95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Soc. Psychol. , 30 August 2024

Sec. Attitudes, Social Justice and Political Psychology

Volume 2 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frsps.2024.1406688

The role of religiosity in radicalization is a topic of intense debate. To avoid essentializing religion, it is crucial to include a variety of factors that can explain radicalization beyond religiosity. The present study aligns with this approach by building upon the three Ps of radicalization (push, pull, personal factors). It examines the relative role of various forms of religiosity (pull factors) in radicalization within the context of social structure, perceived deprivation (both push factors), and demographic variables (personal factors). We analyzed previously collected data comprising a sample of 1,048 Muslims with Turkish migration background in Germany. Acceptance of active and reactive violence as indicators of radicalization with demography, social-structure position, perceived deprivation, and different forms of religiosity (individual, collective, orthodox, fundamentalist religiosity) were used as predictors. Individual religiosity was a protective factor against reactive violence when controlling for fundamentalism. Fundamentalism emerged as the strongest predictor of the acceptance of reactive violence. Both fundamentalism and orthodox religiosity were positive predictors of active violence. However, these latter effects should be interpreted with caution due to the naturally low acceptance of active violence. Finally, the deprivation-radicalization association was stronger for participants scoring higher on fundamentalism, while medium to high orthodox religiosity was the key factor connecting deprivation to radicalization. Implications are delineated regarding practical strategies, specifically formulated for addressing feelings of deprivation within minority contexts.

The role of religion in radicalization is the subject of ongoing and highly controversial debate, not only in public discourse and politics but also in the social sciences (de Graaf and van den Bos, 2021). This debate focuses on the factors explaining radicalization, which can be classified into push, pull, and personal factors, also known as the 3Ps of radicalization (Vergani et al., 2020). Some scholars deny that religiosity plays any role as a pull factor of radicalization, whereby pull factors are understood as “group-level sociocognitive explanations” (Vergani et al., 2020, p. 857). Instead, radicalization is believed to be caused by push factors that target social structural explanations (especially low education and unemployment; e.g., Piazza, 2011; Della Porta, 2013) and, perceived deprivation (especially discrimination and marginalization; e.g., Schiffauer, 1999; Piazza, 2012), or personal factors that refer to biographical explanations (especially demographic factors; Borum, 2015; Koomen and van der Pligt, 2015).

Others, such as Six (2005), Pratt (2010), and Koopmans et al. (2021) insist on taking statements by extremists seriously, emphasizing their justification of actions through their religion, and demand more research on this question (Horgan, 2014). Religiosity certainly is of interest for radicalization research because it relates to various aspects of ideology: its psychological aspects, such as the ideological frames through which the world is understood (Snow and Byrd, 2007; Borum, 2015); its underlying religious-moral values (Ginges et al., 2011); its transcendent ideological aspects, such as the promise of rewards in the afterlife (Kiper and Sosis, 2021); and, more simply, associated group cohesive functions (Ginges et al., 2009). Together, these aspects may indeed render religion, or certain forms of religiosity, an important pull factor of radicalization.

Although radicalization is not restricted to religious groups (e.g., left- and right-wing radicalization), it can be found among various religious groups, such as Christians and Jews (e.g., Ginges et al., 2009; Koopmans et al., 2021). However, the prevailing academic discussion centers around Muslim radicalization (Williamson and Demmrich, 2024) especially in the context of migration (e.g., Beller and Kröger, 2018; Jakubowska et al., 2021). Most probably, the phenomenon of radicalization influences a small minority among them (e.g., Goli and Rezaei, 2011). Nevertheless, Islam and Muslims are often perceived as an exceptional case in terms of radicalization in academia (Wright, 2016) and Islam is often discriminated against as fanatic, radical, and prone to violence in the wider public (Pollack, 2014; Yendell and Pickel, 2019).

While our paper reflects on the relationship between different forms of religiosity and acceptance of violence, it utilizes a sample of Muslims (with a Turkish migration background) in a minority context (Germany),1 leveraging the heightened focus on Islam within such contexts, thereby facilitating the availability of such datasets. Therefore, the present study undertakes a secondary analysis of a previously collected dataset of Muslims with a Turkish migration background in Germany. A general objective of this paper is to build on effects observed in prior studies involving other religions and/or contexts (e.g., Ginges et al., 2009; Koopmans et al., 2021), but also to discuss results that may deviate from previous findings, offering insights specific to the sample under scrutiny.

Specifically, our study aims to analyze the associations between different forms of religiosity and radicalization. Thus, the study uses religiosity as a pull factor of radicalization and researches its relative prediction against the background of both push and personal factors (Vergani et al., 2020). Building upon previous studies, different forms of religiosity are examined and existing knowledge is expanded by placing greater emphasis on reactive forms of violence in addition to the previously researched active forms. Finally, it is examined whether certain forms of religiosity can fuel the alleged deprivation-radicalization-nexus.

Radicalization is often broadly defined as an “increasing questioning of the legitimacy of a normative order and/or an increasing willingness to combat the institutional structure of that order” (Gaspar et al., 2019, p. 20, translated by the authors). While radicalization can include violence, it does not necessarily have to (see also Kruglanski, 2018). Thus, the term describes a gradual development toward violent, extremist beliefs, potentially leading to actions (Pickel and Pickel, 2023). However, this process does not necessarily end with the application of extremist violence; it can also be interrupted or regress. Different degrees of radicalization are characterized variably, such as non-violent radicalization or radicalization involving various forms of violence (Gaspar et al., 2019; Moskalenko and McCauley, 2020). These gradual models enable social scientific research to identify radicalization not only in connection with extremist violence but also at the attitudinal level, such as the acceptance of different forms of violence. This acceptance can, but does not have to, provide a basis for further radicalization (Pickel and Pickel, 2023).

In most empirical studies, especially those using large samples, radicalization is measured by one of these outcomes of the radicalization process (see Ozer and Bertelsen, 2018), i.e., the acceptance of violence (e.g., Brettfeld and Wetzels, 2007; Zhirkov et al., 2012; Jakubowska et al., 2021; Koopmans et al., 2021), which is expressed in religious terms in the vast majority of the studies on radicalization (e.g., Beller and Kröger, 2018; Hadjar et al., 2019; Jakubowska et al., 2021).

As implied above, the scholarly discussion about whether, and if so, how strongly religiosity predicts radicalization has resulted in a division into two scholarly factions: There are those who argue from a more theoretical, often normative perspective, or who examine single case studies. These scholars usually deny that religiosity plays any role in radicalization (e.g., Amirpur, 2015; Kiefer et al., 2017; Juergensmeyer, 2019). In contrast, other scholars who analyze the connecting factors between religion and radicalization, find that claims of religious exclusivity, universalism, or religious fundamentalism are connected to radicalization (e.g., Khosrokhavar, 2016; Lohlker, 2016; Wright, 2016). A central critical point is that those researchers would equate religion with radicalization. Despite these accusations, most of these scholars find convincing criteria that differentiate between non-radical vs. radical religion (e.g., Pratt, 2010; Khorchide, 2020).

Empirical studies offer a more differentiated perspective on the relationship between religiosity and radicalization. These investigations emphasize the significance of distinguishing between various forms of religiosity. In addition to the cross-religious studies (i.e., comparing participants from different religions) that found a significant relation between affiliation with Islam and radicalization (Canetti et al., 2010; Koopmans et al., 2021), especially among European Muslims with a migration background (Zhirkov et al., 2012; Jakubowska et al., 2021), previous studies found:

• Individual religiosity (including the importance of religion or God in life) is not (Esposito and Mogahed, 2007; Frindte et al., 2011; Acevedo and Chaudhary, 2015; Hadjar et al., 2019; Beller and Kröger, 2021) or is even negatively linked to religiously connoted violence (Zhirkov et al., 2012; Beller and Kröger, 2018) but is positively related to political (rather than religiously termed) violence (Canetti et al., 2010; Beller, 2017 when controlled for deprivation in a cross-religious study). Similar to individual religiosity, prayer frequency seems primarily uncorrelated to radicalization (Ginges et al., 2009; Acevedo and Chaudhary, 2015; Beller, 2017; Beller and Kröger, 2018, 2021 in a cross-religious study).

• Other studies have found positive relations between radicalization and religious service attendance (Ginges et al., 2009; Beller and Kröger, 2018 in cross-religious studies) although two studies, which did not differentiate between (individual) prayer and religious service attendance, found a negative relation with radicalization (Muluk et al., 2013; Barton et al., 2021), and another two studies found no relation to radicalization (Beller, 2017; Beller and Kröger, 2021). A positive relation between such collective religious practices and radicalization is often explained using the coalition commitment hypothesis, which states that collective religious practices increase ingroup commitment and outgroup hostility and, thus, heighten the probability of accepting violence across cultures and religions (Ginges et al., 2009).

• Orthodox religiosity, i.e. central religious beliefs and behavior that are defined as binding objects of faith, is usually positively related to radicalization (Brettfeld and Wetzels, 2007; Goli and Rezaei, 2011; Koopmans et al., 2021 in a cross-religious study) but the specific orthodox belief that the Quran is God's word seems to protect against radicalization (Acevedo and Chaudhary, 2015).

• Another predictor of radicalization is religious fundamentalism, even though findings are still somewhat mixed. Religious fundamentalism is usually considered as a non-violent phenomenon (Williamson, 2020; Williamson and Demmrich, 2024) and is characterized by exclusive beliefs, which are seen as superior to all other worldviews, as universally valid for all things in the world, and which must be realized by restoring to a past “Golden Age” (Pollack et al., 2023). One study identified a negative relation between religious fundamentalism and radicalization (Beller and Kröger, 2018), and three studies detected non-significant relations (Ahmad, 2014; Acevedo and Chaudhary, 2015; Beller and Kröger, 2021). However, most studies have found a positive link between religious fundamentalism and radicalization (Brettfeld and Wetzels, 2007; Frindte et al., 2016; Beller, 2017; Heinke, 2017; Alkhadher and Scull, 2019; Jakubowska et al., 2021 in a cross-religious study; Koopmans et al., 2021 in a cross-religious study; Mashuri and Zaduqisti, 2019 via perceived intergroup conflict and anti-Western stereotypes; Muluk et al., 2013; Putra and Sukabdi, 2014; Yustisia et al., 2020).

Finally, the small number of studies focused on other, less widespread indicators of religiosity have yielded mixed results. For example, various studies have demonstrated that religious education and socialization have a negative link (Kiefer et al., 2017), no link (Beller and Kröger, 2018; Barton et al., 2021), or a positive link to radicalization (Aslan et al., 2017). Further, other studies have found that using Holy Scriptures as a justification for violence has no link to radicalization (Esposito and Mogahed, 2007), yet other studies have identified a positive link between the two (Muluk et al., 2013; Aslan et al., 2017). Thus, while religious conspiracy theories are positively associated with radicalization (Beller, 2017), the nature of the relationship to one's support for political Islam remains controversial (positive link: Fair and Shepherd, 2006; no link: Acevedo and Chaudhary, 2015).

Regardless of the idea that certain aspects of religiosity might play a role in radicalization, it is repeatedly emphasized that we should not only consider such pull factors of radicalization, but we should also simultaneously include personal factors and push factors (Ginges et al., 2011; Vergani et al., 2020). Balanced views of this kind have not been consistently applied in the empirical studies mentioned thus far: only some studies (Fair and Shepherd, 2006; Brettfeld and Wetzels, 2007; Zhirkov et al., 2012; Beller and Kröger, 2018, 2021; Jakubowska et al., 2021) examined religiosity's relative prediction of radicalization using multivariate analyses which also took into account the push factors of a low social-structural position and high perceived deprivation, as well as personal factors of demography. A balanced view of this kind was especially lacking in those studies that did not find any particular relationship between religiosity and radicalization: Esposito and Mogahed (2007) reported only univariate analyses, the studies by Ahmad (2014) and Kiefer et al. (2017) are qualitative in nature, and Acevedo and Chaudhary (2015) and Hadjar et al. (2019) omitted perceived deprivation. As an exception, only Beller and Kröger (2018) examined religiosity, social-structural indicators, perceived deprivation, and demography simultaneously and they did not identify any religiosity variables as significant factors of radicalization. It must be noted, however, that this study relied on the same data from Muslims in the USA as Acevedo and Chaudhary (2015) used. This is important as this group has a higher than average level of education and is hence socioeconomically advantaged. Thus, this sample is hardly comparable to the Muslim communities living outside the USA, including in Europe (Alba and Foner, 2015).

While most studies differentiate between various indicators of religiosity, they do not do the same for indicators of radicalization. Many of these investigations examine active forms of violence, i.e., attacking others in order to achieve political and/or religious aims, usually in the form of the acceptance of violence (see also van den Bos, 2018; Vergani et al., 2020). Additionally, only one survey study considered a reactive form of violence as a separate indicator of radicalization2 (Frindte et al., 2011, 2016; Hadjar et al., 2019 rely on the same data), namely, violently defending the religious ingroup when attacked from outside. Especially given the empirical evidence that perceived deprivation and discrimination – which could be perceived as attacks from outside – seem to be push factors of radicalization (e.g., Schiffauer, 1999; Piazza, 2012), the present study investigates the acceptance of both forms of violence, that is active and reactive violence.

Research exploring the question of the role of religiosity in radicalization is often depicted as an antipode to the so-called reactivity hypothesis. The reactivity hypothesis posits that deprivation, rather than cultural factors like certain forms of religiosity, is the primary driver of radicalization. Specifically, it suggests that individuals who are or who perceive themselves as deprived are more likely to become entrenched in a closed, radical worldview or join a demarcated group that acts as a buffer against the negative effects of discrimination, exclusion, and marginalization, ultimately bolstering their self-esteem (e.g., Roy, 2004; Kruglanski, 2018). However, while this hypothesis may seem initially plausible, it has produced controversial empirical findings (e.g., Brettfeld and Wetzels, 2007; Fleischmann et al., 2011). Its primary challenge, moreover, stems from its lack of specificity (Pisoiu, 2012; Aslan et al., 2017): Many segments of society experience and/or perceive deprivation but do not engage in radicalization. Even Muslims, who face significant levels of anti-Muslim discrimination worldwide (United Nations, 2023), including in Europe and Germany (e.g., Yendell and Pickel, 2019), do not undergo mass radicalization.

As a result, some scholars attempt to present a more nuanced view of the reactivity hypothesis. First, it appears that “hard indicators,” such as the social-structural position (e.g., unemployment, low education, low socioeconomic status), are not the crucial factors in radicalization. Instead, it is theoretically argued that the perception of deprivation (e.g., feelings of unfair treatment or relative deprivation), which may or may not align with an individual's position in social structure (e.g., feeling deprived despite having a good job and a high income; see van den Bos, 2018), plays a significant role in radicalization (Beller and Kröger, 2021).

Second, various moderating variables can either amplify or diminish the connection between perceived deprivation and radicalization (Vergani et al., 2020). These variables include factors like uncertainty stemming from threats, inadequate self-control (van den Bos, 2018), or the perception of a strong sense of unity within the ingroup (entitativity; Demmrich and Senel, forthcoming). Similarly, various forms of religiosity may play a moderating role in this connection. For instance, extreme religious beliefs, such as fundamentalism (van den Bos, 2018), could provide a framework for making sense of perceived deprivation, potentially accelerating the radicalization process. Conversely, more liberal religious beliefs might serve as a buffer against perceived deprivation, mitigating its relation with radicalization by promoting more controlled responses (van den Bos, 2023). Although often identified as an area requiring further research (e.g., Beller and Kröger, 2021), none of the previously mentioned empirical studies have examined this moderation thus far. Additionally, it remains unclear how other forms of religiosity, such as orthodoxy, interact in this relationship. If religious fundamentalism is closely associated with orthodoxy (Pollack et al., 2023; Williamson and Demmrich, 2024), it could potentially strengthen the presumed link between perceived deprivation and radicalization, too. Finally, the investigation of the role of religiosity in the deprivation-radicalization-nexus could also bridge the gap between these two hypotheses often depicted as antipodes.

Using a previously collected dataset comprising a sample of individuals with a Turkish migration background in Germany who identify as Muslims, our study aims to examine the relationships between different forms of religiosity (individual, collective, orthodox, and fundamentalist religiosity) and the acceptance of two forms of violence (reactive and active). Consistent with the majority of previous research findings as summarized above, it is hypothesized that individual religiosity is not related to the acceptance of violence, while collective, orthodox, and fundamentalist religiosity are positively related to the acceptance of both forms of violence (Hypothesis 1).

Furthermore, it is expected that these relationships will remain stable when simultaneously considering personal factors (demography) and push factors (low social-structural position, high perceived deprivation) (Hypothesis 2). Finally, it is anticipated that religiosity moderates the relationship between the often-hypothesized deprivation-radicalization-nexus. Specifically, it is hypothesized that orthodox religiosity and religious fundamentalism can amplify the positive relationship between deprivation and radicalization (Hypothesis 3).3

The data used for this study was drawn from the survey “Integration and Religion from the Perspective of Migrants of Turkish Origin in Germany” undertaken by the Cluster of Excellence “Religion and Politics” at the University of Münster (Pollack et al., 2016). Between 2015 and 2016, bilingual interviewers carried out a computer-assisted telephone survey of people with a Turkish migration background in Germany. The sample was drawn onomastically from German telephone books and initial screening questions ensured that the interviewees or their parents were originally from Turkey. Structural differences between the sample and population were minimized by factorial weighting based on the 2014 microcensus of the population with a Turkish migration background in Germany – which took age, gender, education, occupational status, and citizenship into account.

One thousand two hundred and one people with a turkish migration background were interviewed. Among them, 1048 consider themselves muslims or alevis with a muslim identity (50.1 % are men, MAge = 39.39; SDAge = 15.79; 49.4 % belonging to the first and 50.6 % to the second generation of migrants). All the analyses which follow are based on this Muslim subsample.

Radicalization is most often measured using violence acceptance (van den Bos, 2018), mostly active violence (Vergani et al., 2020). The acceptance of active violence was also measured here, using the item “Violence is justified when it comes to propagating and enforcing Islam”. In addition, the acceptance of a reactive form of violence was measured: “The threat to Islam from the Western world justifies the use of violence by Muslims to defend themselves” (both on a four-point answer scale from 1 = completely agree to 4 = completely disagree; recoded that higher scores indicate stronger agreement). The intercorrelation of r =0.149*** demonstrates that the items do indeed reflect the acceptance of two different forms of violence and are therefore used as two separate indicators.

Demographic factors age (in years), gender (1 = man, 2 = woman), and migrant generation (either born in Germany or with an entry age < 8 years = second generation = 2, others = first generation = 1) were operationalized as personal factors of radicalization.

Two groups of variables were used as push factors. First, indicators of social structure were operationalized using the highest educational qualification (based on the International Standard Classification of Education [ISCED] of UNESCO, 1997: 0 = no secondary education, 2 = lower secondary, 3 = upper secondary, 4 = A-level, and 5 = university or college degree) and being job-seeking (occupational status: fulltime employment, part-time employment, school/apprenticeship, housewife/househusband/not working for other reasons, and retired; single-choice answer format). Second, perceived deprivation was measured using an index of four items:: “Do you get your fair share compared to others in society?” (relative deprivation); “No matter how hard I try, I am not recognized as being part of German society”; “Being of Turkish origin, I feel like a second-class citizen”; and “German society should show greater consideration for the habits and characteristics of Turkish immigrants”. All four items were rated on a four-point answer scale from 1 = completely agree to 4 = completely disagree, which were recoded that higher scores indicate a higher level of perceived deprivation. Cronbach's alpha of the index amounts to α = 0.65. A histogram displaying the frequency distribution of the scores of the perceived-deprivation scale is displayed in Supplementary Figure S9.

Pull factors were operationalized using forms and indicators of religiosity induced from previous studies. Firstly, individual religiosity was measured by three items: religious self-assessment (“How religious would you describe yourself?” was answered on a scale from 1 = deeply religious to 7 = not at all religious; recoded that higher scores indicate higher self-assessed religiosity), frequency of obligatory prayer (salah, from 1 = several times a day to 8 = never; recoded that higher scores indicate higher frequency) and frequency of personal prayer (du'a, from 1 = several times a day to 8 = never; recoded that higher scores indicate higher frequency). The variables were z-standardized before the scale “individual religiosity” was created by averaging the items (α = 0.66). Secondly, collective religiosity was assessed through two items: the frequency of mosque attendance (from 1 = every week or more often to 6 = never; recoded that higher scores indicate higher frequency) and the attachment to the local mosque community (“To what extent do you feel connected to your local mosque community?” 1 very closely connected to 4 = not connected at all; recoded that higher scores indicate stronger attachment). The variables were z-standardized before the scale “collective religiosity” was created by averaging the items (α = 0.68). Thirdly, orthodox religiosity was measured using a single indicator “Muslims should avoid shaking hands with the opposite gender” (from 1 = completely agree to 4 = completely disagree, recoded that higher scores indicate stronger agreement; see also Demmrich and Hanel, 2023). Finally, fundamentalism was measured with the four-item scale by Pollack et al. (2023, forthcoming): “There is only one true religion”, “Obeying the commandments of my religion is more important to me than the laws of the state in which I live”, “Only Islam is able to solve the problems of our time”, “Muslims should strive for a return to a social order like the one that prevailed at the time of the Prophet Mohammed”. Items were answered on a four-point scale (1 = completely agree to 4 = completely disagree; recoded that higher scors indicate higher fundamentalism, α = 0.73). A histogram displaying the frequency distribution of the scores of the fundamentalism scale is displayed in Supplementary Figure S8.

In the current study, active and reactive violence serve as two separate indicators or measures of radicalization (for descriptive statistics see Supplementary Tables S1, S2, Supplementary Figures S1, S2, S8, S9). Utilizing single-item measures for radicalization is a common methodological approach within this research domain (e.g., Beller and Kröger, 2018, 2021; Hadjar et al., 2019; Jakubowska et al., 2021; Koopmans et al., 2021). In this study, a robustness check has been incorporated. Specifically, the two dependent variables used should demonstrate similar relationships to variables commonly examined in radicalization research, such as education, perceived deprivation, age, and gender, when compared to previous studies that also used longer scales, as well as to those that employed single-item measures of radicalization. Table 1 illustrates the bivariate relations between reactive and active violence and the aforementioned variables.

Consistent with prior studies, negative (e.g., Brettfeld and Wetzels, 2007; Canetti et al., 2010; Muluk et al., 2013; Alkhadher and Scull, 2019) to no relations (Barton et al., 2021) were found between radicalization and education, while positive relations were observed to perceived deprivation (e.g., Brettfeld and Wetzels, 2007; Canetti et al., 2010; Muluk et al., 2013). Gender did not exhibit a significant relationship with radicalization (e.g., Brettfeld and Wetzels, 2007; Barton et al., 2021), and age typically showed no correlation with radicalization (e.g., Putra and Sukabdi, 2014; Alkhadher and Scull, 2019; Yustisia et al., 2020; Barton et al., 2021). These findings align with reviews of radicalization research, too (e.g., Koomen and van der Pligt, 2015; Jost, 2017).

However, in our sample, age correlates slightly positively with reactive violence. Given that all referenced studies, except Brettfeld and Wetzels (2007), involve Muslims in non-Western, mainly Muslim-majority contexts, or exclusively young Muslims in Germany (Frindte et al., 2011; Hadjar et al., 2019), the observed positive correlation between age and reactive violence might be specific to the migration context. In the study by Brettfeld and Wetzels, reactive violence is higher among the first generation of migrants (who are usually older) than among their descendants (second generation with a migration background).

Table 1 displays the zero-order correlations between all included variables as well as their means and standard deviations. Regarding radicalization, it is notable that only a minority of the sample express acceptance of violence: 20% somehow or completely accept reactive violence and only 7% somehow or completely accept active violence.

In accordance with the first hypothesis, individual religiosity shows only a very slight correlation with reactive violence and no correlation with active violence. In contrast, collective, orthodox, and fundamentalist religiosity are positively associated with the acceptance of both forms of violence, with fundamentalism emerging as the strongest correlate among all forms of religiosity. With regard to push factors, indicators of social structure play a role only in the negative correlation between education level and reactive violence, while perceived deprivation is positively correlated with the acceptance of both forms of violence. Finally, and as mentioned earlier, personal factors of demography, age and migrant generation exhibit relationships to reactive violence. Due to the positive intercorrelations between all forms of religiosity and their confounding with perceived deprivation and demographic variables, multivariate analyses are conducted in the next stage.

Given the notable differences in individual and orthodox religiosity (higher among women) and particularly collective religiosity (higher among men) between female and male Muslims, additional exploratory analyses concerning the zero-order correlations between women and men are conducted (see Supplementary Table S3). Two observations emerge: Firstly, correlations between all four forms of religiosity and reactive violence are stronger among women than among men or the entire sample (see again Table 1). Conversely, the correlation between collective religiosity and active violence is not significant among women, in contrast to the entire sample (where a small correlation exists) and men (where a stronger and highly significant correlation exists). Secondly, the slight positive correlation between reactive and active violence in the entire sample is more pronounced among men but remains statistically not significant among women.

Hypothesis 2, which posits that the association between religiosity and radicalization remain stable when simultaneously considering personal factors and push factors of radicalization, was investigated through two separate regression analyses. Each analysis comprised three hierarchical steps containing pull, push, and personal factors as predictors of reactive and active violence, respectively (Table 2). In the initial step of both regression analyses, all forms of religiosity were included; the second step introduced indicators of social structure, and the third step incorporated perceived deprivation. Demographic variables were included as control variables in all models.

In the regression analysis on reactive violence (left side of Table 2), only individual religiosity and fundamentalism remain stable when controlling for push and personal factors. Remarkably, fundamentalism emerged as not only the strongest predictor in the initial step but also in the full model. Collective and orthodox religiosity, on the other hand, lost their significance in this model. Interestingly, individual religiosity unexpectedly turned out to be a negative predictor of this form of radicalization.4 The addition of indicators of social structure in the second step did not significantly enhance the explained variance. However, the introduction of perceived deprivation in the third step led to a small but significant increase in the explained variance. Among the demographic control variables, only age displayed a small positive relationship with reactive violence. The full model explains 14 % of variance of reactive violence. Supplementary Figure S3 displays the jitter scatterplot between fundamentalism and reactive violence.

In the regression analysis on active violence (right side of Table 2), neither individual religiosity nor collective religiosity are significant anymore.5 However, orthodox religiosity and fundamentalism are highly significant and positive predictors of equal size. The addition of indicators of social structure in the second step and perceived deprivation in the third step did not significantly increase the variance explanation of the model. The demographic variables age and migrant generation emerged as slightly significant predictors of reactive violence. Consequently, the variance explanation of active violence remained relatively low, at just 5 % for the full model. Supplementary Figures S4, S5 display the jitter scatterplots between fundamentalism and orthodoxy, respectively, and active violence. Notably, a minority of participants express agreement with active violence, leading to the predominant clustering of observations toward the lower left quadrant in both figures.

As an additional robustness check, we tested whether excluding residual outliers would impact the results of the two models 3 presented in Table 2 (i.e., the two models with all predictors). We used two approaches to identify outliers: absolute standardized residuals > 3 and Cook's distance > 4/n. None of the two approaches impacted the results in any of the models, suggesting that the findings are robust.

With regard to the aforementioned gender difference in the relationships between religiosity and radicalization, both regression analyses were performed for exploratory reasons among women and men separately (see Supplementary Tables S6, S7). While demographic variables were much stronger predictors of both radicalization indicators among men, they did not play any role among women. In contrast to the whole sample, individual religiosity was also a negative predictor of active violence, and collective religiosity was a significant positive predictor of active violence among men. Conversely, individual religiosity was not a predictor of any form of radicalization among women, and for the prediction of active violence, only orthodox religiosity remained a significant (and at the same time small) predictor among female Muslims. However, the overall pattern is the same for women and men.

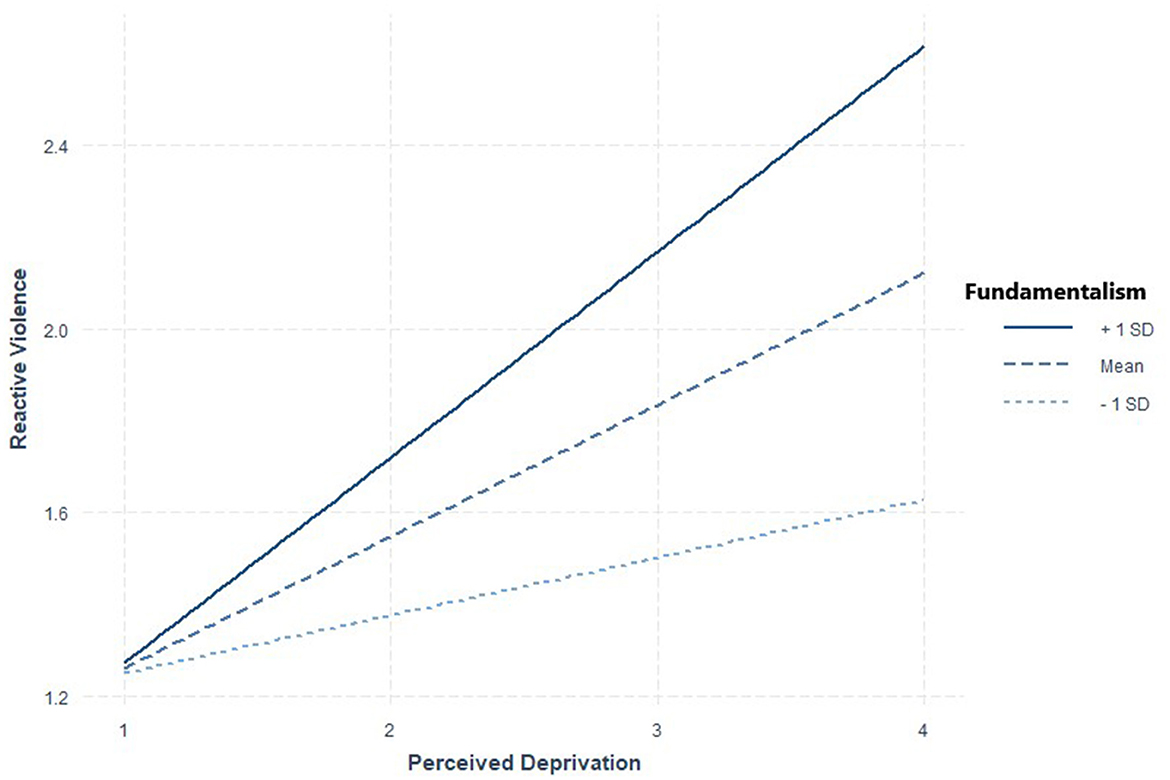

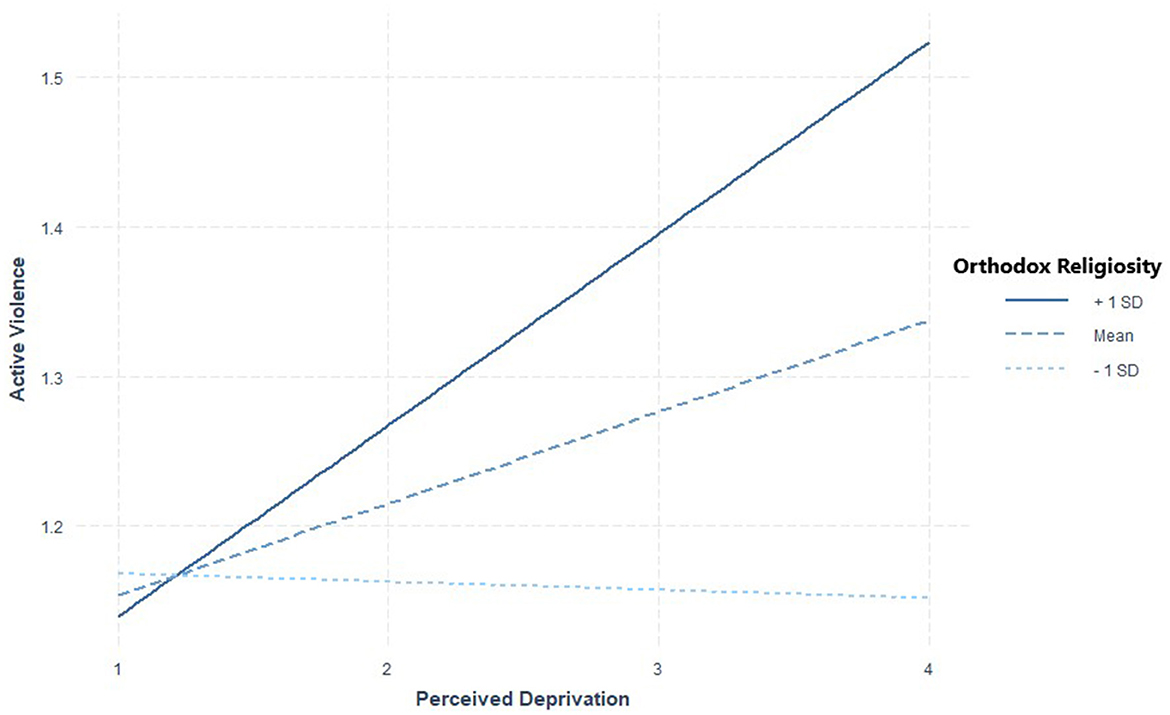

In the final step, it was tested whether the relation between perceived deprivation and radicalization is amplified by orthodox religiosity and fundamentalism, respectively. Two interactions turned out to be significant. First, fundamentalism moderates the relationship between perceived deprivation and reactive violence (β = 0.53, p ≤ 0.003; see Figure 1): the relationship between deprivation and reactive violence is stronger the higher fundamentalism is. Vice versa, no relation appears between fundamentalism and reactive violence when perceived deprivation is low. Similarly, orthodox religiosity moderates the relationship between perceived deprivation and active violence (β = 0.32, p ≤ 0.038; see Figure 2): there seem to be no relationship between deprivation and active violence when orthodoxy is low. In a similar vein, no relationship between orthodox religiosity and active violence appears when perceived deprivation is low. Both moderator terms remained robust when controlled for all other push, pull, and personal factors (see Supplementary Tables S8, S9).

Figure 1. Associations between perceived deprivation and reactive violence moderated by fundamentalism.

Figure 2. Associations between perceived deprivation and active violence moderated by orthodox religiosity.

Additional moderator analyses were conducted with individual religiosity and collective religiosity, respectively, as moderators of the same relationship. None of them yielded significant results.

By using a previously collected sample of Muslims with a Turkish migration background in Germany, it is important to note that the acceptance of reactive and active violence is a phenomenon found among a small minority. With this understanding as a foundation, the primary objective of this secondary analysis was to investigate the connections between different forms of religiosity (individual, collective, orthodox, and fundamentalist religiosity) and the acceptance of reactive and active violence as indicators of radicalization. Hypothesis 1 stated that individual religiosity is not related to radicalization, while collective, orthodox, and fundamentalist religiosity are positively related to the acceptance of both forms of violence. With the exception of the very small and only slightly significant relation between individual religiosity and reactive violence, hypothesis 1 was fully supported by the bivariate analysis. These results are, therefore, in line with the majority of the research outcomes from previous studies (e.g., Brettfeld and Wetzels, 2007; Goli and Rezaei, 2011; Muluk et al., 2013; Putra and Sukabdi, 2014; Acevedo and Chaudhary, 2015; Beller and Kröger, 2018, 2021; Alkhadher and Scull, 2019; Yustisia et al., 2020). It should be emphasized here that despite the focus on Muslims religiosity and Islamist radicalization in research all these four results were replicated among non-Muslims, such as Jews and Christians (Ginges et al., 2009; Canetti et al., 2010; Jakubowska et al., 2021; Koopmans et al., 2021).

Hence, it appears that the link between religiosity and radicalization is not exclusive to the Muslim faith (e.g., Six, 2005; Pratt, 2010). Instead, different forms of religiosity might involve varying underlying psychological mechanisms that can either impede or facilitate the path toward radicalization, irrespective of one's religious affiliation. The coalition-commitment-hypothesis (Ginges et al., 2009) which states that collective—but not individual—religious practices increase ingroup commitment and outgroup hostility, and thus, heightens the probability of further radicalization, can serve as a good example here for theory building. Similarly, it can be further suggested that fundamentalism contributes to a sharp boundary-making, strong biases against (Kanol, 2021) and even dehumanization of outgroups (Herriot, 2009), which might eventually pave a way into radicalization. Since orthodox religiosity is closely related to fundamentalism (see Table 1; e.g., Pollack et al., 2023; Williamson and Demmrich, 2024) similar processes in the sense of sharp boundary making can be expected. Given the cross-sectional nature of this and all previous studies, it is also feasible that radicalization might lead to a more fundamentalist and orthodox interpretation of one's own faith.

Furthermore, it was anticipated that these relationships between forms of religiosity and radicalization would remain stable even when controlling for personal factors (demographics) and push factors (low social-structural position, high perceived deprivation). This Hypothesis 2 was only partially supported by the empirical data. Regarding reactive violence, individual religiosity became a negative predictor once fundamentalism was included. Similarly, collective religiosity and orthodox religiosity lost their significance once the same variable was taken into account. Notably, fundamentalism emerged as the strongest predictor. Among push factors, only perceived deprivation (but not education or being job seeking) proved to be a highly significant predictor. As for personal factors, only age played a minor role in predicting reactive violence. Concerning active violence, individual religiosity remained non-significant, and collective religiosity lost its significance when considered simultaneously with individual religiosity. Nevertheless, given that only a minority subscribes to active violence, the observations regarding the associations between fundamentalism and orthodox religiosity, respectively, and active violence tend to cluster toward lower scores within these relationships. Consequently, both effects warrant cautious interpretation. Future studies seeking to replicate these findings may benefit from employing alternative sampling methods, such as recruiting participants from radical groups (e.g., Heinke, 2017; Alkhadher and Scull, 2019).

Returning to the regression analysis on active violence, none of the push factors yielded significant results in this multivariate analysis but age and the second migrant generation play were slightly significant personal predictos of active violence. The low variance explanation for the prediction of active violence (especially among female Muslims) could be enhanced in future studies by introducing additional variables into the 3 Ps-framework. These variables might include personality traits as personal factors (e.g., authoritarianism, Jakubowska et al., 2021), pull factors like enemies images (Mashuri and Zaduqisti, 2019) or group dynamics (e.g., social networks, Bélanger et al., 2019), or push factors such as social-psychological needs (e.g., quest for significance, Jasko et al., 2017)

In summary, it seems that neither the individual's social-structural position (e.g., Piazza, 2011; cf. Della Porta, 2013; van den Bos, 2018) nor personal (demographic) factors play a major role in radicalization (see Borum, 2015; Koomen and van der Pligt, 2015). Instead, the predominant factors of this phenomenon are found in the pull factors associated with various forms of religiosity, as they explain the highest share of variance. Specifically, it seems that individual religiosity functions as a buffering factor against reactive violence (Zhirkov et al., 2012; Beller and Kröger, 2018). However, the dynamics of collective religiosity are absorbed by fundamentalism and individual religiosity (cf. Ginges et al., 2009; Beller, 2017; Beller and Kröger, 2021). Orthodox religiosity seems to play a role in active violence (Brettfeld and Wetzels, 2007; Goli and Rezaei, 2011), while fundamentalism emerges as the strongest factor in reactive violence and, with more caution due to low variance, in active violence (e.g., Alkhadher and Scull, 2019; Yustisia et al., 2020; Jakubowska et al., 2021; Koopmans et al., 2021). These findings corroborate the theories of scholars who emphasize a relation between (orthodox and fundamentalist) religiosity and radicalization (Six, 2005; Pratt, 2010; Wright, 2016; Khorchide, 2020). Despite typically being non-violent (Williamson, 2020), fundamentalism is characterized by exclusive beliefs, considered superior to all other worldviews, universally applicable to all aspects of the world, and requiring realization through a return to a past “Golden Age” (Pollack et al., 2023). This constitutes a coherent worldview that simplifies the complexities of the surrounding world into a black-and-white dualism (see Williamson and Demmrich, 2024). Additionally, fundamentalism may lead to the ingroup/outgroup dynamics described above and correlate with moral values that possess the potential to incite violence (Ginges et al., 2011).

While the bivariate findings of this study align with the majority of prior research, the results obtained through the multivariate analyses deviate somewhat from previous outcomes and, as a result, differ from the expectations outlined in Hypothesis 2. This deviation could be attributed the adoption of the comprehensive framework known as the three Ps of radicalization (Vergani et al., 2020). Applying this framework avoids essentializing religiosity, instead encompassing various other pertinent factors related to radicalization. Therefore, the primary aim of this study was to examine the relative role of religiosity in the context of radicalization. It is worth noting that the only prior study which also integrated personal and push factors alongside religiosity as a pull factor was conducted by Beller and Kröger (2021) and found no significant associations between religiosity and radicalization. From a broader perspective, factors of radicalization and their interactions can vary for particular individuals or groups, contexts, and times (Fair and Shepherd, 2006; Vergani et al., 2020) and this may explain the variations found in the studies on the religiosity-radicalization-link introduced here. Therefore, such diverging results may be not generalizable to individuals or groups beyond Muslims with a Turkish migration background in Germany, just as Beller and Kröger's (2021) results among highly educated and socially advantaged Muslims in the USA may not be generalizable to Muslims from other contexts (see Alba and Foner, 2015). Further investigations could search for radicalization factors that are consistent across contexts and (religious and non-religious) worldviews (Ginges et al., 2009; van den Bos, 2018; Jakubowska et al., 2021; Koopmans et al., 2021). A meta-analysis, which has yet to be done, would also shed more light on the religiosity-radicalization-link including cross-context variations. In addition to such contextual variations, and as the exploratory results on gender differences show, radicalization research could benefit more from a gender perspective, particularly given the underdeveloped analysis of women in this field. This is because results within the framework of the 3Ps of radicalization (especially personal factors and pull factors of religiosity) appear to be influenced by gender.

Returning to the regression analyses of the whole sample, perceived deprivation served as a significant push factor in reactive violence but does not exhibit the same effect in active violence. In light of this observation, it was finally examined whether orthodox religiosity and fundamentalism play a moderating role in the deprivation-radicalization association. The results partially support this third hypothesis, as medium to high levels of orthodox religiosity were found to establish a link between perceived deprivation and active violence. Additionally, the positive relationship between perceived deprivation and reactive violence was intensified under conditions of high fundamentalism. Both closely related forms of religiosity—orthodoxy religiosity and fundamentalism—appear to provide a frame for making sense of perceived deprivation (Snow and Byrd, 2007; Aslan et al., 2017) and accelerate the radicalization process (van den Bos, 2018).

Approaching the issue from a different angle, it appears that a certain level of perceived deprivation is crucial for the relationship between fundamentalism/orthodox religiosity, and radicalization to emerge. It is imperative for future research to investigate whether such interaction effects involving perceived deprivation, fundamentalism/orthodox religiosity, and radicalization are specific to religious groups living in minority contexts. For example, studies have shown that fundamentalism among Muslims in Turkey is less prevalent among deprived individuals (Demmrich and Hanel, 2023), and within the same context, relationship between perceived deprivation and radicalization are not significant (Demmrich and Hanel, forthcoming). Perceived deprivation, such as instances of anti-Muslim discrimination, which are reportedly high in Western countries (Yendell and Pickel, 2019; United Nations, 2023), could be effectively addressed through interventions that promote a sense of belonging at the individual, community, and institutional levels. A crucial factor in this context seems to be perceived procedural justice, which encompasses elements such as the opportunity to voice one's opinions, respectful and polite communication, fair evaluations, and the presence of competent authorities. This fosters a sense of societal value, leading to trust in others, openness to different perspectives, and a related reduced propensity for exclusive and superior beliefs (van den Bos, 2024). However, it was not possible to investigate whether there exists a buffering effect of more liberal forms of religiosity (see van den Bos, 2023) due to the absence of this variable in this previously collected dataset. Subsequent studies should address this gap by examining forms of religiosity that may mitigate the deprivation-radicalization nexus, such as a reform-oriented interpretation of Islam (Senel and Demmrich, 2024). To pursue this further line of research may also serve as a bridge between the reactivity hypothesis and the religiosity-radicalization approach, which are often depicted as antipodes.

In terms of additional limitations, this cross-sectional investigation is epistemologically limited to non-causal statements. Causal mechanisms, as implied by the reactivity hypothesis, but also by the religiosity-radicalization approach, should be further clarified through experimental and longitudinal studies. Furthermore, single-item measures for orthodox religiosity and the two forms of violence acceptance were used. There exists an ongoing debate in the literature regarding the use of single-item measures and their potential impact on the validity of a study (Bakker and Lelkes, 2018). However, most studies comparing single-item to multi-item scales tend to agree that single-item measures can produce similar findings (Spörrle and Bekk, 2014). More importantly, an examination of the correlations between the single-item measures and other variables (see Table 1) indicates that they align with the theoretical expectations and previous empirical findings in the literature. Additionally, it is important to acknowledge a general limitation of the study, which is the utilization of a weighted sample rather than a probability sampling method. Probability sampling is generally considered to be a more robust approach (Yang and Banamah, 2014). However, it is worth noting that structural differences between the sample and population were minimized by factorial weighting based on the 2014 microcensus of the population with a Turkish migration background in Germany, in terms of age, gender, education level, occupational status, and citizenship. Therefore, it exhibits a higher level of representativeness compared to many other psychological studies, which often rely on student or convenience samples (Davis et al., 2024).

Turning to the indicators of radicalization, which are on the level of attitudes (Vergani et al., 2020), a significant question remains: how applicable are these attitude measurements to understanding radicalization beyond the scope of our questionnaires? Nevertheless, the assessment of these attitudes is far from inconsequential in the context of radicalization (see Gaspar et al., 2019; Pickel and Pickel, 2023), as such a cognitive radicalization can serve as a fertile ground for nurturing the ideologies and motivations of radical organizations (Krueger and Malečková, 2009) and radical behaviors (van den Bos, 2018; Moskalenko and McCauley, 2020).

The data and the methodological report are available at https://osf.io/vyreh/?view_only=acda2880d79f48889b162c2e7923ee11. Furthermore, the SPSS and R codes are provided for access at https://osf.io/24wem/?view_only=d8f754b087db4c9a9a3e4914c9ff9f67.

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because there are no Ethics Committees at German Universities outside Medical Departments. Therefore, all procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the 2013 Helsinki Declaration and the ethics guidelines from the institution the author. Additionally, the author confirms that the manuscript adheres to ethical guidelines specified in the APA Code of Conduct as well as the German national ethics guidelines (DGPs: https://www.dgps.de/die-dgps/aufgaben-und-ziele/berufsethische-richtlinien/). This research is conducted ethically, results are reported honestly, the submitted work is original and not (self-)plagiarized. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

SD: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation. PH: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This paper was based on research findings from projects “Between aspiration and reality: Cultural and social integration in the self-image of Muslims of Turkish Origin in Germany” and “Religious fundamentalism” at the Cluster of Excellence “Religion and Politics” at the University of Münster. The author would like to thank the German Research Foundation (DFG) for the financial support of both projects. In addition, we acknowledge support from the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Münster.

We thank Dr. Alexander Yendell and Eyyüp Kaboǧan for intensive feedback on and consultation of the manuscript. Special thanks also go to Abdulkerim Şenel for the same reasons, as well as for technical support in the visualization of the figures.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsps.2024.1406688/full#supplementary-material

1. ^Muslims constitute a significant share of the European population (Goli and Rezaei, 2011) and Germany stands out in this regard as it is currently home to ~5.3–5.6 million Muslims with a migration background, representing ~6.4%−6.7% of its total population. Of these, the majority are from a Turkish migration background (about 2.4–2.5 million, see Pfündel et al., 2021).

2. ^Brettfeld and Wetzels (2007) also collect data on reactive violence, but they formed a group labeled “high legitimacy of religious/politically motivated violence and/or high distance from democracy” based on this and other indicators.

3. ^Note that we are using push, pull, and personal factors merely as a way to cluster our variables and link them to previous research and theories. We do not propose a hierarchical model in which personal factors such as age or gender would load on the same latent variable which then in turn would predict violence. However, we have added two SEMs in Supplementary Figures S6, S7.

4. ^Supplementary Table S4 shows that collective religiosity and orthodox religiosity are no longer significantly associated with reactive violence once fundamentalism is included, which in turn is a positive predictor. On the other side, individual religiosity turns out a significant negative predictor once fundamentalism is controlled for.

5. ^Supplementary Table S5 shows that collective religiosity loses its previously small positive zero-order relationship with active violence once orthodox religiosity is added to the regression. In contrast, adding fundamentalism in the last steps does not change the previous bivariate findings between orthodox religiosity and active violence.

Acevedo, G. A., and Chaudhary, A. R. (2015). Religion, cultural clash, and Muslim American attitudes about politically motivated violence. J. Sci. Study Relig. 54, 242–260. doi: 10.1111/jssr.12185

Ahmad, A. (2014). The role of social networks in the recruitment of youth in an Islamist organization in Pakistan. Sociol. Spect. 34, 469–488. doi: 10.1080/02732173.2014.947450

Alkhadher, O., and Scull, N. C. (2019). Demographic variables predicting ISIS and Daesh armed political violence. Crime, Law Soc. Change 72, 183–194. doi: 10.1007/s10611-018-9808-5

Amirpur, K. (2015). “Islam – violence and non-violence,” in Gewaltfreiheit und Gewalt in den Religionen, eds. F. Enns and W. Weiße (Münster: Waxmann), 313–321.

Aslan, E., Akkiliç, E. E., and Hämmerle, M. (2017). Islamist Radicalization: Biographical Processes in the Context of Religious Socialization and the Radical Milieu. Cham: Springer.

Bakker, B. N., and Lelkes, Y. (2018). Selling ourselves short? How abbreviated measures of per-sonality change the way we think about personality and politics. J. Polit. 80, 1311–1325. doi: 10.1086/698928

Barton, G., Vergani, M., and Wahid, Y. (2021). Santri with attitude: Support for terrorism and negative attitudes to non-Muslims among Indonesian observant Muslims. Behav. Sci. Terror. Polit. Aggres. 15, 321–335. doi: 10.1080/19434472.2021.1944272

Bélanger, J. J., Moyano, M., Muhammad, H., Richardson, L., Lafrenière, M. A. K., McCaffery, P., et al. (2019). Radicalization leading to violence: a test of the 3N model. Front. Psychiatry 10:42. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00042

Beller, J., and Kröger, C. (2018). Religiosity, religious fundamentalism, and perceived threat as predictors of Muslim support for extremist violence. Psycholog. Relig. Spiritual. 10, 345–355. doi: 10.1037/rel0000138

Beller, J., and Kröger, C. (2021). Religiosity and perceived religious discrimination as predictors of support for suicide attacks among Muslim Americans. Peace Conflict 27, 554–567. doi: 10.1037/pac0000460

Borum, R. (2015). Assessing risk for terrorism involvement. J. Threat Assessm. Manage. 2, 63–87. doi: 10.1037/tam0000043

Brettfeld, K., and Wetzels, P. (2007). Muslime in Deutschland [Muslims in Germany]. Berlin: German Interior Ministry.

Canetti, D., Hobfoll, S. E., Pedahzur, A., and Zaidise, E. (2010). Much ado about religion. J. Peace Res. 47, 575–558. doi: 10.1177/0022343310368009

Davis, E. B., Lacey, E. K., Heydt, E. J., LaBouff, J. P., Barker, S. B., Van Elk, M., et al. (2024). Sixty years of studying the sacred: auditing and advancing the psychology of religion and spirituality. Psycholog. Relig. Spiritual. 16, 7–19. doi: 10.1037/rel0000485

de Graaf, B. A., and van den Bos, K. (2021). Religious radicalization: social appraisals and finding radical redemption in extreme beliefs. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 40, 56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.08.028

Demmrich, S., and Hanel, P. (2023). When religious fundamentalists feel privileged: findings from a representative study in contemporary Turkey. Curr. Res. Ecol. Soc. Psychol. 4:100115. doi: 10.1016/j.cresp.2023.100115

Demmrich S. Hanel P. (forthcoming). Religious Fundamentalism and Radicalization: How nationalist-Islamist Party Politics Polarizes Turkey – How Polarization can be Reduced.

Demmrich S. Senel A. (forthcoming). Entitativity as a Moderator? A Brief Report Unraveling the Relations Between Discrimination, Fundamentalism, and Radicalization.

Fair, C. C., and Shepherd, B. (2006). Who supports terrorism? Coastal Manage. 29, 51–74. doi: 10.1080/10576100500351318

Fleischmann, F., Phalet, K., and Klein, O. (2011). Religious identification and politicization in the face of discrimination: support for political Islam and political action among the Turkish and Moroccan second generation in Europe. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 50, 628–648. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.2011.02072.x

Frindte, W., Ben Slama, B., Dietrich, N., Pisoiu, D., Uhlmann, M., and Kausch, M. (2016). Wege in die Gewalt [Paths to violence]. Available online at: http://www.~hsfk.de/fileadmin/HSFK/hsfk_publikationen/report_032016.pdf (accessed July 4, 2024).

Frindte, W., Boehnke, K., Kreikenbom, H., and Wagner, W. (2011). Lifeworlds of young Muslims in Germany. Berlin: Federal Ministry of the Interior.

Gaspar, H. A., Daase, C., Deitelhoff, N., Junk, J., and Sold, M. (2019). “Vom Extremismus zur Radikalisierung: Zur wissenschaftlichen Konzeptualisierung illiberaler Einstellungen [From extremism to radicalization: on the scientific conceptualization of illiberal attitudes],” in Gesellschaft Extrem: Was wir über Radikalisierung wissen [Society Extreme: What We Know About Radicalization], eds. C. Daase, N. Deitelhoff, and J. Junk (New York, NY: Frankfurt), 15–44.

Ginges, J., Atran, S., Sachdeva, S., and Medin, D. (2011). Psychology out of the laboratory. Am. Psychol. 66, 507–519. doi: 10.1037/a0024715

Ginges, J., Hansen, I., and Norenzayan, A. (2009). Religion and support for suicide attacks. Psychol. Sci. 20, 224–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02270.x

Goli, M., and Rezaei, S. (2011). Radical Islamism and migrant integration in Denmark. J. Strat. Secur. 4, 81–114. doi: 10.5038/1944-0472.4.4.4

Hadjar, A., Schiefer, D., Boehnke, K., Frindte, W., and Geschke, D. (2019). Devoutness to Islam and the attitudinal acceptance of political violence among young Muslims in Germany. Polit. Psychol. 40, 205–222. doi: 10.1111/pops.12508

Jakubowska, U., Korzeniowski, K., and Radkiewicz, P. (2021). Social worldviews and personal beliefs as risk factors for radicalization: a comparison between Muslims and non-Muslims living in Poland. Int. J. Conf. Violence 15, 1–14. doi: 10.11576/ijcv-4717

Jasko, K., LaFree, G., and Kruglanski, A. (2017). Quest for significance and violent extremism: The case of domestic radicalization. Polit. Psychol. 38, 815–831. doi: 10.1111/pops.12376

Jost, J. (2017). The state of research on radicalization. SIRIUS-Zeitschrift für Strategische Analysen 1, 80–89. doi: 10.1515/sirius-2017-0021

Kanol, E. (2021). Explaining unfavorable attitudes toward religious out-groups among three major religions. J. Sci. Study Relig. 60, 590–610. doi: 10.1111/jssr.12725

Khorchide, M. (2020). “Der Politische Islam als Gegenstand wissenschaftlicher Auseinandersetzungen,” in Der Politische Islam als Gegenstand wissenschaftlicher Auseinandersetzungen am Beispiel der Muslimbruderschaft, eds. M. Khorchide and L. Vidino (Berlin: Documentation Centre Political Islam), 3.17.

Kiefer, M., Hüttermann, J., Dziri, B., Ceylan, R., Roth, V., Srowig, F., et al. (2017). Let us Make a Plan, in Sha'a Allah. Cham: Springer.

Kiper, J., and Sosis, R. (2021). “The roots of intergroup conflict and the co-optation of the religious system,” in The Oxford Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology and Religion, eds. J. R. Liddle, and T. K. Shackelford (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 265–282.

Koomen, W., and van der Pligt, J. (2015). The Psychology of Radicalization and Terrorism. London: Routledge.

Koopmans, R., Kanol, E., and Stolle, D. (2021). Scriptural legitimation and the mobilisation of support for religious violence. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 47, 1498–1516. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2020.1822158

Krueger, A. B., and Malečková, J. (2009). Attitudes and action: Public opinion and the occurrence of international terrorism. Science 325, 1534–1536. doi: 10.1126/science.1170867

Kruglanski, A. W. (2018). Violent radicalism and the psychology of prepossession. Soc. Psychol. Bullet. 13, 1–18. doi: 10.32872/spb.v13i4.27449

Mashuri, A., and Zaduqisti, E. (2019). Explaining Muslims' aggressive tendencies towards the West: the role of negative stereotypes, anger, perceived conflict and Islamic fundamentalism. Psychol. Dev. Soc. J. 31, 56–87. doi: 10.1177/0971333618819151

Moskalenko, S., and McCauley, C. (2020). Radicalization to Terrorism: What Everyone Needs to Know. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Muluk, H., Sumaktoyo, N. G., and Ruth, D. M. (2013). Jihad as justification. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 16, 101–111. doi: 10.1111/ajsp.12002

Ozer, S., and Bertelsen, P. (2018). Capturing violent radicalization. Scand. J. Psychol. 59, 653–660. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12484

Piazza, J. A. (2011). Poverty, minority economic discrimination, and domestic terrorism. J. Peace Res. 48, 339–353. doi: 10.1177/0022343310397404

Piazza, J. A. (2012). Types of minority discrimination and terrorism. Conf. Manage. Peace Sci. 29, 521–546. doi: 10.1177/0738894212456940

Pickel, S., and Pickel, G. (2023). “Radical Islam versus radical anti-Islam,” in Gesellschaftliche Ausgangsbedinungen für Radikalisierung und Co-Radikalisierung, eds. S. Pickel, G. Pickel, O. Decker, I. Fritsche, M. Kiefer, F. M. Lütze, et al. (Cham: Springer), 1–30.

Pisoiu, D. (2012). Islamist Radicalisation in Europe: An Occupational Change Process. London: Routledge.

Pollack, D. (2014). “Perception and acceptance of religious diversity in selected European countries: Initial observations,” in Grenzen der Toleranz. Wahrnehmung und Akzeptanz religiöser Vielfalt in Europa, eds. D. Pollack, O. Müller, G. Rosta, N. Friedrichs, and A. Yendell (Cham: Springer), 13–34.

Pollack, D., Demmrich, S., and Müller, O. (2023). Editorial – Religious fundamentalism: new theoretical and empirical challenges across religions and cultures. J. Relig. Soc. Polit. 7, 1–11. doi: 10.1007/s41682-023-00159-y

Pollack D. Müller O. Demmrich S. (forthcoming). Religious Fundamentalism among Muslims of Turkish Origin in Germany.

Pollack, D., Müller, O., Rosta, G., and Dieler, A. (2016). Integration und Religion aus der Sicht von Türkeistämmigen in Deutschland [Integration and Religion from the Perspective of People of Turkish Origin in Germany]. Repräsentative Erhebung von TNS Emnid im Auftrag des Exzellenzclusters “Religion und Politik” der Universität Münster. Available at: https://www.uni-muenster.de/imperia/md/content/religion_und_politik/aktuelles/2016/06_2016/study_integration_and_religion_as_seen_by_people_of_turkish_origin_in_germany.pdf

Pratt, D. (2010). Religion and terrorism: Christian fundamentalism and extremism. Terror. Polit. Violence 22, 438–456. doi: 10.1080/09546551003689399

Putra, I. E., and Sukabdi, Z. A. (2014). Can Islamic fundamentalism relate to nonviolent support? Peace Conflict 20, 583–589. doi: 10.1037/pac0000060

Senel, A., and Demmrich, S. (2024). Prospective Islamic Theologians and Islamic religious teachers in Germany: between fundamentalism and reform orientation. Br. J. Relig. Educ. doi: 10.1080/01416200.2024.2330908

Six, C. (2005). ““Hinduise all politics & militarize Hindudom!!!”: Fundamentalism in Hinduism,” in Religiöser Fundamentalismus, eds. C. Six, M. Riesebrodt, and S. Haas (Innsbruck: StudienVerlag), 247–268.

Snow, D., and Byrd, S. (2007). Ideology, framing processes, and Islamic terrorist movements. Int. Quart. 12, 119–136. doi: 10.17813/maiq.12.2.5717148712w21410

Spörrle, M., and Bekk, M. (2014). Meta-analytic guidelines for evaluating single-item re-liabilities of personality instruments. Assessment 21, 272–285. doi: 10.1177/1073191113498267

UNESCO (1997). International Standard Classification of Education [Technical Report]. UNESCO. Available at: http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/international-standard-classification-of-education-1997-en_0.pdf

United Nations (2023). International day to combat Islamophobia. Available at: https://www.un.org/en/observances/anti-islamophobia-day (accessed July 4, 2024).

van den Bos, K. (2018). Why People Radicalize: How Unfairness Judgments are Used to Fuel Radical Beliefs, Extremist Behaviors, and Terrorism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

van den Bos, K. (2023). “Why people radicalize: The role of perceived injustice and religion [Keynote],” in Conference of the International Association for the Psychology of Religon (IAPR) (Groningen: University of Groningen). Available at: https://www.netherlands.iaprweb.org/ (accessed July 4, 2024).

van den Bos, K. (2024). The Fair Process Effect: Overcoming Distrust, Polarization, and Conspiracy Thinking. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Vergani, M., Iqbal, M., Ilbahar, E., and Barton, G. (2020). The three Ps of radicalization. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 43, 854–854. doi: 10.1080/1057610X.2018.1505686

Williamson, W. P. (2020). Conjectures and controversy in the study of fundamentalism. Brill Res. Persp. Relig. Psychol. 2, 1–94. doi: 10.1163/25897128-12340005

Williamson, W. P., and Demmrich, S. (2024). An International Review of Empirical Research on the Psychology of Fundamentalism. Leiden: Brill.

Wright, J. D. (2016). Why is contemporary religious terrorism predominantly linked to Islam? Persp. Terror. 10, 19–31.

Yang, K., and Banamah, A. (2014). Quota sampling as an alternative to probability sampling? An experimental study. Sociol. Res. Online 19, 56–66. doi: 10.5153/sro.3199

Yendell, A., and Pickel, G. (2019). Islamophobia and anti-Muslim feeling in Saxony – theoretical approaches and empirical findings based on population surveys. J. Contemp. Eur. Stud. 28, 85–99. doi: 10.1080/14782804.2019.1680352

Yustisia, W., Putra, I. E., Kavanagh, C., Whitehouse, H., and Rufaedah, A. (2020). The role of religious fundamentalism and tightness-looseness in promoting collective narcissism and extreme group behavior. Psycholog. Relig. Spiritual. 12, 231–240. doi: 10.1037/rel0000269

Keywords: radicalization, deprivation, fundamentalism, orthodox religiosity, individual religiosity

Citation: Demmrich S and Hanel PHP (2024) The relative role of religiosity in radicalization: how orthodox and fundamentalist religiosity are linked to violence acceptance. Front. Soc. Psychol. 2:1406688. doi: 10.3389/frsps.2024.1406688

Received: 25 March 2024; Accepted: 25 July 2024;

Published: 30 August 2024.

Edited by:

Kristin Laurin, University of British Columbia, CanadaReviewed by:

Michael Pasek, University of Illinois Chicago, United StatesCopyright © 2024 Demmrich and Hanel. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sarah Demmrich, a2Fib2dhbkB1bmktbXVlbnN0ZXIuZGU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.