in the context of national security across three phases of a crisis/invasion: anticipation, coping, and adaptation (Duchek, 2020).

Anticipation pre-crisis: the psychology of uncertainty

“Learning to live with uncertainty requires building a memory of past events, abandoning the notion of stability, expecting the unexpected, and increasing the capability to learn from crisis.” (Berkes, 2007, p. 288)

Whether in government, business, sports, or other realms, life is filled with uncertainty. Efforts to reduce uncertainty tend to focus on anticipating changes by monitoring current conditions (e.g., through environmental scanning, research, and intelligence gathering) and identifying changes in conditions (e.g., threat detection). Observation and identification are important anticipatory capabilities. However, while forecasting potential future threats allows for advanced planning and rehearsing (which is better than reacting once a crisis hits), doing so is no easy task. Preparing without knowing if, when, where, or how a threat will occur is psychologically challenging, primarily because experiencing uncertainty is aversive and anxiety-provoking (Sodi et al., 2021). Studies show that uncertainty is linked to decreases in motivation, focus, cooperation, and sense of purpose. Consider, for example, that the reality of losing a job has less of a negative impact on one's overall health than experiencing job uncertainty (Robinson, 2022). Similar effects occur for athletes. Sports medicine research on decision-making during endurance competitions revealed that runners were most likely to slow their pace and “give in to pain” when faced with uncertain conditions during a race (Gutiérrez-Dávila et al., 2013; Magness, 2015a, 2022; Peng et al., 2023). On the other hand, having a higher tolerance for uncertainty is associated with positive health outcomes (Strout et al., 2018), effective leadership (White and Shullman, 2010), job performance and creativity (O'Connor et al., 2018). These findings suggest that developing psychological capabilities to deal with uncertainty is equally important for preparation as observation and identification skills.

Fortunately, people can learn to navigate uncertainty. Top athletes intentionally train for it. Steve Magness, performance expert and author of “Do Hard Things: Why We Get Resilience Wrong and the Surprising Science of Real Toughness,” writes: “Similar to how we adapt to the stress of a physical workout by increasing the strength of our muscle fibers, building mitochondria, or producing more red blood cells, our brains adapt to the stress of uncertainty, by adjusting our stress response, establishing and reinforcing memory connections, and being better equipped to handle that formerly uncertain situation (Magness, 2015b, 2022).” With mere exposure to uncertainty comes more preparedness, not necessarily for specific incidents, but for the discomfort that unanticipated incidents may bring.

In the same ways athletes train for uncertainty that they may face during competition, societies must also “train” for the unexpected. One way to develop this capability is through scenario planning and simulation that intentionally inject elements of uncertainty. This not only helps participants learn procedures and practice their responses, but it also provides a forum for participants to develop important relationships with others involved in planning and preparation processes. Fostering relationships across government entities (military and political), non-government organizations, and civilian sectors of society is key (Lkhagvasuren, 2022).

“Gobi Wolf” is one of many annual training exercises in Mongolia aimed at preparing for uncertain future events. Its purpose is for government organizations to learn crisis management skills during emergency situations and disasters that occur in Mongolia (U.S. Embassy in Mongolia, n.d.). Preparedness in this domain is especially important given that climate change has increased uncertainty among nomadic agricultural and pastoral communities in Mongolia. A “dzud” is a “winter disaster in which deep snow, severe cold, or other conditions that render forage unavailable or inaccessible lead to high livestock mortality (Fern?ndez-Gimenez et al., 2012).” The growing frequency of dzuds over the last two decades have significantly impacted Mongolia's traditional herding lifestyle, leading many Mongolian youth to leave the uncertain pasturelands for jobs in urban areas (Hahn, 2017). The move from nomadic to urban areas continues to stress municipal services in cities not designed for the increasing number of people. This shift also affects traditional religious and cultural connections to the nomadic lifestyle. Disaster preparedness frameworks taught during Gobi Wolf and similar exercises could be adapted to train for the unique uncertainties that coincide with invasion.

Moreover, Mongolia's National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) has already established early warning systems through several communication channels—the media, internet, national radio—to alert the public to potential storms and flooding. This system could also work for communicating security threats (Asian Development Bank, 2020). In doing so, Mongolia would be better equipped to cope if ever invaded.

Coping during a crisis: the psychology of acceptance and unity

Resilient individuals display two essential coping skills during a crisis—the ability to accept what is happening and the ability to adopt a unified front to implement solutions. Psychological acceptance, or “the active embracing of subjective experience, particularly distressing experiences” is associated with positive psychological outcomes and adaptive coping strategies (e.g., Barnes-Holmes et al., 2004; Nakamura and Orth, 2005; Moran, 2011) but can also be cognitively challenging (Kabat-Zinn, 2005; Herbert et al., 2009). This is in part because acceptance requires a willingness to experience difficult emotions and thoughts without avoidance. When facing distressing events, suppression and denial are often more attractive than acceptance because avoidance offers temporary comfort. However, these strategies can lead to longer-term psychological distress (Herbert et al., 2009; Predko et al., 2023). Avoidance also slows action.

Consider a historical example. In 1933, the National Socialists assumed power in Germany and ushered in a series of laws that segregated Jews from “Aryan” society and systematically curtailed Jewish civil, political, and legal rights. Discussions about whether to remain in Germany under the Nazi regime or leave the country proliferated throughout the Jewish community. Most stayed, believing that the Nazi regime would not remain in power for long. It was not until the “Night of Broken Glass” in 1938—the day Nazis coordinated violent, widespread attacks against Jewish synagogues, schools, businesses, hospitals, homes, and people—that most German Jews realized the gravity of the threat and urgently tried to flee (Kwiet, 2019; Yahil, 1991). Of course, German Jews' decisions about remaining in their homeland or escaping during the 1930s were influenced by more than just denial. An analysis of 90 German and Austrian life histories solicited by Harvard researchers revealed several reasons why people “actively resisted recognition of the seriousness of the situation, or in cases where the seriousness was realized, failed at first to make a realistic adjustment to it (Allport et al., 1941, p. 3).” Findings suggest that many did not recognize the danger soon enough, and that the familiar circumstances at home outweighed the uncertainties associated with emigration. Other evidence points to shock and active avoidance, including suppression and escapism.

Recent research on Russia's invasion of Ukraine suggests a similar initial response among Ukrainians. Authors of “A full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022: Resilience and coping within and beyond Ukraine” note: “Until the last moment, most Ukrainian citizens and residents of the region received the invasion with disbelief (Kimhi et al., 2024, p. 1106).” These examples underscore the challenging nature of psychological acceptance when experiencing intensely distressing events.

Efforts made during the anticipation phase prepare people to implement solutions previously rehearsed, so there is logical overlap between the anticipation and coping phases of resilience building. But novel, unrehearsed solutions must also be developed to deal with the unanticipated aspects of crises. Organizational resilience research underscores the importance of bricolage, or the “capability to improvise and to solve problems creatively (Duchek, 2020).” For example, during the pandemic, businesses had to innovate ways to maintain operations when employees were working remotely, and production was slowed or halted altogether. Mongolian farmers, threatened by devastating winter dzud events and drought, must implement adaptive strategies to store forage and keep livestock from deathly exposure. Translated to a security context, non-military citizens resisting invading forces must use everything at their disposal. Consider some recent examples in Ukraine. One Ukrainian woman reportedly threw a jar of pickles from her balcony to crash a drone. Ukrainian farmers have used tractors to tow Russian tanks, and one brewery made Molotov cocktails in their bottles, re-labeling them “Putin is a Dickhead (Caldwell, 2022).” The Ukrainian military has showed success using innovative combat strategies on a larger scale, particularly with its use of low-cost, low-tech commercial drones (Jones et al., 2023; Chávez and Swed, 2023). These examples of bricolage—quickly innovating with whatever available resources one has during a crisis—is precisely what Mongolia must be prepared for if ever invaded.

Coordinated actions are even more impactful. The most successful groups are those that can unite to achieve a common goal. Cohesion is critical to success. In times of crisis, people are reminded of their shared identities, goals, and humanities. Such unification can reduce negative ingroup vs. outgroup attitudes (e.g., divides across urban-rural, ethnic, socioeconomic, or other divides) and create collective group identities. However, unity is not automatic and should never be presumed. Social psychology research has identified several mechanisms that help unify groups to collaborate more effectively (Allport, 1954; Pettigrew and Tropp, 2006, 2008; Sherif et al., 1961). Much of this research focuses on the power of contact (Pettigrew, 1998; Turner et al., 2007). Contact alone is often sufficient to reduce intergroup prejudice, but aside from simply getting different groups together, research points to four conditions of intergroup contact that can maximize effects: establishing common goals, dedication to cooperation, the development of equality in status, and the presence of institutional support (Pettigrew and Tropp, 2006; Sargent et al., 2022).

These conditions translate into four recommended actions for Mongolia. The first recommendation is to focus on common objectives. Common goals can promote a unified ingroup identity (Gaertner et al., 2011). National identity is foundational to psychological resilience. Thinking of oneself as a military officer working on border security issues, a politician campaigning to diversify economic opportunities, or a young herder looking for educational opportunities all focus on individual identities. But each of these can also be reframed to thinking of oneself as a Mongolian working with a team to confront pressing issues in Mongolia that impact everyone's pursuits, thus changing an “us vs. them” mindset to a “we” mentality. Individual motivations to collaborate might differ but emphasizing a clear overarching mission can assist in bridging differences and facilitating team productivity. Mongolia already has policy in place that explicitly focuses on national identity. Specifically, in 2020, the Government of Mongolia proposed “Vision-2050,” a policy that aims to foster national identity, preserve traditional language [Mongolia's traditional alphabet, replacing Soviet Cyrillic script, and recognizes nomadic civilization as part of the national identity (Vision, 2050)].

The second recommendation is to get genuine buy-in from all participants. This recommendation is obvious on the surface yet is often minimized or ignored entirely. This is not without consequence, as dedicated cooperation rather than passive participation is fundamental to group cohesion and productivity. Genuine buy-in does not come from direct orders that force people to participate. Scholars have emphasized the assessment of teams in both government and non-government sectors, laying the groundwork for the development of training programs and specialized support resources to promote effective cross-institutional cooperation.

The third recommendation centers around psychological research on status equality. Successful intergroup cooperation involves the recognition of team members' strengths, skillsets, and expertise. Acknowledging that “status equality” in its literal sense undermines the important rank structures in both government and non-government domains, we instead reframe the equal status condition to emphasize equal value of team members' unique contributions to the collaboration. Leaning on expertise diversity can lead to more successful collaboration (Tiwana, 2005).

Finally, recommendation four, Mongolian partners should be externally encouraged through institutional support, ideally leveraged from both government and non-government funding to commit to the foundations of resilience. In situations involving national security concerns, Mongolia's institutional bodies can serve as instigators of collaboration and as a source of support for the establishment of common goals, effective cooperation, and status equality.

Adaptation post-crisis: the psychology of change

After crises comes a period of learning and adaptation. Reflection and learning both require cognitive capabilities to evaluate a crisis and gain insight and behavioral capabilities to enact change based on “lessons learned.” In organizational psychology research, this process of learning post-crisis is described as an “ongoing process of reflection and action characterized by asking questions, seeking feedback, experimenting, reflecting on results, and discussing errors or unexpected outcomes of actions (Duchek, 2020).” Organizational-level learning also comes from observing others' successes and failures. Research suggests, for example, that airline and railroad accidents decline as accidents by other firms in the same industry increase (Baum and Dahlin, 2007). Mongolia, along with other fragile democracies, will learn from Ukraine's current experience resisting Russian occupiers.

However, lessons learned do not necessarily mean effective adaptation. Individuals and groups are often resistant to change for a variety of reasons, including the increased work that comes with change and the previously discussed psychological challenges associated with uncertainty. Successful adaptation requires determining the key drivers of resistance to change and then working to overcome them. In some cases, individuals' resistance to change stems from inaccurate beliefs due to misinformation,5 a barrier to change that requires education and awareness.

For example, Mongolia's written history is replete with ideological influences from the Soviet era that are politically influenced by orthodox communist ideology. Mongolian scholars recognize the importance of correcting these accounts to inform Mongolians, particularly Mongolian youth, about Mongolia's history, culture, and traditions free from the influences of its powerful neighbor nation. In their recent book “A History of Modern Mongolia,” Ookhnoi et al. (2018) explain:

During the Socialist period, our history could not be called “Mongolian history;” instead, we were to name it the history of the “Mongolian People's Republic,” the term given to us in 1924 due to Soviet presence here. Under this terminology, thousands of records of written history were distorted, due to the participation of those Soviet scientists who formulated the ideologies, in concealing underlying facts and realities. Mongolia has been passing along ideologically fueled viewpoints on social stratification, politics, history and traditions, thus providing inaccurate information to Mongolians.

New scholarship pioneered by Mongolians provides an important avenue for adapting the way the Mongolian people understand (and preserve) their history.

Conclusion

How can smaller nations protect their sovereignty? This article discusses a critical but underexamined aspect of resilience: psychological will and readiness on the individual level. We suggest motivational factors, viewed through the lens of significance quest theory, fused with anticipation, coping, and adaptation strategies found in traditional psychology, provide a useful, albeit incomplete, framework to better understand how conflict outcomes will be affected by national backed social-resilience programs that support the will to defend.

In any society, but especially for smaller nations like Mongolia, resilience building must incorporate both individual and societal-level psychological motivations and capabilities into existing civil preparedness frameworks. By applying psychological resilience concepts and considerations to Mongolia, a modern democracy shaped by a storied history of conquest, colonization, and invasion from neighboring nations, we hope that future research will advance this conceptual framework through systematic theory-building, hypothesis testing, and incorporating interdisciplinary perspectives on this complex topic.

James Scott's pivotal political science work on the “weapons of the weak” provides one such interdisciplinary lens. Through ethnographic research in rural Malaysia, Scott examines the subtle forms of defiance used by the oppressed against dominant power structures. He challenges the notion that resistance must be overt or organized to be significant, highlighting instead the effectiveness of seemingly trivial acts, such as foot-dragging, gossip, and avoidance. Scott's insights encourage a broader understanding of social change, emphasizing that power is not solely exercised through grand revolutions but can also be contested through persistent, low-profile acts of defiance. Whereas Scott's ethnography research was conducted amongst poverty-stricken rural peasants, making the theoretical foundations quite different from the Mongolia case, the potential parallels are intriguing and merit further examination.

Other future work should extend research on psychological resilience building to other democracies facing more direct threats of sovereignty loss—nations such as Taiwan, Baltic and Balkan states, and Georgia, among others. In the case of Mongolia, its collective memory of overcoming past threats from powerful nations provides a solid foundation for the psychological fortitude needed to protect itself from those attempting to use revisionist history to challenge Mongolia's political, cultural, and territorial sovereignty.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the patients/participants or patients/participants' legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

SH: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Author disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the views of the author alone. They do not reflect the official position of the Naval Postgraduate School, the U.S. Navy, the U.S. Marine Corps, the Department of Defense, or any other entity within the U.S. Government; and the author is not authorized to provide any official position of these entities. Portions of this paper were previously published in War on the Rocks.

Footnotes

1. ^The conceptual and practical implications for psychological resilience presented in this paper may translate to other nations as well, though making specific generalizations is beyond of the scope of this work.

2. ^World Values Survey. https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/wvs.jsp

3. ^Survey data were collected primarily in 2018-2020 due to the pandemic outbreak. According to WVS, the “vast majority of surveys were conducted using face-to-face interview (PAPI/CAPI) as the data collection mode.”

4. ^For brevity, we summarize a selection of findings relevant to basic societal values. These results provide a general picture of Mongolian values but are not intended to be exhaustive.

5. ^The term misinformation does not translate to the Mongolian language and in fact it can backfire when mistranslated, according to Dulamkhorloo Baatar, founder and editor-in-chief of the Mongolian Fact-Checking Center. For discussion, see Lkhagvasuren, 2022.

References

Adiya, A. (2023). How is Mongolia Addressing Concerns Over Foreign Meddling in Elections? Mongolia Weekly. Available at: https://www.mongoliaweekly.org/post/concerns-over-foreign-~meddling-rise-in-mongolia-s-elections (accessed November 2, 2024).

Allison, G. (2018). Destined for War: Can American and China Escape the Thucydides Trap? New York: Mariner Books.

Allport, G. W., Bruner, J. S., and Jandorf, E. M. (1941). Personality under social catastrophe: ninety life-histories of the Nazi revolution. Charact. Pers. 10, 1–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1941.tb01886.x

Amonson, K., and Egli, D. (2023). The ambitious dragon: Beijing's calculus for invading Taiwan by 2030. J. Indo-Pacific Affairs 6:37.

Andregg, M. (2021). “Why Asia should lead a global push to eliminate nuclear weapons –the role for Mongolia,” in Mongolia and Northeast Asian Security, 162–177. doi: 10.4324/9781003148630-8

Asian Development Bank (2020). Strengthening Integrated Early Warning System in Mongolia: Technical Assistance Report. Available at: https://www.adb.org/projects/documents/mon-53039-001-tar (accessed November 2, 2024).

Barnes-Holmes, D., Cochrane, A., Barnes-Holmes, Y., Stewart, I., and McHugh, L. (2004). Psychological acceptance: experimental analyses and theoretical interpretations. Int. J. Psychol. Psychol. Ther. 4, 517–530.

Batsaikhan, O., Zorigtu, L., Chimeddorji, E., Sovdo, B., and Amarsanaa, S. (2018). The History of Modern Mongolia. Mongolian Scientific and Research Institute for National Freedom.

Baum, J. A. C., and Dahlin, K. B. (2007). Aspiration performance and railroads' patterns of learning from train wrecks and crashes. Organiz. Sci. 18, 368–385. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1060.0239

Berkes, F. (2007). Understanding uncertainty and reducing vulnerability: lessons from resilience thinking. Nat. Hazards 41, 283–295. doi: 10.1007/s11069-006-9036-7

BTI (2022). Mongolia Country Report 2022. Available at: https://bti-project.org/en/reports/country-report/MNG (accessed November 2, 2024).

Cabinet Decision (2014). Fundamental Plan for National Resilience. Available at: https://www.cas.go.jp/jp/seisaku/kokudo_kyoujinka/en/fundamental_plan.html#chapter1 (accessed November 2, 2024).

Caldwell, M. L. (2022). Hacking, Disruptive Democracy, and the War in Ukraine. Hot Spots, Fieldsights. Available at: https://culanth.org/fieldsights/hacking-disruptive-democracy-and-the-war-in-ukraine (accessed November 2, 2024).

Chávez, K., and Swed, O. (2023). Emulating underdogs: tactical drones in the Russia-Ukraine war. Contemp. Secur. Policy 44, 592–605. doi: 10.1080/13523260.2023.2257964

Chultemsuren, T., and Aldar, D. (2022). “History and trends of direct democracy in Mongolia,” in Ups and Downs of Direct Democracy Trends in Asia: Country Cases, 92.

Deci, E. L. (1971). Effects of externally mediated rewards on intrinsic motivation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 18, 105–115. doi: 10.1037/h0030644

Dickinson, P. (2021). The 2008 Russo-Georgian War: Putin's green light. Atlantic Council, UkraineAlert. Available at: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/the-2008-russo-~georgian-war-putins-green-light/ (accessed November 2, 2024).

Dougherty, E., and Pfaltzgraff, R. (1997). Contending Theories of International Relations: A Comprehensive Survey 4th Edition. New York: Longman.

Duchek, S. (2020). Organizational resilience: a capability-based conceptualization. Bus. Res. 13, 215–246. doi: 10.1007/s40685-019-0085-7

Edwards, T. (2024). Putin Visits Mongolia in Defiance of ICC Arrest Warrant. Time Magazine. Available at: https://time.com/7016879/putin-mongolia-visit-icc-arrest-warrant/ (accessed November 2, 2024).

Ekstrom, M. (2023). Language policy in inner mongolia and its implications for Chinese and international human rights. China Res. Center 22:22.

Fern?ndez-Gimenez, M. E., Batjav, B., and Baival, B. (2012). Lessons from the Dzud. Adaptation and Resilience in Mongolian Pastoral Social-Ecological Systems. Available at: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/986161468053662281/pdf/718440WP0P12770201208-01-120revised.pdf doi: 10.1596/26783 (accessed November 2, 2024).

Festinger, L. (1957). A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. doi: 10.1515/9781503620766

Fiala, O. (2019). Resistance Operating Concept. 1st ed. Stockholm, Sweden: Swedish Defence University.

Fletcher, D., and Sarkar, M. (2013). Psychological resilience. Eur. Psychol. 18:124. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000124

Frederick, B., and Shatz, H. J. (2022). Countering Chinese Coercion: Multilateral Response to PRC Economic Pressure Campaigns. RAND Corporation. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep46204 (accessed November 2, 2024).

Gaertner, S. L., Dovidio, J. F., Anastasio, P. A., Bachman, B. A., Mary, C., and Rust. (2011). The common in group identity model: recategorization and the reduction of intergroup bias. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 4, 1–26. doi: 10.1080/14792779343000004

Global Nonviolent Action Database (n.d.) Available at: https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/mongolians-win-multi-party-democracy-1989-1990 (accessed November 2, 2024).

Gutiérrez-Dávila, M., Rojas, F. J., Antonio, R., and Navarro, E. (2013). Effect of uncertainty on the reaction response in fencing. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 84, 16–23. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2013.762286

Haerpfer, C., Inglehart, R., Moreno, A., Welzel, C., Kizilova, K., Diez-Medrano, J., et al. (2022). World Values Survey: Round Seven - Country-Pooled Datafile Version 4.0. Madrid, Spain and Vienna, Austria: JD Systems Institute and WVSA Secretariat.

Hahn, A. H. (2017). Mongolian dzud: threats to and protection of mongolia's herding communities. Educ. About Asia 22, 42–46.

Hennig, A. (2023). Repression of Human Rights in China under Xi Jinping. Available at: https://dialogopolitico.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/cap-4-repression-of-human-~rights-in-china-under-xi-jinping-DP-2023.pdf (accessed November 2, 2024).

Herbert, J. D., Forman, E. M., and England, E. L. (2009). “Psychological acceptance,” in Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Applying Empirically Supported Techniques to Your Practice, 4–16.

Houck, S. C. (2022). Psychological Capabilities for Resilience. War on the Rocks. Available at: https://warontherocks.com/2022/12/psychological-capabilities-for-resilience/ (accessed November 2, 2024).

Hull, C. L. (1943). Principles of Behavior: An Introduction to Behavior Theory. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

IRI Mongolia Poll (2021). IRI Mongolia Poll shows strong support for Democratic governance, concerns for country's direction and ability to make change. International Republican Institute (IRI). Available at: https://www.iri.org/resources/iri-mongolia-poll-shows-strong-support-for-democratic-governance-concerns-for-countrys-direction-and-ability-to-make-change/ (accessed November 2, 2024).

Jang, J., and Kim, K. (2023). Mongolia becoming a permanent neutral nation? Focusing on the debate and challenges of the permanent neutral nation policy. Pac. Rev. 37, 1–29. doi: 10.1080/09512748.2023.2184853

Jargalsaikhan, M. (2017). Mongolia's Domestic Politics Complicate Foreign Policy in a Precarious International Setting. Asia Pacific Bulletin. Available at: https://www.eastwestcenter.org/publications/mongolia%E2%80%99s-domestic-politics-~complicate-foreign-policy-in-precarious-international (accessed November 2, 2024).

Jargalsaikhan, M. (2023). The resilience capacity of the state. Mongolian J. Strat. Stud. 89, 4–103.

Jones, S., McCabe, R., and Palmer, A. (2023). Ukrainian Innovation in a War of Attrition. Center for Strategic and International Studies. Available at: https://www.csis.org/analysis/ukrainian-~innovation-war-attrition (accessed November 2, 2024).

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2005). Coming to Our Senses: Healing Ourselves and the World through Mindfulness. New York: Hyperion.

Kimhi, S., Kaim, A., Bankauskaite, D., Baran, M., Baran, T., Eshel, Y., et al. (2024). A full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022: resilience and coping within and beyond Ukraine. Appl. Psychol. 16, 1005–1023. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12466

Kok-Kheng, E. (2022). “Today's Ukraine, tomorrow's Taiwan: Russia's invasion of Ukraine, China's revanchism, and the Chinese communist party-state's quest to remake the world in its own image,” in Contemporary Chinese Political Economy and Strategic Relations: An International Journal, 8.

Kruglanski, A., Bélanger, J., and Gunaratna, R. (2019). The Three Pillars of Radicalization: Needs, Narratives, and Networks. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780190851125.001.0001

Kulyk, V. (2023). National identity in time of war: Ukraine after the russian aggressions of 2014 and 2022. Probl. Post-Commun. 71, 296–308. doi: 10.1080/10758216.2023.2224571

Kwiet, K. (2019). Learn the History – Why did Jews not leave Germany when the Nazis came to power? Sydeny Jewish Museum Blog. Available at: https://sydneyjewishmuseum.com.au/news/learn-the-history-why-did-jews-not-leave-germany-when-the-nazis-came-to-power/ (accessed November 2, 2024).

Lee, J. (2022). Chinese Information and Influence Warfare in Asia and the Pacific. Hudson Institute, Inc. Available at: https://www.hudson.org/national-security-defense/chinese-information-and-influence-warfare-in-asia-and-the-pacific

Lkhaajav, B. (2021). Mongolia-Russia Diplomatic Relations at 100. The Diplomat. Available at: https://thediplomat.com/2021/12/mongolia-russia-ties-at-100/ (accessed November 2, 2024).

Lkhaajav, B. (2022). Youth Protest Stretches Into Day 2 in Mongolia. The Diplomat. Available at: https://thediplomat.com/2022/04/youth-protest-stretches-into-day-2-in-~mongolia/ (accessed November 2, 2024).

Lkhagvasuren, B. (2022). Comprehensive Defense: Psychological Resilience in Mongolia. Available at: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/trecms/pdf/AD1173435.pdf (accessed November 2, 2024).

Magness, S. (2015a). How Uncertainty in Workouts Can Help Your Racing. Runners World. Available at: https://www.runnersworld.com/advanced/a20845390/how-uncertainty-in-workouts-can-~help-your-racing/ (accessed November 2, 2024).

Magness, S. (2015b). How and why to use uncertainty during workouts. Science of Running. Available at: https://www.scienceofrunning.com/2015/02/the-benefits-of-using-~uncertainty.html?v=47e5dceea252 (accessed November 2, 2024).

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychol. Rev. 50, 370–396. doi: 10.1037/h0054346

McDougall, W. (1932). The Energies of Men (Psychology Revivals): A Study of the Fundamentals of Dynamic Psychology (1st ed.). London: Routledge.

Mercy Corps (2017). Mongolia Strategic Resilience Assessment. Available at: https://www.mercycorps.org/sites/default/files/2019-12/Mercy_Corps_Strategic_Resilience_Assessment_Mongolia_April_2017.pdf (accessed November 2, 2024).

Miller, B., and Tabachnik, A. (2023). “States, nations and great-power expansion in their neighborhood: explaining the Russian War against Ukraine,” in Turmoil and Order in Regional International Politics. Evidence-Based Approaches to Peace and Conflict Studies, eds. W.R. Thompson, T. J. Volgy (Singapore: Springer). doi: 10.1007/978-981-99-0557-7_10

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Mongolia (n.d.). Third Neighbors. Available at: https://mfa.gov.mn/en/diplomatic/56715/ (accessed November 2, 2024).

Montsame (2024). President of Mongolia: It Is Time to Realize the “National Resilience Building Strategy.” Available at: https://www.montsame.mn/en/read/335687

Moran, D. J. (2011). ACT for leadership: Using acceptance and commitment training to develop crisis-resilient change managers. Int. J. Behav. Consult. Ther. 7:66. doi: 10.1037/h0100928

Muradov, I. (2022). The Russian hybrid warfare: the cases of Ukraine and Georgia. Defence Stud. 22, 168–191. doi: 10.1080/14702436.2022.2030714

Nakamura, Y. M., and Orth, U. (2005). Acceptance as a coping reaction: adaptive or not? Swiss J. Psychol. 64, 281–292. doi: 10.1024/1421-0185.64.4.281

Nyamtseren, T. (2024). Mongolian Peacekeeping as a Foreign Policy Tool. Institute for Strategic Studies Mongolia.

O'Connor, P., Becker, K., and Fewster, K. (2018). “Tolerance of ambiguity at work predicts leadership, job performance, and creativity,” in Creating Uncertainty Conference, 1.

Ookhnoi, B., Zorigtu, L., Chimeddorji, E., Sovdo, B., and Sukhbaata, A. (2018). The History of Modern Mongolia: 1911-2017. Mongolian Scientific and Research Institute for National Freedom. Available at: https://www.mongolian-art.de/THE_HISTORY_OF_MODERN_MONGOLIA_1911_2017.html

Panda, J., and Pankaj, E. (2023). The Dalai Lama's Succession: Strategic Realities of the Tibet Question. Institute for Security and Development Policy. Available at: https://orcasia.org/allfiles/ORCA-ISDP-Special-Issue_2023.pdf (accessed November 2, 2024).

Peng, Q., Liu, C., Scelles, N., and Inoue, Y. (2023). Continuing or withdrawing from endurance sport events under environmental uncertainty: athletes' decision-making. Sport Manag. Rev. 26, 698–719. doi: 10.1080/14413523.2023.2190431

Pettigrew, T. F. (1998). Intergroup contact theory. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 49, 65–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.65

Pettigrew, T. F., and Tropp, L. R. (2006). A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 90, 751–783. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751

Pettigrew, T. F., and Tropp, L. R. (2008). How does intergroup contact reduce prejudice? Meta- analytic tests of three mediators. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 38, 922–934. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.504

Pieper, M. (2020). The new silk road heads north: implications of the China-Mongolia-Russia economic corridor for Mongolian agency within Eurasian power shifts. Eur. Geogr. Econ. 62, 745–768. doi: 10.1080/15387216.2020.1836985

Polyakova, A., and Meserole, C. (2019). “Exporting digital authoritarianism: the Russian and Chinese models,” in Policy Brief, Democracy and Disorder Series 1–22.

Predko, V., Schabus, M., and Danyliuk, I. (2023). Psychological characteristics of the relationship between mental health and hardiness of Ukrainians during the war. Front. Psychol. 14:1282326. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1282326

Pretus, C., Hamid, N., Sheikh, H., Ginges, J., Tobeña, A., Davis, R., et al. (2018). Neural and behavioral correlates of sacred values and vulnerability to violent extremism. Front. Psychol. 9:2462. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02462

Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty (2019). Russia to sign landmark permanent treaty with Mongolia. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Available at: https://www.rferl.org/a/putin-to-sign-landmark-permanent-treaty-with-mongolia/30141895.html (accessed November 2, 2024).

Robinson, B. (2022). What Brain Science Reveals About Uncertainty and 6 Strategies to Cope at Work. Forbes. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/bryanrobinson/2022/08/24/what-brain-science-reveals-about-uncertainty-and-6-strategies-to-cope-at-work/?sh=2124249544b0 (accessed November 2, 2024).

Roepke, W. D., and Thankey, H. (2019). Resilience: The First Line of Defence. The Three Swords Magazine. Available at: https://www.jwc.nato.int/images/stories/_news_items_/2019/three-swords/ResilienceTotalDef.pdf

Roy, M., and Kumar, A. (2023). Mongolia to decide on gas pipeline route after Russia-China cost agreement. Reuters. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/mongolia-decide-gas-pipeline-route-after-russia-china-cost-agreement-2023-03-15/

Sageman, M. (2004). Understanding terror networks. Int. J. Emerg. Ment. Health 7, 5–8. doi: 10.9783/9780812206791

Sargent, R. H., Houck, S. C. H., and Conway, L. G. C. I. I. I. (2022). How to Stop Political Division from Eroding Military-Academic Relations. Defense One. Available at: https://www.defenseone.com/ideas/2021/07/how-stop-political-division-eroding-military-academic-relations/183588/ (accessed November 2, 2024).

Schaller, M., Kenrick, D. T., Neel, R., and Neuberg, S. L. (2017). Evolution and human motivation: a fundamental motives framework. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 11:e12319. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12319

Shah (2022). China's annexation of Tibet with the view of recent developments. The Kootneeti. Available at: https://thekootneeti.in/2022/06/30/chinas-annexation-of-tibet-with-the-view-of-recent-~developments/ (accessed November 2, 2024).

Sherif, M., Harvey, O. J., White, B. J., Hood, W., and Sherif, C. W. (1961). Intergroup Conflict and Cooperation: The Robbers Cave Experiment. Norman, OK: The University Book Exchange, 155–184.

Snegovaya, M., and Lanoszka, A. (2022). Fighting Yesterday's War: Elite Continuity and Revanchism. SSRN. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4304528 or doi: 10.2139/ssrn.4304528 (accessed November 2, 2024).

Sodi, T., Han, B., and Singh, P. (2021). Special issue on psychology of uncertainty and vulnerabilities: COVID-19 pandemic related crisis. Psychol. Stud. 66, 235–238. doi: 10.1007/s12646-021-00623-w

Speckhard, A., and Paz, R. (2012). Talking to Terrorists: Understanding the Psycho-Social Motivations of Militant Jihadi Terrorists, Mass Hostage Takers, Suicide Bombers and Martyrs. New York: Advances Press.

Stanway, D. (2022). Mongolia's East-West balancing act buffeted by Russian invasion of Ukraine. Reuters. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/mongolias-east-west-balancing-act-buffeted-by-russian-invasion-ukraine-2022-03-03/(accessed November 2, 2024).

Strout, T. D., Hillen, M., Gutheil, C., Anderson, E., Hutchinson, R., Ward, H., et al. (2018). Tolerance of uncertainty: a systematic review of health and healthcare-related outcomes. Patient Educ. Couns. 101, 1518–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2018.03.030

Tiwana, A. (2005). Expertise integration and creativity in information systems development. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 22, 13–43. doi: 10.1080/07421222.2003.11045836

Tsedevdamba, O. (2016). The secret driving force behind mongolia's successful democracy. Prism 1, 140–152.

Tsolmon, O. (2024). Mongolia's Security and Foreign Policy in The Era Of Great Power Competition. Available at: https://core.ac.uk/reader/610636790 (accessed November 2, 2024).

Turner, R. N., Crisp, R. J., and Lambert, E. (2007). Imagining intergroup contact can improve intergroup attitudes. Group Proc. Intergroup Relat. 10, 427–441. doi: 10.1177/1368430207081533

Tzu-Chieh, H., and Tzu-Wei, H. (2022). How China's cognitive warfare works: a frontline perspective of Taiwan's anti-disinformation wars. J. Glob. Secur. Stud. 7:ogac016. doi: 10.1093/jogss/ogac016

U.S. Embassy in Mongolia (n.d.). Gobi Wolf . Available at: https://mn.usembassy.gov/category/gobi-wolf/ (accessed November 2, 2024).

Vision 2050. Available at: https://vision2050.gov.mn/eng/ (accessed November 2, 2024).

Weber, V. (2019). The worldwide web of Chinese and Russian information controls. Center for technology and global affairs, University of Oxford.

White, R. P., and Shullman, S. L. (2010). Acceptance of uncertainty as an indicator of effective leadership. Consult. Psychol. J. 62:94. doi: 10.1037/a0019991

Wong, A., Easley, L. E., and Tang, H. W. (2023). Mobilizing patriotic consumers: China's new strategy of economic coercion. J. Strat. Stud. 46, 1287–1324. doi: 10.1080/01402390.2023.2205262

Yahil, L. (1991). The Holocaust: The Fate of European Jewry, 1932-1945. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Yerkes, R. M., and Dodson, J. D. (1908). The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit-formation. J. Compar. Neurol. Psychol. 18, 459–482. doi: 10.1002/cne.920180503

Zachara-Szymańska, M. (2023). The return of the hero-leader? Volodymyr Zelensky's international image and the global response to Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Leadership 19, 196–209. doi: 10.1177/17427150231159824

Keywords: psychological resilience, Mongolia, sovereignty, significance quest theory, democracy, authoritarianism

Citation: Houck SC (2024) Building psychological resilience to defend sovereignty: theoretical insights for Mongolia. Front. Soc. Psychol. 2:1409730. doi: 10.3389/frsps.2024.1409730

Received: 30 March 2024; Accepted: 21 October 2024;

Published: 14 November 2024.

Edited by:

Dmitry Grigoryev, National Research University Higher School of Economics, RussiaReviewed by:

Gustavo Martineli Massola, University of São Paulo, BrazilMarissa Smith, Independent Scholar, Mountain View, United States

Copyright © 2024 Houck. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shannon C. Houck, c2hhbm5vbi5ob3Vja0BucHMuZWR1

Shannon C. Houck

Shannon C. Houck