- 1Doctoral Program of Public Health, Faculty of Public Health, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia

- 2Faculty of Public Health, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia

- 3Department of Environmental and Occupational Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia, UPM Serdang, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia

- 4Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Jember, Jember, Indonesia

Introduction: Sexual and reproductive health (SRH) among adolescents is a critical aspect of global health. Rural adolescents often encounter significant barriers to reproductive health awareness, elevating their risks for unintended pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and other reproductive health issues. This systematic review seeks to identify and analyze the barriers hindering reproductive health awareness among rural adolescents.

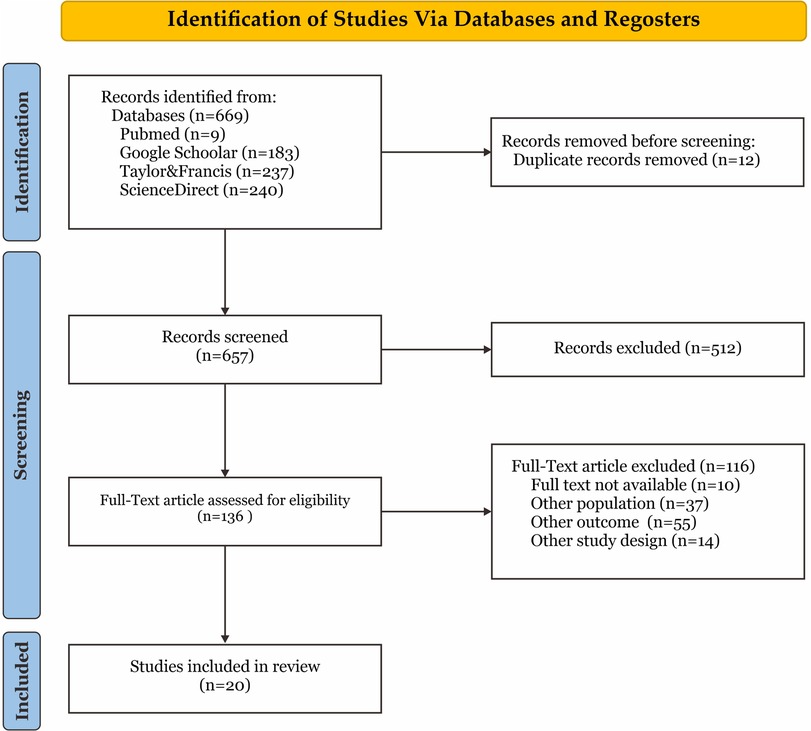

Methods: This review followed PRISMA guidelines. Literature searches were conducted in PubMed, ScienceDirect, Google Scholar, and Taylor & Francis, focusing on studies published from 2019 to 2024. Keywords included “Adolescent,” “Rural,” “Reproductive Health,” “Awareness,” and “Barriers.” Studies were screened based on eligibility criteria, and data were extracted and analyzed to identify key barriers at the individual, interpersonal, social/community, and health services levels.

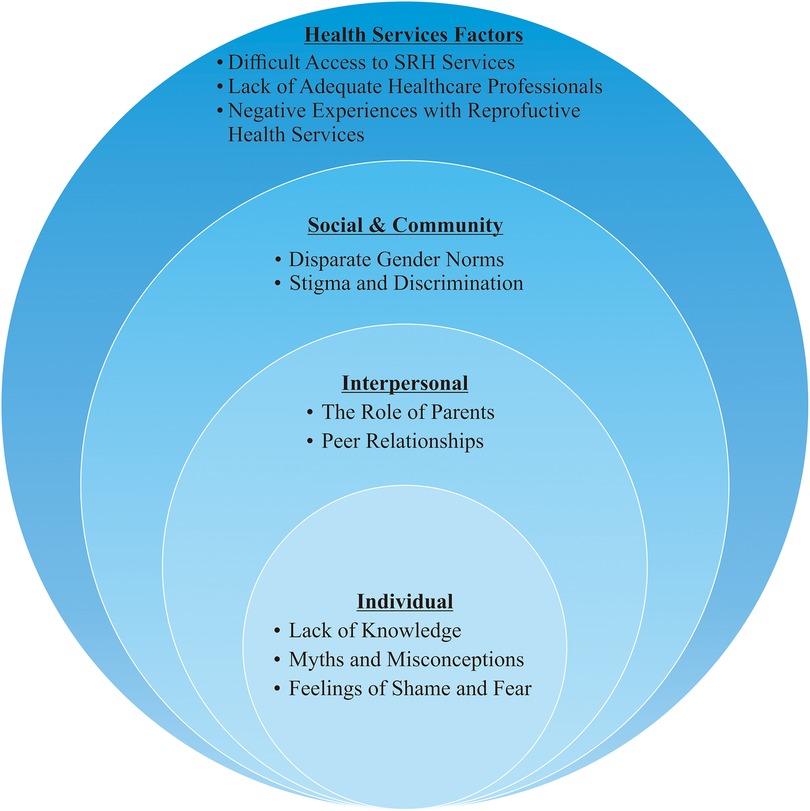

Results: Out of 669 records, 20 studies met the inclusion criteria. Identified barriers at the individual level included lack of knowledge, myths, misconceptions, and feelings of shame and fear. Interpersonal barriers were related to poor communication between parents and adolescents and misinformation from peers. Social and community barriers encompassed rigid social norms, stigma, and discrimination. Health services barriers included limited access and negative experiences with reproductive health services.

Discussion: Rural adolescents face complex barriers to reproductive health awareness driven by factors at the individual, interpersonal, social, and health services levels. Comprehensive interventions, such as educational campaigns, training for healthcare providers, and improved access via mobile or online platforms, are essential to enhance reproductive health awareness and outcomes.

Systematic Review Registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/, PROSPERO (CRD42024554439).

1 Introduction

Adolescent reproductive health was included in the global health and development agenda at the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) in 1994. Reproductive health is defined as a state of physical, mental, emotional, and social well-being related to the reproductive system (1). Adolescence is a period characterised by the drive to explore sexual activities, yet the lack of knowledge about reproductive health often increases the risk of various reproductive health issues, including unintended pregnancies, abortions, and sexually transmitted infections such as HIV/AIDS (2). Awareness of adolescent reproductive health still shows significant disparities between rural and urban areas (3).

Reproductive health issues among adolescents are significant worldwide. In 2022, the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) estimated that 1.65 million adolescents were living with HIV/AIDS. Approximately 1.1 million or 85 percent were in developing countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, with the remainder in Asia and the Americas (4). Additionally, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that in 2019 there were 12 million cases of unintended adolescent pregnancies in developing countries (5). The prevalence of sexually transmitted infections significantly increased from 1994–2017 (6). Other studies indicate that disparities in rural areas lead to limited access to information and reproductive health services, contributing to higher health risks among rural adolescents (7–10). The lack of healthcare facilities, increasing service costs, and access difficulties faced by rural communities are major barriers to improving understanding and access to reproductive health services (11). Furthermore, the understanding of social norms in rural areas can influence adolescents' behaviour in making decisions about their reproductive health (12). Highlighting these issues, many barriers still prevent rural adolescents from obtaining information and improving their knowledge related to reproductive health, thereby hindering the development of reproductive health awareness (13).

Although some published systematic reviews provide insights into the factors affecting access to adolescent reproductive health services, such as structural barriers (negative attitudes of healthcare providers, lack of skills, stigma, cost, lack of access to services, privacy concerns) and individual barriers (lack of knowledge), none specifically address the barriers faced by rural adolescents in becoming aware of the importance of reproductive health (14, 15). Therefore, this systematic review aims to better illustrate the obstacles experienced by adolescents in rural areas.

The preparation of this systematic review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (16). The PRISMA 2020 guidelines outline several stages in the process, including: defining eligibility criteria, identifying sources of information, selecting data, collecting data, and extracting data. The data obtained will be illustrated using a flow diagram in accordance with the guidelines (17). The use of the PRISMA method will make this systematic review more transparent, comprehensive, and accurate (16).

By identifying and understanding the inhibiting factors affecting reproductive health awareness among rural adolescents, it is hoped that this review can inform the development of more effective and relevant interventions. Therefore, the aim of this study is to elucidate the specific factors that hinder reproductive health awareness among rural adolescents, with the ultimate goal of improving their well-being and reproductive health.

2 Methods

The systematic review followed the standards of the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses” (PRISMA). PRISMA criteria were used to identify and screen scientific papers, as illustrated in Figure 1 of the PRISMA flowchart (18).

2.1 Identification and selection of studies

The literature search was conducted on 11 May 2024 across four databases: PubMed, ScienceDirect, Google Scholar, and Taylor & Francis. Keywords used included “Adolescent”, “Rural”, “Reproductive Health”, “Awareness”, and “Barriers” employing Boolean operators (AND/OR). The publication range covered the past five years. The search strategy was tailored to each database, as detailed in Supplementary Table S1. A secondary search was performed by manually reviewing the reference lists of the articles included in this review to identify potentially relevant studies.

The eligibility criteria were articulated according to the Population, Exposure, Outcomes, and Study (PEOS) framework for the research question. Specifically, “P” pertained to adolescents residing in rural areas; “E” encompassed barriers to reproductive health awareness; “O” focused on awareness levels regarding reproductive health; and “S” denoted studies with both qualitative and quantitative designs, published within the past five years in peer-reviewed journals in English.

The results of the database searches were imported into Mendeley software, where duplicate studies were identified and subsequently excluded. Titles and abstracts of the studies were independently evaluated based on the eligibility criteria. Following this stage, the studies available online were assessed to ascertain their inclusion status.

2.2 Data extraction

Following the PRISMA standards for screening and selection, we retrieved the essential data, including title, author, year, journal, country, study design, population, research aims, and outcome were all used as descriptive information.

2.3 Assessment of study quality

In this systematic review, the quality assessment of included articles utilized the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Quantitative Studies and the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research (19). The former evaluated aspects such as sampling strategy and statistical analysis, while the latter assessed research design and data analysis methods (20). Each checklist facilitated a thorough evaluation of methodological quality and risk of bias, informing the interpretation of study findings (19).

2.4 Ethical considerations

This systematic review did not require ethical approval. The authors of the articles reviewed in this systematic review had obtained consent from their research subjects. However, this review was registered under PROSPERO (CRD42024554439).

3 Results

A total of 669 records were retrieved from the literature search across four databases. Following the removal of 12 duplicates, 521 records were excluded based on title and abstract screening, resulting in 136 studies for full-text assessment. Subsequently, 123 studies deemed irrelevant were excluded, leaving 20 studies eligible for inclusion in the review (Figure 1). These studies were published between 2019 and 2024, predominantly emerging after 2022, and were conducted in 10 countries, with a focus on the African Continent. A summary of the included studies is shown in Supplementary Table S2.

The findings of the review identified various barriers to reproductive health awareness among rural adolescents from multiple perspectives, including those of adolescents themselves, parents/caregivers, and healthcare providers. The majority of studies (76.9%) explored barriers from the perspective of adolescents (21–33), while a smaller proportion investigated the viewpoints of parents/caregivers (15.3%) (34, 35), and healthcare providers (7.6%) (36).

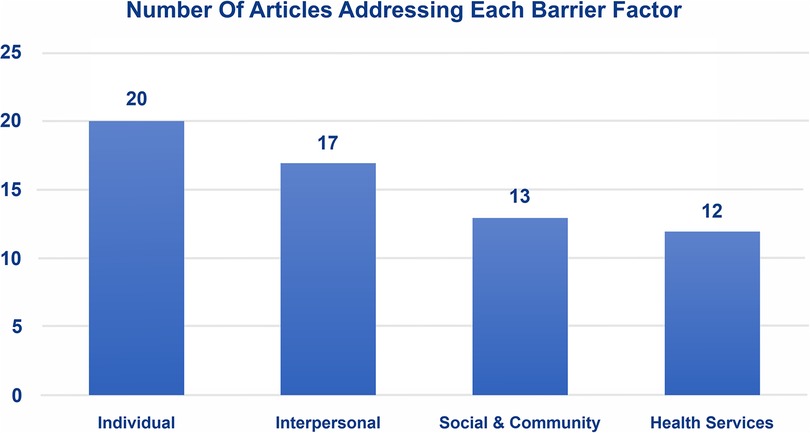

In this review, we identify factors based on the individual level, interpersonal level, social and community level, and health services level (Figure 3). Our findings reveal that 20 studies highlight individual factors (100%), 18 studies highlight interpersonal factors (90%), 13 studies focus on social and community factors (65%), and 12 studies highlight health services factors (60%) (Figure 2).

3.1 Individual factor

Individual factors constitute the most significant barriers to SRH awareness among rural adolescents. These factors include a lack of knowledge, myths and misconceptions, and feelings of shame and fear (21–30, 32–35, 37–42).

3.1.1 Lack of knowledge

Ten studies highlight the low levels of SRH knowledge among rural adolescents (21, 22, 26–29, 34, 36, 38). Knowledge about puberty, menstruation, contraceptives, sexually transmitted infections, and reproductive health in general is typically low among rural populations (24, 39, 42). Many adolescents do not understand the basic biological aspects and the importance of maintaining reproductive health. Rural adolescents sometimes receive incorrect information or hold misconceptions about reproductive health due to prevailing social norms in rural areas (28, 34, 37). Additionally, many rural adolescents are unaware of the existence of reproductive health services in their regions, resulting in a lack of understanding of the benefits of utilising these services (21, 22).

3.1.2 Myths and misconceptions

Six studies mention the emergence of myths and misconceptions among rural adolescents (23, 30, 32, 33, 40, 42). Among rural adolescents, there are various incorrect assumptions about pregnancy, contraception, sexually transmitted infections, menstruation, and reproductive health due to the influence of social and cultural norms. Rural adolescents often believe that first-time sexual intercourse does not cause pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections are only transmitted by sex workers or shared needles, contraception is unnecessary for occasional sexual activity, and discussing sexual issues or seeking sexual health information is considered immoral (23, 30, 32, 33, 40, 42).

3.1.3 Feelings of shame and fear

Feelings of shame and fear are one of the inhibiting factors in reproductive health awareness among rural adolescents. There are seven studies that discuss the issue of feelings of shame and fear as an obstacle in the reproductive health awareness of rural adolescents (24, 28, 34, 35, 37–39). Shame and fear are the result of social and cultural norms that exist in rural communities related to reproductive issues that are still considered taboo or inappropriate to talk about (28, 34, 37, 39). This assumption is also reinforced by the existence of stigma and social punishment when adolescents try to find information related to SRH or when visiting reproductive health services (35). As a result, adolescents become reluctant to seek information and choose to follow existing norms so that awareness related to reproductive health is hampered. This barrier is exacerbated by the lack of family support which further inhibits open communication about reproductive health (34, 38, 39).

3.2 Interpersonal factor

In this review, interpersonal factors are also significantly discussed in the literature reviewed. The interpersonal factors focus on two aspects: the role of parents and peer relationships.

3.2.1 The role of parents

The role of parents is a significant barrier to improving reproductive health awareness among rural adolescents for several reasons. In this review, ten studies discuss the role of parents as a barrier to SRH awareness among rural adolescents (21, 22, 26, 28, 29, 34, 35, 39, 40, 42). The lack of communication between parents and children regarding reproductive health topics is often due to social and cultural norms that consider discussions about sexuality to be taboo or inappropriate (28, 39, 40, 42). Parents often feel uncomfortable or lack sufficient knowledge to discuss these topics, resulting in adolescents not receiving the necessary information from reliable sources (21, 26, 29, 35). Additionally, parents' negative attitudes towards sexual education, believing that discussing reproductive health may encourage undesirable sexual behaviour, further exacerbate the situation (39). These barriers create an environment where adolescents are undereducated about reproductive health and do not know how to protect themselves effectively.

3.2.2 Peer relationships

Peer relationships play an important role in shaping adolescent awareness of reproductive health. Peers can be an obstacle or a driver for the creation of awareness related to reproductive health of rural adolescents. This can occur because peer groups consist of individuals of the same age group, so adolescents often find it easier to exchange ideas or information without any restrictions related to reproductive issues (28, 43). On the other hand, adolescents sometimes listen to their peers more than their parents so that parents will have difficulty in providing understanding related to reproductive health. Peer relationships sometimes put pressure to follow the behaviour of their friends in order to be considered the same (34). In some findings, peer relationships that tend to be negative sometimes have risky behaviours and misinformation related to reproductive health (25, 26). As a result, adolescents' awareness of reproductive health is hampered. Conversely, positive peer relationships can increase knowledge and awareness of reproductive health in rural adolescents (25, 33).

3.3 Social and community factors

Social and community factors play a highly significant role as barriers to reproductive health awareness among rural adolescents. Social and community factors include social and cultural norms, stigma and discrimination.

3.3.1 Disparate gender norms

Disparate gender norms are still often found in rural areas. Disparate gender norms create a view of men as breadwinners and women taking care of the household (30, 34, 42). As a result, girls' roles are limited and intended to keep them at home so that their parents can supervise them and prepare them to be good wives. This is very different from teenage boys who have more freedom (34). One of the phenomena that occurs due to this perspective is the limited opportunity for adolescent girls to get formal education. In rural areas, education related to reproductive health is often provided at school (38). Other findings related to disparate gender norms show that adolescent girls when married can experience a sense of isolation due to living with their spouse. This change in lifestyle greatly affects adolescent girls' decision-making to seek information or services related to reproductive health (30). The perspective of disparate gender norms that exist in rural areas can be an obstacle for adolescents to have reproductive health awareness, especially adolescent girls.

3.3.2 Stigma and discrimination

Seven studies discuss stigma and discrimination as barriers to adolescents' SRH awareness (25, 29, 32, 35, 40–42). Social stigma that considers discussions about reproductive health to be taboo makes adolescents feel ashamed and afraid to seek information or access reproductive health services, fearing they will be judged or labelled as “naughty” (32, 42). Discrimination from healthcare providers and community members, particularly against adolescent girls and adolescents with disabilities, worsens the situation by preventing them from obtaining the necessary services (29, 35, 40). This discrimination leads to adolescents feeling unsupported and reluctant to seek help, resulting in a lack of knowledge and awareness about reproductive health. Efforts to address these barriers should focus on reducing stigma and discrimination and improving access to adolescent-friendly reproductive health services (25, 41).

3.4 Health services factors

3.4.1 Difficult access to SRH services

Difficult access to reproductive health services is due to the lack of adequate healthcare facilities and the long distances to healthcare centres (21, 23, 29, 39–41). In a study conducted in Oyo State, Nigeria, adolescents found it challenging to access quality services (21). In Rwanda and Ethiopia, a lack of healthcare facilities and adequate healthcare professionals led to low utilisation of services (29, 39, 40, 43). Strict lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic and fear of COVID-19 transmission have also hindered rural adolescents' access to reproductive health services (41). In addition, health workers are more focused on pandemic response, so reproductive health services are disrupted. These barriers can interfere with the delivery of appropriate information related to reproductive health from health workers to rural adolescents, so that reproductive health awareness becomes minimal (24).

3.4.2 Lack of adequate healthcare professionals

Several literature reviews highlight the shortage of trained healthcare professionals and support for them in providing reproductive health services, resulting in adolescents not receiving the education and services they need (34, 36, 40, 41, 43). Studies in Zambia and Ethiopia found that healthcare providers and community workers did not have adequate training to support reproductive health services (37, 40). Another study during the COVID-19 pandemic in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, noted that the lack of healthcare professionals worsened the situation regarding access to reproductive health services (41).

3.4.3 Negative experiences with reproductive health services

Negative experiences with reproductive health services discourage adolescents from seeking help and reduce their awareness and utilisation of these services (22, 24, 25, 35). In a study conducted in Oyo State, Nigeria, adolescents reported unfriendly services (22). Another study in Bangladesh found that adolescents with disabilities faced discrimination (35). In West Bengal, it was found that services were not tailored to adolescents' needs, and negative experiences with healthcare providers deterred adolescents from seeking help (24, 25).

4 Discussion

Our findings indicate that the biggest barriers for adolescents are individual factors. The most dominant individual factor is the lack of knowledge related to sexual and reproductive health among rural adolescents. As they grow and develop, adolescents are likely to face pressures to explore sexual activities. However, the lack of knowledge about reproductive health increases the risk of various reproductive health issues, including unintended pregnancies, abortions, and sexually transmitted infections such as HIV/AIDS (2). Gender disparities are evident in high-risk sexual behaviours. Multiple sexual partners, inconsistent use of contraception, and premarital sex are more prevalent among male adolescents than females (44). Female adolescents often become victims of abuse, unintended pregnancies, and cultural stigma, which further threaten their reproductive health (45). Despite widespread knowledge about HIV/AIDS among adolescents, broader aspects of reproductive health remain poorly understood. Adolescents lack knowledge about menstruation, puberty processes, contraception, other sexually transmitted infections, pregnancy, abortion, how to care for reproductive organs, and how to access reproductive health services (46, 47). Generally, adolescents receive reproductive health information at school. This topic is usually included in the school curriculum but is often not taught because teachers feel uncomfortable discussing it (48). However, adolescents who drop out of school do not have access to this information, making them a more vulnerable and less supervised group (49).

Embedded gender norm disparities among adolescents can influence their health behaviours (50, 51). Disparities such as the experience of menstruation in female adolescents have impacts on behaviour, self-confidence, and decision-making, leading to feelings of shame and discomfort (52). These limitations in knowledge and feelings affect SRH awareness among rural adolescents.

This study also found that interpersonal factors, such as the role of parents and peers, play a significant role in adolescents' awareness of SRH. Most rural adolescents still rely on their families, with decision-making often handled by parents (28). Additionally, parental decision-making is influenced by social norms that view adolescents, particularly girls, as lacking control and having their opinions undervalued (53). Poor communication between adolescents and parents regarding reproductive health issues results in adolescents being less capable of making informed decisions (54). Even though parents are preferred sources of information about reproductive health and are aware of their role in adolescent reproductive health, a lack of confidence and prevailing religious norms create an uncomfortable communication environment between parents and adolescents. Alternatives for adolescents to obtain information include teachers, peers, and siblings (55, 56). Peer-based education can be an effective intervention in improving reproductive health knowledge and behaviour among adolescents. Peer-based education is a structured intervention where adolescents are trained to disseminate accurate reproductive health information to their peers, as opposed to negative influence or peer pressure. These interventions consistently show improvements in SRH knowledge, such as knowledge about HIV, contraceptive use, and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (57). The effectiveness of peer education depends on several conditions, including structural support, comprehensive educational materials, and supervision by trained health professionals (58).

Another barrier is the community and social factors, which significantly affect SRH awareness among rural adolescents. Disparate gender norms, still frequently encountered in rural areas, and the perception of SRH as a taboo by various groups are influenced by the religious and cultural perspectives of different ethnicities (59). In some belief systems, matters related to sexuality are considered private and unnecessary to discuss, with the belief that discussing them may lead to negative outcomes (60). Unmarried adolescents or women who visit SRH services face stigmatisation due to the perception that anyone seeking SRH services must be sexually active (61). This perception stems from social norms that view sexually active adolescents or unmarried individuals as immoral (62). Various interventions are necessary to address issues within the community and social domains. Community-based approaches involving religious leaders, teachers, parents, and community leaders are crucial in overcoming these social barriers (63). In some communities, sexual and reproductive health education programs in schools are very effective without having to override local cultural values (64). This will not only reduce stigma but also increase public acceptance of SRH services.

Another important factor to consider is health services. This study highlights that health services can also be a barrier. Most rural adolescents receive SRH education at school. Although SRH topics are comprehensively covered in schools, some adolescents who drop out do not receive this information (10). In several countries, rural communities often face disparities in accessing healthcare services. Rural adolescents still experience difficulties in accessing reproductive health services, inadequate healthcare, and increasing costs, especially in remote areas (65, 66). Although reproductive health is a right for everyone, racial-ethnic disparities in accessing adequate reproductive healthcare still exist in multiracial-ethnic countries (67, 68). Additionally, discrimination against individuals with disabilities is still found in healthcare facilities, in terms of physical accessibility, attitudes, and communication barriers (69).

The importance of SRH knowledge is significantly influenced by personal, community, cultural, religious, policy, and regulatory factors. These factors overlap and interact with each other, resulting in impeded awareness of the importance of implementing SRH (61). Evidence-based interventions are crucial to address these overlapping factors (70). Awareness campaigns on reproductive health for parents and adolescents, mobile/online-based outreach, peer educator training, and school-based education can be implemented to enhance reproductive health awareness (71, 72).

Although this study has employed a comprehensive approach and adhered to PRISMA guidelines throughout the review process, we acknowledge that it still has limitations. The literature search was restricted to publications written in English, which may have overlooked relevant studies written in other languages on the subject. The review predominantly includes studies from the African continent, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other regions. Additionally, the literature search was confined to studies published between 2019 and 2024, potentially excluding older relevant studies that could provide further insights. Another limitation of this study is the variation in study design, population, and context included, which results in data heterogeneity and may limit the uniformity of conclusions.

5 Conclusion

This systematic review reveals that the primary barriers to reproductive health awareness among rural adolescents include a lack of knowledge, myths and misconceptions, and feelings of shame and fear driven by social and cultural norms. Interpersonal barriers such as poor communication between parents and adolescents, and misinformation from peers exacerbate these issues. Furthermore, rigid social norms, stigma, discrimination, and limited access to reproductive health services further prevent adolescents from obtaining necessary information and services. Comprehensive interventions, including educational campaigns, training for service providers, and improved accessibility through mobile or online platforms, are essential to enhance reproductive health awareness and outcomes among rural adolescents.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

Swa: Conceptualization, Investigation, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SWi: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SP: Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. MA: Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by the Higher Education Funding Center (Balai Pembiayaan Pendidikan Tinggi, BPPT) and the Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education (Lembaga Pengelola Dana Pendidikan, LPDP), under the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research and Technology of the Republic of Indonesia. Recipient: Sri Wahyuningsih, Indonesian Education Scholarship Identification Number: 202327091301.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all those who provided us the possibility to complete this systematic review.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frph.2024.1444111/full#supplementary-material

References

1. World Health Organization. Sexual health and its linkages to reproductive health: an operational approach. Geneva: World Health Organization (2017). Available online at: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/258738 (accessed May 14, 2024).

2. WHO. Adolescent and young adult health (2023). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescents-health-risks-and-solutions (accessed May 10, 2024).

3. Melesse DY, Mutua MK, Choudhury A, Wado YD, Faye CM, Neal S, et al. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health in sub-Saharan Africa: who is left behind? BMJ Glob Heal. (2020) 5:1–8. doi: 10.1017/gheg.2020.1

4. UNICEF. Adolescent HIV prevention (2023). Available online at: https://data.unicef.org/topic/hivaids/adolescents-young-people/#:∼:text = HIV in Adolescents, of New Adult HIV Infections (accessed May 17, 2024).

5. WHO. Adolescent pregnancy (2024). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-pregnancy (accessed May 11, 2024).

6. Liang M, Simelane S, Fortuny Fillo G, Chalasani S, Weny K, Salazar Canelos P, et al. The state of adolescent sexual and reproductive health. J Adolesc Heal. (2019) 65:S3–S15. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.09.015

7. Lee H, Hirai AH, Lin CCC, Snyder JE. Determinants of rural-urban differences in health care provider visits among women of reproductive age in the United States. PLoS One. (2020) 15(12):e0240700. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240700

8. Ara I, Maqbool M, Gani I. Reproductive health of women: implications and attributes. Int J Cyrrent Res Physiol Pharmacol. (2022) 6:430–45.

9. Angona ANH, Hoque ATMR, Habib MA. A study on practice of reproductive health care facilities and family planning decisions of the rural adolescent in an area of Bogura district, Bangladesh. Int J Sci Bus. (2024) 35:96–111. doi: 10.58970/IJSB.2358

10. Reilly M. Health disparities and access to healthcare in rural vs. urban areas. Theory Action. (2021) 14:6. doi: 10.3798/tia.1937-0237.2109

11. Miller B, Baptist J, Johannes E. Health needs and challenges of rural adolescents. Rural Remote Health. (2018) 18(3):1–4. doi: 10.22605/RRH4325

12. Taiwo MO, Oyekenu O, Hussaini R. Understanding how social norms influence access to and utilization of adolescent sexual and reproductive health services in Northern Nigeria. Front Sociol. (2023) 8:1–8. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2023.865499

13. Hamdanieh M, Ftouni L, Al Jardali B, Ftouni R, Rawas C, Ghotmi M, et al. Assessment of sexual and reproductive health knowledge and awareness among single unmarried women living in Lebanon: a cross-sectional study. Reprod Health. (2021) 18:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12978-021-01079-x

14. Ninsiima LR, Chiumia IK, Ndejjo R. Factors influencing access to and utilisation of youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health services in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Reprod Health. (2021) 18:135. doi: 10.1186/s12978-021-01183-y

15. Ajibade BO, Oguguo C. Recommendations for removing access barriers to effective sexual/reproductive health services (SRHS) for young people in South East Nigeria: a systematic review. Int J Sexual Reprod Health Care. (2022) 5(1):047–60. doi: 10.17352/ijsrhc.000037

16. Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. Br Med J. (2021) 372:n160. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n160

17. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br Med J. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

18. Parums DV. Editorial: review articles, systematic reviews, meta-analysis, and the updated preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines. Med Sci Monit. (2021) 27:e934475. doi: 10.12659/MSM.934475

19. Munn Z, Barker TH, Moola S, Tufanaru C, Stern C, McArthur A, et al. Methodological quality of case series studies: an introduction to the JBI critical appraisal tool. JBI Database Syst Rev Implement Rep. (2020) 18(10):2127–33. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00099

20. Munn Z, Dias M, Tufanaru C, Porritt K, Stern C, Jordan Z, et al. The “quality” of JBI qualitative research synthesis: a methodological investigation into the adherence of meta-aggregative systematic reviews to reporting standards and methodological guidance. JBI Evi. Synt. (2021) 19:1119–39. doi: 10.11124/JBIES-20-00364

21. Ilori OO, Awodutire P, Ilori OO. Awareness and utilization of adolescent reproductive health services among in-school adolescents in urban and rural communities in Oyo state. Niger Med J. (2020) 61:67. doi: 10.4103/nmj.NMJ_38_19

22. Ilori ORS, Olarewaju SO, Awodutire PO, Ilori ORS, Bamidele JO. Expectations and experiences of urban and rural in-school adolescents of adolescent reproductive health services in Oyo state. J Public Health Afr. (2023) 14(11):2211. doi: 10.4081/jphia.2023.2211

23. Habte A, Dessu S. Uptake of sexual and reproductive health services and associated factors among rural adolescents in Southern Ethiopia, 2020. J Gynecol Reprod Med. (2021) 5:15–26.

24. Banerjee A, Paul B, Das R, Bandyopadhyay L, Bhattacharyya M. Utilisation of adolescent reproductive and sexual health services in a rural area of West Bengal: a mixed-method study. Malays Fam Physician. (2023) 18:1–10. doi: 10.51866/oa.179

25. Zuma T, Seeley J, Mdluli S, Chimbindi N, Mcgrath N, Floyd S, et al. Young people’s experiences of sexual and reproductive health interventions in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Int J Adolesc Youth. (2020) 25:1058–75. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2020.1831558

26. Adjie JS, Kurniawan AP, Surya R. Knowledge, attitude, and practice towards reproductive health issue of adolescents in rural area, Indonesia: a cross-sectional study. Open Public Health J. (2022) 15:1–7. doi: 10.2174/18749445-v15-e2206275

27. Reddy AAAKSS, Varanasi S, Ameer SR, Paul KK, Reddy AAAKSS. Knowledge, attitude, and practices related to reproductive and sexual health among adolescent girls in a rural community of Telangana. MRIMS J Heal Sci. (2022) 10:35–40. doi: 10.4103/mjhs.mjhs_20_21

28. Tiwari A, Wu W-J, Citrin D, Bhatta A, Bogati B, Halliday S, et al. “Our mothers do not tell us”: a qualitative study of adolescent girls’ perspectives on sexual and reproductive health in rural Nepal. Sex Reprod Heal Matters. (2022) 29(2):2068211. doi: 10.1080/26410397.2022.2068211

29. Mukandagano P, Mochama M, Rutayisire E, Mochama M, Mukandagano P. Reproductive health knowledge and services utilization among rural adolescents in Rwamagana district, Rwanda. J Public Heal Int. (2022) 5:9–22. doi: 10.14302/issn.2641-4538.jphi-22-4185

30. McGuire MF, Ortega E, Patel R, Paz-Soldán VA, Riley-Powell AR. Seeking information and services associated with reproductive health among rural Peruvian young adults: exploratory qualitative research from Amazonas, Peru. Reprod Health. (2024) 21:36. doi: 10.1186/s12978-024-01769-2

31. Yusup PM, Komariah N. Seputar pengalaman penduduk miskin pedesaan dalam mencari, menggunakan, dan mendokumentasikan informasi kesehatan. Lentera pustaka J kaji ilmu perpustakaan. Inf dan Kearsipan. (2017) 3(1):1–8. doi: 10.14710/lenpust.v3i1.16067

32. Idowu A, Kikelomo Israel O, Oluyemisi Akande R, Ayodele Aremu O, Toyin Olasinde Y. Sexual behaviour and determinants of reproductive health services utilization among young people in a rural Nigerian community. Cent Afr J Public Heal. (2021) 7:204. doi: 10.11648/j.cajph.20210704.19

33. Chimwaza-Manda W, Kamndaya M, Chipeta EK, Sikweyiya Y. Sexual health knowledge acquisition processes among very young adolescent girls in rural Malawi: implications for sexual and reproductive health programs. PLoS One. (2024) 19:e0276416. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0276416

34. Achen D, Nyakato VN, Akatukwasa C, Kemigisha E, Mlahagwa W, Kaziga R, et al. Gendered experiences of parent–child communication on sexual and reproductive health issues: a qualitative study employing community-based participatory methods among primary caregivers and community stakeholders in rural South-Western Uganda. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:5052. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19095052

35. Power R, Heanoy E, Das MC, Karim T, Muhit M, Badawi N, et al. The sexual and reproductive health of adolescents with cerebral palsy in rural Bangladesh: a qualitative analysis. Arch Sex Behav. (2023) 52:1689–700. doi: 10.1007/s10508-023-02535-4

36. Chilambe K, Mulubwa C, Zulu JM, Chavula MP. Experiences of teachers and community-based health workers in addressing adolescents’ sexual reproductive health and rights problems in rural health systems: a case of the RISE project in Zambia. BMC Public Health. (2023) 23(1):335. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-15199-5

37. Chilambe K, Mulubwa C, Zulu JM, Chavula MP, Chilambe K, Mulubwa C, et al. Experiences of teachers and community-based health workers in addressing adolescents’ sexual reproductive health and rights problems in rural health systems: a case of the RISE project in Zambia. BMC Public Health. (2023) 23:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-15199-5

38. Akatukwasa C, Kemigisha E, Achen D, Fernandes D, Namatovu S, Mlahagwa W, et al. Narratives of most significant change to explore experiences of caregivers in a caregiver-young adolescent sexual and reproductive health communication intervention in rural South-Western Uganda. PLoS One. (2023) 18:1–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0286319

39. Abraham G, Nebeb GT, Deressa BG, Megerssa B, Bayou NB, Teklehaymanot AN, et al. Rural adolescents: parental communication on sexual and reproductive health matters in Jimma Zone, Southwest Ethiopia. Int J Reprod Med. (2022) 2022:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2022/8033853

40. Jisso M, Feyasa MB, Medhin G, Dadi TL, Simachew Y, Denberu B, et al. Sexual and reproductive health service utilization of young girls in rural Ethiopia: what are the roles of health extension workers? Community-based cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. (2022) 12:e056639. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-056639

41. Natsayi C, Ursula N, Nothando N, Andrew G, Candice G, Guy H, et al. The sexual and reproductive health needs of school-going young people in the context of COVID-19 in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Afr J AIDS res. (2022) 21:162–70. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2022.2095921

42. Rasweth S, Nisha B. The unspoken plight of married adolescent girls in rural Tamil Nadu: narrative summary on unmet sexual and reproductive health needs and barriers. Indian J Community Heal. (2022) 34:439–43. doi: 10.47203/IJCH.2022.v34i03.023

43. Habte A, Dessu S. The uptake of key elements of sexual and reproductive health services and its predictors among rural adolescents in Southern Ethiopia, 2020: application of a Poisson regression analysis. Reprod Health. (2023) 20:15. doi: 10.1186/s12978-023-01562-7

44. Farahani FK. Adolescents and young people’s sexual and reproductive health in Iran: a conceptual review. J Sex Res. (2020) 57:743–80. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2020.1768203

45. Janighorban M, Boroumandfar Z, Pourkazemi R, Mostafavi F. Barriers to vulnerable adolescent girls’ access to sexual and reproductive health. BMC Public Health. (2022) 22:1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-14687-4

46. Finlay JE, Assefa N, Mwanyika-Sando M, Dessie Y, Harling G, Njau T, et al. Sexual and reproductive health knowledge among adolescents in eight sites across sub-Saharan Africa. Trop Med Int Heal. (2020) 25:44–53. doi: 10.1111/tmi.13332

47. Espinoza C, Samandari G, Andersen K. Abortion knowledge, attitudes and experiences among adolescent girls: a review of the literature. Sex Reprod Heal Matters. (2020) 28(1):1744225. doi: 10.1080/26410397.2020.1744225

48. Mattebo M, Bogren M, Brunner N, Dolk A, Pedersen C, Erlandsson K. Perspectives on adolescent girls’ health-seeking behaviour in relation to sexual and reproductive health in Nepal. Sex Reprod Healthc. (2019) 20:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.srhc.2019.01.006

49. Okeke CC, Mbachu CO, Agu IC, Ezenwaka U, Arize I, Agu C, et al. Stakeholders’ perceptions of adolescents’ sexual and reproductive health needs in Southeast Nigeria: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. (2022) 12. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051389

50. Cislaghi B, Heise L. Gender norms and social norms: differences, similarities and why they matter in prevention science. Sociol Heal Illn. (2020) 42:407–22. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.13008

51. Weber AM, Cislaghi B, Meausoone V, Abdalla S, Mejía-Guevara I, Loftus P, et al. Gender norms and health: insights from global survey data. Lancet. (2019) 393:2455–68. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30765-2

52. Daniels G, MacLeod M, Cantwell RE, Keene D, Humprhies D. Navigating fear, shyness, and discomfort during menstruation in Cambodia. PLOS Glob Public Heal. (2022) 2(6):e0000405. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0000405

53. Dessalegn M, Ayele M, Hailu Y, Addisu G, Abebe S, Solomon H, et al. Gender inequality and the sexual and reproductive health status of young and older women in the afar region of Ethiopia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:1–14. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124592

54. Kusheta S, Bancha B, Habtu Y, Helamo D, Yohannes S. Adolescent-parent communication on sexual and reproductive health issues and its factors among secondary and preparatory school students in Hadiya Zone, Southern Ethiopia: institution based cross sectional study. BMC Pediatr. (2019) 19:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12887-018-1388-0

55. Usonwu I, Ahmad R, Curtis-Tyler K. Parent–adolescent communication on adolescent sexual and reproductive health in sub-Saharan Africa: a qualitative review and thematic synthesis. Reprod Health. (2021) 18:1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12978-021-01246-0

56. Ivanova O, Rai M, Mlahagwa W, Tumuhairwe J, Bakuli A, Nyakato VN, et al. A cross-sectional mixed-methods study of sexual and reproductive health knowledge, experiences and access to services among refugee adolescent girls in the Nakivale refugee settlement, Uganda. Reprod Health. (2019) 16:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12978-019-0698-5

57. Mason-Jones AJ, Freeman M, Lorenc T, Rawal T, Bassi S, Arora M. Can peer-based interventions improve adolescent sexual and reproductive health outcomes? An overview of reviews. J Adolesc Heal. (2023) 73:975–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2023.05.035

58. Siddiqui M, Kataria I, Watson K, Chandra-Mouli V. A systematic review of the evidence on peer education programmes for promoting the sexual and reproductive health of young people in India. Sex Reprod Heal Matters. (2020) 28(1):1741494. doi: 10.1080/26410397.2020.1741494

59. Nmadu AG, Mohamed S, Usman NO. Adolescents’ utilization of reproductive health services in Kaduna, Nigeria: the role of stigma. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud. (2020) 15:246–56. doi: 10.1080/17450128.2020.1800156

60. Yibrehu MS, Mbwele B. Parent—adolescent communication on sexual and reproductive health: the qualitative evidences from parents and students of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Reprod Health. (2020) 17:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12978-020-00927-6

61. Alomair N, Alageel S, Davies N, Bailey JV. Factors influencing sexual and reproductive health of muslim women: a systematic review. Reprod Health. (2020) 17:1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12978-020-0888-1

62. Abdul Hamid SH, Fallon D, Callery P. Influence of religion on healthcare professionals’ beliefs toward teenage sexual practices in Malaysia. Makara J Heal Res. (2020) 24(1):5. doi: 10.7454/msk.v24i1.1175

63. Eze II, Okeke C, Ekwueme C, Mbachu CO, Onwujekwe O. Acceptability of a community-embedded intervention for improving adolescent sexual and reproductive health in south-east Nigeria: a qualitative study. PLoS One. (2023) 18(12):e0295762. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0295762

64. Phulambrikar RM, Kharde AL, Mahavarakar VN, Phalke DB, Phalke VD. Effectiveness of interventional reproductive and sexual health education among school going adolescent girls in rural area. Indian J Community Med. (2019) 44:378–82. doi: 10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_155_19

65. Thongmixay S, Essink DR, De Greeuw T, Vongxay V, Sychareun V, Broerse JEW. Perceived barriers in accessing sexual and reproductive health services for youth in Lao people’s democratic republic. PLoS One. (2019) 14:1–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218296

66. Abuosi AA, Anaba EA. Barriers on access to and use of adolescent health services in Ghana. J Heal Res. (2019) 33:197–207. doi: 10.1108/JHR-10-2018-0119

67. Sutton MY, Anachebe NF, Lee R, Skanes H. Racial and ethnic disparities in reproductive health services and outcomes, 2020. Obstet Gynecol. (2021) 137:225–33. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004224

68. Gruskin S, Yadav V, Castellanos-Usigli A, Khizanishvili G, Kismödi E. Sexual health, sexual rights and sexual pleasure: meaningfully engaging the perfect triangle. Sex Reprod Heal Matters. (2019) 27:29–40. doi: 10.1080/26410397.2019.1593787

69. Mac-Seing M, Zinszer K, Eryong B, Ajok E, Ferlatte O, Zarowsky C. The intersectional jeopardy of disability, gender and sexual and reproductive health: experiences and recommendations of women and men with disabilities in Northern Uganda. Sex Reprod Heal Matters. (2020) 28:1772654. doi: 10.1080/26410397.2020.1772654

70. Desrosiers A, Betancourt T, Kergoat Y, Servilli C, Say L, Kobeissi L. A systematic review of sexual and reproductive health interventions for young people in humanitarian and lower-and-middle-income country settings. BMC Public Health. (2020) 20:1–21. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08818-y

71. Violita F, Hadi EN. Determinants of adolescent reproductive health service utilization by senior high school students in Makassar, Indonesia. BMC Public Health. (2019) 19:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6587-6

Keywords: adolescent, rural, reproductive health, barriers, awareness, knowledge, social norms

Citation: Wahyuningsih S, Widati S, Praveena SM and Azkiya MW (2024) Unveiling barriers to reproductive health awareness among rural adolescents: a systematic review. Front. Reprod. Health 6:1444111. doi: 10.3389/frph.2024.1444111

Received: 5 June 2024; Accepted: 4 November 2024;

Published: 19 November 2024.

Edited by:

Charikleia Stefanaki, UNESCO Chair in Adolescent Health Care, GreeceReviewed by:

Elizabeth Schmidt, Lincoln Memorial University, United StatesHenry Wasswa, Amref Health Africa, Kenya

Copyright: © 2024 Wahyuningsih, Widati, Praveena and Azkiya. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sri Widati, c3JpLXdpZGF0aUBma20udW5haXIuYWMuaWQ=

Sri Wahyuningsih1

Sri Wahyuningsih1 Sri Widati

Sri Widati Sarva Mangala Praveena

Sarva Mangala Praveena Mohammad Wavy Azkiya

Mohammad Wavy Azkiya