- 1Department of Health Policy & Behavioral Sciences, School of Public Health, Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA, United States

- 2Department of Medicine, Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital, Kumasi, Ghana

- 3Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia

- 4Suntreso Government Hospital, Kumasi, Ghana

Background: Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-related stigma has been identified as one of the principal factors that undermines HIV prevention efforts and the quality of life of people living with HIV (PLWH) in many developing countries including Ghana. While studies have been conducted on HIV-related stigma reduction, very few have sought the views of PLWH on how this might be done. The purpose of the study was to (i) identify factors that cause HIV-related stigma in Ghana from the perspective of PLWH, (ii) identify challenges that HIV-related stigma poses to the treatment and care of PLWH, and (iii) to obtain recommendations from PLWH on what they think various groups (community members, health care providers, and adolescents) including themselves should do to help reduce HIV-related stigma in Ghana.

Methods: A mixed methods cross-sectional study design was used to collect data from 404 PLWH at the Suntreso Government Hospital in the Kumasi Metropolis of Ghana across six domains using Qualtrics from November 1–30, 2022. Quantitative data was analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26 and the Statistical Analysis System (SAS) version 9.4. Qualitative data was analyzed using a thematic approach.

Results: Most of the study participants (70.5%) said HIV-related stigma in Ghana is due to ignorance. Of this population, 90.6% indicated that they had experienced stigma because they have HIV, causing them to feel depressed (2.5%), ashamed (2.2%), and hurt (3.0%). Study participants (92.8%) indicated that the challenges associated with HIV-related stigma has affected their treatment and care-seeking behaviors. Recommendations provided by study participants for HIV destigmatization include the need for PLWH not to disclose their status (cited 94 times), community members to educate themselves about HIV (96.5%), health care providers to identify their stigmatizing behaviors (95.3%), health care providers to avoid discriminating against PLWH (96.0%), and the need for adolescents to be educated on HIV and how it is transmitted (97.0%).

Conclusion: It is important for the government and HIV prevention agencies in Ghana to target and address co-occurring HIV-related stigma sources at various levels of intersection simultaneously This will help to shift harmful attitudes and behaviors that compromise the health and wellbeing of PLWH effectively.

1. Introduction

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a major threat to the health and quality of life of populations globally. Emerging in the 1980s, HIV attacks, destroys, and weakens the body's immune system against infections (1), and puts infected persons at risk for opportunistic infections such as tuberculosis, severe bacterial infections, and some cancers that their bodies would normally have been able to fend off (2). In 2022, about 38.4 million people were living with HIV (PLWH), 1.5 million had acquired new HIV infections, and 650,000 had died from HIV-related causes globally (3). In that same year, sub-Saharan Africa, which accounts for 15% of the global population (4), had 28 million PLWH, 425,100 AIDS-related deaths, and 874,000 new HIV infections (5), with Ghana, a country in sub-Saharan Africa, accounting for about 345,599 PLWH, 9,859 deaths from AIDS-related causes, and about 16,938 new HIV infections (6, 7). It was in the bid to address the HIV epidemic that the global community launched the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in 2000, and the subsequent Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015, with their respective targets of reversing HIV by 2015 (MDG 6) and eliminating HIV by 2030 (SDG 3) (8, 9). Owing to these global efforts, public health interventions and campaigns, scientific advances, and technologies such as HIV testing, voluntary counselling and testing (VCT), and antiretroviral therapy (ART), have been developed and implemented across the globe to control and prevent HIV (10). In spite of these efforts, HIV prevention continues to be a global health issue, thanks to the stigma associated with the disease.

Ghana is a country in West Africa located on the Gulf of Guinea. It is bounded to the West by Côte d'Ivoire, the East by Togo, and the North by Burkina Faso. Ghana covers an area of about 238,553 km2 and has a population of about 33 million people (11) living in 16 administrative regions and 216 districts (12). In 2020, the overall HIV prevalence rate in Ghana was 1.6% with regional variation (7). Kumasi, a district in the Ashanti region and Accra, a district in the Greater Accra region of Ghana, were reported to have largest numbers of PLWH (7), with the Ashanti region accounting for 76, 672 of that population. Some reasons cited for HIV prevalence in Kumasi are low condom use, high female sex worker activities, infected people not beginning treatment due to the fear of stigma, risky sexual behavior, increased commercial activity, concealment of HIV status among couples, and low socio-economic status (13). To stem the HIV tide, the government of Ghana has expanded access to treatment and care, and is implementing national as well as international programs such as the World Health Organization's TREAT ALL policy (14). This notwithstanding, the stigma related to HIV continues to derail established prevention, treatment, and care efforts.

HIV-related stigma is the prejudice, negative beliefs, feelings, and attitudes towards PLWH, their families, and those who take care of them (15). It is a multidimensional social construct that is not only shaped by individual perceptions and interpretations of microlevel interactions but also by social and economic forces (16). HIV-related stigma significantly impacts the life experiences of individuals both infected and affected by the disease. It manifests in various forms including discrimination, avoidance behavior (refusal to share food or sit by), social rejection (shunning by family members, peers, and the wider community), the erosion of rights, psychological damage, labeling of people as “socially unacceptable”, and the perpetration of physical violence (16). HIV-related stigma may be external or internal (17). External stigma is the actual experience of discrimination, while internal stigma (felt or imagined stigma) is the shame associated with HIV and PLWHs’ fear of being discriminated against (17–19). Internal stigma is a survival mechanism that protects PLWH from external stigma and often results in thoughts or behaviors such as the refusal or reluctance to disclose a positive HIV status, denial of HIV, and an unwillingness to accept help (18, 20–22).

In Ghana, HIV is a disease associated with certain key populations (men who have sex with men (MSM), people who inject drugs, and sex workers). The notion that the disease is solely transmitted through sex and is the consequence of weak morals, sexual promiscuity and personal irresponsibility that deserves to be punished, have contributed to the stigma and discrimination associated with the disease (15). Thus, HIV-related stigma has driven PLWH and key populations to the margins of society where the fear of gossip, verbal abuse, rejection or even violence, makes getting tested, disclosing one's HIV status, or accessing HIV treatment and care very difficult (23).

HIV-related stigma is not only associated with whether a person is living with the disease or not, but also their gender identity, sexual orientation, engagement in sex work, place of treatment, who their health care provider is, and the communities in which they live (24). Therefore, to successfully reduce HIV-related stigma in Ghana, it is important to target and address co-occurring HIV-related stigma sources at various levels of intersection simultaneously as well as among PLWH (24). While studies have been conducted on HIV-related stigma reduction, very few have sought the views of PLWH on how this might be achieved. The purpose of the study was to (i) identify factors that cause HIV-related stigma in Ghana from the perspective of PLWH, (ii) identify challenges that HIV-related stigma poses to the treatment and care of PLWH, and (iii) to obtain recommendations from PLWH on what they think various groups (community members, health care providers, and adolescents) including themselves, should do to help reduce HIV-related stigma in Ghana. The results from the study have been used to inform content and strategies for interventions to reduce HIV-related stigma and discrimination in Ghana.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Setting and population

The study was conducted at the Suntreso Government Hospital situated in the Kumasi Metropolis in the Ashanti region of Ghana. The hospital is a leading provider of quality community-oriented health care including pediatrics, disease control, HIV, obstetrics, gynecology, and surgery. It is also the home of several sexually transmitted infection and HIV clinics with over 9,000 patients.

2.2. Sampling and data collection

We conducted a cross-sectional, mixed methods study of PLWH who utilize HIV services at the Suntreso Government Hospital. Using convenient sampling, data was collected over a period of four weeks in October 2022 on study participants perceptions of the causes of HIV-related stigma in Ghana, the challenges HIV-related stigma poses to their treatment and care, and recommendations for destigmatizing HIV-related stigma in Ghana. Study participants were privately informed about the study at the HIV clinic and pharmacy waiting areas where they go to collect their medication. PLWH who volunteered to participate in the study were invited to a private room by the pharmacy where they met with a research assistant who explained the purpose and nature of the study and emphasized the voluntary nature of the study before data collection commenced. Study participants completed a one-time six-minute online survey created in Qualtrics. They gave their consent to participate in the study by completing the survey. No personally identifiable information was collected. Quantitative and qualitative data were collected daily.

2.3. Ethical approval

Approval for the study was obtained from the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in Kumasi, Ghana.

2.4. Variables and measurement

The study questionnaire comprised 18 quantitative and qualitative questions across six domains—(i) demographic information, (ii) causes of HIV-related Stigma in Ghana, (iii) individual stigma, (iv) interpersonal stigma, (v) challenges of HIV-related stigma for HIV treatment and care, and (vi) recommendations for HIV destigmatization in Ghana. The demographics variable focused on the sex, age, and educational level of participants. The causes of HIV-related stigma in Ghana variable focused on what study participants believe are the causes of HIV-related stigma in Ghana. The individual and interpersonal stigma variables focused on study participants personal experience of HIV-related stigma, how they felt because of the experience, and the outcomes of the experience. The challenges of HIV-related stigma for HIV treatment and care variable focused on the effects of the stigma experienced on study participant treatment and care in the past 12 months. The recommendations for HIV destigmatization variable focused on what study participants believe will help to reduce HIV-related stigma in Ghana as well as what should be done at the community, care provider, adolescent, caregivers, sex workers and MSM levels to reduce HIV-related stigma in Ghana.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Data collected was cleaned and exported from Qualtrics to the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 26 and the Statistical Analysis System version 9.4 for quantitative analysis. Missing quantitative data were excluded from calculations. Qualitative data was manually extracted from the SPSS database and analyzed using a thematic approach. Analyzed qualitative data are presented verbatim (in italics) to convey exactly what study participants said in explanation to certain questions.

3. Results

3.1. Univariate analysis

3.1.1. Demographic information

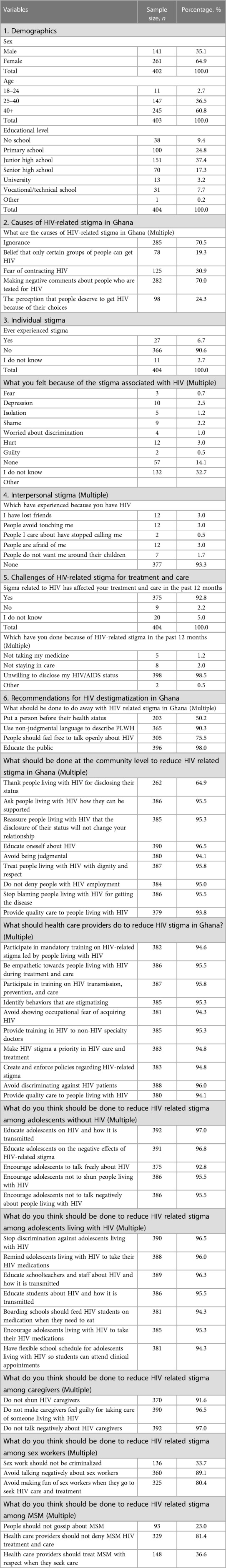

A total of 404 PLWH who utilize health services at the Suntreso Government hospital in Kumasi participated in the survey. Majority were female (64.9%), and more than half (60.8%) were 41 years old and above. Over a third of the study participants (37.4%) had completed junior high school, and a few had completed either senior high school (17.3%), vocational school (7.7%) or any formal education (9.4%) (Table 1).

3.1.2. Causes of HIV-related stigma in Ghana

In response to what causes of HIV-related stigma in Ghana, the study participants said ignorance (70.5%), the belief that only certain groups of people can get HIV (9.3%), the fear of contracting HIV (30%) and negative comments made about people who get tested for HIV (70%). In addition, some study participants stated that people deserve to have HIV because of their choices (24.3%) and others (5.6%) said they did not know (Table 1).

3.1.3. Individual and interpersonal stigma

Regarding individual stigma, 90.6% of the study participants acknowledged ever experiencing stigma because they have HIV. This, they said, made them feel depressed (2.5%), shame (2.2%), hurt (3.0%), and worried about discrimination (1.0%). A few of the study participants (14.1%) said that they were not bothered about HIV-related stigma or felt nothing, and a third (32.7%) stated that they did not know. When it came to what they have experienced as a result of the stigma related to HIV, 3.0% of the study participants respectively indicated that they have lost friends, people are afraid of them, and people avoid touching them (Table 1).

3.1.4. Challenges of HIV-related stigma for treatment and care

When asked about whether HIV-related stigma has affected their treatment and care in the past 12 months, 92.8% of the study participants said yes, 2.2% said no, and 5.0% said they did not know. Those who said yes said it was because they felt ashamed (cited 2 times) and did not want to be seen at the health facility (cited 2 times). On what they had done because of HIV-related stigma they experienced in the past 12 months, many of the participants (98.5%) stated that they were unwilling to disclose their HIV status, 1.2% said they had stopped taking their medication, and 2.0% reported that they had stopped staying in care (Table 1).

3.1.5. Recommendations for reducing HIV-related stigma in Ghana

Study participants provided recommendations on what they think various groups in Ghana (community members, health care providers, and adolescents) including themselves should do to help reduce HIV-related stigma. The recommendations are presented below. They can be used for the development of evidence-based HIV destigmatization interventions.

3.1.6. PLWH

There were 246 qualitative responses for what PLWH should do to reduce HIV-related stigma. Using a thematic approach, eight themes emerged from the qualitative analysis: (i) HIV status disclosure to peers, friends and family; (ii) awareness creation and education of the public on HIV; (iii) correct misconceptions; (iv) confidence; (v) legal action and support; (vi) avoid self-stigma, (vii) treatment, and (viii) educate oneself about HIV.

As part of their recommendations, the majority of the study participants proposed that PLWH should avoid disclosing their HIV status to peers, friends, and family (cited 94 times). Others recommended that PLWH need to create awareness and educate the public on HIV (cited 48 times), correct people’s misconceptions related to HIV (cited 36 times), be confident (cited 18 times), seek legal action and support (cited 13 times), avoid self-stigma (cited 14 times), seek treatment (cited 13 times), and educate themselves about HIV (cited 2 times). Some of the things they specifically said were:

“Never disclose your HIV status to people, especially life partners.”

“We must educate the community about certain misconceptions since most of the stigma is centered in the community”.

“Fight for our right by taking legal actions.”

3.1.7. Community level

Regarding what should be done at the community level to reduce HIV-related stigma in Ghana, 64.9% of the study participants said community members should thank PLWH when they disclose their status, 95.5% said ask PLWH how they can be supported, and 95.3% said reassure PLWH that the disclosure of their status will not change the nature of their relationships. Additionally, 96.5% of the study participants stated that community members need to educate themselves about HIV, 94.1% said avoid being judgmental of PLWH, and 95.8% said treat PLWH with dignity and respect (Table 1).

3.1.8. Health care provider level

In response to what health care providers should do to reduce HIV-related stigma in Ghana, majority (96.6%) of the study participants suggested that health care providers should participate in mandatory training on HIV-related stigma led by PLWH, be empathetic to PLWH during treatment and care (95.5%), participate in training on HIV transmission, prevention, and care (95.8%), and identify behaviors that are stigmatizing (95.3%). In addition, study participants (94.3%) stated that health care providers need to avoid showing occupational fear of acquiring HIV, ensure that training in HIV is provided to non-HIV specialty health care providers (95.3%), make HIV-related stigma a priority in HIV care and treatment (94.8%), and develop and enforce policies regarding HIV-related stigma (94.8%) (Table 1).

3.1.9. Adolescent level

When it came to what should be done to reduce HIV-related stigma among adolescents who do not have HIV, responses from participants included educate adolescents on HIV and how it is transmitted (97.0%), educate adolescents on the negative effects of HIV-related stigma (96.8%), and encourage adolescents to talk freely about HIV (92.8%). Regarding what should be done to reduce HIV related stigma among adolescents living with HIV, majority of the study participants (96.5%) said discrimination against adolescents living with HIV should be stopped. Other participants said remind adolescents living with HIV to take their HIV medications (96.0%), and educate school teachers and staff about HIV and how it is transmitted (96.3%). Additionally, 94.3% of the study participants said boarding schools should feed HIV students when they need to eat so they can take their medications on time, and 94.3% said schools should have flexible schedules for adolescents living with HIV so they can keep their clinical appointments.

3.1.10. Caregivers and sex workers

On the issue of what should be done to reduce HIV related stigma among caregivers, recommendation from participants include not to shun HIV caregivers (91.6%), not to make caregivers feel guilty for taking care of someone living with HIV (96.5%), and the need to not talk negatively about HIV caregivers (97.0%). To reduce HIV-related stigma among sex workers, 33.7% of the study participants proposed that sex work should not be criminalized and 89.1% said people should avoid talking negatively about sex workers (Table 1).

3.1.11. Men who have sex with men

Regarding reducing HIV-related stigma among MSM, the study participants said people should not gossip about MSM (23.0%), health care providers should not deny MSM treatment and care (81.4%), and health care providers should treat MSM with respect when they seek care (36.6%).

3.2. Bivariate and multivariate analysis

Using cross tabulation, we conducted bivariate analysis of age, sex, and education by the perceptions of PLWH on the factors that cause HIV-related stigma in Ghana, challenges HIV-related stigma poses for HIV treatment and care among PLWH, and what should be done at the community, health care provider, and adolescent levels to reduce HIV related stigma in Ghana.

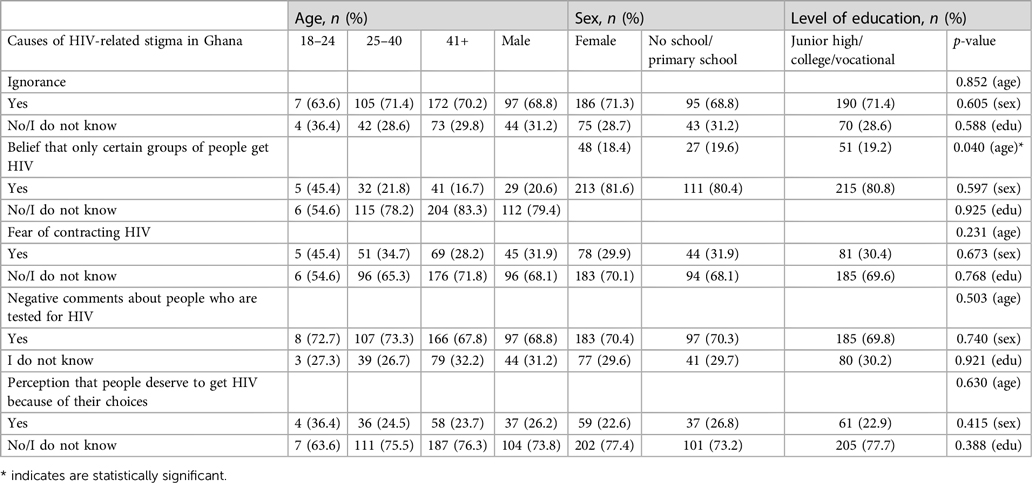

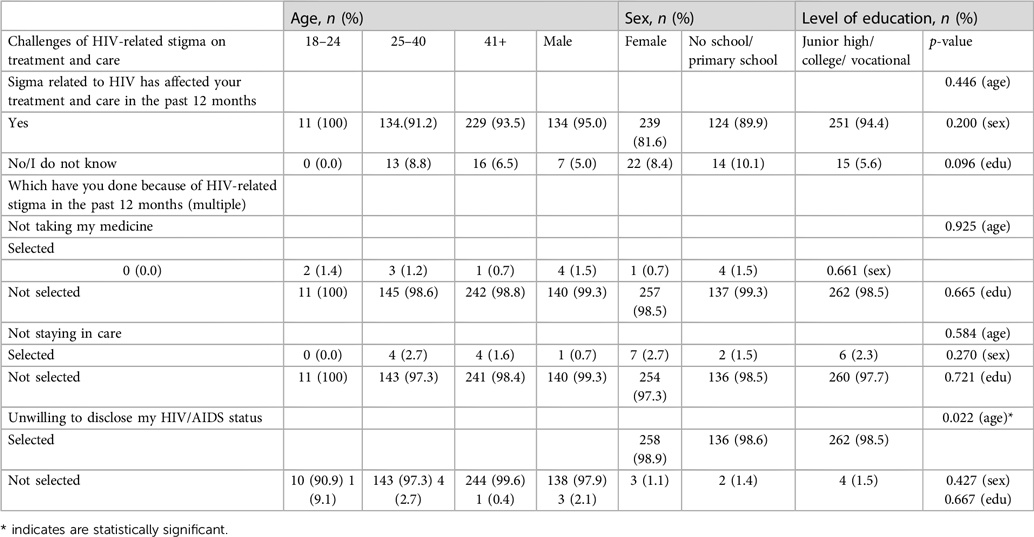

With regards to the causes of HIV-related stigma in Ghana by age, sex, and education, we found a significant relationship with age (p-value = 0.040) (Table 2A). We did not find any significant relationships with the other variables. When it came to the challenges HIV-related stigma poses for treatment and care among PLWH, we again found a significant relationship with age (p-value = 0.022) (Table 2B). On what can be done to reduce HIV-related stigma at the community level in Ghana by sex, age and education, there was significant a relationship between education and thanking PLWH for disclosing their status (p-value = 0.003) (Table 2C). We also found significant relationships between age and the remaining variables in the domain. Specifically, there were significant relationships between age and reassuring PLWH that the disclosure of their status will not change their relationship (p-value = 0.008), educating oneself about HIV (p-value = 0.018), avoiding being judgmental (p-value = 0.016), treat PLWH with dignity (p-value = 0.001), do not deny PLWH employment (p-value = 0.015), stop blaming PLWH for getting the disease (p-value = 0.011), and provide quality care to PLWH (p-value = 0.041).

Table 2B. Bivariate analysis of sex, age, and education by challenges of HIV-related stigma on treatment and care.

Table 2C. Bivariate analysis of sex, age, education by what should be done at the community level to reduce HIV-related stigma in Ghana.

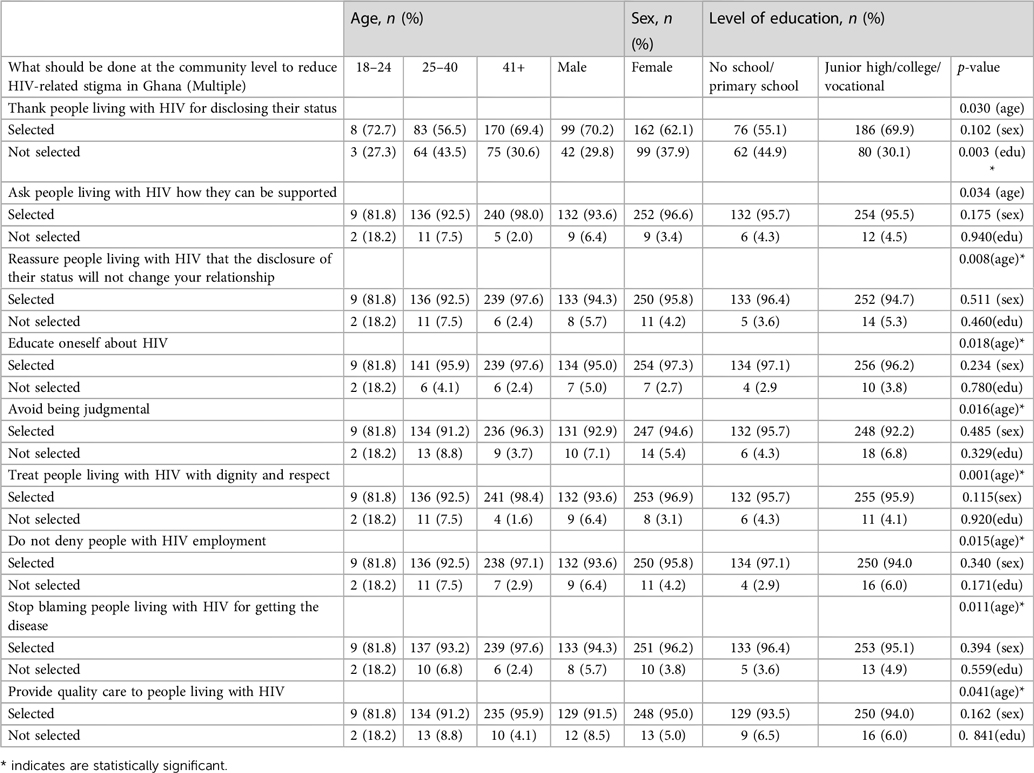

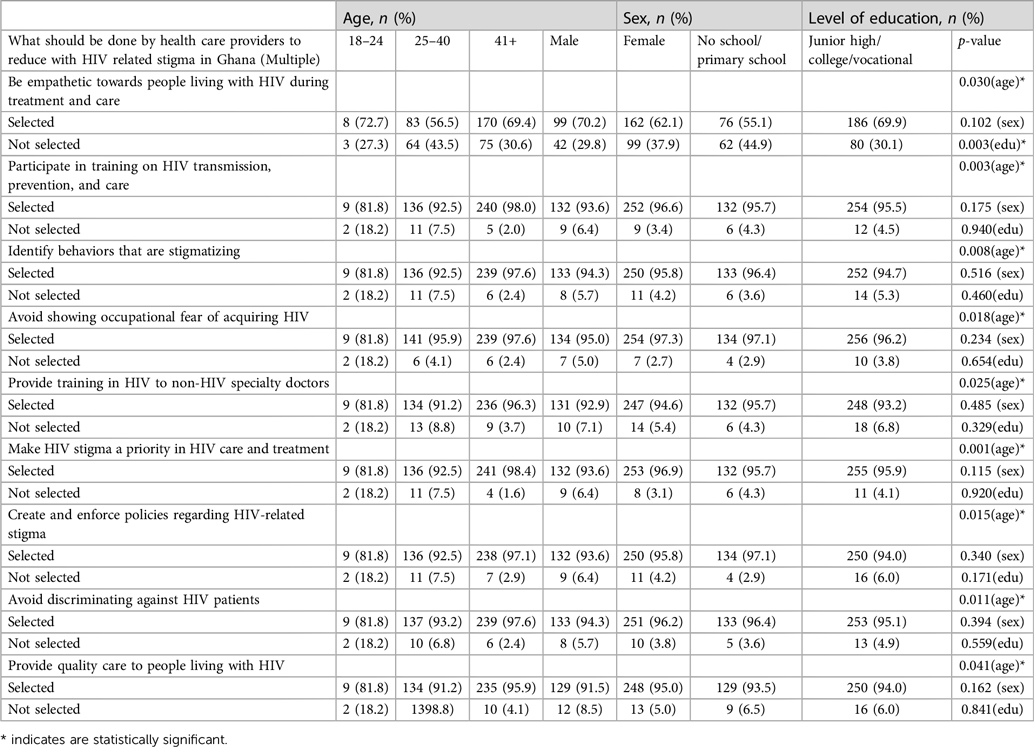

There were also significant relationships between what should be done by health care providers to reduce HIV-related stigma in Ghana by sex, age, and education. Specifically, Table 2D shows significant relationships between age and the need to be empathetic towards PLWH during treatment and care (p-value = 0.030), participation in training on HIV transmission, prevention, and care (p-value = 0.003), identifying behaviors that are stigmatizing (p-value = 0.008), avoid showing occupational fear of acquiring HIV (p-value = 0.018), make HIV stigma a priority in HIV care and treatment (p-value = 0.001), and creating and enforcing policies regarding HIV-related stigma (p-value = 0.015).

Table 2D. Bivariate analysis of sex, age, education by what should be done by health care providers to reduce HIV-related stigma in Ghana.

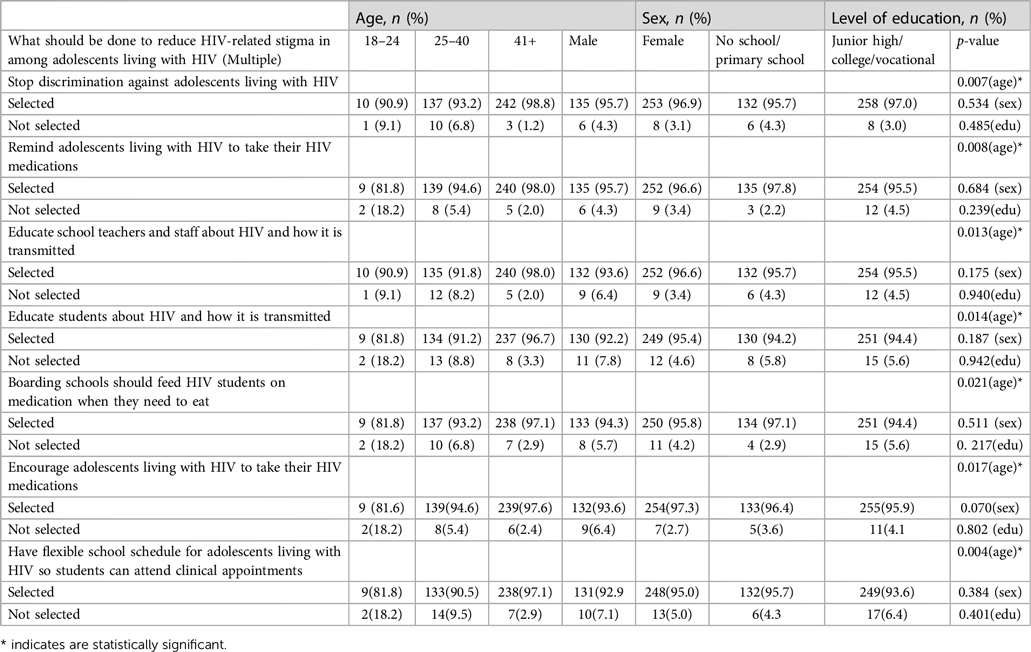

We further found significant relationships between what should be done to reduce HIV-related stigma among adolescents living with HIV in Ghana by sex, age, and education, with age being the most significant variable. There were also significant relationships between age and stopping discrimination against adolescents living with HIV (p-value = 0.007), educating schoolteachers and staff about HIV and how it is transmitted (p-value = 0.013), educating students about HIV and how it is transmitted (p-value = 0.014), boarding schools should feed HIV students on medication when they need to eat (p-value = 0.021), and having flexible school schedule for adolescents living with HIV so students can attend clinical appointments (Table 2E).

Table 2E. Bivariate analysis of sex, age, education by what should be done to reduce HIV-related stigma among adolescents living with HIV in Ghana.

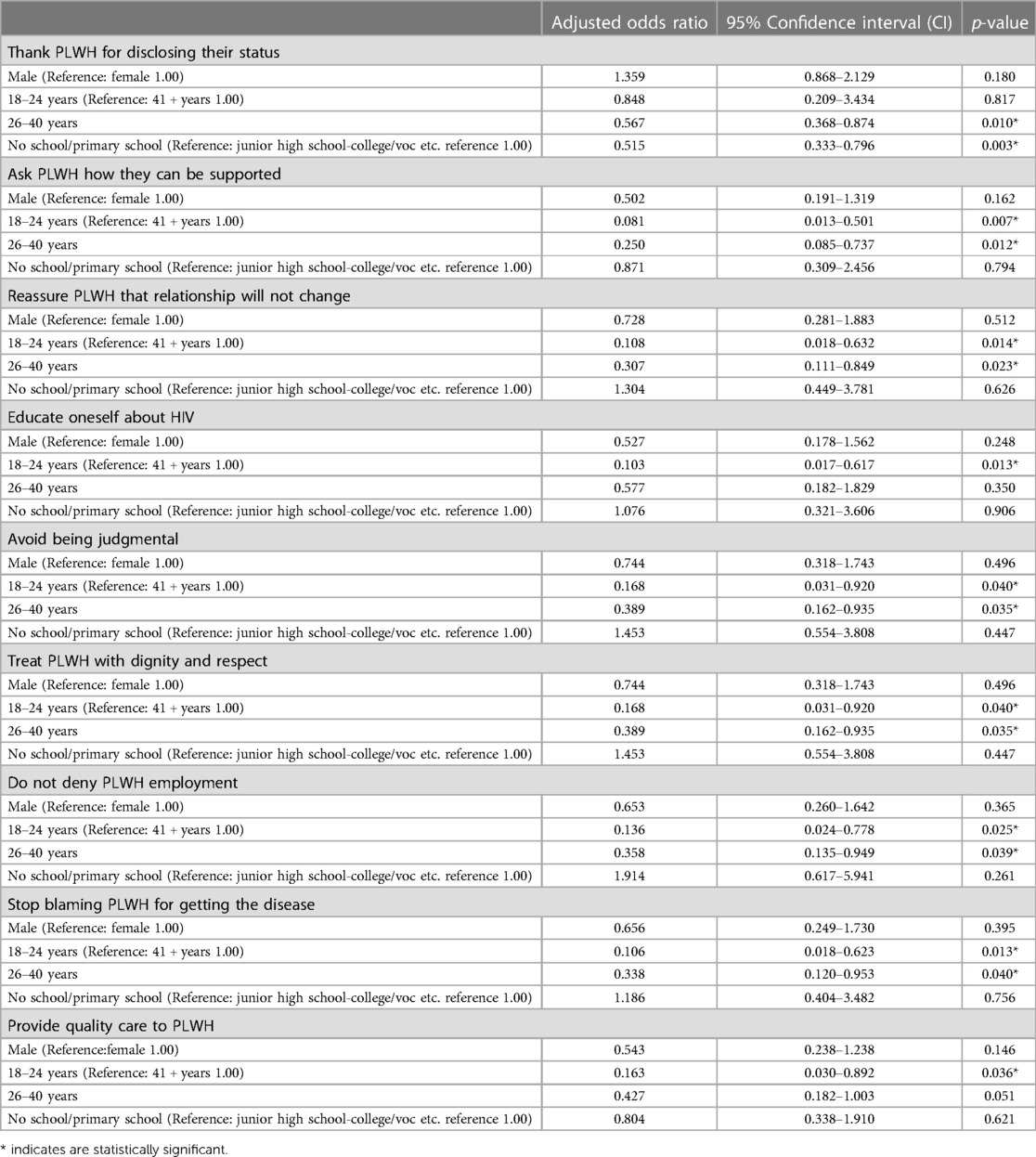

We conducted a multivariate analysis. After adjusting for demographic variables (sex, age, and education) and community recommendations to reduce HIV-related stigma in Ghana, we found that age and education were significant. Study participants aged 26–40 were 53.3% less likely to be thankful to PLWH for disclosing their status compared to participants who were 41 years and above (AOR 0.567, CI 0.368–0874, p-value = 0.010) (Table 3). Also, participants with no school or only primary school education, were 48.5% less likely to be thankful compared to participants with junior high or college education (AOR 0.515, CI 0.333–0796, p-value = 0.003) (Table 3). When it came to supporting PLWH, after we adjusted for sex, age and education, education was significant. Study participants aged 18–24 years were 91.9% less likely to support PLWH than participants aged 41 years and above (AOR 0.081, CI 0.013–0510, p-value = 0.007). Study participants who were 26–40 years were 75% less likely than participants aged 41 years and above to show support for PLWH (AOR 0.250, CI 0.085–0.737, p-value = 0.012) (Table 3). We found that study participants who were 18–24years old were 89.7% less likely than those who were 41 years and above to select educating oneself as a means to reduce HIV-related stigma at the community level (AOR 0.103, CI 0.017–0.617, p-value = 0.013) (Table 3).

Table 3. Multivariate analysis of age, sex, and education by what the community can do to reduce HIV-related stigma in Ghana.

4. Discussion

The study examined PLWH perceptions of the causes of HIV-related stigma in Ghana, challenges that HIV-related stigma poses to treatment and care for PLWH, and recommendations on what can be done to reduce HIV-related stigma among various groups in Ghana (community members, health care providers, and adolescents living with HIV) including PLWH. In so doing, it addressed a gap in the literature around what PLWH believe are the causes of HIV-related stigma in Ghana, how HIV-related stigma impacts their ability to seek treatment and care, and what PLWH recommend various groups in Ghana do to reduce the stigma associated with HIV.

4.1. Causes of HIV-related stigma in Ghana

Ignorance is the main cause of HIV-related stigma in Ghana. The majority of PLWH (70.5%) who participated in the study indicated that ignorance is a contributing factor to the stigma associated with HIV in Ghana. This is not uncommon in many parts of sub-Saharan Africa including Ghana where cultural norms, and social pressure cause people to not want to be associated with the disease, let alone learn about it. This is an issue, as knowledge about HIV has been associated with reducing stigma. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the lack of knowledge about HIV causes people to fear the disease, leading to negative judgements about PLWH. (25) In their study on HIV-related stigma and discrimination in Ghana, Tenkorang et al. corroborated the CDC finding. They found that Ghanaian men and women with relatively high knowledge about HIV/AIDS had low stigmatizing and discriminatory attitudes (26).

The majority of study participants who believed that ignorance about HIV was the cause of HIV-related stigma in Ghana were 41 + years. This finding is consistent with a 2019 survey conducted on HIV stigma knowledge, which noted that despite scientific advances and decades of HIV advocacy and education, young adults and adolescents overwhelmingly lack information about the basics of HIV and their HIV status (27). It is therefore not surprising that older people worldwide are more aware of their HIV status compared to younger people. Of the estimated 1.2 million people in the United States (US) living with HIV in 2019, for every 100 people of that population aged 13–24 years, 56 knew their HIV status. Among people aged 25–34 years, 72 knew their status, and among people aged 45 and above, about 92 knew their HIV status (28). This statistic for the younger population needs to be reversed as awareness of one's HIV status is a crucial step to HIV transmission prevention.

4.2. Challenges of HIV-related stigma for HIV treatment and care

In our study, we found that age was significantly associated with adherence to HIV treatment and care. Taking HIV medication sometimes requires PLWH to divulge their diagnosis to others, especially when bottles of pills are found in their possession, or when they are seen taking a particular type of pill (29). The stigma associated with taking antiviral medications has the tendency to reduce medication adherence among PLWH. This is consistent with the findings of Golin et al. who reported that younger HIV-infected adults were likely to be nonadherent to medications due to the fear of stigma and potential rejection by friends or family (30). In research conducted in 10 HIV treatment programs in Burundi, Cameroon and the Democratic Republic of Congo, Newman et al. (2012) found that PLWH who were ≥50 years of age had 1.6 times the odds of being adherent to their HIV medications compared to their younger counterparts (people 18–49 years of age) (31). In Spain, Branas et al. (2008) compared rates of ART adherence between PLWH who were ≥65 years of age to PLWH who were less than 65 years. They found that although the difference in adherence was not statistically significant, a greater proportion of PLWH who were ≥65 (70.8%) reported ≥95 percent adherence compared to PLWH who were 65 years of age or younger (58.1%) (32).

4.3. Recommendations for reducing HIV-related stigma in Ghana

4.3.1. Community members

Oftentimes, the behavior of distant relatives, friends, and fellow employees in Ghana, contribute to HIV-related stigma among PLWH (33). This is consistent with a 2014 Ghana Development Health Survey finding that showed that very few (22%) study participants expressed positive attitudes towards HIV stigma indicators (34). Additionally, in their study on families and communities living with HIV in Taiwan, Manijsin et al. found that over 25% of young adults were worried about their chances of contracting HIV because they were either living or working in close proximity with PLWH, sharing meals, glasses, or eating meals prepared by PLWH (35). A qualitative study conducted in Liuzhou, China among PLWH found that PLWH who were stigmatized by their family also faced discrimination at work and got fired once their HIV-positive status was known (36). The results of another study conducted in Ghana on HIV-related stigma showed that 12% of the study participants indicated that they would change jobs if someone they worked with became infected with HIV (15). In a cross-sectional survey on perceived discrimination conducted among 451 PLWH and 292 caregivers in Haiti, researchers found that 32% of caretakers and their children experienced discrimination. These situations demonstrate how the rights of PLHW, and their families have been violated due to stigma (37). The negative behavior of community members towards PLWH constitutes a major drawback in the fight against HIV (38). Educating community members on HIV, how it is transmitted, strengthening social support systems, and implementing culturally appropriate educational interventions may help to reduce community-related HIV stigma (4). This is consistent with a previous study conducted by Brown et al., which found that PLWH engagement with community members contributed to generating empathy, dispelling HIV misinformation, and lowering stigma associated with PLWH (39).

Unfortunately, the place PLWH go to seek treatment and care in Ghana, is one of the places where they encounter serious forms of stigmatization and discrimination (40). A cross-sectional study conducted in three hospitals in Cape Coast, Ghana, in 2017, found that health care providers minimized contact with PLWH, denied them care, avoided treating them or isolated PLHW from other patients (41, 42). Reasons for such behavior included the fear of getting infected with HIV in the course of their work, and their negative opinions about PLWH. These are also some of the reasons participants in our study mentioned (41). The same cross-sectional study also found that nurses were more likely than medical doctors to exhibit stigmatizing behavior (41). A study conducted in five African countries found higher levels of HIV-related stigma among nurses towards PLWH. This is worrying, given the fact that nurses are usually the frontline staff who provide health care services to HIV patients (43). While Ghana has made some strides to control HIV, the gains may be eroded if HIV-related stigma among health care providers is not addressed.

4.3.2. Adolescents living with HIV

HIV prevalence among adolescents and young people is an issue of ongoing global concern. According to the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), adolescents represent a growing share of PLWH worldwide (44), and even though AIDS-related deaths are declining among all other age groups, deaths among adolescents have increased over the past decade (44). This may be due to a generation of perinatally-HIV infected children who are now growing into adolescence, or the lack of knowledge about the disease and how it is transmitted.

School attendance is critical to the lives and development of adolescents, including those living with HIV (45). Public day and boarding schools are the two common forms of academic settings for adolescents in many countries, including Ghana (46). In those environments, teachers, school staff, and peers become their main community and source of support as daily contact with families and caregivers is limited (47). However, this very environment poses challenges to adolescents living with HIV as most of their peers and staff are ignorant about HIV and thus, engage in stigmatizing behaviors. Such behaviors make it difficult for adolescents living with HIV to disclose their HIV status, take their medications, or even access health care facilities compared to their counterparts who attend day schools, as policies in boarding schools restrict independence and control access to healthcare facilities and external providers. These circumstances serve as barriers to accessing daily antiretroviral treatment (ART), cause self and experienced stigma, and provide limited privacy and confidentiality. A qualitative study from Kisumu, Kenya reported that the fear of stigma prevented HIV status disclosure to school staff among adolescents living with HIV and led to higher rates of disengagement from care.

The stigma associated with HIV also has been shown to be associated with specific psychological challenges such as depression and anxiety for young people living with HIV, as well as decreased self-esteem (48). These psychological experiences have been associated with increased rates of sexual and substance use risk behaviors (49), as well as decreased adherence to ART, and medical appointments. Given the range of negative psychosocial and medical outcomes that adolescents and young adults living with HIV experience due to HIV-related stigma, it is important to equip this population with skills to combat negative societal influences. It is also important to educate adolescents, schoolteachers, and staff, and to get schools to provide school-based support for adolescents living with HIV so they can optimize their health and wellbeing.

4.3.3. Limitation of the study

A limitation of the study is the fact that data was collected from only one administrative region of Ghana. As a result, findings cannot be generalized to the entire population of Ghana. This is a limitation because some other regions like the Northern and Upper administrative regions of Ghana are more rural and have a completely different cultural and social context with regards to HIV-related stigma compared to the Ashanti region. Irrespective of this, the data collected represents the voice and perspectives of PLWH and HIV-related stigma in the Ashanti region. Another limitation of the study is the fact that we did not examine the relationship between religion and HIV-related stigma seeing that some of the shaming and blaming behaviors mentioned in the paper appear to emanate from religious worldviews.

5. Conclusion

Eliminating HIV-related stigma is an important and necessary contribution to the global fight against HIV. To address HIV-related stigma in Ghana so as to increase HIV testing uptake, disclosure of HIV status, adherence to treatment, and to improve upon the quality of life of PLWH, it is important for countries, including Ghana, to focus on PLWH and to engage them in determining strategies for HIV stigma reduction at several levels simultaneously. This is because, interventions targeted at potential sources of HIV-related stigma have a greater probability of success.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

EA-M wrote the draft manuscript, did the qualitative data analysis, univariate analysis, finalized, and edited the manuscript. EO wrote a portion of the draft manuscript and edited the manuscript. EM performed the statistical analysis (bivariate and multivariate). TA-P edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We thank Emmanuel Baafi for helping with data collection at the Suntreso Government Hospital.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. World Health Organization. HIV/AIDS (2023). Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/hiv-aids#tab=tab_1 (Accessed February 17, 2023).

2. World Health Organization. HIV (2022). Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hiv-aids (Accessed February 17, 2023).

3. Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS. Global HIV & AIDS statistics- fact sheet (2021). Available at: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet (Accessed February 17, 2023).

4. Adam A, Fusheini A, Ayanore MA, Amuna A, Agbozo F, Kugbey N, et al. HIV stigma and status disclosure in three municipalities in Ghana. Ann Glob Health. (2021) 87(1):49. doi: 10.5334/aogh.3120

5. International Monetary Fund. Six charts show the challenges faced by sub-Saharan Africa (2021). Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2021/04/12/na041521-six-charts-show-the-challenges-faced-by-sub-saharan-africa (Accessed February 17, 2023).

6. Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS. Fact sheet—latest global and regional statistics on the status of the AIDS epidemic (2022). Available at: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2022/UNAIDS_FactSheet (Accessed February 17, 2023).

7. Ghana AIDS Commission. National and subnational HIV and AIDS estimates and projections 2020 report (2020). (Accessed February 17, 2023).

8. MDG Monitor. Millennium development goals (n.d.). Available at: https://www.mdgmonitor.org/millennium-development-goals/#:∼:text=MDG%208%3A%20Develop%20a%20Global%20Partnership%20for%20Development&text=To%20further%20develop%20an%20open,States%20and%20landlocked%20developing%20countries (Accessed February 17, 2023).

9. United Nations. The 17 goals (n.d.). Available at: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (Accessed February 17, 2023).

10. Armstrong-Mensah EA, Tetteh AK, Ofori E, Ekhosuehi O. Voluntary counseling and testing, antiretroviral therapy access, and HIV-related stigma: global progress and challenges. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19(11):6597. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19116597

11. The World Book of Facts. Ghana (2023). Available at: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/ghana/#government (Accessed February 17, 2023).

12. The Permanent Mission of Ghana to the United Nations. Map and regions of Ghana (n.d.). Available at: https://www.ghanamissionun.org/map-regions-in-ghana/ (Accessed February 17, 2023).

13. Ghana AIDS Commission. National HIV & AIDS strategic plan 2021–2025 (2020). Available at: https://www.ghanaids.gov.gh/mcadmin/Uploads/GAC%20NSP%202021-2025%20Final%20PDF(4).pdf (Accessed February 17, 2023).

14. Mosley C, Ofori E, Andrews C, Armstrong-Mensah E. Individual and community level factors related to HIV diagnosis, treatment, and stigma in Kumasi, Ghana: a field report. Int J Transl Med Res Public Health. (2022) 6(1):1–6. doi: 10.21106/ijtmrph.396

15. Ulasi CI, Preko PO, Baidoo JA, Bayard B, Ehiri JE, Jolly CM, et al. HIV/AIDS-related stigma in Kumasi, Ghana. Health Place. (2009) 15(1):255–62. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.05.006

16. Campbell C, Nair Y, Maimane S, Nicholson J. ‘Dying twice’: a multi-level model of the roots of AIDS stigma in two South African communities. J Health Psychol. (2007) 12(3):403–16. doi: 10.1177/1359105307076229

17. Rankin WW, Brennan S, Schell E, Laviwa J, Rankin SH. The stigma of being HIV-positive in Africa. PLoS Med. (2005) 2(8):e247. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020247

18. Greeff M, Phetlhu R, Makoae LN, Dlamini PS, Holzemer WL, Naidoo JR, et al. Disclosure of HIV status: experiences and perceptions of persons living with HIV/AIDS and nurses involved in their care in Africa. Qual Health Res. (2008) 18(3):311–24. doi: 10.1177/1049732307311118

19. The POLICY Project. Siyam’Kela: HIV/AIDS stigma indicators. A tool for measuring the progress of HIV/AIDS stigma mitigation (n.d.). Available at: https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNACX529.pdf (Accessed February 17, 2023).

20. Miller AN, Rubin DL. Factors leading to self-disclosure of a positive HIV diagnosis in Nairobi, Kenya: people living with HIV/AIDS in the sub-Sahara. Qual Health Res. (2007) 17(5):586–98. doi: 10.1177/1049732307301498

21. Simbayi LC, Kalichman S, Strebel A, Cloetea A, Hendaa N, Mqeketo A. Internalized stigma, discrimination, and depression among men and women living with HIV/AIDS in Cape Town, South Africa. Soc Sci Med. (2007) 64(9):1823–31. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.01.006

22. Wood K, Lambert H. Coded talk, scripted omissions: the micropolitics of AIDS talk in South Africa. Med Anthropol Q. (2008) 22(3):213–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1387.2008.00023.x

23. Kerr J, Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Nelson LE, Turan JM, Frye V, Matthews DW, et al. Addressing intersectional stigma in programs focused on ending the HIV epidemic. Am J Public Health. (2022) 112(S4):S362–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306657

24. Cooper B. Intersectionality. In: Disch L, Hawkesworth M, Disch L, Hawkesworth M, editors. The Oxford handbook of feminist theory. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press (2016). p. 385–406.

25. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV stigma and discrimination (2021). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/hiv-stigma/index.html#:∼:text=The%20lack%20of%20information%20and%20awareness%20combined%20with,judgements%20about%20people%20who%20are%20living%20with%20HIV (Accessed February 17, 2023).

26. Tenkorang EY, Owusu AY. Examining HIV-related stigma and discrimination in Ghana: what are the major contributors? Sex Health. (2013) 10(3):253–62. doi: 10.1071/SH12153

27. DiversityInc Staff. HIV/AIDS stigma and lack of knowledge is common among millennials and gen z, survey shows (2019). Available at: https://www.diversityinc.com/hiv-aids-stigma-and-lack-of-knowledge-is-common-among-millenials-gen-z-survey-shows-2/ (Accessed February 17, 2023).

28. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV by age: knowledge of status (2022). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/age/status-knowledge.html (Accessed August 16, 2023).

29. Wilder T. Understanding U = U can improve health outcomes for people living with HIV—but the message matters (2020). Available at: https://www.thebodypro.com/article/u-equals-u-health-outcomes-hiv-david-hardy (Accessed February 17, 2023).

30. Golin C, Isasi F, Bontempi JB, Eng E. Secret pills: HIV-positive patients’ experiences taking antiretroviral therapy in North Carolina. AIDS Educ Prev. (2002) 14(4):318–29. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.5.318.23870

31. Newman J, Iriondo-Perez J, Hemingway-Foday , Freeman A, Akam W, Balimba A, et al. Older adults accessing HIV care and treatment adherence in the IeDEA Central African cohort. AIDS Res Treat. (2012) 2012:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2012/725713

32. Brañas F, Berenguer J, Sánchez-Conde M, López-Bernaldo de Quirós JC, Miralles P, Cosín J, et al. The eldest of older adults living with HIV: response and adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy. Am J Med. (2008) 121(9):820–4. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.05.027

33. Pindani M, Nkondo M, Maluwa A, Muheriwa S. Stigma and discrimination against people living with HIV and AIDS in Malawi. World J AIDS. (2014) 4:123–32. doi: 10.4236/wja.2014.42016

34. Ghana Statistical Service, Ghana Health Service Accra, ICF international. Ghana demographic and health survey 2014 (2015). Available at: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/fr307/fr307.pdf (Accessed February 18, 2023).

35. Manijsin T, Sangyos D, Pirom P. Families and communities living with AIDS, ban haed district, Khon Kaen province, Thailand. Khon kaen. Sirinthorn Hospital. (2003):1–13.

36. Hua J, Emrick CB, Golin CE, Liu K, Pan J, Wang M, et al. HIV and stigma in Liuzhou, China. AIDS Behav. (2014) 18(Suppl 2):S203–11. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0637-3

37. Surkan PJ, Mukherjee JS, Williams DR, Eustachec E, Louisc E, Jean-Paulc T, et al. Perceived discrimination and stigma toward children affected by HIV/AIDS and their HIV-positive caregivers in central Haiti. AIDS Care. (2010) 22(7):803–15. doi: 10.1080/09540120903443392

38. Amo-Adjei J, Darteh EKM. Drivers of young people’s attitudes towards HIV/AIDS stigma and discrimination: evidence from Ghana. Afr J Reprod Health. (2013) 17(4):51–9.24689316

39. Brown L, Trujillo L, Macintyre K. Interventions to reduce HIV stigma: what have we learned? AIDS Educ Prev. (2003) 15(1):49–69. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.1.49.23844

40. Olalekan AW, Akintunde AR, Olatunji MV. Perception of societal stigma and discrimination towards people living with HIV/AIDS in Lagos, Nigeria: a qualitative study. Mater Sociomed. (2014) 26(3):191–4. doi: 10.5455/msm.2014.26.191-194

41. James P, Hayfron-Benjamine A, Abdulai M, Lasim O, Yvonne N, Obiri-Yeboah D. Predictors of HIV stigma among health workers in the Cape Coast Metropolis, Ghana. J Public Health Afr. (2020) 11(1):1020. doi: 10.4081/jphia.2020.1020

42. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Agenda for zero discrimination in health-care settings (2017). Available at: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2017ZeroDiscriminationHealthCare.pdf (Accessed February 17, 2023).

43. Holzemer WL, Makoae LN, Greeff M, Dlamini PS, Kohi TW, Chirwa ML, et al. Measuring HIV stigma for PLHAs and nurses over time in five African countries. Sahara J. (2009) 6(2):76–82. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2009.9724933

44. United Nations Children’s Fund. HIV and AIDS in adolescents (2021). Available at: https://data.unicef.org/topic/hiv-aids/ (Accessed February 17, 2023).

45. Roeaser RW, Eccles JS, Sameroff AJ. School as a context of early adolescents’ academic and social-emotional development: a summary of research findings. Elem Sch J. (2000) 100(5):443–71. doi: 10.1086/499650

46. Kose J, Lenz C, Akuno J, Kiiru F, Odionyi JJ, Otieno-Masaba R, et al. Supporting adolescents living with HIV within boarding schools in Kenya. PLoS One. (2021) 16(12):e0260278. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0260278

47. Michielsen K, Beauclair R, Delva W, Roelens K, Van Rossem R, Temmerman M. Effectiveness of a peer-led HIV prevention in secondary schools in Rwanda: results from a non-randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. (2012) 12(729):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-729

48. Andrinopoulos K, Clum G, Murphy DA, Harper G, Perez L, Xu J, et al. Health related quality of life and psychosocial correlates among HIV-infected adolescent and young adult women in the US. AIDS Educ Prev. (2011) 23(4):367–81. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.4.367

Keywords: HIV, HIV-related stigma, people living with HIV, HIV destigmatization, Ghana

Citation: Armstrong-Mensah E, Ofori E, Alema-Mensah E and Agyarko-Poku T (2023) HIV destigmatization: perspectives of people living with HIV in the Kumasi Metropolis in Ghana. Front. Reprod. Health 5:1169216. doi: 10.3389/frph.2023.1169216

Received: 19 February 2023; Accepted: 7 September 2023;

Published: 20 September 2023.

Edited by:

Bolaji Egbewale, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, NigeriaReviewed by:

Arshad Altaf, WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, EgyptFarah Shroff, Harvard University, United States

© 2023 Armstrong-Mensah, Ofori, Alema-Mensah and Agyarko-Poku. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Elizabeth Armstrong-Mensah ZWFybXN0cm9uZ21lbnNhaEBnc3UuZWR1

Elizabeth Armstrong-Mensah

Elizabeth Armstrong-Mensah Emmanuel Ofori2

Emmanuel Ofori2 Ernest Alema-Mensah

Ernest Alema-Mensah Thomas Agyarko-Poku

Thomas Agyarko-Poku