- 1Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, United States

- 2Department of Psychology, University of Hartford, West Hartford, CT, United States

- 3Department of Psychology, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY, United States

Democrats and Republicans increasingly demonstrate negative intergroup attitudes, posing a threat to bipartisan progress. Based on the Common Ingroup Identity Model, people from different political groups can simultaneously identify with a superordinate group, such as a national identity. This has the potential to ameliorate negative intergroup attitudes, though high levels of national identity are also associated with authoritarianism and intolerance. How can a common national identity improve relations between Democrats and Republicans? In this observational study (N = 1,272), Democrats and Republicans differed in how they defined what it means to be American, and higher American identity was related to more positive attitudes toward members of the other party. Most importantly, this relationship was moderated by participants' definition of what it means to be “American,” regardless of party or political orientation. Those who defined what it means to be American in more restrictive terms (i.e., U.S.-born, English-speaking, and Christian) reported less positive attitudes toward members of the other political party as their identification as an American became stronger. Taken together, our results suggest that strengthening national identity might be key to improving attitudes between Democrats and Republicans, as long as this identity is inclusive.

Introduction

Political polarization in the United States is on the rise, with greater ideological gaps between Democrats and Republicans (Pew Research Center, 2014, 2019). These ideological gaps have been linked to views regarding climate change (Egan and Mullin, 2017), attitudes and behaviors in response to the pandemic (Druckman et al., 2021), and the January 6, 2021, insurrection at the U.S. Capitol (Hinsz and Jackson, 2022). One key aspect of this gap is the affective and attitudinal polarization of Democrats and Republicans, who increasingly dislike and distrust members of the opposing party (Iyengar et al., 2019). From 2016 to 2019, the percentage of Republicans who have a negative view of Democrats increased by 14%, and the percentage of Democrats who have a negative view of Republicans rose by 41% (Pew Research Center, 2019). Many Democrats and Republicans even view the other party as a threat to the nation's wellbeing and long-term survival (Pew Research Center, 2014). While political polarization has been on the rise in many other democratic countries (McCoy et al., 2018), the political system in the U.S. might make it especially vulnerable to these changes. The political system in the U.S. is a compromise-based, two-party system, which is unlike many other democracies that require coalitions to govern. Thus, political animosity can be particularly damaging to political progress in the U.S., as cooperation and collaboration between Democrats and Republicans are often necessary to compromise and reach legislative solutions.

The animosity that is born from political polarization is linked to anti-democratic attitudes, such as rejecting policies one would otherwise support, simply because these policies originate from the opposing party (Cohen, 2003; Kingzette et al., 2021; Dias and Lelkes, 2022). In fact, higher party polarization is related to a higher likelihood of encountering legislative gridlock (Jones, 2001) and has the potential to impede bipartisan efforts by preventing legislation to parallel public opinion. For instance, for the past 50 years, most Americans have consistently supported legal abortion in specific circumstances (Smith and Son, 2013; Gallup, 2023), as protected by the Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision. However, after the recent Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization ruling that effectively overturned Roe v. Wade, attempts to establish federal-level protection for abortion rights have been unsuccessful due to a lack of bipartisan support (Karni, 2022).

Negative attitudes toward members of the other party have also been linked to support for violence, including the use of violence to achieve political goals (Kalmoe and Mason, 2022; Piazza, 2023). Between 2017 and 2021, support for political violence among both Democrats and Republicans increased (Kalmoe and Mason, 2022). Following these attitudes, the past 5 years have demonstrated a significant surge in acts of political violence in the United States, ranging from death threats targeting government officials to the January 6, 2021 attack on the U.S. Capitol aiming to overturn the 2020 presidential election (Kleinfeld, 2022).

Considering the negative consequences of existing political tension, research efforts should be allocated to understanding ways to improve relations between people who identify with different political parties (e.g., Democrats, Republicans). One possible way of doing so is via a common American identity (Levendusky, 2018; Hartman et al., 2022). However, research on common identity in Democrats and Republicans has overlooked the fact that individuals have different conceptualizations of what it means to be “American” (Connaughton, 2021). Therefore, our research focuses on understanding how these different conceptualizations may influence the relationship between having a common American identity and attitudes between Democrats and Republicans.

Common ingroup identity model

Social categorization, such as forming distinct groups, leads to the development of social identities, where individuals identify with specific social groups (Turner et al., 1987; Abrams and Hogg, 1988). Social identity processes have far-reaching effects on various intergroup and psychological phenomena, such as leading to negative attitudes and discrimination between groups (Stephan and Stephan, 1985; Tajfel and Turner, 2004; Gordils et al., 2021, 2023). Social group identities are not fixed; they can be influenced by categorization processes, such as reducing identification with ingroups (e.g., Wilder and Allen, 1978; Gaertner et al., 1993; Dovidio et al., 1995; Van Bavel and Cunningham, 2010), or redefining group boundaries (Dovidio et al., 2000; Brewer, 2011). For instance, cooperation during a pandemic could signal shared goals, which may create a sense of community for groups that were previously considered outgroups (Bavel et al., 2020).

Similarly, the Common Ingroup Identity Model (CIIM) suggests that individuals from different groups can recategorize themselves into a superordinate identity category (Gaertner et al., 1993). In this scenario, members of subordinate groups view themselves as part of a broader, shared group identity. Embracing this superordinate identity, therefore, extends the favoritism that individuals show to members of their own group to those who were once perceived to belong to other groups, reducing intergroup tension (Dovidio et al., 2008).

Past work has documented the efficacy of adopting a common group identity on positive outcomes, including but not limited to more positive intergroup attitudes, a greater willingness for intergroup contact, helping outgroup members, and intergroup trust (Riek et al., 2010; Penner et al., 2013; Vezzali et al., 2015). Additionally, this model has been shown to be effective across myriad social contexts such as high schools, universities, and workplaces, and is applicable across different nationality groups (Hindriks et al., 2014; Dietz et al., 2015; Toprakkiran and Gordils, 2021; Cehajić-Clancy et al., 2023). Despite the robustness of this model, past work has also documented instances where the applications of the model may be less unequivocally clear. For instance, policies that highlight commonalities between groups, such as colorblindness, may hinder efforts for equality (Dovidio et al., 2016). Furthermore, increasing a common identity, such as a national identity, may promote negative attitudes toward those perceived as belonging to other national groups, such as immigrants (Wojcieszak and Garrett, 2018). Taken together, the common ingroup identity model sometimes fosters and sometimes hinders positive intergroup attitudes.

One explanation as to why increasing the salience of a common identity might not improve intergroup attitudes may be due to existing conceptualizations individuals hold of the given common identity. In other words, if common identities are construed differently across individuals from different groups, this might influence the outcomes of creating a common identity. However, the literature on common identity has mostly overlooked this potential issue. To better understand the conceptualizations of common identities, researchers must assess conceptual equivalence (i.e., whether a particular construct has the same meaning across social groups; Berry, 2002; Harachi et al., 2006; Trimble, 2007). For instance, if researchers plan to examine the outcomes of a common American identity between Democrats and Republicans, it might be necessary to understand the nuanced conceptualizations of what it means to be an American to members of each group.

A common American identity

One way of creating a common identity for Democrats and Republicans is by invoking a shared, superordinate national identity. Indeed, previous research shows that priming a common American identity decreases negative attitudes between Democrats and Republicans (Levendusky, 2018). However, as partisans may differ on their conceptualizations of what it means to be American, said differences may create contention between rival parties and attenuate positive effects of shared identities. As such, a common American identity might function as a double-edged sword.

Specifically, how people define the boundaries of a broader American identity might determine who they exclude from this common identity, and thus persist as categorizing compatriots as outgroup members. For example, for those who believe that the American identity necessitates being Christian, increasing an American identity may be linked to higher negative attitudes toward those who are not (or perceived to not be) Christian. Christian nationalism implies the exclusion of non-Christian religious groups from a national identity (Delehanty et al., 2019). In the United States, the importance of religion is linked to anti-Muslim prejudice in Christian respondents (Ogan et al., 2014). Additionally, for individuals who believe that being American encompasses being born in the U.S., a higher American identity may be related to higher negative attitudes toward those who are foreign-born. Higher national identity may increase hostility toward immigrants by enhancing the salience of group boundaries (Wojcieszak and Garrett, 2018). While 14% of the United States population is made up of immigrants (Budiman, 2020), 41% of U.S. Americans believe that immigration should be decreased (Saad, 2023). Further, for individuals who believe that speaking English is necessary to be a true American, a higher American identity may be linked to higher negative attitudes toward those who do not speak English. In a 2017 Pew Research survey, 70% of respondents reported that it is very important to be able to speak English to be considered “American” (Stokes, 2017). The literature on linguistic prejudice shows that accented speech (i.e., accents spoken by minoritized groups and/or viewed as foreign) is related to interpersonal evaluations and the differentiation between ingroup and outgroup members (Fuertes et al., 2012).

Together, those that endorse a more restrictive and exclusionary definition of “being American” may be less likely to view outgroup members as part of the superordinate ingroup, and thus are likely to view outgroups more negatively (or less positively), and by extension, less likely to benefit from the advantages posited by the common ingroup identity model. In the present work, we specifically focus on the aforementioned factors (i.e., being a Christian, being born in the U.S., and being able to speak English) and the degree to which partisans find these factors important for what it means to be “truly American.”

Current research

Previous work found that Democrats and Republicans define what it means to be American differently. More specifically, when it comes to being “truly American,” 89% of Republicans compared to 65% of Democrats believe that speaking English is important, 86% of Republicans compared to 59% of Democrats believe that sharing U.S. customs and traditions is important, 48% of Republicans compared to 25% of Democrats believe that being Christian is important, and 46% of Republicans compared to 25% of Democrats believe that having been born in the U.S is important (Connaughton, 2021). Given these differences, the aims of the present research are 2-fold. First, we sought to conceptually replicate whether American identity (i.e., superordinate identity) is related to positive intergroup attitudes between Democrats and Republicans and whether what it means to be an American differs between Democrats and Republicans. Second, we examined whether the extent to which people define what it means to be an American restrictively moderates the relationship between American Identity and intergroup attitudes.

Materials and methods

Open practices statement

All survey materials, data, and R code have been made publicly available at the Open Science Framework and can be accessed at: https://osf.io/n3r8y/?view_only=c7332bfa772741db82c50c29029612a8.

Sample and participants

Data was collected from 1,322 United States citizens over the age of 18, between 10/27/2020 and 11/11/20201. All participants were recruited from MTurk, and they received $0.50 for their participation. Thirty-seven (3%) individuals failed the attention checks, 3 (0.2%) individuals completed the study outside of the U.S., and 10 (0.8%) individuals had duplicate IP addresses. These exclusions resulted in a sample of N = 1,272 participants (56% Female, 44% Male, 0.2% Other; 59% Democrat, 41% Republican; 74% White, 9% Black or African American, 9% Asian, 2% Hispanic or Latino, 4% multiracial, and 1% other).

We found no differences between Democrats and Republicans in our sample, in terms of race/ethnicity, = 9.77, p = 0.13, sex, = 3.67, p = 0.30, education, = 13.26, p = 0.066, and age, t(537.17) = −1.88, p = 0.061. However, we found that on average, Republicans in our sample had higher income compared to Democrats t(1, 125.6) = −3.34, p < 0.001, which is representative of the general population (Pew Research Center, 2023).

Procedure

First, participants completed demographic information, which included a question asking, “Which of the following do you primarily identify as?” with the choices “Democrat” or “Republican.” As the U.S. representative democracy governmental system is dominated by two political parties, we only offered these choices to our participants (e.g., out of 100 senators, only three are not affiliated with either party; US House of Representatives Press Gallery, 2023). Second, they completed survey questions2. This survey was designed to be conditional so that each participant received questions based on their party identity. For instance, if the participant identified as a Democrat, they were asked to report their American identity, restrictive Americanism, how much they like Republicans, and how warm they perceive Republicans to be (and vice versa for participants who identified as Republicans). We included three attention check items across the study. Participants were debriefed after completing the study.

Measures

Political orientation

Political orientation was assessed with one item: “What is your political orientation?” (1 = very liberal; 7 = very conservative). This item was included as a variable check for political party (r = 0.76, p < 0.001).

American identity (α = 0.93)

The Ethnic Group Identification measure (Sidanius et al., 2007) is a 4-item scale that was adapted to measure American identity3. Items include “How strongly do you identify with other Americans?”, “How often do you think of yourself as an American?”, “How important is being an American to your identity?”, and “How close do you feel to other Americans” (1 = not at all; 7 = very).

Restrictive Americanism (α = 0.81)

Three items from Li and Brewer (2004) were used to assess the definition of what it means to be American. Participants were asked how important being a Christian, being able to speak English, and being born in the United States are to being truly American (1 = not important at all, 5 = extremely important). Higher scores on this measure indicate a more restrictive definition of what it means to be American.

Liking

Liking the other political party was assessed with one item: “How much do you like Republicans/Democrats?” (0 = not at all; 10 = very much). Democrats were asked to report their liking of Republicans (and vice versa for Republicans).

Warmth (α = 0.92)

The Stereotype Content scale was adapted to measure warmth stereotypes of outgroup members (Fiske et al., 2022). Democrats were asked to report their perceptions of the warmth of Republicans with four items (and vice versa for Republicans). Items were: “As viewed by society, how… are Republicans/Democrats? [tolerant, warm, good natured, sincere]” (1 = not at all; 5 = extremely). Higher scores indicated higher perceived warmth of the outgroup members.

Analysis plan

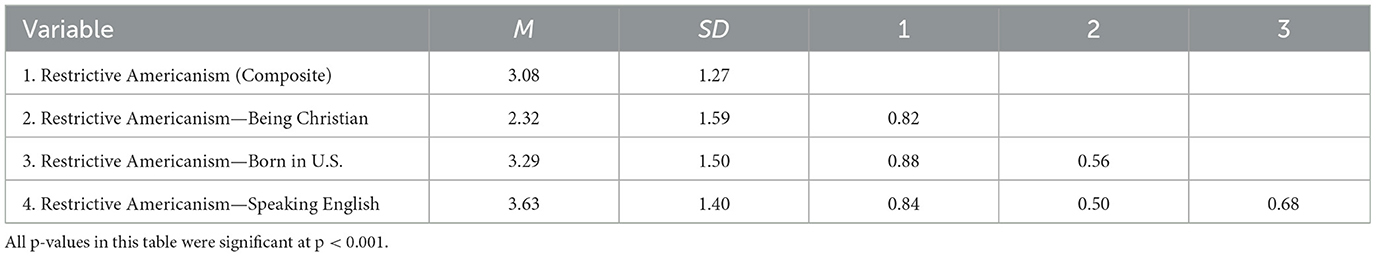

This observational study examined whether the definition of what it means to be American moderates the relationship between identifying as American and intergroup attitudes (liking and perceived warmth) between Democrats and Republicans. Based on preliminary exploratory correlational analyses, we planned to examine the associations between American identity and intergroup attitudes: liking and warmth, separately controlling for political party (Republican = 1, and Democrat = 0) and controlling for political orientation. Then, we examined whether restrictive Americanism moderated these relationships. We took composite scores of all variables that were assessed with multiple items by taking the average of the items, and all continuous variables were standardized. Since the restrictive Americanism items had high inter-item correlations (rs ≥ 0.5, ps < 0.001; see Table 1) and internal consistency (α = 0.81), we took the average of these items to create a composite score (higher values corresponding to those who believe that being Christian, born in the U.S., and speaking English were integral to being American). Because we wanted to test if restrictive Americanism moderates the relationship between American identity and intergroup attitudes regardless of participants' political party affiliation (i.e., Democrat or Republican) and political orientation, we also included political party and political orientation as covariates in separate regression analyses4.

Results

Descriptive statistics

On average, participants found speaking English most important to being American (see Table 1; M = 3.63, SD = 1.40), followed by being born in the U.S. (M = 3.29, SD = 1.50), and being Christian (M = 2.32, SD = 1.59). Compared to Democrats, Republicans viewed speaking English [t(1, 259.9) = −14.58, p < 0.001], being born in the U.S. [t(1, 216.9) = −13.12, p < 0.001], and being Christian [t(1, 007.8) = −14.50, p < 0.001] more important to being American.

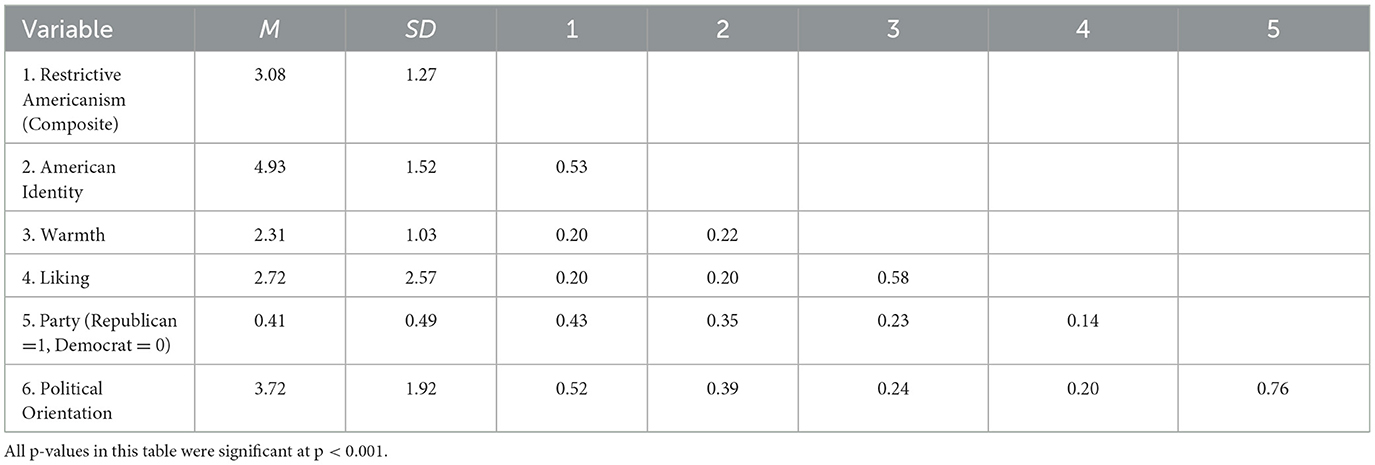

Our main outcome variables (i.e., outgroup liking and warmth) were correlated with each other (r = 0.58, p < 0.001; see Table 2). American identity was positively related to liking (r = 0.20, p < 0.001) and warmth (r = 0.22, p < 0.001). Compared to Democrats, Republicans were more likely to score higher in restrictive Americanism [i.e., a more restrictive definition of what being “truly” American means; t(1, 200) = −17.22, p < 0.001] and American identity [t(1, 235.5) = −14.01, p < 0.001]. Furthermore, those who had a more restrictive view of what it means to be “truly” American were higher in American identity (r = 0.53, p < 0.001).

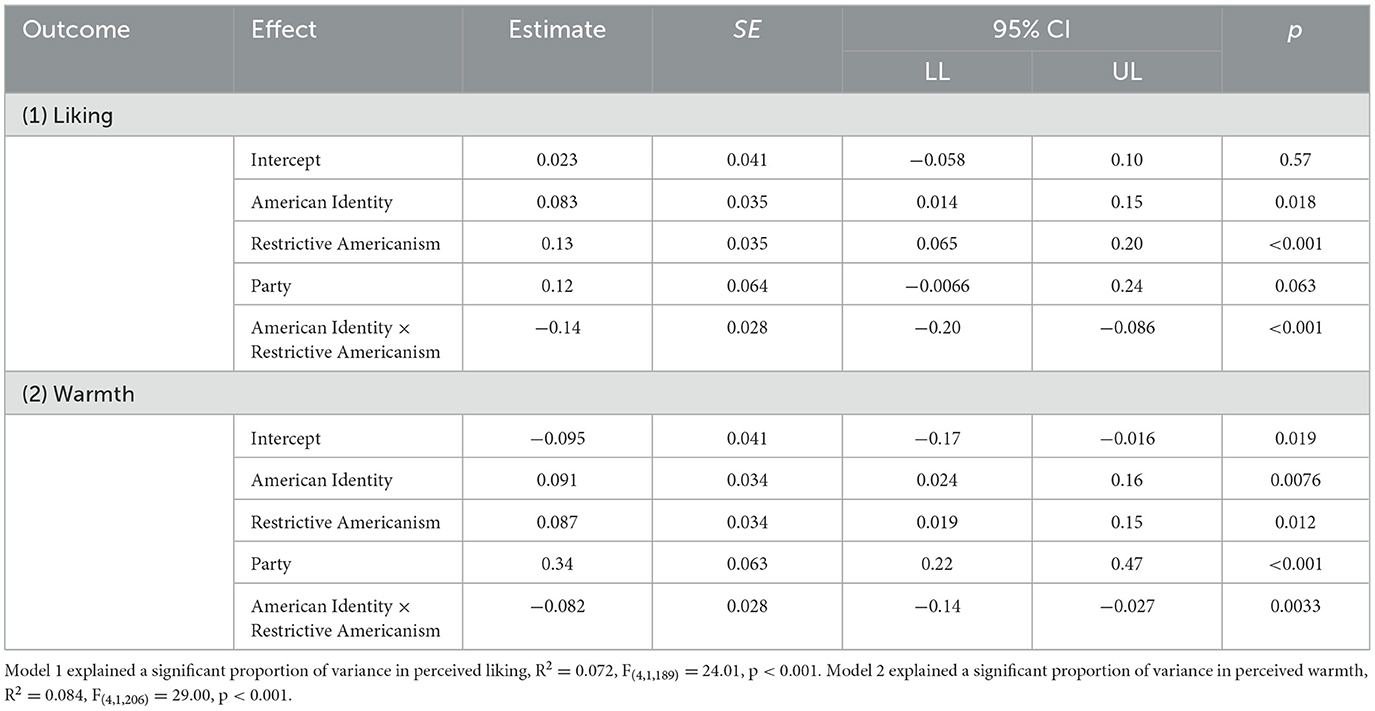

American identity and intergroup attitudes

First, we found that American identity was positively related to outgroup liking (β = 0.083, p = 0.018) and perceived outgroup warmth (β = 0.091, p = 0.0076) when we controlled for restrictive Americanism, the interaction between American identity and restrictive Americanism, and party5 (i.e., Democrat or Republican; see Table 2). This relationship was moderated by restrictive Americanism for liking (β = −0.14, p < 0.001) and warmth (β = −0.082, p = 0.0033). More specifically, higher restrictive Americanism (in terms of being a Christian, being born in the U.S., and speaking English), had a negative effect on how American identity was related to liking members of the opposing party and perceiving them as warmer, when controlling for party. Moreover, follow up regression analyses with three-way interactions showed that the size of this interaction effect did not differ across Democrat and Republican participants. Three-way interaction terms between American identity, restrictive Americanism, and party in separately predicting outgroup liking and warmth were not significant (βliking = −0.091, p = 0.22, βwarmth = −0.058, p = 0.40)6.

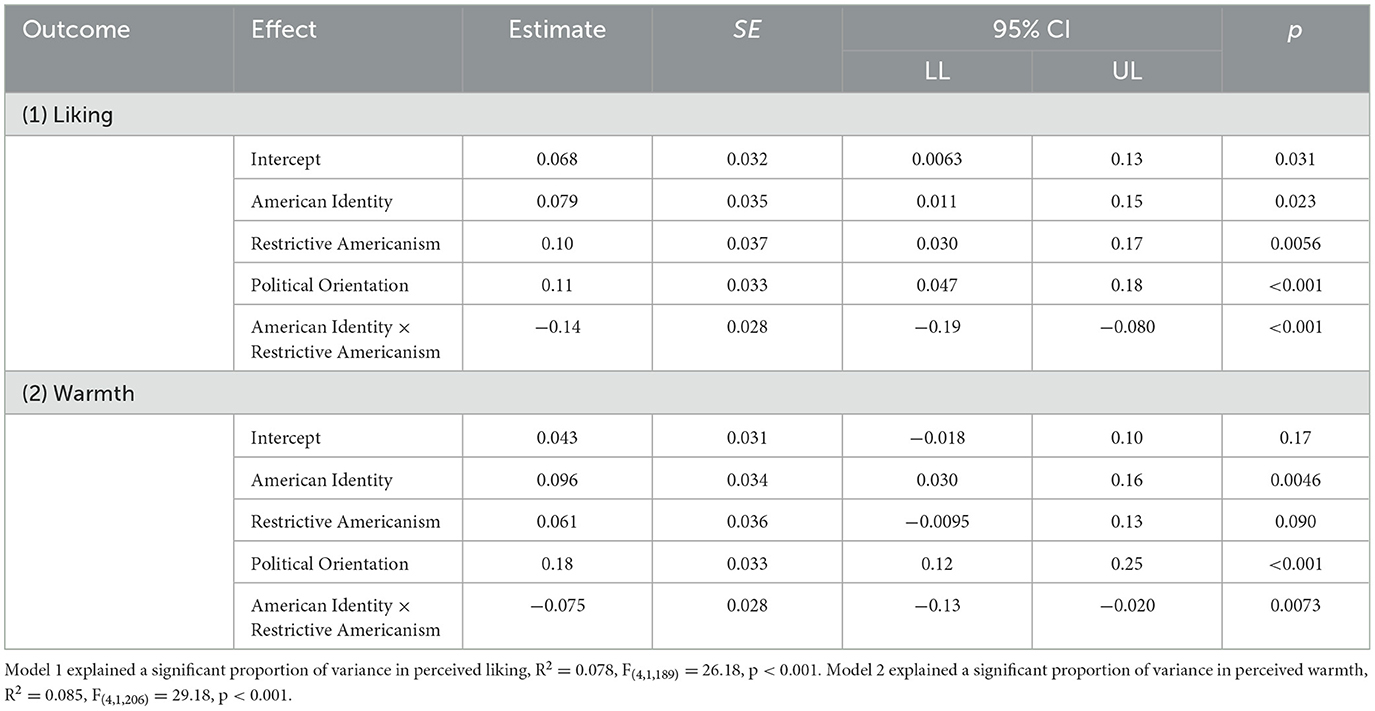

We ran the same analyses, controlling for political orientation instead of party, and we found similar results7. American identity was positively related to outgroup liking (β = 0.079, p = 0.023) and perceived outgroup warmth (β = 0.096, p = 0.0046) when we controlled for restrictive Americanism, the interaction between American identity and restrictive Americanism, and political orientation (see Table 3). This relationship was moderated by restrictive Americanism for liking (β = −0.14, p < 0.001) and warmth (β = −0.075, p = 0.0073). Higher restrictive Americanism had a negative effect on how American identity was related to liking members of the opposing party and perceiving them as warmer, controlling for participants' political orientation. Moreover, follow up regression analyses with three-way interactions showed that the interaction between American identity and restrictive Americanism did not depend on political orientation when it comes to liking (βliking = −0.055, p = 0.065) but it did for warmth (βwarmth = −0.095, p = 0.0014)8.

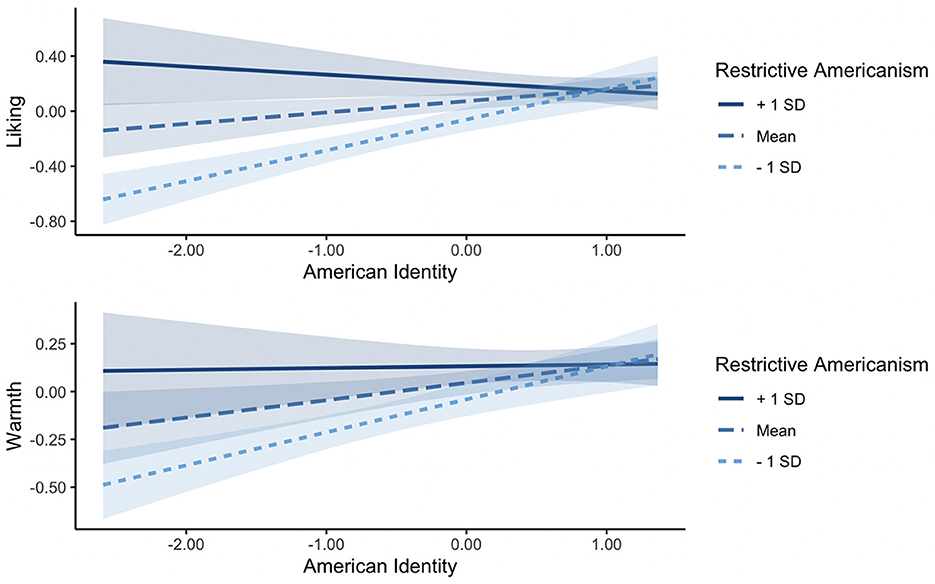

To disentangle the interactions between American identity and restrictive Americanism (controlling for party), we used simple slopes analysis, using the interactions package in R (v1. 1.5; Long, 2019; see Figure 1). We specifically looked at restrictive Americanism at three levels: low (mean – 1 SD), average, and high (mean + 1 SD). We found that for participants who were low in terms of restrictive Americanism, American identity positively predicted liking (β = 0.22, p < 0.001; see Figure 1) and warmth (β = 0.17, p < 0.001). Similarly, at mean level restrictive Americanism, American identity positively predicted liking (β = 0.082, p = 0.019) and warmth (β = 0.091, p = 0.0076). However, for participants who were high in restrictive Americanism, these effects did not hold for either liking (β = −0.059, p = 0.24) or warmth (β = 0.0093, p = 0.85). In other words, for participants who had a less restrictive conceptualization of “American,” their American identity was positively related to their liking and warmth toward their political outgroup. For participants who had a more restrictive conceptualization of “American,” their American identity was not related to liking and warmth, regardless of which party they identified with. To disentangle the interactions between American identity and restrictive Americanism when controlling for political orientation, we repeated the same analyses and found similar results (see Supplementary material).

Figure 1. Simple slopes predicting liking and warmth at different levels of restrictive Americanism, controlling for party. The shaded area around slopes represents 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

This research examined how identity conceptualizations influence common identity processes and outgroup attitudes, specifically in the context of American national identity. We first replicated previous findings showing that a common national identity is related to more positive attitudes between Democrats and Republicans (Levendusky, 2018). We also demonstrated that Democrats and Republicans define what it means to be an American differently on average. Compared to Democrats, Republicans tend to find being Christian, being born in the U.S., and speaking English to be more important to being truly American (Connaughton, 2021). Additionally, those who viewed being American in more restrictive terms were higher in American identity. This finding aligns with previous work suggesting that strong identifiers of a national group tend to set clearer boundaries around this identity (Theiss-Morse, 2009). Most importantly, how people defined what it means to be an American influenced the relationship between American identity and attitudes toward members of an opposing political party. Those who defined “American” less restrictively showed more positive attitudes toward members of the other party as American identity increased. This interaction stayed significant when we separately controlled for participant party and political orientation. Taken together, these findings show that Democrats and Republicans have different conceptualizations of what it means to be American on average, and these differences might inform future research invoking national identity as a means to reduce negative attitudes between partisans.

Moving beyond a specific national identity, these observational findings suggest a potential explanation as to why increased common ingroup identity might not always be linked to improved intergroup attitudes. If common identities carry restrictive conceptualizations, a higher common identity may not be linked to inclusion. Central to common ingroup identity lies the idea that group boundaries can be flexible and subjective. As such, understanding what common identities mean to individuals (and social groups) is integral for examining and creating common identities that can decrease negative intergroup attitudes.

Future directions and limitations

This work is the first to document the moderating role of conceptualizations of national American identity on relationships between American identity and intergroup attitudes. It is important to note that we only examined a subset of facets related to being American (i.e., Christian, born in U.S., speaks English). While we chose these characteristics based on past work (Li and Brewer, 2004), conceptualizations of American identity extend to many other facets. For instance, people might associate being an American with a commitment to certain values, such as democracy, equality, liberalism, multiculturalism, liberty, and freedom (Gleason, 1980; Gallup, 2003; Theiss-Morse, 2009). Future research would benefit from understanding what these characteristics are, especially for attributes that may be endorsed by both Democrats and Republicans, as they may help maximize the utility of the Common Ingroup Identity Model in improving intergroup relations.

Besides expanding on the multi-faceted conceptualization of what an American identity means to Democrats and Republicans, future work would also benefit from taking an intersectional approach to understanding the role of concept equivalence in common identity processes. That is, certain aspects of restrictive Americanism, or an exclusive conceptualization of what it means to be an American may resonate more with certain groups, especially subgroups of political parties such as populists. Being born in the U.S. might not be as important to being American for immigrants. Additionally, these views might differ across generations. For instance, younger Americans (18–29 years old) viewed openness to people from all over the world as more ‘essential to who we are as a nation' compared to older Americans (65+ years; Hartig, 2018). Moreover, speaking English might not be as important to being American for Hispanic or Latino Americans, given 68% of Hispanic or Latino Americans speak Spanish at home (Krogstad et al., 2015). Additionally, it is necessary to examine how a dual identity approach, where partisans endorse both their party identities and national identities, would influence relations between partisans. Since the focus on a common identity without dual identity can increase identity threat (Crisp et al., 2006), a common national identity that may not align with one's party identity may further increase polarization.

In considering the conceptualization of what it means to be American, it is also crucial to understand how important these characteristics are to individuals. Since our study did not ask participants about their attitudes toward these identity facets, we cannot distinguish those who value Christianity, nativism, and speaking English from those who do not. In other words, someone might view Christianity to be important to being American, without viewing Christianity to be important to their own identity. Furthermore, the Ingroup Projection Model suggests that group members may project characteristics of their ingroup to a broader identity, viewing their group as prototypical of this identity (Wenzel et al., 2008). Asking respondents to rate how important a characteristic is to their own identity, alongside assessing how important it is to being American is essential in understanding this phenomenon. Future directions include exploring this additional dimension to parse concept equivalence from subjective perceptions of the components underlying American identity.

The work presented herein shows that there was a moderate positive relationship between American identity and restrictive Americanism (r = 0.53, p < 0.001), indicating that those who tend to identify more strongly as American were also more likely to define this identity restrictively. Moreover, participants who were lower in restrictive Americanism and American identity also reported more negative attitudes toward members of the other party (see Figure 1). A combination of low American identity and low restrictive Americanism might represent a group of people who not only score low on American identity, but intentionally oppose or dislike American identity, since it entails values that they do not support. This may be linked to more negative attitudes toward the opposing party, if restrictive Americanism is linked with perceptions of the other parties' ideologies. In our sample, Democrats scored lower than Republicans in American identity, restrictive Americanism, and expressed more negative attitudes toward outgroup members (see Table 4). Since American identity is less clearly defined among Democrats, and Republican leaders often use restrictive definitions of American identity to gain support (Mellow, 2020; Hanson et al., 2023), Democrats may perceive American identity to be akin to Republican identity. Besides further understanding the sociodemographic and psychological characteristics of individuals who are low in American identity and restrictive Americanism, a notable advance would be to differentiate between how people personally define what it means to be American and how they think society and members of the opposing party define what it means to be American.

This data was collected as part of a larger project related to timing effects around presidential elections, and additional analyses confirmed that results hold when controlling for timing effects (i.e., pre-, during, and post-election). Even though the broader data collection period of this study was still around the 2020 election, our findings replicated previous work that was conducted during other time points (Levendusky, 2018; Connaughton, 2021). Regardless, it is still possible that our data collection around the Presidential election coincided with increased political tensions, and that the salience of restrictive Americanism, American identity, and party identity were higher at this time. Additionally, it is important to note that while differences between the composition of Republicans and Democrats in our sample were not significant in terms of race/ethnicity, sex, education, and age, the composition of Republicans at the national level tends to be more White, less formally educated, and older compared to Democrats (Pew Research Center, 2023). As such, future work would benefit from examining these associations during non-election years, as well as in more representative samples.

In terms of measurement, even though we used multiple items to assess warmth, we used a single-item measure to assess liking. While multiple-item measures tend to exhibit higher predictive validity compared to single-item measures (Diamantopoulos et al., 2012), intergroup relations researchers often use single-item feeling thermometers as main outcome measures, including those assessing outgroup liking (e.g., Crisp et al., 2009; Seger et al., 2014; Jacoby-Senghor et al., 2019). Indeed, single-item measures across research domains exhibit comparable validity and reliability to their multi-item equivalents (Bergkvist and Rossiter, 2007; Ahmad et al., 2014; Ang and Eisend, 2018; Allen et al., 2022). Feeling thermometers have also been successful in measuring sentiments toward members of other parties, being related to preferences for social distance and discrimination in economic games (Iyengar et al., 2019; Gidron et al., 2023). Additionally, while many studies focusing on intergroup relations use liking and warmth interchangeably (e.g., Fiske et al., 1999; Dasgupta and Greenwald, 2001; Inbar et al., 2012), we focused on liking and warmth separately to get a more nuanced understanding of inter-partisan relations, as attitudes can be complex and must be measured accordingly (Krosnick et al., 2005).

When it comes to generalizability, our findings are limited to a single, correlational study in the U.S. political context. Researchers must examine whether these relationships are causal by experimentally manipulating the strength and conceptualizations of a common national identity. In doing so, researchers must explore how priming different common national identities might affect participants (e.g., based on party affiliation, immigration status, and race/ethnicity). Moreover, while we specifically focused on the U.S. political context, political polarization is a global issue (Carothers and O'Donahue, 2019). To assess the generalizability of our findings, examining whether the issue of conceptual equivalence emerges in other political contexts (e.g., other countries and other parties) is paramount, especially in coalition-based democratic governments around the world.

Finally, while the effects we found are consistent across both measures of intergroup relations we used, interaction effects were quite small (Funder and Ozer, 2019). Small effects can be beneficial to advancing theory and application (Prentice and Miller, 1992; Rosenthal et al., 2000). However, they may also indicate limited applicability of the studied phenomenon to real-life outcomes. This limitation highlights the importance of conducting future work to understand the possible consequences of a common identity in improving inter-partisan attitudes.

Conclusion

This work is the first to document the moderating role of conceptualizations of what it means to be American on the link between American identity and intergroup attitudes. We explicated and extended past work on national identity by demonstrating the importance of conceptual equivalence—when partisans talk about being American, are they referring to the same thing? Our findings suggest that Democrats and Republicans define what it means to be American differently. Furthermore, for those who define “American” restrictively, the relationship between a common American identity and attitudes toward members of the opposing party become weaker, regardless of their party or political orientation. As affective and attitudinal political polarization deeply influences the social climate of the U.S., it is critical for researchers to understand the nuances of how identities are conceptualized in an effort to improve American intergroup relations.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://osf.io/n3r8y/?view_only=c7332bfa772741db82c50c29029612a8.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of Rochester Research Subjects Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

ST: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JG: Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. JJ: Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsps.2024.1338515/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Data was collected at three time points, before (N = 437), during (N = 438), and after (N = 447) the 2020 U.S. presidential election (10/27/2020 – 11/3/2020, 11/4/2020 – 11/7/2020, 11/8/2020 – 11/11/2020). Data were collapsed into one dataset as time effects were not included in the scope of this paper.

2. ^This study was part of a larger study including other variables that are not examined in this paper. The full study materials can be accessed via: https://osf.io/n3r8y/?view_only=c7332bfa772741db82c50c29029612a8.

3. ^Ethnicity is a broad construct, often used to refer to culture, national and geographic origin, and descent (Fenton, 2010). As “American” is a broad term indicating the social identity of people living in a large region, we adapted the ethnic group identity scale by Sidanius et al. (2007) to assess this broad group identity.

4. ^The significance of our regression coefficients (at p < 0.05) did not differ when we did not control for political party or political orientation.

5. ^When controlling for wave of data collection, interactions remained significant at p < 0.01. We also separately controlled for party identity (i.e., the strength of identification with one's party) and results remained significant at p < 0.05. Analyses can be found in Supplementary Tables 1, 3.

6. ^These three-way interactions are underpowered and may not replicate. These analyses can be found in Supplementary Table 5.

7. ^Similar to analyses with party, when controlling for wave of data collection, interactions remained significant at p < 0.01. Interactions also remained significant at p < 0.05 when controlling for party identity. These analyses can be found in Supplementary Tables 2, 4.

8. ^These three-way interactions are underpowered and may not replicate. These analyses can be found in Supplementary Table 6.

References

Abrams, D., and Hogg, M. A. (1988). Comments on the motivational status of self-esteem in social identity and intergroup discrimination. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 18, 317–334. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2420180403

Ahmad, F., Jhajj, A. K., Stewart, D. E., Burghardt, M., and Bierman, A. S. (2014). Single item measures of self-rated mental health: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 14, 1–11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-398

Allen, M. S., Iliescu, D., and Greiff, S. (2022). Single item measures in psychological science. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2022:a000699. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759/a000699

Ang, L., and Eisend, M. (2018). Single versus multiple measurement of attitudes: a meta-analysis of advertising studies validates the single-item measure approach. J. Advert. Res. 58, 218–227. doi: 10.2501/JAR-2017-001

Bavel, J. J. V., Baicker, K., Boggio, P. S., Capraro, V., Cichocka, A., Cikara, M., et al. (2020). Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat. Hum. Behav. 4, 460–471. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z

Bergkvist, L., and Rossiter, J. R. (2007). The predictive validity of multiple-item versus single-item measures of the same constructs. J. Market. Res. 44, 175–184. doi: 10.1509/jmkr.44.2.175

Berry, J. W. (2002). Cross-Cultural Psychology: Research and Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brewer, M. B. (2011). “Identity and conflict,” in Intergroup Conflicts and Their Resolution: A Social Psychological Perspective, ed. D. Bar-Tal (East Sussex: Psychology Press), 125–143.

Budiman, A. (2020). Key Findings About U.S. Immigrants. Pew Research Center. Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2020/08/20/key-findings-about-u-s-immigrants/ (accessed July 8, 2024).

Carothers, T., and O'Donohue, A., (eds.). (2019). Democracies Divided: The Global Challenge of Political Polarization. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Cehajić-Clancy, S., Janković, A., Opačin, N., and Bilewicz, M. (2023). The process of becoming 'we'in an intergroup conflict context: how enhancing intergroup moral similarities leads to common-ingroup identity. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2023:12632. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12632

Cohen, G. L. (2003). Party over policy: the dominating impact of group influence on political beliefs. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 85:808. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.5.808

Connaughton, A. (2021). In Both Parties, Fewer Now Say Being Christian or Being Born in U.S. Is Important to Being “Truly American”. Pew Research Center. Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2021/05/25/in-both-parties-fewer-now-say-being-christian-or-being-born-in-u-s-is-important-to-being-truly-american/ (accessed July 8, 2024).

Crisp, R. J., Hutter, R. R., and Young, B. (2009). When mere exposure leads to less liking: the incremental threat effect in intergroup contexts. Br. J. Psychol. 100, 133–149. doi: 10.1348/000712608X318635

Crisp, R. J., Stone, C. H., and Hall, N. R. (2006). Recategorization and subgroup identification: predicting and preventing threats from common ingroups. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bullet. 32, 230–243. doi: 10.1177/0146167205280908

Dasgupta, N., and Greenwald, A. G. (2001). On the malleability of automatic attitudes: combating automatic prejudice with images of admired and disliked individuals. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 81:800. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.81.5.800

Delehanty, J., Edgell, P., and Stewart, E. (2019). Christian America? Secularized evangelical discourse and the boundaries of national belonging. Soc. Forces 97, 1283–1306. doi: 10.1093/sf/soy080

Diamantopoulos, A., Sarstedt, M., Fuchs, C., Wilczynski, P., and Kaiser, S. (2012). Guidelines for choosing between multi-item and single-item scales for construct measurement: a predictive validity perspective. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 40, 434–449. doi: 10.1007/s11747-011-0300-3

Dias, N., and Lelkes, Y. (2022). The nature of affective polarization: disentangling policy disagreement from partisan identity. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 66, 775–790. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12628

Dietz, B., van Knippenberg, D., Hirst, G., and Restubog, S. L. D. (2015). Outperforming whom? A multilevel study of performance-prove goal orientation, performance, and the moderating role of shared team identification. J. Appl. Psychol. 100:1811. doi: 10.1037/a0038888

Dovidio, J. F., Gaertner, S. L., Isen, A. M., and Lowrance, R. (1995). Group representations and intergroup bias: positive affect, similarity, and group size. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bullet. 21, 856–865. doi: 10.1177/0146167295218009

Dovidio, J. F., Gaertner, S. L., and Kafati, G. (2000). “Group identity and intergroup relations. The common in-group identity model,” in Advances in Group Processes (Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited), 1–35.

Dovidio, J. F., Gaertner, S. L., and Saguy, T. (2008). Another view of “we”: majority and minority group perspectives on a common ingroup identity. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 18, 296–330. doi: 10.1080/10463280701726132

Dovidio, J. F., Gaertner, S. L., Ufkes, E. G., Saguy, T., and Pearson, A. R. (2016). Included but invisible? Subtle bias, common identity, and the darker side of “we”. Soc. Iss. Pol. Rev. 10, 6–46. doi: 10.1111/sipr.12017

Druckman, J. N., Klar, S., Krupnikov, Y., Levendusky, M., and Ryan, J. B. (2021). Affective polarization, local contexts and public opinion in America. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5, 28–38. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-01012-5

Egan, P. J., and Mullin, M. (2017). Climate change: US public opinion. Ann. Rev. Polit. Sci. 20, 209–227. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-051215-022857

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J., Glick, P., and Xu, J. (2022). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 82, 878–902. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.878

Fiske, S. T., Xu, J., Cuddy, A. C., and Glick, P. (1999). (Dis) respecting versus (dis) liking: status and interdependence predict ambivalent stereotypes of competence and warmth. J. Soc. Iss. 55, 473–489. doi: 10.1111/0022-4537.00128

Fuertes, J. N., Gottdiener, W. H., Martin, H., Gilbert, T. C., and Giles, H. (2012). A meta-analysis of the effects of speakers' accents on interpersonal evaluations. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 42, 120–133. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.862

Funder, D. C., and Ozer, D. J. (2019). Evaluating effect size in psychological research: sense and nonsense. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 2, 156–168. doi: 10.1177/2515245919847202

Gaertner, S. L., Dovidio, J. F., Anastasio, P. A., Bachman, B. A., and Rust, M. C. (1993). The common ingroup identity model: recategorization and the reduction of intergroup bias. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 4, 1–26. doi: 10.1080/14792779343000004

Gallup, G. H. (2003). What Being American Means to Today's Youth. Gallup. Available online at: https://news.gallup.com/poll/9712/what-being-american-means-todays-youth.aspx (accessed July 8, 2024).

Gallup, G. H. (2023). Where Do Americans Stand on Abortion? Gallup. Available online at: https://news.gallup.com/poll/321143/americans-stand-abortion.aspx (accessed July 8, 2024).

Gidron, N., Adams, J., and Horne, W. (2023). Who dislikes whom? Affective polarization between pairs of parties in western democracies. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 53, 997–1015. doi: 10.1017/S0007123422000394

Gleason, P. (1980). “American identity and americanization,” in Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups, ed. S. Thernstrom (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press), 31–32, 56–57.

Gordils, J., Elliot, A. J., Toprakkiran, S., and Jamieson, J. P. (2021). The effects of COVID-19 on perceived intergroup competition and negative intergroup outcomes. J. Soc. Psychol. 161, 419–434. doi: 10.1080/00224545.2021.1918617

Gordils, J., Jamieson, J. P., and Elliot, A. J. (2023). The effect of Black-White income inequality on perceived interracial psychological outcomes via perceived interracial competition. J. Exp. Psychol. 2023:1418. doi: 10.1037/xge0001418

Hanson, K., O'Dwyer, E., and Vall?e-Tourangeau, F. (2023). The democrats' national identity dilemma: an analysis of US democratic rhetoric in the 2020 presidential primary campaign. OSF. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/qh46u

Harachi, T. W., Choi, Y., Abbott, R. D., Catalano, R. F., and Bliesner, S. L. (2006). Examining equivalence of concepts and measures in diverse samples. Prev. Sci. 7, 359–368. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0039-0

Hartig, H. (2018). Most Americans View Openness to Foreigners as “Essential to Who We Are as a Nation”. Pew Research Center. Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2018/10/09/most-americans-view-openness-to-foreigners-as-essential-to-who-we-are-as-a-nation/ (accessed July 8, 2024).

Hartman, R., Blakey, W., Womick, J., Bail, C., Finkel, E. J., Han, H., et al. (2022). Interventions to reduce partisan animosity. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6, 1194–1205. doi: 10.1038/s41562-022-01442-3

Hindriks, P., Verkuyten, M., and Coenders, M. (2014). Interminority attitudes: the roles of ethnic and national identification, contact, and multiculturalism. Soc. Psychol. Quart. 77, 54–74. doi: 10.1177/0190272513511469

Hinsz, V. B., and Jackson, J. W. (2022). The relevance of group dynamics for understanding the US Capitol insurrection. Gr. Dyn. 26:288. doi: 10.1037/gdn0000191

Inbar, Y., Pizarro, D. A., and Bloom, P. (2012). Disgusting smells cause decreased liking of gay men. Emotion 12:23. doi: 10.1037/a0023984

Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N., and Westwood, S. J. (2019). The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Ann. Rev. Polit. Sci. 22, 129–146. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-051117-073034

Jacoby-Senghor, D. S., Sinclair, S., Smith, C. T., and Skorinko, J. L. (2019). Implicit bias predicts liking of ingroup members who are comfortable with intergroup interaction. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bullet. 45, 603–615. doi: 10.1177/0146167218793136

Jones, D. R. (2001). Party polarization and legislative gridlock. Polit. Res. Quart. 54, 125–141. doi: 10.1177/106591290105400107

Kalmoe, N. P., and Mason, L. (2022). A holistic view of conditional American support for political violence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 119:e2207237119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2207237119

Karni, A. (2022). Senate Vote on Abortion Rights—How a Bill to Protect Abortion Access Failed in the Senate. The New York Times. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/live/2022/05/11/us/abortion-roe-v-wade-senate-vote (accessed July 8, 2024).

Kingzette, J., Druckman, J. N., Klar, S., Krupnikov, Y., Levendusky, M., and Ryan, J. B. (2021). How affective polarization undermines support for democratic norms. Publ. Opin. Quart. 85, 663–677. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfab029

Kleinfeld, R. (2022). The Rise in Political Violence in the United States and Damage to Our democracy. Testimony before the Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Available online at: https://carnegieendowment.~org/2022/03/31/rise-in-political-violence-in-united-states-and-damage-to-our-democracy-pub-87584 (accessed July 8, 2024).

Krogstad, J. M., Stepler, R., and Lopez, M. H. (2015). English Proficiency on the Rise Among Latinos. Pew Research Center. Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2015/05/12/english-proficiency-on-the-rise-among-latinos/ (accessed July 8, 2024).

Krosnick, J. A., Judd, C. M., and Wittenbrink, B. (2005). Attitude Measurement. Handbook of Attitudes and Attitude Change (Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum), 21–76.

Levendusky, M. S. (2018). Americans, not partisans: can priming American national identity reduce affective polarization? J. Polit. 80, 59–70. doi: 10.1086/693987

Li, Q., and Brewer, M. B. (2004). What does it mean to be an American? Patriotism, nationalism, and American identity after 9/11. Polit. Psychol. 25, 727–739. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2004.00395.x

Long, J. A. (2019). Interactions: Comprehensive, User-Friendly Toolkit for Probing Interactions. R package version 1.1.0. Available online at: https://cran.r-project.org/package=interactions

McCoy, J., Rahman, T., and Somer, M. (2018). Polarization and the global crisis of democracy: common patterns, dynamics, and pernicious consequences for democratic polities. Am. Behav. Sci. 62, 16–42. doi: 10.1177/0002764218759576

Ogan, C., Willnat, L., Pennington, R., and Bashir, M. (2014). The rise of anti-Muslim prejudice: media and Islamophobia in Europe and the United States. Int. Commun. Gazette 76, 27–46. doi: 10.1177/1748048513504048

Penner, L. A., Gaertner, S., Dovidio, J. F., Hagiwara, N., Porcerelli, J., Markova, T., et al. (2013). A social psychological approach to improving the outcomes of racially discordant medical interactions. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 28, 1143–1149. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2339-y

Pew Research Center (2014). Political Polarization in the American Public. Pew Research Center. Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2014/06/12/political-polarization-in-the-american-public/ (accessed July 8, 2024).

Pew Research Center (2019). Partisan Antipathy: More Intense, More Personal. Pew Research Center. Available online at: www.pewresearch.org/politics/2019/10/10/partisan-antipathy-more-intense-more-personal/

Pew Research Center (2023). Demographic Profiles of Republican and Democratic Voters. Pew Research Center. Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2023/07/12/demographic-profiles-of-republican-and-democratic-voters/ (accessed July 8, 2024).

Piazza, J. A. (2023). Political polarization and political violence. Secur. Stud. 32, 476–504. doi: 10.1080/09636412.2023.2225780

Prentice, D. A., and Miller, D. T. (1992). When small effects are impressive. Psychol. Bullet. 112, 160–164. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.160

Riek, B. M., Mania, E. W., Gaertner, S. L., McDonald, S. A., and Lamoreaux, M. J. (2010). Does a common ingroup identity reduce intergroup threat? Gr. Processes Intergr. Relat. 13, 403–423. doi: 10.1177/1368430209346701

Rosenthal, R., Rosnow, R. L., and Rubin, D. B. (2000). Contrasts and Effect Sizes in Behavioral Research: A Correlational Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Saad, L. (2023). Americans Still Value Immigration, but Have Concerns. Gallup. Available online at: https://news.gallup.com/poll/508520/americans-value-immigration-concerns.aspx#:~:text=During%202018%2D2021%2C%20there%20was,%20immigration%2C%20with%2031%25%20of (accessed July 8, 2024).

Seger, C. R., Smith, E. R., Percy, E. J., and Conrey, F. R. (2014). Reach out and reduce prejudice: the impact of interpersonal touch on intergroup liking. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 36, 51–58. doi: 10.1080/01973533.2013.856786

Sidanius, J., Haley, H., Molina, L., and Pratto, F. (2007). Vladimir's choice and the distribution of social resources: a group dominance perspective. Gr. Process. Intergr. Relat. 10, 257–265. doi: 10.1177/1368430207074732

Smith, T. W., and Son, J. (2013). Trends in Public Attitudes Toward Abortion. National Opinion Research Center. Available online at: https://www.norc.org/content/dam/norc-org/pdfs/Trends%20in%20Attitudes%20About%20Abortion_Final.pdf

Stephan, W. G., and Stephan, C. W. (1985). Intergroup anxiety. J. Soc. Iss. 41, 157–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1985.tb01134.x

Stokes, B. (2017). What It Takes to Truly Be “One of Us”. Pew Research. Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2017/02/01/what-it-takes-to-truly-be-one-of-us/ (accessed July 8, 2024).

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. C. (2004). “The social identity theory of intergroup behavior,” in Political Psychology: Key Readings, eds. J. T. Jost and J. Sidanius (East Sussex: Psychology Press), 276–293. doi: 10.4324/9780203505984-16

Theiss-Morse, E. (2009). Who Counts as an American? The Boundaries of National Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Toprakkiran, S., and Gordils, J. (2021). The onset of COVID-19, common identity, and intergroup prejudice. J. Soc. Psychol. 161, 435–451. doi: 10.1080/00224545.2021.1918620

Trimble, J. E. (2007). Prolegomena for the connotation of construct use in the measurement of ethnic and racial identity. J. Counsel. Psychol. 54:247. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.247

Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., and Wetherell, M. S. (1987). Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory. Oxford: Blackwell.

US House of Representatives Press Gallery (2023). Party Breakdown-−118th Congress House Lineup. Available online at: https://pressgallery.house.gov/member-data/party-breakdown (accessed July 8, 2024).

Van Bavel, J. J., and Cunningham, W. A. (2010). A social neuroscience approach to self and social categorisation: a new look at an old issue. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 21, 237–284. doi: 10.1080/10463283.2010.543314

Vezzali, L., Stathi, S., Crisp, R. J., Giovannini, D., Capozza, D., and Gaertner, S. L. (2015). Imagined intergroup contact and common ingroup identity: an integrative approach. Soc. Psychol. 46:265. doi: 10.1027/1864-9335/a000242

Wenzel, M., Mummendey, A., and Waldzus, S. (2008). Superordinate identities and intergroup conflict: the ingroup projection model. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 18, 331–372. doi: 10.1080/10463280701728302

Wilder, D. A., and Allen, V. L. (1978). Group membership and preference for information about others. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bullet. 4, 106–110. doi: 10.1177/014616727800400122

Keywords: common identity, political parties, attitudes, intergroup relations, partisanship

Citation: Toprakkiran S, Gordils J and Jamieson JP (2024) Can Democrats and Republicans like each other? Depends on how you define “American”. Front. Soc. Psychol. 2:1338515. doi: 10.3389/frsps.2024.1338515

Received: 14 November 2023; Accepted: 24 June 2024;

Published: 23 July 2024.

Edited by:

Richard P. Eibach, University of Waterloo, CanadaReviewed by:

Matthew Hibbing, University of California, Merced, United StatesPeter Ditto, University of California, Irvine, United States

Copyright © 2024 Toprakkiran, Gordils and Jamieson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Selin Toprakkiran, c2VsaW4udEBydXRnZXJzLmVkdQ==

Selin Toprakkiran

Selin Toprakkiran Jonathan Gordils

Jonathan Gordils Jeremy P. Jamieson

Jeremy P. Jamieson