94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Soc. Psychol., 11 December 2023

Sec. Intergroup Relations and Group Processes

Volume 1 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frsps.2023.1278671

Oscar Ybarra1*

Oscar Ybarra1* Todd Chan2

Todd Chan2The present research presents a model of how individuals relate to their personal social networks (i. e., spouse, children, other family, friends) by considering the degree to which the individual's needs for communion and agency are satisfied by these relations. The model proposes four prototypical configurations of the individual and their social network, which reflect different combinations of the high and low poles of communion and agency. The squad model is then applied to loneliness, an outcome the literature has considered predominantly from the perspective of deficits in the communion and relatedness domain with little attention paid to people's need for agency. Clustering analyses showed that people's networks can be characterized as proposed by the squad model, but also that loneliness varies as a function of both the level of communion and agency represented by each prototype. The findings thus contribute to our understanding of loneliness, but the framework is much broader and can be applied to varied outcomes. The model also has several implications for research on social networks as well as models of relationship processes.

It is hard for the individual to escape the group even when they are not part of a cult. Everywhere you look there are people in groups, whether it is being part of a family, neighborhood get-together, church, book club, sorority, study group, softball team, or a task force at work. Groups of course differ on many levels, but it is remarkable how much of what people do takes place in the company of others as part of groups. And groups of course matter because they operate as social forces through the patterns of interactions and relationships they create, as well as roles, demands, and expectations placed on members.

In social psychology, in addition to focusing on the important role groups and group identities play in influencing behavior, there also exist varied perspectives on the individual acting as a causal force in shaping their own lives (e.g., Maslow, 1954; Atkinson et al., 1960; Bandura, 1982; Carver and Scheier, 1998; Ryan and Deci, 2000; Duckworth et al., 2011). The anthropologist, Bronislaw Malinowski, conceived of the individual as the fountain from which various groups and societal forces spring. Yes, groups are important. But the groups themselves can be shaped by the needs of the individual (Malinowski, 1939).

We take this idea of a dialectic between the group and the individual as the starting point for the present analysis and research. Social forces matter in shaping behavior, but we want to reserve a role for the individual. That is, the individual can play a part in the shape their social surroundings take, and depending on what shape they take, can either facilitate or hinder the outcomes they experience in life.

Although we can identify various groups that exist in society, one that is less easily labeled, and has historically received less attention in social psychology, is a person's social network. By social network we don't mean the far-flung set of social connections people accumulate on social media, which can include many hundreds of individuals. Instead, we are referring to an individual's personal social network (PSN), which we liken to their support squad, that set of persons that occupies the emotional and social spaces in which that individual experiences life (Weiss, 1973). As shorthand, we can conceive of these spaces as concentric circles that radiate from the center of a page, where the individual or “ego” is located (Antonucci, 1986). The closest social relations are in the first circle radiating outward from the individual. The next circle radiating outward is slightly larger but still consists of network members thought of as important to the individual.

The persons that occupy the innermost circle will likely include a spouse or partner, children, and other very close family members and friends, and this innermost part of people's networks varies in size from 3–7 (Antonucci, 2001; also see Wenger, 1997). House and Kahn (1985) concluded that gathering information about a person's support network yields diminishing returns between 5 and 10 persons. Using a different conceptual and empirical approach, Dunbar suggested that this inner core consists of up to 5 persons (Dunbar, 2014). If tough times visit the individual, these intimates will be available to provide the strongest source of emotional support (Wenger, 1997). Those persons occupying the second circle of the individual's PSN, although a little more removed, are still close and available to provide support, many times meaningful instrumental support. The number of individuals at this emotional distance, the sympathy group, is likely 12–15 but can range up to about 50 (Dunbar, 2014). People's social networks can radiate even further out, but in this paper, we focus on the two layers of relations closest to the individual.

Although PSNs may lack the coordination of traditional groups such as a sports team or work group in which an “all hands-on deck” alert can get everyone rowing in the same direction, from the perspective of the individual the members of the PSN can be called upon for various social or instrumental exchanges. PSNs thus matter because they serve as the basis from which people draw most of their social support, whatever that level of support may be (Antonucci, 2001). But as noted earlier, we want to leave some room for considering how the individual relates to their PSN and suggest different roles they can play in their social relations.

A topic that can broaden our thinking about how individuals relate to their PSN is that of the basic themes that undergird social behavior–communion and agency (Bakan, 1966). In our research, for example, we have studied how the communion and agency dimensions affect people's judgments of others and themselves (e.g., Ybarra, 2002; Ybarra et al., 2008, 2012; Han et al., 2016; Chan et al., 2018). These dimensions are a bit protean. In addition to communion and agency (Bakan, 1966; Wiggins, 1991), they are known as warmth vs. competence (Fiske et al., 2007), relatedness vs. individuality (Guisinger and Blatt, 1994), interdependence (collectivism) vs. independence (individualism) (Markus and Kitayama, 1991; Triandis, 2018), relatedness vs. autonomy/competence (Ryan and Deci, 2000), affiliation vs. achievement (McClelland, 1985), intimacy vs. power (McAdams, 1985), affiliation vs. dominance (Leary, 1957; Horowitz et al., 2006) and sociotropy vs. autonomy (Beck, 1983). This likely reflects the specific terrain researchers in different fields have had to traverse. Regardless, from personality through social and cultural psychology to developmental and clinical psychology, researchers have uncannily observed related aspects of these organizing themes.

Communion and agency recur because they likely reflect two basic challenges humans face and have faced for millennia. Using Hogan's (1983) pithy way of putting it, one is the need to get along with others, and the other is the need to get ahead. That is, as researchers have indelibly stamped into our collective knowledge, we are social, and we need to have supportive relationships with others (Baumeister and Leary, 1995). But as also highlighted by other psychologists, the individual has their personal strivings, wants choice, and seeks growth and distinction (Maslow, 1954; Atkinson et al., 1960; Bandura, 1982; Ryan and Deci, 2000; Brim, 2018).

In terms of the present research, people seek both communion and agency in their lives. But given our group living nature, the pursuit of these goals occurs in the context of one's personal social networks. PSNs provide much support and are likely the basis for fulfilling much of people's communion and relational needs. But we propose that PSNs also play a role in helping support an individual's agency related pursuits.

We can conceive of communion and agency as operating as antagonistic factors so that more of one means less of the other (for a recent example see Milyavsky et al., 2022). However, communion and agency appear to be orthogonal dimensions. The first time the first author came across this, he was working with his graduate advisor and colleagues examining conflict resolution styles, comparing people from Mexico and the U.S. Part of the theoretical framing for the research used the cultural distinctions of “independence” (related to agency) vs. “interdependence” (related to communion), and the assumption was that the dimensions were antagonistic or compensatory. But that is not what the findings showed. The Mexican sample scored higher on interdependence than the Americans, as anticipated, but they also scored higher on a measure of independence (Gabrielidis et al., 1997). Thus, being high on one dimension does not preclude being high on the other. In their meta-analyses, Oyserman et al. (2002) confirmed this outcome among several other studies, showing that interdependence need not crimp independence and vice versa.

The orthogonality of communion and agency is just the starting point in this analysis because the dimensions can be crossed. What we would like to propose is that by doing so we can derive distinct ways in which individuals relate to their personal social networks, which has implications for a host of personal outcomes.

Social networks vary in structure (e.g., number of people, presence of best friends, frequency of interaction, density, physical proximity), and depending on the configuration of these structural variables, different profiles can be generated. Examples include networks that differ in number of strong and weak ties (Granovetter, 1973), roles and interconnectedness to focal individuals (Wellman, 1979), dominance of kin relations (Giannella and Fischer, 2016), and others with slightly different demarcations (kin, family-intensive, friend-focused, and diffuse ties; Litwin and Landau, 2000). Approaches taking a life-span perspective have uncovered related typologies, such as diverse networks, family-focused networks, friend-focused networks, and restricted networks (e.g., Fiori et al., 2007, 2008). However, a consideration of the extent to which an individual's network relations facilitate satisfaction of communion and agency needs can also provide insights into how an individual relates to their PSN. As shown in Figure 1, we focus on four combinations of the low and high poles of each dimension.

Figure 1 depicts the individual and their closest relations. These are parents, spouse, children, and friends. Q4 (empowered) individuals operate in that quadrant where network relations are not only warm and supportive–where communion needs are met–but individuals also exercise their agency and choice. The proposed view of Q4 individuals shares features with proposals from attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969; Ainsworth et al., 2015), close relationship effects on thriving (Feeney and Collins, 2015; Lee et al., 2018), and relationships motivation theory (Deci and Ryan, 2014). Network members are available for social contact and are responsive, but they are also supportive of the individual's need to be their own person and establish themselves in productive and fulfilling activities. The individual thus feels free to explore on their own and to separate themselves from network members when necessary to carry out their own pursuits. But these individuals are not simply beneficiaries; they choose to return and maintain their relationships and to give back.

Q1 (separated) represents an individual who focuses on being separate from others and protecting their agency. We envision three ways in which individuals in Q1 end up with such a PSN. For some, their network relations (e.g., family) are modestly supportive but focus on encouraging the individual's separation and self-sufficiency. This is consistent with conceptions of independence and related socialization differences in cultural psychology (Markus and Kitayama, 1991). A slightly different reason for a Q1 configuration is that an individual, despite having the potential for supportive relationships, is so focused on their personal goals that they deemphasize their relationships. Either way, because close and supportive relations depend on frequent interaction and mutual dependencies, with time a focus on staying separate or on personal goals diminishes the quality of relations in one's PSN (Canary and Stafford, 1992; Burt, 2000; Oswald et al., 2004; Roberts and Dunbar, 2011; Ogolsky and Bowers, 2013). A third way in which individuals can end up with a Q1 configuration is when they experience deleterious interactions and relationships with network members. In this case, separation, and distance result from the necessity to protect one's mental and physical wellbeing. Regardless of process, individuals in a Q1 configuration can end up with high agency and doing things mainly on their own terms.

Q2 (neglected) depicts an individual who is unable to fulfill their communion needs in their network. Such individuals will likely feel ignored, neglected, and uncertain about the support they can get from their PSN. They have a social hunger and want warm relations with others but are likely anxious and keenly focused on signs of support and positive regard (cf. Murray et al., 2006). In addition to not having one's communion needs met, they have diminished agency for different reasons. The individual may silence themselves and go along with others' wishes in terms of how to spend time together if an invitation is made. Or because they are concerned with not straying too far, they remain available and vigilant for any sign of inclusion. This likely results in losing opportunities to cultivate one's agency as well as to build alternative, supportive relations. Uncertainty has a way of leaving people feeling stuck (Birrell et al., 2011), and with time feeling unfulfilled on both dimensions. But this configuration can also result when a person has little extant agency and the skills that undergird it, so they rely on others to get things done. Because having one's own sphere of competence can make a person instrumental to others, the lack of it makes them less attractive social partners (cf. Leary et al., 2014). With time their lack of instrumentality, as well as their dependency (Berkowitz, 1969), may limit the creation of reciprocal relationships.

Unlike Q2 (neglected) individuals who are more interested in acquiring warm relations, Q3 (muted) individuals have them in place. But their agency is low. This could simply be because they focus more on relational than personal goals. But there are other dynamics. It can be that the relations in their social network put limits on their individual and agentic pursuits. For example, when a living situation depends on both partners working to maintain a household, or when a child requires care from parents, there are real limits to one's personal pursuits (cf. Perry-Jenkins and Gerstel, 2020). Immersive interdependencies can constrain personal interests and self-strivings. Finally, such a configuration can occur because network members, despite being warm, can also have strong opinions and wield influence in terms of what the individual can and should do (Cohen and Lemay, 2007).

This brief discussion highlights different prototypes or patterns that a personal social network can take from considering the individual's recurring needs for communion and agency. We have discussed some routes through which people end up with the different PSN configurations, but there are likely others. Regardless, these PSN configurations should have implications for various outcomes. Here we study their consequences for loneliness.

Loneliness refers to perceiving that one is isolated from others (Hawkley and Cacioppo, 2010), a judgment based on a subjective assessment between currently achieved versus desired relationships (Peplau and Perlman, 1982). Thus, people can differ in the actual number of relationships in their lives, but based on their personal standards feel more or less lonely (Perlman and Peplau, 1981).

Loneliness is an outcome with far reaching psychological and physical health consequences. Mental health problems associated with loneliness include, for example, higher depressive symptomatology, social anxiety, impulsivity, thoughts of suicide, and cognitive decline, whereas physical issues include increased blood pressure, elevated HPA activity, reduced immunity, and obesity (for a review see Hawkley and Cacioppo, 2010; Cacioppo S. et al., 2015). In an April 30, 2023, article in the New York Times, the United States Surgeon General, Murthy (2023), warned about the devastating effects of loneliness in the United States, which he characterized as an epidemic.

Research on loneliness has progressed immensely over the last two decades. We now understand, for example, that anyone can experience loneliness at different times in their life (Andersson, 1998; Cacioppo S. et al., 2015). We also know that the experience of loneliness is influenced by an individual's social cognition (Peplau and Perlman, 1982), which may be inclined to see others as warm and caring or cold based on current preferences for social contact and prior relational experiences (Cacioppo J. T. et al., 2015). There is also the realization that loneliness is not a singular phenomenon but can be differentiated based on emotional closeness, such as lack of support from close others, but also from feeling that one is generally not in tune with others or does not have a group to belong to Hawkley et al. (2005).

Despite the expansion of knowledge on loneliness, avenues exist for adding to what we know. Specifically, most of the theoretical framing on loneliness focuses on the communion dimension and associated relational needs. Individuals who perceive that they are lacking supportive relationships, not necessarily a specific number of them, tend to experience greater loneliness (Perlman and Peplau, 1981). But we would like to propose that the other recurring need in people's lives, agency, and its associated goals for self-direction, choice, and personal control, should also matter for the experience of loneliness. Indeed, recent research has found statistical relationships between agency related constructs and the experience of loneliness (Li et al., 2019; Henning et al., 2022). But what should also matter for understanding loneliness is the simultaneous consideration of people's communion and agency needs.

When we consider both communion and agency needs, we can apply the squad model to make predictions about the experience of loneliness. For individuals in Q4 (empowered), warm and supportive relations not only support a sense of interpersonal efficacy (McAvay et al., 1996), where the individual can work to restore gaps in their communion needs, but it is likely that Q4 individuals will also be buffered from feeling lonely because their current relations are supportive of their choice and agency. From very early on in infancy, feeling secure in one's relationships–that they are responsive and supportive–allows a child to separate themselves from adults to explore and tackle new challenges, reinforcing both attachment and exploratory needs (Bowlby, 1969). For Ryan and Deci in the context of self-determination theory, this is an interrelated process (maintaining close relationships and mastering the environment) that becomes elaborated and continues throughout life (Ryan et al., 2015). Older adults, for example, report greater self-efficacy and control the greater the perception of available support (Lang et al., 1997). As Antonucci notes, “it is the cumulative expression of support by one or several individuals to another that communicates to the target person that he or she is an able, worthy, and capable person” (p. 442). In addition to having relationships where one's agency is supported, a person's pursuit of skills, status, and distinction will make them attractive to other potential social partners (Leary et al., 2014). Here, it is one's agency and related instrumentality that facilitates additional social opportunities. Thus, Q4 individuals should report the lowest loneliness because their relationships provide support when needed and are accepting of who they are, and the individual's agency makes them attractive social partners.

At the other extreme are Q2 (neglected) individuals; they lack warm and supportive relationships, which is related to loneliness (Russell et al., 1980), but these individuals are also likely to remain close and vigilant for social opportunities. Because of limited time and energy, this can lead to stagnation in experiences and skills that add to one's agency. Some Q2 individuals may also prefer to rely on others for making decisions and solving personal problems. Done to an extreme, this behavior and the associated inferences of low agency it suggests should make them less attractive to network members. Either way, this likely leaves Q2 individuals with the greatest experience of loneliness because their current situation fails to meet both their needs for communion and agency, leaving them with few resources to address stresses or new opportunities in life.

Q3 (muted) individuals have high communion and low agency. One reason for this situation can be too great a focus on relational goals, which could be because of duties (family, children) and other interdependencies, or because of personal preferences. To the extent that these individuals can provide others with support, they should be supported in return. But a lack of energy put toward personal goals and cultivating one's agency is itself related to loneliness (Li et al., 2019; Henning et al., 2022). This suggests they could experience loneliness even in the context of warm relations, a possibility suggested in the loneliness literature, although usually explained in terms of perceived discrepancies between current and desired relations (Perlman and Peplau, 1981). A related reason Q3 individuals can experience loneliness has to do with the quality of their relationships (Perlman and Peplau, 1981). As Cacioppo S. et al. (2015, p. 241) state, differing slightly from Perlman and Peplau, “it's not the quantity of friends, but the quality of significant friends/confidants that counts”. We propose, though, that quality needs further parsing. Some Q3 individuals may have their communion needs supported, suggesting quality, but they do not get support for their agency, or are not allowed much voice, which suggests lower relational quality. Again, current conceptions of loneliness focus primarily on the communion or relatedness dimension.

Q1 (separated), that prototypical lone wolf configuration, indicates high levels of agency but low communion. If we just focused on the communion dimension, the implication would be that because relationships are minimized, these individuals should experience much loneliness, as much as those in Q2. However, the presence of agency and choice suggests a couple of things that might mitigate loneliness. Being independent and self-sufficient can result in adding to one's personal resources. That is, after cultivating skills and becoming more comfortable with doing things on one's own, such individuals could place themselves in situations that further challenge and grow their sense of agency. The lack of supportive relationships does matter, but the fact that one's agency has been cultivated may buoy these individuals in situations where one would reach out to others for help. Thus, for different reasons, Q1 (separated) and Q3 (muted) should be associated with some loneliness but not to the same level as individuals in Q2 (neglected).

This study used data from TILDA, the Irish Longitudinal Study on Aging, which was conducted between October, 2009 and February, 2011 (Kearney et al., 2011; Whelan and Savva, 2013). Even though the study is almost a decade old, the data are relevant because we focus on the closest personal relationships available to people: spouse, children, other family members, and close friends. As we note below, the maximum number of close relatives and friends reported by participants is 47, which aligns with estimates of the number of people likely to inhabit the innermost aspects of individuals' PSNs, a number that reflects cognitive, affective, and time constraints (Dunbar, 2014). Thus, although the creation and expansion of social network platforms may allow for numerous, far- flung connections, most of this growth in social networks will likely be on the periphery and not the core of people's PSNs. This is the case because there is a limit to the energy and resources one can put into social relations, time and energy that is more likely to be invested in those relations one can depend on and has historically depended on.

The study is based on a nationally representative sample (8,175 individuals and 329 spouses; 3780 male; 4724 female in total sample) focusing on individuals 50 years and older (range 49–80; M = 62.97, SD = 9.407 for total sample). A total of 90.4 of the participants were born in Ireland, and no information is available about race or ethnicity. The study collected extensive information on people's lives, including economic circumstances, reports on health, social relationships, employment, demographics, and various psychosocial and mental health variables such as depression, cognitive functioning, and our measures of interest. Participants were interviewed at home and completed additional surveys that were returned to the researchers. Based on the number of targeted households, the completion rate for the interview portion of the study was 62, and 84% for the survey portion (Kearney et al., 2011; Whelan and Savva, 2013). The participants had a median education level of 3.00 on a scale running from 1 = some primary (not complete) to 7 = post-graduate/higher degree. 3.00 corresponds to an intermediate/junior/group certificate or equivalent. Most were married (67.6%) and had children who were no longer living in the household (73.9%). Given the focus on personal social networks, which included judgments of support from a spouse and children, the sample was limited to married individuals who had living children (N = 4,723; N = 5,522 for imputed cluster analysis).

TILDA used a 5-item measure adapted from the UCLA loneliness scale (Russell, 1996) to assess the extent to which individuals felt lonely. Example items included: “How often do you feel you lack companionship?” and “How often do you feel isolated from others?” These were scored: 1 = often, 2 = some of the time, and 3 = hardly ever or never. One item was negatively worded, so it was reverse-coded and then averaged along with the other four items (Cronbach's alpha = 0.77), so that higher scores reflect greater loneliness (M = 1.31, SD = 0.39).

Measures of relationship support and strain were used to assess the extent to which people had their communion needs met (Schuster et al., 1990). Three items assessed the degree to which these relationships served as sources of support. These items were: How much does he/she really understand the way you feel about things?; How much can you rely on him/her if you have a serious problem?; and How much can you open up to him/her if you need to talk about your worries?. Four additional items assessed strain from these same relationships. These were: How much does he/she make too many demands on you?; How much does he/she criticize you?; How much does he/she let you down when you are counting on him/her?; and How much does he/she get on your nerves?. The seven questions were answered on 4-point scales (1 = a lot, 4 = not at all) separately for spouse, children, other family members, and friends for a total of 28 items (Cronbach's alpha = 0.87). Relevant items were reverse-scored, and then all were summed and averaged, so that higher scores mean higher satisfaction of communion needs (M = 3.37, SD = 0.37).

TILDA contained several survey items that assessed different aspects of how participants view their lives. Of these, six were relevant to agency and whether participants felt they could choose, control, and direct their lives. Care was taken not to include sense of control items that were linked to the individual's finances, age, and health. The six items were: “I feel that what happens to me is out of my control,” “I feel free to plan for the future,” “I can do the things that I want to do,” “I feel that I can please myself in what I can do,” “I choose to do things that I have never done before,” and “I feel that life is full of opportunities.” The items were answered on 4-point scales that ranged from 1 = often to 4 = never. The positively worded items were reverse-scored, and then all items were summed and averaged (Cronbach's alpha = 0.69), with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction of an individual's agency needs (M = 3.26, SD = 0.49).

In the regression analysis, we controlled for factors relevant to participants' communion and agency needs, as well as loneliness. These included gender, age, and education level as described above. Gender is relevant because women tend to receive higher quality support than men on average from a more diverse set of social relations (Antonucci, 2001; Fiori et al., 2007, 2008), and age is related to the structure of social relations but also their quality (Carstensen et al., 1999; Huxhold et al., 2013). Financial circumstances (measured as gross total assets quintiles) and education are relevant to agency in that they contribute to higher SES, reflecting as well as facilitating the cultivation of more opportunities and thus a sense of control in one's life (Lachman and Weaver, 1998; Taylor and Seeman, 1999; Kraus et al., 2009). We also controlled for health status, indexed by the number of chronic health conditions reported. Health status is important because it should affect people's perceptions of their life being under their control, as well as the ability to pursue relational goals, as a greater number of health conditions predicts declines in social engagement (Huxhold et al., 2013). Seventeen chronic health conditions were assessed. Examples included high cholesterol, diabetes, a history of heart-related conditions, cancer, cirrhosis of the liver, and arthritis (Santini et al., 2019). The participants indicated “yes” or “no” to whether they had received such a medical diagnosis. The chronic health conditions were counted for each participant, with totals ranging from 0 to 10 (M = 1.58, SD = 1.46). We also controlled for participants' ability to enact instrumental activities of daily living (IADL's), such as shopping for groceries and taking medications. IADL's matter because, like health status, the ability to perform basic day-to-day tasks should affect the degree to which a person can socially engage with others (Curl et al., 2014). The IADL measure was a count of up to five disabilities.

Finally, we also controlled for depression and the number of social network members reported by participants. The experience of depression is relevant to loneliness (Cacioppo et al., 2006). Depression was assessed with the C-ESD (Radloff, 1977), which consists of twenty items that referred to participants' experiences in the last week prior to taking the survey. The items were scored on 4-point scales that ran from 1 = rarely or none of the time to 4 = all of the time (five to seven days). Positively worded items were reverse-scored. Then all the items, save for one that referenced feeling lonely, were averaged so that higher scores represent greater depression (Cronbach's alpha = 0.86; M = 1.26, SD = 0.34). We also controlled for the number of close relatives and friends reported by participants. This matters because the number of close friends and confidants can predict support given (Stokes, 1985) and loneliness (Russell et al., 1980). The number of reported close relatives and friends ranged from 0 to 47.

We used a three-step analytic approach to test the effect of the degree to which people's communion and agency needs, and their product, were met, and their effect on loneliness. First, we performed cluster analysis to determine if the data allow for classification according to the prototypes proposed in the introduction, that people's PSNs can be characterized by one of the four quads of the squad model. For this, we used as criterion variables people's level of communion and agency. Then we used ANOVA to assess differences in loneliness across clusters. Finally, we tested the robustness of the solution by conducting regression analysis controlling for relevant covariates.

Given the proposals of the squad model, as well as the theoretical constraint that individuals in each quadrant will inhabit only one type of PSN, we used k-means clustering. To use as much of the study data as possible, we imputed the data for the criterion variables of communion and agency, and loneliness using the median (N = 5,522). The next step was to standardize the criterion variables. We then stipulated four clusters in K-means cluster analysis based on a combination of theory and metrics from elbow and silhouette analyses.1

As Figure 2 and Table 1 show, the four-cluster solution conformed to the theoretical distribution of scores when we cross communion and agency. Q1 (separated) represents individuals higher in agency but lower in communion; Q2 (neglected) individuals are lower on both dimensions; Q3 (muted) individuals are lower in agency but higher in communion; and Q4 (empowered) individuals are higher on both dimensions. The larger n in Q4 likely reflects the positive skew for quality measures of social relations (Fiori et al., 2008). Nevertheless, all quadrants were represented by an adequately high number of individuals.

The next step was to assess whether reported loneliness varied by cluster. To determine this, we compared the loneliness means across the four clusters with a one-way ANOVA using Tukey tests for multiple comparisons. The results indicated that Q2 (neglected) (those low on both agency and communion) had higher loneliness scores (M = 1.78; SD = 0.50) compared to all other quadrants: Q1 (M = 1.34; SD = 0.36), Q3 (M = 1.33; SD = 0.35), and Q4 (empowered) (M = 1.09; SD = 0.20) (all ps < 0.001). Q4 (empowered) (those high on both agency and communion), which produced the lowest loneliness scores, also differed from all the other quadrants (all ps < 0.001). Finally, Q1 (separated) and Q3 (muted) did not differ from each other (p = 0.82) (Figure 3).

We also ran the non-imputed version of the cluster analysis (N = 4,723), and the results did not differ (see Appendix Figure A1).

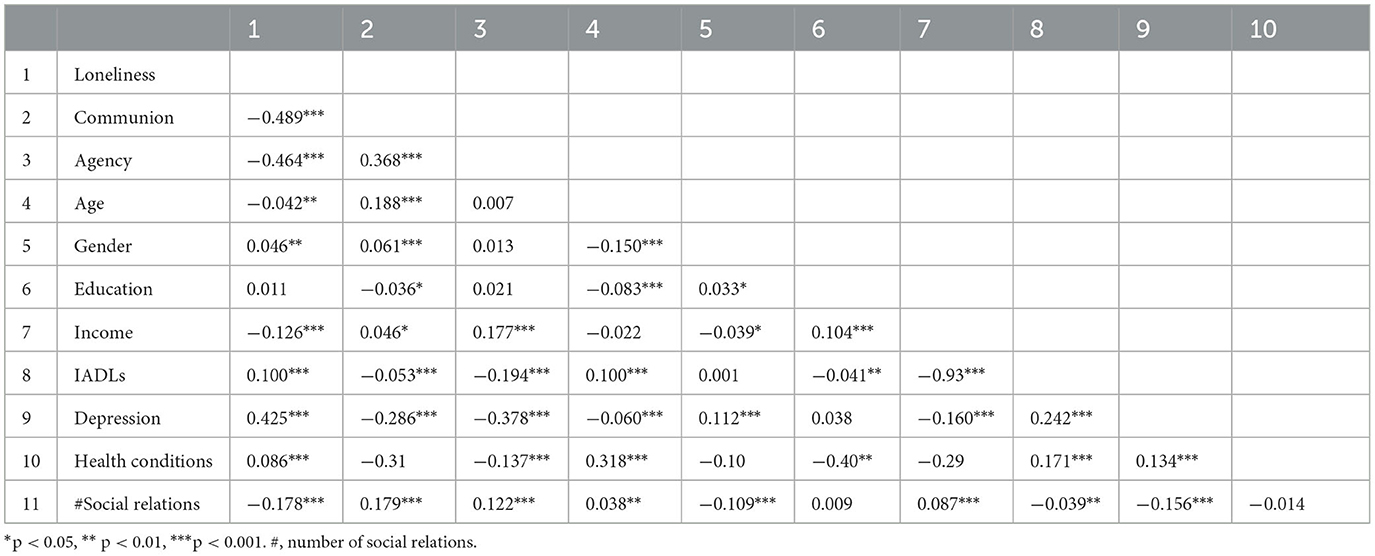

We wanted to further test the above results by considering relevant covariates as described in the Methods section. The correlations among all the variables can be found in Table 2.

Table 2. Summary of bivariate correlations among continuous variables of interest and associated covariates.

For this analysis we only used the non-imputed data set given the large number of covariates that would require imputation, and to show consistency with the imputed results of the cluster analysis. We took the raw predictor scores of communion and agency and centered them, and then created an interaction term. The three effects were then used to predict loneliness scores, beyond considering the effects of the covariates. The regression results are presented in Table 3.

Both communion and agency were significant predictors of loneliness, but so was their interaction. An examination of the simple slopes provides an additional perspective (see Figure 4). These analyses indicate that the effect of communion is weaker among participants at high agency (t = −7.612) than participants at low agency (t = −16.317).

The findings showed that four prototypes of personal social networks emerge when we use as criterion variables indicators of the degree to which people's communion and agency needs are satisfied. Specifically, there was a cluster corresponding to the different quads (Q1 - Q4) proposed by the squad model. Second, loneliness varied by quad, with the lowest loneliness reported by individuals high on both communion and agency, and the highest loneliness reported by those lowest on both dimensions. Individuals high on one dimension and low on the other (Q1 (separated), Q3 (muted) had slightly lower loneliness scores than those in Q2 (neglected) and did not differ from each other. Subsequent regression analysis that considered several covariates confirmed the general pattern of results, in that loneliness was a function of individuals' reported communion and agency.

The present findings add to our understanding of the factors that influence loneliness. To our knowledge, loneliness has always been explained as a deficit in the satisfaction of one's communion or relational needs. Even when adjectives such as quality (Perlman and Peplau, 1981; Cacioppo S. et al., 2015) or salutary are used to describe relationships (Cacioppo and Cacioppo, 2018), the focus is still on the communion dimension. But in addition to communion needs, individuals also have a need for agency, personal control, and choice, and not meeting this need should also affect experienced loneliness. This was evidenced in the main effect for agency in the present analyses (also see Li et al., 2019; Henning et al., 2022). Of greater importance is the configuration of a person's communion and agency. Individuals experiencing the highest loneliness were those with the largest deficits in communion needs, as assumed by models of loneliness, but also their agency needs (Q2, neglected). As well, loneliness came in other varieties. For example, Q3 (muted) individuals who have their communion needs relatively satisfied also exhibited some loneliness, which in this case can be attributed to the lack of agency they reported.

The present findings thus add to our understanding of relationship quality and potentially to the insight researchers have uncovered about the role of social cognition in loneliness, that it is an experience determined in part by a perceived discrepancy between current and desired relations (Peplau and Perlman, 1982). The findings suggest that these perceptions may not only reflect fewer relations than desired, but a discrepancy between current and desired agency.

Without considering PSNs, our focus on communion and agency puts the squad model in the company of conceptualizations that emphasize people's need for supportive relationships, but also autonomy, choice, and achievement. Ryan and Deci's theory of self-determination theory (especially relationships motivation theory) is relevant here, not only because of the tremendous influence it has had, but because of lack of clarity in describing the relationship between relatedness and autonomy needs. These authors have stated that their “primary concern is the main effects” and proposed that the “satisfaction of each of these psychological needs is necessary in an ongoing way for people to function optimally” (Deci and Ryan, 2014, p. 55). In a different paper they noted difficulty in separating the two dimensions (relatedness and autonomy), and then explained this difficulty by suggesting that relationships that help fulfill a person's relatedness needs are also likely to support an individual's autonomy needs (Ryan et al., 2015). This proposed interrelatedness of needs is consistent with how we describe the dynamics of Q4 (empowered), but as the present model indicates, there are other ways in which individuals relate to their PSN, and the satisfaction of one need not imply the satisfaction of the other.

The present research also has implications for models of how relationships affect individual outcomes, such as those dealing with the influence of relationships on thriving (Feeney and Collins, 2015), the achievement of one's ideal self (Drigotas et al., 1999; Rusbult et al., 2009), and mutual goal support (Fitzsimons et al., 2015). These models are rich in their description of dyadic and social cognitive processes. They, however, fall a little short in fully acknowledging a person's agency needs. Feeney and Collins (2015) discuss different aspects of eudaimonic wellbeing that are relevant to the experience of agency, but there is no perspective offered by these frameworks on the crossing of the relational dimension with the personal dimension, and the resultant relationship patterns and dynamics that would suggest. For example, we have discussed how individuals can end up with a particular PSN, such as Q1 (separated), which may result from others' emphasis on the individual's self-sufficiency. This could additionally lead to greater cultivation of one's agency. But the individual's focus on personal goals and agency is not tethered to a warm and supportive base that is associated, for instance, with source of strength and relational catalyst support (Feeney and Collins, 2015). Nevertheless, these frameworks provide many insights into dyadic processes that would be useful to study in conjunction with the broader social relational dynamics described in the squad model.

The present research, although dealing with the most personal aspects of social networks, may also add to our understanding of the broader social networks people inhabit. Most of the work on social networks has focused on structural variables, such as number of relations, interaction frequency, and density (e.g., Granovetter, 1973; Wellman, 1979; Melkas and Jylhä, 1996; Litwin and Landau, 2000; Giannella and Fischer, 2016). Some research has considered quality aspects of social networks such as support and strain, but these aspects have been studied in the context of structural variables (Bosworth and Schaie, 1997; Fiori et al., 2008). This makes it difficult to see the effect of the relational quality variables in the clustering solutions and on the outcome variables. Further, this work has not considered variables relevant to agency, which precludes any insights gained from crossing the two dimensions.

Relatedly, the typical method for generating prototypes in social network research is to use many criterion variables in the clustering analyses, a bit of a kitchen sink approach. This has resulted in arrangements that appear to make sense on the surface, but a closer look suggests some inconsistencies. For example, social network solutions reported in the literature tend to make distinctions between kin and non-kin (Giannella and Fischer, 2016), or family and friends (Fiori et al., 2007, 2008). People get most of their support from the innermost layers of their social circles, but these layers can include both family and friends. In addition, at times friends come to be treated as “chosen kin” (Braithwaite et al., 2010). So, segregating friends from family means relegating the quality dimension to a secondary role when it might in fact provide a parsimonious approach to understanding how social networks affect individual outcomes.

Something not answered by the present research, or by research on social networks, is how people come to inhabit a particular PSN, as well as change from one PSN configuration to another. Apart from family, which a person is born into, it is unclear how people end up with certain social relations. Here we offer some speculative ideas.

It is likely that people's PSNs are the result of a mix of emergent and deliberate processes.2 An emergent network process means that through accident and luck of the draw, a person ends up surrounded by specific network members. Family is a good example of this lottery aspect to PSNs. As well, research on propinquity is consistent with this position. By accident some individuals will have apartments in the same building or next to each other (Festinger et al., 1950), or end up as roommates (Newcomb, 1956), and because of this proximity interact regularly and become friends.

A deliberate network process means that the individual plays an active role in deciding who to associate with. The aging and lifespan literature has shown that people can be selective in who they have relationships with, pruning less rewarding ones, for example (Carstensen, 1991). This social selection is also captured in historical accounts. Among his numerous observations of American life and the U.S. governmental system, De Tocqueville (1835) was taken with the ease with which people freely gathered with others based on their own choosing. This right, of course, is enshrined in the Constitution's first amendment's protection of assembly.

But it is important to note that whether a network development process is emergent or deliberate, this need not connote quality of social relations. Through an emergent process, an individual may have several network members who accept and support their individual needs and strivings, whereas another may end up surrounded by network members who stifle their individual spark. A deliberate process of network development can also result in more or less personal direction and choice. An individual may freely choose a life partner or set of friends that leaves them little room to focus on their personal goals and aspirations.

From our perspective, changing one's PSN so that it significantly affects the degree to which one's communion and agency needs are met [e.g., altering one's Q2 (neglected) configuration to be more like Q4 (empowered)] should result in more positive outcomes. For example, increases in wellbeing such as sense of purpose and life satisfaction should result from greater support of one's communion needs than was previously the case (Chan et al., 2018), as well as greater support of one's agency needs (cf. Welzel and Inglehart, 2010). These proposals need to be tested in future research, as well as the extent to which people's PSN's change over time.

In addition to emergent and deliberate processes, there is room to consider differences in attachment experiences (Shaver and Mikulincer, 2011), relational approaches, and working models of relationships (Bretherton, 1987) as factors that help determine the PSNs individuals inhabit. For example, let us assume that individuals with a Q2 (neglected) PSN are more likely to have an anxious approach to their relationships. One question could be, what came first, their relational approach, or does their relational approach reflect current network relations? Or granting more weight to an individual's history, could early relationships with critical caretakers set them up to replicate dynamics with several of their network members? These are interesting questions, but it is important to be mindful of the many unknowns in how early and ongoing relationship experiences influence adult relational styles (Fraley and Roisman, 2019). For example, individuals differ in how they interact with different persons (Baldwin et al., 1996; La Guardia et al., 2000; Collins et al., 2004). Nevertheless, it will be useful in future research to assess the potential effect of people's approaches to relationships in the context of the different relations in their PSNs.

This study is not without limitations. First, the nature of the data prevents us from drawing any causal conclusions. Our preferred sequencing is that the degree to which an individual's communion and agency needs are satisfied in their PSN determines the level of loneliness. But it could also be that individuals who feel lonely are likely to report lower support for their communion and agency needs. Another possibility is that a factor such as depression could be playing a role, in that lonely people are more likely to be depressed (Cacioppo et al., 2010), which then affects their ability to engage network members and elicit support from them (Gurung et al., 2003). In the present research we controlled for the level of depression participants reported. Nevertheless, the nature of cross-sectional data does not allow us to fully deal with this challenge. What is needed, as previously noted, is research that examines change in network relation quality over time and then assesses changes in loneliness.

A second limitation has to do with our operationalization of communion, in that these scores represent an aggregate of participants' views of four different types of network relations (spouse, children, other family, friends). Some research indicates that supports provided by kin have less efficacy when provided by non-kin (Felton and Berry, 1992). So even though there is empirical utility in the current operationalization of communion, examining the different relationships separately may provide additional insights of how personal social networks operate in supporting a person's communion and agency needs.

A third limitation of the present research is that we did not delve into possible mediators. We have posited that the configuration of an individual's PSN, a function of the degree to which their communion and agency needs are met, predicts experienced loneliness. But there are likely social-cognitive and other factors that impinge on this relationship. One candidate may be relational efficacy, such as the degree to which an individual believes they can alter their relations so that they better serve their needs. But there may be other mediators suggested by specific PSN configurations. Take as an example Q1 (separated) individuals. The lack of communion support may lead them to be less willing to maintain and invest in their relationships. This might not only help cement the communion deficit but create additional psychological burden because giving back and benefiting others is itself tied to various positive psychological and physiological outcomes (e.g., Williamson and Clark, 1989; Brown et al., 2003; Eisenberger and Cole, 2012). It is critical that future research flesh out the psychological and interpersonal mechanisms that drive PSN effects on individual outcomes.

A final limitation of the study is that the survey yielded no information on a person's racial group or ethnic background. As noted in the introduction, differences exist in the valuing of communion and agency related constructs in different cultures (e.g., Gabrielidis et al., 1997). Thus, at present it remains unclear what role, if any, such demographic variables might play in the studied outcomes.

The individual and the group is a constant theme in the social sciences. A focus on social network prototypes based on relational quality can provide us with different perspectives on how the individual relates to their group. This has implications for areas of research such as loneliness but possibly research on other psychological and behavioral outcomes, as well as conceptualizations of social networks and relationship processes.

Group life is a constant in the social sciences because it reflects a theme as old as humanity. But also enduring are the recurring needs pursued by individuals in their groups, to have supportive relationships with others, and to have the opportunity to cultivate skills, strive, and exert control over one's life. Knowledge of different network possibilities may thus not only contribute to our scientific understanding, but also serve the individual pondering their current set of social relations, as awareness of the possibilities may be the first step in altering them so that they better serve their needs.

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: https://www.ucd.ie/issda/data/tilda/wave1/.

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

OY: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. TC: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing—review and editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

We would like to thank Amie Gordon and Ethan Kross for comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

TC was employed by the Google LLC.

The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^The elbow method indicated a four but possibly a five-cluster solution. We thus ran one k-means cluster analysis stipulating four clusters, and a second stipulating five clusters. The k-means model with 5 clusters showed that high communion and high agency (Q4) got broken up further; in addition, there was no reduction in dispersion for low communion and low agency.

The silhouette analysis generates an ASW metric (average silhouette width) that ranges from −1 to 1. −1 is the worst, values near 0 indicate overlap among clusters, and positive values indicate good matching to the assigned cluster. The ASW for the cluster analysis was 0.32. Thus, we considered the width adequate given the theoretical considerations at play with the four quadrants.

2. ^Emergent and deliberate processes are concepts borrowed from the organizational strategy literature (Mintzberg and Waters, 1985).

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., and Wall, S. N. (2015). Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation. Psychology Press.

Andersson, L. (1998). Loneliness research and interventions: a review of the literature. Aging Mental Health, 2, 264–274. doi: 10.1080/13607869856506

Antonucci, T. C. (1986). Measuring social support networks: Hierarchical mapping technique. Gener. J. Am. Soc. Aging 10, 10–12.

Antonucci, T. C. (2001). “Social relations: An examination of social networks, social support, and sense of control,” in Handbook of the Psychology of Aging, eds J. E. Birren and K. W. Schaie (New York, NY: Academic Press), 427–453.

Atkinson, J. W., Bastian, J. R., Earl, R. W., and Litwin, G. H. (1960). The achievement motive, goal setting, and probability preferences. The J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 60, 27–36. doi: 10.1037/h0047990

Bakan, D. (1966). The Duality of Human Existence: Isolation and Communion in Western Man. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally.

Baldwin, M. W., Keelan, J. P. R., Fehr, B., Enns, V., and Koh-Rangarajoo, E. (1996). Social-cognitive conceptualization of attachment working models: availability and accessibility effects. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 71, 94–109. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.71.1.94

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am. Psychol. 37, 122–147. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122

Baumeister, R. F., and Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bullet. 117, 497–529. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Beck, A. T. (1983). “Cognitive therapy of depression: new perspectives,” in Treatment of Depression: Old conTRoversies and New Approaches, eds P. J. Clayton and J. E. Barrett (New York, NY: Raven Press), 265–290.

Berkowitz, L. (1969). Resistance to improper dependency relationships. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 5, 283–294. doi: 10.1016/0022-1031(69)90054-7

Birrell, J., Meares, K., Wilkinson, A., and Freeston, M. (2011). Toward a definition of intolerance of uncertainty: a review of factor analytical studies of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 31, 1198–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.07.009

Bosworth, H. B., and Schaie, K. W. (1997). The relationship of social environment, social networks, and health outcomes in the Seattle Longitudinal Study: two analytical approaches. J. Gerontol. Psychol. Sci. 52B, 197–205. doi: 10.1093/geronb/52B.5.P197

Braithwaite, D. O., Bach, B. W., Baxter, L. A., DiVerniero, R., Hammonds, J. R., Hosek, A. M., et al. (2010). Constructing family: a typology of voluntary kin. J. Soc. Pers. Relationships 27, 388–407. doi: 10.1177/0265407510361615

Bretherton, I. (1987). “New perspectives on attachment relations: security, communication and internal working models,” in Handbook of Infant Development, ed J. Osofsky (New York, NY: Wiley), 1061–1100.

Brim, G. (2018). Ambition: How We Manage Success and Failure Throughout Our lives. London: iUniverse.

Brown, S. L., Nesse, R. M., Vinokur, A. D., and Smith, D. M. (2003). Providing social support may be more beneficial than receiving it: results from a prospective study of mortality. Psychol. Sci. 14, 320–327. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.14461

Cacioppo, J. T., and Cacioppo, S. (2018). “Loneliness in the modern age: An evolutionary theory of loneliness (ETL),” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, ed L. Berkowitz (London: Academic Press), 127–197.

Cacioppo, J. T., Cacioppo, S., Capitanio, J. P., and Cole, S. W. (2015). The neuroendocrinology of social isolation. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 66, 733–767. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015240

Cacioppo, J. T., Hawkley, L. C., and Thisted, R. A. (2010). Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago health, aging, and social relations study. Psychol. Aging 25, 453–463. doi: 10.1037/a0017216

Cacioppo, J. T., Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Hawkley, L. C., and Thisted, R. A. (2006). Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Psychol. Aging 21, 140–151. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.1.140

Cacioppo, S., Grippo, A. J., London, S., Goossens, L., and Cacioppo, J. T. (2015). Loneliness: clinical import and interventions. Persp. Psychol. Sci. 10, 238–249. doi: 10.1177/1745691615570616

Canary, D. J., and Stafford, L. (1992). Relational maintenance strategies and equity in marriage. Commun. Monographs 59, 243–267. doi: 10.1080/03637759209376268

Carstensen, L. L. (1991). Selectivity theory: social activity in life-span context. Ann. Rev. Gerontol. Geriatr. 11, 195–217.

Carstensen, L. L., Isaacowitz, D. M., and Charles, S. T. (1999). Taking time seriously: a theory of socioemotional selectivity. Am. Psychol. 54, 165. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.54.3.165

Carver, C. S., and Scheier, M. F. (1998). On the Self-Regulation of Behavior. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Chan, T., Wang, I., and Ybarra, O. (2018). “Connect and strive to survive and thrive: The evolutionary meaning of communion and agenc,” in Agency and Communion in Social Psychology, eds A. Abele, and B. Wojciszke (London: Routledge).

Cohen, S., and Lemay, E. P. (2007). Why would social networks be linked to affect and health practices? Health Psychol. 26, 410–417. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.4.410

Collins, N. L., Guichard, A. C., Ford, M. B., and Feeney, B. C. (2004). “Working models of attachment: new developments and emerging themes,” in Adult Attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical Implications, ed W. S. Rholes, and J. A. Simpson (London: Guilford), 196–239.

Curl, A. L., Stowe, J. D., Cooney, T. M., and Proulx, C. M. (2014). Giving up the keys: how driving cessation affects engagement in later life. The Gerontol. 54, 423–433. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt037

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2014). Autonomy and need satisfaction in close relationships: Relationships motivation theory. Hum. Motiv. Interpers. Relationships Theor. Res. Appl. 12, 53–73. doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-8542-6_3

Drigotas, S. M., Rusbult, C. E., Wieselquist, J., and Whitton, S. (1999). Close partner as sculptor of the ideal self: behavioral affirmation and the Michelangelo phenomenon. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 77, 293–323. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.77.2.293

Duckworth, A. L., Grant, H., Loew, B., Oettingen, G., and Gollwitzer, P. M. (2011). Self-regulation strategies improve self-discipline in adolescents: benefits of mental contrasting and implementation intentions. Educ. Psychol. 31, 17–26. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2010.506003

Dunbar, R. I. M. (2014). The social brain: psychological underpinnings and implications for the structure of organizations. Curr. Direct. Psychol. Sci. 23, 109–114. doi: 10.1177/0963721413517118

Eisenberger, N. I., and Cole, S. W. (2012). Social neuroscience and health: neurophysiological mechanisms linking social ties with physical health. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 669–674. doi: 10.1038/nn.3086

Feeney, B. C., and Collins, N. L. (2015). A new look at social support: a theoretical perspective on thriving through relationships. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 19, 113–147. doi: 10.1177/1088868314544222

Felton, B. J., and Berry, C. A. (1992). Do the sources of the urban elderly's social support determine its psychological consequences? Psychol. Aging 7, 89–97. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.7.1.89

Festinger, L., Schachter, S., and Back, K. (1950). Social Pressures in Informal Groups; A Study of Human Factors in Housing. London: CRC Press.

Fiori, K. L., Antonucci, T. C., and Akiyama, H. (2008). Profiles of social relations among older adults: a cross-cultural approach. Ageing Soc. 28, 203–231. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X07006472

Fiori, K. L., Smith, J., and Antonucci, T. C. (2007). Social network types among older adults: a multidimensional approach. The J. Gerontol. Series B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 62, 322–330. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.6.P322

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J., and Glick, P. (2007). Universal dimensions of social cognition: warmth and competence. Trends Cognit. Sci. 11, 77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.005

Fitzsimons, G. M., Finkel, E. J., and Vandellen, M. R. (2015). Transactive goal dynamics. Psychol. Rev. 122, 648–673. doi: 10.1037/a0039654

Fraley, R. C., and Roisman, G. I. (2019). The development of adult attachment styles: four lessons. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 25, 26–30. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.02.008

Gabrielidis, C., Stephan, W. G., Ybarra, O., Dos Santos Pearson, V. M., and Villareal, L. (1997). Preferred styles of conflict resolution: Mexico and the United States. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 28, 661–677. doi: 10.1177/0022022197286002

Giannella, E., and Fischer, C. S. (2016). An inductive typology of egocentric networks. Soc. Netw. 47, 15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2016.02.003

Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. Am. J. Sociol. 78, 1360–1380. doi: 10.1086/225469

Guisinger, S., and Blatt, S. J. (1994). Individuality and relatedness: evolution of a fundamental dialectic. Am. Psychol. 49, 104–111. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.49.2.104

Gurung, R. A. R., Taylor, S. E., and Seeman, T. E. (2003). Accounting for changes in social support among married older adults: insights from the MacArthur studies of successful aging. Psychol. Aging 18, 487–96. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.3.487

Han, M., Bi, C., and Ybarra, O. (2016). Common and distinct neural mechanisms of the fundamental dimensions of social cognition. Soc. Neurosci. 11, 395–408. doi: 10.1080/17470919.2015.1108931

Hawkley, L. C., Browne, M. W., and Cacioppo, J. T. (2005). How can I connect with thee? Let me count the ways. Psychol. Sci. 16, 798–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01617.x

Hawkley, L. C., and Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Annal.s Behav. Med. Pub. Soc. Behav. Med. 40, 218–227. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8

Henning, G., Segel-Karpas, D., Bjälkebring, P., and Berg, A. I. (2022). Autonomy and loneliness–longitudinal within-and between-person associations among Swedish older adults. Aging Mental Health 26, 2416–2423. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2021.2000937

Hogan, R. (1983). “A socioanalytic theory of personality,” in Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, ed M. M. Page (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press), 336–355.

Horowitz, L. M., Wilson, K. R., Turan, B., Zolotsev, P., Constantino, M. J., Henderson, L., et al. (2006). How interpersonal motives clarify the meaning of interpersonal behavior: a revised circumplex model. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 10, 67–86. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr1001_4

House, J. S., and Kahn, R. L. (1985). “Measures and concepts of social support,” in Social Support and Health, eds S. Cohen and S.L. Syme (Orlando: Academic Press), 83–108.

Huxhold, O., Fiori, K. L., and Windsor, T. D. (2013). The dynamic interplay of social network characteristics, subjective well- being and health: the costs and benefits of socio-emotional selectivity. Psychol. Aging 28, 3–16. doi: 10.1037/a0030170

Kearney, P. M., Cronin, H., O'Regan, C., Kamiya, Y., Savva, G. M., Whelan, B., et al. (2011). Cohort profile: the Irish longitudinal study on ageing. International J. Epidemiol. 40, 877–884. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr116

Kraus, M. W., Piff, P. K., and Keltner, D. (2009). Social class, sense of control, and social explanation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 97, 992–1004. doi: 10.1037/a0016357

La Guardia, J. G., Ryan, R. M., Couchman, C. E., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Within-person variation in security of attachment: a self-determination theory perspective on attachment, need fulfillment, and well-being. J. Pers. Social Psychol. 79, 367–384. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.79.3.367

Lachman, M. E., and Weaver, S. L. (1998). The sense of control as a moderator of social class differences in health and well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 74, 763–773. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.74.3.763

Lang, F. R., Featherman, D. L., and Nesselroade, J. R. (1997). Social self-efficacy and short-term variability in social relationships: the MacArthur successful aging studies. Psychol. Aging 12, 657–666. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.12.4.657

Leary, M. R., Jongman-Sereno, K. P., and Diebels, K. J. (2014). The pursuit of status: a self-presentational perspective on the quest for social value. The Psychol. Soc. Status 21, 159–178. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0867-7_8

Lee, D. S., Ybarra, O., Gonzalez, R., and Ellsworth, P. (2018). I-through-we: how supportive social relationships facilitate personal growth. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bullet. 44, 37–48. doi: 10.1177/0146167217730371

Li, R., Yao, M., Liu, H., and Chen, Y. (2019). Relationships among autonomy support, psychological control, coping, and loneliness: comparing victims with nonvictims. Pers. Ind. Diff. 138, 266–272. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2018.10.001

Litwin, H., and Landau, R. (2000). Social network type and social support among the old-old. J. Aging Studies 14, 213–28. doi: 10.1016/S0890-4065(00)80012-2

Malinowski, B. (1939). The group and the individual in functional analysis. Am. J. Sociol. 44, 938–964. doi: 10.1086/218181

Markus, H. R., and Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol. Rev. 98, 224–253. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224

McAdams, D. P. (1985). Power, Intimacy, and the Life Story: Persono-Logical Inquiries Into Identity. Homewood, IL: Dorsey.

McAvay, G. J., Seeman, T. E., and Rodin, J. (1996). A longitudinal study of change in domain-specific self-efficacy among older adults. The J. Gerontol. Series Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 51, 243–253. doi: 10.1093/geronb/51B.5.P243

Melkas, T., and Jylhä, M. (1996). “Social network characteristics and social network types among elderly people in Finland,” in The Social Networks of Older People: A Cross-National Analysis, ed H. Litwin (Westport, CT: Praeger), 99–116.

Milyavsky, M., Kruglanski, A. W., Gelfand, M., Chernikova, M., Ellenberg, M., Pierro, A., et al. (2022). People who need people (and some who think they don't): on compensatory personal and social means of goal pursuit. Psychol. Inq. 33, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2022.2037986

Mintzberg, H., and Waters, J. A. (1985). Of strategies, deliberate and emergent. Strat. Manage. J. 6, 257–272. doi: 10.1002/smj.4250060306

Murray, S. L., Holmes, J. G., and Collins, N. L. (2006). Optimizing assurance: the risk regulation system in relationships. Psychol. Bullet. 132, 641–666. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.641

Murthy, V. (2023). Surgeon General: We Have Become a Lonely Nation. It's Time to Fix That. New York, NY: The New York Times.

Newcomb, T. M. (1956). The prediction of interpersonal attraction. Am. Psychol. 11, 575–586. doi: 10.1037/h0046141

Ogolsky, B. G., and Bowers, J. R. (2013). A meta-analytic review of relationship maintenance and its correlates. J. Soc. Pers. Relationships 30, 343–367. doi: 10.1177/0265407512463338

Oswald, D. L., Clark, E. M., and Kelly, C. M. (2004). Friendship maintenance: an analysis of individual and dyad behaviours. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 23, 413–441. doi: 10.1521/jscp.23.3.413.35460

Oyserman, D., Coon, H. M., and Kemmelmeier, M. (2002). Rethinking individualism and collectivism: evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychol. Bullet. 128, 3–72. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.1.3

Peplau, L. A., and Perlman, D. (1982). “Perspectives on loneliness,” in Loneliness: A Sourcebook of Current Theory, Research, and Therapy, eds L. A. Peplau, D. Perlman (New York, NY: Wiley), 1–8.

Perlman, D., and Peplau, L. A. (1981). Toward a social psychology of loneliness. Pers. Relationships 3, 31–56.

Perry-Jenkins, M., and Gerstel, N. (2020). Work and family in the second decade of the 21st Century. J. Marriage Family 82, 420–453. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12636

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Measurement 1, 385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306

Roberts, S. G. B., and Dunbar, R. I. M. (2011). Communication in social networks: effects of kinship, network size, and emotional closeness. Pers. Relationships 18, 439–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01310.x

Rusbult, C., Finkel, E.li J., and Kumashiro, M. (2009). The Michelangelo phenomenon. Curr. Direct. Psychol. Sci. 18, 305–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01657.x

Russell, D., Peplau, L. A., and Cutrona, C. E. (1980). The revised UCLA loneliness scale concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 39, 472–480. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.39.3.472

Russell, D. W. (1996). UCLA loneliness scale (Version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. J. Pers. Assess. 66, 20–40. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55, 68–78. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Ryan, R. M., Deci, E. L., Grolnick, W. S., and La Guardia, J. G. (2015). The significance of autonomy and autonomy support in psychological development and psychopathology. Dev. Psychopathol. Theor. Method 18, 795–849. doi: 10.1002/9780470939383.ch20

Santini, Z. I., Koyanagi, A. I., Tyrovolas, S., Haro, J. M., and Koushede, V. (2019). The association of social support networks and loneliness with negative perceptions of ageing: evidence from the irish longitudinal study on ageing (TILDA). Ageing Soc. 39, 1070–1090. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X17001465

Schuster, T. L., Kessler, R. C., and Aseltine, R. H. (1990). Supportive interactions, negative interactions, and depressed mood. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 18, 423–438. doi: 10.1007/BF00938116

Shaver, P. R., and Mikulincer, M. (2011). “Attachment theory,” in Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology, eds P. A. M. Van Lange, A. W. Kruglanski, and E. T. Higgins (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 160–179.

Stokes, J. P. (1985). The relation of social network and individual difference variables to loneliness. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 48, 981–990. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.48.4.981

Taylor, S. E., and Seeman, T. E. (1999). Psychosocial resources and the SES-health relationship. Annal. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 896, 210–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08117.x

Weiss, R. (1973). Loneliness: The Experience of Emotional and Social Isolation. New York, NY: MIT Press.

Wellman, B. (1979). The community question: the intimate networks of East Yorkers. Am. J. Sociol. 84, 1201–1231. doi: 10.1086/226906

Welzel, C., and Inglehart, R. (2010). Agency, values, and well-being: a human development model. Soc. Indic. Res. 97, 43–63. doi: 10.1007/s11205-009-9557-z

Wenger, G. C. (1997). Social networks and the prediction of elderly people at risk. Aging Mental Health 1, 311–320. doi: 10.1080/13607869757001

Whelan, B. J., and Savva, G. M. (2013). Design and methodology of the irish longitudinal study on ageing. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 61, S265–S268. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12199

Wiggins, J. S. (1991). “Agency and communion as conceptual coordinates for the understanding and measurement of interpersonal behavior,” in Thinking Clearly About Psychology, Personality and Psychopathology, Vol. 1, eds W. M. Grove, and D. Cicchetti (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press), 89–113.

Williamson, G. M., and Clark, M. S. (1989). Providing help and desired relationship type as determinants of changes in moods and self-evaluations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 56, 722–734. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.56.5.722

Ybarra, O. (2002). Naive causal understanding of valenced behaviors and its implications for social information processing. Psychol. Bullet. 128, 421–441. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.3.421

Ybarra, O., Chan, E., Park, H., Burnstein, E., Monin, B., Stanik, C., et al. (2008). Life's recurring challenges and the fundamental dimensions: an integration and its implications for cultural differences and similarities. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 38, 1083–1092. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.559

Ybarra, O., Park, H., Stanik, C., and Lee, D. S. (2012). Self-judgment and reputation monitoring as a function of the fundamental dimensions, temporal perspective, and culture. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 42, 200–209. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.854

Keywords: social network prototypes, loneliness, group, communion, agency, relationships

Citation: Ybarra O and Chan T (2023) The s(quad) model, a pattern approach for understanding the individual and their social network relations: application to loneliness. Front. Soc. Psychol. 1:1278671. doi: 10.3389/frsps.2023.1278671

Received: 16 August 2023; Accepted: 16 November 2023;

Published: 11 December 2023.

Edited by:

Guy Itzchakov, University of Haifa, IsraelReviewed by:

Shruti Tewari, Indian Institute of Management Indore, IndiaCopyright © 2023 Ybarra and Chan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Oscar Ybarra, b3liYXJyYUBpbGxpbm9pcy5lZHU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.