- 1The School of Public Policy, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel

- 2Department of Psychology and School of Public and International Affairs, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, United States

How are ordinary people affected by the experience of stepping out against conventions that are central to their community? We conducted a field experiment in New York City to study Satmar Hasidic women's personal reactions to deviating from their community's high-end clothing norm by wearing an inexpensive plain dress (treatment) vs. carrying a prayer book (normative placebo) for one day. We find that women's experience of deviation from their community norm of high-end dressing was strongly uncomfortable, but was not internalized as new attitudes or self-perceptions. Instead, we find that the experience with deviance mostly affected women's perceptions of their community, in terms of their closeness to the community and to some of its central tenets, and the community norm of high end dressing. In this setting, the experience of individual deviation seems to change perceptions of the context—its norms and our relationship to our community—over perceptions of the self and of deviant action. The results of this study help to map out a theory of community and social change that accounts for individuals' anticipation of deviance and social experiences alone, together, and over time that affect their decisions about whether to participate in change.

1 Introduction

Thousands upon thousands of students sitting in Introduction to Social Psychology across the United States have received some version of the following assignment:

“Norms are prescriptions for accepted or expected behaviors. Your assignment is to violate one of the five norms listed below:

1. Sing loudly on a public bus, subway, or train.

2. Position yourself six inches from an acquaintance's nose during a conversation.

3. Stand on your chair in a restaurant and recite the U.S. Pledge of Allegiance.

4. Continuously jump up and down while waiting in a check-out line at a grocery store.

5. Get into an elevator crowded with strangers, and after the doors close, introduce yourself.”

(example from Plous, 2023)

After attempting one of these small (and sometimes larger) social humiliations in their community, the students are asked to write about the experience. How did it feel to deviate from the norm? How does your experience relate to what you have learned in your social psychology textbook about the power of norms? The intended lessons of the norm-breaking assignment hew closely to social psychology's central message about social norms—that they are important for guiding behavior in society, and that a norm's influence is often unacknowledged until the norm is bent or broken.

The norms targeted by the assignment resemble the pioneering norm-breaking or “breaching” demonstrations conducted by sociologists and psychologists like Goffman, Garfinkel, and Milgram (Goffman, 1963). These scholars identified everyday unacknowledged norms of social interaction, labeled residual rules (Scheff, 1960; Milgram and Sabini, 1978) or background expectancies (Garfinkel, 1991). Breaking these unacknowledged norms entailed asking for clarification on what basic phrases mean (“What do you mean by ‘how is she doing?”'), or asking someone to give up a subway seat without giving any particular reason. Their norm-breaking behaviors were sometimes met with confusion and cooperation, other times with disparagement and incredulity. Their accounts of how the experimenters and their naive participants dealt with a rupture in the unspoken rules of social engagement set the stage for a psychological understanding of norms as perceptions of typical and desirable behaviors and attitudes in our community. People internalize these normative perceptions and use them to self-regulate their behavior, and sometimes community members regulate behavior by treating norm deviants with disparagement, ostracism, or incredulity (Miller and Prentice, 1996; Cialdini and Goldstein, 2004).

While early studies examined how norms facilitated a sense of predictable social reality, psychologists moved on to understand how norms could facilitate negative group behavior, like false reality and violence (Asch, 1952; Milgram, 1965). Instigated by the events of WWII and the Holocaust, psychologists demonstrated how harmful norms could be established by authorities and peers to induce compliance with incorrect judgments or with abuse. That these studies experimented with many situations in which participants dissented with and deviated from peer and authority insistence on compliance was lost in the subsequent uproar over their findings that authorities and peers could induce compliance with such harmful requests. Compliance with a norm that involved changing one's sense of social reality or hurting another person against one's will became the focus of these norm investigations, at the cost of furthering inquiry on deviation and dissent (Jetten and Hornsey, 2011).

However, breaking with social norms is not only important when the norm is violent or incorrect—deviation from norms is also thought to keep societies healthier and better able to adapt to changing circumstances (e.g., Durkheim, 1938). More recent, interdisciplinary work focuses on understanding social norms and societal change that begins with norm deviance. Much of this work seeks to test which types of people, or which corners of a social network, are most influential over the rest of the community when they deviate from an established behavioral norm (e.g., Paluck et al., 2016; Dannals and Miller, 2017; Guilbeault and Centola, 2021). This type of research seeks to study deviance at scale—who can shift communities and societies?

While investigators have turned to study the influence effects of social deviance, or how one person's deviance can influence others (Jetten and Hornsey, 2011; Paluck et al., 2016; Dannals and Miller, 2017), the recent renewed focus on deviance has not included a focus on how individuals personally experience and are affected by their own deviation from a norm. Early work that focused on compliance with norms showed that when people anticipate breaking a norm they do so with a certain amount of dread, and they offer explanations to rationalize why their behavior isn't so deviant (e.g., Milgram and Sabini, 1978). However, because most studies focused on reactions from community members (e.g., Monin et al., 2008; Jetten et al., 2011), or recently, on the behavior of elite influencers who are thought to have particular sway over norm perceptions (Jetten and Hornsey, 2011; Paluck and Shepherd, 2012; Dannals and Miller, 2017), psychologists have less data to speak to the experience of deviance among ordinary people. We distinguish such “ordinary people” from the people identified by research as social norm entrepreneurs (Gomila et al., 2023), social referents (Paluck and Shepherd, 2012), or individuals who are less identified with mainstream norms (Dannals and Miller, 2017). We anticipate the experience of deviance among ordinary people to be more akin to the experience of students trying out a social norm violation exercise as a part of their class. In any story of social change, there are people who did not explicitly set out to change norms in their community or consider themselves to be change-makers, but who found themselves in a position of breaking a relatively important community norm. While self-styled change-makers who push the boundaries of their communities are important for social change, so too are ordinary people, who comprise the critical mass that a social or behavioral sea change is built upon. Knowing how ordinary people feel about and are changed by the experience of stepping out against convention—convention that is more central to their community identity than standing quietly on a bus or in a grocery line—is important for the project of understanding social change. This is the inquiry taken up by this paper.

2 The present research: ordinary people who deviate from a strong social norm

What happens to ordinary people—those who would not identify themselves as opinion leaders, norm entrepreneurs, or individuals who are less identified with mainstream norms—when they deviate from a strong social norm? By a strong social norm, we do not mean an implicit, unacknowledged norm akin to the “residual rules” studied by the early norm-breaking experiments, but a norm that is relatively important to the community and is explicitly and widely acknowledged. How do ordinary people feel when they break such a norm? Does the experience of deviance change their attitudes toward deviation, toward the norm that they broke, toward the self, or toward the community that reacted to their deviation?

Studying the experience of ordinary people who break from strong or established social norms in their community is an important piece of the larger inquiry into how norms function and how broader patterns of community change could unfold. In this paper, studying the experience of this type of deviance sheds light on why people don't want to deviate from norms, and when they might be willing to do so. An experimental test of the impact of deviance on ordinary people can tell us whether the experience of deviation causes a change in a person's outlook—on the norm that they broke, on deviance generally, and on the self. Finally, it allows us to test whether an experience of deviation distances or binds a person closer to the community whose norm they violated. Studying these questions among “ordinary” individuals who do not self-identify as deviants or opinion leaders helps us to understand these dynamics within the vast majority of the population—those who must follow the select few norm entrepreneurs if there is to be a more critical mass of change.

2.1 Strong norms in the context of the Satmar Hasidic community of Brooklyn

Strong norms can be found wherever a community identity is sufficiently distinct, such that a group of people perceives a prevalent behavior or idea to be something that “we” as a group do or believe (Prentice, 2012). Driving an electric car in an upscale progressive community in Northern California is one example of a strong norm, as is supporting the local football team in a community in rural Honduras. In this section, we describe how our research team documented and experimented with deviation from a strong norm in a tightly-knit community in Brooklyn—the Satmar Hasidic community.

In 2018, the first author, who at the time belonged to a separate Hasidic community in Brooklyn, was conducting qualitative research on poverty among the Satmar Hasidic community in Brooklyn, New York City. The Satmar community is a conservative division of the broader ultra-Orthodox Jewish community. Originally from Hungary, the Satmar Hasidic Jews arrived in New York after the Holocaust and settled down in two neighborhoods of Brooklyn: Williamsburg and Borough Park. Community members follow the principles of Hasidism established by Rabbi Joel Teitelbaum, which emphasize devotion in the performance of public and private rituals, charity, and the rejection of modernity. To protect their conservative lifestyle, the Satmar Hasidic community has distanced itself not only from non-Jews and secular Jews but also from Orthodox Jews, who adhere to less strict religious ideology (Poll, 1969; Kranzler, 1995; Deutsch, 2009; Keren-Kratz, 2017). For instance, contrary to other ultra-Orthodox Jewish subcommunities, the Satmar Hasidic Jews remain strongly opposed to the establishment of the secular state of Israel (Stolzenberg and Myers, 2022).

While poverty is not uniform across this community, it is prevalent (Roberts, 2011; Malovicki-Yaffe et al., 2018; Malovicki-Yaffe and Shafir, 2023). The Satmar, like other ultra-Orthodox groups, eschew modern higher education, and men often prioritize the pursuit of religious studies over participation in the workforce. Women are barred from higher education and are also less likely to participate in the formal workforce. In interviews with women about how they manage household finances, the first author repeatedly came across a major and unexpected additional financial stress: buying clothing for the women of the family. Across dozens of interviews, women stressed that one of the greatest financial pressures was dressing their girls in “respectable” clothing, which meant expensive designer labels like Gucci and Prada. The purpose of these clothes was more than a trousseau for the marriage market. Married women were also expected to walk out of their house dressed to look like they had expensive taste, or balebetish in Yiddish, the language used in the community and in the interviews. “Respectable” dresses could cost upwards of $400. For reference, this is roughly 11% of monthly rent for a large family in this neighborhood (Deutsch and Casper, 2021).

In these interviews women described the many sacrifices they made to ensure that they and their daughters followed the high-end clothing norm. Most were forced to cut into other expenses, such as not using heat for their apartment in the dead of a New York City winter. Some women were so ashamed of their inability to afford more of these high-end clothes that they would accompany their friends on shopping excursions and then secretly return the clothes by themselves later. While some women identified with the norm, stating that they enjoyed dressing their children well, others expressed a desire for the social expectation to be relaxed, stating they were “caught in a social cycle” (Malovicki-Yaffe and Shafir, 2023).

While Satmar Jews have many religious prescriptions, or Halachic laws, for women's dress, this norm of high-end dressing is not one of them. The religious law governing modesty in Hasidic society is explicit and precise. It dictates specific requirements for the length of sleeves, the thickness of socks, the types of prohibited fabrics, and the colors that are not allowed to be worn. These guidelines are clearly stated as religious codes. For example, girls who attend school cannot gain entry without adhering to those guidelines. Even if a girl dressed up in a less-modest way after school and off school grounds, she would still be dismissed from school. However, the norm of wearing expensive clothes is not formally written down, and there is no institutional enforcement or punishment for violating it. If a girl arrived to school in simple attire, no one would reprimand her. She may be less popular among her peers, but no one would consider her religiously incorrect; she would merely lose status in the eyes of her peers.

Dressing in designer labels emerged socially in this particular Satmar community—it is not followed by other Hasidic communities in Brooklyn and not by other Satmar communities internationally in Vienna, London, or Israel (the origins of the norm are beyond the scope of this paper). In interviews with the religious leaders of the community, the first author discovered that the arbiters of Halachic law, the Rabbis and religious teachers, were deeply concerned about the high-end dressing norm. Religious teachers had previously held a series of unsuccessful assemblies and discussions with girls about the virtues of dressing more plainly, even trying to incentivize less-expensive dressing with prizes. At one point, teachers made a rule that all girls had to bring their school supplies in plastic bags, as an attempt to diminish the norm of buying designer bags. Rabbis shared with the first author that there were so many religious requirements for women's dress that they felt they could not establish plain or less-expensive dressing as part of their official Halachic instruction.

More than standing apart from religious code, the norm of high-end dressing stands in opposition to Ultra-Orthodox religious values. Ultra-Orthodox Jews consider it pious to live modestly (Malovicki-Yaffe et al., 2018), which makes this norm inconsistent with one of the explicit religious values of the community. Poverty is even viewed as a sign of spirituality, and some community members consider poverty a necessary condition to focused study of religious texts (Malovicki-Yaffe, 2020).

2.1.1 The Satmar community as a context for an experiment on deviance

Although the Satmar community has to our knowledge never participated in a social science study, the existence of the strong norm of high-end clothing presented itself to us as an opportunity to study ordinary deviance from a strong norm. The norm was strong—openly acknowledged and discussed by the women and girls in the community who were affected by it. Most if not all women and girls followed the norm at great personal sacrifice, despite their privately expressed doubts and their leaders encouraging deviance. Our research team saw an opening for an ethical and psychologically well-placed experiment on ordinary deviance in this context. We felt that an experiment that randomly encouraged some individuals to deviate from the norm would be psychologically well-placed given this evidence that many women privately wished for the norm to change or relax. This means that deviance, while difficult, would not be fully unwelcome in the community (previous retrospective studies of social change have pointed to the revolutionary potential of this imbalance between public conformity and private dissent, e.g., Kuran, 1997). We also judged it possible to field an ethical version of this experiment because there was clearly-identified support for changing the norm from community leaders (teachers and Rabbis), and because the lead author of the study belonged to a neighboring community and worked with members of the community who could inform the design, measurement, and the consent process. Moreover, reducing adherence to a norm requiring individuals living in poverty to spend money could have a positive offset for them of saving money, all the while adhering to the community's religious value of modest means. We describe our ethical guardrails for the experimental design and implementation in more detail below.

3 Experimental rationale and hypotheses

We conducted a field experiment to study Satmar Hasidic women's personal reactions to deviating from their community's high-end clothing norm. While it is not possible to randomly assign an act of deviance, we can randomly assign an invitation to deviate, specifically an invitation to wear a “yachne”, or an inexpensive and plain, dress for the day (but one that follows Halachic laws of modesty). Thus, the deviation is from a social norm and not a religious law. Specifically, we recruited Satmar Hasidic women and asked if they would participate in our study called Einer Tug Programa, which could be translated from Yiddish as “One Action Day.” If they agreed, not knowing the exact actions to be taken on that day, a random half of these individuals was assigned to an invitation to wear an inexpensive plain dress for the day. The other half was invited to carry a Siddur (prayer book) for a day, a normative activity.

We ask the following questions about the effects of their experience. Because each question is submitted to a two-sided test, we map out theoretical reasons for movement in either direction. First, how do women invited to violate the high-end clothing norm feel, relative to those invited to do a normative activity for the day? This is perhaps where psychological literature is richest in its predictions. Many studies suggest that a great deal of the negative experience of norm violation comes from the self (Milgram and Sabini, 1978). For example, even when Milgram's experimenters “successfully” broke a social norm by taking someone's subway seat after providing no justification, Milgram reports that they often felt that they had to pretend they were sick, and felt guilty. Subsequent work shows that internalization of community standards will cause deviation to feel odd, inappropriate, or shameful (Cialdini and Goldstein, 2004). But along with self-imposed negativity, the community could explicitly rebuke a norm deviant (Festinger, 1950; Link and Phelan, 2001; Major and O'Brien, 2005; Jetten and Hornsey, 2011). However, since a great deal of this literature was initially qualitative or has come from anonymous fictitious community settings of behavioral games, the size of an effect of deviance on feelings is unknown at the outset.

Second, will deviance change individuals' attitudes toward deviance itself, meaning, could these individuals come to view deviance more positively or negatively? And could an experience of deviance change individuals' view of themselves as deviants? Some research has found that violating norms limits an individual's ability to build or maintain rewarding relationships within their community (Jetten and Hornsey, 2011; Monin and O'Connor, 2011). If a person who deviates from a norm is punished or marginalized in their community, they may be more inclined to conform in the future as a way to recover a sense of belonging and social approval (Williams et al., 2000; Cialdini and Goldstein, 2004). Theories of the self also predict that norm violation might result in future conformity. Schwartz (1973) theorized that when a social norm becomes personal, “anticipation or actual violation of the norm results in guilt, self-deprecation, loss of self-esteem; conformity or its anticipation results in pride, enhanced self-esteem, security”. More broadly, social psychologists have proposed that a central motivation to conforming to social norms is the anticipation of the pain of perceiving oneself as a deviant (Prentice and Miller, 1993; Chaiken et al., 1996; Cialdini and Trost, 1998). Taken together, these bodies of work provide support for the hypothesis that violating social norms leads individuals to be more inclined to conform to social norms, as a way to restore social belonging and a positive self-concept.

However, the experience of violating a social norm may make individuals realize that deviating did not feel as bad as they had anticipated. Past research suggests that individuals anticipate that public act of deviance will negatively impact their relationship with others or have negative consequences for the self (Schwartz, 1973; Prentice and Miller, 1993; Cialdini and Trost, 1998; Cialdini and Goldstein, 2004; Chang et al., 2011). However, if these consequences are milder than expected, the experience of violating a social norm may lead them to reconsider these costs for the self. This mechanism could operate in two different but related ways. Individuals who notice that others did not respond as negatively as expected may depreciate their perception of the strength of the specific norm that they violated. This could make them more inclined to violate similar norms in related contexts (Tankard and Paluck, 2016). As another mechanism, individuals could notice that others did not react as negatively as expected to their public act of deviance, and may infer that within the community norm violations are not as strongly punished as they believed. These reappraisals of the perception of the strength of the norm or of others' reactions to deviance could lead individuals who have deviated from a norm to do so again in the future.

As for whether an experience of deviance prompts a reappraisal of the self, theories highlighting individuals' need for coherence and consistency (Markus, 1977; Bruner, 1990; Swann and Bosson, 2010) provide hypotheses. Individuals could seek a coherent story about the self after deviating by shifting their view of the community or by integrating deviance as part of their identity or self-schema (Markus, 1977). For example, individuals may view the community as more heterogeneous in its behavior or they may begin to see themselves as “the deviant type.”

Third, we ask will violating a norm of high-end clothing cause attitude change toward the object of the norm itself—high-end clothing—or of perceptions of the strength of the norm in the community? In terms of attitudes, women may choose to justify their decision to deviate with a more negative attitude toward high-end clothing. However, if they did not enjoy the experience of wearing the plain dress, or if they chose not to follow through with the deviation, they would not feel a need to balance their attitude with counter-attitudinal behaviors (Heider, 1946). Perceptions of norms might shift in response to the sheer existence of a program that asks them to violate the dress norm, because its existence suggests that a growing number of community members do not support the norm. However, the reactions received to their plain dress may reinforce their perception of the strength of the norm.

Fourth and in an exploratory final question, we ask Does an experience of deviance make women feel more or less close to their community, in terms of their pride in the community and their enthusiasm for some of its core values? It is possible that experiencing community criticism would cause women who choose to deviate with plain dresses to feel more distant from their community. Distancing from the community might also be a way to rationalize the act of deviation. However, if women struggle to deviate or do not enjoy deviating for other reasons, it might reaffirm for them why they enjoy their community's status quo and why they subscribe to its core tenets.

4 Method

4.1 Experimental design

4.1.1 Recruitment

A team of research assistants composed exclusively of Hasidic Jewish women (the first author and Satmar women from the community) built a convenience sample using a referral sampling strategy. The first author identified teachers and religious leaders in the Satmar community in Brooklyn who helped build an initial list of 293 names and phone numbers of women to invite to participate. The first author and her research assistants contacted women from this list on the phone and introduced the study. The introduction of the study followed the same script (full script in Supplementary material 6):

“The one action that we ask participants to do is usually quite simple and requires no training or particular effort. The actions were chosen in collaboration with Rebbetzins and community members to address some pervasive issues in the community. In this sense, you may be assigned to do something that will make you feel some discomfort, like social discomfort. Remember that you can decide to withdraw at any time.”

Research assistants informed prospective participants that they would not receive any compensation for completing the activity, but that they would receive $20 if they agreed to complete a questionnaire within 24 h of the activity. This was done so that we could be sure to collect data on any women who decided to withdraw, and for ethical reasons (see below).

After providing these general details about the study (without specifying which activity they would be assigned) and responding to prospective participants' questions, research assistants asked for women's official consent to participate. If participants consented, they were randomly assigned and informed about their activity—wearing a plain dress or carrying a Siddur for a day. Prospective participants who decided not to participate in the study at this stage were thanked for their time and were subsequently contacted by phone to collect only demographic information.

4.1.2 Experimental conditions

The first author and her research assistants visited all consented participants in their home to activate the treatment or control task and deliver the paper-based outcome survey. These visits were initiated in random order, staggered across one month.

Treatment condition: the “plain dress.” We asked treatment participants to wear a “plain dress”, which we would provide to them in their size. This dress was not made by a high-end designer and was obviously less fancy (although it was new and modest), compared to the prototypical dress a Satmar woman would wear in Brooklyn. As a result, by wearing the plain dress in public, participants assigned to the treatment condition would experience a public deviation from the high-end clothing norm.

The day before a participant's agreed-upon activity date, the first author or a research assistant brought a selection of three plain dresses in her size to her house. The three dresses were presented so that the participant would have a choice in what she wore. The presentation of this choice was motivated by the idea that it could help the participant to feel more like an initiator of the deviant act, as opposed to someone who was complying with a research team's request (Festinger and Carlsmith, 1959). This design choice presents a small tension with the goal of having one uniform treatment. Thus, the three dresses that the research team selected for the participant's choice set made it extremely likely that all participants would choose the same dress. Specifically, two of the three dresses were so plain and inexpensive that the research team found a group of pilot participants all chose the third least-plain dress. This is also what all of the experimental participants chose (Supplementary material 7).

After the participant chose her dress, the experimenter asked her to wear it for the entirety of the next day and encouraged her to meet with at least two close friends, at least two extended family members (i.e., family members who are not parents or siblings), and go to the market or to another public space.

Control condition: the Siddur. One of the most normative activities of the Satmar community is to signal religiosity and piety, and so experimenters asked control participants to carry a Siddur (i.e., prayer book) for a day. All participants already owned a Siddur, so the visit to the control participants consisted of asking them to visit the same types of people and places as the treatment participants with the Siddur. Clothing was not mentioned.

4.2 Data collection

At the conclusion of their visit to each participant, the experimenters gave them a sealed envelope containing the paper survey. Participants were asked to complete this survey within 24 h of completing their activity and were informed that they would receive a $20 cash compensation for completing the survey. To discourage participants from opening the envelope and responding to questions before completing their activity, the envelope had a wax seal (Supplementary material 7). A religious regulation in the community prohibits breaking a wax seal against the sender's instructions, and so the seal provided a barrier to ignoring the experimenter's instructions.

The outcome survey, detailed below, included questions about the participants' experience with their assigned activity; their attitudes toward deviance including their own inclination to deviate in the future; their personal views and perceived norms with regard to high-end clothing; and their closeness to their community and to some of its central tenets. The survey, which is included in Supplementary material 8, involved both open-ended and Likert-scale questions. For all survey questions, participants were asked to circle a number between 1 and 7, which they used to indicate low levels of agreement (= 1), medium levels of agreement (= 4), or high levels of agreement (= 7) with various statements.

4.3 Survey items and outcome construction

4.3.1 Experience with their assigned activity

In a series of open-ended questions, we asked participants to qualitatively describe the activity they carried out: what they did, whom they met, where they went, and whether they encountered any obstacles in carrying out their assigned activity. To quantitatively capture their experience with their assigned activity, we computed an index of five Likert-scale questions asking participants to indicate their agreement with three different statements about their feelings during the activity: “weird”, “good” (reversed), and like they were “standing out” of the crowd. Two additional items asked participants if they thought that people around them: “noticed something unusual” or “were judgmental” toward them.

4.3.2 Attitudes toward deviance and toward the self as a deviant

Own inclination to deviate from social norms. To examine if the treatment causes participants to be more or less inclined to deviate from a social norm in the future, we ask seven questions that form an index. We measure participants' willingness to violate five different counter-normative behaviors in the Satmar community: using a kosher smartphone with access to the filtered internet1 to purchase clothes, having a kosher smartphone with access to the filtered internet, purchasing and wearing less expensive clothes, dressing casually, and volunteering for non-Hasidic organizations that help people outside of the community. We include two additional pre-registered exploratory measures in the index as well: willingness to sensitize other community members to the problems that come with wearing expensive clothes, and to learn to drive a car.

Willingness to help others deviate from social norms. To examine if the treatment causes participants to be more or less willing to help others deviate from a social norm, we asked about their help with two actual projects in the community founded by Satmar women. We asked if participants would be willing to help these projects by talking with the founders on the phone, regarding (1) her project teaching about healthy food, or (2) her project encouraging women to exercise at a gym.

Perception of the self as deviant. We asked two sets of items about participants' perceptions of themselves and their personal costs from and identification with deviance. Two items captured perceived personal costs of deviance: “I would never do something different from my friends because it feels too bad,” and “It's easy for me to do something different from my community in order to improve it.” Two items adapted from the self-monitoring scale (Snyder, 1979) captured identification with deviance: “I see myself as someone who is strong enough to stand out of the crowd” and “I see myself as someone who will always try to fit with the crowd.”

4.3.3 Personal views and perception of the community norm of high-end clothing

Personal views and norm perceptions Two questions were repeated, once to assess personal views about the high-end clothing norm and once to assess perceptions of the strength of the community norm. The question asked participants to rate their agreement with: “I believe [in general, women think] that buying and wearing expensive clothes is important”, and “If I [in general, women think that if they] don't wear expensive clothes, my [their] family and friends will not like me [them] as much.”

4.3.4 Closeness to the Satmar community and its central tenets

We asked four exploratory measures to test if the deviance treatment could alter participants' closeness to their community and to its central tenets, in either direction. Together, these items characterize participants support for their community and its status quo (Jost et al., 2004). Two of these measures focus on participants' views on piety. In the Satmar Hasidic community, modest living is viewed as pious and as a sign of focusing on the spiritual domain (Malovicki-Yaffe et al., 2018). We asked participants to indicate the extent to which they agreed with the following two statements about piety: “I think that poverty gives a better perspective on life”, and “I think that the least fancy people have a better perspective on life.”

The remaining two measures capture the extent to which participants are proud of the Satmar community. To capture their views of their local community, we ask participants to indicate their agreement with: “My community in Williamsburg/Borough Park is the best Jewish community in the world.” This language was suggested by Satmar research assistants and community leaders because the Satmar Jews in Brooklyn commonly refer to their local community as “the best Jewish community in the world!” To capture their views on non-religious political authorities in the community (asokonims), participants indicate their agreement with: “There is a good reason for every act that the asokonim in the community does.”

4.3.5 Index construction

As per our pre-registration, all outcomes are presented as indices that consist of multiple components. Where applicable, we reverse code responses such that all items are directionally similar. Given that all items in any given index use the same response scale, we construct each index by taking the mean of all non-missing items in that index.

Our pre-registration specified a composite of two questions that, upon reflection, the research team did not feel should be averaged as an index. We report the findings for each separate question at the end of the results section. First, we asked participants to report the extent to which they would like to volunteer for ultra-Orthodox chesed (i.e., charity) organizations. Second, we asked participants about the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with the following statement: “When I think of myself and other women, I hope that some things will change.”

4.4 Ethics

The recruitment, consenting process, experimental treatments, and outcome measurement were all designed by and in close partnership with the first author who is Hasidic and with women and leaders in the Satmar community. Members of the Hasidic community generally and the Satmar community specifically could ensure that the research stayed within Halachic law, which was necessary for participants. Along with the Princeton IRB (approval #11441) the research was granted permission from Satmar religious and political authorities. Beyond any violations of Halachic law, Satmar research assistants and leaders also helped to make sure nothing that was asked of the participants would be too foreign or uncomfortable.

Every effort was made to explain to participants that it was their choice to participate and to drop out at any time, during recruitment and during the consent. For this reason we also incentivized participation in data collection and not the actual activity, so that women could feel comfortable saying no to wearing the plain dress while filling out the survey.

Although the plain dress was piloted to ensure that it would represent a deviation from the high-end clothing norm, it was also piloted with Satmar research assistants to ensure the wearers would stand out but that women would accept to wear it.

All communication with participants was developed in Yiddish and English so that the research team could communicate with participants in the language in which they felt most comfortable. The first author made her personal phone number available to all participants for clarifications and any other conversations regarding the study.

4.5 Analytic strategy

We preregistered our hypotheses and exploratory analyses on the Open Science Framework. Our pre-registration can be found on the following link: https://osf.io/g5q73/.

Given the randomized design of the experiment, our primary analysis relies on ordinary least-squares regressions of treatment assignment on the outcomes to identify our causal estimands of interest using the following specification:

in which yi is the outcome for the i'th participant, τ is the intent-to-treat effect (i.e., difference in means between the control and treatment conditions), Zi is a treatment assignment indicator for the i'th participant, and ϵi is an error term. We use all of the survey respondents in the analyses, whether or not they complied with the treatment (i.e., the intent to treat analysis). We do not account for missingness in our outcome variables for the main analysis reported in this paper since we did not anticipate it for this immediate round of data collection and therefore did not pre-register it.

We provide analyses in the Supplementary material that account for missing values from those who did not take the survey or complete a specific question. These additional analyses are consistent with the process we specified in our pre-analysis plan for addressing missingness in our second round of data collection. These additional regression analyses employ inverse probability weighting (IPW; Gerber and Green, 2012; Gomila and Clark, 2019) to render the treatment and control groups relatively more comparable by up-weighting the responses of respondents who are most similar to non-respondents.

Finally, to account for noncompliance in our analyses, in our Supplementary material we report instrumental variables regression analysis (IV analysis; Angrist and Pischke, 2009), which derives the treatment on treated effect (TOT), that is, the causal effect of violating the high-end clothing norm among those who complied with the randomly-assigned invitation to wear the plain dress.

4.5.1 Deviations from pre-analysis plan

In our pre-analysis plan, we indicate that we will collect two rounds of data - one immediately after the activity (within 24 h) and one two (2) weeks after the first round of data collection. Unfortunately, collecting data two weeks later was impossible, due to the amount of time it required and the first author's departure for a faculty job in Israel. In this paper, our main analysis does not account for missingness; however, we present additional analyses in the Supplementary material that use inverse probability weighting, which was preregistered for round 2.

We generate and report four new indices that group together outcomes that were mentioned as exploratory measures in the pre-registration plan or not at all and were not envisioned as collapsed indices. We do this for greater simplicity of presentation, but in our results section we present both the index and the individual items. The first index we create captures participants' experience with the activity (Table 1), the second and third capture their personal views and perceived strength of the social norm with regard to high-end clothing, respectively (Table 3), and the fourth captures the four pre-registered exploratory measures measuring closeness to the Satmar community and some of its central tenets (Table 4).

We report one pre-registered index, a composite of two questions, as two separate questions. As noted in the measurement section, the authors could not justify averaging two questions that addressed such different topics.

Finally, we add two of the pre-registered exploratory items to an index describing willingness to deviate because of their conceptual similarity with the rest of the items. These items include: (i) “I would like to be able to drive”, and (ii) “I would like to speak with girls in the community to sensitize them about the problems that come with wearing expensive clothes.” Like the pre-registered index items, these two items do not respond to treatment, so combining them with the other items simplifies the description of results and does not change our conclusions. We present two indices with and without these two items in Supplementary Table S1 to demonstrate that this does not change the results in any way.

Finally, to construct indices we took the mean of all non-missing items in that index, without using mean imputation for missing data. The pre-registration specified using mean imputation but our standards on this issue changed in between pre-registration and analysis.

5 Results

5.1 Sample and implementation lessons

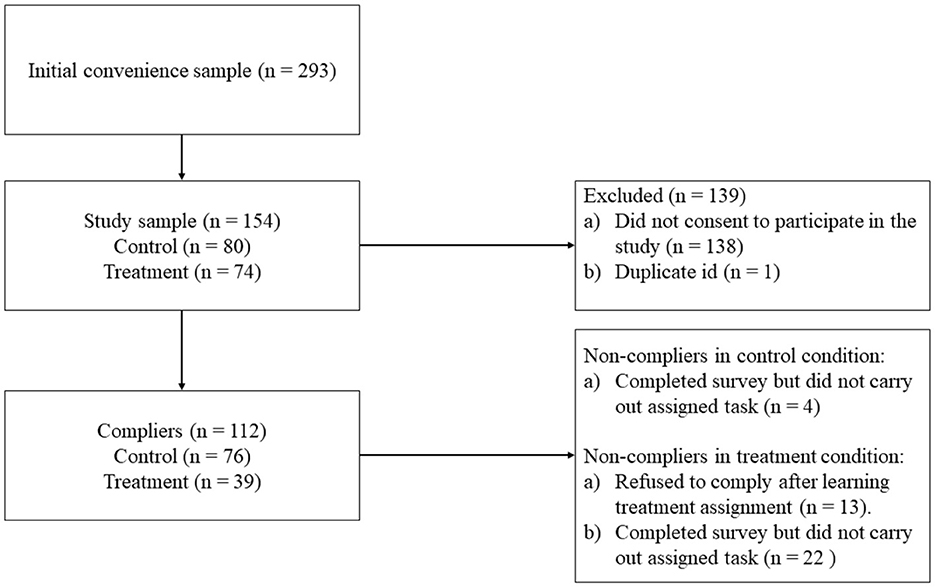

As described in Section 4.1.1, an initial list of two hundred and ninety-three (293) women was generated by research assistants and community leaders for this research. When these women were contacted by the first author or a research assistant to secure consent to participate in the study, forty-seven percent (47%) refused to move forward with the study (see Figure 1 for more details). This high rate of refusal may in part reflect the fact that the initial list was generated by individuals who were highly connected members of the Satmar Jewish community, but the person who subsequently contacted them was less familiar to them and was related to a secular university. Some of the reasons given by potential participants included: not being interested in the study, wanting additional information about the activity they would need to complete prior to signing up for the study, and requiring approval from their mothers. One additional participant was dropped from the sample during the data cleaning and analysis stage because of a duplicate id.

The remainder one hundred and fifty-four (154) women from the Satmar2 community participated in this study. Fifty-two percent of them were assigned to the Siddur (control) condition, and 48% of them were in the plain dress (treatment) condition. At the time of the study participants were on average 22.4 years old, with eight siblings, and 58.8% of them were married.

We look at balance in demographics across the two experimental arms on demographic variables. Supplementary Table S3 presents the number of observations, mean, standard error (in parentheses), and p-value of pairwise t-tests of a series of variables. These demographic characteristics are overall balanced across the two research arms. In order to run a F-test for joint significance of all the demographic variables, we replace the missing values in any given variable with the mean of that variable to arrive at a consistent number of observations. These results are presented in Supplementary Table S3.

Noncompliance. After learning about their treatment assignment and their assigned activity, thirteen (13) participants from the treatment condition withdrew from the study. These participants neither complied with their treatment assignment nor completed the survey. A further 22 participants from the treatment condition did not carry out the assigned task but did complete the survey. Overall, forty-seven percent (47%) of those who were assigned to the treatment condition did not comply with one or more portions of the study. Only five percent (5%) of participants assigned to the Siddur (control) condition did not complete their one-day activity after learning about their assignment. However, all these participants completed an endline survey. This stark imbalance in non-compliance suggests that we were successful in designing a counter-normative and challenging activity. This point is made directly by descriptive statistics from the outcome survey, averaged across condition: participants rated that other women believe that wearing expensive clothes is important as a 4.9 on a 7-point scale, even though they themselves rated high-end dressing to be on average 3.0 out of 7.

Importantly, we collect demographic data (i.e., age, family size, marital status, and self-reported relative community standing in income) for all 154 participants who took part in this study. Interestingly, the balance we observe in demographics between treatment and control does not change when we limit the sample to compliers (see Supplementary Table S4).

5.2 How does it feel to violate a strong community norm?

We first start by asking how the experience of violating a social norm made the participants in our sample feel. We find a substantial and significant impact of the treatment (the plain dress condition) on participants' experience relative to the control condition (β = 2.408, SE = 0.268, p < 0.01). On average, relative to participants in the Siddur condition, participants assigned to wear a plain dress report a substantially higher level of agreement with statements that they felt weird, not good, like they stood out, like people noticed something unusual or that people were judgmental (Table 1). The findings hold and are consistent with the results from our supplementary analyses using inverse probability weighting to account for missing values (Supplementary material 4). These results indicate that in addition to experiencing negative affect for deviating, participants assigned to wear the plain dress also felt that people noticed something unusual about them and judged them for that. The experience of violating the high-end clothing norm is salient and comes with a cost in the Satmar community in Brooklyn.

The treatment participants' discomfort with their assignment is reflected as well in the differential levels of non-compliance and the qualitative responses shared by participants. As mentioned in Section 5.1, non-compliance among treatment participants is much higher in the treatment condition (47%) as compared to the control condition (5%). This finding indicates the perceived difficulty and anticipated repercussions of the assigned activity.

Although the majority of participants in the Siddur condition reported that they were easily able to follow their activity's guidelines, this was not the case for participants in the treatment condition, even those who fully complied with the assignment. When treatment participants were asked about any obstacles they encountered in carrying out the activity, some explicitly reported encountering difficulty or feeling uncomfortable. Their comments about their experience ranged from relating a personal experience or emotions: “It was hard for me, but I followed the instructions.” or “I followed the instructions, however it was a terribly nerdy skirt, so I felt embarrassed wearing it.”, to them describing intervention from other family members: “I definitely encountered obstacles and my mother made me change outfits.”

Other comments by women in the treatment condition suggest that although they may not have carried out the activity as intended, they fully recognized what the activity was asking them to do (i.e., violate a social norm). They reported that they anticipated that the activity would have made them feel uncomfortable had they encountered other members of their community. For example, one participant said: “Yes I was able to follow being that I wore it for a short amount of time + didn't meet anyone that would make me feel uncomfortable.”, while another reported: “I was basically able to follow it. I did not have a chance to go out with it so much.” Resonating with these qualitative comments from the survey, the first author received calls from two separate women within a few hours of wearing the dress to ask if they could change because it bothered them to even wear the plain dress at home.

Overall, our quantitative and qualitative data demonstrate that the anticipation of and the actual experience of violating the high-end clothing norm is negative for our study participants.

5.3 Does an experience of deviance change attitudes toward deviance or perceptions of the self as a deviant?

We next explore whether deviating from a social norm in public changes one's attitudes toward deviance or about oneself as a deviant.

5.3.1 Attitudes toward deviance and toward helping others deviate

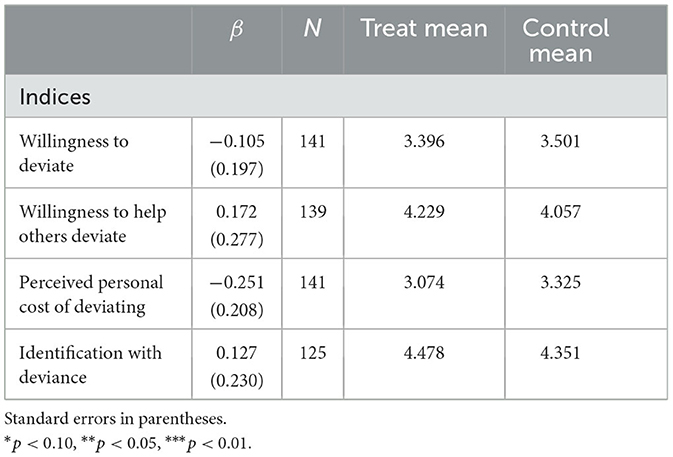

Overall, we find no evidence to suggest that deviating from the high-end clothing norm increases participants' willingness to deviate in the future or to help others to do so across a wide variety of related and unrelated counter-normative behaviors (Table 2).

5.3.2 Ideas about the self as a deviant

Our results suggest that this experience neither changes one's perception of the cost to self of deviating nor makes them more likely to view themselves as individuals who deviate (Table 2).

Overall, we do not see any evidence to suggest that engaging in counter-normative behavior in public makes one more willing to deviate again in the future or to help others to deviate. It furthermore does not influence our participants' perception of the cost of deviance to themselves, or their self-perceptions as deviants. These results are consistent with the results from our supplementary analyses using inverse probability weighting to account for missing values (Supplementary Table S9).

5.4 Does violating a strong community norm change personal attitudes toward the norm or perceptions of norm strength?

Our results suggest that even though there is no impact on participants' personal attitudes toward high-end clothing, violating the high-end clothing norm weakens participants' perception of the norm supporting high-end dressing (Table 3). More specifically, participants in the “plain dress” condition express less agreement when asked about whether women believe that wearing expensive clothes is important relative to participants in the Siddur condition (β = -0.481, SE = 0.240, p < 0.05). This result is also statistically significant when we look specifically at the compliers in our sample, i.e., our ToT analysis (Supplementary material 3).

Table 3. Personal views do not change, but some evidence for change in perception of community norms regarding high-end clothing.

5.5 Does violating a community norm change a person's pride in the community and its central tenets?

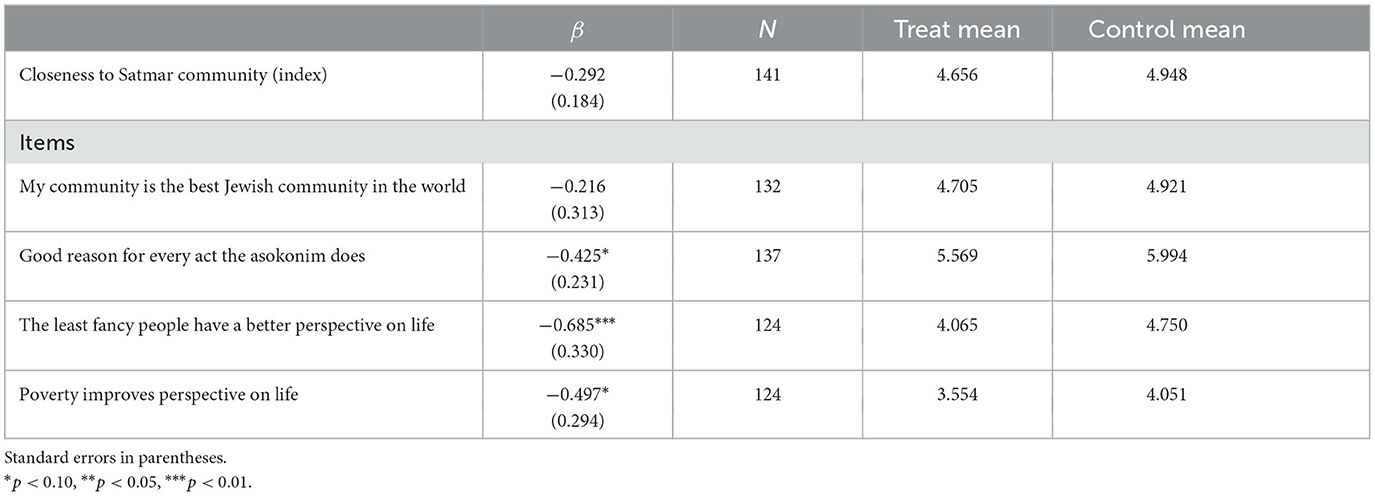

We now examine a different type of community perception—not of a community norm but of closeness to the community and agreement with some of the community's central ideas or tenets. Deviating from the high-end clothing norm led participants to report less adherence to the leaders of and the mainstream views of the Satmar community (Table 4). More specifically, participants in the treatment condition expressed less agreement than those in the control condition with the statement that there is a good reason for every act that the Asokonim does (the difference was associated with a p < 0.1). For both items measuring the community's central views on piety, participants assigned to violate the high-end clothing norm agreed less with traditional views that poverty and “less fancy” lives leads to more piety than participants assigned to carry the Siddur condition (Table 4). Only one of those items reached statistical significance at conventional levels, which is the decrease in the idea that the least fancy people have a better perspective on life (β = −0.685, SE = 0.330, p < 0.05). These results are consistent with the results from our supplementary analyses using inverse probability weighting to account for missing values (Supplementary material 4) and with our ToT analysis (Supplementary material 3).

5.6 Additional items

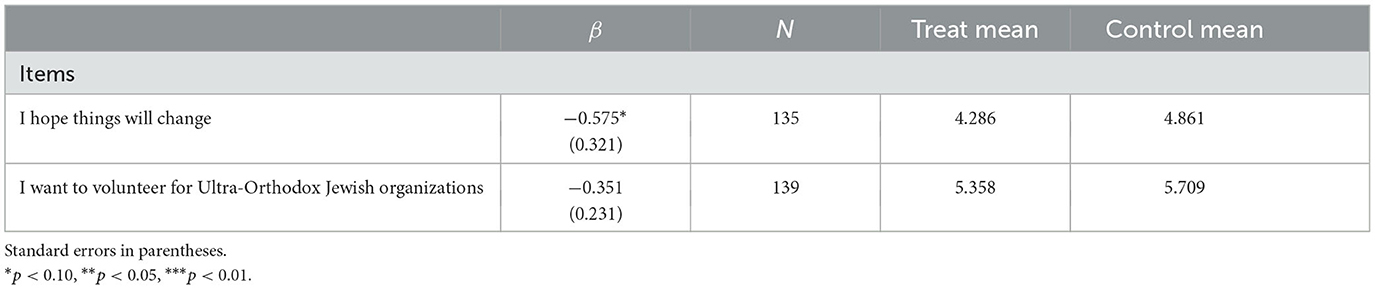

In our two additional items that were initially part of a composite, we find that treatment participants were less likely to hope that things would change for women and girls (please see Table 5; the difference was associated with a p < 0.1). The treatment did not affect willingness to volunteer for ultra-Orthodox community organizations. We down-weight the interpretation of the individual items since they were pre-registered as a composite—the composite shows no treatment effect (see Supplementary material).

6 Discussion

In one of the only field experiments (to our knowledge) to randomize a deviant act and to study the effects on the person deviating, we find that women's experience of deviation from the norm of high-end clothing in the U.S. Satmar community was strongly uncomfortable, but was not internalized as new attitudes or self-perceptions. We do find that the experience with deviance mostly affected women's perceptions of their community, in terms of their closeness to the community and to some of its central tenets, and the community norm of high end dressing.

Specifically, Satmar women who were asked to deviate for one day by choosing a “plain dress” to wear reported that they felt weird, less than good, like a sore thumb, and that people noticed and were judgmental. As an index, the size of this shift in their comfort in public is almost two and a half points on a seven-point scale, a large and significant effect. Qualitatively, they reported embarrassment and cutting their public appearance short to change their outfit. Our first author received a phone call from one married woman whose mother saw her on the street and told her to go home and change.

Although we observe a large and significant change in emotions and social perceptions in this relatively small sample, we do not observe large changes in these women's willingness to deviate or to help other deviants in the future, nor in their perceptions of the costs of standing out from the crowd. We also saw no change in the way that women perceived themselves, relative to women who were asked to do a normative task for the day (carry a prayer book). Given the negative and uncomfortable experience of deviating (and being asked to deviate, because the women who were asked and who did not comply are included in these analyses), one might expect that the women might see themselves as less of a deviant in the future, or perhaps they might be driven to rationalize their choice to participate by seeing themselves as more of a deviant, but we find no evidence of either change. We also find no change in their personal views of the high-end clothing norm.

Among the women who were asked to deviate, what we do find is a change in the way they perceive the community's norm of high-end dressing and the way they perceive their community more generally. Women assigned to treatment perceive nearly half a point reduction on the 7-point scale measuring the strength of Satmar women's belief in the importance of wearing expensive clothes—in other words, the norm is weakened in their eyes. Additionally, and surprising to us given the exploratory nature of these questions, women reported more “distance” from the community, in terms of stating less belief in the rationale of their political community leaders, and in one of the central tenets of Satmar culture, that poverty grants a person a better perspective on life. Other questions gauging their closeness to the community also showed decreases, although they were not significant.3

Thus, the story of the findings from this particular setting highlights that an experience of individual deviation seems to change perceptions of our context—its norms and our relationship to our community—over our perceptions of ourselves and of deviant actions themselves.

The results of this study help to map out a theory of community and social change that accounts for individuals' perceptions and social experiences that affect their decisions about whether to participate in such change. Below, we discuss these perceptions and processes including the anticipation of deviance, the challenge of deviating alone, and accumulated experiences with deviance.

6.1 Understanding compliance with a request to deviate

In order to trace the causal effects of deviance we randomly assigned the invitation to do so. A strength of our study that sets it apart is that we still collected data from people who declined this invitation, rather than treating them as missing values. We were unable to collect a great deal of demographic and descriptive data from each participant, but it was surprising to us that we found no differences demographically between people who accepted and who declined the invitation to deviate. For example, it would make sense if unmarried and poorer women declined, as they are anticipating the need to find a partner and may struggle more often to obtain high status in the community, respectively. But unmarried and married women, and high and low income women, declined to participate at comparable rates. Still, it remains a possibility that “non-compliers”, those who declined the invitation, represent a different group of people who are less open to deviance. Future research could focus on this very question—who among everyday people are more or less likely to deviate.

Another interesting aspect of our study design is that non-compliers did not participate in the full treatment of wearing a plain dress, but they were treated to the extent that they were invited to deviate in a way that they may not normally consider. Thus, the invitation was itself a form of reduced treatment. Our study design cannot accurately isolate the impact of this pre-consideration of deviance experienced by our non-compliers and our compliers. Qualitatively, we observed apprehension that led some women to say that they would not deviate. Perhaps some of this anticipation led to the differences in subsequent norm perceptions and community perceptions that we observed among our compliers and non-compliers and control participants, or perhaps this group of non-compliers were different from these other participants to begin with. Future research would do well to understand the anticipation of deviance and the effects of that anticipation, as a way to build a fuller theory of social change.

6.2 Deviating alone vs. together

The stated goal of this project was to better understand how ordinary people feel about and are changed by the experience of stepping out against conventions that are central to their community, as part of the project of understanding social change. We interpret the foregoing results to show how challenging it is for ordinary people to deviate, and how the experience is unlikely to build upon itself if it is so intensely negative (women indicated they did not identify with deviance or wish to engage with it or support it again). One interesting idea for future research is to test whether this is true for people who deviate as a group—who receive the social support of others as they step out against conventions. The current findings speak to the strength and stability of norms, even though we see that an individual experience with deviance produced a few small cracks in that stability—updated impressions of the norm and a slight distancing from the community. Are those cracks widened when people attempt deviance together?

6.3 Accumulated experiences with deviance

Longer-term research could also see whether small acts of deviation like the one we test in this study could build over time. The women in our study might argue that the experimental treatment was no small act—which might suggest another experimental design. It might be fruitful to think of deviance in terms of the foot-in-the-door vs. the door-in-the-face approach (Cialdini, 2021): might people continue to deviate if they build up with much more minor acts over time (e.g., carrying a non-designer bag with their designer dress), as opposed to a full rejection of the norm by dressing differently for an entire day? Although women stated in our study that they had no interest in future deviance, we don't know whether this experience did in fact lead to them experimenting with other ways of testing the boundaries of their social conventions. Future research would do well to follow norm-breakers through time after a deviation from a strong norm. It would also be interesting for future research to describe the personality traits, experiences, and contextual influences of everyday people who are willing to take the first step in this process by choosing to deviate.

We set out to identify a strong norm in a tightly-knit community, and we identified the Satmar Jewish community in Brooklyn as one such place. One criticism of this research might be that its lessons are limited by the unique nature of the context. One might argue that the presence of a research project (meaning, activity and survey requests from outsiders) was too foreign, or that the norms and community identity are unusually strong. In some ways, these criticisms are well-placed. The research stood out to our participants as something radically different from their everyday experience. Also, the Satmar community is a model of a “settled culture” (Swidler, 1986), where norms are not changing and the power dynamics of the community are all aimed at keeping the status quo in place. But while these characteristics distinguish the Satmar community, they hardly distinguish the community as unique. The community's focus on maintaining the status quo echoes many other such “settled cultures” with close social ties from around the globe that have been documented by political ethnographers (Swidler, 1986). Additionally, we wish to note that the experience of the women who actually deviated in many ways echoed Stanley Milgram's secular research assistants who cowered on the subway after inappropriately asking someone for their seat. Ultimately, whether our findings are limited by our setting is an empirical question, but we note that nothing about the dynamics of strong norms and norm violators that we observe here seems particularly Satmar. We hope that this study inspires others—grounded in a rich understanding of a community and its norms and people—to trace out the experiences of ordinary people who try out something extraordinary.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Princeton University Human Subjects Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

NM-Y: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Writing—original draft. SK: Formal analysis, Writing—original draft. EP: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing—original draft, Methodology.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funding is gratefully acknowledged from the Center for Human Values at Princeton University.

Acknowledgments

Without Robin Gomila this paper would not have happened. We thank Alex Sanchez, Sydney Garcia, members of the BLP lab past and present, and the field research assistants who worked in the community with NM-Y.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsps.2023.1290743/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^A Hasidic filter on the internet only allows access to bank accounts and billing websites, as well as Hasidic news sites such as Jewish Daily News. Some shopping is allowed, but the filter blocks immodest items such as women's underwear.

2. ^Less than 2% of women contacted were from neighboring Hasidic communities who shared the Satmar norm of high-end dressing. Their numbers are small enough to prevent any heterogeneous analyses of effects.

3. ^Women assigned to treatment also were less hopeful about change for women and girls in their community, although this finding was weak and not pre-registered as single outcome.

References

Angrist, J. D., and Pischke, J. S. (2009). Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist's Companion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Asch, S. E. (1952). “Group forces in the modification and distortion of judgments,” in Social Psychology, ed S. E. Asch (Prentice-Hall, Inc.), 450–501.

Chaiken, S., Wood, W., and Eagly, A. H. (1996). “Principles of persuasion,” in Social Psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles, eds E. T. Higgins, and A. W. Kruglanski (New York, NY: Guilford Press), 702–742.

Chang, L. J., Smith, A., Dufwenberg, M., and Sanfey, A. G. (2011). Triangulating the neural, psychological, and economic bases of guilt aversion. Neuron 70, 560–572. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.056

Cialdini, R. B., and Goldstein, N. J. (2004). Social Influence: Compliance and Conformity. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 55, 591–621. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142015

Cialdini, R. B., and Trost, M. R. (1998). “Social influence: social norms, conformity and compliance,” in The Handbook of Social Psychology, Vols. 1-2, 4th Edn. (McGraw-Hill), 151–192.

Cialdini, R. B. (2021). Influence, New and Expanded: The Psychology of Persuasion. New York, NY: Harper Business.

Dannals, J. E., and Miller, D. T. (2017). Social norm perception in groups with outliers. J. Exp. Psychol. 146, 1342. doi: 10.1037/xge0000336

Deutsch, N. (2009). The forbidden fork, the cell phone holocaust, and other haredi encounters with technology. Contemp. Jewry, 29, 3–19. doi: 10.1007/s12397-008-9002-7

Deutsch, N., and Casper, M. (2021). A Fortress in Brooklyn: Race, Real Estate, and the Making of Hasidic Williamsburg. Yale University Press.

Durkheim, E. (1938). The Rules of Sociological Method, 8th Edn. Eds S. A. Solovay, J. H. Mueller, Trans. by G. E. G. Catlin. New York, NY: The Free Press.

Festinger, L. (1950). Informal social communication. Psychol. Rev. 57, 271–282. doi: 10.1037/h0056932

Festinger, L., and Carlsmith, J. M. (1959). Cognitive consequences of forced compliance. J. Abn. Soc. Psychol. 58, 203.

Gerber, A. S., and Green, D. P. (2012). Field Experiments: Design, Analysis, and Interpretation. New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Gomila, R., Shepherd, H., and Paluck, E. L. (2023). Network insiders and observers: who can identify influential people? Behav. Public Policy 7, 115–142. doi: 10.1017/bpp.2020.8

Gomila, R., and Clark, C. S. (2019). Missing Data in Experiments: Challenges and Solutions. New York, NY.

Guilbeault, D., and Centola, D. (2021). Topological measures for identifying and predicting the spread of complex contagions. Nat. Commun. 12, 4430. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24704-6

Jetten, J., Iyer, A., Hutchison, P., and Hornsey, M. J. (2011). “Debating deviance,” in Rebels in Groups: Dissent, Deviance, Difference, and Defiance, eds J. Jetten, and M. J. Hornsey (Hoboken, NJ: JohnWiley and Sons), 117–134.

Jetten, J., and Hornsey, M. J. (2011). Rebels in Groups: Dissent, Deviance, Difference, and Defiance. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons.

Jost, J. T., Banaji, M. R., and Nosek, B. A. (2004). A decade of system justification theory: Accumulated evidence of conscious and unconscious bolstering of the status quo. Politic. Psychol. 25, 881–919.

Keren-Kratz, M. (2017). Rabbi Yoel Teitelbaum—the Satmar Rebbe—and the rise of anti-zionism in American Orthodoxy. Contemp. Jewry 37, 457–479. doi: 10.1007/s12397-017-9204-y

Kranzler, G. (1995). Hasidic Williamsburg: A Contemporary American Hasidic Community. Jason Aronson, Incorporated.

Kuran, T. (1997). Private Truths, Public Lies: The Social Consequences of Preference Falsification. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Link, B. G., and Phelan, J. C. (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 27, 363–385. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363

Major, B., and O'Brien, L. T. (2005). The social psychology of stigma. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 56, 393–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070137

Malovicki-Yaffe, N. (2020). Capabilities and universalism–an empirical examination: the case of the ultra-orthodox community. J. Hum. Dev. Capabil. 21, 84–98. doi: 10.1080/19452829.2019.1705259

Malovicki-Yaffe, N., and Shafir, E. (2023). Poverty, Piety, and Pride: How ultra-Orthodox Jews Living In Poverty Construct Their Identity. Working paper. Tel Aviv University.

Malovicki-Yaffe, N., Solak, N., Halperin, E., and Saguy, T. (2018). “Poor is pious”: distinctiveness threat increases glorification of poverty among the poor. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 48, 460–471. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2342

Markus, H. (1977). Self-schemata and processing information about the self. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 35, 63–78. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.35.2.63

Milgram, S. (1965). Some conditions of obedience and disobedience to authority. Hum. Relat. 18, 57–76.

Milgram, S., and Sabini, J. (1978). “On maintaining social norms: a field experiment in the subway,” in Advances in Environmental Psychology, Vol. 1, eds A. Baum, J.E. Singer, and S. Valins (Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum), 31–40.

Miller, D. T., and Prentice, D. A. (1996). “The construction of social norms and standards,” in Social Psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles, eds E. T. Higgins, and A. W. Kruglanski (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 799–829.

Monin, B., and O'Connor, K. (2011). “Reactions to defiant deviants: deliverance or defensiveness?,” in Rebels in Groups: Dissent, Deviance, Difference and Defiance (Wiley-Blackwell), 261–280.

Monin, B., Sawyer, P. J., and Marquez, M. J. (2008). The rejection of moral rebels: resenting those who do the right thing. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 95, 76. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.95.1.76

Paluck, E. L., and Shepherd, H. (2012). The salience of social referents: a field experiment on collective norms and harassment behavior in a school social network. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 103, 899. doi: 10.1037/a0030015

Paluck, E. L., Shepherd, H., and Aronow, P. M. (2016). Changing climates of conflict: a social network experiment in 56 schools. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 113, 566–571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1514483113

Plous, S. (2023). Norm Violation Assignment. Social Psychology Network. Available online at: https://www.socialpsychology.org/teach/normviolation.htm (accessed September 7, 2023).

Prentice, D. A. (2012). “Social norms and the promotion of human rights,” in Understanding Social Action, Promoting Human Rights, eds R. Goodman, D. Jinks, and A. K. Woods (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Prentice, D. A., and Miller, D. T. (1993). Pluralistic ignorance and alcohol use on campus: Some consequences of misperceiving the social norm. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 64, 243–256. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.64.2.243

Roberts, S. (2011). Kiryas Joel, N.Y., Lands Distinction as Nation's Poorest Place. The New York Times. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/21/nyregion/kiryas-joel-a-village-with-the-numbers-not-the-image-of-the-poorest-place.html (accessed November 22, 2023).

Schwartz, S. H. (1973). Normative explanations of helping behavior: a critique, proposal, and empirical test. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 9, 349–364. doi: 10.1016/0022-1031(73)90071-1

Snyder, M. (1979). “Self-monitoring processes,” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 12 (Academic Press), 85–128.

Stolzenberg, N. M., and Myers, D. N. (2022). American Shtetl: The Making of Kiryas Joel, a Hasidic Village in Upstate. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Swann, W. B., and Bosson, J. K. (2010). “Self and identity,” in Handbook of Social Psychology, Vol. 1, 5th Edn, eds S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, and G. Lindzey (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons Inc.), 58–628.

Swidler, A. (1986). Culture in action: symbols and strategies. Am. Sociol. Rev. 51, 273. doi: 10.2307/2095521

Tankard, M. E., and Paluck, E. L. (2016). Norm perception as a vehicle for social change: vehicle for social change. Soc. Iss. Policy Rev. 10, 181–211. doi: 10.1111/sipr.12022

Keywords: deviance, social norms, norm violations, field experiment, social change, self

Citation: Malovicki-Yaffe N, Khan SA and Paluck EL (2023) The social and psychological effects of publicly violating a social norm: a field experiment in the Satmar Jewish community. Front. Soc. Psychol. 1:1290743. doi: 10.3389/frsps.2023.1290743

Received: 08 September 2023; Accepted: 06 November 2023;

Published: 12 December 2023.

Edited by:

Adam M. Croom, Bethany College, United StatesReviewed by:

Matthew Hibbing, University of California, Merced, United StatesDruann Heckert, Fayetteville State University, United States

Copyright © 2023 Malovicki-Yaffe, Khan and Paluck. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nechumi Malovicki-Yaffe, bnlhZmZlQHRhdWV4LnRhdS5hYy5pbA==

Nechumi Malovicki-Yaffe1*

Nechumi Malovicki-Yaffe1* Sana Adnan Khan

Sana Adnan Khan Elizabeth Levy Paluck

Elizabeth Levy Paluck