- 1School of Kinesiology & Health Science, York University, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 2School of Physiotherapy, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada

- 3Department of Physical Therapy, College of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada

Background: Fall risk and incidence increase with age, creating significant physical and mental burden for the individual and their care provider. Lift assistive devices are used in multiple healthcare facilities, but are generally not portable nor self-operational, limiting their use outside of medical supervision. The Raymex™ lift is a novel lift assistance device within a rollator to address these limitations. We aim to gather user-centered feedback on the Raymex™ lift, set up instructions, safety protocols to improve feasibility and usability, and explore the potential usability as a fall recovery or prevention device.

Methods: Four older adults, two informal caregivers and 16 formal caregivers (clinicians and continuing care assistants) participated in a focus group. Participants provided feedback on the Raymex™ lift after viewing a demonstration and using the device. Qualitative and quantitative data were analysized using thematic and descriptive analysis respectively.

Results: Participants highlighted three major themes: (1) Design features requiring improvement, (2) Positive feedback and suggestions to optimize the Raymex™ lift and (3) Pricing vs. social utility. Participants suggested widening the seat, changing the braking button layout, and lowering the device weight to improve usability. Participants believed the main device feature was fall recovery and had implications for social utility by reducing the need for ambulance visits to the home. Price point led to a concern on affordability for older adults.

Conclusion: The feedback gained will advance the development of the Raymex™ lift and may highlight cost-effective design choices for other developers creating related aging assistive technologies.

1 Introduction

With aging, there is an increased falls risk due to age-related physical changes in balance and gait, neuromuscular changes in muscle mass, strength, and power, and changes in cognition (1, 2). The global prevalence of falls among older adults is significant, ranging from 26% to 35% overall and 32% to 42% for those aged 70 older, (3, 4) and costing $2 billion and $50 billion respectively, (5–7) with each fall costing $2,044 to $6,606 for those aged 65 years or older (8, 9). Non-fatal falls also contribute to ongoing healthcare costs, with ambulance visit costing at least $224 in the United States, and between $45 to $325 in Canada, depending on province (10–19). The reliance on emergency services for fall-related injuries further increases the burden on the caregiver both physically and mentally (20–23).

(5–7) Due to the large physical burden on caregivers, emergency response wait-times, and healthcare associated costs with lifting older adults after a fall, many companies have attempted solutions with fall assistance devices, for example The Hoyer elevate, (24) IndeeLift Human Floor Lift for Fall Recovery, (25) or Bellavita Dive Bath Lift (26). While some of these lifts have helped older adults from the floor level, there continues to be shortfalls including the lifts’ weight, requirement of an additional person to operate the device, low maximum seat height, and non-motorized seat height adjustment (24). To fill this gap, Axtion Independence Mobility Inc. has developed the Raymex™ lift (https://raymexlift.com), a mobility aid device with a similar structure to a rollator walker, but with the added feature of lift assistance and recovery up to a maximum weight of 300lbs (Figure 1).

The Raymex™ has a battery powered movable seat that can descend to floor level, rise to a height of 24” and stop anywhere in between. It can be operated by the older adult on the floor via a control panel on the bottom panel of the structure, while they are on the seat using the control panels on the handles, or by a caregiver via a control panel on the top of the frame. While scholarly literature supporting existing or similar lifts to the Raymex™ is limited, previous evidence has reported that physical demand is much higher in floor lifts compared to robotic-assisted transfer lifts, and users reported discomfort during use (27, 28).

After multiple design revisions including features and structural engineering, Axtion Independence Mobility Inc is approaching a market ready product (Class 1 Medical Devices) (29). Users feedback on the Raymex™ will enable final modifications to prepare the final market ready device. This mixed-method study has two objectives, to: (a) gather feedback on the Raymex™(V4), and users set up instructions and safety protocols from older adults’, informal caregivers’, formal caregivers’ (e.g., personal support workers), and clinicians’; and (b) explore the potential use of the Raymex™ as a fall recovery or prevention equipment.

2 Methods

A mixed-method descriptive study (30) was used to seek feedback from older adults, informal and formal caregivers about the comfort, usability, and design of the Raymex™. The qualitative and quantitative data were mixed within the result and discussion sections.

2.1 Ethical approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the Dalhousie University Health Science Research Ethics Board (REB: 2023-666).

2.2 Participants and sampling

Four participant groups were gathered using criterion-based purposive sampling (31): older adults residing in independent living or their own home; informal caregivers (e.g., family or friends); formal caregivers (e.g., paid personal support workers); and clinicians (physiotherapists, occupational therapists, and their assistants). Inclusion criteria for older adults were: aged 65+, self-reported recent fall or fall risk or fear of falling, lives alone or with someone, uses walking aid, speaks and understands English. Exclusion criteria included recent surgery (past six months) or injury on the lower limb, comorbidities preventing participation, and cognitive impairment preventing comprehension. Informal caregivers were eligible if they had provided at least two months of unpaid care to an older adult meeting the study's inclusion criteria while formal caregivers and clinicians have experience working (at least 6 months) with older adults that met the inclusion criteria. Sample size recommendations for feasibility mixed method descriptive study depend on the purpose of the study and the weight of the qualitative or quantitative components (32, 33). Our study does not aim to generalize our findings; hence we weigh the qualitative components higher and that guided our sample size. The sample size for qualitative description studies (34) has been based on data sufficiency or saturation—where no new theme emerges during interviews (35). Based on this, we estimated a sample size of 20 participants (five from each group) to allow for comprehensive feedback on the Raymex™, achieving data sufficiency or saturation.

2.3 Recruitment

Older adults and their family members were recruited from a healthcare organization offering independent living and home care services, while clinicians were recruited from a rehabilitation clinicians special interest group working in long-term care (LTC) in Nova Scotia. Recruitments involved study flyers on the independent living buildings' notice boards and in their weekly newsletters, and targeted emails to the special interest groups detailing research objective and researchers' contact information. Interested participants contacted the researchers, underwent screening and, if eligible, were invited to take part in a focus group discussion.

2.4 Data collection

Data were collected over three sessions, each lasting 2 h, from November 2023 to January 2024. The sessions were a mix of in-person and hybrid and were held separately for older adults/informal caregivers; physiotherapists, occupational therapists, and physical/occupational therapist assistants; and support care workers. At each session, a minimum of four researchers and one Raymex™ developer (product engineer or the chief executive officer) were present. During the focus group discussions, participants watched an in-person demonstration of the Raymex™. They practiced using the Raymex™ as guided by licensed physiotherapists. Participants were video recorded while they provided ongoing feedback during the practice sessions. Following the practice, participants completed the questionnaire and submitted their feedback on the user setup instructions manual and safety protocols. Participants who were unable to provide written feedback on the documents provided oral feedback. Each session ended with a focus group discussion guided by semi-structured questions focused on usability (e.g., ease to use), comfort, safety, perceived impact, and physical experience of this device (see Appendix 1 for the focus group guide). Field notes were taken by research assistants at each session and informed the context during data analysis. Audio data was recorded and transcribed using otter.ai (Otter.ai, Inc., Mountain View CA), an artificial intelligent transcription services, and was check for correctness by research assistants.

2.5 Data analysis

The qualitative data derived from transcripts and field notes were analyzed by the research team employing directed thematic content analysis (36) managed in NVivo 1.6.1 (Lumivero, Denver, CO). Four coders independently coded the data to identify major themes, including areas for improvement for the Raymex™. All coders met to merge their coding. De-identified videos were also analyzed using an open-coding principles to identify participant interactions and movements related to the practice of the Raymex™, including any practice problems not captured verbally in the focus groups. Themes derived from field notes, transcripts of focus group discussions, and video analyses were triangulated and discussed in meetings to address and resolve any differences in interpretation and/or coding.

Quantitative data, including demographic information and results from the survey, were managed in Microsoft Excel, and are presented in aggregated format. Descriptive statistics, such as frequency, percentages, mean, standard deviation, were used to describe the quantitative data.

2.6 Trustworthiness

We employed member checking by sending the study's findings to the participants to ensure that we captured all their feedback and ideas regarding the Raymex™ (37). We triangulated qualitative and quantitative survey data enhancing the credibility and kept an audit trail of the research process, ensuring transparency, and facilitating future verification. We kept reflective notes which described the Subjective I—those values, assumptions, and beliefs that a researcher brings to research. For instance, three authors are physiotherapists and they reflected on how their profession as physiotherapist would influence how the feedback provided by the participants were interpreted. To enhance the dependability of the study findings, multiple coders coded the transcripts and met to discuss the emerging themes.

3 Results

A total of 22 individuals participated in three focus groups. Four older adults participated, aged 73–85 years [mean (SD) = 79.25 (5.68 yrs)], two female and two males, had some education (e.g., a diploma and bachelor's degree), two lived alone in independent living buildings, and two resided at home or in assisted living with their caregivers, and three had a walking aid (either a rollator, a stick or both). Two informal caregivers participated who were aged 69 and 75 years old [mean (SD) = 72(4.24 yrs)], a male and a female, with bachelor's and high school education. Clinicians (eight physiotherapists, one occupational therapist, and four physiotherapy/occupational therapy assistants) and formal caregivers (three continuing care aides) included 12 females and four males, all full-time staff working in a LTC setting aged 27–64 years [mean (SD) = 44.08 (12.51 yrs)]. One physiotherapist did not report their age.

3.1 Themes

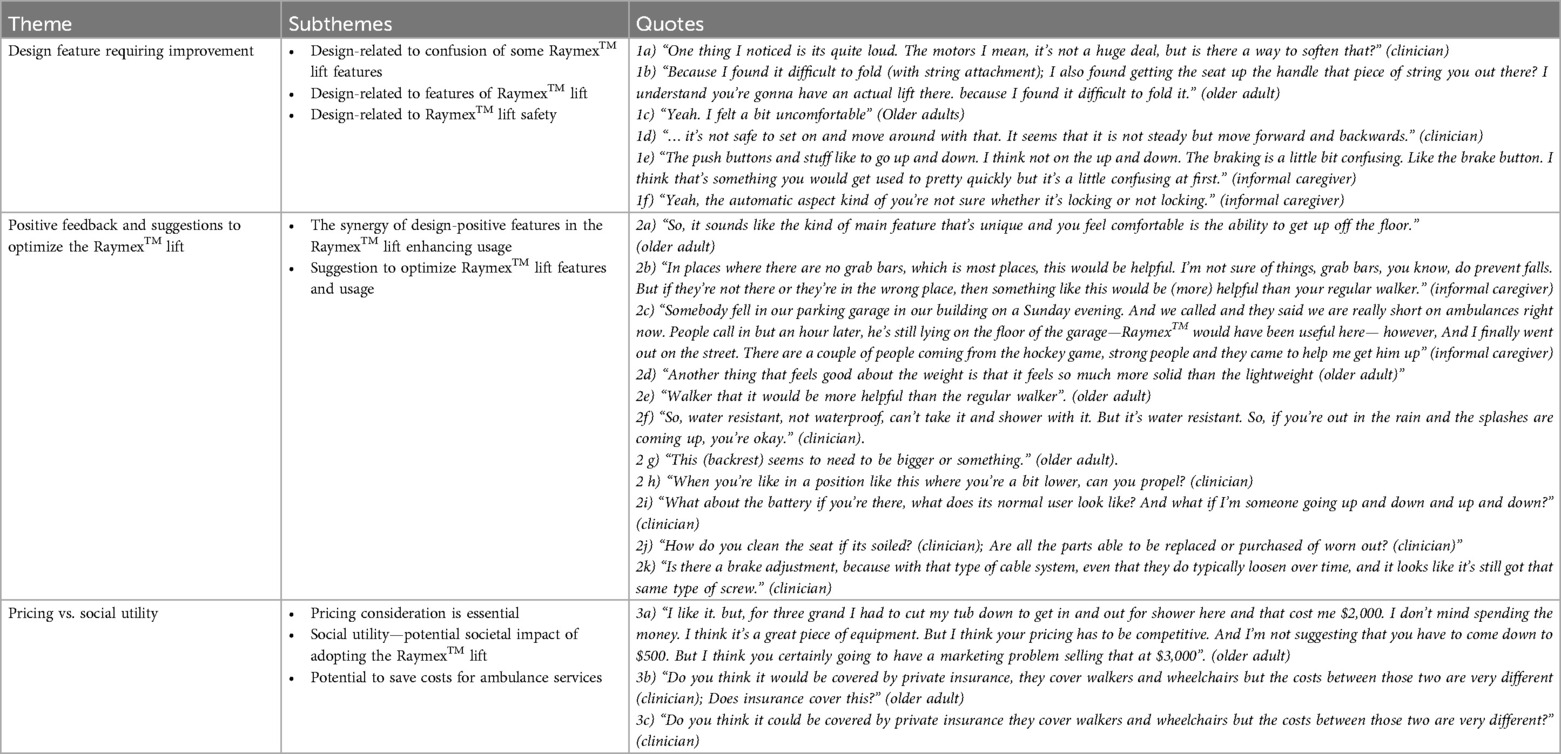

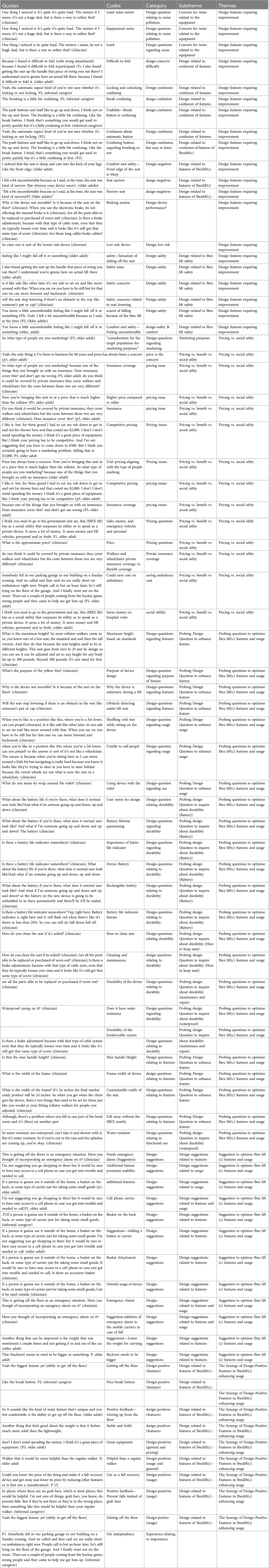

Three overarching themes with several subthemes emerged as feedback regarding the real-time use of the Raymex™ (Table 1): (a) Design feature requiring improvement; (b) Positive features and suggestions to optimize the Raymex™ features and usage; and (c) Pricing vs. social utility. Theme development is shown in Appendix 2.

3.1.1 Theme 1 – design feature requiring improvement

This theme highlights design-related elements requiring improvement, such as noise of the seat raising and lowering and safety. Our participants highlighted their concern regarding noise from the Raymex™ motor, especially if multiple older adults use it in the same home.

Another concern elucidated by our participants is the substantial weight of the Raymex™, which may impede its outdoor use, particularly for caregivers or older adults who may be frail. Participants expressed varying perceptions of the use of the Raymex™ across different environments: 87% found it useful in their current residence, 82% for home care services and 68% the Raymex™ in LTC settings, but only 52% found it useful for community travel.

Both clinicians and older adults voiced safety concerns during the real-time use of the Raymex™ emphasizing the difference in stability when seated and in motion. Participants inquired about seat responsiveness to obstacles when lifting older adults and generally shared sentiments of discomfort and unease, underscoring the importance of heightened stability to prevent re-fall from the lift.

Participants also commented on the narrow width of the seat expressing concerns that it could limit the comfort and mobility of users with different body shapes. An older adult also expressed concern regarding the comfortability of the Raymex™ related to the edge of the seat pressing into the back of the legs. The participant was not alone in their concern as 3 participants (∼15%) reported the seat to be uncomfortable on the questionnaire.

The feedback from an informal caregiver revealed notable observations on the usability of the Raymex™, explicitly concerning the push buttons for ascending and descending. The caregiver highlighted initial confusion, particularly regarding the brake button, expressing the belief that familiarity would develop over time. However, this may have been an isolated incident as only one participant (∼5%) noted they did not like the raising/lowering button design. Another informal caregiver echoed this sentiment, emphasizing uncertainty regarding the automatic braking mechanism, indicating a potential challenge in discerning whether the mechanism is engaging the brakes. This was supported by three participants (∼15%) reporting they did not like the braking button design on the questionnaire. When probed to suggest ways to improve the button layout, three participants (∼15%) mentioned they would like the braking button to be separated into a unique locking and unlocking button, one participant (∼5%) suggested a longer light interval to indicate locking or unlocking the brakes, and one participant (∼5%) suggested to use different button shapes to indicate the locking/unlocking function for those with visual impairments. These insights underscore usability concerns, specifically about the confusing nature of the brake button and the automatic feature.

3.1.2 Theme 2: positive features and suggestions to optimise Raymex™

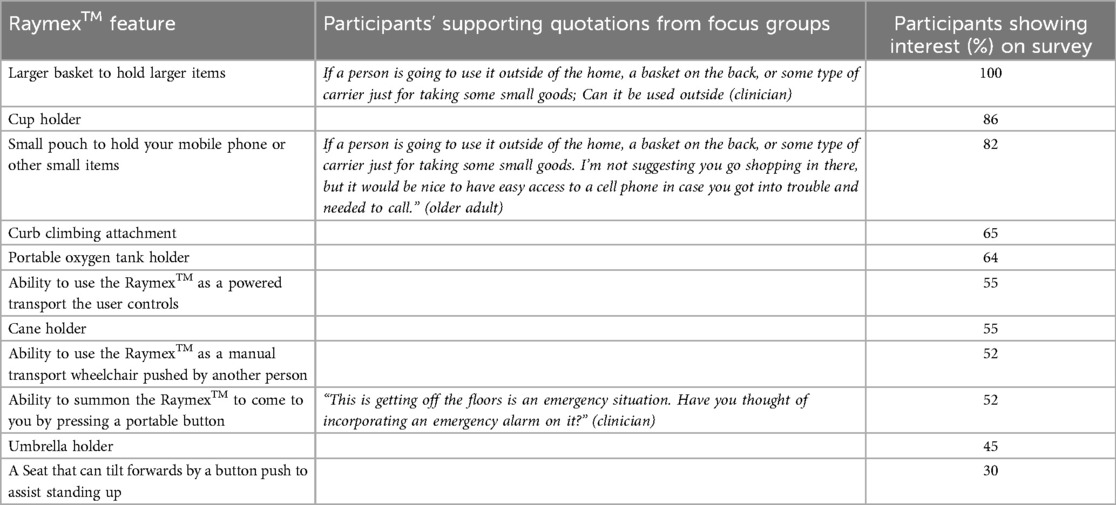

This theme encompasses a series of positive features and suggestions that would improve usage of the Raymex™. As highlighted by older adults, the Raymex™'s most significant feature is its unique and comfortable ability to facilitate getting up from the floor. The informal caregivers further emphasized the device's utility in locations without grab bars, noting its superior assistance to a regular walker. Participants further enumerated that these features promote usage, including its potential role in preventing falls, fall recovery, facilitating efficient assistance when needed (with or without a caregiver present), as well as offering a stable and solid support system. One informal caregiver provided a scenario where prompt assistance was required, and Raymex™ would have been helpful, highlighting the potential Raymex™ role in emergencies. On the questionnaire, participants expressed interest in additional features for the Raymex™. See Table 2 for the questionnaire results with quotes from the focus group supporting their suggestions.

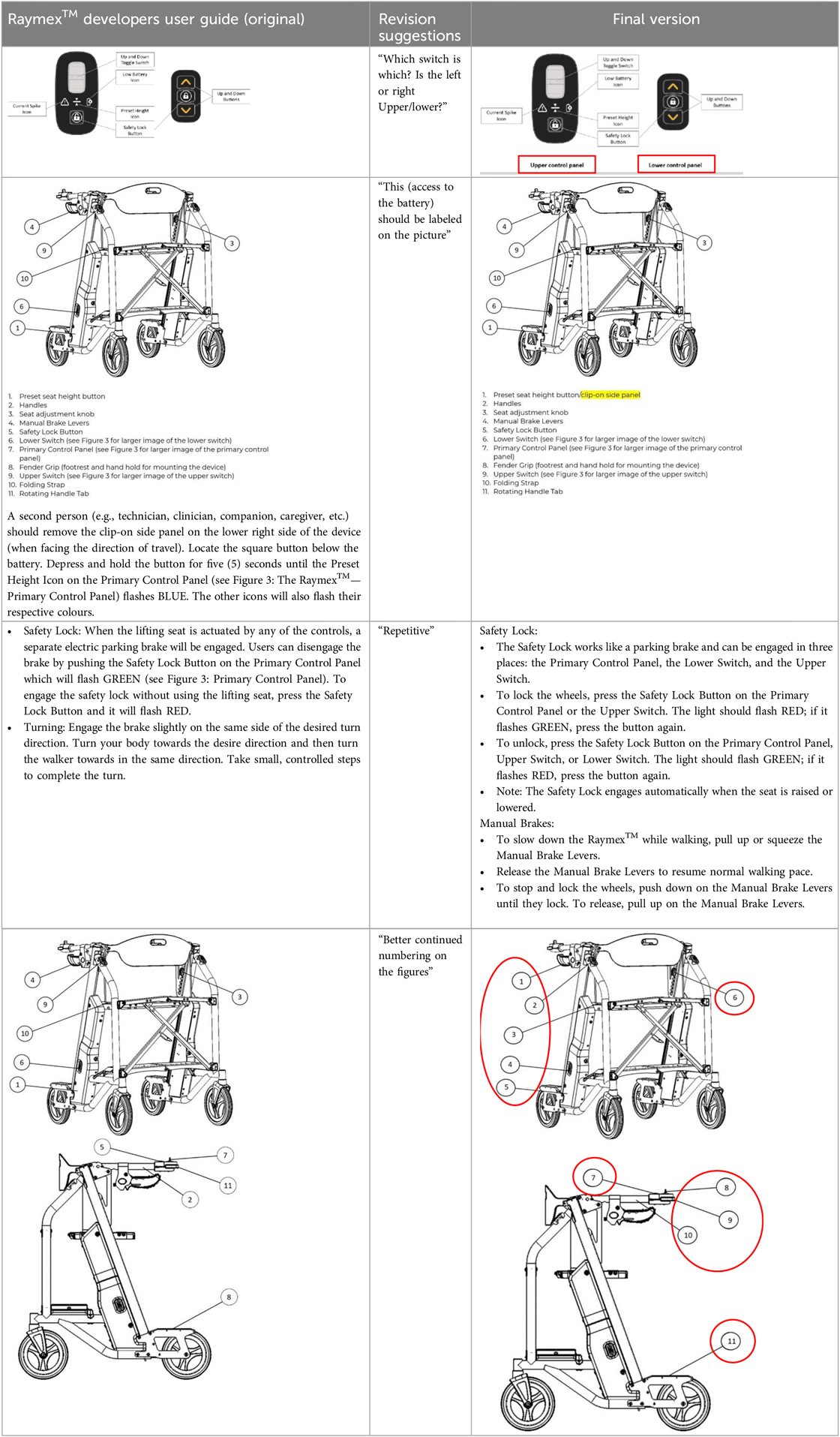

Participants provided feedback on potential situations the Raymex™ may be useful for, and feedback on design (see Table 3). Participants believed the Raymex™ would be useful for (1) retrieving items from a low level/ground (78%, n = 18), (2) transferring from/to a seat (78%, n = 18), car (74%, n = 17), bed (70%, n = 16), toilet (78%, n = 18), (3) standing close to the sink (87%, n = 20), (4) sitting at counter height (83%, n = 19), (5) walking inside (70%, n = 16) and outside (61%, n = 14) the house (6) independent (78%, n = 18) and assisted (91%, n = 21) fall recovery, and (7) as an exercise tool (78%, n = 18). During the focus groups, clinicians inquired about durability aspects such as waterproofing and maintenance and address practical concerns regarding battery usage/performance during frequent up and down movements. Clinicians raised concern about the Raymex™'s maneuverability in a lowered position, distinguishing it from a wheelchair. They also inquired about practical aspects such as cleaning the seat, parts replacement, and brake adjustments.

Table 3. Example of the Raymex™ developers user guide, the suggested revision, and the final version.

3.1.3 Theme 3 – pricing vs. social utility

Participants frequently discussed the idea of pricing vs. social utility in the focus group. Competitive pricing strategies were discussed, ensuring that unit pricing aligns with the targeted demographic. Despite concerns about pricing and insurance coverage, participants emphasized the social utility of the Raymex™, citing its potential ability to meet both personal and societal needs. Participants highlighted potential cost savings, not only in terms of competitive pricing but also in the context of emergency services and personal expenses, envisioning a scenario where the Raymex™ could potentially save costs on ambulance services and reduce expenditures associated with hospital visits. According to the participants, the lift's social utility would outweigh any potential pricing issues, emphasizing the need for the government to invest in subsidizing the price. Participants also raised questions about insurance coverage, drawing comparisons with coverage for walkers and wheelchairs.

4 Discussion

The Raymex™ is a portable personal lift, providing an enhanced alternative to a rollator walker, featuring an elevating seat capable of descending to floor level and ascending to a height of 24 inches, with the ability to stop at any chosen height. The Raymex™ lift distinguishes itself from other existing lifts, such as the Indeelift Human floor lift and the Bellavita Dive Bath Lift, (26) due to its portability and ascending height of 24 inches, as opposed to 21 inches and 18.89 inches, respectively. This design may be particularly appealing to older adults and their family members due to its self-operational nature that is not present in FGA-700 lift (38). This study explored the usability of version 4 of the Raymex™ among older adults, informal caregivers, and clinicians, to elicit specific feedback regarding use, features, and instructional manuals. Our participants highlighted that Raymex™'s multi-purpose use, including its ability to facilitate getting up from the floor, and adaptability in spaces where other large lifts or walkers may not be practical. In addition, our participants provided feedback regarding some of the features of the Raymex™, mainly on the confusion of the brake button and the seat width. The participants asked additional probing questions with suggestions to enhance Raymex™ features and discussed its potential for social utility and pricing considerations.

Participants—primarily older adults and informal caregivers—have proposed supplementary features, such as a basket for holding phones and decreasing the lift's weight to facilitate outdoor use. Such suggestions underscore a user-driven demand for improved functionality and adaptability in the device, (39) addressing the preferences of older adults with mobility limitations who seek versatile equipment for enhanced confidence and comfort outside their homes. The desire for weight reduction stems from recognizing that frail older adults or informal caregivers may face challenges lifting the Raymex™ in and out of a car. The reduction in weight of the Raymex™ has the potential to facilitate aging in place, (40, 41) preserving a sense of identity through independence and autonomy by enabling older adults and informal caregivers to conveniently transport the Raymex™ into the community for use and return home, mitigating the necessity for LTC as frailty increases.

Our participants shared experiences or concerns related to the affordability of the Raymex™, which was not surprising given the historical challenges associated with pricing considerations for innovative tools targeted at older adults (42). Previous work has reported the impact of pricing on adoption, focusing on affordability for market penetration, and accessibility for equitable and inclusive mobility aids (43, 44). Nevertheless, participants perceived the relationship between the pricing of the Raymex™ and the social utility as essential to improving the health and well-being of older adults/informal caregivers. Striking a balance between pricing and social utility is promising to support the desire of older adults to age at home and reduce ambulance-related costs for falls among older adults. Participants perceived that government adoption of the Raymex™ or developed policies to subsidize the cost could potentially lower current ambulance call expenses for recovery assistance, which range from $45 and $325 in Canada and the United States, respectively (17,18).

4.1 Limitations

While our study's strength is based on the real-time feedback of the Raymex™, there are some limitations. We have a relatively small sample of older adults and informal caregivers recruited from one healthcare organization in Nova Scotia resulting in feedback that may not be comprehensive and generalizable. In addition, we were not able to include all team members to provide feedback on the device such as nurses and geriatricians. Subsequently, future usability experience or input on the next version of the Raymex™ should incorporate a diverse population of older adults and clinicians. The presence of a product design engineer and the CEO of the company at the feedback sessions may have limited the negative feedback participants feel comfortable providing. Despite the limitations, feedback is essential for continuous improvement and enhancement of user-centred design and usability of novel devices like the Raymex™. Our results can be used by future developers of technologies to support aging in place and cost-effective design choices in early development. In our specific scenario, the Raymex™ developers will utilize these insights to formulate the final version of the Raymex™ for a pilot feasibility test, laying the groundwork for a conclusive trial to ascertain market readiness.

5 Conclusion

Our participants highlighted that the significant feature of the Raymex™ was its ability to lift older adults off the floor and act as a walker, and it can easily be adapted to different home settings. However, participants also highlighted improvement of some Raymex™ features, such as a narrow lift seat and button settings, which would enhance the lift's usability. Additional features were suggested, including reducing the weight of the lift to enable older adults and informal caregivers to use it outside the home. This comprehensive feedback not only provides valuable suggestions that can guide potential refinements and advancements in the Raymex™ design, but also emphasizes its potential to enhance mobility and safety of older adults. Our results can be used by future developers of technologies to support aging in place to support cost effective design choices in early development.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Dalhousie University Health Science Research Ethics Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MK: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft. AC: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. NA: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. MV: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. CM: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The authors declare that this study received funding from Invest Nova Scotia. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article, or the decision to submit it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Allali G, Launay CP, Blumen HM, Callisaya ML, De Cock AM, Kressig RW, et al. Falls, cognitive impairment, and gait performance: results from the GOOD initiative. J Am Med Dir Assoc. (2017) 18(4):335–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.10.008

2. Trevisan C, Ripamonti E, Grande G, Triolo F, Ek S, Maggi S, et al. The association between injurious falls and older adults’ cognitive function: the role of depressive mood and physical performance. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. (2021) 76(9):1699–706. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glab061

3. Salari N, Darvishi N, Ahmadipanah M, Shohaimi S, Mohammadi M. Global prevalence of falls in the older adults: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. (2022) 17(1):334. doi: 10.1186/s13018-022-03222-1

4. World Health Organization. WHO global report on falls prevention in older age. Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241563536 (cited November 28, 2023).

5. Florence CS, Bergen G, Atherly A, Burns E, Stevens J, Drake C. Medical costs of fatal and nonfatal falls in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2018) 66(4):693–8. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15304

6. Stinchcombe A, Kuran N, Powell S. Report summary—seniors’ falls in Canada: second report: key highlights. Chronic Dis Inj Can. (2014) 34(2/3):171–4. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.34.2/3.13

7. Government of Canada SC. Canadian Community Health Survey—Healthy Aging (CCHS). (2008). Available online at: https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&SDDS=5146&Item_Id=47962&lang=en (cited December 13, 2023).

8. Findorff MJ, Wyman JF, Nyman JA, Croghan CF. Measuring the direct healthcare costs of a fall injury event. Nurs Res. (2007) 56(4):283. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000280613.90694.b2

9. Newgard CD, Lin A, Caughey AB, Eckstrom E, Bulger EM, Staudenmayer K, et al. The cost of a fall among older adults requiring emergency services. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2021) 69(2):389–98. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16863

10. Ambulance and emergency health services | Alberta.ca. Available online at: https://www.alberta.ca/ambulance-and-emergency-health-services (cited November 29, 2023).

11. Ambulance Fees. Available online at: http://www.bcehs.ca/about/billing/fees (cited November 29, 2023).

12. Ambulance Fees | novascotia.ca. Available online at: https://novascotia.ca/dhw/ehs/ambulance-fees.asp (cited November 29, 2023).

13. Gouvernement du Québec. Cost of ambulance transportation. Available online at: https://www.quebec.ca/en/health/health-system-and-services/pre-hospital-emergency-services/cost-ambulance-transportation (cited November 29, 2023).

14. Government of Prince Edward Island. hpei_amb_rates.pdf. Available online at: https://www.gov.pe.ca/photos/original/hpei_amb_rates.pdf (cited November 29, 2023).

15. Province of Manitoba. Province of Manitoba | News Releases | Province Announces Ambulance Fees Now Reduced to Maximum of $250. Available online at: https://news.gov.mb.ca/news/index.html?archive=&item=45159 (cited November 29, 2023).

16. Government of Saskatchewan. Saskatchewan Ambulance Services | Emergency Medical Services in Saskatchewan. Available online at: https://www.saskatchewan.ca/residents/health/emergency-medical-services/ambulance-services#ground-ambulance (cited November 29, 2023).

17. Government of Ontario M of H and LTC. Ambulance Services Billing—Ontario Health Insurance (OHIP)—Publications—Public Information—MOHLTC. Government of Ontario, Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Available online at: https://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/public/publications/ohip/amb.aspx (cited November 29, 2023).

18. Office USGA. Ambulance Providers: Costs and Medicare Margins Varied Widely; Transports of Beneficiaries Have Increased | U.S. GAO. Available online at: https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-13-6 (cited November 29, 2023).

19. Toolkit WE. Ambulance Services. (2017). Available online at: https://www.princeedwardisland.ca/en/information/health-and-wellness/ambulance-services (cited November 29, 2023).

20. Habermann B, Shin JY. Preferences and concerns for care needs in advanced Parkinson’s disease: a qualitative study of couples. J Clin Nurs. (2017) 26(11–12):1650–6. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13565

21. Kelley CP, Graham C, Christy JB, Hersch G, Shaw S, Ostwald SK. Falling and mobility experiences of stroke survivors and spousal caregivers. Phys Occup Ther Geriatr. (2010) 28(3):235–48. doi: 10.3109/02703181.2010.512411

22. Kuzuya M, Masuda Y, Hirakawa Y, Iwata M, Enoki H, Hasegawa J, et al. Falls of the elderly are associated with burden of caregivers in the community. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2006) 21(8):740–5. doi: 10.1002/gps.1554

23. Tischler L, Hobson S. Fear of falling: a qualitative study among community-dwelling older adults. Phys Occup Ther Geriatr. (2005) 23(4):37–53. doi: 10.1080/J148v23n04_03

24. Joerns Healthcare. Hoyer Elevate®. Available online at: https://www.joerns.com/product/elevate/(cited July 19, 2024).

25. IndeeLift Human Floor Lift. Available online at: https://www.vitalitymedical.com/indeelift-human-floor-lift-400-550.html (cited January 2, 2024).

26. Bath Depot. Bellavita Dive Bath Lift. Available online at: https://www.bathdepot.ca/en/bellavita-dive-bath-lift-dm-477400252.html (cited January 2, 2024).

27. Greenhalgh M, Blaauw E, Deepak N, St Laurent COLM, Cooper R, Bendixen R, et al. Usability and task load comparison between a robotic assisted transfer device and a mechanical floor lift during caregiver assisted transfers on a care recipient. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. (2022) 17(7):833–9. doi: 10.1080/17483107.2020.1818137

28. Hernelind J, Roivainen G. High rise elevators-challenges and solutions in ride comfort simulations. In Chicago, IL. (2017). Available online at: http://www.3ds.com/events/science-in-the-age-of-experience

29. Ibex Lif. Ibex Lift—Helps Prevent Falls & Assists With Fall Recovery. Available online at: https://theibexlift.com/(cited January 2, 2024).

30. Tashakkori A, Teddlie C. Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research. Thousands Oak, London and New Delhi: SAGE. (2003). p. 189–208. ISBN: 0761920730

31. Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, Hoagwood K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health. (2015) 42(5):533–44. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

32. Teresi JA, Yu X, Stewart AL, Hays RD. Guidelines for designing and evaluating feasibility pilot studies. Med Care. (2022) 60(1):95–103. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001664

33. Hertzog MA. Considerations in determining sample size for pilot studies. Res Nurs Health. (2008) 31(2):180–91. doi: 10.1002/nur.20247

34. Sandelowski M. Sample size in qualitative research. Res Nurs Health. (1995) 18(2):179–83. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770180211

35. Vasileiou K, Barnett J, Thorpe S, Young T. Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2018) 18(1):148. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0594-7

36. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. (2006) 3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

37. Amankwaa L. Creating protocols for trustworthiness in qualitative research. J CULT DIVERSITY. (2016) 23(3):121–7. PMID: 29694754.

38. Handicare Canada. Handicare Canada—Stairlifts and Safe Patient Handling Products. Available online at: https://handicare.ca/(cited August 16, 2024).

39. Peters J, Bleakney A, Sornson A, Hsiao-Wecksler E, McDonagh D. User-driven product development: designed by, not designed for. The Design Journal. (2023) 27(1):133–52. doi: 10.1080/14606925.2023.2275868

40. Brim B, Fromhold S, Blaney S. Older adults’ self-reported barriers to aging in place. J Appl Gerontol. (2021) 40(12):1678–86. doi: 10.1177/0733464820988800

41. Wiles JL, Leibing A, Guberman N, Reeve J, Allen RES. The meaning of “aging in place” to older people. Gerontologist. (2012) 52(3):357–66. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr098

42. Maresova P, Režný L, Bauer P, Fadeyi O, Eniayewu O, Barakovic S, et al. An effectiveness and cost-estimation model for deploying assistive technology solutions in elderly care. Int J Healthc Manag. (2023) 16(4):588–603. doi: 10.1080/20479700.2022.2134635

43. de Witte L, Steel E, Gupta S, Ramos VD, Roentgen U. Assistive technology provision: towards an international framework for assuring availability and accessibility of affordable high-quality assistive technology. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology. (2018) 13(5):467–72. doi: 10.1080/17483107.2018.1470264

44. Marasinghe KM, Lapitan JM, Ross A. Assistive technologies for ageing populations in six low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMJ Innov. (2015) 1(4):182–95. doi: 10.1136/bmjinnov-2015-000065

Appendix 1

Interview guide for focus group discussion after the demonstration

Note: Most questions are general and those specific to a specific group is indicated in the guide, and highlighted in red.

1. How do you feel when you practiced using the Raymex™ lift in terms of comfort and safety?

Probes

○ How straightforward was the setup process for the Raymex™ lift

○ Are there technical challenges you encountered when you were practicing using the Raymex™ lift

2. Were there any pressure points or discomfort that you experienced when you practiced the demonstration?

3. How easy or difficult was it for you when you practiced the demonstration?

Probes

○ Did you face any challenges or confusion while operating them?

○ Where the controls self-explanatory to understand?

4. What are your thoughts on how helpful the Raymex™ lift would be to older adults, their family caregivers, formal caregivers (e.g., personal support workers), and clinicians?

Probes

○ Aside from lifting someone off the ground and preventing falls, what are the other things this Raymex™ lift can be used for?

○ In your experience, how do you think patients, family caregivers, and clinicians would respond to the Raymex™ lift

5. Based on your experience as a clinician or caregivers (formal), what are your thoughts regarding using the Raymex™ lift as a fall rehabilitation or preventive tool?

Probes.

○ How can you use this the Raymex™ lift as a fall rehabilitation or preventive tool?

○ Are there specific features that may need modification, and how do you suggest we modify?

6. Based on your experience as a clinician or caregiver (formal), what are your ideas regarding integrating the Raymex™ lift in your care planning?

7. Based on your experience, do you have any recommendations for enhancing the Raymex™ lift usability and functionality?

8. Is there any other thing you would like to discuss regarding the demonstration and the practice of the Raymex™ lift?

Interview guide for focus group discussions on the user setup and safety protocol.

Note: This guide will be used for all groups, however some questions are specific for a group and those are highlighted in red for the group

Users’ set-up draft

1. How explicit and easy to understand were the user instructions for the Raymex™ lift

2. Were there any aspects of the user setup draft that you found confusing or unclear?

Probes:

○ Please can we discuss those areas in the document?

○ What are your suggestions to enhance clarity?

3. Did the instructions adequately guide or would guide you through the process of setting up the Raymex™ lift?

Safety instruction

1. Did you think that the safety instructions were comprehensive?

2. Were there any aspects of the safety instructions that you find confusing or unclear?

Probes:

○ Please can we discuss those areas in the document?

○ What are your suggestions to enhance clarity?

3. As an older adult, did the safety protocol provide you with a clear steps to ensure yourself when you are using Raymex™ lift?

○ Were there any safety measures you found that would be particularly crucial when using the Raymex™ lift and why?

○ Are there any other safety measures that we should consider—please describe them?

4. As a caregiver or clinicians, did the safety protocol provide you with clear steps to ensure the older adults’ safety when using the Raymex™ lift?

Probes:

○ Were there any safety measures you found that would be particularly crucial when using the Raymex™ lift and why?

○ Are there any other safety measures that we should consider—please describe them?

5. Communication is often an issue during emergencies, such as falls. As a caregiver or a clinician, how well did the Raymex™ lift design and safety protocol facilitate communication between you and the older adults?

6. As a caregiver or a clinician, did the safety protocol address common scenarios and concerns you might face when using the Raymex™ lift based on your caregiving experience? If not, what are the scenarios and concerns we should consider incorporating into the Raymex™ lift

7. Is there any other information regarding the user’s guide and safety protocol that you want to discuss?

Appendix 2

Keywords: fall risk, lift assistance, aging, medical device, mobility

Citation: Kalu M, Chaston A, Alizadehsaravi N, Veras M and McArthur C (2024) Simulated real-world feasibility and feedback session for a lift assistance device, Raymex™: a mixed-method descriptive study. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 5:1455384. doi: 10.3389/fresc.2024.1455384

Received: 26 June 2024; Accepted: 21 August 2024;

Published: 6 September 2024.

Edited by:

Razan Hamed, Columbia University, United StatesReviewed by:

Hashem Abu Tariah, Hashemite University, JordanQussai Obiedat, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Jordan

Copyright: © 2024 Kalu, Chaston, Alizadehsaravi, Veras and McArthur. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Michael Kalu, bWthbHVAeW9ya3UuY2E=

Michael Kalu

Michael Kalu Andrew Chaston

Andrew Chaston Niousha Alizadehsaravi2

Niousha Alizadehsaravi2 Mirella Veras

Mirella Veras Caitlin McArthur

Caitlin McArthur