- 1Department of Occupational Therapy, Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, PA, United States

- 2Department of Communication Science and Disorders, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States

Objective: The study explores caregiver perceptions of home programs for clients with acquired brain injury based on current clinical care after transition to the community.

Design: A qualitative descriptive study.

Setting: Within the community, post inpatient rehabilitation.

Participants: A convenience sample of eight caregivers of clients with acquired brain injury from one clinical site. All participants spoke English, were between the ages of 18 and 85 years, had no neurodegenerative disorders, and self-identified as caregivers.

Procedures: Two nested semi-structured interviews were completed post-discharge from an inpatient rehabilitation facility. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed. Qualitative data analysis was performed utilizing MAXQDA© software, consensus coding, and abstraction of themes.

Results: Two themes with subsequent subthemes were identified: (1) Systems, Roles, and Responsibilities Influenced Caregivers' Perceptions of Home Program and Recovery Outlook and (2) Caregivers' Home Program Experience. The first theme addresses topics of caregiver roles and responsibilities, system supports and barriers, and their general outlook on recovery. Within the second theme, results provide a chronological description of home program training, use, and modification.

Conclusions: A caregiver’s outlook on the care receiver’s recovery and home program implementation is influenced by the burden of responsibilities, and system-level supports and barriers. The home program experience of the caregivers was reported to involve limited but satisfactory training. Caregivers saw the value in home programs and advised others to engage in them. Future programs should encourage healthcare providers to provide explicit instruction to the caregiver about their intrinsic value to home program implementation and adherence.

Introduction

As a leading cause of disability worldwide, an acquired brain injury (ABI) impacts the person who experiences the injury, and also the family around the individual, limiting engagement in meaningful activities and decreasing health-related quality of life for both the individual with ABI and the caregiver (1–4). To decrease this impact and maximize recovery potential, rehabilitation is typically recommended immediately post-injury (5, 6). However, persons with ABI continue to have limitations in returning to desired daily activities in part due to limited access to direct services. Investigation of the perspectives of clinicians and ABI survivors on service provision during post-discharge rehabilitation identified the need for improved quality of care in continuity of care, accessibility, information, and communication (7). It is common during usual care for rehabilitation therapists to extend services and support the continuation of rehabilitation through the assignment of home practice programs following discharge from inpatient rehabilitation (8–10).

Home practice programs in usual care are individualized therapeutic tools which outline exercises and activities to be completed unsupervised at home to support recovery (11–13). One factor that can substantially limit the potential impact of home programs is adherence to the prescribed program. Adherence has been reported as a challenge for persons with ABI as they often struggle to follow through with these home programs post-discharge from inpatient rehabilitation due to a variety of factors such as lack of equipment, decreased motivation, and fatigue (11).1

While the barriers persons post-ABI face are diverse, one factor that has been identified to support adherence to rehabilitation home programs is the perception of social support.1 In addition to being associated with self-reported adherence, occupational therapists and speech-language pathologists both identified the importance of another individual or support person as a factor that can influence home program adherence for persons post-stroke (9, 10). Although therapists and clients indicate that caregivers are important, only a few studies that were associated with randomized controlled trials explored the caregivers’ experiences with home programs as a part of recovery for persons post-ABI. Engaging in home programs as a dyad (i.e., caregiver and care receiver) has allowed the caregiver to experience increased preparation for discharge, and foster individualized tailoring of the home program (14). Furthermore, decreased caregiver burden was found when a dyadic home program for people with traumatic brain injury was tailored, individualized, and provided assigned responsibilities and carryover within the dyadic team (15).

While these sources emphasize caregiver involvement during home programs, our study seeks to explore caregivers’ perceptions of the value of home programs based on their personal experience and participation within them during usual care and outside of a controlled study environment. Additional information is warranted that represents if or how the experience changes over time as well as the experience across different care settings. This information can be leveraged by clinicians to inform their practice and by researchers looking to advance dyadic home-practice interventions. Therefore, the research question was how do caregivers of persons with acquired brain injury describe their experience with rehabilitation home programs provided during usual care?

Methods

Design

Utilizing a pragmatic paradigm, we intentionally selected a qualitative descriptive approach to obtain first-hand narratives and explore the experiences of caregivers in the training and implementation of home programs for clients with ABI (16, 17). This approach has been identified as an appropriate method when seeking perspectives on the experiences of services or programs. We choose this approach to provide an initial description of the caregivers’ experience with minimal interpretation given that the experience of usual care home programs has not been previously described. Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research were utilized to ensure transparency and appropriate synthesizing of caregiver reporting (18). This study was approved by the researchers’ institutions [IRB Protocol Duquesne University 2022/08/16, University of Pittsburgh 22010148]. Respondents gave written consent before starting interviews.

The research team consisted of two occupational therapists, one speech-language pathologist, and two occupational therapy students. All authors were centralized in an academic setting located in an urban area of Northeastern United States. All therapists had clinical experience working with persons with acquired brain injury and their caregivers. A shared assumption of the research team was that caregivers are critical to ABI recovery and that they frequently face challenges post-discharge from rehabilitation. In addition, we believed caregivers’ experiences and involvement with home programs would be highly variable.

Participants

We utilized a criterion convenience sample to ensure that we sampled individuals who could best answer our research question. For inclusion in the study, participants had to personally identify as a caregiver for an individual with acquired brain injury who had received a rehabilitation home program and had to be between 18 and 85 years old. There were no requirements on the consent form defining the caregiver role, only self-identification. In addition, participants needed to speak English as their primary language. Participants were excluded if they self-reported a progressive neurological condition such as dementia or Parkinson's disease. We used two criteria to determine the sample size: (1) the number of participants we were able to recruit and (2) saturation. Saturation was determined during data analysis as no new codes or categories were identified.

Procedures

Participants were recruited from a local rehabilitation hospital during or after their care recipient's stay. Potential participants were identified by therapists and only approached by the research team with the potential participant's permission. The rehabilitation hospital's standard practice included prescribing a home program before discharge; however, there were no consistent elements included within the home program and they were created based on the therapist's discretion. Before the interviews, participants completed an electronic consent form. Then, the initial interview was completed through a phone (n = 7) or video call (n = 1) between one to two months after discharge from the hospital. Two to three months later, participants completed the closing interview to identify any changes since the first interview. Changes reported by caregivers related to home programs, roles, and responsibilities occur over time (1, 3), thus it was important to consider both time points. All interviews were audio-recorded using computer technology via Zoom call (14 interviews) or QuickTime recorder (one interview).

Materials

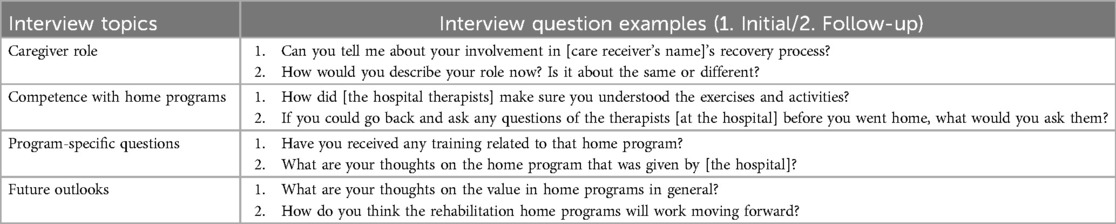

We used a research team-developed semi-structured interview guide to complete both sets of interviews. The topics were selected based on the researchers’ previous experience with the topic and knowledge of current literature on home programs and caregivers. The topics covered in the first interview guide included topics focused on home program training received, current participation in the home program, and outlook on the use of the home program. The second interview guide covered topics related to their role in the program at this new point in time, any changes related to the program, and revisited the topic of outlook on the home program. The guides were consistent during the study. Sample questions from the interview guides are in Table 1.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using inductive content analysis after all eight participants completed their interviews (19). Transcripts were imported into MAXQDA© for analysis. The team independently completed open coding of the first two participants’ initial interviews. The team then compared initial codes and generated an initial consensus codebook. A second comparison of codes occurred and any updates to the coding structure were made with consensus. This process of independent coding and team consensus was repeated for all the initial interviews. When the team moved to the second interview, the consensus codebook was again updated. Two research team members (EDB, KS) completed the abstraction of themes from the coded data. This process involved grouping similar codes into larger categories and then identifying the two main themes with corresponding subthemes.

Trustworthiness

Several methods were implemented to support the project trustworthiness (20). To ensure credibility and confirmability, before the analysis began each investigator engaged in a reflexivity activity to examine assumptions, beliefs, and judgments about caregivers and home programs. We also triangulated by analyst through individual coding followed by group consensus aimed to minimize the bias of any single analyst but also allow for a diversity of perspectives. Additionally, for confirmability, we completed member checking. A summary of the results was shared with four of the eight participants and they were asked for feedback. If something was reported to be missing, the analysis was checked to see if it was included in the larger picture. No revisions were made based on member checking. We have also provided information on the sample and the selection criteria used to allow others to consider the transferability of findings. Last, utilizing the MAXQDA© software allowed for an audit trail to be kept through the different file iterations as well as the merging of codes during abstraction supporting the study's dependability.

Results

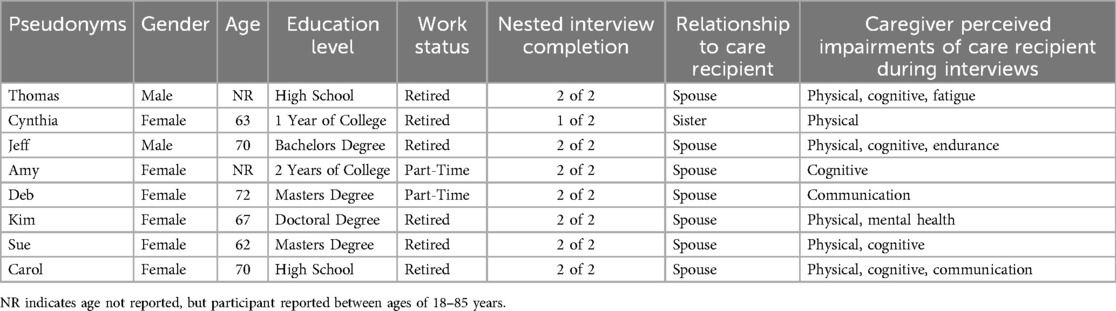

A total of 8 caregivers of clients with acquired brain injury were interviewed, including two males (25%) and six females (75%). All participants identified as white. Seven out of eight participants (88%) participated in both interviews. Seven participants were spouses of an individual with ABI. The average interview length was 20 min. Additional participant demographics including education, work status, and caregivers’ reported impairments of their care receiver resulting from the ABI are in Table 2.

The two key themes that captured the data were: (a) Roles, Responsibilities, and Systems Influenced Caregivers’ Perceptions of Recovery Outlook and (b) Caregivers’ Home Program Experience.

Roles, responsibilities, and systems influenced caregivers’ perceptions of recovery outlook

The first theme reflected the factors that caregivers reported impacting their lives after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation that were not directly connected to home programs but that influenced their experience during their care receivers’ recovery. These factors included the following subthemes (1) caregiver roles and responsibilities, (2) system supports and barriers, and (3) perceived impairments and recovery outlook.

Caregiver roles and responsibilities

Multiple participants indicated that their roles and responsibilities as a caregiver increased upon discharge home to maintain care, home maintenance, and finances. Carol said, “There's just so much more I do for him now that he used to do himself…around the house or whatever”. Kim similarly reported, “He wouldn't be able to be home if I wasn't here.” Deb noted finance needs, “It was thrust upon me to figure out all the finances.” Thomas spoke to the sudden nature of this responsibility, “This was like a curveball that came out of nowhere.” Collectively these comments illustrate how caregivers experienced increased responsibilities that, at times, felt overwhelming after a family member's brain injury. Caregiver perceptions were also influenced by the caregiver and care receiver's previous roles prior to the injury, the caregiver's availability, and previous experience with health care. Seven of the eight caregivers spoke to the significant role change because their care receiver was independent with all daily activities and/or working before the recently acquired brain injury. Only Jeff stated that his role did not change too much because his care receiver had medical concerns prior to the recent ABI.

System supports and barriers

Caregivers described multiple ways that they were supported by the current or previous medical team. Kim stated, “The in-home [therapists] were all extremely helpful…sometimes saying okay so you’re having trouble getting out of bed lets walk back to bed or find a better way to do this.” Deb stated, “I'm very grateful that we have… this physical therapist as well as speech coming here to you know give these tips and pointers and make sure he's doing what he's supposed to be doing”. Caregivers also indicated systemic barriers compound the burden of new roles and responsibilities they were navigating. Thomas stated, “I tried to get more [therapy] in home, but the system doesn't want to pay for the services.” Jeff stated, “I think if they would have looked at her whole situation and there were decisions that were made that could have been made differently that would have made her safer in the environment that she was going into.” Deb also revealed difficulties with system navigation, “I never knew about private insurance. And then on top of the bills, it's like the short-term disability, the long-term disability, and the stuff insurances need.”

Perceived impairment and outlook on recovery

In addition to more responsibilities, prior experiences, systematic supports, and barriers caregivers reported on their perception of their care receiver's impairments and overall recovery. Five out of the eight participants noted impairments in more than one area that remained post-discharge from the hospital (See Table 2). During interview one, three participants expressed mixed opinions of recovery often with recognition that there was room for improvement. Deb stated, “He's come such a long way. but he has a ways to go.” Two participants expressed negative perceptions of recovery. For example, Carol stated, “To be honest, I'm not seeing any big improvement”. However, Kim was optimistic about recovery during the first interview stating, “He's been good and it's getting better each day.” During the second interview, the outlook had improved for most of the participants (n = 5) reporting improvement. Sue stated, “I was pleasantly surprised at how his cognition has now come back, not 100% but 85%.” However, some participants continued to have a mixed or negative outlook during the second interview Carol stated, “There hasn't been much improvement”. Similarly, Jeff noted in the second interview, “I'm going to have to take her to the doctors because she's having some like memory lapses … I think she really needs to be reevaluated in some capacity.”

Caregivers’ home program experience

The second theme focused on the description of the home program experience from the caregiver's perspective. This included subthemes of (1) caregiver home program training, (2) content and environment for home program use, (3) caregiver support of home programs, (4) facilitators and barriers, (5) future home program use, and (6) value and advice.

Caregiver home program training

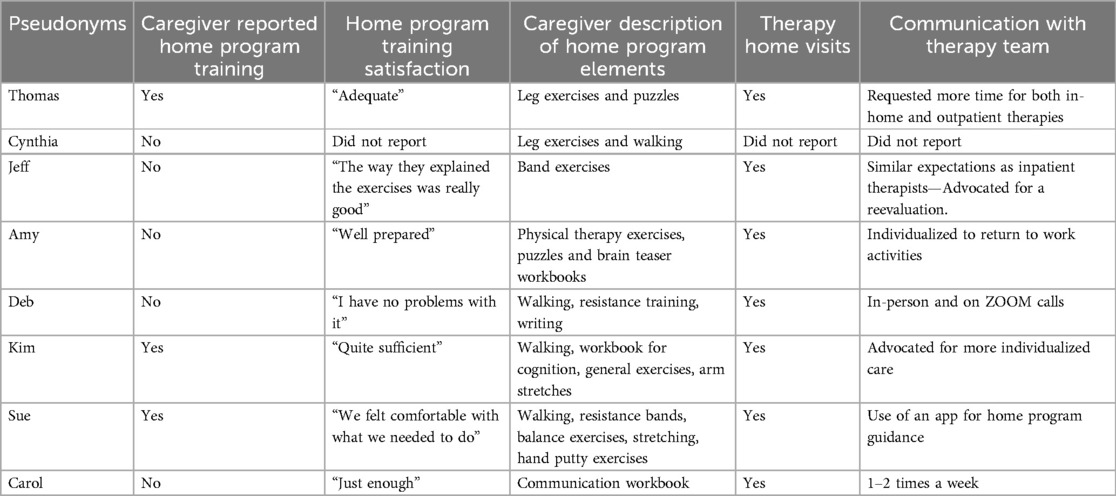

When describing their experience with home programs, caregivers were asked to begin by describing their experience with training on the home programs. Caregivers could often describe elements of training that occurred at the hospital that were non-specific to home programs. For example, Sue noted, “Yeah they also showed me you know like how he should get up and down from the bed, off the bed, into the car, how he should do that.” When redirected to discuss the home programs, many caregivers reported limited training. Cynthia reported that the amount of training was not adequate to ensure understanding. Amy noted, “I didn't really get much training at [hospital] it was kind of, I don't know, seemed a bit hurried when he was getting out of there.” It was also reported that what occurred was not perceived as training. Deb states “Um, I didn't really, she didn't really train me. I would not call it training.” Despite the limited nature of the training provided, participants reported satisfaction with the training. Thomas said, “Yeah, it was one day, but that was quite sufficient.” Some participants noted elements like handouts were supportive. See Table 3 for more reported training from each participant.

Content and environment for home program use

When asked about the home program's content, some participants noted that there was not much to them or their difficulty level was low and repetitive. For example, Carol reported, “He really wasn't given much of anything when he left there.” Cynthia noted her care receiver had been given “.. leg lifts and stuff like that, like moves, you know, side to side.. walking.” Caregivers in this sample did not report any difficulties with finding space, equipment, or working the home program into the daily routine. All of the caregivers indicated that they felt the home program had a feasible number of exercises and enough time to complete them. Some did qualify saying that they had enough time because they were retired. Most caregivers reported that equipment was provided to them by the healthcare system, however, one did mention that they had to personally pay for home equipment.

Caregiver support of home programs

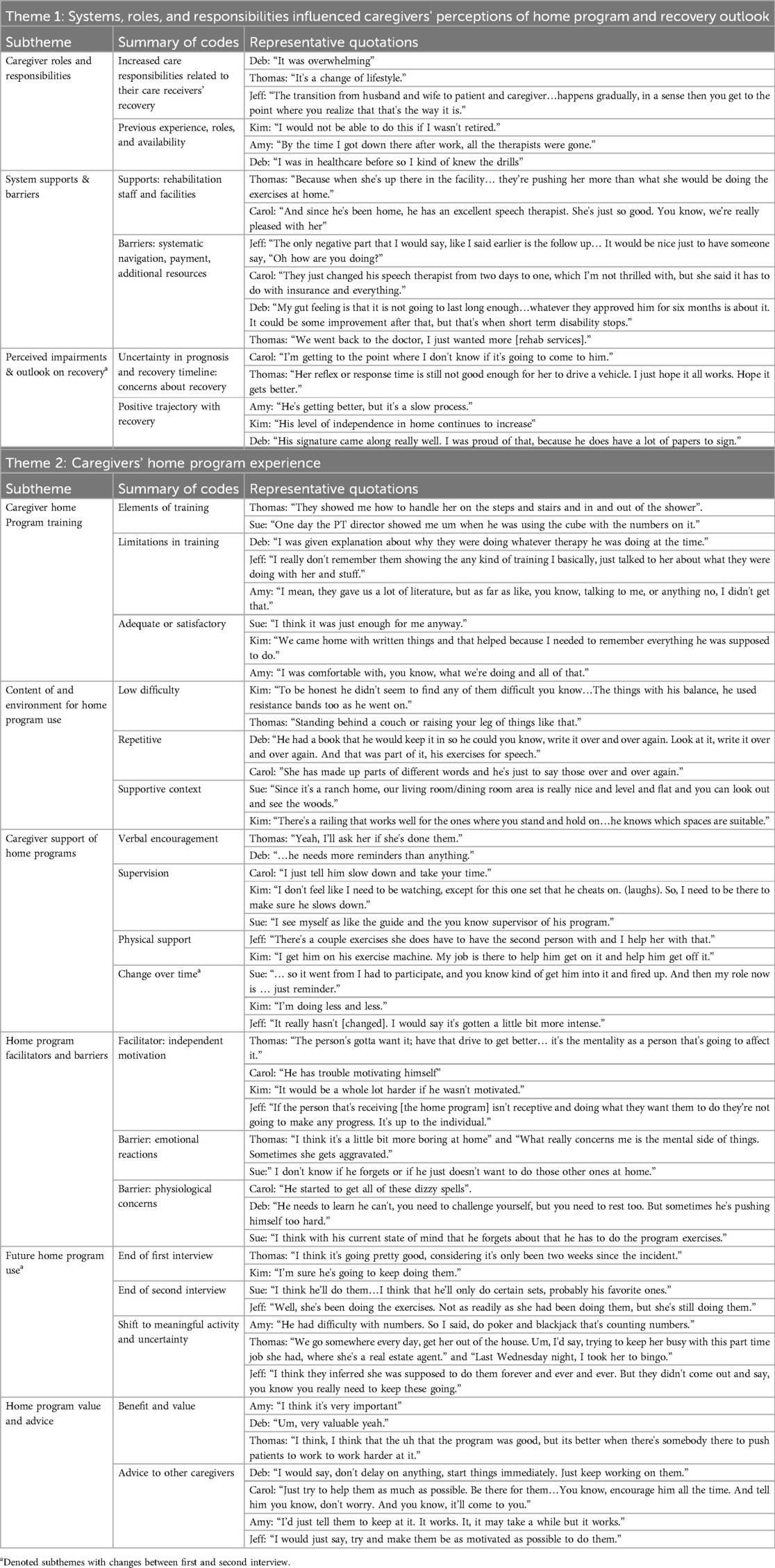

The most frequently reported method of support for home programs was through verbal encouragement. Verbal encouragement included caregivers providing reminders to complete the home programs and encouragement to complete the program. Cynthia stated “Oh, I always encouraged him. Tell him that you know it is for his own benefit.” Others reported providing more direct setup or supervision. Amy reported, “..I liked to make sure he sits for two hours a day and works in that book.” A few participants reported needing to be there to physically support the home program recommendations. Carol reported, “But now he needs me more and more because when he gets up to walk, I sort of have to go with him.” Three participants acknowledged a change in their role in home program support between the two interview time points. See Table 4 for examples.

Facilitators and barriers

In addition to the way they participated in the home program, caregivers also offered insight into the perceived facilitators and barriers around home program engagement by their care receivers. Caregivers perceived the independent motivation of the care receiver as a primary facilitator of home program success. Participants Amy, Deb, Kim, and Sue all indicated that they thought their care receiver was motivated and that helped with the follow-up of their home programs (Table 4). Perceived home program barriers reported by caregivers were diverse. For example, some participants noted emotional reactions of frustration or boredom. Carol stated, “He just gives up because he's so frustrated.” Other caregivers mentioned physiological barriers limiting home program engagement. Jeff said, “She really doesn't have as much stamina as she used to.”

Future home program use

Caregivers were also asked about their outlook on the home programs moving forward at the end of each interview. At the end of the first interview, participants reported feeling capable of completing the home program and they would continue using it. During the second interview, more participants reported a shift in what was being done around home programs. For example, Carol reported a focus on activities from a specific discipline, “It's basically speech..like grade schoolbooks to help his phonics.. it's good practice for him.” Others reported a shift to engaging in activities in their daily lives more than the prescribed home program. Kim noted, “it's become a more natural part of life rather than let's stop and exercise.” See Table 4 for additional examples from the first and second interviews.

Value and advice

Last, caregivers reported on the value of home programs and offered specific advice to other caregivers about home programs. All participants found value in the use of the home programs. Kim reported “[Home programs] were really important even mentally for him to just have something to do.” When asked to provide advice to others who might be a caregiver for someone after a stroke and the use of home programs, participants focused on working to engage the clients in the programs immediately upon return home and providing encouragement. Sue said, “Do it the minute you get home, don't, don't let, don't let them get complacent by not doing them.” Other pieces of advice focused on the use of novel treatments like a hyperbaric chamber (Deb), the importance of a power of attorney (Deb), and supervision and safety (Thomas).

Discussion

This qualitative study describes the perceptions of caregivers whose care receiver post-ABI was prescribed a home program as part of usual care before being discharged from inpatient rehabilitation. A caregiver's outlook on the person with ABI's recovery and home program implementation appears to be influenced by the presence of additional responsibilities, availability of the caregiver, and system-level supports and barriers. In addition, the caregiver's home program experience involved limited but satisfactory training, and home programs that were repetitive and easily done at home. Caregivers offered encouragement and occasional assistance if needed by their care receiver. Caregivers saw the value in home programs and advised other caregivers to support persons post-ABI in completing home programs.

The additional roles and responsibilities reported by caregivers often led to a need for additional support. Caregivers identified a desire for additional therapies, follow-up to care, and support navigating the healthcare system. The availability of the caregiver to support the client with ABI is also critical for successful discharge home and continued rehabilitation and recovery (21). Limitations in familial caregiver support can negatively impact long-term health outcomes for clients post-ABI. Several participants reported challenges navigating the system and a need for additional support which highlights the previously established need for the development of a standard care pathway to better support caregivers (22). Current usual care would benefit from continued development and study of evidence-based navigation support programs post discharge that are clear and easy to use for clients with ABI and their families (22). Providing additional support to navigate systematic barriers may allow caregivers to be more involved with home program implementation.

The second theme described the experience of home programs from the caregivers’ perspective and while caregivers endorsed the value of home programs, they often described them as separate from their other caregiver roles and responsibilities. Caregivers typically identified their role related to home programs as being an encourager of the person to participate rather than actively engaged in the program itself. Despite evidence supporting caregiver involvement increasing adherence (23, 24)1, often caregivers in this study instead focused on the person with ABI's individual motivation levels or need for additional rehabilitation professional support. While the individual motivation of the person with ABI has been identified by practitioners as a key moderator for home program implementation (9), individual motivation has the potential to be enhanced by the additional supports that a caregiver can provide during home programs (25). Therefore, therapists then should consider the use of dyad interventions as a means to support caregiver participation in home programs. Dyad interventions (26) actualize the engagement of both the caregiver and care receiver and could increase participation in home programs to support the health and well-being of both individuals. The active involvement of the caregiver in the home program plan is important as dyad intervention studies that intentionally engage the caregiver and care receiver in a shared goal or activity have demonstrated better outcomes than teaching caregivers to deliver home program exercises.2

Limitations of this study include only recruiting caregivers and sampling from a single clinical site for recruitment. Additionally, the experiences of the caregivers sampled within this study may not be reflective of other informal caregivers from different racial and socioeconomic backgrounds. All caregivers were either employed part-time or retired, therefore, this study does not reflect the experiences of informal familial caregivers who are working full-time or working in multiple role capacities, which may limit transferability. Future studies should diversify clinical settings for recruitment, as well as sample for the experiences of other familial caregivers such as children, friends, neighbors, or more distant relatives. Our study only recruited one caregiver from a non-spousal relationship so relationship diversity will be an important component of recruitment for future studies (27).

Several considerations and future directions for clinical practice and for research can be drawn from these results. For clinical practice, quality improvement initiatives are needed to help translate evidence of integrated and holistic dyad-focused education on home programs and the subsequent impact on adherence. Supporting caregivers as they navigate their novel roles and responsibilities should be a part of the caregiver training process, starting during hospital rehabilitation (22). Explicit instruction as a part of the home program training to the person's social support network about their intrinsic value to home program implementation is critical to support adherence.1 These instructions should take into account the caregiver's roles, relationship with care receiver, availability, and additional responsibilities. Our study focused exclusively on the caregiver experience during usual care, however future investigations could explore the dyadic experience. In addition to expanding the understanding of the home program experience, this would also allow for more detailed information to be gathered from the medical record of the person with an ABI.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study describes that the additional caregiver responsibilities and system-level supports and barriers may influence a caregiver's outlook on the care receiver's recovery. In addition, caregivers saw the value in home programs despite limited training and advised other caregivers to ensure engagement in home programs. Future initiatives should give pathways to healthcare providers to ensure explicit instruction to the caregiver about their intrinsic value to home program adherence.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Duquesne University Institutional Review Board and University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

ED: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KS: Formal Analysis, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SW: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. IB: Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EB: Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research of this article: This work was supported by the Encompass Health Corporation Grant 2021.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Donoso Brown EV, Wallace SE, Tichenor SE, Foundas B, Blemler R. Determining predictors of self-reported adherence to rehabilitation home programs for persons with acquired brain injury: a prospective observational study. NeuroRehabilitation.

2. ^Kringle EA, Kersey J, Kim GJ, Bhattacharjya S, Dionne TP, Farag M, et al. Dyad interventions for health-related quality of life, activity, and participation after stroke: a systematice review. Disabil Rehabil.

References

1. Ferriera da Costa T, Mariano Gomes T, Raquel de Carvalho Viana L, Pereira Martins K, Nêyla de Freitas Macêdo Costa K. Stroke: patient characteristics and quality of life of caregivers. Rev Bras Enferm. (2016) 69(5):877–83. doi: 10.1590/0034-7167-2015-0064

2. Klepo I, Sangster Jokic C, Trsinski D. The role of occupational participation for people with traumatic brain injury: a systematic review of the literature. Disabil Rehabil. (2022) 44(13):2988–3001. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2020.1858351

3. Powell JM, Wise EK, Brockway JA, Fraser R, Temkin N, Bell KR. Characteristics and concerns of caregivers of adults with traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. (2017) 32(1):E33–41. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000219

4. Williams S, Murray C. The experience of engaging in occupation following stroke: a qualitative meta-synthesis. Br J Occup Ther. (2013) 76(8):370–8. doi: 10.4276/030802213X13757040168351

5. Lam Wai Shun P, Swaine B, Bottari C. Combining scoping review and concept analysis methodologies to clarify the meaning of rehabilitation potential after acquired brain injury. Disabil Rehabil. (2022) 44(5):817–25. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2020.1779825

6. MacDonald SL, Linkewich E, Bayley M, Jeong IJ, Fang J, Fleet JL. The association between inpatient rehabilitation intensity and outcomes after stroke in Ontario, Canada. Int J Stroke. (2024) 19(4):431–41. doi: 10.1177/17474930231215005

7. Alhasani R, Radman D, Auger C, Lamontagne A, Ahmed S. Perspectives of clinicians and survivors on the continuity of service provision during rehabilitation after acquired brain injury. PLoS One. (2023) 18(4):e0284375. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0284375

8. Proffitt R. Home exercise programs for adults with nuerological injuries: a survey. Am J Occup Ther. (2016) 70(3):7003290020p1–p8. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2016.019729

9. Donoso Brown EV, Fichter R. Home programs for upper extremity recovery post-stroke: a survey of occupational therapy practitioners. Top Stroke Rehabil. (2017) 24(8):573–8. doi: 10.1080/10749357.2017.1366013

10. Donoso Brown E, Wallace S, Liu Q. Speech-language pathologists’ practice patterns when designing home practice programs for persons with aphasia: a survey. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. (2021) 30(6):2605–15. doi: 10.1044/2021_AJSLP-20-00372

11. Argent R, Daly A, Caulfield B. Patient involvement with home-based exercise programs: can connected health interventions influence adherence? JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. (2018) 6(3):e47. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.8518

12. Donoso Brown E, Nolfi D, Wallace SE, Eskander J, Hoffman JM. Home program practices for supporting and measuring adherence in post-stroke rehabilitation: a scoping review. Top Stroke Rehabil. (2020) 27(5):377–400. doi: 10.1080/10749357.2019.1707950

13. Lang CE, Birkenmeier RL. Upper-Extremity Task-specific training after Stroke or Disability: A Manual for Occupational Therapy and Physical Therapy. Bethesda: AOTA Press (2014).

14. Vloothuis J, Depla M, Hertogh C, Kwakkel G, van Wegen E. Experiences of patients with stroke and their caregives with caregiver-mediated exercises during the CARE4STROKE trial. Disabil Rehabil. (2020) 42(5):698–704. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2018.1507048

15. Moriarty H, Winter L, Robinson K, Piersol CV, Vause-Earland T, Iacovone DB, et al. A randomized controlled trial to evaluate the veterans’ in-home program for military veterans with traumatic brain injury and their families: report on impact for family members. Phys Med Rehabil. (2016) 8(6):495–509. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2015.10.008

16. Jewell DV. Guide to Evidence-based physical Therapist Practice. 2nd ed. United States: Jones & Bartlett Learning (2011).

17. Mei Y, Lin B, Zhang W, Yang D, Wang S, Zhang Z, et al. Benefits finding among Chinese family caregivers of stroke survivors: a qualitative descriptive study. Br Med J Open. (2020) 10:e038344. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038344

18. O'Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. (2014) 89(9):1245–51. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388

19. Vears DF, Gillam L. Inductive content analysis: a guide for beginning qualitative researchers. Focus Health Prof Educ Multi Prof J. (2022) 23(1):111–27. doi: 10.11157/fohpe.v23i1.544

20. Ahmed SK. The pillars of trustworthiness in qualitative research. J Med Surg Public Health. (2024) 2(100051):1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.glmedi.2024.100051

21. Bosch PR, Barr D, Roy I, Fabricant M, Mann A, Mangone E, et al. Association of caregiver availability and training with patient community discharge after stroke. Arch Rehabil Res Clin Transl. (2023) 5(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.arrct.2022.100251

22. Fowler K, Mayock P, Byrne E, Bennett K, Sexton E. “Coming home was a disaster, I didn’t know what was going to happen”: a qualitative study of survivors’ and family members’ experiences of navigating care post stroke. Disabil Rehabil. (2024) 46:1–13. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2024.2303368

23. Bhattacharjya S, Linares I, Langan J, Xu W, Subryan H, Cavuoto LA. Engaging in a home-based exercise program: a mixed-methods approach to identify motivators and barriers for individuals with stroke. Assist Technol. (2023) 35(6):487–96. doi: 10.1080/10400435.2022.2151663

24. Morris JH, MacGillivray S, MacFarlane S. Interventions to promote long-term participation in physical activity after stroke: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2014) 95(5):956–67. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.12.016

25. Galvin R, Stokes E, Cusack T. Family-mediated exercises (FAME): an exploration of participant’s involvement in a novel form of exercise delivery after stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil. (2014) 21(1):63–74. doi: 10.1310/tsr2101-63

26. Zhang Y, Qiu X, Jin Q, Ji C, Yuan P, Cui M, et al. Influencing factors of home exercise adherence in elderly patients with stroke: a multiperspective qualitative study. Front Psychiatry. (2023) 14:1157106. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1157106

Keywords: caregiver, acquired brain injury, home program, adherence, qualitative, usual care

Citation: Donoso Brown EV, Stepansky K, Wallace SE, Bien I and Buttino E (2025) Caregiver perceptions of usual care home programs for persons with acquired brain injury: a qualitative descriptive study. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 5:1490874. doi: 10.3389/fresc.2024.1490874

Received: 3 September 2024; Accepted: 18 December 2024;

Published: 15 January 2025.

Edited by:

Ann Van de Winckel, University of Minnesota Twin Cities, United StatesReviewed by:

Rachel M. Proffitt, University of Missouri, United StatesPeii Chen, Kessler Foundation, United States

Copyright: © 2025 Donoso Brown, Stepansky, Wallace, Bien and Buttino. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Elena V. Donoso Brown, ZG9ub3NvYnJvd25lQGR1cS5lZHU=

Elena V. Donoso Brown

Elena V. Donoso Brown Kasey Stepansky

Kasey Stepansky Sarah E. Wallace

Sarah E. Wallace Isabella Bien1

Isabella Bien1