- 1School of Social Work, The University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL, United States

- 2New York State Psychiatric Institute, Columbia University, New York, NY, United States

- 3Department of Sociology, Anthropology, and Social Work, Auburn University at Montgomery, Montgomery, AL, United States

- 4College of Community Health Sciences, The University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL, United States

Introduction

Despite repeated calls to action (1), rates of HIV transmission and intimate partner violence (IPV) among low-income, cisgender Black women in the Deep South states of Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas consistently eclipse national averages and disproportionately outpace levels identified among all other women. This high risk group also remains left behind by U.S.’ HIV and IPV research and prevention efforts. They are also projected to be among the most significantly impacted by the recent Supreme Court’s decision to disband Roe v. Wade (2). In view of these risks, and known associations between HIV, IPV, and a lack of access to reproductive services (3), this Opinion serves as an immediate call to action.

In 2019, 8 of 10 U.S. states and 9 out of 10 U.S. metropolitan areas with the highest rates of new HIV diagnoses were in the South, with Deep South states heavily represented among them (4). As many as 9 out of every 10 new HIV cases among women occur in this highly vulnerable group (versus 6 out of 10 cases nationally) (5). In addition, although women are more likely to be tested than men, 90% of new HIV transmissions among women in Deep South states like Alabama and Mississippi (6) are attributed to sexual encounters with male sexual partners, as compared with 77% found elsewhere in the South (4). Disproportionately concentrated among Black women in the Deep South, these higher rates are consistent with earlier findings identifying lower rates of condom negotiation (7) and higher relationship power asymmetries (8). They also consistent with rates of IPV identified in the Deep South that exceed the national average by 12% or higher (9, 10). Yet, there are currently no HIV/IPV prevention interventions that center Deep South specific social and structural factors.

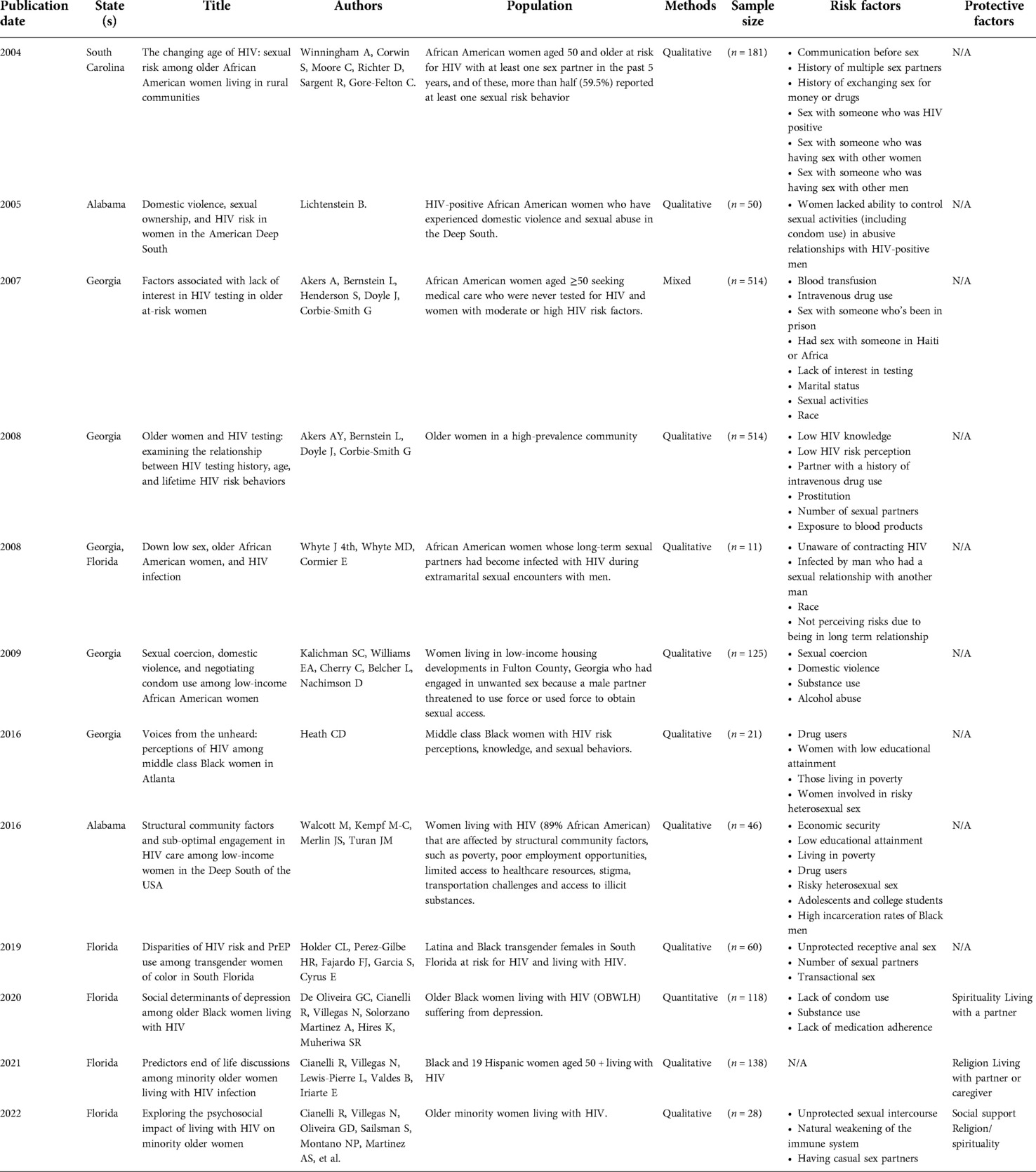

As reflected in Table 1, a narrative literature review of scholarly articles examining “HIV” and “violence” among “Black” or “African American” women in the U.S. reveals that only 12 (or 7%) of a total of 169 articles focused on Black women residing in the Deep South. Of this number, a mere six were written in the past 10 years and none expressly examined the critical intersection of HIV and “intimate partner violence”. In addition, of the 26 of HIV prevention interventions currently in the Centers for Disease Control’s compendium of evidence-based interventions (11), three (or approximately 10%) emanated from the Deep South (12–14). Although one of these emphasized the importance of “sociocultural” and “structural” risks (12), none specifically targeted IPV and/or region-specific differences. While we readily acknowledge these important scholarly contributions, the authors of this Opinion draw attention to these gaps and argue that failing to address them will continue to curtail efforts to end these co-occurring endemics.

The high cost of inaction

The costs associated with this continued neglect are sobering and anticipated to see sharp inclines. Although individuals in the Deep South make up only 29% of the total U.S. population, in 2019 alone, 47% of deaths in the U.S. attributed to HIV were concentrated in this region of the country. In addition, despite recent encouraging declines in the rate of new HIV diagnoses across the U.S. due to treatment advances such as PrEP and PEP, this decrease is markedly slower in the Deep South due in part to concentrated social and structural barriers endemic to this region of the U.S. (15).

The projected increase in HIV and IPV attributed directly to the recent retrenchment in sexual and reproductive services is of particular concern in the Deep South states given what scholars have also characterized as HIV and IPV risks specific to and/or exacerbated by residing in this region of the country. Although significantly understudied, these “Deep South-specific” or “Deep South-exacerbated” risks are noted to include (1) among the highest levels of (16) conservatism (e.g., religious, political, patriarchal gender-role) in the U.S. (17); (2) heavily concentrated poverty that eclipses rates found in developing nations and elsewhere in the U.S. (18); (3) health, behavioral health, Wi-Fi, and transportation deserts (19); and (4) disabling self, faith-based, interpersonal, systemic, and community stigma (20). Not enough is known however regarding how these region-specific and/or region-exacerbated factors may combine in a syndemic-like manner and/or may mediate individual and/or interpersonal risks. Syndemics is defined as two or more inextricable epidemics that work synergistically to significantly impact the overall health status of a population (21). In addition to increasing the risk for adverse outcomes, for a true syndemic to exist, these linked epidemics must also amplify each other, leading to worsening outcomes. Perhaps the most well documented syndemic is the SAVA syndemic which posits that poor HIV/AIDS outcomes are highly correlated with substance misuse and IPV among impoverished populations (22). A handful of HIV and IPV studies have also drawn attention to the importance of examining social, structural and cultural risks (alongside extreme poverty) (23, 24). None to date however, have examined Deep South-specific drivers of syndemic outcomes. This gap may be attributed to the lack of large-scale quantitative studies that examine HIV/IPV risk co-occurrence among Black women in this region of the U.S. These gaps notwithstanding, a direct causal link (25) and bidirectional associations (26) has been identified between HIV and IPV. Scholars have also identified salient differences in forms of HIV risks (e.g., engaging in casual and survival sex versus having concurrent sex partners) and IPV Black women experience based on the geographical location, culture, and norms (27). However, how factors may separately or together mediate HIV/IPV remains unclear.

Significant gaps also remain regarding possible syndemic-like protections unique to and/or amplified by living in the Deep South, such as faith and southern culture, despite literature pointing to the incredible saliency of both in the lives of Black women in the South (28, 29). Instead, HIV and IPV prevention literature has been disproportionately deficit in focus and region-specific protective factors remain vastly under-explored. As also denoted in Table 1, of the 12 articles identified in the narrative review, three examined population-specific protective factors (e.g., “living with partner or caregiver, social support, religion”). None however examined how factors heavily concentrated in the region may operate structurally to provide protection from transmission. This, despite the fact that the church remains one of the strongest and widely utilized sources of support for individuals, Black or otherwise, residing throughout the Deep South and faith-based organizations have served as critical partners in delivering social services, health-related, and prevention interventions (28). Scholars have also pointed to a “culture of honor” in the Deep South characterized by strong levels of gender roles and family cohesion (30). These highly patriarchal roles that characterize systemic approaches in this area of the country may further dissuade women’s help-seeking efforts (31). Little to no research exists however regarding if and how this concept impacts the lives of low-income cisgender Black women in the Deep South through social and structural mechanisms.

Fundamental to improving this research is including Black women in the Deep South in the research process. Community-partnered approaches employed throughout the continuum of the research process is a proven mechanism for increasing participation among traditionally excluded, understudied and underrepresented populations (32). Unlike community-based research where power differentials between the academic research community may erode trust, community partnered approaches rely upon shared power which often translates into higher rates of participation among underserved communities (32). Even so, opportunities to engage low-income Black women in the Deep South as full health equity partners in mapping Deep South specific HIV/IPV risks and protections remain woefully underleveraged.

Discussion

To close these critical gaps in HIV and IPV prevention research and interventions, and counter anticipated increases stemming from Roe vs. Wade, we recommend that urgent consideration be given to the following:

Health equity partnerships with Black women

Black women residing in the Deep South should be involved in deciding what research and praxis is needed, conceptualizing and framing research questions, determining the theoretical lens and potential interventions. Instead, they have at times been categorized as especially difficult to reach and engage (33) and are distrustful of the medical system and/or evidence-based interventions (34). Without equitable sharing of power and voice in all phases of research and intervention design, it is likely that these efforts, should they be prioritized, will replicate existing deficit-based scholarship and interventions. This gap in engaging Black women in the Deep South as health equity partners stands in contrast to the U.S.’ Ending the HIV Epidemic (EHE) strategic priorities. Among other key strategies set forth by the U.S.’ Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Office of Infectious Disease and HIV/AIDS Policy is a commitment to “plan(ning), design(ing), and deliver(ing) HIV prevention and care services” that are fully reflective of the needs of localities (35), the absence of which may result in a continued “stall(ing) of progress” in eliminating new HIV diagnoses.

Syndemic explorations: Structural risks and protections

Additional quantitative and multi-methods studies are also needed to advance the understanding of how risks and/or protections may combine “syndemically” to drive or mitigate risks. We recommend that every consideration be given to how region-specific social and structural differences may combine with individual and interpersonal factors to increase or decrease adverse outcomes. Deep South faith and culture have yet to be fully understood or leveraged. It is essential that we understand how they may uniquely impact risks (both positively and negatively) from the vantage point of low-income Black women in the Deep South, and how they should and should not be leveraged. Advancing research in this regard is consistent with models and frameworks such as the social ecological model of prevention (36) and social determinants of health (37), that acknowledges the critical role social and structural dimensions of risk (and resilience) may have on health outcomes. Despite literature that points to the determinative role that “place” plays in health and behavioral health outcomes (38), and overall well-being, to date none currently model region-specific dimensions of risks and resilience.

Exploration of implementation science implications

Lastly, alongside efforts to better understand the impact of Deep South-specific social and structural risks on HIV and IPV outcomes, we recommend that research be conducted regarding what impact these region-specific risks may have on efforts to implement and scale prevention interventions. A growing number of implementation science frameworks such as the Health Equity Implementation Framework (HEIF) (39) suggest that “societal” and “sociopolitical” domains are determinative of implementation science outcomes. Through the lens of HEIF, a critical next step is to examine if and how Deep South specific risks and protections such as “stigma”, “conservatism”, “faith” and “culture” may permeate organizations, faith-based or otherwise. By extension, it will also be important to examine if and how the organization itself (e.g., formal and informal policies, procedures, and culture) and/or organizational personnel in highly conservative and stigmatized social, political, and cultural environments may intentionally or unintentionally work to undermine HIV and IPV implementation efforts.

Author contributions

KJ served as primary author. SB, AS, and CC contributed significantly to the literature review, annotated outline, and prepared sections of the paper. All other authors provided critical review and edited extensively. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

BW’s research is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32MH096724. KJ's work is supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant No. P30MH062294. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Black women in the Deep South who have generously shared their stories as well as the tireless scholarly contributions of Deep South researchers and practitioners to date.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Wyatt GE, Davis C. The paradigm shift-the impact of HIV/AIDS on black women and families: speaking truth to power. Ethn Dis. (2020) 30(2):241–6. doi: 10.18865/ed.30.2.241

2. Sun N. Overturning roe v wade: reproducing injustice. Br Med J. (2022) 377:o1588. doi: 10.1136/bmj.o1588

3. The Lancet HIV. Anything but pro-life. Lancet HIV. (2022) 9(8):e521. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(22)00202-8

4. State of the HIV epidemic. Gileadhiv.com. Available at: https://www.gileadhiv.com/landscape/state-of-epidemic/?utm_id=iw_sa_15442187202_127739511982&utm_medium=cpc&utm_term=prevalence+of+hiv+in+usa&gclid=Cj0KCQjw-pCVBhCFARIsAGMxhAdOxOrxxmPbIQAz6v9mhukeZcsv39ODIrEdjKZxxmPn-g857F8jBbEaAtYrEALw_wcB&gclsrc=aw.ds (Accessed Jul 29, 2022).

5. Reif SS, Scholar R, Cooper H, Warren M, Wilson E. Southernaidscoalition.org (2021). Available at: https://southernaidscoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/HIVintheUSDeepSouth.pdf (Accessed Jul 29, 2022).

6. Mississippi. AIDSVu (2013). Available at: https://aidsvu.org/local-data/united-states/south/ (Accessed Jul 29, 2022).

7. Crosby RA, DiClemente RJ, Salazar LF, Wingood GM, McDermott-Sales J, Young AM, et al. Predictors of consistent condom use among young african American women. AIDS Behav. (2013) 17(3):865–71. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9998-7

8. Lichtenstein B. Domestic violence, sexual ownership, and HIV risk in women in the American Deep South. Soc Sci Med. (2005) 60(4):701–14. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.021

9. National Coalition Against Domestic Violence. Domestic violence in Alabama (2020). Available at: https://www.ncadv.org/files/Alabama.pdf

10. NCADV. Ncadv.org. Available at: https://ncadv.org/state-by-state (Accessed Jul 30, 2022).

11. Compendium. Cdc.gov. 2022. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/research/interventionresearch/compendium/index.html (Accessed Jul 29, 2022).

12. DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Rose ES, Sales JM, Lang DL, Caliendo AM, et al. Efficacy of sexually transmitted disease/human immunodeficiency virus sexual risk-reduction intervention for african American adolescent females seeking sexual health services: a randomized controlled trial: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. (2009) 163(12):1112–21. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.205

13. Diallo DD, Moore TW, Ngalame PM, White LD, Herbst JH, Painter TM. Efficacy of a single-session HIV prevention intervention for black women: a group randomized controlled trial. AIDS Behav. (2010) 14(3):518–29. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9672-5

14. DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Harrington KF, Lang DL, Davies SL, Hook EW 3rd, et al., Efficacy of an HIV prevention intervention for african American adolescent girls: a randomized controlled trial: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. (2004) 292(2):171–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.2.171

15. Elopre L, Kudroff K, Westfall AO, Overton ET, Mugavero MJ. Brief report: the right people, right places, and right practices: disparities in PrEP access among african American men, women, and MSM in the Deep South: the right people, right places, and right practices. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. (2017) 74(1):56–9. doi: 10.1097/qai.0000000000001165

16. Maxwell A, Shields T. The long southern strategy: How chasing white voters in the south changed American politics. New York: Oxford University Press (2019). online edn, Oxford Academic, (22 Aug. 2019), doi: 10.1093/oso/9780190265960.001.0001

17. Schaffer SD, Cotter PR, Tucker RB. Racism or conservatism: explaining rising republicanism in the deep South. Politics & Policy. (2000) 28:133–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-1346.2000.tb00570.x

18. Prison Policy Initiative. The parallel epidemics of incarceration & HIV in the Deep South. Prisonpolicy.org. Available at: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2017/09/08/hiv_men/ (Accessed Jul 29, 2022).

19. A look at rural hospital closures and implications for access to care: three case studies - issue brief. KFF (2016). Available at: https://www.kff.org/report-section/a-look-at-rural-hospital-closures-and-implications-for-access-to-care-three-case-studies-issue-brief/ (Accessed Jul 29, 2022).

20. Reif S, Safley D, McAllaster C, Wilson E, Whetten K. State of HIV in the US Deep South. J Community Health. (2017) 42(5):844–53. doi: 10.1007/s10900-017-0325-8

21. Singer M, Bulled N, Ostrach B, Mendenhall E. Syndemics and the biosocial conception of health. Lancet. (2017) 389(10072):941–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30003-X

22. Singer M. A dose of drugs, a touch of violence, a case of AIDS: conceptualizing the sava syndemic. FICS. (2000) 28(1):13–24.

23. Singer MC, Erickson PI, Badiane L, Diaz R, Ortiz D, Abraham T, et al. Syndemics, sex and the city: understanding sexually transmitted diseases in social and cultural context. Soc Sci Med. (2006) 63(8):2010–21. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.05.012

24. Wendlandt R, Salazar LF, Mijares A, Pitts N. Gender-based violence and HIV risk among african American women: a qualitative study. J HIV AIDS Soc Serv. (2016) 15(1):83–98. doi: 10.1080/15381501.2015.1074975

25. Decker MR, Seage GR 3rd, Hemenway D, Raj A, Saggurti N, Balaiah D, et al. Intimate partner violence functions as both a risk marker and risk factor for women’s HIV infection: findings from Indian husband-wife dyads. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51(5):593–600. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a255d6

26. Kouyoumdjian FG, Findlay N, Schwandt M, Calzavara LM. A systematic review of the relationships between intimate partner violence and HIV/AIDS. PLoS One. (2013) 8(11):e81044. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081044

27. Stockman JK, Lucea MB, Draughon JE, Sabri B, Anderson JC, Bertrand D, et al. Intimate partner violence and HIV risk factors among african-American and african-Caribbean women in clinic-based settings. AIDS Care. (2013) 25(4):472–80. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.722602

28. Nunn A, Jeffries WL 4th, Foster P, McCoy K, Sutten-Coats C, Willie TC, et al. Reducing the african American HIV disease burden in the Deep South: addressing the role of faith and spirituality. AIDS Behav. (2019) 23(Suppl 3):319–30. doi: 10.1007/s10461-019-02631-4

29. Baumeister RF, Vohs KD. Encyclopedia of social psychology. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications (2007).

30. Dietrich DM, Schuett JM. Culture of honor and attitudes toward intimate partner violence in latinos. SAGE Open. (2013) 3(2):215824401348968. doi: 10.1177/2158244013489685

31. Waller BY, Harris J, Quinn CR. Caught in the crossroad: an intersectional examination of african American women intimate partner violence survivors’ help seeking. Trauma Violence Abuse. (2022) 23(4):1235–48. doi: 10.1177/1524838021991303

32. Jones L, Wells K. Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research. Jama. (2007) 297(4):407–10.17244838

33. Sharpe TT, Lee LM, Nakashima AK, Elam-Evans LD, Fleming PL. Crack cocaine use and adherence to antiretroviral treatment among HIV-infected black women. J Community Health. (2004) 29:117–27. doi: 10.1023/B:JOHE.0000016716.99847.9b

34. Highfield L, Bartholomew LK, Hartman MA, Ford MM, Balihe P. Grounding evidence-based approaches to cancer prevention in the community: a case study of mammography barriers in underserved african American women. Health Promot Pract. (2014) 15(6):904–14. doi: 10.1177/1524839914534685

35. Overview. Hiv.gov. 2022. Available at: https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/ending-the-hiv-epidemic/overview (Accessed Jul 29, 2022).

36. The social-ecological model: a framework for prevention. Cdc.gov. 2022. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/about/social-ecologicalmodel.html (Accessed Jul 30, 2022).

37. Social Determinants of Health. Health.gov. Available at: https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health (Accessed Jul 30, 2022).

38. Dale SK, Ayala G, Logie CH, Bowleg L. Addressing HIV-related intersectional stigma and discrimination to improve public health outcomes: an AJPH supplement. Am J Public Health. (2022) 112(S4):S335–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2022.306738

Keywords: Black women, Deep South, HIV, intimate partner violence, syndemic risk, syndemic protection

Citation: Johnson KA, Binion S, Waller B, Sutton A, Wilkes S, Payne-Foster P and Carlson C (2022) Left behind in the U.S.’ Deep South: Addressing critical gaps in HIV and intimate partner violence prevention efforts targeting Black women. Front. Reprod. Health 4:1008788. doi: 10.3389/frph.2022.1008788

Received: 1 August 2022; Accepted: 26 October 2022;

Published: 25 November 2022.

Edited by:

Elizabeth Bukusi, Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI), KenyaReviewed by:

Glenna Tinney, Consultant, Alexandria, VA, United States© 2022 Johnson, Binion, Waller, Sutton, Wilkes, Payne-Foster and Carlson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Karen A. Johnson a2pvaG5zb24zOEB1YS5lZHU=

Specialty Section: This article was submitted to HIV and STIs, a section of the journal Frontiers in Reproductive Health

Karen A. Johnson

Karen A. Johnson Stefanie Binion

Stefanie Binion Bernadine Waller2

Bernadine Waller2 Amber Sutton

Amber Sutton Pamela Payne-Foster

Pamela Payne-Foster Catherine Carlson

Catherine Carlson