- 1School of Health Sciences, Queen Margaret University, Musselburgh, United Kingdom

- 2Institute for Applied Human Physiology, Bangor University, Bangor, United Kingdom

- 3Department of Renal Medicine, King’s College Hospital NHS Trust, London, United Kingdom

- 4Renal Medicine and Therapies, King’s College Hospital NHS Trust, London, United Kingdom

- 5Renal Sciences, Faculty of Life Sciences and Medicine, King’s College London, London, United Kingdom

Introduction: A multi-site randomized controlled trial was carried out between 2015 and 2019 to evaluate the impacts on quality of life of an intradialytic exercise programme for people living with chronic kidney disease. This included a qualitative process evaluation which gave valuable insights in relation to feasibility of the trial and of the intervention in the long-term. These can inform future clinical Trial design and evaluation studies.

Methods: A constructivist phenomenological approach underpinned face-to-face, semi-structured interviews. Purposive recruitment ensured inclusion of participants in different arms of the PEDAL Trial, providers with different roles and trial team members from seven Renal Units in five study regions. Following ethical review, those willing took part in one interview in the Renal Unit. Audio-recorded interviews were transcribed (intelligent verbatim) and inductively thematically analyzed.

Results: Participants (n = 65) (Intervention arm: 26% completed; 13% who did not; Usual care arm: 13%; 46% women; 54% men; mean age 60 year) and providers (n = 39) were interviewed (23% PEDAL Trial team members). Three themes emerged: (1) Implementing the Intervention; (2) Implementing the trial; and (3) Engagement of the clinical team. Explanatory theory named “the Ideal Scenario” was developed, illustrating complex interactions between different aspects of intervention and trial implementation with the clinical context. This describes characteristics likely to optimize trial feasibility and intervention sustainability in the long-term. Key aspects of this relate to careful integration of the trial within the clinical context to optimize promotion of the trial in the short-term and engagement and ownership in the long-term. Strong leadership in both the clinical and trial teams is crucial to ensure a proactive and empowering culture.

Conclusion: Novel explanatory theory is proposed with relevance for Implementation Science. The “Ideal Scenario” is provided to guide trialists in pre-emptive and ongoing risk analysis relating to trial feasibility and long-term intervention implementation. Alternative study designs should be explored to minimize the research-to-practice gap and optimize the likelihood of informative findings and long-term implementation. These might include Realist Randomized Controlled Trials and Hybrid Effectiveness-Implementation studies.

1. Introduction

Implementation research aims to address the research-to-practice time lag and the factors influencing this. Curran and colleagues (1) argue that as well as barriers relating to people, organizations and cultures, this delay is influenced by the stepwise approach to researching clinical efficacy, then establishing effectiveness, and finally researching implementation. Delaying research into external validity and implementation may miss opportunities both to optimize rehabilitation intervention acceptability and increase likelihood of long-term implementation. Reflection on the traditional research journey is crucial to ensure learning from experience alongside consideration of alternative research designs and methods that may be more supportive of long-term implementation.

In this paper, interactions between characteristics of effectiveness evaluation and potential for long-term implementation are explored using data from a specific clinical rehabilitation intervention and context: exercise during hemodialysis for people living with end-stage kidney failure. More than 21,000 people in the UK receive hemodialysis to manage their condition (2), however, longer life expectancy is not always accompanied by good quality of life (3). Numerous systematic reviews suggest that exercise training interventions can increase exercise capacity and physical function (4–17). Preliminary evidence suggests these improvements can also impact positively on quality of life, which is linked to reductions in mortality and morbidity (3, 18).

Evidence relating to exercise for people receiving hemodialysis consisted of small Trials, most of which were not considered to be of a high quality (11). Progression was needed through the development of a methodologically robust and adequately powered randomized controlled trial (RCT). Consequently, the PEDAL (“PrEscription of intraDialytic exercise to improve quAlity of Life in patients with chronic kidney disease”) Trial was conducted between 2015 and 2019 to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a six-month intradialytic exercise programme when compared with usual hemodialytic care (19). This multi-center RCT, with qualitative sub-study and process evaluation, focused on quality of life as a primary outcome. Participants were people living with end-stage kidney disease who had been receiving maintenance hemodialysis therapy for over a year. People from dialysis centers in five regions across the UK were web-randomized (random generation of treatment allocation carried out online) by the study Clinical Trials Unit to either usual care during hemodialysis (all aspects of hemodialysis treatment received normally with no additional intervention) or to the addition of exercise using static cycle ergometers (exercise bikes) during their thrice weekly dialysis sessions. Of 335 people who completed baseline assessments, 243 completed the follow-up data collection at six months. Analysis demonstrated that there was no statistically significant improvement in the primary outcome in the intervention group compared with the usual care group (p = 0.055). The study team concluded that the intervention did not effectively improve quality of life in this context.

The qualitative sub-study aimed to explain the impacts of the intervention when people were able to sustain participation and summarize influences on both trial and intervention participation throughout the study. This is explained in the full published study report in greater detail (19). Barriers to participation were found to be both individual (e.g., health status) and contextual, with influences from the Renal Unit as an integrated community and culture. Participants needed support at multiple levels to engage in the trial and continue participation in the intervention. For people who continued exercising throughout the study, qualitative data described physical, psychological, functional and social benefits and improved quality of life (19). This conclusion contrasted with the findings of the primary quantitative analysis but aligned with the multiple barriers to maintaining participation. Analysis indicated that people were mutually influential in relation to the study and intervention and these interdependencies were affected by leadership and culture.

The in-depth analysis generated further original insights of value to people planning a RCT within a community of people who are providing and receiving a similar service with rehabilitation elements over the long-term. The insights are particularly nuanced due to the collection of substantial amounts of qualitative data from people with different roles in and experiences of the trial, and from multiple contexts across the UK. Therefore, this qualitative analysis addressed the questions: what were the key insights gained in relation to the feasibility of the trial and sustainability of the intervention in the long-term? How can these insights inform future rehabilitation intervention evaluation studies with a view to implementation? The original study aim was to explore expectations and experiences of exercise training in people experiencing the PEDAL Trial as participants and as providers within the Renal Unit and the study team and it was possible to address the further research questions through these data.

2. Materials and methods

Ethical approval was granted by London Fulham Research Ethics Committee (reference 14/LO/1,851) and informed consent was provided by all participants.

A constructivist phenomenological approach (20) was used in conducting and analyzing data from face-to-face, semi-structured interviews. Participants were recruited from Hemodialysis Units in each of five regions: London (two sites); Central Scotland (two sites); North Wales and North-West (one site); East Midlands (one site) and West Midlands (one site). Participants were purposively recruited to ensure representation of people who had been randomized to: the intervention arm of the study and completed the intervention; the intervention arm of the study but dropped out of the intervention and remained within the trial; and the usual care arm of the study. Providers were recruited to include people involved with or employed by the PEDAL Trial and people working within the Renal Unit in different roles.

People were given an invitation and information letter by the person delivering the intervention at each site. They were able to ask questions and, if willing, signed a consent form before being interviewed once when available in the Renal unit. Semi-structured topic guides were used which focused on the study aims and were reviewed by the PEDAL project team and the Ethics Committee and pilot tested to ensure questions flowed and were understandable (Topic guides with all questions are included in Supplementary File S1).

Most interviews were conducted by CB (Academic with physiotherapy undergraduate training and post-doctoral level qualitative research expertise) who had responsibility for leading the qualitative sub-study and was not involved in other aspects of trial implementation, with no prior relationships with any trial participants and most of the providers interviewed. She trained a research assistant (Academic with Masters level qualification) who had no other involvement in the study and supervised her in conducting a minority of interviews. CB introduced herself to interviewees and explained that within this type of qualitative research her aim was to represent their views and experiences and not her own. CB was not involved with the rest of the trial or intervention and wished to hear the person's views and experiences in their own words. CB emphasized that participants' identities and data would be protected. People could move on from any question or end the interview at any time and were informed that interviews would not take more than one hour. Interviews took place when and where the interviewee preferred and all wished to be interviewed at the Renal Unit, despite occasional interruptions from other people within the unit. All interviews were individual except for two people who regularly received hemodialysis in a side room and requested a joint interview. Each site started and progressed recruitment at different times, resulting in interviews being carried out over 16 months, at different points in each participant's trial journey (May 2016 – September 2017). Analysis of participant characteristics took place when the study was unblinded in 2019.

Audio-recorded interviews were transcribed (intelligent verbatim) and anonymized. Participant verification of interview summaries was planned into the study; a lack of response from participants in the first two of five regions (large geographical regions within the UK) led a decision not to continue with this as the impact was believed to be insufficient. Field notes were kept by the interviewers and key points were integrated into transcripts prior to analysis.

Inductive thematic analysis (20) was carried out by CB and JS, supported by NVivo v10. Inductive thematic analysis is consistent with the constructivist phenomenological research approach taken. It enables findings to emerge from what is said by the interviewees in an inductive manner while ensuring that there is an audit trail in relation to decision-making and evidence for themes, increasing rigour. Key ideas were noted on transcripts while reading and re-reading and organized both in NVivo and in Mindjet MindManager 2019. These were synthesized to form sub-themes that linked similar ideas. Sub-themes were grouped based on defined conceptual similarities, forming themes. Themes and sub-themes were given codes to support data management and provide an audit trail. The terminology of “themes” and “sub-themes” was used to describe groupings of text with similar meaning. The term “code” was used to indicate the location of themes and sub-themes in relation to one another (e.g., Theme 1 and sub-theme 1a). This process was carried out for each transcript, leading to a final thematic framework, which was then re-applied across all transcripts by JS. Where participants connected ideas as they talked, this was noted (for example, descriptions of people ending their participation in the study because they were invested in the intervention but were allocated to the usual care group). These connections provided evidence of linkages between themes which informed development of explanatory theory relating to the study data, illustrated diagrammatically (CB). Explanatory theory was developed to enable conclusions about why specific findings emerged, such as why some people may have had more positive experiences of participation in the trial than others. Explanatory theory can help to inform guidance about how things can be optimized in the future. Finally, analysis explored how themes differed between site and region. It is not possible to share the full transcript data as consent was not obtained for this at the outset and the risk of identification from combined data in transcripts is too great. Instead, the research team has made the in-depth mind maps available as supplementary files to illustrate the process of increasing abstraction (See Supplementary Files S2, S3).

3. Results

3.1. Participants

Interviews were completed with 22% of the participants who were remained in the PEDAL Trial at six months (n = 65). By region, this included 16 people from London, 22 from Central Scotland, seven from North Wales and North-West, 11 from East Midlands, and nine from West Midlands. The intention had been to include 10% of the study participants in the qualitative sub-study, to provide a wide range of experiences and views. Data collection took place concurrently with recruitment, preventing calculation of percentage recruitment. Hence, interviews were carried out with as many people as possible on data collection days in each region.

Interviews included 27 people who completed the intervention; 20 people who dropped out of the intervention; and 18 people in the usual care arm of the study (16%, 40% and 13% of total trial participants, respectively).

Twenty-six participants were women (46%) and 31 were men (54%), and they varied by age (mean 60 years), and duration of dialysis (mean 43 months). They all received hemodialysis thrice weekly for 3.5–5 h. On average, interviews took place 11 months after informed consent was received. All trial participants who had received an invitation letter and who were available for interview on the qualitative data collection days agreed to participate. This resulted in 895 min of interview (mean of 14 per person, range 4–35 min), 133,405 words of interview text (495 pages of transcription).

In total, 39 “providers” were also interviewed, including five Renal Consultants, nine PEDAL employees who provided the intervention to participants or were involved in managing the trial, six Nurse Managers/Advanced Practitioners in the Renal Unit, nine Nurses and ten Health Care Assistants. Some providers were unavailable on data collection days but no one refused to participate for other reasons. This resulted in 739 min of interview (mean of 18 per person, range 6–53 min), 120,826 words of interview text (349 pages of transcription).

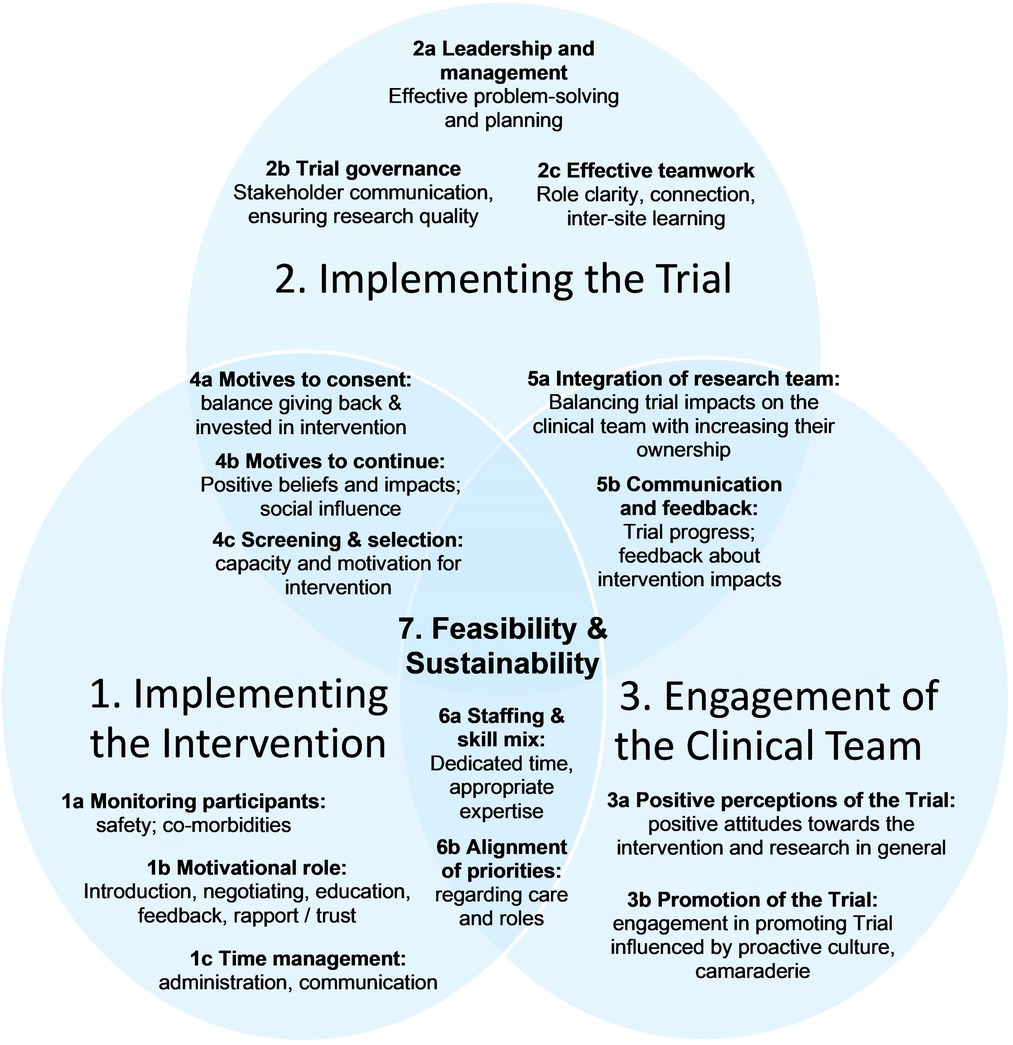

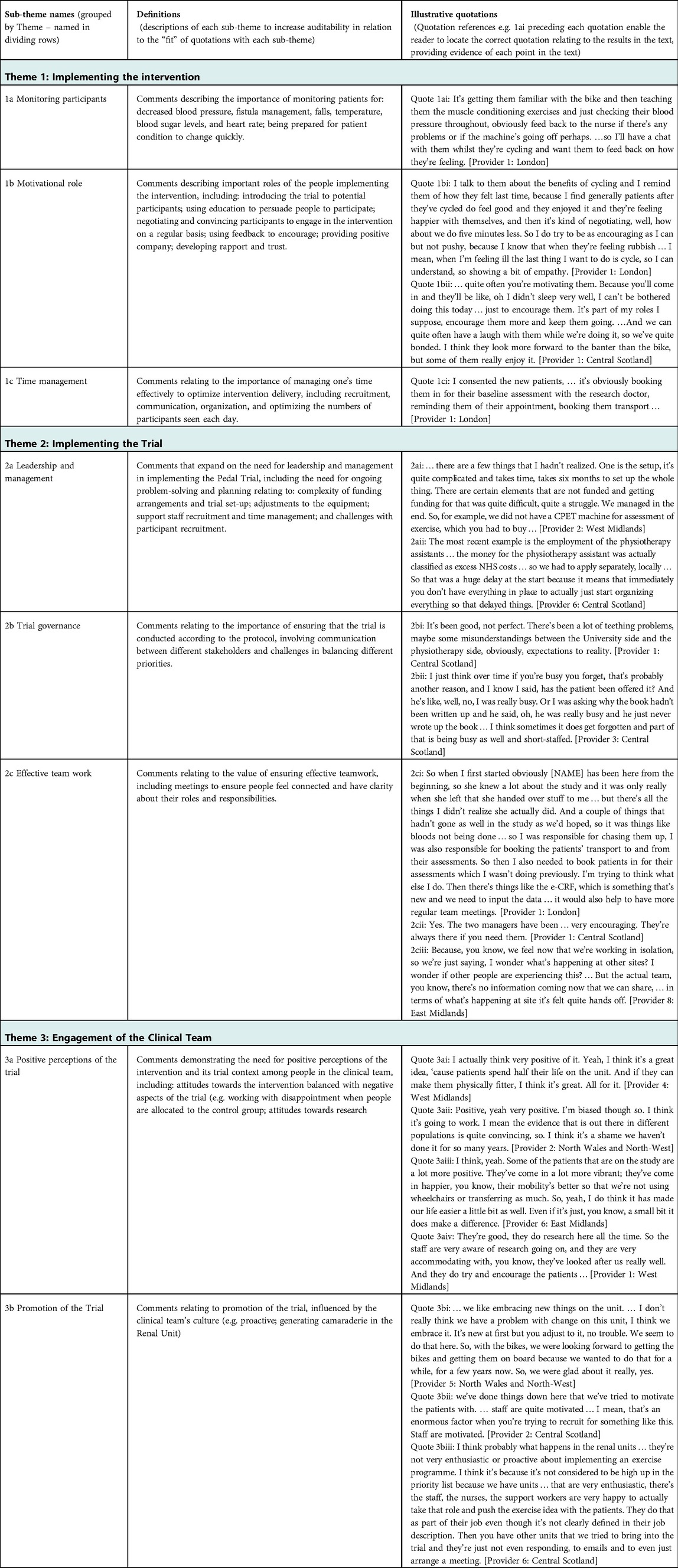

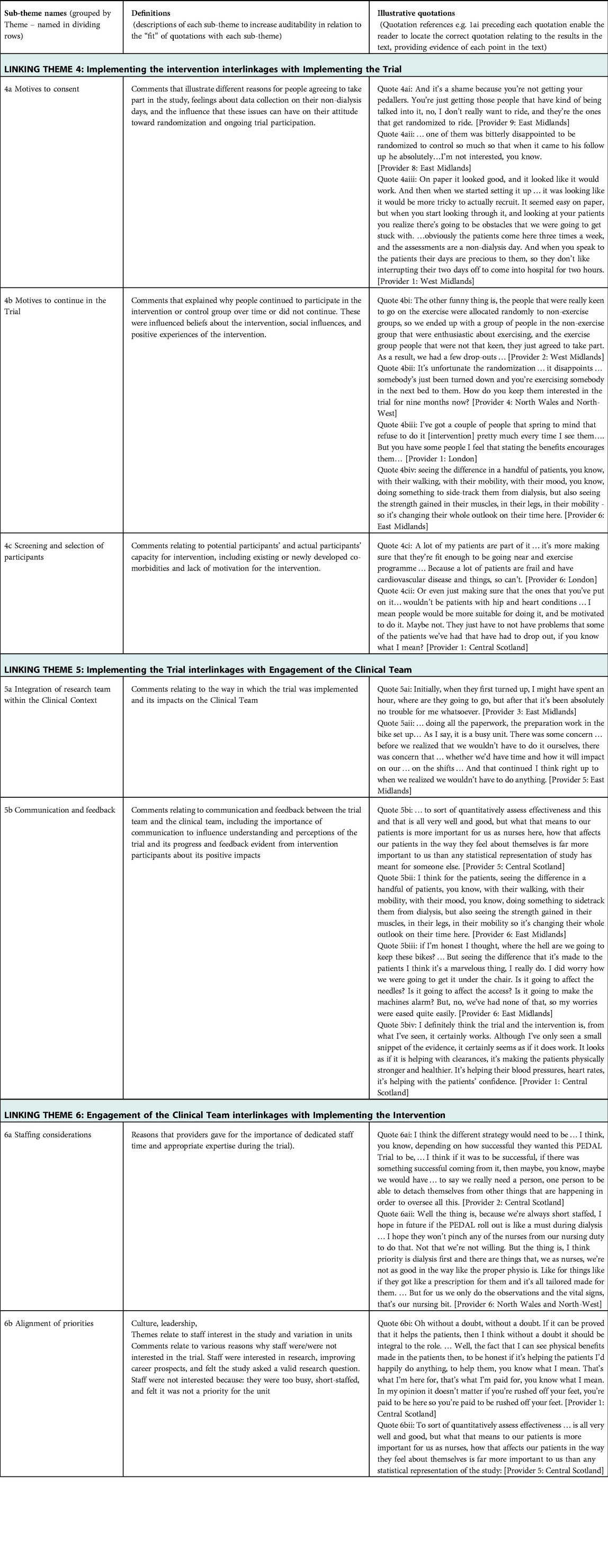

In-depth thematic analysis led to the development of explanatory theory, named “the Ideal Scenario,” illustrated in Figure 1. It reflects complex interactions between different aspects of intervention delivery and trial implementation with the clinical environment. Aspects that were optimal in different sites are represented, based on descriptions of what was and was not conducive to sustainable trial delivery and longer-term intervention sustainability. Three “initial themes” emerged: (1) Implementing the Intervention; (2) Implementing the trial; and (3) Engagement of the clinical team. Each theme is explained, followed by Table 1 which summarizes sub-themes, their definitions, and illustrative quotes (labelled to enable cross-referencing within the text). Interactions between initial themes 1–3 are explained next as “linking themes” 4–6, with evidence provided in Table 2. Finally, Theme 7 explains the “big picture” of feasibility of the trial and sustainability of the intervention in the long-term (evidence in Table 3). Quotations are drawn from the Provider interviews due to the focus of this article, and these are consistent with evidence from Participant interviews (19).

Table 3. Summary of data supporting interlinkages between all overarching themes in relation to trial feasibility and intervention sustainability.

3.2. Theme 1: implementing the intervention

Within Theme 1 pragmatic tasks required for the intervention are described, such as monitoring people and ensuring their safety (Quote 1ai), and more in-depth communication with people on each attendance day to encourage and motivate them (Quote 1bi, 1bii). The behavior change element of the intervention was not easy for people with variable health status and support for this required a careful balance of encouragement and persuasion with respect for the person's decision. Managing this alongside administrative tasks required well-developed time management skills (Quote 1ci).

3.3. Theme 2: implementing the trial

Implementation of the trial was demanding (Theme 2). Strong leadership and management were necessary to enlist different sites in the trial, work with the complexities of funding in different sites, ensure that equipment was appropriate and in the right places, recruit and train staff, and manage the ongoing trial requirements (Quotes 2ai, 2aii). Leadership was crucial to trial governance to ensure effective communication between all stakeholders (Quote 2bi), optimize the pace of participant recruitment, and ensure that protocols were followed despite other clinical demands (Quote 2bii). This required effective teamwork within each site in relation to role clarity and support when needed (Quote 2ci) and between sites to ensure that people felt connected to the wider trial team and could share strategies (Quote 2cii).

3.4. Theme 3: engagement of the clinical team

Successful recruitment of participants and their ongoing participation in the trial was influenced by engagement of the clinical team (Theme 3). It was important that providers had positive perceptions of the trial and the intervention. Some providers were supportive of the intervention due to consistency of its focus on exercise with their personal beliefs (Quotes 3ai, 3aii). Some had negative expectations but were pleased that the trial had fewer impacts on their workload than expected. Others were encouraged when they saw positive impacts of the intervention on participants (Quote 3aiii). Engagement in promoting the trial and intervention was higher where providers had a positive attitude towards involvement in research and development (Quote 3aiv), which was influenced by the culture within the clinical environment. For example, participants in some sites described embracing change, motivated teams, and willingness to engage with new aspects of their role. They also explained how this impacted on their actions, such as being very proactive in talking to possible participants (Quotes 3bi–iii).

3.5. Linking theme 4: implementing the intervention overlapping with implementing the trial

Linking Theme 4 demonstrates the complex balance between maintaining trial fidelity and ensuring trial recruitment. The burden of data collection for the participant was a barrier; people were required to attend for this on a non-dialysis day, potentially at a substantial distance from their home (Quote 4aiii). Some people agreed to participate because they were highly motivated to participate in the intervention, while others were motivated to “give back” to the service (Quotes 4ai–ii). These contrasting motivations influenced ongoing participation in the trial. If people who wanted to exercise were not randomized to the intervention group it was much harder to encourage ongoing participation in the usual care group, with data collection sessions on days of respite from hemodialysis (Quote 4aiii, 4bi–ii). In contrast, people with less interest in exercising found it difficult to sustain participation in the intervention group (Quote 4biii), although this was sometimes positively influenced by the benefits of taking part (Quote 4biv). Some people were more suitable for the intervention than others, with people having to stop participating early due to developing comorbidities (Quote 4ci). Providers also commented about characteristics that they felt were likely to affect success of the participant in the trial, such as low motivation (Quote 4cii).

3.6. Linking theme 5: implementing the trial interlinkages with engagement of the clinical team

Linking Theme 5 describes how trial feasibility was influenced by clinical team engagement. Minimal impact of trial delivery was seen as important and there were multiple descriptions of providers being pleasantly surprised that this was the case (Quotes 5ai–ii). There was a risk that this led to lack of engagement of the clinical team with the trial who did not then develop a sense of ownership. It was important that the trial team were communicating about how it was progressing, including what stage they had reached in relation to timescales. Clinical team members also found it very motivating and engaging when they saw people responding well to the intervention (Quotes 5bi–iv).

3.7. Linking theme 6: engagement of the clinical team interlinkages with implementing the intervention

When considering potential long-term implementation of the intervention, the clinical team had specific thoughts relating to the amount of staff time and specific expertise required (Quote 6ai–ii). Views seemed to be affected by the degree of alignment described between the clinical team's priorities and those of the research team. Some clinical team members described being willing to make changes to their role if it would support the wellbeing of service users (Quote 6bi). One person explained that the value of the intervention must be clear from the changes they see in their service users (Quote 6bii).

3.8. Overarching theme 7: trial feasibility and intervention sustainability

The results of detailed analysis suggest enormous complexity in running a trial successfully in multiple contexts. An RCT structure has elements that may be difficult to accept for people who are delivering a service and provide support and care to individuals over a sustained period. It is painful to see a person allocated to the control group when they joined the trial with a strong desire to participate in the intervention (Quote 7ai–ii). It is hard to persuade people who are suffering to give up precious time away from the hospital to do assessments. It is demotivating to be criticized for not recruiting enough people or implementing the intervention exactly as it is written on paper (Quote 7aii–iii). Analysis suggests the greatest likelihood of a trial being successfully delivered comes from a supportive culture in the clinical environment and highly effective communication between the trial and clinical teams. Even where there is a highly proactive culture in the clinical environment there must be clear explanation of reasons for decisions, flexibility wherever possible, and ways of compensating those in the control group for the loss of the intervention experience.

Ensuring that a trial does not impact heavily on the clinical environment is intuitively appealing. It is more likely to be accepted within the clinical environment and achieve greater standardization across different sites. This prioritization of trial integrity may have a detrimental effect in the long-term, however. Firstly, even with minimal impact on workload, implementation of the trial is highly visible to people working within the clinical environment. They have time to think about what it could mean for them in the long-term, while not necessarily feeling invested in the outcome. In some sites, this led to reservations or resistance in relation to long-term implementation without substantially increased resources (Quotes 7bi–ii). In trial sites with less reliance on people employed through the trial, involvement was driven by a proactive culture and belief in a wider role of the provider (Quotes 7biii–vi). One site aimed to develop camaraderie within the clinical environment and provide different activities to engage people during Hemodialysis. Due to less resourcing of intervention delivery, it was not as “pure” as at other sites, due to competing demands of staff. It was noticeable that people spoke more positively about implementation in the longer-term without this requiring external resourcing, for example, by integrating a new role into future job descriptions. At another site a trial employee who was already embedded in the wider team invested substantially in communicating with everyone in the clinical environment. One interview with the person who stored the equipment illustrated initial frustration with the increased challenge to available space, which was ultimately converted to enthusiasm about the intervention and involvement in camaraderie with participants. Such strategies embed the intervention over time, increasing the likelihood of longer-term implementation. Another interview illustrated that such embedding may also increase the likelihood of participants continuing to engage with the intervention beyond the trial, due to feeling safe and trusting the providers (Quote 7bvii).

4. Discussion

This qualitative analysis addressed questions relating to feasibility of the trial and sustainability of the intervention in the long-term and how insights can be used to inform future rehabilitation intervention evaluation studies with a view to implementation. Three key ideas will be discussed in this section, informed by the research findings. First, “The ideal scenario” explanatory theory aims to provide insights for people who are planning RCTs with contextual similarities to the PEDAL Trial. This could be used to support pre-emptive and ongoing analysis of risks to future trials and feasibility of their delivery over time.

Second, the possibility is discussed that other types of study design may suit many rehabilitation contexts better and lead to more informative results. Quantitatively, the PEDAL Trial fell short of statistical significance (p = 0.055) for the intervention, while qualitative evidence suggested that it could have substantial positive impacts for some people (see Table 13 and pages 34–39 of the original project report (19). Other types of study design might analyze this more usefully and provide more valuable conclusions for policymakers.

Third, some study findings suggested that the trial context might lead to negative perceptions of the intervention within the clinical setting that may jeopardize longer-term implementation. The potential for integrating implementation research earlier in the research to practice journey is discussed further.

4.1. Insights for future RCTs

RCT design and delivery requires a complex interplay between individuals with different roles, operating within different systems, and with different agendas. The person receiving the intervention is at the center of this, as it is their decision to engage with the trial and intervention. Many things can influence this decision, however, including the person's beliefs and priorities, the culture of the clinical environment, and strategies used by the trial team.

To facilitate consideration of whether “The Ideal Scenario” explanatory theory may be useful to your context, we have identified some key characteristics of the PEDAL Trial context. These involve:

• implementation of the trial within different sites, each with an integrated community of providers and potential participants which differ in leadership and culture;

• the possibility that ensuring trial and intervention fidelity may conflict with ability to recruit and maintain participation;

• evaluation within a social context of an intervention that involves a complex behavior of varying appeal to participants; and

• evaluation of an intervention which may be viewed as beyond the current scope or roles of key clinical providers.

For trial planners who see commonalities between their context and that of the PEDAL Trial, it may be useful to use the explanatory theory within a risk assessment process. Each aspect of the theory represented in Figure 1 can be considered carefully during the planning stage of a trial and then later as the trial progresses. Where a site identifies risks, problem solving can be used where possible to mitigate these and reduce their impact on trial recruitment, retention, quality, and likelihood of implementation post-Trial.

4.2. Insights suggesting alternative study designs focusing on impacts of an intervention

In some circumstances alternative study designs may be more informative and potentially more philosophically aligned with the worldwide aspiration to person-centered practice (21, 22).

Our results demonstrated challenges in recruiting and retaining involvement of appropriate clinical sites and participants. The burden of data collection influenced both consent and completion of the trial, as did randomization of participants to intervention and control groups. When designing an RCT optimizing external validity often requires inclusion of as many people as possible, minimizing exclusion criteria. This can mean that people who are less likely to benefit from the intervention are included because there is no specific reason that they should not participate. A contributing factor to the PEDAL Trial's lack of significant improvement in quality of life was the low compliance rate of 47% of sessions completed by participants, and an even lower percentage of engagement (18%) in the prescribed exercise intensity and duration. For many participants the training load and duration were insufficient to elicit physiological changes with potential to impact upon health-related quality of life. Qualitative findings provided insights into the barriers to participation (19). These challenges ultimately influenced the final quantitative results being unsupportive of the intervention effect despite highly supportive qualitative findings for some participants.

Bonnell and colleagues (23) argue for conducting Realist RCTs when evaluating complex public health interventions. They contend that RCTs generally fail to explore the ways in which aspects of the intervention and the local evaluation context interact. In contrast, Realist evaluations develop prior theory about what works, for whom, and in what circumstances. The Realist paradigm sees evaluation as exploring “an open system of dynamic structures, mechanisms and contexts that intricately influence the change phenomena that evaluations aim to capture” (23 p. 2,299). Bonnell et al. (23) argue that neither RCTs nor Realist approaches achieve everything that is needed and merging the two is optimal. The RCT enables testing of a potentially causal mechanism under optimal conditions; meanwhile, further contexts can be investigated in relation to influences of unexpected underlying mechanisms on outcomes in a Realist Evaluation. They argue that most interventions will impact positively on some people, in some conditions, which is the most important information for policymakers.

While the PEDAL Trial took place in clinical settings, rather than a public health context, the needs of the evaluation appear to be similar. Public health interventions are described as complex social interventions, in contrast to pharmacological ones, for example, and interact with their contexts in different ways (23). Our qualitative analysis suggests that that there were also numerous social influences on the PEDAL Trial. Bonnell and colleagues argue that most RCTs collect information that would enable development of mid-level programme theory (23). To explore this suggestion, some of the qualitative results of the PEDAL Trial reported by Greenwood et al. (19) have been reformulated into a “Context-Mechanism-Outcome” (CMO) statement: “People who had sufficient motivation for the intervention and good enough health status (Context) and who were in a clinical environment that cultivated positive and empowering relationships (Context and Mechanism), were more likely to continue exercising while undergoing hemodialysis three days a week (Mechanism) in Renal Units which promoted the Trial (Context and Mechanism), leading to improvements in their physical, functional, psychological and social wellbeing (Outcome).” When constructing this statement from key study findings we found overlap in what can be considered context and mechanism. It would be interesting to explore the validity of this statement using post-hoc quantitative analysis.

Bonell et al. suggest placing greater emphasis on ensuring trial fidelity in relation to the processes and functions within the intervention (mechanisms of change), rather than precise activities (23). Ongoing qualitative research could explore ways in which mechanisms and outcomes differ at each trial site and quantitative data can be used to test evolving theories. In this way, a Realist RCT can explore validity of the theory as well as effectiveness of the intervention. If supportive, this theory could then be applied more flexibly in different clinical contexts, supporting long-term implementation.

4.3. Insights suggesting alternative study designs that consider long-term implementation

PEDAL Trial analysis found challenges in reconciling the competing demands of reducing impacts of the trial on the clinical environment in the short term, and enlisting providers to enable implementation in the long-term. Funding of trial employees may optimize trial fidelity; however, local providers are less likely to have a sense of ownership of the intervention. Local providers can also become alert and resistant to possible future changes in their role. By collecting qualitative data from sites in all five study regions it was possible to compare different scenarios within the PEDAL Trial. There were clear reservations about intervention implementation in sites that were experiencing greater pressures relating to staffing and morale, were less proactive about research, and where people had a less empowering and more maintenance-driven approach to their role. In contrast, some sites had proactive, enthusiastic cultures, interest in research, and desire to support camaraderie, independence, and wellbeing in their community of service users. In the latter, there was greater emphasis on problem-solving when discussing longer-term implementation.

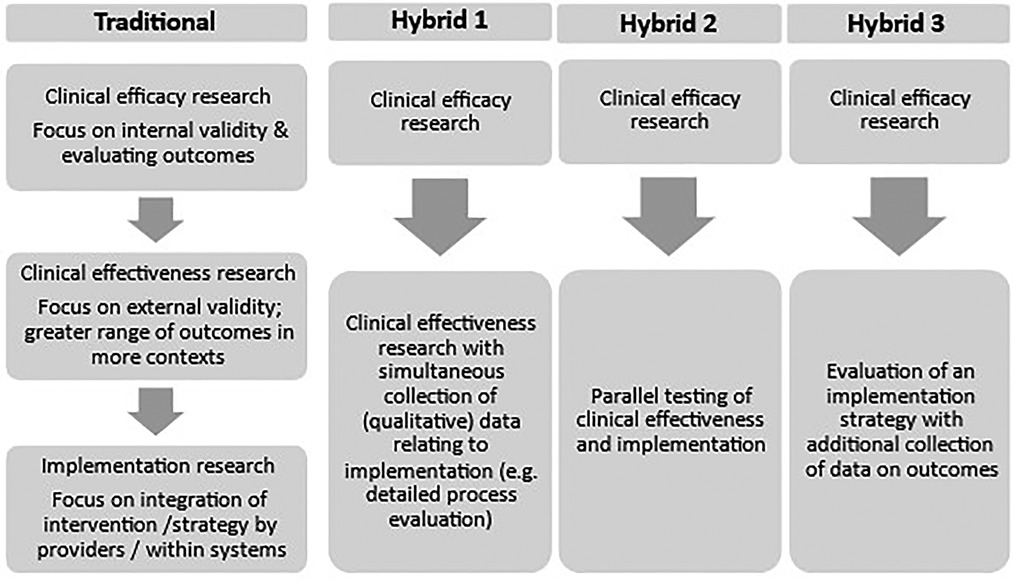

It is possible that where there is existing evidence to support an intervention, an alternative study design would enable a more positive change management process that does not risk alienating providers. Glasgow et al. (24) argue that RCTs focus on internal validity at the expense of important questions relating to how the intervention might be implemented in varied contexts and maintained over time. Curran and colleagues (1) advocate for “effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs” in some circumstances, to blend clinical effectiveness and implementation studies and thereby reduce the time lag for knowledge translation and develop more insightful implementation strategies. Figure 2 compares the traditional research journey with three different suggested hybrid approaches (1) which aim to integrate exploration of clinical uptake of the intervention with effectiveness evaluation.

Figure 2. Summary of a traditional model of progression from clinical efficacy to clinical effectiveness and implementation research and three proposed effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs [based on information from Curran et al (1)].

Considering Figure 2, the PEDAL Trial followed a primarily traditional pattern and was situated within “clinical effectiveness research”, building on earlier efficacy studies. The qualitative sub-study collected detailed data to inform process evaluation, giving it some similarities to Hybrid 1 which involves effectiveness studies with additional process evaluation. The PEDAL Trial did not involve interviews with administrators, policymakers, or other departments (e.g., Physiotherapy), however, which could have informed wider implementation. If planning the qualitative sub-study with an implementation mindset, these participants might have been included, giving further insights. This hybrid design is advocated in specific conditions, for example, where the intervention has face validitybase and minimal risk (1). A possible limitation to this approach is that the trial context itself may create barriers to implementation, as experienced within, a strong initial evidence the PEDAL Trial.

Hybrid 2 emphasizes clinical effectiveness and implementation more equally – for example, testing an intervention in “best” and “worst” and “medium” case conditions. This sounds appealing; however, it would be necessary to develop insights into what would make a case better or worse in relation to implementation, which may be an iterative process. For example, we can see retrospectively that some clinical sites involved in the PEDAL Trial had characteristics that might present more challenges to implementation, and it is unlikely that previously published studies would have given these insights.

The third Hybrid design involves supplementing an implementation study with data collection relating to intervention outcomes. This is advocated especially where it seems likely that the outcomes of the intervention will be heavily influenced by different and less controlled contexts. This seems likely to be the case for many rehabilitation interventions which involve behavior change for the participant, input from a multidisciplinary team, reorganization of the physical environment, and reallocation of resources. In the current financial context of the UK National Health Service many service changes must be made within existing resources. This is a complex challenge and is likely to require different strategies, such as co-production and change management.

4.4. Strengths and limitations

Study strengths include the quantity of qualitative data available for analysis. The concept of data saturation is more relevant to Grounded Theory, however, no new themes were emerging on completion of data collection and analysis. Two researchers cross-checked one another's interpretation of the data (CB, JS) and analysis continued to the point of developing novel explanatory theory. The qualitative sub-study included both racially and geographically diverse participants who were involved in the trial in multiple ways. We talked to people who were considered “drop-outs” from the intervention, which is unusual as people often leave the study and are not available further data collection. This added a further dimension to analysis.

Limitations included the challenges of data collection in busy clinical contexts, with background noise and interruptions. This made transcription harder but the researchers prioritized the needs of participants in relation to interview timing and location and this led to a high participation rate. Interviews varied substantially in length, which reflects differences in how reflective and communicative people were. The involvement of a second researcher for a minority of interviews may have introduced some inconsistencies and this risk was minimized where possible through training and supervision. There was a substantial time delay between participants consenting to the study and qualitative data collection taking place. This is because consent was given to participation in the whole study, of which the qualitative sub-study was only one stage which took place after people had experienced the intervention. Because of the delay, we ensured that people received an additional information letter by a study employee based in their site, just before the qualitative data collection was due to take place and were advised that they did not have to participate. When considering Provider participant numbers, it was not possible to calculate the percentage of providers who were interviewed relative to the total number of possible providers. Recruitment took place from the pool of all people providing or supporting care within the Hemodialysis Unit and PEDAL Trial team at different points in time. The total number of people employed within the Units fluctuated over time.

5. Conclusion

This paper reports on original insights from a large, rigorous qualitative process evaluation of a multi-center RCT which evaluated clinical effectiveness and cost effectiveness of a six-month intradialytic exercise programme when compared with usual care. The analysis has led to novel explanatory theory with relevance for evaluation of rehabilitation interventions. The “Ideal Scenario” is provided to guide trialists in pre-emptive and ongoing risk analysis relating to trial feasibility and long-term intervention implementation. This has international relevance as the detailed analysis led to identification of key aspects of different clinical contexts that were optimal and trialists can risk-assess their own clinical contexts in relation to these characteristics. Key insights include the need for careful integration of the trial within the clinical context to optimize promotion of the trial in the short-term and engagement and ownership of the intervention in the long-term. Strong leadership in both the clinical and trial teams is crucial to underpin a proactive and empowering culture.

The challenges of delivering an RCT of a complex rehabilitation intervention in a way that does not negatively impact potential for long-term implementation make it important to consider alternative study designs. Realist RCTs may provide more nuanced and informative results which indicate who can benefit from the intervention and in what circumstances. Effectiveness – Implementation Hybrid study designs prompt more careful consideration and integration of principles of Implementation Science research at an earlier stage in the research journey. This may help to counteract possible negative impacts of the trial experience on the clinical context that could jeopardize long-term implementation.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due the risks of identifiability through combined data but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request supported by appropriate ethics review. Requests to access the datasets should be directed toY2J1bGxleUBxbXUuYWMudWs=.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by London Fulham Research Ethics Committee (reference 14/LO/1,851). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

ICM, THM, SAG, PK, JHM and CB: were involved in the PEDAL Trial study design and funding application. The qualitative sub-study study proposal and ethics application were developed by CB. Data collection was facilitated by SAG, JHM, and PK and carried out by CB. Analysis and interpretation were carried out by CB and JS. The final manuscript was developed by CB. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This project was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment programme. The funding body did not influence study conduct or reporting.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge all participants in the qualitative sub-study of the PEDAL Trial. We appreciate the support of Sarah Bond in the data collection process.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fresc.2023.1100084/full#supplementary-material.

References

1. Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care. (2012) 50:217–26. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812

2. Ashby D, Borman N, Burton J, Corbett R, Davenport A, Farrington K, et al. Renal association clinical practice guideline on hemodialysis. BMC Nephrol. (2019) 20:379. doi: 10.1186/s12882-019-1527-3

3. Sietsema KE, Amato A, Adler SG, Brass EP. Exercise capacity as a predictor of survival among ambulatory patients with end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. (2004) 65:719–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00411.x

4. Heiwe S, Jacobson SH. Exercise training for adults with chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2011) 10:CD003236. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003236.pub2

5. Heiwe S, Jacobson SH. Exercise training in adults with CKD: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Kidney Dis. (2014) 64:383–93. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.03.020

6. Cheema BS, Chan D, Fahey P, Atlantis E. Effect of progressive resistance training on measures of skeletal muscle hypertrophy, muscular strength and health-related quality of life in patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. (2014) 44:1125–38. doi: 10.1007/s40279-014-0176-8

7. Segura-Ortí E. Exercise in hemodialysis patients: a literature systematic review. Nefrologia. (2010) 30:236–46. doi: 10.3265/Nefrologia.pre2010.Jan.10229

8. Smart N, Steele M. Exercise training in hemodialysis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrology. (2011) 16:626–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2011.01471.x

9. Salhab N, Karavetian M, Kooman J, Fiaccadori E, El Khoury CF. Effects of intradialytic aerobic exercise on hemodialysis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Nephrol. (2019) 32:549–66. doi: 10.1007/s40620-018-00565-z

10. Sheng K, Zhang P, Chen L, Cheng J, Wu C, Chen J. Intradialytic exercise in hemodialysis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Nephrol. (2014) 40:478–90. doi: 10.1159/000368722

11. Chung YC, Yeh ML, Liu YM. Effects of intradialytic exercise on the physical function, depression and quality of life for hemodialysis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Clin Nurs. (2017) 26:1801–13. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13514

12. Pu J, Jiang Z, Wu W, Li L, Zhang L, Li Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of intradialytic exercise in hemodialysis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. (2019) 9:e020633. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020633

13. Young HML, March DS, Graham-Brown MPM, Jones AW, Curtis F, Grantham CS, et al. Effects of intradialytic cycling exercise on exercise capacity, quality of life, physical function and cardiovascular measures in adult hemodialysis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. (2018) 33:1436–45. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfy045

14. Huang M, Lv A, Wang J, Xu N, Ma G, Zhai Z, et al. Exercise training and outcomes in hemodialysis patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Nephrol. (2019) 50:240–54. doi: 10.1159/000502447

15. Zhao QG, Zhang HR, Wen X, Wang Y, Chen XM, Chen N, et al. Exercise interventions on patients with end-stage renal disease: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. (2019) 33:147–56. doi: 10.1177/0269215518817083

16. Clarkson MJ, Bennett PN, Fraser SF, Warmington SA. Exercise interventions for improving objective physical function in patients with end-stage kidney disease on dialysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. (2019) 316:F856–72. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00317.2018

17. Neto MG, de Lacerda FFR, Lopes AA, Martinez BP, Saquetto MB. Intradialytic exercise training modalities on physical functioning and health-related quality of life in patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil. (2018) 32:1189–202. doi: 10.1177/0269215518760380

18. Stack AG, Molony DA, Rives T, Tyson J, Murthy BV. Association of physical activity with mortality in the US dialysis population. Am J Kidney Dis. (2005) 45(4):690–701. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.12.013

19. Greenwood SA, Koufaki P, Macdonald JH, Bulley C, Bhandari S, Burton J, et al. Web-based exercise programme to improve quality of life for patients with end-stage kidney disease receiving dialysis: the PEDAL RCT. Health Technol Assess. (2021) 25:1–52. doi: 10.3310/hta25400

21. McCormack B, McCance T, Bulley C, Brown D, Martin S, McMillan A. Fundamentals of person-centerd healthcare practice. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons Ltd (2021).

22. Reivonen S, Sim F, Bulley C. Learning from biology, philosophy and sourdough bread - challenging the evidence-based practice paradigm for community physiotherapy. In: Nicholls D, Synne Groven K, Kinsella EA, Lill Anjum R, editors. Mobilising knowledge: A second critical physiotherapy reader. Abingdon: Routledge (2021). p. 83–97.

23. Bonnell C, Fletcher A, Morton M, Lorenc T, Moore L. Realist randomised controlled trials: a new approach to evaluating complex public health interventions. Soc Sci Med. (2012) 75:2299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.08.032

Keywords: implementation, feasibility, sustainability, chronic kidney disease, hemodialysis, exercise, quality of life

Citation: Bulley C, Koufaki P, Macdonald JH, Macdougall IC, Mercer TH, Scullion J and Greenwood SA (2023) Feasibility of randomized controlled trials and long-term implementation of interventions: Insights from a qualitative process evaluation of the PEDAL trial. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 4:1100084. doi: 10.3389/fresc.2023.1100084

Received: 16 November 2022; Accepted: 3 January 2023;

Published: 1 February 2023.

Edited by:

Jack Jiaqi Zhang, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaReviewed by:

Arthur Sá Ferreira, University Center Augusto Motta, BrazilLuca Sebastianelli, Hospital of Vipiteno, Italy

© 2023 Bulley, Koufaki, Macdonald, Macdougall, Mercer, Scullion and Greenwood. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Cathy Bulley Y2J1bGxleUBxbXUuYWMudWs=

Specialty Section: This article was submitted to Interventions for Rehabilitation, a section of the journal Frontiers in Rehabilitation Sciences

Cathy Bulley

Cathy Bulley Pelagia Koufaki1

Pelagia Koufaki1 Jamie Hugo Macdonald

Jamie Hugo Macdonald Iain C. Macdougall

Iain C. Macdougall Thomas H. Mercer

Thomas H. Mercer