- 1Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, The University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, United States

- 2UAB-Lakeshore Foundation Research Collaborative, Birmingham, AL, United States

- 3Division of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, The University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, United States

- 4Department of Health Services Administration, The University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, United States

- 5Department of Surgery, The University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, United States

- 6Dean's Office, The University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, United States

People with neurological and physical disabilities (PWD) experience a myriad of secondary and chronic health conditions, thus, reducing their participation and quality of life. A telehealth exercise program could provide a convenient opportunity for improving health in this population. To describe participants' perceived benefits of a telehealth physical activity program among PWD, we conducted semi-structured interviews with 30 study participants after completing the 24-week program SUPER-HEALTH (Scale-Up Project Evaluating Responsiveness to Home Exercise and Lifestyle TeleHealth). Interview data were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed using inductive thematic analysis. The mean age of the sample was 51 ± 13 years, the primary disability was Multiple Sclerosis, and there were nine men (30%) and 21 (70%) women. Inductive thematic analysis resulted in four themes that include the following: (1) improved health and function, (2) increased activity participation, (3) improved psychosocial health, and (4) optimized performance and benefits. These preliminary findings provided support for the use of a home exercise program and recommendations to improve it to enhance benefits among PWD.

Introduction

People with disabilities (PWD) are highly susceptible to secondary health conditions, including osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, decreased balance, strength, endurance, fitness, flexibility, increased spasticity, weight problems, and depression (1–4). These secondary health conditions are exacerbated by a physically inactive lifestyle prevalent in this population, which has been linked to poor health outcomes (5, 6). Compared to people without disabilities, PWD is three times more likely to experience a stroke or heart attack (7–9). Additionally, this places a further burden on the healthcare system (8, 10).

The health needs of PWD are extensive and drive the need for health promotion strategies and catered rehabilitative care in and outside of medical institutions (11). While some preliminary exercise interventions have shown to improve functional motor recovery and overall health in patients needing neurological care (12), many current rehabilitation models do not have a systematic prescription to optimize exercise maintenance in the long run. Care is prioritized in the acute period after the neurological injury/diagnosis and is focused on the recovery of ADL skills and basic mobility rather than improving the sedentary lifestyle (11). Unfortunately, this sedentary lifestyle can be attributed to the many barriers encountered by this population at every level of the socioecological model, including the intrapersonal level (e.g., low self-efficacy); interpersonal level (e.g., low social support), organizational level (e.g., lack of programming or trained personnel), community (e.g., inaccessible parks), and policy (e.g., local transportation) (13). If patients had means of accessing care acutely and in the long term, medical personnel could emphasize not only restoring ADLs in their rehabilitation, but also promoting exercise and physical mobility to improve quality of life and reduce further complications.

To address these barriers, researchers in rehabilitation sciences and health education have adapted health interventions to allow for online delivery and two-way audio-visual communication, also known as telehealth (14). Studies have shown that telehealth has proven to be effective for the rehabilitative management of patients because of reduced health care expenses, easy access to care (without any transportation), and less disruption to care (15). Allowing participants to engage with health-enhancing programs, and as a physical activity-based intervention, from the comfort of their own home is a notable benefit in convenience for patients.

To evaluate whether a telehealth exercise program can increase physical activity and improve functional outcomes and quality of life in PWD, a home-based exercise program was developed, the SUPER-HEALTH (Scale-Up Project Evaluation Readiness to Home Exercise and Lifestyle Tele-Health). This program was delivered via a mobile application (16) to provide the convenience of completing the program at home, which removes the barriers of transportation and inaccessible facilities, in addition to lack of knowledge and adapted exercises. The SUPER-HEALTH program addresses this issue by providing PWD with an online program that was modified from an on-site, evidence-based exercise intervention called Movement-to-Music (M2M). The current study aimed to explore participants' perceptions of potential benefits from a home-exercise program, with a specific focus on benefits related to physical health and function, participation, and psychosocial health. The second aim was to describe recommendations to enhance the benefits that could be received from the program.

Methods

Design

This study used a qualitative research design involving semi-structured interviews with purposefully selected individuals among a cohort of PWD who completed an RCT of physical activity. This study was approved by the institutional review board at the university, and participants provided verbal consent before participation.

SUPER-HEALTH program

The M2M is set to music to provide greater enjoyment from an exercise routine and includes aerobic and strength training (17). The structure of each M2M session includes a range of motion, muscle strength, balance, cardiorespiratory endurance, and cooldown. The application releases a new pre-recorded M2M exercise video each week for the participants, so they can use it to meet their weekly exercise goal. When a new routine is introduced, the routine is guided by an M2M instructor who provides verbal instruction and explains each movement pattern. The following week, the same routine is performed by a person with a similar disability but with no verbal instruction, and a new guided routine is also delivered. The routines delivered to participants were choreographed to music and designed for three functional groups: those able to stand, those seated only, and those with hemiparesis. The M2M videos incorporate ‘public domain' music to avoid copyright issues.

SUPER-HEALTH includes a 12-week adoption phase, a 12-week transition phase, and a follow-up completed at 48 weeks. The intervention includes a prescription of 48 min of exercise video content on the first week, and this amount increases each week, with 150 min delivered at week 24. Each participant received a Fitbit and a tablet with a study app. Research staff monitored participants' Fitbit and tablet activity each week and provided a coaching support call for participants with no activity. More details of the study are reported elsewhere (16).

Participants

Eligibility criteria for SUPER-HEALTH included: (a) self-report of a physical disability or mobility impairment, (b) 18 to 74 years of age, (c) not enrolled in a structured exercise program over the past 6 months, (d) can use upper, lower, or both sets of extremities to exercise, € can converse and read English, (f) medically stable to perform the home exercise as determined by their physician, and (g) wireless internet in the home. For the current study exploring program experiences, SUPER-HEALTH participants were selected for an interview after completing 24 weeks using a purposeful sampling strategy to promote diversity among interviewed participants. Participants were selected based on the following characteristics: functional level during exercise (seated, standing, and hemiparesis), gender, and race. The research team recorded this information before each interview to ensure that the sampling strategy was executed. This project aimed to recruit a convenience sample of 30 participants who had completed at least 24 weeks (primary endpoint) of the SUPER-HEALTH study.

Procedures

Participants who agreed to be interviewed were scheduled, and all interviews were completed over the phone. The interviews were semi-structured, with a max duration of 30 min. Interview questions focused on understanding participants' perceived benefits of the program regarding their physical and functional health, mental health, social health, and any other perceived benefits. Questions also included participant suggestions for enhancing perceived benefits in future telehealth exercise programs. Sample questions are displayed in Box 1.

Box 1. Sample interview questions

• Please tell me about your experience with the SUPER-HEALTH program.

• What benefits have you seen when exercising with the program?

• How do you feel when you exercise with the program?

• Describe to me some positive experiences of the program.

• What did you enjoy most about this program?

• Describe to me some negative experiences or issues you experienced with the program.

• What did you least like about this program?

• What did you find useful about this program? Why?

• What did you not find useful about this program? Why?

• How do you think this program helps you exercise more?

• What suggestions do you for improving the program?

Research team

For this study, the research team included six PhD-level academic researchers with two experts in qualitative research methods (NI and IH) and four researchers with a background in rehabilitation science (JW, JR, YK, and BL). One researcher (JW) has a disability and completed the interviews as part of a KL2 Mentored Career Development award. Another researcher (JR) was the mentor for the award and principal investigator of the exercise trial, from which the participants were interviewed.

Analysis

Demographics and disability characteristics were reported to describe the sample. Coding and analysis were guided by the Braun and Clarke 6-step thematic analysis (inductive) approach (17). First, interviews were transcribed by a professional transcription company and verified for accuracy by three analysts (JW, YK, and IH). Second, the analysts coded the data separately to generate an initial set of codes. Third, the analysts met to compare and contrast codes and search for themes (categories that represent the codes). Fourth, the analysts generated an initial set of themes into a small number of themes that were deemed saturated (i.e., sufficiently supported by participant quotes and codes). Fifth, they narrowed the themes into higher-level groupings (2nd tiered themes). Sixth, the themes were documented and reported. The iterative data analysis and discussion processes contributed to achieving trustworthiness between the two analysts (18). All analysts were not involved in conducting the intervention and had a background in adapted physical activity or rehabilitation science (JW and YK) and qualitative research (IH). In addition, the “critical friends” were involved to ensure an appropriate research process and weight on the interpretation of the relevance of themes (19). The critical friends in this study have been prolific in the field of rehabilitation research (BL) and qualitative research (NI), respectively.

Results

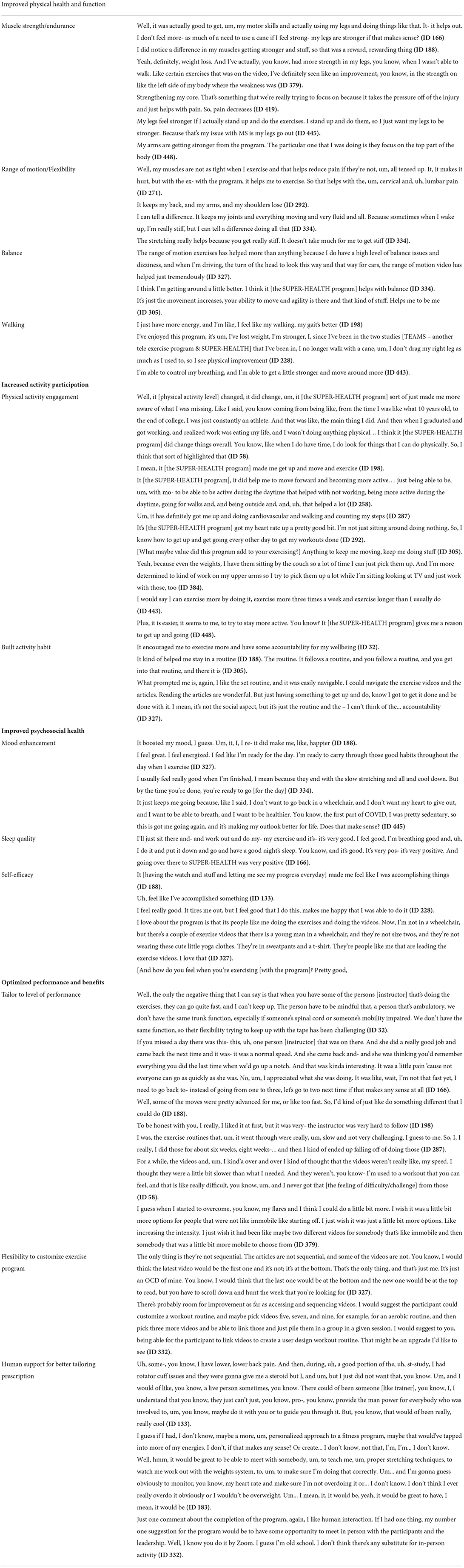

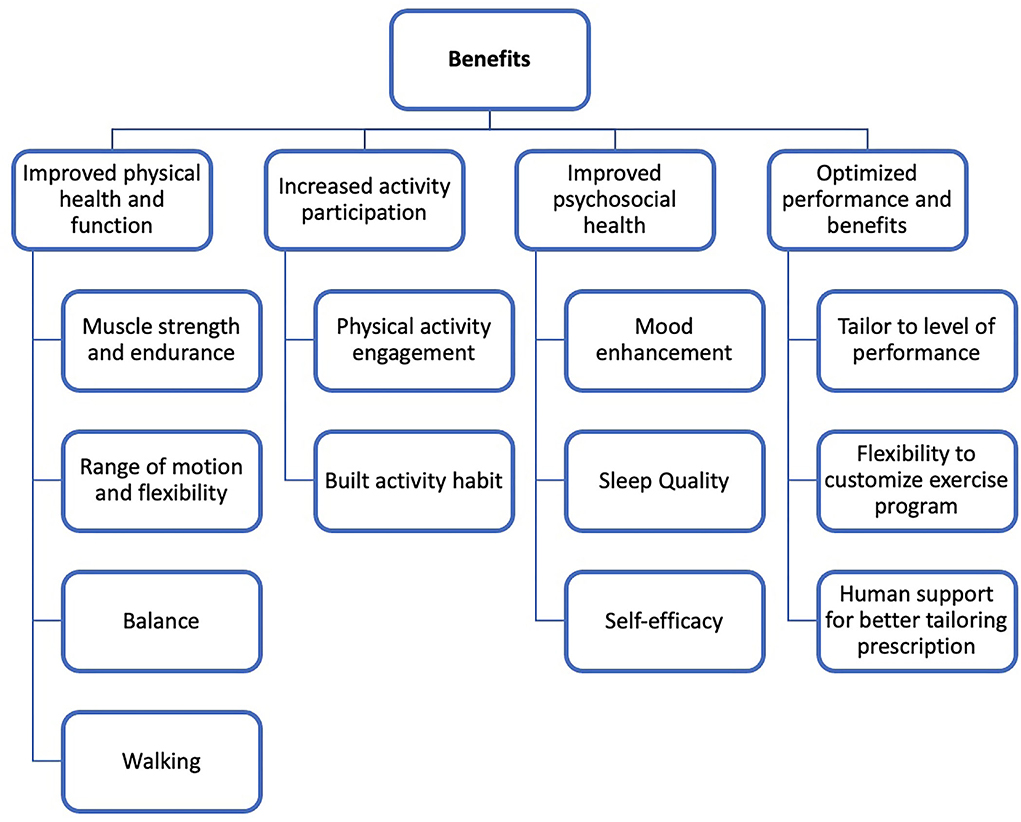

The mean age of the sample was 51 ± 13 years. The overall samples predominantly consisted of women (n = 21/30, 70%) and Caucasians (n = 21/30, 70%). Disabilities included eight with multiple sclerosis (26.7%), three Parkinson's Disease (10%), three spinal cord injury (10%), three spina bifida (10%), three stroke (10%), and six with spinal disorders (20%), such as scoliosis. Lastly, participants were selected based on a functional level for exercise routines, including 16 who were able to exercise standing, 12 sitting, and two with only one side of their body (i.e., hemiparesis). All the contacted participants agreed to complete the interview. Table 1 displays all themes, sub themes, and illustrative quotes and Figure 1 depicts the organization of themes and sub themes.

Themes

Theme 1: Improved physical health and function

The first theme highlighted perceived benefits on physical health and function those participants have experienced after the intervention period. Specific benefits included improvements in muscle strength and endurance, flexibility, balance, and walking. Participants reported that they felt more strength in their legs, core, and arms, as well as released muscle/joint stiffness, which further helped them decrease pain and ease the performance of daily activities (e.g., increasing energy level, walking long periods or with less use of cane). The program was also perceived to help reduce weight and increase balance and coordination, such as turning the head around safely while walking or driving.

Theme 2: Increased activity participation

Participants stated that they increased the volume of physical activity they performed after joining the program. Contributors to this increase in activity were participation in the exercise prescription and additional activities that they performed outside of the program (e.g., walking the neighborhood, counting steps, and lifting weights while watching TV). Participants stated that SUPER-HEALTH provided the needed knowledge of how to perform physical activity as a person with a disability and a reminder and encouragement to be physically active. Several participants noted how SUPER-HEALTH helped them to adopt a more active lifestyle.

Theme 3: Improved psychosocial health

The third theme highlighted that the program helped their psychosocial aspects of health. The benefits included mood enhancement, better sleep quality, and increases in self-efficacy. Participants often reported that they felt happier, energized, and mentally sharp after the exercise, which helped them continue the exercise and more activities throughout the day. They also noted enhanced confidence in their physical ability when accomplishing the prescribed exercise sessions and realizing their physical strength and ability with new movements.

Theme 4: Optimized performance and benefits

To optimize their performance and benefits, participants reported that the program could be better tailored to their abilities and interests. While many participants commented that the exercises were appropriate for their ability throughout the intervention period, some participants perceived that the program content was not appropriate for their functional ability/level (too challenging or too easy). Participants described challenges in some exercise routines that the movements were too fast and hard to follow, which created feelings of frustration. In contrast, some participants reported that too easy/slow exercises were not perceived as “exercise” and created feelings of boredom and decreased motivation to participate.

Some participants stated a desire for the ability to design an individualized program. Some included having the sequence of videos rearranged to increase the motivation and interest (e.g., the newest video on the top). They also suggested emphasizing exercise components meeting their specific needs and health concerns (e.g., focus on flexibility for pain due to tight muscles and focus on cardio for someone who has heart issues).

Some participants desired occasional human connection/support from research staff (instructors, coaches) via calls or Zoom meetings. They described that potential follow-up during the intervention can answer frequent questions for exercise programs (e.g., variation/adaptation of exercise difficulty, clarification of exercise movements, and the suggestion of appropriate weight), which could enhance the benefits received from the exercise sessions.

Discussion

This paper presented participants' perspectives for a randomized controlled trial aimed to investigate the effectiveness of a convenient telehealth exercise program for adults with neurological and physical disabilities. Currently, there are minimal exercise guidelines for PWD, and much more research is needed to develop effective interventions for increasing the benefits of exercise in this population (20, 21). Preliminary findings from this qualitative study indicate the potential benefit of a telehealth physical activity program for PWD. These perceived benefits included improvements in health and function, such as muscle strength and endurance, which translated into increased activity participation. For PWD, reducing secondary health conditions, such as pain and fatigue, is a priority for improving overall health, and several participants stated this as a benefit they received from the program. These benefits are similar to those found in onsite M2M-based programs (22, 23).

Suggestions for future telehealth exercise programs involved the precise tailoring of program support and program content. For program content, this can be completed in a couple of ways, such as delivering exercise routines through live, synchronous sessions, where participants schedule a time with the exercise instructor each week to complete sessions using video-conferencing and real-time monitoring technology. Another option is to allow users to create a ‘user design workout routine', where participants can choose exercise videos and build their routines. This would allow participants to create a program that emphasizes their personal health needs, such as more flexibility, strength, or cardiovascular health. This would also allow participants to target specific health issues they encounter based on disability etiology (e.g., neurological and musculoskeletal) using exercise guidelines targeting a specific disabling condition, if available (24, 25). Program support could be enhanced with the synchronous training, which allows the exercise instructor to provide both instrumental support through instructing movements and modifications to exercise routine and emotional support through verbal encouragement. Another suggestion for tailoring program support is to provide features that allow participants to share exercise schedules with other participants to enable a separate but synchronous exercise. Utilizing current technology for enhancing social connectedness can provide a seamless strategy for participants to organize their synchronous sessions with others.

SUPER-HEALTH was a large study of its kind, which used telehealth technology to encourage sustainable home exercise among underserved and disabled adult populations. The preliminary results of the trial show the effectiveness of this home exercise program, emphasizing the growing need for these convenient physical activity interventions. The exercise program, M2M, does this by making the exercise fun (with music and routines), and subjective to each participant's functional level by tailoring certain exercises and exercise intensities to them. The M2M program is provided in the form of music, which bolsters enjoyment and, therefore, participation, increases future scalability because it is seen as “fun” and can still be modified to be novel (through new music and movement patterns, while keeping the general premise the same). The constant monitoring technology used in this trial allows researchers to gauge when participants are not fully engaged in their exercise programs and prompts for more tailored coaching and adjustments. Importantly, participants stated no issues with utilizing the mobile health application or video delivery. Although this is a small sample of participants from the study, this should provide clinical providers an assurance that the usability of current technology for delivering exercise programs has minimal barriers for patients.

The purpose of the study was to collect qualitative data on participants' perceived benefits of the SUPER-HEALTH program. The study had several limitations. This study was conducted in one region of the United States and the findings may not be generalizable to other regions across the country or in other countries. This was a retrospective evaluation and some of the participants were interviewed at 24 weeks, while others were interviewed further out including up to 6 months from the 24-week endpoint. A purposeful sampling strategy was used to obtain diversity in interviews, which could introduce bias. Lastly, the sample was composed primarily of women (70%) and the findings may not be as representative of males.

Conclusion

SUPER-HEALTH connected participants to health professionals in the convenience of their home providing accessible exercise routines. Transportation and program costs are two of the most common barriers reported among those with physical disabilities and this program eradicates that issue. Telehealth in this specific study also confluences with current technologies in activity monitoring (FitBit), which allows the participant to receive a more accurate activity monitoring. Future programs should include tailoring of support and program content, such as exercises, coaching support, and program progression.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by UAB Office of Institutional Review Board. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JW, NI, and IH developed interview guides. JW was responsible for conducting the interviews. JW and YK analyzed the data. JW, YK, TS, and BL created the initial draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the final manuscript draft.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by the National Institutes of Health, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (5R01HD085186) and a Mentored Career Development Award from the National Center Advancing Translational Research (KL2 TR 003097).

Acknowledgments

We would like to give special thanks to the SUPER-HEALTH participants who participated in the follow interview to provide feedback on the program.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Rimmer J H, Chen M-D, Hsieh K. A conceptual model for identifying, preventing and treating secondary conditions in people with disabilities. Phy Ther. (2011) 91:1728–38. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20100410

2. Rimmer JH, Schiller W, Chen MD. Effects of disability-associated low energy expenditure deconditioning syndrome. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. (2012) 40:22–9. doi: 10.1097/JES.0b013e31823b8b82

3. Rimmer JH, Wang E. Obesity prevalence among a group of Chicago residents with disabilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2005) 86:1461–4. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.10.038

4. Post MWM, van Leeuwen CMC. Psychosocial issues in spinal cord injury: a review. Spinal Cord. (2012) 50:382–9. doi: 10.1038/sc.2011.182

5. Yekutiel M, Brooks ME, Ohry A, Yarom J, Carel R. The prevalence of hypertension, ischaemic heart disease and diabetes in traumatic spinal cord injured patients and amputees. Paraplegia. (1989) 27:58–62. doi: 10.1038/sc.1989.9

6. Saunders LL, Clarke A, Tate DG, Forchheimer M, Krause JS. Lifetime prevalence of chronic health conditions among persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2015) 96:673–9. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.11.019

7. Rimmer JH, Wang E, Yamaki K, Davis B. Documenting disparities in obesity and disability. In: Kreutzer J, DeLuca J, Caplan B, editors. Focus: A Publication of the National Center for the Dissemination of Disability Research (NCDDR). (2010) 24:1–6.

8. Froehlich-Grobe K, Jones D, Businelle MS, Kendzor DE, Balasubramanian BA. Impact of disability and chronic conditions on health. Disabil Health J. (2016) 9:600–8. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2016.04.007

9. Froehlich-Grobe K, Lee J, Washburn RA. Disparities in obesity and related conditions among Americans with disabilities. Am J Prev Med. (2013) 45:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.02.021

10. James SL, Theadom A, Ellenbogen RG, Bannick MS, Montjoy-Venning W, Lucchesi LR, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of traumatic brain injury and spinal cord injury, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. (2019) 18:56–87. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422[18]30415-0

11. Rimmer JH. Getting beyond the plateau: bridging the gap between rehabilitation and community-based exercise. Phy Med Rehabil. (2012) 4:857–61. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2012.08.008

12. Lai B, Cederberg K, Vanderbom KA, Bickel CS, Rimmer JH, Motl RW. Characteristics of Adults With Neurologic Disability Recruited for Exercise Trials: a secondary analysis. Adapt Phys Activ Q. (2018) 35:476–97. doi: 10.1123/apaq.2017-0109

13. Martin Ginis KA, Ma JK, Latimer-Cheung AE, Rimmer JH. A systematic review of review articles addressing factors related to physical activity participation among children and adults with physical disabilities. Health Psychol Rev. (2016) 10:478–94. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2016.1198240

14. Lai B, Young H-J, Bickel CS, Motl RW, Rimmer JH. Current trends in exercise intervention research, technology, and behavioral change strategies for people with disabilities: a scoping review. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. (2017). doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000000743

15. Jennett PA, Hall LA, Hailey D, Ohinmaa A, Anderson C, Thomas R, et al. The socio-economic impact of telehealth: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. (2003) 9:311–20. doi: 10.1258/135763303771005207

16. Rimmer JH, Mehta T, Wilroy J, Lai B, Young HJ, Kim Y, et al. Rationale and design of a scale-up project evaluating responsiveness to home exercise and lifestyle Tele-Health (SUPER-HEALTH) in people with physical/mobility disabilities: a type 1 hybrid design effectiveness trial. BMJ Open. (2019) 9. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023538.

17. Clarke V, Braun V, Hayfield N. Thematic analysis. In: Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods. London: Sage Publication (2015) 222:248.

18. Shenton AK. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Int J Educ. (2004) 22:63–75. doi: 10.3233/EFI-2004-22201

19. Sparkes AC, Smith B. Qualitative Research Methods in Sport, Exercise and Health: From Process to Product. London: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. (2013).

20. Martin Ginis KA, Sharma R, Brears SL. Physical activity and chronic disease prevention: where is the research on people living with disabilities? CMAJ. (2022) 194:E338–e40. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.211699

21. Martin Ginis KA, van der Ploeg HP, Foster C, Lai B, McBride CB, Ng K, et al. Participation of people living with disabilities in physical activity: a global perspective. Lancet. (2021) 398:443–55. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01164-8

22. Young H-J, Mehta T, Herman C, Baidwan NK, Lai B, Rimmer JH. The effects of a Movement-to-Music (M2M) intervention on physical and psychosocial outcomes in people poststroke: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Rehabil Res Clin Transl. (2021) 3:100160. doi: 10.1016/j.arrct.2021.100160

23. Young H-J, Mehta TS, Herman C, Wang F, Rimmer JH. The effects of M2M and adapted yoga on physical and psychosocial outcomes in people with multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2019) 100:391–400. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.06.032

24. Martin Ginis KA, van der Scheer JW, Latimer-Cheung AE, Barrow A, Bourne C, Carruthers P, et al. Evidence-based scientific exercise guidelines for adults with spinal cord injury: an update and a new guideline. Spinal Cord. (2018) 56:308–21. doi: 10.1038/s41393-017-0017-3

Keywords: disability, exercise, telehealth, mobile health (mhealth), qualitative

Citation: Wilroy JD, Kim Y, Lai B, Ivankova N, Herbey I, Sinha T and Rimmer JH (2022) How do people with physical/mobility disabilities benefit from a telehealth exercise program? A qualitative analysis. Front. Rehabilit. Sci. 3:932470. doi: 10.3389/fresc.2022.932470

Received: 29 April 2022; Accepted: 23 June 2022;

Published: 25 July 2022.

Edited by:

Javier Güeita-Rodriguez, Rey Juan Carlos University, SpainReviewed by:

Timothy Hasenoehrl, Medical University of Vienna, AustriaMark Manago, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, United States

Taslim Uddin, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University (BSMMU), Bangladesh

Copyright © 2022 Wilroy, Kim, Lai, Ivankova, Herbey, Sinha and Rimmer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jereme D. Wilroy, amR3aWxyb3lAdWFiLmVkdQ==

Jereme D. Wilroy

Jereme D. Wilroy Yumi Kim1,2

Yumi Kim1,2 Byron Lai

Byron Lai Nataliya Ivankova

Nataliya Ivankova James H. Rimmer

James H. Rimmer