- Department of Psychology, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada

Many episodes of political repression focus on policing ideological authenticity to distinguish true believers from mere pretenders. For insight into this phenomenon, we review a model wherein concerns about ideological inauthenticity and awareness of external incentives to feign ideological allegiances function to activate a suspicious mindset that leads perceivers to selectively attend to and police inauthenticity in their ideological comrades. We review dispositional and situational factors that amplify authenticity concerns as well as cues perceivers attend to when policing authenticity.

Introduction

Policing ideological authenticity was at the heart of many notorious historical episodes of political repression. Consider the French Revolution's Reign of Terror, which was fueled by suspicions that people were feigning allegiance to the revolutionary cause for corrupt intentions (Linton, 2013). To explain some of the revolutionary government's setbacks, many of its leaders imagined a widespread conspiracy of counter-revolutionaries seeking to infiltrate the revolutionary government to sabotage it from within—i.e., “Hidden internal enemies with the word liberty on their lips” (Chaumette, 1793/1987, p. 344). At the height of the Terror, revolutionary leaders scrutinized one another for signs of corruption and inauthenticity. Indeed, merely questioning the legitimacy of the Terror could make oneself a target of suspicion (Doyle, 2018). An early opponent of the Terror presciently warned that this culture of suspicion would culminate in a dismal outcome wherein “the Revolution, like Saturn, will devour successively all its children” (Vergniaud quoted in Edelstein, 2017, p.93).

Beyond these extreme historical cases, policing ideological authenticity also arises in more mundane contemporary contexts. For example, in settings where progressive ideologies are normative, such as some universities and workplaces, individuals who publicly voice support for progressivism are sometimes suspected of doing this as performative activism/allyship to earn reputational rewards rather than from authentic conviction (Kutlaca and Radke, 2023), which may lead to intensive, critical scrutiny of their behavior for signs of inauthenticity.

To provide insights into this phenomenon, we explore how strong motivation to care about ideological inauthenticity and awareness of external pressures to feign ideological allegiances combine to activate a suspicious mindset (Fein, 1996) whereby people become close readers of others' behaviors for evidence of ideological inauthenticity. We explore motivational factors that influence people to care about ideological inauthenticity as well as impacts on social perceptions.

The intuitive inquisitor and the hermeneutics of suspicion

Authenticity policing involves carefully scrutinizing others' behavior to determine whether their stated ideological allegiances are genuine. One definition of authenticity emphasizes the consistency between the person's external expressions and their internal thoughts and feelings (Lehman et al., 2019). It is this sense of authenticity that people tend to focus on when they police ideological authenticity.

There is inherent uncertainty in judging whether another's professed ideology authentically matches their internal attitudes because perceivers lack introspective access to others' minds. To navigate such uncertainty, perceivers rely on tools of everyday social cognition, including perspective-taking and logical rules, for deriving attributions about the causes of people's behavior from knowledge of its situational contingencies. In particular, when contingencies suggest an ulterior motivation for someone to outwardly profess an ideology, perceivers are likely to be suspicious that the person's ideology does not truly reflect their internal attitudes and thus is inauthentic (Fein et al., 1990). For example, when perceivers observe an ideological statement where the author's views align with those of someone with power, they infer that the statement may be motivated by ingratiation and may not reflect the author's true opinion (Fein et al., 1990). Furthermore, when perceivers witness an act where there is salient evidence of a potential ulterior motive, this increases their general attentiveness to cues that individuals' actions misrepresent their internal attitudes (Fein, 1996).

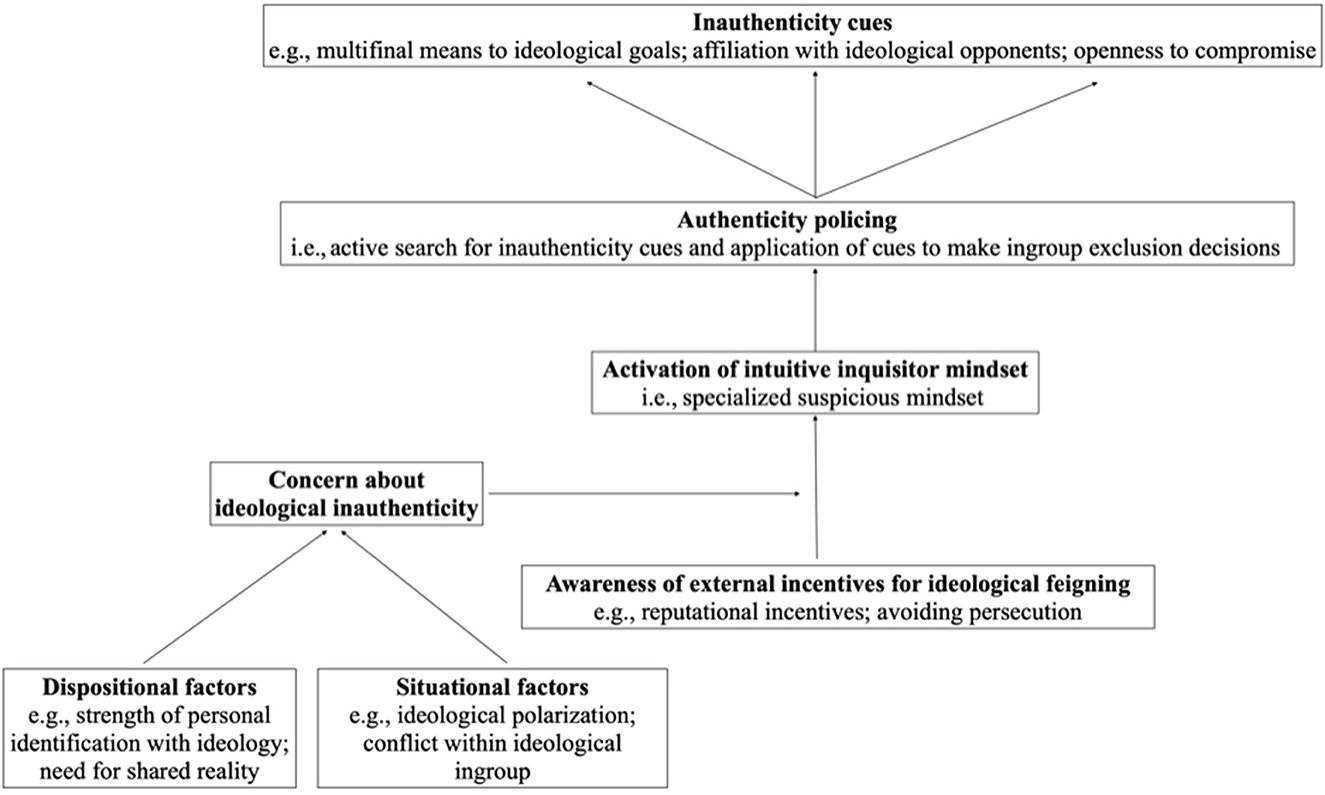

Building on this previous work, we speculate that a suspicious mindset, which we refer to as the intuitive inquisitor (cf. Tetlock, 2002), is activated when a perceiver who is strongly motivated to care about ideological inauthenticity becomes aware of ulterior motives for others to feign allegiance to their ideological ingroup. We propose that the intuitive inquisitor mindset guides authenticity policing, whereby perceivers engage in skeptically skewed reading of others' ideologically relevant behaviors, assigning greater weight to information that confirms suspicions of inauthenticity and supporting intrusive means to investigate these suspicions. Figure 1 summarizes these proposed processes.

Figure 1. Psychological model of authenticity policing. The figure depicts the proposed model whereby concerns about ideological authenticity and awareness of external incentives for ideological feigning combine to activate an intuitive inquisitor mindset that guides policing of cues of ideological inauthenticity.

We hypothesize that merely being aware of external pressures to feign ideological allegiance can activate suspicions about others' ideological allegiances. However, in order to translate such suspicions into active policing, people need something to motivate them to care about ideological authenticity. To provide insights, we next explore dispositional and situational factors that motivate people to care about inauthenticity.

Determinants of authenticity concerns

Dispositional determinants

The strength of the perceiver's own identification with a given ideology is likely to be a particularly critical determinant of how much they care about the authenticity of others' professed commitment to that ideology. Perceivers who only weakly identify with the ideology are less likely to care about their comrades' ideological authenticity than those who are strongly identified. Beyond ideological identification, we review examples of other dispositional factors that may influence concern about ideological inauthenticity: chronic psychological needs, moral foundations, and cultural influences.

Chronic needs for epistemic security

The motivation to develop ideological consensus within a group functions to fulfill fundamental human needs for epistemic security (Jost et al., 2018). When others confirm one's perceptions of reality it can reduce uncertainties about those perceptions. While the need to seek epistemic security through shared ideological reality is fundamental, individuals differ in the chronic intensity of this need (Jost et al., 2018). The benefits of ideological consensus may be threatened by information that raises suspicions about inauthenticity within one's ideological ingroup. People who have stronger chronic needs for epistemic security should thus be more threatened by information suggesting that ideological ingroup members are inauthentic and thus particularly motivated to police their comrades' ideological authenticity.

Moral foundations

People vary in the moral foundations for their ideological convictions (Graham et al., 2009), which may affect how much premium they place on ideological authenticity. These moral foundations are themselves rooted in epistemic needs (Strupp-Levitsky et al., 2020), and so may provide an additional pathway through which epistemic needs translate into authenticity concerns. In particular, moral focus on loyalty should heighten aversion to ideological inauthenticity because people may trust that authentically-identified comrades will remain faithful to their ideology even when it is expedient to sell out, whereas those who are inauthentic may be fair-weather friends who shift ideological allegiances based on changing incentives.

Moral focus on purity is also likely to heighten aversion to ideological inauthenticity. People who value purity will be motivated to protect their ingroup's ideological orthodoxy (Tetlock, 2002). Such ideological puritans may be concerned that people who align with the ingoup's ideology for inauthentic reasons could undermine orthodoxy.

Cultural emphasis on authenticity

A person's cultural worldview may also determine how much they care about ideological authenticity. For example, whereas some cultural traditions moralize only external conduct, other cultures moralize both external conduct and internal subjective states (Cohen and Rozin, 2001). People who are socialized in cultures that moralize internal subjective states should be more chronically concerned with others' ideological authenticity.

Situational determinants

We next review illustrative examples of situational factors that may amplify concerns about ideological inauthenticity.

Ideological polarization

When two ideologies are highly polarized and partisans perceive one another as opposing rivals in a zero-sum struggle for cultural dominance (Jost et al., 2022), people should be strongly motivated to care about and police inauthenticity within their side. Ideological polarization should amplify authenticity concerns because people may believe that those with authentic convictions can be relied on to maintain fidelity to their side even if the balance of power tips toward their adversaries, whereas those whose convictions are inauthentic may be tempted to sellout and join the rival side in response to changing incentives. Furthermore, when ideological polarization is strong, people tend to attribute highly sinister motives to ideological opponents (Sullivan et al., 2010). A person who demonizes ideological adversaries may find it easy to imagine those adversaries resorting to ideological imposture to infiltrate their ideological community and subvert it from within.

Irreconcilable disagreements within ideological communities

When there is intense, sustained disagreement between factions within an ideological movement about their concrete agendas, this may lead each faction to suspect that the opposing faction's allegiance to the movement is motivated by ulterior motives rather than authentic ideological commitment. Because ideologies are abstract, there is often substantial interpretive work in operationalizing them into concrete plans (Ledgerwood et al., 2010). However, due to the influence of naïve realism (Ross and Ward, 1996), people are likely to underestimate the interpretive work involved in this translation, and consequently may assume that anyone who shares a given ideology should have the same understanding of its concrete implications. Thus, when two factions that claim allegiance to a common ideology disagree about its concrete operationalization, each faction may suspect that the other is acting in bad faith for some ulterior purpose. When there have been repeated, failed efforts to convince the other faction to support one's own action plans, the intransigence of the other side in resisting what seems the objectively obvious way to bring one's ideology into concrete realization may promote suspicion that they have some ulterior motivation.

Insecurity during ideological transitions

Concern about ideological inauthenticity may be especially pronounced when ideological norms are in transition within a community. For example, concerns about ideological authenticity tend to be pronounced following the overthrow of a long-entrenched regime by a revolutionary movement (Kuran, 1995). In post-revolutionary times, many individuals who previously supported the old regime publicly switch sides and now profess support for the ideology of the victorious revolutionaries (Kuran, 1995). Many of these late adopters may have been closet revolutionaries all along, but some may only be pretending to support the revolutionary regime's ideology because it is now expedient. Deep down, they may secretly still support the old regime and await an opportunity to restore it. The ambiguities about whether late supporters are true allies or pretenders is likely to heighten people's vigilance for signs of inauthenticity in their midst.

Dominance hierarchies and suspicion of moral hypocrisy

When entrenched dominance hierarchies face sustained challenges to their moral legitimacy, dominant group members may disavow explicit supremacist ideologies that rationalized these hierarchies in the past and claim to now embrace egalitarianism. For example, the 20th century saw a dramatic increase in White Americans' explicit endorsement of racial egalitarianism (Schuman et al., 1997). However, such egalitarian shifts often are not accompanied by active support for policies to dismantle hierarchical structures, and consequently hierarchies persist long after dominant groups explicitly disavow their ideological foundations (Schuman et al., 1997). This pattern is indicative of moral hypocrisy because dominants seem to be motivated to appear egalitarian without bearing the costs of actually being egalitarian (Batson et al., 1999). Awareness of such hypocrisy may make members of subordinate groups wary of trusting the authenticity of dominant individuals' commitment to egalitarianism, which sensitizes them to inauthenticity cues (Kunstman et al., 2016). Because subordinate groups face existential risks when they trust dominant group members who turn out to be false allies, they may need to develop vigilance for signs of inauthenticity. For example, people of color who report higher chronic suspicion of the authenticity of White people's non-prejudiced actions are more accurate in detecting fake smiles in White targets (LaCosse et al., 2015).

Illustrating dispositional and situational factors during the Reign of Terror

The French Revolution's Reign of Terror illustrates some of the hypothetical dispositional and situational motivations to police ideological authenticity. Considering dispositional factors, Maximilien Robespierre, a key advocate for the Terror, appears to have had a high need for epistemic security, as evidenced by his intellectual rigidity, hostility toward opposing views, and absolutist belief in a singular, true “will of the people” as the only legitimate basis of government (Scurr, 2006). When it comes to moral foundations, Robespierre also had a strong preoccupation with moral purity in all matters of public and private life (Scurr, 2006). Further, the Jacobin faction, which drove much of the Terror, appears to have developed a strong cultural valuation of authenticity through the influence of Rousseau's philosophy, which identified a person's authentic self with their inner, “natural” self, not the self conformed to social conventions (Linton, 2013). Many of the identified situational motivators of authenticity concern were also evident during the Terror. In particular, the Revolution itself was a period of ideological transition from the culture of the Ancien Régime to the new Republican ideology, which created pervasive uncertainty about where individuals' allegiances truly stood. Further, there was intense ideological polarization between the government and counter-revolutionary forces they were at war with throughout Europe and civil wars in the Vendée and other regions (Linton, 2013). There also were protracted ideological disagreements between Jacobin and Girondin factions within the Revolutionary government (Linton, 2013). Our analysis indicated that these various factors in combination would have created strong psychological pressures to care about and police ideological authenticity.

Authenticity policing and its consequences for perception and behavior

We have argued that concern about ideological inauthenticity sensitizes people to information about comrades' ideological inauthenticity. We next review examples of cues perceivers may be sensitized to when policing authenticity. Furthermore, when people know that their comrades care about authenticity, they should anticipate that others will also be scrutinizing their behavior for cues of inauthenticity, and these meta-perceptions may motivate them to adjust their behavior to avoid having their authenticity doubted (Willer et al., 2009). Thus, we consider not only how perceivers use inauthenticity cues to judge others but also how targets manage their expression of such cues to avoid being suspected of inauthenticity.

Distancing from ideological adversaries

Authenticity policing may lead people to closely monitor one another's affiliations with adherents of an opposing ideology (Jacoby-Senghor et al., 2015). Applying the logic of guilt by association, perceivers may question the authenticity of someone's ideological convictions if they engage in friendly relations with ideological adversaries, such as simply “liking” a non-ideological social media post from someone of the opposing camp. People may be reluctant to maintain social ties with ideological opponents for fear that such ties will trigger suspicion of their ideological authenticity. The motivation to avoid having one's authenticity suspected may thereby exacerbate the problem of ideologically polarized social networks (Jost et al., 2022).

Overvaluing extreme means

The means someone uses to pursue ideological ends is another relevant cue for assessing authenticity. Multifinal means promote one's ideological cause and other personal goals simultaneously (Kruglanski et al., 2015). By contrast, counterfinal means promote one's ideological cause but are detrimental to other goals (Kruglanski et al., 2015). Due to their differential utility for other goals, these means likely differ in implications for signaling authenticity of ideological convictions. Perceivers who witness a person using a multifinal means are likely to doubt that it was done from authentic desire to promote the ideological goal and instead credit the alternative possibility that it was driven by motivation to achieve other associated goals. Counterfinal means are a more effective authenticity signal because perceivers will assume that only a genuinely committed person would willingly sacrifice important goals to further their ideological cause (Bélanger et al., 2014; Hall et al., 2015).

Undervaluing compromise

Authenticity policing may make people skeptical of the ideological authenticity of comrades who support pragmatic compromises with ideological adversaries (Kelman, 1997). Compromise may be taken as a sign that one is secretly aligned with those opponents. When authenticity policing is strong, people may therefore be reluctant to support pragmatic compromises with adversaries because they anticipate it will lead their comrades to question their authenticity.

Suspicion when ideology is not inherently self-interested

The self-interest norm indicates it is natural to support self-serving ideologies (Miller, 1999). Thus, perceivers may be perplexed when someone supports an ideology that is not obviously self-interested (e.g., White people supporting anti-racism; Chu and Ashburn-Nardo, 2022; Burns and Granz, 2023). To resolve this perplexity, perceivers may seize on information that the person adopted the ideology for inauthentic reasons, such as reputation enhancement. Consistent with this, perceivers are more likely to suspect that sharing one's pronouns in the workplace is motivated by inauthentic, reputation-enhancing reasons when performed by a cisgender person compared to a trans person (Kodipady et al., 2023).

Framework for future research

This review proposes a framework for systematic investigation of authenticity policing that builds on previous work on suspicious social perceptions. Previous work establishes that awareness of ulterior motives for others' actions may lead perceivers to suspect that someone's outward behavior does not authentically reflect their inner attitudes (e.g., Fein, 1996). Other previous work has linked suspicion of others' motivations to vigilance for evidence of inauthenticity (e.g., LaCosse et al., 2015). The proposed model builds on this work by emphasizing that motivation to care about authenticity is required to translate suspicions of others' ulterior motives into authenticity policing. This emphasis on motivational factors that influence people to care about ideological inauthenticity distinguishes this model from evolutionary psychology approaches that emphasize generalized vigilance against inauthenticity as a function of an adaptive cheater-detection mechanism (Cosmides, 1989).

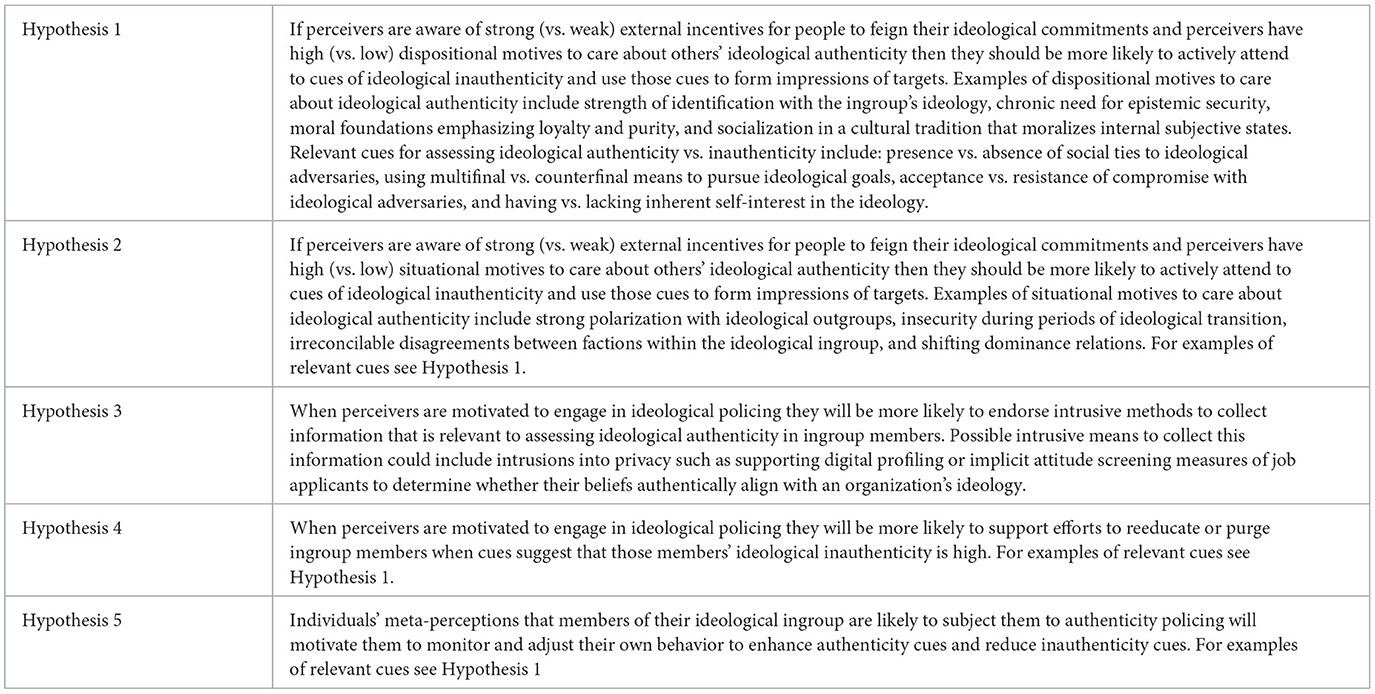

The proposed model also has a novel emphasis on the active work perceivers do in order to police others' authenticity when they are motivated to care about inauthenticity. Table 1 summarizes a set of hypotheses based on this proposed framework. Testing these hypotheses will require researchers to develop methods to gauge the strength of motivation to police authenticity. One such approach could involve providing perceivers an array of information about a target and examining whether they selectively seek information relevant to assessing the target's ideological authenticity and then apply this to make decisions about excluding that target from their ingroup.

Further research on the psychological drivers of authenticity policing is important because the very practices that social groups use to pressure their members to outwardly conform to the group's ideology may ironically lead them to subsequently question whether this outward conformity is authentic or merely motivated to relieve those pressures. Thus, groups that care about members' ideological authenticity often feel a need to extend their social control efforts even after successfully pressuring members to outwardly conform. Also, because information about people's internal attitudes is hard to come by and never definitive (as psychologists who study attitudes know all too well), social groups that care about this type of authenticity are likely to rely on ever more extensive and intrusive forms of ideological policing. Furthermore, history shows that when authenticity policing becomes a widespread practice, it tends to empower the dominant regime at the expense of significantly corroding trust and well-being within communities (Bergemann, 2019). Research on the motivational roots of authenticity policing may provide valuable insights to help communities avoid the self-destructive consequences of succumbing to the Jacobin temptation.

Author contributions

The authors collaborated in developing the ideas, reviewing the background literature, and drafting the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) RE declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Batson, C. D., Thompson, E. R., Seuferling, G., Whitney, H., and Strongman, J. A. (1999). Moral hypocrisy: appearing moral to oneself without being so. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 77, 525–537. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.77.3.525

Bélanger, J. J., Caouette, J., Sharvit, K., and Dugas, M. (2014). The psychology of martyrdom: making the ultimate sacrifice in the name of a cause. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 107, 494–515. doi: 10.1037/a0036855

Bergemann, P. (2019). Judge thy Neighbor: Denunciations in the Spanish Inquisition, Romanov Russia, and Nazi Germany. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Burns, M. D., and Granz, E. L. (2023). “Sincere White people, work in conjunction with us”: Racial minorities' perceptions of White ally sincerity and perceptions of ally efforts. Group Proc. Intergroup Rel. 26, 453–475. doi: 10.1177/13684302211059699

Chaumette, P. G. (1793/1987). “Remarks during Proceedings of the National Convention (5 September, 1793),” in The Old Regime and the French Revolution, ed K. M. Baker (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press), 344.

Chu, C., and Ashburn-Nardo, L. (2022). Black Americans' perspectives on ally confrontations of racial prejudice. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 101, 104337. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2022.104337

Cohen, A. B., and Rozin, P. (2001). Religion and the morality of mentality. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 81, 697–710. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.81.4.697

Cosmides (1989). The logic of social exchange: Has natural selection shaped how humans reason? Studies with the Wason selection task. Cognition 31, 187–276. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(89)90023-1

Edelstein, D. (2017). Red leviathan: authority and violence in revolutionary political culture. History Theory 56, 76–96. doi: 10.1111/hith.12039

Fein, S. (1996). Effects of suspicion on attributional thinking and the correspondence bias. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 70, 1164–1184. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.70.6.1164

Fein, S., Hilton, J. L., and Miller, D. T. (1990). Suspicion of ulterior motivation and the correspondence bias. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 58, 753–764. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.58.5.753

Graham, J., Haidt, J., and Nosek, B. A. (2009). Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 96, 1029–1046. doi: 10.1037/a0015141

Hall, D. L., Cohen, A. B., Meyer, K. K., Varley, A. H., and Brewer, G. A. (2015). Costly signaling increases trust, even across religious affiliations. Psychol. Sci. 26, 1368–1376. doi: 10.1177/0956797615576473

Jacoby-Senghor, D. S., Sinclair, S., and Smith, C. T. (2015). When bias binds: Effect of implicit outgroup bias on ingroup affiliation. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 109, 415–433. doi: 10.1037/a0039513

Jost, J. T., Baldassarri, D. S., and Druckman, J. N. (2022). Cognitive–motivational mechanisms of political polarization in social-communicative contexts. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 1, 560–576. doi: 10.1038/s44159-022-00093-5

Jost, J. T., van der Linden, S., Panagopoulos, C., and Hardin, C. D. (2018). Ideological asymmetries in conformity, desire for shared reality, and the spread of misinformation. Current Opin. Psychol. 23, 77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.01.003

Kelman, H. C. (1997). “Social-psychological dimensions of international conflict” in Peacemaking in International Conflict: Methods and Techniques, eds I.W. Zartman, and J.L. Rasmussen (Washington, DC: U.S. Institute of Peace), 191–237.

Kodipady, A., Kraft-Todd, G., Sparkman, G., Hu, B., and Young, L. (2023). Beyond virtue signaling: Perceived motivations for pronoun sharing. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 53, 582–599. doi: 10.1111/jasp.12937

Kruglanski, A. W., Chernikova, M., Babush, M., Dugas, M., and Schumpe, B. M. (2015). “The architecture of goal systems: Multifinality, equifinality, and counterfinality in means—end relations,” in Advances in Motivation Science Vol. 2 (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 69–98.

Kunstman, J. W., Tuscherer, T., Trawalter, S., and Lloyd, E. P. (2016). What lies beneath? Minority group members' suspicion of Whites' egalitarian motivation predicts responses to Whites' smiles. Person. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 42, 1193–1205. doi: 10.1177/0146167216652860

Kuran, T. (1995). Private Truths, Public Lies: The Social Consequences of Preference Falsification. Harvard University Press.

Kutlaca, M., and Radke, H. R. M. (2023). Towards an understanding of performative allyship: definition, antecedents and consequences. Soc. Person. Psychol. Comp. 17, e12724. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12724

LaCosse, J., Tuscherer, T., Kunstman, J. W., Plant, E. A., Trawalter, S., and Major, B. (2015). Suspicion of White people's motives relates to relative accuracy in detecting external motivation to respond without prejudice. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 61, 1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2015.06.003

Ledgerwood, A., Trope, Y., and Liberman, N. (2010). “Flexibility and consistency in evaluative responding: The function of construal level” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology Vol. 43 (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press), 257–295.

Lehman, D. W., O'Connor, K., Kovács, B., and Newman, G. E. (2019). Authenticity. Acad. Manag. Annals 13, 1–42. doi: 10.5465/annals.2017.0047

Linton, M. (2013). Choosing Terror: Virtue, Friendship, and Authenticity in the French Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Miller, D. T. (1999). The norm of self-interest. Am. Psychol. 54, 1053–1060. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.54.12.1053

Ross, L., and Ward, A. (1996). “Naive realism in everyday life: implications for social conflict and misunderstanding” in Values and knowledge. The Jean Piaget Symposium Series, eds T. Brown, E. S. Reed, and E. Turiel (Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum), 103–135.

Schuman, H., Steeh, C., Bobo, L., and Krysan, M. (1997). Racial Attitudes in America: Trends and Interpretations. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Strupp-Levitsky, M., Noorbaloochi, S., Shipley, A., and Jost, J. T. (2020). Moral “foundations” as the product of motivated social cognition: empathy and other psychological underpinnings of ideological divergence in “individualizing” and “binding” concerns. PLoS ONE 15, e0241144. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241144

Sullivan, D., Landau, M. J., and Rothschild, Z. K. (2010). An existential function of enemyship: Evidence that people attribute influence to personal and political enemies to compensate for threats to control. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 98, 434–449. doi: 10.1037/a0017457

Tetlock, P. E. (2002). Social functionalist frameworks for judgment and choice: Intuitive politicians, theologians, and prosecutors. Psychol. Rev. 109, 451–471. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.109.3.451

Keywords: suspicion, authenticity, attribution, social perception, ideology, political psychology

Citation: Eibach RP and Oakes H (2023) Ideological authenticity and the dynamics of suspicion. Front. Soc. Psychol. 1:1242262. doi: 10.3389/frsps.2023.1242262

Received: 18 June 2023; Accepted: 23 October 2023;

Published: 30 November 2023.

Edited by:

Jazmin Brown-Iannuzzi, University of Virginia, United StatesReviewed by:

Aleksander Ksiazkiewicz, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, United StatesKristjen Lundberg, University of Richmond, United States

Copyright © 2023 Eibach and Oakes. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Richard P. Eibach, cmVpYmFjaEB1d2F0ZXJsb28uY2E=

†Present address: Harrison Oakes, HumanSystems Inc., Guelph, ON, Canada

Richard P. Eibach

Richard P. Eibach Harrison Oakes

Harrison Oakes