- 1School of Rehabilitation Science, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada

- 2CanChild Centre for Childhood Disability Research, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada

- 3Sibling Youth Advisory Council, Hamilton, ON, Canada

- 4School of Nursing, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada

- 5Department of Health Research Methods, Evidence, and Impact, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada

- 6Offord Centre for Child Studies, Hamilton, ON, Canada

- 7Centre of Excellence for Rehabilitation Medicine, University Medical Center Utrecht and De Hoogstraat Rehabilitation, Utrecht, Netherlands

- 8Department of Pediatrics, McMaster University and McMaster Children's Hospital, Hamilton, ON, Canada

Background: As children and adolescents with a chronic health condition (CHC) age and transition to adulthood, many will increasingly assume responsibilities for the management of their healthcare. For individuals with CHCs, family members including siblings often provide significant and varied supports. There are a range of resources in Canada to support siblings of individuals with a CHC, but these resources are not synthesized and the extent to which they relate to healthcare management remains unclear.

Purpose: The purpose of this document review was to identify, describe, and synthesize the types of resources currently available to provide general information and healthcare management information about how siblings can provide support to individuals with CHCs in Canada.

Methods: Print and electronic resources were systematically identified and retrieved from the websites of organizations, treatment centers, and children's hospitals that are part of Children's Healthcare Canada. Each unique resource was treated as a text document. Documents that met the following inclusion criteria were included: addressed the topic of siblings of individuals with a CHC and written in English. Data were extracted from included documents and qualitative conventional content analysis was conducted. Throughout the process of this review, we partnered with a Sibling Youth Advisory Council.

Results: The systematic search yielded 1,628 non-duplicate documents, of which 163 documents met the inclusion criteria. Of the total of 163 documents, they were delivered in the following formats: 17 (10%) general informational products (e.g., booklets, videos) about a CHC and sibling relationships, 39 about support programs and workshops (24%), 34 news articles (21%) that described the roles of siblings, and 6 (3%) healthcare management informational products (e.g., toolkit, tipsheets), 31 blogs (19%) and 39 interviews (24%) with parents and siblings. In the blogs and interviews, siblings and parents described how siblings developed knowledge and skills for healthcare management, as well as their role and identity over time.

Significance: This study identified that there are limited resources available about healthcare management for siblings of CHC in Canada. Resources are needed to facilitate conversations in the family about the role of siblings with healthcare management of their sibling with a CHC.

Introduction

In North America, ~15 to 18% of all youths have a chronic health condition (CHC) (1, 2). The term “chronic health condition” encompasses congenital and acquired diseases, as well as physical and mental health conditions (3). There has been a shift toward providing care for a family of a child with a CHC using a non-diagnostic approach (4). Instead of focusing on a specific diagnosis or condition alone, increasing care, and supports focus on providing comprehensive care to address the holistic needs of the individual and family (4, 5).

Families often express significant concerns about how they can best support their child during the transition from the pediatric to adult healthcare systems (6). During this time, youth with CHCs will need to learn how to manage their healthcare, for example learning how to navigate the process of filling prescriptions, scheduling healthcare appointments, and answering questions from healthcare providers. Typically, support is provided by family members through this transition period. In addition to healthcare management, individuals with CHCs are also exploring their interests and goals, including school, work, and leisure (6–9) and learning to navigate new environments, including healthcare for adults, education, transportation, recreation, and social services (7). Throughout the lifespan, families typically can provide support, given their past experiences coordinating their family member's or child's care and knowledge of their child's strengths, areas of improvement, and goals (10).

In addition to parents, siblings are a part of the family who can provide support for their sibling with a CHC. Within the typical lifelong bonds between siblings, these relationships are highly dynamic and can change over time depending on the needs, roles, and commitments of the whole family (11–13). Each sibling relationship is different with varying levels of emotional closeness, social connectedness, and expectations of each other (14). During childhood and adolescence, sibling relationships are unique as they often live and grow up in their shared home environment where they can act as peers, confidants, or role models (15). At a young age, siblings of individuals with a CHC often recognize that they need to support their family in different contexts (16, 17). When there is future planning involved from the whole family, siblings often feel closer to each other and with their family, and they have a clearer understanding about their role for the future during adulthood (18, 19).

In some families, there may not be discussions about the role of siblings but siblings may be expected to become carers to their sibling with a CHC (20). In 2018, the Siblings Needs Assessment Survey was conducted in Canada among young adults who were ages 20 years or older, who had a sibling with a disability and received a total of 360 responses (21, 22). Siblings described concerns for their sibling's future such as finding employment or living independently (12, 23). Siblings might have worries for new responsibilities, such as guardianship or financial responsibilities, when their parents can no longer be the primary caregivers (13, 24, 25). These concerns can affect the extent to which siblings are involved in the healthcare of their sibling with a CHC.

Typically developing siblings might want to support their sibling with a disability, but they require knowledge and skills on how to do this. There are currently “Sibshops” that are offered across ten countries, including the United States and Canada (26). These Sibshops provide an opportunity for siblings to connect with people with similar experiences and share stories. A survey was conducted to evaluate Sibshops, in which 66% of respondents identified that they learned coping strategies, 75% reported that Sibshops had a positive impact on their adult lives, and 94% stated that they would recommend Sibshops to others (27). Often, one of the goals of Sibshops is to provide a space for siblings to meet and share experiences with other siblings of individuals with a CHC in a recreational setting (28). Some SibTeen sessions are also held for adolescents ages 13–17 years old to offer a community of support (29). Although there are support groups for siblings of individuals with a CHC, such as Sibshops and SibTeen sessions, there are no tailored resources or programs for typically developing siblings to share their concerns about supporting their sibling with a CHC specifically for healthcare management. There are many ways that siblings can provide support to their sibling with a CHC. These can be categorized as: concrete support such as taking on responsibilities and providing assistance; emotional support such as listening and empathizing; advice support such as offering information; and esteem support, such as expressing encouragement (30). Siblings can offer these different types of supports to help their sibling with a CHC manage their healthcare.

Informational needs have been identified to be a critical need for siblings (31). Siblings who wish to have a caregiving role often seek knowledge in how to provide care to their sibling with a CHC, how to navigate disability services, and how to seek supports for themselves (31). While there is information available and advertisements of services for siblings on websites of children's hospitals and organizations, many families and siblings identified that they were not aware of this information (32, 33). Siblings identified that they want to have an open, constructive dialogue with their parents about the future, including expectations and responsibilities (13, 24). Often, siblings had to learn how to care for their sibling on their own as information was not always passed down from parents to the siblings (11, 24).

Informational needs are also increasingly being addressed by individuals, including siblings and their families, through the use of the Internet. Siblings can share their experiences and needs online in various formats, such as blogs. Among the few studies that have analyzed the content of blogs, researchers identified how individuals who write these blogs can share experiences that might be different from what might be shared in a research study. Young adults and families have previously written blogs to document their experiences in healthcare, including their emotions and challenges (34–36). Similarly, blogs written by siblings and families can provide insights into the needs of siblings in order to prepare for their roles with healthcare management. There is a gap with little information known about the types of needs about healthcare management that siblings of individuals with CHC are sharing online.

Individuals may also choose to find information online for various reasons, including medical information, such as options for therapy, treatments and health services (37, 38). Siblings of individuals with a CHC require information on how they can provide support with healthcare management. In the Canadian Sibling Needs Assessment Survey, the majority of respondents across all age groups identified online websites as their preferred method for resources, information and tools (22). Programs, such as Sibshops and SibTeen sessions in North America, are often promoted online and share information about eligibility criteria and registration. In other countries, initiatives to support the needs of siblings of individuals with a CHC include Siblings Australia developed in 1999 (39), Sibs in the United Kingdom in 2001 (40), and the Sibling Leadership Network in the United States in 2007 (41). These initiatives in Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States have been established for many years, and includes an array of support programs and resources for siblings of individuals with a CHC. In Canada, the Sibling Collaborative was established in 2017 and offers online support groups with some resources such as information about the COVID-19 vaccine, finances, and stories from siblings (42). Despite the availability of many resources, as a team, we have heard from siblings that resources about healthcare are not easily accessible or retrievable in Canada. The resources are often posted on certain websites by children's hospitals and organizations, but the websites are not easy to navigate. In Canada, there is no national systems approach to store resources for siblings of individuals with a CHC. Considering the important and multi-faceted roles that siblings can have, it is important to identify and summarize the different types of resources that are available to siblings of individuals with a CHC.

This review aims to identify and describe:

i. the types of resources currently available in Canada to provide both general information and specific healthcare management information about how siblings can provide support to their sibling with a CHC; and

ii. key topics discussed in resources created by siblings and families.

Methods

Integrated Knowledge Translation

An integrated knowledge translation approach was used throughout the process of this review to partner with the Sibling Youth Advisory Council (SibYAC) comprised of six young adults who have a sibling with a disability. The SibYAC were first involved with the idea and concept, as well as the research question of this review. The SibYAC shared their experiences with searching for information to support their roles as siblings, and they identified a need to identify and synthesize resources that are available to siblings of individuals with a CHC. These experiences from the SibYAC provided a clear rationale to support our review aims. There were individual check-in meetings with each SibYAC member, and an engagement framework (43) and Involvement Matrix (44) were used as tools to ask about the tasks and roles that they would like to have in this review. The SibYAC were further involved in data analysis by sharing their perspectives for the retrieved documents to ensure that the extracted data are synthesized meaningfully for siblings, families, and other stakeholders. They were then involved with the interpretation of results and drawing conclusions. Meetings were held with the SibYAC to ask about their reflections of the summary of results with guiding questions including: How do the documents and websites support siblings in their role? Based on the documents and websites, what are some needs, information, or questions that you still have as a sibling? For example, in healthcare or in general. Reflections from the SibYAC helped to identify the gaps and future directions about resources to support siblings in their roles, including with healthcare management of their sibling with a CHC.

Qualitative Document Analysis

Qualitative document analysis involves a systematic search of documents and resources, which includes both printed and electronic resources (45). A variety of documents can be analyzed, including books, brochures, diaries, journals, event programs, or news articles.

Search Strategy

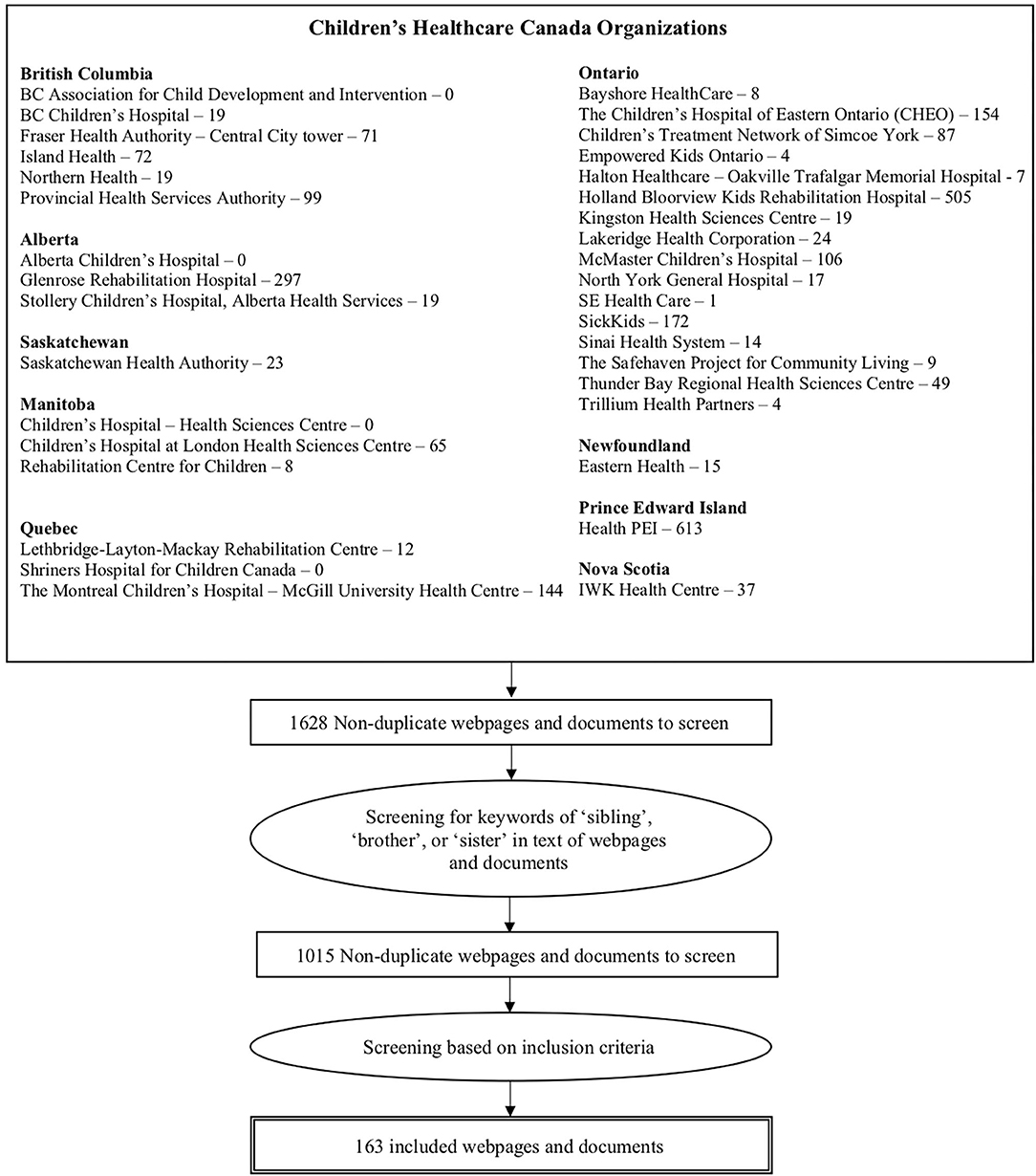

A comprehensive search was conducted on publicly available websites of thirty-one organizations, including children's hospitals, and rehabilitation centers that are part of Children's Healthcare Canada (46). These were selected to provide an initial understanding about the types of resources that are available for siblings of individuals with a CHC in a healthcare setting. The websites were searched in August 2020. A broad search strategy was employed in the search engine of each website with the terms: “sibling,” “brother,” or “sister.” All documents from the search were digitally retrieved using a feature called NVivo Capture and imported into NVivo (Version 11.4.3). Duplicates of documents across websites were removed.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Text from all retrieved documents was initially scanned in NVivo for the key terms of “sibling,” “brother,” or “sister.” Documents that included at least one of these key terms were read by the first author (LN). Identified documents were included in the review if they: (1) addressed the topic of relationships between siblings with and without a CHC; and (2) were published in English. Documents were excluded if the sibling was mentioned but did not discuss supports of siblings or the relationship between siblings of individuals with a CHC.

Ethical Considerations

Ethics approval was not required to retrieve and analyze documents that are publicly available on the Internet. An assessment of online documents can be conducted to identify the intent of online documents and its use in research, and documents that are written for public intent do not require consent from the creators or authors of the documents (47). In the analysis of retrieved documents, there was careful consideration to protect the privacy of the creators for the documents, and all personal identifiers were removed from included documents.

Data Extraction and Analysis

A data extraction template was created using Microsoft Excel Version 16.41 to collect data from each document (48). This template included the following categories: document source, document type, purpose/goals, and key content. For document types coded as “blog” or “interview,” content data for two additional categories were extracted: (1) family characteristics; and (2) CHC of an individual in the family. Additionally, all blogs and interviews were read and re-read in an iterative process to achieve immersion in the data and understand the stories shared by siblings and parents. Conventional content analysis was conducted by the first author (LN) for documents that were coded as blogs or interviews (49). Initial codes were developed based on the full text of the blogs and interviews, and these codes were then organized into categories to depict how they were related and linked to each other. Codes were grouped into meaningful clusters or categories based on their similarities in concepts. An Excel spreadsheet was created, that included extracted quotes and codes that were grouped into categories. Each category was expanded into a short statement to describe the key topic shared by siblings and families. Two analysis meetings were then held with individuals familiar with the content (e.g., SibYAC) and qualitative analysis (e.g., graduate students, co-author SJ) to review and name the categories, and identify additional properties and dimensions of each meaningful cluster. Analytic notes were written by the first author (LN) about how the categories related to each other to form meaningful clusters. While the content of all documents was analyzed to identify information and supports for healthcare management of an individual with a CHC, conventional content analysis allows for the identification of key topics from included documents that describe the experiences of siblings of individuals with a CHC beyond healthcare management. In this review, recognizing that gender is non-binary, we refer to siblings as a “brother” or “sister” based on the information provided in the resources included in this review with the recognition that siblings may identify themselves along a spectrum.

Data Credibility

To ensure credibility of the data, an audit trail and multiple analyst triangulation were used as two strategies. An audit trial was created to describe the steps and document decisions that were made about data extraction, as well as the identification of codes, categories, meaningful clusters, and key topics identified in the documents (50, 51). Sufficient time was also spent reviewing each source of information to identify recurrent patterns and key topics of the documents (52). The first author (LN) spent extensive time to read and re-read all documents, and took field notes of emerging ideas for each document in an Excel document (e.g., What is the main message about this document? How does this document relate to other documents?). To further enhance the credibility and dependability of the data, the lead author engaged in reflexivity and documented their own biases, preferences, and preconceptions about the topic in a series of memos (53, 54). Analyst triangulation was employed, in which multiple individuals with different backgrounds and expertise offered their perspectives about the preliminary and final findings (54). Two initial meetings were held to review and discuss how to organize preliminary findings: first with a group of graduate students with expertise in mixed methods and qualitative research, and then with the SibYAC. Two additional meetings were held with the SibYAC to share their reflections about the meaning of the findings in this review to them, describe whether the key topics from the blogs and interviews resonated with, or differed from, their experiences as young adult siblings of individuals with a disability, and identify gaps for future directions. All SibYAC members present at the meeting described that the key topics were similar to their experiences, and they provided suggestions for future directions in the development and enhancement of resources for siblings of individuals with a CHC. All authors of this review are from a multidisciplinary backgrounds including cognitive psychology, education, nursing, occupational therapy, physiatry, rehabilitation, patient-oriented research, and lived experiences, and all provided their perspectives on the synthesis of findings.

Results

The systematic search yielded 1,628 non-duplicate documents and resources, with 1,015 documents and resources that included keywords of “sibling,” “brother,” or “sister.” There were 163 documents and resources that met the inclusion criteria (See Figure 1).

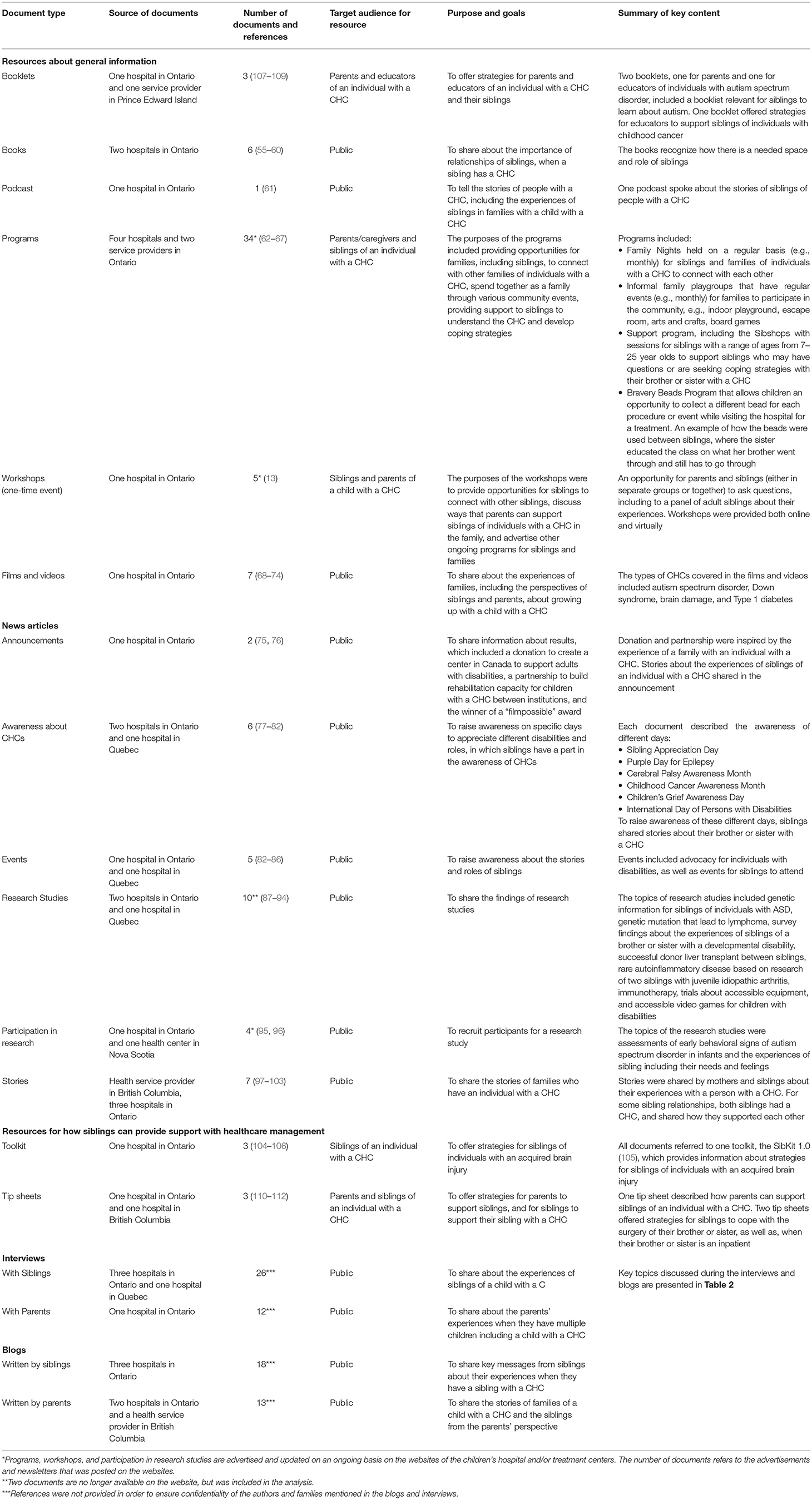

All resources were identified from treatment centers that provide inpatient and outpatient services to children and adolescents with a CHC. Some documents discussed CHCs as a broad group of conditions, while others referred to specific conditions such as autism spectrum disorder, cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, epilepsy, genetic disorders, juvenile arthritis, intellectual disorders, or mental health disorders. The documents included 6 books (55–60), 1 podcast (61), 34 programs and 5 workshops [references provided to websites where ongoing programs (62–67) and workshops (63) are advertised], 7 films and videos (68–74), and 34 news articles. Among the 34 news articles, they referred to 2 announcements (75, 76), 6 “awareness” recognition of different days or months of CHCs (77–82), 5 events (82–86), 10 research studies (87–94), 4 participation in research [references provided to websites where active research studies are posted (95, 96)] and 7 stories (97–103). Three documents referenced a toolkit (104–106), 3 booklets (107–109), and 3 tip sheets (110–112). Of the total of 163 documents, there were 31 blogs (19%), of which 13 (8%) written by parents and 18 (11%) written by siblings, and thirty-eight interviews (23%) with 12 (7%) interviews with parents and 26 (16%) interviews with siblings, and one interview with a family that included both the parents and siblings. Table 1 provides details about the document type, source of documents, number of documents and references, target audience, purpose and goals, and summary of key content.

Types of Resources for General Information

The majority of resources were general informational products for siblings of individuals with a CHC, which are available in a variety of formats. Supplementary Table 1 presents detailed descriptions of these resources.

i. Booklets and books. Books were available for siblings and families, in which some highlighted the need to understand the importance of sibling relationships, for example, creating a space for siblings to understand their emotions when they have a sibling with a CHC. Booklets were also available to provide guidance to parents and teachers about how to communicate with siblings of someone with a CHC.

ii. Podcasts. Personal stories from families, including siblings, were shared through podcasts, films, and videos. These stories described the journey of the whole family, and one podcast discussed the relationship between the siblings in which one sibling has a CHC.

iii. Programs and workshops. There are advertisements that announced past programs (n = 34) and workshops (n = 5) available to siblings and families. Among these 39 documents, 17 were in-person, 8 were virtual due to COVID-19, and 14 did not indicate the type of format. Most programs offered were sibling support groups, such as Sibshops, that are available throughout the year for siblings who are ages 7–25 years old. There were programs specifically for families to connect with other families of children with autism spectrum disorder available for free [reference to ongoing advertisement about the program (57)].

iv. News articles. All stories that were published as a news article were authored either by parents (n = 1), mothers (n = 2), or a sibling (n = 3), both a mother and sibling (n = 1). Articles authored by mothers focused on stories of their child's lived experience, parenting multiple children with a CHC or the same CHC, and/or the roles that other children may assume when there is a child with a CHC. Siblings discussed topics, such as sharing their emotions about their sibling relationship, providing support with healthcare management, and transitioning into different roles as a sibling, such as becoming a caregiver. Throughout the year, there were news articles with announcements about initiatives that were inspired by the stories of siblings. For example, there were announcements about various “awareness” days and months about specific disabilities and health conditions, which provided an opportunity for siblings to share stories about their sibling with a CHC (69–74). News articles also advertised research studies that were completed or actively recruiting sibling participants. The topics of these studies included genetic studies for specific health conditions, such as autism spectrum disorder and lymphoma, successful organ transplants between siblings, effectiveness of assistive equipment, and a survey to understand the needs and feelings of siblings of youth with a CHC.

Type of Resources for How Siblings Can Provide Support With Healthcare Management

There are few resources that provided information for siblings about their roles with respect to the healthcare management of their sibling with a CHC. When resources were available, they were formatted as either tip sheets or as a toolkit.

Toolkit and Tip Sheets

Both parents and siblings could refer to different sheets that were available for download online, which included tip sheets (110–112), and a toolkit (104). These sheets also focused on strategies for how siblings can provide support to their sibling with a CHC. For example, there was a tip sheet that described strategies for siblings of inpatients at a children's hospital (112). Some strategies for how siblings can be included as part of the inpatient stay were being a part of their sibling's care team, doing fun activities together, talking to their sibling, and helping the sibling to decorate their room (112). While the resources primarily focused on providing knowledge about a CHC to siblings, some resources provided additional strategies for siblings to support the healthcare management of their sibling with a CHC. A toolkit was also co-designed with siblings, clients, parents and clinical staff for brothers and sisters of children who have an acquired brain injury (104). The toolkit was described as a resource that siblings can use to learn knowledge about their sibling with an acquired brain injury and learn how to explain this injury to other adults who can provide help, when needed (104).

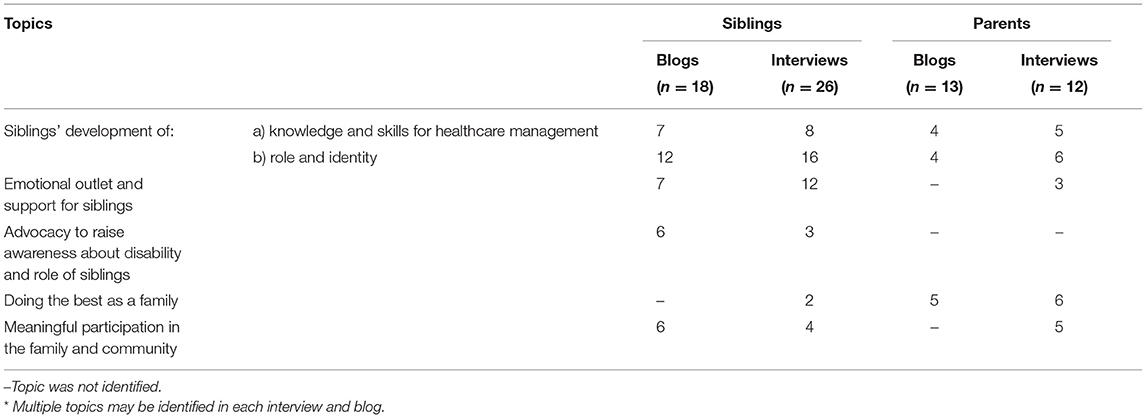

Blogs and Interviews

Siblings and families described different types of CHCs in blogs and interviews. Some siblings also had the same CHC as other siblings in the family. The age of siblings and individual with a CHC discussed in blogs and interviews ranged from infancy to older adults. The size of families ranged from one to five children. Based on an analysis of the content from blogs and interviews shared by siblings and parents, a conceptual map was developed to describe the codes, categories, and key topics discussed in these documents (See Figure 2). Detailed descriptions about these key topics are described in detail below. The frequency that these topics were identified in the blogs and interviews are provided in Table 2.

Siblings' Development of Knowledge and Skills for Healthcare Management

Siblings described how they needed to learn about the meaning of disability. Some siblings did not understand specific CHCs, such as the different treatments and services their siblings had to receive to manage their CHC. Siblings often described that they simply saw their sibling for who they were, regardless of the CHC. Parents shared stories in their blogs about the forming of relationships between their children. Young children learned how to develop their relationship with their sibling with a CHC. A mother shared the story of how she saw her two children interact with each other, where her young daughter asked to hug her brother or hold his hand when he was using an assistive device to walk. As siblings began to develop an understanding about the CHC, some siblings offered support with healthcare management. For example, a mother described how her daughter learned to be present and hold her brother's hand when he was using a suction machine. Siblings shared in interviews about how they learned different ways to support their siblings. For example, a sister observed her mother apply breathing techniques with her brother and she learned how to do the same. There was a process in which siblings first needed to learn about the CHC and develop a relationship with their sibling with a CHC, which then allowed them to learn how to offer support with healthcare management.

Siblings' Development of Role and Identity

The role of being a sibling to someone with a CHC provided them with experiences about a CHC, and the sibling role became a part of their identity. Young adult siblings shared in written blogs about how they were developing their own identity, such as moving away for university and developing their career. For some siblings, the experience of growing up in a family of an individual with a CHC motivated them to pursue a career to support other children with a CHC, such as healthcare professions and research about a CHC. Siblings would bring their personal experiences about a CHC into their professions, such as an understanding about a CHC in research or how to interact with families. Their personal experiences about a CHC also motivated them to use their academic knowledge to create resources, such as mobile applications or tools that children with a CHC could use. Both parents and siblings identified multiple roles that siblings had in the family. Siblings continued to maintain a close relationship, and when one sibling had an acquired CHC, the siblings would learn how to provide support to each other. For example, a sibling described how he went to therapy appointments with his brother who had an acquired brain injury. The sibling provided both support and humor by being present at the therapy appointments, and the parents described how the sibling became a part of the care team. Adult siblings described challenges that they had when they became a caregiver, such as the sacrifices that they had to make with living with their sibling with a CHC or not being able to work full-time.

Emotional Outlet and Support for Siblings

Siblings wrote in blogs that they shared with the community about both the positive aspects of their relationship with their sibling with a CHC as well as the challenges. Siblings shared the message about how they are not alone, where their thoughts and feelings matter. Some siblings pursued their own goals and happiness, and also chose their roles with their sibling with a CHC. Some adult siblings experienced guilt when they did not voice their opinions. One adult sibling shared her sense of guilt when her brother was sent to an institution that the family believed was a good option at the time. Siblings spoke about how their emotions were connected to the emotions that their parents were experiencing, such as frustrations and stresses. Some siblings wanted to find ways to address the challenges such as learning how to help their sibling with a CHC. With the different emotions that siblings were feeling, they sought ways to have an outlet to express their emotions. A Photovoice program was offered to siblings and young patients with cancer, where they took photographs that represented their experiences that were later displayed at an event for the public community. Siblings were developing skills in how to cope with their emotions, and parents identified how these siblings would develop personal skills such as being caring and empathetic. Siblings also shared about the importance of open communication with parents because siblings might have hidden emotions. Siblings identified that they might not initiate discussions with parents about their feelings, and parents should create a space for these discussions.

Advocacy to Raise Awareness About Disability and Role of Siblings

Some siblings became advocates, in which they expressed a need to explain what disability was to their peers. For example, a sibling of a brother with autism described how she read a book to her class to explain autism and she often took the time to answer questions from her classmates. Siblings valued the connection that they had with other siblings who had similar experiences. Some siblings grew up without knowing about other siblings who have a sibling with a CHC. Siblings wanted to connect to a community of siblings to not only advocate for CHC and disability awareness and supports, but also learn about the role that siblings can have. For example, some siblings did not realize that they developed skills that could be well-suited for healthcare professions. One sibling described how she learned about the profession of a child health specialist after connecting with another sibling. Furthermore, adult siblings who were caregivers or guardians of their sibling with a CHC they identified how their roles were often not recognized at work. For example, employers recognized when co-workers needed to leave to take care of their child but not for their sibling with a CHC. Siblings identified how there should be recognition of the important role that they have. They all wanted to be part of a community where they can create change and advocate for a diverse community that their own sibling with a CHC could meaningfully participate in.

Meaningful Participation in the Family and Community

Families identified the importance of creating an inclusive environment where a child with a CHC can participate in activities. Some families planned trips and made sure that they rented adaptive equipment to ensure that their child with a CHC could participate in activities, such as hiking, biking, or kayaking. In their daily lives, young siblings shared in their blogs that they made sure that their sibling with a CHC was included in the games that they played with their friends. One family thought about different ways that every member of the family could participate in activities. When a sibling might be attending speech therapy, other family members could coordinate to have the other siblings participate in a sports activity at the same time. Parents identified how it was important to make sure that all siblings could meaningfully participate in the community. Both parents and adult siblings expressed their concerns about opportunities for their sibling with a CHC to participate in the community in the future. Siblings shared the positive value of a job for their sibling with a CHC, which provided a sense of pride to participate in the community. Some siblings wanted to address concerns about how to create an inclusive community for people with CHCs, and they created mobile applications to encourage their sibling with a CHC to develop the skills needed to participate in the community. For example, one sibling created a mobile application with a set of cards with which an individual with autism could practice the skills they needed to carry out an activity, such as taking public transportation. Both parents and siblings sought opportunities for a sibling with a CHC to participate in the community as they grow older.

Doing the Best as a Family

During separate interviews, parents shared about how they were doing the best that they could as a family and siblings shared how the journey of every family was different. A mother shared in her blog about experiences with raising her children, including children with a learning disability and Down syndrome, and she needed to time to learn about her children. For other parents, they learned about the different types of supports that would be appropriate for their child with a CHC and there was no “one size fits all” approach. Some parents initially chose to keep their life private, and they did not want to burden others with the responsibilities in caring for their child with a CHC that they feel were their own. They gradually recognized how it was important to reach out to others for support, such as their children and neighbors. Some parents also sought respite services to take care of their own health in order to optimize the care that they could provide to all of their children. In addition to services, parents described the value of building a network of supports, such as connecting with other families with similar experiences. They wanted to have opportunities to meet other families and participate in activities that included the whole family. Some families created videos and films to share their story of both the positive experiences and challenges with other families.

SibYAC Reflections on the Findings

After synthesizing the findings from this review, the SibYAC members were asked to share their perspectives about the meaning of these findings. There were key topics raised in the blogs and interviews included in this review, and the SibYAC members were asked about whether these topics resonated with their own experiences of siblings of individuals with a disability. Siblings who wrote the blogs and inteviews included in this review identified that they wrote blogs as a way to share their stories so that other siblings would know that they are not alone, and writing blogs was an outlet for their emotions. Similarly, SibYAC members also wrote personal blogs about their personal experiences as a sibling and the roles that they have had. One SibYAC member shared an excerpt of her journal while her brother, who has cerebral palsy, was in a rehabilitation hospital after orthopedic surgery: “As my brother began to see progress into the next day, so did I. As he found a rhythm and learned the shuffles of the hallway, so did I. And before I knew it, I fell head over heels into the routine of physical and psychological exhaustion but unimaginable emotional fulfillment.” She shares that her personal experience is a clear example of why consciously integrating siblings into the family-centered care model is so important.

While the findings of this review help to identify key resources for general information and information of how siblings can provide support with healthcare management, the SibYAC continued to identify that there is a need for advocacy to raise awareness about the important roles that siblings have. They often had to learn to develop knowledge and skills, in order to have a role with supporting their sibling with a disability with healthcare management. A SibYAC member shared: “There is no handbook for special needs siblings. It's not something that's majorly talked about and kind of always felt like a big secret. Every day, I am learning more about how to appropriately support my sibling through the transition from pediatric into adult healthcare.” While this review identified that there are resources available for siblings of individuals with a CHC, few resources offer support for how siblings can be involved with the healthcare management of their sibling with a CHC.

As the SibYAC reflected on these findings, there is a critical gap in which there are no online resources available from Children's Healthcare Canada to support siblings in conversations about healthcare management and future planning to their sibling with a CHC, even though many siblings might already be part of the care team. A SibYAC member shared her personal experiences with this gap: “There has never been planning about the present, day-to-day things, let alone future planning, that has included me. The extent that I have been involved with my siblings is equal to the amount of intention and force I used to create a space for myself.” The SibYAC shared how discussions about future planning can be helpful for families to ensure that there is clear communication about the role of siblings.

Discussion

This review identified a variety of resources and documents available in English for siblings and families of children with CHCs across organizations of Children's Healthcare Canada. Most resources consisted of general information for siblings and families: to become aware and learn about different CHCs through books, news articles, and podcasts. There is an increasing trend in the use of the Internet for health information among patients, their families and general public (113), and each family requires different types of information based on their needs (114). In a qualitative study to explore the experiences of parents of children with disabilities who sought information, parents used online information to supplement the information provided by professionals (38). When healthcare professionals did not provide enough information during a consultation, some parents searched on websites of hospitals and rehabilitation centers for additional medical information (38). In the search for information, parents may also identify resources for how they can support the siblings of a child with a CHC. This review retrieved booklets for parents about how to communicate with siblings of children of individuals with a CHC.

In this review, few resources were identified to support siblings in the role of healthcare management with their sibling with a CHC. Similar to parents, siblings might also have questions and would like to have more information to support their roles in the healthcare management of their sibling with a CHC. Siblings of individuals with a CHC require skills and knowledge if they choose to have an active role in the healthcare management their sibling with a CHC. There are tip sheets that provided guidance for siblings to build a relationship with their sibling with a CHC, such as playing games or doing activities, as well as how to be a part of the care team (111, 112). There is also a toolkit that originally developed for siblings of individuals with an acquired brain injury, recently expanded to include different disabilities (105). It is important to consider and tailor different resources to prepare for the roles that siblings might choose to have, including with healthcare management of their sibling with a CHC.

This review highlighted a key gap in the needs of siblings based on the personal stories that they shared through blogs; many identified a need for emotional support. Blogs can be helpful for siblings, where they might find comfort to know that they are not alone (115). Siblings require acknowledgment of their emotions, and for some siblings, they are learning how to address their emotions as they continue to have a role in healthcare to their sibling with a CHC. Siblings might choose to seek online support to be part of a community with others who have similar experiences (115). Parents and families have previously described the importance of being a part of an online community where they can seek resources and connect with other families (38, 116), and siblings might have similar motivations to connect with other siblings online.

Siblings also shared, in blogs and interviews, their perspectives about the importance of advocacy to raise awareness about CHCs and their own roles. Siblings may need to advocate for their role in the family. This review identified that siblings require additional resources in order to learn and be prepared for their future roles. The extent of discussions about future planning can vary in families, and siblings are often not included in these discussions (13, 117). While some parents may wish for the siblings to have their own separate lives, siblings shared in qualitative studies that they chose to have active roles such as being a caregiver and they identified the need to have conversations with their parents about future planning (118, 119). Discussions about future planning can be helpful for families, providing an opportunity for siblings to identify new or changing roles and to facilitate the sharing of information between parents and siblings (31, 33). These discussions can be ongoing to adapt to the changing situations of the family over time. While these discussions can be challenging and complex for families, siblings identified the need to have clear plans so that they can be prepared for their future roles (117, 119, 120).

Many families shared how they are learning from experience and doing the best that they can with their family member with a CHC. In this review, both parents and siblings described the positive value of creating a supportive and inclusive environment of a person with a CHC. This inclusive environment applied to the family environment where some families sought opportunities to participate in different activities, as well as in the community such as having a job. Both parents and siblings described the concern that they had for an individual with a CHC after graduating from high school, and they were worried that there may be fewer opportunities to participate in the community. This concern about the transition to adulthood for individuals with a CHC has been raised in the literature (121, 122), and current news noting that there are ~12,000 young and middle-age adults with disabilities in Ontario, Canada who are on a waiting list to seek supports and residential care (123). In addition to employment opportunities, both parents and siblings have future worries for their child with a CHC such as the navigation from pediatric to adult healthcare services (122, 124). Some siblings shared in blogs and interviews how they gradually learned to take on caregiving responsibilities. Siblings are becoming adults and they may take on future caregiving responsibilities. They are often learning through experience about how to care for their sibling with a CHC throughout the lifespan (119).

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of this review is the involvement of the SibYAC as advisors throughout the process of this review. They provided their perspectives on the aims of the review, data analysis of resources, and future directions on how to disseminate the findings and develop future resources. Another strength of this review is that the resources identified have been compiled and can be applied to enhance existing resources for siblings of individuals with a CHC and inform the co-development of future resources. A limitation of this review is that the information that can be extracted from the documents included may be restricted by the purpose of the document and the content that the creators choose to share. Another limitation is that all documents were identified from children's hospitals and treatment centers that are part of Children's Healthcare Canada were in English and excluded documents in French. The documents and resources from the websites of organizations that are part of Children's Healthcare Canada might be selectively published and might not include information about the care that these organizations provide. The information may not be reflective of the entire landscape of resources for Canadian siblings of individuals with a CHC. In addition, at the time of this review, documents and resources were retrieved from 31 organizations that were a part of Children's Healthcare Canada. Since then, eight additional organizations have been included. Most organizations that are part of Children's Healthcare Canada are children's hospitals and rehabilitation centers, and resources from services offered in the community, such as mental health services, might have been missed. However, the resources and documents in this review provided a starting point for identifying general information and information about how siblings can support their sibling with healthcare management. Additionally, while data extraction and coding was conducted by a single analyst which limits our ability to report on inter-coder reliability, the categories and meaningful clusters of data that were developed were reviewed and discussed by two key stakeholder groups, a form of analyst triangulation and peer debriefing that enhances overall data credibility.

Future Directions

This review highlighted key gaps that can be addressed in the future in order to optimize supports for siblings of individuals with a CHC. First, access to existing resources for siblings should be improved by compiling and storing them in one place. As knowledge translation and dissemination can include multiple strategies, there can be multiple formats of resources created, such as infographics, toolkits, videos or podcasts. The Health Hub in Transition in Canada (125) and the F-words for Child Development Knowledge Hub (126) are examples of where information and tools are available online. The uptake and impact of the knowledge translation and dissemination strategies should be evaluated. Second, there should be resources to support siblings in the healthcare management of their sibling with a CHC. In this review, both parents and siblings shared in blogs and interviews the important role of siblings in healthcare management. Despite the important role that siblings might want to have with healthcare management, there are few resources available to support and empower siblings in this role. Third, this review identified that there are no resources in English available within the online materials from the organizations through Children's Healthcare Canada for parents or siblings to facilitate ongoing conversations about the roles that siblings would like to have with their sibling with a CHC. The conversations could also include the topic of healthcare transition about how youth, siblings, families, and healthcare professionals can help youth prepare for the transfer to adult healthcare (127). Tools could be developed to facilitate these discussions in the family and with healthcare professionals (32, 118). Finally, resources could be developed for other professionals, including teachers and healthcare providers, to encourage discussions about the experiences and roles of siblings beyond healthcare management. Siblings have identified that they wanted more information about future responsibilities, such as legal and financial information regarding the care of their sibling with a CHC (22, 24).

Conclusion

This review identified resources for siblings that are available from children's hospitals and organizations that are part of Children's Healthcare Canada. Resources that are available for siblings of individuals with a CHC mainly address general information, such as support programs and workshops. There are some resources, such as tip sheets and a toolkit, to offer strategies for siblings to learn about the healthcare management of their sibling with a CHC but these resources are only available at two children's hospitals. Siblings shared about their experiences in blogs and interviews, including their development of knowledge and skills for healthcare management, as well as roles and identity that often relate to the healthcare management of their sibling with a CHC. There is a key gap in available resources, in which siblings and parents identified that knowledge and skills for healthcare management is an important role for siblings but there are few resources that provide this information. Given the needs expressed by siblings, future resources should be developed to share information about healthcare management for siblings, as well as tools to facilitate family discussions about the roles that siblings would like to have in the future. A synthesis of the identified resources could be shared in an accessible format, such as in an online hub, for siblings and families.

Author Contributions

LN, BDR, SJ, MK, and JWG contributed to the conceptualization and design of this review, and perspectives from HD, SB, and JH informed the review aims. LN drafted the manuscript. HD, SB, and JH contributed to the draft of the Reflections section. All authors provided input for the analysis, interpreted the findings, revised and reviewed the manuscript, and provided their final approval.

Funding

This review was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Patient-Oriented Research Award—Transition to Leadership Stream—Phase 1 held by LN. The partnership with the Sibling Youth Advisory Council was financially supported by the Graduate Student Fellowship in Patient-Oriented Research through the CHILD-BRIGHT Network held by LN. During the work presented in this article, the Scotiabank Chair in Child Health Research was held by JWG.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge our partnership with the Sibling Youth Advisory Council throughout all phases of the review. We would like to thank Peter Rosenbaum for his constructive feedback and edits of the manuscript draft.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fresc.2021.724589/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Perrin JM, Bloom SR, Gortmaker SL. The increase of childhood chronic conditions in the United States. JAMA. (2007) 297:2755. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.24.2755

2. Newacheck PW, Strickland B, Shonkoff JP, Perrin JM, McPherson M, McManus M, et al. An epidemiologic profile of children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. (1998) 102:117–23. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.1.117

3. Knecht C, Hellmers C, Metzing S. The perspective of siblings of children with chronic illness: a literature review. J Pediatr Nurs. (2015) 30:102–16. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2014.10.010

4. Stein REK, Jessop DJ. A noncategorical approach to chronic childhood illness. Public Health Rep. (1982) 97:354–62.

5. King S, Teplicky R, King G, Rosenbaum P. Family-centered service for children with cerebral palsy and their families: a review of the literature. Semin Pediatr Neurol. (2004) 11:78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2004.01.009

6. Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: a theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. (2000) 55:469–80. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469

7. Stewart DA, Law MC, Rosenbaum P, Willms DG, Stewart DA, Law MC, et al. A qualitative study of the transition to adulthood for youth with physical disabilities. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. (2009) 21:3–21. doi: 10.1080/J006v21n04_02

8. Gorter JW, Stewart D, Woodbury-Smith M. Youth in transition: care, health and development. Child Care Health Dev. (2011) 37:757–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01336.x

9. Gorter JW, Stewart D, Smith MW, King G, Wright M, Nguyen T, et al. Pathways toward positive psychosocial outcomes and mental health for youth with disabilities: a knowledge synthesis of developmental trajectories. Can J Community Ment Health. (2014) 33:45–61. doi: 10.7870/cjcmh-2014-005

10. Rosenbaum P, King S, Law M, King G, Evans J. Family-centred service. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. (1998) 18:1–20. doi: 10.1300/J006v18n01_01

11. Atkin K, Tozer R. Personalisation, family relationships and autism: conceptualising the role of adult siblings. J Soc Work. (2014) 14:225–42. doi: 10.1177/1468017313476453

12. Moyson T, Roeyers H. The overall quality of my life as a sibling is all right, but of course, it could always be better”. Quality of life of siblings of children with intellectual disability: the siblings' perspectives. J Intellect Disabil Res. (2012). 56:87–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2011.01393.x

13. Heller T, Kramer J. Involvement of adult siblings of persons with developmental disabilities in future planning. Intellect Dev Disabil. (2009) 47:208–19. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-47.3.208

15. Whiteman SD, McHale SM, Soli A. Theoretical perspectives on sibling relationships. J Fam Theory Rev. (2011) 3:124–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-2589.2011.00087.x

16. Corsano P, Musetti A, Guidotti L, Capelli F. Typically developing adolescents' experience of growing up with a brother with an autism spectrum disorder. J Intellect Dev Disabil. (2017) 42:151–61. doi: 10.3109/13668250.2016.1226277

17. Latta A, Rampton T, Rosemann J, Peterson M, Mandleco B, Dyches T, et al. Snapshots reflecting the lives of siblings of children with autism spectrum disorders. Child Care Health Dev. (2014) 40:515–24. doi: 10.1111/cch.12100

18. McHale SM, Sloan J, Simeonsson RJ. Sibling relationships or children with autistic, mentally retarded, and nonhandicapped brothers and sisters. J Autism Dev Disord. (1986) 16:399–413. doi: 10.1007/BF01531707

19. McHale SM, Updegraff KA, Feinberg ME. Siblings of youth with autism spectrum disorders: theoretical perspectives on sibling relationships and individual adjustment. J Autism Dev Disord. (2016) 46:589–602. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2611-6

20. Davys D, Haigh C. Older parents of people who have a learning disability: perceptions of future accommodation needs. Br J Learn Disabil. (2008) 36:66–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3156.2007.00447.x

21. The Sibling Collaborative. Understanding the Sibling Experience: Sibling Needs Assessment Survey 2017 (2018). p. 1–19. Available online at: http://cdn.agilitycms.com/partners-for-planning/Understanding the Sibling Experience-March 2018-Final.pdf (accessed January 2, 2021).

22. Redquest BK, Tint A, Ries H, Goll E, Rossi B, Lunsky Y. Support needs of Canadian adult siblings of brothers and sisters with intellectual/developmental disabilities. J Policy Pract Intellect Disabil. (2020) 17:239–46. doi: 10.1111/jppi.12339

23. Mascha K, Boucher J. Preliminary investigation of a qualitative method of examining siblings' experiences of living with a child with ASD. Br J Dev Disabil. (2006) 52:19–28. doi: 10.1179/096979506799103659

24. Arnold CK, Heller T, Kramer J. Support needs of siblings of people with developmental disabilities. Intellect Dev Disabil. (2012) 50:373–82. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-50.5.373

25. Krauss MW, Seltzer MM, Gordon R, Friedman DH. Binding ties: the roles of adult siblings of persons with mental retardation. Ment Retard. (1996) 34:83–93.

26. Sibling Support Project. The Sibling Support Project (2020). Available online at: https://www.siblingsupport.org/ (accessed November 15, 2020).

27. Johnson AB. Sibshops: A Follow-Up of Participants of a Sibling Support Program. Seattle, WA: University of Washington (2005).

28. D'Arcy F, Flynn J, McCarthy Y, O'Connor C, Tierney E. Sibshops. An evaluation of an interagency model. J Intellect Disabil. (2005) 9:43–57. doi: 10.1177/1744629505049729

29. Opening Hearts. SibTeens (2019). Available online at: https://www.openinghearts.ca/sibteens/ (accessed June 2, 2021).

30. Cutrona CE. Social support principles for strengthening families: messages from the USA. In: Canavan J, Dolan P, Pinkerton J, editors. Family Support: Direction From Diversity. London: Jessica Kingsley (2000). p. 103–22.

31. Arnold CK, Heller T. Caregiving experiences and outcomes: wellness of adult siblings of people with intellectual disabilities. Curr Dev Disord Rep. (2018) 5:143–9. doi: 10.1007/s40474-018-0143-4

32. Dyke P, Mulroy S, Leonard H. Siblings of children with disabilities: challenges and opportunities. Acta Paediatr Int J Paediatr. (2009) 98:23–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.01168.x

33. Hall SA, Rossetti Z. The roles of adult siblings in the lives of people with severe intellectual and developmental disabilities. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. (2018) 31:423–34. doi: 10.1111/jar.12421

34. Keim-Malpass J, Baernholdt M, Erickson JM, Ropka ME, Schroen AT, Steeves RH. Blogging through cancer: young women's persistent problems shared online. Cancer Nurs. (2013) 36:163–72. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31824eb879

35. Marcus MA, Westra HA, Eastwood JD, Barnes KL, Group MMR. What are young adults saying about mental health? An analysis of internet blogs. J Med Internet Res. (2012) 14:e1868. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1868

36. Clarke JN, Lang L. Mothers whose children have ADD/ADHD discuss their children's medication use: an investigation of blogs. Soc Work Health Care. (2012) 51:402–16. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2012.660567

37. Rice RE. Influences, usage, and outcomes of internet health information searching: multivariate results from the pew surveys. Int J Med Inform. (2006) 75:8–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2005.07.032

38. Alsem MW, Ausems F, Verhoef M, Jongmans MJ, Meily-Visser JMA, Ketelaar M. Information seeking by parents of children with physical disabilities: an exploratory qualitative study. Res Dev Disabil. (2017) 60:125–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2016.11.015

39. Siblings, Australia,. Available online at: https://siblingsaustralia.org.au/ (accessed July 22, 2021).

40. Sibs. Available online at: https://www.sibs.org.uk/ (accessed July 22, 2021).

41. Sibling Leadership Network. Available online at: https://siblingleadership.org/ (accessed July 22, 2021).

42. The Sibling Collaborative. Available online at: https://sibcollab.ca/ (accessed July 22, 2021).

43. Ontario Brain Institute. Ways Community Members can Participate in the Stages of Research. Toronto, ON: Ontario Brain Institute (2019).

44. Smits D-W, van Meeteren K, Klem M, Alsem M, Ketelaar M. Designing a tool to support patient and public involvement in research projects: the involvement matrix. Res Involv Engagem. (2020) 6:30. doi: 10.1186/s40900-020-00188-4

45. Bowen GA. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qual Res J. (2009) 9:27–40. doi: 10.3316/QRJ0902027

46. Children's Healthcare Canada. Our Members and Patrons (2021). Available online at: https://www.childrenshealthcarecanada.ca/members-patrons (accessed April7, 2021)

47. Orr E, Jack S, Sword W, Ireland S, Ostolosky L. Understanding the blogging practices of women undergoing in vitro fertilization (IVF): a discourse analysis of women's IVF blogs. Qual Rep. (2017) 22:1364–82. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2017.2927

48. Altheide DL, Schneider CJ. Process of document analysis. In: Qualitative Media Analysis. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc (2013). p. 39–74. doi: 10.4135/9781452270043

49. Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. (2005) 15:1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

50. Bowen GA. Supporting a grounded theory with an audit trail: an illustration. Int J Soc Res Methodol. (2009) 12:305–16. doi: 10.1080/13645570802156196

51. Lincoln Y, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills: SAGE (1985). doi: 10.1016/0147-1767(85)90062-8

52. Krefting L. Rigor in qualitative research: the assessment of trustworthiness. Am J Occup Ther. (1991) 45:214–22. doi: 10.5014/ajot.45.3.214

53. Moser A, Korstjens I. Series: practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. Eur J Gen Pract. (2018) 24:9–18. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2017.1375091

54. Patton MQ. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Serv Res. (1999) 34 (5 Pt. 2):1189–208.

55. Kinross L. A Twin's Bond Sparks Brilliance (2015). Available online at: https://hollandbloorview.ca/stories-news-events/BLOOM-Blog/twins-bond-sparks-brilliance (accessed March 12, 2021).

56. Kinross L. New Journal Explores Sibling Emotions About Disability(2016). Available online at: https://www.hollandbloorview.ca/stories-news-events/BLOOM-Blog/new-journal-explores-sibling-emotions-about-disability (accessed March 12, 2021).

57. Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital. “Why Do You Love Jacob More Than Us?”. Holland Bloorview (2014). Available online at: https://hollandbloorview.ca/stories-news-events/BLOOM-Blog/why-do-you-love-jacob-more-us (accessed May 29, 2021).

58. Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital. Around the World, Brothers and Sisters Are No Longer an Afterthought in a Disabled Child's Care (2019). Available online at: https://hollandbloorview.ca/stories-news-events/BLOOM-Blog/around-world-brothers-and-sisters-are-no-longer-afterthought (accessed May 29, 2021).

59. Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital. Everything You Want to Know About Siblings (2014). Available online at: https://hollandbloorview.ca/stories-news-events/BLOOM-Blog/everything-you-want-know-about-siblings (accessed May 29, 2021).

60. Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario. Hospitalization and Surgery. Available online at: https://www.cheo.on.ca/en/resources-and-support/hospitalization-and-surgery.aspx#Journals (accessed March 14, 2021).

61. Kinross L. BBC Ouch: Brothers, Sisters and Disability (2016). Available online at: https://www.hollandbloorview.ca/stories-news-events/BLOOM-Blog/bbc-ouch-brothers-sisters-and-disability (accessed March 12, 2021).

62. Children's Treatment Network. Events. Available online at: https://www.ctnsy.ca/Events.aspx (accessed May 30, 2021).

63. Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital. Family Workshops and Resources. Available online at: https://hollandbloorview.ca/services/family-workshops-resources (accessed May 30, 2021).

64. Children's Hospital–London Health Sciences Centre. Hematology and Oncology (2021). Available online at: https://www.lhsc.on.ca/hematology-oncology (accessed May 30, 2021).

65. McMaster Children's Hospital. Autism Program (2021). Available online at: https://www.hamiltonhealthsciences.ca/mcmaster-childrens-hospital/areas-of-care/developmental-pediatrics-and-rehabilitation/autism-program/ (accessed May 30, 2021).

66. Bayshore HealthCare. Canada's Young Caregivers (2019). Available online at: https://www.bayshore.ca/2019/07/19/canadas-young-caregivers/#: :text=InToronto%2CTheYoungCarers,illness%2Corlanguagebarrier (accessed May 30, 2021).

67. SickKids. Women's Auxiliary Volunteers (WAV) (2021). Available online at: https://www.sickkids.ca/en/careers-volunteer/volunteering/womens-auxiliary-volunteers/#bravery (accessed May 30, 2021).

68. Kinross L. A Brother With Down Syndrome is the Focus of the Film “Music and Clowns” (2020). Available online at: https://research.hollandbloorview.ca/stories-news-events/BLOOM-Blog/brother-down-syndrome-focus-film-music-and-clowns (accessed May 29, 2021).

69. Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital. A Magical Bond (2020). Available online at: http://bloom-parentingkidswithdisabilities.blogspot.com/2014/03/a-magical-bond_12.html (accessed May 29, 2021).

70. Kinross L. These Parents Took a Year Off to Learn to “Speak Oskar” (2017). Available online at: https://hollandbloorview.ca/stories-news-events/BLOOM-Blog/these-parents-took-year-learn-speak-oskar (accessed March 12, 2021).

71. Kinross L. When a Child Has a Chronic Illness, Every Family Member Adapts (2018). Available online at: https://hollandbloorview.ca/stories-news-events/BLOOM-Blog/when-child-has-chronic-illness-every-family-member-adapts (accessed March 12, 2021).

72. Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital. “The People That Have the Voice Are Too Tired to Raise Their Voice” (2018). Available online at: https://hollandbloorview.ca/stories-news-events/BLOOM-Blog/people-have-voice-are-too-tired-raise-their-voice (accessed March 12, 2021).

73. BBC. My Autism and Me (2014). Available online at: https://hollandbloorview.ca/stories-news-events/BLOOM-Blog/my-autism-and-me (accessed May 29, 2021).

74. Kinross L. Single Mom Embraces “Life of Triage” With Autistic Boys (2016). Available online at: https://hollandbloorview.ca/stories-news-events/BLOOM-Blog/single-mom-embraces-life-triage-autistic-boys (accessed March 12, 2021).

75. Kinross L. New Hub to Address Developmental Disabilities, Mental Illness (2018). Available online at: https://hollandbloorview.ca/stories-news-events/BLOOM-Blog/new-hub-address-developmental-disabilities-mental-illness (accessed March 12, 2021).

76. Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital. Director Owen McIntyre's Film “My Life With My Brother Rhys” Wins the Filmpossible Award, Presented by Holland Bloorview in Partnership TIFF Kids International Film Festival (2016). Available online at: https://hollandbloorview.ca/stories-news-events/news/director-owen-mcintyres-film-my-life-my-brother-rhys-wins-filmpossible (accessed March 12, 2021).

77. Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital. Malakhai and Nathaniel. Available online at: https://foundation.hollandbloorview.ca/stories-news-events/stories/malakhai-and-nathaniel (accessed March 12, 2021).

78. Montreal Children's Hospital. Seizing the Moment: Sarah's Journey. Available online at: https://www.thechildren.com/patients-families/patient-testimonials/seizing-moment-sarahs-journey (accessed March 12, 2021).

79. CBC News. Hospital for Sick Children's Celebrates Patients' Siblings (2015). Available online at: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/hospital-for-sick-children-celebrates-patients-siblings-1.3103361 (accessed June 2, 2021).

80. SickKids. “Grieving in Chunks”: Helping Kids Cope With the Death of a Loved One. (2017). Available online at: https://www.sickkids.ca/en/news/archive/2017/grieving-in-chunks-helping-kids-copewith-the-death-of-a-loved-one (accessed September 7, 2021).

81. Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital. After the Fall (2014). Available online at: https://hollandbloorview.ca/stories-news-events/BLOOM-Blog/voice-andrew (accessed May 30, 2021).

82. SickKids. Photovoice: The Power of Photography Brings Teen Cancer Patients and Siblings Together (2019). Available online at: https://www.sickkids.ca/en/news/archive/2019/photovoice-the-power-of-photography-brings-teen-cancer-patients-and-siblings-together-/ (accessed March 12, 2021).

83. Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital. A Voice for ANDREW (2013). Available online at: https://hollandbloorview.ca/stories-news-events/BLOOM-Blog/voiceandrew (accessed May 30, 2021).

84. Montreal Children's Hospital. Former Volunteer Brings Siblings Together at the Just for Kids Sibling Park (2019). Available online at: https://www.thechildren.com/news-and-events/latest-news/former-volunteer-brings-siblings-together-just-kids-sibling-park (accessed May 30, 2021).

85. Kinross L. Young Carers and Other Pieces of Disability News (2017). Available online at: https://hollandbloorview.ca/stories-news-events/BLOOM-Blog/young-carers-and-other-pieces-disability-news (accessed March 12, 2021).

86. Montreal Children's Hospital. Sibling drop-off program launches in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) (2017). Available online at: https://www.thechildren.com/news-and-events/latest-news/sibling-drop-program-launches-neonatal-intensive-care-unit-nicu (accessed May 30, 2021).

87. SickKids. Genome Testing for Siblings of Individuals With Autism May Detect Diagnosis Before Symptoms Appear (2019). Available online at: https://www.sickkids.ca/en/news/archive/2019/genome-testing-for-siblings-of-individuals-with-autism-may-detect-diagnosis-before-symptoms-appear/ (accessed June 2, 2021).

88. Montreal Children's Hospital. Seeing Double: Siblings Diagnosed With Same Rare Disease (2018). Available online at: https://www.thechildren.com/news-and-events/latest-news/seeing-double-siblings-diagnosed-same-rare-disease (accessed March 12, 2021).

89. Kinross L. Siblings Say Depression in Disabled Adults is Their Top Worry (2018). Available online at: https://hollandbloorview.ca/stories-news-events/BLOOM-Blog/siblings-say-depression-disabled-adults-their-top-worry (accessed May 30, 2021).

90. SickKids. SickKids-Led Team Sheds More Light on New Autoinflammatory Disease (2018). Available online at: https://www.sickkids.ca/en/news/archive/2018/sickkids-led-team-sheds-more-light-on-new-autoinflammatory-disease-/ (accessed May 30, 2021).

91. Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital. Here's One Video Game Parents Will Welcome Into Their Home. Available online at: https://foundation.hollandbloorview.ca/stories-news-events/stories/heres-one-video-game-parents-will-welcome-their-home (accessed May 30, 2021).

92. Jones M. Maritza's Dream: Games That Make Therapy Fun (2015). Available online at: https://hollandbloorview.ca/stories-news-events/BLOOM-Blog/maritzas-dream-games-make-therapy-fun (accessed March 12, 2021).

93. Montreal Children's Hospital. Scientific Breakthrough: Promising New Target for Immunotherapy (2018). Available online at: https://muhc.ca/newsroom/news/scientific-breakthrough-promising-new-target-immunotherapy (accessed May 30, 2021).

94. Sharp MK. Taking Steps, Together, With “Upsee” (2014). Available online at: http://bloom-parentingkidswithdisabilities.blogspot.com/2014/04/taking-steps-together-with-upsee.html (accessed May 30, 2021).

95. IWK Health Centre. Active Research Areas. Available online at: https://www.iwk.nshealth.ca/research/active-research-areas (accessed May 30, 2021).

96. Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital. Participate in Research. Available online at: https://research.hollandbloorview.ca/get-involved-give/participate-in-research (accessed May 30, 2021).

97. Kinross L. How Difficult Could Caregiving be? This Sister Found Out. (2016). Available online at: http://bloom-parentingkidswithdisabilities.blogspot.com/2016/02/how-difficult-could-caregiving-be-this.html (accessed May 30, 2021).

98. Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital. Isn't a Person More Than a Brain? (2013). Available online at: http://bloom-parentingkidswithdisabilities.blogspot.com/2013/07/isnt-person-more-than-brain.html (accessed May 30, 2021).

99. Montreal Children's Hospital. One Breath at a Time. Available online at: https://www.thechildren.com/patients-families/patient-testimonials/one-breath-time (accessed May 30, 2021).

100. Hamilton Health Sciences. Opting for an Ostomy: A Young Woman's Journey With Crohn's (2017). Available online at: https://www.hamiltonhealthsciences.ca/share/abby-colling/ (accessed Mar 12, 2021).

101. Provincial Health Services Authority. Rosalind's Story. Available online at: http://www.phsa.ca/health-info/hearing-loss-early-language/stories-from-families/rosalinds-story (accessed May 30, 2021).

102. Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital. Special Needs Parents: Here's How to Make Sure Your Other Kids Are Supported (2020). Available online at: https://hollandbloorview.ca/stories-news-events/news/special-needs-parents-heres-how-make-sure-your-other-kids-are-supported (accessed May 30, 2021).

103. Reid K. The Inherited Metabolic Disorders News (2011). Available online at: https://www.lhsc.on.ca/media/2486/download (accessed June 2, 2021).

104. Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital. SibKit. Available online at: https://hollandbloorview.ca/sites/default/files/2020-06/ABI-SibKit-May2020-Accessible.pdf (accessed June 2, 2021).

105. Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital. SibKits. Available online at: https://hollandbloorview.ca/services/family-workshops-resources/family-resource-centre/online-family-resources-centre/sibkits (accessed May 29, 2021).

106. Kinross L. A Child's Brain Injury Has Ripple Effects on Siblings. SibKit is a Safe Space to Explore Them (2019). Available online at: https://hollandbloorview.ca/stories-news-events/BLOOM-Blog/childs-brain-injury-has-ripple-effects-siblings-sibkit-safe-space (accessed May 29, 2021).

107. Timmons V, Breitenbach M, MacIsaac M. A Resource Guide for Parents of Children with Autism: Supporting Inclusive Practice (2016). Available online at: https://www.princeedwardisland.ca/sites/default/files/publications/eelc_autism_guide_for_parents.pdf (accessed June 2, 2021).

108. Timmons V, Breitenbach M, MacIsaac M. Educating Children about Autism in an Inclusive Classroom (2016). Available online at: https://www.princeedwardisland.ca/en/publication/educating-children-about-autism-inclusive-classroom (accessed June 2, 2021).

109. Children's Hospital–London Health Sciences Centre. Helping Schools Cope With Childhood Cancer (2011). Available online at: https://www.lhsc.on.ca/media/1491/download (accessed June 2, 2021).

110. Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital. Parent Tipsheet: Supporting Siblings (2018). Available online at: https://hollandbloorview.ca/services/family-workshops-resources/family-resource-centre/online-family-resources-centre/parent-0 (accessed May 29, 2021).

111. BC Children's Hospital. Tips to Help Your Child Cope With a Brother's or Sister's Surgery. Available online at: http://www.bcchildrens.ca/Child-Life-site/Documents/Surgerytipsheet-SIBLINGS.docx (accessed May 29, 2021).

112. Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital. Tips for Inpatient Siblings. Available online at: https://hollandbloorview.ca/services/family-workshops-resources/family-resource-centre/online-family-resources-centre/tips (accessed May 29, 2021).

113. Zhao Y, Zhang J. Consumer health information seeking in social media: a literature review. Health Info Libr J. (2017) 34:268–83. doi: 10.1111/hir.12192

114. Freeman M, Stewart D, Cunningham CE, Gorter JW. Information needs of young people with cerebral palsy and their families during the transition to adulthood: a scoping review. J Transit Med. (2018) 1:1–16. doi: 10.1515/jtm-2018-0003

115. Dansby RA, Turns B, Whiting JB, Crane J. A phenomenological content analysis of online support seeking by siblings of people with autism. J Fam Psychother. (2018) 29:181–200. doi: 10.1080/08975353.2017.1395256

116. Russell DJ, Sprung J, McCauley D, Kraus de Camargo O, Buchanan F, Gulko R, et al. Knowledge exchange and discovery in the age of social media: the journey from inception to establishment of a parent-led web-based research advisory community for childhood disability. J Med Internet Res. (2016) 18:e293. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5994

117. Davys D, Mitchell D, Haigh C. Futures planning, parental expectations and sibling concern for people who have a learning disability. J Intellect Disabil. (2010) 14:167–83. doi: 10.1177/1744629510385625

118. Tozer R, Atkin K. Recognized, valued and supported”? The experiences of adult siblings of people with autism plus learning disability. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. (2015) 28:341–51. doi: 10.1111/jar.12145