- Department of Psychology, University of Limerick, Limerick, Ireland

There were 96,338 Personal Public Service Numbers (PPSNs) given to people from Ukraine who arrived in Ireland under the Temporary Protection Directive (TPD) before October 2023. From the end of 2022 into 2023, there was also a rapid rise of far-right anti-refugee rhetoric in Ireland. We analysed how TPD policy, the Irish political discourse around it and its implementation through national institutions and local communities affected TPD beneficiaries and other groups in Ireland. This study used a combination of qualitative analysis of a governmental debate on the housing needs of TPD beneficiaries and ethnographic observations gathered while the authors worked to support the needs of TPD beneficiaries. We provide an explanation of how the TPD implementation in Ireland resulted in the social exclusion of its beneficiaries despite aiming for streamlined integration. In addition, the shortcomings in the TPD implementation had negative effects on different groups within Irish society. We use the 3N model—Narratives, Networks, and Needs to explain how the data and trends that we documented at different levels of analysis—national, intergroup and intragroup, and individual—were interconnected. This paper is focused on the first of the three studies in the ongoing research project and primarily addresses the Narratives (i.e., policy and its implementation, political discourse) while connecting them with some observed social inclusion/exclusion outcomes on the Networks and Needs dimensions. We explain how political Narratives influenced TPD implementation and the different actors involved in this process: public service providers, the general public, and TPD beneficiaries in Ireland. The uncoordinated implementation of accommodation provision led to serious disruptions of TPD beneficiaries' Networks. This hindered individuals' access to services which resulted in individual Needs remaining unmet. We also documented how racialised elements underlying the EU TPD contributed to exclusionary mechanisms within the TPD implementation in Ireland and how that created a double standard in service provision.

1 Introduction

The European Union (EU) Temporary Protection Directive (TPD) was activated on the 4th of March 2022 to provide swift aid and temporary protection for individuals fleeing the Russian invasion of Ukraine (European Parliament and Council, 2022).

As of October 2023, there were 96,338 Personal Public Service Numbers (PPSNs) given to arrivals from Ukraine in Ireland (Central Statistics Office, 2023a,b). According to the European Council's data from May 2023, Ireland had the fifth-highest number of Ukrainian refugees as a proportion of the population in the EU. The Eurostat figures show Ukrainian refugees account for 1.5% of the population in Ireland (2023). Out of all arrivals from Ukraine, only 1.5% or 1,134 PPSNs were issued for non-Ukrainian nationals (Central Statistics Office, 2023a,b). Nevertheless, this is a significant number of third-country nationals who sought refuge in Ireland after escaping Russian aggression in Ukraine. According to The Irish Central Statistics Office, most of the people who arrived from Ukraine are based in the West of Ireland (Central Statistics Office, 2023a,b). Thus, taking into account that the authors are based in the midwest region of Ireland, this paper focuses specifically on the Munster region, which is divided into Clare, Cork, Kerry, Limerick, Tipperary, and Waterford counties. While this research mentions some recent developments around TPD provision in Ireland, we focused our attention on the detailed analysis of the 2022 events.

Most literature on the issue of the double standard in how racialised-white Ukrainians are received and treated in comparison to racialised-Black refugees from Ukraine or asylum seekers from non-European countries is editorial in nature or present policy analysis (Berg and Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, 2023; Jackson Sow, 2022; Stapleton and Dalton, 2024). The most recent publication touching upon the effect of the TPD on public service provision in Ireland presented a case for how the beneficiaries of international protection were antagonised and further marginalised by the double standard of the system (Daly and O'Riordan, 2023). That research focused on the perspective of beneficiaries of international protection and highlighted some of the challenges they faced as a result of failed policy implementation. Our research builds on the previous literature by proposing a comprehensive analysis of the implementation of TPD and its impact on refugees from Ukraine in Ireland, using data from a parliamentary debate, and ethnographic observations by the authors. We discuss mechanisms of social exclusion, showing how instead of successful integration the TPD resulted in societal disintegration and divisive effects (Quigley, 1979; Stapleton and Dalton, 2024).

We had two main research questions: (1) How was the TPD implemented in Ireland? (2) How did the TPD implementation affect the experience of refugees from Ukraine and other groups in Ireland? Specifically, we ask if the reception and treatment of racialised-white refugees from Ukraine differed from that of TPD beneficiaries of other ethnic backgrounds and nationalities, or from that of other refugees seeking international protection (IP) in Ireland. We were also interested in the impact of political narratives around the TPD on the Irish community, specifically: public service providers and members of the general public who actively supported refugees from Ukraine.

The 3N model (Narratives, Networks, Needs) provides a comprehensive framework to structure our findings on how TPD policy, the Irish political discourse around it and its implementation through national institutions and local communities affected TPD beneficiaries and other groups in Ireland. The 3N model highlights that narratives encompass the forces shaping individuals' beliefs and worldviews, including cultural, political, economic, and social narratives (Kruglanski et al., 2019; Bélanger et al., 2020). Narratives are associated with macro-level forces influencing interpersonal and intergroup dynamics. Networks capture different social networks: friends, family, community members, and online communities and social media groups, helping us understand interpersonal and intergroup dynamics. Needs encompass individual-level factors such as a sense of significance, belonging, and personal autonomy, extended to other individual- or group-level variables. The 3N model accounts for the dynamic interconnectedness of various factors explaining the complex ecology of social issues (Kruglanski et al., 2019). Hence, this model is useful to structure our findings on how TPD policy and the Irish political discourse around it (Narratives) impacted interpersonal, intra- and intergroup dynamics between different stakeholders (Networks) involved in TPD implementation in Ireland. We also examine how the trends across Narratives and Networks dimensions addressed the individual needs of various TPD stakeholders in the Irish context.

2 Theoretical framework and context

Refugees and asylum seekers often undergo social exclusion, systematically denied the same rights, opportunities, and resources available to other members of a country of refuge who do not hold asylum-seeker or refugee status (Bloemraad et al., 2023; Ekins, 2020). These essential rights and resources encompass housing, employment, healthcare, civic engagement, democratic participation, and fair legal proceedings.

The Temporary Protection Directive (TPD) provides temporary protection to those displaced by the Russian war in Ukraine, requiring member states to grant access to rights and services, facilitate family reunification, and offer reception facilities. TPD beneficiaries are not required to seek international protection (asylum) to receive support and protection from EU states, including Ireland. The EU temporary protection offers a quicker, more streamlined alternative to the typical asylum-seeking procedure. Hence, TPD beneficiaries do not hold refugee status but benefit from temporary protection. In this paper, we use the terms “beneficiaries of temporary protection” (BoTPs) and “refugees from Ukraine” interchangeably, given the sociological definition of a refugee as someone “fleeing generalised catastrophe,” in this case, the Russian invasion and war (Owen, 2020).

Initially, the hospitality and solidarity shown towards refugees from Ukraine across European countries received widespread praise. However, academics and practitioners have strongly denounced the racist and orientalist double standards evident in responses to displacement from Ukraine (Bayoumi, 2022; Berg and Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, 2023; Jackson Sow, 2022). While Ukrainian refugees were welcomed with open borders across EU countries, racialised Black, Brown, and Roma individuals, along with third-country nationals, faced significant challenges crossing those same borders due to institutionalised discriminatory policies that perpetuate hostility and suspicion towards immigrants and refugees of African, Middle Eastern, and Roma descent (Banerjee, 2023).

The TPD is not the first time EU states have invoked measures of temporary protection. For example, European states introduced various schemes to admit displaced people temporarily after the war broke out in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1992 (Doeland and Skjelsbaek, 2018). That case also exemplified differential treatment of racialised-white and European refugees vs. non-European or racialised-Black, racialised-Brown, and Roma refugees. The paradox between policy intentions and their actual implementation is evident, with many romanticising the response to Bosnian migrants in the past (Gray and Franck, 2019). Baker (2017) previously showed how racism and cultural biases resulted in Bosnian Muslims being treated more favourably than refugees from Syria. Light-skinned Bosnians wearing Western clothes were not perceived as Muslim within the symbolic politics of Europe (Baker, 2017; Gray and Franck, 2019). Even before the arrival of visibly darker-skinned Muslim refugees from Syria, Europe treated Roma and ethnically ambiguous refugees from Kosovo with more xenophobia and racism than Bosniaks. While religiously diverse, many individuals fleeing Kosovo were of Roma or Albanian descent, racialised as “people of colour.” In Britain, these refugees were met with prejudice and anti-Roma attitudes (Baker, 2017). Previous policy analyses on why the TPD was not activated during the influx of refugees from Syria also cited underlying racialised, anti-African, and anti-Middle Eastern elements (Genç and Sirin Öner, 2019; Ineli Ciger, 2022).

Various psychological theories explain social exclusion and intergroup conflict, often focusing on threat and competition. If an outgroup is seen as a threat to ingroup resources, this often leads to discrimination, prejudice, and dynamics of social exclusion to protect the ingroup's position. The perception of finite resources distributed in a “zero-sum” calculation leads to intergroup conflict (Group Position Model and Realistic Group Conflict, Bobo and Tuan, 2006; LeVine and Campbell, 1972). Refugees and asylum seekers often become targets of prejudice and discrimination due to perceived realistic (economic consequences, public safety threat) or symbolic threats (cultural values) that nationals of the country of refuge associate with them, particularly through political and public discourse narratives (Integrated Threat Theory, Badea et al., 2017; Stephan and Stephan, 2000).

Policy and political discourse are crucial for answering our research questions and understanding the TPD's impact on multiple actors and stakeholders involved in its implementation in Ireland. To systematise our findings and show how different levels of our data interact, we used the 3N model and its key factors: narratives, networks, and needs (Kruglanski et al., 2019). Our study shows how Irish political narratives impacted the networks of service providers and the general public involved in helping refugees from Ukraine, as well as BoTPs' networks dependent on the different types of accommodations they were staying in. We also show how these intra- and intergroup dynamics helped address the needs or resulted in unfulfilled needs of all the actors involved in TPD implementation in Ireland.

We propose that the three components of the 3N model can be mapped onto ecological models or levels of analysis frameworks (e.g., Bronfenbrenner, 1981; Doise and Valentim, 2015) to analyse other social phenomena, involving people as actors in wider and interacting ecosystems. The 3N framework has been adopted and used by researchers within the field of social sciences beyond psychology when examining social behaviour or complex social phenomena (Kossowska et al., 2023; Szumowska et al., 2020; Zubareva and Minescu, 2023). By bridging theoretical perspectives, we can better describe and analyse pressing social challenges, such as the inclusion of refugees (Pedersen, 2016; Dalton et al., 2022).

Narratives play an important role in the structural-psychological approach, centering the context of societal power while maintaining a focus on the individual level and conceptualising structures and individuals as inseparable (Eekhof et al., 2022; Willems et al., 2020). The Narratives dimension allows for the dual investigation of external information sources, discourse, and structural characteristics of social systems, and their relationship with and impact on an individual's beliefs, attitudes, and cognition (Eekhof et al., 2021; McLean et al., 2023; Rubin and Greenberg, 2003; Willems et al., 2020). This paper, however, focuses on the first of a series of studies in the ongoing research project, and hence, we only examine the systemic or macro-level narratives and not the individual ones.

This study reveals how within a specific parliamentary debate, Irish politicians navigate policies and discourse and contribute to the socio-political discourse on refugee inclusion/exclusion. Policies are treated as narratives because they are shaped by policy decisions, implementation, and outcomes (Atkinson, 2019). Atkinson (2019) acknowledges the subjective and socially constructed nature of policy, highlighting the significance of narrative analysis in comprehending policy phenomena and their impact on policy discourse, public opinion, and problem-solving framing. It is also important to account for societal narratives in the form of historic processes, laws and policies, and public discourse, to understand how people end up on the vulnerability continuum of social inequalities (Adam and Potvin, 2017; Bobo and Tuan, 2006; Campbell, 1965; Jackson, 1993; Weber, 1978) and how economic, political, social, and cultural exclusionary mechanisms unfold dynamically across different levels of analysis and social structure (SEKN, Popay et al., 2008; Bloemraad et al., 2023; Penninx and Garcés-Mascareñas, 2016). Some trends discussed across the 3N dimensions in our study also align with the three policy gaps identified by Czaika and De Haas (2013) in their analysis of immigration policies: narratives dimension addresses the shortfalls of the TPD implementation vs. the written policies (i.e., implementation gap), networks cover the elements of discrepancy between public discourses and policies on paper (i.e., discursive gap), and needs cover the impact TPD in the Irish context had on its beneficiaries and migration (i.e., efficacy gap).

Our 3N model approach, combined with qualitative analysis and ethnographic observations, shifts the focus from government to governance to examine not only how policies are organised but also how they are implemented (Penninx and Garcés-Mascareñas, 2016). In this study, Narratives account for the Irish political discourse and the actual policies on paper concerning TPD beneficiaries in Ireland. Networks and Needs address policy implementation and its impact on various groups and individuals within Irish society. Networks explore: (1) how different service providers and general public volunteers overcame systemic challenges of policy incoherence and how their actions were informed by the political narratives people's social networks, (2) how BoTPs' social networks and interpersonal, intra- and intergroup relationships varied depending on the different types of accommodation they were placed in and how this affected their access to services. Needs refer to how well the TPD implementation in the Irish mid-west region addressed and fulfilled the needs of the different actors across the society involved in and with this process.

3 Method

3.1 Qualitative analysis of the Dáil Éireann (from Irish: assembly of Ireland) debate

To assess the political narratives around the TPD, we employed thematic coding as a methodological approach to analyse the statements from the transcript of a Dáil Éireann debate on the topic of “Accommodation Needs of Those Fleeing Ukraine” that took place on the fifth of May 2022 (could be accessed through the House of Oireachtas online archive: Vol. 1021 No. 5). Dáil Éireann is the lower house and principal chamber of the Oireachtas, the Irish Parliament. It is the main forum for parliamentary debates, legislative decision-making, and representation of the people in Ireland. It consists of 160 members, also known as Teachtaí Dála (TDs). The authors treated TDs statements as the primary data for analysis.

When it comes to refugee inclusion, policies, discourse, and public attitudes are always changing. However, this particular debate was held at the crucial time when Ireland was dealing with drastic demographic changes following the peak of arrival of TPD beneficiaries. Moreover, the topic of the debate related directly to the most pressing issue in Ireland—the housing crisis (Kitchin et al., 2015; Hearne, 2022; Lima, 2023). Most of the statements during the debate were directly related to the topics of the needs of those fleeing Ukraine, the shortcomings of the TPD provision, and how political decisions and legislation shaped the general public's willingness to help refugees from Ukraine. Also, by May 2022 the TPD implementation challenges were well-documented by public sector organisations and presented to different governmental offices. So, the political narratives shared during this debate and the Irish government's decision not to take any measures to address the presented challenges until later in autumn 2022 were very consequential.

3.2 Ethnographic observations

For 6 months the first author worked full-time as a Migrant Service Assistant with the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) UN Migration Agency in Ireland (March to August 2022). During this period, the first author worked directly with people who fled the Russian war in Ukraine and was responsible for managing over 300 cases involving family units. The primary focus of their work was on a project initiated by the Department of Children, Equality, Disability, Integration, and Youth (DCEDIY) in Ireland: relocation of refugees from Ukraine from temporary accommodation (such as hotels, former religious buildings, sports halls, youth hostels, student accommodation, other repurposed properties, and previously closed DP centres) to medium-term privately pledged accommodation. Irish Red Cross was another organisation involved in this project implementation. There were two types of pledged accommodation available to the TPD beneficiaries at the time when the first author worked with IOM Ireland: (1) vacant properties including apartments, houses, and granny flats; (2) shared accommodation where Irish residents pledged spare bedrooms in their apartments/houses. The first author worked in the Munster region, namely in counties Limerick, Cork, Kerry, and Clare. In addition to facilitating the housing transition, the first author also played a role in introducing beneficiaries to other available services and providing psycho-social support aligned with trauma-informed care principles. This employment experience provided the first author a deep and comprehensive understanding of the challenges different stakeholders encountered as the result of the TPD implementation in Ireland.

The second author was also engaged in supporting refugees from Ukraine in psycho-social support programs run together with a local community development organisation in the midwest of Ireland. The two investigators discussed their experiences, comparing journal notes and documenting their observations in meetings and conversations within the research team. The authors' observations are complementary to the analysis of the parliamentary debates and allow for the understanding of the group and individual level dynamics: the networks and needs of service providers, general public volunteers, and TPD beneficiaries. These experiences of working with the frontline service providers and refugees from Ukraine allowed the authors to identify the practical and logistical shortcomings of the TPD policy implementation processes.

The ethnographic observations documented within this study did not contain any individual data and are secondary in nature, indirect, generalised, and completely anonymous (no individuals were interviewed as part of this research; even though the first author conducted interview-based vulnerability screenings with TPD beneficiaries as part of their work duties). Despite their secondary nature, the authors attribute immense value to these observations at the frontline of refugee inclusion. They transcend mere trends highlighted in media discourse as both authors personally encountered and navigated the challenges and deficiencies inherent in the implementation of the TPD within distinct settings.

4 Analyses and findings

Overall, we use the data from the Dáil Éireann debate to identify the main narratives around TPD implementation and political discourse about TPD beneficiaries. We use the ethnographic observations to explain how the narratives impacted service provision, the general public's response, and TPD beneficiaries' experience of social inclusion/exclusion in Ireland. Irish political economy constraints and political narratives resulted in multiple challenges to public service providers, the general public volunteering to help refugees from Ukraine, and to refugees' abilities to access certain services and resources as well as their hindered ability to maintain existing social networks or form new ones. These network level challenges resulted in unmet needs of the Irish community members supporting TPD beneficiaries and unfulfilled needs of refugees from Ukraine leading to their economic, social, and cultural exclusion. Lastly, both the thematic analysis data and authors' ethnographic observations address the extent to which the needs of TPD beneficiaries were compared with the needs of other vulnerable groups in Ireland (e.g., IP beneficiaries).

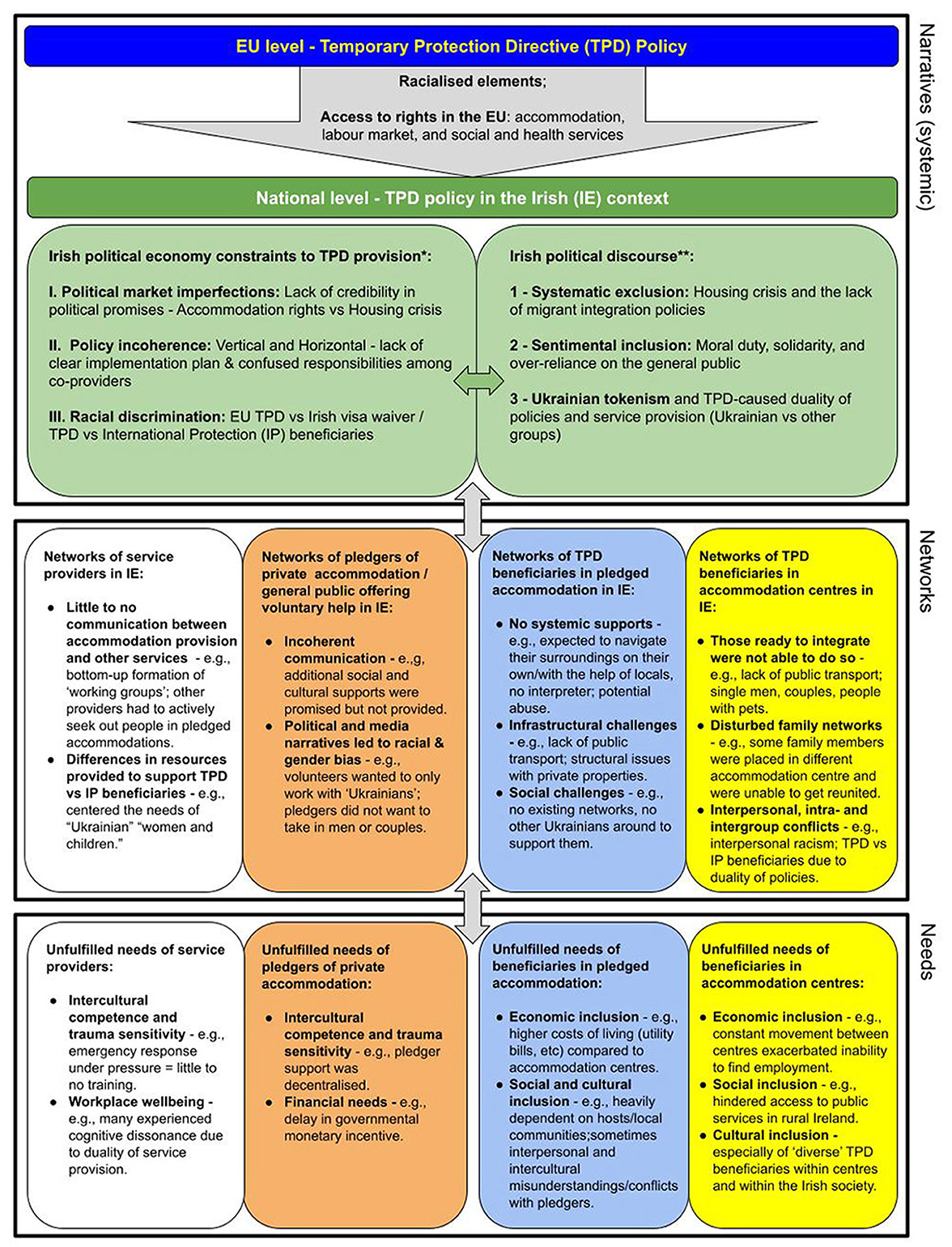

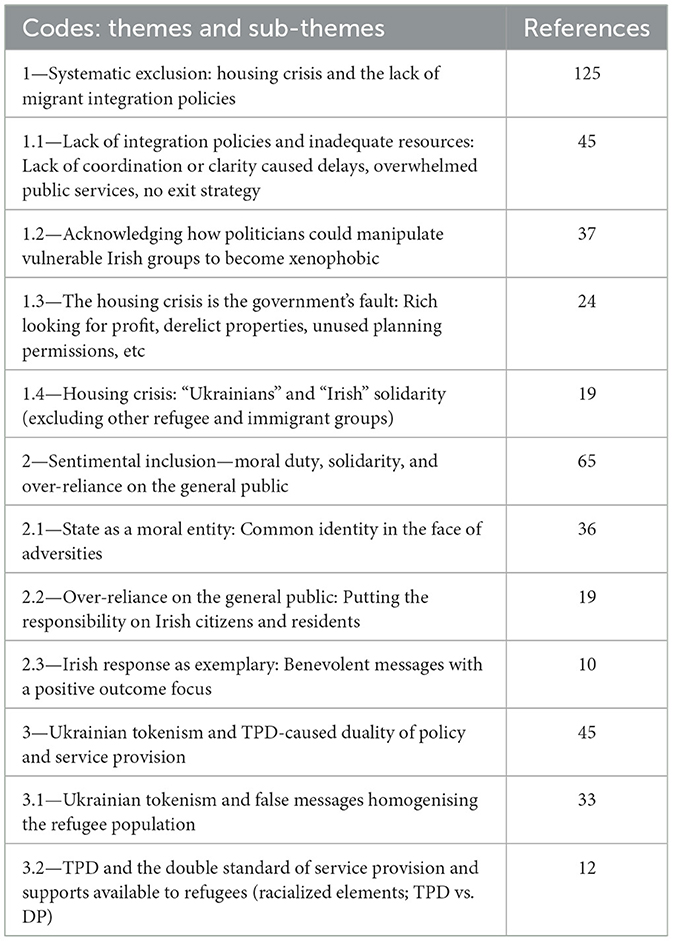

Our key findings, synthesised according to the 3N model dimensions, and their interconnections are presented in Figure 1. A summary of the main themes and sub-themes of the thematic analysis is presented in Table 1. We identified three main themes: “Systematic exclusion: Housing crisis and the lack of integration policies,” “Sentimental inclusion: Moral duty, solidarity, and over-reliance on the general public,” “Ukrainian tokenism and TPD-caused duality of the system and service provision.” We discuss these in the next section on narratives.

Figure 1. Key findings, synthesised according to the 3N model dimensions (Narratives, Networks, Needs), and connexions between them. *Adopted from the common political economy constraints and incentive problems that affect public service delivery (Wild et al., 2012). **The following three themes emerged from thematic analysis of Dáil Éireann debate (Vol. 1021 No. 5) on topic of “Accommodation Needs of Those Fleeing Ukraine” that took place on the fifth of May 2022.

Table 1. Thematic analysis of the Dáil Éireann debate results: three major themes with corresponding sub-themes and frequencies of references.

4.1 Narratives: TPD policy on the EU level and in the Irish context

The EU TPD has been critiqued for containing racialized and Islamophobic elements (Genç and Sirin Öner, 2019; Ineli Ciger, 2022). These narratives have subsequently influenced the national policies and service provision practises in Ireland (Daly and O'Riordan, 2023). An illustrative example concerns the visa requirements for TPD beneficiaries. Although legal eligibility for TPD was extended to include individuals who were permanent residents or benefited from international protection in Ukraine prior to the full-scale Russian invasion, as well as their close relatives, the visa requirements to Ireland were waived solely for Ukrainian nationals. This discrepancy resulted in numerous TPD-eligible individuals, who were non-Ukrainian nationals, being prevented from joining their relatives who entered Ireland without undergoing a lengthy visa process (Malekmian, 2022). The fact that many of these individuals lacked the necessary bureaucratic documentation required by the Irish immigration service made this TPD-eligibility vs. entry visa requirements discrepancy more complex. Some diverse refugees from Ukraine lacked the needed social support of their family members who were allowed to cross the Irish border. Interestingly enough, this policy decision seemed to have been potentially contradicting the TPD briefing by the European Parliamentary Research Service in March 2022 (PE 729.331) which stated that: “All persons fleeing Ukraine should in any event be admitted into the EU on humanitarian grounds, without requiring, possession of a valid visa (where applicable), or sufficient means of subsistence, or valid travel documents, to ensure safe passage with a view to returning to their country or region of origin, or to provide immediate access to asylum procedures” (Lentin, 2022).

Moreover, while TPD beneficiaries were guaranteed access to accommodation, labour market, and social and health services rights in the EU, the implementation of the TPD in Ireland has been hindered by various political economy constraints. According to Wild et al. (2012), unfulfilled political promises that hinder the relationship between state citizens/residents and politicians can have a significant and serious negative effect on public service delivery. The TPD guaranteed accommodation rights to its beneficiaries, but Ireland's housing crisis made fulfilling this promise difficult (Daly and O'Riordan, 2023; Stapleton and Dalton, 2024). When talking about the public service provision to refugees in Ireland it is important to take into account three other recent issues confronting the Irish public: the housing crisis, lack of investment in mental health services, and the cost of living crisis (Social Justice Ireland, 2023a,b; Citizens Information, 2023a,b,c,d). There is an Irish homelessness crisis: significant increases in homelessness rates are matched by a lack of affordable housing and government investment in social housing. By March 2022, at least 9,825 individuals were homeless, including 2,811 children, and this number rose to a record high of 10,568 individuals experiencing homelessness by August 2022 (Simon Communities of Ireland, 2022). The crisis is influenced by factors such as insufficient housing supply, rising rental costs, poverty, unemployment, and policy shortcomings, which were accentuated during the COVID-19 pandemic. The complex housing crisis was rooted in an economic downturn, insufficient investments, and inadequate regulation of the private rental market, resulting in a generation of Irish nationals being “locked out” of housing opportunities despite government initiatives (Hearne, 2022). Moreover, mental health issues affect 18.5% of the population (Mental Health Ireland, 2023). The mental health crisis is compounded by gaps in mental health service provision, historical stigma, and inadequate government funding (Power and Burke, 2021). Lastly, the cost of living crisis has become a pressing issue, impacting health service recruitment and retention and exacerbating the mental health crisis. The combination of all these issues significantly hindered the Irish state's ability to look after immigrants and refugees.

Additionally, there was a serious obstacle to TPD implementation and public service provision to BoTPs in 2022 due to policy incoherence (Wild et al., 2012). A lack of clear implementation plans and confused responsibilities among co-providers further complicated TPD implementation. There was not enough communication between different governmental departments for at least the 5 months that the first author spent working with IOM. International Protection Accommodation Service (IPAS) is a division of the DCEDIY, while homeless services are provided with the close partnership of the Health Service Executive (HSE), Department of Social Protection and voluntary housing bodies, and the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage (DHPLG) is responsible for housing, planning and local government supporting the sustainable and efficient delivery of well-planned homes, and effective local government. This further resulted in little to no communication between co-providers of public services.

When it comes to racialised elements within the EU TPD policy, these sentiments spilled over into the Irish implementation of the directive. In Ireland, TPD eligibility initially focused on Ukrainian nationals due to visa waiver. Apart from the instances of “racial” and ethnic discrimination of racialised BoTPs by the Irish border control and immigration officers, the TPD accentuated the difference in how European refugees from Ukraine were welcomed and treated vs. the inhumane conditions that international protection applicants and beneficiaries were subjected to by the Irish state (Daly and O'Riordan, 2023). For asylum seekers and beneficiaries of international protection, Ireland has set up a program of accommodation provision, called Direct Provision (DP). DP was initially introduced as a temporary measure, but remained a longer-term solution for asylum seekers. The extended stay in a system designed to be temporary has been heavily criticised for its substandard living conditions, limited privacy, and restricted access to human rights and socio-economic services (Daly and O'Riordan, 2023). Dehumanisation and isolation are significant challenges within the DP system (Lentin, 2022; Murphy, 2021). Calls for reform have emerged from human rights organisations, and the Irish government has proposed reforms for a more humane accommodation and support system, but limited capacity and external factors have hindered progress (Coakley and MacEinri, 2022; Murphy, 2021). Unlike TPD beneficiaries, asylum seekers in Ireland are generally not entitled to the same rights in accessing labour market, education, healthcare, or social welfare. Under the DP system, asylum seekers receive a weekly personal allowance of €38.80 per adult and €29.80 per child (Citizens Information, 2023a,b,c,d). TPD beneficiaries in Ireland were originally entitled to social welfare payments of €208 per week, as well as to other welfare benefits including but not limited to Child Benefit, Disability Allowance, and Rent Supplement (Department of Social Protection, 2023). BoTPs also received immediate permission to work, access healthcare, and enrol in education programs, with the government providing free education up to secondary level (Department of Foreign Affairs, 2022).

The influx of individuals escaping the war in Ukraine and seeking temporary protection in Ireland was initially met with a sense of “sentimental inclusion.” Perceived as European, racialised-white, and Christians, these refugees were welcomed with messages of sympathy and promises of easy integration into Irish society. However, those welcoming messages propagated by the Irish government were accompanied by misleading narratives. Despite the promises of integration and access to essential services, the reality on the ground proved to be starkly different. The existing grievances such as the housing and homelessness crisis further exacerbated BoTPs' predicament (Daly and O'Riordan, 2023). The Irish government's inability to deliver on promises of integration and access to essential services resulted in the systematic exclusion of Ukrainian refugees.

“Systematic exclusion: Housing crisis and the lack of migrant integration policies” was the theme with the highest number of codes from the Dáil Éireann debate. This theme highlights the ways in which the Irish government excluded and alienated BoTPs. One key message was the overt scapegoating of people fleeing the war in Ukraine for the potential worsening of housing availability, given the pre-existent ongoing housing crisis. Most of the politicians who deployed such polarising techniques in their public speeches denied the allegations during the Dáil Éireann debate. Nevertheless, other TDs (Opposition parties' representatives and independent deputies) called out their colleagues (Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, centre-right coalition parties members) on those instances of anti-immigrant rhetoric that exploited existing grievances. The following quote illustrates one of the TDs, Paul Murphy (People Before Profit), calling out Darragh O'Brien, the Minister for Local Government and Heritage of Ireland (Fianna Fáil) for his polarising anti-immigrant and anti-refugee rhetoric that aimed to absolve the Irish government from the responsibility for the worsening housing crisis.

I will start by countering the disgusting attempt by some on the far right to divide and rule and to try to blame the housing crisis on refugees from Ukraine or elsewhere. The Minister shook his head when it was mentioned a moment ago and indicated he did not say what he is reported as having said. He should clarify his comments because what seemed to be said on the radio was that a serious cause of the increase in homelessness is that people were coming from EEA and non-EEA countries and immediately going on the homeless list, as opposed to the very obvious reason for the explosion in homelessness that is the ending of the eviction ban. One can trace the increase in the numbers of homeless people from the end of the eviction ban.

Some codes within the “housing crisis” sub-theme addressed the issue of the government's unrealistic promises about accommodation options available to TPD beneficiaries in Ireland. This trope was quite common through the debate, especially among Opposition and Independent deputies. No precise information about emergency accommodation options was shared with TPD beneficiaries during the first half of 2022 (Department of the Taoiseach, 2022). The information that was shared publicly painted a false reality. The following quote from the Dáil Éireann debate illustrates it perfectly, deputy Michael Collins (Independent):

Ukrainian refugees are coming here on a false promise announced by a Government that has little or no plan as to where these vulnerable people are to be housed in the long term.

Ireland did not have the resources or capacity to provide free adequate accommodation for all new arrivals up to the standard that the earlier arrivals benefitted from. The largest cluster of codes within the “systematic exclusion” theme was related to the absence of robust integration policies for immigrants and the lack of resources to design exit strategies. That deficiency was evident from the TDs' statements reiterating that reforms for housing, healthcare, and other public services in Ireland were needed long before 2022. Such messages were shared not only by the members of the opposition, but by some members of the coalition from Fine Gael and the Green Party. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic and the emergency measures taken to mitigate it have had a significant impact on the finances of public services and local authorities (Shannon and O'Leary, 2021). As a result, most of these already overwhelmed systems were stretched thin following the arrival of refugees from Ukraine.

For example, some TPD beneficiaries needed the assistance of disability services, however, the Health Information and Quality Authority (HIQA) reported that compliance had declined since 2021 amongst the designated centres for people with disabilities (Health Information Quality Authority, 2022). One of the TDs, Seán Canney (Independent), raised his concerns with the fact that even Irish nationals did not have proper access to the needed disability services, hence, the system was not able to provide adequate support to vulnerable TPD beneficiaries:

Therefore, we have a huge challenge on our hands. We have a long-term problem in this country with services for disabilities but we now have an added challenge.

This quote illustrates that housing was not the only system that was under-resourced and unable to cope with the increased services demand. Ultimately, these challenges explain some of the political market imperfections in the form of disrupted relationships between Irish politicians and residents as well as lack of credibility in the political promises.

Some other codes under the “lack of integration policies and inadequate resources” sub-theme addressed the lack of coordination between different governmental offices and between agencies working on the TPD implementation. This caused significant delays and posed extra challenges at all levels of service provision. The following illustrates one of the TDs' concerns about the lack of coordination related to the medium-term accommodation provision, deputy Richard O'Donoghue (Independent):

The Red Cross is overwhelmed with the work it has to do. All the volunteers are overwhelmed. There is complete chaos. [...] the Red Cross wanted to go and see the house. The family agreed to meet the Red Cross there. Little did the family realise that the Red Cross volunteers were on a minibus with eight Ukrainian people with their suitcases. They were coming out to look at the house to see if it was viable for them. They took the suitcases off the bus and moved in straight away. A person with the Ukrainians had a letter but could not explain to the householder what had to be done, and that person was there to help. It is total chaos. The following day, I met a person whose job is to track where Ukrainian people are in order to put a map together so that where they are is known. That person asked me if I knew where Ukrainians had been placed and asked me to notify them because some of the Ukrainians have slipped through. They were put into houses but now it is not known where they are.

This storey was one of many the authors witnessed during their work with BoTPs and other stakeholders. The ethnographic observations also highlighted this lack of clear guidelines for service providers. Such policy incoherences had a serious impact on the Networks and Needs dimensions which we will discuss later in the paper.

The incoherent political narratives about accommodation solutions for TPD beneficiaries caused a growing perception that the government was focusing on the needs of the TPD beneficiaries while ignoring the needs of its own citizens. The third largest sub-theme under the “systematic exclusion” theme contained TDs' statements that emphasised that the housing crisis was the government's fault. Such statements aimed to hold the government accountable for the lack of adequate accommodation and at times shame the chief executives for their decision to bring more people into the broken systems, Réada Cronin (Sinn Féin, opposition, centre-left):

Sadly, for a lot of the Ukrainians coming the Government has made a shambles of their accommodation needs, adding to our housing crisis. I have people in north Kildare who would love to offer accommodation to people fleeing Ukraine if they only had a house of their own. However, in their 60's they are sleeping in their cars or camped out on their children's sofas.

Additionally, it is worth noting that the public perception of TPD beneficiaries being prioritised over Irish residents was not a mere trope. The uncoordinated response to housing TPD beneficiaries resulted in cases where governmental services did prioritise refugees from Ukraine over other vulnerable groups. The following storey shared by one of the TDs, Eoin Ó Broin (Sinn Féin), illustrates how there was a lack of horizontal communication between the International Protection Accommodation Services (IPAS) and other public services:

[...] while I fully understand and support the Government's accessing of hotel accommodation through [...] IPAS, there have been at least two instances where homeless service providers in Cork city and Wicklow have expressed some concern that hotels that would otherwise have been the primary source of emergency accommodation for families presenting as homeless are now fully booked up by IPAS. This is one of the imperfect solutions the Minister spoke about, but it is really important that there be the maximum level of coordination between his Department, IPAS and homeless service providers to try to avoid such a difficulty in as much as is possible.

Our ethnographic observations mirror this qualitative finding. The second largest cluster of codes within the “systematic exclusion” theme highlighted some TDs' remarks regarding TPD beneficiaries being prioritised over Irish nationals and residents who had been on a lengthy and slow-moving waiting list for social housing. While those narratives were untrue, some TDs emphasised that they could be used to manipulate other Irish marginalised groups to accept xenophobic and anti-immigrant views based on the perceived competition for limited housing opportunities and other governmental support.

These narratives were echoed by the deputies representing the coalition parties, even though they also reiterated that at the time of the debate the Minister for Housing managed to clarify the government's plan of housing refugees from Ukraine as being separate from projects aimed to address the Irish housing crisis and homelessness; deputy John Paul Phelan (Fine Gael):

In the past few weeks, I have noticed on social media, particularly WhatsApp groups, memes and jokey picture messages with an underlying, insidious element of racism, to be perfectly honest, in pitting refugees against people in Ireland who are in need of a home. I am glad the Minister for Housing, Local Government and Heritage has clearly outlined on a number of occasions that the funding for Housing for All is ring-fenced and separate.

Even the Minister for Housing, Local Government and Heritage, Darragh O'Brien (Fianna Fáil) paradoxically agreed with the criticism that deputies from the opposition addressed to him:

I do not agree with Deputies who heretofore opposed Housing for All using the crisis as an excuse to repeat their call for an immediate new national housing plan. That would only blur the lines of our response, confuse delivery targets, risk pitting one group against another and achieve nothing but further uncertainty in a volatile situation.

The initial lack of clarity on housing provision for TPD beneficiaries combined with political statements and media messages loaded with anti-immigrant rhetoric created a climate for future exclusion of refugees from Ukraine, and other refugee and immigrant groups in Ireland. However, the extreme rise of the far right sentiments and xenophobia did not really happen until early 2023 (Daly and O'Riordan, 2023). In the meantime, many TPD beneficiaries remained culturally (symbolically) included despite experiencing social and economic exclusion.

During the Dáil Éireann debate on the housing needs of the TPD beneficiaries, some TDs countered the anti-immigrant rhetoric employed by their colleagues. Those messages were included into the “Housing crisis: ‘Ukrainians' and ‘Irish' solidarity” sub-theme. Such statements emphasised that the government should promote social solidarity since all of the vulnerable groups were the victims of the government's neglect and inaction in relation to the housing crisis; deputy Eoin Ó Broin (Sinn Féin):

One of the great merits of the response of the Department of Children [...] is that it is seeking emergency accommodation outside the mainstream housing system. It is a sensible approach, particularly because it avoids putting Ukrainians who, rightly, are seeking refuge in competition with other people in acute housing need who experienced the rough end of our own housing crisis. At all times, the Government and the Opposition must ensure that, in everything we do, we do not in any way generate that kind of competition, or the potential resentment that could emerge from it, to ensure those fringe elements of our society who would seek to exploit that resentment are unable to do so.

Despite the systemic discrimination of vulnerable groups including refugees from Ukraine, the prevailing 2022 cultural narrative about TPD beneficiaries amongst politicians and the public was that of “Sentimental Inclusion.”

The second major theme of our thematic analysis is “Sentimental inclusion: Moral duty, solidarity, and over-reliance on the general public.” These codes reflect the sentiment-driven aspects of the debate, where the Irish state is viewed as a moral entity responsible for extending solidarity and support to those fleeing Ukraine. The following quote from The Minister for Housing, Darragh O'Brien, emphasised the importance of 'sentimental inclusion' of refugees from Ukraine, creating an illusion of care and concern while the government's actions did not reflect those sentiments in practise:

We will stand shoulder to shoulder with other democracies against authoritarian aggression. We will look after our people as well as those fleeing war and we will live up to the best traditions of fairness and decency towards those who need our support.

This quote presents a portrayal of the state as a moral entity, stressing its commitment to supporting refugees from Ukraine. However, despite the tropes of solidarity between democratic regimes, the Irish government's long track record of depriving immigrants and refugees, as exemplified by the dehumanising conditions within the DP system, raised questions about the sincerity of such statements. Moreover, the ruling party politicians' messages emphasising the commitment to take good care of and provide necessary resources to TPD beneficiaries appeared to be empty promises rather than political optimism. This was because the TDs and the ministers were well aware of the existing shortage of resources and were also informed about the numerous challenges related to the TPD implementation in Ireland before May 2022 (the reports on multifaceted challenges were submitted formally and informally to the Department of Justice, DHPLG, and the DCEDIY).

The theme of “sentimental inclusion” also covered codes describing the government's over-reliance on the general public where the policies and official support fell short. More often than talking about the moral obligation of the Irish government to TPD beneficiaries, the TDs emphasised the role of civil society in aiding refugees from Ukraine. Only a minority of the TDs acknowledged that relying on the Irish public and volunteers was not a sustainable solution. Most of the deputies representing the coalition stressed that Irish civil society would play a crucial role in sustaining the country's emergency response amidst the lack of proper integration policies; the Minister of State at the Department of Social Protection, Joe O'Brien (Green Party):

Successful integration will also happen very much because of the groundswell of support from individuals and communities across the country. [...] The fast, responsive and adaptable reaction of the community and voluntary sector across the country has been extraordinary.

While that TD's vision of successful integration is somewhat overstretched, given the multifaceted nature of challenges and crises that most Irish residents face, he was right in highlighting the instrumental role Irish communities played in the integration process of TPD beneficiaries.

Many TDs expressed a sense of hope and optimism, suggesting that there was a plan in place to address the challenges faced by the refugees and commended the public and volunteers for their efforts. The message was that the government and the public would work together to welcome refugees from Ukraine; the Minister of State at the Department of Health, Anne Rabbitte (Fianna Fáil):

For many their journey is not over just yet, but it will be. It will be soon, through our concerted and co-ordinated efforts. We must work together to realise this endgame. Ireland must show the céad míle fáilte today and every day. We must travel the end of the journey with them, and hold their hand while they assimilate into our country until such time as they can return to their homeland and rebuild their future.

However, we argue that the tone of many similar messages is tokenistic and lacks genuine substance. The repeated emphasis on the refugees eventually returning to their homeland and rebuilding their future may be seen as a way to placate the refugees without addressing their immediate needs and challenges. This sentiment can be viewed as disingenuous, given the significant barriers TPD beneficiaries faced in accessing essential services, accommodation, and integration opportunities, as mentioned in the earlier description of “systematic exclusion.” Many TDs employed exaggerated language, including hyperboles, to depict the compassionate and emphatic reception of TPD beneficiaries by Irish communities.

This rhetorical technique could be interpreted as an attempt to manipulate the general public's perception, fostering the belief that the government actually values their actions despite not providing any concrete support. Overall, while the narratives of “sentimental inclusion” could be seen as an attempt to convey a sense of compassion and unity, they are mostly lacking in a genuine commitment to address the complex issues faced by BoTPs and different vulnerable groups in Ireland.

The third theme uncovered during the thematic analysis of the Dáil Éireann debate: “Ukrainian tokenism and TPD-caused duality of the policies and service provision.” Citizens Information referred to BoTPs as “Ukrainian refugees” (Citizens Information, 2023a,b,c,d). Which echoes the pattern observed in our qualitative data as well. In all of the statements shared during the debate, the TDs referred to TPD beneficiaries as “Ukrainian guests,” “Ukrainians,” “our Ukrainian friends,” “Ukrainian refugees,” “Ukrainian visitors,” and so on. There was not a single instance of any TD using the term “beneficiaries of temporary protection.” A critical aspect of the exclusion experienced by TPD beneficiaries in Ireland relates to the prevalence of “Ukrainian tokenism.”

The dominant public narrative constructed by the government and local media portrayed the refugees as ethnically Ukrainian or holding Ukrainian citizenship, thereby marginalising individuals from diverse backgrounds who resided in Ukraine prior to the Russian invasion in 2022 or hailed from ethnic minority groups. Racialised-Black and racialised-Brown individuals encountered heightened discrimination and exclusion due to their non-alignment with the prevailing narrative that depicted TPD beneficiaries as racialised-white, European, and Christian. Ethnic minority groups from Ukraine, including Roma, similarly faced additional layers of social exclusion and discrimination, compounding their challenges in accessing services and integration opportunities. In addition, that narrative of European, racialised-white, and Christian “Ukrainian refugees” was used by some Irish politicians to further marginalise individuals benefiting from international protection; deputy Mick Barry (People Before Profit-Solidarity):

A headline in the Irish Independent last Monday morning read, “Migrants from countries other than Ukraine adding to pressure on homeless supports, housing minister warns.” Imagine if a few of the words in that were switched around in order that the headline stated, “Migrants from countries other than Ukraine adding to pressure on homeless supports, Le Pen warns.” That would fit perfectly well. The Minister is directly quoted in the article, and the headline does not jar in any way with the content of what he said. Unless the direct quotes in the newspaper article are made up or false, that headline reflects what the Minister said.

Since people normally use heuristics to place others into different social categories, the general public, following those narratives from media and political statements, started limiting “TPD beneficiaries” to “Ukrainians.” This further emphasised the binary perception of “good” refugees from Ukraine and “bad” refugees who do not fit that “European, racialised-white, and Christian” box. Further examples of systemic racism within the TPD implementation that exacerbated the divide between the beneficiaries of temporary protection vs. those seeking international protection include the government prioritising housing TPD beneficiaries over asylum seekers (Wilson, 2023).

Our qualitative data further supported the claims of the preferential treatment of TPD beneficiaries over asylum seekers in Ireland. During the Dáil Éireann debate, a few TDs voiced their concerns about the possible further marginalisation and worsening housing conditions for individuals benefiting from international protection in Ireland as a result of the mass influx of the new refugee group. However, only a few TDs, including Catherine Connolly, had openly pointed out the double standard of treatment as well as the double standards of sentimental concern and empathy levels that the Irish politicians held and promoted in relation to refugees from Ukraine vs. non-european refugees. Deputy Catherine Connolly (Independent) reflected on the similar sentiments expressed by Professor (Irish: an t-Ollamh) Fionnuala D. Ní Aoláin, United Nations Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism:

I will finish by going back to an t-Ollamh Ní Aoláin pointing out that it is a very dangerous policy. An t-Ollamh Ní Aoláin welcomes absolutely the open policy for refugees, as I do, but she makes it perfectly clear that they are white and European or on the European Continent and we have a completely different approach when refugees are not from the European Continent and when they are of a different colour. I raise that as a serious cause of reflection because as we speak, we have 2,000 people in Direct Provision who have no permission to go outside. They have the status and can go nowhere. We are ignoring what is happening in Yemen. We have ignored the Amnesty report on Israel in relation to Palestine and the International Criminal Court.

This quote truly highlights the double standards within the systems aimed to protect refugees in Ireland that are dictated by institutionalised racism. The double standards in attitudes that are then transmitted to policy and law—since policymakers are not impartial (Atkinson, 2019)—are also evident from the drastic difference in sentimental benevolence and empathetic concerns many Irish politicians express only in relation to the racialised-white refugees from Ukraine.

It is also interesting that because the debate was centered around the “Needs of Those Fleeing Ukraine” the deputies from the coalition parties did not have to mention the Direct Provision system, or refugees and asylum seekers who were within the Irish International Protection system—the opportunity that the coalition representatives availed of. Moreover, during the debate, as deputy Connolly was speaking the words quoted above, An Ceann Comhairle (the sole judge of order in the house), Seán Ó Fearghaíl (Fianna Fáil) said the following:

We wandered a bit away. The Deputy is passionate about the issues but wandered a little bit away from the issue of accommodation.

This interruption, given the following context of a quick verbal exchange between the deputy and An Ceann Comhairle, showed that some members of the coalition were indeed reluctant to talk about complex and intersectional issues that were closely tied to the TPD implementation in Ireland.

The further distorted message that shaped public perception of who TPD beneficiaries were repeatedly emphasised by the TDs and Irish media as “single mothers with children;” deputy John Lahart (Fianna Fáil):

Again, it is striking that when the coaches arrive there are many young girls, babies, women, mothers, and sisters, yet so few men. They are emphatically warmly welcomed.

Our ethnographic observations further explain how this narrative was not completely true, and yet it resulted in social exclusion of TPD beneficiaries who did not fit that “single mother” profile. According to the Central Statistics Office of Ireland, as of June 2023 of all arrivals under the TPD in Ireland 32% were aged under 20 (no sex/gender breakdown available), and of the people aged 20 years and over 46% were women and 22% were men. While adult men did represent the smallest proportion of the TPD beneficiaries compared to women and children, 22% is a large enough number approximately translating to 18,614 people. Nevertheless, men evacuating from Ukraine were excluded from the Irish mainstream media discourse or when included were presented in a way congruent with misandrist tropes emphasising the idea that men should stay in Ukraine and fight.

4.2 Networks and needs of Irish service providers

Preexisting shortage of staff and resources within the Irish public services and political market imperfections, TPD-related policy incoherence, racialised and tokenistic elements within TPD policy and its implementation mirrored by the political narratives of “sentimental inclusion” but “systematic exclusion” of BoTPS created significant challenges for both the Irish communities involved in supporting refugees from Ukraine and the BoTPs in Ireland (see “Networks” dimension of Figure 1).

Policy incoherence especially regarding accommodation provision for BoTPs and lack of clear communication from the DCEDIY with other departments resulted to little to no communication between accommodation provision services like IPAS, IRC, and IOM and other public service providers like the HSE, Education and Training Boards (ETBs), and Intreo (the Irish Public Employment Service). This had a negative effect on public service providers' networks and their ability to effectively and efficiently implement projects aimed at supporting TPD beneficiaries. Moreover, there was a lack of effective performance oversight from the DCEDIY and different divisions and organisations assisting with implementation of accommodation projects. Hence, there was no communication between co-providers of accommodation services. For example, IRC and IOM did not have any official channels of communication while both organisations were assisting the DCEDIY with the same medium-term accommodation project. There was also no official communication between IPAS, who managed temporary accommodation centres and providers involved in moving people from temporary accommodation to privately pledged (medium-term) accommodation.

To cope with these challenges and to try and maximise the efficiency of service delivery to TPD beneficiaries, public service providers had to initiate formations of local or county-wide “working groups” to minimise unnecessary duplication of services and projects that were already provided by other organisations. Some service providers working within the HSE, ETBs, and Intreo had to actively seek out people who were transferred from temporary to medium-term pledged accommodation since there was no official database of BoTPs staying in private houses available. This also meant that many TPD beneficiaries who arrived before the DCEDIY and IPAS rolled out a system of state-provided accommodation to arrivals from Ukraine were staying in private accommodations and lacked the access to systematised service provision that was available to beneficiaries staying in temporary accommodation centres. Moreover, as was observed by the second author: in some mixed DP centres housing both asylum seekers and temporary protection beneficiaries, the numbers of refugees from Ukraine varied significantly from 1 month to the next, and it was difficult to predict or account for especially for service providers who provide English language classes or psycho-social supports. Often the only person with the actual numbers was the manager of the housing facility, who would then communicate this to other local service providers.

The TPD-caused duality of policies and service provision resulted in preferential resource allocation to TPD beneficiaries over asylum seekers or IP beneficiaries. Moreover, the tokenistic political narratives resulted in services centering the needs of Ukrainian-speaking “women and children.” This resulted in systemic discrimination of BoTPs that did not fit this narrow stereotype. Service providers frequently found themselves unprepared to assist “diverse” BoTPs. For example, service providers would have had an interpreter or printed materials that addressed the needs of Ukrainian and Russian speaking BoTPs but not the needs of beneficiaries who spoke Arabic or Hungarian.

This TPD-caused duality of policies and service provision that manifested in the Narratives and Networks dimensions also affected service provider's psychological needs and wellbeing. Our ethnographic observations highlighted that many service providers from various public and governmental organisations in Ireland had concerns about the double standard of refugee treatment that the TPD created in the country. This was still the case at the “Ukrainian Support Staff Working Event” that took place on the 19th of April, 2023, organised by the Limerick community partnerships. Many healthcare providers, youth service workers, and social workers unanimously expressed their frustrations and disappointments in the discrepancy between the funding and support that was allocated for the beneficiaries of the TPD vs. asylum seekers and refugees staying in DP centres. Those frontline workers also struggled personally with their inability to support their clients living in the same accommodation but having different legal rights or financial resources as a consequence of the different sets of rules applicable to temporary vs. international protection beneficiaries. Some referred to the double standards and differential treatment comparing the very recent refugees from Afghanistan with the “Ukrainian” refugees.

Another important need for service providers to effectively work with BoTPs was the need for intercultural competence, basic geo-political and socio-cultural knowledge of ethnic diversity and language politics in Ukraine, and trauma sensitivity skills. However, the policy implementation constraints and political narratives that tokenistically homogenised TPD beneficiaries did not help to fulfil this need. Projects to support TPD beneficiaries were being carried out by the Irish government under a lot of pressure as some policy changes were frequently announced before any personnel responsible for implementation could have been trained.

An example of that was the DCEDIY's decision to roll out the project aimed at transferring TPD beneficiaries from temporary emergency accommodation to medium-term pledged accommodation without any proper announcements or briefings. DCEDIY had the goal of moving people to medium-term accommodation to free up some spaces in emergency accommodations. That pressure was fuelled by beneficiaries being unable to leave the reception centres, e.g., the Citywest Transit Hub, which were not designed to accommodate people for prolonged periods of time. After the bed capacity in reception centres was reached, TPD beneficiaries and asylum seekers had to sleep in armchairs and on the floors (Bray, 2022). There were at least two instances throughout 2022 when the Citywest Transit Hub was closed for new arrivals as the Irish government claimed that there were no more state-provided accommodation options for refugees from Ukraine or asylum seekers in Ireland (Balgaranov, 2022; Bray, 2022; Maliuzhonok and Bowers, 2022). Facing pressure from the DCEDIY to scale up the transfer project, IRC and IOM hired new caseworkers impetuously. As a result, some of those practitioners were not properly briefed and lacked an understanding of the policy or its implementation guidelines. This also resulted in accommodation service providers lacking the needed intercultural competences and trauma awareness and sensitivity. The lack of these skills and knowledge had a negative effect on BoTPs but also on the service providers because they were more susceptible to job burnout and vicarious trauma.

4.3 Networks and needs of Irish general public volunteers and pledgers of private accommodation

Networks and needs of the Irish general public who volunteered to help refugees from Ukraine and who pledged vacant rooms in their houses or their vacant properties to accommodate TPD beneficiaries were affected by Narratives as well as by service providers' Networks.

Following the political narratives of “sentimental inclusion” that called upon the Irish public to support refugees from Ukraine, in April 2022 about half the population were open to taking in a refugee from Ukraine, if they had a spare bedroom in their house. The willingness to do so was higher for Irish residents of middle-class background, Dubliners and Sinn Féin (centre-left), Fine Gael (centre-right), and Green Party (centre-left) supporters as opposed to the ruling party, Fianna Fáil (centre-right), supporters (Reaper, 2022). So, while initially the general public expressed higher levels of support and involvement in helping new arrivals from Ukraine, the shortcomings of the TPD implementation, namely policy incoherence at the governmental and service provision levels, caused the attitudes of Irish residents to change. Many Irish residents who were initially highly motivated to support TPD beneficiaries soon encountered barriers including NGOs' and governmental bodies' inefficient, non-transparent, and delayed communication with people who pledged vacant houses/rooms. Moreover, political narratives of “sentimental inclusion” were combined with the reality of “systematic exclusion,” meaning the lack of credibility in the political promises regarding the TPD implementation. Certain supports and resources like interpreters or social workers available to follow up on beneficiaries relocated to private accommodation were promised to the pledgers, however, in reality those supports did not exist. Hence, this ethnographic observation confirmed the authors finding regarding the Irish political narratives that emphasised “over-reliance on the general public.”

Hence, the Irish general public eventually shifted from supporting political narratives of “sentimental inclusion” and started shifting to supporting some of the “systematic exclusion” messages. Between February and April 2022 when the general public's support for refugees from Ukraine was still at its highest, around 60% of the Irish population stated that they supported the concept of introducing a cap on the numbers of refugees from Ukraine arriving in Ireland. About one third believed it should have been up to 20,000, with a further quarter not wishing it to exceed between 20,000 and 40,000 (Reaper, 2022). It was not until recently, November 2023, that the Irish Taoiseach (prime minister) started publicly discussing the government's intention to introduce some measures to 'slow the flow' of refugees from Ukraine, e.g., improving border control and introducing the cuts in TPD beneficiaries social welfare allowance (Hosford and McCárthaigh, 2023). In reality, however, there was a 72.1% increase in the number of refugees from Ukraine seeking temporary protection in Ireland in the 12 months to the end of September 2023 (Eurostat, 2023). This demographic trend combined with the mismatch of the government seemingly centering the needs of refugees from Ukraine in their debates and political narratives led to some groups within Irish society becoming more susceptible to anti-immigrant rhetoric as their own economic, social, political, and cultural needs remained unsatisfied.

Following the racialised elements within policy and political narratives, racial discrimination against “diverse” TPD beneficiaries manifested in the way pledgers and Irish volunteers interacted with BoTPs. The first author had a number of cases when pledgers were blatantly racist and only wanted to host racialised-white, ethnically Ukrainian, single mothers with children. One of the ethnographic journal notes contained a quote from an Irish pledger's response to a call about a potential match for a spare room in her house: “They are Ukrainians, right? [...] we don't need any g*psies. This is a good neighbourhood, we don't need any thieves.” Another family contacted the first author to make sure that the Roma family that had been accommodated in their vacant property were actually from Ukraine and were not “taking advantage of the system.” Their suspicions began with the beneficiaries only speaking Hungarian and Russian instead of Ukrainian. While those situations reflected the lack of diversity awareness among the general public in Ireland, the governmental statements and the media coverage further exacerbated the perception of the TPD beneficiaries as a homogeneous group of “racialised-White” Ukrainians.

“Ukrainian tokenism” narratives also heightened pledgers' misandry in relation to TPD beneficiaries. While there were many women with children who fled Ukraine to find safety in Ireland, a lot of times those women were not interested in pledged accommodation. There were several reasons for that which we address later when talking about networks of TPD beneficiaries. However, most pledgers were only interested in helping “single mothers with kids” and would sometimes fully withdraw their properties when informed that such a match was not possible. Moreover, most of the pledgers were strongly against single men or childless couples staying at their properties even if the pledged accommodation was fully vacant or detached from pledgers' house.

The first author also witnessed other cases of tokenistic solidarity with people fleeing the war in Ukraine. During her work as a migrant support worker, she witnessed some teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) offered their help on a volunteer basis to refugees from Ukraine but, when approached by a liaison officer, refused to offer the same level of support to refugees and asylum seekers from other countries even though these services are always in high demand in Ireland.

From the first author's ethnographic observations, this willingness to take in a refugee from Ukraine kept gradually declining throughout the summer and autumn 2022 with many Irish pledgers discovering the difficulties of sharing a living space with culturally diverse and sometimes psychologically traumatised strangers. This change in behaviour was to a large extent motivated by the pledgers' unfulfilled needs.

Similarly to service providers' need for intercultural competence and trauma sensitivity, pledgers were not offered any kind of training or briefing by the organisations responsible for the transfer project. The lack of ledgers' intercultural competence and trauma sensitivity skills was yet again exacerbated by “Ukrainian tokenism” narratives. Challenges listed by the pledgers ranged from the economic concerns about the growing utility bills, especially approaching the colder autumn and winter months, to language and cross-cultural communication barriers. And yet again, policy incoherence resulted in pledgers' unfulfilled needs. For example, to address pledgers' economic concerns and financial needs, the government announced the €800 per month incentive for those who chose to host TPD beneficiaries. However, the announcement was made in summer 2022 and the logistics of how to claim this monetary incentive were not made public until late autumn 2022. Hence, the financial needs of pledgers remained unsatisfied and this further exacerbated the general public's lack of trust in the political promises. Since the licence agreements signed by the pledgers and beneficiaries were not legally binding, some pledgers contacted the IOM and IRC to ask for assistance in moving TPD beneficiaries from their private properties back to emergency accommodation centres.

4.4 Networks and needs of beneficiaries of temporary protection in Ireland

TPD beneficiaries' networks and needs were affected by the policy and political narratives as well as by service providers' and private accommodation pledgers' networks and unfullfilled needs. Beneficiaries' networks and needs also differed depending on the type of accommodation they were staying in. We mostly focused on the differences between state-provided temporary accommodation centres vs. privately pledged accommodation (e.g., staying with an Irish host on in a vacant property).

Some BoTPs who arrived in Ireland days after the EU activated the TPD and the Irish state waved the visa requirement for Ukrainian nationals, found themselves in a strange situation, where unless they knew someone in Ireland, hardly anyone was able to provide them with any services or details on any supports available. This was yet again due to policy incoherence and the resulting the lack of training among service providers. In the first few weeks, there was no coherent official procedure on accommodation provision or tracking the TPD beneficiaries beyond the information recorded by the Irish immigration officers at points of entry into the state. Hence, some TPD beneficiaries stayed with Irish residents who volunteered to house refugees from Ukraine. This was not yet part of the official pledged accommodation project that was announced by the DCEDIY and IRC later in spring 2022. This private hosts whom BoTPs found through their social networks if they knew someone in the EU or in Ireland, social media posts, or multiple websites and online platforms that were created to help refugees from Ukraine find a host or shared accommodation (e.g., icanhelp.host, host4ukraine.com). While in many cases this was a nice gesture of generosity and solidarity, there were also cases of hosts who had questionable intentions in their readiness to house refugees from Ukraine. The first author, unfortunately, had a few cases where TPD beneficiaries in unoffiial private accommodation arrangements were forced into unpaid labour related to construction work or maintenance and cleaning of the property in return for living there. Another challenge that different unofficial living arrangements posed to TPD beneficiaries was that, once the state-run accommodation provision systems were in place, these beneficiaries were left outside of the system and if they had to move out of these private arrangements they frequently had to start from the very beginning and present themselves to the Citywest reception centre and then be placed at the bottom of the list of all the refugees awaiting alocation to temporary accommodation centre. Sometimes these exceptional cases were prioretised for the pledged accommodation project, but even then there was no guarantee that BoTPs were able to remain in the same city/town or even county where they had already established social connexions or secured employment.

Moreover, in line with contrasting narratives of “sentimental inclusion” byt “systematic exclusion” and the lack of transparency in vertical and horizontal communication between service providers, contrary to the expectations set by official online sources, TPD beneficiaries arriving in Ireland after April 2022 often found themselves placed in substandard emergency accommodations. These included community centres, sports grounds, or even tented accommodations that lacked essential facilities such as heating or proper toilet and shower facilities. While it is true that conditions for TPD beneficiaries were comparatively better than those within the DP system, the government and media did not publicly disclose the reality of substandard accommodations faced by later arrivals. This reinforced the false notion among refugees from Ukraine that Ireland was an attractive destination for TPD beneficiaries. When people find themselves under radical uncertainty, situations where outcomes cannot be enumerated and probabilities cannot be assigned, they use narartives to make sense of their situations and to make decisons on what to do (Johnson et al., 2023). Unfortunately for many BoTPs who arrived in Ireland, the political narratives they used for their decision making did not correspond with the reality of TPD implementation and service provision. From February till July 2022 official online sources, including 'Gov.ie' and 'Citizens Information,' failed to provide precise details about the emergency accommodations being utilised for TPD beneficiaries. Instead, these sources presented an incomplete picture, omitting crucial facts about the housing crisis and shortage of suitable accommodation in Ireland.

The housing shortage and high demand for accommodation made it exceedingly difficult for refugees to secure suitable living arrangements, leading to indefinitely long stays in overcrowded reception centres or substandard accommodation centres, and continuous uncertainty of being moved around the country with little to no notice due to the temporary nature of state-provided accommodation. In addition, due to systemic and professional networks challenges IPAS were operating in an emergency mode, consequently, paying little to no attention to how their decisions impacted local communities or TPD beneficiaries. This is corroborated by the second author's observations that the rules about state-provided temporary accommodation were not clearly communicated to beneficiaries, so some BoTPs lost their original allocated accommodation and had to return to the “IPAS list” before being able to be relocated to another location. Moreover, from the first authors' experience, some beneficiaries had disabilities or other serious vulnerabilities, but their specific needs went unnoticed for days or even weeks due to accommodation providers being overworked and language barriers.