95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sleep , 28 November 2024

Sec. Pediatric and Adolescent Sleep

Volume 3 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frsle.2024.1459349

This article is part of the Research Topic Women in Pediatric and Adolescent Sleep: Volume II View all 8 articles

Objectives: To identify factors to optimize long-term non-invasive ventilation (LT-NIV) use by exploring the experience of children using LT-NIV and their parents.

Study design and methods: A qualitative framework analysis method was used. Children aged 8–12 years who used LT-NIV for at least 3-months and their parents/guardians were approached to participate. Thematic analysis of data derived from focus group interviews, conducted separately for children and parents, was performed. Findings were coded and grouped into identified themes.

Results: Data analysis identified four themes: (1) “The double-edged sword,” which identified benefits and challenges of LT-NIV use; (2) “Feeling different,” where children and parents described fears, frustrations, and concerns including emotional and social implications, and physical changes; (3) “It's not just about the mask,” highlighted the influence of equipment issues, including the mask interface, headgear, tubing and humidity, and their impact on tolerance and use of LT-NIV; and (4) “Through the eyes of experience—children and parents as experts for change,” which captured ideas for the functional and aesthetic improvement of the equipment including the need for pediatric specific technology.

Conclusions: LT-NIV use has two sides; it helps to improve lives though requires an investment of time and commitment to ensure success. Investing in pediatric-specific equipment needs to be a priority as do alliances between healthcare providers, children who use LT-NIV, and their families. Future technology development and studies of adherence need to consider the experiences of children and their families to reduce the challenges and support optimal use of LT-NIV.

Long-term non-invasive ventilation (LT-NIV), including both continuous and bilevel positive airway pressure (CPAP, BPAP), has become standard of care for children with a wide range of sleep-related breathing disorders and children with chronic respiratory insufficiency or failure (Fauroux et al., 2022; Castro-Codesal et al., 2018a; Windisch et al., 2018). Indications for LT-NIV use have expanded and include children with a broad range of medical complexity (Tan et al., 2020; Pavone et al., 2020; Castro-Codesal et al., 2018b). A scoping review of LT-NIV use in children identified 73 medical conditions for which LT-NIV was used (Castro-Codesal et al., 2018a). While LT-NIV can improve survival, respiratory events and gas exchange, and reduce hospitalization, the need for invasive ventilation, and airway surgery, it also presents challenges for children and their families (Windisch et al., 2018; Hudson et al., 2022; AlBalawi et al., 2022; Bedi et al., 2018a).

Adherence to LT-NIV is challenging for children and adults. The majority of data on adherence stems from studies of CPAP use for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and show that the average usage of CPAP for nocturnal users is < the night (Adeleye et al., 2016; Perriol et al., 2019; Machaalani et al., 2016; Patil et al., 2019; Bhattacharjee et al., 2020; Castro-Codesal et al., 2020; Bedi et al., 2018b). Adherence to LT-NIV is a complex issue impacted by a range of factors, including health-related factors, psychosocial circumstances, and the interaction with the technology (Perriol et al., 2019; Pascoe et al., 2019; Katz et al., 2020; Hurvitz et al., 2023). Qualitative studies in adolescents show early adaptation and fewer difficulties around initiation promote continued use while negative experiences, technical and comfort issues, and side effects increase non-adherence risk (Prashad et al., 2013; Ennis et al., 2015; Alebraheem et al., 2018). Whether adolescents' experiences reflect the overall experience of LT-NIV use in children is unclear. The aim of this study is to understand the experience of using LT-NIV from the perspectives of pre-adolescent children and their parents with lived experience. The results will provide insight into improving the ease of use and optimizing adherence in children using LT-NIV.

This is a descriptive, qualitative study. Focus group interviews, recognized as a developmentally appropriate and valid approach in children as young as 6 years of age, were utilized for data collection (Kennedy et al., 2001). The study protocol was approved by the Human Research Ethics Board (Pro00050876). All children and their parents/guardians provided informed assent and consent, respectively. The LT-NIV clinic team was composed of respiratory and sleep physicians, a nurse practitioner, and a respiratory therapist. Strategies to establish and support on-going use of LT-NIV include education, mask desensitization, customization of head-gear, and both in-person and virtual follow-up. All children underwent mask selection and fitting in the LT-NIV clinic.

Focus group participants were recruited through a multi-disciplinary tertiary care LT-NIV program. This included all children aged 8–12 years who were established on LT-NIV (i.e., minimum 3-months use outside an acute care setting) and their parents who were invited to participate via a letter sent from the LT-NIV clinic team that included a return-addressed envelope and an email to respond to the study team. Parents who expressed interest were contacted by phone to confirm their participation and the parent's and child's ability to understand and converse in English. After obtaining informed consent and assent, parents completed a health screening questionnaire for their child including information about NIV use with adherence assessed based on the most recent NIV machine download for a period of 2 weeks to 2 months.

Focus groups were conducted in-person and separately for children and parents by a facilitator who had no direct clinical interaction with the participants (AC, JK) using a semi-structured interview guide (see Supplementary material). Focus groups were conducted in a university conference room, were digitally recorded, and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were anonymized prior to analysis.

Framework analysis, a qualitative method that uses content analysis to capture and organize descriptive data, was chosen for this study. It uses an inductive and iterative approach to data analysis, with findings organized through coding and indexing from within the original dataset (Ward et al., 2013). The interview guide was created by three members of the research team who provide care to children using LT-NIV (DO, AC, and JEM). None of the researchers were parents of children using LT-NIV. During analysis, themes capturing the described experiences of children and their parents were identified along with recurring patterns of common descriptions. Two investigators (AC, DO) independently reviewed the transcripts and completed initial coding of the data. Conceptually related codes were grouped, leading to the emergence of the main themes, which became the analytical framework for data analysis. This framework was refined and applied to each transcript until no new code was identified. Transcripts were repeatedly reviewed by both researchers to ensure consistency within the final coding and themes. Reporting of the results followed the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR; O'Brien et al., 2014).

Focus groups were completed on 2 separate days with nine child-parent dyads and three parents of children who were unable to participate because of developmental delay. The characteristics of the children using LT-NIV are summarized in Table 1. The most common reason for LT-NIV use was OSA and all but one child had comorbidities. This included three children with asthma, seven with neurodevelopmental disorders (including two with Down syndrome) and one with congenital heart disease. Comparing the characteristics of the children to a description of children using LT-NIV in Alberta, Canada shows that the participants were representative of this population (Castro-Codesal et al., 2018b). Mask fit, mask leak, and skin irritation were rated favoraly by the majority of parents (Table 1). Two parents reported at least occasional skin breakdown with the current mask. Of the 12 parents, 10 were mothers and 2 were fathers. The length of the transcripts was 33 and 45 min for the child focus groups, and 55 and 69 min for the parent focus groups. Data analysis identified 36 codes across four themes.

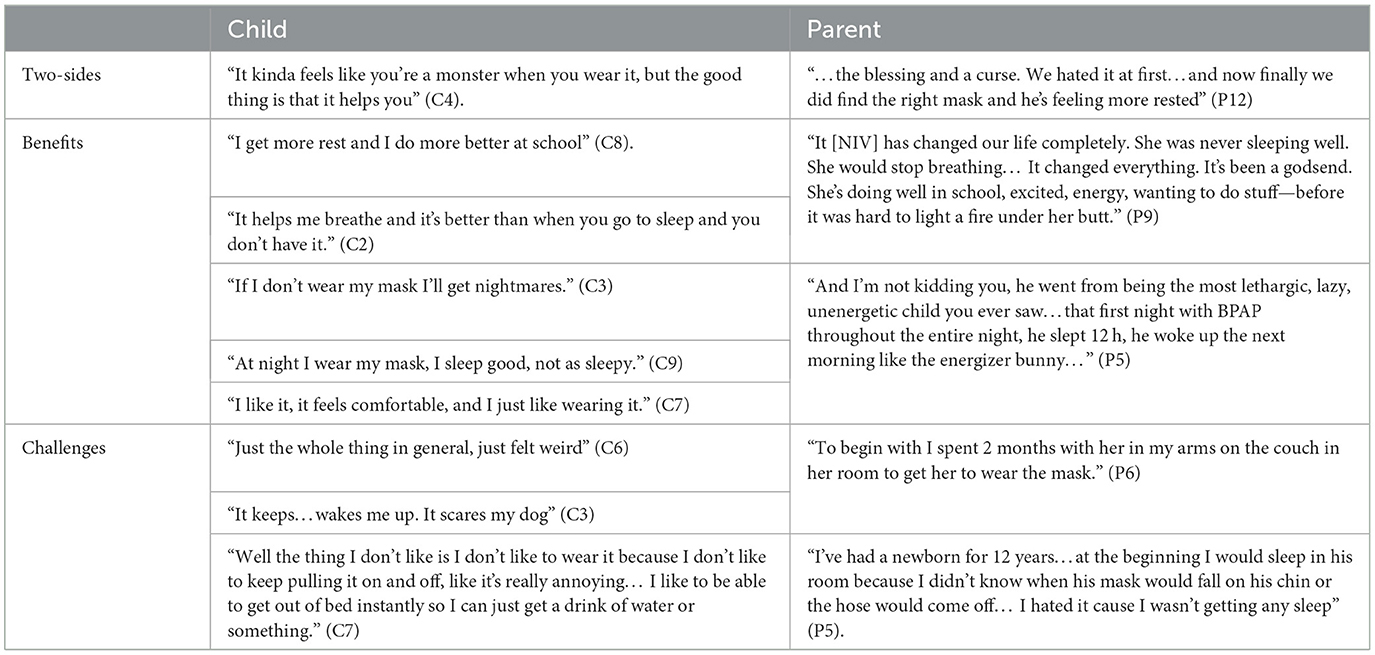

The children and parents' narratives described the benefits and challenges of NIV use (Table 2). The experience of using LT-NIV was perhaps best elucidated in a parent's quote, “It's a double-edged sword” (P5).

Table 2. Representative quotes for theme 1—“the double-edged sword” of using long-term non-invasive ventilation.

Children identified that LT-NIV helped them sleep better and feel more rested, although it was not easy to use. Some children focused on the benefits of using their LT-NIV to their sleep as well for their days. Conversely, children expressed their dislike for having to wear LT-NIV, sharing their preference to sleep without it admitting, “If my mom and my dad leaves, I sneak take my mask off.” (C3). They admitted to not always wanting to wear their LT-NIV and wondered whether they would have to use it forever.

Parents shared more about the challenges of first initiating LT-NIV than children. For most, the experience was one of struggle but also determination to be successful. Parents related the impact and challenges, both initially and with on-going use, seeing improvements in their child's sleep, energy, growth, and quality of life. One parent described how her daughter “…is 10 but she's the size of a 5-year-old. So she didn't start to grow til she start to sleep [using NIV].” (P4). Although some children did well from the outset, significant challenges were identified by parents around initiation of LT-NIV. Establishing LT-NIV use could be a long process with one parent describing that “We started with my son in 30 s increments, it took us 2 years before he made it to one solid night.” (P5).

Parents identified struggles with their own interrupted sleep and reduced quality of life—not only during the initiation, but also with ongoing requirements for monitoring and readjusting equipment throughout the night. One parent admitted that even after years of use, “I usually check [NIV] every 2 h, I get up” (P6). Reflecting on what it would be like if their child could be successful with LT-NIV, one parent described “…her waking up refreshed on her own, functioning well in the school day and growing and being healthy and happy. I think that's what I'd love to see, and then we could all sleep, which would be miraculous” (P4). Another parent expressed that if their child's LT-NIV therapy were ideal “Life would be glorious. We would have happy children. We would sleep. We would enjoy life” (P5).

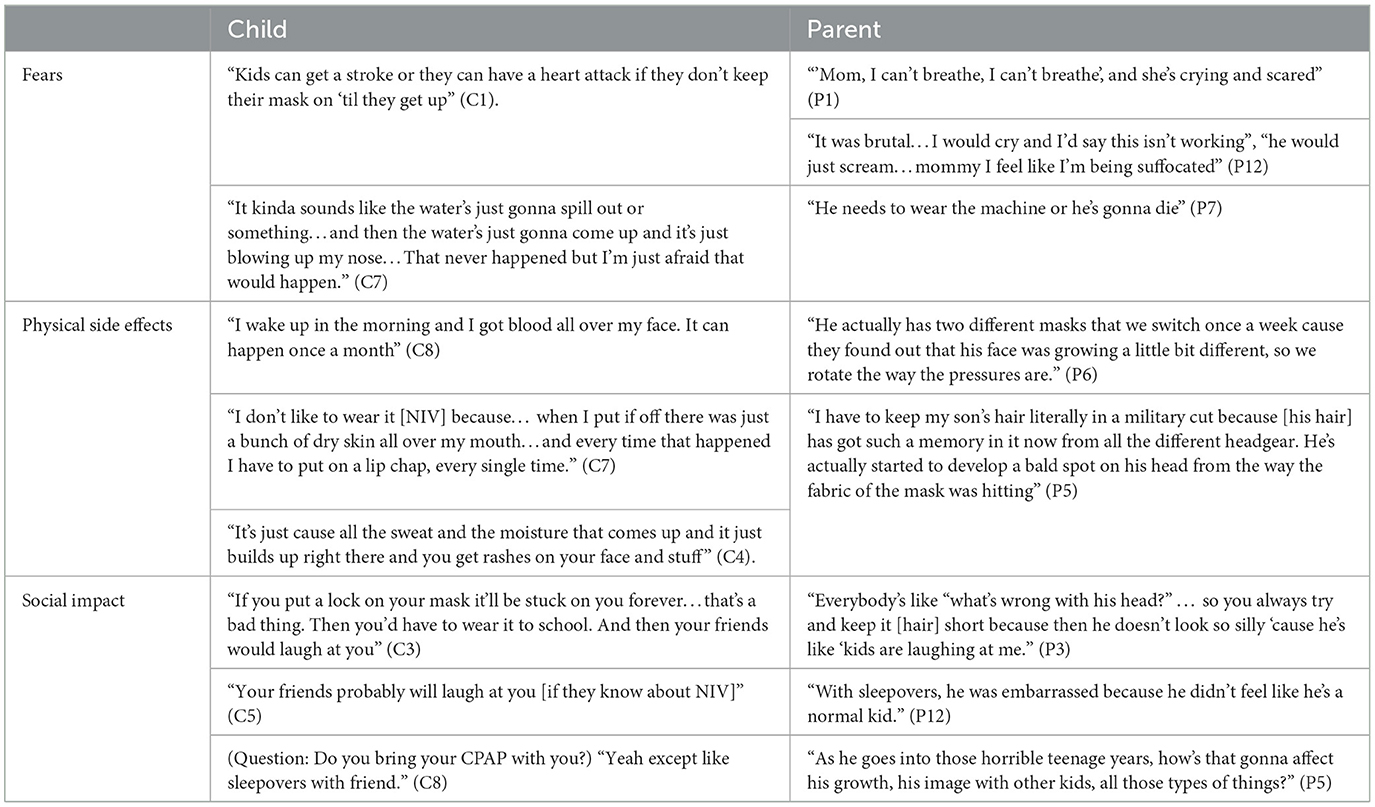

Emotional reactions to using LT-NIV were emphasized throughout the focus groups (Table 3). Fears expressed mostly centered around adjusting to LT-NIV therapy itself with descriptions such as being “scared” (C9), “absolutely terrified of [their] mask” (P7) along with the terms “claustrophobic” or “suffocated.”

Table 3. Representative quotes for theme 2: “feeling different” using long-term non-invasive ventilation.

Frustrations primarily focused on the physical side effects experienced, including hair changes, nosebleeds, facial irritation, and rashes. Parental accounts mostly reflect concerns regarding the long-term consequences of physical changes. This included facial marking and changes in facial shape with one mother sharing “He's actually started to develop a bald spot on his head from the way the fabric of the mask is hitting. And seeing my son develop a bald spot nearly broke my heart” (P5). Several parents expressed frustration related to healthcare providers not understanding the impact of LT-NIV therapy and giving inconsistent medical advice. One mother shared, “I think sometimes the doctors don't understand what it's like to be a mother or father of a child with these issues because they don't have a child themselves to relate to, or they have never strapped one even on their own face to understand what the child's going through” (P5).

Children and parents expressed further concerns about the potential social impact of using LT-NIV. Being seen as different and admitting to hiding their LT-NIV use from friends was shared by several children through statements such as, “I haven't told them [friends] cause I'm new at school” (C1). Similar concerns expressed by parents include noticing “She hides her stuff when friends come over. It makes her feel different” (P8). Another parent noted “He gets some anxiety about people seeing that…I think that because people say what's that from, why do you have that rash on your face…they're noticing now whereas before they didn't really notice…I think that for him that part of it kinda bothers him” (P11). Parents also anticipated that social concerns might increase in the teenage years.

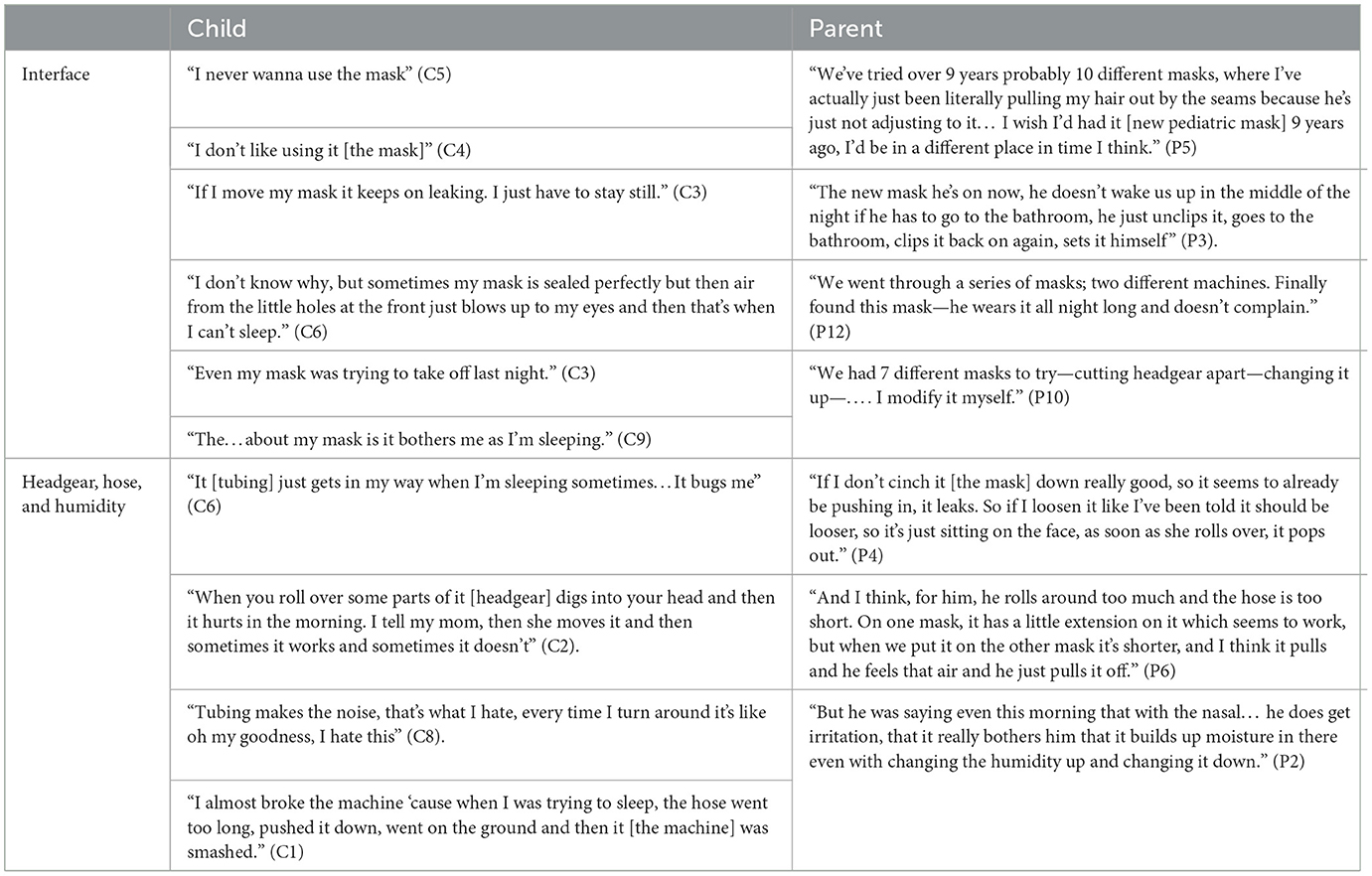

Disclosure on the challenges with LT-NIV use for children often centered around masks, machines, and associated equipment (Table 4). Although mask issues were at the forefront, headgear, tubing, and humidity issues were also described by both children and parents.

Table 4. Representative quotes for theme 3: it's not just about the mask—the challenges of non-invasive ventilation equipment.

Several children shared not liking their masks. A common thread was the number of masks that a child had to try before achieving a suitable fit. Parents did recognize that getting the right equipment for their child was important, but the journey to get there could be long. Mask leaks were a common discussion point. The arrival of newer pediatric masks was described as having a positive impact on tolerance for most children. Headgear also generated discussion among children and parents and was often linked to physical changes caused by the mask fit.

NIV tubing and humidity issues were commonly described by children and parents as having a significant effect on tolerance. One child explained, “Look I hate the hose because every time I try to fall asleep the hose pops off and I don't even notice. And it goes way, way, I'm like what? I'm like Dad. I scream Dad” (C3). Side effects attributed to humidity levels were described by both children and parents. Excess humidity contributed to facial rashes and irritation, with nosebleeds occurring in several children and attributed to low humidity.

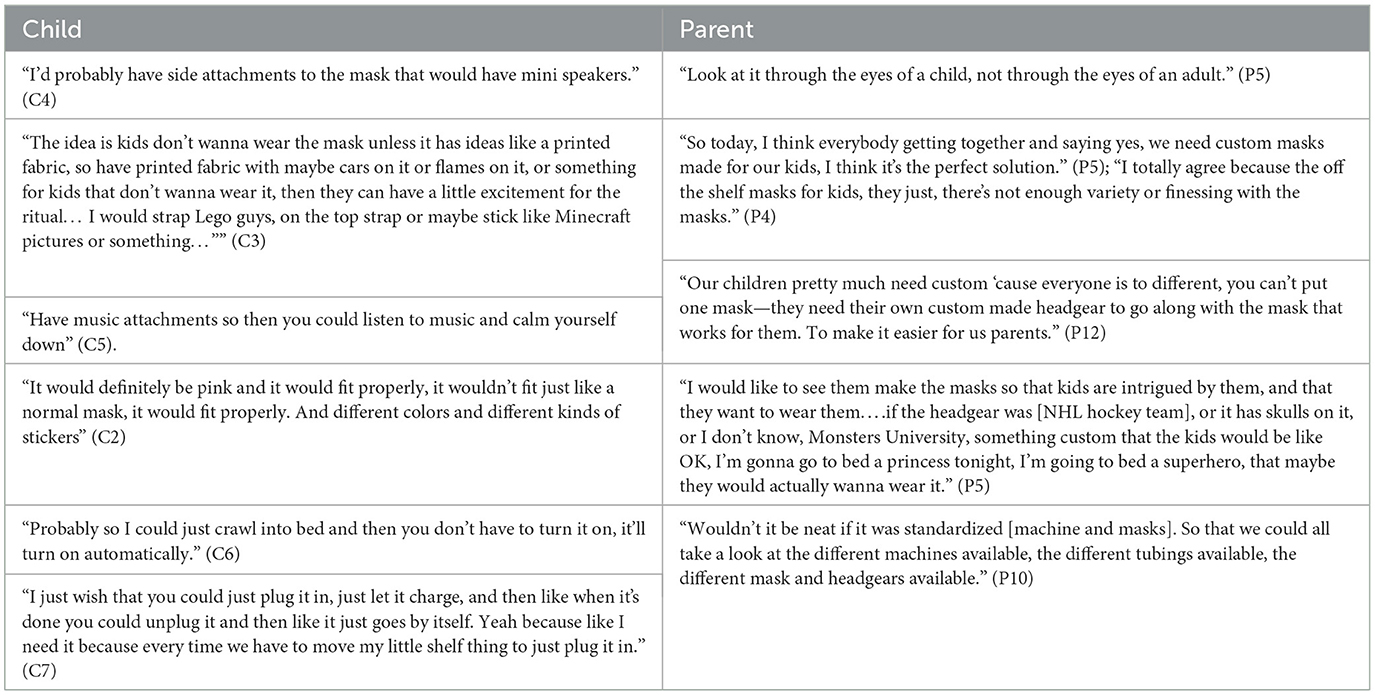

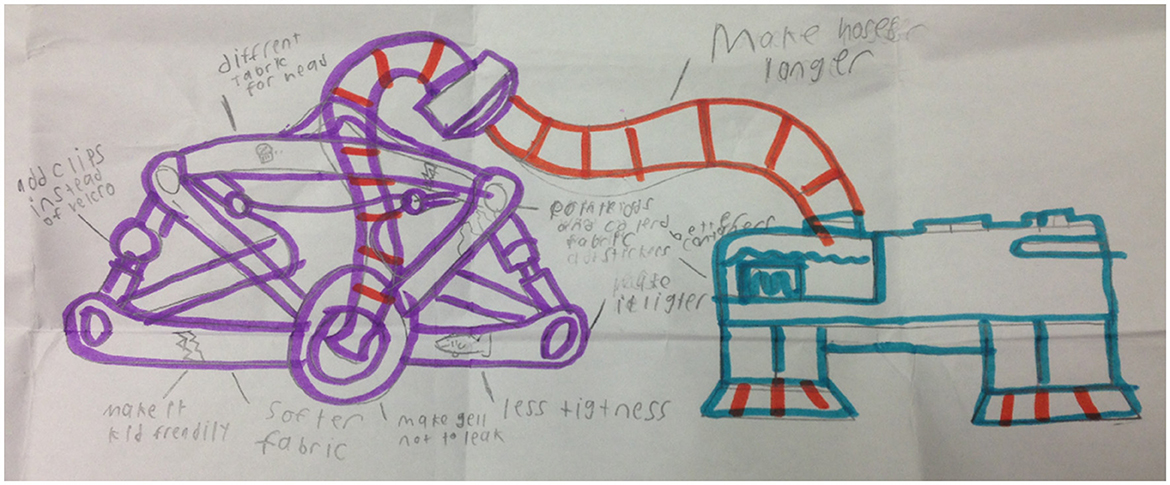

Children and parents had many suggestions for improving LT-NIV technology (Table 5). Children had ideas for child-friendly designs that focused on the aesthetics of NIV equipment. Other discussion focused on the entertainment potential with children suggesting incorporating radios, speakers, and video players, while others recommended choosing colors, stickers and cartoon characters. Other suggestions focused on improving the comfort or side effects of the mask. These included making the headgear and mask softer, preventing skin irritation from the mask and humidity, and modifying the tubing so it did not come apart. A drawing depicting one child's vision of the perfect NIV equipment reflects thoughtful and exacting detail based on his experience using NIV (Figure 1).

Table 5. Representative quotes for theme 4: through the eyes of experience—children and parents as experts for change.

Figure 1. “My ideal BPAP equipment” drawn by 11-year-old study participant (consent obtained to reproduce).

In contrast, parents focused more on the need for equipment designed to improve their child's acceptance and tolerance of LT-NIV. Parents' suggestions focused on proper pediatric-sized masks and minimizing the side effects of LT-NIV. They generally felt that the current LT-NIV equipment was insufficient to meet the needs of their children. The need for comfortable, well-fitting pediatric-specific equipment with child friendly designs was important to parents.

Despite the challenges and struggles captured within the narratives, both children and their parents revealed underlying perseverance and resiliency. LT-NIV initiation and adherence requires commitment and time from children and their parents to overcome significant emotional, physical, and social challenges associated with LT-NIV use. Even with discussion of significant negative experiences with LT-NIV and equipment challenges, participants reported benefits of LT-NIV.

The “double-edged sword” identified by both children and parents in this study echoes findings from other studies of the experience of children using home mechanical ventilation (HMV). For children using HMV, including NIV and invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), society relies on family caregivers to provide skilled, vigilant, sometimes around the clock care with families “daily living with distress and enrichment” (Keilty and Daniels, 2018; Carnevale et al., 2006). A meta-synthesis of 12 studies described the experience of life with a child dependent on a ventilator at home (Lindahl and Lindblad, 2011). For the children, this included the risk of being excluded from society and everyday relationships, living with a machine, and thoughts about health and being alive. Parents identified an awareness of reality and the values of life while also recognizing a demanding parenthood that included a lot of learning. In a study of people with neuromuscular disease using NIV, participants identified that NIV had extended their life though their life was different from before NIV with some restoration of some aspects they had lost (Perry et al., 2022). As the sum of the benefits and challenges of LT-NIV use may not always balance, understanding where this balance sits for an individual child and their family is important to consider (Alebraheem et al., 2018). Parents in the current study could see a better life for themselves and their children if only LT-NIV use could be optimized. Documenting the desired benefits as well as a realistic assessment of challenges prior to starting LT-NIV may help to set expectations for the child, family, and healthcare practitioners.

Even in this younger pre-teen age group, feeling different because of LT-NIV was an obstacle. While this included fear and frustration related to NIV use, it also included concerns regarding social relationships and physical appearance. Seeking to be “normal” was a theme in a study of families with a child using HMV where themes did not differ between families whose children used NIV or IMV (Carnevale et al., 2006). In this same study, families identified being offended by the reaction of others to their child using HMV leaving families feeling like strangers in their own communities. Social pressure may help and hinder adherence. In a study of adolescents, those with high CPAP use reported wanting to alleviate worry for their caregivers while those with low or no use reported wanting to be like their peers, with caregivers noting the adolescent's desire to conform to peer norms (Prashad et al., 2013). Friendships are important to children using HMV and wanting to be like their peers is appropriate; keeping their HMV use hidden from others is a way to ensure children using HMV are seen as similar to their peers (Carnevale et al., 2006; Earle et al., 2006). Both the current study results and others highlight feelings of shame, embarrassment, and not being cool related to peers finding out about their HMV use (Prashad et al., 2013; Ennis et al., 2015; Earle et al., 2006). The present study also adds concerns about physical appearance impacted by LT-NIV use, including changes to facial shape, facial marking, and hair loss raised by both children and their parents. While concerns about feeling different may increase in adolescence, addressing these concerns and being vigilant about recognizing physical changes related to LT-NIV use may help to address important barriers to LT-NIV.

Anyone working with LT-NIV users will identify NIV interface or mask concerns as a barrier to consistent LT-NIV use; what may be surprising is that the interface is one of many equipment issues. A well-fitting mask, lower air leak, and getting the right mask early on in LT-NIV initiation are all factors associated with higher adherence (Bhattacharjee et al., 2020; MacDonagh et al., 2021; Bachour et al., 2016) whereas an uncomfortable mask is a common barrier to adherence (Pascoe et al., 2019). Masks for children are often smaller versions of adult masks despite age being an important determinants of facial proportions (Farnell et al., 2021). A recent American Thoracic Society Workshop Report focused on promoting individualize mask selection to improve comfort, adherence and efficacy of CPAP (Genta et al., 2020). Studies of different flow-generators, or device modes (e.g., CPAP vs. AutoPAP), and what have been deemed comfort settings (e.g., humidification, heated tubing, ramp, and expiratory pressure relief) have failed to show benefit for adherence in adults (Killick and Marshall, 2021; Johnson, 2022; Zhuang et al., 2010) although they may improve comfort and adherence for individual children and adults. The current study adds headgear and tubing concerns to the list of potential LT-NIV equipment issues that may affect usage. Suggestions for equipment improvements came from both children and parents, focusing on making the equipment child-friendly and addressing technical issues. With customized masks not yet a practical option (Wu et al., 2018; Duong et al., 2021; Green, 2020), integrating LT-NIV users, including children and their caregivers, into the development and design process of NIV equipment may be the best option for improving user experience with this technology.

The limitations of the study may impact interpretation and translation of the findings. Children and parents who responded to the study invitation may not be representative of all children using LT-NIV and their parents. Children who were unsuccessful at initiating LT-NIV were excluded and those who chose to participate skew toward those with high adherence and good mask fit. Despite this, the results highlight that LT-NIV use presents considerable challenges, even for families who are successful in using this technology. Although small sample size is inherent in most qualitative methods, participants selected purposefully for their contributions in a specific setting are generalizable to any setting in which the problem or situation is a shared experience, such as LT-NIV (Morse, 2016). The experience of the research team members with LT-NIV may have led to bias in the focus group guide and construction of themes. The guide, however, focused on adherence and the interface, neither of which came out as major themes.

The voices of children and their parents provide a meaningful and necessary perspective on the experience of using LT-NIV. Their accounts detail how LT-NIV has improved their lives by helping children breathe during sleep while highlighting struggles encountered by children and parents including the significant time and commitment invested to ensure successful LT-NIV use. The development of anticipatory guidance and targeted programming for children initiating LT-NIV needs to be informed by the experience of children using LT-NIV. This means including children using LT-NIV and their caregivers in designing the solutions to the challenges of using this technology rather than asking them to test possible solutions after they have been developed. Investing in pediatric-specific equipment needs to be prioritized and children using LT-NIV and their caregivers are the most important stakeholders to be included in the development of guidance to inform policy development for funding and healthcare groups. Ultimately, alliances between health care teams, children and their families will be critical to improve the successful use and health outcomes for children using LT-NIV and their families.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by University of Alberta Health Research Ethics Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin.

DO: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JK: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. JM: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Women and Children's Research Institute (WCHRI).

We are grateful to the children and parents who participated in this study.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsle.2024.1459349/full#supplementary-material

Adeleye, A., Ho, A., Nettel-Aguirre, A., Buchhalter, J., and Kirk, V. (2016). Noninvasive positive airway pressure treatment in children less than 12 months of age. Can. Respir. J. 2016:7654631. doi: 10.1155/2016/7654631

AlBalawi, M. M., Castro-Codesal, M., Featherstone, R., Sebastianski, M., Vandermeer, B., Alkhaledi, B., et al. (2022). Outcomes of long-term noninvasive ventilation use in children with neuromuscular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 19, 109–119. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202009-1089OC

Alebraheem, Z., Toulany, A., Baker, A., Christian, J., and Narang, I. (2018). Facilitators and barriers to positive airway pressure adherence for adolescents. A qualitative study. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 15, 83–88. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201706-472OC

Bachour, A., Vitikainen, P., and Maasilta, P. (2016). Rates of initial acceptance of PAP masks and outcomes of mask switching. Sleep Breath 20, 733–738. doi: 10.1007/s11325-015-1292-x

Bedi, P. K., Castro-Codesal, M., DeHaan, K., and MacLean, J. E. (2018b). Use and outcomes of long-term noninvasive ventilation for infants. Can. J. Respirat. Crit. Care Sleep Med. 2, 205–212. doi: 10.1080/24745332.2018.1465369

Bedi, P. K., Castro-Codesal, M. L., Featherstone, R., AlBalawi, M. M., Alkhaledi, B., Kozyrskyj, A. L., et al. (2018a). Long-term non-invasive ventilation in infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Pediatr. 6:13. doi: 10.3389/fped.2018.00013

Bhattacharjee, R., Benjafield, A. V., Armitstead, J., Cistulli, P. A., Nunez, C. M., Pepin, J. D., et al. (2020). Adherence in children using positive airway pressure therapy: a big-data analysis. Lancet Digit. Health 2, e94–e101. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(19)30214-6

Carnevale, F. A., Alexander, E., Davis, M., Rennick, J., and Troini, R. (2006). Daily living with distress and enrichment: the moral experience of families with ventilator-assisted children at home. Pediatrics 117, e48–60. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0789

Castro-Codesal, M. L., Dehaan, K., Bedi, P. K., Bendiak, G. N., Schmalz, L., Katz, S. L., et al. (2018b). Longitudinal changes in clinical characteristics and outcomes for children using long-term non-invasive ventilation. PLoS ONE 13:e0192111. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192111

Castro-Codesal, M. L., Dehaan, K., Bedi, P. K., Bendiak, G. N., Schmalz, L., Rosychuk, R. J., et al. (2020). Long-term benefits in sleep, breathing and growth and changes in adherence and complications in children using non-invasive ventilation. Can. J. Respirat. Crit. Care Sleep Med. 4, 115–123. doi: 10.1080/24745332.2020.1722975

Castro-Codesal, M. L., Dehaan, K., Featherstone, R., Bedi, P. K., Martinez Carrasco, C., Katz, S. L., et al. (2018a). Long-term non-invasive ventilation therapies in children: a scoping review. Sleep Med. Rev. 37, 148–158. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2017.02.005

Duong, K., Glover, J., Perry, A. C., Olmstead, D., Ungrin, M., Colarusso, P., et al. (2021). Feasibility of three-dimensional facial imaging and printing for producing customised nasal masks for continuous positive airway pressure. ERJ Open Res. 7, 00632–02020. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00632-2020

Earle, R. J., Rennick, J. E., Carnevale, F. A., and Davis, G. M. (2006). “It's okay, it helps me to breathe”: the experience of home ventilation from a child's perspective. J. Child Health Care 10, 270–282. doi: 10.1177/1367493506067868

Ennis, J., Rohde, K., Chaput, J. P., Buchholz, A., and Katz, S. L. (2015). Facilitators and barriers to noninvasive ventilation adherence in youth with nocturnal hypoventilation secondary to obesity or neuromuscular disease. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 11, 1409–1416. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.5276

Farnell, D. J. J., Richmond, S., Galloway, J., Zhurov, A. I., Pirttiniemi, P., Heikkinen, T., et al. (2021). An exploration of adolescent facial shape changes with age via multilevel partial least squares regression. Comput. Methods Progr. Biomed. 200:105935. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2021.105935

Fauroux, B., Abel, F., Amaddeo, A., Bignamini, E., Chan, E., Corel, L., et al. (2022). ERS statement on paediatric long-term non-invasive respiratory support. Eur. Respir. J. 59:2021. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01404-2021

Genta, P. R., Kaminska, M., Edwards, B. A., Ebben, M. R., Krieger, A. C., Tamisier, R., et al. (2020). The importance of mask selection on continuous positive airway pressure outcomes for obstructive sleep apnea. An Official American Thoracic Society workshop report. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 17, 1177–1185. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202007-864ST

Green, G. (2020). 3D-Printed CPAP Masks for Children With Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT02261857 (accessed August 24, 2022).

Hudson, S., Abusido, T., Sebastianski, M., Castro-Codesal, M. L., Lewis, M., MacLean, J. E., et al. (2022). Long-term non-invasive ventilation in children with down syndrome: a systematic review. Front. Pediatr. 10:886727. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.886727

Hurvitz, M., Sunkonkit, K., Defante, A., Lesser, D., Skalsky, A., Orr, J., et al. (2023). Non-invasive ventilation usage and adherence in children and adults with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a multicenter analysis. Muscle Nerve 68, 48–56. doi: 10.1002/mus.27848

Johnson, K. G. (2022). APAP, BPAP, CPAP, and new modes of positive airway pressure therapy. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1384, 297–330. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-06413-5_18

Katz, S. L., Kirk, V. G., MacLean, J. E., Bendiak, G. N., Harrison, M. A., Barrowman, N., et al. (2020). Factors related to positive airway pressure therapy adherence in children with obesity and sleep-disordered breathing. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 16, 733–741. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.8336

Keilty, K., and Daniels, C. (2018). Section 13: the published experience and outcomes of family caregivers when a child is on home mechanical ventilation. Can. J. Respirat. Crit. Care Sleep Med. 2, 88–93. doi: 10.1080/24745332.2018.1494994

Kennedy, C., Kools, S., and Krueger, R. (2001). Methodological considerations in children's focus groups. Nurs. Res. 50, 184–187. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200105000-00010

Killick, R., and Marshall, N. S. (2021). The impact of device modifications and pressure delivery on adherence. Sleep Med. Clin. 16, 75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2020.10.008

Lindahl, B., and Lindblad, B. M. (2011). Family members' experiences of everyday life when a child is dependent on a ventilator: a metasynthesis study. J. Fam. Nurs. 17, 241–269. doi: 10.1177/1074840711405392

MacDonagh, L., Farrell, L., O'Reilly, R., McNally, P., Javadpour, S., Cox, D. W., et al. (2021). Efficacy and adherence of noninvasive ventilation treatment in children with Down syndrome. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 56, 1704–1715. doi: 10.1002/ppul.25308

Machaalani, R., Evans, C. A., and Waters, K. A. (2016). Objective adherence to positive airway pressure therapy in an Australian paediatric cohort. Sleep Breath 20, 1327–1336. doi: 10.1007/s11325-016-1400-6

Morse, J. M. (2016). Qualitative generalizability. Qual. Health Res. 9, 5–6. doi: 10.1177/104973299129121622

O'Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., and Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 89:388. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388

Pascoe, J. E., Sawnani, H., Hater, B., Sketch, M., and Modi, A. C. (2019). Understanding adherence to noninvasive ventilation in youth with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 54, 2035–2043. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24484

Patil, S. P., Ayappa, I. A., Caples, S. M., Kimoff, R. J., Patel, S. R., Harrod, C. G., et al. (2019). Treatment of adult obstructive sleep apnea with positive airway pressure: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and GRADE assessment. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 15, 301–334. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.7638

Pavone, M., Verrillo, E., Onofri, A., Caggiano, S., Chiarini Testa, M. B., Cutrera, R., et al. (2020). Characteristics and outcomes in children on long-term mechanical ventilation: the experience of a pediatric tertiary center in Rome. Ital. J. Pediatr. 46:12. doi: 10.1186/s13052-020-0778-8

Perriol, M. P., Jullian-Desayes, I., Joyeux-Faure, M., Bailly, S., Andrieux, A., Ellaffi, M., et al. (2019). Long-term adherence to ambulatory initiated continuous positive airway pressure in non-syndromic OSA children. Sleep Breath 23, 575–578. doi: 10.1007/s11325-018-01775-2

Perry, M. A., Jenkins, M., Jones, B., Bowick, J., Shaw, H., Robinson, E., et al. (2022). “Me and 'that' machine”: the lived experiences of people with neuromuscular disorders using non-invasive ventilation. Disabil. Rehabil. 45, 1847–1856. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2022.2076939

Prashad, P. S., Marcus, C. L., Maggs, J., Stettler, N., Cornaglia, M. A., Costa, P., et al. (2013). Investigating reasons for CPAP adherence in adolescents: a qualitative approach. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 9, 1303–1313. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.3276

Tan, L. T., Nathan, A. M., Jayanath, S., Eg, K. P., Thavagnanam, S., Lum, L. C. S., et al. (2020). Health-related quality of life and developmental outcome of children on home mechanical ventilation in a developing country: a cross-sectional study. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 55, 3477–3486. doi: 10.1002/ppul.25083

Ward, D. J., Furber, C., Tierney, S., and Swallow, V. (2013). Using framework analysis in nursing research: a worked example. J. Adv. Nurs. 69, 2423–2431. doi: 10.1111/jan.12127

Windisch, W., Geiseler, J., Simon, K., Walterspacher, S., and Dreher, M. (2018). German national guideline for treating chronic respiratory failure with invasive and non-invasive ventilation - revised edition 2017: part 2. Respiration 96, 171–203. doi: 10.1159/000488667

Wu, Y. Y., Acharya, D., Xu, C., Cheng, B., Rana, S., Shimada, K., et al. (2018). Custom-fit three-dimensional-printed bipap mask to improve compliance in patients requiring long-term noninvasive ventilatory support. J. Med. Device 12, e0310031–e0310038. doi: 10.1115/1.4040187

Keywords: adherence, focus group, framework analysis, pre-teens, NIV equipment

Citation: Olmstead D, Carroll A, Klein J and MacLean JE (2024) The experience of children using long-term non-invasive ventilation: a qualitative study. Front. Sleep 3:1459349. doi: 10.3389/frsle.2024.1459349

Received: 04 July 2024; Accepted: 07 November 2024;

Published: 28 November 2024.

Edited by:

David Ingram, Children's Mercy Kansas City, United StatesReviewed by:

Hasnaa Jalou, Riley Hospital for Children, United StatesCopyright © 2024 Olmstead, Carroll, Klein and MacLean. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Joanna E. MacLean, am9hbm5hLm1hY2xlYW5AdWFsYmVydGEuY2E=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.