- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Behavioural and Social Sciences, University of Groningen, Groningen, Netherlands

Deviants are pivotal to sparking social change but their influence is often hindered by group dynamics that serve to maintain the status quo. This paper examines the influence of a group's value in diversity in deviant's ability to spark social change, with a unique focus on the experience and anticipation of group dynamics that enable minority influence. Hypotheses were tested in three studies (NTotal = 674), which varied in their use of ad-hoc conversation groups or existing friend groups, and whether deviants were newcomers, or existing group members. We demonstrated social influence of a vegan deviant increased to the extent that participants perceived their group to value diversity. Furthermore, group value in diversity related to experienced and anticipated group dynamics that enabled minority influence: decreased conformity pressure, increased attentive listening, and, importantly, an increased search for agreement with the deviant. We discuss the importance of studying group dynamics for understanding what valuing diversity entails.

Introduction

While societies transition to accommodate challenges brought by globalization, mass migration, or climate change, resistance to those who initiate change seems inevitable.

Group members who deviate from group norms to change a group's course tend to be disliked and rejected (Marques and Paez, 1994; Levine and Kerr, 2007). As a consequence, their efforts may backfire and ironically reinforce the majority's commitment to existing norms (Kurz et al., 2020). When deviants do inspire others, this influence seems indirect: Minority influence tends to be delayed, on attitudes on issues related to but different from the focal issue targeted by the minority, and kept private (Moscovici, 1985; Wood et al., 1994).

Decades of research on minority influence has outlined the majority's cognitive responses to minority dissent (e.g., Moscovici, 1976; Nemeth, 1986; Crano and Chen, 1998), and the characteristics that make deviants more or less influential (e.g., consistency, for a meta-analysis, see Wood et al., 1994). However, possibly due to a focus on studying minority influence in settings that allow for little, if any, interaction (e.g., Maass and Clark, 1984; Levine and Prislin, 2013), we know much less about the group values that promote minority influence. This paper zooms into the group dynamics that are experienced and anticipated when a group is confronted with a deviant in their midst. Specifically, we examine whether group members experience and anticipate different group dynamics depending on the extent to which a group values diversity, and whether they explain a deviant's ability to instigate change.

Why deviance may be threatening to groups

Deviance can be defined as a departure from a group's norms or values, resulting in behavior or opinion that is deemed atypical or unusual (Jetten and Hornsey, 2014). Deviants may challenge the group's viewpoints because they perceive them as immoral or wrong, and voice a deviant viewpoint in an aim to motivate their group to adopt better, or more moral, practices (Moscovici, 1976; Hornsey, 2006; Packer, 2008). By challenging a group's current practices, a deviant poses a threat to the cohesion and identity of a group (Marques and Paez, 1994; Jetten and Hornsey, 2014).

Responses to deviance are therefore often aimed at restoring a threatened group identity (Marques and Paez, 1994; Yzerbyt et al., 2000; Hutchison et al., 2011). Classic studies on group conversations show that when a deviant viewpoint is expressed, initial communications are aimed at pressuring the deviant to conform to the majority view. When it becomes apparent that a deviant is not changing their viewpoint, they are more likely to face rejection (Festinger, 1950; Schachter, 1951). Since these classic studies, many have documented the harsh treatment of deviants, ranging from derogation to exclusion from the group (Marques and Paez, 1994; Levine and Kerr, 2007). Groups thus tend to pressure a deviant to conform to group norms, and reject or exclude the deviant if such conformity holds off (For a review, see Levine, 1989). Both responses to deviance can be understood to serve the restoration of a threatened identity. It follows that to increase the acceptance of deviants, one need to mitigate the threat they pose to a group's identity.

The process of minority influence

Despite their apparent threat, researchers and groups have recognized the benefits of deviants for a group's creativity or performance (e.g., De Dreu, 2002), and the innovation of their normative practices (Moscovici, 1976; Ellemers and Jetten, 2013). The influence of deviants is typically argued to occur through a psychological conflict that is evoked by threatening and disrupting the majority viewpoint. Here, the conflict is seen as a key motivator for the majority to critically reflect on their position and can potentially result in a reconsideration of one's position (Moscovici, 1976; Butera et al., 2017). Thus, against the rather pessimistic picture of deviant rejection, there are situations in which deviants do have the ability to stimulate critical reflection on the group's current practices, and push a group toward change. The question is when the latter is more likely to happen?

Previous research mainly focused on characteristics of the deviant (e.g., consistency, flexibility, idiosyncrasy credits) as factors influencing their potential to motivate change (Hollander, 1958; Mugny, 1975; for a meta-analysis, see Wood et al., 1994). At the group level, influence can be predicted by strength, immediacy, and number of people present (Latané and Wolf, 1981). Yet, less is known about how group values may inhibit or promote the deviant's ability to spark change. The present research aims to predict which groups are likely to respond to deviants in a derogatory way, and in which groups minorities are not only accepted but also likely to instigate social change. We propose that there is an important role for the extent to which groups value diversity.

Valuing diversity

It is generally assumed that groups thrive on homogeneity. Group members are more likely to experience a shared identity when differences within their group are small compared to differences between groups (Turner, 1985), and group members fit better in the group the more they are similar to ingroup members (not outgroup members; Turner and Oakes, 1986). Following this logic, a deviant indeed threatens the ability of group members to experience a shared identity, and is more likely to be excluded.

Yet, this general assumption is challenged by examples of groups, cultures, and organizations that seem to value, and thrive on, diversity instead. When groups value diversity or individuality, being different in a group becomes an expression of one's group membership. For example, in individualistic cultures the expression of one's uniqueness is an expression of one's cultural values (Jetten et al., 2002). In groups that value diversity, deviance may thus not be a threat to the group's identity, but an expression of that identity (Rink and Ellemers, 2007; Luijters et al., 2008). Indeed, research shows that deviants are more accepted and valuable in groups that value diversity, compared to groups that value homogeneity (Hutchison et al., 2011; see also Jans et al., 2019), and might be more likely to “voice” their deviance (LePine and Van Dyne, 1998). However, so far it remains unclear whether a deviant in groups that value diversity also exerts more influence?

This is an important question to examine, as research suggests that this relationship may not be as clear-cut. Valuing diversity may enhance the quest for individualism and diversity, motivating group members to stick to their own distinct viewpoint without being influenced by the deviant. As such, when diversity is valued, deviance may not cause the conflict deemed essential in Moscovici's theorizing for stimulating thought – and may thus not stimulate a change of mind.

The conflict part of Moscovici's theorizing, however, is disputed (e.g., Wood et al., 1994). An influential alternative theory by Nemeth (1986) suggests that minority influence occurs through a deliberative process of divergent thinking, which is only possible when there is low arousal – hence, low threat. Accordingly, minority influence tends to occur privately, after some delay, and on attitudes related to the target issue, where it is least threatening to align with a deviant viewpoint. We extend this view by proposing that under low group threat, it should become possible to push the process of divergent thinking to the public sphere: by deliberating on the issue within the group. Specifically, we propose that in groups that value diversity, the threat that deviant views pose to a group's identity is reduced. Consequently, group members may collectively and publicly engage with the deviant views, enabling the development of new norms that incorporate the deviant's perspective.

The present research : group dynamics of social change

Typical research on minority influence tends to focus on cognitive (intra-individual) processes in contexts in which interaction among group members is highly restricted or absent (Maass and Clark, 1984; for reviews, see Levine and Prislin, 2013). However, to get a fine-grained understanding of the processes underlying minority influence, it is essential to zoom into the experienced group dynamics involved in promoting minority influence (Levine and Tindale, 2014; Prislin, 2022). We focus on the psychological experience and anticipation of group dynamics, because we think objective group dynamics are interpreted by individuals in the framework of values that they associate with their group. Indeed, we expect that even imagining an interaction with a deviant within a specific group, say, a group that values member similarity over diversity, could already lead members to anticipate particular group dynamics, such as a pressure on deviants to conform to group norms and influence group members accordingly (cf. Miles and Crisp, 2014). In fact, group members might even be more sensitive to these group dynamics and responses of other group members when they anticipate them, compared to when they engage in them (cf. Duffy et al., 2018).

We examine the impact of group's diversity value on both the acceptance of the deviant, and their ability to induce social change. First, we expect that a group's value in diversity increases the acceptance of a deviant, because the deviant is less threatening to the group's identity (deviant acceptance hypothesis; see also Hutchison et al., 2011).

Second, we examine whether value in diversity promotes the experience of three group dynamics that characterize an open discussion climate (group dynamics hypotheses a-c). First, value in diversity should predict reduced experiences of conformity pressure (A), meaning that deviant perspectives are tolerated. However, influence would require more than that; we examine whether diversity value additionally predicts whether the group is seen to listen to the deviant perspective (B), by engaging with their viewpoints in an open-minded, non-defensive manner (cf. Itzchakov et al., 2020).1 Finally, we expect that seeing value in diversity will, motivate them to search for agreement with the deviant (C). Indeed, if the group is motivated to search for agreement, they may critically reflect on their normative position, and possibly develop a novel shared perspective by integrating the deviant's position. This could be considered an important variable, in which we move away from a conceptualization of value in diversity as the “celebration of differences”, toward a conceptualization in which groups deem diverse perspectives valuable for improving the group's norms and practices.

Finally, if value in diversity indeed fosters the experience of these three group dynamics, we expect that diversity value predicts a shift toward the deviant's perspective (social influence hypothesis). Importantly, change should not only be present in personal (private) intentions. Instead, we hypothesize that influence occurs through a process of public deliberation and should therefore also be reflected in changes in perceived group norms. Together, shifts in personal attitudes, behaviors and group norms underly social change in groups and may be the starting point for change society at large. We test these hypotheses in the context of a vegan deviant. This type of deviance consisted of three qualities that made it particularly suitable to study: First, moving from a meat-based diet to a plant-based diet is an effective and accessible way to significantly reduce carbon emissions, and thereby mitigate climate change; a pressing societal challenge (Poore and Nemecek, 2018). Second, the ability of a vegan deviant to instigate societal-level change has been questioned (see for a review, Bolderdijk and Jans, 2021). Vegans threaten the morality of typical group practices (e.g., meat consumption), and therefore are particularly likely to face derogation (Minson and Monin, 2012; MacInnis and Hodson, 2017), thereby potentially holding back the societal-level change they pursue (Kurz et al., 2020). Third, social influence can be reflected in increased individual vegan attitudes or behaviors, as well as in a perceived increase in group norms on veganism. Indeed, while people may individually decide what to eat, even when in group settings, the group may develop norms and customs regarding the type of food that is generally consumed (Higgs and Ruddock, 2020; Jans et al., 2023).

In Study 1 we assessed whether the treatment and influence of a vegan confederate depended on a group's perceived value in diversity, in a setting with high ecological validity, that is, in real life conversations within student groups. In Study 2, we increased experimental control by testing the hypotheses in a vignette study in which a vegan deviant vs normative newcomer was introduced to participants' existing friend group for which the group's value in diversity (vs. similarity) was made salient. Study 3 was designed to replicate the test with an existing group member who deviates through a recent conversion to a vegan lifestyle. To gain more insight in the process, Study 3 included a measure of identity threat, and a qualitative analysis of participants' descriptions of the dinner they would have with their vegan friend. Materials and data for all three studies are available at dataverse.nl (at https://doi.org/10.34894/WKLYOR). We report all manipulations and exclusions in the paper, all additional exploratory measures are described in Appendix A. Except for Study 2, reported power analyses are post-hoc. In none of the studies was data analyzed before data collection ended.

Hypotheses

Deviance acceptance hypothesis: a group's value in diversity increases the acceptance of a deviant, because the deviant is less threatening to the group's identity.

Group dynamics hypotheses: a group's value in diversity predicts reduced experiences of conformity pressure (a), increased experience that the group listens to the deviant (b), and searches for agreement with the deviant (c).

Social influence hypothesis: a group's value in diversity predicts a shift toward the deviant's perspective in personal (private) intentions and in perceived group norms.

Study 1

Study 1 was designed to test the hypotheses in a setting with high ecological validity: face-to-face discussion groups, with a deviant (vegan) confederate. We additionally assessed the deviant's influence on related sustainable behaviors.

Methods

Participants and design

Participants were students enrolled in the Psychology Bachelor program at (BLINDED) participating for partial course credit. We formed groups of three (n = 17) or four (n = 33) students2, and each group included one of three possible confederates (m/f) who expressed a vegan viewpoint. Because we were interested in how a minority could sway the majority, fourteen participants who indicated also eating mostly vegan in the past year were excluded before analyses3. The remaining sample consisted of 119 participants distributed over 50 groups (96 women, 22 men, 1 other, Mage = 19.18, SD = 1.62), yielding 91% power to detect a medium-sized effect (Cohen's ω = 0.30).

Procedure

Participants individually signed up for participation in a study on attitudes regarding pro-environmental behaviors. Upon arrival at the laboratory, they were assigned to a group of fellow students with whom they engaged in a warming-up assignment. This group task consisted of writing and reading out loud a story together, and served to enhance identification with the group.

Afterwards, participants engaged in a group discussion regarding environmental behavior. Groups were seated in a circle of chairs and instructed to discuss for 10 min about the different ways in which students could contribute to reducing CO2-emissions. In the instructions for the group discussion, groups were asked to discuss different ways to contribute, for instance changes through behavior or lifestyle. They were asked to write down their ideas, and make a top-three of the discussed solutions in which they were asked to take into account feasibility and efficiency. The experiment leader asked whether everyone had understood the instructions, and then turned on the camera and left the room for 10 min. The confederate was instructed to reveal their vegan lifestyle during the discussion, and argue for veganism as a way to reduce CO2-emissions. The confederate started their argument midway the discussion, after the group had discussed one potential solution to reducing CO2-emissions. The confederate was also instructed to be friendly and a team player, while being consistent in arguing in favor of veganism. They were given a list of arguments they could use during the discussion. After the group discussion, participants (including the confederate) were directed to a room where they individually completed the online survey.

Measurements

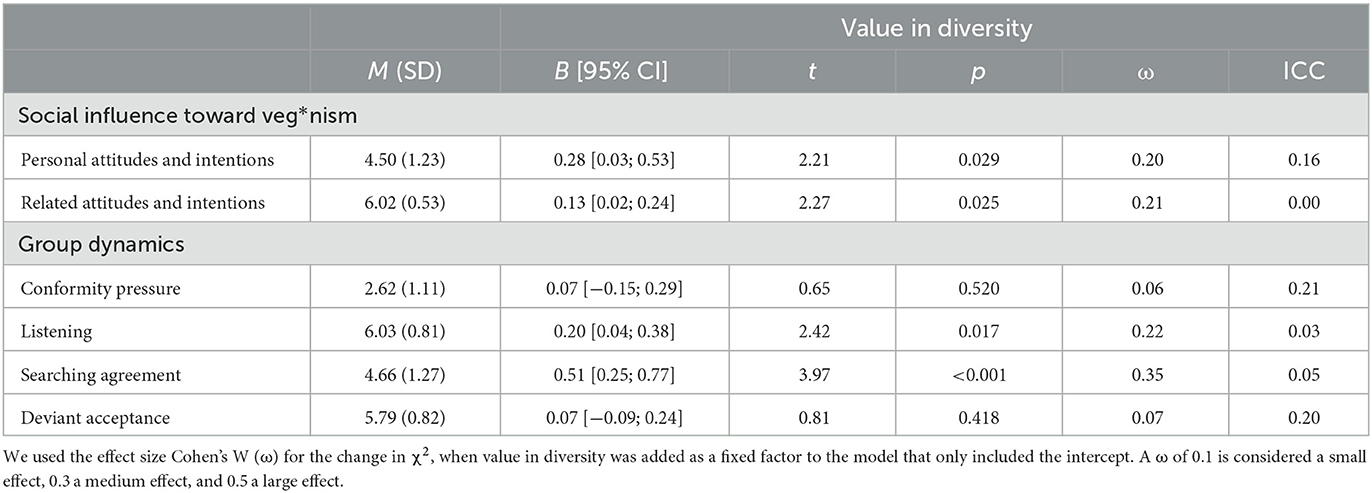

Means and standard deviations of all dependent variables are reported in Table 1, correlations in Appendix B.

Table 1. Study 1. Means (standard deviations) of all dependent variables, the regression results for the predictor value in diversity in the mixed-models analyses, and the intraclass correlations.

Value in diversity

After providing a brief explanation on diversity in groups, participants indicated their agreement with four items about their group's value in diversity: “Because of diversity my group functions better”, “The diversity in my group benefits the group”, “In my group, diversity is experienced as pleasant”, “My group values diversity” (1 = completely disagree, 7 = completely agree, M = 5.25, SD = 0.85, α = 0.84; Homan et al., 2007).

Deviant acceptance

Because the deviance was concealed (i.e., the confederate was presented as an ordinary group member), we asked about acceptance of deviance in general, rather than the specific behavior. We first explained deviance: “Imagine someone in your group behaves differently than the other group members or expresses a different opinion than the prevailing opinion. How do you think your group will respond to this?”. Deviant acceptance was measured by two items: “The group members accept this group member” and “The group members disapprove of this group member” –reverse coded (1 = never, to 7 = often, Spearman-Brown = 0.66).

Experienced group dynamics

In the same block of items as deviance acceptance, participants then indicated how group members responded to such deviant behavior. Specifically, we measured three responses: the extent to which participants felt the group members pressured the deviant to conformity (vs. tolerated the deviant), listened to the deviant, and searched for agreement with the deviant. Conformity pressure was measured with 2 items: “The group members want to change the opinion of this member”, “The group members are fine with this group member having a different opinion” -reverse coded, Spearman-Brown = 0.66). Listening was measured with three items “The group members listen to this group member”, “The group members show interest in this group member”, “The group members ignore this group member” -reverse-coded (α = 0.84). A single item assessed search for agreement: “The group members search for agreement with this group member”. All items were measured on a scale from 1 = never to 7 = often.

Personal attitudes and intentions

We assessed personal veg*n attitudes and intentions with four items: “I would be willing to eat vegan/vegetarian on a regular basis”, “I think eating vegan/vegetarian is important for the environment” (1 = completely disagree, 7 = completely agree, α = 0.76). Across all three studies, we report the combined outcomes on vegan and vegetarian attitudes, intentions (and in Study 2 and 3, also norms). This was done because correlations between measures of vegan and vegetarian outcomes were high (> p = 0.70), and effects on separate vegan and vegetarian measures were similar in direction and strength. There was no consistent pattern of one being more strongly affected than the other.

Additionally, we asked two similar questions for related attitudes and intentions on different pro-environmental behaviors; buying biologically sustainable products, energy usage (turning off heat, short showering, turn of lights), and recycling (glass, plastic bags, paper, e.g., “I think recycling glass is important for the environment”, “I would be willing to recycle all my glass”). We calculated a total scale for all seven related attitudes and intentions by combining all 14 items (α = 0.72).

Control questions

To be able to exclude participants who were already eating vegan, they indicated their agreement with the statement “Past year, I ate mostly vegan” (1 = completely disagree, 7 = completely agree, participants scoring > 4 were excluded). The remaining sample scored very low on past vegan behavior (M = 1.50, SD = 0.78).

Results

Multilevel regressions

To correct for the interdependence of the data, we used mixed-models analyses with all measures at the participant level (Level 1) nested within groups (Level 2). We assessed whether value in diversity predicted (A) acceptance of deviant behavior (in general), (B) group dynamics, measured by conformity pressure, listening behavior, searching for agreement, and (C) social influence, assessed by personal intentions regarding veg*nism, and related pro-environmental intentions. ICC's, multilevel regression results, and effect sizes are reported in Table 1.

A) Acceptance of deviant behavior. Acceptance of deviant behavior was not significantly related to value in diversity.

B) Group dynamics. Value in diversity was unrelated to participant experiences of conformity pressure (a) but positively related to perceived listening (b), and the extent to which participants perceived the group to search for agreement with the deviant member (c).

C) Social Influence. Value in diversity significantly predicted personal attitudes and intentions regarding veg*nism. Moreover, related attitudes and intentions for pro-environmental behavior were also significantly predicted by value in diversity.

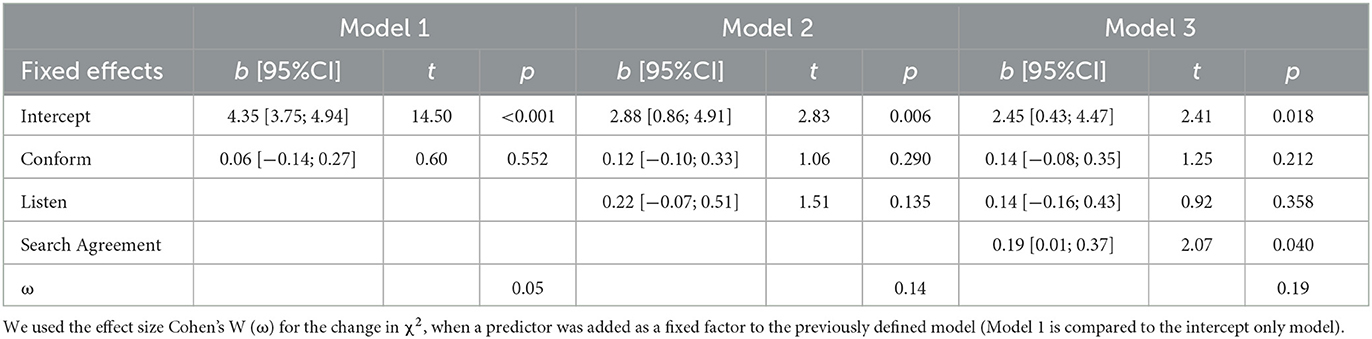

Did group dynamics spark change?

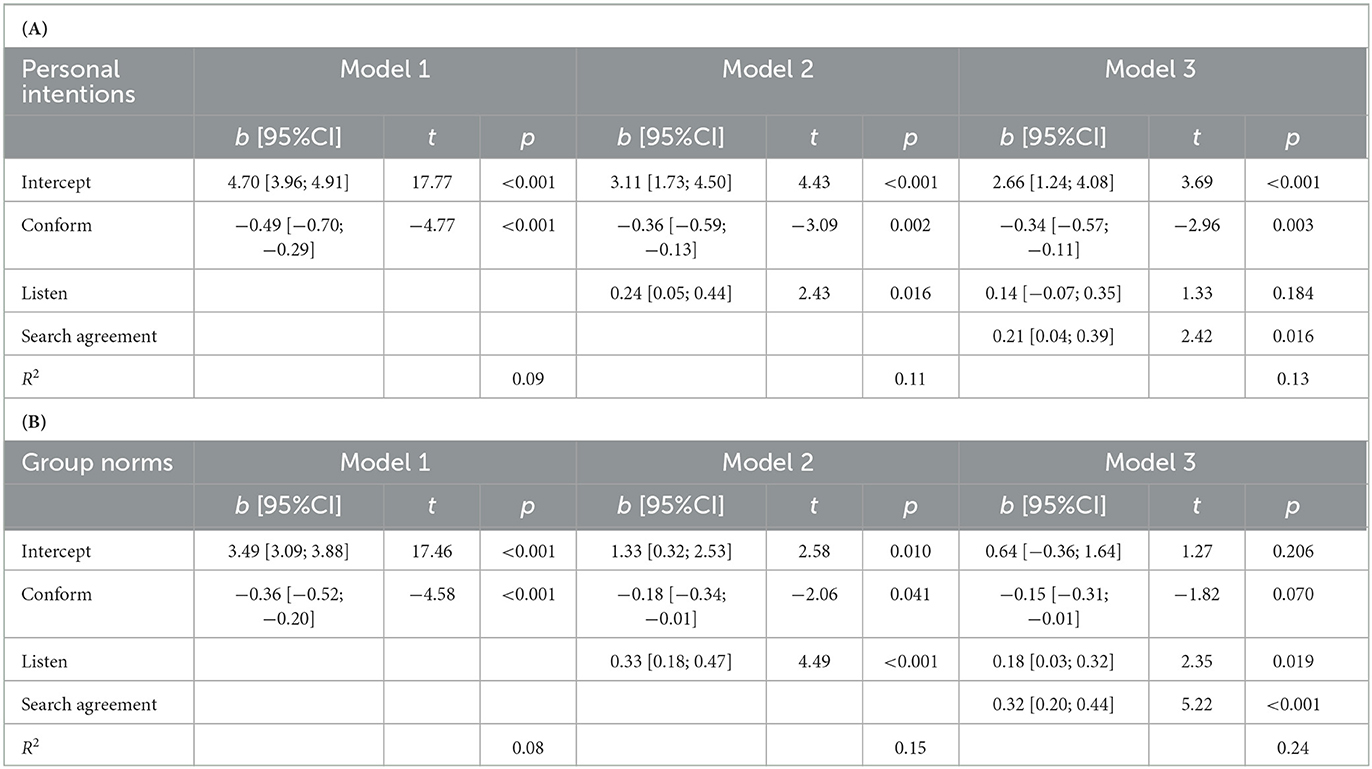

Finally, a mixed-models regression with all group dynamics as simultaneous predictors of personal intentions revealed a significant effect of participants' experience that the group was searching for agreement, while no additional variance was explained by listening or conformity pressure (Table 2, Model 3).

Table 2. Study 1. Step-wise mixed-models regressions of veg*n personal attitudes and intentions on conformity pressure, listening, and searching for agreement.

Discussion

While Study 1 does not allow for causal inferences, it demonstrates that discussion groups change more in the direction of a vegan deviant to the extent that this group values diversity. After a discussion in which a confederate introduces veganism as a solution to reduce CO2-emissions among students, attitudes and intentions to eat vegan are higher the more group members perceive their group values diversity.

We identify two group dynamics that are involved: First, a group's value in diversity is related to group members' experience of whether their group listens to deviant perspectives. While listening increases exposure to the deviant views, for influence to occur, a second dynamic is crucial: a group's value in diversity also related to group members' perception that their group searched for agreement with the deviant. Valuing diversity thus suggests that deviants may not merely be listened to, but that their perspectives are considered important when consensualizing on opinions and practices. Indeed, searching for agreement with the deviant predicted social change beyond the other group dynamics.

Moreover, Study 1 demonstrates that related pro-environmental behavioral attitudes and intentions, like recycling, limiting the use of energy, and buying sustainable products, also shift in discussions with a vegan deviant. This supports a common understanding that a deviant minority elicits systematic, or divergent thinking, and may therefore also affect attitudes related to the target attitude (Moscovici, 1976; Nemeth, 1986; Crano and Chen, 1998). Related attitudes may even be more strongly affected than target attitudes, because of the reduced threat of losing face when aligning oneself with the minority viewpoint (Nemeth, 1986; Wood et al., 1994). Yet, we did not find stronger patterns of influence on related attitudes and intentions. This corroborates our theoretical understanding of the role of valuing diversity in groups. When groups value diversity, a deviant may be seen as an asset rather than a threat for the group, and may spark collective divergent thinking, through open group discussion of the issue at hand.

We found no relation between value in diversity and experienced conformity pressure toward deviants and deviant acceptance. It is possible that group members did not recognize the input on veganism as particularly deviant, or were reluctant to define it as deviant (even though, numerically, veganism is a minority, and therefore, deviant lifestyle in society). As a consequence, our measures, which were about deviant behavior in general may not have picked up on any variance in responding to this vegan group member. This may be partly due to the group task at hand, were the introduction of vegan dietary options, while potentially threatening to the lifestyle of non-vegan group members, also presented a viable option for reducing CO2 emissions. In the next studies, we therefore examine the role of vegan deviance in a situation in which it may be equally relevant, but less aligned with group goals. Specifically, in a situation where the group members have dinner. Moving the pro-environmental focus of our study to the background has the additional advantage that establishing pro-environmental norms cannot unintendedly activate related attitudes on diversity (e.g., Graça, 2021; Ilmarinen, 2021).

Study 2

Study 2 aimed to replicate the findings of Study 1 but we took four steps to increase experimental control: First, the deviant behavior was less concealed, to allow for questions directly targeting this behavior. Second, we compared the acceptance of a deviant to the acceptance of a normative newcomer in the group. Third, to allow for causal inferences, we experimentally manipulated participants perceptions of their group's value in diversity. Fourth, we changed to a setting in which a vegan lifestyle may have larger practical and normative implications, and therefore be more susceptible to conformity pressure, namely, during a dinner with a group of friends. We shifted to a vignette paradigm, in which participants considered their own friend group (with their existing norms and customs), and were asked to imagine a situation where a vegan (vs. normative) newcomer were to enter their group. This way, we could test whether the anticipation of certain group dynamics would be enough to instigate a change in perceived group norms and personal intentions.

Methods

Participants and design

A paid online community sample (n = 290) participated via Prolific in an experiment with a 2 (group value: diversity vs. similarity, between participants) × 2 (deviance: deviant vs. normative newcomer, within participants) design. Fourteen participants did not pass the attention check, and were directed to the end of the survey. A follow-up survey distributed 1 week after the first is described in Appendix C.

Exclusions

We excluded fourteen participants (nsimilarity= 7, ndiversity= 7) for whom the manipulation did not work as intended, and 29 participants who ate mostly vegan in the past year. The final sample consisted of 247 participants (Mage= 28.57, SDage= 11.08, 131 males, 112 females, 4 other), with a majority of Europeans (79%, of which 24% British, 17% Polish, 16% Portuguese, 22% other European); 13% was Northern American, 3% Latin American, 2% African, 1% Asian, 1% unanswered.

To detect a small-to-medium between-condition effect on social influence (f = 0.18), with a power of 0.80 at α = 0.05, assuming a standard correlation among repeated measures of r = 0.50, we set to reach a sample of 246. We targeted a slightly higher number of participants to account for possible exclusion. For the within-between interaction effect on deviant acceptance, the sample yielded a power of 0.95 to detect a small effect (f = 0.10), assuming a standard correlation among repeated measures of r = 0.50.

Procedure and independent variables

After signing informed consent, participants were asked to think about a friend group which they were part of, and to indicate the number of people in this group (median = 5, SD = 3.73). They were instructed to keep this friend group in mind throughout the study.

Group value manipulation

Next, participants were randomly assigned to one of the two group value conditions for which they completed a questionnaire with eight statements on a binary scale (yes/no). In the diversity-value condition the statements concerned the diversity within their friend group (e.g., “My friends and I value each other's different qualities”), in the similarity-value condition the statements concerned similarity within their friend group (e.g., “Our commonalities strengthen my friend group”). Statements were designed such that people would typically agree with them, thereby nudging participants into perceiving that their friend group valued diversity vs. similarity. Indeed, in the diversity-value condition 64.1% of the participants agreed with all statements and 95.5% agreed with more than half of the statements. In the similarity-value condition, 39.9% of the participants agreed with all statements and 95.3% agreed with more than half of the statements. Fourteen participants indicated “no” to 50% or more of the questions, and were excluded, as for them the manipulation did not work as intended.

Deviance manipulation

Next, participants read descriptions of two people who would like to join the participants' friend group: a deviant (Kate) and a non-deviant (Emma). This constituted the repeated measures manipulation of deviance; each participant read both descriptions in a randomized order. The women were described as having similar general characteristics (e.g., spontaneous, empathic, likes to watch series), but for Kate one additional sentence explained that Kate was a vegan (the deviant behavior). To ensure participants considered the information, directly after each description, participants were asked to imagine and describe a situation in which their friend group and (Kate/Emma) were having dinner together.

Directly after this open question, we measured newcomer acceptance in both rounds, and group dynamics in response to the deviant behavior only after the deviant was introduced. Then, the social influence indicators followed. Finally, we measured participants perceptions of their friend groups value in diversity and similarity.

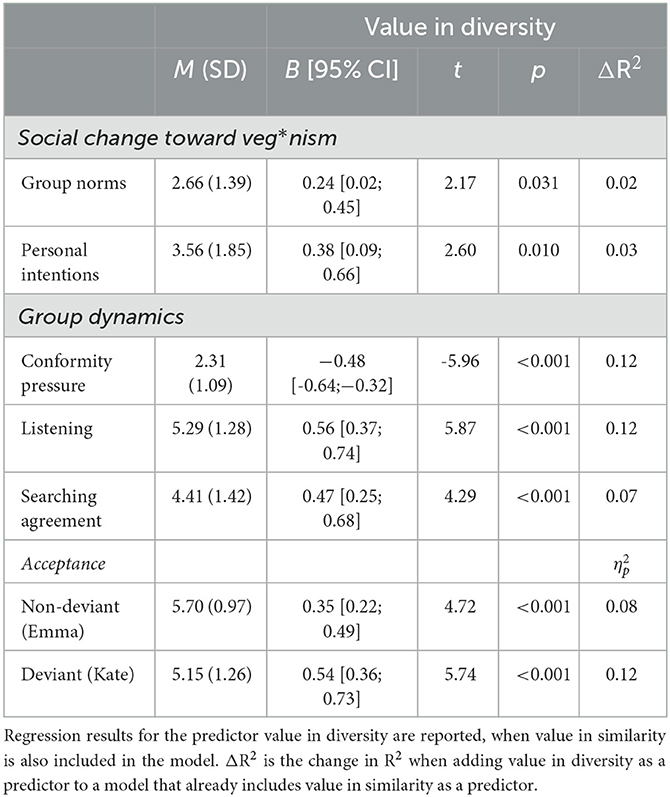

Measures

Table 3 reports all means and standard deviations.

Table 3. Study 2. Means (standard deviations) for all dependent variables, and regression results with value in diversity as a predictor.

Value in diversity and value in similarity

Two single items assessed whether participants felt their friend group valued diversity: “My friend group and I value each other's differences” (M = 6.05, SD = 0.91) and similarity: “My friend group and I value having things in common” (M = 6.08, SD = 0.95), on a scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree, to 7 = strongly agree.

Newcomer acceptance

We measured acceptance for each newcomer with seven statements, e.g., “It is likely that (Kate/Emma) would be accepted in my friend group,” (α Kate= 0.94, α Emma= 0.92).

Group dynamics

We slightly adjusted the group dynamics items of Study 1 to specifically examine how participants expected their groups to respond to the vegan behavior of Kate (i.e., the deviant). Other than that, the scales for anticipated listening (3 items, α = 0.87), and search for agreement remained unchanged. We added three items to the scale for conformity pressure (vs. tolerance): “My friend group would expect Kate to conform to us and our eating habits”, “I feel like Kate would have to conform to us and our eating habits”, and “Kate can be herself in my friend group when it comes to being vegan”(r), (α = 0.77).

Social influence

Because the vegan and vegetarian outcome measures were highly correlated (norms: Pearson r = 0.81, intentions: Pearson r = 0.77) and yielded similar results, we only report the results of the combined scales of veg*nism. We assessed a change toward veg*nism at the level of group norms and the level of personal intentions.

Group norms

Perceptions of group norms were assessed with four items, targeting both vegan and vegetarian diets: “My friend group would be willing to eat vegan/vegetarian on a regular basis”, “My friend group feels it is important to eat vegan/vegetarian,” (α = 0.89).

Personal intentions

Two items assessed personal intentions: “I would be willing to eat vegan/vegetarian on a regular basis” (Spearman-Brown r = 0.87, p < 0.001).

Control questions

We asked participants to indicate on a binary scale (yes/no) whether anyone in their friend group was a vegan. All reported effects remain significant when analyzing the data without participants (n = 33) who had a vegan in their friend group. Furthermore, past behavior was assessed as in Study 1, leading to the exclusion of 29 participants who scored above the midpoint. The remaining sample scored very low on past vegan behavior (M = 1.46, SD = 0.69).

Results

Condition effects

Analyses of variance revealed that the manipulation had the intended effect on value in diversity, F(1, 245) = 9.26, p = 0.003, = 0.036, but not on value in similarity, F(1, 245) = 0.82, p = 0.367, = 0.003. Furthermore, group value condition did not directly affect the dependent variables: deviant acceptance, F(1, 245) = 2.49, p = 0.116, conformity pressure, F(1, 245) = 0.68, p = 0.410, listening, F(1, 245) = 1.26, p = 0.262, group norms, F(1, 245) = 1.29, p = 0.415, and personal intentions, F(1, 245) = 0.40, p = 0.527. Possibly, this was because our manipulation only had a small effect on value in diversity. To examine our hypotheses further, we conducted regression analyses using our measure of value in diversity (i.e., the manipulation check) as a predictor of the dependent variables.

Regression analyses

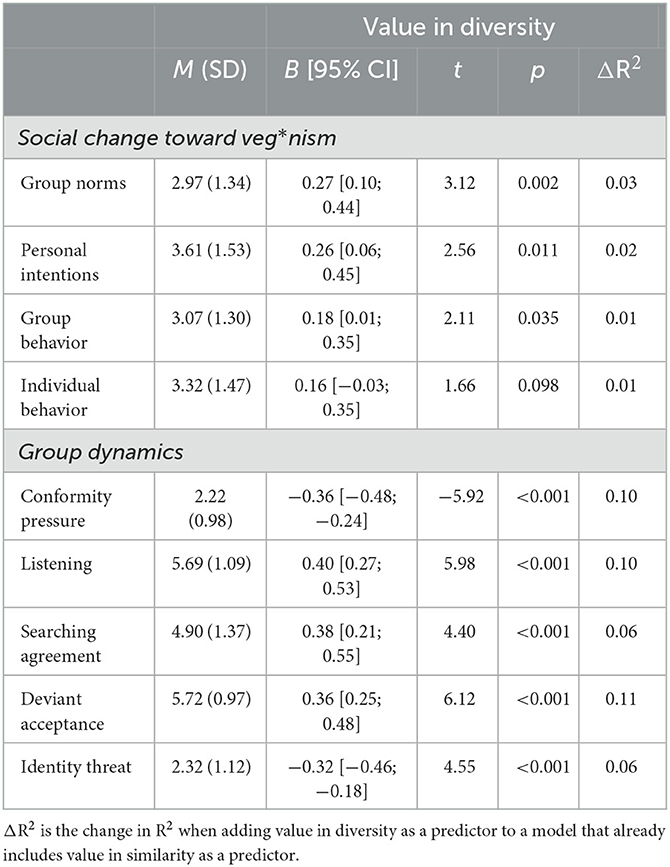

We conducted several regressions, to examine whether value in diversity would predict (A) deviant acceptance, (B) anticipated group dynamics, and (C) social influence. All regression results are displayed in Table 3.

Value in diversity and value in similarity were positively correlated, with r = 0.464, p < 0.001. This is not uncommon, and it has been argued to consider the two as separate constructs (Ofori-Dankwa and Julian, 2002). In our case, the positive relation may be attributed to both items encompassing a component of general value (or valence) one attaches to the group in addition to the more specific value in diversity or similarity. To control for this general value, we included value in similarity as a covariate in all regression models, while estimating the unique predictive power of value in diversity. Value in similarity had no effect on any of the outcome variables, ps > 0.246, all results are reported in Appendix D.

A) Deviant acceptance. We conducted a repeated-measures analysis with a repeated measures factor of deviance (0 = normative newcomer, 1 = deviant newcomer), the deviance by value in diversity interaction, and the deviance by value in similarity interaction to predict acceptance of the newcomer. We found a main effect of deviance on acceptance, suggesting that the normative newcomer was more accepted than the deviant, F(1, 244) = 4.15, p = 0.043, = 0.017. A large main effect revealed that value in diversity positively predicted acceptance (averaged across the deviant and non-deviant), F(1, 244) = 36.29, p < 0.001, = 0.129. The effect of deviance on acceptance was moderated by value in diversity, F(1, 244) = 5.53, p = 0.019, = 0.022, suggesting that for deviants, acceptance was more strongly predicted by the group's value in diversity. Indeed, although value in diversity relates positively to the acceptance of both newcomers, the regression coefficient for the deviants falls outside the confidence interval around the coefficient for normative newcomers.

B) Group dynamics. Regression results show that value in diversity predicted reduced anticipation of conformity pressure toward the deviant, but increased listening, and an increased search for agreement with the deviant on the topic of veganism.

C) Social influence. Value in diversity positively predicted both perceived veg*n group norms and veg*n personal intentions.

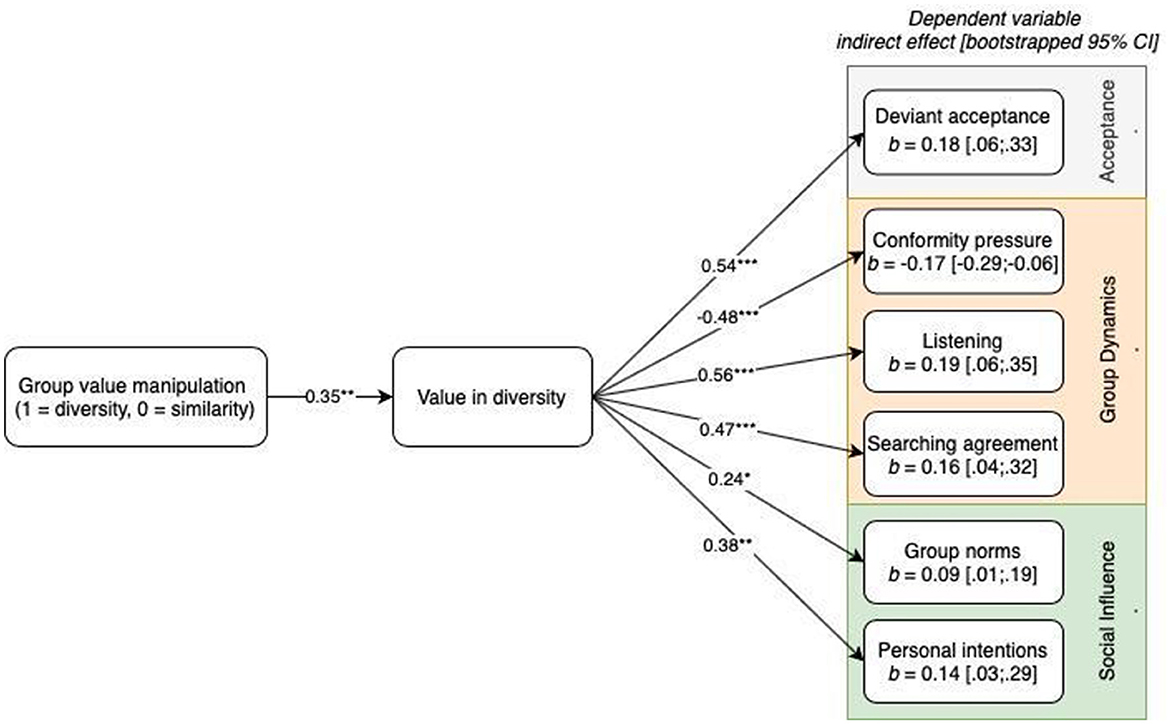

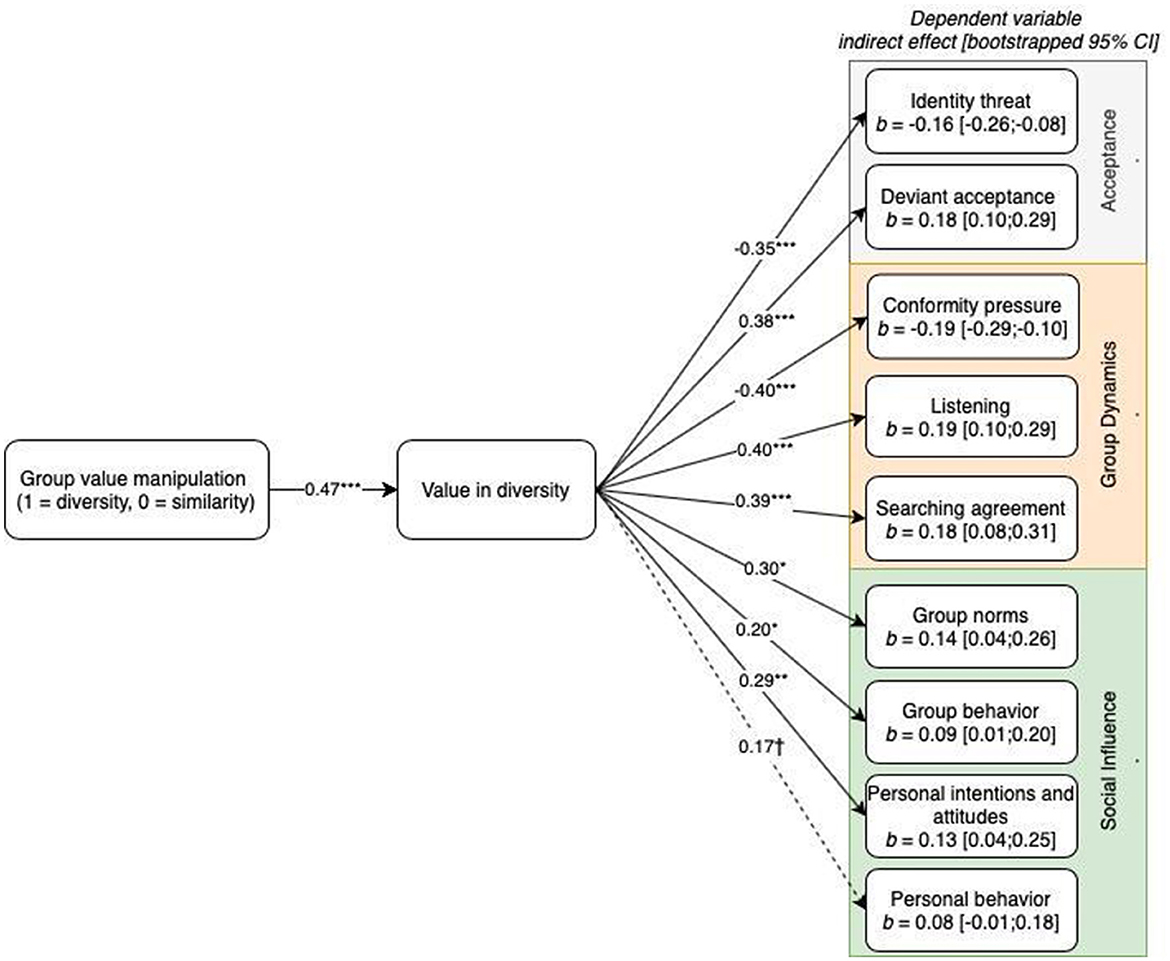

Indirect effects

Figure 1 displays the indirect effects of the group value manipulation, through influencing perceived group value in diversity, on deviant acceptance, conformity pressure, listening, searching for agreement, veg*n group norms and personal intentions. All effects are calculated when value in similarity was included as a second mediator, using the PROCESS macro by Hayes (2017, model 4). Condition was associated with all outcome variables by increasing value in diversity (but not value in similarity, see Appendix D).

Figure 1. Indirect effects, and bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals of the group value manipulation, via value in diversity, on acceptance, group dynamics, and social influence in Study 2. All coefficients are obtained when value in similarity was included in the model as a second mediator.

Did group dynamics spark change?

Finally, regressing the social influence indicators simultaneously on all three anticipated group dynamics demonstrated that anticipated conformity pressure significantly predicted reduced veg*n intentions, and marginally significantly predicted reduced veg*n group norms. Simultaneously, anticipated listening predicted increased vegan group norms, but not veg*n intentions. Finally, anticipated searching for agreement positively predicted both veg*n group norms and intentions (see Tables 4A, B, Model 3). Together, the anticipated group dynamics explained 24% of the variance in group norms, and 13% of the variance in personal intentions.

Table 4. Study 2. Stepwise Regressions of veg*n personal intentions (A) and group norms (B) on the group dynamics conformity pressure, listening and searching for agreement.

Discussion

Study 2 replicates Study 1's finding that a group's value in diversity positively predicts a vegan deviant's influence on group members vegan behavioral intentions. Furthermore, the findings extend Study 1 in multiple ways:

First, they challenge the critical notion that minority influence is an individual, private process (e.g., Moscovici, 1976; Nemeth, 1986), by showing that, to the extent that groups value diversity, group norms are also affected by the deviant. Study 2 further outlines the dynamics that catalyze minority influence: a group's value in diversity reduces the anticipation of conformity pressure toward the deviant, while increasing the anticipation of listening and searching for agreement with the deviant. Combined, these three dynamics enable an open discussion climate, in which groups are expected to integrate the deviant perspective with existing group views to innovate group norms and practices.

Second, while Study 2 manipulated the group's diversity value to allow for inferences of causality, no direct effects of the manipulation on the outcome variables were found. Correlational evidence demonstrated that the manipulation was indirectly associated with all outcome variables, via a group's perceived value in diversity. Although indirect effects in the absence of a direct effect should be interpreted with caution, they do point to the significance of a group's value in diversity in explaining social influence and the group dynamics involved (e.g., Rucker et al., 2011).

Third, Study 2 shows that newcomers can motivate groups to become more veg*n. This is interesting, in light of previous findings of 50 years of research suggesting that newcomer influence is relatively uncommon (Rink et al., 2013), because they first need to be socially accepted before groups will be open to their perspectives (Kane and Rink, 2015, see Levine and Choi (2010) for a review of factors that may increase newcomer influence). We demonstrated that although groups are generally less accepting of deviant newcomers than of normative newcomers, this becomes less so when groups value diversity. In these groups, it seems that members recognize the value that deviant newcomers may have for improving their group.

Study 3

Study 3 aimed to replicate the previous findings on existing members of friend groups that converted to a vegan diet. Existing group members can face stronger derogation than newcomers, as they particularly threaten the group's identity (Pinto et al., 2010). Furthermore, Study 3 examined the process variable of identity threat: We hypothesized that diversity value reduces the threat a deviant poses to the group identity (and therefore decreases the triggering of defense mechanisms, such as reduced acceptance and conformity pressure). Study 3s planned sample size, inclusion/exclusion criteria and planned primary analyses were preregistered (https://osf.io/tm5nv/?view_only=0a8f8e02a48b412fbd64dc830e7d50f7) to test a further moderation hypothesis.

Finally, Study 3 was designed to gain deeper understanding of the anticipated group dynamics involved in deviant acceptance and influence, by analyzing the qualitative content of the described group process.

Methods

Participants and design

A paid online community sample (n = 355) recruited through Prolific completed an online survey with two group value conditions (diversity-value or similarity-value). We excluded seven participants who did not pass the attention check (i.e., “if you read this statement, choose the agree option”), nine participants who answered “no” to 50% or more questions in the manipulation; (nsim= 6, ndiv= 3), and 31 participants who indicated eating mostly vegan in the past year. The remaining sample scored very low on past vegan behavior (M = 1.47, SD = 0.73).

The remaining 308 participants (Mage = 25.07, SDage = 7.80, 198 males, 109 females, and 1 other) comprised an international sample with the majority being European (86%, of which 24% British, 17% Polish, 16% Portuguese, 22% other European), and 5% Northern American, 4% Latin American, 2% African, 3% Asian. Sensitivity analyses revealed that this sample yielded 80% power to detect effects of b = 0.14 at α = 0.05.

Procedure

After providing informed consent, participants were asked to imagine their friend group, and indicate the number of people in this group (median = 5, SD = 2.74). They were randomly assigned to either the diversity- or similarity-value condition, which was manipulated similarly as in Study 1. To strengthen the manipulation, participants received the following text after the manipulation: “Your responses underline the value of diversity (similarity))for friend groups. Indeed, research on friend groups, and what predicts strong friendships over time, shows that diversity (similarity) is an essential feature of long-lasting friendships.” They were then asked to describe an advantage of having a diverse (similar) friend group.

Deviance

Next, participants were asked to imagine that a person in their current friend group recently became a vegan. Participants entered the first name and gender of who such a person might be, which we used to tailor questions about the deviant throughout the survey. After this, the procedure was similar to Study 1; participants described a situation in which their friend group including (NAME) were having dinner together, and subsequently answered questions about deviance acceptance, group dynamics, veg*n behavior of themselves and their group, identity threat, veg*n personal attiutdes and intentions, veg*n group norms, and their group's value in diversity and similarity, in this specific order.

Measures

All means and standard deviations are reported in Table 5, correlations in Appendix C. Participants rated their agreement with each item on a 7-point Likert-scale with labels, 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree, unless indicated otherwise.

Table 5. Study 3. Means (standard deviations) of all dependent variables and regression results with value in diversity as a predictor.

Diversity value and similarity value

We assessed whether participants felt their friend group valued diversity and similarity, with two items each: “My friend group and I value each other's differences”, “I think diversity is important in my friend group” (r = 0.78) and similarity: “My friend group and I value having things in common”, “I think similarity is important in my friend group” (r = 0.62).

Deviant acceptance

Because some statements appeared odd when referring to an existing friend (e.g., “(NAME) would fit into my friend group”), we adjusted the deviant acceptance measure of Study 1 to specifically target the acceptance of the vegan diet rather than the person (e.g., “(NAME)'s vegan diet would fit into my friend group”). We combined the six items in a scale (α = 0.80), and removed a 7th item, “my group would be happy to have Kate as our friend”.

Identity threat

We adjusted five items of the identity threat scale of Dhont and Hodson (2014) to specifically measure vegan identity threat. For instance: “(friend's name)'s vegan diet poses a threat to our group's customs” (α = 0.77).

Group dynamics

We used the scales of Study 2 to measure the extent to which participants expected their friend group to pressure (friend) to conform to their eating habits (α = 0.73), listen to (friend) when talking about their vegan diet (α = 0.81), and search for agreement with (friend) on the topic of veganism.

Social influence

In addition to the general individual and group level social influence measures used in Study 2, we also assessed the specific group and individual veg*n behaviors during the dinner.

Group norms

Veg*n group norms were assessed as in Study 2 (α = 0.90).

Group behavior

Participants indicated their agreement with three items concerning their friends' behavior during the dinner: “During the dinner, my friends would likely eat vegan”, “…, my friend would likely eat vegetarian”, “…, my friends would likely eat meat or fish (reverse-coded)” (α = 0.80).

Personal attitudes and intentions

Personal intentions were assessed as in Study 1, but combined with two additional items inferring personal attitudes “I feel it is important to eat vegan/vegetarian” (α = 0.87).

Personal behavior

Three items measured participants behavior during dinner: e.g., “During the dinner, I would feel inclined to eat vegan” (α = 0.79).

Control questions

Control questions were the same as in Study 2. 46 participants indicated someone in their friend group was a vegan; all of the reported significant results remain significant when excluding these participants.

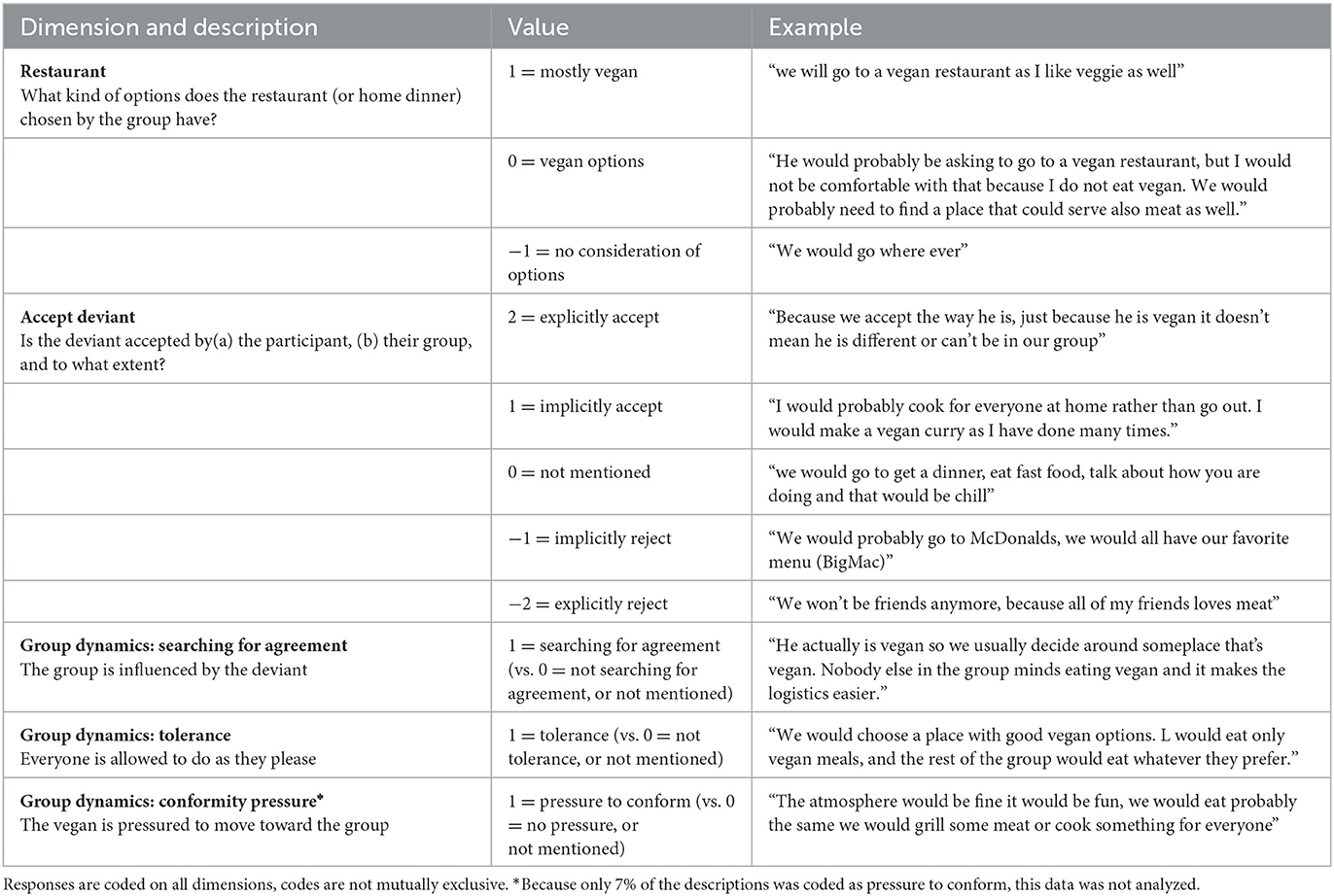

Content coding

A research assistant blind to conditions was trained to code the dinner descriptions written by each participant. See Table 6 for the coding scheme and examples. We coded the extent to which the deviant was accepted by (a) the participant and (b) their group. Furthermore, we coded the group dynamics split into three categories; whether the group searched for agreement with the deviant (to capture minority influence), pressured the deviant to conform to the majority viewpoint (to capture majority influence), and was tolerant to the deviant perspective, in the sense that everyone could do their own thing in this group. Please note that while we combined the items for conformity pressure and the reversely coded tolerance items in our quantitative measure, in the content coding we tried to tease them apart, to explore whether individuals would mention each of these processes themselves. However, conformity pressure could be coded in only 7% of the cases, which could threaten reliability. We therefore decided not to analyse this code. Finally, we coded whether the group chose a restaurant or home dinner with mostly vegan (vegetarian) options, multiple options, or did not consider vegan options.

Table 6. Coding scheme and examples of the participant's descriptions of the dinner with their vegan friend.

Results

Condition effects

Analyses of variance revealed that the manipulation had the intended effect on value in diversity, F(1, 306) = 21.34, p < 0.001, = 0.065, Mdiv = 6.31, SD = 0.67, Msim = 5.85, SD = 1.05, and on value in similarity, F(1, 306) = 7.18, p = 0.008, = 0.023, Mdiv = 5.49, SD = 1.01, Msim = 5.78, SD = 0.88. However, no other direct effects of condition on the dependent variables emerged: deviant acceptance, F(1, 306) = 0.39, p = 0.533, identity threat, F(1, 306) = 0.00, p = 0.978, conformity pressure, F(1, 306) = 0.09, p = 0.766, listening, F(1, 306) = 1.94, p = 0.200, searching for agreement, F(1, 306) = 0.72, p = 0.397 group norms, F(1, 306) = 0.00, p = 0.994, group behavior, F(1, 306) = 0.01, p = 0.915, personal norms, F(1, 306) = 0.01, p = 0.938, individual behavior, F(1, 306) = 0.15, p = 0.700.

Regression analyses

As in Study 1, we conducted several regressions to assess the predictive value of value in diversity for (A) deviant acceptance and identity threat, (B) group dynamics, again measured by conformity pressure, listening behavior, and searching for agreement (C) social influence at the group and individual level, in terms of norms, attitudes and intentions, and this time also as veg*n behavior. Regression results are reported in Table 5.

As in Study 1, value in diversity and value in similarity were positively correlated, with r = 0.304, p < 0.001, and value in similarity was added as a covariate to the regression models. Value in similarity was not predictive of any of the dependent variables (see Appendix F).

A) Identity threat. Value in diversity predicted reduced identity threat and increased acceptance of a deviant friend.

B) Group dynamics. Value in diversity predicted reduced anticipation of conformity pressure toward the deviant, but increased anticipation of listening and searching for agreement with the deviant on the topic of veganism.

C) Social influence. Value in diversity predicted group norms and group behavior during dinner. Moreover, value in diversity predicted personal attitudes and intentions, but the effect on personal behavior did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.098).

Indirect effects

Figure 2 displays the indirect effects of the group value manipulation, through a shift in perceived group value in diversity, on deviant acceptance, anticipated conformity pressure, listening, searching agreement, group norms, and personal intentions. Effects are calculated when value in similarity was included as a second mediator. Condition was associated with all outcome variables by shifting value in diversity (but not in value in similarity, see Appendix F), except for personal behavior.

Figure 2. Indirect effects, and bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals of the group value manipulation, via value in diversity, on acceptance, group dynamics, and social influence in Study 3. All coefficients are obtained when value in similarity was included in the model as a second mediator.

Did group dynamics spark change?

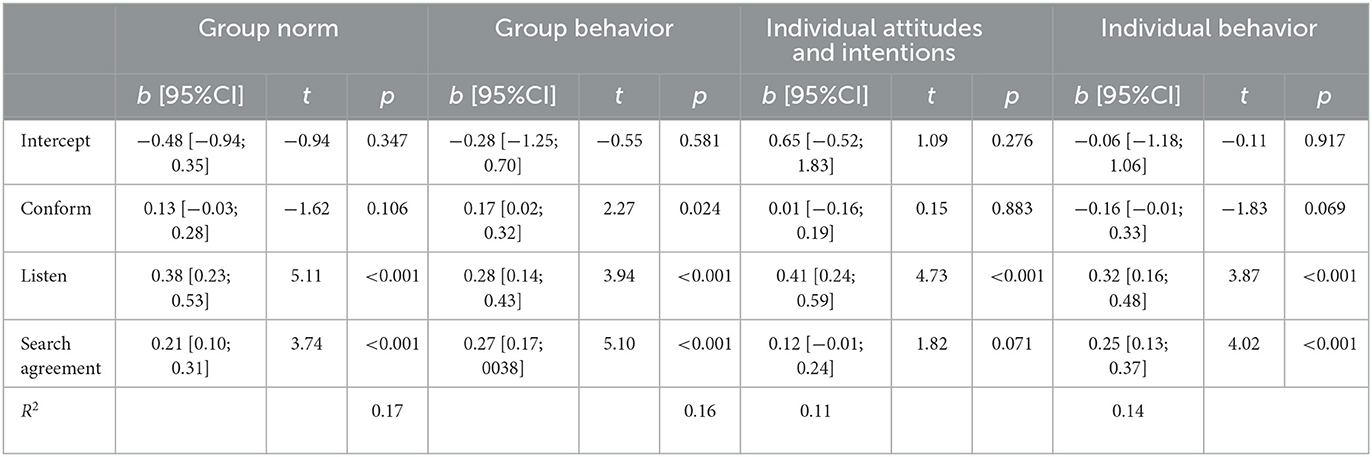

Including all three anticipated group dynamics simultaneously in a regression revealed that anticipated listening was related to increased veganism on all four social influence indicators. Anticipated searching for agreement positively predicted both veg*n group norms, and group and individual behaviors, while the effect on individual intentions and attitudes was marginally significant. No clear pattern was observable for anticipations of conformity pressure: it significantly, but positively, predicted veg*n group behavior, but was unrelated to the other variables, although a marginally significant negative effect appeared for individual behaviors. Together, the variance explained by the anticipated group dynamics was 17% for group norms, 16% for group behavior, and 14% for individual behavior, and 11% for individual attitudes and intentions (see Table 7).

Table 7. Study 3. Regression results of veg*n group norms, group behavior, individual attitudes, intentions and individual behavior on the group dynamics conformity pressure, listening and searching for agreement.

Content analyses

Two regression analyses on the content coding of acceptance showed that value in diversity positively predicted whether the deviant was accepted by the participant, b = 0.10 (0.01;0.19), t(305) = 2.13, p = 0.034, and by their group, b = 0.12 (0.03;0.22), t(305) = 2.62, p = 0.009.

Two binomial logistic regressions demonstrated that diversity value did not significant predict whether the group was tolerant to the deviant's perspective (nyes = 219, nno = 89), Exp(B) = 1.14, 95% CI (0.86;1.50), Wald(1) = 0.80, p = 0.370, Nagelkerke R2= 0.004. However, value in diversity significantly predicted the extent to which participants mentioned their groups searched for agreement with the deviant (nyes = 47, nno = 261), Exp(B) = 1.54, 95% CI 1.01;2.33), Wald(1) = 4.13, p = 0.042, Nagelkerke R2= 0.026.

Finally, we conducted a nominal logistic regression on the restaurant choice. No mention of vegan options was used as a reference category (n = 63, 20.5%). We tested whether value in diversity predicted the likelihood of choosing a restaurant with multiple dietary options (n = 204, 66.4%), and the likelihood of choosing a restaurant mostly veg*n options (n = 40, 13.0%). The model fit marginally significantly increased by adding value in diversity to a model that included the intercept and the covariate value in similarity, χ2(2) = 5.91, p = 0.052. Parameter estimates suggest that value in diversity does not significantly increase the likelihood of selecting a restaurant with multiple dietary options, Exp(B) = 1.275 95% CI (0.93;1.75), Wald(1) = 2.27, p = 0.132, but increases the likelihood of selecting a restaurant with predominantly veg*n options, Exp(B) = 1.82, 95% CI (1.10;3.03), Wald(1) = 5.33, p = 0.021.

Discussion

Study 3 replicates the results in a setting in which an existing friend introduces a minority perspective. Furthermore, it extends the findings about social influence on general group norms and personal intentions, by showing that valuing diversity predicts very concrete expectations of group members' behavior during the dinner, for instance, whether they are inclined to order a vegan dish.

Third, it provides more insight in the processes that explain why deviants may face less rejection in groups that highly value diversity. Indeed, value in diversity predicts group members belief that shifting to a vegan diet not merely reflects a change of behavior, but poses a threat to the customs, traditions, and identity of a group. This suggests that, with increasing value in diversity, a group's identity becomes less defined by what makes group members similar (that we all like to barbecue), but more by the unique insights group members bring to the table (Jans et al., 2012).

Finally, findings regarding the anticipated group dynamics were further validated by qualitative analyses of participants' descriptions of the dinner with the deviant friend. For instance, value in diversity positively related to participants' anticipation that their group would search for agreement with the deviant. This was also reflected in the choice of restaurants: value in diversity positively predicted the preferences of a vegan restaurant over restaurants with multiple dietary options. Interestingly, few participants explicitly mentioned conformity pressure (perhaps they were reluctant to acknowledge that this occurred, or they might be unaware of subtle pressure, Koudenburg et al., 2013), and most participants anticipated their groups to tolerate the vegan group member regardless of whether they valued diversity. This corroborates our quantitative results that valuing diversity, beyond tolerating differences, comprises the active integration of a deviant viewpoint.

General discussion

When can a minority sway a group? The present paper departs from cognitive intra-individual approaches, by examining the group dynamics involved in minority influence. Three studies demonstrate that higher perceived group value in diversity is associated with more acceptance of deviant perspectives, and with the experience and anticipation of group dynamics that promote social change. Jointly, the findings provide important and novel insights into the process and conditions of minority influence.

First, corroborating previous research (e.g., Hutchison et al., 2011), we find that groups' value in diversity positively predicts the extent to which a deviant is accepted (Study 2–3; but not in Study 1). Importantly, diversity value predicts higher acceptance for a type of deviance generally associated with strong derogation. Specifically, while the results Study 2 corroborate the general finding that adhering to a vegan diet lowers acceptance (e.g., MacInnis and Hodson, 2017), this effect is moderated by group value of diversity. Similarly, previous research suggests that existing group members face stronger derogation than newcomers (Pinto et al., 2010), but we find value of diversity to be positively related to the acceptance of both newcomers (Study 2) and existing group members (Study 3). Group value in diversity seems to lower the threat to the group's identity posed by moral (e.g., vegans) and ingroup deviants (Study 3).

Second, extending these previous findings, we show that value in diversity not merely reflects a celebration of differences (in the sense that ‘we agree to disagree'), but that deviants in such groups are key motivators for a reconsideration and renegotiation of groups norms and individual behavior, and as such, increase the potential for social change to occur. Specifically, in all three studies, we found that perceived group value in diversity predicted a change toward veg*nism (a type of minority influence previously considered unlikely because of the threat these moral deviants pose; Kurz et al., 2020). This change was found on the individual level, on attitudes and intentions (and marginally on behaviors) to eat veg*n (Study 1–3), and on related pro-environmental intentions. Minority influence tends to be particularly visible on related behaviors or opinions (and not the targeted one), reflecting divergent or systematic processing of deviant perspectives, within the confines of conformity pressure (Moscovici, 1976; Nemeth, 1986; Crano and Chen, 1998). However, we find the targeted attitudes and intentions to be just as affected as related ones, suggesting that while the minority perspectives may have instigated higher levels of processing, influence was not restricted by conformity pressure. In fact, we have reason to believe that change was instigated by a group's public consideration of, and elaboration on, minority views, and reflected individual experiences of a group process, rather than a purely individual process. Indeed, Study 2–3 show that groups' value in diversity predicted the development of veg*n group norms (Study 2–3) and veg*n group behavior during a dinner with a vegan deviant (Study 3).

While majority influence is often considered the result of a group's pressure to conform, the factors predicting minority influence are often studied at the intra-individual level: (individual) change may occur when group members perceive a conflict (Moscovici, 1976), and have time to individually reflect, or engage in divergent thinking, about the minority perspective (Nemeth, 1986). Our findings challenge the notion that minority influence is an indirect, delayed and private process, by demonstrating that minorities also motivate social change through open group discussion in which members experience their group to listen to deviant perspectives and, importantly, view these perspectives as valuable input to update group norms and practices.

The present paper uniquely considers three experienced and anticipated group dynamics that enable minority influence. First, valuing diversity related to the experience and anticipation of reduced conformity pressure to the deviant (Study 2–3, but not Study 1, see discussion section Study 1), which is a crucial first step to make room for minority influence, as it is considered the key reason for why minorities are often disregarded (Moscovici, 1976). While a reduced pressure to conform can be perceived as an increased tolerance to deviant perspectives, it does not necessarily mean that groups are influenced by these perspectives. All three studies therefore pointed to a second dynamic: Listening. In contrast to the typical ignorance and rejection of deviant views, groups that value diversity are more expected to, listen to deviant perspectives. The final group dynamic, searching for agreement departs from the interpretation of diversity value as the “celebration of differences”. Indeed, while celebrating differences may increase the acceptance of deviants, it may also mitigate their influence, because the differences between members is what connects them (see Jetten et al., 2002; Jetten and Postmes, 2006). Therefore, to induce social change, it is considered crucial that a group is seen to be motivated to search for agreement with the deviant. Perhaps somewhat paradoxically, evidence across all three studies shows that participants' belief that their group is searching for agreement with a deviant increases to the extent that a group values diversity. We infer that to learn from a deviant perspective, group members need to actively engage with that perspective, in an aim to consensualise on matters important to the group (for similar ideas in an organizational context, see Ely and Thomas, 2001; in a cultural context, see Kunst et al., 2015). A true value in diversity, then, goes beyond tolerance or celebration of differences, but contains a true interest in learning from deviant perspectives, and integrating them into group norms, values, and identities.

One interesting observation was the consistent positive relation between our measure of value in diversity and value in similarity in both Study 2 and Study 3. This corroborates previous findings, and indicates that we should consider the two as separate constructs (Ofori-Dankwa and Julian, 2002). This also suggests that valuing diversity does not involve the devaluation of similarity. Indeed, our finding that valuing diversity increases the search for agreement corroborates this idea, and further suggests that a true value of differences may go beyond the toleration of different viewpoints (in the sense that “we agree to disagree”) to a recognition of the value in engaging with diverse perspectives for optimizing shared solutions and viewpoints. In a sense, understanding that valuing diversity does not threaten the value of similarity, but that the two can, in fact, go hand in hand, may reduce the threat that diversity poses to the experienced shared identity (see also Jans et al., 2012).

Limitations and future directions

While Study 1 measured participants' perceptions of the group's value in diversity, Study 2–3 introduced a novel manipulation for this concept. With a nudging method, we increased participants' perceptions of the value their friend group attached to diversity, and through that, increased the influence of a vegan deviant on individual and group change toward veg*nism. Note that, while the manipulation indirectly predicted the social change variables by increasing value in diversity, no evidence for a direct effect was obtained. While an indirect effect in the absence of a direct effect should be taken seriously (e.g., Rucker et al., 2011), it also points to the possible existence of a suppression effect. Possibly, while groups that value diversity may be seen as more open to listen to deviant viewpoints, there could be a second pathway for change in the opposite direction. Specifically, low value in diversity may increase the threat that is posed by deviant views, which could be resolved by either rejecting the deviant (as we argued before), or, by accepting the deviant and shifting the group norms to include the deviant views. While the latter strategy occurs rarely (indeed, value in diversity decreased the acceptance of deviants), when it occurs, it should result in a shift of the group norm toward the deviant perspective, albeit through a different process (REF BLINDED). Possibly, influence occurs through different pathways: Whereas, groups high in diversity value may gradually change, through a process of open deliberation on multiple perspectives, groups that place little value in diversity may be more likely to change radically, through conformity similar to majority influence, after a certain tipping point has been reached (cf. Muthukrishna and Schaller, 2019 for a similar argument in cultural psychology). Future research could examine such trajectories of social change in longitudinal designs.

Another limitation is our focus on the anticipation of group dynamics in two of the three studies, and we are unsure whether these resemble actual experienced group dynamics. Indeed, previous research from other areas of psychology suggests that the anticipation vs. the experiences may have different consequences in terms of, for instance, academic success or interaction enjoyment (Duffy et al., 2018; Beymer et al., 2023). To validate our findings of the anticipated group dynamics in Study 2 and 3, it is important to point out that they replicated the findings on actual conversational experiences in Study 1 – which is in line with results of a meta-analysis on the influence of imagining conversational dynamics in changing attitudes (Miles and Crisp, 2014). Beyond that, we think that examining both experience and anticipation has predictive value in terms of social change. Indeed, oftentimes, people may decide (not) to change their behavior or attitude just because they believe that relevant others will respond to such change in a certain way. The influence of these perceived norms is a highly relevant predictor of behavior and subsequent norm change (e.g., Prentice and Miller, 1993).

Because our study made use of confederates and vignette studies in which the role of the deviant was relatively standardized, we could not examine how the behavior of the deviant minorities may be affected by their group's value of diversity. We would expect that group climates in which diversity is valued, people might me more willing to speak up to change the course of the group in the “right” direction (e.g., Bolderdijk and Jans, 2021). By affecting both the behavior of the deviant, and the group dynamics in response to such deviance, valuing diversity may create a positive spiral toward social change.

Conclusion

Addressing societal challenges like climate change requires social norms to shift toward increased sustainable behavior, which raises the urgency for research into the creation and development of social norms (van Kleef et al., 2019). Experimental work has pointed to the pivotal role of small group dynamics in shaping social norms (Titlestad et al., 2019; Koudenburg et al., 2020). The present research demonstrates the how the experienced and anticipated dynamics in small groups can foster, or hamper the possibility for vegan deviants to sway their group toward more sustainable norms. Three studies demonstrated that valuing diversity in groups predicts the experience of three group dynamics that increase a deviant's influence: a reduced pressure to conform, increased listening, and an active search for agreement with the deviant. This suggests that when groups value diversity, they do not just tolerate, or celebrate, they are perceived to do more: valuing diversity entails the careful integration of different viewpoints to develop a novel shared perspective.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article is accessible at dataverse.nl, via https://doi.org/10.34894/WKLYOR. Any further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of Psychology, University of Groningen. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

NK and LJ developed the research idea and study designs together. NK conducted the studies together with students, analyzed the data, and wrote the first draft of the paper. LJ provided feedback and revised the paper. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the Dutch Research Council (NWO), through grant number 451-17-011, granted to NK.

Acknowledgments

We thank Iris Gietema, Alena Goede, and Bence Nagy for their assistance in conducting the research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsps.2023.1240173/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^While Itzchakov et al. (2020) focus on reducing the within-person defensiveness of negative or inconsistent viewpoints by being responded to with high-quality listening, the present research focuses on the group level. Here, the same may apply: when inconsistent or deviant views within groups are met with high-quality listening, they present an opportunity for change.

2. ^We reasoned that groups of three would be the minimum group size to allow for group dynamics between a minority and majority to occur, while affording sufficient power to test the hypotheses (forming larger groups with a similar sample size, would negatively impact power). The median friend group size of five participants reported in Study 2 and 3 supports this decision.

3. ^It is possible that these participants have changed the norm within their respective groups to be more vegan to begin with. Ideally, we would have excluded not only the vegan deviants, but also their groups from the analysis. We decided to keep them in for two reasons: (1) removing these groups would reduce the power of the study, (2) while the influence of value in diversity on vegan attitudes and behaviors may be different, the influence on group dynamics (which in Study 1 did not directly refer to the vegan deviant, but deviant behavior in general) should be equal. Importantly, excluding all groups with an additional vegan participant did not reduce the b-coefficients of any of the reported effects, and all reported effects remained statistically significant.

References

Beymer, P. N., Flake, J. K., and Schmidt, J. A. (2023). Disentangling students' anticipated and experienced costs: The case for understanding both. J. Educ. Psychol. 115, 624–641. doi: 10.1037/edu0000789

Bolderdijk, J. W., and Jans, L. (2021). Minority influence in climate change mitigation. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 42, 25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.02.005

Butera, F., Falomir-Pichastor, J. M., Mugny, G., and Quiamzade, A. (2017). “Minority influence,” in The Oxford Handbook of Social Influence, eds S. G. Harkins, K. D. Williams, and J. M. Burger (Oxford: Oxford University Press),317–337.

Crano, W. D., and Chen, X. (1998). The leniency contract and persistence of majority and minority influence. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 74, 1437–1450. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1437

De Dreu, C. K. (2002). Team innovation and team effectiveness: the importance of minority dissent and reflexivity. Eur. J. Work Org. Psychol. 11, 285–298. doi: 10.1080/13594320244000175

Dhont, K., and Hodson, G. (2014). Why do right-wing adherents engage in more animal exploitation and meat consumption? Pers. Individ. Diff. 64, 12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.02.002

Duffy, K. A., Helzer, E. G., Hoyle, R. H., Fukukura Helzer, J., and Chartrand, T. L. (2018). Pessimistic expectations and poorer experiences: The role of (low) extraversion in anticipated and experienced enjoyment of social interaction. PLoS ONE. 13, e0199146. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199146

Ellemers, N., and Jetten, J. (2013). The many ways to be marginal in a group. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 17, 3–21. doi: 10.1177/1088868312453086

Ely, R. J., and Thomas, D. A. (2001). Cultural diversity at work: the effects of diversity perspectives on work group processes and outcomes. Admin. Sci. Q. 46, 229–273. doi: 10.2307/2667087

Graça, J. (2021). Opposition to immigration and (anti-)environmentalism: an application and extension of the social dominance-environmentalism nexus with 21 countries in Europe. Appl. Psychol. 70, 12246. doi: 10.1111/apps.12246

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. London: Guilford publications.

Higgs, S., and Ruddock, H. (2020). Social influences on eating. Handb. Eating Drink. Interdis. Persp. 4, 277–291. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-14504-0_27

Hollander, E. P. (1958). Conformity, status, and idiosyncrasy credit. Psychol. Rev. 65, 117–127. doi: 10.1037/h0042501

Homan, A. C., van Knippenberg, D., Van Kleef, G. A., and Dreu, D. C.K.W. (2007). Bridging faultlines by valuing diversity: diversity beliefs, information elaboration, and performance in diverse work groups. J. Appl. Psychol. 92, 1189–1199. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.5.1189

Hornsey, M. J. (2006). “Ingroup critics and their influence on groups,” in Individuality and the Group: Advances in Social Identity, eds T. Postmes and J. Jetten (.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc), 74–91.

Hutchison, P., Jetten, J., and Gutierrez, R. (2011). Deviant but desirable: group variability and evaluation of atypical group members. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 47, 1155–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2011.06.011

Ilmarinen, V. (2021). Consistency and variation in the associations between refugee and environmental attitudes in European mass publics. J. Environ. Psychol. 73, 1540. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101540

Itzchakov, G., Weinstein, N., Legate, N., and Amar, M. (2020). Can high quality listening predict lower speakers' prejudiced attitudes? J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 91, 104022. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2020.104022

Jans, L., Koudenburg, N., Dillmann, J., Wichgers, L., and Postmes, T. (2019). Dynamic reactions to opinion deviance: The role of social identity formation. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 84, 1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2019.04.001

Jans, L., Koudenburg, N., and Grosse, L. (2023). Cooking a pro-veg* n social identity: the influence of vegan cooking workshops on children's pro-veg* n social identities, attitudes, and dietary intentions. Environ. Educ. Res. 6, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2023.2182750

Jans, L., Postmes, T., and Van der Zee, K. I. (2012). Sharing differences: the inductive route to social identity formation. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 48, 1145–1149. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2012.04.013

Jetten, J., and Hornsey, M. J. (2014). Deviance and dissent in groups. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 65, 461–485. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115151

Jetten, J., and Postmes, T. (2006). “I did it my way”: collective expressions of individualism, in Individuality and the Group: Advances in Social Identity, eds T. Postmes and J. Jetten (London: Sage Publications, Inc), 116–136.

Jetten, J., Postmes, T., and McAuliffe, B. J. (2002). ‘We're all individuals': Group norms of individualism and collectivism, levels of identification and identity threat. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 32, 189–207. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.65

Kane, A. A., and Rink, F. (2015). How newcomers influence group utilization of their knowledge: Integrating versus differentiating strategies. Group Dyn. Theor. Res. Prac. 19, 91–105. doi: 10.1037/gdn0000024

Koudenburg, N., Kannegieter, A., Postmes, T., and Kashima, Y. (2020). The subtle spreading of sexist norms. Group Proc. Interg. Relat. 24, 1467–1475. doi: 10.1177/1368430220961838

Koudenburg, N., Postmes, T., and Gordijn, E. H. (2013). Resounding silences: subtle norm regulation in everyday interactions. Soc. Psychol. Q. 76, 224–241. doi: 10.1177/0190272513496794

Kunst, J. R., Thomsen, L., Sam, D. L., and Berry, J. W. (2015). “We are in this together”: common group identity predicts majority members' active acculturation efforts to integrate immigrants. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bullet. 41, 1438–1453. doi: 10.1177/0146167215599349